This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net

Title: The Exiles and Other Stories

The Exiles; The Boy Orator of Zepata City; The Other Woman; On the Fever Ship; The Lion and the Unicorn; The Last Ride Together; Miss Delamar's Understudy; The Reporter Who Made Himself King

Author: Richard Harding Davis

Release Date: June 18, 2005 [eBook #16090]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE EXILES AND OTHER STORIES***

Instead she buried her face in its folds.

"The Exiles" and "The Boy Orator of Zepata City" from "The Exiles," copyright, 1894, by Harper & Brothers.

"The Other Woman" from "Gallagher," copyright, 1891, by Charles Scribner's Sons; "On the Fever Ship," "The Lion and the Unicorn," and "The Last Ride Together" from "The Lion and the Unicorn," copyright, 1899, by Charles Scribner's Sons; "Miss Delamar's Understudy" from "Cinderella," copyright, 1896, by Charles Scribner's Sons; "The Reporter Who Made Himself King" from "Stories for Boys," copyright, 1891, by Charles Scribner's Sons.

THE FIRST GLIMPSE OF DAVIS

Dick was twenty-four years old when he came into the smoking-room of the Victoria Hotel, in London, after midnight one July night—he was dressed as a Thames boatman.

He had been rowing up and down the river since sundown, looking for color. He had evidently peopled every dark corner with a pirate, and every floating object had meant something to him. He had adventure written all over him. It was the first time I had ever seen him, and I had never heard of him. I can't now recall another figure in that smoke-filled room. I don't remember who introduced us—over twenty-seven years have passed since that night. But I can see Dick now dressed in a rough brown suit, a soft hat, with a handkerchief about his neck, a splendid, healthy, clean-minded, gifted boy at play. And so he always remained.

His going out of this world seemed like a boy interrupted in a game he loved. And how well and fairly he played it! Surely no one deserved success more than Dick. And it is a consolation to know he had more than fifty years of just what he wanted. He had health, a great talent, and personal charm. There never was a more loyal or unselfish friend. There wasn't an atom of envy in him. He had unbounded mental and physical courage, and with it all he was sensitive and sometimes shy. He often tried to conceal these last two qualities, but never succeeded in doing so from those of us who were privileged really to know and love him.

His life was filled with just the sort of adventure he liked the best. No one ever saw more wars in so many different places or got more out of them. And it took the largest war in all history to wear out that stout heart.

We shall miss him.

CHARLES DANA GIBSON.

THE EXILES

I

The greatest number of people in the world prefer the most highly civilized places of the world, because they know what sort of things are going to happen there, and because they also know by experience that those are the sort of things they like. A very few people prefer barbarous and utterly uncivilized portions of the globe for the reason that they receive while there new impressions, and because they like the unexpected better than a routine of existence, no matter how pleasant that routine may be. But the most interesting places of all to study are those in which the savage and the cultivated man lie down together and try to live together in unity. This is so because we can learn from such places just how far a man of cultivation lapses into barbarism when he associates with savages, and how far the remnants of his former civilization will have influence upon the barbarians among whom he has come to live.

There are many such colonies as these, and they are the most picturesque plague-spots on the globe. You will find them in New Zealand and at Yokohama, in Algiers, Tunis, and Tangier, and scattered thickly all along the South American coast-line wherever the law of extradition obtains not, and where public opinion, which is one of the things a colony can do longest without, is unknown. These are the unofficial Botany Bays and Melillas of the world, where the criminal goes of his own accord, and not because his government has urged him to do so and paid his passage there. This is the story of a young man who went to such a place for the benefit he hoped it would be to his health, and not because he had robbed any one, or done a young girl an injury. He was the only son of Judge Henry Howard Holcombe, of New York. That was all that it was generally considered necessary to say of him. It was not, however, quite enough, for, while his father had had nothing but the right and the good of his State and country to think about, the son was further occupied by trying to live up to his father's name. Young Holcombe was impressed by this fact from his earliest childhood. It rested upon him while at Harvard and during his years at the law school, and it went with him into society and into the courts of law. When he rose to plead a case he did not forget, nor did those present forget, that his father while alive had crowded those same halls with silent, earnest listeners; and when he addressed a mass-meeting at Cooper Union, or spoke from the back of a cart in the East Side, some one was sure to refer to the fact that this last speaker was the son of the man who was mobbed because he had dared to be an abolitionist, and who later had received the veneration of a great city for his bitter fight against Tweed and his followers.

Young Holcombe was an earnest member of every reform club and citizens' league, and his distinguished name gave weight as a director to charitable organizations and free kindergartens. He had inherited his hatred of Tammany Hall, and was unrelenting in his war upon it and its handiwork, and he spoke of it and of its immediate downfall with the bated breath of one who, though amazed at the wickedness of the thing he fights, is not discouraged nor afraid. And he would listen to no half-measures. Had not his grandfather quarrelled with Henry Clay, and so shaken the friendship of a lifetime, because of a great compromise which he could not countenance? And was his grandson to truckle and make deals with this hideous octopus that was sucking the life-blood from the city's veins? Had he not but yesterday distributed six hundred circulars, calling for honest government, to six hundred possible voters, all the way up Fourth Avenue?—and when some flippant one had said that he might have hired a messenger-boy to have done it for him and so saved his energies for something less mechanical, he had rebuked the speaker with a reproachful stare and turned away in silence.

Life was terribly earnest to young Holcombe, and he regarded it from the point of view of one who looks down upon it from the judge's bench, and listens with a frown to those who plead its cause. He was not fooled by it; he was alive to its wickedness and its evasions. He would tell you that he knew for a fact that the window man in his district was a cousin of the Tammany candidate, and that the contractor who had the cleaning of the street to do was a brother-in-law of one of the Hall's sachems, and that the policeman on his beat had not been in the country eight months. He spoke of these damning facts with the air of one who simply tells you that much, that you should see how terrible the whole thing really was, and what he could tell if he wished.

In his own profession he recognized the trials of law-breakers only as experiments which went to establish and explain a general principle. And prisoners were not men to him, but merely the exceptions that proved the excellence of a rule. Holcombe would defend the lowest creature or the most outrageous of murderers, not because the man was a human being fighting for his liberty or life, but because he wished to see if certain evidence would be admitted in the trial of such a case. Of one of his clients the judge, who had a daughter of his own, said, when he sentenced him, "Were there many more such men as you in the world, the women of this land would pray to God to be left childless." And when some one asked Holcombe, with ill-concealed disgust, how he came to defend the man, he replied: "I wished to show the unreliability of expert testimony from medical men. Yes; they tell me the man was a very bad lot."

It was measures, not men, to Holcombe, and law and order were his twin goddesses, and "no compromise" his watchword.

"You can elect your man if you'll give me two thousand dollars to refit our club-room with," one of his political acquaintances once said to him. "We've five hundred voters on the rolls now, and the members vote as one man. You'd be saving the city twenty times that much if you keep Croker's man out of the job. You know that as well as I do."

"The city can better afford to lose twenty thousand dollars," Holcombe answered, "than we can afford to give a two-cent stamp for corruption."

"All right," said the heeler; "all right, Mr. Holcombe. Go on. Fight 'em your own way. If they'd agree to fight you with pamphlets and circulars you'd stand a chance, sir; but as long as they give out money and you give out reading-matter to people that can't read, they'll win, and I naturally want to be on the winning side."

When the club to which Holcombe belonged finally succeeded in getting the Police Commissioners indicted for blackmailing gambling-houses, Holcombe was, as a matter of course and of public congratulation, on the side of the law; and as Assistant District Attorney—a position given him on account of his father's name and in the hope that it would shut his mouth—distinguished himself nobly.

Of the four commissioners, three were convicted—the fourth, Patrick Meakim, with admirable foresight having fled to that country from which few criminals return, and which is vaguely set forth in the newspapers as "parts unknown."

