"Father," laughed the daughter, "isn't this rather youngish?"

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net

Title: Bylow Hill

Author: George Washington Cable

Release Date: January 3, 2005 [eBook #14575]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK BYLOW HILL***

By GEORGE W. CABLE

Bylow Hill. Illustrated in color by F.C. Yohn. $1.25.

The Cavalier. Illustrated by H.C. Christy. $1.50.

John March, Southerner. $1.50.

Bonaventure. $1.50.

Dr. Sevier. $1.50.

The Grandissimes. $1.50.

Old Creole Days. $1.50.

Strong Hearts. $1.25.

Strange True Stories of Louisiana. Illustrated. $1.25.

The Creoles of Louisiana. Illustrated. $2.50.

The Silent South. With Portrait. $1.00.

The Negro Question. 75 cents.

IV. AND BRING DOWN THE REMAINDER

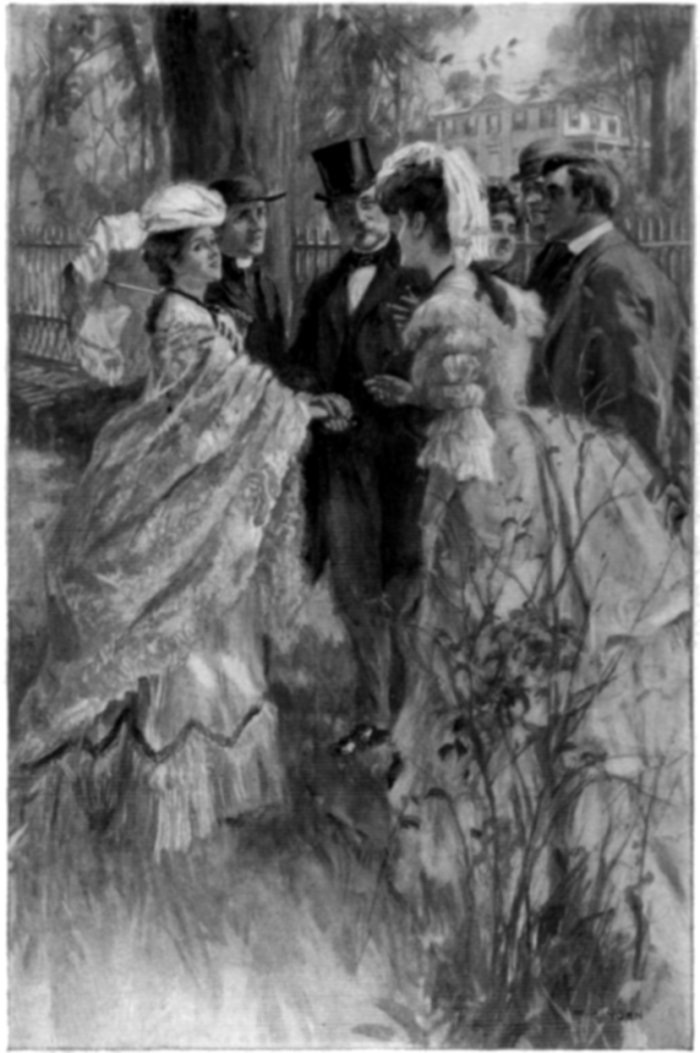

"Father," laughed the daughter, "isn't this rather youngish?" Frontispiece

Indeed it was clear that to go away would be unfair.

"Arthur Winslow, I give you five minutes."

"But to know every day and hour that I'm watched."

"I am waiting busily for her slayer."

"Arthur! Arthur! can't you speak?"

The old street, keeping its New England Sabbath afternoon so decently under its majestic elms, was as goodly an example of its sort as the late seventies of the century just gone could show. It lay along a north-and-south ridge, between a number of aged and unsmiling cottages, fronting on cinder sidewalks, and alternating irregularly with about as many larger homesteads that sat back in their well-shaded gardens with kindlier dignity and not so grim a self-assertion. Behind, on the west, these gardens dropped swiftly out of sight to a hidden brook, from the farther shore of which rose the great wooded hill whose shelter from the bitter northwest had invited the old Puritan founders to choose the spot for their farming village of one street, with a Byington and a Winslow for their first town officers. In front, eastward, the land declined gently for a half mile or so, covered, by modern prosperity, with a small, stanch town, and bordered by a pretty river winding among meadows of hay and grain. At the northern end, instead of this gentle decline, was a precipitous cliff side, close to whose brow a wooden bench, that ran half-way round a vast sidewalk tree, commanded a view of the valley embracing nearly three-quarters of the compass.

In civilian's dress, and with only his sea-bronzed face and the polished air of a pivot gun to tell that he was of the navy, Lieutenant Godfrey Winslow was slowly crossing the rural way with Ruth Byington at his side. He had the look of, say, twenty-eight, and she was some four years his junior. From her father's front gate they were passing toward the large grove garden of the young man's own home, on the side next the hill and the sunset. On the front porch, where the two had just left him, sat the war-crippled father of the girl, taking pride in the placidity of the face she once or twice turned to him in profile, and in the buoyancy of her movements and pose.

His fond, unspoken thought went after her, that she was hiding some care again,—her old, sweet trick, and her mother's before her.

He looked on to Godfrey. "There's endurance," he thought again. "You ought to have taken him long ago, my good girl, if you want him at all." And here his reflections faded into the unworded belief that she would have done so but for his, her own father's, being in the way.

The pair stopped and turned half about to enjoy the green-arched vista of the street, and Godfrey said, in a tone that left his companion no room to overlook its personal intent, "How often, in my long absences, I see this spot!"

"You wouldn't dare confess you didn't," was her blithe reply.

"Oh yes, I should. I've tried not to see it, many a time."

"Why, Godfrey Winslow!" she laughed. "That was very wrong!"

"It was very useless," said the wanderer, "for there was always the same one girl in the midst of the picture; and that's the sort a man can never shut out, you know. I don't try to shut it out any more, Ruth."

The girl spoke more softly. "I wish I could know where Leonard is," she mused aloud.

"Did you hear me, Ruth? I say I don't try any more, now."

"Well, that's right! I wonder where that brother of mine is?"

The baffled lover had to call up his patience. "Well, that's right, too," he laughed; "and I wonder where that brother of mine is? I wonder if they're together?"

They moved on, but at the stately entrance of the Winslow garden they paused again. The girl gave her companion a look of distress, and the young man's brow darkened. "Say it," he said. "I see what it is."

"You speak of Arthur"—she began.

"Well?"

"What did you make out of his sermon this morning?"

"Why, Ruth, I—What did you make out of it?"

"I made out that the poor boy is very, very unhappy."

"Did you? Well, he is; and in a certain way I'm to blame for it."

The girl's smile was tender. "Was there ever anything the matter with Arthur, and you didn't think you were in some way to blame for it?"

"Oh, now, don't confuse me with Leonard. Anyhow, I'm to blame this time! Has Isabel told you anything, Ruth?"

"Yes, Isabel has told me!"

"Told you they are engaged?"

"Told me they are engaged!"

"Well," said the young man, "Arthur told me last night; and I took an elder brother's liberty to tell him he had played Leonard a vile trick."

"Godfrey!"

"That would make a much happier nature than Arthur's unhappy, wouldn't it?"

Ruth was too much pained to reply, but she turned and called cheerily, "Father, do you know where Leonard is?"

The father gathered his voice and answered huskily, laying one hand upon his chest, and with the other gesturing up by the Winslow elm to the grove behind it.

She nodded. "Yes!... With Arthur, you say?... Yes!... Thank you!... Yes!" She passed with Godfrey through the wide gate.

"That's like Leonard," said the lover. "He'll tell Arthur he hasn't done a thing he hadn't a perfect right to do."

"And Arthur has not, Godfrey. He has only been less chivalrous than we should have liked him to be. If he had been first in the field, and Leonard had come in and carried her off, you would have counted it a perfect mercy all round."

"Ho-oh! it would have been! Leonard would have made her happy. Arthur never can, and she can never make him so. But what he has done is not all: look how he did it! Leonard was his beloved and best friend"—

"Except his brother Godfrey"—

"Except no one, Ruth, unless it's you. I'm neither persuasive nor kind, nor often with him. Proud of him I was, and never prouder than when I knew him to be furiously in love with her, while yet, for pure, sweet friendship's sake, he kept standing off, standing off."

"I wish you might have seen it, Godfrey. It was so beautiful—and so pitiful!"

"It was manly,—gentlemanly; and that was enough. Then all at once he's taken aback! All control of himself gone, all self-suppression, all conscience"—

"The conscience has returned," said the girl.

