The Project Gutenberg EBook of History Of Egypt, Chaldęa, Syria, Babylonia, and Assyria, Volume 5 (of 12), by G. Maspero This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net Title: History Of Egypt, Chaldęa, Syria, Babylonia, and Assyria, Volume 5 (of 12) Author: G. Maspero Editor: A.H. Sayce Translator: M.L. McClure Release Date: December 16, 2005 [EBook #17325] Last Updated: September 7, 2016 Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK HISTORY OF EGYPT, CHALDĘA *** Produced by David Widger

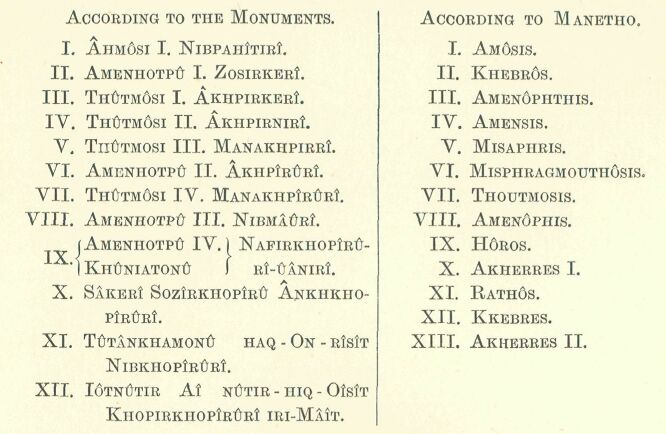

THŪTMOSIS III.: THE ORGANISATION OF THE SYRIAN PROVINCES—AMENŌTHES III.: THE WORSHIPPERS OF ATONŪ.

Thutmosis III.: the talcing of Qodshā in the 42nd year of his reign—The tribute of the south—The triumph-song of Amon.

The constitution of the Egyptian empire—The Grown vassals and their relations with the Pharaoh—The king’s messengers—The allied states—Royal presents and marriages; the status of foreigners in the royal harem—Commerce with Asia, its resources and its risks; protection granted to the national industries, and treaties of extradition.

Amenōthes II, his campaigns in Syria and Nubia—Thūtmosis IV.; his dream under the shadow of the Sphinx and his marriage—Amenōthes III. and his peaceful reign—The great building works—The temples of Nubia: Soleb and his sanctuary built by Amenōthes III, Gebel Barkal, Elephantine—The beautifying of Thebes: the temple of Mat, the temples of Amon at Luxor and at Karnak, the tomb of Amenōthes III, the chapel and the colossi of Memnon.

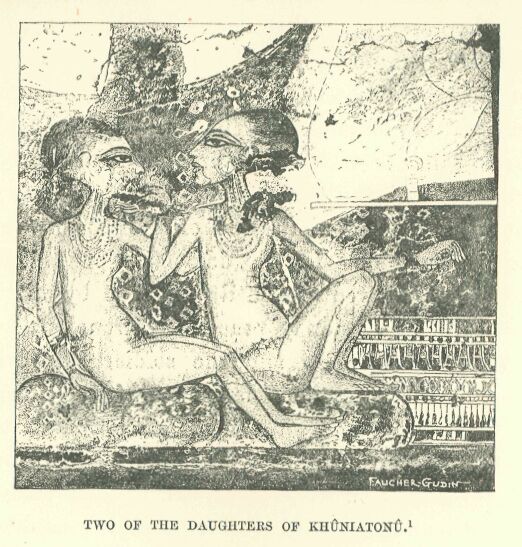

The increasing importance of Anion and his priests: preference shown by Amenōthes III. for the Heliopolitan gods, his marriage with Tii—The influence of Tii over Amenōthes IV.: the decadence of Amon and of Thebes, Atonū and Khūītniatonū—Change of physiognomy in Khūniaton, his character, his government, his relations with Asia: the tombs of Tel el-Amarna and the art of the period—Tutanlchamon, At: the return of the Pharaohs to Thebes and the close of the XVIIIth dynasty.

CONTENTS

CHAPTER I—THE EIGHTEENTH THEBAN DYNASTY—(continued)

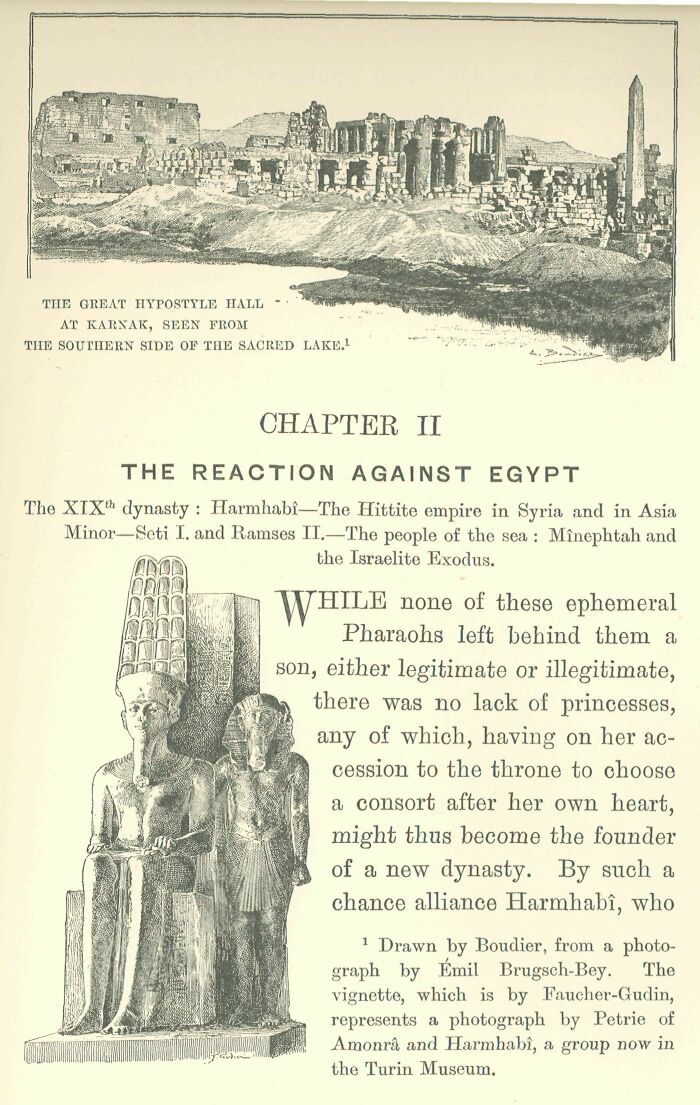

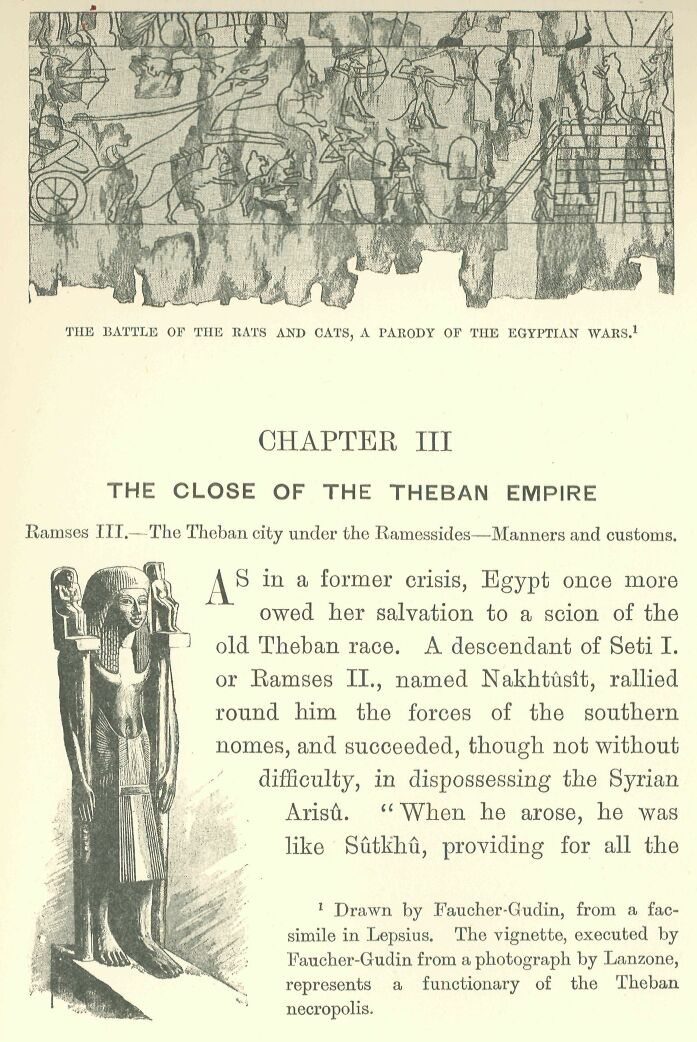

CHAPTER II—THE REACTION AGAINST EGYPT

CHAPTER III—THE CLOSE OF THE THEBAN EMPIRE

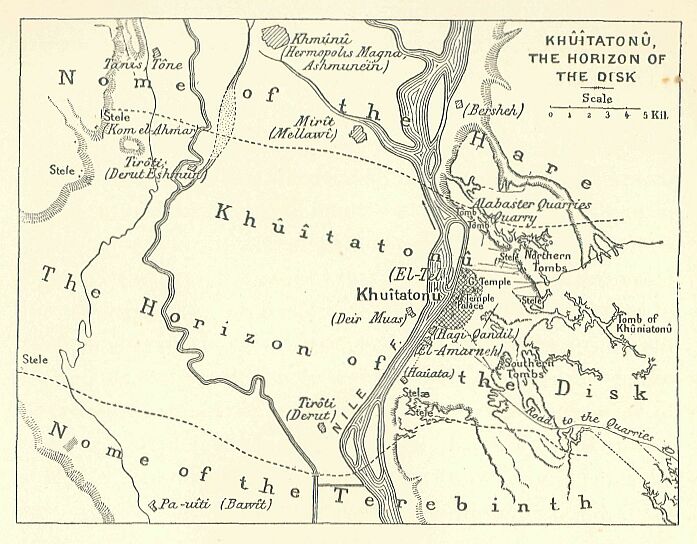

List of Illustrations

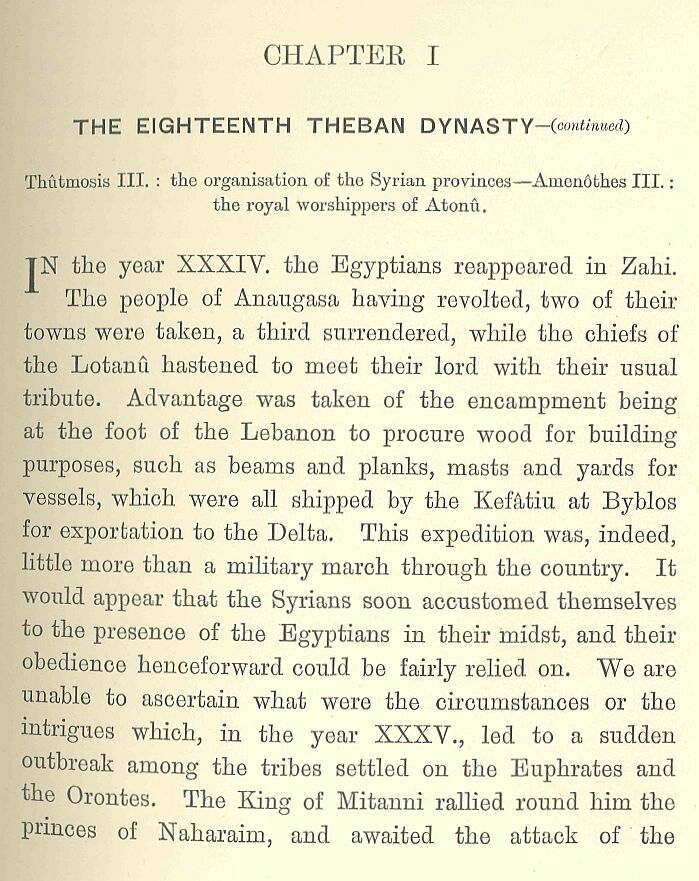

006.jpg a Procession of Negroes

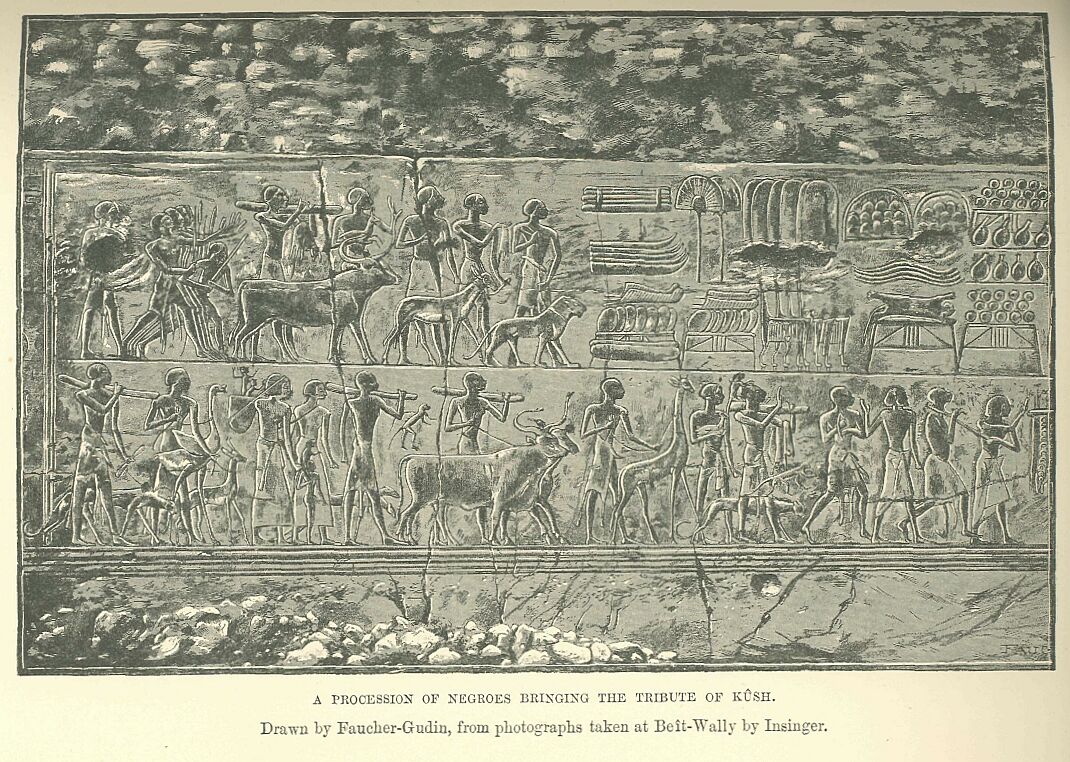

015.jpg a Syrian Town and Its Outskirts After an Egyptian Army Had Passed Through It

