This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net

Title: In the Days of Poor Richard

Author: Irving Bacheller

Release Date: April 12, 2005 [eBook #15608]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK IN THE DAYS OF POOR RICHARD***

Discerning Student and Interpreter of the Spirit of the Prophets, the Struggle of the Heroes and the Wisdom of the Founders of Democracy, I Dedicate This Volume.

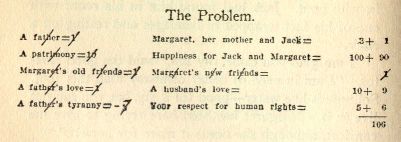

Much of the color of the love-tale of Jack and Margaret, which is a part of the greater love-story of man and liberty, is derived from old letters, diaries, and newspaper clippings in the possession of a well-known American family.

"The first time I saw the boy, Jack Irons, he was about nine years old. I was in Sir William Johnson's camp of magnificent Mohawk warriors at Albany. Jack was so active and successful in the games, between the red boys and the white, that the Indians called him 'Boiling Water.' His laugh and tireless spirit reminded me of a mountain brook. There was no lad, near his age, who could run so fast, or jump so far, or shoot so well with the bow or the rifle. I carried him on my back to his home, he urging me on as if I had been a battle horse and when we were come to the house, he ran about doing his chores. I helped him, and, our work accomplished, we went down to the river for a swim, and to my surprise, I found him a well taught fish. We became friends and always when I have thought of him, the words Happy Face have come to me. It was, I think, a better nickname than 'Boiling Water,' although there was much propriety in the latter. I knew that his energy given to labor would accomplish much and when I left him, I repeated the words which my father had often quoted in my hearing:

"'Seest thou a man diligent in his calling? He shall stand before kings.'"

This glimpse of John Irons, Jr.--familiarly known as Jack Irons--is from a letter of Benjamin Franklin to his wife.

Nothing further is recorded of his boyhood until, about eight years later, what was known as the "Horse Valley Adventure" occurred. A full account of it follows with due regard for background and color:

"It was the season o' the great moon," said old Solomon Binkus, scout and interpreter, as he leaned over the camp-fire and flicked a coal out of the ashes with his forefinger and twiddled it up to his pipe bowl. In the army he was known as "old Solomon Binkus," not by reason of his age, for he was only about thirty-eight, but as a mark of deference. Those who followed him in the bush had a faith in his wisdom that was childlike. "I had had my feet in a pair o' sieves walkin' the white sea a fortnight," he went on. "The dry water were six foot on the level, er mebbe more, an' some o' the waves up to the tree-tops, an' nobody with me but this 'ere ol' Marier Jane [his rifle] the hull trip to the Swegache country. Gol' ding my pictur'! It seemed as if the wind were a-tryin' fer to rub it off the slate. It were a pesky wind that kep' a-cuffin' me an' whistlin' in the briers on my face an' crackin' my coat-tails. I were lonesome--lonesomer'n a he-bear--an' the cold grabbin' holt o' all ends o' me so as I had to stop an' argue 'bout whar my bound'ry-lines was located like I were York State. Cat's blood an' gun-powder! I had to kick an' scratch to keep my nose an' toes from gittin'--brittle."

At this point, Solomon Binkus paused to give his words a chance "to sink in." The silence which followed was broken only by the crack of burning faggots and the sound of the night wind in the tall pines above the gorge. Before Mr. Binkus resumes his narrative, which, one might know by the tilt of his head and the look of his wide open, right eye, would soon happen, the historian seizes the opportunity of finishing his introduction. He had been the best scout in the army of Sir Jeffrey Amherst. As a small boy he had been captured by the Senecas and held in the tribe a year and two months. Early in the French and Indian War, he had been caught by Algonquins and tied to a tree and tortured by hatchet throwers until rescued by a French captain. After that his opinion of Indians had been, probably, a bit colored by prejudice. Still later he had been a harpooner in a whale boat, and in his young manhood, one of those who had escaped the infamous massacre at Fort William Henry when English forces, having been captured and disarmed, were turned loose and set upon by the savages. He was a tall, brawny, broad-shouldered, homely-faced man of thirty-eight with a Roman nose and a prominent chin underscored by a short sandy throat beard. Some of the adventures had put their mark upon his weathered face, shaven generally once a week above the chin. The top of his left ear was missing. There was a long scar upon his forehead. These were like the notches on the stock of his rifle. They were a sign of the stories of adventure to be found in that wary, watchful brain of his.

Johnson enjoyed his reports on account of their humor and color and he describes him in a letter to Putnam as a man who "when he is much interested, looks as if he were taking aim with his rifle." To some it seemed that one eye of Mr. Binkus was often drawing conclusions while the other was engaged with the no less important function of discovery.

His companion was young Jack Irons--a big lad of seventeen, who lived in a fertile valley some fifty miles northwest of Fort Stanwix, in Tryon County, New York. Now, in September, 1768, they were traveling ahead of a band of Indians bent on mischief. The latter, a few days before, had come down Lake Ontario and were out in the bush somewhere between the lake and the new settlement in Horse Valley. Solomon thought that they were probably Hurons, since they, being discontented with the treaty made by the French, had again taken the war-path. This invasion, however, was a wholly unexpected bit of audacity. They had two captives--the wife and daughter of Colonel Hare, who had been spending a few weeks with Major Duncan and his Fifty-Fifth Regiment, at Oswego. The colonel had taken these ladies of his family on a hunting trip in the bush. They had had two guides with them, one of whom was Solomon Binkus. The men had gone out in the early evening after moose and imprudently left the ladies in camp, where the latter had been captured. Having returned, the scout knew that the only possible explanation for the absence of the ladies was Indians, although no peril could have been more unexpected. He had discovered by "the sign" that it was a large band traveling eastward. He had set out by night to get ahead of them while Hare and his other guide started for the fort. Binkus knew every mile of the wilderness and had canoes hidden near its bigger waters. He had crossed the lake on which his party had been camping, and the swamp at the east end of it and was soon far ahead of the marauders. A little after daylight, he had picked up the boy, Jack Irons, at a hunting camp on Big Deer Creek, as it was then called, and the two had set out together to warn the people in Horse Valley, where Jack lived, and to get help for a battle with the savages.

It will be seen by his words that Mr. Binkus was a man of imagination, but--again he is talking.

"I were on my way to a big Injun Pow-wow at Swegache fer Sir Bill--ayes it were in Feb'uary, the time o' the great moon o' the hard snow. Now they be some good things 'bout Injuns but, like young brats, they take natural to deviltry. Ye may have my hide fer sole luther if ye ketch me in an Injun village with a load o' fire-water. Some Injuns is smart, an' gol ding their pictur's! they kin talk like a cat-bird. A skunk has a han'some coat an' acts as cute as a kitten but all the same, which thar ain't no doubt o' it, his friendship ain't wuth a dam. It's a kind o' p'ison. Injuns is like skunks, if ye trust 'em they'll sp'ile ye. They eat like beasts an' think like beasts, an' live like beasts, an' talk like angels. Paint an' bear's grease, an' squaw-fun, an' fur, an' wampum, an' meat, an' rum, is all they think on. I've et their vittles many a time an' I'm obleeged to tell ye it's hard work. Too much hair in the stew! They stick their paws in the pot an' grab out a chunk an' chaw it an' bolt it, like a dog, an' wipe their hands on their long hair. They brag 'bout the power o' their jaws, which I ain't denyin' is consid'able, havin' had an ol' buck bite off the top o' my left ear when I were tied fast to a tree which--you hear to me--is a good time to learn Injun language 'cause ye pay 'tention clost. They ain't got no heart er no mercy. How they kin grind up a captive, like wheat in the millstuns, an' laugh, an' whoop at the sight o' his blood! Er turn him into smoke an' ashes while they look on an' laugh--by mighty!--like he were singin' a funny song. They'd be men an' women only they ain't got the works in 'em. Suthin' missin'. By the hide an' horns o' the devil! I ain't got no kind o' patience with them mush hearts who say that Ameriky belongs to the noble red man an' that the whites have no right to bargain fer his land. Gol ding their pictur's! Ye might as well say that we hain't no right in the woods 'cause a lot o' bears an' painters got there fust, which I ain't a-sayin' but what bears an' painters has their rights."

