The Project Gutenberg EBook of Mavericks, by William MacLeod Raine This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net Title: Mavericks Author: William MacLeod Raine Release Date: December 29, 2004 [EBook #14520] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK MAVERICKS *** Produced by Kathryn Lybarger and the PG Online Distributed Proofreading Team

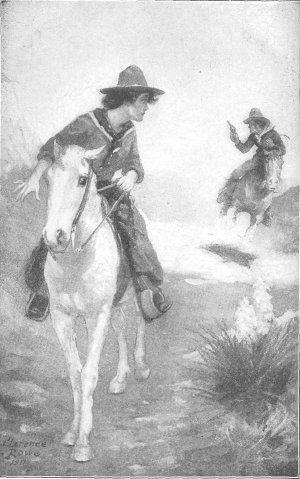

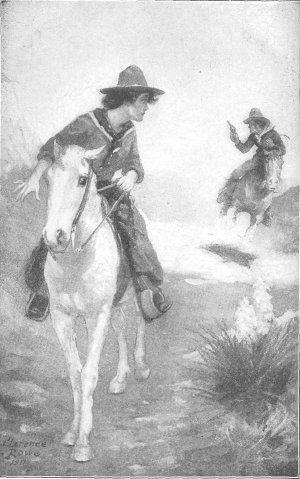

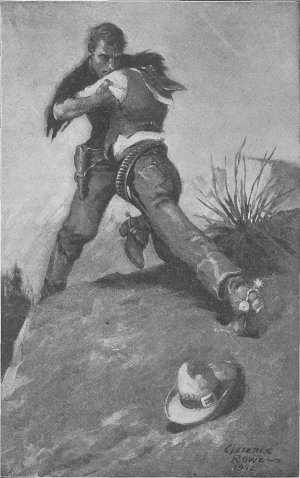

THE RIDER SLEWED IN THE SADDLE WITH HIS WHOLE ATTENTION UPON POSSIBLE PURSUIT. (Page 33)

|

"In vain men tell us time can alter Old loves, or make old memories falter." |

Phyllis leaned against the door-jamb and looked down the long road which wound up from the valley and lost itself now and again in the land waves. Miles away she could see a little cloud of dust travelling behind the microscopic stage, which moved toward her almost as imperceptibly as the minute-hand of a clock. A bronco was descending the hill trail from the Flagstaff mine, and its rider announced his coming with song in a voice young and glad.

floated the words to her across the sunlit open.

If the girl heard, she heeded not. One might have guessed her a sullen, silent lass, and would have done her less than justice. For the storm in her eyes and the curl of the lip were born of a mood and not of habit. They had to do with the gay vocalist who drew his horse up in front of her and relaxed into the easy droop of the experienced rider at rest.

"Don't see me, do you?" he asked, smiling.

Her dark, level gaze came round and met his sunniness without response.

"Yes, I see you, Tom Dixon."

"And you don't think you see much then?" he suggested lightly.

She gave him no other answer than the one he found in the rigor of her straight figure and the flash of her dark eyes.

"Mad at me, Phyl?" Crossing his arms on the pommel of the saddle he leaned toward her, half coaxing, half teasing.

The girl chose to ignore him and withdrew her gaze to the stage, still creeping antlike toward the hills.

he hummed audaciously, ready to catch her smile when it came.

It did not come. He thought he had never seen her carry her dusky good looks more scornfully. With a movement of impatience she brushed back a rebellious lock of blue-black hair from her temple.

"Somebody's acting right foolish," he continued jauntily. "It was all in fun, and in a game at that."

"I wasn't playing," he heard, though the profile did not turn in the least toward him.

"Well, I hated to let you stay a wall-flower."

"I don't play kissing games any more," she informed him with dignity.

"Sho, Phyl! I told you 'twas only in fun," he justified himself. "A kiss ain't anything to make so much fuss over. You ain't the first girl that ever was kissed."

She glanced quickly at him, recalling stories she had heard of his boldness with girls. He had taken off his hat and the golden locks of the boy gleamed in the sunlight. Handsome he surely was, though a critic might have found weakness in the lower part of the face. Chin and mouth lacked firmness.

"So I've been told," she answered tartly.

"Jealous?"

"No," she exploded.

Slipping to the ground, he trailed his rein.

"You don't need to depend on hearing," he said, moving toward her.

"What do you mean?" she flared.

"You remember well enough—at the social down to Peterson's."

"We were children then—or I was."

"And you're not a kid now?"

"No, I'm not."

"Here's congratulations, Miss Sanderson. You've put away childish things and now you have become a woman."

Angrily the girl struck down his outstretched hand.

"After this, if a fellow should kiss you, it would be a crime, wouldn't it?" he bantered.

"Don't you dare try it, Tom Dixon," she flashed fiercely.

Hitherto he had usually thought of her as a school girl, even though she was teaching in the Willow's district. Now it came to him with what dignity and unconscious pride her head was poised, how little the home-made print could conceal the long, free lines of her figure, still slender with the immaturity of youth. Soon now the woman in her would awaken and would blossom abundantly as the spring poppies were doing on the mountain side. Her sullen sweetness was very close to him. The rapid rise and fall of her bosom, the underlying flush in her dusky cheeks, the childish pout of the full lips, all joined in the challenge of her words. Mostly it was pure boyishness, the impish desire to tease, that struck the audacious sparkle to his eyes, but there was, too, a masculine impulse he did not analyse.

"So you won't be friends?"

If he had gone about it the right way he might have found forgiveness easily enough. But this did not happen to be the right way.

"No, I won't." And she gave him her profile again.

"Then we might as well have something worth while to quarrel about," he said, and slipping his arm round her neck, he tilted her face toward him.

With a low cry she twisted free, pushing him from her.

Beneath the fierce glow of her eyes his laughter was dashed. He forgot his expected trivial triumph, for they flashed at him now no childish petulance, but the scorn of a woman, a scorn in the heat of which his vanity withered and the thing he had tried to do stood forth a bare insult.

"How dare you!" she gasped.

Straight up the stairs to her room she ran, turned the lock, and threw herself passionately on the bed. She hated him...hated him...hated him. Over and over again she told herself this, crying it into the pillows where she had hidden her hot cheeks. She would make him pay for this insult some day. She would find a way to trample on him, to make him eat dirt for this. Of course she would never speak to him again—never so long as she lived. He had insulted her grossly. Her turbulent Southern blood boiled with wrath. It was characteristic of the girl that she did not once think of taking her grievance to her hot-headed father or to her brother. She could pay her own debts without involving them. And it was in character, too, that she did not let the inner tumult interfere with her external duties.

As soon as she heard the stage breasting the hill, she was up from the bed as swift as a panther and at her dressing-table dabbing with a kerchief at the telltale eyes and cheeks. Before the passengers began streaming into the house for dinner she was her competent self, had already cast a supervising eye over Becky the cook and Manuel the waiter, to see that everything was in readiness, and behind the official cage had fallen to arranging the mail that had just come up from Noches on the stage.

From this point of vantage she could cast an occasional look into the dining-room to see that all was going well there. Once, glancing through the window, she saw Tom Dixon in conversation with a half-grown youngster in leathers, gauntlets, and spurs. A coin was changing hands from the older boy to the younger, and as soon as the delivery window was raised little Bud Tryon shuffled in to get the family mail and that of Tom. Also he pushed through the opening a folded paper evidently torn from a notebook.

"This here is for you, Phyl," he explained.

She pushed it back. "I'm too busy to read it."

"It's from Tom," he further volunteered.

"Is it?"

She took the paper quietly but with a swift, repressed passion, tore it across, folded the pieces together, rent them again, and tossed the fragments through the window to the floor.

"Do you want the mail for the Gordons, too, Mr. Purdy?" she coolly asked the next in line over the tow head of Bud.

The boy grinned and ducked from his place through the door. Through the open window there drifted to her presently the sound of a smothered curse, followed by the rapid thud of a horse's hoofs. Phyllis did not look, but a wicked gleam came into her black eyes. As well as if she had seen him she beheld a picture of a sulky youth spurring home in dudgeon, a scowl of discontent on his handsome, boyish face. He had come down the mountain trail singing, but no music travelled with him on his return journey. Nor had she alone known this. Without deigning to notice it, she caught a wink and a nod from one vaquero to another. It was certain they would not forget to "rub it in" when next they met Master Tom. She promised herself, as she handed out newspapers and letters to the cowmen, sheep-herders, and miners who had ridden in to the stage station for their mail, to teach that young man his place.

