Project Gutenberg's The Courage of Captain Plum, by James Oliver Curwood This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net Title: The Courage of Captain Plum Author: James Oliver Curwood Release Date: May 20, 2004 [EBook #12388] Language: English Character set encoding: US-ASCII *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE COURAGE OF CAPTAIN PLUM *** Produced by Suzanne Shell, Kara Passmore, Leah Moser and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team.

Contents

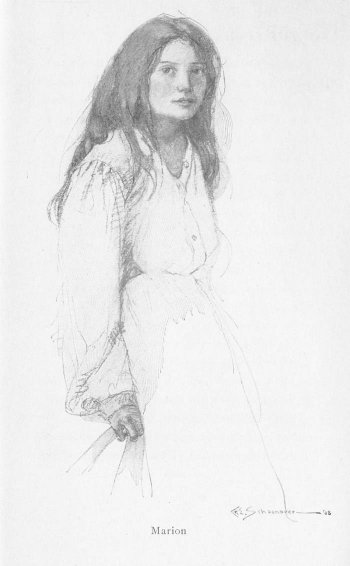

List of Illustrations

"I Am Going to Take You from the Island!"

His Fingers Twined About the Purplish Throat.

On an afternoon in the early summer of 1856 Captain Nathaniel Plum, master and owner of the sloop Typhoon was engaged in nothing more important than the smoking of an enormous pipe. Clouds of strongly odored smoke, tinted with the lights of the setting sun, had risen above his head in unremitting volumes for the last half hour. There was infinite contentment in his face, notwithstanding the fact that he had been meditating on a subject that was not altogether pleasant. But Captain Plum was, in a way, a philosopher, though one would not have guessed this fact from his appearance. He was, in the first place, a young man, not more than eight or nine and twenty, and his strong, rather thin face, tanned by exposure to the sea, was just now lighted up by eyes that shone with an unbounded good humor which any instant might take the form of laughter.

At the present time Captain Plum's vision was confined to one direction, which carried his gaze out over Lake Michigan. Earlier in the day he had been able to discern the hazy outline of the Michigan wilderness twenty miles to the eastward. Straight ahead, shooting up rugged and sharp in the red light of the day's end, were two islands. Between these, three miles away, the sloop Typhoon was strongly silhouetted in the fading glow. Beyond the islands and the sloop there were no other objects for Captain Plum's eyes to rest upon. So far as he could see there was no other sail. At his back he was shut in by a dense growth of trees and creeping vines, and unless a small boat edged close in around the end of Beaver Island his place of concealment must remain undiscovered. At least this seemed an assured fact to Captain Plum.

In the security of his position he began to whistle softly as he beat the bowl of his pipe on his boot-heel to empty it of ashes. Then he drew a long-barreled revolver from under a coat that he had thrown aside and examined it carefully to see that the powder and ball were in solid and that none of the caps was missing. From the same place he brought forth a belt, buckled it round his waist, shoved the revolver into its holster, and dragging the coat to him, fished out a letter from an inside pocket. It was a dirty, much worn letter. Perhaps he had read it a score of times. He read it again now, and then, refilling his pipe, settled back against the rock that formed a rest for his shoulders and turned his eyes in the direction of the sloop.

The last rim of the sun had fallen below the Michigan wilderness and in the rapidly increasing gloom the sloop was becoming indistinguishable. Captain Plum looked at his watch. He must still wait a little longer before setting out upon the adventure that had brought him to this isolated spot. He rested his head against the rock, and thought. He had been thinking for hours. Back in the thicket he heard the prowling of some small animal. There came the sleepy chirp of a bird and the rustling of tired wings settling for the night. A strange stillness hovered about him, and with it there came over him a loneliness that was chilling, a loneliness that made him homesick. It was a new and unpleasant sensation to Captain Plum. He could not remember just when he had experienced it before; that is, if he dated the present from two weeks ago to-night. It was then that the letter had been handed to him in Chicago, and it had been a weight upon his soul and a prick to his conscience ever since. Once or twice he had made up his mind to destroy it, but each time he had repented at the last moment. In a sudden revulsion at his weakness he pulled himself together, crumpled the dirty missive into a ball, and flung it out upon the white rim of beach.

At this action there came a quick movement in the dense wall of verdure behind him. Noiselessly the tangle of vines separated and a head thrust itself out in time to see the bit of paper fall short of the water's edge. Then the head shot back as swiftly and as silently as a serpent's. Perhaps Captain Plum heard the gloating chuckle that followed the movement. If so he thought it only some night bird in the brush.

"Heigh-ho!" he exclaimed with some return of his old cheer, "it's about time we were starting!" He jumped to his feet and began brushing the sand from his clothes. When he had done, he walked out upon the rim of beach and stretched himself until his arm-bones cracked.

Again the hidden head shot forth from its concealment. A sudden turn and Captain Plum would certainly have been startled. For it was a weird object, this spying head; its face dead-white against the dense green of the verdure, with shocks of long white hair hanging down on each side, framing between them a pair of eyes that gleamed from cavernous sockets, like black glowing beads. There was unmistakable fear, a tense anxiety in those glittering eyes as Captain Plum walked toward the paper, but when he paused and stretched himself, the sole of his boot carelessly trampling the discarded letter, the head disappeared again and there came another satisfied bird-like chuckle from the gloom of the thicket.

Captain Plum now put on his coat, buttoned it close to conceal the weapons in his belt, and walked along the narrow water-run that crept like a white ribbon between the lake and the island wilderness. No sooner had he disappeared than the bushes and vines behind the rock were torn asunder and a man wormed his way through them. For an instant he paused, listening for returning footsteps, and then with startling agility darted to the beach and seized the crumpled letter.

The person who for the greater part of the afternoon had been spying upon Captain Plum from the security of the thicket was to all appearances a very small and a very old man, though there was something about him that seemed to belie a first guess at his age. His face was emaciated; his hair was white and hung in straggling masses on his shoulders; his hooked nose bore apparently the infallible stamp of extreme age. Yet there was a strange and uncanny strength and quickness in his movements. There was no stoop to his shoulders. His head was set squarely. His eyes were as keen as steel. It would have been impossible to have told whether he was fifty or seventy. Eagerly he smoothed out the abused missive and evidently succeeded even in the failing light, in deciphering much of it, for the glimmer of a smile flashed over his thin features as he thrust the paper into his pocket.

Without a moment's hesitation he set out on the trail of Captain Plum. A quarter of a mile down the path he overtook the object of his pursuit.

"Ah, how do you do, sir?" he greeted as the younger man turned about upon hearing his approach. "A mighty fast pace you're setting for an old man, sir!" He broke into a laugh that was not altogether unpleasant, and boldly held out a hand. "We've been expecting you, but—not in this way. I hope there's nothing wrong?"

Captain Plum had accepted the proffered hand. Its coldness and the singular appearance of the old man who had come like an apparition chilled him. In a moment, however, it occurred to him that he was a victim of mistaken identity. As far as he knew there was no one on Beaver Island who was expecting him. To the best of his knowledge he was a fool for being there. His crew aboard the sloop had agreed upon that point with extreme vehemence and, to a man, had attempted to dissuade him from the mad project upon which he was launching himself among the Mormons in their island stronghold. All this came to him while the little old man was looking up into his face, chuckling, and shaking his hand as if he were one of the most important and most greatly to be desired personages in the world.

"Hope there's nothing wrong, Cap'n?" he repeated.

"Right as a trivet here, Dad," replied the young man, dropping the cold hand that still persisted in clinging to his own. "But I guess you've got the wrong party. Who's expecting me?"

The old man's face wrinkled itself in a grimace and one gleaming eye opened and closed in an understanding wink.

"Ho, ho, ho!—of course you're not expected. Anyway, you're not expected to be expected! Cautious—a born general—mighty clever thing to do. Strang should appreciate it." The old man gave vent to his own approbation in a series of inimitable chuckles. "Is that your sloop out there?" he inquired interestedly.

Something in the strangeness of the situation began to interest Captain Plum. He had planned a little adventure of his own, but here was one that promised to develop into something more exciting. He nodded his head.

"That's her."