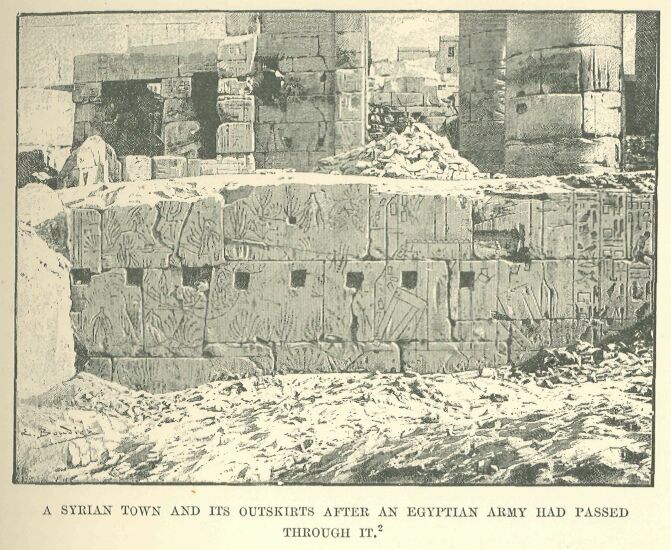

030.jpg the LotanŪ and The Goldsmiths’work Constituting Their Tribute

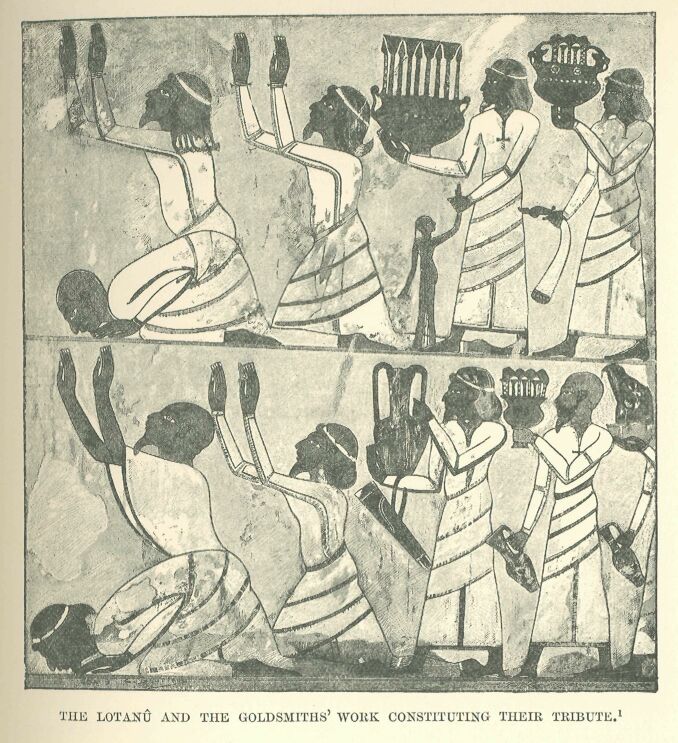

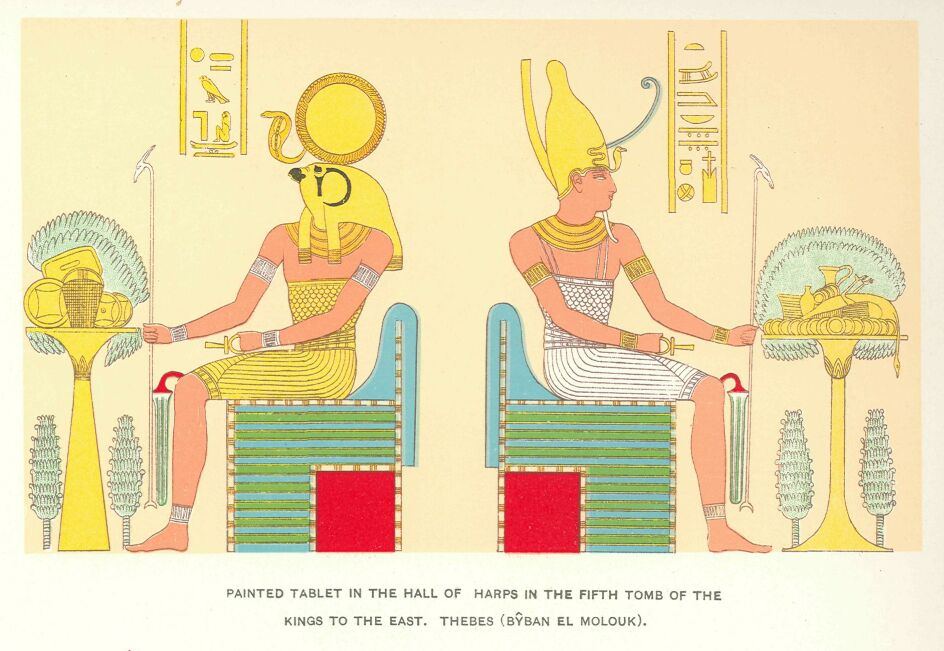

032b.jpg Painted Tablets in the Hall of Harps

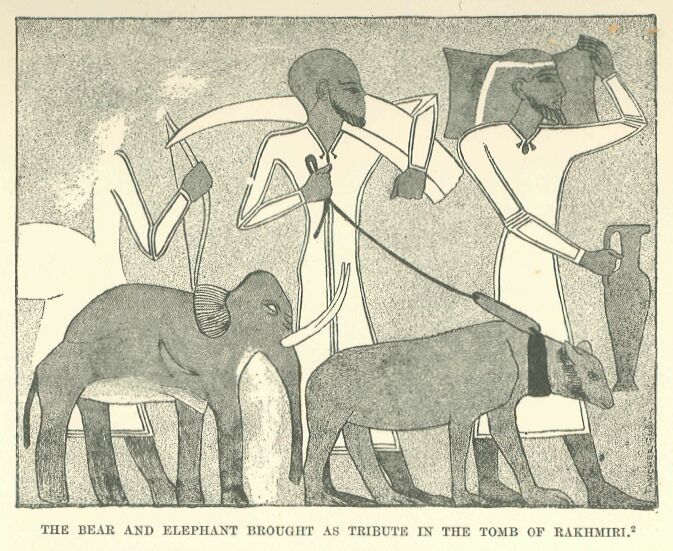

034.jpg. The Bear and Elephant Brought As Tribute in The Tomb of Rakhmiri

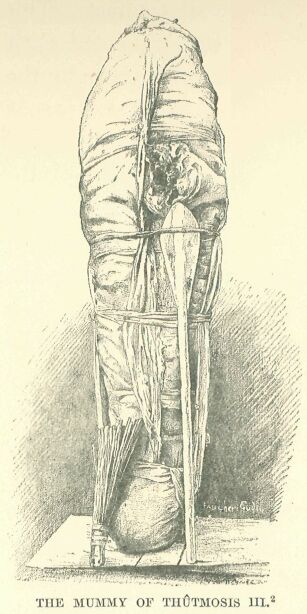

040.jpg the Mummy of Thutmosis Iii.

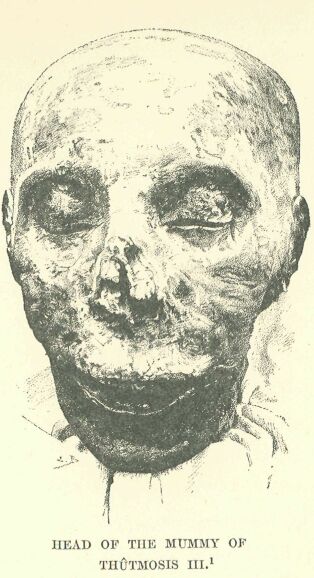

041.jpg Head of the Mummy Of ThŪtmosis Iii.

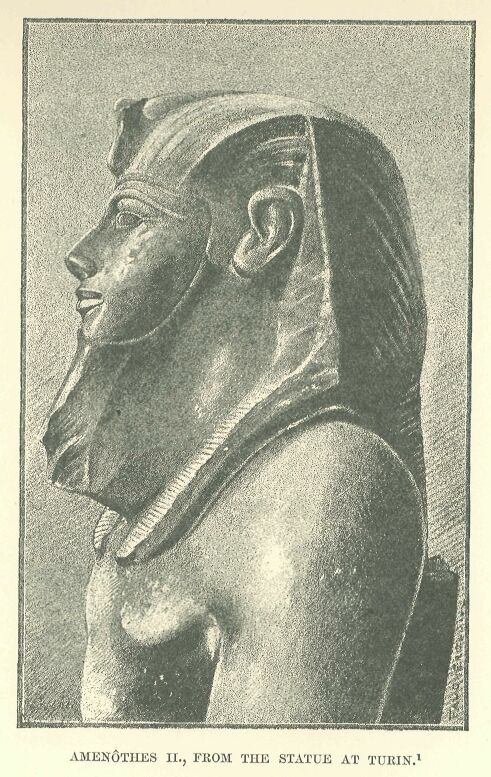

044.jpg AmenŌthes Ii., from the Statue at Turin

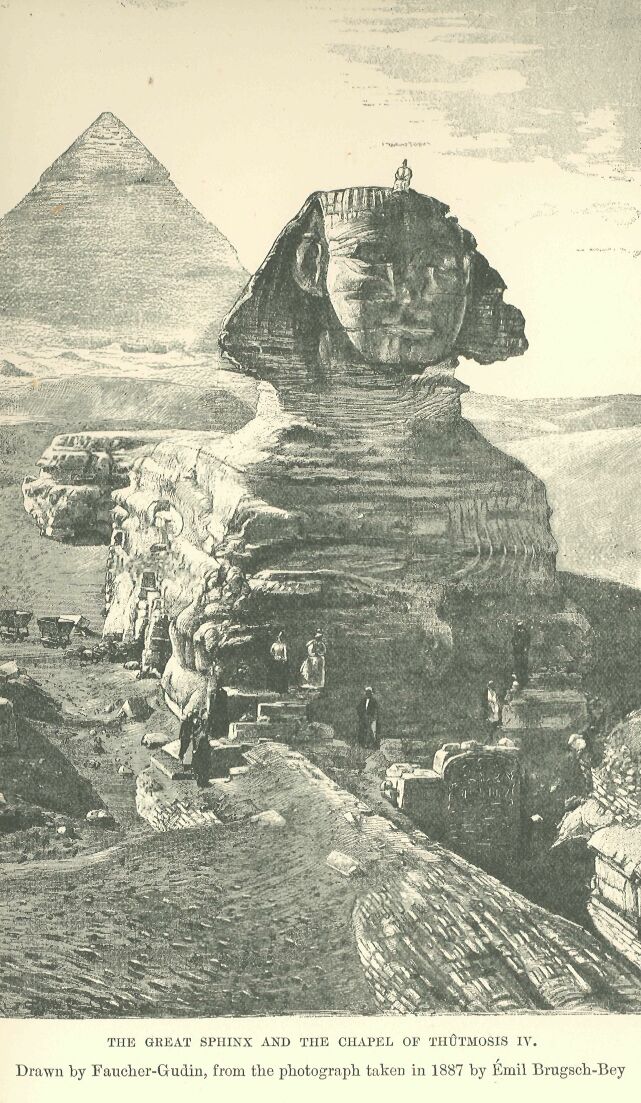

046.jpg the Great Sphinx and The Chapel of Thutmosis Iv.

