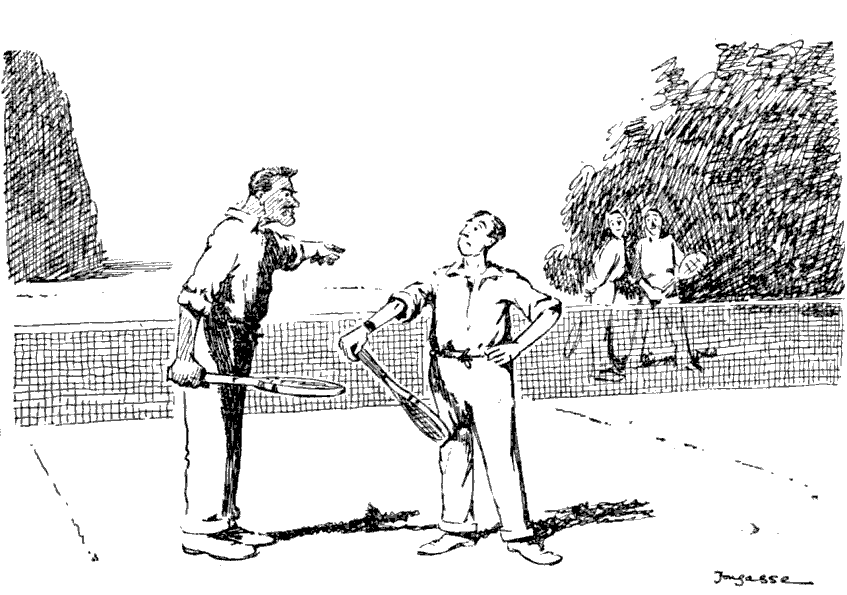

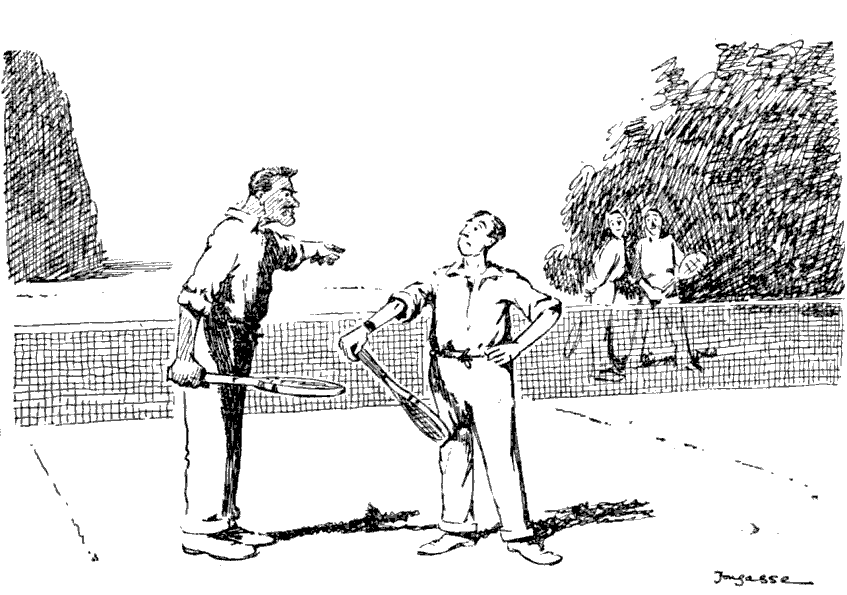

Exasperated Partner. "Look here—don't you ever get your service into the right court?"

Partner. "No, as a matter of fact I don't. But it would be absolutely unplayable if I did."

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Punch, or the London Charivari, Vol. 159, August 18th, 1920, by Various This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net Title: Punch, or the London Charivari, Vol. 159, August 18th, 1920 Author: Various Release Date: September 17, 2005 [EBook #16707] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK PUNCH *** Produced by Jonathan Ingram, Keith Edkins and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

The grouse-shooting reports are coming in. Already one of the newly-rich has sent a brace of gamekeepers to the local hospital.

"A few hours in Cork," says a Daily Mail correspondent, "will convince anyone that a civil war is near." A civil war, it should be explained, is one in which the civilians are at war but the military are not.

Lisburn Urban Council has decided to buy an army hut for use as a day nursery. It is this policy of petty insult that is bound in the end to goad the military forces in Ireland to reprisals.

"Who invented railways?" asks a weekly paper. We can only say we know somebody who butted in later.

"Mr. Churchill," says a contemporary, "has some friends still." It will be noticed that they are very still.

"It may interest your readers to know," writes a correspondent, "that it would take four days and nights, seven hours, fifty-two minutes and ten seconds to count one day's circulation of The Daily Mail." Holiday-makers waiting for the shower to blow over should certainly try it.

Coloured grocery sugars, the Food Controller announces, are to be freed from control on September 6th. A coloured grocery is one in which the grocer is not as black as he is painted.

A conference of sanitary inspectors at Leeds has been considering the question, "When is a house unfit for habitation?" The most dependable sign is the owner's description of it as a "charming old-world residence."

The Warrington Watch Committee, says a news item, have before them an unusual number of applications for pawnbrokers' licences. In the absence of any protest from the Sleeve Links and Scarf Pin Committee they will probably be granted.

"I earn three pounds and fourpence a week," an applicant told the Willesden Police Court, "out of which I give my wife three pounds." The man may be a model husband, of course, but before taking it for granted we should want to know what he does with that fourpence.

Scarborough Corporation has fitted up and let a number of bathing vans for eight shillings a week each. To avoid overcrowding not more than three families will be allowed to live in one van.

"Three times in four days," says a Daily Express report, "a Parisian has thrown his wife out of a bedroom window." Later reports point out that all is now quiet, as the fellow has found his collar-stud.

"Who Will Fight For England?" asks a headline. To avoid ill-feeling a better plan would be to get Sir Eric Geddes to give it to you.

A noiseless gun has just been invented. It will now be possible to wage war without the enemy complaining of headache.

"Everyone sending clothes to a laundry should mark them plainly so that they can be easily recognised," advises a weekly journal. It is nice to know that should an article not come back again you will be able to assure yourself that it was yours.

At the present moment, we read, dogs are being imported in large numbers. It should be pointed out, however, that dachshunds are still sold in lengths.

A contemporary complains of the high cost of running a motor-car to-day. It is not so much the high price of petrol, we gather, as the rising cost of pedestrian.

The police, while investigating a case of burglary in a railway buffet, discovered a bent crowbar. This seems to prove that the thieves tried to break into a railway sandwich.

Mexican rebels have been ordered to stop indiscriminate shooting. It is feared that the supply of Presidential Candidates is in danger of running out.

"A Manchester octogenarian has just married a woman of eighty-six," says a news item. It should be pointed out, however, that he obtained her parents' consent.

"Although the old penny bun is now sold for twopence or even threepence it contains three times the number of currants," announces an evening paper. This should mean three currants in each bun.

A parrot belonging to a bargee escaped near Atherstone in Warwickshire last week and has not yet been recaptured. We understand that all children under fourteen living in the neighbourhood are being kept indoors, whilst local golfers have been sent out to act as decoys.

It is announced that a baby born in Ramsgate on August 6th is to be christened "Geddes." We are given to understand that the news has not yet been broken to the unfortunate infant.

Exasperated Partner. "Look here—don't you ever get your service into the right court?"

Partner. "No, as a matter of fact I don't. But it would be absolutely unplayable if I did."

"Bishop —— says he will not be able to consider any more proposals for engagements till after the summer of 1921."—Local Paper.

An Echo from Bisley.—A musical correspondent writes to point out that sol-faists have an unfair advantage in the running-deer competition, because they are always practising with a "movable Doh."

Grogtown.—All available accommodation has been monopolised by Glasborough visitors, among whom this resort is becoming more alarmingly popular every year. Sixty charabancs arrived on Monday and the Riot Act was read several times before the passengers could be induced to desist from their badinage of the residents, most of whom have since retired behind the wire-entanglements at Kelrose. The municipal orchestra was subjected to a brisk fusillade of rock-cakes on Saturday night; the conductor and several of the instrumentalists suffered contusions, and their performances have since been discontinued. This has not unnaturally given rise to a certain amount of dissatisfaction amongst the visitors, but otherwise there has been no recrudescence of rioting. A company of the Caithness Highlanders, with machine-guns, are now encamped on the links, and sunshine is all that is needed to complete the success of the season.

Kegness.—On Tuesday the Mayor presented a jar of whisky, fifty years old, to the winning charabanc team in the bottle-throwing competition, and the subsequent scenes afforded much diversion. A notable feature at present is a large whale, which was washed ashore in a gale about six months ago. The oldest inhabitants declare that they have never known anything like it, and it is certainly an unforgettable experience to be anywhere within a mile of this apparently immovable derelict. Excursions to all surrounding places out of nose-shot are extremely popular, and the beach is practically deserted save by a few juvenile natives engaged in the blubber industry.

Mudhall Spa.—Without the least reflection on chalybeates and the rest, it must be allowed that the most popular beverage in Mudhall at present is that which draws its virtue from a cereal and not a mineral source. Hilarity is rife at all hours, and the effort to enlist a body of local volunteers to control the exuberance of anti-Sabbatarian "charabankers" is meeting with unexpected support. The casualties in the daily collisions between the Hydropathic League and the Anti-Pussy-Foot-Guards are steadily increasing and now compare favourably with those of any other Midland health-resort.

"A Boylston (Massachusetts) farm labourer is said to havt bees identified as one of the heirs to a £400,000 estate at Dundte, for whom starches have betn made for years, but nothing is known at Dundee of such an estate."—Daily Paper.

But this lucid paragraph should help to clear up the mystery.

