II

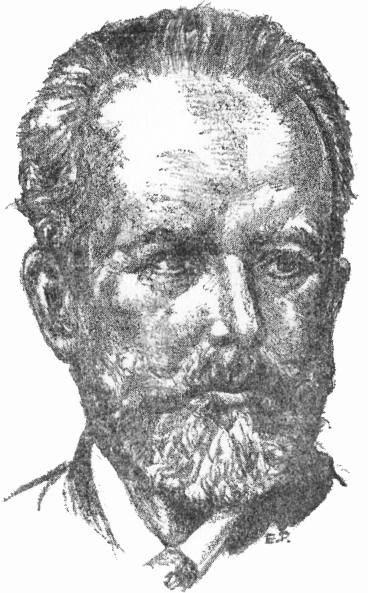

JOHN SEBASTIAN BACH

Project Gutenberg's The World's Great Men of Music, by Harriette Brower

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net

Title: The World's Great Men of Music

Story-Lives of Master Musicians

Author: Harriette Brower

Release Date: August 25, 2004 [EBook #13291]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE WORLD'S GREAT MEN OF MUSIC ***

Produced by Ronald Holder and PG Distributed Proofreaders

The preparation of this volume began with a period of delightful research work in a great musical library. As a honey-bee flutters from flower to flower, culling sweetness from many blossoms, so the compiler of such stories as these must gather facts from many sources—from biography, letters, journals and musical history. Then, impressed with the personality and individual achievement of each composer, the author has endeavored to present his life story.

While the aim has been to make the story-sketches interesting to young people, the author hopes that they may prove valuable to musical readers of all ages. Students of piano, violin or other instruments need to know how the great composers lived their lives. In every musical career described in this book, from the old masters represented by Bach and Beethoven to the musical prophets of our own day, there is a wealth of inspiration and practical guidance for the artist in any field. Through their struggles, sorrows and triumphs, divine melody and harmony came into being, which will bless the world for all time to come.

To learn something of the life and labors of Palestrina, one of the earliest as well as one of the greatest musicians, we must go back in the world's history nearly four hundred years. And even then we may not be able to discover all the events of his life as some of the records have been lost. But we have the main facts, and know that Palestrina's name will be revered for all time as the man who strove to make sacred music the expression of lofty and spiritual meaning.

Upon a hoary spur of the Apennines stands the crumbling town of Palestrina. It is very old now; it was old when Rome was young. Four hundred years ago Palestrina was dominated by the great castle of its lords, the proud Colonnas. Naturally the town was much more important in those days than it is to-day.

At that time there lived in Palestrina a peasant pair, Sante Pierluigi and his wife Maria, who seem to have been an honest couple, and not grindingly poor, since the will of Sante's mother has lately been found, in which she bequeathed a house in Palestrina to her two sons. Besides this she left behind a fine store of bed linen, mattresses and cooking utensils. Maria Gismondi also had a little property.

To this pair was born, probably in 1526, a boy whom they named Giovanni Pierluigi, which means John Peter Louis. This boy, from a tiniest child, loved beauty of sight and sound. And this is not at all surprising, for a child surrounded from infancy by the natural loveliness and glory of old Palestrina, would unconsciously breathe in a sense of beauty and grandeur.

It was soon discovered the boy had a voice, and his mother is said to have sold some land she owned to provide for her son's musical training.

From the rocky heights on which their town was built, the people of Palestrina could look across the Campagna—the great plain between—and see the walls and towers of Rome. At the time of our story, Saint Peter's had withstood the sack of the city, which happened a dozen years before, and Bramante's vast basilica had already begun to rise. The artistic life of Rome was still at high tide, for Raphael had passed away but twenty years before, and Michael Angelo was at work on his Last Judgment.

Though painting and sculpture flourished, music did not keep pace with advance in other arts. The leading musicians were Belgian, Spanish or French, and their music did not match the great achievements attained in the kindred art of the time—architecture, sculpture and painting. There was needed a new impetus, a vital force. Its rise began when the peasant youth John Peter Louis descended from the heights of Palestrina to the banks of the Tiber.

It is said that Tomasso Crinello was the boy's master; whether this is true or not, he was surely trained in the Netherland manner of composition.

The youth, whom we shall now call Palestrina, as he is known by the name of his birthplace, returned from Rome at the age of eighteen to his native town, in 1544, as a practising musician, and took a post at the Cathedral of Saint Agapitus. Here he engaged himself for life, to be present every day at mass and vespers, and to teach singing to the canons and choristers. Thus he spent the early years of his young manhood directing the daily services and drumming the rudiments of music into the heads of the little choristers. It may have been dry and wearisome labor; but afterward, when Palestrina began to reform the music of the church, it must have been of great advantage to him to know so absolutely the liturgy, not only of Saint Peter's and Saint John Lateran, but also that in the simple cathedral of his own small hill-town.

Young Palestrina, living his simple, busy life in his home town, never dreamed he was destined to become a great musician. He married in 1548, when he was about twenty-two. If he had wished to secure one of the great musical appointments in Rome, it was a very unwise thing for him to marry, for single singers were preferred in nine cases out of ten. Palestrina did not seem to realize this danger to a brilliant career, and took his bride, Lucrezia, for pure love. She seems to have been a person after his own heart, besides having a comfortable dowry of her own. They had a happy union, which lasted for more than thirty years.

Although he had agreed to remain for life at the cathedral church of Saint Agapitus, it seems that such contracts could be broken without peril. Thus, after seven years of service, he once more turned his steps toward the Eternal City.

He returned to Rome as a recognized musician. In 1551 he became master of the Capella Giulia, at the modest salary of six scudi a month, something like ten dollars. But the young chapel master seemed satisfied. Hardly three years after his arrival had elapsed, when he had written and printed a book containing five masses, which he dedicated to Pope Julius III. This act pleased the pontiff, who, in January, 1555, appointed Palestrina one of the singers of the Sistine Chapel, with an increased salary.

It seems however, that the Sistine singers resented the appointment of a new member, and complained about it. Several changes in the Papal chair occurred at this time, and when Paul IV, as Pope, came into power, he began at once with reforms. Finding that Palestrina and two other singers were married men, he put all three out, though granting an annuity of six scudi a month for each.

The loss of this post was a great humiliation, which Palestrina found it hard to endure. He fell ill at this time, and the outlook was dark indeed, with a wife and three little children to provide for.

But the clouds soon lifted. Within a few weeks after this unfortunate event, the rejected singer of the Sistine Chapel was created Chapel Master of Saint John Lateran, the splendid basilica, where the young Orlandus Lassus had so recently directed the music. As Palestrina could still keep his six scudi pension, increased with the added salary of the new position, he was able to establish his family in a pretty villa on the Coelian Hill, where he could be near his work at the Lateran, but far enough removed from the turmoil of the city to obtain the quiet he desired, and where he lived in tranquillity for the next five years.

Palestrina spent forty-four years of his life in Rome. All the eleven popes who reigned during this long period honored Palestrina as a great musician. Marcellus II spent a part of his three weeks' reign in showing kindness to the young Chapel master, which the composer returned by naming for this pontiff a famous work, "Mass of Pope Marcellus." Pius IV, who was in power when the mass was performed, praised it eloquently, saying John Peter Louis of Palestrina was a new John, bringing down to the church militant the harmonies of that "new song" which John the Apostle heard in the Holy City. The musician-pope, Gregory XIII, to whom Palestrina dedicated his grandest motets, entrusted him with the sacred task of revising the ancient chant. Pope Sixtus V greatly praised his beautiful mass, "Assumpta est Maria" and promoted him to higher honors.