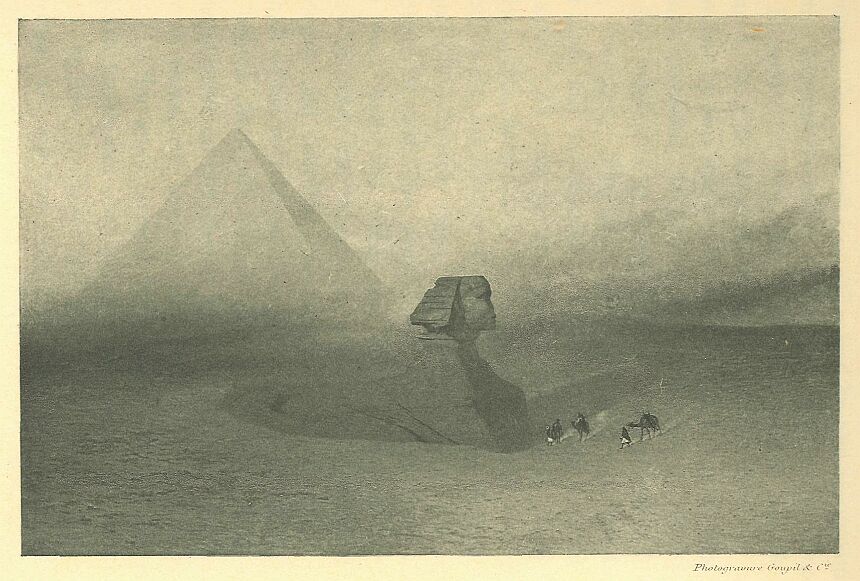

047.jpg the Simoom. Sphinx and Pyramids at Gizeh

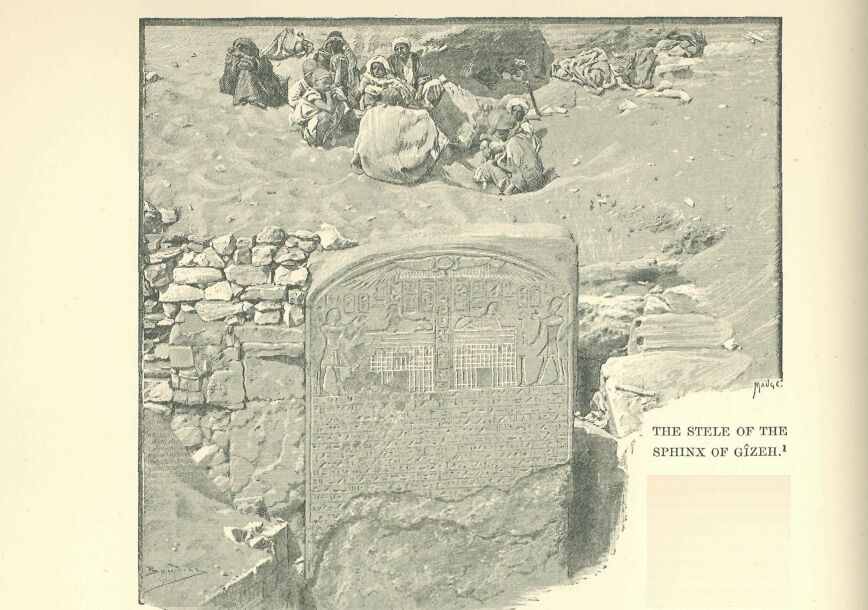

050.jpg the Stele of The Sphinx Of Gizer

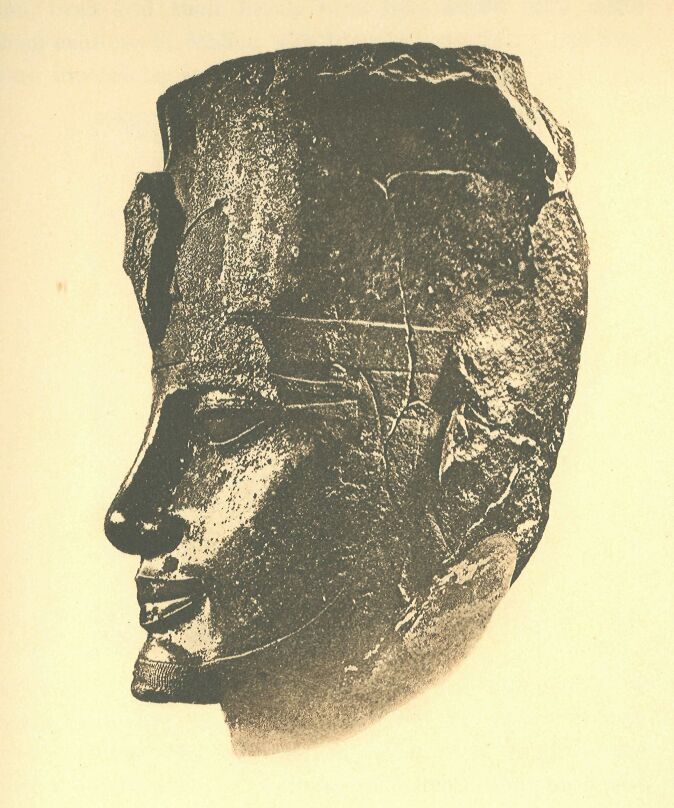

052b.jpg Amenothes Iii. Colossal Head in the British Museum

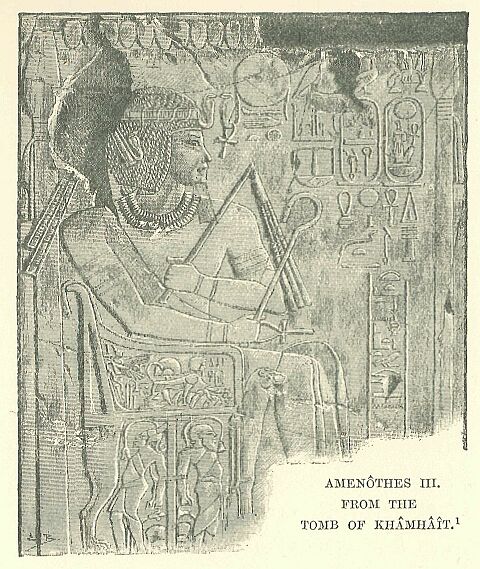

053.jpg Amenothes Iii. From the Tomb of Khamhait

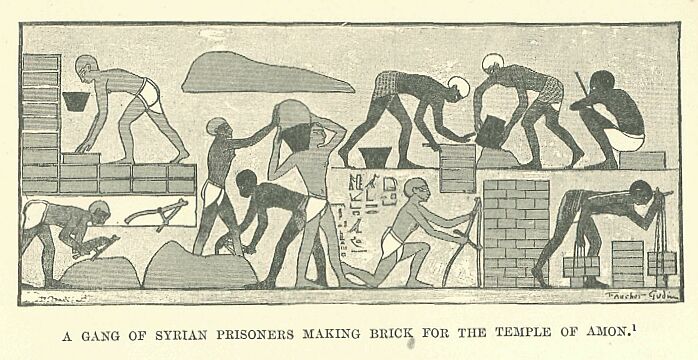

058.jpg a Gang of Syrian Prisoners Making Brick for The Temple of Amon

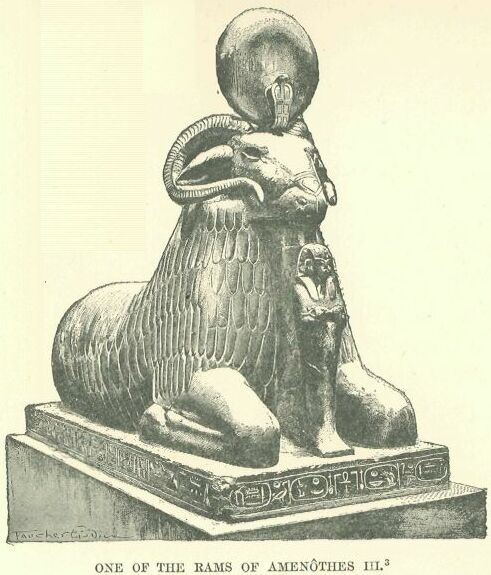

059.jpg One of the Rams Of AmenŌthes Iii

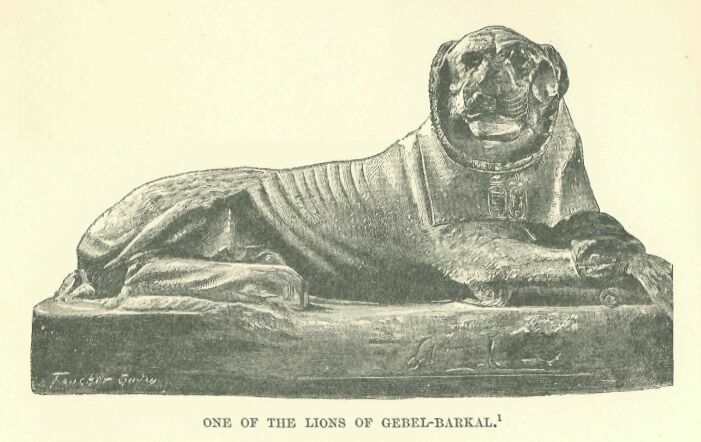

062.jpg One of the Lions Of Gebel-barkal

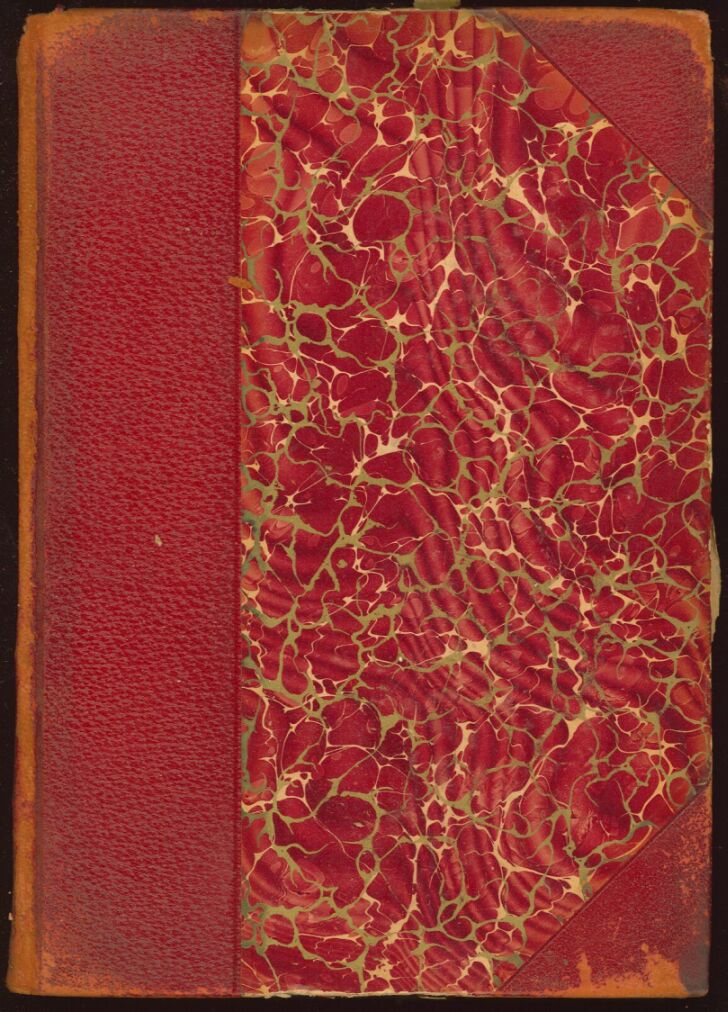

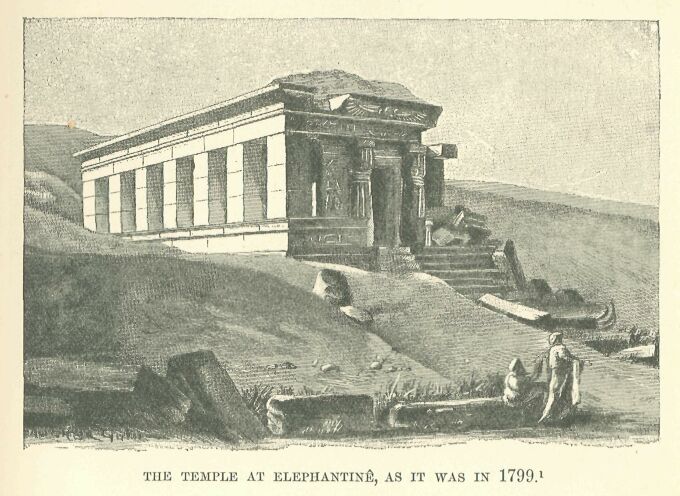

065.jpg the Temple at Elephantine, As It Was in 1799

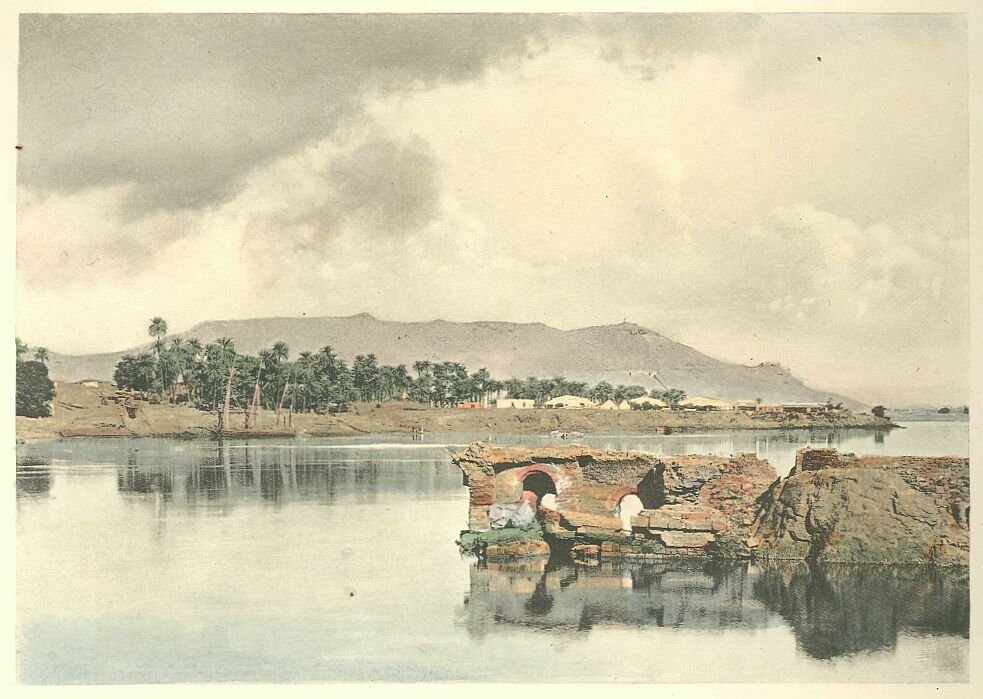

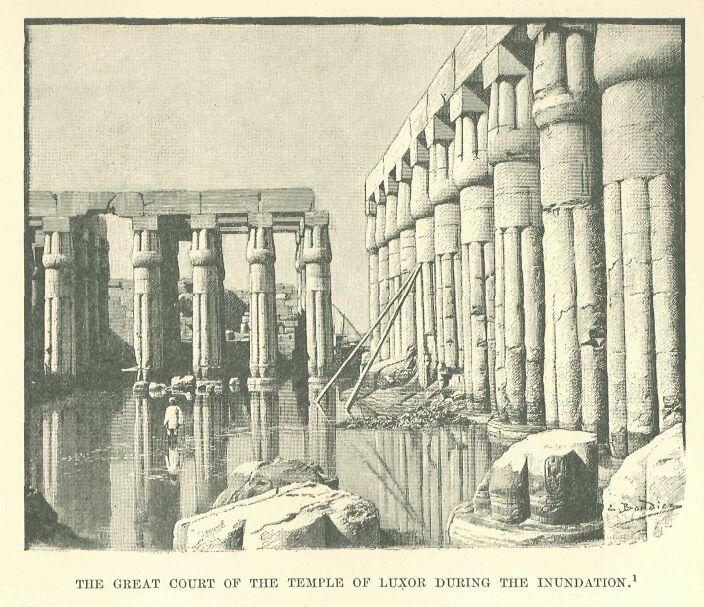

066.jpg the Great Court of The Temple Of Luxor During The Inundation

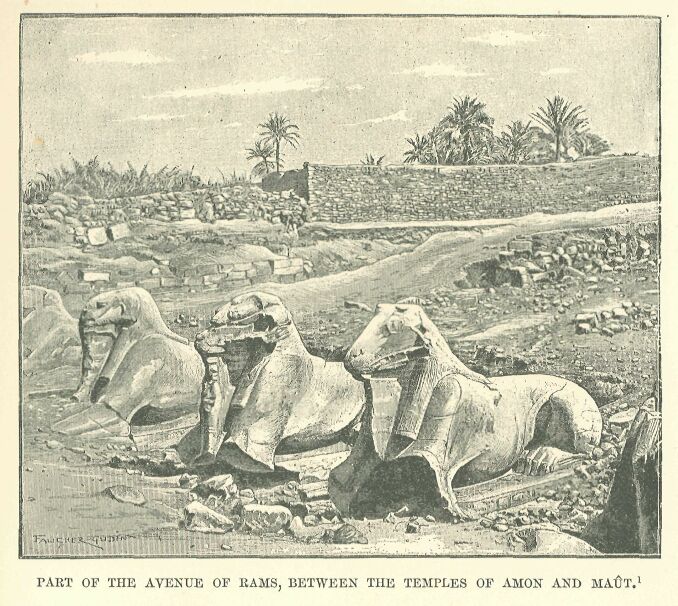

067.jpg Part of the Avenue Of Rams, Between The Temples Of Amon and MaŪt

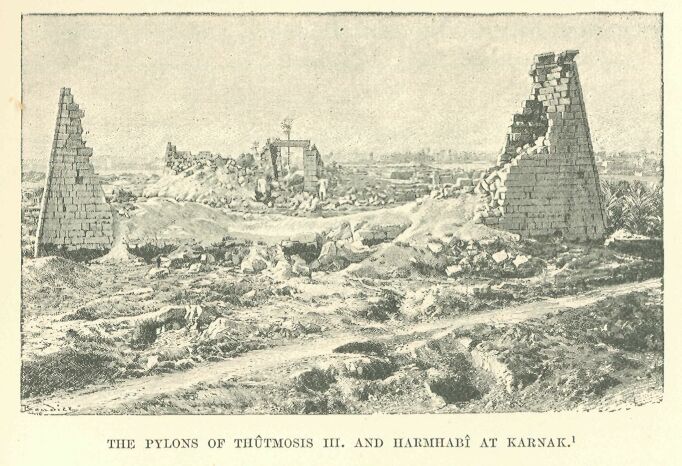

069.jpg the Pylons of ThŪtmosis Iii. And HarmhabĪ At Kaknak

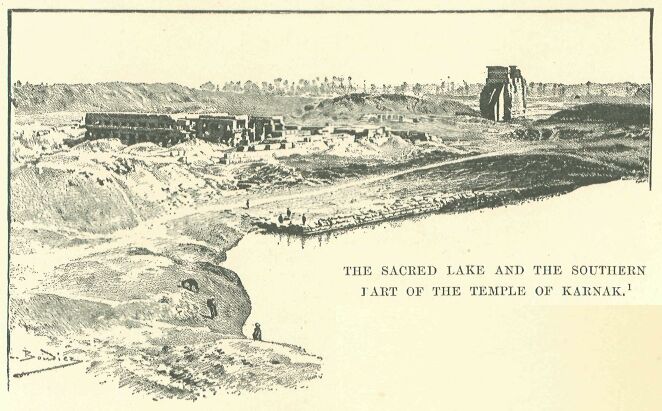

070.jpg Sacred Lake Akd the Southern Part of The Temple Of Karnak.