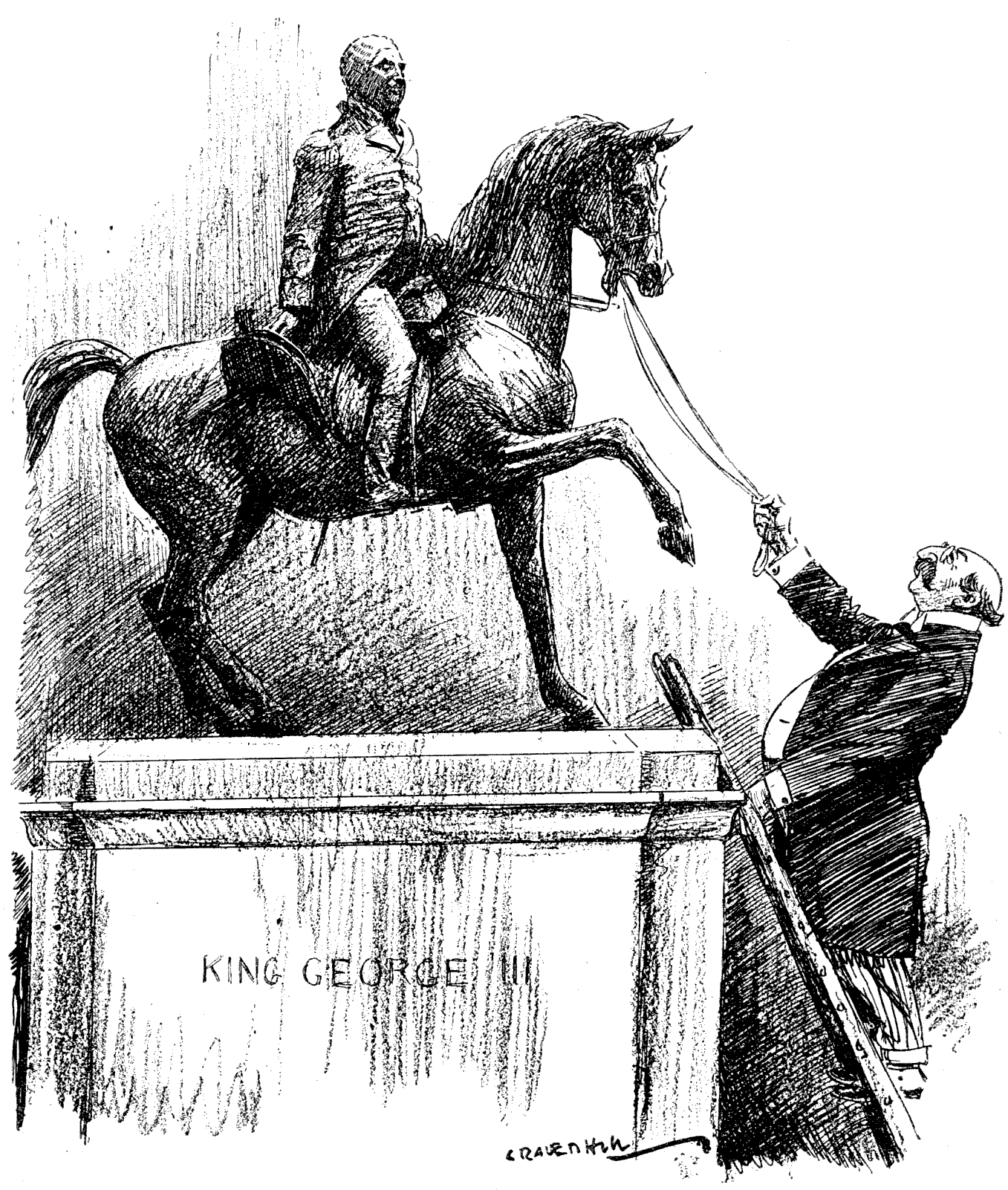

The rumour that a number of London's statues are to be moved to make room for new has caused many a marble heart to beat faster; and on making a round of calls I gathered that Sir Alfred Mond has few friends in stone or bronze circles. Not the least uneasy is George IV. in Trafalgar Square. Uneasiness of body he has always known, riding there for ever without any stirrups; but now his mind is uneasy too. "If they take Father from Cockspur Street," he argued very naturally, "why not me?"

A few of the figures feel secure, of course, but very few. Nelson on his column has no fears; Nurse Cavell is too recent to tremble; so is Abraham Lincoln. But the others? They are in a state of nervous suspense, wondering if the sentence of banishment is to fall and resenting any disturbance of their lives. "J'y suis, j'y reste" is their motto.

Abraham Lincoln gave me a hearty welcome and extended an invitation that is not within the power of any other graven image in the city. "Take a chair," he said.

I did so and am thus, I suppose, the first Londoner to put that comfortable piece of furniture to its proper use.

"How do you like being here?" I asked.

He said that he enjoyed it. The only blot on his pleasure was the fear that the Abbey might fall on him, and he therefore hoped that The Times' fund was progressing by leaps and bounds.

His immediate neighbours, on the contrary, exhibited no serenity whatever, and I found Canning and Palmerston shivering with apprehension in their frockcoats. The worst of it was that I could say nothing to reassure them.

Here and there, however, a desire for locomotion was expressed. Dr. Johnson, in the enclosure behind St. Clement Danes, is very restive. I asked him if he would object to removal. "Sir," said the Little Lexicographer (as his sculptor has made him), "I should derive satisfaction from it. A man cannot be considered as enviable who spends all his time in the contemplation, from an unvacatable position, of a street to the perambulation of which he devoted many of his happiest hours."

I ventured to agree.

"Nor," continued the sage, "is it a source of contentment to a man of integrity to observe an unceasing procession of Americans on their way to partake of pudding in a hostelry that has made its name and prosperity out of a mythical association with himself and be unable to correct the error."

"Are you in general in favour of statuary?" I made bold to ask.

"Painting," said he, "consumes labour not disproportionate to its effect; but a fellow will hack half a year at a block of marble to make something in stone that hardly resembles a man. Look around you; look at me. The value of statuary is owing to its difficulty. You would not value the finest head cut upon a carrot."

But one effect of this General Post among the statues is good, and it should delight Mr. Asquith. Cromwell, now outside Westminster Hall, is to be moved into the House.

FLOWERS' NAMES.

Marigolds.

As Mary was a-walking

All on a summer day,

The flowers all stood curtseying

And bowing in her way;

The blushing poppies hung their heads

And whispered Mary's name,

And all the wood anemones

Hung down their heads in shame.

The violet hid behind her leaves

And veiled her timid face,

And all the flowers bowed a-down,

For holy was the place.

Only a little common flower

Looked boldly up and smiled

To see the happy mother come

A-carrying her Child.

The little Child He laughed aloud

To see the smiling flower,

And as He laughed the Marigold

Turned gold in that same hour.

For she was gay and innocent—

He loved to see her so—

And from the splendour of His face

She caught a golden glow.

"I have just completed a fortnight's tour on a tandem, and can recommend this form of a holiday as the best I know of.... One Sunday in June, without exaggeration, I was nearly killed twice, and my wife was overcome with fright."—C.T.C. Gazette.

"In a competition at Claygate, Surrey, three children caught 182 green wasps."—Daily Paper.

It is believed that they would not have been caught if they had not been green.

From a recent Admiralty Order:—

"Approval has been given for frocks to be issued to N.C. Officers and men (Royal Marines) during the current year, for walking out purposes only."

It is believed that His Majesty's Jollies have received the order without enthusiasm, on the ground that no mention is made of anything being inside the frocks.

Sir Alfred Mond. "I'M SORRY TO HAVE TO DISTURB YOUR MAJESTY, BUT, OWING TO THE SHORTAGE OF SITES—"

George III. "SHORTAGE OF SIGHTS, INDEED!"

[It is understood that a number of London statues, including that of George III. in Cockspur Street, are to be removed by the Office of Works to make room for new ones.]

'Twas last week at Pebble Bay

That I saw the little goat,

Harnessed to a little shay.

Old was he and poor in coat,

And he lugged his load along

Where the barefoot children throng

Round the nigger minstrels' song.

But his eye, aloof and chill,

Said to me as plain as plain,

"I am waiting, waiting still,

Till the gods come back again;

Starved and ugly, mean, unkempt,

I have dreams by you undreamt,

And—I hold you in contempt!

"Dreams of forest routs that trooped,

Shadowy maidens crowned with vines,

Dreams where Dian's self has stooped

Darkling 'neath the scented pines;

Or where he, old father Pan,

Took the hooves of me and ran

Fluting through the heart of man.

"Surely he must come again,

He the great, the hornéd one?

Shan't I caper in his train

Through the hours of feast and fun!"

And he looked with eyes of jade

Through the sunshine, through the shade,

Far beyond Marine Parade.

* * * * *

Should you go to Pebble Bay,

Golfing or to bathe and boat—

Should you see a loaded shay,

In the shafts a scarecrow goat,

Tell him that you hope (with me)

Pan will shortly set him free,

Pipe him home to Arcady.

Mr. P.F. Warner has received countless expressions of regret on his retirement from first-class cricket. Among these he values not least a "round robin" from the sparrows at Lord's, all of whom he knows by name. In the score-book of Fate is this entry in letters of gold:

"Plum" c Anno b Domini 47.

Long may he live to enjoy the cricket of others!

The test team of Australia being now complete, all correspondence on the subject of its exclusions must cease. We therefore do not print a number of letters asking why there is no one named Geddes on the side.

Mr. Fender and Hobbs are said to be actuated by the same motto, "For Hearth and Home." Both are pledged to return covered with "the ashes."

In the recent Surrey and Middlesex match Mr. Skeet bewildered the crowd by fielding as if he liked it. Hitherto this vulgar manifestation has been confined to Hitch and Hendren.

Although so late in the season Yorkshire has great hopes of a colt named Hirst, who has just joined the side. He was seen bowling at Eton and was secured at once.

There is a strong feeling in Worcestershire that a single-wicket match between Lee of Middlesex and Mr. Perrin of Essex would be a very saucy affair.

"The Unknown."

Mr. Somerset Maugham, who recently intrigued and perhaps just a little scandalised the town with a most engagingly flippant and piquant farce all about an accidentally bigamous beauty, certainly shows courage in launching so serious a discussion as The Unknown. And in the silly season too. I see that in a quite unlikely interview (but then all modern interviews are unlikely) he defends his right to discuss religion quite openly on the stage. Of course. Why should anybody deny that religion is to the normally constituted mind, whatever its doxy, an absorbingly interesting subject; or that the War hasn't made a breach in the barriers of British reticence? Whether to the point of making a perfectly good married Vicar (anxious to convict a doubting D.S.O. of sin) ask in a full drawing-room containing the Vicaress, the Doctor and the D.S.O.'s fiancée, mother and father, "For instance, have you always been perfectly chaste?"—I am not so sure. Nor whether the War has really added to bereaved Mrs. Littlewood's bitter "And who is going to forgive God?" any added force. If that kind of question is to be asked at all it might have been asked, and with perhaps more justice, at any time within the historical period. For the War might reasonably be attributed by the Unknown Defendant thus starkly put upon trial to man's deliberate folly, whereas....

