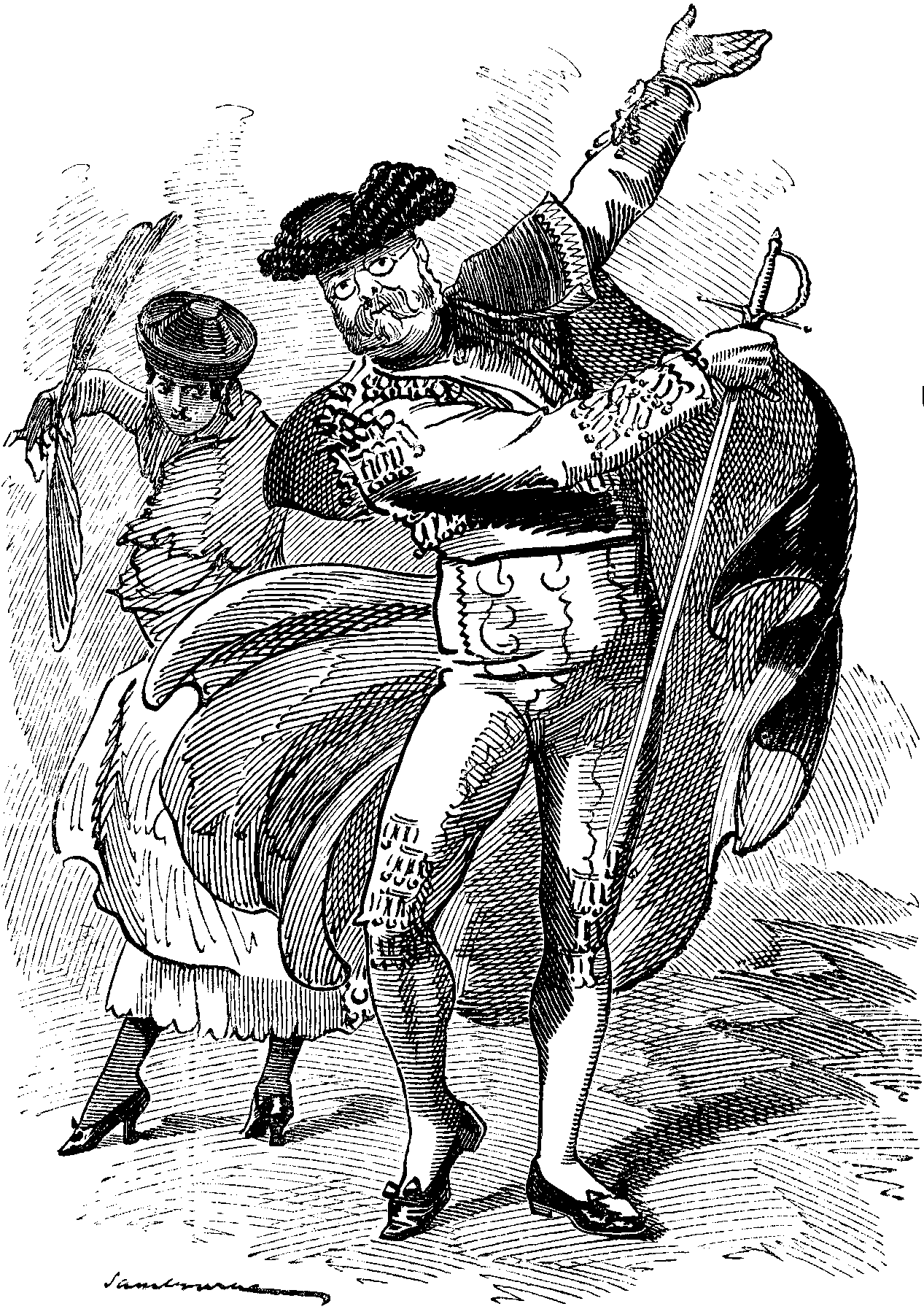

"I have worn a cloak and a Tyrolese hat, and

attitudinised in the Picture-galleries."

"I have worn a cloak and a Tyrolese hat, and

attitudinised in the Picture-galleries."

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Punch, Or The London Charivari, Volume 102, January 30, 1892, by Various This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net Title: Punch, Or The London Charivari, Volume 102, January 30, 1892 Author: Various Release Date: December 6, 2004 [EBook #14272] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK PUNCH *** Produced by Malcolm Farmer, William Flis, and the PG Online Distributed Proofreading Team

Why I am not a success in literature it is difficult for me to tell; indeed, I would give a good deal to anyone who would explain the reason. The Publishers, and Editors, and Literary Men decline to tell me why they do not want my contributions. I am sure I have done all that I can to succeed. When my Novel, Geoffrey's Cousin, comes back from the Row, I do not lose heart—I pack it up, and send it off again to the Square, and so, I may say, it goes the round. The very manuscript attests the trouble I have taken. Parts of it are written in my own hand, more in that of my housemaid, to whom I have dictated passages; a good deal is in the hand of my wife. There are sentences which I have written a dozen times, on the margins, with lines leading up to them in red ink. The story is written on paper of all sorts and sizes, and bits of paper are pasted on, here and there, containing revised versions of incidents and dialogue. The whole packet is now far from clean, and has a business-like and travelled air about it, which should command respect. I always accompany it with a polite letter, expressing my willingness to cut it down, or expand it, or change the conclusion. Nobody can say that I am proud. But it always comes back from the Publishers and Editors, without any explanation as to why it will not do. This is what I resent as particularly hard. The Publishers decline to tell me what their Readers have really said about it. I have forwarded Geoffrey's Cousin to at least five or six notorious authors, with a letter, which runs thus:—

"DEAR SIR,—You will be surprised at receiving a letter from a total stranger, but your well-known goodness of heart must plead my excuse. I am aware that your time is much occupied, but I am certain that you will spare enough of that valuable commodity to glance through the accompanying MS. Novel, and give me your frank opinion of it. Does it stand in need of any alterations, and, if so, what? Would you mind having it published under your own name, receiving one-third of the profits? A speedy answer will greatly oblige."

Would you believe it, Mr. Punch, not one of these over-rated and overpaid men has ever given me any advice at all? Most of them simply send back my parcel with no reply. One, however, wrote to say that he received at least six such packets every week, and that his engagements made it impossible for him to act as a guide, counsellor, and friend to the amateurs of all England. He added that, if I published the Novel at my own expense, the remarks of the public critics would doubtless prove most valuable and salutary.

This decided me; I did publish, at my own expense, with Messrs. SAUL, SAMUEL, MOSS & CO. I had to pay down £150, then £35 for advertisements, then £70 for Publisher's Commission. Other expenses fell grievously on me, as I sent round printed postcards to everyone whose name is in the Red Book, asking them to ask for Geoffrey's Cousin at the Libraries. I also despatched six copies, with six anonymous letters, to Mr. GLADSTONE, signing them, "A Literary Constituent," "A Wavering Anabaptist," and so forth, but, extraordinary to relate, I have received no answer, and no notice has been taken of my disinterested presents. The reviews were of the most meagre and scornful description. Messrs. SAUL, SAMUEL, Moss & Co. have just written to me, begging me to remove the "remainder" of my book, and charging £23 15s. 6d. for warehouse expenses. Yet, when I read Geoffrey's Cousin, I fail to see that it falls, in any way, beneath the general run of novels. I enclose a marked copy, and solicit your earnest attention for the passage in which Geoffrey's Cousin blights his hopes for ever. The story, Sir, is one of controversy, and is suited to this time. Geoffrey McPhun is an Auld Licht (see Mr. BARRIE's books, passim). His cousin is an Esoteric Buddhist. They love each other dearly, but Geoffrey, a rigid character, cannot marry any lady who does not burn, as an Auld Licht, "with a hard gem-like flame." Violet Blair, his cousin, is just as staunch an Esoteric Buddhist. Nothing stands between them but the differences of their creed.

"How can I contemplate, GEOFFREY," said VIOLET, with a rich blush, "the possibility of seeing our little ones stray from the fold of the Lama of Thibet into a chapel of the Original Secession Church?"