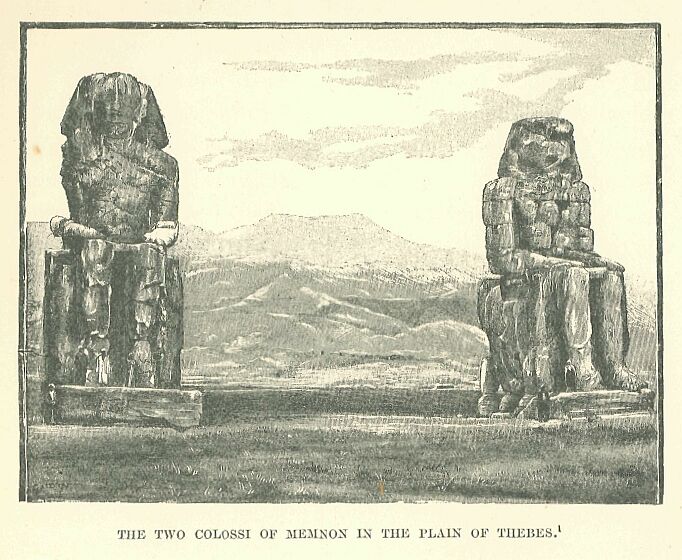

073.jpg the Two Colossi of Memnon in The Plain Of Thebes

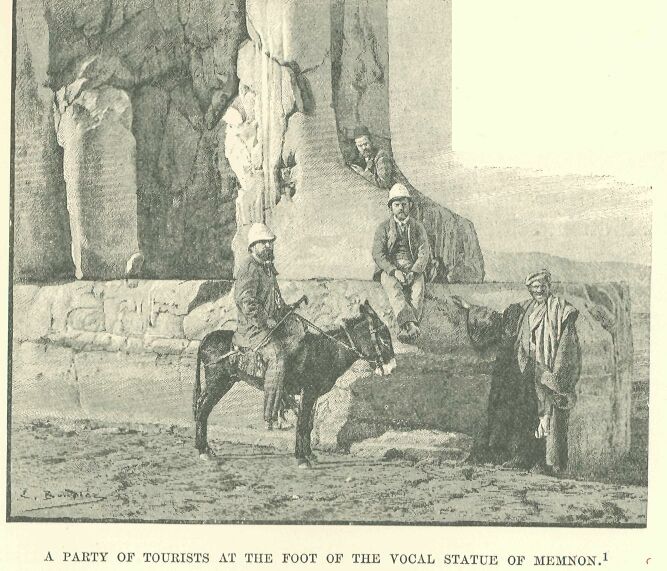

076.jpg a Party of Tourists at the Foot Of The Vocal Statue of Memnok

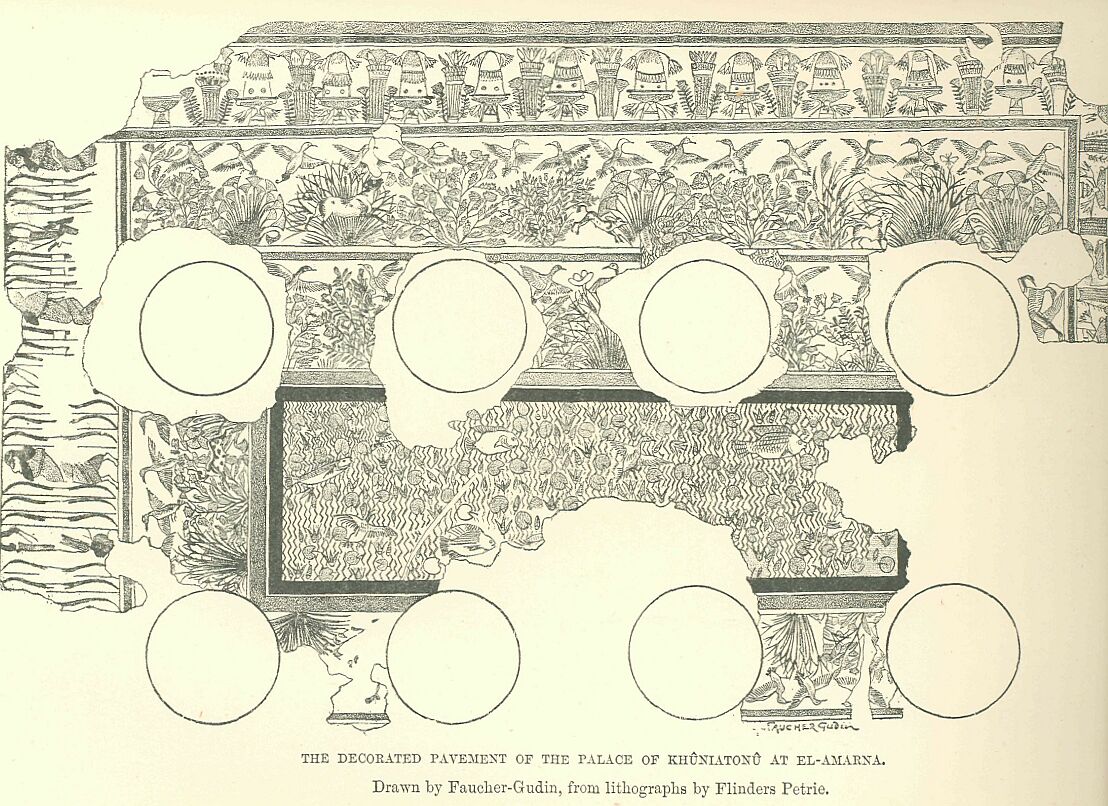

087.jpg the Decorated Pavement of The Palace

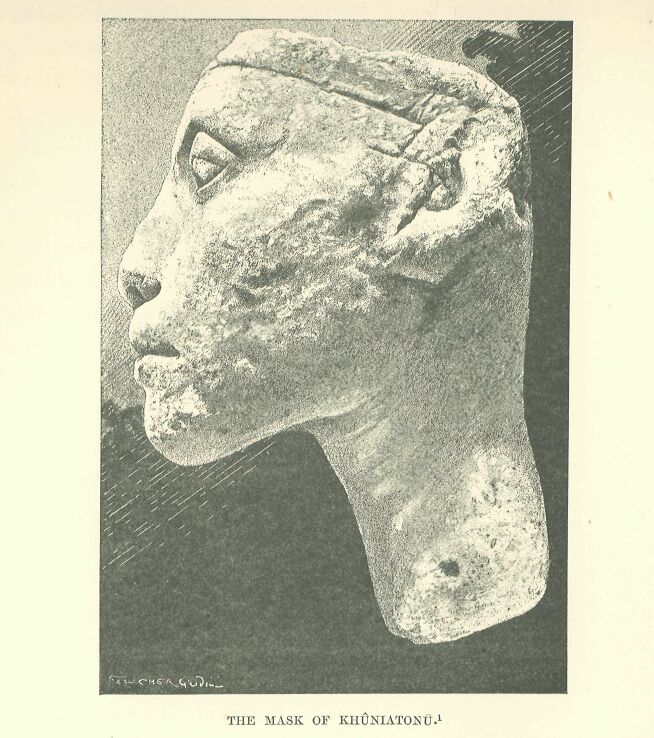

095.jpg the Mask of KihŪniatonŪ

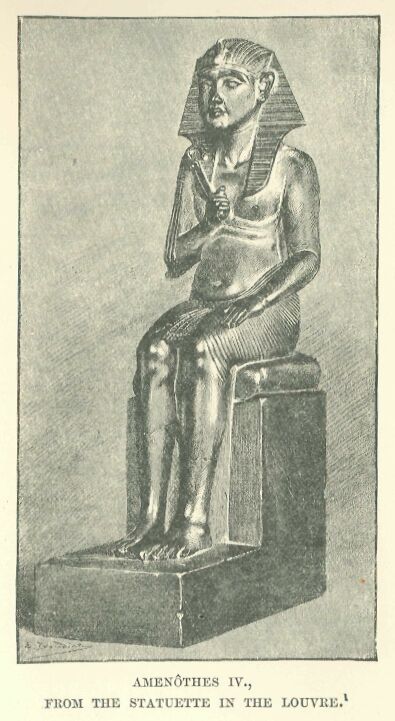

096.jpg AmenŌthes Iv., from the Statuette in The Louvre.

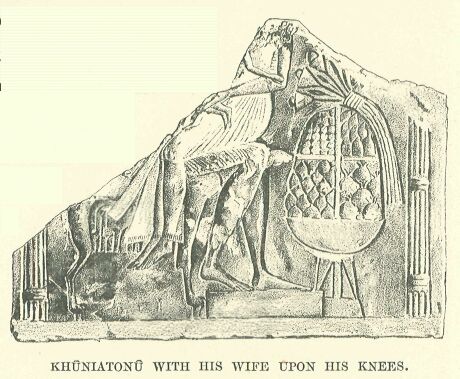

098.jpg KhŪniatonŪ and his Wife Rewarding One of The Great Officers of the Court

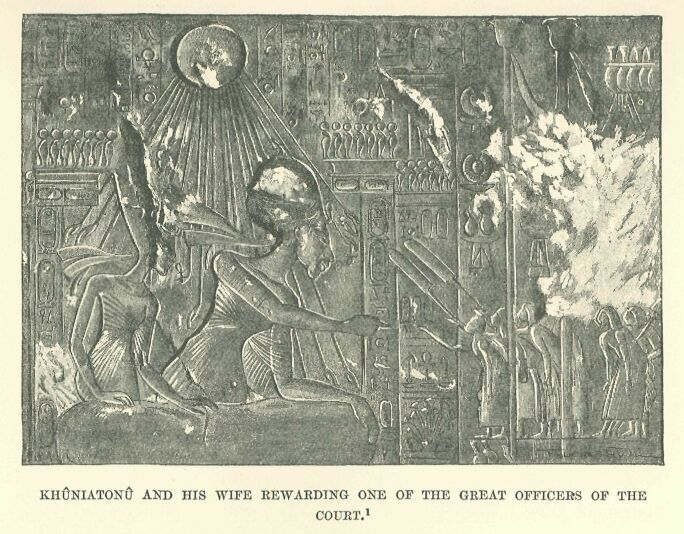

100.jpg the Door of a Tomb at Tel El-amarna

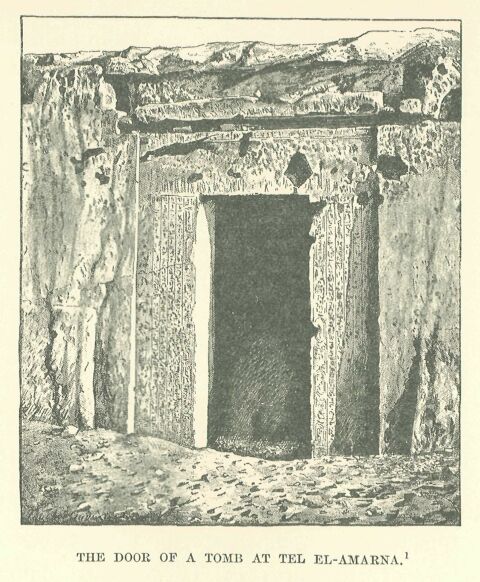

103.jpg Interior of a Tomb at Tel El-amarna

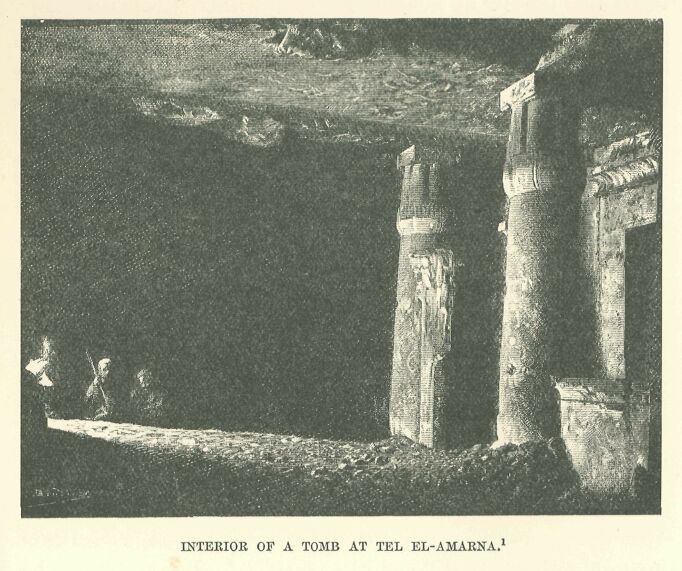

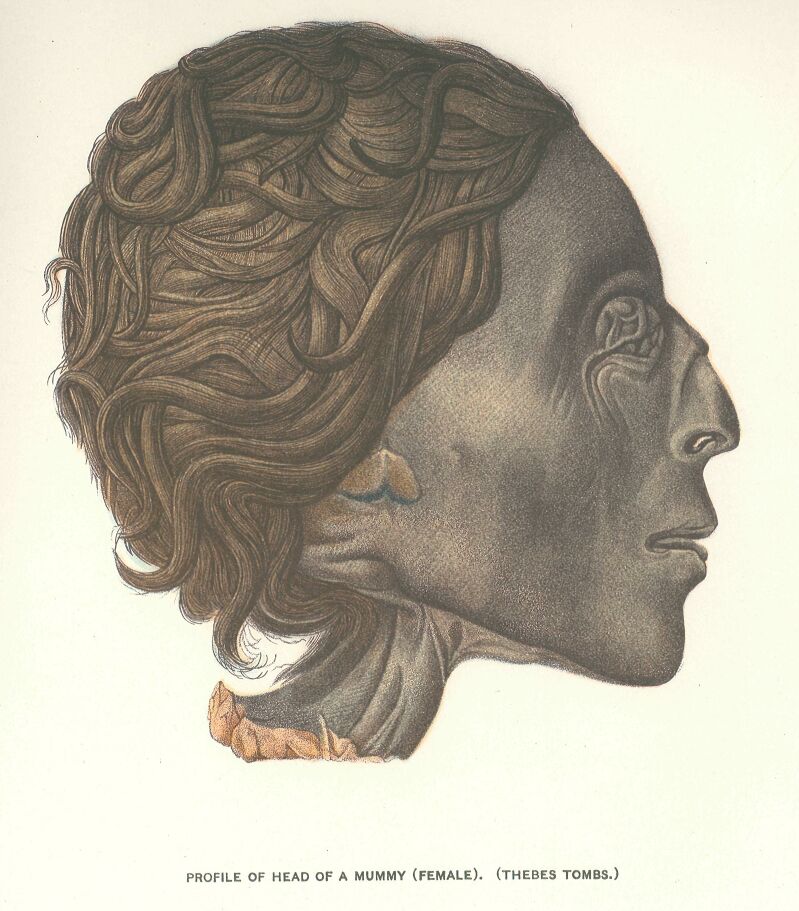

104.jpg Profile of Head Of Mummy (thebes Tombs.)