"Splendid cargo," went on the old man. "Splendid cargo, eh?"

"Pretty fair."

"Powder in good shape, eh?"

"Dry as tinder."

"And balls—lots of balls, and a few guns, eh?"

"Yes, we have a few guns," said Captain Plum. The old man noted the emphasis, but the darkness that had fast settled about them hid the added meaning that passed in a curious look over the other's face.

"Odd way to come in, though—very odd!" continued the old man, gurgling and shaking as if the thought of it occasioned him great merriment. "Very cautious. Level business head. Want to know that things are on the square, eh?"

"That's it!" exclaimed Captain Plum, catching at the proffered straw. Inwardly he was wondering when his feet would touch bottom. Thus far he had succeeded in getting but a single grip on the situation. Somebody was expected at Beaver Island with powder and balls and guns. Well, he had a certain quantity of these materials aboard his sloop, and if he could make an agreeable bargain—

The old man interrupted the plan that was slowly forming itself in Captain Plum's puzzled brain.

"It's the price, eh?" He laughed shrewdly. "You want to see the color of the gold before you land the goods. I'll show it to you. I'll pay you the whole sum to-night. Then you'll take the stuff where I tell you to. Eh? Isn't that so?" He darted ahead of Captain Plum with a quick alert movement. "Will you please follow me, sir?"

For an instant Captain Plum's impulse was to hold back. In that instant it suddenly occurred to him that he was lending himself to a rank imposition. At the same time he was filled with a desire to go deeper into the adventure, and his blood thrilled with the thought of what it might hold for him.

"Are you coming, sir?"

The little old man had stopped a dozen paces away and turned expectantly.

"I tell you again that you've got the wrong man, Dad!"

"Will you follow me, sir?"

"Well, if you'll have it so—damned if I won't!" cried Captain Plum. He felt that he had relieved his conscience, anyway. If things should develop badly for him during the next few hours no one could say that he had lied. So he followed light-heartedly after the old man, his eyes and ears alert, and his right hand, by force of habit, reaching under his coat to the butt of his pistol. His guide said not another word until they had traveled for half an hour along a twisting path and stood at last on the bald summit of a knoll from which they could look down upon a number of lights twinkling dimly a quarter of a mile away. One of these lights gleamed above all the others, like a beacon set among fireflies.

"That's St. James," said the old man. His voice had changed. It was low and soft, as though he feared to speak above a whisper.

"St. James!"

The young man at his side gazed down silently upon the scattered lights, his heart throbbing in a sudden tumult of excitement. He had set out that day with the idea of resting his eyes on St. James. In its silent mystery the town now lay at his feet.

"And that light—" spoke the old man. He pointed a trembling arm toward the glare that shone more powerfully than the others. "That light marks the sacred home of the king!" His voice had again changed. A metallic hardness came into it, his words were vibrant with a strange excitement which he strove hard to conceal. It was still light enough for Captain Plum to see that the old man's black, beady eyes were startlingly alive with newly aroused emotion.

"You mean—"

"Strang!"

He started rapidly down the knoll and there floated back to Captain Plum the soft notes of his meaningless chuckle. A dozen rods farther on his mysterious guide turned into a by-path which led them to another knoll, capped by a good-sized building made of logs. There sounded the grating of a key in a lock, the shooting of a bolt, and a door opened to admit them.

"You will pardon me if I don't light up," apologized the old man as he led the way in. "A candle will be sufficient. You know there must be privacy in these matters—always. Eh? Isn't that so?"

Captain Plum followed without reply. He guessed that the cabin was made up of one large room, and that at the present time, at least, it possessed no other occupant than the singular creature who had guided him to it.

"It is just as well, on this particular night, that no light is seen at the window," continued the old man as he rummaged about a table for a match and a candle. "I have a little corner back here that a candle will brighten up nicely and no one in the world will know it. Ho, ho, ho!—how nice it is to have a quiet little corner sometimes! Eh, Captain Plum?"

At the sound of his name Captain Plum started as though an unexpected hand had suddenly been laid upon him. So he was expected, after all, and his name was known! For a moment his surprise robbed him of the power of speech. The little old man had lighted his candle, and, grinning back over his shoulder, passed through a narrow cut in the wall that could hardly be called a door and planted his light on a table that stood in the center of a small room, or closet, not more than five feet square. Then he coolly pulled Captain Plum's old letter from his pocket and smoothed it out in the dim light.

"Be seated, Captain Plum; right over there—opposite me. So!"

He continued for a moment to smooth out the creases in the letter and then proceeded to read it with as much assurance as though its owner were a thousand miles away instead of within arm's reach of him. Captain Plum was dumfounded. He felt the hot blood rushing to his face and his first impulse was to recover the crumpled paper and demand something more than an explanation. In the next instant it occurred to him that this action would probably spoil whatever possibilities his night's adventure might have for him. So he held his peace. The old man was so intent in his perusal of the letter that the end of his hooked nose almost scraped the table. He went over the dim, partly obliterated words line by line, chuckling now and then, and apparently utterly oblivious of the other's presence. When he had come to the end he looked up, his eyes glittering with unbounded satisfaction, carefully folded the letter, and handed it to Captain Plum.

"That's the best introduction in the world, Captain Plum—the very best! Ho, ho!—it couldn't be better. I'm glad I found it." He chuckled gleefully, and rested his ogreish head in the palms of his skeleton-like hands, his elbows on the table. "So you're going back home—soon?"

"I haven't made up my mind yet, Dad," responded Captain Plum, pulling out his pipe and tobacco. "You've read the letter pretty carefully, I guess. What would you do?"

"Vermont?" questioned the old man shortly.

"That's it."

"Well, I'd go, and very soon, Captain Plum, very soon, indeed. Yes, I'd hurry!" The old man jumped up with the quickness of a cat. So sudden was his movement that it startled Captain Plum, and he dropped his tobacco pouch. By the time he had recovered this article his strange companion was back in his seat again holding a leather bag in his hand. Quickly he untied the knot at its top and poured a torrent of glittering gold pieces out upon the table.

"Business—business and gold," he gurgled happily, rubbing his thin hands and twisting his fingers until they cracked. "A pretty sight, eh, Captain Plum? Now, to our account! A hundred carbines, eh? And a thousand of powder and a ton of balls. Or is it in lead? It doesn't make any difference—not a bit. It's three thousand, that's the account, eh?" He fell to counting rapidly.

For a full minute Captain Plum remained in stupefied bewilderment, silenced by the sudden and unexpected turn his adventure had taken. Fascinated, he watched the skeleton fingers as they clinked the gold pieces. What was the mysterious plot into which he had allowed himself to be drawn? Why were a hundred guns and a ton and a half of powder and balls wanted by the Mormons of Beaver Island? Instinctively he reached out and closed his hand over the counting fingers of the old man. Their eyes met. And there was a shrewd, half-understanding gleam in the black orbs that fixed Captain Plum in an unflinching challenge. For a little space there was silence. It was Captain Plum who broke it.

"Dad, I'm going to tell you for the third and last time that you've made a mistake. I've got eight of the best rifles in America aboard my sloop out there. But there's a man for every gun. And I've got something hidden away underdeck that would blow up St. James in half an hour. And there is powder and ball for the whole outfit. But that's all. I'll sell you what I've got—for a good price. Beyond that you've got the wrong man!"

He settled back and blew a volume of smoke from his pipe. For another half minute the old man continued to look at him, his eyes twinkling, and then he fell to counting again.

Captain Plum was not given over to the habit of cursing. But now he jumped to his feet with an oath that jarred the table. The old man chuckled. The gold pieces clinked between his fingers. Coolly he shoved two glittering piles alongside the candle-stick, tumbled the rest back into the leather bag, deliberately tied the end, and smiled up into the face of the exasperated captain.

"To be sure you're not the man," he said, nodding his head until his elf-locks danced around his face. "Of course you're not the man. I know it—ho, ho! you can wager that I know it! A little ruse of mine, Captain Plum. Pardonable—excusable, eh? I wanted to know if you were a liar. I wanted to see if you were honest."

With a gasp of astonishment Captain Plum sank back into the chair. His jaw dropped and his pipe was held fireless in his hand.