With this encouragement and patronage, Palestrina labored five years at the Lateran, ten years at Santa Maria Maggiore and twenty three at Saint Peter's. At the last named it was his second term, of course, but it continued from 1571 to his death. He was happy in his work, in his home and in his friends. He also saved quite a little money and was able to give his daughter-in-law, in 1577, 1300 scudi; he is known indeed, to have bought land, vineyards and houses in and about Rome.

All was not a life of sunshine for Palestrina, for he suffered many domestic sorrows. His three promising sons died one after another. They were talented young men, who might have followed in the footsteps of their distinguished father. In 1580 his wife died also. Yet neither poignant sorrow, worldly glory nor ascetic piety blighted his homely affections. At the Jubilee of Pope Gregory XIII, in 1575, when 1500 pilgrims from the town of Palestrina descended the hills on the way to Rome, it was their old townsman, Giovanni Pierluigi, who led their songs, as they entered the Eternal City, their maidens clad in white robes, and their young men bearing olive branches.

It is said of Palestrina that he became the "savior of church music," at a time when it had almost been decided to banish all music from the service except the chant, because so many secular subjects had been set to music and used in church. Things had come to a very difficult pass, until at last the fathers turned to Palestrina, desiring him to compose a mass in which sacred words should be heard throughout. Palestrina, deeply realizing his responsibility, wrote not only one but three, which, on being heard, pleased greatly by their piety, meekness, and beautiful spirit. Feeling more sure of himself, Palestrina continued to compose masses, until he had created ninety-three in all. He also wrote many motets on the Song of Solomon, his Stabat Mater, which was edited two hundred and fifty years later by Richard Wagner, and his lamentations, which were composed at the request of Sixtus V.

Palestrina's end came February 2, 1594. He died in Rome, a devout Christian, and on his coffin were engraved the simple but splendid words: "Prince of Music."

Away back in 1685, almost two hundred and fifty years ago, one of the greatest musicians of the world first saw the light, in the little town of Eisenach, nestling on the edge of the Thuringen forest. The long low-roofed cottage where little Johann Sebastian Bach was born, is still standing, and carefully preserved.

The name Bach belonged to a long race of musicians, who strove to elevate the growing art of music. For nearly two hundred years there had been organists and composers in the family; Sebastian's father, Johann Ambrosius Bach was organist of the Lutheran Church in Eisenach, and naturally a love of music was fostered in the home. It is no wonder that little Sebastian should have shown a fondness for music almost from infancy. But, beyond learning the violin from his father, he had not advanced very far in his studies, when, in his tenth year he lost both his parents and was taken care of by his brother Christoph, fourteen years older, a respectable musician and organist in a neighboring town. To give his little brother lessons on the clavier, and send him to the Lyceum to learn Latin, singing and other school subjects seemed to Christoph to include all that could be expected of him. That his small brother possessed musical genius of the highest order, was an idea he could not grasp; or if he did, he repressed the boy with indifference and harsh treatment.

Little Sebastian suffered in silence from this coldness. Fortunately the force of his genius was too great to be crushed. He knew all the simple pieces by heart, which his brother set for his lessons, and he longed for bigger things. There was a book of manuscript music containing pieces by Buxtehude and Frohberger, famous masters of the time, in the possession of Christoph. Sebastian greatly desired to play the pieces in that book, but his brother kept it under lock and key in his cupboard, or bookcase. One day the child mustered courage to ask permission to take the book for a little while. Instead of yielding to the boy's request Christoph became angry, told him not to imagine he could study such masters as Buxtehude and Frohberger, but should be content to get the lessons assigned him.

The injustice of this refusal fired Sebastian with the determination to get possession of the coveted book at all costs. One moonlight night, long after every one had retired, he decided to put into execution a project he had dreamed of for some time.

Creeping noiselessly down stairs he stood before the bookcase and sought the precious volume. There it was with the names of the various musicians printed in large letters on the back in his brother's handwriting. To get his small hands between the bars and draw the book outward took some time. But how to get it out. After much labor he found one bar weaker than the others, which could be bent.

When at last the book was in his hands, he clasped it to his breast and hurried quickly back to his chamber. Placing the book on a table in front of the window, where the moonlight fell full upon it, he took pen and music paper and began copying out the pieces in the book.

This was but the beginning of nights of endless toil. For six months whenever there were moonlight nights, Sebastian was at the window working at his task with passionate eagerness.

At last it was finished, and Sebastian in the joy of possessing it for his very own, crept into bed without the precaution of putting away all traces of his work. Poor boy, he had to pay dearly for his forgetfulness. As he lay sleeping, Christoph, thinking he heard sounds in his brother's room, came to seek the cause. His glance, as he entered the room, fell on the open books. There was no pity in his heart for all this devoted labor, only anger that he had been outwitted by his small brother. He took both books away and hid them in a place where Sebastian could never find them. But he did not reflect that the boy had the memory of all this beautiful music indelibly printed on his mind, which helped him to bear the bitter disappointment of the loss of his work.

When he was fifteen Sebastian left his brother's roof and entered the Latin school connected with the Church of St. Michael at Lüneburg. It was found he had a beautiful soprano voice, which placed him with the scholars who were chosen to sing in the church service in return for a free education. There were two church schools in Lüneburg, and the rivalry between them was so keen, that when the scholars sang in the streets during the winter months to collect money for their support, the routes for each had to be carefully marked out, to prevent collision.

Soon after he entered St. Michael's, Bach lost his beautiful soprano voice; his knowledge of violin and clavier, however, enabled him to keep his place in the school. The boy worked hard at his musical studies, giving his spare time to the study of the best composers. He began to realize that he cared more for the organ than for any other instrument; indeed his love for it became a passion. He was too poor to take lessons, for he was almost entirely self-dependent—a penniless scholar, living on the plainest of fare, yet determined to gain a knowledge of the music he longed for.

One of the great organists of the time was Johann Adam Reinken. When Sebastian learned that this master played the organ in St. Katharine's Church in Hamburg, he determined to walk the whole distance thither to hear him. Now Hamburg was called in those days the "Paradise of German music," and was twenty-five good English miles from the little town of Lüneburg, but what did that matter to the eager lad? Obstacles only fired him to strive the harder for what he desired to attain.

The great joy of listening to such a master made him forget the long tramp and all the weariness, and spurred him on to repeat the journey whenever he had saved a few shillings to pay for food and lodging. On one occasion he lingered a little longer in Hamburg than usual, until his funds were well-nigh exhausted, and before him was the long walk without any food. As he trudged along he came upon a small inn, from the open door of which came a delightful savory odor. He could not resist looking in through the window. At that instant a window above was thrown open and a couple of herrings' heads were tossed into the road. The herring is a favorite article of food in Germany and poor Sebastian was glad to pick up these bits to satisfy the cravings of hunger. What was his surprise on pulling the heads to pieces to find each one contained a Danish ducat. When he recovered from his astonishment, he entered the inn and made a good meal with part of the money; the rest ensured another visit to Hamburg.

After remaining three years in Lüneburg, Bach secured a post as violinist in the private band of Prince Johann Ernst of Saxe-Weimar; but this was only to fill the time till he could find a place to play the instrument he so loved. An opportunity soon came. The old Thuringian town Arnstadt had a new church and a fine new organ. The consistory of the church were looking for a capable organist and Bach's request to be allowed to try the instrument was readily granted.

As soon as they heard him play they offered him the post, with promise of increasing the salary by a contribution from the town funds. Bach thus found himself at the age of eighteen installed as organist at a salary of fifty florins, with thirty thalers in addition for board and lodging, equal, all in all, to less than fifty dollars. In those days this amount was considered a fair sum for a young player. On August 14, 1703, the young organist entered upon his duties, promising solemnly to be diligent and faithful to all requirements.

The requirements of the post fortunately left him plenty of leisure to study. Up to this time he had done very little composing, but now he set about teaching himself the art of composition.