106.jpg Two of the Daughters Of KhŪhi AtonŪ

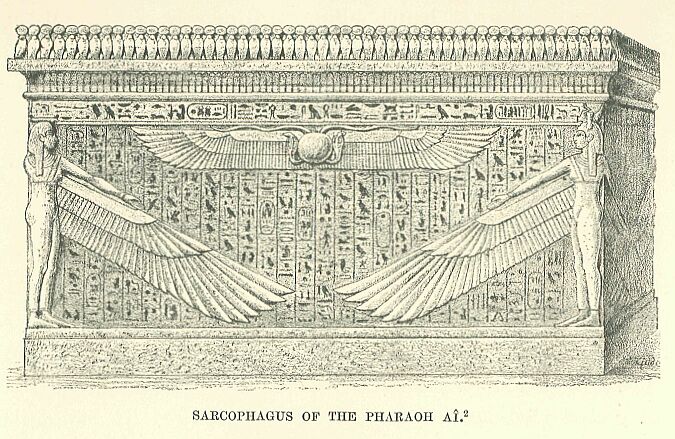

111.jpg Sarcophagus of the Pharaoh AĪ

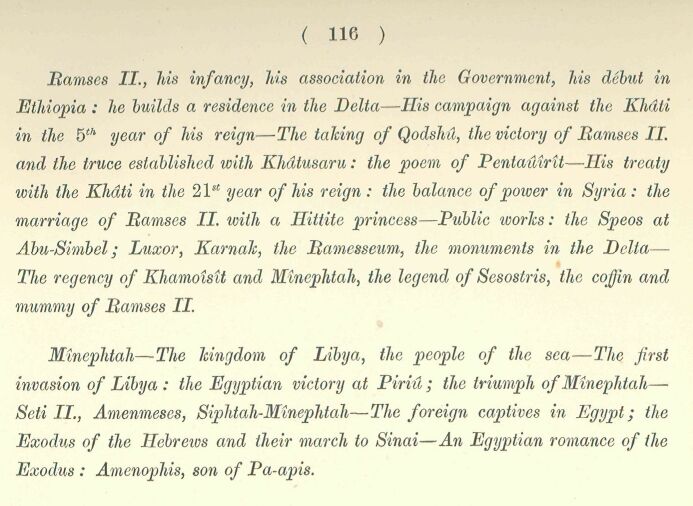

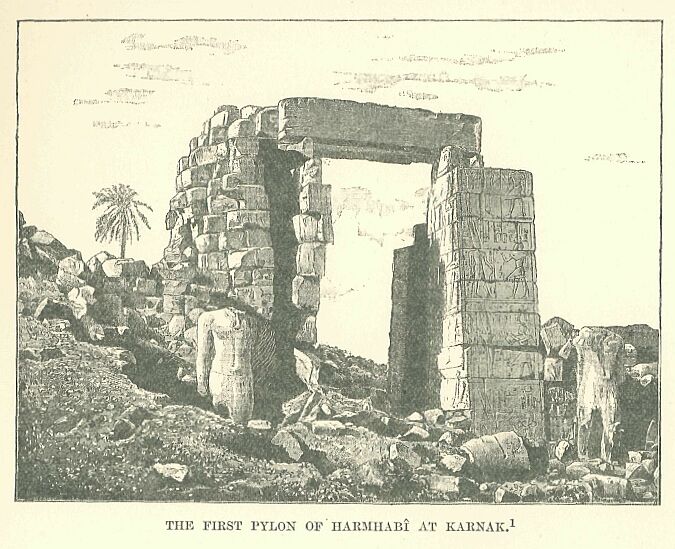

123.jpg the First Pylon of HarmhabĪ at Karnak

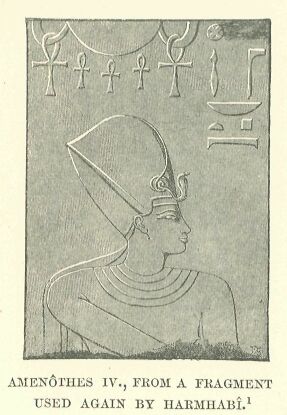

127.jpg Amenothes IV. From a Fragment Used Again By Harmhabi

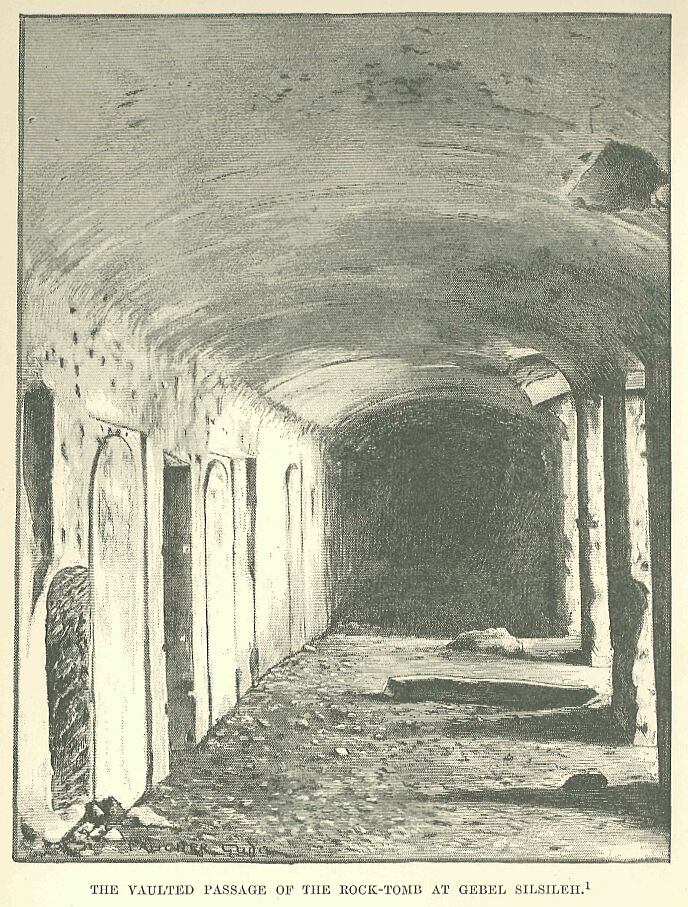

129.jpg the Vaulted Passage of The Rock-tomb at Gebel Silsileh

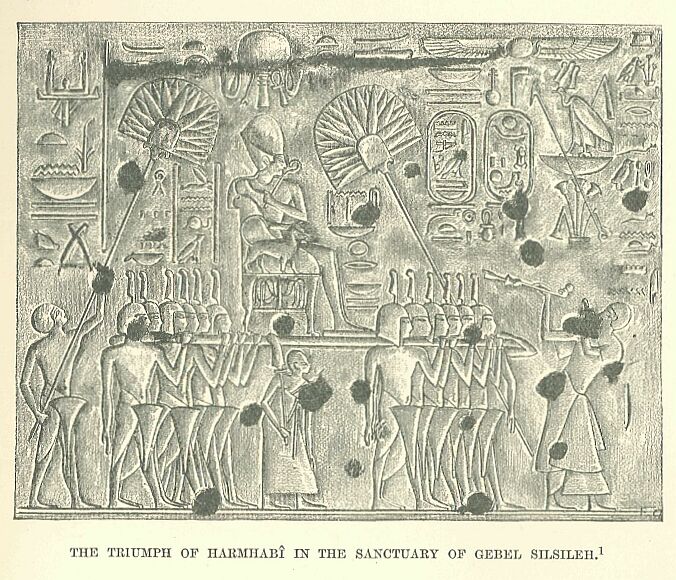

131.jpg the Triumph Of HarmhabĪ in The Sanctuary of Gebel Silsileh

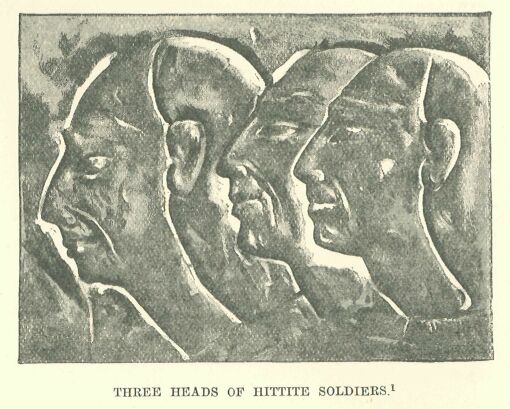

135.jpg Three Heads of Hittite Soldiers

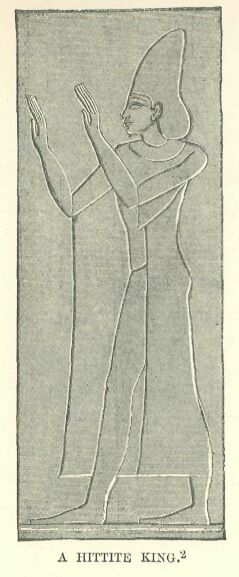

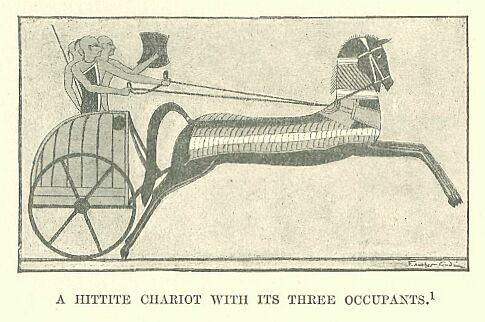

140.jpg a Hittite Chariot With Its Three Occupants

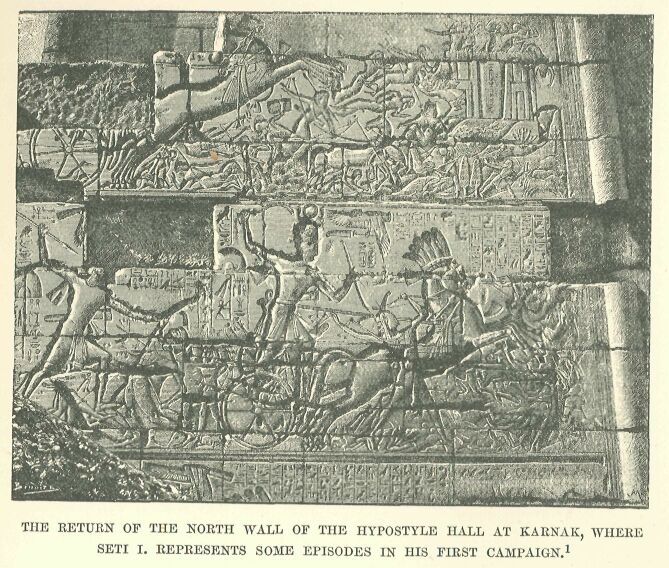

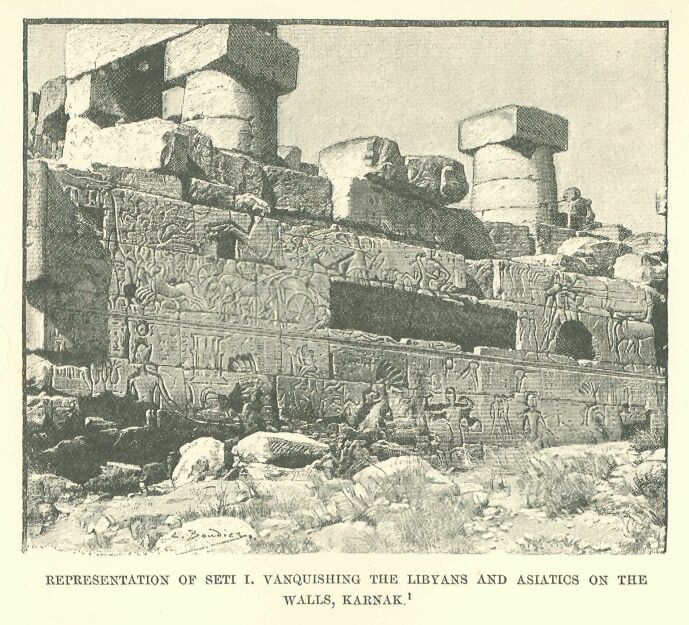

166.jpg Representation of Seti I. Vanquishing the Libyans And Asiatics on the Walls, Karnak

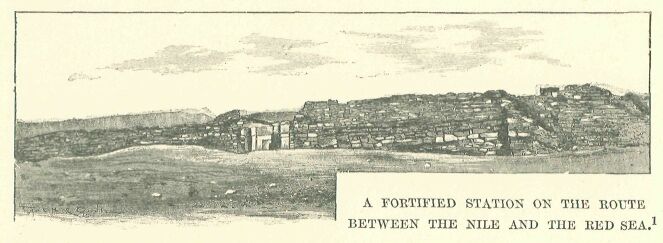

168.jpg a Fortified Station on the Route Between The Nile And the Red Sea.

