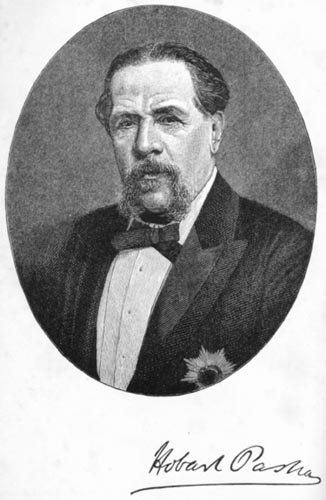

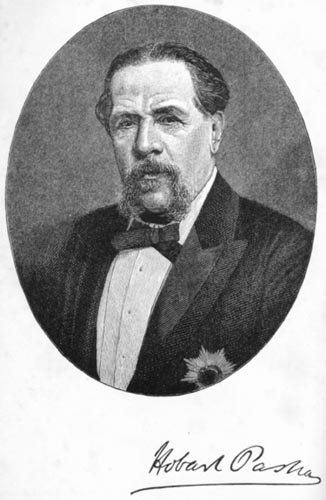

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Sketches From My Life, by Hobart Pasha

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net

Title: Sketches From My Life

By The Late Admiral Hobart Pasha

Author: Hobart Pasha

Release Date: July 15, 2005 [EBook #16296]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK SKETCHES FROM MY LIFE ***

Produced by Steven Gibbs, Janet Blenkinship and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

LONDON LONGMANS, GREEN, AND CO. 1887

All rights reserved

PRINTED BY

SPOTTISWOODE AND CO., NEW-STREET SQUARE

LONDON

These pages were the last ever written by the brave and true-hearted sailor of whose life they are a simple record.

A few months before his death, some of his friends made the fortunate suggestion that he should put on paper a detailed account of his sporting adventures, and this idea gradually developed itself until the work took the present form of an autobiography, written roughly, it is true, and put together without much method, part of it being dictated at the Riviera during the last days of the author's fatal illness. Such as it is, however, we are convinced that the many devoted friends of Hobart Pasha who now lament his death will be glad to recall in these 'Sketches' the adventures and sports which some of them shared with him, and the genial disposition and manly qualities which endeared him to them all.

To attempt to write and publish sketches of my somewhat eventful career is an act that, I fear, entails the risk of making enemies of some with whom I have come in contact. But I have arrived at that time of life when, while respecting, as I do, public opinion, I have hardened somewhat into indifference of censure. I will, however, endeavour to write as far as lies in my power (while recording facts) 'in charity with all men.' This can be done in most part by omitting the names of ships in which and officers under whom I have served.

I was born, as the novelists say, of respectable parents, at Walton-on-the-Wold, in Leicestershire, on April 1, 1822. I will pass over my early youth, which was, as might be expected, from the time of my birth until I was ten years of age, without any event that could prove interesting to those who are kind enough to peruse these pages.

At the age of ten I was sent to a well-known school at Cheam, in Surrey, the master of which, Dr. Mayo, has turned out some very distinguished pupils, of whom I was not fated to be one; for, after a year or so of futile attempt on my part to learn something, and give promise that I might aspire to the woolsack or the premiership, I was pronounced hopeless; and having declared myself anxious to emulate the deeds of Nelson, and other celebrated sailors, it was decided that I should enter the navy, and steps were taken to send me at once to sea.

A young cousin of mine who had been advanced to the rank of captain, more through the influence of his high connections than from any merit of his own, condescended to give me a nomination in a ship which he had just commissioned, and thus I was launched like a young bear, 'having all his sorrows to come,' into Her Majesty's navy as a naval cadet. I shall never forget the pride with which I donned my first uniform, little thinking what I should have to go through. My only consolation while recounting facts that will make many parents shudder at the thought of what their children (for they are little more when they join the service) were liable to suffer, is, that things are now totally altered, and that under the present régime every officer, whatever his rank, is treated like a gentleman, or he, or his friends, can know 'the reason why.'

I am writing of a period some fifteen or twenty years after Marryat had astonished the world by his thrilling descriptions of a naval officer's life and its accompanying troubles. At the time of which I write people flattered themselves that the sufferings which 'Midshipman Easy' and 'The Naval Officer' underwent while serving the Crown were tales of the past. I will show by what I am about very briefly to relate that such was very far from being the case.

Everything being prepared, and good-bye being said to my friends, who seemed rather glad to be rid of me, I was allowed to travel from London on the box of a carriage which contained the great man who had given me the nomination (captains of men-of-war were very great men in those days), and after a long weary journey we arrived at the port where H.M.S.—— was lying ready for sea. On the same night of our arrival the sailing orders came from the Admiralty; we were to go to sea the next day, our destination being South America.

Being a very insignificant individual, I was put into a waterman's boat with my chest and bed, and was sent on board. On reporting myself, I was told by the commanding officer not to bother him, but to go to my mess, where I should be taken care of. On descending a ladder to the lower deck, I looked about for the mess, or midshipmen's berth, as it was then called. In one corner of this deck was a dirty little hole about ten feet long and six feet wide, five feet high. It was lighted by two or three dips, otherwise tallow candles, of the commonest description—behold the mess!

In this were seated six or seven officers and gentlemen, some twenty-five to thirty years of age, called mates, meaning what are now called sub-lieutenants. They were drinking rum and water and eating mouldy biscuits; all were in their shirtsleeves, and really, considering the circumstances, seemed to be enjoying themselves exceedingly.

On my appearance it was evident that I was looked upon as an interloper, for whom, small as I was, room must be found. I was received with a chorus of exclamations, such as, 'What the deuce does the little fellow want here?' 'Surely there are enough of us crammed into this beastly little hole!' 'Oh, I suppose he is some protégé of the captain's,' &c. &c.

At last one, more kindly disposed than the rest, addressed me: 'Sorry there is no more room in here, youngster;' and calling a dirty-looking fellow, also in his shirtsleeves, said, 'Steward, give this young gentleman some tea and bread and butter, and get him a hammock to sleep in.' So I had to be contented to sit on a chest outside the midshipmen's berth, eat my tea and bread and butter, and turn into a hammock for the first time in my life, which means 'turned out'—the usual procedure being to tumble out several times before getting accustomed to this, to me, novel bedstead. However, once accustomed to the thing, it is easy enough, and many indeed have been the comfortable nights I have slept in a hammock, such a sleep as many an occupant of a luxurious four-poster might envy. At early dawn a noise all around me disturbed my slumbers: this was caused by all hands—officers and men—being called up to receive the captain, who was coming alongside to assume his command by reading his official appointment.

I shall never forget his first words. He was a handsome young man, with fine features, darkened, however, by a deep scowl. As he stepped over the side he greeted us by saying to the first lieutenant in a loud voice, 'Put all my boat's crew in irons for neglect of duty.' It seems that one of them kept him waiting for a couple of minutes when he came down to embark. After giving this order our captain honoured the officers who received him with a haughty bow, read aloud his commission, and retired to his cabin, having ordered the anchor to be weighed in two hours.

Accordingly at eight o'clock we stood out to sea, the weather being fine and wind favourable. At eleven all hands were called to attend the punishment of the captain's boat's crew. I cannot describe the horror with which I witnessed six fine sailor-like looking fellows torn by the frightful cat, for having kept this officer waiting a few minutes on the pier. Nor will I dwell on this illegal sickening proceeding, as I do not write to create a sensation, and, thank goodness! such things cannot be done now.

I had not much time for reflection, for my turn came next. I believe I cried or got into somebody's way, or did something to vex the tyrant; all I know is that I heard myself addressed as 'You young scoundrel,' and ordered to go to the 'mast-head.' Go to the mast-head indeed! with a freshening wind, under whose influence the ship was beginning to heel over, and an increasing sea that made her jump about like an acrobat. I had not got my sea legs, and this feat seemed an utter impossibility to me. I looked with horror up aloft; then came over me the remembrance of Marryat's story of the lad who refused to go to the mast-head, and who was hoisted up by the signal halyards. While thinking of this, another 'Well, sir, why don't you obey orders?' started me into the lower rigging, which I began with the greatest difficulty to climb, expecting at every step to go headlong overboard.

