The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Art of Interior Decoration, by Grace Wood This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net Title: The Art of Interior Decoration Author: Grace Wood Release Date: December 8, 2004 [EBook #14298] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE ART OF INTERIOR DECORATION *** Produced by Stan Goodman, Karen Dalrymple, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team

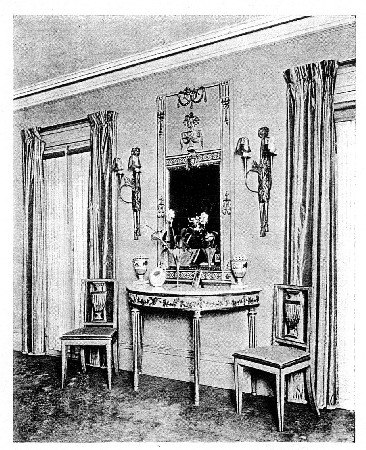

There is something unusually exquisite about this composition. You will discover at a glance perfect balance, repose—line, everywhere, yet with it infinite grace and a winning charm. One can imagine a tea tray brought in, a table placed and those two attractive chairs drawn together so that my lady and a friend may chat over the tea cups.

The mirror is an Italian Louis XVI.

The sconces, table and chairs, French.

The vases, Italian, all antiques.

A becoming mellow light comes through the shade of deep cream Italian parchment paper with Louis XVI decorations.

It should be said that the vases are Italian medicine jars—literally that. They were once used by the Italian chemists, for their drugs, and some are of astonishing workmanship and have great intrinsic value, as well as the added value of age and uniqueness.

The colour scheme is as attractive as the lines. The walls are grey, curtains of green and grey, antique taffeta being used, while the chairs have green silk on their seats and the table is of green and faded gold. The green used is a wonderfully beautiful shade.

At the age of eighty, an inspiration to all who meet her, because she is the embodiment of what this book stands for; namely, fidelity to the principles of Classic Art and watchfulness for the vital new note struck in the cause of the Beautiful.

If you would have your rooms interesting as well as beautiful, make them say something, give them a spinal column by keeping all ornamentation subservient to line.

Before you buy anything, try to imagine how you want each room to look when completed; get the picture well in your mind, as a painter would; think out the main features, for the details all depend upon these and will quickly suggest themselves. This is, in the long run, the quickest and the most economical method of furnishing.

There is a theory that no room can be created all at once, that it must grow gradually. In a sense this is a fact, so far as it refers to the amateur. The professional is always occupied with creating and recreating rooms and can instantly summon to mind complete schemes of decoration. The amateur can also learn to mentally furnish rooms. It is a fascinating pastime when one gets the knack of it.

Beautiful things can be obtained anywhere and for the minimum price, if one has a feeling for line and colour, or for either. If the lover of the beautiful was not born with this art instinct, it may be quickly acquired. A decorator creates or rearranges one room; the owner does the next, alone, or with assistance, and in a season or two has spread his or her own wings and worked out legitimate schemes, teeming with individuality. One observes, is pleased with results and asks oneself why. This is the birth of Good Taste. Next, one experiments, makes mistakes, rights them, masters a period, outgrows or wearies of it, and takes up another.

Progress is rapid and certain in this fascinating amusement,—study—call it what you will, if a few of the laws underlying all successful interior decoration are kept in mind.

These are:

HARMONY

in line and colour scheme;

SIMPLICITY

in decoration and number of objects in room, which is to be dictated by usefulness of said objects; and insistence upon

SPACES

which, like rests in music, have as much value as the objects dispersed about the room.

Treat your rooms like "still life," see to it that each group, such as a table, sofa, and one or two chairs make a "composition," suggesting comfort as well as beauty. Never have an isolated chair, unless it is placed against the wall, as part of the decorative scheme.

In preparing this book the chief aim has been clearness and brevity, the slogan of our day!

We give a broad outline of the historical periods in furnishing, with a view to quick reference work.

The thirty-two illustrations will be analysed for the practical instruction of the reader who may want to furnish a house and is in search of definite ideas as to lines of furniture, colour schemes for upholstery and hangings, and the placing of furniture and ornaments in such a way as to make the composition of rooms appear harmonious from the artist's point of view.

The index will render possible a quick reference to illustrations and explanatory text, so that the book may be a guide for those ambitious to try their hand at the art of interior decoration.

The manner of presentation is consciously didactic, the authors believing that this is the simplest method by which such a book can offer clear, terse suggestions. They have aimed at keeping "near to the bone of fact" and when the brief statements of the fundamental laws of interior decoration give way to narrative, it is with the hope of opening up vistas of personal application to embryo collectors or students of periods.

CHAPTER I HOW TO REARRANGE A ROOM

Method of procedure.—Inherited eyesores.—Line.—Colour.—Treatment of small rooms and suites.—Old ceilings.—Old floors.—To paint brass bedsteads.—Hangings.—Owning two or three antique pieces of furniture, how proceed.—Appropriateness to setting.—How to give your home a personal quality.

CHAPTER II HOW TO CREATE A ROOM

Mere comfort.—Period rooms.—Starting a collection of antique furniture.—Reproductions.—Painted furniture.—Order of procedure in creating a room.—How to decide upon colour scheme.—Study values.—Period ballroom.—A distinguished room.—Each room a stage "set."—Background.—Flowers as decoration.—Placing ornaments.—Tapestry.—Tendency to antique tempered by vivid Bakst colours.

CHAPTER III HOW TO DETERMINE CHARACTER OF HANGINGS AND FURNITURE-COVERING FOR A GIVEN ROOM

Silk, velvet, corduroy, rep, leather, use of antique silks, chintz.—When and how used.

CHAPTER IV THE STORY OF TEXTILES

Materials woven by hand and machine, embroidered, or the combination of the two known as Tapestry.—Painted tapestry.—Art fostered by the Church.—Decorated walls and ceilings, 13th century, England.

CHAPTER V CANDLESTICKS, LAMPS, FIXTURES FOR GAS AND ELECTRICITY, AND SHADES

Fixtures, as well as mantelpiece, must follow architect's scheme.—Plan wall space for furniture.—Shades for lights.—Important as to line and colour.

CHAPTER VI WINDOW SHADES AND AWNINGS

Coloured gauze sash-curtains.—Window shades of glazed linen, with design in colours.—Striped canvas awnings.

CHAPTER VII TREATMENT OF PICTURES AND PICTURE FRAMES

Selecting pictures.—Pictures as pure decoration.—"Staring" a picture.—Restraint necessary in hanging pictures.—Hanging miniatures.

CHAPTER VIII TREATMENT OF PIANO CASES

Where interest centres abound piano.—Where piano is part of ensemble.

CHAPTER IX TREATMENT OF DINING-ROOM BUFFETS AND DRESSING-TABLES

Articles placed upon them.

CHAPTER X TREATMENT OF WORK TABLES, BIRD CAGES, DOG BASKETS, AND FISH GLOBES

Value as colour notes.

CHAPTER XI TREATMENT OF FIREPLACES

Proportions, tiles, andirons, grates.

CHAPTER XII TREATMENT OF BATHROOMS

A man's bathroom.—A woman's bathroom.—Bathroom fixtures.—Bathroom glassware.

CHAPTER XIII PERIOD ROOMS

Chiselling of metals.—Ormoulu.—Chippendale.—Colonial.—Victorian.—The art of furniture making.—How to hang a mirror.—Appropriate furniture.—A home must have human quality, a personal note.—Mrs. John L. Gardner's Italian Palace in Boston.—The study of colour schemes.—Tapestries.—A narrow hall.

CHAPTER XIV PERIODS IN FURNITURE

The story of the evolution of periods.— Assyria.—Egypt.—Greece.—Rome.—France. —England.—America.—Epoch-making styles.

CHAPTER XV CONTINUATION OF PERIODS IN FURNITURE

Greece.—Rome.—Byzantium.—Dark Ages.—Middle Ages.—Gothic.—Moorish.—Spanish.—Anglo-Saxon.—Cæsar's Table.—Charlemagne's Chair.—Venice.

CHAPTER XVI THE GOTHIC PERIOD

Interior decoration of Feudal Castle.—Tapestry.—Hallmarks of Gothic oak carving.