No doubt, however, Mr. Maugham would say the shock of war has (like any other great catastrophe) tested the faith of many who are personally deeply stricken and found it wanting, while the whisper of doubt has swelled the more readily as there are many to echo it. So Major John Wharton, D.S.O., M.C., having found war, contrary to his expectation of it as the most glorious manly sport in the world, a "muddy, mad, stinking, bloody business," loses the faith of his youth and says so, not with bravado but with regret. The Vicar, with dignity and restraint, but without much understanding and not without some hoary clichés; his wife, with venom (suggesting also incidentally sound argument for the celibacy of the clergy); the old Colonel and his sweet unselfish wife, with affection; and Sylvia, John's betrothed, with a strange passion, defend the old faith, Sylvia to the point of breaking with her lover and getting her to a nunnery—a business which will in the end, I should guess, lay a heavier burden upon the nuns than upon John. The indecisive battle sways hither and thither. It is the Doctor who sums up in a compromise which would shock the metaphysical theologian, but may suffice for the plain man, "God is merciful but not omnipotent. In His age-long fight against evil we can help—or hinder; why not help?"

The most signal thing was Miss Haidée Wright's personal triumph as Mrs. Littlewood—a very fine interpretation of an interesting character. Mr. Charles V. France adds another decent Colonel to his military repertory. This actor always plays with distinction and with an ease of which the art is so cleverly concealed as perhaps to rob him of his due meed of applause from the unperceptive. Lady Tree made a beautiful thing of the character of Mrs. Wharton, whose simple unselfishness was the best of all Mr. Maugham's arguments for the defence. Mr. R.H. Hignett nobly restrained himself from making a too parsonic parson, yet kept enough of the distinctive flavour to excite a passionate anti-clerical behind me into clamorously derisive laughter; a very good piece of work. Miss O'Malley acted a difficult, almost an impossibly difficult, part with a fine distinction. Mr. Basil Rathbone's Major and Mr. Blakiston's Doctor were excellent. I am sorry to be so monotonously approving....

I am not convinced that Mr. Maugham's experiment has succeeded.

"Mr. —— maintained that it was extraordinuary that if he was only slightly dead deceased did not hear the lorry."—Local Paper.

Most extraordinuary.

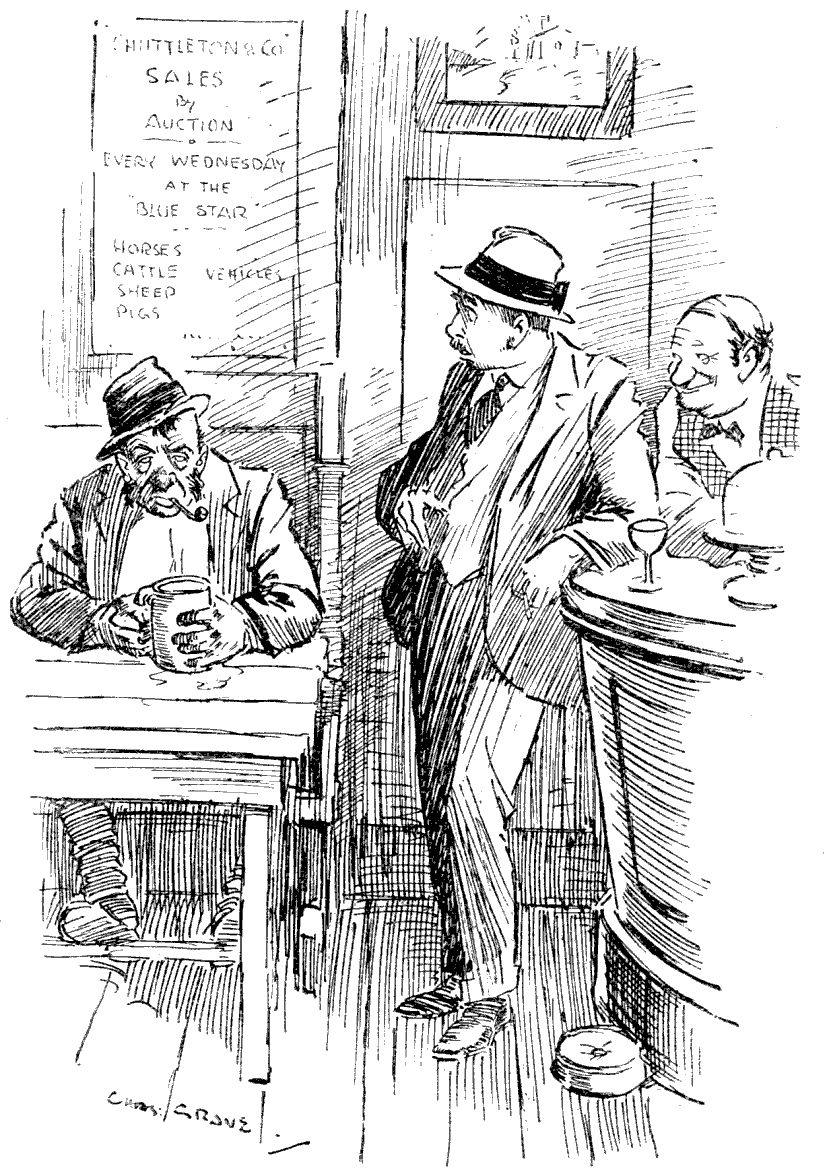

Generous Stranger. "Will you have another pint? (No answer.) I say—will you have another pint?"

Hodge. "Don't 'ee ask zilly questions. Order it."

George and I are two ordinary people. He studies the Weather Reports every day; I do occasionally. He thinks he understands meteorology; I don't. But lately I felt that I must have some explanation of the weather, so I asked George to explain it.

He said, "Certainly; it's quite simple. Take wind. Wind is caused by differences of pressure."

"What is pressure? Who is pressing what?"

"Pressure is what the barometer tells you—not the thermometer; you must keep the thermometer out of this. Suppose it is very hot in London—"

"Don't be ridiculous."

"Well, suppose it is very hot at a place A—"

"I thought we were keeping the thermometer out of this."

"It comes in indirectly. But don't keep interrupting. If it is very hot at the place A, the air at A rises. You see?"

"No."

"Obviously it does. If you light a candle—"

"Yes, yes, I do see that. Don't begin about candles."

"Well, the result of that is that there is less pressure at A. In other words, there is more room for the air to move about. When that happens the air at the place B—"

"Where is that?"

"Oh anywhere. I told you to think of two places, A and B."

"No, you told me to think of a place A, and I am still thinking of it, because it is very hot there."

"Well, this is another place, where the pressure is simply frightful. When the air rises at A the air from B rushes over to A to fill up the gap, and that is what we call wind."

"I see."

"No, you don't. It isn't quite so simple as that. Now, the atoms of air rushing from B to A don't go straight there, but they travel in—in sort of circles."

"Why do they do that?"

"Well, the fact is that these atoms are so keen to get over to A, where there is plenty of room, that they jostle each other, and that makes them go round and round. If they go round and round against the clock, like that, they are called cyclones, or depressions, or low-pressure systems. If they go with the clock, like that, it is an anti-cyclone."

"Oh!"

"What do you mean—'Oh'?"

"What I said; but go on."

"Now suppose this air—"

"Which air?"

"The air from B. Suppose it is travelling in a cyclone—"

"But isn't a cyclone a low-pressure thingummy?"

"Yes."

"And didn't you say that B was a high-pressure place?"

"Yes."

"Then how does the air coming from B manage to be low-pressure stuff?"

"I see what you mean. There is an explanation, but it would take too long to hazard it now. Suppose the air is coming from B in an anti-cyclone, then ..."

"All right. I'll suppose that."

"... it rushes over to A and fills up the gap. There is more pressure at A and the barometer goes up—"

"Is it fine then?"

"No, it rains. You see, the air from B is colder than the air at A was before the air came from B."

"I don't see."

"Well, obviously it must be."

"How 'obviously'?"

"Well, the whole thing started with it being very hot at A, you remember, so that the air rose. If it had been hotter still at B just then the air would have risen at B instead, and it couldn't have rushed over to A. There'd have been a frightful muddle."

"There is."

"Well, it's your own fault for interrupting. This air, then—"

"Which air is this?"

"The air from B. The air from B cools the air at A—"

"But I thought the air at A had risen."

"Not all of it. And that makes it rain."

"Why?"

"Oh, well, I can't go into that. It's something to do with condensation. Air absorbs more moisture when it is hot than when it is cold—"

"So do I. I understand that."

"When the air cools the water condenses."

"Is it fine then?"

"No, it rains, you fool."

"When is it fine?"

"Wait a bit. The falling of the rain of course generates heat—"

"Why 'of course'?"

"I can't explain exactly, but you know perfectly well that it's always warmer on a cold day after the rain."

"Yes, but not on a hot day."

"Yes, it is."

"No, it isn't."

"It is, really. Anyhow, this is a cold day."

"No, it isn't. You said it was very hot at A."

"I'm not going to argue. You must take it from me that rain generates heat."

"All right. Is it fine then?"

"No. Heat being generated the air rises. The result of that is that there is less pressure at A—"

"Is it fine then?"

"I've explained already what happens then. The air from B—"

"Do we begin all over again now?"

"More or less, yes."

"So that at this place, A, it's always raining or just going to rain?"

"Yes, if it starts by being hot there, as it did just now, I suppose it is."

"What happens if it starts by being cold?"

"It rains. I've explained that. The cold air can't contain so much moisture—"

"Don't begin that again. What about B? Is it any good going there? We had frightfully high pressure there at one time."

"Yes, but it rains so much at A that more and more air rushes from B to A to fill up the gap caused by the air rising on account of the heat generated by the rain falling, and very soon you get frightfully low pressure at B—"

"Is it fine then?"

"No, it rains."

"You surprise me. But suppose it had started by being low pressure at B?"

"Why, then of course it would have been raining the whole time at B."

"Where would A have got its rush of air from then?"

"From the place C."

"Is it fine there?"

"No, it's raining. It is like B was after the air rose at A."

"Oh. Then whatever happens at these places, A, B and C, it must rain."

"More or less, yes. More really."

"Are there any more places? I mean, if I am at A where ought I to go?"

"There is a place, D—"

"What happens there?"

"Conditions are favourable for the formation of secondary depressions."

"Then where do you advise me to go?"

"I'm not advising you. You asked me to explain the weather, and I have."

"I think you have. I understand it now."