"Oh, not to guide him! Only to goad him! Fifty consciences can't honorably undo the mischief now!"

"Did I not write you that there was already, then, a coolness between her and Leonard?"

"Yes; but the whole bigness and littleness of Arthur's small, bad deed lies in the fact that, though he knew that coolness was but a momentary tiff, with Isabel in the wrong, he took advantage of it to push his suit in between and spoil as sweet a match as two hearts were ever making."

"It was more than a tiff, Godfrey; it"—

"Not a bit more! not—a—bit!"

"Yes!—yes—it was a problem! a problem how to harmonize two fine natures keyed utterly unlike. Leonard saw that. That is why he moved so slowly."

"Hmm!" The lover stared away grimly. "I know something about slowness. I suppose it's a virtue—sometimes."

"I think so," said the girl, caressing a flower.

"Ah, well!" responded the other. "She has chosen a nature now that—Oh me!... Ruth, I shall speak to her mother! I am the only one who can. I'll see Mrs. Morris some time this evening, and lay the whole thing out to her as we four see it who have known one another almost from the one cradle."

Ruth smiled sadly. "You will fail. I think the matter will have to go on as it is going. And if it does, you must remember, Godfrey, we do not really know but they may work out the happiest union. At any rate, we must help them to try."

"If they insist on trying, yes; and that will be the best for Leonard."

"The very best. One thing we do know, Godfrey: Arthur will always be a passionate lover, and dear Isabel is as honest and loyal as the day is long."

"The day is not long; this one is not—to me. It's most lamentably short, and to-morrow I must be gone again. I have something to say to you, Ruth, that"—

The maiden gave him a look of sweet protest, which suddenly grew remote as she murmured, "Isabel and her mother are coming out of their front door."

There were two dwellings in the Winslow garden,—one as far across at the right of the Byington house as the other was at the left. The one on the right may have contained six or eight bedchambers; the other had but three. The larger stood withdrawn from the public way, a well-preserved and very attractive example of colonial architecture, refined to the point of delicacy in the grace and harmony of its details. Here dwelt Arthur Winslow, barely six weeks a clergyman, alone but for two or three domestics and the rare visits of Godfrey, his only living relation. The other and older house, in the garden's southern front corner, was a gray gambrel-roofed cottage, with its threshold at the edge of the sidewalk; and it was from this cottage that Isabel and her mother stepped, gratefully answering the affectionate wave of Ruth's hand,—Mrs. Morris with the dignity of her forty-odd years, and Isabel with a sudden eager fondness. The next moment the two couples were hidden from each other by the umbrageous garden and by the tall white fence, in which was repeated the architectural grace of the larger house.

Mother and daughter conversed quietly, but very busily, as they came along this enclosure; but presently they dropped their subject to bow cordially across to the father of Ruth, and when he endeavored to say something to them Mrs. Morris moved toward him. Isabel took a step or two more in the direction of the Winslow elm and its inviting bench, but then she also turned. She was of a moderate feminine stature and perfect outline, her step elastic, her mien self-contained, and her face so young that a certain mature tone in her mellow voice was often the cause of Ruth's fond laughter. As winsome, too, she was, as she was beautiful, and "as pink as a rose," said the old-time soldier to himself, as he came down his short front walk, throwing half his glances forward to her, quite unaware that he was equally the object of her admiration.

Though white-haired and somewhat bent he was still slender and handsome, a most worthy figure against the background of the red brick house, whose weathered walls contrasted happily with the blossoming shrubs about their base, and with the green of lawn and trees.

"Good-afternoon, Isabel. I was saying to your mother, I hope such days as this are some offset for the Southern weather and scenery you have had to give up."

"You shouldn't tempt our Southern boastfulness, General," Isabel replied, with an air of meek chiding. She had a pretty way of skirmishing with men which always brought an apologetic laugh from her mother, but which the General had discovered she never used in a company of less than three.

"Oh! ho, ho!" laughed Mrs. Morris, who was just short, plump, and pretty enough to laugh to advantage. "Why, General,"—she sobered abruptly, and she was just pretty and plump and short enough to do this well, also,—"my recovered health is offset enough for me."

"For us, my dear," said the daughter. "My mother's restored health is offset enough for us, General. Indeed, for me"—addressing the distant view—"there is no call for off-set; any landscape or climate is perfect that has such friends in it as—as this one has."

"Oh! ho, ho!" laughed the mother again. Nobody ever told the Morrises they had a delicious Southern accent, and their words are given here exactly as they thought they spoke them.

"My dear," persisted Isabel, rebukingly, "I mean such friends as Ruth Byington."

Mrs. Morris let go her little Southern laugh once more. "Don't you believe her, General—don't you believe her. She means you every bit as much as she means Ruth. She means everybody on Bylow Hill."

"I'm at the mercy of my interpreter," said Isabel. "But I thought"—her eyes went out upon the skyline again—"I thought that men—that men—I thought that men—My dear, you've made me forget what I thought!"

They laughed, all three. Isabel, with a playful sigh, clutched her mother's hand, and the pair drew off and moved away to the bench.

"He puts you in good spirits," said the mother, breaking a silence.

"Good spirits! He puts me in pure heartache. Oh, why did you tell him?"

"Tell him? My child! I have not told him!"

"Oh, mother, do you not see you've told him point-blank that it's all settled?"

"No, dearie, no! I only see that your distress is making you fanciful. But why should he not be told, Isabel?"

"I'm not ready! Oh, I'm not ready! It may suit him well enough to hear it, for he knows Leonard is too fine and great for me; but I'm not ready to tell him."

"My darling, he knows you are good enough for any Leonard he can bring."

"Oh yes, on the plane of the Ten Commandments." The girl smiled unhappily.

"But precious, he loves Arthur deeply, and thinks the world of him."

"Mother, what is it like, to love deeply?"

The query was ignored. "And the old gentleman is fond of you, sweetheart."

"Oh, he likes me. What a tame old invalid that word 'fond' has grown to be! You can be fond of two or three persons at once, nowadays. My soul! I wish I were fond of Arthur Winslow in the old mad way the word meant when it was young!"

"Pshaw, dearie! you'll be fond enough of him, once you're his. He's brilliant, upright, loving and lovable. You see, and say, he is so, and I know your fondness will grow with every day and every experience, happy or bitter."

"Yes.... Yes, I could not endure not to give my love bountifully wherever it rightly belongs. But oh, I wish I had it ready to-day,—a fondness to match his!"

"Now, Isabel! Why, pet, thousands of happy and loving wives will tell you"—

"Oh, I know what they will tell me."

"They'll not tell you they get along without love, dearie. But ten years from now, my daughter, not how fond you were when you first joined hands, but what you have"—

"Oh yes,—been to each other, done for each other, borne from each other, will be the true measure. Oh, of course it will; but there's so much in the right start!"

"Beyond doubt! Understand me, precious: if you have the least ground to fear"—

"Mother! mother! No! no! What! afraid I may love some one else? Never! never! Oh, without boasting, and knowing what I am as well as Leonard Byington knows"—

"Oh, pshaw! Leonard Byington!"

"He knows me, mother,—as if he lived at a higher window that looked down into my back yard." The speaker smiled.

"Then he knows," exclaimed the mother, "you're true gold!"

"Yes, but a light coin."

"My pet! He knows you're the tenderest, gentlest dear he ever saw."

"But neither brave nor strong."

"Oh, you not brave! you not strong! You're the lovingest, truest"—

"Only inclined to be a bit too hungry after sympathy, dear."

"You never bid for it, love, never."

"Well, no matter; I shall never love any one but myself too much. I think I shall some day love Arthur as I wish I could love him now. I never did really love Leonard,—I couldn't; I haven't the stature. That was my trouble, dearie: I hadn't the stature. I never shall have; and if it's he you are thinking of, you are wasting your dear, sweet care. But he's going to be our best and nearest friend, mother,—he and Ruth and Godfrey, together and alike. We've so agreed, Arthur and I. Oh, I'm not going to come in here and turn the sweet old nickname of this happy spot into a sneer."

"Then why are you not happy, precious?"

"Happy? Why, my dear, I am happy!"

"With touches of heartache?"

"Oh, with big wrenches of heartache! Why not? Were you never so?"

"I'm so right now, dearie. For after all is said"—

"And thought that can't be said"—murmured Isabel.

"Yes," replied the mother, "after all is said and thought, I should rather give you to Arthur than to any other man I know. Leonard will have a shining career, but it will be in politics."

"I tried to dissuade him," broke in the daughter, "till I was ashamed."

"In politics," continued Mrs. Morris,—"and Northern politics, Isabel. Arthur's will be in the church!"