The first thing he did was to take a number of concertos written for the violin by Vivaldi, and set them for the harpsichord. In this way he learned to express himself and to attain facility in putting his thoughts on paper without first playing them on an instrument. He worked alone in this way with no assistance from any one, and often studied till far into the night to perfect himself in this branch of his art.

From the very beginning, his playing on the new organ excited admiration, but his artistic temperament frequently threatened to be his undoing. For the young enthusiast was no sooner seated at the organ to conduct the church music than he forgot that the choir and congregation were depending on him and would begin to improvise at such length that the singing had to stop altogether, while the people listened in mute admiration. Of course there were many disputes between the new organist and the elders of the church, but they overlooked his vagaries because of his genius.

Yet he must have been a trial to that well-ordered body. Once he asked for a month's leave of absence to visit Lübeck, where the celebrated Buxtehude was playing the organ in the Marien Kirche during Advent. Lübeck was fifty miles from Arnstadt, but the courageous boy made the entire journey on foot. He enjoyed the music at Lübeck so much that he quite forgot his promise to return in one month until he had stayed three. His pockets being quite empty, he thought for the first time of returning to his post. Of course there was trouble on his return, but the authorities retained him in spite of all, for the esteem in which they held his gifts.

Bach soon began to find Arnstadt too small and narrow for his soaring desires. Besides, his fame was growing and his name becoming known in the larger, adjacent towns. When he was offered the post of organist at St. Blasius at Mülhausen, near Eisenach, he accepted at once. He was told he might name his own salary. If Bach had been avaricious he could have asked a large sum, but he modestly named the small amount he had received at Arnstadt with the addition of certain articles of food which should be delivered at his door, gratis.

Bach's prospects were now so much improved that he thought he might make a home for himself. He had fallen in love with a cousin, Maria Bach, and they were married October 17, 1707.

The young organist only remained in Mülhausen a year, for he received a more important offer. He was invited to play before Duke Wilhelm Ernst of Weimar, and hastened thither, hoping this might lead to an appointment at Court. He was not disappointed, for the Duke was so delighted with Bach's playing that he at once offered him the post of Court organist.

A wider outlook now opened for Sebastian Bach, who had all his young life struggled with poverty and privation. He was now able to give much time to composition, and began to write those masterpieces for the organ which have placed his name on the highest pinnacle in the temple of music.

In his comfortable Weimar home the musician had the quiet and leisure that he needed to perfect his art on all sides, not only in composition but in organ and harpsichord playing. He felt that he had conquered all difficulties of both instruments, and one day boasted to a friend that he could play any piece, no matter how difficult, at sight, without a mistake. In order to test this statement the friend invited him to breakfast shortly after. On the harpsichord were several pieces of music, one of which, though apparently simple, was really very difficult. His host left the room to prepare the breakfast, while Bach began to try over the music. All went well until he came to the difficult piece which he began quite boldly but stuck in the middle. It went no better after several attempts. As his friend entered, bringing the breakfast, Bach exclaimed:—"You are right. One cannot play everything perfectly at sight,—it is impossible!"

Duke Wilhelm Ernst, in 1714, raised him to the position of Head-Concert Master, a position which offered added privileges. Every autumn he used his annual vacation in traveling to the principal towns to give performances on organ and clavier. By such means he gained a great reputation both as player and composer.

On one of these tours he arrived in Dresden in time to learn of a French player who had just come to town. Jean Marchand had won a great reputation in France, where he was organist to the King at Versailles, and regarded as the most fashionable musician of the day. All this had made him very conceited and overbearing. Every one was discussing the Frenchman's wonderful playing and it was whispered he had been offered an appointment in Dresden.

The friends of Bach proposed that he should engage Marchand in a contest, to defend the musical honor of the German nation. Both musicians were willing; the King promised to attend.

The day fixed for the trial arrived; a brilliant company assembled. Bach made his appearance, and all was ready, but the adversary failed to come. After a considerable delay it was learned that Marchand had fled the city.

In 1717, on his return from Dresden, Bach was appointed Capellmeister to the young Prince Leopold of Anhalt-Cöthen. The Prince was an enthusiastic lover of music, and at Cöthen Bach led a happy, busy life. The Prince often journeyed to different towns to gratify his taste for music, and always took Bach with him. On one of these trips he was unable to receive the news that his wife had suddenly passed away, and was buried before he could return to Cöthen. This was a severe blow to the whole family.

Four years afterward, Bach married again, Anna Magdalena Wülkens was in every way suited for a musician's wife, and for her he composed many of the delightful dances which we now so greatly enjoy. He also wrote a number of books of studies for his wife and his sons, several of whom later became good musicians and composers.

Perhaps no man ever led a more crowded life, though outwardly a quiet one. He never had an idle moment. When not playing, composing or teaching, he would be found engraving music on copper, since that work was costly in those days. Or he would be manufacturing some kind of musical instrument. At least two are known to be of his invention.

Bach began to realize that the Cöthen post, while it gave him plenty of leisure for his work, did not give him the scope he needed for his art. The Prince had lately married, and did not seem to care as much for music as before.

The wider opportunity which Bach sought came when he was appointed director of music in the churches of St. Thomas and St. Nicholas in Leipsic, and Cantor of the Thomas-Schule there. With the Leipsic period Bach entered the last stage of his career, for he retained this post for the rest of his life. He labored unceasingly, in spite of many obstacles and petty restrictions, to train the boys under his care, and raise the standard of musical efficiency in the Schule, as choirs of both churches were recruited from the scholars of the Thomas School.

During the twenty-seven years of life in Leipsic, Bach wrote some of his greatest works, such as the Oratorios of St. Matthew and St. John, and the Mass in B Minor. It was the Passion according to St. Matthew that Mendelssohn, about a hundred years later discovered, studied with so much zeal, and performed in Berlin, with so much devotion and success.

Bach always preferred a life of quiet and retirement; simplicity had ever been his chief characteristic. He was always very religious; his greatest works voice the noblest sentiments of exaltation.

Bach's modesty and retiring disposition is illustrated by the following little incident. Carl Philip Emmanuel, his third son, was cembalist in the royal orchestra of Frederick the Great. His Majesty was very fond of music and played the flute to some extent. He had several times sent messages to Bach by Philip Emmanuel, that he would like to see him. But Bach, intent on his work, ignored the royal favor, until he finally received an imperative command, which could not be disobeyed. He then, with his son Friedmann, set out for Potsdam.

The King was about to begin the evening's music when he learned that Bach had arrived. With a smile he turned to his musicians: "Gentlemen, old Bach has come." Bach was sent for at once, without having time to change his traveling dress. His Majesty received him with great kindness and respect, and showed him through the palace, where he must try the Silbermann pianofortes, of which there were several. Bach improvised on each and the King gave a theme which he treated as a fantasia, to the astonishment of all. Frederick next asked him to play a six part fugue, and then Bach improvised one on a theme of his own. The King clapped his hands, exclaiming over and over, "Only one Bach! Only one Bach!" It was a great evening for the master, and one he never forgot.

Just after completing his great work, The Art of Fugue, Bach became totally blind, due no doubt, to the great strain he had always put upon his eyes, in not only writing his own music, but in copying out large works of the older masters. Notwithstanding this handicap he continued at work up to the very last. On the morning of the day on which he passed away, July 28, 1750, he suddenly regained his sight. A few hours later he became unconscious and passed in sleep.

Bach was laid to rest in the churchyard of St. John's at Leipsic, but no stone marks his resting place. Only the town library register tells that Johann Sebastian Bach, Musical Director and Singing Master of the St. Thomas School, was carried to his grave July 30, 1750.

But the memory of Bach is enduring, his fame immortal and the love his beautiful music inspires increases from year to year, wherever that music is known, all over the world.