I hope you all do.

"Sir,—I can recall no better description of a gentleman than this—

'A gentleman is one who never gives offence unintentionally.'

Unfortunately I do not know to whom tribute should be paid for this very neat and apt definition."—Letter in Daily Paper.

We rather think the printer had a hand in it.

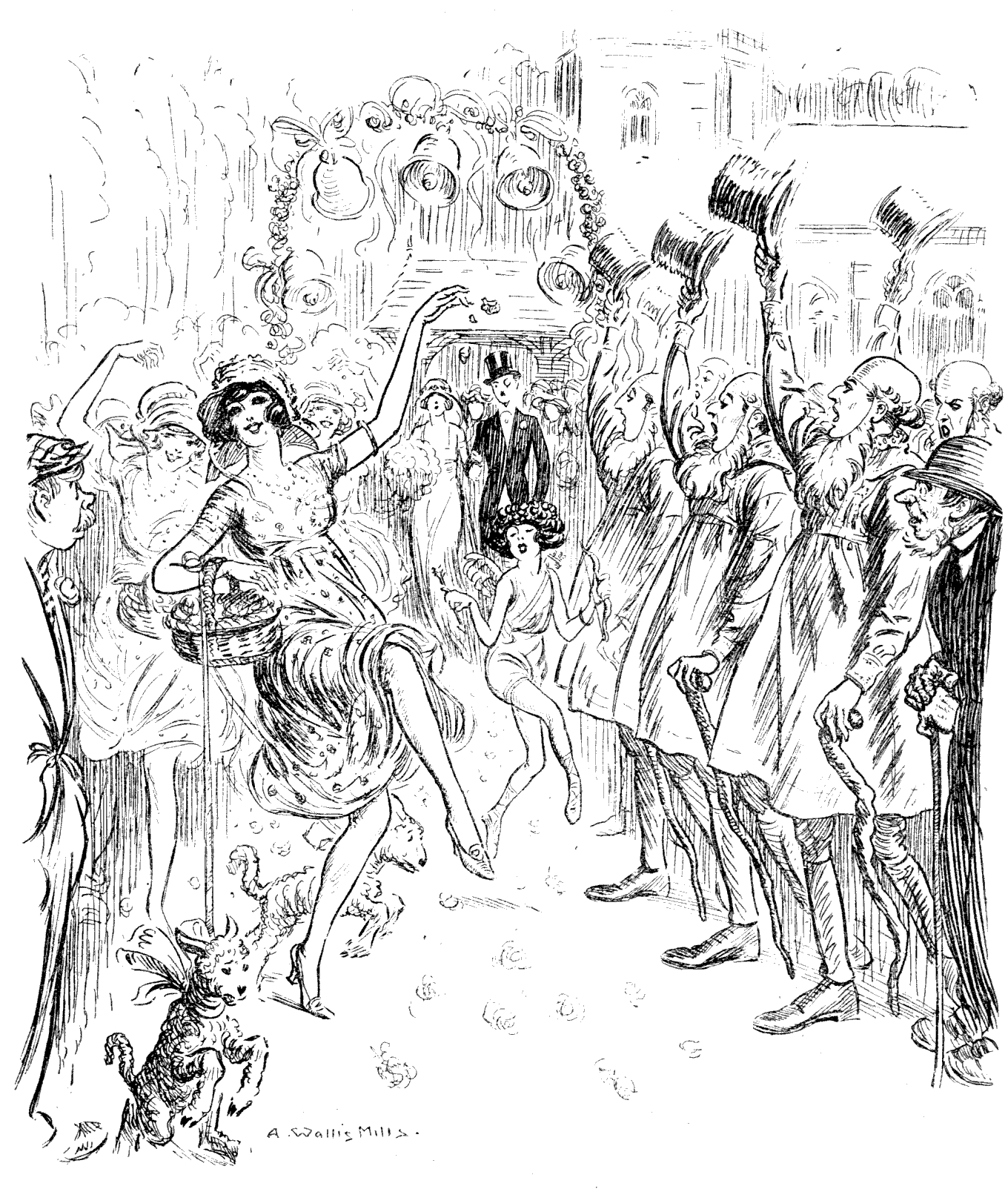

THE DIFFICULTY OF OBTAINING THE CORRECT ATMOSPHERE AT COUNTRY WEDDINGS, OWING TO THE CHANGED CONDITIONS OF VILLAGE LIFE, HAS LED MESSRS. HARRIDGES TO COME TO AN ARRANGEMENT WITH THE CHORUS OF THE FRIVOLITY THEATRE TO ATTEND AND FURNISH THE REQUISITE NOTE OF PICTURESQUE SIMPLICITY. TERMS ON APPLICATION.

Guide (after ascent of a hundred-and-twenty steps). "These, Sir, are the famous gargoyles I mentioned."

Perspiring American. "Gee! I thought you said 'gargles.'"

Little Mr. Bowles was very happy as long as he was only second mechanic at the garage of Messrs. Smith Brothers, of High Street, Puddlesby. It was when he became a member of the Puddlesby Psychical Society that his troubles began. Up till then he had been as sober and hard-working a little man as ever stood four foot ten in his shoes and weighed in at seven stone four. But above all he was an expert in rubber tyres; he knew them, I had almost said, by instinct.

The Puddlesby Psychical Society believes in the Transmigration of Souls. As I am not a member myself I'm afraid that that is all I can tell you about it. It is a little difficult at first sight, perhaps, to see the connection between Transmigration and rubber tyres, but if you will have patience I think I can promise to show you that at least.

One night our Mr. Bowles came home late from a meeting of the P.P.S., fell asleep at once and had what he regarded as a "transmigratory experience in a retrogressive sense." The world was not the world he knew. He perceived that it was sundown on the 8th of August, 1215, that he was no longer plain Bowles, but rather Sir Bors the Bowless, Knight of the Artful Arm, and known to his intimates as "The Fire-eater"; that he had just been challenged to fight his seven hundred and forty-seventh fight, and (for the seven hundred and forty-seventh time) he had accepted. He soon added to the stock of his information the fact that, as the challenged party, he had the choice of time, place and weapons.

He was naturally a little perturbed at first, for the most formidable warrior that he ever remembered fighting was his little sister, whose hair he had pulled when they were children, and the biggest thing he had ever killed was undoubtedly the hen that he had run over on the Boodle Road. He felt inclined, therefore, in the first flush of terror, to propose as the time 1925, as the place Puddlesby Football Field, and as the weapon, motor-tyre valve pins, at two hundred yards. He even got as far as mentioning these conditions to his friend Sir Hugh the Hairy, who, however, did not seem particularly struck with the suggestion, but made a counter-proposal of maces on horseback at the neighbouring lists in three days' time.

Before our hero knew what he was about he found that he had agreed. He got through a deal of heavy thinking on his way home to his castle, but had fortunately completed his plan of campaign before he arrived, for the esquire of his enemy was awaiting him there, demanding to know the details of the coming contest. He made the conditions suggested by Sir Hugh, merely adding that the maces must be smooth and not knobbed, as was customary in the better-class combats of that day.

He then began to make his preparations. At first he was considerably depressed by the entire absence of all rubber, until dire necessity compelled him to find a serviceable substitute in the shape of untanned ox-skins. These he carefully sewed together with his own knightly hands, coating the stitches over with pitch and resin. He was a good workman and did not fail to be ready in time.

When the hour of combat arrived he vanished into the painted pavilion reserved for him at one end of the lists, accompanied only by his faithful esquire. Hastily he donned his suiting of reinforced ox-hide, which covered the whole of his person from head to foot, and hung stiffly in folds all round him. Then, holding out a metal tube which was attached to the front of the costume, he presented it to his esquire, saying in the vernacular of those stout times—

"Ho, varlet! Blow me down yon hole till there be no more breath in thy vile bodie. Blow me hard and leally. Blow an thou burst in ye blowinge."

Whereupon the trusty varlet blew.

Thus it fell out that when the trumpet sounded and the Black Baron of Beaumaris, his foe, rode forth from his sable pavilion, armed cap-à-pie in a suit of highly-polished steel and bestriding a black and rather over-dressed charger, he saw through the chinks of his lowered visor an object which he would undoubtedly have mistaken for a diminutive observation balloon if he had lived a few centuries later. In short, Sir Bowles, having been sufficiently inflated by his now exhausted esquire, had inserted his valve-pin into the tube (which he had tucked away and laced up like an association football), and now emerged upon the lists with a feeling of elation that he had not experienced for several days.

They approached each other. It was with some difficulty that our hero wielded his mace, owing, first, to the inflated condition of his right arm, and, secondly, to the unaccustomed weight of the weapon. His hold also upon his curvetting steed was a little precarious, and he hoped that no one in the crowd would notice the string that tied his legs together beneath the horse's belly.

If the Baron was surprised at what he saw he made no sign, but, riding straight at his strange antagonist, he dealt him a mighty blow on the left side of the head, which had quite an unlooked-for result. The string which attached our hero's legs held, it is true, but he naturally lost his balance, and, being knocked to the right, disappeared temporarily from the Baron's view. But the force of his swing was such that, at the moment when he was head downwards under the horse, he still had enough way on to bring him up again on the other side. No sooner had he regained a vertical position than the Baron repeated the blow on the same spot and with the same result.

Then the same thing happened again and again; and indeed Sir Bowles might have revolved indefinitely, to the intense delight of the distinguished audience, had not the string broken at the thirty-fourth revolution.

[pg 129]Now the involuntary movements of our hero had accelerated at every turn, and when finally he parted company with his trusty steed he was going very fast indeed. Falling near the edge of the lists, he found touch, first bounce, in the Royal Box, whence some officious persons rolled him back again into the field of play.

It must not be supposed that poor Sir Bowles was comfortable during these proceedings. The rather ingenious apparatus whereby he had hoped to catch a glimpse of his adversary had got out of order at the first onslaught, and he was in total darkness. Moreover, he soon discovered that the haughty Baron was taking all sorts of liberties with him; was slogging him round the lists; in short, was playing polo with him.

But apart from the physical and mental discomfort of his situation he was not actually hurt, and at length he felt himself come to rest. The Baron, worn out by his unproductive labours, was thinking.

So was Bowles. He was just saying to himself, "Thank heaven I thought of choosing smooth maces. A spike would have punctured the cover in no time," when he felt something which made his hair stand on end.

His enemy was fumbling at the lacing of his tunic!