Mr. Binkus paused again to put another coal on his pipe. Then he listened a moment and looked up at the rocks above their heads, for they were camped in a cave at the mouth of which they had built a small fire, in a deep gorge. Presently he went on:

"I found a heap o' Injuns at Swegache--Mohawks, Senekys, Onandogs an' Algonks. They had been swappin' presents an' speeches with the French. Just a little while afore they had had a bellerin' match with us 'bout love an' friendship. Then sudden-like they tuk it in their heads that the French had a sharper hatchet than the English. I were skeered, but when I see that they was nobody drunk, I pushed right into the big village an' asked fer the old Senecky chief Bear Face--knowin' he were thar--an' said I had a letter from the Big Father. They tuk me to him.

"I give him a chain o' wampum an' then read the letter from Sir Bill. It offered the Six Nations more land an' a fort, an' a regiment to defend 'em. Then he give me a lot o' hedge-hog quills sewed on to buckskin an' says he:

"'You are like a lone star in the night, my brother. We have stretched out our necks lookin' fer ye. We thought the Big Father had forgot us. Now we are happy. To-morrer our faces will turn south an' shine with bear's grease.'

"Sez I: 'You must wash no more in the same water with the French. You must return to The Long House. The Big Father will throw his great arm eround you.'

"I strutted up an' down, like a turkey gobbler, an' bellered out a lot o' that high-falutin' gab. I reckon I know how to shove an idee under their hides. Ye got to raise yer voice an' look solemn an' point at the stars. A powerful lot o' Injuns trailed back to Sir Bill, but they was a few went over to the French. I kind o' mistrust thar's some o' them runnygades behind us. They're 'spectin' to git a lot o' plunder an' a horse apiece an' ride 'em back an' swim the river at the place o' the many islands. We'll poke down to the trail on the edge o' the drownded lands afore sunrise an' I kind o' mistrust we'll see sign."

Jack Irons was a son of the much respected John Irons from New Hampshire who, in the fertile valley where he had settled some years before, was breeding horses for the army and sending them down to Sir William Johnson. Hence the site of his farm had been called Horse Valley.

Mr. Binkus went to the near brook and repeatedly filled his old felt hat with water and poured it on the fire. "Don't never keep no fire a-goin' a'ter I'm dried out," he whispered, as he stepped back into the dark cave, "'cause ye never kin tell."

The boy was asleep on the bed of boughs. Mr. Binkus covered him with the blanket and lay down beside him and drew his coat over both.

"He'll learn that it ain't no fun to be a scout," he whispered with a yawn and in a moment was snoring.

It was black dark when he roused his companion. Solomon had been up for ten minutes and had got their rations of bread and dried venison out of his pack and brought a canteen of fresh water.

"The night has been dark. A piece o' charcoal would 'a' made a white mark on it," said Solomon.

"How do you know it's morning?" the boy asked as he rose, yawning.

"Don't ye hear that leetle bird up in the tree-top?" Solomon answered in a whisper. "He says it's mornin' jest as plain as a clock in a steeple an' that it's goin' to be cl'ar. If you'll shove this 'ere meat an' bread into yer stummick, we'll begin fer to make tracks."

They ate in silence and as he ate Solomon was getting his pack ready and strapping it on his back and adjusting his powder-horn.

"Ye see it's growin' light," he remarked presently in a whisper. "Keep clost to me an' go as still as ye kin an' don't speak out loud never--not if ye want to be sure to keep yer ha'r on yer head."

They started down the foot of the gorge then dim in the night shadows. Binkus stopped, now and then, to listen for two or three seconds and went on with long stealthy strides. His movements were panther-like, and the boy imitated them. He was a tall, handsome, big-framed lad with blond hair and blue eyes. They could soon see their way clearly. At the edge of the valley the scout stopped and peered out upon it. A deep mist lay on the meadows.

"I like day-dark in Injun country," he whispered. "Come on."

They hurried through sloppy footing in the wet grass that flung its dew into their garments from the shoulder down. Suddenly Mr. Binkus stopped. They could hear the sound of heavy feet splashing in the wet meadow.

"Scairt moose, runnin' this way!" the scout whispered. "I'll bet ye a pint o' powder an' a fish hook them Injuns is over east o' here."

It was his favorite wager--that of a pint of powder and a fish hook.

They came out upon high ground and reached the valley trail just as the sun was rising. The fog had lifted. Mr. Binkus stopped well away from the trail and listened for some minutes. He approached it slowly on his tiptoes, the boy following in a like manner. For a moment the scout stood at the edge of the trail in silence. Then, leaning low, he examined it closely and quickly raised his hand.

"Hoofs o' the devil!" he whispered as he beckoned to the boy. "See thar," he went on, pointing to the ground. "They've jest gone by. The grass ain't riz yit. Wait here."

He followed the trail a few rods with eyes bent upon it. Near a little run where there was soft dirt, he stopped again and looked intently at the earth and then hurried back.

"It's a big band. At least forty Injuns in it an' some captives, an' the devil an' Tom Walker. It's a mess which they ain't no mistake."

"I don't see why they want to be bothered with women," the boy remarked.

"Hostiges!" Solomon exclaimed. "Makes 'em feel safer. Grab 'em when they kin. If overtook by a stouter force they're in shape fer a dicker. The chief stands up an' sings like a bird--'bout the moon an' the stars an' the brooks an' the rivers an' the wrongs o' the red man, but it wouldn't be wuth the song o' a barn swaller less he can show ye that the wimmen are all right. If they've been treated proper, it's the same as proved. Ye let 'em out o' the bear trap which it has often happened. But you hear to me, when they go off this way it's to kill an' grab an' hustle back with the booty. They won't stop at butcherin'!"

"I'm afraid my folks are in danger," said the boy as he changed color.

"Er mebbe Peter Boneses'--'cordin' to the way they go. We got to cut eround 'em an' plow straight through the bush an' over Cobble Hill an' swim the big creek an' we'll beat 'em easy."

It was a curious, long, loose stride, the knees never quite straightened, with which the scout made his way through the forest. It covered ground so swiftly that the boy had, now and then, to break into a dog-trot in order to keep along with the old woodsman. They kept their pace up the steep side of Cobble Hill and down its far slope and the valley beyond to the shore of the Big Creek.

"I'm hot 'nough to sizzle an' smoke when I tech water," said the scout as he waded in, holding his rifle and powder-horn in his left hand above the creek's surface.

They had a few strokes of swimming at mid-stream but managed to keep their powder dry.

"Now we've got jest 'nough hoppin' to keep us from gittin' foundered," said Solomon, as he stood on the farther shore and adjusted his pack. "It ain't more'n a mile to your house."

They hurried on, reaching the rough valley road in a few minutes.

"Now I'll take the bee trail to your place," said the scout. "You cut ercrost the medder to Peter Boneses' an' fetch 'em over with all their grit an' guns an' ammunition."

Solomon found John Irons and five of his sons and three of his daughters digging potatoes and pulling tops in a field near the house. The sky was clear and the sun shining warm. Solomon called Irons aside and told him of the approaching Indians.

"What are we to do?" Irons asked.

"Send the women an' the babies back to the sugar shanty," said Solomon. "We'll stay here 'cause if we run erway the Boneses'll git their ha'r lifted. I reckon we kin conquer 'em."

"How?"

"Shoot 'em full o' meat. They must 'a' traveled all night. Them Injuns is tired an' hungry. Been three days on the trail. No time to hunt! I'll hustle some wood together an' start a fire. You bring a pair o' steers right here handy. We'll rip their hides off an' git the reek o' vittles in the air soon as God'll let us."

"My wife can use a gun as well as I can and I'm afraid she won't go," said Irons.

"All right, let her hide somewhar nigh with the guns," said Solomon. "The oldest gal kin go back with the young 'uns. Don't want no skirts in sight when they git here."

Mrs. Irons hid in the shed with the loaded guns.

Ruth Irons and the children set out for the sugar bush. The steers were quickly led up and slaughtered. As a hide ripper, Solomon was a man of experience. The loins of one animal were cooking on turnspits and a big pot of beef, onions and potatoes boiling over the fire when Jack arrived with the Bones family.

"It smells good here," said Jack.

"Ayes! The air be gittin' the right scent on it," said Solomon, as he was ripping the hide off the other steer. "I reckon it'll start the sap in their mouths. You roll out the rum bar'l an' stave it in. Mis' Bones knows how to shoot. Put her in the shed with yer mother an' the guns, an' take her young 'uns to the sugar shanty 'cept Isr'el who's big 'nough to help."