They determine to try to convert each other. Geoffrey lends Violet all his theological library, including WODROW's Analecta. She lends him the learned works of Mr. SINNETT and Madame BLAVATSKY. They retire, he to the Himalayas, she to Thrums, and their letters compose Volume II. (Local colour à la KIPLING and BARRIE.) On the slopes of the Himalayas you see Geoffrey converted; he becomes a Cheela, and returns by overland route. He rushes to Ramsgate, and announces his complete acceptance of the truth as it is in Mahatmaism. Alas! alas! Violet has been over-persuaded by the seductions of Presbyterianism, she has hurried down from Thrums, rejoicing, a full-blown Auld Licht. And, in her Geoffrey, she finds a convinced Esoteric Buddhist! They are no better off than they were, their union is impossible, and Vol. III. ends in their poignant anguish.

Now, Mr. Punch, is not this the very novel for the times; rich in adventure (in Kafiristan), teeming with philosophical suggestiveness, and sparkling with all the epigrams of my commonplace book. Yet I am about £300 out of pocket, and, moreover, a blighted being.

I have taken every kind of pains; I have asked London Correspondents to dinner; I have written flattering letters to everybody; I have attempted to get up a deputation of Beloochis to myself; I have tried to make people interview me; I have puffed myself in all the modes which study and research can suggest. If anybody has, I have been "up to date." But Fortune is my foe, and I see others flourish by the very arts which fail in my hands.

I mention my Novel because its failure really is a mystery. But I am not at all more fortunate in the reception of my poetry. I have tried it every way—ballades by the bale, sonnets by the dozen, loyal odes, seditious songs, drawing-room poetry, an Epic on the history of Labducuo, erotic verse, all fire, foam, and fangs, reflective ditto, humble natural ballads about signal-men and newspaper-boys, Life-boat rescues, Idyls, Nocturnes in rhyme, tragedies in blank verse. Nobody will print them, or, if anybody prints them, he regrets that he cannot pay for them. My moral and discursive essays are rejected, my descriptions of nature do not even get into the newspapers. I have not been elected by the Sydenham Club (a clique of humbugs); I have let my hair grow long; I have worn a cloak and a Tyrolese hat, and attitudinised in the picture-galleries, but nobody asked who I am. I have endeavoured to hang on to well-known poets and novelists—they have not welcomed my advances.

My last dodge was a Satire, the Logrolliad, in which I lashed the charlatans and pretenders of the day.

While hoary statesmen scribble in reviews

And guide the doubtful verdict of the Blues,

While HAGGARD scrawls, with blood in lieu of ink,

While MALLOCK teaches Marquises to think,

so long I have rhythmically expressed my design to wield the dripping scourge of satire. But nobody seems a penny the worse, and I am not a paragraph the better. Short stories of a startling description fill my drawers, nobody will venture on one of them. I have closely imitated every writer who succeeds, but my little barque may attendant sail, it pursues the triumph, but does not partake the gale.

I am now engaged on a Libretto for an heroic opera.

What offers?

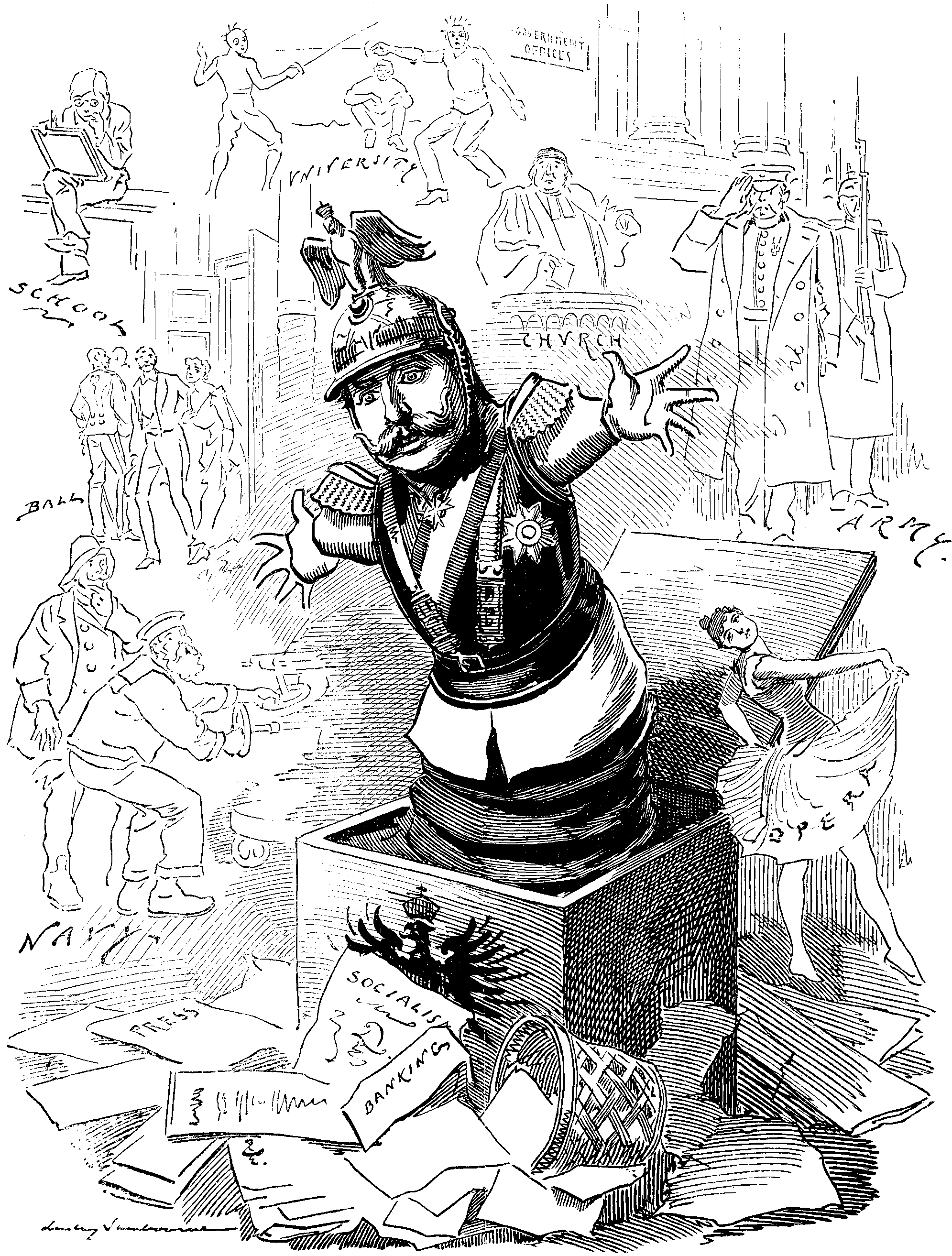

I am the very pattern of a Modern German Emperor,

Omniscient and omnipotent, I ne'er give way to temper, or

If now and then I run a-muck in a Malay-like fashion,

As there's method in my madness, so there's purpose in my passion.

'Tis my aim to manage everything in order categorical—

My fame as Cosmos-maker I intend shall be historical.

I know they call me Paul Pry, say I'm fussy and pragmatical—

But that's because sheer moonshine always hates the mathematical.

I'm not content to "play the King" with an imperial pose in it—

Whatever is marked "Private" I shall up and poke my nose in it.

He won't let drowsing dogs lie, he'll stir up the tabby sleeping Tom—

In fact, he is the model of a modern German Peeping Tom!

I bounce into the Ball-Room when they think I'm fast asleep at home,

And measure steps and skirts and things and mark what state folks keep at home;

Watch the toilette of young Beauty on the very strictest Q.T. too,

Evangelise the Army and keep sentries to their duty, too,

On the Navy, and the Clergy, and the Schools, my wise eyes shoot lights, Sir.

I'm awfully particular to regulate the footlights, Sir.

I preach sermons to my soldiers and arrange their "duds" and duels, too,

And tallow their poor noses, when they've colds, and mix their gruels, too;

I'll make everybody moral, and obedient, and frugal, Sir—

In fact I'm an Imperial edition of MCDOUGALL, Sir!

He'd compel us to drink water and restrain us when to wed agog;

In fact he is the model of a Modern German pedagogue.

I've all the god-like attributes, omniscient, ubiquitous,

I mean to squelch free impulse, which is commonly iniquitous.