Then poor little Sir Bowles gave himself up for lost and almost swooned away. He felt the Baron undo the lace and pull out the tube. There was a perplexed pause....

And just as the Baron was pulling out the valve pin little Mr. Bowles woke with a shriek.

I suppose it was the fact that he had come straight from a symposium on transmigration that made little Bowles imagine he had been recurring to a previous existence. I myself should have thought that the rules of the game required the reincarnation of Sir Bors to be a rather more bloodthirsty and pugnacious person than our hero; and the sequel seems to prove that little Bowles thought the same. I think he felt he was not quite the man for this sort of rough work, even in the retrospect of dreams. Anyway, shortly after his painful experience he withdrew his subscription from the Puddlesby Psychical Society and ceased for ever to assist at their séances.

The Overland Route.

"MAIL AND STEAMSHIP NEWS.

Morea, Bombay for London, at Verseilles, 8th."—Scottish Paper.

"James ——, a boy of 13, was charged at Belgium, Greece, V and Czecho-Slovakia, and pleaded that he took the money because he felt he must have some amusement."—Evening Paper.

The little Bolshevist!

A "Historic Estate" is announced for sale in the following terms by a contemporary:—

"In the Heart of the Albrighton Country, and in direst railway communication with Birmingham, Wolverhampton, Manchester, Bristol and other northern and western centres."

Evidently a case where evil communications corrupt good spelling.

From a feuilleton:—

"Before the podgy dealer knew what had happened, she had sprung right round him, seized the telephone instrument and placed her mouth to the receiver. She smiled at him defiantly. 'Yes, I will,' she panted."—Daily Paper.

And then, we suppose, she wrote to the Postmaster-General to complain of the inefficiency of the service.

Junior Partner of Firm (exempted on business grounds during the War, interviewing applicant for employment, a demobilised officer, D.S.O., M.C., mentioned twice in despatches and wounded three times). "You say you were three-and-a-half years in France and yet don't speak the language? It seems to me you wasted your time abroad, Sir."

(By a Student of Manners.)

The Roman satirist sang of poets reciting their verses in the month of August. If he were alive now he would find as fruitful a subject in the renovations and decorations of Clubland. Clubs are strange institutions; they go in for Autumn not Spring cleaning. Happily all Clubs are not renovated at the same time, otherwise the destitution of members would be pitiful to contemplate. Even as it is the temporary accommodation offered by their neighbours is not unattended by serious drawbacks. The standard of efficiency in bridge and billiards is not the same; the cuisine of one Club, though admirable in itself, may not suit the digestions of members of another; the opportunities for repose vary considerably. In short, August and September are trying months for the clubman who is obliged to remain in London. But by October Pall Mall is itself again, and we are glad to be able to state that in certain Clubs the amenities and comforts available will be greatly enhanced.

For example the Megatherium, which is now in the hands of the decorators, is being painted a pale pink outside, a colour which recent experiments have shown to exert a peculiarly humanising and tranquillising influence on persons of an irritable disposition. A sumptuous dormitory is being erected on the top floor, where slow music will be discoursed every afternoon, from three to seven, by a Czecho-Slovak orchestra. A roof-garden is being laid out for the recreation of the staff, and the velocity of the numerous lifts has been keyed up to concert pitch. Steam heat will be conveyed from the basement to radiators on every floor, and each room is being provided with a vacuum-cleaning apparatus, a wireless telephonic outfit and an American bar. The renovation of the library is practically complete, the obsolete books which cumbered its shelves having been replaced by the works of Dell, Barclay, Wells, Zane Grey and Bennett. Three interesting rumours about the future of the Club may be given with due reserve—the first, that in the near future women will be admitted to membership; the second, that Lord Ascliffe has obtained a complete control of its resources; and the third, that its name will be shortly changed to "Alfred's," on the analogy of "Arthur's."

From Smith Minor's French Paper:

"Translate 'La femme avait une chatte qui était très méchante.'—'The farmer was having a chat with thirteen merchants.'"

"Archbishop Mannix ... says he can go anywhere in England except to Liverpool, Manchester, Glasgow and possibly Fishguard."—Daily Mirror.

Another injustice to Scotland.

"But this Bill creates new grounds for the dissolution of the marriage bond, which are unknown to the law of Scotland. Cruelty, incurable sanity, or habitual drunkenness are proposed as separate grounds of divorce."—Scotch Paper.

And so many Scotsmen are incurably sane.

Poland (to Mr. Lloyd George, organizer of the Human Chess Tournament). "HOW ARE YOU GOING TO PLAY THE GAME? I WAS LED TO BELIEVE I WAS TO BE A QUEEN, BUT I FIND I'M ONLY A PAWN."

GOING TO THE COUNTRY?

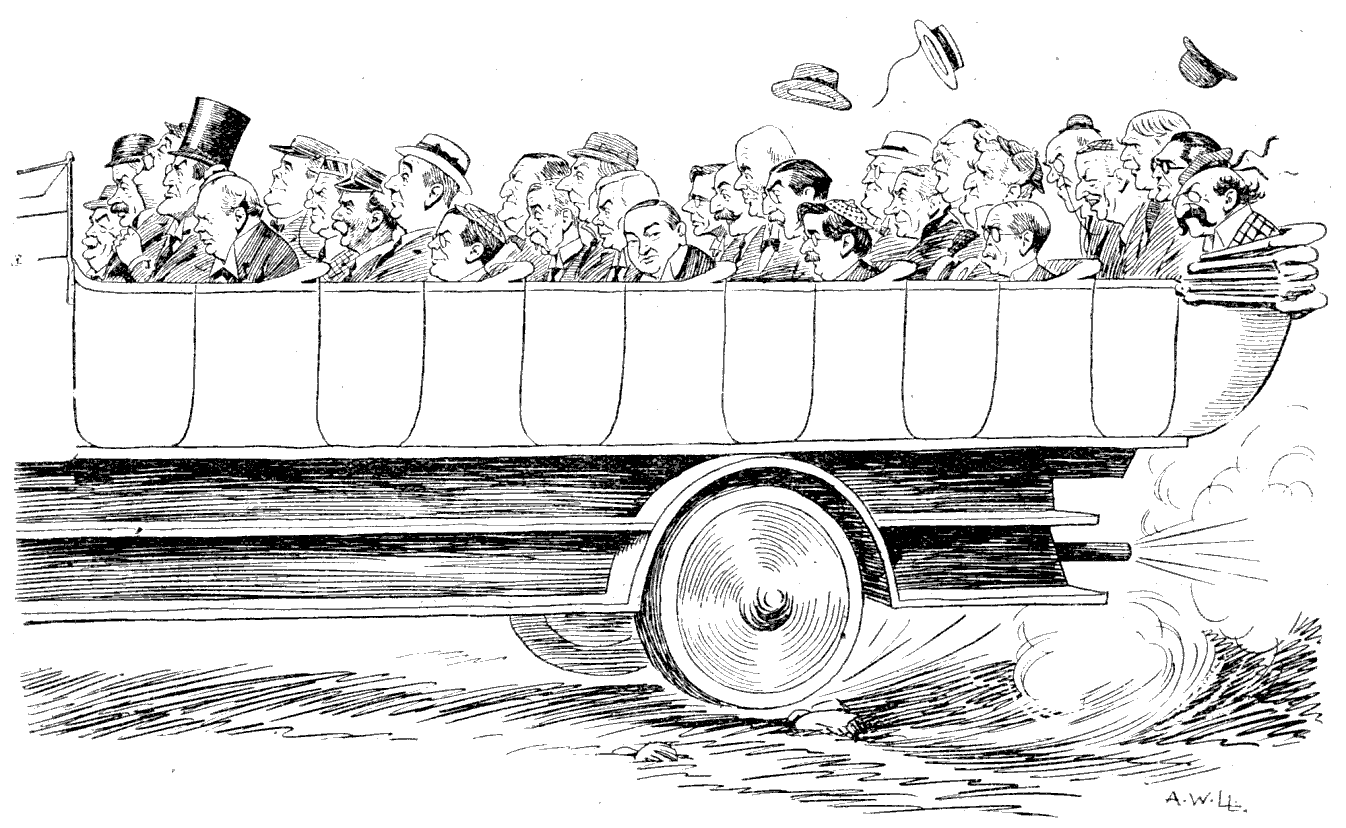

"I think it would be a calamity if we did anything to prevent the economic use of charabancs."—Sir Eric Geddes.

First "Banc." Mr. Lloyd George, Mr. Bonar Law, Mr. Balfour, Mr. Chamberlain, Mr. Churchill.

Second "Banc." Sir E. Geddes, Mr. Shortt, Mr. Long, Sir Robert Horne, Col. Amery.

Third "Banc." Mr. Illingworth, Lord E. Talbot, Mr. Fisher, Dr. Addison, Sir Gordon Hewart.

Fourth "Banc." Mr. Kellaway, Sir M. Barlow, Sir L. Worthington Evans, Sir A.G. Boscawen, Mr. Towyn Jones.

Fifth "Banc." Sir Hamar Greenwood, Mr. Baldwin, Sir James Craig, Mr. Denis Henry, Mr. Neal.

Sixth "Banc." Mr. Montagu, Dr. Macnamara, Mr. McCurdy, Mr. Ian Macpherson, Sir A. Mond.

Monday, August, 9th.—In an atmosphere of appropriate gloom the House of Lords discussed the latest Coercion Bill for Ireland. Even the Lord Chancellor could say little more for the measure than that it might possibly enable some of the persons now in custody to be tried; and most of the other Peers who spoke seemed to think that it would be either mischievous or useless. The only confident opinion expressed was that of the elderly Privy Councillor, who from the steps of the Throne ejaculated, "If you pass this Bill you may kill England, not Ireland." But despite this unconventional warning the Peers took the risk.

The event of the day in the House of Commons was Colonel Wedgwood's tie. Of ample dimensions and of an ultra-scarlet hue that even a London and South-Western Railway porter might envy, it dominated the proceedings throughout Question-time. Beside it Mr. Claude Lowther's pink shirt paled its ineffectual fires.

When Viscount Curzon renewed his anti-charabancs campaign and Sir Eric Geddes was doing his best to maintain an even mind amid the contradictory suggestions showered upon him, the Ministerial eye was caught by the red gleam from Colonel Wedgwood's shirt-front. At once, the old railway instinct reasserted itself. Recognizing the danger-signal and hastily cramming on his brakes, Sir Eric observed that it would be "a great calamity" to prevent the economic use of the charabancs.