CHAPTER XVII THE RENAISSANCE

Italy.—The Medici.—Great architects, painters, designers, and workers in metals.—Marvellous pottery.—Furniture inlaying.—Hallmarks of Renaissance.—Oak carving.—Metal work.—Renaissance in Germany and Spain.

CHAPTER XVIII FRENCH FURNITURE

Renaissance of classic period.—Francis I, Henry II, and the Louis.—Architecture, mural decoration, tapestry, furniture, wrought metals, ormoulu, silks, velvets, porcelains.

CHAPTER XIX THE PERIODS OF THE THREE LOUIS

How to distinguish them.—Louis XIV.—Louis XV.—Louis XVI.—Outline.—Decoration.—Colouring.—Mural Decoration.—Tapestry.

CHAPTER XX CHARTS SHOWING HISTORICAL EVOLUTION OF FURNITURE

French and English.

CHAPTER XXI THE MAHOGANY PERIOD

Chippendale.—Heppelwhite.—Sheraton.—The Adam Brothers.—Characteristics of these and the preceding English periods; Gothic, Elizabethan, Jacobean, William and Mary, Queen Anne.—William Morris.—Pre-Raphaelites.

CHAPTER XXIII THE COLONIAL PERIOD

Furniture.—Landscape paper.—The story of the evolution of wall decoration.

CHAPTER XXII THE REVIVAL OF DIRECTOIRE AND EMPIRE FURNITURE

Shown in modern painted furniture.

CHAPTER XXIV THE VICTORIAN PERIOD

Architecture and interior decoration become unrelated.—Machine-made furniture.—Victorian cross-stitch, beadwork, wax and linen flowers.—Bristol glass.—Value to-day as notes of variety.

CHAPTER XXV PAINTED FURNITURE

Including "mission" furniture.—Treatment of an unplastered cottage.—Furniture, colour-scheme.

CHAPTER XXVI TREATMENT OF AN INEXPENSIVE BEDROOM

Factory furniture.—Chintz.—The cheapest mirrors.—Floors.—Walls.—Pictures.—Treatment of old floors.

CHAPTER XXVII TREATMENT OF A GUEST ROOM

Where economy is not a matter of importance.—Panelled walls.—Louis XV painted furniture.—Taffeta curtains and bed-cover.—Chintz chair-covers.—Cream net sash-curtains.—Figured linen window-shades.

CHAPTER XXVIII A MODERN HOUSE IN WHICH GENUINE JACOBEAN FURNITURE Is APPROPRIATELY SET

Traditional colour-scheme of crimson and gold.

CHAPTER XXIX UNCONVENTIONAL BREAKFAST-ROOMS AND SPORTS BALCONIES

Porch-rooms.—Appropriate furnishings.—Colour schemes.

CHAPTER XXX SUN-ROOMS

Colour schemes according to climate and season.—A small, cheap, summer house converted into one of some pretentions by altering vital details.

CHAPTER XXXI TREATMENT OF A WOMAN'S DRESSING-ROOM

Solving problems of the toilet.—Shoe cabinets.—Jewel cabinets.—Dressing tables.

CHAPTER XXXII THE TREATMENT OF CLOSETS

Variety of closets.—Colour scheme.—Chintz covered boxes.

CHAPTER XXXIII TREATMENT OF A NARROW HALL

Furniture.—Device for breaking length of hall.

CHAPTER XXXIV TREATMENT OF A VERY SHADED LIVING-ROOM

In a warm climate.—In a cool climate.—Warm and cold colours.

CHAPTER XXXV SERVANTS' ROOMS

Practical and suitable attractiveness.

CHAPTER XXXVI TABLE DECORATION

Appropriateness the keynote.—Tableware.—Linen, lace, and flowers.—Japanese simplicity.—Background.

CHAPTER XXXVII WHAT TO AVOID IN INTERIOR DECORATION: RULES FOR BEGINNERS

Appropriateness.—Intelligent elimination.—Furnishings.—Colour scheme.—Small suites.—Background.—Placing rugs and hangings.—Treatment of long wall-space.—Men's rooms.—Table decoration.—Tea table.—How to train the taste, eye, and judgment.

CHAPTER XXXVIII FADS IN COLLECTING

A panier fleuri collection.—A typical experience in collecting.—A "find" in an obscure American junk-shop.—Getting on the track of some Italian pottery.—Collections used as decoration.—A "find" in Spain.

CHAPTER XXXIX WEDGWOOD POTTERY, OLD AND MODERN

The history of Wedgwood.—Josiah Wedgwood, the founder.

CHAPTER XL ITALIAN POTTERY

Statuettes.

CHAPTER XLI VENETIAN GLASS, OLD AND MODERN

Murano Museum collection.—Table-gardens in Venetian glass.

Four Fundamental Principles of Interior Decoration Re-stated.

INDEXPLATE I Portion of a Drawing-room, Perfect in Composition and Detail.

PLATE II Bedroom in Country House. Modern Painted Furniture.

PLATE III Suggestion for Treatment of a Very Small Bedroom.

PLATE IV A Man's Office in Wall Street.

PLATE V A Corner of the Same Office.

PLATE VI Another View of the Same Office.

PLATE VII Corner of a Room, Showing Painted Furniture, Antique and Modern.

PLATE VIII Example of a Perfect Mantel, Ornaments and Mirror.

PLATE IX Dining-room in Country House, Showing Modern Painted Furniture.

PLATE X Dining-room Furniture, Italian Renaissance, Antique.

PLATE XI Corner of Dining-room in New York Apartment, Showing Section of Italian Refectory Table and Italian Chairs, both Antique and Renaissance in Style.

PLATE XII An Italian Louis XVI Salon in a New York Apartment.

PLATE XIII Another Side of the Same Italian Louis XVI Salon.

PLATE XIV A Narrow Hall Where Effect of Width is Attained by Use of Tapestry with Vista.

PLATE XV Venetian Glass, Antique and Modern.

PLATE XVI Corner of a Room in a Small Empire Suite.

PLATE XVII An Example of Perfect Balance and Beauty in Mantel Arrangement.

PLATE XVIII Corner of a Drawing-room, Furniture Showing Directoire Influence.

PLATE XIX Entrance Hall in New York Duplex Apartment. Italian Furniture.

PLATE XX Combination of Studio and Living-room in New York Duplex Apartment.

PLATE XXI Part of a Victorian Parlour in One of the Few Remaining New York Victorian Mansions.

PLATE XXII Two Styles of Day-beds, Modern Painted.

PLATE XXIII Boudoir in New York Apartment. Painted Furniture, Antique and Reproductions.

PLATE XXIV Example of Lack of Balance in Mantel Arrangement.

PLATE XXV Treatment of Ground Lying Between House and Much Travelled Country Road.

PLATE XXVI An Extension Roof in New York Converted into a Balcony.

PLATE XXVII A Common-place Barn Made Interesting.

PLATE XXVIII Narrow Entrance Hall of a New York Antique Shop.

PLATE XXIX Example of a Charming Hall Spoiled by Too Pronounced a Rug.

PLATE XXX A Man's Library.

PLATE XXXI A Collection of Empire Furniture, Ornaments, and China.

PLATE XXXII Italian Reproductions in Pottery After Classic Models.

"Those who duly consider the influence of the fine-arts on the human mind, will not think it a small benefit to the world, to diffuse their productions as wide, and preserve them as long as possible. The multiplying of copies of fine work, in beautiful and durable materials, must obviously have the same effect in respect to the arts as the invention of printing has upon literature and the sciences: by their means the principal productions of both kinds will be forever preserved, and will effectually prevent the return of ignorant and barbarous ages."

JOSIAH WEDGWOOD: Catalogue of 1787.

One of the most joyful obligations in life should be the planning and executing of BEAUTIFUL HOMES, keeping ever in mind that distinction is not a matter of scale, since a vast palace may find its rival in the smallest group of rooms, provided the latter obeys the law of good line, correct proportions, harmonious colour scheme and appropriateness: a law insisting that all useful things be beautiful things.

Lucky is the man or woman of taste who has no inherited eyesores which, because of association, must not be banished! When these exist in large numbers one thing only remains to be done: look them over, see to what period the majority belong, and proceed as if you wanted a mid-Victorian, late Colonial or brass-bedstead room.