A little later Solomon left the fire. Both his eye and his ear had caught "sign"--a clamor among the moose birds in the distant bush and a flock of pigeons flying from the west.

"Don't none o' ye stir till I come back," he said, as he turned into the trail. A few rods away he lay down with his ear to the ground and could distinctly hear the tramp of many feet approaching in the distance. He went on a little farther and presently concealed himself in the bushes close to the trail. He had not long to wait, for soon a red scout came on ahead of the party. He was a young Huron brave, his face painted black and yellow. His head was encircled by a snake skin. A fox's tail rose above his brow and dropped back on his crown. A birch-bark horn hung over his shoulder.

Solomon stepped out of the bushes after he had passed and said in the Huron tongue: "Welcome, my red brother, I hear that a large band o' yer folks is comin' and we have got a feast ready."

The young brave had been startled by the sudden appearance of Solomon, but the friendly words had reassured him.

"We are on a long journey," said the brave.

"And the flesh of a fat ox will help ye on yer way. Kin ye smell it?"

"Brother, it is like the smell of the great village in the Happy Hunting-Grounds," said the brave. "We have traveled three sleeps from the land of the long waters and have had only two porcupines and a small deer to eat. We are hungry."

"And we would smoke the calumet of peace with you," said Solomon.

They walked on together and in a moment came in sight of the little farm-house. The brave looked at the house and the three men who stood by the fire.

"Come with me and you shall see that we are few," Solomon remarked.

They entered the house and barn and walked around them, and this, in effect, is what Solomon said to him:

"I am the chief scout of the Great Father. My word is like that of old Flame Tongue--your mighty chief. You and your people are on a bad errand. No good can come of it. You are far from your own country. A large force is now on your trail. If you rob or kill any one you will be hung. We know your plans. A bad white chief has brought you here. He has a wooden leg with an iron ring around the bottom of it. He come down lake in a big boat with you. Night before last you stole two white women."

A look of fear and astonishment came upon the face of the Indian.

"You are a son of the Great Spirit!" he exclaimed.

"And I would keep yer feet out o' the snare. Let me be yer chief. You shall have a horse and fifty beaver skins and be taken to the border and set free. I, the scout of the Great Father, have said it, and if it be not as I say, may I never see the Happy Hunting-Grounds."

The brave answered:

"My white brother has spoken well and he shall be my chief. I like not this journey. I shall bid them to the feast. They will eat and sleep like the gray wolf for they are hungry and their feet are sore."

The brave put his horn to his mouth and uttered a wild cry that rang in the distant hills. Then arose a great whooping and kintecawing back in the bush. The young Huron went out to meet the band. Returning soon, he said to Solomon that his chief, the great Splitnose, would have words with him.

Turning to John Irons, Solomon said: "He's an outlaw chief. We must treat him like a king. I'll bring 'em in. You keep the meat a-sizzlin'!"

The scout went with the brave to his chief and made a speech of welcome, after which the wily old Splitnose, in his wonderful head-dress, of buckskin and eagle feathers, and his band in war-paint, followed Solomon to the feast. Silently they filed out of the bush and sat on the grass around the fire. There were no captives among them--none at least of the white skin.

Solomon did not betray his disappointment. Not a word was spoken. He and John Irons and his son began removing the spits from the fire and putting more meat upon them and cutting the cooked roasts into large pieces and passing it on a big earthen platter. The Indians eagerly seized the hot meat and began to devour it. While waiting to be served, some of the young braves danced at the fire's edge with short, explosive, yelping, barking cries answered by dozens of guttural protesting grunts from the older men, who sat eating or eagerly waiting their turn to grab meat. It was a trying moment. Would the whole band leap up and start a dance which might end in boiling blood and tiger fury and a massacre? But the young Huron brave stopped them, aided no doubt by the smell of the cooking flesh and the protest of the older men. There would be no war-dance--at least not yet--too much hunger in the band and the means of satisfying it were too close and tempting. Solomon had foreseen the peril and his cunning had prevented it.

In a letter he has thus described the incident: "It were a band o' cutthroat robbers an' runnygades from the Ohio country--Hurons, Algonks an' Mingos an' all kinds o' cast off red rubbish with an old Algonk chief o' the name o' Splitnose. They stuffed their hides with the meat till they was stiff as a foundered hoss. They grabbed an' chawed an' bolted it like so many hogs an' reached out fer more, which is the differ'nce betwixt an Injun an' a white man. The white man gen'ally knows 'nough to shove down the brakes on a side-hill. The Injun ain't got no brakes on his wheels. Injuns is a good deal like white brats. Let 'em find the sugar tub when their ma is to meetin' an' they won't worry 'bout the bellyache till it comes. Them Injuns filled themselves to the gullet an' begun to lay back, all swelled up, an' roll an' grunt an' go to sleep. By an' by they was only two that was up an' pawin' eround in the stew pot fer 'nother bone, lookin' kind o' unsart'tn an' jaw weary. In a minute they wiped their hands on their ha'r an' lay back fer rest. They was drunk with the meat, as drunk as a Chinee a'ter a pipe o' opium. We white men stretched out with the rest on 'em till we see they was all in the land o' nod. Then we riz an' set up a hussle. Hones' we could 'a' killed 'em with a hammer an' done it delib'rit. I started to pull the young Huron out o' the bunch. He jumped up very supple. He wasn't asleep. He had knowed better than to swaller a yard o' meat.

"Whar was the wimmen? I knowed that a part o' the band would be back in the bush with them 'ere wimmen. I'd seed suthin' in the trail over by the drownded lands that looked kind o' neevarious. It were like the end o' a wooden leg with an iron ring at the bottom an' consid'able weight on it. An Injun wouldn't have a wooden leg, least ways not one with an iron ring at the butt. My ol' thinker had been chawin' that cud all day an' o' a sudden it come to me that a white man were runnin' the hull crew. That's how I had gained ground with the red scout I took him out in the aidge o' the bush an' sez I:

"'What's yer name?'

"'Buckeye,' sez he.

"'Who's the white man that's with ye?'

"'Mike Harpe.'

"'Are the white wimmin with him?'

"'Yes.'

"'How many Injuns?'

"Two.'

"'What's yer signal o' victory?'

"'The call o' the moose.'

"'Now, Buckeye, you come with us,' I sez.

"I knowed that the white man were runnin' the hull party an' I itched to git holt o' him. Gol ding his pictur'! He'd sent the Injuns on ahead fer to do his dirty work. The Ohio country were full o' robber whelps which I kind o' mistrusted he were one on 'em who had raked up this 'ere band o' runnygades an' gone off fer plunder. We got holt o' most o' their guns very quiet, an' I put John Irons an' two o' his boys an' Peter Bones an' his boy Isr'el an' the two women with loaded guns on guard over 'em. If any on 'em woke up they was to ride the nightmare er lay still. Jack an' me an' Buckeye sneaked back up the trail fer 'bout twenty rod with our guns, an' then I told the young Injun to shoot off the moose call. Wall, sir, ye could 'a' heerd it from Albany to Wing's Falls. The answer come an' jest as I 'spected, 'twere within a quarter o' a mile. I put Jack erbout fifty feet further up the trail than I were, an' Buckeye nigh him, an' tol 'em what to do. We skootched down in the bushes an' heerd 'em comin'! Purty soon they hove in sight--two Injuns, the two wimmin captives an' a white man--the wust-lookin' bulldog brute that I ever seen--stumpin' erlong lively on a wooden leg, with a gun an' a cane. He had a broad head an' a big lop mouth an' thick lips an' a long, red, warty nose an' small black eyes an' a growth o' beard that looked like hog's bristles. He were stout built. Stood 'bout five foot seven. Never see sech a sight in my life. I hopped out afore 'em an' Jack an' Buckeye on their heels. The Injun had my ol' hanger.

"'Drop yer guns,' says I.