"I'll take a dollar's worth of two's."

Phyllis turned her head in the slow, disdainful fashion she had inherited from her Southern ancestors and without a word pushed the sheet of stamps through the window. That voice, with its hint of sardonic amusement, was like a trumpet call to battle.

"Any mail for Buck Weaver?"

"No," she answered promptly without looking.

"Sure?"

"Yes."

"Couldn't be overlooking any, could you?"

Her eyes met his with the rapier steel of hostility. He was mocking her, for his mail all came to Saguaro. The man was her father's enemy. He had no business here. His coming was of a piece with all the rest of his insolence. Phyllis hated him with the lusty healthy hatred of youth. She had her father's generosity and courage, his quick indignation against wrong and injustice, and banked within her much of his passionate lawlessness.

"I know my business, sir."

Weaver turned from the window and came front to front with old Jim Sanderson. The burning black eyes of the Southerner, set in sockets of extraordinary depths, blazed from a grim, hostile face. Always when he felt ugliest Sanderson's drawl became more pronounced. His daughter, hearing now the slow, gentle voice, ran quickly round the counter and slipped an arm into that of her father.

"This hyer is an unexpected pleasure, Mr. Weaver," he was saying. "It's been quite some time since I've seen you all in my house before, makin' you'self at home so pleasantly. It's ce'tainly an honor, seh."

"Don't get buck ague, Sanderson. I'm here because I'm here. That's reason a-plenty for me," Weaver told him contemptuously.

"But not for me, seh. When you come into my house——"

"I didn't come into your house."

"Why—why——"

"Father!" implored the girl. "It's a government post-office. He has a right here as long as he behaves."

"H'm!" the old fire-eater snorted. "I'd be obliged just the same, Mr. Weaver, if you'd transact your business and then light a shuck."

"Dad!" the girl begged.

He patted her head awkwardly as it lay on his arm. "Now don't you worry, honey. There ain't going to be any trouble—leastways none of my making. I ain't a-forgettin' my promise to you-all. But I ain't sittin' down whilst anybody tromples on me neither."

"He wouldn't try to do that here," Phyllis reminded him.

Weaver laughed in grim irony. "I'm surely much obliged to you for protecting me." And to the father he added carelessly: "Keep your shirt on, Sanderson. I'm not trying to break into society. And when I do I reckon it won't be with a sheep outfit I'll trail."

With which parting shot he turned on his heel, arrogant and imperious to the last virile inch of him.

With the jingle of trailing spur Buck Weaver passed from the post-office to the porch, where public opinion was wont to formulate itself while waiting for the mail to be distributed. Here twice a week it had sat for many years, had heard evidence, passed judgment, condemned or acquitted. For at this store the Malpais country bought its ammunition, its tobacco, and its canned goods; and on this porch its opinions had sifted down to convictions. From this common meeting ground the gossip of Cattleland was scattered far and wide.

Weaver filled the doorway while he drew on his gauntlets. He was the owner of the Twin Star outfit, the biggest cattle company in that country. Nearly twenty years ago, while still a boy of eighteen, he had begun in a small way. The Malpais had been a wild and lawless place then, but in all the turbid days that followed Buck Weaver had held his own ruthlessly by adroit manipulation, shrewd sense, and implacable daring. Some outfits he had bought out; others he had driven away. Those that survived were at a respectable distance from him. Only the settlers in the hills remained to trouble him. He had come to be the big man of the district, dominating its social, business, and political activities.

"What's this I hear about another settler up on Bear Creek?" he asked curtly after he had gathered up his bridle and swung to the saddle.

"That's the way Jim Budd's telling it, Mr. Weaver. Another nester homesteaded there," old Joe Yeager answered casually, chewing tobacco with a noncommittal air.

"Fine! There'll soon be a right smart settlement up near the headwaters of the creeks, I shouldn't wonder. The cow business is getting to be a mighty profitable one when you don't own any," Buck said dryly.

The others laughed, but with small merriment. They were either small cattle owners themselves or range riders whose living depended on the business, and during the past two years a band of rustlers had operated so boldly as to have wiped out the profits of some of the ranchers. Most of them disliked Buck extremely for his overbearing ways. But they did not usually tell him so. On this particular subject, too, they joined hand with him.

"You're dead right, Mr. Weaver. It ce'tainly must be stopped."

The man who spoke rolled a cigarette and lit it. Like the rest he was in the common garb of the plains. The broad-brimmed felt hat, the shiny leather chaps, the loosely knotted bandanna, were as much a matter of course as the hard-eyed, weather-beaten look that comes of life under an untempered sun. But Brill Healy claimed a distinction above his fellows. He was a black-haired, picturesque fellow, as supple as a panther, reckless and yet wary.

"We'll have rustling as long as we have nesters, Brill," Buck told him.

"If that's the case we'll serve notice on the nesters to get out," Healy replied.

Buck grinned. Indomitable fighter though he was, he had been unable to roll back the advancing tide of settlement. Here and there homesteaders had taken up land and had brought in small bunches of cattle. Most of these were honest men, others suspected rustlers. But Buck's fiat had not sufficed to keep them out. They had held stoutly to their own and—he suspected—a good deal more than their own. Calves had been branded secretly and cows killed or driven away.

"Go to it, Brill," Weaver jeered. "I'm wishing you all the luck in the world."

He touched his pony with the spur and swept up the road in a cloud of white dust.

Not till he had disappeared did conversation renew itself languidly, for Seven Mile Ranch was lying under the lethargy of a summery sun.

"I expect Buck's got the right of it," volunteered a brawny youth known as Slim. "All you got to do is to take up a claim near a couple of big outfits with easy brands, then keep your iron hot and industrious. There's sure money in being a nester."

Despite the soft drawl of his voice, he spoke with bitterness, as did the others. Every day the feeling was growing stronger that the rustling must be stopped if they were going to continue to run cattle. The thieves had operated with a boldness and a shrewdness that fairly outwitted the ranchers. Enough horses and cattle had been driven across the line to stock a respectable ranch. Not one of the established ranches had escaped heavy losses; so heavy, indeed, that the owners faced the option of going broke or of exterminating the rustlers. Once or twice the thieves had nearly been caught red-handed, but the leader of the outlaws had saved the men by the most daring strategy.

Healy, until lately foreman of the Twin Star outfit, had organized the ranchmen as a protective association. In this he had represented Weaver, himself not popular enough to coöperate with the other ranchmen. Once Brill had led the pursuit of the rustlers and had come back furious from a long futile chase. For among the cattle being driven across to Sonora were five belonging to him.

Other charges also lay against the hill outlaws. A stage had been robbed with a gold shipment from the Diamond Nugget mine. A cattleman had been held up and relieved of two thousand dollars, just taken as part payment for a sale of beef steers. The sheriff of Noches County, while trying to arrest a rustler, had been shot dead in his tracks.

Brill Healy leaned forward, gathered the eyes of those present, and lowered his voice to a whisper. "Boys, this thing has got to stop. I've sent for Bucky O'Connor. If anybody can run the coyotes to earth he can. Anyhow, that's the reputation he's got."

Yeager nodded. "Good for you, Brill. He's ce'tainly got an A-one rep. as a cattle detective, and likewise as a man hunter. When is he coming?"

"He writes that he's got a job on hand that will keep him busy a couple of weeks, anyhow. After that we'll hear from him. I'm going to drop everything else, if necessary, and stay right with him on this job till he finishes it right," Healy promised.

"Now you're shoutin', Brill. Here, too. It's money in our pocket to stop this thing right now, even if we pay big for it. No use jest sittin' around till we're stole blind," assented Slim.

"It won't cost us anything. Buck, he pays the freight. The waddies have been hitting him right hard lately and he figures it will be up to him to clean them out. Course we expect help from you boys when we call on you."

"Sure. We'll all be with you till the cows come home, Brill," nodded one little fellow called Purdy. He was looking at a dust patch rising from the Bear Creek trail, and slowly moving toward them. "What's the name of this new nester, Jim?"

Budd, by way of being a curiosity on the range, was a fat man with a big double chin. He was large as well as fat, and, by queer contrast, the voice that came from that mountain of flesh was a small falsetto scarce above a whisper.

"Didn't hear his name. Had no talk with him. Hear he is called Keller," he said.

"What's he look like?"

"You-all can see for yourself. This here's the gent rolling a tail this way."

The little cloud of dust had come nearer and disclosed as its source a rider on a rangy roan with four white-stockinged feet. Drawing up in front of the porch, the man swung himself easily from the saddle and glanced around.