"Yes," said the other, but her whole attention was within the fence at their side, where a rough stile, made in boyhood days by the two brothers and Leonard, led over into the garden. She sprang up. "Let's go, mother; he's coming!"

"Who, my child?"

"Both! Come, dear, come quickly! Oh, I don't know why we ever came out at all!"

"My dear, it was you proposed it, lest some one should come in!"

The daughter had moved some steps down the road, but now turned again; for Ruth and Godfrey, returning, came out through the garden's high gateway. However, they were giving all their smiles to the greetings which the General sent them from his piazza.

"Come over, mother!" called Isabel, in a stifled voice. "Cross to the hill path!" But before they could reach it Arthur and Leonard came into full view on the stile. Isabel motioned her mother despairingly toward them, wheeled once more, and with a gay call for Ruth's notice hurried to meet her in the middle of the way.

Godfrey passed over to the General, who had walked down to his gate on his way to the great elm. Out from behind the elm came the other two men, Arthur leading and talking briskly:—

"The sooner the better, Leonard. Now while my work is new and taking shape—Ah! here's Mrs. Morris."

Both men were handsome. Arthur, not much older than Ruth, was of medium height, slender, restless, dark, and eager of glance and speech. Leonard was nearer the age of Godfrey; fairer than Arthur, of a quieter eye, tall, broad-shouldered, powerful, lithe, and almost tamely placid. Mrs. Morris met them with animation.

"Have our churchwarden and our rector been having another of their long talks?"

The joint reply was cut short by Godfrey's imperative hail: "Leonard!"

As Byington turned that way, Arthur said quietly to Mrs. Morris, "He's promised to retain charge"—and nodded toward Isabel. The nod meant Isabel's financial investments.

"And mine?" murmured the well-pleased lady.

"Both."

The two gave heed again to Godfrey, who was loudly asking Leonard, "Why didn't you tell us the news?"

"Oh," drawled Leonard smilingly, "I knew father would."

"I haven't talked with Godfrey since he came," said Mrs. Morris; and as she left Arthur she asked his brother: "What news? Has the governor truly made him"—

"District attorney, yes," said Godfrey. "Ruth, I think you might have told me."

"Godfrey, I think you might have asked me," laughed the girl, drawing Isabel toward Arthur and Leonard, in order to leave Mrs. Morris to Godfrey.

Arthur moved to meet them, but Ruth engaged him with a question, and Isabel turned to Leonard, offering her felicitations with a sweetness that gave Arthur tearing pangs to overhear.

"But when people speak to us of your high office," he could hear her saying, "we will speak to them of your high fitness for it. And still, Leonard, you must let us offer you our congratulations, for it is a high office."

"Thank you," replied Leonard: "let me save the congratulations for the day I lay the office down. Do you, then, really think it high and honorable?"

"Ah," she rejoined, in a tone of reproach and defense that tortured Arthur, "you know I honor the pursuit of the law."

Leonard showed a glimmer of drollery. "Pursuit of the law, yes," he said; "but the pursuit of the lawbreaker"—

"Even that," replied Isabel, "has its frowning honors."

"But I'm much afraid it seems to you," he said, "a sort of blindman's buff played with a club. It often looks so to the pursued, they say."

Isabel gave her chin a little lift, and raised her tone for those behind her: "We shall try not to be among the pursued, Ruth and Arthur and I."

The young lawyer's smile broadened. "My mind is relieved," he said.

"Relieved!" exclaimed Isabel, with a rosy toss. "Ruth, dear, here is your brother in distress lest Arthur or we should embarrass him in his new office by breaking the laws! Mr. Byington, you should not confess such anxieties, even if you are justified in them!"

His response came with meditative slowness and with playful eyes: "Whenever I am justified in having such anxieties, they shall go unconfessed."

"That relieves my fears," laughed Isabel, and caught a quick hint of trouble on Arthur's brow, though he too managed to laugh. Whereupon, half sighing, half singing, she twined an arm in one of Ruth's, swung round her, waved to the General as he took a seat on the elm-tree bench, and so, passing to Arthur, changed partners.

"Let us go in," whispered Leonard to his sister, with a sudden pained look, and instantly resumed his genial air.

But the uneasy Arthur saw his moving lips and both changes of countenance. He saw also the look which Ruth threw toward Mrs. Morris, where that lady and Godfrey moved slowly in conversation,—he ever so sedate, she ever so sprightly. And he saw Isabel glance as anxiously in the same direction. But then her eyes came to his, and under her voice, though with a brow all sunshine, she said, "Don't look so perplexed."

"Perplexed!" he gasped. "Isabel, you're giving me anguish!"

She gleamed an injured amazement, but promptly threw it off, and when she turned to see if Leonard or Ruth had observed it they were moving to meet Godfrey. Mrs. Morris was joining the General under the elm.

"How have I given you pain, dear heart?" asked Isabel, as she and Arthur took two or three slow steps apart from the rest, so turning her face that they should see its tender kindness.

"Ah! don't ask me, my beloved!" he warily exclaimed. "It is all gone! Oh, the heavenly wonder to hear you, Isabel Morris, you—give me loving names! You might have answered me so differently; but your voice, your eyes, work miracles of healing, and I am whole again."

Isabel gave again the laugh whose blithe, final sigh was always its most winning note. Then, with tremendous gravity, she said, "You are very indiscreet, dear, to let me know my power."

His face clouded an instant, as if the thought startled him with its truth and value. But when she added, with yet deeper seriousness of brow, "That's no way to tame a shrew, my love," he laughed aloud, and peace came again with Isabel's smile.

Then—because a woman must always insist on seeing the wrong side of the goods—she murmured, "Tell me, Arthur, what disturbed you."

"Words, Isabel, mere words of yours, which I see now were meant in purest play. You told Leonard"—

"Leonard! What did I tell Leonard, dear?"

"You told him not to confess certain anxieties, even if they were justified."

"Oh, Arthur!"

"I see my folly, dearest. But Isabel, he ought not to have answered that the more they were justified, the more they should go unconfessed!"

"Oh, Arthur! the merest, idlest prattle! What meaning could you"—

"None, Isabel, none! Only, my good angel, I so ill deserve you that with every breath I draw I have a desperate fright of losing you, and a hideous resentment against whoever could so much as think to rob me of you."

"Why, dear heart, don't you know that couldn't be done?"

"Oh, I know it, you being what you are, even though I am only what I am. But, Isabel, you know he loves you. No human soul is strong enough to blow out the flame of the love you kindle, Isabel Morris, as one would blow out his bedroom candle and go to sleep at the stroke of a clock."

"Arthur, I believe Leonard—and I do not say it in his praise—I believe Leonard can do that!"

"No, not so, not so! Leonard is strong, but the fire of a strong man's love, however smothered, burns on without mercy, my beautiful, and you cannot go in and out of that burning house as though it were not on fire."

"And shall Leonard, then, not be our nearest and best friend, as we had planned?"

"He shall, Isabel. Ah yes; not one smallest part of your sweet friendship will I take from him, nor of his from you. For, Isabel, though he were as weak as I"—

"As weak as I, you should say, dear. You are not weak, Arthur, are you?"

"Weak as the bending grass, Isabel, under this load of love. But though he, I say, were as weak as I, you—ah, you!—are as wise as you are bewitching; and if I should speak to you from my most craven fear, I could find but one word of warning."

"Oh, you dear, blind flatterer! And what word would that be?"

"That you are most bewitching when you are wisest."

As Isabel softly laughed she cast a dreaming glance behind, and noticed that she and Arthur were quite hidden in the flowery undergrowth of the hill path. They kissed.

"Beloved," said her worshipper, with a clouded smile, as he let her down from her tiptoes, "do you know you took that as though you were thinking of something else?"

"Did I? Oh, I didn't mean to."

Such a reply only darkened the cloud. "Of whom were you thinking, Isabel?"

She blushed. "I was think—thinking—why, I was—I—I was think—thinking"—she went redder and redder as he went pale—"thinking of everybody on Bylow Hill. Why—why, dear heart, don't you see? When you"—

"Oh, enough, enough, my angel! I take the question back!"

"You made me think of everybody, Arthur, you were so sudden. Just suppose I had done so to you!" They both thought that worthy of a good laugh. "Next time, dear," added Isabel,—"no, no, no, but—next time, you mustn't be so sudden. There's no need, you know,"—she blushed again,—"and I promise you I'll give my whole mind to it! Get me some of that hawthorn bloom yonder, and let's go back."