While little Sebastian Bach was laboriously copying out music by pale moonlight, because of his great love for it, another child of the same age was finding the greatest happiness of his life seated before an old spinet, standing in a lumber garret. He was trying to make music from those half dumb keys. No one had taught him how to play; it was innate genius that guided his little hands to find the right harmonies and bring melody out of the old spinet.

The boy's name was George Frederick Handel, and he was born in the German town of Halle, February 23, 1685. Almost from infancy he showed a remarkable fondness for music. His toys must be able to produce musical sounds or he did not care for them. The child did not inherit a love for music from his father, for Dr. Handel, who was a surgeon, looked on music with contempt, as something beneath the notice of a gentleman. He had decided his son was to be a lawyer, and refused to allow him to attend school for fear some one might teach him his notes. The mother was a sweet gentle woman, a second wife, and much younger than her husband, who seemed to have ruled his household with a rod of iron.

When little George was about five, a kind friend, who knew how he longed to make music, had a spinet sent to him unbeknown to his father, and placed in a corner of the old garret. Here the child loved to come when he could escape notice. Often at night, when all were asleep, he would steal away to the garret and work at the spinet, mastering difficulties one by one. The strings of the instrument had been wound with cloth to deaden the sound, and thus made only a tiny tinkle.

After this secret practising had been going on for some time, it was discovered one night, when little George was enjoying his favorite pastime. He had been missed and the whole house went in search. Finally the father, holding high the lantern in his hand and followed by mother and the rest of the inmates, reached the garret, and there found the lost child seated at his beloved spinet, quite lost to the material world. There is no record of any angry outburst on the father's part and it is likely little George was left in peace.

One day when the boy was seven years old, the father was about to start for the castle of the Duke of Saxe-Weissenfels, to see his son, a stepbrother of George, who was a valet de chambre to the Duke. Little George begged to go too, for he knew there was music to be heard at the castle. In spite of his father's refusal he made up his mind to go if he had to run every step of the way. So watching his chance, he started to run after the coach in which his father rode. The child had no idea it was a distance of forty miles. He strove bravely to keep pace with the horses, but the roads were rough and muddy. His strength beginning to fail, he called out to the coachman to stop. His father, hearing the boy's voice looked out of the window. Instead of scolding the little scamp roundly, he was touched by his woebegone appearance, had him lifted into the coach and carried on to Weissenfels.

George enjoyed himself hugely at the castle. The musicians were very kind to him, and his delight could hardly be restrained when he was allowed to try the beautiful organ in the chapel. The organist stood behind him and arranged the stops, and the child put his fingers on the keys that made the big pipes speak. During his stay, George had several chances to play; one was on a Sunday at the close of the service. The organist lifted him upon the bench and bade him play. Instead of the Duke and all his people leaving the chapel, they stayed to listen. When the music ceased the Duke asked: "Who is that child? Does anybody know his name?" The organist was sent for, and then little George was brought. The Duke patted him on the head, praised his playing and said he was sure to become a good musician. The organist then remarked he had heard the father disapproved of his musical studies. The Duke was greatly astonished. He sent for the father and after speaking highly of the boy's talent, said that to place any obstacle in the child's way would be unworthy of the father's honorable profession.

And so it was settled that George Frederick should devote himself to music. Frederick Zachau, organist of the cathedral at Halle, was the teacher chosen to instruct the boy on the organ, harpsichord and violin. He also taught him composition, and showed him how different countries and composers differed in their ideas of musical style. Very soon the boy was composing the regular weekly service for the church, besides playing the organ whenever Zachau happened to be absent. At that time the boy could not have been more than eight years old.

After three years' hard work his teacher told him he must seek another master, as he could teach him nothing more. So the boy was sent to Berlin, to continue his studies. Two of the prominent musicians there were Ariosti and Buononcini; the former received the boy kindly and gave him great encouragement; the other took a dislike to the little fellow, and tried to injure him. Pretending to test his musicianship, Buononcini composed a very difficult piece for the harpsichord and asked him to play it at sight. This the boy did with ease and correctness. The Elector was delighted with the little musician, offered him a place at Court and even promised to send him to Italy to pursue his studies. Both offers were refused and George returned to Halle and to his old master, who was happy to have him back once more.

Not long after this the boy's father passed away, and as there was but little money left for the mother, her son decided at once that he must support himself and not deprive her of her small income. He acted as deputy organist at the Cathedral and Castle of Halle, and a few years later, when the post was vacant, secured it at a salary of less than forty dollars a year and free lodging. George Frederick was now seventeen and longed for a broader field. Knowing that he must leave Halle to find it, he said good-by to his mother, and in January 1703, set out for Hamburg to seek his fortune.

The Opera House Orchestra needed a supplementary violin. It was a very small post, but he took it, pretending not to be able to do anything better. However a chance soon came his way to show what he was capable of. One day the conductor, who always presided at the harpsichord, was absent, and no one was there to take his place. Without delay George came forward and took his vacant seat. He conducted so ably, that he secured the position for himself.

The young musician led a busy life in Hamburg, filled with teaching, study and composition. As his fame increased he secured more pupils, and he was not only able to support himself, but could send some money to his mother. He believed in saving money whenever he could; he knew a man should not only be self supporting, but somewhat independent, in order to produce works of art.

Handel now turned his attention to opera, composing "Almira, Queen of Castile," which was produced in Hamburg early in January 1705. This success encouraged him to write others; indeed he was the author of forty operas, which are only remembered now by an occasional aria. During these several years of hard work he had looked forward to a journey to Italy, for study. He was now a composer of some note and decided it was high time to carry out his cherished desire.

He remained some time in Florence and composed the opera "Rodrigo," which was performed with great success. While in Venice he brought out another opera, "Agrippina," which had even greater success. Rome delighted him especially and he returned for a second time in 1709. Here he composed his first oratorio, the "Resurrection," which was produced there. Handel returned to Germany the following year. The Elector of Hanover was kind to him, and offered him the post of Capellmeister, with a salary of about fifteen hundred dollars. He had long desired to visit England, and the Elector gave him leave of absence. First, however, he went to Halle to see his mother and his old teacher. We can imagine the joy of the meeting, and how proud and happy both were at the success of the young musician. After a little time spent with his dear ones, he set out for England.

Handel came to London, preceded by the fame of his Italian success. Italian opera was the vogue just then in the English capital, but it was so badly produced that a man of Handel's genius was needed to properly set it before the people. He had not been long on English soil when he produced his opera "Rinaldo," at the Queen's Theater; it had taken him just two weeks to compose the opera. It had great success and ran night after night. There are many beautiful airs in "Rinaldo," some of which we hear to-day with the deepest pleasure. "Lascia ch'jo pianga" and "Cara si's sposa" are two of them. The Londoners had welcomed Handel with great cordiality and with his new opera he was firmly established in their regard. With the young musician likewise there seemed to be a sincere affection for England. He returned in due time to his duties in Hanover, but he felt that London was the field for his future activities.

It was not very long after his return to Germany that he sought another leave of absence to visit England, promising to return within a "reasonable time." London received him with open arms and many great people showered favors upon him. Lord Burlington invited him to his residence in Piccadilly, which at that time consisted of green fields. The only return to be made for all this social and home luxury was that he should conduct the Earl's chamber concerts. Handel devoted his abundant leisure to composition, at which he worked with much ardor. His fame was making great strides, and when the Peace of Utrecht was signed and a Thanksgiving service was to be held in St. Paul's, he was commissioned to compose a Te Deum and Jubilate. To show appreciation for his work and in honor of the event, Queen Anne awarded Handel a life pension of a thousand dollars.