A good-natured sailor, seeing the fix I was in, gave me a helping hand, and up I crawled as far as the maintop. This, I must explain to my non-nautical reader, is not the mast-head, but a comparatively comfortable half-way resting-place, from whence one can look about feeling somewhat secure.

On looking down to the deck my heart bled to see the poor sailor who had helped me undergoing punishment for his kind act. I heard myself at the same time ordered 'to go higher,' and a little higher I did go. Then I stopped, frightened to death, and almost senseless; terror, however, seemed to give me presence of mind to cling on, and there I remained till some hours afterwards; then I was called down. On reaching the deck I fainted, and knew no more till I awoke after some time in my hammock.

Now, I ask anyone, even a martinet at heart, whether such treatment of a boy, not thirteen years of age, putting his life into the greatest danger, taking this first step towards breaking his spirit, and in all probability making him, as most likely had been done to the poor men I had seen flogged that morning, into a hardened mutinous savage, was not disgraceful?

Moreover, it was as close akin to murder as it could be, for I don't know how it was I didn't fall overboard, and then nothing could have saved my life. However, as I didn't fall, I was not drowned, and the effect on me was curious enough. For all I had seen and suffered on that the opening day of my sea-life made me think for the first time—and I have never ceased thinking (half a century has passed since then)—how to oppose tyranny in every shape. Indeed, I have always done so to such an extent as to have been frequently called by my superiors 'a troublesome character,' 'a sea lawyer,' &c.

Perhaps in this way I have been able to effect something, however small, towards the entire change that has taken place in the treatment of those holding subordinate positions in the navy—and that something has had its use, for the tyrant's hand is by force stayed now, 'for once and for all.'

With this little I am satisfied.

Now let us briefly look into the question, 'Why are men tyrants when they have it in their power to be so?'

Unfortunately, as a rule, it appears to come natural to them! What caused the Indian Mutiny? Let Indian officers and those employed in the Indian civil service answer that question.

However, I have only to do with naval officers. My experience tells me that a man clothed with brief but supreme authority, such as the command of a man-of-war, in those days when for months and months he was away from all control of his superiors and out of reach of public censure, is more frequently apt to listen to the promptings of the devil, which more or less attack every man, especially when he is alone.

Away from the softening influence of society and the wholesome fear of restraint, for a time at least the voice of his better angel is silenced. Perhaps also the necessarily solitary position of a commander of a man-of-war, his long, lonely hours, the utter change from the jovial life he led previous to being afloat, to say nothing of his liver getting occasionally out of order, may all tend to make him irritable and despotic.

I have seen a captain order his steward to be flogged, almost to death, because his pea-soup was not hot. I have seen an officer from twenty to twenty-five years of age made to stand between two guns with a sentry over him for hours, because he had neglected to see and salute the tyrant who had come on deck in the dark. And as a proof, though it seems scarcely credible, of what such men can do when unchecked by fear of consequences, I will cite the following:—

On one occasion the captain of whom I have been writing invited a friend to breakfast with him, and there being, I suppose, a slight monotony in the conversation, he asked his guest whether he would like, by way of diversion, to see a man flogged. The amusement was accepted, and a man was flogged.

It was about the time I write of that the tyranny practised on board Her Majesty's ships was slowly but surely dawning upon the public, and a general outcry against injustice began.

This was shown in a very significant manner by the following fact:—

A post-captain of high rank and powerful connections dared, in contradiction to naval law, to flog a midshipman. This young officer's father, happening to be a somewhat influential man, made a stir about the affair. The honourable captain was tried by court-martial and severely reprimanded.

However, I will cut short these perhaps uninteresting details, merely stating that for three years I suffered most shameful treatment. My last interview with my amiable cousin is worth relating. The ship was paid off, and the captain, on going to the hotel at Portsmouth, sent for me and offered me a seat on his carriage to London. Full of disgust and horror at the very sight of him, I replied that I would rather 'crawl home on my hands and knees than go in his carriage,' and so ended our acquaintance, for I never saw him again.

It may be asked how, like many others, I tided over all the ill-usage and the many trials endured during three years. The fact is, I had become during that period of ill-treatment so utterly hardened to it that I seemed to feel quite indifferent and didn't care a rap. But wasn't I glad to be free!

I had learnt many a lesson of use to me in after life, the most important of all being to sympathise with other people's miseries, and to make allowance for the faults and shortcomings of humanity.

On the other hand, experience is a severe taskmaster, and it taught me to be somewhat insubordinate in my notions. I fear I must confess that this spirit of insubordination has never left me.

On my arrival at home my relations failed to see in me an ill-used lad (I was only sixteen), and seemed inclined to disbelieve my yarns; but this did not alter the facts, nor can I ever forget what I went through during that 'reign of terror,' as it might well be called.

People may wonder how was it in the days of Benbow and his successors no complaints were made. To this I answer, first, that the men of those days, knowing the utter hopelessness of complaining, preferred to 'grin and bear;' secondly, that neither officers nor men were supposed to possess such a thing as feeling, when they had once put their foot on board a man-of-war. Then there were the almost interminable sea voyages under sail, during which unspeakable tyrannies could be practised, unheard of beyond the ship, and unpunished. It must be remembered that there were no telegraphs, no newspaper correspondents, no questioning public, so that the evil side of human nature (so often shown in the very young in their cruelty to animals) had its swing, fearless of retribution.

Let us leave this painful subject, with the consoling thought that we shall never see the like again.

After enjoying a few weeks at home, I was appointed to the Naval Brigade on service in Spain, acting with the English army, who were there by way of assisting Queen Christina against Don Carlos.

The army was a curious collection of regular troops and volunteer soldiers, the latter what would be called 'Bashi-Bazouks.' The naval part of the expedition consisted of 1,200 Royal Marines, and a brigade of sailors under the orders of Lord John Hay. The army (barring the regulars, who were few in numbers) was composed of about 15,000 of the greatest rabble I ever saw, commanded by Sir De Lacy Evans.

For fear any objection or misapprehension be applied to the word 'rabble,' I must at once state that these volunteers, though in appearance so motley and undisciplined, fought splendidly, and in that respect did all honour to their country and the cause they were fighting for.

Very soon after we had disembarked I received what is usually called my 'baptism of fire,' that is to say, I witnessed 'the first shot fired in anger.' The Carlists were pressing hard on the Queen's forces, who were returning towards the sea; it was of the greatest importance to hold certain heights that defended San Sebastian and the important port of Passagis.

The gallant marines (as usual to the front) were protecting the hill on which Lord John was standing; the fire was hot and furious. I candidly admit I was in mortal fear, and when a shell dropped right in the middle of us, and was, I thought, going to burst (as it did), I fell down on my face. Lord John, who was close to me, and looking as cool as a cucumber, gave me a severe kick, saying, 'Get up, you cowardly young rascal; are you not ashamed of yourself?'

I did get up and was ashamed of myself. From that moment to this I have never been hard upon those who flinched at the first fire they were under. My pride helped me out of the difficulty, and I flinched no more. For an hour or so the battle raged furiously.

By degrees all fear left me; I felt only excitement and anger, and when we (a lot I had to do with it!) drove the enemy back in the utmost confusion, wasn't I proud!

When all was over Lord John called me, and after apologising in the most courteous manner for the kick, he gave me his hand (poor fellow! he had already lost one arm while fighting for his country), and said: 'Don't be discouraged, youngster; you are by no means the first who has shown alarm on being for the first time under fire.' So I was happy.