The trial had been a severe one upon the zealous Mr. Holcombe, who found himself at the end of it in a very bad way, with nerves unstrung and brain so fagged that he assented without question when his doctor exiled him from New York by ordering a sea voyage, with change of environment and rest at the other end of it. Some one else suggested the northern coast of Africa and Tangier, and Holcombe wrote minute directions to the secretaries of all of his reform clubs urging continued efforts on the part of his fellow-workers, and sailed away one cold winter's morning for Gibraltar. The great sea laid its hold upon him, and the winds from the south thawed the cold in his bones, and the sun cheered his tired spirit. He stretched himself at full length reading those books which one puts off reading until illness gives one the right to do so, and so far as in him lay obeyed his doctor's first command, that he should forget New York and all that pertained to it. By the time he had reached the Rock he was up and ready to drift farther into the lazy, irresponsible life of the Mediterranean coast, and he had forgotten his struggles against municipal misrule, and was at times for hours together utterly oblivious of his own personality.

A dumpy, fat little steamer rolled itself along like a sailor on shore from Gibraltar to Tangier, and Holcombe, leaning over the rail of its quarter-deck, smiled down at the chattering group of Arabs and Moors stretched on their rugs beneath him. A half-naked negro, pulling at the dates in the basket between his bare legs, held up a handful to him with a laugh, and Holcombe laughed back and emptied the cigarettes in his case on top of him, and laughed again as the ship's crew and the deck passengers scrambled over one another and shook out their voluminous robes in search of them. He felt at ease with the world and with himself, and turned his eyes to the white walls of Tangier with a pleasure so complete that it shut out even the thought that it was a pleasure.

The town seemed one continuous mass of white stucco, with each flat, low-lying roof so close to the other that the narrow streets left no trace. To the left of it the yellow coastline and the green olive-trees and palms stretched up against the sky, and beneath him scores of shrieking blacks fought in their boats for a place beside the steamer's companion-way. He jumped into one of these open wherries and fell sprawling among his baggage, and laughed lightly as a boy as the boatman set him on his feet again, and then threw them from under him with a quick stroke of the oars. The high, narrow pier was crowded with excited customs officers in ragged uniforms and dirty turbans, and with a few foreign residents looking for arriving passengers. Holcombe had his feet on the upper steps of the ladder, and was ascending slowly. There was a fat, heavily built man in blue serge leaning across the railing of the pier. He was looking down, and as his eyes met Holcombe's face his own straightened into lines of amazement and most evident terror. Holcombe stopped at the sight, and stared back wondering. And then the lapping waters beneath him and the white town at his side faded away, and he was back in the hot, crowded court-room with this man's face before him. Meakim, the fourth of the Police Commissioners, confronted him, and saw in his presence nothing but a menace to himself.

Holcombe came up the last steps of the stairs, and stopped at their top. His instinct and life's tradition made him despise the man, and to this was added the selfish disgust that his holiday should have been so soon robbed of its character by this reminder of all that he had been told to put behind him.

Meakim swept off his hat as though it were hurting him, and showed the great drops of sweat on his forehead.

"For God's sake!" the man panted, "you can't touch me here, Mr. Holcombe. I'm safe here; they told me I'd be. You can't take me. You can't touch me."

Holcombe stared at the man coldly, and with a touch of pity and contempt. "That is quite right, Mr. Meakim," he said. "The law cannot reach you here."

"Then what do you want with me?" the man demanded, forgetful in his terror of anything but his own safety.

Holcombe turned upon him sharply. "I am not here on your account, Mr. Meakim," he said. "You need not feel the least uneasiness, and," he added, dropping his voice as he noticed that others were drawing near, "if you keep out of my way, I shall certainly keep out of yours."

The Police Commissioner gave a short laugh partly of bravado and partly at his own sudden terror. "I didn't know," he said, breathing with relief. "I thought you'd come after me. You don't wonder you give me a turn, do you? I was scared." He fanned himself with his straw hat, and ran his tongue over his lips. "Going to be here some time, Mr. District Attorney?" he added, with grave politeness.

Holcombe could not help but smile at the absurdity of it. It was so like what he would have expected of Meakim and his class to give every office-holder his full title. "No, Mr. Police Commissioner," he answered, grimly, and nodding to his boatmen, pushed his way after them and his trunks along the pier.

Meakim was waiting for him as he left the custom-house. He touched his hat, and bent the whole upper part of his fat body in an awkward bow. "Excuse me, Mr. District Attorney," he began.

"Oh, drop that, will you?" snapped Holcombe. "Now, what is it you want, Meakim?"

"I was only going to say," answered the fugitive, with some offended dignity, "that as I've been here longer than you, I could perhaps give you pointers about the hotels. I've tried 'em all, and they're no good, but the Albion's the best."

"Thank you, I'm sure," said Holcombe. "But I have been told to go to the Isabella."

"Well, that's pretty good, too," Meakim answered, "if you don't mind the tables. They keep you awake most of the night, though, and—"

"The tables? I beg your pardon," said Holcombe, stiffly.

"Not the eatin' tables; the roulette tables," corrected Meakim. "Of course," he continued, grinning, "if you're fond of the game, Mr. Holcombe, it's handy having them in the same house, but I can steer you against a better one back of the French Consulate. Those at the Hotel Isabella's crooked."

Holcombe stopped uncertainly. "I don't know just what to do," he said. "I think I shall wait until I can see our consul here."

"Oh, he'll send you to the Isabella," said Meakim, cheerfully. "He gets two hundred dollars a week for protecting the proprietor, so he naturally caps for the house."

Holcombe opened his mouth to express himself, but closed it again, and then asked, with some misgivings, of the hotel of which Meakim had first spoken.

"Oh, the Albion. Most all the swells go there. It's English, and they cook you a good beefsteak. And the boys generally drop in for table d'hôte. You see, that's the worst of this place, Mr. Holcombe; there's nowhere to go evenings—no club-rooms nor theatre nor nothing; only the smoking-room of the hotel or that gambling-house; and they spring a double naught on you if there's more than a dollar up."

Holcombe still stood irresolute, his porters eying him from under their burdens, and the runners from the different hotels plucking at his sleeve.

"There's some very good people at the Albion," urged the Police Commissioner, "and three or four of 'em's New-Yorkers. There's the Morrises and Ropes, the Consul-General, and Lloyd Carroll—"

"Lloyd Carroll!" exclaimed Holcombe.

"Yes," said Meakim, with a smile, "he's here." He looked at Holcombe curiously for a moment, and then exclaimed, with a laugh of intelligence, "Why, sure enough, you were Mr. Thatcher's lawyer in that case, weren't you? It was you got him his divorce?"

Holcombe nodded.

"Carroll was the man that made it possible, wasn't he?"

Holcombe chafed under this catechism. "He was one of a dozen, I believe," he said; but as he moved away he turned and asked: "And Mrs. Thatcher. What has become of her?"

The Police Commissioner did not answer at once, but glanced up at Holcombe from under his half-shut eyes with a look in which there was a mixture of curiosity and of amusement. "You don't mean to say, Mr. Holcombe," he began, slowly, with the patronage of the older man and with a touch of remonstrance in his tone, "that you're still with the husband in that case?"

Holcombe looked coldly over Mr. Meakim's head. "I have only a purely professional interest in any one of them," he said. "They struck me as a particularly nasty lot. Good-morning, sir."

"Well," Meakim called after him, "you needn't see nothing of them if you don't want to. You can get rooms to yourself."

Holcombe did get rooms to himself, with a balcony overlooking the bay, and arranged with the proprietor of the Albion to have his dinner served at a separate table. As others had done this before, no one regarded it as an affront upon his society, and several people in the hotel made advances to him, which he received politely but coldly. For the first week of his visit the town interested him greatly, increasing its hold upon him unconsciously to himself. He was restless and curious to see it all, and rushed his guide from one of the few show-places to the next with an energy which left that fat Oriental panting.

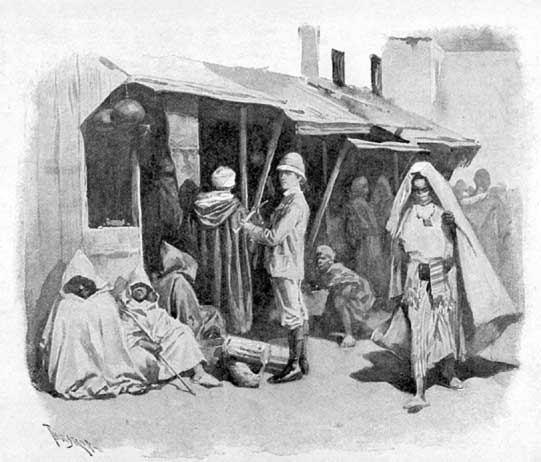

Stopping for half-hours at a time before a bazaar.