But what's the good of being Chief Inspector of the Universe,

And prying into everything from pompous Law to puny verse,

If everything or nearly so, shows a confounded tendency

To go right of its own accord? My Masterful Resplendency

Would radiate aurorally, a world would gaze on trustingly

If only things in general wouldn't go on so disgustingly.

Where is the pull of being Earth's Inspector autocratical,

When the Progress I'd be motor of seems mainly automatical?

Hooray! My would-be Jupiter, a parvenu is told again

He's not the true Olympian, Jack-in-the-Box is "Sold Again!!!"

"ARTIFICIAL OYSTER-CULTIVATION," read Mrs. R., as the heading of a par in the Times. "Good gracious!" she exclaimed, "who on earth would ever think of eating 'artificial oysters!'"

NOTHING is certain in this life except Death, Quarter Day and stoppage for ten minutes at Swindon Station.

Young Wife. "WHERE ARE YOU GOING, REGGIE DEAR?"

Reggie Dear. "ONLY TO THE CLUB, MY DARLING."

Young Wife. "OH, I DON'T MIND THAT, BECAUSE THERE'S A TELEPHONE THERE, AND I CAN TALK TO YOU THROUGH IT, CAN'T I?"

Reggie. "Y-YES—BUT—ER—YOU KNOW, THE CONFOUNDED WIRES ARE ALWAYS GETTING OUT OF ORDER!"

SCENE—The Chamber during a Debate of an exciting character. Member with a newspaper occupying the Tribune.

Member. I ask if the report in this paper is true? It calls the Minister a scoundrel! [Frantic applause.

President. I must interpose. It is not right that such a document should be read.

Member. But it is true. I hold in my hand this truth-telling sheet. (Shouts of "Well done!") This admirable journal describes the Minister as a trickster, a man without a heart! [Yells of approbation.

President. I warn the Member that he is going too far. He is outraging the public conscience. ["Hear! hear!"

Member. It is you that outrage the public conscience. [Sensation.

President. This is too much! If I hear another word of insult, I will assume my hat.

[Profound and long-continued agitation.

Member. A hat is better than a turned coat! (Thunders of applause.) I say that this paper is full of wholesome things, and that when it denounces the Minister as a good-for-nothing, as a slanderer, as a thief—it does but its duty.

[Descends from the Tribune amidst tumultuous applause, and is met by the Minister. Grand altercation, with results.

Minister's Friends. What have you done to him?

Minister (with dignity). I have avenged my honour—I have hit him in the eye!

[Scene closes in upon the Minister receiving hearty congratulations from all sides of the Chamber.

A Pessimistic Matron (the usual beady and bugle-y female, who takes all her pleasure as a penance). Well, they may call it "Venice," but I don't see no difference from what it was when the Barnum Show was 'ere—except—(regretfully)—that then they 'ad the Freaks o' Nature, and Jumbo's skelinton!

Her Husband (an Optimist—less from conviction than contradiction). There you go, MARIA, finding fault the minute you've put your nose inside! We ain't in Venice yet. It's up at the top o' them steps.

The P.M. Up all them stairs? Well, I 'ope it'll be worth seeing when we do get there, that's all!

An Attendant (as she arrives at the top). Not this door, Ma'am—next entrance for Modern Venice.

The Opt. Husb. You needn't go all the way down again, when the steps join like that!

The P.M. I'm not going to walk sideways—I'm not a crab, JOE, whatever you may think. (JOE assents, with reservations). Now wherever have those other two got to? 'urrying off that way! Oh, there they are. 'Ere, LIZZIE and JEM, keep along o' me and Father, do, or we shan't see half of what's to be seen!

Lizzie. Oh, all right, Ma; don't you worry so! (To JEM, her fiancé.) Don't those tall fellows look smart with the red feathers in their cocked 'ats? What do they call them?

Jem (a young man, who thinks for himself). Well, I shouldn't wonder if those were the parties they call "Doges"—sort o' police over there, d'ye see?

Lizzie. They're 'andsomer than 'elmets, I will say that for them. (They enter Modern Venice, amidst cries of "This way for Gondoala Tickets! Pass along, please! Keep to your right!" &c., &c.) It does have a foreign look, with all those queer names written up. Think it's like what it is, JEM?

Jem. Bound to be, with all the money they've spent on it. I daresay they've idle-ised it a bit, though.

The P.M. Where are all these kinals they talk so much about? I don't see none!

Jem (as a break in the crowd reveals a narrow olive-green channel). Why, what d'ye call that, Ma?

The P.M. That a kinal! Why, you don't mean to tell me any barge 'ud—

The Opt. Husb. Go on!—you didn't suppose you'd find the Paddington Canal in these parts, did you? This is big enough for all they want. (A gondola goes by lurchily, crowded with pot-hatted passengers, smoking pipes, and wearing the uncomfortable smile of children enjoying their first elephant-ride.) That's one o' these 'ere gondoalers—it's a rum-looking concern, ain't it? But I suppose you get used to 'em—(philosophically)—like everything else!

The P.M. It gives me the creeps to look at 'em. Talk about 'earses!

The Opt. Husb. Well, look 'ere, we've come out to enjoy ourselves—what d'ye say to having a ride in one, eh?

The P.M. You won't ketch me trusting myself in one o' them tituppy things, so don't you deceive yourself!

The Opt. Husb. Oh, it's on'y two foot o' warm water if you do tip over. Come on! (Hailing Gondolier, who has just landed his cargo.) 'Ere, 'ow much'll you take the lot of us for, hey?

Gondolier (gesticulating). Teekits! you tek teekits—là—you vait!

Jem. He means we've got to go to the orfice and take tickets and stand in a cue, d'yer see?

The P.M. Me go and form a cue down there and get squeeged like at the Adelphi Pit, all to set in a rickety gondoaler! I can see all I want to see without messing about in one o' them things!

The Others. Well, I dunno as it's worth the extry sixpence, come to think of it. (They pass on, contentedly.)

Jem. We're on the Rialto Bridge now, LIZZIE, d'ye see? The one in SHAKSPEARE, you know.

Lizzie. That's the one they call the "Bridge o' Sighs," ain't it? (Hazily.) Is that because there's shops on it?

Jem. I dessay. Shops—or else suicides.

Lizzie (more hazily than ever). Ah, the same as the Monument. (They walk on with a sense of mental enlargement.)

Mrs. Lavender Salt. It's wonderfully like the real thing, LAVENDER, isn't it? Of course they can't quite get the true Venetian atmosphere!

Mr. L.S. Well, MIMOSA, they'd have the Sanitary Authorities down on them if they did, you know!

Mrs. L.S. Oh, you're so horribly unromantic! But, LAVENDER, couldn't we get one of those gondolas and go about. It would be so lovely to be in one again, and fancy ourselves back in dear Venice, now wouldn't it?

Mr. L.S. The illusion is cheap at sixpence; so come along, MIMOSA!

[He secures, tickets, and presently the LAVENDER SALTS, find themselves part of a long queue, being marshalled between barriers by Italian gendarmes in a state of politely suppressed amusement.

Mrs. L.S. (over her shoulder to her husband, as she imagines). I'd no idea we should have to go through all this! Must we really herd in with all these people? Can't we two manage to get a gondola all to ourselves?

A Voice (not LAVENDER's—in her ear). I'm sure I'm 'ighly flattered, Mum, but I'm already suited; yn't I, DYSY?

[DYSY corroborates his statement with unnecessary emphasis.

A Sturdy Democrat (in front, over his shoulder). Pity yer didn't send word you was coming, Mum, and then they'd ha' kep' the place clear of us common people for yer! [Mrs. L.S. is sorry she spoke.

IN THE GONDOLA.—Mr. and Mrs. L.S. are seated in the back seat, supported on one side by the Humorous 'ARRY and his Fiancée, and on the other by a pale, bloated youth, with a particularly rank cigar, and the Sturdy Democrat, whose two small boys occupy the seat in front.

The St. Dem. (with malice aforethought). If you two lads ain't [pg 53] got room there, I dessay this lady won't mind takin' one of yer on her lap. (To Mrs. L.S., who is frozen with horror at the suggestion.) They're 'umin beans, Mum, like yerself!