To rearrange a room successfully, begin by taking everything out of it (in reality or in your mind), then decide how you want it to look, or how, owing to what you own and must retain, you are obliged to have it look. Design and colour of wall decorations, hangings, carpets, lighting fixtures, lamps and ornaments on mantel, depend upon the character of your furniture.

It is the mantel and its arrangement of ornaments that sound the keynote upon first entering a room.

Conventional simplicity in number and arrangement of ornaments gives balance and repose, hence dignity. Dignity once established, one can afford to be individual, and introduce a riot of colours, provided they are all in the same key. Luxurious cushions, soft rugs and a hundred and one feminine touches will create atmosphere and knit together the austere scheme of line—the anatomy of your room. Colour and textiles are the flesh of interior decoration.

In furnishing a small room you can add greatly to its apparent size by using plain paper and making the woodwork the same colour, or slightly darker in tone. If you cannot find wall paper of exactly the colour and shade you wish, it is often possible to use the wrong side of a paper and produce exactly the desired effect.

In repapering old rooms with imperfect ceilings it is easy to disguise this by using a paper with a small design in the same tone. A perfectly plain ceiling paper will show every defect in the surface of the ceiling.

If your house or flat is small you can gain a great effect of space by keeping the same colour scheme throughout—that is, the same colour or related colours. To make a small hall and each of several small rooms on the same floor different in any pronounced way, is to cut up your home into a restless, unmeaning checkerboard, where one feels conscious of the walls and all limitations. The effect of restful spaciousness may be obtained by taking the same small suite and treating its walls, floors and draperies, as has been suggested, in the same colour scheme or a scheme of related keys in colour. That is, wood browns, beiges and yellows; violets, mauves and pinks; different tones of greys; different tones of yellows, greens and blues.

Now having established your suite and hall all in one key, so that there is absolutely no jarring note as one passes from room to room, you may be sure of having achieved that most desirable of all qualities in interior decoration—repose. We have seen the idea here suggested carried out in small summer homes with most successful results; the same colour used on walls and furniture, while exactly the same chintz was employed in every bedroom, opening out of one hall. By this means it was possible to give to a small, unimportant cottage, a note of distinction otherwise quite impossible. Here, however, let us say that, if the same chintz is to be used in every room, it must be neutral in colour—a chintz in which the colour scheme is, say, yellows in different tones, browns in different tones, or greens or greys. To vary the character of each room, introduce different colours in the furniture covers, the sofa-cushions and lamp-shades. Our point is to urge the repetition of a main background in a small group of rooms; but to escape monotony by planning that the accessories in each room shall strike individual notes of decorative, contrasting colour.

A room with modern painted furniture is shown here. Lines and decorations Empire.

Note the lyre backs of chairs and head board in day-bed. Treatment of this bed is that suggested where twin beds are used and room affords wall space for but one of them.

What to do with old floors is a question many of us have faced. If your house has been built with floors of wide, common boards which have become rough and separated by age, in some cases allowing dust to sift through from the cellar, and you do not wish to go to the expense of all-over carpets, you have the choice of several methods. The simplest and least expensive is to paint or stain the floors. In this case employ a floor painter and begin by removing all old paint. Paint removers come for the purpose. Then have the floors planed to make them even. Next, fill the cracks with putty. The most practical method is to stain the floors some dark colour; mahogany, walnut, weathered oak, black, green or any colour you may prefer, and then wax them. This protects the colour. In a room where daintiness is desired, and economy is not important, as for instance in a room with white painted furniture, you may have white floors and a square carpet rug of some plain dark toned velvet; or, if preferred, the painted border may be in come delicate colour to match the wall paper. To resume, if you like a dull finish, have the wax rubbed in at intervals, but if you like a glossy background for rugs, use a heavy varnish after the floors are coloured. This treatment we suggest for more or less formal rooms. In bedrooms, put down an inexpensive filling as a background for rugs, or should yours be a summer home, use straw matting.

For halls and dining-rooms a plain dark-coloured linoleum, costing not less than two dollars a yard makes and inexpensive floor covering. If it is waxed it becomes not only very durable but, also, extremely effective, suggesting the dark tiles in Italian houses. We do not advise the purchase of the linoleums which represent inlaid floors, as they are invariably unsuccessful imitations.

If it is necessary to economise and your brass bedstead must be used even though you dislike it, you can have it painted the colour of your walls. It requires a number of coats. A soft pearl grey is good. Then use a colour, or colours, in your silk or chintz bedspread. Sun-proof material in a solid colour makes an attractive cover, with a narrow fringe in several colours straight around the edges and also, forming a circle or square on the top of the bed-cover.

If your gas or electric fixtures are ugly and you cannot afford more attractive ones, buy very cheap, perfectly plain, ones and paint them to match the walls, giving decorative value to them with coloured silk shades.

Shows one end of a very small bedroom with modern painted furniture, so simple in line and decoration that it would be equally appropriate either for a young man or for a young woman. We say "young," because there is something charmingly fresh and youthful about this type of furniture.

The colour is pale pistache green, with mulberry lines, the same combination of colours being repeated in painting the walls which have a grey background lined with mulberry—the broad stripe—and a narrow green line. The bed cover is mulberry, the lamp shade is green with mulberry and grey in the fringe.

On the walls are delightful old prints framed in black glass with gold lines, and a narrow moulding of gilded oak, an old style revived.

A square of antique silk covers the night table, and the floor is polished hard wood.

Here is your hall bedroom, the wee guest room in a flat, or the extra guest room under the eaves of your country house, made equally beguiling. The result of this artistic simplicity is a restful sense of space.

If you wish to use twin beds and have not wall space for them, treat one like a couch or day-bed. See Plate II. Your cabinet-maker can remove the footboard, then draw the bed out into the room, place in a position convenient to the light either by day or night, after which put a cover of cretonne or silk over it and cushions of the same. Never put a spotted material on a spotted material. If your couch or sofa is done in a figured material of different colours, make your sofa cushions of plain material to tone down the sofa. If the sofa is a plain colour, then tone it up—make it more decorative by using cushions of several colours.

If you like your room, but find it cold in atmosphere, try deep cream gauze for sash curtains. They are wonderful atmosphere producers. The advantage of two tiers of sash curtains (see Plate IX) is that one can part and push back one tier for air, light or looking out, and still use the other tier to modify the light in the room.

Another way to produce atmosphere in a cold room is to use a tone-on-tone paper. That is, a paper striped in two depths of the same colour. In choosing any wall paper it is imperative that you try a large sample of it in the room for which it is intended, as the reflection from a nearby building or brick wall can entirely change a beautiful yellow into a thick mustard colour. How a wall paper looks in the shop is no criterion. As stated sometimes the wrong side of wall paper gives you the tone you desire.

When rearranging your room do not desecrate the few good antiques you happen to own by the use of a too modern colour scheme. Have the necessary modern pieces you have bought to supplement your treasures stained or painted in a dull, dark colour in harmony with the antiques, and then use subdued colours in the floor coverings, curtains and cushions.

If you own no good old ornaments, try to get a few good shapes and colours in inexpensive reproductions of the desired period.

If your room is small, and the bathroom opens out of it, add to the size of the room by using the same colour scheme in the bathroom, and conceal the plumbing and fixtures by a low screen. If the connecting door is kept open, the effect is to enlarge greatly the appearance of the small bedroom, whereas if the bedroom decorations are dark and the bathroom has a light floor and walls, it abruptly cuts itself off and emphasises the smallness of the bedroom.

Everything depends upon the appropriateness of the furniture to its setting. We recall some much admired dining-room chairs in the home of the Maclaines of Lochbuie in Argyleshire, west coast of Scotland. The chairs in question are covered with sealskin from the seals caught off that rugged coast. They are quite delightful in a remote country house; but they would not be tolerated in London.

The question of placing photographs is not one to be treated lightly. Remember, intimate photographs should be placed in intimate rooms, while photographs of artists and all celebrities are appropriate for the living room or library. It is extremely seldom that a photograph unless of public interest is not out of place in a formal room.