But after three days Holcombe climbed the streets more leisurely, stopping for half-hours at a time before a bazaar, or sent away his guide altogether, and stretched himself luxuriously on the broad wall of the fortifications. The sun beat down upon him, and wrapped him into drowsiness. From far afield came the unceasing murmur of the market-place and the bazaars, and the occasional cries of the priests from the minarets; the dark blue sea danced and flashed beyond the white margin of the town and its protecting reef of rocks where the sea-weed rose and fell, and above his head the buzzards swept heavily, and called to one another with harsh, frightened cries. At his side lay the dusty road, hemmed in by walls of cactus, and along its narrow length came lines of patient little donkeys with jangling necklaces, led by wild-looking men from the farm-lands and the desert, and women muffled and shapeless, with only their bare feet showing, who looked at him curiously or meaningly from over the protecting cloth, and passed on, leaving him startled and wondering. He began to find that the books he had brought wearied him. The sight of the type alone was enough to make him close the covers and start up restlessly to look for something less absorbing. He found this on every hand, in the lazy patience of the bazaars and of the markets, where the chief service of all was that of only standing and waiting, and in the farm-lands behind Tangier, where half-naked slaves drove great horned buffalo, and turned back the soft, chocolate-colored sod with a wooden plough. But it was a solitary, selfish holiday, and Holcombe found himself wanting certain ones at home to bear him company, and was surprised to find that of these none were the men nor the women with whom his interests in the city of New York were the most closely connected. They were rather foolish people, men at whom he had laughed and whom he had rather pitied for having made him do so, and women he had looked at distantly as of a kind he might understand when his work was over and he wished to be amused. The young girls to whom he was in the habit of pouring out his denunciations of evil, and from whom he was accustomed to receive advice and moral support, he could not place in this landscape. He felt uneasily that they would not allow him to enjoy it his own way; they would consider the Moor historically as the invader of Catholic Europe, and would be shocked at the lack of proper sanitation, and would see the mud. As for himself, he had risen above seeing the mud. He looked up now at the broken line of the roof-tops against the blue sky, and when a hooded figure drew back from his glance he found himself murmuring the words of an Eastern song he had read in a book of Indian stories:

"Alone upon the house-tops, to the north

I turn and watch the lightning in the sky,—

The glamour of thy footsteps in the north.

Come back to me, Beloved, or I die!

"Below my feet the still bazaar is laid.

Far, far below, the weary camels lie—"

Holcombe laughed and shrugged his shoulders. He had stopped half-way down the hill on which stands the Bashaw's palace, and the whole of Tangier lay below him like a great cemetery of white marble. The moon was shining clearly over the town and the sea, and a soft wind from the sandy farm-lands came to him and played about him like the fragrance of a garden. Something moved in him that he did not recognize, but which was strangely pleasant, and which ran to his brain like the taste of a strong liqueur. It came to him that he was alone among strangers, and that what he did now would be known but to himself and to these strangers. What it was that he wished to do he did not know, but he felt a sudden lifting up and freedom from restraint. The spirit of adventure awoke in him and tugged at his sleeve, and he was conscious of a desire to gratify it and put it to the test.

"'Alone upon the house-tops,'" he began. Then he laughed and clambered hurriedly down the steep hill-side. "It's the moonlight," he explained to the blank walls and overhanging lattices, "and the place and the music of the song. It might be one of the Arabian nights, and I Haroun al Raschid. And if I don't get back to the hotel I shall make a fool of myself."

He reached the Albion very warm and breathless, with stumbling and groping in the dark, and instead of going immediately to bed told the waiter to bring him some cool drink out on the terrace of the smoking-room. There were two men sitting there in the moonlight, and as he came forward one of them nodded to him silently.

"Oh, good-evening, Mr. Meakim!" Holcombe said, gayly, with the spirit of the night still upon him. "I've been having adventures." He laughed, and stooped to brush the dirt from his knickerbockers and stockings. "I went up to the palace to see the town by moonlight, and tried to find my way back alone, and fell down three times."

Meakim shook his head gravely. "You'd better be careful at night, sir," he said. "The governor has just said that the Sultan won't be responsible for the lives of foreigners at night 'unless accompanied by soldier and lantern.'"

"Yes, and the legations sent word that they wouldn't have it," broke in the other man. "They said they'd hold him responsible anyway."

There was a silence, and Meakim moved in some slight uneasiness. "Mr. Holcombe, do you know Mr. Carroll?" he said.

Carroll half rose from his chair, but Holcombe was dragging another toward him, and so did not have a hand to give him.

"How are you, Carroll?" he said, pleasantly.

The night was warm, and Holcombe was tired after his rambles, and so he sank back in the low wicker chair contentedly enough, and when the first cool drink was finished he clapped his hands for another, and then another, while the two men sat at the table beside him and avoided such topics as would be unfair to any of them.

"And yet," said Holcombe, after the first half-hour had passed, "there must be a few agreeable people here. I am sure I saw some very nice-looking women to-day coming in from the fox-hunt. And very well gotten up, too, in Karki habits. And the men were handsome, decent-looking chaps—Englishmen, I think."

"Who does he mean? Were you at the meet to-day?" asked Carroll.

The Tammany chieftain said no, that he did not ride—not after foxes, in any event. "But I saw Mrs. Hornby and her sister coming back," he said. "They had on those linen habits."

"Well, now, there's a woman who illustrates just what I have been saying," continued Carroll. "You picked her out as a self-respecting, nice-looking girl—and so she is—but she wouldn't like to have to tell all she knows. No, they are all pretty much alike. They wear low-neck frocks, and the men put on evening dress for dinner, and they ride after foxes, and they drop in to five-o'clock tea, and they all play that they're a lot of gilded saints, and it's one of the rules of the game that you must believe in the next man, so that he will believe in you. I'm breaking the rules myself now, because I say 'they' when I ought to say 'we.' We're none of us here for our health, Holcombe, but it pleases us to pretend we are. It's a sort of give and take. We all sit around at dinner-parties and smile and chatter, and those English talk about the latest news from 'town,' and how they mean to run back for the season or the hunting. But they know they don't dare go back, and they know that everybody at the table knows it, and that the servants behind them know it. But it's more easy that way. There's only a few of us here, and we've got to hang together or we'd go crazy."

"That's so," said Meakim, approvingly. "It makes it more sociable."

"It's a funny place," continued Carroll. The wine had loosened his tongue, and it was something to him to be able to talk to one of his own people again, and to speak from their point of view, so that the man who had gone through St. Paul's and Harvard with him would see it as such a man should. "It's a funny place, because, in spite of the fact that it's a prison, you grow to like it for its freedom. You can do things here you can't do in New York, and pretty much everything goes there, or it used to, where I hung out. But here you're just your own master, and there's no law and no religion and no relations nor newspapers to poke into what you do nor how you live. You can understand what I mean if you've ever tried living in the West. I used to feel the same way the year I was ranching in Texas. My family sent me out there to put me out of temptation; but I concluded I'd rather drink myself to death on good whiskey at Del's than on the stuff we got on the range, so I pulled my freight and came East again. But while I was there I was a little king. I was just as good as the next man, and he was no better than me. And though the life was rough, and it was cold and lonely, there was something in being your own boss that made you stick it out there longer than anything else did. It was like this, Holcombe." Carroll half rose from his chair and marked what he said with his finger. "Every time I took a step and my gun bumped against my hip, I'd straighten up and feel good and look for trouble. There was nobody to appeal to; it was just between me and him, and no one else had any say about it. Well, that's what it's like here. You see men come to Tangier on the run, flying from detectives or husbands or bank directors, men who have lived perfectly decent, commonplace lives up to the time they made their one bad break—which," Carroll added, in polite parenthesis, with a deprecatory wave of his hand toward Meakim and himself, "we are all likely to do some time, aren't we?"

"Just so," said Meakim.

"Of course," assented the District Attorney.