This "hill path" was a narrowed continuance of the street, that led gradually down along the hill's steep face to reach the town and the river meadows. Godfrey, halting before Ruth and her brother, watched the blooming hawthorn, over there, bend and shake and straighten and bend again, above Arthur's unseen hands. Then, glancing furtively back toward Mrs. Morris, he muttered to Ruth, while Leonard gravely looked out across the landscape, "I live and learn."

"So we learn to live," was Ruth's playful reply. To her it was painfully clear that Mrs. Morris, very sweetly no doubt, had eluded Godfrey's endeavors to inform her of anything not to his brother's unqualified praise. In the Bylow Hill group, Ruth had a way of smiling abstractedly, which was very dear to Godfrey even when it meant he had best say no more; and this smile had just said this to him when Isabel and Arthur came into view again. As the two and the three drifted toward each other, Ruth let Leonard outstep her, and joined Godfrey with a light in her face that quickened his pulse.

After a word or two of slight import she said, as they slowly walked, "Godfrey."

"Yes," eagerly responded the lover.

"Down in the garden, awhile ago—did I—promise something?"

"You most certainly did!" She had promised that if he would let a certain subject drop she would bring it up again, herself, before he must take his leave.

"And must you go very soon, now?" she asked.

"I've only a few minutes left," said the lover, with a lover's license.

"Well, I'm ready to speak. Of course, Godfrey, I know my heart."

The young man smiled ruefully. "I've known mine till I'm dead tired of the acquaintance."

Other words passed, her eyes on the ground as they loitered, and after a pause she murmured:—"But I've known my heart as long as you've known yours."

"You've known—What do you—Oh, Ruth, look at me!"

She looked, very tenderly, although she said, "You forget we are observed."

"Oh, observed! Do you mean hope—for me—after all?"

"I mean that if you will only wait until we can get a clear light on this matter of Isabel's—which will most likely be by the next time you come"—

"Oh, Ruth, Ruth, my own Ruth at last!"

"Please don't speak so. I'm not engaging myself to you now."

"Oh yes, you are! Yes, you are! Yes—you—are!"

"No—no—no—listen! Listen to me, Godfrey. I think that now, among us all, we shall manage Isabel's affair well enough, and that the very next time—you—come"—She began absently to pick her steps.

"What—what then?"

"Then you may ask me."

The response of the overjoyed lover was but one or two passionate words, and her sufficient reply, as they halted among their fellows, was to look across the valley with her meditative smile. Isabel took note, but kindly gave a long sigh of admiration, and with an exalted sweep of the hand drew the gaze of the five to the beauties of the scene below. The day was near its end. The long shadow of the great cliff behind Bylow Hill hung over the roofs of the town and over the hither meadows. The sun's rays were laying their last touches upon the winding river, and upon the grainfields that extended from its farther shore. In the upper blue rested a few peaceful clouds, changing from silver to pink, from pink to pearly gray, and on the skyline crouched in a purpling haze the round-backed mountains of another county.

To Mrs. Morris and the General the sight, from the old elm-tree seat, was even fairer than to the youthful group whose forms stood out against the sky, the floral colors of the girls' draperies heightened by the western light. For a while the two sitters gave the perfect scene the tribute of a perfect silence, and then the General asked, as he cautiously straightened his impaired frame, "Has not Isabel been making some—eh—news for herself—and us?"

The lady's lips parted for their peculiar laugh of embarrassment, but the questioner's smile was so serious that she forced her sweetest gravity. "Why, General, according to our Southern ways," she said,—every word mellowed by her Southern way of saying it,—"that's for Isabel to tell you."

"Then why does she not do it, Mrs. Morris?" asked the veteran, who had been district attorney himself once upon a time, and was clever with witnesses.

"Why, really, General, Isabel hasn't had a cha—Oh! ho, ho! I oughtn't to have said that!" Mrs. Morris had a killing dimple, but never used it.

"I suppose—of course"—said the General, "she will say it's—eh—Arthur?"

"Now you're making me tell," she laughed, "and I mustn't! General, Godfrey seems to be going."

In fact, Godfrey was shaking hands with Ruth and Leonard. Now he took the hands of Arthur and Isabel together, and Mrs. Morris laughed more sweetly and with more oh's and ho's than ever; for Isabel sedately kissed Arthur's brother.

Ruth made signs to her father, who answered them in kind. "What does she say, Mrs. Morris? Can you hear?"

"She says they're singing 'your hymn' down in a church under the hill."

"Ah yes." He beamed and nodded to Ruth; but when Mrs. Morris once more laughed, his brow clouded a trifle. "Your daughter, Mrs. Morris"—

The lady broke in with a note of bright surprise, rose, and took an unconscious step forward. The five young friends were advancing in a compact cluster, with measured pace. Ruth and Isabel, in front abreast, and making happy show of the hawthorn sprays, were just enough apart to conceal, except for their superior height, the three lovers, and in lowered tones, but with kindling eyes, the five, incited by Ruth, were singing the song they had caught up from the valley,—the old man's favorite from the days of his own song-time. The General got himself hurriedly to his feet; the shade passed from his brow. The group came close; he stepped out, and Isabel, meeting him, laid her two hands in his, while the halting cluster ceased their song suspensively on a line that pledged loves and friendships too ethereal to clash.

"Isabel,"—he turned up a broadened palm,—"here's my amen to that line; where's yours?"

With blushing alacrity she laid her hand on his.

"Arthur!" he called, and the lively lover added his to the two. "Now, Ruth!"

"Father!" laughed the daughter, "isn't this rather youngish?" But she laid her hand promptly upon Arthur's, and the lines of the General's face deepened playfully, and Mrs. Morris's dimple did the same, as Godfrey thrust his hand in upon Ruth's, unasked. The matron laughed very tenderly on the key of O while she added her hand, and received Leonard's heavy palm above it. Then Arthur clapped a second hand upon Leonard's, and Leonard was about to lay a second quietly upon Arthur's, when Isabel, rose-red from brow to throat, gayly broke the heap and embraced Ruth.

"Well, honey-girlie," said Mrs. Morris, as she and Isabel reentered their cottage, "wasn't it sweet of them all, that 'laying on of hands,' as Arthur called it?"

"Yes," replied the Southern girl, starting up the cramped old New England stairway to her room. "It was child's play, but it was very sweet of them, and especially of the General."

The mother detained her fondly. "And still, my child, you're not satisfied?"

"Ah, mother, are you blind, stone blind, or do you only hope I am?"

"My dearie!"

"Why, mother, excepting Leonard, we haven't had one word of true consent from one of them."

"Oh, now, Isabel! They'll all be glad enough by and by."

"Yes," said the daughter, from the landing above, "I've no doubt of that."

She passed into her room, closed the door, and standing in the middle of the floor, with her temples in her palms, said, "O merciful God! Oh, Leonard Byington, if only that second hand of yours had hung back!"

Arthur and Isabel were married in their own little church of All Angels, at the far end of the old street.

"I cal'late," said a rustic member of his vestry, "th' never was as pretty a weddin' so simple, nor as simple a weddin' so pretty!"

Because he said it to Leonard Byington he ended with a manly laugh, for by the anxious glance of his spectacled daughter he knew he had slipped somewhere in his English. But when he heard Leonard and Ruth, in greeting the bride's mother, jointly repeat the sentiment as their own, he was, for a moment, nearly as happy as Mrs. Morris.

"Such a pity Godfrey had to be away!" said Mrs. Morris. It was the only pity she chose to emphasize.

Godfrey was on distant seas. The north-bound mid-afternoon express bore away the bridal pair for a week's absence.

"Too short," said a friend or so whom Leonard fell in with as he came from the railway station, and Leonard admitted that Arthur was badly in need of rest.

At sunset Ruth came out of her gate and stood to welcome her brother's tardy return. Both brightly smiled; neither spoke.

When he gave her a letter with a foreign stamp her face lighted gratefully, but still without words she put it under her belt. Then they joined hands, and he asked, "Where's father?"

"Inside on the lounge," she replied. Her lips fell into their faraway smile, to which she added this time a murmur as of reverie, and Leonard said almost as musingly, "Come, take a short turn."

They moved on to the Winslow gate, and entered the garden by a path which brought them to a point midway between the old cottage and the larger house. There it crossed under an arch transecting an arbor that extended from a side door of the one dwelling to a like one of the other, and the brother and sister had just passed this embowered spot and were stepping down a winding descent by which the path sought the old mill-pond, when behind them they observed two women pass athwart their track by way of the arbor, and Ruth smiled and murmured again. The crossing pair were Mrs. Morris and Sarah Stebbens, the Winslows' life-long housekeeper, deeply immersed in arranging for Isabel to become lady of the larger house, while her mother, with a single young maidservant, was to remain mistress of the cottage.