Tuesday, August 10th.—As Lord Great Chamberlain, and therefore official custodian of the Palace of Westminster, Lord Lincolnshire mentioned with due solemnity the regrettable incident of the day before. Lord Curzon thought the offender (the Right Hon. A. Carlisle) should be allowed to explain his behaviour, and suggested that he should himself address to him a suitable letter. Several noble lords—anticipating, no doubt, that, whatever else came of it, the correspondence would furnish lively reading—said "Hear, hear."

A week ago the Peers decided by a very small majority—28 to 23—that there should be no Minister of Mines, but only an Under-Secretary. Lord Peel now sought to induce them to change their minds. His principal argument was that a Minister would only cost five hundred pounds a year more than a Secretary and would secure the "harmony in the coal-trade" now so conspicuously lacking. The Peers evidently thought this too good to be true, for they proceeded to reassert their previous decision by 48 to 23.

There was a big assemblage in the Commons to hear the Prime Minister's statement on Poland. The Duke of York was over the Clock, flanked by the Archbishop of Canterbury on one side and Messrs. Kameneff and Krassin (who sound, but do not look, like a music-hall "turn") on the other.

Some facts bearing, more or less, on the situation were revealed at Question-time. Mr. Churchill denied that he had ever suggested an alliance with the Germans against Bolshevism, and, as we are keeping the Watch on the Rhine [pg 134] with only thirteen thousand men—just three thousand more than it takes to garrison London—perhaps it is just as well. He has, I gathered, no great opinion of the Bolshevists as soldiers. In his endeavour to describe the disgust of our troops in North Russia at being ordered to retire before "an enemy they cordially despised" he nearly dislocated his upper lip.

For two-thirds of his speech the Prime Minister was the sober statesman, discussing with due solemnity the grave possibilities of the Russo-Polish crisis. The Poles had been rash and must take the consequences. We should not help them unless the Bolshevists, not content with punishment, threatened the extinction of Poland's independence.

Then his mood changed, and for a sparkling quarter of an hour he chaffed the Labour Party for its support of the Soviet Government, an unrepresentative self-appointed oligarchy. To make his point he even sacrificed a colleague. Lenin was an aristocrat, Trotsky a journalist. "In fact"—turning to Mr. Churchill—"my right honourable friend is an embodiment of both."

A brief struggle for precedence between Mr. Asquith and Mr. Adamson ended in favour of the ex-Premier, who doubted whether the best way to ensure peace was to attack one of the parties to the dispute, and proceeded to make things more or less even by vigorously chiding Poland for her aggression. Mr. Clynes, while admitting that the Labour Party would have to reconsider its position if the independence of Poland was threatened, still maintained that we had not played a straight game from Russia.

Later on, through the medium of Lieut.-Commander Kenworthy, communication was established between the Treasury Bench and the Distinguished Strangers' Gallery. Mr. Lloyd George read the terms offered by the Soviet to the Poles, and gave them a guarded approval.

Wednesday, August 11th.—A Bill to prohibit ready-money betting on football matches was introduced by Lord Gainford (who played for Cambridge forty years ago) and supported by Lord Meath, "a most enthusiastic player" of a still earlier epoch. The Peers could not resist the pleading of these experts and gave the Bill a second reading; but when Lord Gainford proposed to rush it through goal straightaway his course was barred by Lord Birkenhead, an efficient Lord "Keeper."

A proposal for the erection at the public expense of a statue of the late Mr. Joseph Chamberlain furnished occasion for the Prime Minister and Mr. Asquith to indulge in generous praise of a political opponent. Mr. Lloyd George (with his eye on the Sovietists) pointed out that, as this was "essentially a Parliamentary country," we did well to honour "a great Parliamentarian"; and the ex-Premier (with his eye on Mr. Lloyd George) selected for special note among Mr. Chamberlain's characteristics that he had "no blurred edges."

A humdrum debate on the Consolidation Fund Bill was interrupted by the startling news that France had decided, in direct opposition to the policy announced yesterday by the Prime Minister, to give immediate recognition to General Wrangel. Mr. Lloyd George expressed his "surprise and anxiety" and could only suppose that there had been an unfortunate misunderstanding. To give time for its removal the House decided to postpone its holiday and adjourned till Monday.

Messrs. Kameneff and Krassin, the Soviet envoys, were in the Distinguished Strangers' Gallery during the Prime Minister's speech on Poland last week. Hence these tears:—

"In conversation they seem to betray only a limited acquaintance with English, but every word of Mr. Lloyd George's utterance seemed intelligible to them. Not only did they follow him with eager interest, but often with animated comment."—Evening Standard.

"The two did not exchange a single remark during the whole of the Premier's speech." Evening News.

"Krassin could follow every word of Lloyd George. His colleague doesn't speak or understand English, so Krassin every few minutes leaned over and whispered a translation into the other's ear."—Star.

"The Soviet envoys, especially M. Krassin, seemed somewhat restless, and appeared to take more interest in the scene than in the speech, but this I heard attributed to their difficulty in following the words of the Prime Minister."—Pall Mall Gazette.

229th ed., folio, 2 vols. (Sour and Taxwell, 85s.).

All persons interested in this entrancing subject will welcome the new edition of Mr. Blewitt's famous work. The book is one which should be found on every shelf throughout the country, and is undoubtedly, in its combination of erudition and artistic merit, one of the masterpieces of English literature. It has been well described by a more competent critic as one which "it is difficult to take up when once you have put it down," and in this judgment most readers will, we believe, concur.

It seems needless for us to say anything about so well-known a work, and to say anything new is, we believe, impossible. Mr. Blewitt is invariably happy in his choice of subject, and in this treatise on Real Property his sparkling wit, his light style and clearness of expression do ample justice to the perennial freshness of his subject. The reader is swiftly carried from situation to situation and thrill follows thrill with daring rapidity. The plot is of the simplest, but worked out with surprising skill, while the events are related with that vivid imagination which the subject demands. Who is there that does not feel a glow of exaltation and rejoice with the heir when he comes, upon reversion, into the property from which he has been so long excluded? Mr. Blewitt treats this incident with a sense of romance and picturesqueness of language reminiscent of the ballad of "The Lord of Lynn." In its facts the ballad bears a striking resemblance to those so graphically described by our author, but in point of execution lacks the true breath of poetic inspiration which pervades Mr. Blewitt's book.

Nor is his work wanting in pathos. There are few who will not sympathise with the hero when he discovers that the life-estate of the fair widow whom he adores with all the fierce yearnings of his passionate soul is subject to a collateral limitation to widowhood. Mr. Blewitt's silence on the disappointment which embittered his spirit and the doubts which tormented his mind is more eloquent than any soliloquy of Hamlet.

It is not however in description but in characterisation that Mr. Blewitt is pre-eminent. We know of nothing in works of this nature to equal the skilful psychological analysis, the sympathy of treatment and the fidelity to nature with which the author draws line by line the character of Q. The description of him as seised in fee simple is a touch of genius. We can remember nothing [pg 135] in the English language to compare with this unless it be that brilliant passage in which Mr. Blewitt sketches in a few lightning strokes the character of Richard Roe, a man at once pugnacious, overbearing, litigious and utterly regardless of truth and honesty.

The learned editors have rendered a great service to the cause of learning in publishing this new edition. The editing is very creditable to English scholarship. The additional matter is a new note on page 1069, in which the reader is referred to an article in a recent number of the Timbuctoo Law Review, which, in fairness to the editor (of Real Property), is not, of course, quoted here. The student will, we have no doubt, feel himself fully recompensed by this new matter for the price of the new volumes and the depreciation of the 228th edition.

Irascible Golfer. "Confound it! what is that infernal oil-engine or something that begins thumping whenever I am putting?"

Caddie. "I think it must be t'other gentleman's 'eart, Sir."

Residents in the area between the county town and —— are now able to do their shopping at either place with the maximum of inconvenience so far as travel is concerned."—Provincial Paper.

Just as in London.

[The Times in a recent article on events in the Film world announces the impending arrival in Europe of Miss Dorothy Gish, adding, however, that the visit is mainly undertaken for recreation.]

Let others discourse and descant

Upon Mannix the martyr archbish,

Me rather it pleases to chant

The arrival of Dorothy Gish.

Among the élite of the Screen

She holds an exalted posit.;

But in Europe she never has been

Hitherto, hasn't Dorothy Gish.

And it's well to consider aright

That she harbours the laudable wish

For a holiday, not for the light

Of the lime, does Miss Dorothy Gish.

None the less with the wildest surmise

Do I muse on the bountiful dish

Of sensation purveyed for the wise

And the foolish by Dorothy Gish.

* * * * *

Will you strengthen the hands of Lloyd George

Or frown on the poor Coalit.?

Will you force profiteers to disgorge,

Beneficent Dorothy Gish?

Do you hold by self-governing schools?

Do you think that headmasters should swish

Or adopt Montessorian rules,

Benevolent Dorothy Gish?

Will they give you an Oxford degree?

Will you learn to call marmalade "squish"?

Will Kenworthy ask you to tea

On the Terrace, great Dorothy Gish?

Do you favour the Russ or the Pole?

Will you visit the Servians at Nish?

Are you sound on the subject of coal?

Are you Pussyfoot, Dorothy Gish?

Are you going to be terribly mobbed

When attending the concerts of Krish?

Are your tresses luxuriant or "bobbed"?

Do tell us, kind Dorothy Gish!

Meanwhile we are moody and mad,

Like Saul the descendant of Kish,

Oh, arrive and make everyone glad,

Delectable Dorothy Gish!

"Wanted, Lady Clerk; one accustomed to milk ledgers preferred."—New Zealand Paper.

But how does one milk a ledger?

A South Indian Lovesong.

When the long trick's wearing over and a spell of leave comes due

The most'll go back to Blighty to see if their dreams are true;

There's some that'll make for the Athol glens and some for the Sussex downs,

There's some that'll cling to the country and some that'll turn to towns;

But I know what I'll do, and I'll do it right or wrong,

I'll just get back to the Blue Mountains, for that's where I belong.

Athol's a bonny country and Sussex is good to see,

But it's long since I left Blighty and I'm not what I used to be;

And May in Devon's a marvel and June on Tummel's fine,

And that may be most folk's fancy, but it somehow isn't mine;

For I know what I like, and the Land of Heart's Delight

For me is just on the Blue Mountains, for that's where I feel right.