To repeat, never forget that your house or flat is your home, and, that to have any charm whatever of a personal sort, it must suggest you—not simply the taste of a professional decorator. So work with your decorator (if you prefer to employ one) by giving your personal attention to styles and colours, and selecting those most sympathetic to your own nature. Your architect will be grateful if you will show the same interest in the details of building your home, rather than assuming the attitude that you have engaged him in order to rid yourself of such bother.

If you are building a pretentious house and decide upon some clearly defined period of architecture, let us say, Georgian (English eighteenth century) we would advise keeping your first floor mainly in that period as to furniture and hangings, but upstairs let yourself go, that is, make your rooms any style you like. Go in for a gay riot of colour, such combinations as are known as Bakst colouring,—if that happens to be your fancy. This Russian painter and designer was fortunate in having the theatre in which to demonstrate his experiments in vivid colour combinations, and sometimes we quite forget that he was but one of many who have used sunset palettes.

Here we have a man's office in Wall Street, New York, showing how a lawyer with large interests surrounds himself with necessities which contribute to his comfort, sense of beauty and art instincts.

The desk is big, solid and commodious, yet artistically unusual.

Recently the fair butterfly daughters of a mother whose taste has grown sophisticated, complained—"But, Mother, we dislike periods, and here you are building a Tudor house!" forgetting, by the way, that the so-called Bakst interiors, adored by them, are equally a period.

This home, a very wonderful one, is being worked out on the plan suggested, that is, the first floor is decorated in the period of the exterior of the house, while the personal rooms on the upper floors reflect, to a certain extent, the personality of their occupants. Remember there must always be a certain relationship between all the rooms in one suite, the relationship indicated by lines and a background of the same, or a harmonising colour-scheme.

One so often hears the complaint, "I could not possibly set out alone to furnish a room! I don't know anything about periods. Why, a Louis XVI chair and an Empire chair are quite the same to me. Then the question of antiques and reproductions—why any one could mislead me!"

If you have absolutely no interest in the arranging or rearranging of your rooms, house or houses, of course, leave it to a decorator and give your attention to whatever does interest you. On the other hand, as with bridge, if you really want to play the game, you can learn it. The first rule is to determine the actual use to which you intend putting the room. Is it to be a bedroom merely, or a combination of bedroom and boudoir? Is it to be a formal reception-room, or a living-room? Is it to be a family library, or a man's study? If it is a small flat, do you aim at absolute comfort, artistically achieved, or do you aim at formality at the expense of comfort?

If you lean toward both comfort and formality, and own a country house and a city abode, there will be no difficulty in solving the problem. Formality may be left to the town house or flat, while during week-ends, holidays and summers you can revel in supreme comfort.

Every man or woman is capable of creating comfort. It is a question of those deep chairs with wide seats and backs, soft springs, thick, downy cushions, of tables and bookcases conveniently placed, lights where you want them, beds to the individual taste,—double, single, or twins!

The getting together of a period room, one period or periods in combination, is difficult, especially if you are entirely ignorant of the subject. However, here is your cue. Let us suppose you need, or want, a desk—an antique desk. Go about from one dealer to the other until you find the very piece you have dreamed of; one that gives pleasure to you, as well as to the dealer. Then take an experienced friend to look at it. If you have every reason to suppose that the desk is genuine, buy it. Next, read up on the furniture of the particular period to which your desk belongs, in as serious a manner as you do when you buy a prize dog at the show. Now you have made an intelligent beginning as a collector. Reading informs you, but you must buy old furniture to be educated on that subject. Be eternally on the lookout; the really good pieces, veritable antiques, are rare; most of them are in museums, in private collections or in the hands of the most expensive dealers. I refer to those unique pieces, many of them signed by the maker and in perfect condition because during all their existence they have been jealously preserved, often by the very family and in the very house for which they were made. Our chances for picking up antiques are reduced to pieces which on account of reversed circumstances have been turned out of house and home, and, as with human wanderers, much jolting about has told upon them. Most of these are fortified in various directions, but they are treasures all the same, and have a beauty value in line colour and workmanship and a wonderful fitness for the purposes for which they were intended.

"Surely we are many men of many minds!"

The sofa large, strong and luxuriously comfortable; the curtains simple, durable and masculine in gender. The tapestry and architectural picture, decorative and appropriately impersonal, as the wall decorations should be in a room used merely for transacting business.

Some prefer antiques a bit dilapidated; a missing detail serving as a hallmark to calm doubts; others insist upon completeness to the eye and solidity for use; while the connoisseur, with unlimited means, recognises nothing less than signed sofas and chairs, and other objets d'art. To repeat:—be always on the lookout, remembering that it is the man who knows the points of a good dog, horse or car who can pick a winner.

Wonderful reproductions are made in New York City and other cities, and thousands bought every day. They are beautiful and desirable pieces of furniture, ornaments or silks; but the lover of the vrai antique learns to detect, almost at a glance, the lack of that quality which a fine old piece has. It is not alone that the materials must be old. There is a certain quality gained from the long association of its parts. One knows when a piece has "found itself," as Kipling would put it. Time gives an inimitable finish to any surface.

If you are young in years, immature in taste, and limited as to bank account, you will doubtless go in for a frankly modern room, with cheerful painted furniture, gay or soft-toned chintzes, and inexpensive smart floor coverings. To begin this way and gradually to collect what you want, piece by piece, is to get the most amusement possible out of furnishing. When you have the essential pieces for any one room, you can undertake an ensemble. Some of the rarest collections have been got together in this way, and, if one's fortune expands instead of contracting, old pieces may be always replaced by those still more desirable, more rare, more in keeping with your original scheme.

To buy expensive furnishings in haste and without knowledge, and within a year or two discover everything to be in bad taste, is a tragedy to a person with an instinctive aversion to waste. Antique or modern, every beautiful thing bought is a cherished heirloom in embryo. Remember, we may inherit a good antique or objet d'art, buy one, or bequeath one. Let us never be guilty of the reverse,—a bar-sinister piece of furniture! Sympathy with unborn posterity should make us careful.

It is always excusable to retain an ugly, inartistic thing—if it is useful; but an ornament must be beautiful in line or in colour, or it belies its name. Practise that genuine, obvious loyalty which hides away on a safe, but invisible shelf, the bad taste of our ancestors and friends.

Having settled upon a type of furniture, turn your attention to the walls. Always let the location of your room decide the colour of its walls. The room with a sunny exposure may have any colour you like, warm or cold, but your north room or any room more or less sunless, requires the warm, sun-producing yellows, pinks, apple-greens, beige and wood-colours, never the cold colours, such as greys, mauves, violets and blues, unless in combination with the warm tones. If it is your intention to hang pictures on the walls, use plain papers. Remember you must never put a spot on a spot! The colour of your walls once established, keep in mind two things: that to be agreeable to the artistic eye your ceilings must be lighter than your sidewalls, and your floors darker. Broadly speaking, it is Nature's own arrangement, green trees and hillsides, the sky above, and the dark earth beneath our feet. A ceiling, if lighter in tone than the walls, gives a sense of airiness to a room. Floors, whether of exposed wood, completely carpeted, or covered by rugs, must be enough darker than your sidewalls to "hold down your room," as the decorators say.

If colour is to play a conspicuous part, brightly figured silks and cretonnes being used for hangings and upholstery, the floor covering should be indefinite both as to colour and design. On the other hand, when rugs or carpets are of a definite design in pronounced colours, particularly if you are arranging a living-room, make your walls, draperies and chair-covers plain, and observe great restraint in the use of colour. Those who work with them know that there is no such thing as an ugly colour, for all colours are beautiful. Whether a colour makes a beautiful or an ugly effect depends entirely upon its juxtaposition to other tones. How well French milliners and dressmakers understand this! To make the point quite clear, let us take magenta. Used alone, nothing has more style, more beautiful distinction, but in wrong combination magenta can be amazingly, depressingly ugly. Magenta with blue is ravishing, beautiful in the subtle way old tapestries are: it touches the imagination whenever that combination is found.

The table is modern, but made on the lines of a refectory table, well suited in length, width and solidity for board meetings, etc.

The chairs are Italian in style.