"The devil you say!"

"Oh, certainly, certainly, if you wish it," chuckled the little man, in high humor. "I would have visited your sloop to-day, Captain Plum, if you hadn't come ashore so opportunely this morning. Ho, ho, ho! a good joke, eh? A mighty good joke!"

Captain Plum regained his composure by relighting his pipe. He heard the chink of gold pieces and when he looked again the two piles of money were close to the edge of his side of the table.

"That's for you, Captain Plum. There's just a thousand dollars in those two piles." There was tense earnestness now in the old man's face and voice. "I've imposed on you," he continued, speaking as one who had suddenly thrown off a disguise. "If it had been any other man it would have been the same. I want help. I want an honest man. I want a man whom I can trust. I will give you a thousand dollars if you will take a package back to your vessel with you and will promise to deliver it as quickly as you can."

"I'll do it!" cried Captain Plum. He jumped to his feet and held out his hand. But the old man slipped from his chair and darted swiftly out into the blackness of the adjoining room. As he came back Captain Plum could hear his insane chuckling.

"Business—business—business—" he gurgled. "Eh, Captain Plum? Did you ever take an oath?" He tossed a book on the table. It was the Bible.

Captain Plum understood. He reached for the book and held it under his left hand. His right he lifted above his head, while a smile played about his lips.

"I suppose you want to place me under oath to deliver that package," he said.

The old man nodded. His eyes gleamed with a feverish glare. A sudden hectic flush had gathered in his death-like cheeks. He trembled. His voice rose barely above a whisper.

"Repeat," he commanded. "I, Captain Nathaniel Plum, do solemnly swear before God—"

A thrilling inspiration shot into Captain Plum's brain.

"Hold!" he cried. He lowered his hand. With something that was almost a snarl the old man sprang back, his hands clenched. "I will take this oath upon one other consideration," continued Captain Plum. "I came to Beaver Island to see something of the life and something of the people of St. James. If you, in turn, will swear to show me as much as you can to-night I will take the oath."

The old man was beside the table again in an instant.

"I will show it to you—all—all—" he exclaimed excitedly. "I will show it to you—yes, and swear to it upon the body of Christ!"

Captain Plum lifted his hand again and word by word repeated the oath. When it was done the other took his place.

"Your name?" asked Captain Plum.

A change scarcely perceptible swept over the old man's face.

"Obadiah Price."

"But you are a Mormon. You have the Bible there?"

Again the old man disappeared into the adjoining room. When he returned he placed two books side by side and stood them on edge so that he might clasp both between his bony fingers. One was the Bible, the other the Book of the Mormons. In a cracked, excited voice he repeated the strenuous oath improvised by Captain Plum.

"Now," said Captain Plum, distributing the gold pieces among his pockets, "I'll take that package."

This time the old man was gone for several minutes. When he returned he placed a small package tightly bound and sealed into his companion's hand.

"More precious than your life, more priceless than gold," he whispered tensely, "yet worthless to all but the one to whom it is to be delivered."

There were no marks on the package.

"And who is that?" asked Captain Plum.

The old man came so close that his breath fell hot upon the young man's cheek. He lifted a hand as though to ward sound from the very walls that closed them in.

"Franklin Pierce, President of the United States of America!"

Hardly had the words fallen from the lips of Obadiah Price than the old man straightened himself and stood as rigid as a gargoyle, his gaze penetrating into the darkness of the room beyond Captain Plum, his head inclined slightly, every nerve in him strained to a tension of expectancy. His companion involuntarily gripped the butt of his pistol and faced the narrow entrance through which they had come. In the moment of absolute silence that followed there came to him, faintly, a sound, unintelligible at first, but growing in volume until he knew that it was the last echo of a tolling bell. There was no movement, no sound of breath or whisper from the old man at his back. But when it came again, floating to him as if from a vast distance, he turned quickly to find Obadiah Price with his face lifted, his thin arms flung wide above his head and his lips moving as if in prayer. His eyes burned with a dull glow as though he had been suddenly thrown into a trance. He seemed not to breathe, no vibration of life stirred him except in the movement of his lips. With the third toll of the distant bell he spoke, and to Captain Plum it was as if the passion and fire in his voice came from another being.

"Our Christ, Master of hosts, we call upon Thy chosen people the three blessings of the universe—peace, prosperity and plenty, and upon Strang, priest, king and prophet, the bounty of Thy power!"

Three times more the distant bell tolled forth its mysterious message and when the last echoes had died away the old man's arms dropped beside him and he turned again to Captain Plum.

"Franklin Pierce, President of the United States of America," he repeated, as though there had been no interruption since his companion's question. "The package is to be delivered to him. Now you must excuse me. An important matter calls me out for a short time. But I will be back soon—oh, yes, very soon. And you will wait for me. You will wait for me here, and then I will take you to St. James."

He was gone in a quick hopping way, like a cricket, and the last that Captain Plum saw of him was his ghostly face turned back for an instant in the darkness of the next room, and after that the soft patter of his feet and the strange chuckle in his throat traveled to the outer door and died away as he passed out into the night. Nathaniel Plum was not a man to be easily startled, but there was something so unusual about the proceedings in which he was as yet playing a blind part that he forgot to smoke, which was saying much. Who was the old man? Was he mad? His eyes scanned the little room and an exclamation of astonishment fell from his lips when he saw the leather bag, partly filled with gold, lying where his mysterious acquaintance had dropped it. Surely this was madness or else another ruse to test his honesty. The discovery thrilled him. It was wonderfully quiet out in that next room and very dark. Were hidden eyes guarding that bag? Well, if so, he would give their owner to understand that he was not a thief. He rose from his chair and moved toward the bag, lifted it in his hand, and tossed it back again so that the gold in it chinked loudly. Then he went to the narrow aperture and blocked it with his body and listened until he knew that if there had been human life in the room he would have heard it.

The outer door was open and through it there came to him the soft breath of the night air and the sweetness of balsam and wild flowers. It struck him that it would be pleasanter waiting outside than in, and it would undoubtedly make no difference to Obadiah Price. In front of the cabin he found the stump of a log and seating himself on it where the clear light of the stars fell full upon him he once more began his interrupted smoke. It seemed to him that he had waited a long time when he heard the sound of footsteps. They came rapidly as if the person was half running. Hardly had he located the direction of the sound when a figure appeared in the opening and hurried toward the door of the cabin. A dozen yards from him it paused for a moment and turned partly about, as if inspecting the path over which it had come. With a greeting whistle Captain Plum jumped to his feet. He heard a little throat note, which was not the chuckling of Obadiah Price, and the figure ran almost into his arms. A sudden knowledge of having made a mistake drew Captain Plum a pace backward. For scarcely more than five seconds he found himself staring into the white terrified face of a girl. Eyes wide and glowing with sudden fright met his own. Instinctively he lifted his hand to his hat, but before he could speak the girl sprang back with a low cry and ran swiftly down the path that led into the gloom of the woods.

For several minutes Captain Plum stood as if the sudden apparition had petrified him. He listened long after the sound of retreating footsteps had died away. There remained behind a faint sweet odor of lilac which stirred his soul and set his blood tingling. It was a beautiful face that he had seen. He was sure of that and yet he could have given no good verbal proof of it. Only the eyes and the odor of lilac remained with him and after a little the lilac drifted away. Then he went back to the log and sat down. He smiled as he thought of the joke that he had unwittingly played on Obadiah. From his knowledge of the Beaver Island Mormons he was satisfied that the old man who displayed gold in such reckless profusion was anything but a bachelor. In all probability this was one of his wives and the cabin behind him, he concluded, was for some reason isolated from the harem. "Evidently that little Saintess is not a flirt," he concluded, "or she would have given me time to speak to her."

The continued absence of Obadiah Price began to fill Captain Plum with impatience. After an hour's wait he reentered the cabin and made his way to the little room, where the candle was still burning dimly. To his astonishment he beheld the old man sitting beside the table. His thin face was propped between his hands and his eyes were closed as if he was asleep. They shot open instantly on Captain Plum's appearance.