"Evening, gentlemen," he said pleasantly.

Some nodded grimly, some growled an acknowledgment of his greeting. But the lack of cordiality, the presence of hostility, could not be doubted. The young man stood at supple ease before them, one hand resting on his hip and the other on the saddle. He let his unabashed gaze travel from one to another, understood perfectly what those expressionless eyes of stone were telling him, and, with a little laugh of light derision, trailed debonairly into the store.

"Any mail for Larrabie Keller?" he inquired of the postmistress.

The girl at the window glanced incuriously at him and turned to look. When she pushed his letter through the grating he met for an instant a flash of dark eyes from a mobile face which the sun and superb health had painted to a harmony of gold and russet, with the soft glow of pink pushing through the tan. The unexpectedness of the picture magnetized his gaze. Admiration, frank and human, shone from the steel-gray eyes that had till now been only a mask. Beneath his steady look she flushed indignantly and withdrew from the window.

Convicted of rudeness, the last thing he had meant, Keller returned to the porch and leaned against the door jamb while he opened his letter. His appearance immediately sandbagged conversation. Stony eyes were focused upon him incuriously, with expressionless hostility.

He noted, however, an exception. Another had been added to the group, a lad of about eighteen, slim and swarthy, with the same dark look of pride he had seen on the face at the stamp window. It was easy to guess that they were brother and sister, very likely twins, though he found in the boy's expression a sulky impatience lacking in hers. Perhaps the lad needed the discipline that life hammers into those who want to be a law unto themselves.

With an insolence extremely boyish, the lad turned to Healy. "I'm for running out a few of these nesters. We've got more than we can use, I reckon. The range is overstocked now—both with them and cows. Come a bad year and half of our cattle will starve."

There was a moment of surcharged silence. Phil Sanderson had voiced the growing feeling of them all, but he had flung it out as a stark challenge before the time was ripe. It was one thing to resent the coming of settlers; it was quite another to set themselves openly against the law that allowed these men to homestead the natural parks in the hills.

Brill Healy laughed. "The fat's in the fire now, sure enough. Just the same, I back your play, Phil."

He turned recklessly to the man in the doorway. "You may tell your friends up on Bear Creek that we own this range and mean to hold it. We don't aim to let our cattle be starved, and we don't aim to lie down before rustlers. Understand?"

The nester smiled, but there was no gayety in his eyes. They met those of the cattleman with a grip of steel, and measured strength with him. Each knew the other would go the limit before Keller made quiet answer:

"I think so."

And with that he dismissed the subject and his unfriendly audience. With perfect ease, he read his letter, pocketed it, and whistled softly as he impassively took stock of the scenery. Apparently he had wiped Public Opinion from his map, and was interested only in the panorama before him.

Seven Mile Ranch lay rooted at the desert terminus among the foothills, a gateway between the mountains and the Malpais Plain. Below was a shimmering stretch of sand and cactus tortured beneath a blazing sun. Into that caldron with its furnace-cracked floor the sun had poured itself torridly for countless eons. It was a Sahara of mirage and desolation and death.

To the left was a flat-topped mesa eroded to fantastic mockery of some bastioned fort. In the round-topped hills behind it was Noches, fifty miles away. Beyond lay the tangle of hills, rising to the saw-toothed range now painted with orange and mauve and a hint of deepening purple. For dusk was already slipping down over the peaks.

"Mail's been open half an hour, boys," Phyllis announced through the open window.

They dropped in to the store, as noisy as schoolboys, but withal deferential. It was clear the young postmistress reigned a queen among the younger ones, but a queen that deigned to friendship with her subjects. Some of them called her Miss Sanderson, one or two of them Phyllie.

Among these last was Healy, who appeared on very good terms with her indeed. He appointed himself a sort of master of ceremonies, and handed to each man his mail with appropriate jocular comments designed to embarrass the recipient. He knew them all, and his hits were greeted with gay laughter. To the man standing in the doorway with his back to them, they seemed all one happy family—and himself a rank outsider. He trailed down the steps and swung himself to the saddle. As he loped away the sound of her warm, clear laughter floated after him.

From a cleft in the hills two riders emerged, following a little gulch to the point where it widened into a draw. The alkali dust of Arizona lay thick upon their broad-brimmed Stetsons and every inch of exposed surface, but through the gray coating bloomed the freshness of youth. It rang from their voices, was apparent in the modelling and carriage of their figures. The young man was sinewy and hard as nails, the girl supple and wiry, of a slender grace, straight-backed as an Indian in the saddle.

Just where the draw dipped down into the grassy park they drew rein an instant. Faint and far a sound drifted to them. Somebody down in the park had fired a rifle.

"I don't agree with you, Phil," the girl said, picking up the thread of their conversation where they had dropped it some minutes earlier. "The nesters have as much right here as we have. They come here to settle, and they take up government land. Why shouldn't they?"

"Because we got here first," he retorted impatiently. "Because our cattle and sheep have been feeding on the land they are fencing. Because they close the water holes and the creeks and claim they are theirs. It means the end of the open range. That's what it means."

"Of course that's what it means. We'll have to adapt ourselves to it. You talk foolishness when you make threats to drive out the nesters. That is the sort of thing Buck Weaver has been trying to do. It's absurd. The law is back of them. You would only come to trouble, and if you did succeed others would take their places."

"And rustle our cattle," he added sullenly.

"It isn't proved they are the rustlers. You haven't a shred of evidence. Perhaps they are, but you should prove it before you make the charge."

"If they aren't, who is?" he flared up.

"I don't know. But whoever it is will be caught and punished some day. There is no doubt at all about that."

"You talk a heap of foolishness, Phyl," he answered resentfully. "My notion is they never will be caught. What makes you so sure they will?"

They had been riding down the draw, and at this moment Phyllis looked up, to see a rider silhouetted against the sky line on the ridge above.

"Oh, you Brill!" she cried, with a wave of her quirt.

The man turned, saw them, and rode slowly down. He nodded, after the fashion of the range, first to the girl, and then to her brother.

"Morning," he nodded. "Headed for Mesa? Here, too."

He fell in with them and rode beside the girl. Presently they topped a little hillock, and looked down into the park. It had about the area of a mile, and was perhaps twice as long as broad. Wooded spurs ran down from the hills into it here and there, and through the meadow leaped a silvery stream.

"Hello! Wonder where that smoke comes from?"

It was Healy that spoke. He pointed to a faint cloud rising from a distance. Even before he began to speak, however, Phyllis had her field glasses out, and was adjusting them to her eyes.

"There's a fire there and a man standing over it," she presently announced. "There's something else there, too. I can't make it out—something lying down."

The men glanced at each other, and in the meeting of their eyes some intelligence passed between them. It was as if the younger accused and the older sullenly denied.

"Lemme have the glasses," Phil said to his sister almost roughly.

Healy glanced at Phil swiftly, covertly, as the latter adjusted the glasses. "She's right about the fire and the man. I can see as much with my naked eyes," he cut in.

The boy looked long, lowered the glasses, and met his friend's eye with a kind of shamefaced hesitation. But apparently he gathered reassurance from the quiet steadiness with which the other's gaze met him. He handed the glasses to Healy. When the latter lowered them his face was grave. "There's a man and a fire and a cow and a calf. When these four things meet up together, what does it mean?"

"Branding!" cried the girl.

"That's right—branding. And when the cow is dead what does it mean?" Brill asked, his eyes full on Phil.

"Rustling!" she breathed again.

"You've said it, Phyl. We've got one of them at last," he cried jubilantly.

Phil, hanging between doubt and suspicion and shame, brightened at the enthusiasm of the other.

"Right you are, Brill. We'll solve this mystery once for all."

Healy, unstrapping the case in which lay his rifle, shot a question at the boy. "Armed, Phil?"

The lad nodded. "I brought my six-gun for rattlesnakes."

"Are you going to—to——" cried Phyllis, the color gone from her face.

"We're going to capture him alive if we can, Phyl. You're to wait right here till we come back. You may hear shooting. Don't let that worry you. We've got the drop on him, or will have. Nobody is going to get hurt if he acts sensible," Healy reassured.

"Don't you move from here. You stay right where you are," her brother ordered sharply.

"Yes," she said, and was aware that her throat was suddenly parched. "You'll be careful, won't you, Phil?"

"Sure," he called back, as he put his horse at a canter to follow his friend up the draw.