It is not my intention to give in detail the events that I witnessed during that disastrous civil war in Spain; suffice it that after much hard fighting the Carlists were driven back into their mountains so much discouraged that they eventually renounced a hopeless cause; and at all events for a long period order was restored in Spain.

After serving under Lord John Hay for six or seven months, I was appointed to another ship, which was ordered to my old station, South America.

The captain of my new ship was in every sense a gentleman, and although a strict disciplinarian, was just and kind-hearted. From the captain downwards every officer was the same in thought and deed, so we were all as happy as sand-boys. It was then that I began to realise a fact of which before I had only a notion—namely, that discipline can be maintained without undue severity, to say nothing of cruelty, and that service in the navy could be made a pleasure as well as a duty to one's country.

After visiting Rio de Janeiro, we were sent to the River Plate; there we remained nearly a year, during which time several adventures which I will relate occurred, both concerning my duties and my amusements.

I must tell my readers that from earliest boyhood I had a passionate love for shooting; and, through the kindness of my commanding officer while at Monte Video, I was allowed constantly to indulge in sport.

On one occasion my captain, who was a keen sportsman, took me with him out shooting. We had a famous day's sport, filled our game bags with partridges, ducks, and snipe, and were returning home on horseback when a solitary horseman, a nasty-looking fellow, armed to the teeth, rode up to us. As I knew a little Spanish we began to talk about shooting, &c. &c.; then he asked me to shoot a bird for him (the reason why he did this will be seen immediately). I didn't like the cut of his jib, so rather snubbed him. However, he continued to ride on with us, to within half a mile of where our boat was waiting to take us on board. I must explain our relative positions as we rode along. The captain was on my left, I next to him, and the man was on my right, riding very near to me. All of a sudden he exclaimed in Spanish, 'Now is the time or never,' threw his right leg over the pommel of his saddle, slipped on to the ground, drew his knife, dashed at me, and after snatching my gun from my hand, stuck his knife (as he thought) into me. Then he rushed towards the captain, pulling the trigger of my gun, and pointing straight at the latter's head; the gun was not loaded, having only the old percussion caps on. (Now I saw why he wanted me to fire, so that he might know whether my gun was loaded; but the old caps evidently deceived him.)

All this was the work of a very few seconds. Now what was my chief doing? Seeing a row going on, he was dismounting; in fact, was half-way off his horse, only one foot in the stirrup, when the man made the rush at him. Finding me stuck to my saddle (for the ruffian's knife had gone through my coat and pinned me), and the fellow snapping my gun, which was pointed at him, he as coolly as possible put his gun over his horse's shoulder and shot the would-be murderer dead on the spot. Then turning to me he said quite calmly, 'I call you to witness that that man intended to murder me.' How differently all would have ended had my gun been loaded! The villain would have shot my chief, taken both guns, and galloped off, leaving me ignominiously stuck to my saddle.

The audacity of this one man attacking us two armed sportsmen showed the immense confidence these prairie people feel in themselves, especially in their superior horsemanship. However, the fellow caught a Tartar on this occasion.

As for me, the knife had gone, as I said, through my loose shooting jacket just below the waist, through the upper part of my trousers, and so into the saddle, without even touching my skin. I have kept the knife in memory of my lucky escape.

While laying at Monte Video there was on each side of us a French man-of-war, the officers of which were very amiably inclined, and many were the dinners and parties exchanged between us.

In those days the interchange of our respective languages was very limited on both sides, so much so, that our frantic efforts to understand each other were a constant source of amusement. A French midshipman and myself, however, considered ourselves equal to the occasion, and professed linguists; so on the principle that in the 'land of the blind the one-eyed man is king,' we were the swells of the festivities.

I remember on one occasion, when the birthday of Louis Philippe was to be celebrated, my French midshipman friend came on board officially and said, 'Sir, the first of the month is the feast of the King; you must fire the gun.' 'All right,' said we. Accordingly, we loaded our guns in the morning, preparatory to saluting at noon. It was raining heavily all the forenoon, so we had not removed what is called the tompions (to my unprofessional reader I may say that the tompion is a very large piece of wood made to fit into the muzzle, for the purpose of preventing wet from penetrating). To this tompion is, or used to be, attached a large piece of wadding, what for I never rightly understood.

Now it seems that those whose duty it was to attend to it had neglected to take these things out of the guns.

On the first gun being fired from the French ship we began our salute. The French ships were close alongside of us, one on either side. The gunner who fires stands with the hand-glass to mark the time between each discharge. On this occasion he began his orders thus: 'Fire, port;' then suddenly recollecting that the tompions were not removed he added, 'Tompions are in, sir.' No one moved. The gunner could not leave his work of marking time. Again he gave the order, 'Fire, starboard,' repeating, 'Tompions are in, sir,' and so on till half the broadside had been fired before the tompions had been taken out. It is difficult to describe the consternation on board the French vessels, whose decks were crowded with strangers (French merchants, &c.), invited from the shore to do honour to their King's fête. These horrid tompions and their adjuncts went flying on to their decks, from which every one scampered in confusion. It was lucky our guns did not burst.

This was a most awkward dilemma for all of us. I was sent on board to apologise. The French captain, with the courtesy of his nation, took the mishap most good-humouredly, begging me to return the tompions to my captain, as they had no occasion for them. So no bad feeling was created, though shortly after this contretemps an affair of so serious a nature took place, that a certain coldness crept in between ourselves and our ci-devant friends.

It seems that there had been of late several desertions from the French vessels lying at Monte Video, great inducements of very high wages being offered by the revolutionary party in Buenos Ayres for men to serve them. The French commander therefore determined to search all vessels leaving Monte Video for other ports in the River Plate—a somewhat arbitrary proceeding, and one certain to lead to misunderstanding sooner or later.

On the occasion I refer to, a vessel which, though not under the English flag, had in some way or other obtained English protection, was leaving the port; so we sent an officer and a party of armed men to prevent her being interfered with. I was of the party, which was commanded by our second lieutenant. Our doing this gave great offence to the French commander, who shortly after we had gone on board also sent a party of armed men, with positive orders to search the vessel at all risks. On our part we were ordered not to allow the vessel to be searched or interfered with. The French officer, a fine young fellow, came on board with his men and repeated his orders to Lieutenant C——. The vessel, I may mention, was a schooner of perhaps a couple of hundred tons, about 130 feet long. We had taken possession of the after-part of the deck, the French crew established themselves on the fore-part.

Never was there a more awkward position. The men on both sides loaded and cocked their muskets. The English and French officers stood close to one another. The former said, 'Sir, you have no business here, this vessel is under English protection. I give you five minutes to leave or take the consequences.' The other replied, 'Sir, I am ordered to search the vessel, and search her I will.' They both seemed to, and I am sure did, mean business; for myself, I got close to my lieutenant and cocked a pistol, intending to shoot the French officer at the least show of fighting. Nevertheless, I thought it a shockingly cruel and inhuman thing to begin a cold-blooded fight under such circumstances.

However, to obey orders is the duty of every man. Lieutenant C—— looked at his watch; two minutes to spare. The marines were ordered to prepare, and I thought at the end of the two minutes the deck of the little vessel would have been steeped in blood. Just then, in the distance, there appeared a boat pulling towards us at full speed; it seems that wiser counsels had prevailed between the captains of the two ships: the French were told to withdraw and leave the vessel in our hands.

I was much amused at the cordial way in which the two lieutenants shook hands on receiving this order. There would indeed have been a fearful story to tell had it not arrived in time; for I never saw determination written so strongly on men's countenances as on those of both parties, so nearly engaged in what must have proved a most bloody fight.

After this incident cordial relations were never re-established between ourselves and our French friends; fortunately, shortly afterwards we sailed for Buenos Ayres.