Mrs. L.S. (desperately ignoring her other neighbours). Isn't that lovely balcony there copied from the one at the Pisani, LAVENDER—or is it the Contarini? I forget.

Mr. L.S. Don't remember—got the Rialto rather well, haven't they? I suppose that's intended for the dome of the Salute down there—not quite the outline, though, if I remember right. And, if that's the Campanile of St. Mark, the colour's too brown, eh?

The Hum. 'Arry (with intention). Oh, I sy, DYSY, yn't that the Kempynoily of Kennington Oval, right oppersite? and 'aven't they got the Grand Kinel in the Ole Kent Road proper, eh?

Dysy (playing up to him, with enjoyment). Jest 'aven't they! On'y I don't quoite remember whether the colour o' them gas-lamps is correct. But there, if we go on torkin' this w'y, other parties might think we wanted to show orf!

Mrs. L.S. Do you remember our last gondola expedition, LAVENDER, coming home from the Giudecca in that splendid sunset?

The Hum. A. Recklect you and me roidin' 'ome from Walworth on a rhinebow, DYSY, eh?

Chorus of Chaff from the bridges and terraces as they pass. 'Ullo, 'ere comes another boat-load! 'Igher up, there!... Four-wheeler!... Ain't that toff in the tall 'at enjoyin' himself? Quite a 'appy funeral! &c., &c.

Mrs. L.S. (faintly, as they enter the Canal in front of the Stage). LAVENDER, dear, I really can't stand this much longer!

Mr. L.S. (to the Bloated Youth). Might I ask you, Sir, not to puff your smoke in this lady's face—it's extremely unpleasant for her!

The B.Y. All right, Mister, I'm always ready to oblige a lydy—but—(with wounded pride)—as to its bein' unpleasant, yer know, all I can tell yer is—(with sarcasm)—that this 'appens to be one of the best tuppeny smokes in 'Ammersmith!

Mr. L.S. (diplomatically). I am sure of that—from the aroma, but if you could kindly postpone its enjoyment for a little while, we should be extremely obliged!

The B.Y. Well, I must keep it aloive, yer know. If there's anyone 'ere that understands cigars, they'll bear me out as it never smokes the same when you once let it out.

[The other Passengers confirm him in this epicurean dictum, whereupon he sucks the cigar at intervals behind Mrs. L.S.'s back, during the remainder of the trip.

Mr. L.S. (to Mrs. L.S. when they are alone again). Well, MIMOSA, illusion successful, eh? Mrs. L.S. Oh, don't!

My own, my loved, my Cigarette,

My dainty joy disguised in tissue,

What fate can make your slave regret

The day when first he dared to kiss you?

I had smoked briars, like to most

Who joy in smoking, and had been a

Too ready prey to those who boast

Their bonded stores of Reina Fina.

In honeydew had steeped my soul

Had been of cherry pipes a cracker,

And watched the creamy meerschaum's bowl

Grow weekly, daily, hourly blacker.

Read CALVERLEY and learnt by heart

The lines he celebrates the weed in;

And blew my smoke in rings, an art

That many try, but few succeed in.

In fact of nearly every style

Of smoke I was a kindly critic,

Though I had found Manillas vile,

And Trichinopolis mephitic.

The stout tobacco-jar became

Within my smoking-room a fixture;

I heard my friends extol by name

Each one his own peculiar mixture.

And tried them every one in turn

(O varium, tobacco, semper!);

The strong I found too apt to burn

My tongue, the week to try my temper.

And all were failures, and I grew

More tentative and undecided,

Consulted friends, and found they knew

As little as or less than I did.

Havannah yielded up her pick

Of prime cigars to my fruition;

I bought a case, and some went "sick."

The rest were never in condition.

Until in sheer fatigue I turned

To you, tobacco's white-robed tyro,

And from your golden legend learned

Your maker dwelt and wrought in Cairo.

O worshipped wheresoe'er I roam,

As fondly as a wife by some is,

Waif from the far Egyptian home

Of Pharaohs, crocodiles, and mummies;

Beloved, in spite of jeer and frown;

The more the Philistines assail you,

The more the doctors run you down,

The more I puff you—and inhale you.

Though worn with toil and vexed with strife

(Ye smokers all, attend and hear me),

Undaunted still I live my life,

With you, my Cigarette, to cheer me.

"HOW CHARMING YOU LOOK, DEAR MRS. BELLAMY—AS USUAL! WOULD YOU MIND TELLING ME WHO MAKES YOUR LOVELY FROCKS? I'M SO DISSATISFIED WITH MY DRESSMAKER!"

"OH, CERTAINLY. MRS. CHIFFONNETTE, OF BOND STREET."

"CHIFFONNETTE! WHY, I'VE BEEN TO HER FOR YEARS! THE WRETCH! I WONDER WHY SHE SUITS YOU SO MUCH BETTER, NOW!"

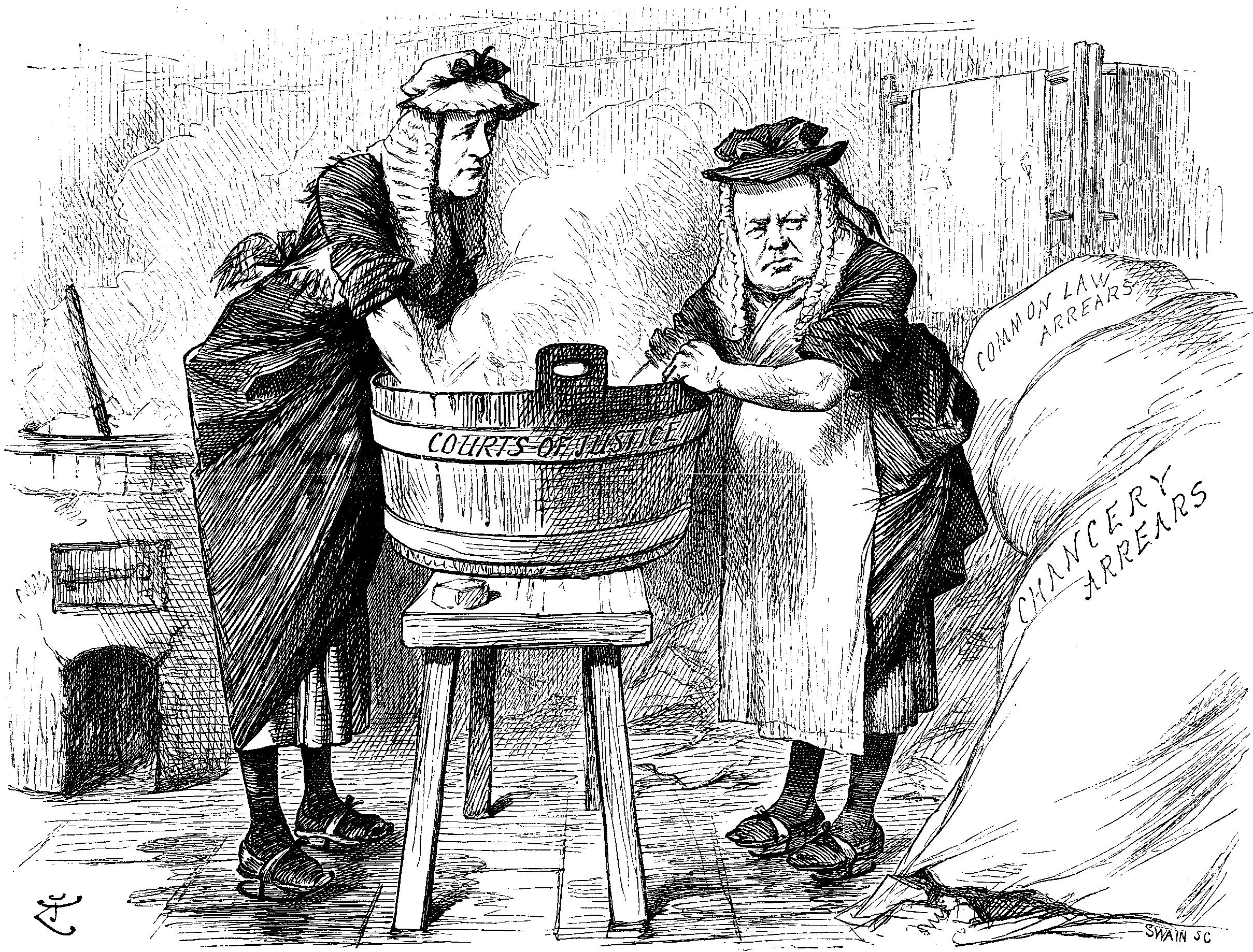

["The whole legal machinery is out of gear, and the country is too busy to put it right."—Law Times.]