We grow up to, into, and out of colour schemes. Each of the Seven Ages of Man has its appropriate setting in colour as in line. One learns the dexterous manipulation of colour from furnishing, as an artist learns from painting.

Refuse to accept a colour scheme, unless it appeals to your individual taste—no matter who suggests it. To one not very sensitive to colour here is a valuable suggestion. Find a bit of beautiful old silk brocade, or a cretonne you especially like, and use its colour combinations for your room—a usual device of decorators. Let us suppose your silk or cretonne to have a deep-cream background, and scattered on it green foliage, faded salmon-pink roses and little, fine blue flowers. Use its prevailing colour, the deep cream, for walls and possibly woodwork; make the draperies of taffeta or rep in soft apple-greens; use the same colour for upholstery, make shades for lamp and electric lights of salmon-pink, then bring in a touch of blue in a sofa cushion, a footstool or small chair, or in a beautiful vase which charms by its shape as well by reproducing the exact tone of blue you desire. There are some who insist no room is complete without its note of blue. Many a room has been built up around some highly prized treasure,—lovely vase or an old Japanese print.

A thing always to be avoided is monotony in colour. Who can not recall barren rooms, without a spark of attraction despite priceless treasures, dispersed in a meaningless way? That sort of setting puts a blight on any gathering. "Well," you will ask, "given the task of converting such a sterile stretch of monotony into a blooming joy, how should one begin?" It is quite simple. Picture to yourself how the room would look if you scattered flowers about it, roses, tulips, mignonette, flowers of yellow and blue, in the pell-mell confusion of a blooming garden. Now imitate the flower colours by objets d'art so judiciously placed that in a trice you will admire what you once found cold. As if by magic, a white, cream, beige or grey room may be transformed into a smiling bower, teeming with personality, a room where wit and wisdom are spontaneously let loose.

If your taste be for chintzes and figured silks, take it as a safe rule, that given a material with a light background, it should be the same in tone as your walls; the idea being that by this method you get the full decorative value of the pattern on chintz or silk.

Figured materials can increase or diminish the size of a room, open up vistas, push back your walls, or block the vision. For this reason it is unsafe to buy material before trying the effect of it in its destined abode.

Remember that the matter of background is of the greatest importance when arranging your furniture and ornaments. See that your piano is so placed that the pianist has an unbroken background, of wall, tapestry, a large piece of rare old sills, or a mirror. Clyde Fitch, past-master at interior decoration, placed his piano in front of broad windows, across which at night were drawn crimson damask curtains. Some of us will never forget Geraldine Farrar, as she sat against that background wearing a dull, clinging blue-green gown, going over the score,—from memory,—of "Salomé."

The aim is to make the performer at the piano the object of interest, therefore place no diverting objects, such as pictures or ornaments, on a line with the listener's eye, except as a vague background.

There can be no more becoming setting for a group of people dining by candle or electric light, than walls panelled with dark wood to the ceiling, or a high wainscoting.

A beautiful sitting-room, not to be forgotten, had light violet walls, dull-gold frames on the furniture which was covered in deep-cream brocades, bits of old purple velvets and violet silks on the tables, under large bowls of Benares bronze filled with violets. The grand piano was protected by a piece of old brocade in faded yellows, and our hostess, a well-known singer, usually wore a simple Florentine tea-gown of soft violet velvet, which together with the lighter violet walls, set off her fair skin and black hair to beautiful advantage.

Put a figured, many-coloured sofa cushion behind the head of a pretty woman, and if the dominating colour is becoming to her, she is still pretty, but change it to a solid black, purple or dull-gold and see how instantly the degree of her beauty is enhanced by being thrown into relief.

Gives attractive corner by a window, the heavy silk brocade curtains of which are drawn. A standard electric lamp lights the desk, both modern-painted pieces, and the beautiful old flower picture, black background with a profusion of colours in lovely soft tones, is framed by a dull-gold moulding and gives immense distinction. The chair is Venetian Louis XV, the same period as desk in style.

Not to be ignored in this picture is a tin scrap basket beautifully proportioned and painted a vivid emerald green; a valuable addition a note of cheerful colour. The desk and wooden standard of lamp are painted a deep blue-plum colour, touched with gold, and the silk curtains are soft mulberry, in two tones.

Study values—just why and how much any decorative article decorates, and remember in furnishing a room, decorating a wall or dining-room table, it is not the intrinsic value or individual beauty of any one article which counts. Each picture on the wall, each piece of furniture, each bit of silver, glass, china, linen or lace, each yard of chintz or silk, every carpet or rug must be beautiful and effective in relation to the others used, for the art of interior decoration lies in this subtle, or obvious, relationship of furnishings.

We acknowledge as legitimate all schemes of interior decoration and insist that what makes any scheme good or bad, successful, or unsuccessful presuming a knowledge of the fundamentals of the art, is the fact that it is planned in reference to the type of man or woman who is to live in it.

A new note has been struck of late in the arranging of bizarre, delightful rooms which on entering we pronounce "very amusing."

Original they certainly are, in colour combinations, tropical in the impression they make,—or should we say Oriental?

They have come to us via Russia, Bakst, Munich and Martine of Paris. Like Rheinhardt's staging of "Sumurun," because these blazing interiors strike us at an unaccustomed angle, some are merely astonished, others charmed as well. There are temperaments ideally set in these interiors, and there are houses where they are in place. We cannot regard them as epoch-making, but granted that there is no attempt to conform to two of the rules for furnishing,—appropriateness and practicality, the results are refreshingly new and entertaining. This is one of the instances where exaggeration has served as a healthy antidote to the tendency toward extreme dinginess rampant about ten years ago, resulting from an obsession to antique everything. The reaction from this, a flaming rainbow of colours, struck a blow to the artistic sense, drew attention back to the value of colour and started the creative impulse along the line of a happy medium.

Whether it be a furnished porch, personal suite (as bedroom, boudoir and bath), a family living-room, dining-room, formal reception-room, or period ballroom, never allow members of your household or servants to destroy the effect you have achieved with careful thought and outlay of money, by ruthlessly moving chairs and tables from one room to another. Keep your wicker furniture on the porch, for which it was intended. If it strays into the adjacent living-room, done in quite another scheme, it will absolutely thwart your efforts at harmony, while your porch-room done in wicker and gay chintzes, striped awnings and geranium rail-boxes, cries out against the intrusion of a chair dragged out from the house. Remember that should you intend using your period ballroom from time to time as an audience room for concerts and lectures, you must provide a complete equipment of small, very light (so as to be quickly moved) chairs, in your "period," as a necessary part of your decoration.

The current idea that a distinguished room remains distinguished because costly tapestries and old masters hang on its walls, even when the floor is strewn with vulgar, hired chairs, is an absurd mistake. Each room from kitchen to ballroom is a stage "set,"—a harmonious background for certain scenes in life's drama. It is the man or woman who grasps this principle of a distinguished home who can create an interior which endures, one which will hold its own despite the ebb and flow of fashion. Imposing dimensions and great outlay of money do not necessarily imply distinction, a quality depending upon unerring good taste in the minutest details, one which may be achieved equally in a stately mansion, in a city flat, or in a cottage by the sea.

The question of background is absorbingly interesting. A vase, with or without flowers, to add to the composition of your room, that is, to make "a good picture," must be placed so that its background sets it off. Let the Venetian glass vase holding one rose stand in such a position that your green curtain is its background, and not a photograph or other picture. One flower, carefully placed in a room, will have more real decorative value than dozens of costly roses strewn about in the wrong vases, against mottled, line-destroying backgrounds.

Flowers are always more beautiful in a plain vase, whether of glass, pottery, porcelain or silver. If a vase chances to have a decoration in colour, then make a point of having the flowers it holds accord in colour, if not in shade, with the colour or colours in the vase.

There is a general rule that no ornament should ever be placed in front of a picture. The exception to this rule occurs when the picture is one of the large, architectural variety, whose purpose is primarily mural decoration,—an intentional background, as tapestries often are, serving its purpose as nature does when a vase or statue is placed in a park or garden. One sees in portraits by some of the old masters this idea of landscape used as background. Bear in mind, however, that if there is a central design—a definite composition in the picture, or tapestry, no ornament should ever be so placed as to interfere with it. If you happen to own a tapestry which is not large enough for your space by one, two or three feet, frame it with a plain border of velvet or velveteen, to match the dominating colour, and a shade darker than it appears in the tapestry. This expedient heightens the decorative effect of the tapestry.