"The white man done as he were told. I spoke English an' mebbe them two Injuns didn't understan' me. We'll never know. Ol' Red Snout leaned over to pick up his gun, seein' as we'd fired ours. There was a price on his head an' he'd made up his mind to fight. Jack grabbed him. He were stout as a lion an' tore 'way from the boy an' started to pullin' a long knife out o' his boot leg. Jack didn't give him time. They had it hammer an' tongs. Red Snout were a reg'lar fightin' man. He jest stuck that 'ere stump in the ground an' braced ag'in' it an' kep' a-slashin' an' jabbin' with his club cane an' yellin' an' cussin' like a fiend o' hell. He knocked the boy down an' I reckon he'd 'a' mellered his head proper if he'd 'a' been spryer on his pins. But Jack sprung up like he were made o' Injy rubber. The bulldog devil had drawed his long knife. Jack were smart. He hopped behind a tree. Buckeye, who hadn't no gun, was jumpin' fer cover. The peg-leg cuss swore a blue streak an' flung the knife at him. It went cl'ar through his body an' he fell on his face an' me standin' thar loadin' my gun. I didn't know but he'd lick us all. But Jack had jumped on him 'fore he got holt o' the knife ag'in.

"I thought sure he'd floor the boy an' me not quite loaded, but Jack were as spry as a rat terrier. He dodged an' rushed in an' grabbed holt o' the club an' fetched the cuss a whack in the paunch with his bare fist, an' ol' Red Snout went down like a steer under the ax.

"'Look out! there's 'nother man comin',' the young womern hollered.

"She needn't 'a' tuk the trouble 'cause afore she spoke I were lookin' at him through the sight o' my ol' Marier which I'd managed to git it loaded ag'in. He were runnin' towards me. He tuk jest one more step, if I don't make no mistake.

"The ol' brute that Jack had knocked down quivered an' lay still a minit an' when he come to, we turned him, eround an' started him towards Canady an' tol' him to keep a-goin'! When he were 'bout ten rods off, I put a bullet in his ol' wooden leg fer to hurry him erlong. So the wust man-killer that ever trod dirt got erway from us with only a sore belly, we never knowin' who he were. I wish I'd 'a' killed the cuss, but as 'twere, we had consid'able trouble on our hands. Right erway we heard two guns go off over by the house. I knowed that our firin' had prob'ly woke up some o' the sleepers. We pounded the ground an' got thar as quick as we could. The two wimmen wa'n't fur behind. They didn't cocalate to lose us--you hear to me. Two young braves had sprung up an' been told to lie down ag'in. But the English language ain't no help to an Injun under them surcumstances. They don't understan' it an' thar ain't no time when ignerunce is more costly. They was some others awake, but they had learnt suthin'. They was keepin' quiet, an' I sez to 'em:

"'If ye lay still ye'll all be safe. We won't do ye a bit o' harm. You've got in bad comp'ny, but ye ain't done nothin' but steal a pair o' wimmen. If ye behave proper from now on, ye'll be sent hum.'

"We didn't have no more trouble with them. I put one o' Boneses' boys on a hoss an' hustled him up the valley fer help. The wimmen captives was bawlin'. I tol' 'em to straighten out their faces an' go with Jack an' his father down to Fort Stanwix. They were kind o' leg weary an' excited, but they hadn't been hurt yit. Another day er two would 'a' fixed 'em. Jack an' his father an' mother tuk 'em back to the pasture an' Jack run up to the barn fer ropes an' bridles. In a little while they got some hoofs under 'em an' picked up the childern an' toddled off. I went out in the bush to find Buckeye an' he were dead as the whale that swallered Jonah."

So ends the letter of Solomon Binkus.

Jack Irons and his family and that of Peter Bones--the boys and girls riding two on a horse--with the captives filed down the Mohawk trail. It was a considerable cavalcade of twenty-one people and twenty-four horses and colts, the latter following.

Solomon Binkus and Peter Bones and his son Israel stood on guard until the boy John Bones returned with help from the upper valley. A dozen men and boys completed the disarming of the band and that evening set out with them on the south trail.

It is doubtful if this history would have been written but for an accidental and highly interesting circumstance. In the first party young Jack Irons rode a colt, just broken, with the girl captive, now happily released. The boy had helped every one to get away; then there seemed to be no ridable horse for him. He walked for a distance by the stranger's mount as the latter was wild. The girl was silent for a time after the colt had settled down, now and then wiping tears from her eyes. By and by she asked:

"May I lead the colt while you ride?"

"Oh, no, I am not tired," was his answer.

"I want to do something for you."

"Why?"

"I am so grateful. I feel like the King's cat. I am trying to express my feelings. I think I know, now, why the Indian women do the drudgery."

As she looked at Him her dark eyes were very serious.

"I have done little," said he. "It is Mr. Binkus who rescued you. We live in a wild country among savages and the white folks have to protect each other. We're used to it."

"I never saw or expected to see men like you," she went on. "I have read of them in books, but I never hoped to see them and talk to them. You are like Ajax and Achilles."

"Then I shall say that you are like the fair lady for whom they fought."

"I will not ride and see you walking."

"Then sit forward as far as you can and I will ride with you," he answered.

In a moment he was on the colt's back behind her. She was a comely maiden. An authority no less respectable than Major Duncan has written that she was a tall, well shaped, fun loving girl a little past sixteen and good to look upon, "with dark eyes and auburn hair, the latter long and heavy and in the sunlight richly colored"; that she had slender fingers and a beautiful skin, all showing that she had been delicately bred. He adds that he envied the boy who had ridden before and behind her half the length of Tryon County.

It was a close association and Jack found it so agreeable that he often referred to that ride as the most exciting adventure of his life.

"What is your name?" he asked.

"Margaret Hare," she answered.

"How did they catch you?"

"Oh, they came suddenly and stealthily, as they do in the story books, when we were alone in camp. My father and the guides had gone out to hunt."

"Did they treat you well?"

"The Indians let us alone, but the two white men annoyed and frightened us. The old chief kept us near him."

"The old chief knew better than to let any harm come to you until they were sure of getting away with their plunder."

"We were in the valley of death and you have led us out of it. I am sure that I do not look as if I were worth saving. I suppose that I must have turned into an old woman. Is my hair white?"

"No. You are the best-looking girl I ever saw," he declared with rustic frankness.

"I never had a compliment that pleased me so much," she answered, as her elbows tightened a little on his hands which were clinging to her coat. "I almost loved you for what you did to the old villain. I saw blood on the side of your head. I fear he hurt you?"

"He jabbed me once. It is nothing."

"How brave you were!"

"I think I am more scared now than I was then," said Jack.

"Scared! Why?"

"I am not used to girls except my sisters."

She laughed and answered:

"And I am not used to heroes. I am sure you can not be so scared as I am, but I rather enjoy it. I like to be scared--a little. This is so different."

"I like you," he declared with a laugh.

"I feared you would not like an English girl. So many North Americans hate England."

"The English have been hard on us."

"What do you mean?"

"They send us governors whom we do not like; they make laws for us which we have to obey; they impose hard taxes which are not just and they will not let us have a word to say about it."

"I think it is wrong and I'm going to stand up for you," the girl answered.

"Where do you live?" he asked.

"In London. I am an English girl, but please do not hate me for that. I want to do what is right and I shall never let any one say a word against Americans without taking their part."

"That's good," the boy answered. "I'd love to go to London."

"Well, why don't you?"

"It's a long way off."

"Do you like good-looking girls?"

"I'd rather look at them than eat."

"Well, there are many in London."

"One is enough," said Jack.

"I'd love to show them a real hero."

"Don't call me that. If you would just call me Jack Irons I'd like it better. But first you'll want to know how I behave. I am not a fighter."

"I am sure that your character is as good as your face."

"Gosh! I hope it ain't quite so dark colored," said Jack.

"I knew all about you when you took my hand and helped me on the pony--or nearly all. You are a gentleman."

"I hope so."

"Are you a Presbyterian?"

"No--Church of England."

"I was sure of that. I have seen Indians and Shakers, but I have never seen a Presbyterian."

When the sun was low and the company ahead were stopping to make a camp for the night, the boy and girl dismounted. She turned facing him and asked:

"You didn't mean it when you said that I was good-looking--did you?"

The bashful youth had imagination and, like many lads of his time, a romantic temperament and the love of poetry. There were many books in his father's home and the boy had lived his leisure in them. He thought a moment and answered:

"Yes, I think you are as beautiful as a young doe playing in the water-lilies."

"And you look as if you believed yourself," said she. "I am sure you would like me better if I were fixed up a little."

"I do not think so."

"How much better a boy's head looks with his hair cut close like yours. Our boys have long hair. They do not look so much like--men."

"Long hair is not for rough work in the bush," the boy remarked.

"You really look brave and strong. One would know that you could do things."