Wich I say, Missis 'ALSBURY, Mum,

We are all getting into a quand'ry;

You and me can no longer be dumb,

Seein' how we're the heads of the Laundry:

It is all very well to stand 'ere,

Sooperintending the soaping and rinsing;

Old pleas for delay, I much fear,

Are no longer entirely conwincing.

Just look at the Linen—in 'eaps!

And no one can say it ain't dirty!

Our clients, a-grumbling they keeps,

And some of 'em seem getting shirty.

Wotever, my dear, shall we do?

Two parties 'as axed me that question;

And now I just puts it to you,

And I 'ope you can make some suggestion.

My dear Missis COLEY, I own

I ain't heard from the parties you 'int at.

But them Linen-'eaps certny has grown,

Wich their bulk I 'ave just took a squint at.

We sud, and we rub, and we scrub.

And the pile 'ardly seems to diminish.

It tires us poor Slaves of the Tub,

And the doose only knows when we'll finish,

Percisely, my dear, but it's that,

As the Public insists upon knowin',

Missis MATHEW 'as told me so, pat,

Wich likeways 'as good Missis BOWEN.

You can't floor their argyments, quite,

'Owsomever you twirl 'em or 'twist 'em;

They say, and I fear they are right,

There is somethink all wrong with our System!

Our System! Well, well, my good soul,

You know 'twasn't us as inwented it.

We wouldn't have got into this 'ole,

If you and me could 'ave perwented it.

I know there's no end of a block,

That expenses is running up awfully;

The sight of it gives me a shock,

But 'ow can we alter it—lawfully?

I fear, Mum, I very much fear,

That word doesn't strike so much terror

As once on the dull public ear;

Times change. Mum, they do, make no error!

Our clients complain of the cost,

And lots of Commercials is leaving us.

I think, Mum, afore more is lost,

We had best own the block is—well grieving us!

There can't be no 'arm, dear, in that.

Let's write to the papers and 'int it.

I know with your pen you are pat,

And the Times will be 'appy to print it.

If we are to git through that lot,

We must 'ave some more 'elp—that's my notion!

Let's strike whilst the iron is 'ot,

The Public may trust our dewotion.

We'll call the chief Laundresses round;

Some way we no doubt shall discover.

At least, dear, 'twill 'ave a good sound,

If we meet, and—well talk the thing over!

[Left doing so.

Did you ever 'ear our music? What, never? There's a shame;

I tell yer it's golopshus, we do 'ave such a game.

When the sun's a-shinin' brightly, when the fog's upon the town,

When the frost 'as bust the water-pipes, when rain comes pourin' down;

In the mornin' when the costers come a-shoutin' with their mokes,

In the evenin' when the gals walk out a-spoonin' with their blokes,

When Mother's slappin' BILLY, or when Father wants 'is tea,

When the boys are in the "Spotted Dog" a 'avin' of a spree,

No matter what the weather is, or what the time o' day,

Our music allus visits us, and never goes away.

And when they've tooned theirselves to-rights, I tell yer it's a treat

Just to listen to the lot of 'em a-playin' in our street.

There's a chap as turns the orgin—the best I ever 'eard—

Oh lor' he does just jabber, but you can't make out a word.

I can't abear Italians, as allus uses knives,

And talks a furrin lingo all their miserable lives.

But this one calls me BELLA—which my Christian name is SUE—

And 'e smiles and turns 'is orgin very proper, that he do.

Sometimes 'e plays a polker and sometimes it's a march,

And I see 'is teeth all shinin' through 'is lovely black mustarch.

And the little uns dance round him, you'd laugh until you cried

If you saw my little brothers do their 'ornpipes side by side,

And the gals they spin about as well, and don't they move their feet,

When they 'ear that pianner-orgin man, as plays about our street.

There's a feller plays a cornet too, and wears a ulster coat,

My eye, 'e does puff out 'is cheeks a-tryin' for 'is note.

It seems to go right through yer, and, oh, it's right-down rare

When 'e gives us "Annie Laurie" or "Sweet Spirit, 'ear my Prayer";

'E's so stout that when 'e's blowin' 'ard you think 'e must go pop;

And 'is nose is like the lamp (what's red) outside a chemist's shop.

And another blows the penny-pipe,—I allus thinks it's thin,

And I much prefers the cornet when 'e ain't bin drinkin' gin.

And there's Concertina-JIMMY, it makes yer want to shout

When 'e acts just like a windmill and waves 'is arms about.

Oh, I'll lay you 'alf a tanner, you'll find it 'ard to beat

The good old 'eaps of music that they gives us in our street.

And a pore old ragged party, whose shawl is shockin' torn,

She sings to suit 'er 'usband while 'e plays on so forlorn.

'Er voice is dreadful wheezy, and I can't exactly say

I like 'er style of singin' "Tommy Dodd" or "Nancy Gray."

But there, she does 'er best, I'm sure; I musn't run 'er down,

When she's only tryin' all she can to earn a honest brown.

Still, though I'm mad to 'ear 'em play, and sometimes join the dance,

I often wish one music gave the other kind a chance.

The orgin might have two days, and the cornet take a third,

While the pipe-man tried o' Thursdays 'ow to imitate a bird.

But they allus comes together, singin' playin' as they meet

With their pipes and 'orns and orgins in the middle of our street.

But there, I can't stand chatterin', pore mother's mortal bad,

And she's got to work the whole day long to keep things straight for dad.

Complain? Not she. She scrubs and rubs with all 'er might and main,

And the lot's no sooner finished but she's got to start again.

There's a patch for JOHNNY's jacket, a darn for BILLY's socks,

And an hour or so o' needlework a mendin' POLLY's frocks;

With floors to wash, and plates to clean, she'd soon be skin and bone

('Er cough's that aggravatin') if she did it all alone.

There'll be music while we're workin' to keep us on the go—

I like my tunes as fast as fast, pore mother likes 'em slow—

Ah! we don't get much to laugh at, nor yet too much to eat,

And the music stops us thinkin' when they play it in the street.

"MARIE, COME UP!"—When Miss MARIE LLOYD, who, unprofessionally, when at home, is known as Mrs. PERCY COURTENAY, which her Christian name is MATILDA, recently appeared at Bow-Street Police Court, having summoned her husband for an assault, the Magistrate, Mr. LUSHINGTON, ought to have called on the Complainant to sing "Whacky, Whacky, Whack!" which would have come in most appropriately. Let us hope that the pair will make it up, and, as the story-books say, "live happily ever afterwards."

NIGHT LIGHTS.—Rumour has it that certain Chorus Ladies have objected to wearing electric glow-lamps in their hair. Was it for fear of becoming too light-headed?

DEAR MR. PUNCH,—Having seen in the pages of one of your contemporaries several deeply interesting letters telling of "the Courtesy of the CAVENDISH," I think it will be pleasing to your readers to learn that I have a fund of anecdote concerning the politeness—the true politeness—of many other members of the Peerage. Perhaps you will permit me to give you a few instances of what I may call aristocratic amiability.

On one occasion the Duke of DITCHWATER and a Lady entered the same omnibus simultaneously. There was but one seat, and noticing that His Grace was standing, I called attention to the fact. "Certainly," replied His Grace, with a quiet smile, "but if I had sat down, the Lady would not have enjoyed her present satisfactory position!" The Lady herself had taken the until then vacant place!

Shortly afterwards I met Viscount VERMILION walking in an opposite direction to the path I myself was pursuing. "My Lord," I murmured, removing my hat, "I was quite prepared to step into the gutter." "It was unnecessary," returned his Lordship, graciously, "for as the path was wide, there was room enough for both of us to pass on the same pavement!"

On a very wet evening I saw My Lord TOMNODDICOMB coming from a shop in Piccadilly. Noticing that his Lordship had no defence against the weather, I ventured to offer the Peer my parapluie.