Buenos Ayres, that paradise of pretty women, good cheer, and all that is nice to the sailor who is always ready for a lark! We at once went in for enjoying ourselves to our heart's content; we began, every one of us, by falling deeply in love before we had been there forty-eight hours—I say every one, because such is a fact.

My respectable captain, who had been for many years living as a confirmed bachelor with his only relative, an old spinster sister, with whom he chummed, and I fancy had hardly been known to speak to another woman, was suddenly perceived walking about the street with a large bouquet in his hand, his hair well oiled, his coat (generally so loose and comfortable-looking) buttoned tight to show off his figure; and then he took to sporting beautiful kid gloves, and even to dancing. He could not be persuaded to go on board at any cost, while he had never left his ship before, except for an occasional day's shooting. In short, he had fallen hopelessly in love with a buxom Spanish lady with lustrous eyes as black as her hair, the widow of a murdered governor of the town.

Our first and second lieutenants followed suit; both were furiously in love; and, as I said, every one, even a married man, one of my messmates, fell down and worshipped the lovely (and lovely they were, and no mistake) Spanish girls of Buenos Ayres, whose type of beauty is that which only the blue blood of Spain can boast of. Now, reader, don't be shocked, I fell in love myself, and my love affair proved of a more serious nature, at least in its results, than that of the others, because, while the daughter (she was sixteen, and I seventeen) responded to my affection, her mother, a handsome woman of forty, chose to fall in love with me herself.

This was rather a disagreeable predicament, for I didn't, of course, return the mother's affection a bit, while I was certainly dreadfully spoony on the daughter.

To make a long story short, the girl and I, like two fools as we were, decided to run away together, and run away we did. I should have been married if the mother hadn't run after us. She didn't object to our being married, but, in the meantime, she remained with us, and she managed to make the country home we had escaped to, with the intention of settling down there, so unbearable, that, luckily for me as regards my future, I contrived to get away, and went as fast as I could on board my ship for refuge, never landing again during our stay at Buenos Ayres.

Fortunately, shortly afterwards we were ordered away, and so ended my first love affair.

I shall never forget the melancholy, woebegone faces of my captain and brother officers on our re-assembling on board. It was really most ludicrous. However, a sea voyage which included several sharp gales of wind soon erased all sad memories; things gradually 'brightened,' and ere many weeks had passed all on board H.M.S.—— resumed their usual appearance.

Whilst I was at Buenos Ayres I had the good luck to visit the independent province of Paraguay, which my readers must have heard spoken of, sometimes with admiration, sometimes with sneers, as the hot-bed of Jesuitism. Those who sneer say that the Jesuit fathers who left Spain under Martin Garcia formed this colony in the River Plate entirely in accordance with the principles their egotism and love of power dictated. It may be so; it is possible that the Jesuits were wrong in the conclusions they came to as regards the governing or guiding of human nature; all I can say is, that the perfect order reigning throughout the colony they had formed, the respect for the clergy, the cheerful obedience to laws, the industry and peaceful happiness one saw at every step, made an impression on me I have never forgotten; and when I compare it with the discord, the crime, and the hatred of all authority which is now prevailing, alas! in most civilised countries, I look back to what I saw in Paraguay with a sigh of regret that such things are of the past. It was beautiful to see the respect paid to the Church (the acknowledged ruler of the place), the cleanliness and comfort of the farms and villages, the good-will and order that prevailed amongst the natives. It was most interesting to visit the schools, where only so much learning was introduced as was considered necessary for the minds of the industrious population, without rendering them troublesome to the colony or to themselves. Though the inhabitants were mostly of the fiery and ungovernable Spanish race, who had mixed with the wild aborigines, it is remarkable that they remained quiet and submissive.

To prevent pernicious influences reaching this 'happy valley,' the strictest regulations were maintained as regards strangers visiting the colony.

The River Plate, which, coming down from the Andes through hundreds of miles of rich country, flows through Paraguay, was unavailable to commerce owing to this law of exclusiveness, which prevented even the water which washed the shores being utilised. However, about the time I speak of the English government had determined, in the general interests of trade, to oppose this monopoly, and to open a way of communication up the river by force if necessary. The Paraguayans refused to accept the propositions made by the English, and prepared to fight for their so-called rights. They threw a formidable barrier across the stream, and made a most gallant resistance. It was on this occasion that Captain (now Admiral) H—— performed the courageous action which covered him with renown for the rest of his life. The enemy had, amongst other defences, placed a heavy iron chain across the river. This chain it was absolutely necessary to remove, and the gallant officer I refer to, who commanded the attack squadron, set a splendid example to us all by dashing forward and cutting with a cold chisel the links of this chain. The whole time he was thus at work he was exposed to a tremendous fire, having two men killed and two wounded out of the six he took with him. This deed, now almost forgotten by the public, can never be effaced from the memory of those who saw it done. That the fight was a severe one is evident from the fact that the vessel I belonged to had 107 shots in her hull, and thirty-five out of seventy men killed and wounded.

It was after we had thus forced ourselves into intercourse with the Paraguayans that I saw an instance of want of tact which struck me as most remarkable. Fighting being over, diplomacy stepped in, and a man of somewhat high rank in that service was sent to make friendly overtures to the authorities. Can it be believed (I do not say it as a sneer against diplomacy, for this blunder was really unique), this big man had scarcely finished the pipe of peace which he smoked with the authorities, when he proposed to introduce vaccination and tracts among the people? Badly as the poor fellows felt the licking they had received, and much as they feared another should they give trouble to the invaders, they so resented our representative's meddling that he found it better to beat a hasty retreat, and to send a wiser man in his stead. But their fate was sealed, and from the moment the stranger put his foot into this interesting country dates its entire change. The system that the Jesuits established was quickly done away with. Paraguay is now a part of the Argentine Republic, it is generally at war with some of its neighbours, and its inhabitants are poor, disorderly, and wretched.

As I shall have, while telling the story of my life, to relate more serious events, I will, after recounting one more yarn, not weary my readers with the little uninteresting details of my youthful adventures, but pass over the next three years or so, at which time, after having returned to England, I was appointed to another ship going to South America, for the purpose of putting down the slave trade in the Brazils. The adventure to which I have referred was one that made a deep impression on my mind, as being of a most tragic nature.

While at Rio de Janeiro we were in the habit of visiting among the people, attending dances, &c. I always remarked that the pretty young Brazilian girls liked dancing with the fresh young English sailors better than with their mud-coloured companions of the male sex, the inhabitants of the country.

At the time I write of the English were not liked by the Brazilians, partly on account of the raid we were then making on the slave trade, partly through the usual jealousy always felt by the ignorant towards the enlightened. So with the men we were seldom or ever on good terms, but with the girls somehow sailors always contrive to be friends.

It was at one of the dances I have spoken of that the scene I am about to describe took place.

Among the pretty girls who attended the ball was one prettier perhaps than any of her companions; indeed, she was called the belle of Rio Janeiro. I will not attempt to portray her, but I must own she was far too bewitching for the peace of heart of her many admirers, and unhappily she was an unmitigated flirt in every sense of the word.

Now there was a young Brazilian nobleman who had, as he thought, been making very successful progress towards winning this girl's heart—if she had a heart. All was progressing smoothly enough till these hapless English sailors arrived.

Then, perhaps with the object of making her lover jealous (a very common though dangerous game), Mademoiselle pretended (for I presume it was pretence) to be immensely smitten with one of them—a handsome young midshipman whom we will call A.

At the ball where the incident I refer to occurred, she danced once with him, twice with him, and was about to start with him a third time, when, to the astonishment of the lookers-on, of whom I formed part, the young Brazilian rushed into the middle of the room where the couple were standing, walked close up to them and spat in A.'s face.