"I've been waiting for you, Nat," he cried, straightening himself with spring-like quickness. "Waiting for you a long time, Nat!" He rubbed his hands and chuckled at his own familiarity. "I saw you out there enjoying yourself. What did you think of her, Nat?" He winked with such audacious glee that, despite his own astonishment, Captain Plum burst into a laugh. Obadiah Price held up a warning hand. "Tut, tut, not so loud!" he admonished. His face was a map of wrinkles. His little black eyes shone with silent laughter. There was no doubt but that he was immensely pleased over something. "Tell me, Nat—why did you come to St. James?"

He leaned forward over the table, his odd white head almost resting on it, and twiddled his thumbs with wonderful rapidity. "Eh, Nat?" he urged. "Why did you come?"

"Because it was too hot and uninteresting lying out there in a calm, Dad," replied the master of the Typhoon. "We've been roasting for thirty-six hours without a breath to fill our sails. I came over to see what you people are like. Any harm done?"

"Not a bit, not a bit—yet," chuckled the old man. "And what's your business, Nat?"

"Sailing—mostly."

"Ho, ho, ho! of course, I might have known it! Sailing—mostly. Why, certainly you sail! And why do you carry a pistol on one side of you and a knife on the other, Nat?"

"Troublous times, Dad. Some of the fisher-folk along the Northern End aren't very scrupulous. They took a cargo of canned stuffs from me a year back."

"And what use do you make of the four-pounder that's wrapped up in tarpaulin under your deck, Nat? And what in the world are you going to do with five barrels of gunpowder?"

"How in blazes—" began Captain Plum.

"O, to be sure, to be sure—they're for the fisher-folk," interrupted Obadiah Price. "Blow 'em up, eh, Nat? And you seem to be a young man of education, Nat. How did you happen to make a mistake in your count? Haven't you twelve men aboard your sloop instead of eight, Nat? Aren't there twelve, instead of eight? Eh, Nat?"

"The devil take you!" cried Captain Plum, leaping suddenly to his feet, his face flaming red. "Yes, I have got twelve men and I've got a gun in tarpaulin and I've got five barrels of gunpowder! But how in the name of Kingdom-Come did you find it out?"

Obadiah Price came around the end of the table and stood so close to Captain Plum that a person ten feet away could not have heard him when he spoke.

"I know more than that, Nat," he whispered. "Listen! A little while ago—say two weeks back—you were becalmed off the head of Beaver Island, and one dark night you were boarded by two boat-loads of men who made you and your crew prisoners, robbed you of everything you had,—and the next day you went back to Chicago. Eh?"

Nathaniel stood speechless.

"And you made up your mind the pirates were Mormons, enlisted some of your friends, armed your ship—and you're back here to make us settle. Isn't it so, Nat?"

The little old man was rubbing his hands eagerly, excitedly.

"You tried to get the revenue cutter Michigan to come down with you, but they wouldn't—ho, ho, they wouldn't! One of our friends in Chicago sent quick word ahead of you to tell me all about it, and—Strang, the king, doesn't know!"

He spoke the last words in intense earnestness.

Then, suddenly, he held out his hand.

"Young man, will you shake hands with me? Will you shake hands?—and then we will go to St. James!"

Captain Plum thrust out a hand and the old man gripped it. The thin fingers tightened like cold clamps of steel. For a moment the face of Obadiah Price underwent a strange change. The hardness and glitter went out of his eyes and in place there came a questioning, almost an appealing, look. His tense mouth relaxed. It was as if he was on the point of surrendering to some emotion which he was struggling to stifle. And Nathaniel, meeting those eyes, felt that somewhere within him had been struck a strange chord of sympathy, something that made this little old man more than a half-mad stranger to him, and involuntarily the grip of his fingers tightened around those of his companion.

"Now we will go to St. James, Captain Plum!"

He attempted to withdraw his hand but Captain Plum held to it.

"Not yet!" he exclaimed. "There are two or three things which your friend didn't tell you, Obadiah Price!"

Nathaniel's eyes glittered dangerously.

"When I left ship this morning I gave explicit orders to Casey, my mate."

He gazed steadily into the old man's unflinching eyes.

"I said something like this: 'Casey, I'm going to see Strang before I come back. If he's willing to settle for five thousand, we'll call it off. And if he isn't—why, we'll stand out there a mile and blow St. James into hell! And if I don't come back by to-morrow at sundown, Casey, you take command and blow it to hell without me!' So, Obadiah Price, if there's treachery—"

The old man clutched at his hands with insane fierceness.

"There will be no treachery, Nat, I swear to God there will be no treachery! Come, we will go—"

Still Captain Plum hesitated.

"Who are you? Whom am I to follow?"

"A member of our holy Council of Twelve, Nat, and lord high treasurer of His Majesty, King Strang!"

Before Captain Plum could recover from the surprise of this whispered announcement the little old man had freed himself and was pattering swiftly through the darkness of the next room. The master of the Typhoon followed close behind him. Outside the councilor hesitated for a moment, as if debating which route to take, and then with a prodigious wink at Captain Plum and a throatful of his inimitable chuckles, chose the path down which his startled visitor of a short time before had fled. For fifteen minutes this path led between thick black walls of forest verdure. Obadiah Price kept always a few paces ahead of his companion and spoke not a word. At the end of perhaps half a mile the path entered into a large clearing on the farther side of which Nathaniel caught the glimmer of a light. They passed close to this light, which came from the window of a large square house built of logs, and Captain Plum became suddenly conscious that the air was filled with the redolent perfume of lilac. With half a dozen quick strides he overtook the councilor and caught him by the arm.

"I smell lilac!" he exclaimed.

"Certainly, so do I," replied Obadiah Price. "We have very fine lilacs on the island."

"And I smelled lilac back there," continued Nathaniel, still holding to the old man's arm, and pointing a thumb over his shoulder. "I smelled 'em back there, when—"

"Ho, ho, ho!" chuckled the councilor softly. "I don't doubt it, Nat, I don't doubt it. She is very fond of lilacs. She wears the flowers very often."

He pulled himself away and Captain Plum could hear his queer chuckling for some time after. Soon they entered the gloom of the woods again and a little later came out into another clearing and Nathaniel knew that it was St. James that lay at his feet. The lights of a few fishing boats were twinkling in the harbor, but for the most part the town was dark. Here and there a window shone like a spot of phosphorescent yellow in the dismal gloom and the great beacon still burned steadily over the home of the prophet.

"Ah, it is not time," whispered Obadiah. "It is still too early." He drew his companion out of the path which they had followed and sat himself down on a hummock a dozen yards away from it, inviting Nathaniel by a pull of the sleeve to do the same. There were three of these hummocks, side by side, and Captain Plum chose the one nearest the old man and waited for him to speak. But the councilor did not open his lips. Doubled over until his chin rested almost upon the sharp points of his knees, he gazed steadily at the beacon, and as he looked it shuddered and grew dark, like a firefly that suddenly closes its wings. With a quick spring the councilor straightened himself and turned to the master of the Typhoon.

"You have a good nose, Nat," he said, "but your ears are not so good. Sh-h-h-h!" He lifted a hand warningly and nodded sidewise toward the path. Captain Plum listened. He heard low voices and then footsteps—voices that were approaching rapidly, and were those of women, and footsteps that were almost running. The old man caught him by the arm and as the sounds came nearer his grip tightened.

"Don't frighten them, Nat. Get down!"

He crouched until he was only a part of the shadows of the ground and following his example Nathaniel slipped between two of the knolls. A few yards away the sound of the voices ceased and there was a hesitancy in the soft tread of the approaching steps. Slowly, and now in awesome silence, two figures came down the path and when they reached a point opposite the hummocks Nathaniel could see that they turned their faces toward them and that for a brief space there was something of terror in the gleam he caught of their eyes. In a moment they had passed. Then he heard them running.

"They saw us!" Captain Plum exclaimed.

Obadiah hopped to his feet and rubbed his hands with great glee. "What a temptation, Nat!" he whispered. "What a temptation to frighten them out of their wits! No, they didn't see us, Nat—they didn't see us. The girls are always frightened when they pass these graves. Some day—"

"Graves!" almost shouted the master of the Typhoon. "Graves—and we sitting on 'em!"