"Please let me get into my carriage," observed his Lordship. Then discovering, from my bowing attitude, that I meant no insolence by my suggestion, he added,—"And as for your umbrella—surely on this rainy night you can make use of it yourself?"

Yet again. The Marchioness of LOAMSHIRE was on the point of crossing a puddle.

Naturally I divested myself of my greatcoat, and threw it as a bridge across her Ladyship's dirty walk.

The Marchioness smiled, but her Ladyship has never forgotten the circumstance, and I have the coat still by me.

And yet some people declare that the wives of Members of the House of Lords are wanting in consideration!

Believe me, dear Mr. Punch,

The Cringeries, Low Booington.

NOTICE—No. XXV. of "Travelling Companions" next week.

["All the judicial wisdom of the Supreme Court has met in solemn and secret conclave, heralded by letters from the heads of the Bench, admitting serious evils in the working of the High Court of Justice; a full working day was appropriated for the occasion; the learned Judges met at 11 A.M. (nominally) and rose promptly for luncheon, and for the day, at 1·30 P.M. Two-and-a-half hours' work, during which each of the twenty-eight judicial personages no doubt devoted all his faculties and experience to the discovery, discussion, and removal of the admittedly numerous defects in the working of the Judicature Acts! Two-and-a-half hours, which might have been stolen from the relaxations of a Saturday afternoon! Two-and-a-half hours, for which the taxpayers of the United Kingdom pay some eight hundred guineas! Truly the spectacle is eminently calculated to inspire the country with confidence and hopes of reform."—Extract from Letter to the Times.]

SCENE—A Room at the Royal Courts. Lord CHANCELLOR, Lord CHIEF JUSTICE, MASTER of the ROLLS, Lords Justices, Justices.

L.C. Well, I'm very glad to see you all looking so well, but can anyone tell me why we've met at all?

L.C.J. Talking of meetings, do you remember that Exeter story dear old JACK TOMPKINS used to tell on the Western Circuit?

[Proceeds to tell JACK TOMPKINS's story at great length to great interest of Chancery Judges.

M.R. (who has listened with marked impatience). Why, my dear fellow, it isn't a Western Circuit story at all. It was on the Northern Circuit at Appleby.

[Proceeds to tell the same story all over again, substituting Appleby for Exeter. At the conclusion of story, Great laughter from Chancery Judges. Common Law Judges look bored, having all told same story on and about their own Circuits.

L.C. Very good—very good—used to tell it myself on the South Wales Circuit—but what have we met for?

Lord Justice A. I say, what do you think about this cross-examination fuss? It seems to me—

L.C.J. Talking of cross-examination—do you fellows remember the excellent story dear old JOHNNIE BROWBEAT used to tell about the Launceston election petition?

[pg 60][Proceeds to tell story in much detail. L.C. looks uncomfortable at its conclusion.

M.R. (cutting in). Why, my dear fellow, it wasn't Launceston at all, it was Lancaster, and—

[Tells story all over again to the Chancery Judges.

L.C. Yes—excellent. I thought it took place at Chester—but really, now, we must get to business. So, first of all, will anyone kindly tell me what the business is?

Mr. Justice A. (a very young Judge). Well, the fact is, I believe the Public—

Chorus of Judges. The what?

Mr. Justice A. (with hesitation). Why—I was going to say there seems to be a sort of discontent amongst the Public—

L.C. (with dignity). Really, really—what have we to do with the Public? But in case there should be any truth in this extraordinary statement, I think we might as well appoint a Committee to look into it, and then we can meet again some day and hear what it is all about.

L.C.J. Yes, a Committee by all means; the smaller the better. "Too many cooks," as dear old HORACE puts it.

M.R. Talking of cooks, isn't it about lunch time?

[General consensus of opinion in favour of lunching. As they adjourn, L.C.J. detains Chancery Judges to tell them a story about something that happened at Bodmin, and, to prevent mistakes, tells it in West Country dialect. M.R. immediately repeats it in strong Yorkshire, and lays the venue at Bradford. Result; that the whole of HER MAJESTY's Courts in London were closed for one day.

I remember, I remember

The Law when I was born,

The Serjeants, brothers of the coif,

The Judges dead and gone.

The Judicature Acts to them

Were utterly unknown;

It was a fearful ignorance—

Oh, would it were my own!

I remember, I remember

The worthy "Proctor" race,

The "Posteas," and the "Elegits,"

The "Actions on the Case."

The "Error" each Attorney's Clerk

Did wilfully abet,

The days of "Bills" in Equity—

Some bills are living yet!

I remember, I remember

The years of "Jarndyce" jaw,

The lively game of shuttlecock

'Twixt Equity and Law.

Tribunals then were "Courts" indeed

That are "Divisions" now,

And Silken Gowns have feared the frowns

Upon a "Baron's" brow.

We remember, we remember

The flourishing of trumps,

When Parliament took up our wrongs,

And manned the legal pumps.

Those noble Acts (they said) would end

Obstructions and delay,

And ne'er again would litigants

The piper have to pay.

I remember, I remember

Expenses, mountains high;

I used to think, when duly "taxed,"

They'd vanish by-and-by.

It was a foolish confidence,

But now 'tis little joy

To know that Law's as slow and dear

As when I was a boy!

I would I loved some belted Earl,

Some Baronet, or K.C.B.,

But I'm a most unhappy girl,

And no such luck's in store for me!

I would I loved some Soldier bold,

Who leads his troops where cannons pop,

But if the bitter truth be told—

I love a man who walks a shop!

For oh! a King of Men is he—

With princely strut and stiffened spine—

So his, and his alone, shall be,

This fondly foolish heart of mine!

On Remnant Days—from morn till night,

When blows fall fast, and words run high,

When frenzied females fiercely fight

For bargains that they long to buy—

From hot attack he does not flinch,

But stands his ground with visage pale,

And all the time looks every inch

The Hero of that Summer Sale!

For oh! a King of Men is he—

Whom shop-assistants call to "Sign!"

So his, and his alone, shall be

This fondly foolish heart of mine!

MONDAY, Jan. 18, 1892. "Bath and West of England's Society's Cheese School at Frome." Of this School, the Times, judging by results, speaks highly of "the practical character of the instruction given at the School." This is a bad look-out for Eton and Harrow, not to say for Winchester and Westminster also. All parents who wish their children to be "quite the cheese" in Society generally, and particularly for Bath and the West of England, where, of course, Society is remarkably exclusive, cannot do better, it is evident, than send them to the Bath and West of England Cheese School.

ON THE TRAILL.—It is suggested that in future M.P. should stand for Minor Poet. Would this satisfy Mr. LEWIS MORRIS? Or would he insist on being gazetted as a Major?

One of the Baron's Deputy-Readers has been looking through Mr. G.W. HENLEY's Lyra Heroica; a Book of Verse for Boys. DAVID NUTT, London.) This is his appreciation:—Mr. HENLEY has tacked his name to a collection which contains some noble poems, some (but not much) trash, and a good many pieces, which, however poetical they may be, are certainly not heroic, seeing that they do not express "the simpler sentiments, and the more elemental emotions" (I use Mr. HENLEY's prefatory words), and are scarcely the sort of verse that boys are likely, or ought to care about. To be sure, Mr. HENLEY guards himself on the score of his "personal equation"—I trust his boys understand what he means. My own personal equation makes me doubt whether Mr. HENLEY has done well in including such pieces as, for instance, HERBERT's "Memento Mori," CURRAN's "The Deserter," SWINBURNE's "The Oblation," and ALFRED AUSTIN's "Is Life Worth Living?" If Mr. HENLEY, or anybody else who happens to possess a personal equation, will point out to me the heroic quality in these poems, I shall feel deeply grateful. And how, in the name of all that is or ever was heroic, has "Auld Lang Syne" crept into this collection of heroic verse? As for Mr. ALFRED AUSTIN, I cannot think by what right he secures a place in such a compilation. I have rarely read a piece of his which did not contain at least one glaring infelicity. In "Is Life Worth Living?" he tells us of "blithe herds," which (in compliance with the obvious necessities of rhyme, but for no other reason)

"Wend homeward with unweary feet,

Carolling like the birds."