The death of the Queen, not long after, brought the Elector of Hanover to England, to succeed her as George I. It was not likely that King George would look with favor on his former Capellmeister, who had so long deserted his post. But an opportunity soon came to placate his Majesty. A royal entertainment, with decorated barges on the Thames was arranged. An orchestra was to furnish the music, and the Lord Chamberlain commissioned Handel to compose music for the fête. He wrote a series of pieces, since known as "Water Music." The king was greatly delighted with the music, had it repeated, and learning that Handel conducted in person, sent for him, forgave all and granted him another pension of a thousand dollars. He was also appointed teacher to the daughters of the Prince of Wales, at a salary of a thousand a year. With the combined sum (three thousand dollars) which he now received, he felt quite independent, indeed a man of means.

Not long after this Handel was appointed Chapel master to the Duke of Chandos, and was expected to live at the princely mansion he inhabited. The size and magnificence of The Cannons was the talk of the country for miles around. Here the composer lived and worked, played the organ in the chapel, composed church music for the service and wrote his first English oratorio, "Esther." This was performed in the Duke's chapel, and the Duke on this occasion handed the composer five thousand dollars. Numerous compositions for the harpsichord belong to this period, among them the air and variations known as "The Harmonious Blacksmith." The story goes that Handel was walking to Cannons through the village of Edgeware, and being overtaken by a heavy shower, sought shelter in the smithy. The blacksmith was singing at his work and his hammer kept time with his song. The composer was struck with the air and its accompaniment, and as soon as he reached home, wrote out the tune with the variations. This story has been disputed, and it is not known whether it is true or not.

When Handel first came to London, he had done much to encourage the production of opera in the Italian style. Later these productions had to be given up for lack of money, and the King's Theater remained closed for a long time. Finally a number of rich men formed a society to revive opera in London. The King subscribed liberally to the venture. Handel was at once engaged as composer and impressario. He started work on a new opera and when that was well along, set out for Germany, going to Dresden to select singers. On his return he stopped at Halle, where his mother was still living, but his old teacher had passed away.

The new opera "Radamisto" was ready early in 1720, and produced at the Royal Academy of Music, as the theater was now called. The success of the production was tremendous. But Handel, by his self-will had stirred up envy and jealousy, and an opposition party was formed, headed by his old enemy from Hamburg, Buononcini, who had come to London to try his fortunes. A test opera was planned, of which Handel wrote the third act, Buononcini the second and a third musician the first. When the new work was performed, the third act was pronounced by the judges much superior to the second. But Buononcini's friends would not accept defeat, and the battle between all parties was violent. Newspapers were full of it, and many verses were written. Handel cared not a whit for all this tempest, but calmly went his way.

In 1723, his opera "Ottone" was to be produced. The great singer Cuzzoni had been engaged, but the capricious lady did not arrive in England till the rehearsals were far advanced, which of course did not please the composer. When she did appear she refused to sing the aria as he had composed it. He flew into a rage, took her by the arm and threatened to throw her out of the window unless she obeyed. The singer was so frightened by his anger that she sang as he directed, and made a great success of the aria.

Handel's industry in composing for the Royal Academy of Music was untiring. For the first eight years from the beginning of the Society's work he had composed and produced fourteen operas. During all this time, his enemies never ceased their efforts to destroy him. The great expense of operatic production, the troubles and quarrels with singers, at last brought the Academy to the end of its resources. At this juncture, the famous "Beggar's Opera," by John Gay, was brought out at a rival theater. It was a collection of most beautiful melodies from various sources, used with words quite unworthy of them. But the fickle public hailed the piece with delight, and its success was the means of bringing total failure to the Royal Academy. Handel, however, in spite of the schemes of his enemies, was determined to carry on the work with his own fortune. He went again to Italy to engage new singers, stopping at Halle to see his mother who was ill. She passed away the next year at the age of eighty.

Handel tried for several years to keep Italian opera going in London, in spite of the lack of musical taste and the opposition of his enemies; but in 1737, he was forced to give up the struggle. He was deeply in debt, his whole fortune of ten thousand pounds had been swept away and his health broken by anxiety. He would not give up; after a brief rest, he returned to London to begin the conflict anew. The effort to re-awaken the English public's interest in Italian opera seemed useless, and the composer at last gave up the struggle. He was now fifty-five, and began to think of turning his attention to more serious work. Handel has been called the father of the oratorio; he composed at least twenty-eight works in this style, the best known being "Samson," "Israel in Egypt," "Jephtha," "Saul," "Judas Maccabæus" and greatest of all, the "Messiah."

The composer conceived the idea of writing the last named work in 1741. Towards the end of this year he was invited to visit Ireland to make known some of his works. On the way there he was detained at Chester for several days by contrary winds. He must have had the score of the "Messiah" with him, for he got together some choir boys to try over a few of the choral parts. "Can you sing at sight?" was put to each boy before he was asked to sing. One broke down at the start. "What de devil you mean!" cried the impetuous composer, snatching the music from him. "Didn't you say you could sing at sight?"

"Yes sir, but not at first sight."

The people of Dublin warmly welcomed Handel, and the new oratorio, the "Messiah," was performed at Music Hall, with choirs of both cathedrals, and with some concertos on the organ played by the composer. The performance took place, April 13, 1742. Four hundred pounds were realized, which were given to charity. The success was so great that a second performance was announced. Ladies were requested to come without crinoline, thereby providing a hundred more seats than at the first event.

The Irish people were so cordial, that the composer remained almost a year among them. For it was not till March 23, 1743, that the "Messiah" was performed in London. The King was one of the great audience who heard it. All were so deeply impressed by the Hallelujah chorus, that with the opening words, "For the Lord God omnipotent reigneth," the whole audience, including the King, sprang to their feet, and remained standing through the entire chorus. From that time to this it has always been the custom to stand during this chorus, whenever it is performed.

Once started on this line of thought, one oratorio after another flowed from his prolific pen, though none of them proved to be as exalted in conception as the "Messiah." The last work of this style was "Jephtha," which contains the beautiful song, "Waft her, angels." While engaged in composing this oratorio, Handel became blind, but this affliction did not seem to lessen his power for work. He was now sixty-eight, and had conquered and lived down most of the hostility that had been so bitter against him. His fortunes also constantly improved, so that when he passed away he left twenty thousand pounds.

The great composer was a big man, both physically and mentally. A friend describes his countenance as full of fire; "when he smiled it was like the sun bursting out of a black cloud. It was a sudden flash of intelligence, wit and good humor, which illumined his countenance, which I have hardly ever seen in any other." He could relish a joke, and had a keen sense of humor. Few things outside his work interested him; but he was fond of the theater, and liked to go to picture sales. His fiery temper often led him to explode at trifles. No talking among the listeners could be borne by him while he was conducting. He did not hesitate to visit violent abuse on the heads of those who ventured to speak while he was directing and not even the presence of royalty could restrain his anger.

Handel was always generous in assisting those who needed aid, and he helped found the Society for Aiding Distressed Musicians. His last appearance in public, was at a performance of the "Messiah," at Covent Garden, on April 6, 1759. His death occurred on the 14th of the same month, at the house in Brook Street where he had lived for many years. Thus, while born in the same year as Sebastian Bach, he outlived him by about a decade. He was buried in Westminster Abbey, and later a fine monument was erected to his memory. The most of his manuscripts came into the possession of King George III, and are preserved in the musical library of Buckingham Palace.

Christoph Willibald Gluck has been called the "regenerator of the opera" for he appeared just at the right moment to rescue opera from the deplorable state into which it had fallen. At that time the composers often yielded to the caprices of the singers and wrote to suit them, while the singers themselves, through vanity and ignorance, made such requirements that opera itself often became ridiculous. Gluck desired "to restrict the art of music to its true object, that of aiding the effect of poetry by giving greater expression to words and scenes, without interrupting the action or the plot." He wrote only operas, and some of his best works keep the stage to-day. They are simple in design yet powerful in appeal: very original and stamped with refinement and true feeling.