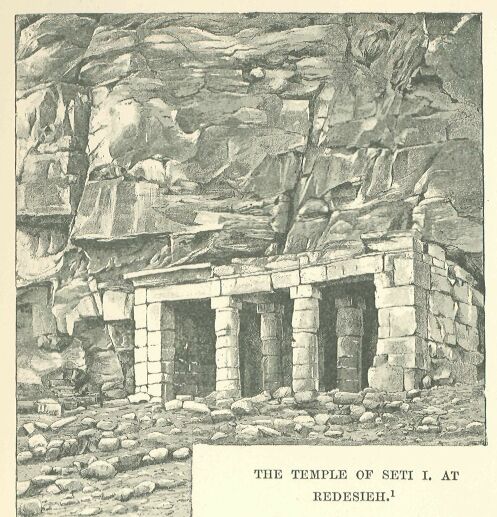

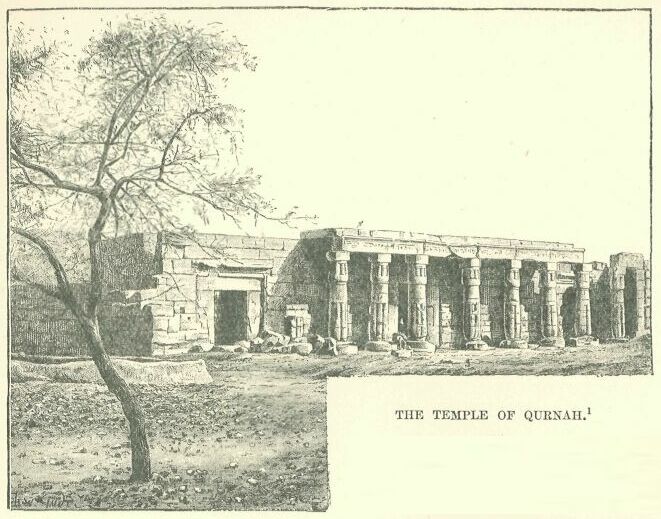

169.jpg the Temple of Seti I. At Redesieh

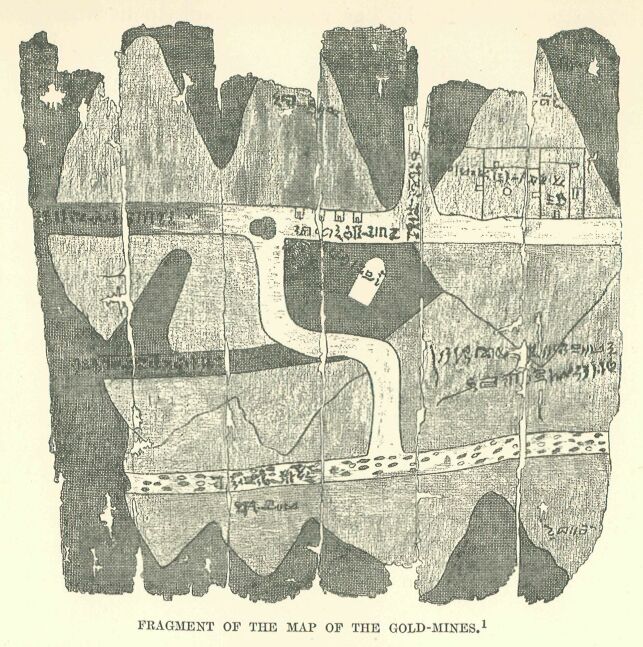

170.jpg Fragment of the Map Of The Gold-mines

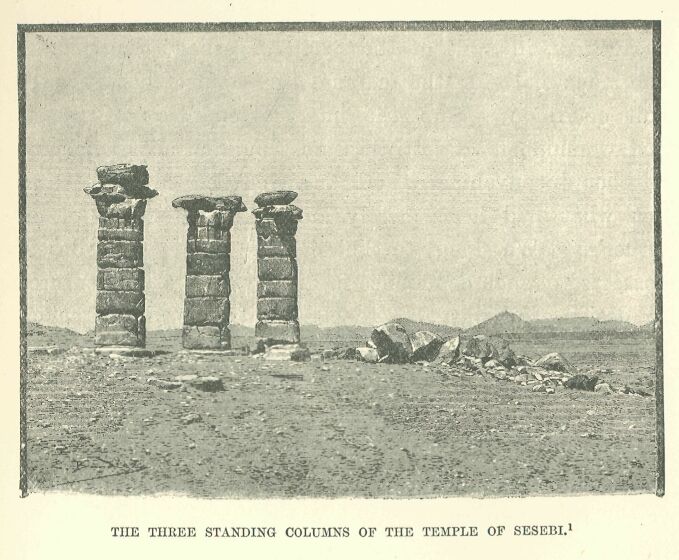

171.jpg the Three Standing Columns of The Temple Of Sesebi

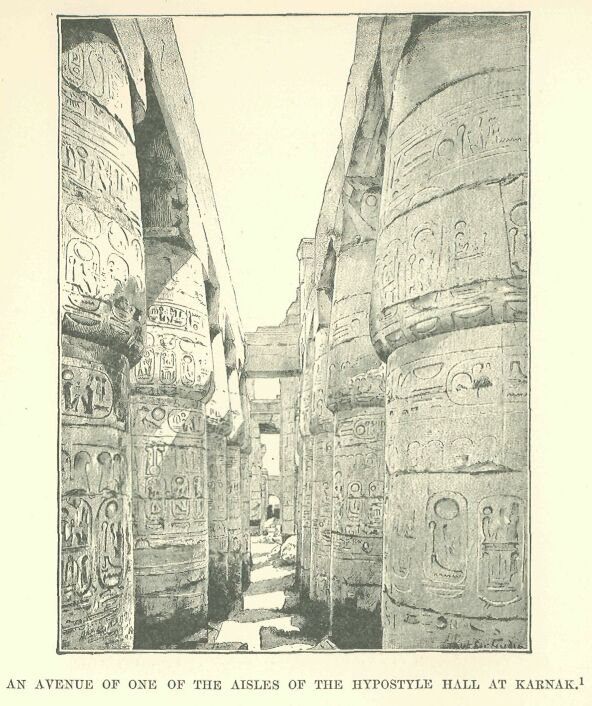

173 an Avenue of One Of the Aisles Of The Hypostyle Hall At Karnak

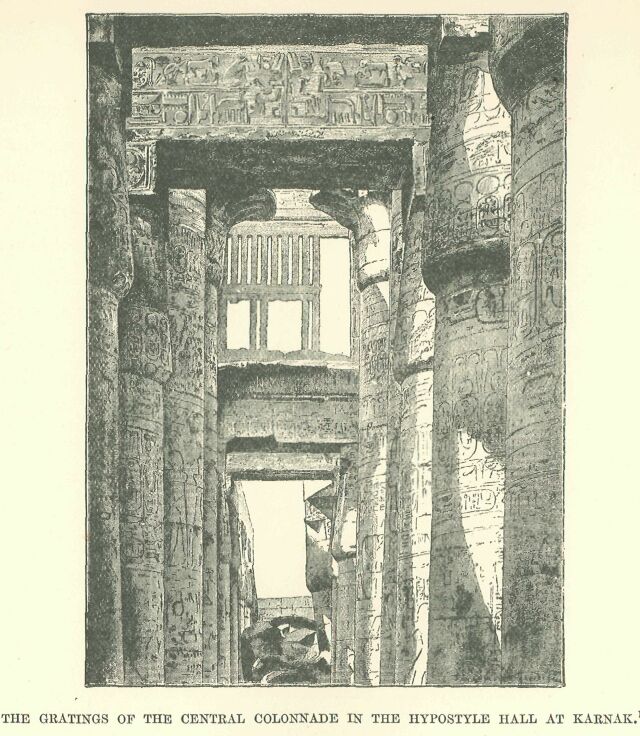

174.jpg the Gratings of The Central Colonnade in The Hypostyle Hall at Karnak

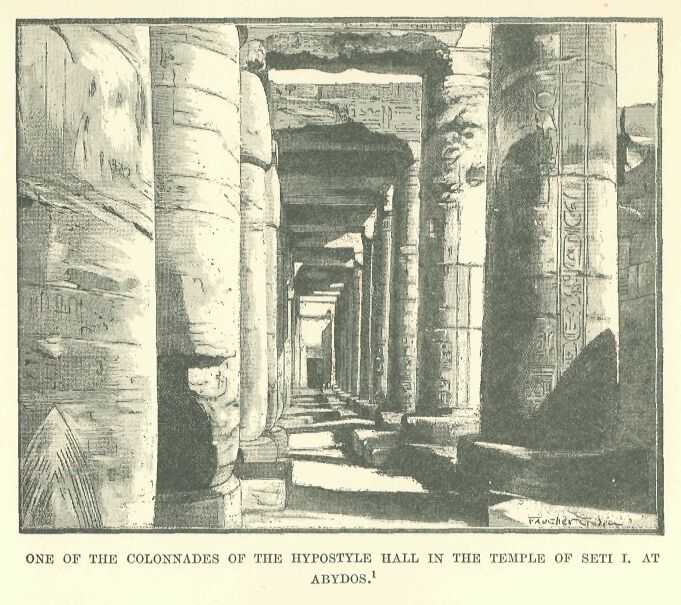

176.jpg One of the Colonnades Of The Hypostyle Hall In The Temple of Seti I. At Abydos

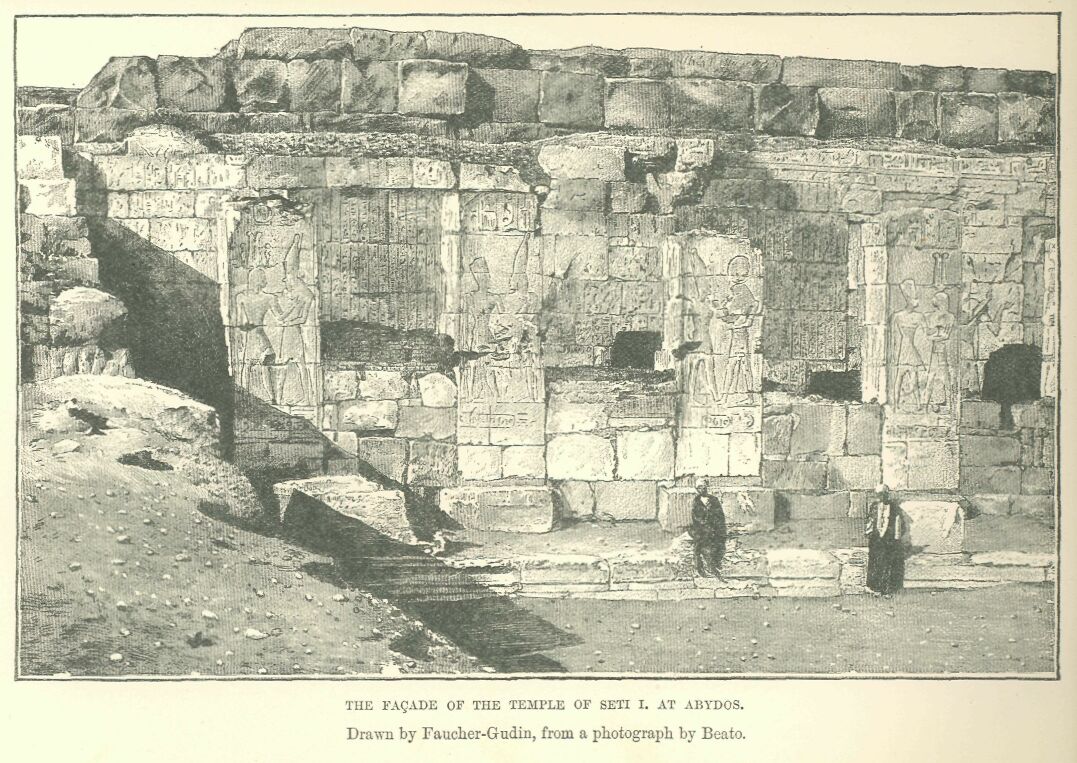

176b.jpg the Facade of The Temple Of Seti

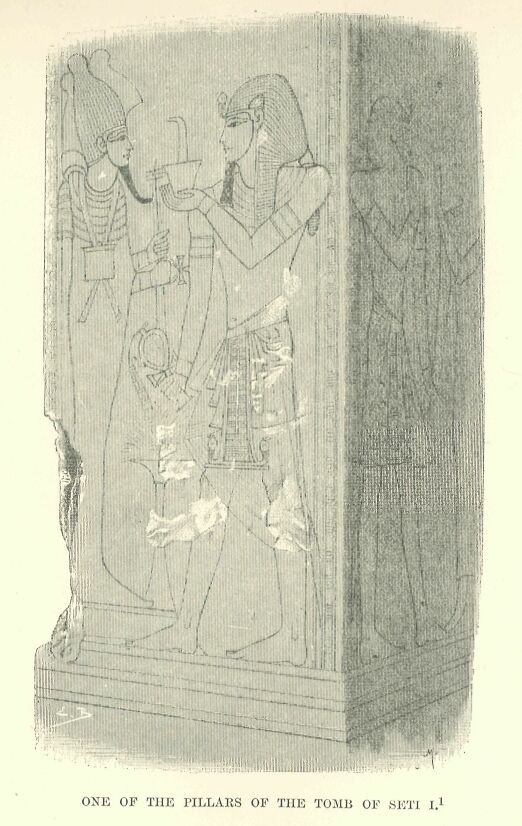

184.jpg One of the Pillars Of The Tomb Of Seti I.

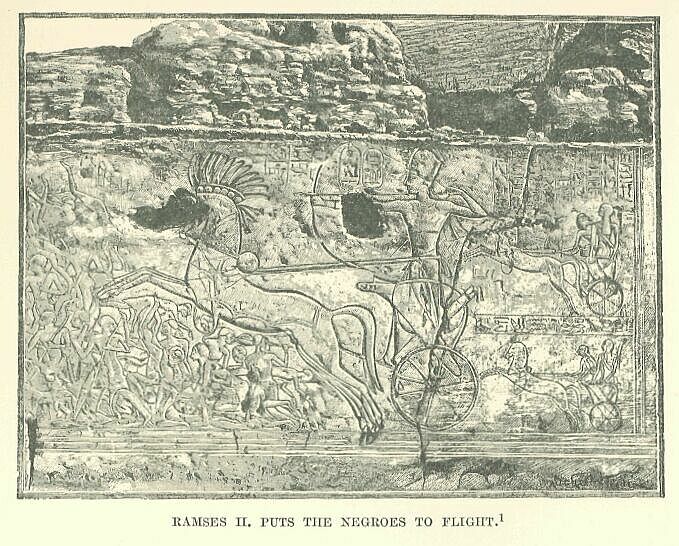

187.jpg Ramses II. Puts the Negroes to Flight

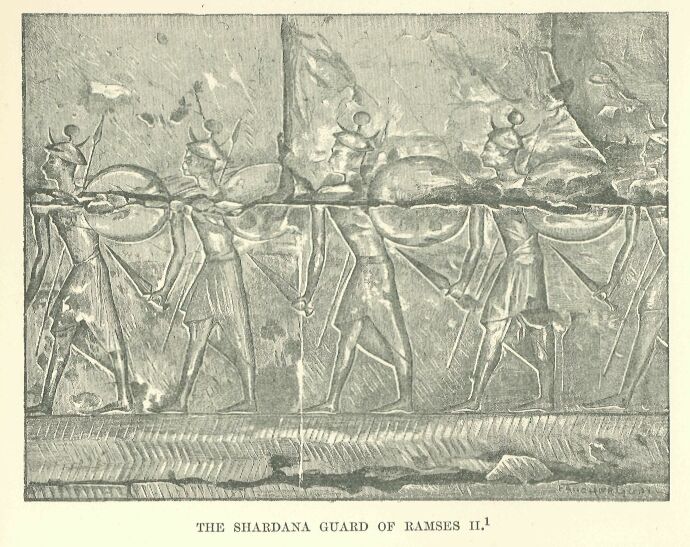

193.jpg the Shardana Guard of Ramses II.