"I've always had to do things."

They came up to the party who had stopped to camp for the night. It was a clear warm evening. After they had hobbled the horses in a near meadow flat, Jack and his father made a lean-to for the women and children and roofed it with bark. Then they cut wood and built a fire and gathered boughs for bedding. Later, tea was made and beefsteaks and bacon grilled on spits of green birch, the dripping fat being caught on slices of toasting bread whereon the meat was presently served.

The masterful power with which the stalwart youth and his father swung the ax and their cunning craftsmanship impressed the English woman and her daughter and were soon to be the topic of many a London tea party. Mrs. Hare spoke of it as she was eating her supper.

"It may surprise you further to learn that the boy is fairly familiar with the Aeneid and the Odes of Horace and the history of France and England," said John Irons.

"That is the most astonishing thing I have ever heard!" she exclaimed. "How has he done it?"

"The minister was his master until we went into the bush. Then I had to be farmer and school-teacher. There is a great thirst for learning in this New World."

"How do you find time for it?"

"Oh, we have leisure here--more than you have. In England even your wealthy young men are over-worked. They dine out and play cards until three in the morning and sleep until midday. Then luncheon and the cock fight and tea and Parliament! The best of us have only three steady habits. We work and study and sleep."

"And fight savages," said the woman.

"We do that, sometimes, but it is not often necessary. If it were not for white savages, there would be no red ones. You would find America a good country to live in."

"At least I hope it will be good to sleep in this night," the woman answered, yawning. "Dreamland is now the only country I care for."

The ladies and children, being near spent by the day's travel and excitement, turned in soon after supper. The men slept on their blankets, by the fire, and were up before daylight for a dip in the creek near by. While they were getting breakfast, the women and children had their turn at the creekside.

That day the released captives were in better spirits. Soon after noon the company came to a swollen river where the horses had some swimming to do. The older animals and the following colts went through all right, but the young stallion which Jack and Margaret were riding, began to rear and plunge. The girl in her fright jumped off his back in swift water and was swept into the rapids and tumbled about and put in some danger before Jack could dismount and bring her ashore.

"You have increased my debt to you," she said, when at last they were mounted again. "What a story this is! It is terribly exciting."

"Getting into deeper water," said Jack. "I'm not going to let you spoil it by drowning."

"I wonder what is coming next," said she.

"I don't know. So far it's as good as Robinson Crusoe."

"With a book you can skip and see what happens," she laughed. "But we shall have to read everything in this story. I'd love to know all about you."

He told her with boyish frankness of his plans which included learning and statesmanship and a city home. He told also of his adventures in the forest with his father.

Meanwhile, the elder John Irons and Mrs. Hare were getting acquainted as they rode along. The woman had been surprised by the man's intimate knowledge of English history and had spoken of it.

"Well, you see my wife is a granddaughter of Horatio Walpole of Wolterton and my mother was in a like way related to Thomas Pitt so you see I have a right to my interest in the history of the home land," said John Irons.

"You have in your veins some of the best blood of England and so I am sure that you must be a loyal subject of the King," Mrs. Hare remarked.

"No, because I think this German King has no share in the spirit of his country," Irons answered. "Our ancient respect for human rights and fair play is not in this man."

He presented his reasons for the opinion and while the woman made no answer, she had heard for the first time the argument of the New World and was impressed by it.

Late in the day they came out on a rough road, faring down into the settled country and that night they stopped at a small inn. At the supper table a wizened old woman was telling fortunes in a tea cup.

Miss Hare and her mother drained their cups and passed them to the old woman. The latter looked into the cup of the young lady and immediately her tongue began to rattle.

"Two ways lie before you," she piped in a shrill voice. "One leads to happiness and many children and wealth and a long life. It is steep and rough at the beginning and then it is smooth and peaceful. Yes. It crosses the sea. The other way is smooth at the start and then it grows steep and rough and in it I see tears and blood and dark clouds and, do you see that?" she demanded with a look of excitement, as she pointed into the cup. "It is a very evil thing. I will tell you no more."

The wizened old woman rose and, with a determined look in her face, left the room.

Mrs. Hare and her daughter seemed to be much troubled by the vision of the fortune-teller.

"I hope you do not believe in that kind of rubbish," John Irons remarked.

"I believe implicitly in the gift of second sight," said Mrs. Hare. "In England women are so impatient to know their fortunes that they will not wait upon Time, and the seers are prosperous."

"I have no faith in it," said Mr. Irons. "What she said might apply to the future of any young person. Undoubtedly there are two ways ahead of your daughter and perhaps more. Each must choose his own way wisely or come to trouble. It is the ancient law."

They rode on next morning in a rough road between clearings in the forest, the boy and girl being again together on the colt's back, she in front.

"You did not have your fortune told," said Miss Margaret.

"It has been told," Jack answered. "I am to be married in England to a beautiful young lady. I thought that sounded well and that I had better hold on to it. I might go further and fare worse."

"Tell me the kind of girl you would fancy."

"I wouldn't dare tell you."

"Why?"

"For fear it would spoil my luck."

They rode on with light hearts under a clear sky, their spirits playing together like birds in the sunlight, touching wings and then flying apart, until it all came to a climax quite unforeseen. The story has been passed from sire to son and from mother to daughter in a certain family of central New York and there are those now living who could tell it. These two were young and beautiful and well content with each other, it is said. So it would seem that Fate could not let them alone.

"We are near our journey's end," said he, by and by.

"Oh, then, let us go very slowly," she urged.

Another step and they had passed the hidden gate between reality and enchantment. It would appear that she had spoken the magic words which had opened it. They rode, for a time, without further speech, in a land not of this world, although, in some degree, familiar to the best of its people. Only they may cross that border who have kept much of the innocence of childhood and felt the delightful fear of youth that was in those two--they only may know the great enchantment. Does it not make an undying memory and bring to the face of age, long afterward, the smile of joy and gratitude?

The next word? What should it be? Both wondered and held their tongues for fear--one can not help thinking--and really they had little need of words. The peal of a hermit thrush filled the silence with its golden, largo chime and overtones and died away and rang out again and again. That voice spoke for them far better than either could have spoken, and they were content.

"There was no voice on land or sea so fit for the hour and the ears that heard it," she wrote, long afterward, in a letter.

They must have felt it in the longing of their own hearts and, perhaps, even a touch of the pathos in the years to come. They rode on in silence, feeling now the beauty of the green woods. It had become a magic garden full of new and wonderful things. Some power had entered them and opened their eyes. The thrush's song grew fainter in the distance. The boy was first to speak.

"I think that bird must have had a long flight sometime," he said.

"Why?"

"I am sure that he has heard the music of Paradise. I wonder if you are as happy as I am."

"I was never so happy," she answered.

"What a beautiful country we are in! I have forgotten all about the danger and the hardship and the evil men. Have you ever seen any place like it?"

"No. For a time we have been riding in fairyland."

"I know why," said the boy.

"Why?"

"It is because we are riding together. It is because I see you."

"Oh, dear! I can not see you. Let us get off and walk," she proposed.

They dismounted.

"Did you mean that honestly?"

"Honestly," he answered.

She looked up at him and put her hand over her mouth.

"I was going to say something. It would have been most unmaidenly," she remarked.

"There's something in me that will not stay unsaid. I love you," he declared.

She held up her hand with a serious look in her eyes. Then, for a moment, the boy returned to the world of reality.

"I am sorry. Forgive me. I ought not to have said it," he stammered.

"But didn't you really mean it?" she asked with troubled eyes.

"I mean that and more, but I ought not to have said it now. It isn't fair. You have just escaped from a great danger and have got a notion that you are in debt to me and you don't know much about me anyhow."

She stood in his path looking up at him.

"Jack," she whispered. "Please say it again."

No, it was not gone. They were still in the magic garden.

"I love you and I wish this journey could go on forever," he said.

She stepped closer and he put his arm around her and kissed her lips. She ran away a few steps. Then, indeed, they were back on the familiar trail in the thirty-mile bush. A moose bird was screaming at them. She turned and said:

"I wanted you to know but I have said nothing. I couldn't. I am under a sacred promise. You are a gentleman and you will not kiss me or speak of love again until you have talked with my father. It is the custom of our country. But I want you to know that I am very happy."

"I don't know how I dared to say and do what I did, but I couldn't help it"

"I couldn't help it either. I just longed to know if you dared."