"That's all right, Nat—that's all right. They're my graves, so we're welcome to sit on them. I often come here and sit for hours at a time. They like to have me, especially little Jean—the middle one. Perhaps I'll tell you about Jean before you go away."

If Captain Plum had been watching him he would have seen that soft mysterious light again shining in the old councilor's eyes. But now Nathaniel stood erect, his nostrils sniffing the air, catching once more the sweet scent of lilac. He hurried out into the opening, with the old man close behind him, and peered down into the starlit gloom into which the two girls had disappeared. The lovely face that had appeared to him for an instant at Obadiah's cabin began to haunt him. He was sure now that his sudden appearance had not been the only cause of its terror, and he felt that he should have called out to her or followed until he had overtaken her. He could easily have excused his boldness, even if the councilor had been watching him from the cabin door. He was certain that she had passed very near to him again and that the fright which Obadiah had attempted to explain was not because of the graves. He swung about upon his companion, determined to ask for an explanation. The latter seemed to divine his thought.

"Don't let a little scent of lilac disturb you so, young man," he said with singular coldness. "It may cause you great unpleasantness." He went ahead and Nathaniel followed him, assured that the old man's words and the way in which he had spoken them no longer left a doubt as to the identity of his night visitor. She was one of the councilor's wives, so he thought, and his own interest in her was beginning to have an irritating effect. In other words Obadiah was becoming jealous.

For some time there was silence between the two. Obadiah Price now walked with extreme slowness and along paths which seemed to bring him no nearer to the town below. Nathaniel could see that he was absorbed in thoughts of his own, and held his peace. Was it possible that he had spoiled his chances with the councilor because of a pretty face and a bunch of lilacs? The thought tickled Captain Plum despite the delicacy of his situation and he broke into an involuntary laugh. The laugh brought Obadiah to a halt as suddenly as though some one had thrust a bayonet against his breast.

"Nat, you've got good red blood in you," he cried, whirling about. "D'ye suppose you can hate as well as love?"

"Lord deliver us!" exclaimed the astonished Captain Plum. "Hate—love—what the—"

"Yes, hate," repeated the old man with fierce emphasis, so close that his breath struck Nathaniel's face. "You can love a pretty face—and you can hate. I know you can. If you couldn't I would send you back to your sloop with the package to-night. But as it is I am going to relieve you of your oath. Yes, Nat, I give you back your oath—for a time."

Nathaniel stepped a pace back and put his hands on his pockets as if to protect the gold there.

"You mean that you want to call off our bargain?" he asked.

The councilor rubbed his hands until the friction of them sent a shiver up Nathaniel's back. "Not that, Nat—O, no, not that! The bargain is good. The gold is yours. You must deliver the package. But you need not do it immediately. Understand? I am lonely back there in my shack. I want company. You must stay with me a week. Eh? Lilacs and pretty faces, Nat! Ho, ho!—You will stay a week, won't you, Nat?"

He spoke so rapidly and his face underwent so many changes, now betraying the keenest excitement, now wrinkled in an ogreish, bantering grin, now almost pleading in its earnestness, that Nathaniel knew not what to make of him. He looked into the beady eyes, sparkling with passion, and the cat-like glitter of them set his blood tingling. What strange adventure was this old man dragging him into? What were the motives, the reasoning, the plot that lay behind this mysterious creature's apparent faith in him? He tried to answer these things in the passing of a moment before he replied. The councilor saw his hesitancy and smiled.

"I will show you many things of interest, Nat," he said. "I will show you just one to-night. Then you will make up your mind, eh? You need not tell me until then."

He took the lead again and this time struck straight down for the town. They passed a number of houses built of logs and Nathaniel caught narrow gleams of light from between close-drawn curtains. In one of these houses he heard the crying of children, and with a return of his grisly humor Obadiah Price prodded him in the ribs and said,

"Good old Israel Laeng lives there—two wives, one old, one young—eleven children. The Kingdom of Heaven is open to him!" And from a second he heard the sound of an organ, and from still a third there came the laughter and chatter of several feminine voices, and again Obadiah reached out and prodded Nathaniel in the ribs. There was one great, gloomy, long-built place which they passed, without a ray of light to give it life, and the councilor said, "Three widows there, Nat,—fight like cats and dogs. Poor Job killed himself." They avoided the more thickly populated part of the settlement and encountered few people, which seemed to please the councilor. Once they overtook and passed a group of women clad in short skirts and loose waists and with their hair hanging in braids down their backs. For a third time Obadiah nudged Captain Plum.

"It is the king's pleasure that all women wear skirts that come just below the knees," he whispered. "Some of them won't do it and he's wondering how to punish them. To-morrow there's going to be two public whippings. One of the victims is a man who said that if he was a woman he'd die before he put on knee skirts. After he's whipped he is going to be made to wear 'em. By Urim and Thummin, isn't that choice, Nat?"

He shivered with quiet laughter and dived into a great block of darkness where there seemed to be no houses, keeping close beside Nathaniel. Soon they came to the edge of a grove and deep among the trees Captain Plum caught a glimpse of a lighted window. Obadiah Price now began to exhibit unusual caution. He approached the light slowly, pausing every few steps to peer guardedly about him, and when they had come very near to the window he pulled his companion behind a thick clump of shrubbery. Nathaniel could hear the old man's subdued chuckle and he bent his head to catch what he was about to whisper to him.

"You must make no noise, Nat," he warned. "This is the castle of our priest, king and prophet—James Jesse Strang. I am going to show you what you have never seen before and what you will never look upon again. I have sworn upon the Two Books and I will keep my oath. And then—you will answer the question I asked you back there."

He crept out into the darkness of the trees and Nathaniel followed, his heart throbbing with excitement, every sense alert, and one hand resting on the butt of his pistol. He felt that he was nearing the climax of his day's adventure and now, in the last moment of it, his old caution reasserted itself. He knew that he was among a dangerous people, men who, according to the laws of his country, were criminals in more ways than one. He had seen much of their work along the coasts and he had heard of more of it. He knew that this gloom and sullen quiet of St. James hid cut-throats and pirates and thieves. Still there was nothing ahead to alarm him. The old man dodged the gleams of the lighted window and slunk around to the end of the great house. Here, several feet above his head, was another window, small and veiled with the foliage wall. With the assurance of one who had been there before the councilor mounted some object under the window, lifted himself until his chin was on a level with the glass, and peered within. He was there but an instant and then fell back, chuckling and rubbing his hands.

"Come, Nat!"

He stood a little to one side and bowed with mock politeness. For a moment Captain Plum hesitated. Under ordinary circumstances this spying through a window would have been repugnant to him. But at present something seemed to tell him that it was not to satisfy his curiosity alone that Obadiah Price had given him this opportunity. Would a look through that little window explain some of the mysteries of the night?

There came a low whisper in his ear.

"Do you smell lilac, Nat? Eh?"

The councilor was grinning at him. There was a suggestive gleam in his eyes. He rubbed his hands almost fiercely.

In another instant Captain Plum had stepped upon the object beneath the window and parted the leaves. Breathlessly he looked in. A strange scene met his eyes. He was looking into a vast room, illuminated by a huge hanging lamp suspended almost on a level with his head. Under this lamp there was a long table and at the table sat seven women and one man. The man was at the end nearest the window and all that Nat could see was the back of his head and shoulders. But the women were in full view, three on each side of the table and one at the far end. He guessed the man to be Strang; but he stared at the women and as his eyes traveled back to the one facing him at the end of the table he could scarcely repress the exclamation of surprise that rose to his lips. It was the girl whom he had encountered at the councilor's cabin. She was leaning forward as if in an agony of suspense, her eyes on the king, her lips parted, her hands clutching at a great book which lay open before her. Her cheeks were flushed with excitement. And even as he looked Captain Plum saw her head fall suddenly forward upon the table, encircled by her arms. The heavy braid of her hair, partly undone, glistened like red gold in the lamplight. Her slender body was convulsed with sobs. The woman nearest her reached over and laid a caressing hand on the bowed head, but drew it quickly away as if at a sharp command.