Before the aggressor could look round him, he found himself sprawling on the floor, knocked by the angry Briton into what is commonly called 'a cocked hat.' Not a word was spoken. A. wiped his face, led his partner to a seat and came straight to me, putting his arm in mine and leading me into the verandah. The Brazilian picked himself up and came also into the verandah; in less time than I can write it a hostile meeting was settled, pistols were procured, and we (I say we, because I had undertaken to act as A.'s friend, and the Brazilian had also engaged a friend) sauntered into the garden as if for a stroll.

It was a most lovely moonlight night, such a night as can only be seen in the tropics.

I should mention that the chief actors in the coming conflict had neither of them seen twenty years, and we their seconds were considerably under that age. The aggressor, whose jealous fury had driven him almost to madness when he committed an outrageous affront on a stranger, was a tall, handsome, dark-complexioned young fellow. A. was also very good-looking, with a baby complexion, blue eyes and light curly hair, a very type of the Saxon race.

They both looked determined and calm. After proceeding a short distance we found a convenient spot in a lovely glade. It was almost as clear as day, so bright was the moonlight. The distance was measured (fourteen paces), the pistols carefully loaded. Before handing them to the principals we made an effort at arrangement, an effort too contemptuously received to be insisted upon, and we saw that any attempt at reconciliation would be of no avail without the exchange of shots; so, handing to each his weapon, we retired a short distance to give the signal for firing, which was to be done by my dropping a pocket-handkerchief. It was an anxious moment even for us, who were only lookers-on. I gave the words, one, two, three, and dropped the handkerchief.

The pistols went off simultaneously. To my horror I saw the young Brazilian spin round and drop to the ground, his face downwards; we rushed up to him and found that the bullet from A.'s pistol had gone through his brain. He was stone dead.

Then the solemnity of the whole affair dawned on us, but there was no time for thought. Something must be done at once, for revenge quick and fearful was sure to follow such a deed like lightning.

We determined to hurry A. off to his ship, and I begged the young Brazilian to go into the house and break the sad news. The poor fellow, though fearfully cut up, behaved like a gentleman, walking slowly away so as to give us time to escape. As we passed the scene of gaiety the sounds of music and dancing were going on, just as when we left it. How little the jovial throng dreamt of the tragedy that had just been enacted within a few yards of them; of the young life cut down on its threshold!

We got on board all right, but such a terrible row was made about the affair that the ship to which A. belonged had to go to sea the next day, and did not appear again at Rio de Janeiro.

I, though not belonging to that vessel, was not allowed to land for many months.

One word about Rio de Janeiro. Rio, as it is generally called, is perhaps one of the most lovely spots in the world. The beautiful natural bay and harbour are unequalled throughout the whole universe. Still, like the Bosphorus, the finest effect is made by Rio de Janeiro when looked at from the water. In the days of which I write yellow fever was unknown; now that fearful disease kills its thousands, aye, tens of thousands, yearly. The climate, though hot at times, is very good; in the summer the mornings are hot to a frying heat, but the sea breeze comes in regularly as clockwork, and when it blows everything is cool and nice. Life is indeed a lazy existence; there is no outdoor amusement of any kind to be had in the neighbourhood. As to shooting, there are only a few snipe to be found here and there, and while looking for these you must beware of snakes and other venomous reptiles, which abound both in the country and in town. I remember a terrible fright a large picnic party, at which I assisted, was thrown into while lunching in the garden of a villa, almost in the town of Rio, by a lady jumping up from her seat with a deadly whip-snake hanging on her dress. I once myself sat on an adder who put his fangs through the woollen stuff of my inexpressibles and could not escape. The same thing happened with the lady's dress; in that case also we caught the snake, as it could not disentangle its fangs.

In the country near Rio there are great snakes called the anaconda, a sort of boa-constrictor on a large scale. Once, while walking in the woods with some friends, we found a little Indian boy dead on the ground, one of these big snakes lying within a foot or so of him, also dead; the snake had a poisoned arrow in his brain, which evidently had been shot at him by the poor little boy, whose blow-pipe was lying by his side. The snake must have struck the boy before it died, as we found a wound on the boy's neck. This reptile measured twenty-two feet in length.

By the way, a well-known author, Mrs. B——, tells a marvellous story about these snakes. She says that they always go in pairs, have great affection for each other, and are prepared on all occasions to resent affronts offered to either of them. She narrates that a peasant once killed a big anaconda, and that the other, or chum snake, followed the man several miles to the house where he had taken the dead one, got in by the window, and crushed the destroyer of his friend to death. I expect that some salt is necessary to swallow this tale, but such is the statement Mrs. B—— makes.

The most lovely birds and butterflies are found near Rio, and the finest collections in the world are made there. The white people are Portuguese by origin—not a nice lot to my fancy, though the ladies are as usual always nice, especially when young; they get old very soon through eating sweets and not taking exercise. There is very little poverty except among the free blacks, who are lazy and idle and somewhat vicious. I always have believed that the black man is an inferior animal—in fact, that the dark races are meant to be drawers of water and hewers of wood. I do not deny that they have souls to be saved, but I believe that their rôle in this world is to attend on the white man. The black is, and for years has been, educated on perfect equality with the white man, and has had every chance of improving himself—with what result? You could almost count on your fingers the names of those who have distinguished themselves in the battle of life.

Sometimes, while cruising off the coast of Rio de Janeiro looking out for slave vessels, we passed a very monotonous life. The long and fearfully hot mornings before the sea breeze sets in, the still longer and choking nights with the thermometer at 108°, were trying in the extreme to those accustomed to the fresh air of northern climates; but sailors have always something of the 'Mark Tapley' about them and are generally jolly under all circumstances, and so it was with me. One day, while longing for something to do, I discovered that the crew had been ordered to paint the ship outside; as a pastime I put on old clothes and joined the painting party. Planks were hung round the ship by ropes being tied to each end of the plank; on these the men stood to do their work. We had not been employed there very long when there was a cry from the deck that the ship was surrounded by sharks. It seems that the butcher had killed a sheep, whose entrails, having been thrown overboard, attracted these fearful brutes round the ship in great numbers. As may be imagined, this report created a real panic among the painters, for I believe we all feared a shark more than an enemy armed to the teeth. I at once made a hurried movement to get off my plank. As I did so the rope at one end slipped off, and so threw the piece of wood, to which I had to hang as on a rope, up and down the vessel's side, bringing my feet to within a very few inches of the water. On looking downwards I saw a great shark in the water, almost within snapping distance of my legs. I can swear that my hair stood on end with fear; though I held on like grim death, I felt myself going, yes, going, little by little right into the beast's jaws. At that moment, only just in time, a rope was thrown over my head from the deck above me, and I was pulled from my fearfully perilous position, more dead than alive. Now for revenge on the brutes who would have eaten me if they could! It was a dead calm, the sharks were still swimming round the ship waiting for their prey. We got a lot of hooks with chains attached to them, on which we put baits of raw meat. I may as well mention a fact not generally known, viz., that a shark must turn on his back before opening his capacious mouth sufficiently to feed himself; when he turns he means business, and woe to him who is within reach of the man-eater's jaws. On this occasion what we offered them was merely a piece of meat, and most ravenously did they rush, turn on their backs, and swallow it, only to find that they were securely hooked, and could not bite through the chains that were fast to the hooks—in fact, that it was all up with them. Orders had been given by the commanding officer that the sharks were not to be pulled on board, partly from the dangerous action of their tails and jaws even when half dead, partly on account of the confusion they make while floundering about the decks; so we hauled them close to the top of the water, fired a bullet into their brains and cut them loose. We killed thirty that morning in this way, some of them eight to ten feet long.

The most horrid thing I know is to see, as I have done on more than one occasion, a man taken by a shark. You hear a fearful scream as the poor wretch is dragged down, and nothing remains to tell the dreadful tale excepting that the water is deeply tinged with blood on the spot where the unfortunate man disappeared. These ravenous man-eaters scent blood from an enormous distance, and their prominent upper fin, which is generally out of the water as they go along at a tremendous pace, may be seen at a great distance, and they can swim at the rate of a mile a minute. A shark somewhat reminds me of the torpedo of the present day, and in my humble opinion is much more dangerous.