In a measure, the materials for hangings and furniture-coverings are determined more or less by the amount one wishes to spend in this direction. For choice, one would say silk or velvet for formal rooms; velvets, corduroys or chintz for living-rooms; leather and corduroy with rep hangings for a man's study or smoking-room; thin silks and chintz for bedrooms; chintz for nurseries, breakfast-rooms and porches.

In England, slip-covers of chintz (glazed cretonne) appear, also, in formal rooms; but are removed when the owner is entertaining. If the permanent upholstery is of chintz, then at once your room becomes informal. If you are planning the living-room for a small house or apartment, which must serve as reception-room during the winter months, far more dignity, and some elegance can be obtained for the same expenditure, by using plain velveteen, modern silk brocades in one colour, or some of the modern reps to be had in very smart shades of all colours.

If your furniture is choice, rarely beautiful in quality, line and colour, hangings and covers must accord. Genuine antiques demand antique silks for hangings and table covers; but no decorator, if at all practical, will cover a chair or sofa in the frail old silks, for they go to pieces almost in the mounting. Waive sentiment in this case, for the modern reproductions are satisfactory to the eye and improve in tone with age.

If you own only a small piece of antique silk, make a square of it for the centre of the table, or cleverly combine several small bits, if these are all you have, into an interesting cover or cushion. Nothing in the world gives such a note of distinction to a room as the use of rare, old silks, properly placed.

The fashion for cretonne and chintz has led to their indiscriminate use by professionals as well as amateurs, and this craze has caused a prejudice against them. Chintz used with judgment can be most attractive. In America the term chintz includes cretonne and stamped linen. If you are planning for them, put together, for consideration, all your bright coloured chintz, and in quite another part of your room, or decorator's shop, the chintz of dull, faded colours, as they require different treatment. A general rule for this material—bright or dull—is that if you would have your chintz decorate, be careful not to use it too lavishly. If it is intended for curtains, then cover only one chair with it and cover the rest in a solid colour. If you want chintz for all of your chairs and sofa, make your curtains, sofa cushions and lamp shades of a solid colour, and be sure that you take one of the leading colours in the chintz. Next indicate your intention at harmony, by "bringing together" the plain curtains or chairs, and your chintz, with a narrow fringe or border of still another colour, which figures in the chintz. Let us suppose chintz to be black with a design in greens, mulberry and buff. Make your curtains plain mulberry, edged with narrow pale green fringe with black and buff in it, or should your chintz be grey with a design in faded blues and violets and a touch of black, make curtains of the chintz, and cover one large chair, keeping the sofa and the remaining chairs grey, with the bordering fringe, or gimp, in one or two of the other shades, sofa cushions and the lamp shades in blues and violets (lining lamp shades with thin pink silk), and use a little black in the bordering fringe.

Shows an ideal mantel arrangement, faultless as a composition and beautiful and rare in detail. The exquisite white marble mantel is Italian, not French, of the time of Louis XVI.

Though the designs of this period are almost identical, one quickly learns to detect the difference in feeling between the work of the two countries. The Italians are freer, broader in their treatment, show more movement and in a way more grace, where the French work is more detailed and precise, hence at times, by contrast, seems stilted and rigid.

Enchantingly graceful are the two candelabra, also Louis XVI, while the central ornament is ideally chosen for size and design.

The dull gold frame of the mirror is very beautiful, and the painting above the glass interesting and unusual as to subject and execution.

The chair is a good example of Italian Louis XV.

If you decide upon a very brilliant chintz use it only in one chair, a screen, or in a valance over plain curtains with straps to hold them back, or perhaps a sofa cushion. Whether a chintz is bright or dull, its pattern is important. As with silks, brocaded in different colours, therefore never use chintz where a chair or sofa calls for tufting. A tufted piece of furniture always looks best done in plain materials.

In using a chintz in which both colour and design are indefinite, the kind which gives more or less an impression of faded tapestry, you will find that the very indefiniteness of the pattern makes it possible to use the chintz with more freedom, being always sure of a harmonious background. The one thing to guard against is that on entering a room you must not be conscious either of several colours, or of any set design.

The story of the evolution of textiles (any woven material) is fascinating, and like the history of every art, runs parallel with the history of culture and progress in the art of living,—physical, mental and spiritual.

To those who feel they would enjoy an exhaustive history of textiles we recommend a descriptive catalogue relating to the collection of textiles in the South Kensington Museum, prepared by the Very Rev. Daniel Rock, D.D. (1870).

In the introduction to that catalogue one gets the story of woven linens, cottons, silks, paper, gold and silver threads, interspersed with precious jewels and glass beads—all materials woven by hand or machine.

The story of textiles includes: 1st, woven materials; 2nd, embroidered materials; 3rd, a combination of the two, known as "tapestry." If one reads their wonderful story, starting in Assyria, then progressing to Egypt, the Orient, Greece, Rome and Western Europe, in any history of textiles, one may obtain quickly and easily a clear idea of this department of interior decoration from the very earliest times.

The first European silk is said to have been in the form of transparent gauze, dyed lovely tones for women of the Greek islands, a form of costume later condemned by Greek philosophers.

We know that embroidery was an art three thousand years ago, in fact the figured garments seen on the Assyrian and Egyptian bas-reliefs are supposed to represent materials with embroidered figures—not woven patterns—whereas in the Bible, when we read of embroidery, according to the translators, this sometimes means woven stripes.

An ideal dining-room of its kind, modern painted furniture, Empire in design. In this case yellow with decoration in white. Curtains, thin yellow silk.

Note the Empire electric light fixtures in hand-carved gilded wood, reproductions of an antique silver applique. Even the steam radiators are here cleverly concealed by wooden cases made after Empire designs.

The walls are white and panelled in wood also white.

The earliest garments of Egypt were of cotton and hemp, or mallow, resembling flax. The older Egyptians never knew silks in any form, nor did the Israelites, nor any of the ancients. The earliest account of this material is given by Aristotle (fourth century). It was brought into Western Europe from China, via India, the Red Sea and Persia, and the first to weave it outside the Orient was a maiden on the Isle of Cos, off the coast of Asia Minor, producing a thin gauze-like tissue worn by herself and companions, the material resembling the Seven Veils of Salome. To-day those tiny bits of gauze one sees laid in between the leaves of old manuscript to protect the illuminations, as our publishers use sheets of tissue paper, are said to be examples of this earliest form of woven silk.

The Romans used silk at first only for their women, as it was considered not a masculine material, but gradually they adopted it for the festival robes of men, Titus and Vespasian being among those said to have worn it.

The first silk looms were set up in the royal palaces of the Roman kings in the year 533 A.D. The raw material was brought from the East for a long time but in the sixth century two Greek monks, while in China, studied the method of rearing silk worms and obtaining the silk, and on their departure are said to have concealed the eggs of silk worms in their staves. They are accredited with introducing the manufacture of silk into Greece and hence into Western Europe. After that Greece, Persia and Asia Minor made this material, and Byzantium was famed for its silks, the actual making of which got into the hands of the Jews and was for a long time controlled by them.

Metals (gold, silver and copper) were flattened out and cut into narrow strips for winding around cotton twists. These were the gold and silver threads used in weaving. The Moors and Spaniards instead of metals used strips of gilded parchment for weaving with the silk.

We know that England was weaving silk in the thirteenth century, and velvets seem to have been used at a very early date. The introduction of silk and velvet into different countries had an immediate and much-needed influence in civilising the manners of society. It is hard to realise that in the thirteenth century when Edward I married Eleanor of Castile, the highest nobles of England when resting at their ease, stretched at full length on the straw-covered floors of baronial halls, and jeered at the Spanish courtiers who hung the walls and stretched the floors of Edward's castle with silks in preparation for his Spanish bride.

The progress of art and culture was always from the East and moved slowly. Do not go so far back as the thirteenth century. James I of England owned no stockings when he was James VI of Scotland, and had to borrow a pair in which to receive the English ambassador.