The sound of the hoofs died away, and she was alone. That they were going to circle in and out among the tangle of hills until they were opposite the miscreant, she knew, but in spite of Brill's promise she had a heart of water. With trembling fingers she raised the glasses again, and focused them on that point which was to be the centre of the drama.

The man was moving about now, quite unconscious of the danger that menaced him. What she looked at was the great crime of Cattleland. All her life she had been taught to hold it in horror. But now something human in her was deeper than her detestation of the cowardly and awful thing this man had just done. She wanted to cry out to him a warning, and did in a faint, ineffective voice that carried not a tenth of the distance between them.

She had promised to remain where she was, but her tense interest in what was doing drew her forward in spite of herself. She rode along the ridge that bordered the park, at first slowly and then quicker as the impulse grew in her to be in at the finish.

The climax came. She saw him look round quickly, and in an instant his pony was at the gallop and he was lying low on its neck. A shot rang out, and another, but without checking his flight. He turned in the saddle and waved a derisive hand at the shooters, then plunged into a wash and disappeared.

What inspired her she could never tell. Perhaps it was her indignation at the thing he had done, perhaps her anger at that mocking wave of the hand with which he had vanished. She wheeled her horse, and put it at a canter down the nearest draw so as to try to intercept him at right angles. Her heart beat fast with excitement, but she was conscious of no fear.

Before she had covered half the distance, she knew she was going to be too late to cut off his retreat. Faintly, she heard the rhythm of hoofs striking the rocky bottom of the draw. Abruptly they ceased. Wondering what that could mean, she found her answer presently. For the pounding of the galloping broncho had renewed itself, and closer. The man was riding up the gulch toward her. He had turned into its mesquite-laced entrance for a hiding place. Phyllis drew rein, and waited quietly to confront him, but with a pulse that hammered the moments for her.

A white-stockinged roan, plowing a way through heavy sand, labored into view round the bend, its rider slewed in the saddle with his whole attention upon the possible pursuit. Not until he was almost upon her did the man turn. With a startled exclamation at sight of the motionless figure, he pulled up sharply. It was the nester, Keller.

"You," she cried.

"Happy to meet you, Miss Sanderson," he told her jauntily.

His revolver slid into its holster, and his hat came off in a low bow. White, even teeth gleamed in a sardonic smile.

"So you are a—rustler," she told him scornfully.

"I hate to contradict a lady," he came back, with a kind of bitter irony.

She saw something else, a deepening stain that soaked slowly down his shirt sleeve.

"You are wounded."

"Am I?"

"Aren't you?"

"Come to think of it, I believe I am," he laughed shortly.

"Badly?"

"I haven't got the doctor's report yet." There was a gleam of whimsical gayety in his eyes as he added: "I was going to find him when I had the good luck to meet up with you."

He was a hunted miscreant, wounded, riding for his life as a hurt wolf dodges to shake off the pursuit, but strangely enough her gallant heart thrilled to the indomitable pluck of him. Never had she seen a man who looked more the vagabond enthroned. His crisp bronze curls and his superb shoulders were bathed in the sunpour. Not once, since his eyes had fallen on her, had he looked back to see if his hunters had picked up the lost trail. He was as much at ease as if his whole thought at meeting her were the pleasure of the encounter.

"Can you ride?" she demanded.

"I can stick on a hawss if it's plumb gentle. Leastways I've been trying to for twenty years," he drawled.

Her impatient gesture waved his flippancy aside. "I mean, are you too much hurt to ride? I'm not going to leave you here like a wounded coyote. Can you follow me if I lead the way?"

"Yes, ma'am."

She turned. He followed her obediently, but with a ghost of a smile still flickering on his face.

"Am I your prisoner, Miss Sanderson?" he presently wanted to know.

"I'm not thinking of prisoners just now," she answered shortly, with an anxious backward glance.

Presently she pulled up and wheeled her horse, so that when he halted they sat facing each other.

"Let me see your arm," she ordered.

Obediently he held out to her the one that happened to be nearest. It was the unwounded one. An angry spark gleamed in her eye.

"This is no time to be fresh. Give me the other."

"Yes, ma'am." he answered, with deceptive meekness.

Without comment, she turned back the sleeve which came to the wrist gauntlet, and discovered a furrow ridged by a rifle bullet. It was a clean flesh wound, neither deep nor long enough to cause him trouble except for the immediate loss of blood. To her inexperience it looked pretty bad.

"A plumb scratch," he explained.

She took the kerchief from her neck, and tied it about the hurt, then pulled down the sleeve and buttoned it over the brown forearm. All this she did quite impersonally, her face free of the least sympathy.

"Thank you, ma'am. You're a right friendly enemy."

"It isn't a matter of friendship at all. One couldn't leave a wounded jack rabbit in pain," she retorted coldly, taking up the trail again.

There was room for two abreast, and he chose to ride beside her. "So you tied me up because it was your Christian duty," he soliloquized aloud. "Just the same as if I had been a mangy coyote that was suffering."

"Exactly."

He let his cool eyes rest on her with a hint of amusement. "And what were you thinking of doing with me now, ma'am?"

"I'm going to take you up to Jim Yeager's mine. He is doing his assessment work now, and he'll look out for you for a day or two."

"Look out for me in a locked room?" he wanted to know casually.

"I didn't say so. It isn't my business to arrest criminals," she told him icily.

His eyes gleamed mischief. "Is it your business to help them to escape?"

"I'm not helping you to escape. I'll not risk your dying in the hills alone. That is all."

"Jim Yeager is your friend?"

"Yes."

"And you guarantee he'll keep his mouth padlocked and not betray me?"

"He'll do as he pleases about that," she said indifferently.

"Then I don't reckon I'll trouble his hospitality. Good-by, Miss Sanderson. I've enjoyed meeting you very much."

He checked his pony and bowed.

"Where are you going?" the girl exclaimed.

"Up Bear Creek."

"It's twenty miles. You can't do it."

"Sure I can. Thanks for your kindness, Miss Sanderson. I'll return the handkerchief some day," and with a touch swung round his pony.

"You're not going. I won't have it, and you wounded!"

He turned in the saddle, smiling at her with jaunty insouciance.

"I'll answer for Jim. He won't betray you," she promised, subduing her pride.

"Thanks. I'll take your word for it, but I won't trouble your friend. I've had all the Christian charity that's good for me this mo'ning," he drawled.

At that she flamed out passionately: "Do you want me to tell you that I like you, knowing what you are? Do you want me to pretend that I feel friendly when I hate you?"

"Do you want me to be under obligations to folks that hate me?" he came back with his easy smile.

"You have lost a lot of blood. Your arm is still bleeding. You know I can't let you go alone."

"You're ce'tainly aching for a chance to be a Good Samaritan, Miss Sanderson."

With this he left her. But he had not gone a hundred yards before he heard her pony cantering after his. One glance told him she was furious, both at him and at herself.

"Did you come after your handkerchief, ma'am? I'm not through with it yet," he said innocently.

"I'm going with you. I'm not going to leave you till we meet some one that will take charge of you," she choked.

"It isn't necessary. I'm much obliged, ma'am, but you're overestimating the effect of this pill your friend injected into me."

"Still, I'm going. I won't have your death on my hands," she told him defiantly.

"Sho! I ain't aimin' to pass over the divide on account of a scratch like this. There's no danger but what I can look out for myself."

She waited in silence for him to start, looking straight ahead of her.

He tried in vain to argue her out of it. She had nothing to say, and he saw she was obstinately determined to carry her point.

Finally, with a little chuckle at her stubbornness, he gave in and turned round.

"All right. Yeager's it is. We're acting like a pair of kids, seems to me." This last with a propitiatory little smile toward her which she disdained to answer.

Yeager saw them from afar, and recognized the girl.

"Hello, Phyllis!" he shouted down. "With you in a minute."

The girl slipped to the ground, and climbed the steep trail to meet him. Her crisp "Wait here," flung over her shoulder with the slightest turn of the head, kept Keller in the saddle.

Halfway up she and the man met. The one waiting below could not hear what they said, but he could tell she was explaining the situation to Yeager. The latter nodded from time to time, protested, was vehemently overruled, and seemed to leave the matter with her. Together they retraced their way. Young Yeager, in flannel shirt and half-leg miner's boots, was a splendid specimen of bronzed Arizona. His level gaze judged the man on horseback, approved him, and met him eye to eye.

"Better light, Mr. Keller. If you come in we'll have a look at your arm. An accident like that is a mighty awkward thing to happen to a man on the trail. It's right fortunate Miss Sanderson found you so soon after it happened."