The deep pond to whose edge Leonard and Ruth presently came was a narrow piece of clear water held in between Bylow Hill and the loftier cliff beyond by an old stone dam long unused. Rude ledges of sombre rock underlay its depths and lined and shelved its sides. Broad beeches and dark hemlocks overhung it. At every turn it mirrored back the slanting forms of the white and the yellow birch, or slept under green mantles of lily pads. It bore a haunted air even in the floweriest days of the year, when every bird of the wood thrilled it with his songs, and it gave to the entire region the gravest as well as richest note among all its harmonies. Down the whole way to it some one long gone had gardened with so wise a hand that later negligence had only made the wild loveliness of this inmost refuge more affluent and impassioned.

At one point, where the hemlocks hung farthest and lowest over the pool, and the foot sank deep in a velvet of green mosses, a solid ledge of dark rock shelved inward from the top of the bank and down through the flood to a depth cavernous and black. Here, brought from time to time by the Byington and Winslow playmates, lay a number of mossy stones rounded by primeval floods, some large enough for seats, some small; and here, where Ruth had last sat with Godfrey, she now came with her brother.

The habitual fewness of Leonard's words was a thing she prized beyond count. It made Mrs. Morris nervous, drained her mind's treasury, and sent her conversational powers borrowing and begging; Isabel it awed; Arthur it tantalized; to Godfrey it was an appetizing drollery; but to Ruth it was dearer and clearer than all spoken eloquence.

The same trait in her, only less marked, was as satisfying to him, and from one rare utterance to another their thoughts moved like consorted ships from light to light along a home coast. A motion, a glance, a gleam, a shade, told its tale, as across leagues of silence a shred of smoke may tell one dweller in the wilderness the way or want of another. Such converse may have been a mere phase of the New Englander's passion for economy, or only the survival of a primitive spiritual commerce which most of us have lost through the easier use of speech and print; but the sister took calm delight in it, and it bound the two to each other as though it were itself a sort of goodness or greatness.

"They have it of their mother," the old General sometimes said to himself.

There were moments, too, when their intercourse was still more subtle, and now they sat without exchange of glance or gesture, silent as chess players, looking up the narrow water into a sunset exquisite in the delicacy of its silvery plumes, fleeces pink and dusk, and illimitable distances of palest green seen through fan-rays of white light shot down from one dark, unthreatening cloud.

"Leonard," at length said the sister, as if she had studied every possibility on the board before touching the chosen piece, "couldn't you go away for a time?"

And with deliberate readiness the other gentle voice replied, "I don't think I'd better."

While they spoke their gaze rested on the changing beauties of pool and sky, and after the brief inquiry and response it still remained, though the inner glow of their mutual love and worship deepened and warmed as did the colors of the heavens and of the glassing waters. The brother knew full well Ruth's poignant sense of his distresses; and to her his mute tongue and unbent head were a sister's convincement that he would endure them in a manner wholly faithful to every one of the loved hands that had lain under his the evening Godfrey had said good-by.

Indeed, it was clear that to go away—unless he honestly felt too weak to remain—would be unfair to almost every person, every interest, concerned; and such a step was but second choice in Ruth's mind, conditioned solely on any unreadiness he might have uprightly to bear the burden brought upon him by—well, after all, by his own too confident miscalculations in the game of hearts.

To him such flight signified the indeterminate continuance of his sister's maiden singleness and a like prolongation of her lover's galling suspense. To Ruth it stood not only for the loss of her brother, but for the narrowing of their father's already narrowed life,—a narrowing which might come to mean a shortening as well; and it meant also the leaving of Isabel and Arthur to their mistake and to their unskilfulness slowly and patiently to work out its cure. To go away were, for him, to consent to be the one unbroken string on a noble but difficult instrument. These thoughts and many more like them passed to and fro, out through the abstracted eyes of the one, across to the fading clouds, and back through the abstracted eyes and into the responding heart of the other.

At length the sister rose. "I must go to father," she said.

The brother stood up. Their eyes exchanged a gentle gaze and tenderly contracted.

"I will come presently," he replied, and was turning toward the water, when he paused, threw a hand toward the steep wood across the pool, and silently bade her listen.

The note he had remotely heard was rare on Bylow Hill since the town had come in below, and one of the errands which oftenest brought the hill's dwellers to this nook in solitary pairs was to hearken for that voice of unearthly rapture,—a rapture above all melancholy and beyond all mirth,—the call of the hermit thrush.

Now the waiting seemed in vain. The brother's hand sank, the sister turned, and soon he saw her pass from view among the boughs as she wound up the rambling path toward the three homes.

At the top she halted, still longing to hear at his side that marvellous wood-note, and was just starting on once more, when from the same quarter as before it came again, with new and fervent clearness. With noiseless foot she sprang back down the bendings of the path, having no other thought but to find her brother standing as she had left him, a rapt hearer of the heavenly strain.

She reached the spot, but found no hearkening or standing form. The young man's stalwart frame lay prone on the green bank, where he had thrown himself the moment she had left his sight, and his face was buried in the deep moss.

The stir of her swift coming reached his ear barely in time for him, as she choked down a cry that had all but escaped her, to turn upon his back, meet her glance, and drive the agony from his face with a languorous smile. The melting song pervaded the air, but neither of them lifted a noting finger.

Leonard rose to his feet. Ruth gave him a hand and then its fellow, and as he pressed them together she said, "I wish you would go away for a time."

He dropped one of her hands, and keeping the other, started slowly homeward; and it was not until they had climbed half the ascent that, with his most remote yet boyish smile, he replied, "I don't think I'd better."

August, September, October, November,—so passed the year in gorgeous recession over Bylow Hill. Among their dismantled trees the three homes stood unveiled to the town on the meadows and to travellers who looked from train windows while crossing the river bridge. To those who inquired whose they were there was always some one more than ready to give names and details, and to tell how perfect a bond ever had been—how beautiful a fellowship was yet, now—up there.

Sevenfold they called it, although one of the seven was away; namely, Lieutenant Godfrey Winslow, of the navy, famed for his splendid behavior in the late so-and-so affair. That stately house at the right, they said, was his home what brief times the sea was not.

There lived, it would be added, his younger brother, so rapidly coming into note,—the eccentric but gifted rector of All Angels; whose great success in the heart of a Congregational community was due hardly more to his high talents than to the combined winsomeness and practical sympathies of his beautiful bride, or to the resourceful wisdom and zeal of his churchwarden, Leonard Byington.

"Any relation to Byington, your new political leader in these parts?"

"Same man," the answer would be, and there the narrator was sure to fall into a glowing tribute to the ideal companionship existing between the rector, his bride, the young district attorney, and Ruth Byington.

What made this intimacy the more interesting was, in the eyes of a growing number of observers, that, as they said, "Arthur Winslow was not always an affable man, and was much more rarely a happy one."

Behind and above this popular verdict was that of the old street behind and above the town,—a sort of revised version, a higher criticism. If the young rector, this old street explained, oftener looked anxious than complacent, so in their time, most likely, did St. Paul and St. Peter. If he was not always affable, why, neither are volcanoes; the man was all molten metal within. Anyhow, he filled his church to the doors.

Coaching parties of the vastly rich made the town their Sunday stopping place purely to hear him; not so much because the boldness of his speculations kept his bishop frightened as because he always fused those speculations on, white-hot, to the daily issues of private and public life, in a way to make pampered ladies hold their breath, and men of the world their brows. Such a man, to whom the least sin seemed black and bottomless, yet who appeared to know by experience the soul's every throe in the foulest crimes, was not going to show his joys on the surface in quips and smiles.

"You should have heard," said the old street, "his sermon to husbands and wives! His own bride turned pale. He turned pale himself."

It was wonder enough that even the bride could be happy, at such an altitude, so to speak; immersing herself utterly, as she did, in the interests that devoured him. All Angels forgot his gloom in the radiance of her charms,—the sweet genuineness of her formal pieties, the tender glow and universality of her sympathies, the witchery of her ever ready, never too ready playfulness. It was captivating to see how instantly and entirely she had fitted herself into a partnership so exacting; though it was pitiful to note, on second glance, how the tint and contour of her cheek were losing their perfection, and her eyes were showing those rapid alternations of languor and vivacity which story-tellers call a "hunted look." Yet, oh, yes, she was happy; the pair were happy. It was as a pair that they were happiest. Else, said the old street, they could not keep up the old Winslow-Byington alliance so beautifully.

To the truth of this general outline the three homes' domestics, dominated by Sarah Stebbens, certified with cordial and loyal brevity. Yet when Ruth wrote Godfrey how well things were going, there lurked between her bright lines one or two irrepressible meanings that locked his jaws till they creaked.