In the eleventh century Italy manufactured her own silks, and into them were woven precious stones, corals, seed pearls and coloured glass beads which were made in Greece and Venice, as well as gold and silver spangles (twelfth and thirteenth centuries).

Here is an item on interior decorations from Proverbs vii, 16; "I have woven my bed with cords, I have covered it with painted tapestry brought from Egypt." There were painted tapestries made in Western Europe at a very early date, and collectors eagerly seek them (see Plate XIV). In the fourteenth century these painted tapestries were referred to as "Stained Cloth."

Embroidery as an art, as we have already seen, antedates silk weaving. The youngest of the three arts is tapestry. The oldest embroidery stitches are: "the feather stitch," so called because they all took one direction, the stitches over-lapping, like the feathers of a bird; and "cross-stitch" or "cushion" style, because used on church cushions, made for kneeling when at prayer or to hold the Mass book.

Hand-woven tapestries are called "comb-wrought" because the instrument used in weaving was comb-like.

"Cut-work" is embroidery that is cut out and appliqued, or sewed on another material.

Carpets which were used in Western Europe in the Middle Ages are seldom seen. The Kensington Museum owns two specimens, both of them Spanish, one of the fourteenth and one of the fifteenth century.

In speaking of Gothic art we called attention to the fostering of art by the Church during the Dark Ages. This continued, and we find that in Henry VIII's time those who visited monasteries and afterward wrote accounts of them call attention to the fact that each monk was occupied either with painting, carving, modelling, embroidering or writing. They worked primarily for the Church, decorating it for the glory of God, but the homes of the rich and powerful laity, even so early as the reign of Henry III (1216-1272), boasted some very beautiful interior decorations, tapestries, painted ceilings and stained glass, as well as carved panelling.

Bostwick Castle, Scotland, had its vaulted ceiling painted with towers, battlements and pinnacles, a style of mural decoration which one sees in the oldest castles of Germany. It recalls the illumination in old manuscripts.

Candlesticks, lamps, and fixtures for gas and electricity must accord with the lines of your architecture and furniture. The mantelpiece is the connecting link between the architecture and the furnishing of a room. It is the architect's contribution to the furnishing, and for this reason the keynote for the decorator.

In the same way lighting fixtures are links between the construction and decoration of a room, and can contribute to, or seriously divert from, the decorator's design.

It is important that fixtures be so placed as to appear a part of the decoration and not merely to illuminate conveniently a corner of the room, a writing-desk, table or piano.

The dining-room of this apartment is Italian Renaissance—oak, almost black from age, and carved.

The seat pads and lambrequin over window are of deep red velvet. The walls are stretched with dull red brocotello (a combination of silk and linen), very old and valuable. The chandelier is Italian carved wood, gilded.

Attention is called to the treatment of the windows. No curtains are used, instead, boxes are planted with ivy which is trained to climb the green lattice and helps to temper the light, while the window shades themselves are of a fascinating glazed linen, having a soft yellow background and design of fruit and vines in brilliant colours.

In planning your house after arranging for proper wall space for your various articles of furniture, keep in mind always that lights will be needed and must be at the same time conveniently placed and distinctly decorative.

One is astonished to see how often the actual balance of a room is upset by the careless placing of electric fixtures. Therefore keep in mind when deciding upon the lighting of a room the following points: first, fixtures must follow in line style of architecture and furniture; second, the position of fixtures on walls must carry out the architect's scheme of proportion, line and balance; third, the material used in fixtures—brass, gilded wood, glass or wrought iron—must contribute to the decorator's scheme of line and colour; fourth, as a contribution to colour scheme the fixtures must be in harmony with the colour of the side walls, so as not to cut them up, and the shade should be a light note of colour, not one of the dark notes when illuminated.

This brings us to the question of shades. The selecting of shapes and colours for shading the lights in your rooms is of the greatest importance, for the shades are one of the harmonics for striking important colour notes, and their value must be equal by day and by night; that is, equally great, even if different. Some shades, beautiful and decorative by daylight, when illuminated, lose their colour and become meaningless blots in a room. We have in mind a large silk lamp shade of faded sage green, mauve, faun and a dull blue, the same combination appearing in the fringe—a combination not only beautiful, but harmonising perfectly with the old Gothic tapestry on the nearby wall. Nothing could be more decorative in this particular room during the day than the shade described; but were it not for the shell-pink lining, gleaming through the silk of the shade when lighted, it would have no decorative value at all at night.

In ordering or making shades, be sure that you select colours and materials which produce a diffused light. A soft thin pink silk as a lining for a silk or cretonne shade is always successful, and if a delicate pink, never clashes with the colours on the outside. A white silk lining is cold and unbecoming. A dark shade unlined, or a light coloured shade unlined, even if pink, unless the silk is shirred very full, will not give a diffused, yellow light.

It is because Italian parchment-paper produces the desired glow of light that it has become so popular for making shades, and, coming as it does in deep soft cream, it gives a lovely background for decorations which in line and colour can carry out the style of your room.

Figured Italian papers are equally popular for shades, but their characteristic is to decorate the room by daylight only, and to impart no quality to the light which they shade. Unless in pale colours, they stop the light, absolutely, throwing it down, if on a lamp, and back against the wall, if on side brackets. Therefore decorators now cut out the lovely designs on these figured papers and use them as appliques on a deep cream parchment background.

When you decide upon the shape of your shades do not forget that successful results depend upon absolutely correct proportions. Almost any shape, if well proportioned as to height and width, can be made beautiful, and the variety and effect desired, may be secured by varying the colours, the design of decoration, if any, or the texture or the length of fringe.

The "umbrella" shades with long chiffon curtains reaching to the table, not unlike a woman's hat with loose-hanging veil, make a charming and practical lamp shade for a boudoir or a woman's summer sitting-room, especially if furnished in lacquer or wicker. It is a light to rest or talk by, not for reading nor writing.

The greatest care is required in selecting shades for side-wall lights, because they quickly catch the eye upon entering a room and materially contribute to its appearance or detract from it.

The first thing to consider in selecting window shades when furnishing a house, is whether their colour harmonises with the exterior. Keeping this point in mind, further limit your selection to those colours and tones which harmonise with your colour schemes for the interior. If you use white net or scrim, your shades must be white, and if ecru net, your shades must be ecru. If the outside of your house calls for one colour in shades and the interior calls for another, use two sets. Your dark-green sun shades never interfere, as they can always be covered by the inner set. Sometimes the dark green harmonises with the colouring of the rooms.

A room often needs, for sake of balance, to be weighted by colour on the window sides more than your heavy curtains (silk or cretonne) contribute when drawn back; in such a case decorators use coloured gauze for sash curtains in one, two or three shades and layers, which are so filmy and delicate both in texture and colouring that they allow air and light to pass through them, the effect being charming.

Another way to obtain the required colour value at your windows is the revival of glazed linens, with beautiful coloured designs, made up into shades. These are very attractive in a sunny room where the strong light brings out the design of flowers, fruits or foliage. Plate X shows a room in which this style of shade is used with great success. It is to be especially commended in such a case as Plate X, where no curtains are used at windows. Here the figured linen shade is a deliberate contribution to the decorative scheme of the room and completes it as no other material could.

Awnings can make or mar a house, give it style or keep it in the class of the commonplace. So choose carefully with reference to the colour of your house. The fact that awnings show up at a great distance and never "in the hand," as it were, argues in favour of clear stripes, in two colours and of even size, with as few extra threads of other colours as possible.

Shows a part of a fine, old Italian refectory table, and one of the chairs, also antiques, which are beautifully proportioned and made comfortable with cushions of dark red velvet, in colour like curtains at window, which are of silk brocade.

The standard electric lamps throw the light up only. There are four, one in each corner of the room, and candles light the table.

The wall decoration here is a flower picture.

All awnings fade, even in one season; green is, perhaps, the least durable in the sun, yellows and browns look well the longest. Fortunately an awning, a discouraging sight when taken down and in a collapsed mass of faded canvas, will often look well when up and stretched, because the strong light brings out the fresh colour of the inside. Hence one finds these rather expensive necessities of summer homes may be used for several seasons.