The nester knew a surge of triumph in his blood, but it did not show in the impassive face which he turned upon his host.

"It was right fortunate for me," he said, swinging from the saddle. Incidentally he was wondering what story had been narrated to Yeager, but he took a chance without hesitation. "A fellow oughtn't to be so careless when he's got a gun in his hand."

"You're right, seh. In this country of heavy underbrush a man's gun is liable to go off and hit somebody any time if he ain't careful. You're in big luck you didn't shoot yourself up a heap worse."

Yeager led the way to his cabin, and offered Phyllis the single chair he boasted, and the nester a seat on the bed. Sitting beside him, he examined the wound and washed it.

"Comes to being an invalid I'm a false alarm," Keller said apologetically. "I didn't want to come, but Miss Sanderson would bring me."

"She was dead right, too. Time you had ridden twenty miles through the hot sun with that wound you would have been in a raging fever."

"One way and another I'm quite in her debt."

"That's so," agreed Yeager, intent on his work.

She refused to meet the nester's smile. "Fiddlesticks! You talk mighty foolish, Jim. I wouldn't go away and leave a wounded dog if I could help it."

"Suppose the dog were a sheep-killer?" Keller asked with his engaging, impudent smile.

A dust cloud rose from her skirt under a stroke of the restless quirt. "I'd do my best for it and let it settle with the law afterward."

"Even if it were a wolf caught in a trap?"

"I should put it out of its pain. No matter how much I detested it, I wouldn't leave it there to suffer."

"I'm quite sure you wouldn't," the wounded man agreed.

Yeager looked from one to the other, not quite catching the drift of the underlying meaning. Another thing puzzled him, too. But, like most men of the unfenced Southwest, Yeager had a large capacity for silence. Now he attended strictly to his business, without mentioning what he had noticed.

The wound dressed, Phyllis rose to leave. "You'll be down for your mail to-morrow, Jim," she suggested, as she sauntered toward the door.

"Sure. I'll let you know how our patient is getting along."

"Oh, he's yours. I don't want any of the credit," she returned carelessly.

Then, the words scarce off her lips, she gave a little cry of alarm, and stepped quickly back into the room. What she had seen had sapped the color from her face. Yeager started forward, but she waved him back.

"It's Phil and Brill Healy. You've got to hide us, Jim," she told him tensely.

The nester began to grin. He always did when he faced a difficulty apparently insurmountable. Also his fingers slid toward the butt of his revolver.

Jim swept the cabin with a gesture. "Where can I hide you? Anyhow, there are the horses in plain sight."

Phyllis took imperious control. "Get a coat on him, Jim," she ordered.

At the same time she caught up the basin of bloodstained water and flung its contents through the open window. The torn linen and the stained handkerchief she tossed into a corner and covered with a gunny sack.

"Not a word about the wound, Jim. Mr. Keller is here to help you do your assessment work, remember. And whatever I say, don't give me away."

Yeager nodded. He had manoeuvred the wounded arm through the coat sleeve and was straightening out the shoulders. The nester's eyes were shining with excitement. Alone of the three, he was enjoying himself.

"Remember now. Don't talk too much. Let me run this," the girl cautioned, and with that she stepped to the door, caught sight of her brother with a glad little cry of apparent relief, and ran swiftly to him.

"Oh, Phil!" she almost sobbed, and the stress of her emotion was genuine enough, even if she dissembled as to the cause.

The boy patted her dark hair gently. They were twins, without other near relatives except their father, and the tie between them was close.

"What is it, Phyllie? Why didn't you stay where we left you?"

"I was afraid for you. And I rode a little nearer. Then he came straight toward me—and I rode away. I could hear him crashing through the mesquite. When I reached the trail of Jim's mine, I followed it, for I knew he would be here."

"Sure. Course she was scared. What woman wouldn't be? We oughtn't both to have left her. But there wasn't one chance in a thousand of his stumbling on the very spot where she was," said Healy.

Phil gentled her with a caressing hand. "It's all right now, sis. Did you happen to see the fellow at all?"

"Yes. At a distance."

"I don't suppose you would know him," Healy said.

She gave a strained little laugh. "I didn't wait to get a description of him. Didn't you boys recognize him?"

After Phil's answer she breathed freer. "We did not get near enough, though Brill got two shots at him as he pulled out. He was going hell-for-leather and Brill missed both times." He lowered his voice and asked angrily: "What's he doing here?"

For Keller had followed Yeager from the cabin and was standing in the doorway with his hands in his pockets. He wore no hat, and had the manner of one very much at home.

"He's helping Jim with his assessment work," she answered in the same low tone. "It's too bad you lost the rustler. He must have broken for the hills."

Healy's eyes had narrowed to slits. Now he murmured a question: "What about this man Keller? Was he here when you came, Phyl?"

The girl turned to Yeager, who had sauntered up. "Didn't you say he came this morning, Jim?"

Yeager's eyes were like a stone wall. "Yep. This mo'ning. I needed some husky guy to help me, so I got him."

"Funny you had to get a fellow from Bear Creek to help you, Jim."

"Are you looking for a job, Brill?"

"No. Why?"

"Because I ain't noticed any stampede this way among the boys to preempt this job. I take a man where I can find him, Brill, and I don't ask you to O.K. him."

"I see you don't, Jim. The boys aren't going to like it very well, though."

"Then they know what they can do about it," Yeager answered evenly, level eyes steadily on those of his critic.

"What time did this nester get here, Jim?" broke in Phil.

Yeager's opaque eyes passed from Healy to Sanderson. "It might have been about eight."

"Then he couldn't be the man," the boy said to Healy, almost in a whisper.

"What man?" Jim asked.

"We ran on a rustler branding a C.O. calf. We got close enough to take a shot at him. Then he slid into some arroyo, and we lost him," Phil exclaimed.

"How long ago was this?" asked Yeager.

"About an hour since we first saw him. Beats all how he ever made his getaway. We were right after him when he gave us the slip."

"Oh, he gave you the slip, did he?"

"Dropped into some hole and pulled it in after him. These hills are built for hide and seek, looks like."

"Notice the color of his horse?"

"It was a roan, Jim. Something like that nester's." Phil nodded toward the animal Keller had ridden.

All eyes focused hard on the horse with the white stockings.

"What brand was he putting on the calf? That'll tell you who the man was."

Phil and Healy looked at each other, and the latter laughed. "That's one on us. We didn't stay to look, but got right out for Mr. Rustler."

"Did he kill the cow?"

Phil nodded.

"Then you'll find the calf still hanging around there unless he had a pal to drive it away."

"That's right. We'll go back now and look. Ready, Phyl?"

"Yes." She stepped to her horse, and swung to the saddle.

Meanwhile Healy rode forward to the cabin. Through narrowed lids he looked down at the man standing in the doorway. "Give that message to your friends?" he demanded insolently.

There are men who have to look at each other only once to know that there is born between them a perpetual hostility. Each of these men had felt it at the first shock of meeting eyes. They would feel it again as often as they looked at each other.

"No," the nester answered.

"Why not?"

"I didn't care to. You may carry your own messages."

"When I do I'll carry them with a gun."

"Interesting if true." Keller's gaze passed derisively over him and dismissed the man.

"And I hope when I come I'll meet Mr. Keller first."

The nester's attention was focused indolently upon the hills. He seemed to have forgotten that the cattleman was in Arizona.

Healy ripped out a sudden oath, drove the spurs in, and went down the trail with his broncho on the buck.

Keller looked at Yeager and laughed, but that young man met him with a frosty eye.

"I've got some questions to ask you, Mr. Keller," he said.

"Unload 'em."

Yeager led the way inside, offered his guest the chair, and sat down on the bed with his arms on the table which had been drawn close to it.

"In the first place, I'll announce myself. I don't hold with rustlers or waddies. I'm a white man. That being understood, I want to know where we're at."

"Meaning?"

"Miss Phyllis unloads a story on me about you shooting yourself up accidental. Soon as I looked at you that looked fishy to me. You ain't that kind of a durn fool. Would you mind handing me a dipper of water? Thanks." Yeager tossed the water out of the window, and the dipper back into the pail. "I noticed you handed me that water with your right hand. Your gun is on your right side. Then how in Mexico, you being right-handed, did you manage to shoot yourself in the right arm below the elbow?"

Keller laughed dryly, and offered no information. "Quite a Sherlock Holmes, ain't you?"