"But as soon as he reaches this place, Holcombe," continued Carroll, "he begins to show just how bad he is. It all comes out—all his viciousness and rottenness and blackguardism. There is nothing to shame it, and there is no one to blame him, and no one is in a position to throw the first stone." Carroll dropped his voice and pulled his chair forward with a glance over his shoulder. "One of those men you saw riding in from the meet to-day. Now, he's a German officer, and he's here for forging a note or cheating at cards or something quiet and gentlemanly, nothing that shows him to be a brute or a beast. But last week he had old Mulley Wazzam buy him a slave girl in Fez, and bring her out to his house in the suburbs. It seems that the girl was in love with a soldier in the Sultan's body-guard at Fez, and tried to run away to join him, and this man met her quite by accident as she was making her way south across the sand-hills. He was whip that day, and was hurrying out to the meet alone. He had some words with the girl first, and then took his whip—it was one of those with the long lash to it; you know what I mean—and cut her to pieces with it, riding her down on his pony when she tried to run, and heading her off and lashing her around the legs and body until she fell; then he rode on in his damn pink coat to join the ladies at Mango's Drift, where the meet was, and some Riffs found her bleeding to death behind the sand-hills. That man held a commission in the Emperor's own body-guard, and that's what Tangier did for him."

Holcombe glanced at Meakim to see if he would verify this, but Meakim's lips were tightly pressed around his cigar, and his eyes were half closed.

"And what was done about it?" Holcombe asked, hoarsely.

Carroll laughed, and shrugged his shoulders. "Why, I tell you, and you whisper it to the next man, and we pretend not to believe it, and call the Riffs liars. As I say, we're none of us here for our health, Holcombe, and a public opinion that's manufactured by déclassée women and men who have run off with somebody's money and somebody's else's wife isn't strong enough to try a man for beating his own slave."

"But the Moors themselves?" protested Holcombe. "And the Sultan? She's one of his subjects, isn't she?"

"She's a woman, and women don't count for much in the East, you know; and as for the Sultan, he's an ignorant black savage. When the English wanted to blow up those rocks off the western coast, the Sultan wouldn't let them. He said Allah had placed them there for some good reason of His own, and it was not for man to interfere with the works of God. That's the sort of a Sultan he is." Carroll rose suddenly and walked into the smoking-room, leaving the two men looking at each other in silence.

"That's right," said Meakim, after a pause. "He give it to you just as it is, but I never knew him to kick about it before. We're a fair field for missionary work, Mr. Holcombe, all of us—at least, some of us are." He glanced up as Carroll came back from out of the lighted room with an alert, brisk step. His manner had changed in his absence.

"Some of the ladies have come over for a bit of supper," he said. "Mrs. Hornby and her sister and Captain Reese. The chef's got some birds for us, and I've put a couple of bottles on ice. It will be like Del's—hey? A small hot bird and a large cold bottle. They sent me out to ask you to join us. They're in our rooms." Meakim rose leisurely and lit a fresh cigar, but Holcombe moved uneasily in his chair. "You'll come, won't you?" Carroll asked. "I'd like you to meet my wife."

Holcombe rose irresolutely and looked at his watch. "I'm afraid it's too late for me," he said, without raising his face. "You see, I'm here for my health. I—"

"I beg your pardon," said Carroll, sharply.

"Nonsense, Carroll!" said Holcombe. "I didn't mean that. I meant it literally. I can't risk midnight suppers yet. My doctor's orders are to go to bed at nine, and it's past twelve now. Some other time, if you'll be so good; but it's long after my bedtime, and—"

"Oh, certainly," said Carroll, quietly, as he turned away. "Are you coming, Meakim?"

Meakim lifted his half-empty glass from the table and tasted it slowly until Carroll had left them, then he put the glass down, and glanced aside to where Holcombe sat looking out over the silent city. Holcombe raised his eyes and stared at him steadily.

"Mr. Holcombe—" the fugitive began.

"Yes," replied the lawyer.

Meakim shook his head. "Nothing," he said. "Good-night, sir."

Holcombe's rooms were on the floor above Carroll's, and the laughter of the latter's guests and the tinkling of glasses and silver came to him as he stepped out upon his balcony. But for this the night was very still. The sea beat leisurely on the rocks, and the waves ran up the sandy coast with a sound as of some one sweeping. The music of women's laughter came up to him suddenly, and he wondered hotly if they were laughing at him. He assured himself that it was a matter of indifference to him if they were. And with this he had a wish that they would not think of him as holding himself aloof. One of the women began to sing to a guitar, and to the accompaniment of this a man and a young girl came out upon the balcony below, and spoke to each other in low, earnest tones, which seemed to carry with them the feeling of a caress. Holcombe could not hear what they said, but he could see the curve of the woman's white shoulders and the light of her companion's cigar as he leaned upon the rail with his back to the moonlight and looked into her face. Holcombe felt a sudden touch of loneliness and of being very far from home. He shivered slightly as though from the cold, and stepping inside closed the window gently behind him.

Although Holcombe met Carroll several times during the following day, the latter obviously avoided him, and it was not until late in the afternoon that Holcombe was given a chance to speak to him again. Carroll was coming down the only street on a run, jumping from one rough stone to another, and with his face lighted up with excitement. He hailed Holcombe from a distance with a wave of the hand. "There's an American man-of-war in the bay," he cried; "one of the new ones. We saw her flag from the hotel. Come on!" Holcombe followed as a matter of course, as Carroll evidently expected that he would, and they reached the end of the landing-pier together, just as the ship of war ran up and broke the square red flag of Morocco from her main-mast and fired her salute.

"They'll be sending a boat in by-and-by," said Carroll, "and we'll have a talk with the men." His enthusiasm touched his companion also, and the sight of the floating atom of the great country that was his moved him strongly, as though it were a personal message from home. It came to him like the familiar stamp, and a familiar handwriting on a letter in a far-away land, and made him feel how dear his own country was to him and how much he needed it. They were leaning side by side upon the rail watching the ship's screws turning the blue waters white, and the men running about the deck, and the blue-coated figures on the bridge. Holcombe turned to point out the vessel's name to Carroll, and found that his companion's eyes were half closed and filled with tears.

Carroll laughed consciously and coughed. "We kept it up a bit too late last night," he said, "and I'm feeling nervous this morning, and the sight of the flag and those boys from home knocked me out." He paused for a moment, frowning through his tears and with his brow drawn up into many wrinkles. "It's a terrible thing, Holcombe," he began again, fiercely, "to be shut off from all of that." He threw out his hand with a sudden gesture toward the man-of-war. Holcombe looked down at the water and laid his hand lightly on his companion's shoulder. Carroll drew away and shook his head. "I don't want any sympathy," he said, kindly. "I'm not crying the baby act. But you don't know, and I don't believe anybody else knows, what I've gone through and what I've suffered. You don't like me, Holcombe, and you don't like my class, but I want to tell you something about my coming here. I want you to set them right about it at home. And I don't care whether it interests you or not," he said, with quick offense; "I want you to listen. It's about my wife."

Holcombe bowed his head gravely.

"You got Thatcher his divorce," Carroll continued. "And you know that he would never have got it but for me, and that everybody expected that I would marry Mrs. Thatcher when the thing was over. And I didn't, and everybody said I was a blackguard, and I was. It was bad enough before, but I made it worse by not doing the only thing that could make it any better. Why I didn't do it I don't know. I had some grand ideas of reform about that time, I think, and I thought I owed my people something, and that by not making Mrs. Thatcher my mother's daughter I would be saving her and my sisters. It was remorse, I guess, and I didn't see things straight. I know now what I should have done. Well, I left her and she went her own way, and a great many people felt sorry for her, and were good to her—not your people, nor my people; but enough were good to her to make her see as much of the world as she had used to. She never loved Thatcher, and she never loved any of the men you brought into that trial except one, and he treated her like a cur. That was myself. Well, what with trying to please my family, and loving Alice Thatcher all the time and not seeing her, and hating her too for bringing me into all that notoriety—for I blamed the woman, of course, as a man always will—I got to drinking, and then this scrape came and I had to run. I don't care anything about that row now, or what you believe about it. I'm here, shut off from my home, and that's a worse punishment than any damn lawyers can invent. And the man's well again. He saw I was drunk; but I wasn't so drunk that I didn't know he was trying to do me, and I pounded him just as they say I did, and I'm sorry now I didn't kill him."