So I'll pack my box and bedding in the old South Indian mail

And wake to a dawn in Salem ghostly and grey and pale,

And over by Avanashi and the levels of Coimbatore

I'll see them hung in the tinted sky and I won't ask for more;

For I'll know I'm happy and I'll make my morning prayer

Of thanks for the sun on the Blue Mountains and me to be going there.

The little mountain railway shall serve me for all I need,

Crawling its way to Adderly, crawling to Runnymede;

And the scent of the gums shall cheer me like the sight of a journey's end,

And the breeze shall say to me "Brother" and the hills shall hail me "Friend,"

While the clear Kateri River sings lovesongs in my ear,

And I'll feel "Now I'm home again! Ah! but I'm welcome here."

Clear in the opal sunset I shall see the Kundahs lie

And the sweep of the hills shall fill my heart as the roll of the Downs my eye;

And I'll see Snowdon and Staircase and the green of the Lovedale Wood,

And the dear sun shining on Ooty, and oh! but I'll find it good;

For I'll have what I wanted, and all the worrying done,

Because I'm back to the Blue Mountains and they and I are one.

There's peace beyond understanding, solace beyond desire

For minds that are over-weary, for bodies that toil and tire,

And over all that a something, a something that says, "You know,

It's the one place of all places where the gods meant you to go."

Well, the gods know what they know, and I wouldn't say them nay,

And Blighty of course is Blighty, but it's terribly far away,

So I'll get back to the Blue Mountains, and the betting is, I'll stay.

H.B.

"E.H. —— bawled consistently for the visitors, taking seven wickets of 168."—Welsh Paper.

As a sufferer from the prevailing complaint, house-famine, I have started a Correspondence Bureau, ostensibly for advising parents as to the pursuits their offspring should take up, but really for propaganda purposes, the object being the assuagement of this terrible evil.

Consequently my replies to inquiries are all moulded to this end.

For instance, one mother wrote from Surbiton:—

"My second son, Algernon, wishes to become a house and estate agent. Do please tell me if you think this quite a fitting avocation for one whose father is a member of the Stock Exchange."

I replied, "Quite. There is no nobler, and incidentally there are few more lucrative occupations outside Bradford, unless it be that of a builder, in which the scope is absolutely unlimited. I am enclosing a copy of last week's Builder and Architect, in which you will find some great thoughts expressed. Pray let Algernon read it. It may be the means of inducing him to perform great deeds for England's sake."

Another fond parent wrote:—

"Can you advise an anxious mother as to a career for her only son, John William? He is at present eight and a-half years old, has blue eyes and fair hair and is a perfect darling, so good and obedient, but he is firmly resolved to be a lift-man when he grows up."

I answered her soothingly thus:—

"John Willie is rather young to have made a final decision, I think. Let his youthful aspirations run through the usual stages, liftman, engine-driver, bus-conductor, sailor, etc. At fifteen or so he will have left these behind, and for the next few years will probably settle down to the idea of being nothing in particular, or else a professional cricketer. Then he will suddenly, for good or evil, make his choice. Neither his blue eyes nor his fair hair give any clue as to what that choice will be, but I should let him keep both, as they may be useful to him.

"If he should determine upon a career involving manual work, I should take steps to have him initiated into the Art and Mystery of Bricklaying. At the rate we are moving the working-hours would probably be about eight per week, with approximately eight pounds per day salary, by the time he arrives at bricklaying maturity.

"It is difficult to say yet whether he would have to graduate in Commerce before being eligible, but probably it would be necessary, as the best bricklayers, I'm told, always carry a mortar-board, and there is a sort of caucus in these plummy professions nowadays that is anxious to keep outsiders from joining their ranks. But the country needs bricklayers, and will go on needing them for years. Let John Willie step forward when he is old enough."

To the mother who asked if I considered that her youngest boy would be well advised to adopt the Housebreaking profession I wrote:—

"To which part of this profession do you refer? If to the Burgling branch I would ask, 'Has he the iron nerve, the indomitable will, above all has he the brain power for this exacting craft? Can he stand the exposure to the night air, the exposure before an Assize jury, and the rigours of the Portland stone quarries?' If so, let him take a course of illustrated lectures at the cinema.

"If you refer to the other branch, the mere pulling down of houses, I say, 'No! A thousand times, no!' He should be taught that there is a crying need for a constructive, [pg 137] not a destructive policy. Let him adopt one; buy him drawing-paper and a tee-square at once, and teach him that the noblest work of creation is (unless it be a bricklayer or builder) an architect. Though the War is over we must still keep the home fires burning. This implies chimneys, and chimneys imply houses, and few there be that can plan houses that will both please the eye and pass the local authorities."

Lady Jubb wrote from Toffley Hall, Blankshire, to say that her elder son (seventeen) had no ideas for the future beyond becoming Master of the Barchester when he grew up, but that she was anxious that he should try for some more lucrative post, official preferred.

I replied thus:—

"So your son looks no higher than a Mastership of Foxhounds. Well, well, I suppose that so long as there are such things as hounds he, as well as another, may take on the job of Master.

"But I thoroughly approve of your desire that he should try for something higher in life, especially for some official post; and what official post is or can be superior to that of a Borough Surveyor? Can you not persuade him that this great office is what one chooses to make it, and that, as an autocrat, the M.F.H. is hardly to be compared to the B.S., for, whereas the former can at the most scorch the few people foolish enough to remain within ear-shot, the latter can with a breath damn a whole row of houses and blast the careers of an army of builders with a word."

And so the propaganda proceeds.

If my efforts result in even one house being erected I shall, I think, have earned my O.B.E., though I would rather have the house.

My Lady Bountiful. "So your mother is better through taking the quinine I gave her?"

Little Girl (doing her best to carry out instructions). "Yes'm. But she says she's worse of the complaint wot you gives 'er port wine for."

Oh, civil life is fine and free, with no one to obey,

No sergeants shouting, "Show a leg!" or "Double up!" all day;

No buttons to be polished, no army boots to wear,

And nobody to tick you off because you grow your hair.

It's great to sleep beneath a roof that keeps the rain outside,

To eat a daintier kind of grub than quarter-blokes provide,

To rise o' mornings when you wish and when you wish turn in,

To shirk a shave and never hear the truth about your chin;

And not to have to pad the hoof through blazing sun or rain,

Intent on getting nowhere and foot-slogging back again,

To realise no N.C.O. has any more the right

To rob you of your beauty-sleep with "Guard to-morrow night!"

All this is great, of course it is, yet here we are once more

Obeying sergeants just for fun and cheerier than before;

We haven't any good excuse, we've got no war to win—

But nothing's touched the kit-bag yet for packing troubles in.

W.K.H.

I have often wished I were an expert at something. How I envy the man who, before ordering a suit of clothes from his tailor, seizes the proffered sample of cloth and tugs at it in a knowledgable manner, smells it at close quarters with deep inhalations and finally, if he is very brave, pulls out a thread and ignites it with a match. Whereupon the tailor, abashed and discomfited, produces for the lucky expert from the interior of his premises that choice bale of pre-war quality which he was keeping for his own use.

I confided this yearning of mine to Rottenbury the other evening. Rottenbury is a man of the world and might, I thought, be able to help me.

"My dear fellow," he said, "in these days of specialisation one has to be brought up in the business to be an expert in anything, whether cloth or canaries or bathroom tiling. Knowledge of this kind is not gained in a moment."

"Can you help me?" I asked.

"As regards tea, I can," he replied. "Jorkins over there is in the tea business. If you like I'll get him to put you up to the tricks of tea-tasting."

"I should be awfully glad if you would," said I. "We never get any decent tea at home."

Jorkins appeared to be a man of direct and efficient character. I saw Rottenbury speak to him and the next moment he was at my elbow.

"Watch me carefully," said Jorkins, "and listen to what I say. Take a little leaf into the palm of your left hand. Rub it lightly with the fingers and gaze earnestly thus. Apply your nose and snuff up strongly. Pick out a strand and bite through the leaf slowly with the front teeth, thus. Just after biting pass the tip of the tongue behind the front teeth and along the palate, completing the act of deglutition. Sorry I must go now. Good day."

Now I felt I was on the right track. I practised the thing a few times before a glass, paying special attention to the far-away poetical look which Jorkins wore during the operation.

At the tea-shop the man behind the counter willingly showed me numbers of teas. I snatched a handful of that which he specially recommended and began the ceremony. I took a little into the palm of my left-hand and gazed at it earnestly; I rubbed it lightly with my fingers; I picked up a strand and bit through the leaf slowly with the front teeth. Just after biting I passed the tongue behind the front teeth and along the palate, completing the act of deglutition.

So far as I could judge it was very good tea, but it would never do to accept the first sample offered; I must let the shopman see that he was up against one of the mandarins of the trade. So I said with severity, "Please don't show me any more common stuff; I want the best you have."

The man looked at me curiously and I saw his face twitching; he was evidently about to speak.

"Kindly refrain from expostulating," I went on; "content yourself with showing me your finest blend."

He went away to the back of the shop, muttering; clearly he recognised defeat, for when he returned he carried a small chest.

"Try this," said he, and I knew that he was boiling with baffled rage.

I took a handful and once more went through the whole ceremony. It was nauseating, but the man was obviously impressed. At the conclusion of my performance I assumed a look of satisfaction. "Give me five pounds of that," said I with the air of a conqueror.

Next time I met Rottenbury I told him of my success.

"Oh, Jorkins put you up to the trick, did he?"

"He did. He taught me to titillate, to triturate, to masticate, to deglute—everything."

"And with what result?"

"With the result that I have in my possession five pounds of the finest tea that the greatest experts have blended from the combined products of Assam and China."

"Tea?" he asked.

"Yes, tea of course. You didn't suppose that I was talking of oysters?"

"Did I tell you Jorkins was a tea-taster?"

"Yes."

"Well, then, he's not. He's in tobacco."

"Alured," said my wife, "I wish you wouldn't buy things for the house. That tea is low-grade sweepings."

LE GRAND PENSEUR.

(With apologies to the late Auguste Rodin.)

Advertising enthusiast on his holiday seeking inspiration for a new advertisement for the Underground Railway.

"Sir Otto Beit has returned to London from South Africa, where he turned the first sot of the new university."—Daily Paper.

Turned him out, we trust.

"In a brilliant peroration the Prime Minister warned his hearers that a nation was known by its soul and not by its asses."—South African Paper.

Yet some of our politicians seem to think that England is not past braying for.

"The doings (or rather sayings!) in the Legislature we are watching with sympathy and some impatience, much as a bachelor bears with the gambling of children who come to the drawing-room for an hour before dinner."—Weekly Paper.