Further on we find that

"England's trident-sceptre roams

Her territorial seas,"

merely because the unfortunate sceptre has to rhyme somehow to "English homes."

But I have a further complaint against Mr. HENLEY. He presumes, in the most fantastic manner, to alter the well-known titles of celebrated poems. "The Isles of Greece" is made to masquerade as "The Glory that was Greece"; "Auld Lang Syne" becomes "The Goal of Life," and "Tom Bowline" is converted into "The Perfect Sailor." This surely (again I use the words of Mr. HENLEY) "is a thing preposterous, and distraught." On the whole, I cannot think that Mr. HENLEY has done his part well. His manner is bad. His selection, it seems to me, is open to grave censure, on broader grounds than the mere personally equational of which he speaks, and his choppings, and sub-titles, and so forth, are not commendable. The irony of literary history has apparently ordained that Mr. HENLEY should first patronise, and then "cut," both CAMPBELL and MACAULAY. Was the shade of MACAULAY disturbed when he learnt that Mr. HENLEY considered his "Battle of Naseby" both "vicious and ugly"?

NOTICE.—Rejected Communications or Contributions, whether MS., Printed Matter, Drawings, or Pictures of any description, will in no case be returned, not even when accompanied by a Stamped and Addressed Envelope, Cover, or Wrapper. To this rule there will be no exception.

End of the Project Gutenberg EBook of Punch, Or The London Charivari, Volume

102, January 30, 1892, by Various

*** END OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK PUNCH ***

***** This file should be named 14272-h.htm or 14272-h.zip *****

This and all associated files of various formats will be found in:

http://www.gutenberg.net/1/4/2/7/14272/

Produced by Malcolm Farmer, William Flis, and the PG Online

Distributed Proofreading Team

Updated editions will replace the previous one--the old editions

will be renamed.

Creating the works from public domain print editions means that no

one owns a United States copyright in these works, so the Foundation

(and you!) can copy and distribute it in the United States without

permission and without paying copyright royalties. Special rules,

set forth in the General Terms of Use part of this license, apply to

copying and distributing Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works to

protect the PROJECT GUTENBERG-tm concept and trademark. Project

Gutenberg is a registered trademark, and may not be used if you

charge for the eBooks, unless you receive specific permission. If you

do not charge anything for copies of this eBook, complying with the

rules is very easy. You may use this eBook for nearly any purpose

such as creation of derivative works, reports, performances and

research. They may be modified and printed and given away--you may do

practically ANYTHING with public domain eBooks. Redistribution is

subject to the trademark license, especially commercial

redistribution.

*** START: FULL LICENSE ***

THE FULL PROJECT GUTENBERG LICENSE

PLEASE READ THIS BEFORE YOU DISTRIBUTE OR USE THIS WORK

To protect the Project Gutenberg-tm mission of promoting the free

distribution of electronic works, by using or distributing this work

(or any other work associated in any way with the phrase "Project

Gutenberg"), you agree to comply with all the terms of the Full Project

Gutenberg-tm License (available with this file or online at

http://gutenberg.net/license).

Section 1. General Terms of Use and Redistributing Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic works

1.A. By reading or using any part of this Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic work, you indicate that you have read, understand, agree to

and accept all the terms of this license and intellectual property

(trademark/copyright) agreement. If you do not agree to abide by all

the terms of this agreement, you must cease using and return or destroy

all copies of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works in your possession.

If you paid a fee for obtaining a copy of or access to a Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic work and you do not agree to be bound by the

terms of this agreement, you may obtain a refund from the person or

entity to whom you paid the fee as set forth in paragraph 1.E.8.

1.B. "Project Gutenberg" is a registered trademark. It may only be

used on or associated in any way with an electronic work by people who

agree to be bound by the terms of this agreement. There are a few

things that you can do with most Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works

even without complying with the full terms of this agreement. See

paragraph 1.C below. There are a lot of things you can do with Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works if you follow the terms of this agreement

and help preserve free future access to Project Gutenberg-tm electronic

works. See paragraph 1.E below.

1.C. The Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation ("the Foundation"

or PGLAF), owns a compilation copyright in the collection of Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works. Nearly all the individual works in the

collection are in the public domain in the United States. If an

individual work is in the public domain in the United States and you are

located in the United States, we do not claim a right to prevent you from

copying, distributing, performing, displaying or creating derivative

works based on the work as long as all references to Project Gutenberg

are removed. Of course, we hope that you will support the Project

Gutenberg-tm mission of promoting free access to electronic works by

freely sharing Project Gutenberg-tm works in compliance with the terms of

this agreement for keeping the Project Gutenberg-tm name associated with

the work. You can easily comply with the terms of this agreement by

keeping this work in the same format with its attached full Project

Gutenberg-tm License when you share it without charge with others.

1.D. The copyright laws of the place where you are located also govern

what you can do with this work. Copyright laws in most countries are in

a constant state of change. If you are outside the United States, check

the laws of your country in addition to the terms of this agreement

before downloading, copying, displaying, performing, distributing or

creating derivative works based on this work or any other Project

Gutenberg-tm work. The Foundation makes no representations concerning

the copyright status of any work in any country outside the United

States.

1.E. Unless you have removed all references to Project Gutenberg:

1.E.1. The following sentence, with active links to, or other immediate

access to, the full Project Gutenberg-tm License must appear prominently

whenever any copy of a Project Gutenberg-tm work (any work on which the

phrase "Project Gutenberg" appears, or with which the phrase "Project

Gutenberg" is associated) is accessed, displayed, performed, viewed,

copied or distributed:

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net

1.E.2. If an individual Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work is derived

from the public domain (does not contain a notice indicating that it is

posted with permission of the copyright holder), the work can be copied

and distributed to anyone in the United States without paying any fees

or charges. If you are redistributing or providing access to a work

with the phrase "Project Gutenberg" associated with or appearing on the

work, you must comply either with the requirements of paragraphs 1.E.1

through 1.E.7 or obtain permission for the use of the work and the

Project Gutenberg-tm trademark as set forth in paragraphs 1.E.8 or

1.E.9.

1.E.3. If an individual Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work is posted

with the permission of the copyright holder, your use and distribution

must comply with both paragraphs 1.E.1 through 1.E.7 and any additional

terms imposed by the copyright holder. Additional terms will be linked

to the Project Gutenberg-tm License for all works posted with the

permission of the copyright holder found at the beginning of this work.

1.E.4. Do not unlink or detach or remove the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License terms from this work, or any files containing a part of this

work or any other work associated with Project Gutenberg-tm.

1.E.5. Do not copy, display, perform, distribute or redistribute this

electronic work, or any part of this electronic work, without

prominently displaying the sentence set forth in paragraph 1.E.1 with

active links or immediate access to the full terms of the Project

Gutenberg-tm License.

1.E.6. You may convert to and distribute this work in any binary,

compressed, marked up, nonproprietary or proprietary form, including any

word processing or hypertext form. However, if you provide access to or

distribute copies of a Project Gutenberg-tm work in a format other than

"Plain Vanilla ASCII" or other format used in the official version

posted on the official Project Gutenberg-tm web site (www.gutenberg.net),

you must, at no additional cost, fee or expense to the user, provide a

copy, a means of exporting a copy, or a means of obtaining a copy upon

request, of the work in its original "Plain Vanilla ASCII" or other

form. Any alternate format must include the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License as specified in paragraph 1.E.1.

1.E.7. Do not charge a fee for access to, viewing, displaying,

performing, copying or distributing any Project Gutenberg-tm works

unless you comply with paragraph 1.E.8 or 1.E.9.

1.E.8. You may charge a reasonable fee for copies of or providing

access to or distributing Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works provided

that

- You pay a royalty fee of 20% of the gross profits you derive from

the use of Project Gutenberg-tm works calculated using the method

you already use to calculate your applicable taxes. The fee is

owed to the owner of the Project Gutenberg-tm trademark, but he

has agreed to donate royalties under this paragraph to the

Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation. Royalty payments

must be paid within 60 days following each date on which you

prepare (or are legally required to prepare) your periodic tax

returns. Royalty payments should be clearly marked as such and

sent to the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation at the

address specified in Section 4, "Information about donations to

the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation."