Holcombe stirred uneasily, and the man at his side lowered his voice and went on more calmly:

"If I hadn't been a gentleman, Holcombe, or if it had been another cabman he'd fought with, there wouldn't have been any trouble about it. But he thought he could get big money out of me, and his friends told him to press it until he was paid to pull out, and I hadn't the money, and so I had to break bail and run. Well, you've seen the place. You've been here long enough to know what it's like, and what I've had to go through. Nobody wrote me, and nobody came to see me; not one of my own sisters even, though they've been in the Riviera all this spring—not a day's journey away. Sometimes a man turned up that I knew, but it was almost worse than not seeing any one. It only made me more homesick when he'd gone. And for weeks I used to walk up and down that beach there alone late in the night, until I got to thinking that the waves were talking to me, and I got queer in my head. I had to fight it just as I used to have to fight against whiskey, and to talk fast so that I wouldn't think. And I tried to kill myself hunting, and only got a broken collar-bone for my pains. Well, all this time Alice was living in Paris and New York. I heard that some English captain was going to marry her, and then I read in the Paris Herald that she was settled in the American colony there, and one day it gave a list of the people who'd been to a reception she gave. She could go where she pleased, and she had money in her own right, you know; and she was being revenged on me every day. And I was here knowing it, and loving her worse than I ever loved anything on earth, and having lost the right to tell her so, and not able to go to her. Then one day some chap turned up from here and told her about me, and about how miserable I was, and how well I was being punished. He thought it would please her, I suppose. I don't know who he was, but I guess he was in love with her himself. And then the papers had it that I was down with the fever here, and she read about it. I was ill for a time, and I hoped it was going to carry me off decently, but I got up in a week or two, and one day I crawled down here where we're standing now to watch the boat come in. I was pretty weak from my illness, and I was bluer than I had ever been, and I didn't see anything but blackness and bitterness for me anywhere. I turned around when the passengers reached the pier, and I saw a woman coming up those stairs. Her figure and her shoulders were so like Alice's that my heart went right up into my throat, and I couldn't breathe for it. I just stood still staring, and when she reached the top of the steps she looked up, breathing with the climb, and laughing; and she says, 'Lloyd, I've come to see you.' And I—I was that lonely and weak that I grabbed her hand, and leaned back against the railing, and cried there before the whole of them. I don't think she expected it exactly, because she didn't know what to do, and just patted me on the shoulder, and said, 'I thought I'd run down to cheer you up a bit; and I've brought Mrs. Scott with me to chaperon us.' And I said, without stopping to think: 'You wouldn't have needed any chaperon, Alice, if I hadn't been a cur and a fool. If I had only asked what I can't ask of you now'; and, Holcombe, she flushed just like a little girl, and laughed, and said, 'Oh, will you, Lloyd?' And you see that ugly iron chapel up there, with the corrugated zinc roof and the wooden cross on it, next to the mosque? Well, that's where we went first, right from this wharf before I let her go to a hotel, and old Ridley, the English rector, he married us, and we had a civil marriage too. That's what she did for me. She had the whole wide globe to live in, and she gave it up to come to Tangier, because I had no other place but Tangier, and she's made my life for me, and I'm happier here than I ever was before anywhere, and sometimes I think—I hope—that she is, too." Carroll's lips moved slightly, and his hands trembled on the rail. He coughed, and his voice was gentler when he spoke again. "And so," he added, "that's why I felt it last night when you refused to meet her. You were right, I know, from your way of thinking, but we've grown careless down here, and we look at things differently."

Holcombe did not speak, but put his arm across the other's shoulder, and this time Carroll did not shake it off. Holcombe pointed with his hand to a tall, handsome woman with heavy yellow hair who was coming toward them, with her hands in the pockets of her reefer. "There is Mrs. Carroll now," he said. "Won't you present me, and then we can row out and see the man-of-war?"

II

The officers returned their visit during the day, and the American Consul-General asked them all to a reception the following afternoon. The entire colony came to this, and Holcombe met many people, and drank tea with several ladies in riding-habits, and iced drinks with all of the men. He found it very amusing, and the situation appealed strongly to his somewhat latent sense of humor. That evening in writing to his sister he told of his rapid recovery in health, and of the possibility of his returning to civilization.

"There was a reception this afternoon at the Consul-General's," he wrote, "given to the officers of our man-of-war, and I found myself in some rather remarkable company. The Consul himself has become rich by selling his protection for two hundred dollars to every wealthy Moor who wishes to escape the forced loans which the Sultan is in the habit of imposing on the faithful. For five hundred dollars he will furnish any one of them with a piece of stamped paper accrediting him as minister plenipotentiary from the United States to the Sultan's court. Of course the Sultan never receives them, and whatever object they may have had in taking the long journey to Fez is never accomplished. Some day some one of them will find out how he has been tricked, and will return to have the Consul assassinated. This will be a serious loss to our diplomatic service. The Consul's wife is a fat German woman who formerly kept a hotel here. Her brother has it now, and runs it as an annex to a gambling-house. Pat Meakim, the Police Commissioner that I indicted, but who jumped his bail, introduced me at the reception to the men, with apparently great self-satisfaction, as 'the pride of the New York Bar,' and Mrs. Carroll, for whose husband I obtained a divorce, showed her gratitude by presenting me to the ladies. It was a distinctly Gilbertian situation, and the people to whom they introduced me were quite as picturesquely disreputable as themselves. So you see—"

Holcombe stopped here and read over what he had written, and then tore up the letter. The one he sent in its place said he was getting better, but that the climate was not so mild as he had expected it would be.

Holcombe engaged the entire first floor of the hotel the next day, and entertained the officers and the residents at breakfast, and the Admiral made a speech and said how grateful it was to him and to his officers to find that wherever they might touch, there were some few Americans ready to welcome them as the representatives of the flag they all so unselfishly loved, and of the land they still so proudly called "home." Carroll, turning his wine-glass slowly between his fingers, raised his eyes to catch Holcombe's, and winked at him from behind the curtain of the smoke of his cigar, and Holcombe smiled grimly, and winked back, with the result that Meakim, who had intercepted the signalling, choked on his champagne, and had to be pounded violently on the back. Holcombe's breakfast established him as a man of means and one who could entertain properly, and after that his society was counted upon for every hour of the day. He offered money as prizes for the ship's crew to row and swim after, he gave a purse for a cross-country pony race, open to members of the Calpe and Tangier hunts, and organized picnics and riding parties innumerable. He was forced at last to hire a soldier to drive away the beggars when he walked abroad. He found it easy to be rich in a place where he was given over two hundred copper coins for an English shilling, and he distributed his largesses recklessly and with a lack of discrimination entirely opposed to the precepts of his organized charities at home. He found it so much more amusing to throw a handful of coppers to a crowd of fat naked children than to write a check for the Society for Suppression of Cruelty to the same beneficiaries.

"You shouldn't give those fellows money," the Consul-General once remonstrated with him; "the fact that they're blind is only a proof that they have been thieves. When they catch a man stealing here they hold his head back, and pass a hot iron in front of his eyes. That's why the lids are drawn taut that way. You shouldn't encourage them."

"Perhaps they're not all thieves," said the District Attorney, cheerfully, as he hit the circle around him with a handful of coppers; "but there is no doubt about it that they're all blind. Which is the more to be pitied," he asked the Consul-General, "the man who has still to be found out and who can see, or the one who has been exposed and who is blind?"

"How should he know?" said Carroll, laughing. "He's never been blind, and he still holds his job."

"I don't think that's very funny," said the Consul-General.

A week of pig-sticking came to end Holcombe's stay in Tangier, and he threw himself into it and into the freedom of its life with a zest that made even the Englishman speak of him as a good fellow. He chanced to overhear this, and stopped to consider what it meant. No one had ever called him a good fellow at home, but then his life had not offered him the chance to show what sort of a good fellow he might be, and as Judge Holcombe's son certain things had been debarred him. Here he was only the richest tourist since Farwell, the diamond smuggler from Amsterdam, had touched there in his yacht.

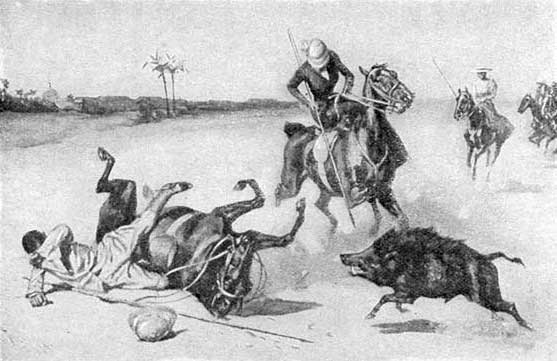

The boar hunt.