"Hell, no! I got eyes in my head, though. Moreover, that bullet went in at right angles to your arm. How did you make out to do that?"

"Sleight of hand," suggested the other.

"No powder marks, either. And, lastly, it was, a rifle did it, not a revolver."

"Anything more?"

"Some. That side talk between you and Miss Phyllis wasn't over and above clear to me then. I savez it now. She hates you like p'ison, but she's too tender-hearted to give you up. Ain't that it?"

"That's it."

"She lied for you to me. She lied again to Phil. So did I. Oh, we didn't lie in words, but it's the same thing. Now, I wouldn't lie to save my own skin. Why then should I for yours, and you a rustler and a thief?"

"I'm a rustler and a thief, am I?"

"Ain't you?"

"Would you believe me if I said I wasn't?"

Yeager debated an instant before he answered flatly, "No."

"Then I won't say it."

The wounded man tossed his answer off so flippantly that Yeager scowled at him. "Mr. Keller, you're a newcomer here. I wonder if you know what the Malpais country would be liable to do to a man caught rustling now."

"I can guess."

"Let me tell what I know and your life wouldn't be worth a plugged quarter."

"Why didn't you tell?"

Yeager brought his big fist down heavily on the table. "Because of Phyl Sanderson. That's why. She put it up to me, and I played her game. But I ain't sure I'm going to keep on playing it. I'm a Malpais man. My father has a ranch down there, and I've rode the range all my life. Why should I throw down my friends to save a rustler caught in the act?"

"You've already tried and convicted me, I see."

"The facts convict you, seh."

"Your understanding of the facts, I reckon you mean."

"I haven't noticed that you're giving me any chance to understand them different," Yeager cut back dryly.

The nester took from his pocket a little pearl-handled knife, picked up a potato from a basket beside him, and began to whittle on it absently. He looked across the table at the man sitting on the bed, and debated a question in his mind. Was it best to confess the whole truth? Or should he keep his own counsel?

"I see you've got Miss Sanderson's knife. Did you forget to return it?" Yeager made comment.

For just an instant Keller's eye confessed amazement. "Miss Sanderson's knife! Why—how did you know it was hers?" he asked, gathering himself together lamely.

"I ought to know, seeing as I gave it to her for a Christmas present. Sent to Denver for that knife, I did. Best lady's knife in the market, I'm told. Made in Sheffield, England."

"Ye-es. It's sure a good knife. I'll ce'tainly return it next time I see her."

"Funny she ever let you get away with it. She's some particular who she lends that knife to," Jim said proudly.

Keller wiped the blade carefully, shut it, and put the knife back in his pocket. Nevertheless, he was worried in his mind. For what Yeager had told him changed wholly the problem before him. It suggested a possibility, even a probability, very distasteful to him. He was in trouble himself, and before he was through he expected to get others into deep water, too. But not Phyllis Sanderson—surely not this impulsive girl with the blue-black hair and dark, scornful eyes. Wherefore he decided to keep silent now and let Yeager do what he would.

"I reckon, seh, you'll have to do your own guessing at the facts," he said gently.

"Just as you say, Mr. Keller. I reckon if you had anything to say for yourself you would say it. Now, I'll do what talking I've got to do. You may stay here twenty-four hours. After that you may hit the trail for Bear Creek. I'm going down to Seven Mile to tell what I know."

"That's all right. I'll go along and return the pocketknife."

Yeager viewed him with stern disgust. "Don't make any mistake, seh. If you go down it's an even chance you'll never go back."

"Sure. Life's full of chances. There's even a chance I'm not a rustler."

"Then I'd advise you not to go down to Seven Mile with me. I'd hate to find out too late I'd helped hang the wrong man," Yeager dryly answered.

Having come to an understanding, Yeager and Keller wasted no time or temper in acrimony. Both of them belonged to that big outdoors West which plays the game to the limit without littleness. They were in hostile camps, but that did not prevent them from holding amiable conversation on the common topics of Cattleland. Only one of these they avoided by mutual consent. Neither of them had anything to say about rustling.

Together they ate and smoked and slept, and in the morning after breakfast they saddled and set out for Seven Mile. A man might have traveled far without seeing finer specimens of the frontier, any more competent, self-restrained, or fitter for emergency. They rode with straight back and loose seat, breaking long silences with occasional drawling comment. For in the cow country strong men talk only when they have something to say.

The stage had just left when they reached Seven Mile, and Public Opinion was seated on the porch as per custom. It regarded Keller with a stony, expressionless hostility. Yeager with frank disapprobation.

Just before swinging from the saddle, Jim turned to the nester. "I'm giving you an hour, seh. After that, I'm going to speak my little piece to the boys."

"Thank you. An hour will be plenty," Keller answered, and passed into the store, apparently oblivious of the silent observation focused upon him.

Phyllis, busy unwrapping a package of papers, glanced up to see his curly head in the stamp window.

"Anything for L. Keller?" he wanted to know, after he had unburdened himself of a friendly "Mornin', Miss Sanderson."

Her impulse was to ask him how his wound was, but she repressed it sternly. She took the letters from the K pigeonhole and found two for him.

"Thank you, I'm feeling fine," he laughed, gathering up his mail.

"I didn't ask you how you were feeling," she answered, turning coldly to her newspapers.

"I thought mebbe you'd want to know about my punctured tire."

"It's very good of you to relieve my anxiety."

"Let me relieve it some more, Miss Sanderson. Here's the knife you lost."

She glanced up carelessly at the pearl-handled knife he pushed through the window. "I didn't know it was lost."

"Well, now you know it's found. When do you remember seeing it last, ma'am?"

"I lent it to a friend two days ago."

"Oh, to a friend—two days ago."

His eyes were on her so steadily that the girl was aware of some significance he gave to the fact, some hidden meaning that escaped her.

"What friend did you say, Miss Sanderson?"

He asked it casually, but his question irritated her.

"I didn't say, sir."

"That's so. You didn't."

"Where did you get it?" she demanded.

He grinned. "I'll tell you that if you'll tell me who you lent it to."

Her curt answer reminded him that he was in her eyes a convicted criminal. "It's of no importance, sir."

"That's what you think, Miss Sanderson."

She sorted the newspapers in the bundle, and began to slip them into the private boxes where they belonged. Presently, however, her curiosity demanded satisfaction. Without looking at him, she volunteered information.

"But there's no mystery about it. Phil borrowed the knife to fix a stirrup leather, and forgot to give it back to me."

"Your brother?"

"Yes."

He was taken aback. There was nothing for it but a white lie. "I found it near Yeager's mine yesterday. I reckon he must have dropped it on his way there."

"I don't see anything very mysterious about that," she said frostily.

She looked so definitely unaware of him as she worked that he fell back from the window and passed out to the porch. He had found out more than he wanted to know.

Jim Yeager's drawling voice came to him, gentle and low as usual, but with an edge to it. "I been discoverin' I'm some unpopular to-day, Brill. Malpais has been expressin' its opinion right plain. You've arrived in time to chirp in with a 'Me, too.'"

Healy had evidently just ridden up, for he was still in the saddle. He relaxed into one of the easy attitudes used by men of the plains to rest themselves without dismounting.

"You know my sentiments, Jim," he replied, not unamiably.

"Sure I know them. Plumb dissatisfied with me, ain't you? Makes me feel awful bad." Jim was sailing into the full tide of his sarcasm when Keller touched him on the shoulder.

"I'd like to see you for a moment, Mr. Yeager, if you can give me the time," he said.

Healy took in the nester with an eye of jade. "Your twin brother wants you, Jim. Run along with him. Don't mind us."

"I won't, Brill."

The young man rose, and sauntered off with the Bear Creek settler. At the corral fence, some fifty yards from the house, he stopped under the shade of a live oak, and put his arms on the top rail. He had allowed himself to show no sign of it, but he resented this claim upon him that seemed to ally him further with the enemy.

"Here I am, Mr. Keller. What can I do for you?"

"You're a friend of Miss Sanderson. You would stand between her and trouble?" the other demanded abruptly.

"I expect."

"Then find out for me what Phil Sanderson did with the knife his sister lent him two days ago. Find out whether he lent it to anybody, and, if so, who."

"What for?"

It had come to a show-down, and the other tabled his cards.

"I found that knife yesterday mo'ning. It was lying beside the dead cow in the park where your friends happened on me. I reckon the rustlers must have heard me coming and drove the calf away just before I arrived. In his hurry one of them forgot that knife. If you'll tell me the man who had it in his pocket yesterday when he left-home, I'll tell you who one of the Malpais rustlers is."