In fact, both his brother and hers were "ailing." Both carried a jaded, almost a broken look, and Arthur was taking things to make him eat and sleep; while Leonard had daily accepted more and more of the young rector's complicating cares, until he was really the parish's chief burden-bearer.

"No," he said to his father, "Arthur carries his whole work manfully on his own shoulders."

"But, my son," replied the old General, "don't you see you're carrying Arthur?"

"No, I sha'n't do that," dryly responded the son; but Ruth saw a change on his brow as on that of a guide who fears he has missed the path.

The four young friends spent many delightful evenings together in the Winslow house, with Mrs. Morris and the General on one side at cribbage. Ruth had frequent happy laughs, observing Isabel's gift for making Leonard talk. It gave her a new joy in both of them to have the lovely hostess draw him out, out, out, on every matter in the wide arena to which he so vitally belonged; eliciting a flow of speech so animated that only afterward did one notice how dumb as any tree on Bylow Hill he had been in regard to himself.

"They are bow and violin," said Arthur to Ruth, with his dark, unsmiling face so free from resentment that she gratefully wondered at him, and was presently ashamed to find herself asking her own mind if he was growing too subtle for her.

On these occasions Isabel was wont to court Ruth's counsel concerning her wifely part in Arthur's work, thus often getting Leonard's as well. Sometimes she impeached his masculine view of things, in her old skirmishing way. Then she would turn rose-color once more and mirthfully sigh, while Ruth laughed and wished for Godfrey, and Mrs. Morris breathed soft ho-ho's from the cribbage board.

So came the Thanksgiving season, with strong, black ice on the mill pond, where the four skated hand in hand. Then the piling snows stopped the skating with a white Christmas, the old year sank to rest, the new rose up, and Bylow Hill, under its bare elms and with the pine-crested ridge at its back, sat in the cold sunshine like a white sea bird with its head in its down. And when the nights were frigid and clear its ruddy lights of lamp and hearth seemed to answer the downward gaze of the stars in silent gratitude for conditions of happiness strangely perfect for this imperfect world, and the town marvelled at the young rector's grasp of his subject when his text was, "The heart knoweth his own bitterness."

But on a day in the very last of winter, when every one was in the thick of all the year's tasks and cares, there came to Leonard this letter:—

LEONARD BYINGTON, ESQUIRE:

SIR,—I find myself compelled to ask that you consider your acquaintanceship with my wife at an end. Doubtless this request will give you more relief than surprise. The visible waste of your frame and the loss of her exquisite bloom are proof enough that both you and she have long been in daily dread of a far worse visitation. It is not worse, because I know how sentimental your impotent and conscience-plagued interchanges of affection have been. I shall permit and assist you to keep this matter a secret. To let it be known would instantly wreck your own career, and would blast at a breath the fortunes of our church and of every one of both our kindreds. I will therefore not at this time require you to resign your church office or to break off those business intimacies with me which, though no longer founded in personal esteem, are vital to interests that common decency must move you to shield from new peril.

I ask for no repair of the inextinguishable wrong you have done me. I only ask you not to fancy that I am to be beguiled by arguments or denials or moved by threats, or that one word I here write is founded on conjecture or inference. Grovelling at my feet, in sobs of shame and with prayers for pardon, Isabel has told me all. Has told me all, Leonard Byington, my once trusted friend. Now, though prostrated on her bed, she rejoices in the double forgiveness of her husband and her priest, blessing him for deliverance from the misleadings of one who—great God! must I write it?—might at last have dragged her into crime. It is her request, as it is my command, that you darken our threshold no more, and that as far as practicable you keep yourself from her sight.

Faithfully,

ARTHUR WINSLOW.

With his swivel-chair overturned behind him the young lawyer stood at the desk of his inner office, read this letter through at headlong speed, turned it again, and re-read it slowly, searchingly, from his own name to its writer's.

Then readjusting his chair he stepped to a door, asked a clerk in the outer office to order his cutter, turned back, and was closing his desk, when his partner came to him.

"Byington, are you ill?" asked the fatherly man.

"No; I'm only going out on some business. I'll be back about—" He looked at his watch.

"Byington, don't go. You're ill. You don't realize how ill you are. If you go at all, go home, and let me send some one with you. Why, your hand is as cold"—

"I'm all right," said the young man, freeing his hand and smiling with white lips. He took his hat and passed out.

Meanwhile Isabel lay on her bed too overwhelmed to rise. In his room adjoining, with doors locked, Arthur paced the floor. He had spent the first half of the night in an agonizing interview with his wife, and the second half in writing and rewriting the letter to Leonard.

Now Isabel noticed the cessation of his steps. In the door between them the key turned; then the door opened, and he stood, haggard and dishevelled, gazing on her. She sat up in the bed, wan, tear-spent, her glorious hair falling over the embroideries of her nightdress.

"Arthur, dear, I am sorry for every angry word I have spoken. But the things I have denied I must deny forever.

"If you should wait till doomsday, I could confess no more.

"I have never harbored one throb of unworthy or unsafe regard toward any man in this wide world.

"For me to say differently would be to lie in God's own face.

"I have had great happiness of Leonard's companionship, and I have been proud to be myself a proof that a man and a woman can be close, dear, daily friends without being lovers or kin, and earth be only more like heaven for it, to them and all theirs. If Leonard has confessed one word more than that for me,—or even for himself, Arthur, dearest,—he has lost his reason. It's a frightful explanation, but I find no other.

"Leonard Byington is not wicked, and if he were he wouldn't be so in a dastard's way.

"Never since the day I first plighted my faith to you, dear heart, has he given me one sign of a lover's love.

"Oh, Arthur, I do love my husband! This night has proved it to me as I never knew it before; and if you will only believe me and go back to Leonard, I believe he can tear the mask off this horrible mystery."

Arthur turned and once more locked the door. His wife flamed red and hearkened, and the light footfall which had tortured her for hours began again. Suddenly she left the bed and hurried to dress.

At the mirror, with her hair lifted on her hands, she paused and again hearkened. Sleighbells stopped at the front door.

Now some one was let in down there, and now, at her husband's room, Giles, his English man of all work, announced Mr. Byington:—

"Yes, sir, but he says if you can't come down 'e will 'ave to come up, sir."

As Arthur entered the library Leonard came from its farther end, and they halted on opposite sides of a large table. Arthur was flushed and looked fearfully spent. Leonard was pale.

"I have your letter, Arthur."

The rector bowed. He gave a start, but tried to conceal a gleam of triumph.

Leonard ignored it and spoke on:—

"A gentleman, Arthur,—I mean any one trying to be a whole gentleman,—is a very helpless creature, nowadays, in matters of this sort."

He looked formidable, and as he lightly grasped a chair at his side it seemed about to be turned into a weapon.

"The old thing once called satisfaction," he continued, "is something one can no longer either ask or offer, in any form. He can neither rail, nor strike, nor spellbind, nor challenge, nor lampoon, nor prosecute."

"Nearly as helpless as a clergyman," said Arthur.

"Almost," replied the visitor. "No, there is no more satisfaction in any of those things, for him, than if he were all a clergyman is supposed to be. There is none even in saying this, to you, here, now, and I'm not here to say it. Neither am I here to vindicate myself—no, nor yet Isabel—with professions or arguments to you; I might as well argue with a forest fire."

"Quite as well. What are you here for?"

"Be patient and I'll tell you; I'm trying to be so with you."

"You—trying"—

"Stop that nonsense, Arthur. Ah me, Arthur Winslow, I have no wish to humiliate you. Through the loyalty of your wife's pure heart, whatever humiliates you must humiliate her. Oh, I could wish her in her shroud and coffin rather than have her suffer the humiliation you have prepared for yourself and for her through you."

Arthur showed a thrill of alarm. "Do you propose to go down to public shame and drag us all with you?"

"No, nor to let you, if I can prevent you. Arthur, you have allowed a base jealousy to persuade you, in the face of every contrary evidence, that your fair young wife has lost her loyalty—and your nearest friend the commonest honesty—in a clandestine love. Under the goadings of that passion you have foully guessed, have heartlessly accused, have brazenly lied. Isabel has confessed nothing to you, and I know by your lies to me how pusillanimously you must have been lying to her. Had your guess been right, I should not have known you were only guessing, and your successful iniquity would have remained hidden from everybody but yourself—I still do you the honor to believe you would have realized it. Now the vital question is, do you realize it, and will you undo it?"

Arthur was deadly pale; his pointing finger trembled. "Leave"—he choked—"leave this house."