The week of boar-hunting was spent out-of-doors, on horseback, and in tents; the women in two wide circular ones, and the men in another, with a mess tent, which they shared in common, pitched between them. They had only one change of clothes each, one wet and one dry, and they were in the saddle from nine in the morning until late at night, when they gathered in a wide circle around the wood-fire and played banjoes and listened to stories. Holcombe grew as red as a sailor, and jumped his horse over gaping crevasses in the hard sun-baked earth as recklessly as though there were nothing in this world so well worth sacrificing one's life for as to be the first in at a dumb brute's death. He was on friendly terms with them all now—with Miss Terrill, the young girl who had been awakened by night and told to leave Monte Carlo before daybreak, and with Mrs. Darhah, who would answer to Lady Taunton if so addressed, and with Andrews, the Scotch bank clerk, and Ollid the boy officer from Gibraltar, who had found some difficulty in making the mess account balance. They were all his very good friends, and he was especially courteous and attentive to Miss Terrill's wants and interests, and fixed her stirrup and once let her pass him to charge the boar in his place. She was a silently distant young woman, and strangely gentle for one who had had to leave a place, and such a place, between days; and her hair, which was very fine and light, ran away from under her white helmet in disconnected curls. At night, Holcombe used to watch her from out of the shadow when the firelight lit up the circle and the tips of the palms above them, and when the story-teller's voice was accompanied by bursts of occasional laughter from the dragomen in the grove beyond, and the stamping and neighing of the horses at their pickets, and the unceasing chorus of the insect life about them. She used to sit on one of the rugs with her hands clasped about her knees, and with her head resting on Mrs. Hornby's broad shoulder, looking down into the embers of the fire, and with the story of her life written on her girl's face as irrevocably as though old age had set its seal there. Holcombe was kind to them all now, even to Meakim, when that gentleman rode leisurely out to the camp with the mail and the latest Paris Herald, which was their one bond of union with the great outside world.

Carroll sat smoking his pipe one night, and bending forward over the fire to get its light on the pages of the latest copy of this paper. Suddenly he dropped it between his knees. "I say, Holcombe," he cried, "here's news! Winthrop Allen has absconded with three hundred thousand dollars, and no one knows where."

Holcombe was sitting on the other side of the fire, prying at the rowel of his spur with a hunting-knife. He raised his head and laughed. "Another good man gone wrong, hey?" he said.

Carroll lowered the paper slowly to his knee and stared curiously through the smoky light to where Holcombe sat intent on the rowel of his spur. It apparently absorbed his entire attention, and his last remark had been an unconsciously natural one. Carroll smiled grimly as he folded the paper across his knee. "Now are the mighty fallen, indeed," he murmured. He told Meakim of it a few minutes later, and they both marvelled. "It's just as I told him, isn't it, and he wouldn't believe me. It's the place and the people. Two weeks ago he would have raged. Why, Meakim, you know Allen—Winthrop Allen? He's one of Holcombe's own sort; older than he is, but one of his own people; belongs to the same clubs; and to the same family, I think, and yet Harry took it just as a matter of course, with no more interest, than if I'd said that Allen was going to be married."

Meakim gave a low, comfortable laugh of content. "It makes me smile," he chuckled, "every time I think of him the day he came up them stairs. He scared me half to death, he did, and then he says, just as stiff as you please, 'If you'll leave me alone, Mr. Meakim, I'll not trouble you.' And now it's 'Meakim this,' and 'Meakim that,' and 'have a drink, Meakim,' just as thick as thieves. I have to laugh whenever I think of it now. 'If you'll leave me alone, I'll not trouble you, Mr. Meakim.'"

Carroll pursed his lips and looked up at the broad expanse of purple heavens with the white stars shining through. "It's rather a pity, too, in a way," he said, slowly. "He was all the Public Opinion we had, and now that he's thrown up the part, why—"

The pig-sticking came to an end finally, and Holcombe distinguished himself by taking his first fall, and under romantic circumstances. He was in an open place, with Mrs. Carroll at the edge of the brush to his right, and Miss Terrill guarding any approach from the left. They were too far apart to speak to one another, and sat quite still and alert to any noise as the beaters closed in around them. There was a sharp rustle in the reeds, and the boar broke out of it some hundred feet ahead of Holcombe. He went after it at a gallop, headed it off, and ran it fairly on his spear point as it came toward him; but as he drew his lance clear his horse came down, falling across him, and for the instant knocking him breathless. It was all over in a moment. He raised his head to see the boar turn and charge him; he saw where his spear point had torn the lower lip from the long tusks, and that the blood was pouring down its flank. He tried to draw out his legs, but the pony lay fairly across him, kicking and struggling, and held him in a vise. So he closed his eyes and covered his head with his arms, and crouched in a heap waiting. There was the quick beat of a pony's hoofs on the hard soil, and the rush of the boar within a foot of his head, and when he looked up he saw Miss Terrill twisting her pony's head around to charge the boar again, and heard her shout, "Let me have him!" to Mrs. Carroll.

Mrs. Carroll came toward Holcombe with her spear pointed dangerously high; she stopped at his side and drew in her rein sharply. "Why don't you get up? Are you hurt?" she said. "Wait; lie still," she commanded, "or he'll tramp on you. I'll get him off." She slipped from her saddle and dragged Holcombe's pony to his feet. Holcombe stood up unsteadily, pale through his tan from the pain of the fall and the moment of fear.

"That was nasty," said Mrs. Carroll, with a quick breath. She was quite as pale as he.

Holcombe wiped the dirt from his hair and the side of his face, and looked past her to where Miss Terrill was surveying the dead boar from her saddle, while her pony reared and shied, quivering with excitement beneath her. Holcombe mounted stiffly and rode toward her. "I am very much obliged to you," he said. "If you hadn't come—"

The girl laughed shortly, and shook her head without looking at him. "Why, not at all," she interrupted, quickly. "I would have come just as fast if you hadn't been there." She turned in her saddle and looked at him frankly. "I was glad to see you go down," she said, "for it gave me the first good chance I've had. Are you hurt?"

Holcombe drew himself up stiffly, regardless of the pain in his neck and shoulder. "No, I'm all right, thank you," he answered. "At the same time," he called after her as she moved away to meet the others, "you did save me from being torn up, whether you like it or not."

Mrs. Carroll was looking after the girl with observant, comprehending eyes. She turned to Holcombe with a smile. "There are a few things you have still to learn, Mr. Holcombe," she said, bowing in her saddle mockingly, and dropping the point of her spear to him as an adversary does in salute. "And perhaps," she added, "it is just as well that there are."

Holcombe trotted after her in some concern. "I wonder what she means?" he said. "I wonder if I were rude?"

The pig-sticking ended with a long luncheon before the ride back to town, at which everything that could be eaten or drunk was put on the table, in order, as Meakim explained, that there would be less to carry back. He met Holcombe that same evening after the cavalcade had reached Tangier as the latter came down the stairs of the Albion. Holcombe was in fresh raiment and cleanly shaven, and with the radiant air of one who had had his first comfortable bath in a week.

Meakim confronted him with a smiling countenance. "Who do you think come to-night on the mail-boat?" he asked.

"I don't know. Who?"

"Winthrop Allen, with six trunks," said Meakim, with the triumphant air of one who brings important news.

"No, really now," said Holcombe, laughing. "The old hypocrite! I wonder what he'll say when he sees me. I wish I could stay over another boat, just to remind him of the last time we met. What a fraud he is! It was at the club, and he was congratulating me on my noble efforts in the cause of justice, and all that sort of thing. He said I was a public benefactor. And at that time he must have already speculated away about half of what he had stolen of other people's money. I'd like to tease him about it."

"What trial was that?" asked Meakim.

Holcombe laughed and shook his head as he moved on down the stairs. "Don't ask embarrassing questions, Meakim," he said. "It was one you won't forget in a hurry."

"Oh!" said Meakim, with a grin. "All right. There's some mail for you in the office."

"Thank you," said Holcombe.