Jim considered this, his gaze upon the far-away range. When he brought it back to Keller, he was smiling incredulously.

"I hear you say so, seh. But what a man with, a halter round his neck says don't go far before a court."

"I expected you to say about that."

"Then I haven't disappointed you." He continued presently, with cold hostility: "That story you cooked up is about the only one you could spring. What surprises me is that a man with as good a head as yours took twenty-four hours to figure out your explanation. I want to tell you, too, that it don't make any hit with me that you're trying to throw the blame on a boy I've known all my life."

"Who happens to be a brother of Miss Sanderson," Keller let himself suggest.

Yeager flushed. "That ain't the point."

"The point is that I'm trying to clear this boy, and I want your help."

"Looks to me like you want to clear yourself."

"If I prove to you that I'm not a rustler, will you padlock your tongue and help me clear young Sanderson?"

"I sure will—if you prove it to my satisfaction."

Keller drew from his pocket the two letters he had just received. "Read these."

When he had read, Yeager handed them back, and offered his hand. "That clears you, seh. Truth is, I never was satisfied you was a rustler. My mind was satisfied; but, durn it, you didn't look like a waddy. It's lucky I hadn't spoke to the boys yet."

"I want to keep this quiet," the Bear Creek settler explained.

"Sure. I'm a clam, and at your service, seh."

"Then find out the truth about the knife."

Yeager's eye chiselled into that of Keller. "Mind, I ain't going to help you bring trouble to Phyllie, and I ain't going to stand by and see it, either."

The other smiled. "I don't ask it of you. What I want is to clear the boy."

"Good enough," agreed Yeager, and led the way back.

Before they had yet reached the house, a figure dropped from the foliage of the live oak under which they had been standing, and rolled like a ball from the fence into the deep dust of the corral. It picked itself up in a gray cloud, from which shone as a nucleus a black face with beady eyes and flashing-white teeth. Swiftly it scampered across the paddock, disappeared into the rear of the stable, and reappeared at the front door.

"Here you, 'Rastus, where you been?" demanded the wrangler. "Didn't I tell you to clean Miss Phyl's trap? I've wore my lungs out hollering for you. Now, you git to work, or I'll wear you to a frazzle."

'Rastus, general alias for his baptismal name of George Washington Abraham Lincoln Randolph, grinned and ducked, shot out of the stable like a streak of light, and appeared ten seconds later in the kitchen presided over by his rotund mother, Becky.

His abrupt entrance disturbed the maternal after-dinner nap. From the rocking-chair where she sat Becky rolled affronted eyes at him.

"What you doin' here, Gawge Washington? Ain't I done tole you sebenty times seben to keep outa my kitchen at dis time o' day?"

"I wanter see Miss Phyl."

"Then I low you kin take it out in wantin'. Think she got time to fool away on a nigger sprout like you-all? Light a shuck back to the stable, where you belong."

'Rastus grinned amiably, flung himself at a door, and vanished into that part of the house which was forbidden territory to him, the while Becky stared after him in amazement.

"What in tarnation got in dat nigger child?" she gasped.

Phyllis, having arranged the mail and delivered most of it, had left the store in charge of the clerk and retired to her private den, a cool room finished in restful tints at the northeast corner of the house. She was sitting by a window reading a magazine, when there came a knock. Her "Come in" disclosed 'Rastus and the whites of his rolling eyes.

She nodded and smiled. "What can I do for you, George Washington Abraham Lincoln Randolph?"

"I done come to tell you somepin I heerd whilst I was asleep in de live oak at the corral."

"Something you dreamed. It is very good of you, George Wash——"

"Now, don't you call me all dat again, Miss Phyl. And I didn't dream it nerrer. I woke up and heerd it. Mr. Jim Yeager and dat nester they call Keller wuz a-talkin', and Mr. Jim he allowed dat Keller wuz a rustler, and den Keller he allowed dat Mr. Phil wuz de rustler."

"What!" The girl had sprung to her feet, amazed, her dark eyes blazing indignation.

"Tha's what he said. He went on to tell how he done found a knife by the dead cow, an' 'twuz yore knife, an' you done loan it to Mr. Phil."

"He said that!" She was a creature transformed by passion. The hot blood of Southern ancestors raced through her veins clamorously. She wanted to strike down this man, to annihilate him and the cowardly lie he had given to shield himself. And pat to her need came the very person she could best use for her instrument.

Healy stood surprised in the doorway, confronted by the slender young amazon. The storm of passion in the eyes, the underlying flush in the dusky cheeks, indicated a new mood in his experience of this young woman of many moods.

"Come in and shut the door," she ordered. Then, "Tell him, 'Rastus."

The boy, all smiles gone now, repeated his story, and was excused.

"What do you think of that, Brill?" the girl demanded, after the door had closed on him.

The stockman's eyes had grown hard. "I think Keller's covering his own tracks. Of course we've got no direct proof, but——"

"We have," she broke in.

"I can't see it. According to Jim Yeager——"

"Jim lied. I asked him to."

"You—what?"

"I asked him to say that this man had come there to work for him. Jim was not to blame."

"But—why?"

She threw out a gesture of self-contempt. "Why did I do it? I don't know. Because he was wounded, I suppose."

"Wounded! Then I did hit him?"

"Yes. In the arm—a flesh wound. I met him riding through the mesquite. After I had tied up his wound, I took him to Jim's."

His eyes narrowed slightly. "So you tied up his wound?"

"Yes," she answered defiantly, her head up.

"That tender heart of yours," he murmured, with almost a sneer.

"Yes. I'm a fool."

He shrugged his shoulders. "Oh, well."

"And he pays me back by trying to throw it on Phil. Hunt him down, Brill. Bring him to me. I'll tell all I know against him," she cried vindictively.

"I'll get him, Phyl," he promised, and the sound of his laughter was not pleasant. "I'll get him for you, or find out why."

"Think of him trying to put it on Phil, and after I stood by him and kept his secret. Isn't that the worst ever?" the girl flamed.

"He rode away not five minutes ago as big as coffee on that ugly roan of his with the white stockings; knew what we thought about him, but didn't pay any more attention to us than as if we were bumps on a log."

Healy strode out to the porch, told his story, and within five minutes had organized his posse and appointed a rendezvous for two hours later at Seven Mile.

At the appointed time his men were on hand, six of them, armed with rifles and revolvers, ready for grim business.

From her window Phyllis saw them ride away, and persuaded herself that she was glad. Vengeance was about to fall upon this insolent freebooter who had not even manhood enough to appreciate a kindness. But as the hours passed she was beset by a consuming anxiety. What more likely than that he would resist! If so, there could be only one end. She could not keep her thoughts from those seven men whom she had sent against the one.

There was nobody to whom she could talk about it, for Phil and her father were away at Noches. Restless as a caged panther, she twice had her horse brought to the door, and rode into the hills to meet her posse. But she could not be sure which way they would come, and after venturing a short distance she would return for fear they might arrive in her absence. Night had fallen over the country, and the stars were out long before she got back the second time. Nine—ten—eleven o'clock struck, and still no sign of those for whom she waited.

At last they came, their prisoner riding in the midst, bareheaded and with his hands tied.

"I've got him, Phyl!" Healy cried in a voice that told the girl he was riding on a wave of triumph.

"I see you have."

Nevertheless she looked not at the victor, but at the vanquished, and never had she seen a man who looked more master of his fate than this one. He was smiling down at her whimsically, and she saw they had not taken him without a struggle. The marks of it were on them and on him. Healy's cheek bone was laid open in a nasty cut, and Slim had a handkerchief tied round his head.

As for Keller, his shirt was in ribbons and dyed with the stains of blood from the wound that had broken out again in the battle. The hair on the left side of his head was clotted with dried blood, and his cheeks were covered with it. Both eyes were blacked, and hands and face were scratched badly. But his mien was as jaunty, his smile as gallant, as if he had come at the head of a conquering army.

"Good evenin', Miss Sanderson," he bowed ironically.

She looked at him, and turned away without answering. She heard Healy curse softly and knew why. This man contrived somehow to rob him of his triumph.

"You are none of you hurt, Brill?" the girl asked in a low voice.

"No. He fought like a wild cat, but we took him by surprise. He had only his bare fists."

"How about him? Is he hurt?"

"I don't know—or care," the man answered sullenly.

"But he must be looked to."

"I don't know why. It ain't my fault we had to beat him up."