Once we caught a large shark. On opening him we found in his inside a watch and chain quite perfect. Could it have been that some poor wretch had been swallowed and digested, and the watch only remained as being indigestible?

It is strange to see the contempt with which the black man treats a shark, the more especially when he has to do with him in shallow water. A negro takes a large knife and diving under the shark cuts its bowels open. If the water is deep the shark can go lower down than the man and so save himself, and if the nigger don't take care he will eat him; thus the black man never goes into deep water if he can help it, for he is always expecting a shark.

Shortly after the duel at Rio I went to England, but to be again immediately appointed to a vessel on the Brazilian station.

It was at the time when philanthropists of Europe were crying aloud for the abolition of the African slave trade, never taking for a moment into consideration the fact that the state of the savage African black population was infinitely bettered by their being conveyed out of the misery and barbarism of their own country, introduced to civilization, given opportunities of embracing religion, and taught that to kill and eat each other was not to be considered as the principal pastime among human beings.

At the period I allude to (from 1841 to 1845) the slave trade was carried out on a large scale between the coast of Africa and South America; and a most lucrative trade it was, if the poor devils of negroes could be safely conveyed alive from one coast to the other. I say if, because the risk of capture was so great that the poor wretches, men, women, and children, were packed like herrings in the holds of the fast little sailing vessels employed, and to such a fearful extent was this packing carried on that, even if the vessels were not captured, more than half the number of blacks embarked died from suffocation or disease before arriving at their destination, yet that half was sufficient to pay handsomely those engaged in the trade.

On this point I propose giving examples and proofs hereafter, merely remarking, en passant, that had the negroes been brought over in vessels that were not liable to be chased and captured, the owners of such vessels would naturally, considering the great value of their cargo, have taken precautions against overcrowding and disease. Now, let us inquire as to the origin of these poor wretched Africans becoming slaves, and of their being sold to the white man. It was, briefly speaking, in this wise. On a war taking place between two tribes in Africa, a thing of daily occurrence, naturally many prisoners were made on both sides. Of these prisoners those who were not tender enough to be made into ragoût were taken down to the sea-coast and sold to the slave-dealers, who had wooden barracks established ready for their reception.

Into these barracks, men, women, and children, most of whom were kept in irons to prevent escape, were bundled like cattle, there to await embarkation on board the vessels that would convey them across the sea.

Now, as the coast was closely watched on the African side, to prevent the embarkation of slaves, as it was on the Brazilian side, to prevent their being landed, the poor wretches were frequently waiting for weeks on the seashore undergoing every species of torment.

At last the vessel to carry off a portion of them arrived, when they were rushed on board and thrown into the hold regardless of sex, like bags of sand, and the slaver started on her voyage for the Brazils. Perhaps while on her way she was chased by an English cruiser, in which case, so it has often been known to happen, a part of the living cargo would be thrown overboard, trusting that the horror of leaving human beings to be drowned would compel the officers of the English cruiser to slacken their speed while picking the poor wretches up, and thus give the slaver a better chance of escape. (This I have seen done myself, fortunately unavailingly.)

I will now ask the reader to bring his thoughts back to the coast of Brazil, where a good look-out was being kept for such vessels as I have mentioned as leaving the African coast with live cargo on board bound for the Brazilian waters. Rio de Janeiro, the capital of Brazil, was the headquarters of the principal slave-owners. It was there that all arrangements were made regarding the traffic in slaves, the despatch of the vessels in which they were to be conveyed, the points on which they were to land, &c., and it was at Rio that the slave-vessels made their rendezvous before and after their voyages. It was there also that the spies on whose information we acted were to be found, and double-faced scoundrels they were, often giving information which caused the capture of a small vessel with few slaves on board, while the larger vessel, with twice the number, was landing her cargo unmolested.

As for myself, I was at the time of life when enterprise was necessary for my existence, and so keenly did I join in the slave-hunting mania that I found it dangerous to land in the town of Rio for fear of assassination.

My captain, seeing how enthusiastic I was in the cause, which promised prize-money if not renown, encouraged me by placing me in a position that, as a humble midshipman, I was scarcely entitled to, gave me his confidence, and thus made me still more zealous to do something, if only to show my gratitude.

Having picked up all the information possible as regarded the movements of the slave vessels, we started on a cruise, our minds set particularly on the capture of a celebrated craft called the 'Lightning,' a vessel renowned for her great success as a slave ship, whose captain declared (this made our mission still more exciting) that he would show fight, especially if attacked by English men-of-war boats when away from the protection of their ships.

I must mention that it was the custom of the cruisers on the coast of Brazil to send their boats on detached service, they (the boats) going in one direction while the vessels they belonged to went in another, only communicating every two or three days. Proud indeed for me was the moment when, arriving near to the spot on the coast where the 'Lightning' was daily expected with her live cargo, I left my ship in command of three boats, viz., a ten-oared cutter and two four-oared whale boats. I had with me in all nineteen men, well armed and prepared, as I imagined, for every emergency. The night we left our ship we anchored late under the shelter of a small island, and all hands being tired from a long row in a hot sun, I let my men go to sleep during the short tropical darkness. As soon as the day was breaking all hands were alert, and we saw with delight a beautiful rakish-looking brig, crammed with slaves, close to the island behind which we had taken shelter, steering for a creek on the mainland a short distance from us. I ought to mention that the island in question was within four miles of this creek. We immediately prepared for action, and while serving out to each man his store of cartridges, I found to my horror that the percussion tubes and caps for the boat's gun, the muskets and pistols, had been left on board the ship. What was to be done? no use swearing at anybody. However, we pulled boldly out from under the shelter of the island, thinking to intimidate the slaver into heaving to. In this we were grievously mistaken.

The vessel with her men standing ready at their guns seemed to put on a defiant air as she sailed majestically past us, and although we managed with lucifer matches to fire the boat's gun once or twice, she treated us with sublime contempt and went on her way into the creek, at the rate of six or seven miles an hour. Though difficult to attack the vessel in the day time without firearms, I determined if possible not to lose altogether this splendid brig. I waited therefore till after sunset, and then pulled silently into the creek with muffled oars. There was our friend securely lashed to the rocks. We dashed on board with drawn cutlasses, anticipating an obstinate resistance. We got possession of the deck in no time, but on looking round for someone to fight with, saw nothing but a small black boy who, having been roused up from a sort of dog-kennel in which he had been sleeping, first looked astonished and then burst out laughing, pointing as he did so to the shore. Yes, the shore to which the slaver brig was lashed was the spot where seven hundred slaves (or nearly that number, for we found three or four half-dead negroes in the hold) and the crew had all gone, and left us lamenting our bad luck. However, I took possession of the vessel as she lay, and though threatened day and night by the natives, who kept up a constant fire from the neighbouring heights and seemed preparing to board us, maintained our hold upon the craft until the happy arrival of my ship, which, with a few rounds of grape, soon cleared the neighbourhood of our assailants. I may mention that, in the event of our having been boarded, we had prepared a warm reception for our enemies in the shape of buckets of boiling oil mixed with lime, which would have been poured on their devoted heads while in the act of climbing up the side. As they kept, however, at a respectful distance, our remedy was not tried. The vessel, a splendid brig of 400 tons, was then pulled off her rocky bed, and I was sent in charge of her to Rio de Janeiro. And now comes the strangest part of my adventures on this occasion.

On the early morning after I had parted company with my commanding officer, before the dawn, I ran accidentally right into a schooner loaded with slaves, also coming from Africa, bound to the same place as had been the brig, my prize.

Without the slightest hesitation, before the shock and surprise caused by the collision had given time for reflection or resistance, I took possession of this vessel, put the crew in irons, and hoisted English colours. There were 460 Africans on board, and what a sight it was!