A few hours later Carroll was watching the roulette wheel in the gambling-hall of the Isabella when he saw Meakim come in out of the darkness, and stand staring in the doorway, blinking at the lights and mopping his face. He had been running, and was visibly excited. Carroll crossed over to him and pushed him out into the quiet of the terrace. "What is it?" he asked.

"Have you seen Holcombe?" Meakim demanded in reply.

"Not since this afternoon. Why?"

Meakim breathed heavily, and fanned himself with his hat. "Well, he's after Winthrop Allen, that's all," he panted. "And when he finds him there's going to be a muss. The boy's gone crazy. He's not safe."

"Why? What do you mean? What's Allen done to him?"

"Nothing to him, but to a friend of his. He got a letter to-night in the mail that came with Allen. It was from his sister. She wrote him all the latest news about Allen, and give him fits for robbing an old lady who's been kind to her. She wanted that Holcombe should come right back and see what could be done about it. She didn't know, of course, that Allen was coming here. The old lady kept a private school on Fifth Avenue, and Allen had charge of her savings."

"What is her name?" Carroll asked.

"Field, I think. Martha Field was—"

"The dirty blackguard!" cried Carroll. He turned sharply away and returned again to seize Meakim's arm. "Go on," he demanded. "What did she say?"

"You know her too, do you?" said Meakim, shaking his head sympathetically. "Well, that's all. She used to teach his sister. She seems to be a sort of fashionable—"

"I know," said Carroll, roughly. "She taught my sister. She teaches everybody's sister. She's the sweetest, simplest old soul that ever lived. Holcombe's dead right to be angry. She almost lived at their house when his sister was ill."

"Tut! you don't say?" commented Meakim, gravely. "Well, his sister's pretty near crazy about it. He give me the letter to read. It got me all stirred up. It was just writ in blood. She must be a fine girl, his sister. She says this Miss Martha's money was the last thing Allen took. He didn't use her stuff, to speculate with, but cashed it in just before he sailed and took it with him for spending-money. His sister says she's too proud to take help, and she's too old to work."

"How much did he take?"

"Sixty thousand. She's been saving for over forty years."

Carroll's mind took a sudden turn. "And Holcombe?" he demanded, eagerly. "What is he going to do? Nothing silly, I hope."

"Well, that's just it. That's why I come to find you," Meakim answered, uneasily. "I don't want him to qualify for no Criminal Stakes. I got no reason to love him either—But you know—" he ended, impotently.

"Yes, I understand," said Carroll. "That's what I meant. Confound the boy, why didn't he stay in his law courts! What did he say?"

"Oh, he just raged around. He said he'd tell Allen there was an extradition treaty that Allen didn't know about, and that if Allen didn't give him the sixty thousand he'd put it in force and make him go back and stand trial."

"Compounding a felony, is he?"

"No, nothing of the sort," said Meakim, indignantly. "There isn't any extradition treaty, so he wouldn't be doing anything wrong except lying a bit."

"Well, it's blackmail, anyway."

"What, blackmail a man like Allen? Huh! He's fair game, if there ever was any. But it won't work with him, that's what I'm afraid of. He's too cunning to be taken in by it, he is. He had good legal advice before he came here, or he wouldn't have come."

Carroll was pacing up and down the terrace. He stopped and spoke over his shoulder. "Does Holcombe think Allen has the money with him?" he asked.

"Yes, he's sure of it. That's what makes him so keen. He says Allen wouldn't dare bank it at Gibraltar, because if he ever went over there to draw on it he would get caught, so he must have brought it with him here. And he got here so late that Holcombe believes it's in Allen's rooms now, and he's like a dog that smells a rat, after it. Allen wasn't in when he went up to his room, and he's started out hunting for him, and if he don't find him I shouldn't be a bit surprised if he broke into the room and just took it."

"For God's sake!" cried Carroll. "He wouldn't do that?"

Meakim pulled and fingered at his heavy watch-chain and laughed doubtfully. "I don't know," he said. "He wouldn't have done it three months ago, but he's picked up a great deal since then—since he has been with us. He's asking for Captain Reese, too."

"What's he want with that blackguard?"

"I don't know; he didn't tell me."

"Come," said Carroll, quickly. "We must stop him." He ran lightly down the steps of the terrace to the beach, with Meakim waddling heavily after him. "He's got too much at stake, Meakim," he said, in half-apology, as they tramped through the sand. "He mustn't spoil it. We won't let him."

Holcombe had searched the circuit of Tangier's small extent with fruitless effort, his anger increasing momentarily and feeding on each fresh disappointment. When he had failed to find the man he sought in any place, he returned to the hotel and pushed open the door of the smoking-room as fiercely as though he meant to take those within by surprise.

"Has Mr. Allen returned?" he demanded. "Or Captain Reese?" The attendant thought not, but he would go and see. "No," Holcombe said, "I will look for myself." He sprang up the stairs to the third floor, and turned down a passage to a door at its farthest end. Here he stopped and knocked gently. "Reese," he called; "Reese!" There was no response to his summons, and he knocked again, with more impatience, and then cautiously turned the handle of the door, and, pushing it forward, stepped into the room. "Reese," he said, softly, "its Holcombe. Are you here?" The room was dark except for the light from the hall, which shone dimly past him and fell upon a gun-rack hanging on the wall opposite. Holcombe hurried toward this and ran his hands over it, and passed on quickly from that to the mantel and the tables, stumbling over chairs and riding-boots as he groped about, and tripping on the skin of some animal that lay stretched upon the floor. He felt his way, around the entire circuit of the room, and halted near the door with an exclamation of disappointment. By this time his eyes had become accustomed to the darkness, and he noted the white surface of the bed in a far corner and ran quickly toward it, groping with his hands about the posts at its head. He closed his fingers with a quick gasp of satisfaction on a leather belt that hung from it, heavy with cartridges and a revolver that swung from its holder. Holcombe pulled this out and jerked back the lever, spinning the cylinder around under the edge of his thumb. He felt the grease of each cartridge as it passed under his nail. The revolver was loaded in each chamber, and Holcombe slipped it into the pocket of his coat and crept out of the room, closing the door softly behind him. He met no one in the hall or on the stairs, and passed on quickly to a room on the second floor. There was a light in this room which showed through the transom and under the crack at the floor, and there was a sound of some one moving about within. Holcombe knocked gently and waited.

The movement on the other side of the door ceased, and after a pause a voice asked who was there. Holcombe hesitated a second before answering, and then said, "It is a servant, sir, with a note for Mr. Allen."

At the sound of some one moving toward the door from within, Holcombe threw his shoulder against the panel and pressed forward. There was the click of the key turning in the lock and of the withdrawal of a bolt, and the door was partly opened. Holcombe pushed it back with his shoulder, and, stepping quickly inside, closed it again behind him.

The man within, into whose presence he had forced himself, confronted him with a look of some alarm, which increased in surprise as he recognized his visitor. "Why, Holcombe!" he exclaimed. He looked past him as though expecting some one else to follow. "I thought it was a servant," he said.

Holcombe made no answer, but surveyed the other closely, and with a smile of content. The man before him was of erect carriage, with white hair and whiskers, cut after an English fashion which left the mouth and chin clean shaven. He was of severe and dignified appearance, and though standing as he was in dishabille still gave in his bearing the look of an elderly gentleman who had lived a self-respecting, well-cared-for, and well-ordered life. The room about him was littered with the contents of opened trunks and uncorded boxes. He had been interrupted in the task of unpacking and arranging these possessions, but he stepped unresentfully toward the bed where his coat lay, and pulled it on, feeling at the open collar of his shirt, and giving a glance of apology toward the disorder of the apartment.

"The night was so warm," he said, in explanation. "I have been trying to get things to rights. I—" He was speaking in some obvious embarrassment, and looked uncertainly toward the intruder for help. But Holcombe made no explanation, and gave him no greeting. "I heard in the hotel that you were here," the other continued, still striving to cover up the difficulty of the situation, "and I am sorry to hear that you are going so soon." He stopped, and as Holcombe still continued smiling, drew himself up stiffly. The look on his face hardened into one of offended dignity.

"Really, Mr. Holcombe," he said, sharply, and with strong annoyance in his tone, "if you have forced yourself into this room for no other purpose than to stand there and laugh, I must ask you to leave it. You may not be conscious of it, but your manner is offensive." He turned impatiently to the table, and began rearranging the papers upon it. Holcombe shifted the weight of his body as it rested against the door from one shoulder-blade to the other and closed his hands over the door-knob behind him.