The boy Christoph, like many another lad who became a great musician, had a sorrowful childhood, full of poverty and neglect. His home was in the little town of Weissenwangen, on the borders of Bohemia, where he was born July 2, 1714. As a little lad he early manifested a love for music, but his parents were in very straitened circumstances and could not afford to pay for musical instruction. He was sent to one of the public schools. Fortunately the art of reading music from notes, formation of scales and fundamentals, was taught along with general school subjects.

While his father lived the boy was sure of sympathy and affection, though circumstances were of the poorest. But the good man passed away when the boy was quite young, and then matters were much worse. He was gradually neglected until he was at last left to shift for himself.

He possessed not only talent but perseverance and the will to succeed. The violoncello attracted him, and he began to teach himself to play it, with no other help than an old instruction book. Determination conquered many difficulties however, and before long he had made sufficient progress to enable him to join a troop of traveling minstrels. From Prague they made their way to Vienna.

Arrived in Vienna, that rich, gay, laughter-loving city, where the people loved music and often did much for it, the youth's musical talent together with his forlorn appearance and condition won sympathy from a few generous souls, who not only provided a home and took care of his material needs, but gave him also the means to continue his musical studies. Christoph was overcome with gratitude and made the best possible use of his opportunities. For nearly two years he gave himself up to his musical studies.

Italy was the goal of his ambition, and at last the opportunity to visit that land of song was within his grasp. At the age of twenty-four, in the year 1738, Gluck bade adieu to his many kind friends in Vienna, and set out to complete his studies in Italy. Milan was his objective point. Soon after arriving there he had the good fortune to meet Padre Martini, the celebrated master of musical theory. Young Gluck at once placed himself under the great man's guidance and labored diligently with him for about four years. How much he owed to the careful training Martini was able to give, was seen in even his first attempts at operatic composition.

At the conclusion of this long period of devoted study, Gluck began to write an opera, entitled "Artaxerxes." When completed it was accepted at the Milan Theater, brought out in 1741 and met with much success. This success induced one of the managers in Venice to offer him an engagement for that city if he would compose a new opera. Gluck then produced "Clytemnestra." This second work had a remarkable success, and the managers arranged for the composition of another opera, which was "Demetrio," which, like the others was most favorably received. Gluck now had offers from Turin, so that the next two years were spent between that city and Milan, for which cities he wrote five or six operas. By this time the name of Gluck had become famous all over Italy; indeed his fame had spread to other countries, with the result that tempting offers for new operas flowed in to him from all directions. Especially was a London manager, a certain Lord Middlesex, anxious to entice the young composer from Italy to come over to London, and produce some of his works at the King's Theater in the Haymarket.

The noble manager made a good offer too, and Gluck felt he ought to accept. He reached London in 1745, but owing to the rebellion which had broken out in Scotland all the theaters were closed, and the city in more or less confusion. However a chance to hear the famous German composer, who had traveled such a distance, was not to be lost, and Lord Middlesex besought the Powers to re-open the theater. After much pleading his request was finally granted. The opening opera, written on purpose to introduce Gluck to English audiences, was entitled "La Caduta del Giganti,"—"Fall of the Giants"—and did not seem to please the public. But the young composer was undaunted. His next opera, "Artamene," pleased them no better. The mind of the people was taken up at that period with politics and political events, and they cared less than usual for music and the arts. Then, too, Handel, at the height of his fame, was living in London, honored and courted by the aristocracy and the world of fashion.

Though disappointed at his lack of success, Gluck remained in England several years, constantly composing operas, none of which seemed to win success. At last he took his way quietly back to Vienna. In 1754, he was invited to Rome, where he produced several operas, among them "Antigone"; they were all successful, showing the Italians appreciated his work. He now proceeded to Florence, and while there became acquainted with an Italian poet, Ranieri di Calzabigi. They were mutually attracted to each other, and on parting had sworn to use their influence and talents to reform Italian opera.

Gluck returned to Vienna, and continued to compose operas. In 1764, "Orfeo" was produced,—an example of the new reform in opera! "Orfeo" was received most favorably and sung twenty-eight times, a long run for those days. The singing and acting of Guadagni made the opera quite the rage, and the work began to be known in England. Even in Paris and Parma it became a great favorite. The composer was now fifty, and his greatest works had yet—with the exception or "Orfeo"—to be written. He began to develop that purity of style which we find in "Alceste," "Iphigénie en Tauride" and others. "Alceste" was the second opera on the reformed plan which simplified the music to give more prominence to the poetry. It was produced in Vienna in 1769, with the text written by Calzabigi. The opera was ahead of "Orfeo" in simplicity and nobility, but it did not seem to please the critics. The composer himself wrote: "Pedants and critics, an infinite multitude, form the greatest obstacle to the progress of art. They think themselves entitled to pass a verdict on 'Alceste' from some informal rehearsals, badly conducted and executed. Some fastidious ear found a vocal passage too harsh, or another too impassioned, forgetting that forcible expression and striking contrasts are absolutely necessary. It was likewise decided in full conclave, that this style of music was barbarous and extravagant."

In spite of the judgment of the critics, "Alceste" increased the fame of Gluck to a great degree. Paris wanted to see the man who had revolutionized Italian opera. The French Royale Académie had made him an offer to visit the capital, for which he was to write a new opera for a début. A French poet, Du Rollet, living in Vienna, offered to write a libretto for the new opera, and assured him there was every chance for success in a visit to France. The libretto was thereupon written, or rather arranged from Racine's "Iphigénie en Aulide," and with this, Chevalier Gluck, lately made Knight of the papal order of the Golden Spur, set out for Paris.

And now began a long season of hard work. The opera "Iphigénie" took about a year to compose, besides a careful study of the French language. He had even more trouble with the slovenly, ignorant orchestra, than he had with the French language. The orchestra declared itself against foreign music; but this opposition was softened down by his former pupil and patroness, the charming Marie Antoinette, Queen of France.

After many trials and delays, "Iphigénie" was produced August 19, 1774. The opera proved an enormous success. The beautiful Queen herself gave the signal for applause in which the whole house joined. The charming Sophie Arnould sang the part of Iphigénie and seemed to quite satisfy the composer. Larrivée was the Agamemnon, and other parts were well sung. The French were thoroughly delighted. They fêted and praised Gluck, declaring he had discovered the music of the ancient Greeks, that he was the only man in Europe who could express real feelings in music. Marie Antoinette wrote to her sister: "We had, on the nineteenth, the first performance of Gluck's 'Iphigénie,' and it was a glorious triumph. I was quite enchanted, and nothing else is talked of. All the world wishes to see the piece, and Gluck seems well satisfied."

The next year, 1775, Gluck brought out an adaptation suitable for the French stage, of his "Alceste," which again aroused the greatest enthusiasm. The theater was crammed at every performance. Marie Antoinette's favorite composer was again praised to the skies, and was declared to be the greatest composer living.

But Gluck had one powerful opponent at the French Court, who was none other than the famous Madame du Barry, the favorite of Louis XV. Since the Queen had her pet musical composer, Mme. du Barry wished to have hers. An Italian by birth, she could gather about her a powerful Italian faction, who were bent upon opposition to the Austrian Gluck. She had listened to his praises long enough, and the tremendous success of "Alceste" had been the last straw and brought things to a climax. Du Barry would have some one to represent Italian music, and applied to the Italian ambassador to desire Piccini to come to Paris.