"The rest will be in the future--perhaps far in the future."

His voice trembled a little.

"Not far if you come to me, but I can wait--I will wait." She took his hand as they were walking beside each other and added: "For you."

"I, too, will wait," he answered, "and as long as I have to."

Mrs. Hare, walking down the trail to meet them, had come near. Their journey out of the wilderness had ended, but for each a new life had begun.

The husband and father of the two ladies had reached the fort only an hour or so ahead of the mounted party and preparations were being made for an expedition to cut off the retreat of the Indians. He was known to most of his friends in America only as Colonel Benjamin Hare--a royal commissioner who had come to the colonies to inspect and report upon the defenses of His Majesty. He wore the uniform of a Colonel of the King's Guard. There is an old letter of John Irons which says that he was a splendid figure of a man, tall and well proportioned and about forty, with dark eyes, his hair and mustache just beginning to show gray.

"I shall not try here to measure my gratitude," he said to Mr. Irons. "I will see you to-morrow."

"You owe me nothing," Irons answered. "The rescue of your wife and daughter is due to the resourceful and famous scout--Solomon Binkus."

"Dear old rough-barked hickory man!" the Colonel exclaimed. "I hope to see him soon."

He went at once with his wife and daughter to rooms in the fort. That evening he satisfied himself as to the character and standing of John Irons, learning that he was a patriot of large influence and considerable means.

The latter family and that of Peter Bones were well quartered in tents with a part of the Fifty-Fifth Regiment then at Fort Stanwix. Next morning Jack went to breakfast with Colonel Hare and his wife and daughter in their rooms, after which the Colonel invited the boy to take a walk with him out to the little settlement of Mill River. Jack, being overawed, was rather slow in declaring himself and the Colonel presently remarked:

"You and my daughter seem to have got well acquainted."

"Yes, sir; but not as well as I could wish," Jack answered. "Our journey ended too soon. I love your daughter, sir, and I hope you will let me tell her and ask her to be my wife sometime."

"You are both too young," said the Colonel. "Besides you have known each other not quite three days and I have known you not as many hours. We are deeply grateful to you, but it is better for you and for her that this matter should not be hurried. After a year has passed, if you think you still care to see each other, I will ask you to come to England. I think you are a fine, manly, brave chap, but really you will admit that I have a right to know you better before my daughter engages to marry you."

Jack freely admitted that the request was well founded, albeit he declared, frankly, that he would like to be got acquainted with as soon as possible.

"We must take the first ship back to England," said the Colonel. "You are both young and in a matter of this kind there should be no haste. If your affection is real, it will be none the worse for a little keeping."

Solomon Binkus and Peter and Israel and John Bones and some settlers north of Horse Valley arrived next day with the captured Indians, who, under a military guard, were sent on to the Great Father at Johnson Castle.

Colonel Hare was astonished that neither Solomon Binkus nor John Irons nor his son would accept any gift for the great service they had done him.

"I owe you more than I can ever pay," he said to the faithful Binkus. "Money would not be good enough for your reward."

Solomon stepped close to the great man and said in a low tone:

"Them young 'uns has growed kind o' love sick an' I wouldn't wonder. I don't ask only one thing. Don't make no mistake 'bout this 'ere boy. In the bush we have a way o' pickin' out men. We see how they stan' up to danger an' hard work an' goin' hungry. Jack is a reg'lar he-man. I know 'em when I see 'em, which--it's a sure fact--I've seen all kinds. He's got brains an' courage, an' a tough arm an' a good heart. He'd die fer a friend any day. Ye kin't do no more. So don't make no mistake 'bout him. He ain't no hemlock bow. I cocalate there ain't no better man-timber nowhere--no, sir, not nowhere in this world--call it king er lord er duke er any name ye like. So, sir, if ye feel like doin' suthin' fer me--which I didn't never expect it, when I done what I did--I'll say be good to the boy. You'd never have to be 'shamed o' him."

"He's a likely lad," said Colonel Hare. "And I am rather impressed by your words, although they present a view that is new to me. We shall be returning soon and I dare say they will presently forget each other, but if not, and he becomes a good man--as good a man as his father--let us say--and she should wish to marry him, I would gladly put her hand in his."

A letter of the handsome British officer to his friend, Doctor Benjamin Franklin, reviews the history of this adventure and speaks of the learning, intelligence and agreeable personality of John Irons. Both Colonel and Mrs. Hare liked the boy and his parents and invited them to come to England, although the latter took the invitation as a mere mark of courtesy.

At Fort Stanwix, John Irons sold his farm and house and stock to Peter Bones and decided to move his family to Albany where he could educate his children. Both he and his wife had grown weary of the loneliness of the back country, and the peril from which they had been delivered was a deciding factor. So it happened that the Irons family and Solomon went to Albany by bateaux with the Hares. It was a delightful trip in good autumn weather in which Colonel Hare has acknowledged that both he and his wife acquired a deep respect "for these sinewy, wise, upright Americans, some of whom are as well learned, I should say, as most men you would meet in London."

They stopped at Schenectady, landing in a brawl between Whigs and Tories which soon developed into a small riot over the erection of a liberty pole. Loud and bitter words were being hurled between the two factions. The liberty lovers, being in much larger force, had erected the pole without violent opposition.

"Just what does this mean?" the Colonel asked John Irons.

"It means that the whole country is in a ferment of dissatisfaction," said Irons. "We object to being taxed by a Parliament in which we are not represented. The trouble should be stopped not by force but by action that will satisfy our sense of injustice--not a very difficult thing. A military force, quartered in Boston, has done great mischief."

"What liberty do you want?"

"Liberty to have a voice in the selection of our governors and magistrates and in the making of the laws we are expected to obey."

"I think it is a just demand," said the Colonel.

Solomon Binkus had listened with keen interest.

"I sucked in the love o' liberty with my mother's milk," he said. "Ye mustn't try to make me do nothin' that goes ag'in' my common sense; if ye do, ye're goin' to have a gosh hell o' a time with the ol' man which, you hear to me, will last as long as I do. These days there ortn't to be no sech thing 'mong white men as bein' born into captivity an' forced to obey a master, no argeyment bein' allowed. If your wife an' gal had been took erway by the Injuns, that's what would 'a' happened to 'em, which I'm sart'in they wouldn't 'a' liked it, ner you nuther, which I mean to say it respectful, sir."

The Colonel wore a look of conviction.

"I see how you feel about it," he said.

"It's the way all America feels about it," said Irons. "There are not five thousand men in the colonies who would differ with that view."

Having arrived in the river city, John Irons went, with his family, to The King's Arms. That very day the Hares took ship for New York on their way to England. Jack and Solomon went to the landing with them.

"Where is my boy?" Mrs. Irons asked when Binkus returned alone.

"Gone down the river," said the latter.

"Gone down the river!" Mrs. Irons exclaimed. "Why! Isn't that he coming yonder?"

"It's only part o' him," said Solomon. "His heart has gone down the river. But it'll be comin' back. It 'minds me o' the fust time I throwed a harpoon into a sperm whale. He went off like a bullet an' sounded an' took my harpoon an' a lot o' good rope with him an' got away with it. Fer days I couldn't think o' nothin' but that 'ere whale. Then he b'gun to grow smaller an' less important. Jack has lost his fust whale."

"He looks heart-broken--poor boy!"

"But ye orto have seen her. She's got the ol' harpoon in her side an' she were spoutin' tears an' shakin' her flukes as she moved away."

Solomon Binkus in his talk with Colonel Hare had signalized the arrival of a new type of man born of new conditions. When Lord Howe and General Abercrombie got to Albany with regiments of fine, high-bred, young fellows from London, Manchester and Liverpool, out for a holiday and magnificent in their uniforms of scarlet and gold, each with his beautiful and abundant hair done up in a queue, Mr. Binkus laughed and said they looked "terrible pert." He told the virile and profane Captain Lee of Howe's staff, that the first thing to do was to "make a haystack o' their hair an' give 'em men's clothes."

"A cart-load o' hair was mowed off," to quote again from Solomon, and all their splendor shorn away for a reason apparent to them before they had gone far on their ill-fated expedition. Hair-dressing and fine millinery and drawing-room clothes were not for the bush.

An inherited sense of old wrongs was the mental background of this new type of man. Life in the bush had strengthened his arm, his will and his courage. His words fell as forcefully as his ax under provocation. He was deliberate as became one whose scalp was often in danger; trained to think of the common welfare of his neighborhood and rather careless about the look of his coat and trousers.