"I had a letter to-night from home about you, Allen," he began, comfortably. "The person who wrote it was anxious that I should return to New York, and set things working in the District Attorney's office in order to bring you back. It isn't you they want so much as—"

"How dare you?" cried the embezzler, sternly, in the voice with which one might interrupt another in words of shocking blasphemy.

"How dare I what?" asked Holcombe.

"How dare you refer to my misfortune? You of all others—" He stopped, and looked at his visitor with flashing eyes. "I thought you a gentleman," he said, reproachfully; "I thought you a man of the world, a man who in spite of your office, official position, or, rather, on account of it, could feel and understand the—a—terrible position in which I am placed, and that you would show consideration. Instead of which," he cried, his voice rising in indignation, "you have come apparently to mock at me. If the instinct of a gentleman does not teach you to be silent, I shall have to force you to respect my feelings. You can leave the room, sir. Now, at once." He pointed with his arm at the door against which Holcombe was leaning, the fingers of his outstretched hand trembling visibly.

"Nonsense. Your misfortune! What rot!" Holcombe growled resentfully. His eyes wandered around the room as though looking for some one who might enjoy the situation with him, and then returned to Allen's face. "You mustn't talk like that to me," he said, in serious remonstrance. "A man who has robbed people who trusted him for three years, as you have done, can't afford to talk of his misfortune. You were too long about it, Allen. You had too many chances to put it back. You've no feelings to be hurt. Besides, if you have, I'm in a hurry, and I've not the time to consider them. Now, what I want of you is—"

"Mr. Holcombe," interrupted the other, earnestly.

"Sir," replied the visitor.

"Mr. Holcombe," began Allen, slowly, and with impressive gravity, "I do not want any words with you about this, or with any one else. I am here owing to a combination of circumstances which have led me through hopeless, endless trouble. What I have gone through with nobody knows. That is something no one but I can ever understand. But that is now at an end. I have taken refuge in flight and safety, where another might have remained and compromised and suffered; but I am a weaker brother, and—as for punishment, my own conscience, which has punished me so terribly in the past, will continue to do so in the future. I am greatly to be pitied, Mr. Holcombe, greatly to be pitied. And no one knows that better than yourself. You know the value of the position I held in New York City, and how well I was suited to it, and it to me. And now I am robbed of it all. I am an exile in this wilderness. Surely, Mr. Holcombe, this is not the place nor the time when you should insult me by recalling the—"

"You contemptible hypocrite," said Holcombe, slowly. "What an ass you must think I am! Now, listen to me."

"No, you listen to me," thundered the other. He stepped menacingly forward, his chest heaving under his open shirt, and his fingers opening and closing at his side. "Leave the room, I tell you," he cried, "or I shall call the servants and make you!" He paused with a short, mocking laugh. "Who do you think I am?" he asked; "a child that you can insult and gibe at? I'm not a prisoner in the box for you to browbeat and bully, Mr. District Attorney. You seem to forget that I am out of your jurisdiction now."

He waited, and his manner seemed to invite Holcombe to make some angry answer to his tone, but the young man remained grimly silent.

"You are a very important young person at home, Harry," Allen went on, mockingly. "But New York State laws do not reach as far as Africa."

"Quite right; that's it exactly," said Holcombe, with cheerful alacrity. "I'm glad you have grasped the situation so soon. That makes it easier for me. Now, what I have been trying to tell you is this. I received a letter about you to-night. It seems that before leaving New York you converted bonds and mortgages belonging to Miss Martha Field, which she had intrusted to you, into ready money. And that you took this money with you. Now, as this is the first place you have stopped since leaving New York, except Gibraltar, where you could not have banked it, you must have it with you now, here in this town, in this hotel, possibly in this room. What else you have belonging to other poor devils and corporations does not concern me. It's yours as far as I mean to do anything about it. But this sixty thousand dollars which belongs to Miss Field, who is the best, purest, and kindest woman I have ever known, and who has given away more money than you ever stole, is going back with me to-morrow to New York." Holcombe leaned forward as he spoke, and rapped with his knuckles on the table. Allen confronted him in amazement, in which there was not so much surprise at what the other threatened to do as at the fact that it was he who had proposed doing it.

"I don't understand," he said, slowly, with the air of a bewildered child.

"It's plain enough," replied the other, impatiently. "I tell you I want sixty thousand dollars of the money you have with you. You can understand that, can't you?"

"But how?" expostulated Allen. "You don't mean to rob me, do you, Harry?" he asked with a laugh.

"You're a very stupid person for so clever a one," Holcombe said, impatiently. "You must give me sixty thousand dollars—and if you don't, I'll take it. Come, now, where is it—in that box?" He pointed with his finger toward a square travelling-case covered with black leather that stood open on the table filled with papers and blue envelopes.

"Take it!" exclaimed Allen. "You, Henry Holcombe? Is it you who are speaking? Do I hear you?" He looked at Holcombe with eyes full of genuine wonder and a touch of fear. As he spoke his hand reached out mechanically and drew the leather-bound box toward him.

"Ah, it is in that box, then," said Holcombe, in a quiet, grave tone. "Now count it out, and be quick."

"Are you drunk?" cried the other, fiercely. "Do you propose to turn highwayman and thief? What do you mean?" Holcombe reached quickly across the table toward the box, but the other drew it back, snapping the lid down, and hugging it close against his breast. "If you move, Holcombe," he cried, in a voice of terror and warning, "I'll call the people of the house and—and expose you."

"Expose me, you idiot," returned Holcombe, fiercely. "How dare you talk to me like that!"

Allen dragged the table more evenly between them, as a general works on his defenses even while he parleys with the enemy. "It's you who are the idiot!" he cried. "Suppose you could overcome me, which would be harder than you think, what are you going to do with the money? Do you suppose I'd let you leave this country with it? Do you imagine for a moment that I would give it up without raising my hand? I'd have you dragged to prison from your bed this very night, or I'd have you seized as you set your foot upon the wharf. I would appeal to our Consul-General. As far as he knows, I am as worthy of protection as you are yourself, and, failing him, I'd appeal to the law of the land." He stopped for want of breath, and then began again with the air of one who finds encouragement in the sound of his own voice. "They may not understand extradition here, Holcombe," he said, "but a thief is a thief all the world over. What you may be in New York isn't going to help you here; neither is your father's name. To these people you would be only a hotel thief who forces his way into other men's rooms at night and—"

"You poor thing," interrupted Holcombe. "Do you know where you are?" he demanded. "You talk, Allen, as though we were within sound of the cable-cars on Broadway. This hotel is not the Brunswick, and this Consul-General you speak of is another blackguard who knows that a word from me at Washington, on my return, or a letter from here would lose him his place and his liberty. He's as much of a rascal as any of them, and he knows that I know it and that I may use that knowledge. He won't help you. And as for the law of the land"—Holcombe's voice rose and broke in a mocking laugh—"there is no law of the land. That's why you're here! You are in a place populated by exiles and outlaws like yourself, who have preyed upon society until society has turned and frightened each of them off like a dog with his tail between his legs. Don't give yourself confidence, Allen. That's all you are, that's all we are—two dogs fighting for a stolen bone. The man who rules you here is an ignorant negro, debauched and vicious and a fanatic. He is shut off from every one, even to the approach of a British ambassador. And what do you suppose he cares for a dog of a Christian like you, who has been robbed in a hotel by another Christian? And these others. Do you suppose they care? Call out—cry for help, and tell them that you have half a million dollars in this room, and they will fall on you and strip you of every cent of it, and leave you to walk the beach for work. Now, what are you going to do? Will you give me the money I want to take back where it belongs, or will you call for help and lose it all?"

The two men confronted each other across the narrow length of the table. The blood had run to Holcombe's face, but the face of the other was drawn and pale with fear.

"You can't frighten me," he gasped, rallying his courage with an effort of the will. "You are talking nonsense. This is a respectable hotel; it isn't a den of thieves. You are trying to frighten me out of the money with your lies and your lawyer's tricks, but you will find that I am not so easily fooled. You are dealing with a man, Holcombe, who suffered to get what he has, and who doesn't mean to let it go without a fight for it. Come near me, I warn you, and I shall call for help."