The schooner had been eighty-five days at sea. They were short of water and provisions; three distinct diseases—namely, small-pox, ophthalmia, and diarrhœa in its worst form—had broken out while coming across among the poor doomed wretches.

On opening the hold we saw a mass of arms, legs, and bodies all crushed together. Many of the bodies to whom these limbs belonged were dead or dying. In fact, when we had made some sort of clearance among them we found in that fearful hold eleven dead bodies lying among the living freight. Water! water! was the cry. Many of them as soon as free jumped into the sea, partly from the delirious state they were in, partly because they had been told that, if taken by the English, they would be tortured and eaten. The latter I fancy they were accustomed to, but the former they had a wholesome dread of.

Can Mrs. Beecher Stowe beat this? It is, I can assure my readers, a very mild description of what I saw on board the first cargo of slaves I made the acquaintance of, and by which I was so deeply impressed, that I have ever since been sceptical of the benefits conferred upon the African race by our blockade—at all events, of the means employed to abolish slavery.

The strangest thing amid this 'confusion of horrors' was that children were constantly being born. In fact, just after I got on board, an unfortunate creature was delivered of a child close to where I was standing, and jumped into the sea, baby and all, immediately afterwards. She was saved with much difficulty; the more so, as she seemed to particularly object to being rescued from what nearly proved a watery grave.

After this unusual stroke of good luck, sending a prize crew on board my new capture, and allowing the slaver's crew to escape in the schooner's boat, as I considered these lawless ruffians an impediment to my movements, I proceeded on my voyage, and arrived safely in Rio harbour with my two prizes.

There I handed my live cargo over to the English authorities, who had a special large and roomy vessel lying in the harbour for the reception of the now free niggers.

It would be as well perhaps to state what became of the freed blacks. First of all they were cleaned, clothed (after a fashion), and fed; then they were sent to an English colony, such for example as Demerara, where they had to serve seven years as apprentices (something, I must admit, very like slavery), after which they were free for ever and all. I fear they generally used their freedom in a way that made them a public nuisance wherever they were. However, they were free, and that satisfied the philanthropists.

Now to return to my 'experiences.' As proud as the young sportsman when he has killed his first stag, I returned, keen as mustard, to my ship, which I found still cruising near to where I had left her. Some secret information that I had received while at Rio led me to ask my captain to again send me away with a force similar to that which I had under me before (with percussion caps this time), and allow me to station myself some fifty miles further down the coast. My request was granted, and away I went. This time, instead of taking shelter under an island, I ensconced my little force behind a point of land which enabled me by mounting on the rocks to sweep the horizon with a spy-glass, so that I could discover any vessel approaching the land while she was yet at a considerable distance.

There happened to be a large coffee plantation in my immediate neighbourhood, and I remarked that the inhabitants favoured us with the darkest of scowls whenever we met them. This made me believe (and I wasn't far out) that the slave-vessel I was looking out for was bringing recruits to the already numerous slaves employed on the said plantation. Two or three mornings after my arrival, I discovered a sail on the very far horizon; a vessel evidently bound to the immediate neighbourhood I had chosen as my look-out place. The winds were baffling and light, as usual in the morning in these latitudes, where, however, there is always a sea-breeze in the afternoon. So, being in no hurry, I sauntered about the shore with my double-barrelled gun in my hand, occasionally taking a look seaward. Suddenly I saw within a hundred yards of me a man leading two enormous dogs in a leash. The dogs were of a breed well known among slave-owners, as they were trained to run down runaway slaves. I believe the land of their origin is Cuba, as they are called Cuba bloodhounds.

Suspecting nothing I continued my lounge, turning my back on the man and his dogs. A few minutes afterwards I was startled by a rushing sound behind me. On turning quickly round I saw to my horror two huge dogs galloping straight at me. Quick as lightning I stood on the defensive, and when they with open mouths and bloodshot eyes were within five yards, I pulled the trigger. The gun missed fire with the first barrel. The second barrel luckily went off, scattering the brains of the nearest dog, the whole charge having entered his mouth, and gone through the palate into his brain. This occurrence seemed to check the advance of the second brute, who, while hesitating for a moment before coming at me, received a ball in his side from one of my sailors, who fortunately had observed what was going on and had come to my rescue. Without waiting an instant to see what had become of the man who had played me this murderous trick, I called my men together, launched the boats, and put out to sea.

By this time the sea-breeze had set in, and I could see the vessel I had been watching, though still a considerable distance from the shore, was trimming her sails to the sea-breeze, and steering straight in for the very spot where I had been concealed. Signal after signal was made to her by her friends on the shore, in the shape of lighted fires (not much avail in the daytime) and the hoisting of flags, &c., but she seemed utterly to disregard the action of her friends. Satisfied, I imagine, that she had all but finished her voyage, seeing no cruiser and unsuspicious of boats, on she came.[1]

We got almost alongside of her before the people on board seemed to see us. When she did, evidently taken by surprise, she put her helm down, and throwing all her sails aback, snapped some of her lighter spars, thus throwing everything into confusion—confusion made worse by the fact that, with the view of immediate landing, two hundred or three hundred of the niggers had been freed from their confinement and were crowded on the deck. Taking advantage of this state of things we made our capture without a shot being fired.

In fact everything was done, as sailors say, 'before you could look round you,' the man at the helm replaced by one of my men, the crew bundled down into the slave-hold to give them a taste of its horrors, and the sails trimmed for seaward instead of towards the land. The captain, who seemed a decent fellow, cried like a child. He said: 'If I had seen you five minutes before you would never have taken me. Now I am ruined.' I consoled him as well as I could and treated him well, as he really seemed half a gentleman, if not entirely one. I found about six hundred slaves, men and women and children, on board this vessel, who as they had made a very rapid and prosperous voyage, were in a somewhat better state than those on board the last capture. Still goodness knows their state was disgusting enough. Ophthalmia had got a terrible hold of the poor wretches. In many of the cases the patient was stone blind. I caught this painful disease myself, and for several days couldn't see a yard.

Shortly after, having despatched our prize into Rio in charge of a brother midshipman, we were joined by another man-of-war cruiser, which had been sent to assist us in our work. As the officer in command of this vessel was of senior rank to my commander, he naturally took upon himself to organise another boat expedition, placing one of his own officers in command. With this expedition I was allowed to go, taking with me my old boats and their crews, with orders to place myself under the direction of Lieutenant A.C., the officer chosen by the senior in command.

So we started with five boats provisioned and otherwise prepared for a cruise of twenty days. The lieutenant in charge did not think it wise to land, as a bad feeling towards us was known to exist among the inhabitants, who were all more or less slave-dealers, or interested in the success of the slave-vessels, so we had to live in our boats. Rather hard lines, sleeping on the boat's thwarts, &c. Still we had that 'balm of Gilead,' hope, to keep us alive, and our good spirits. Many a longing eye did I cast to the shore, where, in spite of the bloodhounds, I should like to have stretched my cramped limbs. Ten or twelve days passed in dodging about, doing nothing but keeping a good look-out, and we almost began to despair, when one fine morning we saw a large brig, evidently a slaver, running in towards the shore with a fresh breeze. Our boats were painted like fishing boats, and our men disguised as fishermen, as usual; so, apparently occupied with our pretended business, we gradually approached the slave-vessel. My orders were strictly to follow the movements or action of my superior. Then I witnessed a gallant act, such as I have not seen surpassed during forty years of active service that I have gone through since that time. Lieutenant A.C., who was in the leading boat, a large twelve-oared cutter, edged pretty near to the advancing vessel, and when quite close under her bows one man seemed to me to spring like a chamois on board. I saw the boat from which the man jumped make an ineffectual attempt to get alongside the vessel, that was going at the rate of six miles an hour, and then drop astern. I heard a pistol shot, and suddenly the vessel was thrown up in the wind with all her sails aback, thus entirely stopping her way (sailors will understand this). Not knowing precisely what had happened, we pulled like maniacs alongside of the slaver. To do this was, now that the vessel's way was stopped, comparatively easy. We dashed on board, and after a slight resistance on the part of the slaver's crew, in which two or three more men, myself among the number, were wounded, we took possession of the brig. There we found our lieutenant standing calmly at the helm, which was a long wooden tiller. He it was who had jumped on board alone, shot the man at the helm, put the said helm down with his leg, while in his hand he held his other pistol, with which he threatened to shoot any one who dared to touch him.