Leonard turned scarlet, but his tone sank low. "Arthur, I don't believe your soul is rotten. If I did, I should not be such a knave or such a fool as to make any treaty with you that would leave you in your pulpit one Sabbath Day."

"What do you—what do you mean by that?"

"I mean that such a treaty would be foul faith to everybody."

"So, then, you do propose one common shipwreck for us all."

"Quite the contrary. To trust the fortunes of our loved ones to any treaty with a rotten soul would indeed be to launch them upon a stormy sea in a rotten boat. But I do not believe your soul is so. I believe it is sound,—still sound, though on fire; and so, to help you quench its burning, I give you my pledge to be from this day a stranger to your sweet wife. And now will you do something for me, to prove that your soul is sound and is going to stay sound? It shall be the least I can ask in good faith to the world we live in."

"What is it?" asked Arthur. There was no capitulation in his face or his voice.

"I want you to make to Isabel a full retraction and explanation of every falsehood you have uttered to her or to me in this matter." Leonard was pale again; Arthur burned red a moment, and then turned paler than Leonard.

"You fiend!" gasped the husband. "I am to exalt you, and abase myself, to her?"

"No. No, Arthur. Women are strange; every chance is that in her eyes I shall be abased." The speaker went whiter than ever.

"But be that as it may, you shall have lifted your soul out of the mire. You must do it, Arthur; don't you see you must?"

Arthur sank into the chair at his side. He seemed to have guessed what Leonard was keeping unsaid. A moisture of anguish stood on his brow. Yet—

"I will die before I will do it," he said.

Leonard drew forth the letter, and then his watch. "Arthur Winslow, I give you five minutes. If you don't make me that promise in that time, I shall this day show this letter to your bishop."

The rector sat clenching his fingers and spreading them again, and staring at the table.

A bead of sweat, then a second, and then a third started down his forehead.

Presently he clutched the board, drew himself to his feet, and turned to leave the chair, but fell across its arms, slid heavily from them, and with one rude thump and then another lay unconscious on the floor.

Leonard sprang round the table, but when he would have lifted the fallen head it was in the arms of Isabel, and her dilated eyes were on him in a look of passionate aversion.

"Ring!" she cried. "Ring for Sarah—and go!

"No! stop! don't ring! he's coming to! Only go! go quickly and forever! Say not a word,—oh, not a word! I heard it all! Despise me too, for I listened at the door!

"Oh, my husband! Arthur, look at me, Arthur. Look, Arthur; it's your Isabel. Oh, Arthur, my husband, my husband!"

Martin Kelly, pious Irishman and out-door factotum of the Byington place, paused from the last snow-shovelling of the season to reply to a wandering salesman of fruit trees.

"Mr. Airthur Winslow or Mr. Linnard Boyington,—naw, sor! ye can see nayther the wan nor th' other, whatsomiver! How can ye see thim, moy graciouz! whin 'tis two weeks since the two o' thim was tuck the same noight wid the pneumonias, boy gorra! and the both of thim has thim on the loongs!"

The nursery agent asked how it had happened so.

"Hawh! ask yer grandmother! All ye can say is they was roipe to catch the maladee, whatsomiver! Ye cannot always tell how 'tis catched, and whin ye cannot tell, moy graciouz! ye have got the wurrst koind!"

The two sick men recovered very nearly at the same time.

One day when Leonard had read all his accumulated mail and had seen three or four men officially in his bedchamber, he told Ruth that a certain criminal case, the trial of which had been waiting for his recovery, would take him to the county-seat, and would keep him there many days, probably weeks, except for brief visits to his office and yet briefer moments at home.

Ruth gave him a look of tender approval, laid a hand in his, and bent into the evening fire her far-off smile. Thus, and only thus, he knew she had divined what had befallen.

A day or two afterward Mrs. Morris brought him a note from Arthur. He wrote an answer while she stayed, and while Ruth listened elatedly to her sprightly account of how well Isabel still bore the burden of nursing a most loving but most nervous husband.

The missive from Arthur was a short but complete and propitiative acknowledgment of his error and fraility. It offered no change in the agreement as to Isabel, but it professed a high yet humble resolve to fall no more, and it ended with a manly offer to resign his pulpit, and even to lay aside his sacred calling, if Leonard retained any belief in the moral necessity of his so doing.

Leonard's reply was a very brief exhortation to his friend to put away all thought of resigning, and to take up his work again with the zeal with which he had first entered upon it.

Mrs. Morris went away refreshed, and left the Byingtons equally so. Her buoyancy had been as prettily restrained, her sympathies as sweet, her dimple as unconscious, her belief in everybody's wit and wisdom except her own as genuine, and her timid dissimulations as kindly meant and as transparent, as ever. Yet there was an unspoken compassion for her when she was gone, for in the parting words with which she playfully vaunted her ignorance of the correspondence she was bearing, it was clear, even to the General, that behind that small ignorance she had a larger knowledge,—a fact that made her dainty cheerfulness seem very brave.

The freshets swept down the valleys, the myriad yellow twigs of the brookside willows turned green, a cheery piping rose from the ponds, the last gleam of snow passed from the farthest hills, the bluebird sang, the harrow followed the plough, Ruth's crocuses shone above the greening sod, and down by the old mill-pool and on the steep hillside beyond it she and Isabel gathered arbutus, anemones, and the yellow violet. Spring had come.

Then through the thickening greenery the dogwood shone like belated drifts, the flashing warblers passed on into the north, the bobolink had arrived, the robin was already overeating, the whole chorus of birds that had come to nest and stay broke forth, and it was summer.

Leonard was back in his own town, enriched with new esteem from the public and from the men of his profession. The noted case was won, a victory for the peace and dignity of the state, due wholly, it was said, to the energy and sagacity of the young district attorney. A murder had been so cunningly done that suspicion could fasten nowhere, until Byington laid his finger upon a man of so unspotted a name that no one else had had the mental courage to point to him. Through a long and masterly untangling of contradictions the state's counsel had so overwhelmingly proved him guilty that he had confessed without waiting for the jury's verdict.

"Yes," said many, "it was a great stroke, Leonard's management of that thing." And not a few added that it had made him an older man—"that or something." Those who were of his politics, and even some who were not, stopped him in Main Street and State Street to "shake" and to say, without too much care for logical sequence, how soon, in their opinion, he would be the commonwealth's "favorite son."

"My dear Mrs. Morris," said the General, "every town has at least one." But even Mrs. Morris could see the father's faith and pride through the old soldier's satire.

On the other hand, things were going ill with the little church of All Angels. Arthur kept his people as tensely strung as ever, but he no longer drew from them the chords of aspiration and enterprise. It was a sad disenchantment, and none the less so because no one seemed to know what the matter was. One darkly guessed he was writing a book, and the vestryman who had praised the lovely simplicity of the wedding lucidly explained that the young rector had "lost his grip."

At times there were flashes of recovery. One Sabbath the whole congregation came out under his benediction uplifted by his word that "loving is living."

"The more we love," they quoted him on their various ways home, "the more we live. The deeper we love, the deeper we live. The more selfishly or unselfishly, the higher, the broader, the purer, the wiser, we love, the more selfishly or unselfishly, the higher, the broader, the purer, the wiser, we live!" The rector's gentle wife was visibly and ever so prettily rejoiced.

True, but hardly the whole truth. In her mother's cottage her smiles were almost sad, and when she had crossed the garden and got into her own room she dropped upon her bed and wept. Yet she quickly ceased, and put on again a brave serenity, for a very tender reason which forbade such risks.

A bunch of the church's best men got together and agreed that all Arthur needed was rest; that this bright moment was the right one in which to offer him a vacation; that his physician should flatly order him to take it; and that Byington should arrange the matter.

Leonard accepted the task, the physician spoke with startling flatness, and the whole kind plot worked well. Arthur consented to go away up into the hills beyond all the jar of the busy world's unrest.

Isabel was to go with him, and they were to sojourn at some point where she would still be within prompt reach of medical skill, yet from which he could make long jaunts into the absolute wilds.

Mrs. Morris was far from well when they left, and the day afterward she was seriously ill. That night Ruth sat up with her, and the next day she was worse, yet begged that no telegram be sent to her daughter.

At the close of the day there came a letter from Isabel. It said that Arthur, "already a new man," would start the next morning at dawn for a three days' trip into the wilderness. He went; and he had not been three hours gone when Isabel received a dispatch calling her to her mother. The only day train would leave in a few minutes, and she had the fortune to catch it.

Ruth met her at the station with the blessed word "better." They went up from the town in Ruth's carriage, Martin Kelly driving, who let it be known that though the doctor's name, "moy graciouz!" were signed to the telegram seven times over, the actual painstaker and sender was "Linnard Boyington, whatsomiver!"