John Irons and Solomon Binkus were differing examples of the new man. Of large stature, Irons had a reputation of being the strongest man in the New Hampshire grants. No name was better known or respected in all the western valleys. His father, a man of some means, had left him a reasonable competence.

Certain old records of Cumberland County speak of his unusual gifts, the best of which was, perhaps, modesty. He had once entertained Sir William Johnson at his house and had moved west, when the French and Indian War began, on the invitation of the governor, bringing his horses with him. For years he had been breeding and training saddle horses for the markets in New England. On moving he had turned his stock into Sir William's pasture and built a log house at the fort and served as an aid and counselor of the great man. Meanwhile his wife and children had lived in Albany. When the back country was thought safe to live in, at the urgent solicitation of Sir Jeffrey Amherst, he had gone to the northern valley with his herd, and prospered there.

Albany had one wide street which ran along the river-front. It ended at the gate of a big, common pasture some four hundred yards south of the landing which was near the center of the little city. In the north it ran into "the great road" beyond the ample grounds of Colonel Schuyler. The fort and hospital stood on the top of the big hill. Close to the shore was a fringe of elms, some of them tall and stately, their columns feathered with wild grape-vines. A wide space between the trees and the street had been turned into well-kept gardens, and their verdure was a pleasant thing to see. The town lay along the foot of a steep hill, and, midway, a huddle of buildings climbed a few rods up the slope. At the top was the English Church and below it were the Town Hall, the market and the Dutch Meeting-House. Other thoroughfares west of the main one were being laid out and settled.

John Irons was well known to Colonel Schuyler. The good man gave the newcomers a hearty welcome and was able to sell them a house ready furnished--the same having been lately vacated by an officer summoned to England. So it happened that John Irons and his family were quickly and comfortably settled in their new home and the children at work in school. He soon bought some land, partly cleared, a mile or so down the river and began to improve it.

"You've had lonesome days enough, mother," he said to his wife. "We'll live here in the village. I'll buy some good, young niggers if I can, and build a house for 'em, and go back and forth in the saddle."

The best families had negro slaves which were, in the main, like Abraham's servants, each having been born in the house of his master. They were regarded with affection.

It was a peaceful, happy, mutually helpful, God-fearing community in which the affairs of each were the concern of all. Every summer day, emigrants were passing and stopping, on their way west, towing bateaux for use in the upper waters of the Mohawk. These were mostly Irish and German people seeking cheap land, and seeing not the danger in wars to come.

There is an old letter from John Irons to his sister in Braintree which says that Jack, of whom he had a great pride, was getting on famously in school. "But he shows no favor to any of the girls, having lost his heart to a young English maid whom he helped to rescue from the Indians. We think it lucky that she should be far away so that he may better keep his resolution to be educated and his composure in the task."

The arrival of the mail was an event in Albany those days. Letters had come to be regarded there as common property. They were passed from hand to hand and read in neighborhood assemblies. Often they told of great hardship and stirring adventures in the wilderness and of events beyond the sea.

Every week the mail brought papers from the three big cities, which were read eagerly and loaned or exchanged until their contents had traveled through every street. Benjamin Franklin's Pennsylvania Gazette came to John Irons, and having been read aloud by the fireside was given to Simon Grover in exchange for Rivington's New York Weekly.

Jack was in a coasting party on Gallows Hill when his father brought him a fat letter from England. He went home at once to read it. The letter was from Margaret Hare--a love-letter which proposed a rather difficult problem. It is now a bit of paper so brittle with age it has to be delicately handled. Its neatly drawn chirography is faded to a light yellow, but how alive it is with youthful ardor:

"I think of you and pray for you very often," it says. "I hope you have not forgotten me or must I look for another to help me enjoy that happy fortune of which you have heard? Please tell me truly. My father has met Doctor Franklin who told of the night he spent at your home and that he thought you were a noble and promising lad. What a pleasure it was to hear him say that! We are much alarmed by events in America. My mother and I stand up for Americans, but my father has changed his views since we came down the Mohawk together. You must remember that he is a friend of the King. I hope that you and your father will be patient and take no part in the riots and house burnings. You have English blood in your veins and old England ought to be dear to you. She really loves America very much, indeed, if not as much as I love you. Can you not endure the wrongs for her sake and mine in the hope that they will soon be righted? Whatever happens I shall not cease to love you, but the fear comes to me that, if you turn against England, I shall love in vain. There are days when the future looks dark and I hope that your answer will break the clouds that hang over it."

So ran a part of the letter, colored somewhat by the diplomacy of a shrewd mother, one would say who read it carefully. The neighbors had heard of its arrival and many of them dropped in that evening, but they went home none the wiser. After the company had gone, Jack showed the letter to his father and mother.

"My boy, it is a time to stand firm," said his father.

"I think so, too," the boy answered.

"Are you still in love with her?" his mother asked.

The boy blushed as he looked down into the fire and did not answer.

"She is a pretty miss," the woman went on. "But if you have to choose between her and liberty, what will you say?"

"I can answer for Jack," said John Irons. "He will say that we in America will give up father and mother and home and life and everything we hold dear for the love of liberty."

"Of course I could not be a Tory," Jack declared. The boy had studiously read the books which Doctor Franklin had sent to him--Pilgrim's Progress, Plutarch's Lives, and a number of the works of Daniel Defoe. He had discussed them with his father and at the latter's suggestion had set down his impressions. His father had assured him that it was well done, but had said to Mrs. Irons that it showed "a remarkable rightness of mind and temper and unexpected aptitude in the art of expression."

It is likely that the boy wrote many letters which Miss Margaret never saw before his arguments were set down in the firm, gentle and winning tone which satisfied his spirit. Having finished his letter, at last, he read it aloud to his father and mother one evening as they sat together, by the fireside, after the rest of the family had gone to bed. Tears of pride came to the eyes of the man and woman when the long letter was finished.

"I love old England," it said, "because it is your home and because it was the home of my fathers. But I am sure it is not old England which made the laws we hate and sent soldiers to Boston. Is it not another England which the King and his ministers invented? I ask you to be true to old England which, my father has told me, stood for justice and human rights.

"But after all, what has politics to do with you and me as a pair of human beings? Our love is a thing above that. The acts of the King or my fellow countrymen can not affect my love for you, and to know that you are of the same mind holds me above despair. I would think it a great hardship if either King or colony had the power to put a tax on you--a tax which demanded my principles. Can not your father differ with me in politics--although when you were here I made sure that he agreed with us--and keep his faith in me as a gentleman? I can not believe that he would like me if I had a character so small and so easily shifted about that I would change it to please him. I am sure, too, that if there is anything in me you love, it is my character. Therefore, if I were to change it I should lose your love and his respect also. Is that not true?"

This was part of the letter which Jack had written.

"My boy, it is a good letter and they will have to like you the better for it," said John Irons.

Old Solomon Binkus was often at the Irons home those days. He had gone back in the bush, since the war ended, and, that winter, his traps were on many streams and ponds between Albany and Lake Champlain. He came down over the hills for a night with his friends when he reached the southern end of his beat. It was probably because the boy had loved the tales of the trapper and the trapper had found in the boy something which his life had missed, that an affection began to grow up between them. Solomon was a childless widower.

"My wife! I tell ye, sir, she had the eyes an' feet o' the young doe an' her cheeks were like the wild, red rose," the scout was wont to say on occasion. "I orto have knowed better. Yes, sir, I orto. We lived way back in the bush an' the child come 'fore we 'spected it one night. I done what I could but suthin' went wrong. They tuk the high trail, both on 'em. I rigged up a sled an' drawed their poor remains into a settlement. That were a hard walk--you hear to me. No, sir, I couldn't never marry no other womern--not if she was a queen covered with dimon's--never. I 'member her so. Some folks it's easy to fergit an' some it ain't. That's the way o' it."

Mr. and Mrs. Irons respected the scout, pitying his lonely plight and loving his cheerful company. He never spoke of his troubles unless some thoughtless person had put him to it.

That winter the Irons family and Solomon Binkus went often to the meetings of the Sons of Liberty. One purpose of this organization was to induce people to manufacture their own necessities and thus avoid buying the products of Great Britain. Factories were busy making looms and spinning-wheels; skilled men and women taught the arts of spinning, weaving and tailoring. The slogan "Home Made or Nothing," traveled far and wide.