I fancy that his cool pluck had caused a panic among the undisciplined crew, a panic that our rapid approach tended much to increase. What astonished me was that nobody on board thought of shooting him before he got to the helm, in which case we never could have got on board the vessel, considering the speed she was going through the water. What he did was a glorious piece of pluck, that in these days would have been rewarded with the Victoria Cross as the least recompense they could have given to so gallant an officer. Poor fellow! all the reward he got, beyond the intense admiration of those who saw him, was a bad attack of small-pox from the diseased animals (there is no other name for negroes in the state they were in) on board the slave-vessel, which somewhat injured the face of one of the handsomest men I ever saw. He is now an admiral, has done many gallant acts since then, but none could beat what he did on that memorable morning.

I have said that I was among those who were wounded on this occasion. What my friend A.C. did so far outshone anything that I had accomplished, that it is hardly worth while speaking of my share in the fray. However, as I am writing sketches from my life, I will not omit to describe the way in which I was wounded. We were, as I have said, making a rush to assist our gallant leader, who was alone on board the slaver. The reader will have seen that our business was boarding and fighting our enemy hand to hand. As I was making a jump on board I saw the white of the eye of a great black man turned on me; he brandished a huge axe, which I had a sort of presentiment was intended for me. I sprang as it were straight at my destiny, for as I grasped the gunnel down came the axe, and I received the full edge of the beastly thing across the back of my hand. I fell into the water, but was picked up by my sailors, and managed to get on board again. Had it not been for a clever young assistant surgeon, who bound up the wound in a most scientific manner, I should probably have quite lost the use of my hand; the mark remains across my knuckles to this day.

I was once sent from Rio to Demerara, an English colony on the coast of Brazil, with a cargo of blacks that we had freed. Then it was that I had a good opportunity of studying the character of these people certainly in their primitive state, and if ever men and women resembled wild animals it was my swarthy charges. When I arrived at Demerara I handed them over to their new masters, to whom they were apprenticed for seven years, and from all I can understand they were, during their apprenticeship, treated pretty much as slaves in every respect.

During the time I visited Demerara (and I fancy it is very slightly changed now) it was one of the vilest holes in creation. It is built on a low sandy point of land at the entrance of a great river, and is almost the hottest place on the earth. Mosquitos in thousands of millions; nothing for the natives to do but to cultivate sugar-canes and to perspire. There were two crack regiments quartered at Demerara, who, having to withstand the dreadful monotony of doing nothing, took I fear to living rather too well; the consequence was that many a fine fellow had been carried off by yellow fever. For my part, I took a rather high flight in the way of pastime by falling (as I imagined) desperately in love with the governor's daughter. The governor, I must tell my readers, was a very great swell, a general, a K.C.B., &c., and his daughter was a mighty pretty girl, much run after by the garrison; so it was thought great impertinence on my part, as a humble sub-lieutenant, to presume to make love to the reigning, if not the only, beauty in the place.

However, audacity carried me on, and I soon became No. 1 in the young lady's estimation. I used to ride with her, spent the evenings in the balcony of Government House with her, sent her flowers every morning, and so on, till at last people began to talk, and steps were taken by her numerous admirers to stop my wild career. This was done in a somewhat startling way (premeditated, as I found out afterwards). One evening I was playing at whist, one of my opponents being a momentarily discarded lover of my young lady; I thought he was looking very distrait; however, things went off quietly enough for some time, till on some trifling question arising concerning the rules of the game, the young man suddenly and quite gratuitously insulted me most grossly, ending his insolent conduct by throwing his cards in my face. This was more than I could put up with, so I called him out, and the next morning put a ball into his ankle, which prevented him dancing for a long time to come. He, being the best dancer in the colony, was rather severely punished; it seems that he had undertaken to bell the cat, hardly expecting such unpleasant results.

On returning home after the hostile meeting I found a much more formidable adversary in the shape of the governor himself, who was stamping furiously up and down the verandah of my apartment. He received me with, 'What the d—- l do you mean, young sir, by making love to my daughter? you are a mere boy.' (I was twenty and did not relish his remark.) 'What means have you got?'

After the old gentleman's steam had gone down a little I replied, 'Really, general, I hardly know how to answer you. Your daughter and I are very good friends, the place is most detestably dull, there is nothing to do, and if we amuse ourselves with a little love-making, surely there can be no great harm.' This rejoinder of mine made things worse; I thought the old boy would have had a fit. At last he said, 'The mail steamer leaves for England to-morrow; you shall go home by her, I order you to do so!' I replied that I should please myself, and that I was not under his orders. The general went away uttering threats. After he was gone I thought seriously over the matter. I calculated that my income of 120l. a year would scarcely suffice to keep a wife, and I decided to renounce my dream of love. I went to pay a farewell visit to my young lady, but found that she was locked up, so away I went and soon forgot all about it. Shortly afterwards I heard that the governor's daughter married the man whose leg I had lamed for his impertinence to me.

My last adventure while employed in the suppression of the slave trade is perhaps worth describing.

By international law it was ruled that a vessel on her way to Africa, if fitted out in a certain manner, whereby it was evident that she was employed in the nefarious traffic of slavery, was liable to capture and condemnation by the mixed tribunals, or in other words became the lawful prize of her captors.

While cruising off Pernambuco we boarded a Portuguese vessel bound to Africa, so evidently fitted out for the purpose of slave trade that my captain took possession of her, and sent me to convey her to the Cape of Good Hope for adjudication. It was the usual thing to send the captain of a vessel so captured as a prisoner on board his ship, so that he might be interrogated at the trial. In this case the master and three of his crew were sent. The prize crew consisted of myself and six men. Now the captain was an exceedingly gentlemanlike man, a good sailor, and a first-rate navigator.

At first I treated him as a prisoner, but by degrees he insinuated himself into my good graces to such an extent that after a while I invited him to mess with me, in fact, made a friend of him, little thinking of the serpent I was nourishing.

For several days all went well. I was as unsuspicious as a child of foul play. We lived together and worked our daily navigation together, played at cards together, in fact were quite chums. The three men who were supposed to be prisoners were allowed considerable liberty, and as they had, as I found out afterwards, a private stock of grog stowed away somewhere, which they occasionally produced and gave to my men, they managed to be pretty free to do as they wished. For all that, I ordered that the three prisoners should be confined below during the night.

As the weather was very hot I always slept in a little place on deck called a bunk, a thing more like a dog-kennel than aught else I can compare it to, excepting that the hole for entrance and exit was somewhat larger than that generally used for the canine species.

I always slept with a pistol (revolvers were unknown in those days) under my pillow. Luckily for me that I did so, as the result will show.

I had remarked (this I thought of afterwards) that the prisoner captain and some of his men had been whispering together a good deal lately; but not being in the slightest degree suspicious I thought nothing of it.

One evening I retired to my sleeping place as usual, after having passed a pleasant chatty evening with my prisoner. I was settling myself to sleep, in fact I think I was asleep as far as it would be called so, for I had from habit the custom of sleeping with one eye open, when I saw or felt the flash of a knife over my head. The entrance to my couch was very limited, so that my would-be murderer had some difficulty in striking the fatal blow. Instinct at once showed me my danger.