On the arrival of Piccini, Madame du Barry began activities, aided by Louis XV himself. She gathered a powerful Italian party about her, and their first act was to induce the Grand Opera management to make Piccini an offer for a new opera, although they had already made the same offer to Gluck. This breach of good faith led to a furious war, in which all Paris joined; it was fierce and bitter while it lasted. Even politics were forgotten for the time being. Part of the press took up one side and part the other. Many pamphlets, poems and satires appeared, in which both composers were unmercifully attacked. Gluck was at the time in Germany, and Piccini had come to Paris principally to secure the tempting fee offered him. The leaders of the feud kept things well stirred up, so that a stranger could not enter a café, hotel or theater without first answering the question whether he stood for Gluck or Piccini. Many foolish lies were told of Gluck in his absence. It was declared by the Piccinists that he went away on purpose, to escape the war; that he could no longer write melodies because he was a dried up old man and had nothing new to give France. These lies and false stories were put to flight one evening when the Abbé Arnaud, one of Gluck's most ardent adherents, declared in an aristocratic company, that the Chevalier was returning to France with an "Orlando" and an "Armide" in his portfolio.

"Piccini is also working on an 'Orlando,'" spoke up a follower of that redoubtable Italian.

"That will be all the better," returned the abbé, "for we shall then have an 'Orlando' and also an 'Orlandino.'"

When Gluck arrived in Paris, he brought with him the finished opera of "Armide," which was produced at the Paris Grand Opera on September 23, 1777. At first it was merely a succès d'estime, but soon became immensely popular. On the first night many of the critics were against the opera, which was called too noisy. The composer, however, felt he had done some of his best work in "Armide"; that the music was written in such style that it would not grow old, at least not for a long time. He had taken the greatest pains in composing it, and declared that if it were not properly rehearsed at the Opera he would not let them have it at all, but would retain the work himself for his own pleasure. He wrote to a friend: "I have put forth what little strength is left in me, into 'Armide'; I confess I should like to finish my career with it."

It is said the Gluck composed "Armide" in order to praise the beauty of Marie Antoinette, and she for her part showed the deepest interest in the success of the piece, and really "became quite a slave to it." Gluck often told her he "rearranged his music according to the impression it made upon the Queen."

"Great as was the success of 'Armide,'" wrote the Princess de Lamballe, "no one prized this beautiful work more highly than the composer of it. He was passionately enamored of it; he told the Queen the air of France had rejuvenated his creative powers, and the sight of her majesty had given such a wonderful impetus to the flow of ideas, that his composition had become like herself, angelic, sublime."

The growing success of "Armide" only added fuel to the flame of controversy which had been stirred up. To cap the climax, Piccini had finished his opera, which was duly brought out and met with a brilliant reception. Indeed its success was greater than that won by "Armide," much to the delight of the Piccinists. Of course the natural outcome was that the other party should do something to surpass the work of their rivals. Marie Antoinette was besought to prevail on Gluck to write another opera.

A new director was now in charge of the Opera House. He conceived the bright idea of setting the two composers at work on the same subject, which was to be "Iphigénie en Tauride." This plan made great commotion in the ranks of the rival factions, as each wished to have their composer's work performed first. The director promised that Piccini's opera should be first placed in rehearsal. Gluck soon finished his and handed it in, but the Italian, trusting to the director's word of honor, was not troubled when he heard the news, though he determined to complete his as soon as possible. A few days later, when he went to the Opera House with his completed score, he was horrified to find the work of his rival already in rehearsal. There was a lively scene, but the manager said he had received orders to produce the work of Gluck at once, and he must obey. On the 18th of May, 1779, the Gluck opera was first performed. It produced the greatest excitement and had a marvelous success. Even Piccini succumbed to the spell, for the music made such an impression on him that he did not wish his own work to be brought out.

The director, however, insisted, and soon after the second Iphigénie appeared. The first night the opera did not greatly please; the next night proved a comic tragedy, as the prima donna was intoxicated. After a couple of days' imprisonment she returned and sang well. But the war between the two factions continued till the death of Gluck, and the retirement of Piccini.

The following year, in September, Gluck finished a new opera, "Echo et Narcisse," and with this work decided to close his career, feeling he was too old to write longer for the lyric stage. He was then nearly seventy years old, and retired to Vienna, to rest and enjoy the fruits of all his years of incessant toil. He was now rich, as he had earned nearly thirty thousand pounds. Kings and princes came to do him honor, and to tell him what pleasure his music had always given them.

Gluck passed away on November 15, 1787, honored and beloved by all. The simple beauty and purity of his music are as moving and expressive to-day as when it was written, and the "Michael of Music" speaks to us still in his operas, whenever they are adequately performed.

In Josef Haydn we have one of the classic composers, a sweet, gentle spirit, who suffered many privations in early life, and through his own industrious efforts rose to positions of respect and honor, the result of unremitting toil and devotion to a noble ideal. Like many of the other great musicians, through hardship and sorrow he won his place among the elect.

Fifteen leagues south of Vienna, amid marshy flats along the river Leitha, lies the small village of Rehrau. At the end of the straggling street which constitutes the village, stood a low thatched cottage and next to it a wheelwright's shop, with a small patch of greensward before it. The master wheelwright, Mathias Haydn, was sexton, too, of the little church on the hill. He was a worthy man and very religious. A deep love for music was part of the man's nature, and it was shared to a large extent by his wife Maria. Every Sunday evening he would bring out his harp, on which he had taught himself to play, and he and his wife would sing songs and hymns, accompanied by the harp. The children, too, would add their voices to the concert. The little boy Josef, sat near his father and watched his playing with rapt attention. Sometimes he would take two sticks and make believe play the violin, just as he had seen the village schoolmaster do. And when he sang hymns with the others, his voice was sweet and true. The father watched the child with interest, and a new hope rose within him. His own life had been a bitter disappointment, for he had been unable to satisfy his longing for a knowledge of the art he loved. Perhaps Josef might one day become a musician—indeed he might even rise to be Capellmeister.

Little Josef was born March 31, 1732. The mother had a secret desire that the boy should join the priesthood, but the father, as we have seen, hoped he would make a musical career, and determined, though poor in this world's goods, to aid him in every possible way.

About this time a distant relative, one Johann Mathias Frankh by name, arrived at the Haydn cottage on a visit. He was a schoolmaster at Hainburg, a little town four leagues away. During the regular evening concert he took particular notice of Josef and his toy violin. The child's sweet voice indicated that he had the makings of a good musician. At last he said: "If you will let me take Sepperl, I will see he is properly taught; I can see he promises well."

The parents were quite willing and as for little Sepperl, he was simply overjoyed, for he longed to learn more about the beautiful music which filled his soul. He went with his new cousin, as he called Frankh, without any hesitation, and with the expectation that his childish day dreams were to be realized.

A new world indeed opened to the six year old boy, but it was not all beautiful. Frankh was a careful and strict teacher; Josef not only was taught to sing well, but learned much about various instruments. He had school lessons also. But his life in other ways was hard and cheerless. The wife of his cousin treated him with the utmost indifference, never looking after his clothing or his well being in any way. After a time his destitute and neglected appearance was a source of misery to the refined, sensitive boy, but he tried to realize that present conditions could not last forever, and he bravely endeavored to make the best of them. Meanwhile the training of his voice was well advanced and when not in school he could nearly always be found in church, listening to the organ and the singing. Not long after, he was admitted to the choir, where his sweet young voice joined in the church anthems. Always before his mind was a great city where he knew he would find the most beautiful music—the music of his dreams. That city was Vienna, but it lay far away. Josef looked down at his ragged clothing and wondered if he would ever see that magical city.

One morning his cousin told him there would be a procession through the town in honor of a prominent citizen who had just passed away. A drummer was needed and the cousin had proposed Josef. He showed the boy how to make the strokes for a march, with the result that Josef walked in the procession and felt quite proud of this exhibition of his skill. The very drum he used that day is preserved in the little church at Hamburg.

A great event occurred in Josef's prospects at the end of his second year of school life at Hamburg. The Capellmeister, Reutter by name, of St. Stephen's cathedral in Vienna, came to see his friend, the pastor of Hamburg. He happened to say he was looking for a few good voices for the choir. "I can find you one at least," said the pastor; "he is a scholar of Frankh, the schoolmaster, and has a sweet voice."