- You provide a full refund of any money paid by a user who notifies

you in writing (or by e-mail) within 30 days of receipt that s/he

does not agree to the terms of the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License. You must require such a user to return or

destroy all copies of the works possessed in a physical medium

and discontinue all use of and all access to other copies of

Project Gutenberg-tm works.

- You provide, in accordance with paragraph 1.F.3, a full refund of any

money paid for a work or a replacement copy, if a defect in the

electronic work is discovered and reported to you within 90 days

of receipt of the work.

- You comply with all other terms of this agreement for free

distribution of Project Gutenberg-tm works.

1.E.9. If you wish to charge a fee or distribute a Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic work or group of works on different terms than are set

forth in this agreement, you must obtain permission in writing from

both the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation and Michael

Hart, the owner of the Project Gutenberg-tm trademark. Contact the

Foundation as set forth in Section 3 below.

1.F.

1.F.1. Project Gutenberg volunteers and employees expend considerable

effort to identify, do copyright research on, transcribe and proofread

public domain works in creating the Project Gutenberg-tm

collection. Despite these efforts, Project Gutenberg-tm electronic

works, and the medium on which they may be stored, may contain

"Defects," such as, but not limited to, incomplete, inaccurate or

corrupt data, transcription errors, a copyright or other intellectual

property infringement, a defective or damaged disk or other medium, a

computer virus, or computer codes that damage or cannot be read by

your equipment.

1.F.2. LIMITED WARRANTY, DISCLAIMER OF DAMAGES - Except for the "Right

of Replacement or Refund" described in paragraph 1.F.3, the Project

Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation, the owner of the Project

Gutenberg-tm trademark, and any other party distributing a Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic work under this agreement, disclaim all

liability to you for damages, costs and expenses, including legal

fees. YOU AGREE THAT YOU HAVE NO REMEDIES FOR NEGLIGENCE, STRICT

LIABILITY, BREACH OF WARRANTY OR BREACH OF CONTRACT EXCEPT THOSE

PROVIDED IN PARAGRAPH F3. YOU AGREE THAT THE FOUNDATION, THE

TRADEMARK OWNER, AND ANY DISTRIBUTOR UNDER THIS AGREEMENT WILL NOT BE

LIABLE TO YOU FOR ACTUAL, DIRECT, INDIRECT, CONSEQUENTIAL, PUNITIVE OR

INCIDENTAL DAMAGES EVEN IF YOU GIVE NOTICE OF THE POSSIBILITY OF SUCH

DAMAGE.

1.F.3. LIMITED RIGHT OF REPLACEMENT OR REFUND - If you discover a

defect in this electronic work within 90 days of receiving it, you can

receive a refund of the money (if any) you paid for it by sending a

written explanation to the person you received the work from. If you

received the work on a physical medium, you must return the medium with

your written explanation. The person or entity that provided you with

the defective work may elect to provide a replacement copy in lieu of a

refund. If you received the work electronically, the person or entity

providing it to you may choose to give you a second opportunity to

receive the work electronically in lieu of a refund. If the second copy

is also defective, you may demand a refund in writing without further

opportunities to fix the problem.

1.F.4. Except for the limited right of replacement or refund set forth

in paragraph 1.F.3, this work is provided to you 'AS-IS' WITH NO OTHER

WARRANTIES OF ANY KIND, EXPRESS OR IMPLIED, INCLUDING BUT NOT LIMITED TO

WARRANTIES OF MERCHANTIBILITY OR FITNESS FOR ANY PURPOSE.

1.F.5. Some states do not allow disclaimers of certain implied

warranties or the exclusion or limitation of certain types of damages.

If any disclaimer or limitation set forth in this agreement violates the

law of the state applicable to this agreement, the agreement shall be

interpreted to make the maximum disclaimer or limitation permitted by

the applicable state law. The invalidity or unenforceability of any

provision of this agreement shall not void the remaining provisions.

1.F.6. INDEMNITY - You agree to indemnify and hold the Foundation, the

trademark owner, any agent or employee of the Foundation, anyone

providing copies of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works in accordance

with this agreement, and any volunteers associated with the production,

promotion and distribution of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works,

harmless from all liability, costs and expenses, including legal fees,

that arise directly or indirectly from any of the following which you do

or cause to occur: (a) distribution of this or any Project Gutenberg-tm

work, (b) alteration, modification, or additions or deletions to any

Project Gutenberg-tm work, and (c) any Defect you cause.

Section 2. Information about the Mission of Project Gutenberg-tm

Project Gutenberg-tm is synonymous with the free distribution of

electronic works in formats readable by the widest variety of computers

including obsolete, old, middle-aged and new computers. It exists

because of the efforts of hundreds of volunteers and donations from

people in all walks of life.

Volunteers and financial support to provide volunteers with the

assistance they need, is critical to reaching Project Gutenberg-tm's

goals and ensuring that the Project Gutenberg-tm collection will

remain freely available for generations to come. In 2001, the Project

Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation was created to provide a secure

and permanent future for Project Gutenberg-tm and future generations.

To learn more about the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation

and how your efforts and donations can help, see Sections 3 and 4

and the Foundation web page at http://www.pglaf.org.

Section 3. Information about the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive

Foundation

The Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation is a non profit

501(c)(3) educational corporation organized under the laws of the

state of Mississippi and granted tax exempt status by the Internal

Revenue Service. The Foundation's EIN or federal tax identification

number is 64-6221541. Its 501(c)(3) letter is posted at

http://pglaf.org/fundraising. Contributions to the Project Gutenberg

Literary Archive Foundation are tax deductible to the full extent

permitted by U.S. federal laws and your state's laws.

The Foundation's principal office is located at 4557 Melan Dr. S.

Fairbanks, AK, 99712., but its volunteers and employees are scattered

throughout numerous locations. Its business office is located at

809 North 1500 West, Salt Lake City, UT 84116, (801) 596-1887, email

business@pglaf.org. Email contact links and up to date contact

information can be found at the Foundation's web site and official

page at http://pglaf.org

For additional contact information:

Dr. Gregory B. Newby

Chief Executive and Director

gbnewby@pglaf.org

Section 4. Information about Donations to the Project Gutenberg

Literary Archive Foundation

Project Gutenberg-tm depends upon and cannot survive without wide

spread public support and donations to carry out its mission of

increasing the number of public domain and licensed works that can be

freely distributed in machine readable form accessible by the widest

array of equipment including outdated equipment. Many small donations

($1 to $5,000) are particularly important to maintaining tax exempt

status with the IRS.

The Foundation is committed to complying with the laws regulating

charities and charitable donations in all 50 states of the United

States. Compliance requirements are not uniform and it takes a

considerable effort, much paperwork and many fees to meet and keep up

with these requirements. We do not solicit donations in locations

where we have not received written confirmation of compliance. To

SEND DONATIONS or determine the status of compliance for any

particular state visit http://pglaf.org

While we cannot and do not solicit contributions from states where we

have not met the solicitation requirements, we know of no prohibition

against accepting unsolicited donations from donors in such states who

approach us with offers to donate.

International donations are gratefully accepted, but we cannot make

any statements concerning tax treatment of donations received from

outside the United States. U.S. laws alone swamp our small staff.

Please check the Project Gutenberg Web pages for current donation

methods and addresses. Donations are accepted in a number of other

ways including including checks, online payments and credit card

donations. To donate, please visit: http://pglaf.org/donate

Section 5. General Information About Project Gutenberg-tm electronic

works.

Professor Michael S. Hart is the originator of the Project Gutenberg-tm

concept of a library of electronic works that could be freely shared

with anyone. For thirty years, he produced and distributed Project

Gutenberg-tm eBooks with only a loose network of volunteer support.

Project Gutenberg-tm eBooks are often created from several printed

editions, all of which are confirmed as Public Domain in the U.S.

unless a copyright notice is included. Thus, we do not necessarily

keep eBooks in compliance with any particular paper edition.

Most people start at our Web site which has the main PG search facility:

http://www.gutenberg.net

This Web site includes information about Project Gutenberg-tm,

including how to make donations to the Project Gutenberg Literary

Archive Foundation, how to help produce our new eBooks, and how to

subscribe to our email newsletter to hear about new eBooks.