"I didn't say it was your fault, Brill," she answered gently. "But any one can see he has lost a lot of blood, and his wounds are full of dust. They must be washed. I want him brought into the house. Aunt Becky and I will look after him."

"No need of that. Slim will fix him up."

She shook her head. "No, Brill."

His eyes gave way first, but his surrender came with a bad grace.

"All right, Phyl. But he's going to be covered by a gun all the time. I'm not taking chances on him."

"Then have him taken into my den. I'll wake Aunt Becky and we'll be there in a few minutes."

When Phyllis arrived with Aunt Becky she found the nester sitting on the lounge, Healy opposite him with a revolver close to his hand. The prisoner's arms had been freed. His sardonic smile still twitched at the corners of his mouth.

"You've ce'tainly begun your practice on a disreputable patient, Doctor Sanderson. I haven't had time to comb my hair since that little séance with your friends. We sure did have a sociable time. They're all good mixers." He looked into the long glass opposite, laughed at sight of his swollen face, then rattled into a misquotation of some verses he remembered:

"Put the water and things down on that table, Becky," her mistress told her, ignoring the man's blithe folly.

"I'm giving you lots of chances to do the Good Samaritan act," he continued. "Honest, I hate to be so much trouble. You'll have to blame Mr. Healy. He's the responsible party for these little accidents of mine."

"I'm going to be responsible for one more," the stockman told him darkly.

"I understand your intentions are good, but I've noticed that sometimes expectation outruns performance," his prisoner came back promptly.

"Not this time, I think."

Phyllis understood that Brill was threatening the nester and that the latter was defying him lightly, but what either meant precisely she did not know. She proceeded to business without a word except the necessary directions to Becky. Not until the arm was dressed and the wound on the head washed and bandaged did she address Keller.

"I'll send you a powder that will help you get to sleep. The doctor left it here for Phil, and he did not need it," she said.

"Mebbe I won't need it, either." Keller laughed hardily, at his enemy it seemed to the girl, and with some hint of a sinister understanding between them from which she was excluded. "Thanks just the same, for that and for everything else you've done for me."

Phyllis said "Good night" stiffly, and followed the old negress out. She went directly to her bedroom, but not to sleep. The night was hot, and it had been to her a day full of excitement. She had much to think of. Going to the open window, she sat down in a low chair with her arms across the sill.

Two men met beneath her window.

"Gimme the makings, Slim," one said to the other.

While he was shaking the tobacco from the pouch to the paper, Slim spoke. "The boys ought all to be here in another hour, Budd. After that, it won't take us long."

"Not long," the fat man answered uneasily.

There was a silence. Slim broke it. "We got to do it, o' course."

"Looks like. Got to make an example. No peace on the range till we do."

"I hate like sin to, Budd. He's so damn game."

"Me, too. But we got to. No two ways about it."

"I reckon. Brill says so. But I wish the cuss had a chanct to fight for his life."

They moved off together in troubled silence, Budd's cigarette glowing red in the darkness. Behind them they left a girl shocked and rigid. They were going to lynch him! She knew it as certainly as if she had been told it in set words. Her blood grew cold, and she shivered. While the confused horror of it raced through her brain, she noticed subconsciously that her fingers on the sill were trembling violently.

What could she do? She was only a girl. These men deferred to her in the trivial pleasantries, but she knew they would go their grim way no matter how she pleaded. And it would be her fault. She had betrayed the rustler to them. It would be the same as if she had murdered him. He had known while she was tending his wounds that she had delivered him to death, and he had not even reproached her.

Courage flowed back to her heart. She would save him if it were possible. It must be by strategy if at all. But how? For of course he was guarded.

She stepped out into the corridor. All was dark there. She tiptoed along it to the guest room, and found the door unlocked. Nobody was inside. She canvassed in her mind the possibilities. They might have him outdoors or in the men's bunk house with them under a guard, or they might have locked him up somewhere until the arrival of the others. If the latter, it must be in the store, since that was the only safe place under lock and key.

Phyllis slipped out of the back door into the darkness, and skirted the house at a distance. There were lights in the bunk house of the ranch riders, and through the window she could see a group gathered. Creeping close to the window, she looked in. Their prisoner was not with them. In front of the store two men were seated in the darkness. She was almost upon them before she saw them. Each of them carried a rifle.

"Hello! Who's that?" one of them cried sharply.

It was Tom Dixon.

Phyllis came forward and spoke. "That you, Tom? I suppose you are guarding the prisoner."

"Yep. Can't you sleep, Phyl?" He walked a dozen yards with her.

"I couldn't, but I see you're keeping watch, all right. I probably can now. I suppose I was nervous."

"No wonder. But you may sleep, all right. He won't trouble you any. I'll guarantee that," he promised largely. "Oh, Phyl!"

She had turned to go, but she stopped at his call. "Well?"

"Don't you be mad at me. I was only fooling the other day. Course I hadn't ought to have got gay. But a fellow makes a break once in a while."

Under the stress of her deeper anxiety she had forgotten all about her tiff with him. It had seemed important at the time, but since then Tom and his affairs had been relegated to second place in her mind. He was only a boy, full of the vanity that was a part of him. Somehow, her anger against him was all burnt out.

"If you never will again, Tom," she conceded.

"I'll be good," he smiled, meaning that he would be good as long as he must.

"All right," she said, without much enthusiasm.

She left him and passed into the house without haste. But once inside she fairly flew to Phil's room. On a nail near the head of his bed hung a key. She took this, descended to the kitchen, and from there noiselessly down the stairway to the cellar. She groped her way without a light along the adobe wall till she came to a door which was unlocked. This opened into another part of the cellar, used as a room for storing supplies needed in their trade. Past barrels and boxes she went to another stairway and breathlessly ascended it. At the top of eight or nine steps a door barred progress. Very carefully she found the keyhole, fitted in the key, and by infinitesimal degrees unlocked the door.

The night seemed alive with the noise of her movements. Now the door creaked as it swung open before her. She waited, heart beating like a trip hammer, and stared into the blackness of the store.

"Who is it?" a voice asked in a low tone.

"It's me, Phyl Sanderson. Are you alone?" she whispered.

"Yes. Tied to a chair. Guards are just outside."

She went toward him softly with hands outstretched in the darkness, and presently her fingers touched his face. They travelled downward till they found the ropes which bound him. For a moment she fumbled at the knots before she remembered a swifter way.

"Wait," she breathed, and stole back of the counter to the case where pocketknives were kept.

Finding one, she ran to him and hacked at the rope till he was free.

He rose and stretched his cramped limbs.

"This way." Phyllis took him by the hand, and led him to the stairs. Together they descended, after she had locked the door. Another minute, and they stood in the kitchen, still hand in hand.

The girl released herself. "You will find Slim's horse tied to the fence of the corral. When you reach it, ride for your life," she said.

"Why have you saved me after you betrayed me?" he demanded.

"I save you because I did betray you. I couldn't have your blood on my head. Now, go."

"Not till I know why you betrayed me."

"You can ask that." Her indignation gathered and broke. "Because you are what you are. Because I know what you told Jim Yeager this afternoon. Why don't you go?"

"What did I tell Yeager? About the knife, you mean?"

"You tried to lay it on Phil to save yourself."

"Did Yeager tell you that?"

"No, but I know it," She pushed him toward the door. "Go, while there is still a chance."

"I'm not going—not yet. Not till you promise to ask Yeager what I said."

A footstep sounded, and the door opened. The intruder stopped, his hand still on the handle, aware that there were others in the room.

"Who is it?" Phyllis breathed, stricken almost dumb with terror.

"It's Slim. Hope I ain't buttin' in, Phyllie."

Unconsciously he had given her the cue she needed.

"Well, you are." She laughed nervously, as might a lover caught unexpectedly. "It's—it's Phil," she pretended to pretend.

"Oh, it's Phil." Slim laughed in kindly derision, and declared before he went out: "I expect you would spell his name B-r-i-double l. Don't forget to invite me to the wedding, Phyllie. Meanwhile I'll be mum as a clam till you say the word."

With which he jingled away. The door was scarce closed before the girl turned on Keller.

"There! You see. They may catch you any moment."

"Will you ask Yeager?"

"Yes, if you'll go."

"All right. I'll go."

Still he did not leave. The magic of this slim girl had swept him from his feet. In imagination he still felt the touch of her warm fingers, soft as a caress, the thrill of her hair as it had brushed his cheek when she had stooped over him. The drag of sex was upon him and had set him trembling strangely.

"Why don't you go?" she cried softly.

He snatched himself away.