Strive to have the subject of your pictures appropriate to the room in which they are to be hung.

It is impossible to state a rule for this, however, because while there are many styles of pictures which all are able to classify, such as old paintings which are antique in colouring, method and subject, portraits, figure pictures, architectural pictures, flower and fruit pictures, modern oil paintings of various subjects (modern in subject, method and colouring), water colours, etchings, sporting prints, fashion prints, etc., there is, also, a subtle relationship between them seen and felt only by the connoisseur, which leads him to hang in the same room, portraits, architectural pictures and flower pictures, with beautiful and successful results. Often the relationship hangs on similarity in period, style of painting or colour scheme. Your expert will see decorative value in a painting which has no individual beauty nor intrinsic worth when taken out of a particular setting.

The selecting of pictures for a room hinges first on their decorative value. That is, their colour and size, and whether the subjects are appropriate and sympathetic.

Always avoid heavy gold frames on paintings, for, unless they are real objects of art, one gets far more distinction by using a narrow black moulding. When in doubt always err on the side of simplicity.

If your object is economy as well as simplicity, and you are by chance just beginning to furnish your house and own no pictures, we would suggest good photographs of your favourite old masters, framed close, without a margin, in the passepartout method (glass with a narrow black paper tape binding).

Old coloured prints need narrow black passepartout, while broad passepartout in pink, blue or pale green to match the leading tone in wall paper makes your quaint, old black-and-white prints very decorative.

Never use white margins on any pictures unless your walls are white.

The decorative value of any picture when hung, is dependent upon its background, the height at which it is hung, its position with regard to the light, its juxtaposition to other pictures, and the character of those other pictures—that is, their subjects, colour and line.

If you are buying pictures to hang in a picture gallery, there is nothing to consider beyond the attraction of the individual picture in mind. But if you are buying a picture to hang on the walls of a room which you are furnishing, you have first to consider it as pure decoration; that is, to ask yourself if in colour, period and subject it carries out the idea of your room.

A modern picture is usually out of place in a room furnished with antiques. In the same way a strictly modern room is not a good setting for an old picture, if toned by time.

If you own or would own a modern portrait or landscape and it is the work of an artist, and beautiful in colour, why not "star" it,—build your room up to it? If you decide to do this, see that everything else representing colour is either subservient to the picture, or if of equal value as to colour, that they harmonise perfectly with the picture in mind.

From a studio one enters a smaller room, one side of which is shown here, a veritable Italian Louis XVI salon.

We were recently shown a painting giving a view of Central Park from the Plaza Hotel, New York, under a heavy fall of snow, in the late afternoon, when the daylight still lingered, although the electric lights had begun to spangle the scene. The prevailing tone was a delicate, opalescent white, shading from blue to mauve, and we were told that one of our leading decorators intended to hang it in a blue room which he was furnishing for a New York client.

Etchings are at their best with other etchings, engravings or water colours, and should be hung in rooms flooded with light and delicately furnished.

The crowding of walls with pictures is always bad; hang only as many as furnish the walls, and have these on a line with the eye and when the pictures vary but slightly in size make a point of having either the tops of the frames or the bottoms on the same line,—that is, an equal distance from floor or ceiling. If this rule is observed a sense of order and restfulness is communicated to the observer.

If one picture is hung over the other uniformity and balance must be preserved.

One large picture may be balanced by two smaller ones.

Hang your miniatures in a straight line across your wall, under a large picture or in a straight line—one under the other, down a narrow wall panel.

A professional pianist invariably prefers the case of his or her piano left in its simple ebony or mahogany, and would not approve of its being relegated to the furniture department and decorated accordingly, any more than your violinist, or harpist, would hand over his violin, or harp, for decoration.

When a piano, however, is not the centre of interest in a house, and the artistic ensemble of decorative line and colour is, the piano case is often ordered at the piano factory to be made to accord in line with the period of the room for which it is intended, after which it is decorated so as to harmonise with the colours in the room. This can be done through the piano factory; but in the case of redecorating a room, one can easily get some independent artist to do this work, a man who has made a study of the decorations on old spinets in palaces, private mansions and museums. Some artists have been very successful in converting what was an inartistic piece of furniture as to size, outline and colour, into an object which became a pleasing portion of the colour scheme because in proper relation to the whole.

You can always make an ebony or mahogany piano case more in harmony with its setting by covering it, when not in use, with a piece of beautiful old brocade, or a modern reproduction.

Another side of same Italian Louis XVI salon. The tea-table is a modern painted convenience, the two vases are Italian pharmacy jars and the standard for electric lights is a modern-painted piece.

A dining-room buffet requires the same dignity of treatment demanded by a mantelpiece whether the silver articles kept on it be of great or small intrinsic value. Here, as in every case, appropriateness dictates the variety of articles, and the observance of the rule that there shall be no crowding nor disorder in the placing of articles insures that they contribute decorative value; in a word, the size of your buffet limits the amount of silver, glass, etc., to be placed upon it.

The variety and number of articles on a dressing-table are subject to the same two laws: that is, every article must be useful and in line and colour accord with the deliberate scheme of your room, and there must be no crowding nor disorder, no matter how rare or beautiful the toilet articles are.

Every bedroom planned for a woman, young or old, calls for a work table, work basket or work bag, or all three, and these furnish opportunities for additional "flowers" in your room; for we insist upon regarding accessories as opportunities for extra colour notes which harmonise with the main colour scheme and enliven your interior quite as flowers would, cheering it up—and, incidentally, its inmates! Apropos of this, it was only the other day that some one remarked in our hearing, "This room is so blooming with lovely bits of colour in lamp shades, pillows, and objets d'art, that I no longer spend money on cut flowers." There we have it! Precisely the idea we are trying to express. So make your work-table, if you own the sort with a silk work-bag suspended from the lower part, your work-basket or work-bag, represent one, two or three of the colours in your room.

If some one gives you an inharmonious work-bag, either build a room up to it, or give it away, but never hang it out in a room done in an altogether different colour scheme.

Bird-cages, dog-baskets and fish-globes may become harmonious instead of jarring colour notes, if one will give a little thought to the matter. In fact some of the black iron wrought cages when occupied by a wonderful parrot with feathers of blue and orange, red and grey, or red, blue and yellow, can be the making of certain rooms. And there are canaries with deep orange feathers which look most decorative in cages painted dark green, as well as the many-coloured paroquet, lovely behind golden bars.

Many a woman when selecting a dog has bought one which harmonised with her costume, or got a costume to set off her dog! Certainly a dark or light brindle bull is a perfect addition to a room done in browns, as is a red Chow or a tortoise-shell cat.

See to it that cage and basket set off your bird, dog or cat; but don't let them become too conspicuous notes of colour in your room or on your porch; let it be the bird, the dog or the cat which has a colour value.

The fish-globe can be of white or any colour glass you prefer, and your fish vivid or pale in tone; whichever it is, be sure that they furnish a needed—not a superfluous—tone of colour in a room or on a porch.

Shows narrow hall in an old country house, thought impossible as to appearance, but made charming by "pushing out" the wall with an antique painted tapestry and keeping all woodwork and carpets the same delicate dove grey.

Nothing is ever more attractive than the big open fireplace, piled with blazing logs, and with fire-dogs or andirons of brass or black iron, as may accord with the character of your room. If yours is a period room it is possible to get andirons to match, veritable old ones, by paying for them. The attractiveness of a fireplace depends largely upon its proportions. To look well it should always be wider than high, and deep enough to insure that the smoke goes up the chimney, and not out into your room. If your fireplace smokes you may need a special flue, leading from fireplace to proper chimney top, or a brass hood put on front of the fireplace.

Many otherwise attractive fireplaces are spoiled by using the wrong kind of tiles to frame them. Shiny, enamelled tiles in any colour, are bad, and pressed red brick of the usual sort equally bad, so if you are planning the fireplace of an informal room, choose tiles with a dull finish or brick with a simple rough finish. In period rooms often beautiful light or heavy mouldings entirely frame the three sides of the fireplace when it is of wood. Well designed marble mantels are always desirable. This feature of decoration is distinctly within the province of your architect, one reason more why he and the interior decorator, whether professional or amateur, should continually confer while building or rebuilding a house.