In his eagerness Nathaniel thrust his face through the foliage until his nose touched the glass. When the girl lifted her head she straightened back in her chair—and saw him. There came a sudden white fear in her face, a parting of the lips as if she were on the point of crying out, and then, before the others had seen, she looked again at Strang. She had discovered him and yet she had not revealed her discovery! Nathaniel could have shouted for joy. She had seen him, had recognized him! And because she had not cried out she wanted him! He drew his pistol from its holster and waited. If she signaled for him, if she called him, he would burst the window. The girl was talking now and as she talked she lifted her eyes. Nathaniel pressed his face close against the window, and smiled. That would let her know he was a friend. She seemed to answer him with a little nod and he fancied that her eyes glowed with a mute appeal for his assistance. But only for an instant, and then they turned again to the king. Not until that moment did Nathaniel notice upon her bosom a bunch of crumpled lilacs.

From below the iron grip of the councilor dragged him down.

"That's enough," he whispered. "That's enough—for to-night." He saw the pistol in Nathaniel's hand and gave a sudden breathless cry.

"Nat—Nat—"

He caught Captain Plum's free hand in his.

"Tell me this, Obadiah Price," whispered the master of the Typhoon, "who is she?"

The councilor stood on tiptoe to answer.

"They are the six wives of Strang, Nat!"

"But the other?" demanded Nathaniel. "The other—"

"O, to be sure, to be sure," chuckled Obadiah. "The girl of the lilacs, eh? Why, she's the seventh wife, Nat—that's all, the seventh wife!"

So quickly that Obadiah Price might not have counted ten before it had come and gone the significance of his new situation flashed upon Captain Plum as he stood under the king's window. His plans had changed since leaving ship but now he realized that they had become hopelessly involved. He had intended that Obadiah should show him where Strang was to be found, and that later, when ostensibly returning to his vessel, he would visit the prophet in his home. Whatever the interview brought forth he would still be in a position to deliver the councilor's package. Even an hour's bombardment of St. James would not interfere with the fulfilment of his oath. But those few minutes at the king's window had been fatal to the scheme he had built. The girl had seen him. She had not betrayed his presence. She had called to him with her eyes—he would have staked his life on that. What did it all mean? He turned to Obadiah. The old man was grimacing and twisting his hands nervously. He seemed half afraid, cringing, as if fearing a blow. The sight of him set Nathaniel's blood afire. His white face seemed to verify the terrible thought that had leaped into his brain. Suddenly he heard a faint cry—a woman's voice—and in an instant he was back at the window. The girl had risen to her feet and stood facing him. This time, as her eyes met his own, he saw in them a flashing warning, and he obeyed it as if she had spoken to him. As he dropped silently back to the ground the councilor came close to his side.

"That's enough for to-night, Nat," he whispered.

He made as if to slip away but Nathaniel detained him with an emphatic hand.

"Not yet, Dad! I'd like to have a word with—this—"

"With Strang's wife," chuckled Obadiah. "Ho, ho, ho, Nat, you're a rascal!" The old man's face was mapped with wrinkles, his eyes glowed with joyous approbation. "You shall, Nat, you shall! You love a pretty face, eh? You shall meet Mrs. Strang, Nat, and you shall make love to her if you wish. I swear that, too. But not to-night, Nat—not to-night."

He stood a pace away and rubbed his hands.

"There will be no chance to-night, Nat—but to-morrow night, or the next. O, I promise you shall meet her, and make love to her, Nat! Ho, if Strang knew, if Strang only knew!"

There was something so fiendishly gloating in the councilor's attitude, in his face, in the hot glow of his eyes, that for a moment Nathaniel's involuntary liking for the little old man before him turned to abhorrence. The passion, the triumph of the man, convinced him where words had failed. The girl was Strang's wife. His last doubt was dispelled. And because she was Strang's wife Obadiah hated the Mormon prophet. The councilor had spoken with fateful assurance—that he should meet her, that he should make love to her. It was an assurance that made him shudder. As he followed in silence up out of the gloom of the town he strove, but in vain, to find whether sin had lurked in the sweet face that had appealed to him in its misery—whether there had been a flash of something besides terror, besides prayerful entreaty, in the lovely eyes that had met his own. Obadiah spoke no word to break in on his thoughts. Now and then the old man's insane chucklings floated softly to Nathaniel's ears, and when at last they came to the cabin in the forest he broke into a low laugh that echoed weirdly in the great black room which they entered. He lighted another candle and approached a ladder which led through a trap in the ceiling. Without a word he mounted this ladder, and Nathaniel followed him, finding himself a moment later in a small low room furnished with a bed. The councilor placed his candle on a table close beside it and rubbed his hands until it seemed they must burn.

"You will stay—eh, Nat?" he cried, bobbing his head. "Yes, you will stay, and you will give me back the package for a day or two." He retreated to the trap and slid down it as quickly as a rat. "Pleasant dreams to you, Nat, and—O, wait a minute!" Captain Plum could hear him pattering quickly over the floor below. In a moment he was back, thrusting his white grimacing face through the trap and tossed something upon the bed. "She left them last night, Nat. Pleasant dreams, pleasant dreams," and he was gone.

Nathaniel turned to the bed and picked up a faded bunch of lilacs. Then he sat down, loaded his pipe, and smoked until he could hardly see the walls of his little room. From the moment of his landing on the island he turned the events of the day over in his mind. Yet when he arrived at the end of them he was no less mystified than when he began. Who was Obadiah Price? Who was the girl that fate had so mysteriously associated with his movements thus far? What was the plot in which he had accidentally become involved? With tireless tenacity he hung to these questions for hours. That there was a plot of some kind he had not the least doubt. The councilor's strange actions, the oath, the package, and above all the scene in the king's house convinced him of that. And he was sure that Obadiah's night visitor—the girl with the lilacs—was playing a vital part in it.

He plucked at the withered flowers which the old man had thrown him. He could detect their sweet scent above the pungent fumes of tobacco and as Obadiah's triumphant chuckle recurred to him, the gloating joy in his eyes, the passionate tremble of his voice, a grim smile passed over his face. The mystery was easy of solution—if he was willing to reason along certain lines. But he was not willing. He had formed his own picture of Strang's wife and it pleased him to keep it. At moments he half conceded himself a fool, but that did not trouble him. The longer he smoked the more his old confidence and his old recklessness returned to him. He had enjoyed his adventure. The next day he would end it. He would go openly into St. James and have done his business with Strang. Then he would return to his ship. What had he, Captain Plum, to do with Strang's wife?

But even after he had determined on these things his brain refused to rest. He paced back and forth across the narrow room, thinking of the man whom he was to meet to-morrow—of Strang, the one-time schoolmaster and temperance lecturer who had made himself a king, who for seven years had defied the state and nation, and who had made of his island stronghold a hot-bed of polygamy, of licentiousness, of dissolute power. His blood grew hot as he thought again of the beautiful girl who had appealed to him. Obadiah had said that she was the king's wife. Still—

Thoughts flashed into his head which for a time made him forget his mission on the island. In spite of his resolution to keep to his own scheme he found himself, after a little, thinking only of the Mormon king, and the lovely face he had seen through the castle window. He knew much about the man with whom he was to deal to-morrow. He knew that he had been a rival of Brigham Young and that when the exodus of the Mormons to the deserts of the west came he had led his own followers into the North, and that each July, amid barbaric festivities, he was recrowned with a circlet of gold. But the girl! If she was the king's wife why had her eyes called to him for help?

The question crowded Nathaniel's brain with a hundred thrilling pictures. With a shudder he thought of the terrible power the Mormon king held not only over his own people but over the Gentiles of the mainlands as well. With these mainlanders, he regarded Beaver Island as a nest of pirates and murderers. He knew of the depredations of Strang and his people among the fishermen and settlers, of the piratical expeditions of his armed boats, of the dreaded raids of his sheriffs, and of the crimes that made the women of the shores tremble and turn white at the mere mention of his name.