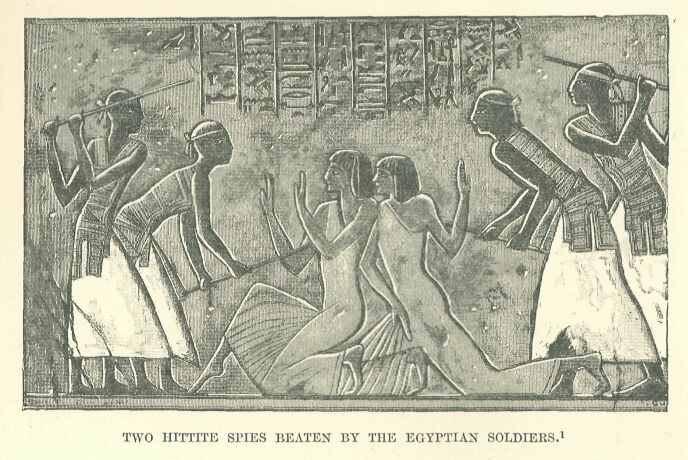

195.jpg Two Hittite Spies Beaten by the Egyptian Soldiers

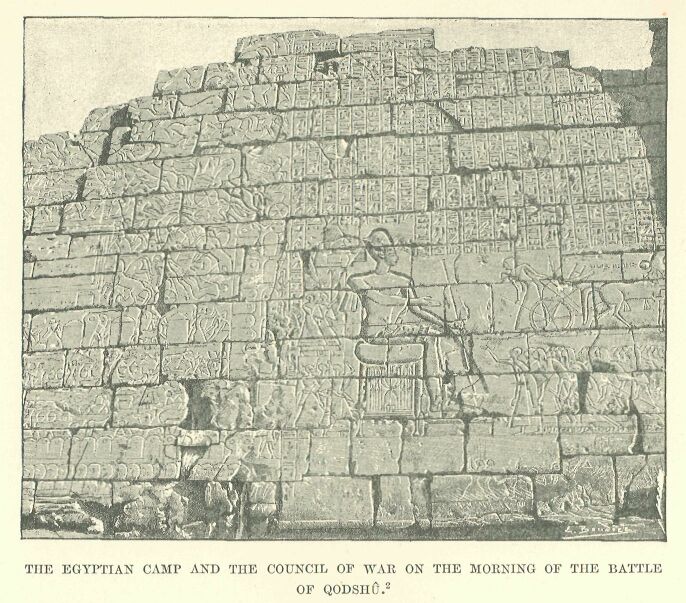

196.jpg the Egyptian Camp and The Council of War on The Morning of the Battle Of QodshŪ

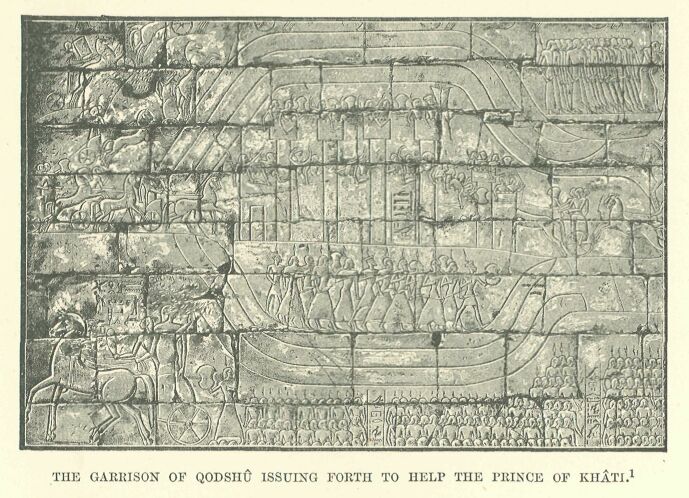

198.jpg the Garrison of QodshŪ Issuing Forth to Help The Prince of KhĀti.