Still Ruth called it the doctor's telegram, and said it made no difference who sent it; but she saw Isabel was disturbed. "Well, Martin, Doctor will have to wait on himself to-morrow; Leonard will be out of town."

That evening, alone with her brother, she said, "But I thought you were to be out of town to-morrow."

"No," he replied, "I don't think I'd better."

Another day passed, another came, and Mrs. Morris was still in danger. Isabel wrote Arthur that she would be with him the moment the peril was over, if he needed her; but if he did not, she would stay on for her mother's fuller recovery. Her letter had barely gone when she received a pencilled line brought in to the mountain hotel by a chance messenger and sent on to her, saying he would be out on his tramp five days instead of three. On the fifth day she telegraphed that her mother was getting well so fast that she would come, now, at his word.

The next morning she betrayed to Ruth a glad sense of relief as she showed her a dispatch from Arthur, which read: "Going on another trip to-morrow. Stay till I write."

Ruth repeated it to her father and brother at their noonday meal. Leonard made no comment, but the General asked pleasantly—

"Is she certain he won't come in on this evening's express?" He was discerning more than any one wanted him to.

However, at dusk came the train, took water at the tank, stopped at the station, and passed on, and Arthur did not appear.

"Well, I'll go to bed," blithely spoke the General. "I'm not so old as I used to be, but I'm tired, after writing that letter this afternoon—to Godfrey. Good-night." So he gave fair notice that he had moved in this matter, himself.

"I didn't know father had received a letter from Godfrey," said Ruth, shading her face from the lamp, and lifting to Leonard a smile which implied that it would have been but fair for him to have told her.

"It came the day before Arthur went away," replied Leonard, and Ruth reluctantly chose a new topic.

They rarely had an evening together thus, and with a soft rain falling at the open windows they sat and talked on many themes in what was to them a very talkative way. When something brought up the subject of the late noted trial, Ruth asked her brother how it had first come to him to suspect so unsuspected a man.

His reply was tardy. "Partly," he said, and mused while he spoke, "because I am so unsuspected a man myself."

He looked up with a smile, half play, half pain. "I know what the mind of an unsuspected man is capable of—under pressure."

The questioner looked on him with fond faith, and then, dropping her eyes to her needlework, said, "That wasn't all that prompted you, was it?"

"No," replied the brother, again musing. "I had noticed the singular value of wanton guesswork."

"I thought so," said the sister. Her needle flagged and stopped, and each knew the other's mind was on the implacable divinations of one morbid soul.

Leonard leaned and fingered the needlework,—a worsted slipper, too small for most men, too large for most women. "Is that for him?"

"Yes," apologized Ruth; "it's the thing every clergyman has to incur. But I'm only doing it to help Isabel out; she has the other."

The evening went quickly. When Leonard let down the window sashes and lowered the shades, Ruth, standing by the lamp as if to put out its light, said, "I'll not go up for a moment or two yet."

She sent him an ardent smile across the room and turned to a desk.

Ruth wrote to her lover. Her father's keeping secret his receipt of Godfrey's letter until he had mailed its answer, could mean only that the answer was for Godfrey to come home. The General's talk of being tired by the writing of it was a purely expletive irony, for he had written with the brevity of an old soldier to a young sailor; but he had written that trouble was impending, that its source was Arthur, and that the last hope of removing it lay with him, Godfrey.

A line from Ruth, pursuing after this message, would be one steamer behind it all the way, but it would reach the far wanderer before any leave would permit him to start homeward.

So, now, what should she write? If her father had discerned so much more than he had let any one know he had discerned, how about others? How about the kind whose chief joy is ruthless guesswork? That need of haste was one she had overlooked. Wise father!

And yet—haste itself is such a hazardous thing! Ah, if Arthur had come in on that evening express, what to write were an easier question. The minutes sped by; her pen overhung the paper with the opening sentence unfinished, and every moment the thought she kept putting away came back: "Leonard!—Leonard!—Godfrey's summons should go to him from Leonard; and it should flash under the seas, not crawl across them!"—Hark!

She rose and glided to the door through which her brother had gone. There she was startled by the sight of him speeding cautiously down the stair.

On entering his unlighted room Leonard had moved across it to a front window, where, veiled by the chamber's dusk, he stood looking out into a night dimly illumined by the overclouded moon. The Winslow house widened palely among its surrounding trees. The servants' rooms were remote as well as on the farther side, and on the nearer side no lamplight shone. A short way down the street a glow came from the Morris cottage. Evidently Isabel was with her mother.

He stood and mused, unconsciously lulled by the cool drip of myriad leaves, and with his mind poised midway between emotion and thought. To yield to emotion would have been to chafe against the bands that knitted his life and hers to every life about them. To yield to thought would have been to think of her as no more to be drawn from these surrounding ties than some animate rainbow-fringed flower of the sea can be torn from its shell without laceration and death. To give thought word would have been to cry, "Oh, truest of womankind, where would this unsuspected man, this Leonard Byington, be if you were other than you are?" Yet the suspense between avoided feeling and avoided thought held him where he stood.

So standing, it drifted idly into his mind that yonder arbor must be very wet to-night, and the cinder sidewalk out here much drier. As the thought moved him to draw one step back, the glow from the cottage broadened. Its front door had opened, and Mrs. Morris's young maid came out with a lantern, followed by Isabel saying last fond words to her mother as the convalescent closed the door.

"Good-night!" she called back.

In one great wave the young man's passion rolled over its bounds and brought him to his knees with arms outstretched. "Oh, Isabel!" he murmured. "Oh, my God! Oh, Isabel! Isabel! if I had but lost you fairly!"

The two slight figures came daintily along the wet path in single file, the maid throwing the lantern's beams hither and yon as she looked back to answer Isabel's kindly questions; Isabel one moment half lost in the gloom of the trees, and then so lighted up again from foot to brow that it was easy to see the very lines of her winsome mouth, ripe for compassion or fortitude, yet wishful as a little child's.

Her secret observer moaned as he stood erect. The fury of his soul seemed to enhance his stature. He did not speak again, but, "Oh, Isabel! harder to strive against than all the world beside!" was the unuttered cry that wrote itself upon his tortured brow. "If your unfair winner would only hold you by fair means! Yet I too was to blame! I too was to blame, and you alone were blameless!"

Opposite his window Isabel ceased her light talk with the maid, halted, bent, and scanned something just off the firm path, in the clean wet sand.

The maid turned and flooded her with the light of the lantern just as she impulsively lifted an alarmed glance to Leonard's window and as quickly averted it. "Go on," said the mistress. "I can walk faster if you can."

The girl quickened her steps, but had not taken a dozen when Isabel stopped again. "Wait, Minnie. Now you can run back, thank you." She reached for the lantern.

"I—I thought I was to go all the way, and—and bring the lantern back."

"No, I'll keep the lantern; but I'll stay here and throw the light after you till you get in. Run along."

Minnie tripped away. As she came where they had first halted, a purposely belated good-night softly overtook her; and when she looked back, Isabel, as if by inadvertency, sent the lantern's beam into her eyes. So too much light sent the maid by the spot unenlightened.

Leonard drew aside lest the beam swing next into his window. But the precaution was wasted; the glare followed Minnie.

Isabel also followed, slowly, a few paces, and then moved obliquely into the roadway and toward the window. Only for a moment the ray swept near her unseen observer, and, lighting up the rain-packed sand close before herself, revealed a line of footprints slanting toward her from Leonard's own gate.

As the cottage door shut Minnie in, Isabel, reassured by the brightness of the Byingtons' lower windows, stopped for a furtive instant, and holding in her hand the fellow of the slipper so lately in Ruth's fingers, exactly fitted it to one of these footprints. Then, with the lantern on her farther side, and every vein surging with fright and shame, she made haste toward the open gateway of the Winslow house.

A short space from it she recoiled with a gesture of dismay and self-repression, and her light shone full upon a man. He stepped from the garden, his form tensely lifted, his face aflame with anger.

But her small figure straightened also, and swiftly muffling the lantern in a fold of her skirt, she exclaimed, audibly only to him, though in words clear-cut as musical notes, "Oh, Arthur Winslow, has it come to this?"

She arrested his resentful answer by the uplift of a hand, which left the lantern again uncovered. "Inside! In the house!" she softly cried, starting on. "Not here! Look!—those upper windows!—we're in full view of them!"

Quickly she remuffled the lantern, but not in time to hide his motion as he threw out an arm and pushed her rudely back, while he exclaimed, "In full view of them answer me one question!"