Was it possible that this girl—

Captain Plum did not let himself finish the thought. With a powerful effort he brought himself back to his own business on the island, smoked another pipe, and undressed. He went to bed with the withered lilacs on the table close beside him. He fell asleep with their scent in his nostrils. When he awoke they were gone. He started up in astonishment when he saw what had taken their place. Obadiah had visited him while he slept. The table was spread with a white cloth and upon it was his breakfast, a pot of coffee still steaming, and the whole of a cold baked fowl. Near-by, upon a chair, was a basin of water, soap and a towel. Nathaniel rolled from his bed with a healthy laugh of pleasure. The councilor was at least a courteous host, and his liking for the curious old man promptly increased. There was a sheet of paper on his plate upon which Obadiah had scribbled the following words:

"My dear Nat:—Make yourself at home. I will be away to-day but will see you again to-night. Don't be surprised if somebody makes you a visit."

The "somebody" was heavily underscored and Nathaniel's pulse quickened and a sudden flush of excitement surged into his face as he read the meaning of it. The "somebody" was Strang's wife. There could be no other interpretation. He went to the trap and called down for Obadiah but there was no answer. The councilor had already gone. Quickly eating his breakfast the master of the Typhoon climbed down the ladder into the room below. The remains of the councilor's breakfast were on a table near the door, and the door was open. Through it came a glory of sunshine and the fresh breath of the forest laden with the perfume of wild flowers and balsam. A thousand birds seemed caroling and twittering in the sunlit solitude about the cabin. Beyond this there was no other sound or sign of life. For many minutes Nathaniel stood in the open, his eyes on the path along which he knew that Strang's wife would come—if she came at all. Suddenly he began to examine the ground where the girl had stood the previous night. The dainty imprints of her feet were plainly discernible in the soft earth. Then he went to the path—and with a laugh so loud that it startled the birds into silence he set off with long strides in the direction of St. James. From the footprints in that path it was quite evident that Strang's wife was a frequent visitor at Obadiah's.

At the edge of the forest, from where he could see the log house situated across the opening, Nathaniel paused. He had made up his mind that the girl whom he had seen through the king's window was in some way associated with it. Obadiah had hinted as much and she had come from there on her way to Strang's. But as the prophet's wives lived in his castle at St. James this surely could not be her home. More than ever he was puzzled. As he looked he saw a figure suddenly appear from among the mass of lilac bushes that almost concealed the cabin. An involuntary exclamation of satisfaction escaped him and he drew back deeper among the trees. It was the councilor who had shown himself. For a few moments the old man stood gazing in the direction of St. James as if watching for the approach of other persons. Then he dodged cautiously along the edge of the bushes, keeping half within their cover, and moved swiftly in the opposite direction toward the center of the island. Nathaniel's blood leaped with a desire to follow. The night before he had guessed that Obadiah with his gold and his smoldering passion was not a man to isolate himself in the heart of the forest. Here—across the open—was evidence of another side of his life. In that great square-built domicile of logs, screened so perfectly by flowering lilac, lived Obadiah's wives. Captain Plum laughed aloud and beat the bowl of his pipe on the tree beside him. And the girl lived there—or came from there to the woodland cabin so frequently that her feet had beaten a well-worn path. Had the councilor lied to him? Was the girl he had seen through the King's window one of the seven wives of Strang—or was she the wife of Obadiah Price?

The thought was one that thrilled him. If the girl was the councilor's wife what was the motive of Obadiah's falsehood? And if she was Strang's wife why had her feet—and hers alone with the exception of the old man's—worn this path from the lilac smothered house to the cabin in the woods? The captain of the Typhoon regretted now that he had given such explicit orders to Casey. Otherwise he would have followed the figure that was already disappearing into the forest on the opposite side of the clearing. But now he must see Strang. There might be delay, necessary delay, and if it so happened that his own blundering curiosity kept him on the island until sundown—well, he smiled as he thought of what Casey would do.

Refilling his pipe and leaving a trail of smoke behind him he set out boldly for St. James. When he came to the three graves he stopped, remembering that Obadiah had said they were his graves. A sort of grim horror began to stir at his soul as he gazed on the grass-grown mounds—proofs that the old councilor would inherit a place in the Mormon Heaven having obeyed the injunctions of his prophet on earth. Nathaniel now understood the meaning of his words of the night before. This was the family burying ground of the old councilor.

He walked on, trying in vain to concentrate his mind solely upon the business that was ahead of him. A few days before he would have counted this walk to St. James one of the events of his life. Now it had lost its fascination. Despite his efforts to destroy the vision of the beautiful face that had looked at him through the king's window its memory still haunted him. The eyes, soft with appeal; the red mouth, quivering, and with lips parted as if about to speak to him; the bowed head with its tumbled glory of hair—all had burned themselves upon his soul in a picture too deep to be eradicated. If St. James was interesting now it was because that face was a part of it, because the secret of its life, of the misery that it had confessed to him, was hidden somewhere down there among its scattered log homes.

Slowly he made his way down the slope in the direction of Strang's castle, the tower of which, surmounted by its great beacon, glistened in the morning sun. He would find Strang there. And there would be one chance in a thousand of seeing the girl—if Obadiah had spoken the truth. As he passed down he met men and boys coming up the slope and others moving along at the bottom of it, all going toward the interior of the island. They had shovels or rakes or hoes upon their shoulders and he guessed that the Mormon fields were in that direction; others bore axes; and now and then wagons, many of them drawn by oxen, left the town over the road that ran near the shore of the lake. Those whom he met stared at him curiously, much interested evidently in the appearance of a stranger. Nathaniel paid but small heed to them. As he entered the grove through which the councilor had guided him the night before his eagerness became almost excitement. He approached the great log house swiftly but cautiously, keeping as much from view as possible. As he came under the window through which he had looked upon the king and his wives his heart leaped with anticipation, with hope that was strangely mingled with fear. For only a moment he paused to listen, and notwithstanding the seriousness of his position he could not repress a smile as there came to his ears the crying of children and the high angry voice of a woman. He passed around to the front of the house. The door of Strang's castle was wide open and unguarded. No one had seen his approach; no one accosted him as he mounted the low steps; there was no one in the room into which he gazed a moment later. It was the great hall into which he had spied a few hours previous. There was the long table with the big book on it, the lamp whose light had bathed the girl's head in a halo of glory, the very chair in which he had found her sitting! He was conscious of a throbbing in his breast, a longing to call out—if he only knew her name.

In the room there were four closed doors and it was from beyond these that there came to him the wailing of children. A fifth door was open and through it he saw a cradle gently rocking. Here at last was visible life, or motion at least, and he knocked loudly. Very gradually the cradle ceased its movement. Then it stopped, and a woman came out into the larger room. In a moment Nathaniel recognized her as the one who had placed a caressing hand upon the bowed head of the sobbing girl the night before. Her face was of pathetic beauty. Its whiteness was startling. Her eyes shone with an unhealthy luster, and her dark hair, falling in heavy curls over her shoulder, added to the wonderful pallor of her cheeks.

Nathaniel bowed. "I beg your pardon, madam; I came to see Mr. Strang," he said.

"You will find the king at his office," she replied.

The woman's voice was low, but so sweet that it was like music to the ear. As she spoke she came nearer and a faint flush appeared in the transparency of her cheek.

"Why do you wish to see the king?" she asked.

Was there a tremble of fear in her voice? Even as he looked Nathaniel saw the flush deepen in her cheeks and her eyes light with nervous eagerness.

"I am sent by Obadiah Price," he hazarded.

A flash of relief shot into the woman's face.

"The king is at his office," she repeated. "His office is near the temple."

Nathaniel retired with another bow.

"By thunder, Strang, old boy, you've certainly got an eye for beauty!" he laughed as he hurried through the grove.

"And Obadiah Price must be somebody, after all!"

The Mormon temple was the largest structure in St. James, a huge square building of hewn logs, and Nathaniel did not need to make inquiry to find it. On one side was a two-story building with an outside stairway leading to the upper floor, and a painted sign announced that on this second floor was situated the office of James Jesse Strang, priest, king and prophet of the Mormons. It was still very early and the general merchandise store below was not open. Congratulating himself on this fact, and with the fingers of his right hand reaching instinctively for his pistol butt, Captain Plum mounted the stair. When half way up he heard voices. As he reached the landing at the top he caught the quick swish of a skirt. Another step and he was in the open door. He was not soon enough to see the person who had just disappeared through an opposite door but he knew that it was a woman. Directly in front of him as if she had been expecting his arrival was a young girl, and no sooner had he put a foot over the threshold than she hurried toward him, the most acute anxiety and fear written in her face.