Late in February, Jack Irons and Solomon Binkus went east as delegates to a large meeting of the Sons of Liberty in Springfield. They traveled on snowshoes and by stage, finding the bitterness of the people growing more intense as they proceeded. They found many women using thorns instead of pins and knitting one pair of stockings with the ravelings of another. They were also flossing out their silk gowns and spinning the floss into gloves with cotton. All this was to avoid buying goods sent over from Great Britain.

Jack tells in a letter to his mother of overtaking a young man with a pack on his back and an ax in his hand on his way to Harvard College. He was planning to work in a mill to pay his board and tuition.

"We hear in every house we enter the stories and maxims of Poor Richard," the boy wrote in his letter. "A number of them were quoted in the meeting. Doctor Franklin is everywhere these days."

The meeting over, Jack and Solomon went on by stage to Boston for a look at the big city.

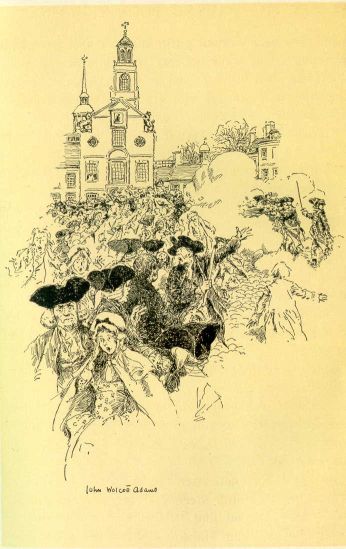

They arrived there on the fifth of March a little after dark. The moon was shining. A snow flurry had whitened the streets. The air was still and cold. They had their suppers at The Ship and Anchor. While they were eating they heard that a company of British soldiers who were encamped near the Presbyterian Meeting-House had beaten their drums on Sunday so that no worshiper could hear the preaching.

"And the worst of it is we are compelled to furnish them food and quarters while they insult and annoy us," said a minister who sat at the table.

After supper Jack and Solomon went out for a walk. They heard violent talk among people gathered at the street corners. They soon overtook a noisy crowd of boys and young men carrying clubs. In front of Murray's Barracks where the Twenty-Ninth Regiment was quartered, there was a chattering crowd of men and boys. Some of them were hooting and cursing at two sentinels. The streets were lighted by oil lamps and by candles in the windows of the houses.

In Cornhill they came upon a larger and more violent assemblage of the same kind. They made their way through it and saw beyond, a captain, a corporal and six private soldiers standing, face to face, with the crowd. Men were jeering at them; boys hurling abusive epithets. The boys, as they are apt to do, reflected, with some exaggeration, the passions of their elders. It was a crowd of rough fellows--mostly wharfmen and sailors. Solomon sensed the danger in the situation. He and Jack moved out of the jeering mob. Then suddenly a thing happened which may have saved one or both of their lives. The Captain drew his sword and flashed a dark light upon Solomon and called, out:

"Hello, Binkus! What the hell do you want?"

"Who be ye?" Solomon asked.

"Preston."

"Preston! Cat's blood an' gunpowder! What's the matter?"

Preston, an old comrade of Solomon, said to him:

"Go around to headquarters and tell them we are cut off by a mob and in a bad mess. I'm a little scared. I don't want to get hurt or do any hurting."

Jack and Solomon passed through the guard and hurried on. Then there were hisses and cries of "Tories! Rotten Tories!" As the two went on they heard missiles falling behind them and among the soldiers.

"They's goin' to be bad trouble thar," said Solomon.

"Them lads ain't to blame. They're only doin' as they're commanded. It's the dam' King that orto be hetchelled."

They were hurrying on, as he spoke, and the words were scarcely out of his mouth when they heard the command to fire and a rifle volley--then loud cries of pain and shrill curses and running feet. They turned and started back. People were rushing out of their houses, some with guns in their hands. In a moment the street was full.

"The soldiers are slaying people," a man shouted. "Men of Boston, we must arm ourselves and fight."

It was a scene of wild confusion. They could get no farther on Cornhill. The crowd began to pour into side-streets. Rumors were flying about that many had been killed and wounded. An hour or so later Jack and Solomon were seized by a group of ruffians.

"Here are the damn Tories!" one of them shouted.

"Friends o' murderers!" was the cry of another.

"Le's hang 'em!"

Solomon immediately knocked the man down who had called them Tories and seized another and tossed him so far in the crowd as to give it pause.

"I don't mind bein' hung," he shouted, "not if it's done proper, but no man kin call me a Tory lessen my hands are tied, without gittin' hurt. An' if my hands was tied I'd do some hollerin', now you hear to me."

A man back in the crowd let out a laugh as loud as the braying of an ass. Others followed his example. The danger was passed. Solomon shouted:

"I used to know Preston when I were a scout in Amherst's army fightin' Injuns an' Frenchmen, which they's more'n twenty notches on the stock o' my rifle an' fourteen on my pelt, an' my name is Solomon Binkus from Albany, New York, an' if you'll excuse us, we'll put fer hum as soon as we kin git erway convenient."

They started for The Ship and Anchor with a number of men and boys following and trying to talk with them.

"I'll tell ye, Jack, they's trouble ahead," said Solomon as they made their way through the crowded streets.

Many were saying that there could be no more peace with England.

In the morning they learned that three men had been killed and five others wounded by the soldiers. Squads of men and boys with loaded muskets were marching into town from the country.

Jack and Solomon attended the town meeting that day in the old South Meeting-House. It was a quiet and orderly crowd that listened to the speeches of Josiah Quincy, John Hancock and Samuel Adams, demanding calmly but firmly that the soldiers be forthwith removed from the city. The famous John Hancock cut a great figure in Boston those days. It is not surprising that Jack was impressed by his grandeur for he had entered the meeting-house in a scarlet velvet cap and a blue damask gown lined with velvet and strode to the platform with a dignity even above his garments. As he faced about the boy did not fail to notice and admire the white satin waistcoat and white silk stockings and red morocco slippers. Mr. Quincy made a statement which stuck like a bur in Jack Irons' memory of that day and perhaps all the faster because he did not quite understand it. The speaker said: "The dragon's teeth have been sown."

The chairman asked if there was any citizen present who had been on the scene at or about the time of the shooting. Solomon Binkus arose and held up his hand and was asked to go to the minister's room and confer with the committee.

Mr. John Adams called at the inn that evening and announced that he was to defend Captain Preston and would require the help of Jack and Solomon as witnesses. For that reason they were detained some days in Boston and released finally on the promise to return when their services were required.

They left Boston by stage and one evening in early April, traveling afoot, they saw the familiar boneheads around the pasture lands above Albany where the farmers had crowned their fence stakes with the skeleton heads of deer, moose, sheep and cattle in which birds had the habit of building their nests. It had been thawing for days, but the night had fallen clear and cold. They had stopped at the house of a settler some miles northeast of Albany to get a sled load of Solomon's pelts which had been stretched and hung there. Weary of the brittle snow, they took to the river a mile or so above the little city, Solomon hauling his sled. Jack had put on the new skates which he had bought in Bennington where they had gone for a visit with old friends. They were out on the clear ice, far from either shore, when they heard an alarming peal of "river thunder"--a name which Binkus applied to a curious phenomenon often accompanied by great danger to those on the rotted roof of the Hudson. The hidden water had been swelling.

Suddenly it had made a rip in the great ice vault a mile long with a noise like the explosion of a barrel of powder. The rip ran north and south about mid-stream. They were on the west sheet and felt it waver and subside till it had found a bearing on the river surface.

"We must git off o' here quick," said Binkus. "She's goin' to break up."

"Let me have the sled and as soon as I get going, you hop on," said Jack.

The boy began skating straight toward the shore, drawing the sled and its load, Solomon kicking out behind with his spiked boots until they were well under way. They heard the east sheet breaking up before they had made half the distance to safe footing. Then their own began to crack into sections as big "as a ten-acre lot," Mr. Binkus said, "an' the noise was like a battle, but Jack kept a-goin' an' me settin' light an' my mind a-pushin' like a scairt deer." Water was flooding over the ice which had broken near shore, but the skater jumped the crack before it was wider than a man's hand and took the sled with him. They reached the river's edge before the ice began heaving and there the sloped snow had been wet and frozen to rocks and bushes, so they were able to make their way through it.