And the worst of it is that the Legislature is gambling with our money.

"Miss ——, director of natural science studies at Newnham College, Oxford, will preside."—Daily Paper.

We are glad to hear of this new women's college at Oxford, but surely they might have chosen a more original name for it.

A.G.J. writes: "Your picture of 'Come unto these Yellow Sands' in the number for August 4th explains for the first time the obscure following line, 'The Wild Waves Whist.'"

"I have not seen you at church for two Sundays, John."

"No, Sir. No offence t'you, but oi a-bin doin' t' chapel passon's garden, so missus thought we'd better give 'im a turn."

(By Mr. Punch's Staff of Learned Clerks.)

To review one of Mr. E.F. Benson's social satires always gives me somewhat the sensations of the reporter at the special sermon—a relieved consciousness that, being present on business, my own withers may be supposed professionally unwrung. Otherwise, so exploratory a lash.... I seldom recall the touch of it more shrewd than in Queen Lucia (Hutchinson), an altogether delightful castigation of those persons whom a false rusticity causes to change a good village into the sham-bucolic home of crazes, fads and affectation. All this super-cultured life of the Riseholme community has its centre in Mrs. Lucas, the acknowledged queen of the place (Lucia = wife of Lucas, which shows you the character of her empire in a single touch); the matter of the tale is to tell how her autocracy was threatened, tottered and recovered. I wish I had space to quote the description of the Lucas home, "converted" from two genuine cottages, to which had been added a wing at right-angles, even more Elizabethan than the original, and a yew-hedge, "brought entire from a neighbouring farm and transplanted with solid lumps of earth and indignant snails around its roots." Perhaps, apart from the joy of the setting, you may find some of the incidents, the faith-healer, the medium and so on, a trifle obvious for Mr. Benson. More worthy of him is the central episode—the arrival as a Riseholme resident of Olga Bracely, the operatic star of international fame. Her talk, her attitude towards the place, and the subtle contrast suggested by her between the genuine and the pretence, show Mr. Benson at his light-comedy best. In short, a charming entertainment, in speaking of which you will observe I have not once so much as mentioned the word "Cotswolds."

Michael Forth (Constable) will doubtless convey a wonderful message to those of us who are clever enough to grasp its meaning; but I fear that it will be a disappointment to many admirers of Miss Mary Johnston's earlier books. Frankly I confess myself bewildered and unable to follow this excursion into the region of metaphysics; indeed I felt as if I had fallen into the hands of a guide whose language I could only dimly and dully understand. All of which may be almost entirely my fault, so I suggest that you should sample Michael for yourselves and see what you can make of him. Miss Johnston shouldered an unnecessarily heavy burden when she decided to tell the story of her hero in the first person, but in relating Michael's childhood in his Virginian home she is at her simplest and best. Afterwards, when Michael became intent on going "deeper and deeper within," he succeeded so well that he concealed himself from me.

Because I have a warm regard for good short stories and heartily approve the growing fashion of publishing or republishing them in volume form, I am the more jealous that the good repute of this practice should be preserved from damage by association with unworthy material. I'm afraid this is a somewhat ominous introduction to a notice of The Eve of Pascua (Heinemann), in which, to be brutally frank, I found little justification for even such longevity as modern paper conditions permit. "Richard Dehan" is admittedly a writer who has deserved well of the public, but none of the tales in this collection will do [pg 140] anything to add to the debt. The best is perhaps a very short and quite happily told little jest called "An Impression," about the emotions of a peasant model on seeing herself as interpreted by an Impressionist painter. There is also a sufficiently picturesque piece of Wardour Street medievalism in "The Tribute of the Kiss," and some original scenery in "The Mother of Turquoise." But beyond this (though I searched diligently) nothing; indeed worse, since more than one of the remaining tales, notably "Wanted, a King" and "The End of the Cotillion," are so preposterous that their inclusion here can only be attributed to the most cynical indifference.

It may be my Saxon prejudice, but, though most of the ingredients of Irish Stew (Skeffington) are in fact Irish, and though Mrs. Dorothea Conyers is best known as a novelist who delights in traditional Ireland and traditional horses, I am bound to confess that I enjoyed the adventures of Mr. Jones, trusted employé of Mosenthals and Co., better than Mrs. Conyers' stage Irishmen. "Our Mr. Jones" is neither a Sherlock Holmes nor an Aristide Pujol, neither a Father Brown nor a Bob Pretty, but nevertheless he is an engaging soul and we could do with more of him. Mrs. Conyers' hunting clientèle may much prefer to read about the dishonesties of Con Cassidy and his fellow-horse-copers and the simple but heroic O'Toole and his supernatural friends. But, as the average Irish hunting man cares little more for books than he does for bill-collectors, his preference may not be of paramount importance. In any case the Irish ingredients of Irish Stew would be easier to assimilate if Mrs. Conyers would refrain from trying to spell English as the Irish speak it. If the reader knows Ireland it is unnecessary and merely makes reading a task. If the reader does not know Ireland no amount of phonetic spelling will reproduce a single one of the multitudinous brogues that fill Erin with sound and empty it of sense. On the whole Mrs. Conyers' public will not be disappointed with her latest sheaf of tales. But it is Mr. Jones who will give them their money's worth.

I was, I confess, a little sceptical—you know how it is—when I read what Messrs. Hodder and Stoughton's official reviewer said of Mr. Hal. G. Evarts' The Cross-Pull: "The best dog story since The Call of the Wild," etc., etc. Well, I certainly haven't seen a better. Mr. Evarts' hero, Flash, is a noble beast of mixed strain—grey wolf, coyote, dog. The Cross-Pull is the conflict between the dog and the wolf, between loyalty to his master and mistress whom he brings together and serves, and the wolf whose proper business is to be biting elks in the neck. Happier than most tamed brutes he is involved as chief actor in a round up of some desperate outlaws, among whom is his chief enemy, and he is fortunate enough to serve the state while pursuing to a successful end his bitter private quarrel. Brute Brent gets and deserves the kind of bite which was planned by a far-seeing providence for the elk.... You can tell when an author really loves and knows animals or is merely "putting it on." Mr. Evarts understands, sentimentalises less than most interpreters; seems to know a good deal. The story loses no interest from being set in the American hinterland of a few decades ago. All real animal lovers should get this book—they should really.

If it be true art, as I rather think someone has said it is, to state what is obvious in regard to a subject while creating by the manner of the statement an impression of its subtler features, then Mr. Percy Brown, in writing Germany in Dissolution (Melrose), has proved himself a true artist. For in Germany about the time of the Armistice and during the Spartacist rising certain things happened which got themselves safely into the newspapers, and these he sets forth, mostly in headline form. Beyond this Germany was a seething muddle of contradictions and cross-purposes, which, it is hardly unfair to say, are capably reflected in his pages. Mr. Brown is a journalist of the school that does not stick at a trifle, a German prison, for instance, when his dear public wants news. His crowning achievement was to persuade Dr. Solf, when Foreign Minister, to send through the official wireless an account of an interview with himself, which would, as he (Solf) fondly hoped, help to bamboozle British public opinion. When the article appeared, so well had the author's editor read between the lines of the message that the journalist had to run for his life. He was particularly fortunate too, or clever, in getting in touch with the Kiel sailors who set the revolution going, but in spite of much excellent material, mostly of the "scoop" interview variety, nothing much ever seems to come of it all, and we are left at the end about as wise as we started. All the same, much of the book's detail is interesting, however little satisfaction it offers as a whole.

Ann's First Flutter (Allen and Unwin) will not arouse any commotion in the dovecotes of the intellectually elect, but it provides an amusing entertainment for those who can appreciate broad and emphatic humour. Mr. R.A. Hamblin has succeeded in what he set out to do, and my only quarrel with him is that I believe him to have a subtler sense of humour than he reveals here. Ann was a grocer's daughter, and after her attempt to flutter for herself had failed she married Tom Bampfield, a grocer's son. Tom had literary ambitions, and was the author of a novel which his father thought pernicious enough to destroy his custom. Strange however to relate, the novel failed to destroy anything except the author's future as a novelist, and when Tom did succeed in making some pen-money it was by means of a series of funny articles in The Dry Goods Gazette—articles so violently humorous that the author's father thoroughly appreciated them. Mr. Hamblin's fun, let me add, is never ill-natured. Even bilious grocers will not resent his jovial invasion of their kingdom.

"City gunsmiths have been busy these days furbishing up sportsmen's rifles for the '12th.'"—Scotch Paper.

Personally we use a machine-gun.

End of the Project Gutenberg EBook of Punch, or the London Charivari, Vol.

159, August 18th, 1920, by Various

*** END OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK PUNCH ***

***** This file should be named 16707-h.htm or 16707-h.zip *****

This and all associated files of various formats will be found in:

http://www.gutenberg.org/1/6/7/0/16707/

Produced by Jonathan Ingram, Keith Edkins and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

Updated editions will replace the previous one--the old editions

will be renamed.

Creating the works from public domain print editions means that no

one owns a United States copyright in these works, so the Foundation

(and you!) can copy and distribute it in the United States without

permission and without paying copyright royalties. Special rules,

set forth in the General Terms of Use part of this license, apply to

copying and distributing Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works to

protect the PROJECT GUTENBERG-tm concept and trademark. Project

Gutenberg is a registered trademark, and may not be used if you

charge for the eBooks, unless you receive specific permission. If you

do not charge anything for copies of this eBook, complying with the

rules is very easy. You may use this eBook for nearly any purpose

such as creation of derivative works, reports, performances and

research. They may be modified and printed and given away--you may do

practically ANYTHING with public domain eBooks. Redistribution is

subject to the trademark license, especially commercial

redistribution.

*** START: FULL LICENSE ***

THE FULL PROJECT GUTENBERG LICENSE

PLEASE READ THIS BEFORE YOU DISTRIBUTE OR USE THIS WORK

To protect the Project Gutenberg-tm mission of promoting the free

distribution of electronic works, by using or distributing this work

(or any other work associated in any way with the phrase "Project

Gutenberg"), you agree to comply with all the terms of the Full Project

Gutenberg-tm License (available with this file or online at

http://gutenberg.net/license).

Section 1. General Terms of Use and Redistributing Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic works

1.A. By reading or using any part of this Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic work, you indicate that you have read, understand, agree to

and accept all the terms of this license and intellectual property

(trademark/copyright) agreement. If you do not agree to abide by all