"You are Captain Plum?" she asked breathlessly.

Nathaniel stopped in astonishment.

"Yes, I'm—"

"Then you must hurry—hurry!" cried the girl excitedly. "You have not a moment to lose! Go back to your ship before it is too late! She says they will kill you—"

"Who says so?" thundered Captain Plum. He sprang to the girl's side and caught her by the arm. "Who says that I will be killed? Tell me—who gave you this warning for me?"

"I—I—tell you so!" stammered the young girl. "I—I—heard the king—they will kill you—" Her lips trembled. Nathaniel saw that her eyes were already red from crying. "You will go?" she pleaded.

Nathaniel had taken her hand and now he held it tightly in his own. His head was thrown back, his eyes were upon the door across the room. When he looked again into the girlish face there was flashing joyous defiance in his eyes, and in his voice there was confession of the truth that had suddenly come to overwhelm whatever law of self preservation he might have held unto himself.

"No, my dear, I am not going back to my ship," he spoke softly. "Not unless she who is in that room comes out and bids me go herself!"

Scarce had the words fallen from his lips when there sounded a slow, heavy step on the stair outside. The young girl snatched her hand free and caught Nathaniel by the wrist.

"It is the king!" she whispered excitedly. "It is the king! Quick—you still have time! You must go—you must go—"

She strove to pull him across the room.

"There—through that door!" she urged.

The slowly ascending steps were half way up the stairs. Nathaniel hesitated. He knew that a moment before there had passed through that door one who carried with her the odor of lilac and his heart leaped to its own conclusion who that person was. He had heard the rustle of the girl's skirt. He had seen the last inch of the door close as Strang's wife pulled it after her. And now he was implored to follow! He sprang forward as the heavy steps neared the landing. His hand was upon the latch—when he paused. Then he turned and bent his head close down to the girl.

"No, I won't do it, my dear," he whispered. "Just now it might make trouble for—her."

He lifted his eyes and saw a man looking at him from the doorway. He needed no further proof to assure him that this was Strang the king of the Mormons, for the Beaver Island prophet was painted well in that region which knew the grip and terror of his power. He was a massive man, with the slow slumbering strength of a beast. He was not much under fifty; but his thick beard, reddish and crinkling, his shaggy hair, and the full-fed ruddiness of his face, with its foundation of heavy jaw, gave him a more youthful appearance. There was in his eyes, set deep and so light that they shone like pale blue glass, the staring assurance that is frequently born of power. In his hand he carried a huge metal-knobbed stick.

In an instant Nathaniel had recovered himself. He advanced a step, bowing coolly.

"I am Captain Plum, of the sloop Typhoon," he said. "I called at your home a short time ago and was directed to your office. As a stranger on the island I did not know that you had an office or I would have come here first."

"Ah!"

The king drew his right foot back half a pace and bowed so low that Nathaniel saw only the crown of his hat. When he raised his head the aggressive stare had gone out of his eyes and a welcoming smile lighted up his face as he advanced with extended hand.

"I am glad to see you, Captain Plum."

His voice was deep and rich, filled with that wonderful vibratory power which seems to strike and attune the hidden chords of one's soul. The man's appearance had not prepossessed Nathaniel, but at the sound of his voice he recognized that which had made him the prophet of men. As the warm hand of the king clasped his own Captain Plum knew that he was in the presence of a master of human destinies, a man whose ponderous red-visaged body was simply the crude instrument through which spoke the marvelous spirit that had enslaved thousands to him, that had enthralled a state legislature and that had hypnotized a federal jury into giving him back his freedom when evidence smothered him in crime. He felt himself sinking in the presence of this man and struggled fiercely to regain himself. He withdrew his hand and straightened himself like a soldier.

"I have come to you with a grievance, Mr. Strang," he began. "A grievance which I feel sure you will do your best to right. Perhaps you are aware that some little time ago—about two weeks back—your people boarded my ship in force and robbed me of several thousand dollars' worth of merchandise."

Strang had drawn a step back.

"Aware of it!" he exclaimed in a voice that shook the room. "Aware of it!" The red of his face turned purple and he clenched his free hand in sudden passion. "Aware of it!" He repeated the words, this time so gently that Nathaniel could scarcely hear them, and tapped his heavy stick upon the floor. "No, Captain Plum, I was not aware of it. If I had been—" He shrugged his thick shoulders. The movement, and a sudden gleam of his teeth through his beard, were expressive enough for Nathaniel to understand.

Then the king smiled.

"Are you sure—are you quite sure, Captain Plum, that it was my people who attacked your ship? If so, of course you must have some proof?"

"We were very near to Beaver Island and many miles from the mainland," said Nathaniel. "It could only have been your people."

"Ah!"

Strang led the way to a table at the farther end of the room and motioned Nathaniel to a seat opposite him.

"We are a much persecuted people, Captain Plum, very much persecuted indeed." His wonderful voice trembled with a subdued pathos. "We have answered for many sins that have never been ours, Captain Plum, and among them are robbery, piracy and even murder. The people along the coasts are deadly enemies to us—who would be their friends; they commit crimes in our name and we do not retaliate. It was not my people who waylaid your vessel. They were fishermen, probably, who came from the Michigan shore and awaited their opportunity off Beaver Island. But I shall investigate this; believe me, I shall investigate this fully, Captain Plum!"

Nathaniel felt something like a great choking fist shoot up into his throat. It was not a sensation of fear but of humiliation—the humiliation of defeat, the knowledge of his own weakness in the hands of this man who had so quickly and so surely blocked his claim. His quick brain saw the futility of argument. He possessed no absolute proof and he had thought that he needed none. Strang saw the flash of doubt in his face, the hesitancy in his answer; he divined the working of the other's brain and in his soft voice, purring with friendship, he followed up his triumph.

"I sympathize with you," he spoke gently, "and my sympathy and word shall help you. We do not welcome strangers among us, for strangers have usually proved themselves our enemies and have done us wrong. But to you I give the freedom of our kingdom. Search where you will, at what hours you will, and when you have found a single proof that your stolen property is among my people—when you have seen a face that you recognize as one of the robbers, return to me and I shall make restitution and punish the evil-doers."

So intensely he spoke, so filled with reason and truth were his words, that Nathaniel thrust out his hand in token of acceptance of the king's terms. And as Strang gripped that hand Captain Plum saw the young girl's face over the prophet's shoulder—a face, white as death in its terror, that told him all he had heard was a lie.

"And when you have done with my people," continued the king, "you will go among that other race, along the mainland, where men have thrown off the restraints of society to give loose reign to lust and avarice; where the Indian is brutified that his wife may be intoxicated by compulsion and prostituted by violence before his eyes; where the forest cabins and the streets of towns are filled with half-breeds; where there stalk wretches with withered and tearless eyes, who are in nowise troubled by recollection of robbery, rape and murder. And there you will find whom you are looking for!"

Strang had risen to his feet. His eyes blazed with the fire of smothered hatred and passion and his great voice rolled through his beard, tremulous with excitement, but still deep and rich, like the booming of some melodious instrument. He flung aside his hat as he paced back and forth; his shaggy hair fell upon his shoulders; huge veins stood out upon his forehead—and Nathaniel sat mute as he watched this lion of a man whose great throat quivered with the power that might have stirred a nation—that might have made him president instead of king. He waited for the thunder of that throat and his nerves keyed themselves to meet its bursting passion. But when Strang spoke again it was in a voice as soft and as gentle as a woman's.

"Those are the men who have vilified us, Captain Plum; who have covered us with crimes that we have never committed; who have driven our people into groups that they may be free from depredation; who watch like vultures to despoil our women; wild wifeless men, Captain Plum, who have left families and character behind them and who have sought the wilderness to escape the penalties of law and order. It is they who would destroy us. Go among my own people first, Captain Plum, and find your lost property if you can; and if you can not discover it where in seven years not one child has been born out of wedlock, seek among the Lamanites—and my sheriffs shall follow where you place the crime!"