Josef was sent for and the schoolmaster soon returned leading him by the hand.

"Well my little fellow," said the Capellmeister, drawing him to his knee, "can you make a shake?"

"No sir, but neither can my cousin Frankh."

Reutter laughed at this frankness, and then proceeded to show him how the shake was done. Josef after a few trials was able to perform the shake to the entire satisfaction of his teacher. After testing him on a portion of a mass the Capellmeister was willing to take him to the Cantorei or Choir school of St. Stephen's in Vienna. The boy's heart gave a great leap. Vienna, the city of his dreams. And he was really going there! He could scarcely believe in his good fortune. If he could have known all that was to befall him there, he might not have been so eager to go. But he was only a little eight-year-old boy, and childhood's dreams are rosy.

Once arrived at the Cantorei, Josef plunged into his studies with great fervor, and his progress was most rapid. He was now possessed with a desire to compose, but had not the slightest idea how to go about such a feat. However, he hoarded every scrap of music paper he could find and covered it with notes. Reutter gave no encouragement to such proceedings. One day he asked what the boy was about, and when he heard the lad was composing a "Salve Regina," for twelve voices, he remarked it would be better to write it for two voices before attempting it in twelve. "And if you must try your hand at composition," added Reutter more kindly, "write variations on the motets and vespers which are played in church."

As neither the Capellmeister nor any of the teachers offered to show Josef the principles of composition, he was thrown upon his own resources. With much self denial he scraped together enough money to buy two books which he had seen at the second hand bookseller's and which he had longed to possess. One was Fox's "Gradus ad Parnassum," a treatise on composition and counterpoint; the other Matheson's "The Complete Capellmeister." Happy in the possession of these books, Josef used every moment outside of school and choir practise to study them. He loved fun and games as well as any boy, but music always came first. The desire to perfect himself was so strong that he often added several hours each day to those already required, working sixteen or eighteen hours out of the twenty-four.

And thus a number of years slipped away amid these happy surroundings. Little Josef was now a likely lad of about fifteen years. It was arranged that his younger brother Michael was to come to the Cantorei. Josef looked eagerly forward to this event, planning how he would help the little one over the beginning and show him the pleasant things that would happen to him in the new life. But the elder brother could not foresee the sorrow and privation in store for him. From the moment Michael's pure young voice filled the vast spaces of the cathedral, it was plain that Josef's singing could not compete with it. His soprano showed signs of breaking, and gradually the principal solo parts, which had always fallen to him, were given to the new chorister. On a special church day, when there was more elaborate music, the "Salve Regina," which had always been given to Josef, was sung so beautifully by the little brother, that the Emperor and Empress were delighted, and they presented the young singer with twenty ducats.

Poor Josef! He realized that his place was virtually taken by the brother he had welcomed so joyously only a short time before. No one was to blame of course; it was one of those things that could not be avoided. But what actually caused him to leave St. Stephen's was a boyish prank played on one of the choir boys, who sat in front of him. Taking up a new pair of shears lying near, he snipped off, in a mischievous moment, the boy's pigtail. For this jest he was punished and then dismissed from the school. He could hardly realize it, in his first dazed, angry condition. Not to enjoy the busy life any more, not to see Michael and the others and have a comfortable home and sing in the Cathedral. How he lived after that he hardly knew. But several miserable days went by. One rainy night a young man whom he had known before, came upon him near the Cathedral, and was struck by his white, pinched face. He asked where the boy was living. "Nowhere—I am starving," was the reply. Honest Franz Spangler was touched at once.

"We can't stand here in the rain," he said. "You know I haven't a palace to offer, but you are welcome to share my poor place for one night anyway. Then we shall see."

It was indeed a poor garret where the Spanglers lived, but the cheerful fire and warm bread and milk were luxuries to the starving lad. Best of all was it to curl up on the floor, beside the dying embers and fall into refreshing slumber. The next morning the world looked brighter. He had made up his mind not to try and see his brother; he would support himself by music. He did not know just how he was going to do this, but determined to fight for it and never give in.

Spangler, deeply touched by the boy's forlorn case, offered to let him occupy a corner of his garret until he could find work, and Josef gratefully accepted. The boy hoped he could quickly find something to do; but many weary months were spent in looking for employment and in seeking to secure pupils, before there was the slightest sign of success. Thinly clad as he was and with the vigorous appetite of seventeen, which was scarcely ever appeased, he struggled on, hopeful that spring would bring some sort of good cheer.

But spring came, yet no employment was in sight. His sole earnings had been the coppers thrown to him as he stood singing in the snow covered streets, during the long cold winter. Now it was spring, and hope rose within him. He had been taught to have simple faith in God, and felt sure that in some way his needs would be met.

At last the tide turned slightly. A few pupils attracted by the small fee he charged, took lessons on the clavier; he got a few engagements to play violin at balls and parties, while some budding composers got him to revise their manuscripts for a small fee. All these cheering signs of better times made Josef hopeful and grateful. One day a special piece of good fortune came his way. A man who loved music, at whose house he had sometimes played, sent him a hundred and fifty florins, to be repaid without interest whenever convenient.

This sum seemed to Haydn a real fortune. He was able to leave the Spanglers and take up a garret of his own. There was no stove in it and winter was coming on; it was only partly light, even at midday, but the youth was happy. For he had acquired a little worm-eaten spinet, and he had added to his treasures the first six sonatas of Emmanuel Bach.

On the third floor of the house which contained the garret, lived a celebrated Italian poet, Metastasio. Haydn and the poet struck up an acquaintance, which resulted in the musician's introduction to the poet's favorite pupil, Marianne Martinez. Also through Metastasio, Haydn met Nicolo Porpora, an eminent teacher of singing and composition. About this time another avenue opened to him. It was a fashion in Vienna to pick up a few florins by serenading prominent persons. A manager of one of the principal theaters in Vienna, Felix Kurz, had recently married a beautiful woman, whose loveliness was much talked of. It occurred to Haydn to take a couple of companions along and serenade the lady, playing some of his own music. Soon after they had begun to play the house door opened and Kurz himself stood there in dressing gown and slippers. "Whose music was that you were playing?" he asked. "My own," was the answer. "Indeed; then just step inside." The three entered, wondering. They were presented to Madame, then were given refreshments. "Come and see me to-morrow," said Kurz when the boys left; "I think I have some work for you."

Haydn called next day and learned the manager had written a libretto of a comic opera which he called "The Devil on two Sticks," and was looking for some one to compose the music. In one place there was to be a tempest at sea, and Haydn was asked how he would represent that. As he had never seen the sea, he was at a loss how to express it. The manager said he himself had never seen the ocean, but to his mind it was like this, and he began to toss his arms wildly about. Haydn tried every way he could think of to represent the ocean, but Kurz was not satisfied. At last he flung his hands down with a crash on each end of the keyboard and brought them together in the middle. "That's it, that's it," cried the manager and embraced the youth excitedly. All went well with the rest of the opera. It was finished and produced, but did not make much stir, a fact which was not displeasing to the composer, as he was not proud of his first attempt.

His acquaintance with Porpora promised better things. The singing master had noticed his skill in playing the harpsichord, and offered to engage him as accompanist. Haydn gladly accepted at once, hoping to pick up much musical knowledge in this way. Old Porpora was very harsh and domineering at first, treating him more like a valet than a musician. But at last he was won over by Haydn's gentleness and patience, until he was willing to answer all his questions and to correct his compositions. Best of all he brought Haydn to the attention of the nobleman in whose house he was teaching, so that when the nobleman and his family went to the baths of Mannersdorf for several months, Haydn was asked to go along as accompanist to Porpora.