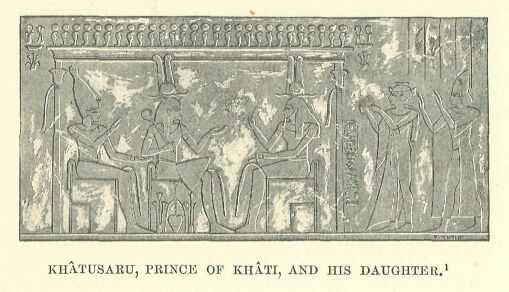

214.jpg KhĀtusaru, Prince of KhĀti, and his Daughter

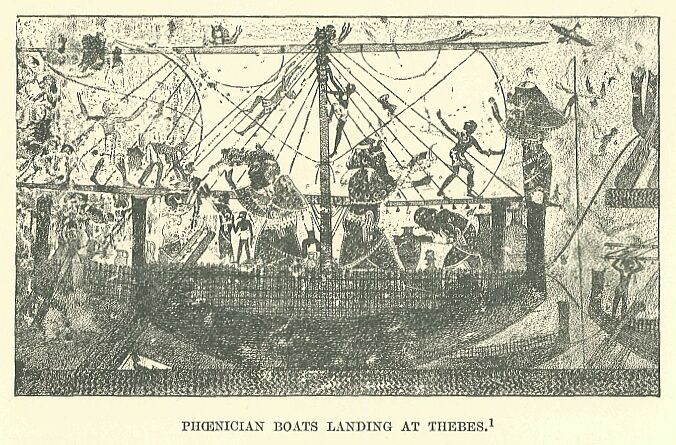

218.jpg Phoenician Boats Landing at Thebes

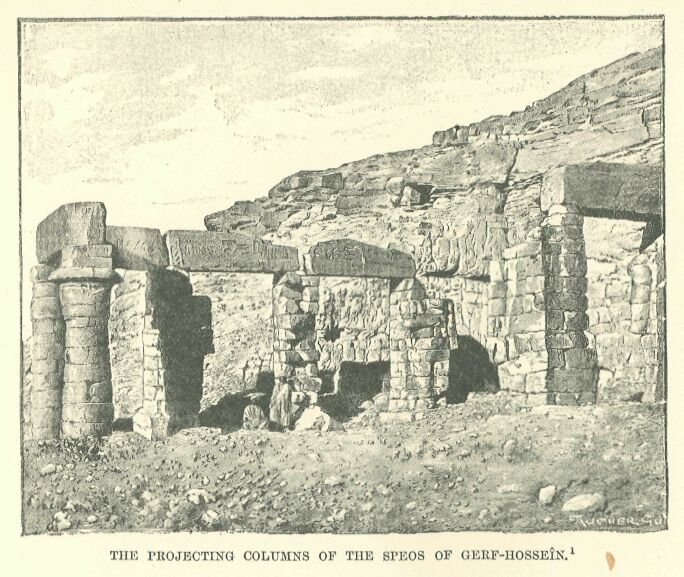

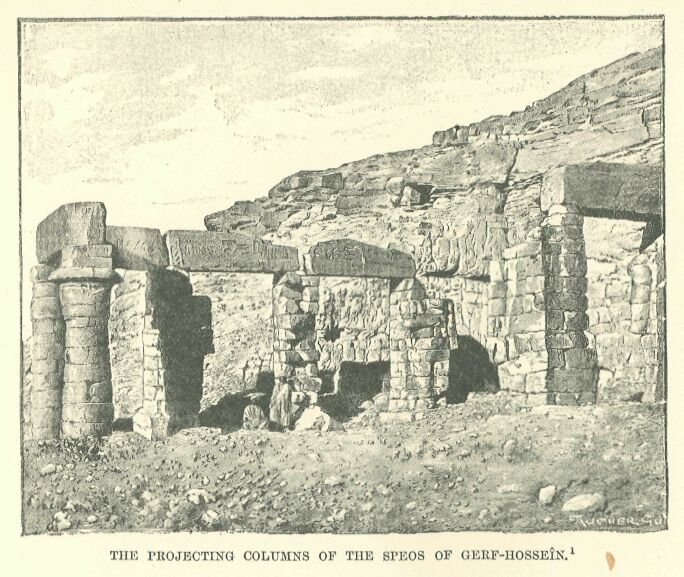

221.jpg the Projecting Columns of The Speos Of Gerf-hosseĪn

221.jpg the Caryatides of Gerf-hosseĪn

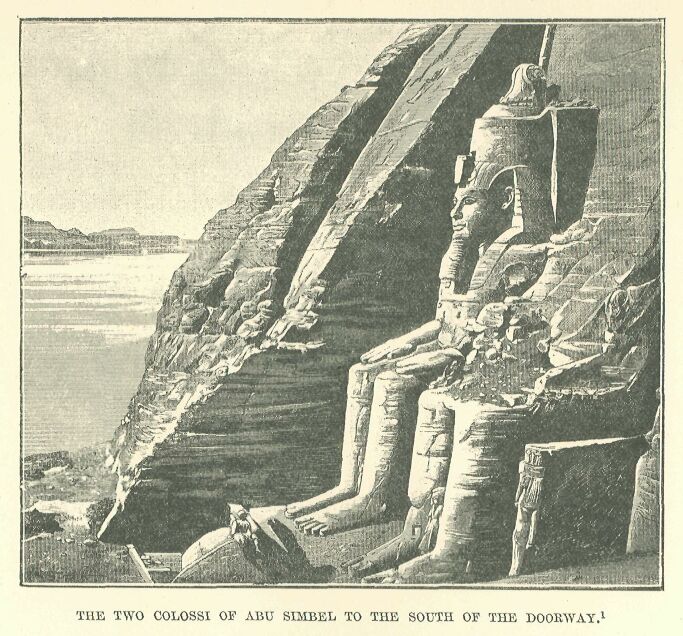

224.jpg the Two Colossi of Abu Simbel to The South Of The Doorway

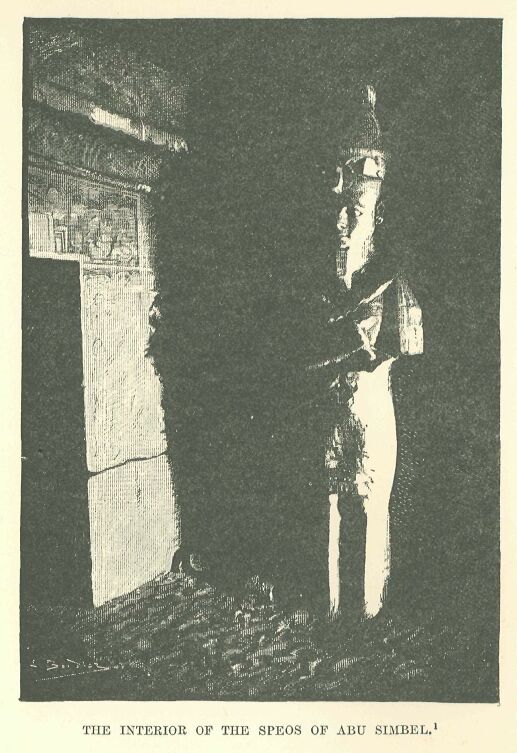

225.jpg the Interior of The Speos Of Abu Simbel

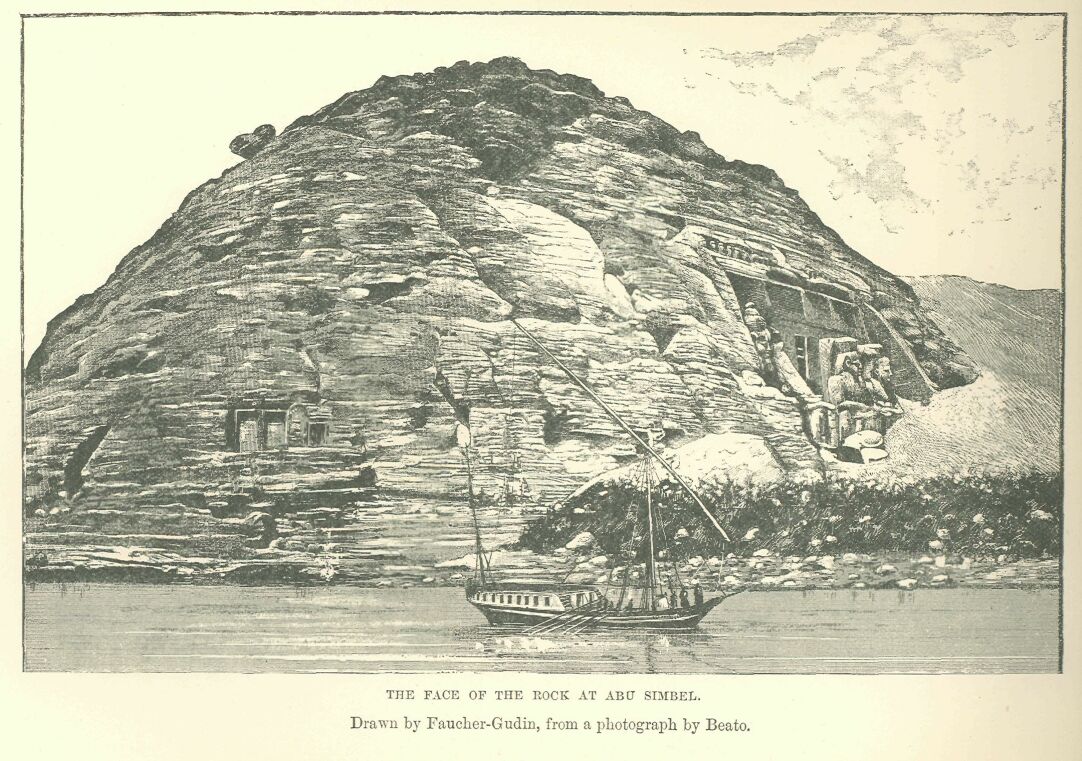

228.jpg the Face of The Rock at Abu Simgel

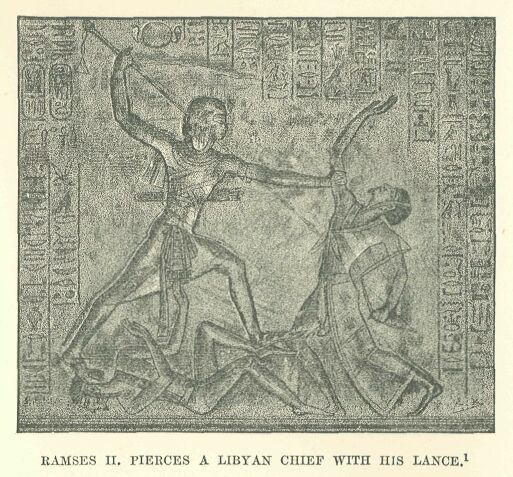

229.jpg Ramses Ii. Pierces a Libyan Chief With his Lance

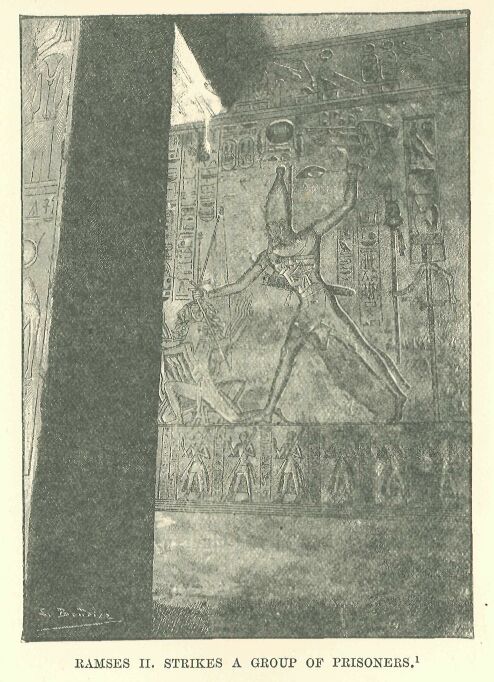

230.jpg Ramses Ii. Strikes a Group of Prisoners

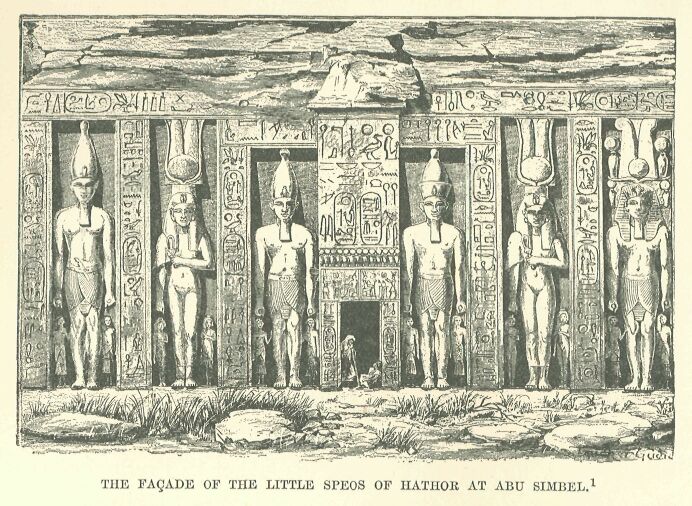

231.jpg the Faēade of The Little Speos Of Hauthor at Abu Simbel

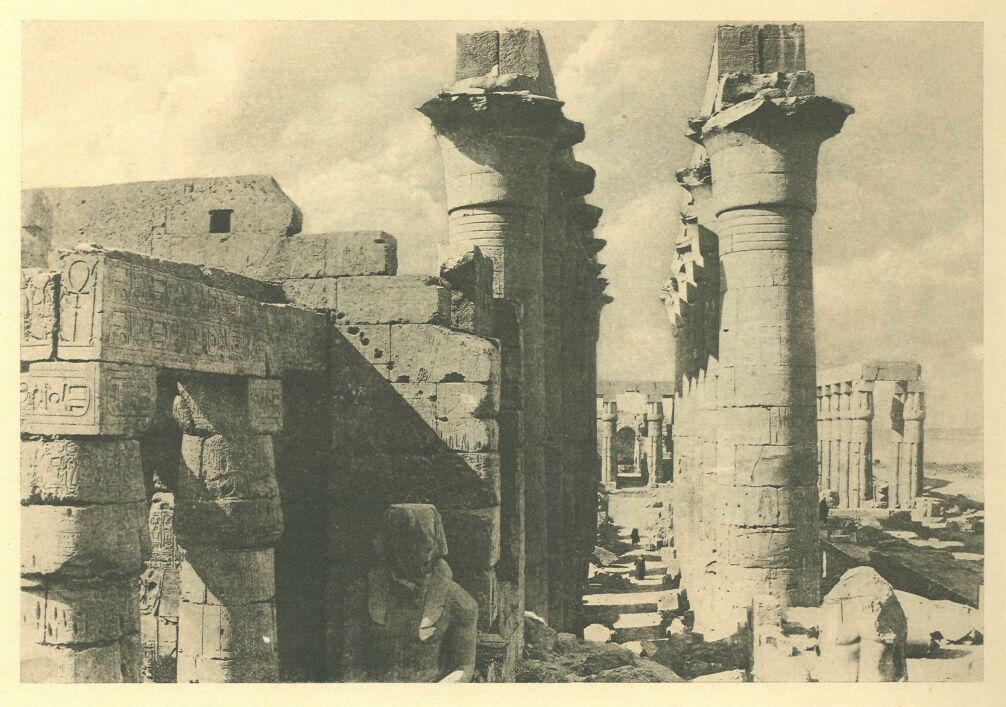

232.jpg Columns of Temple at Luxor

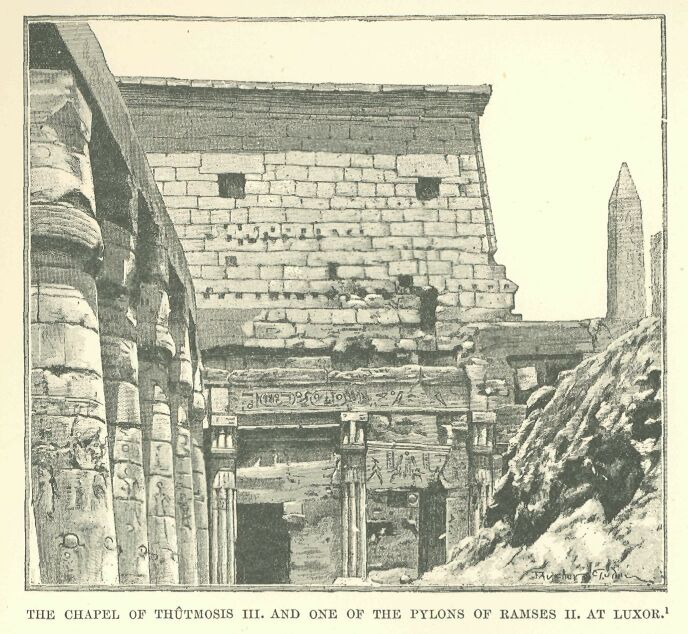

233.jpg the Chapel of Thutmosis III. And One Of The Pylons of Ramses Ii. At Luxor

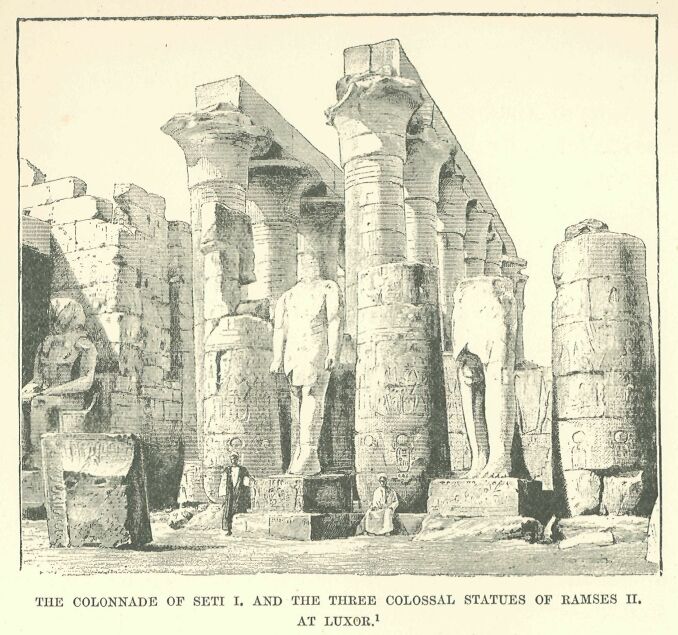

235.jpg the Colonnade of Seti I. And The Three Colossal Statues of Ramses II. At Luxor

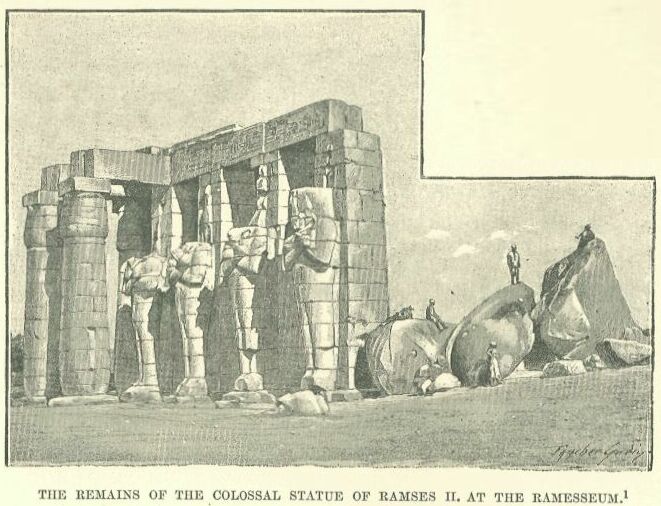

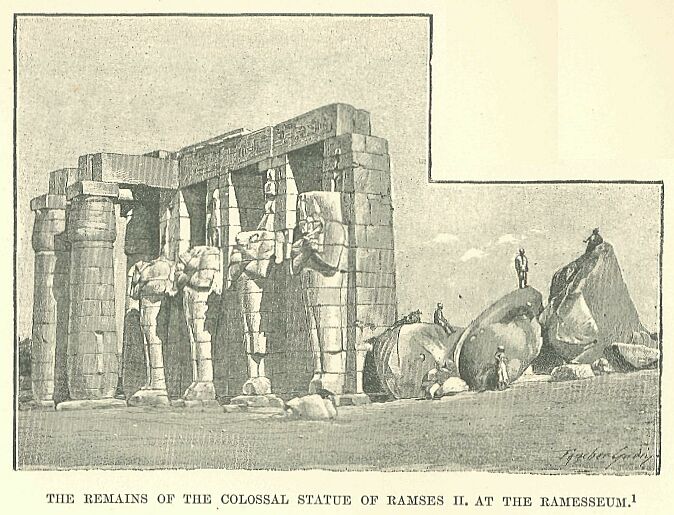

237.jpg the Remains of The Colossal Statue Of Ramses Ii. At the Ramesseum

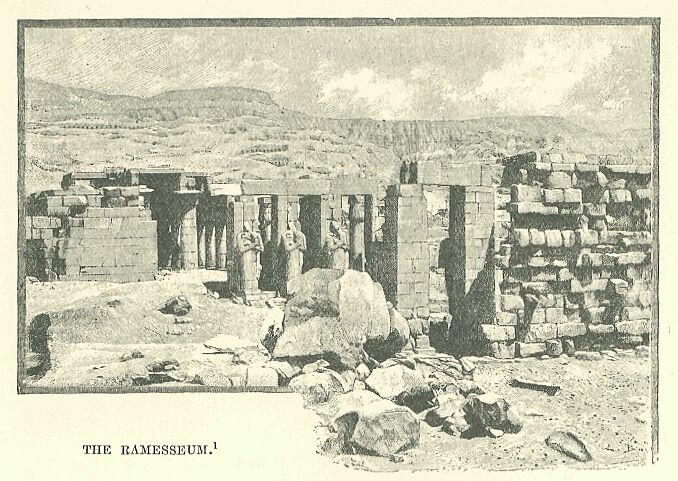

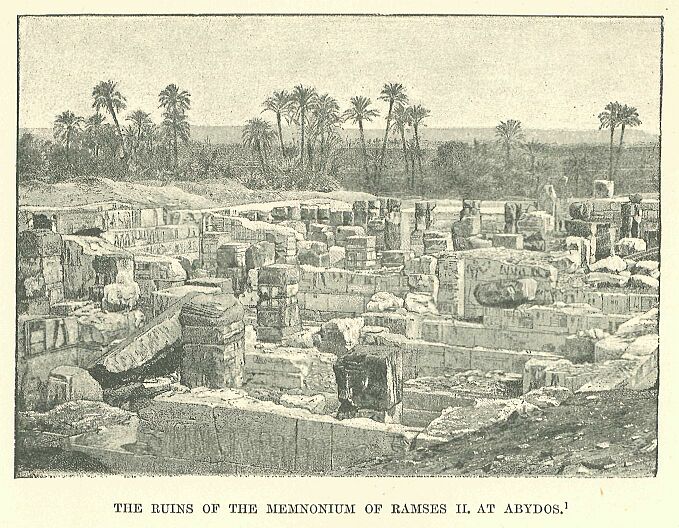

240.jpg the Ruins of The Memnonium Of Ramses Ii. At Abydos

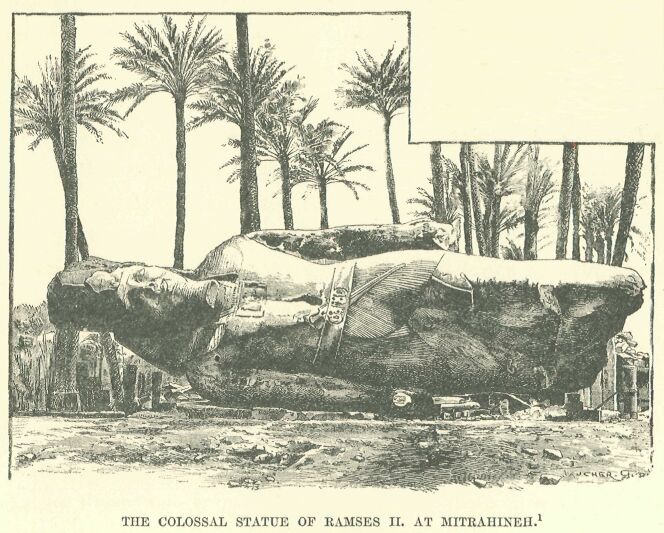

242.jpg the Colossal Statue of Ramses II. At Mitrahineh

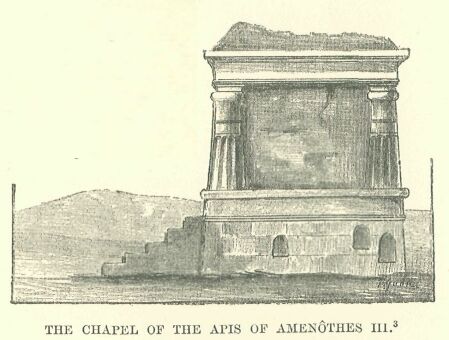

245.jpg the Chapel of The Apis Of AmekŌthes III.

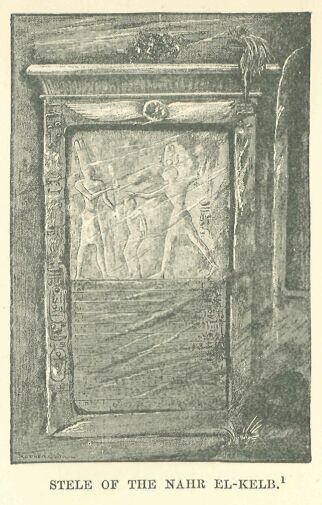

247.jpg Stele of the Nahr El-kelb

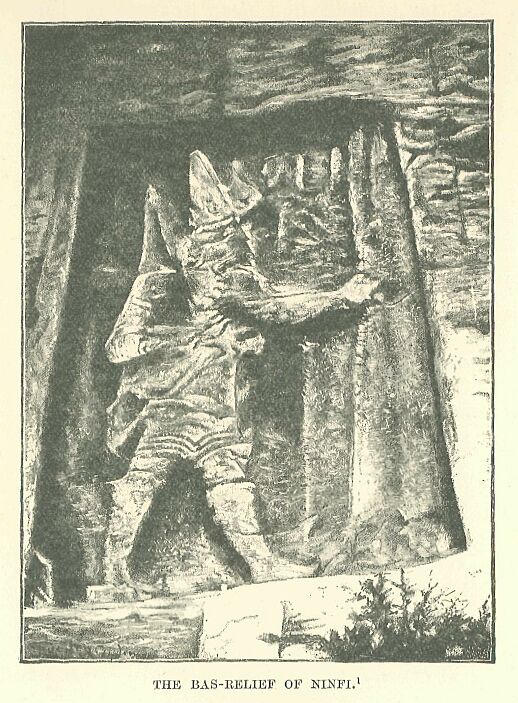

248.jpg the Bas-belief of Ninfi

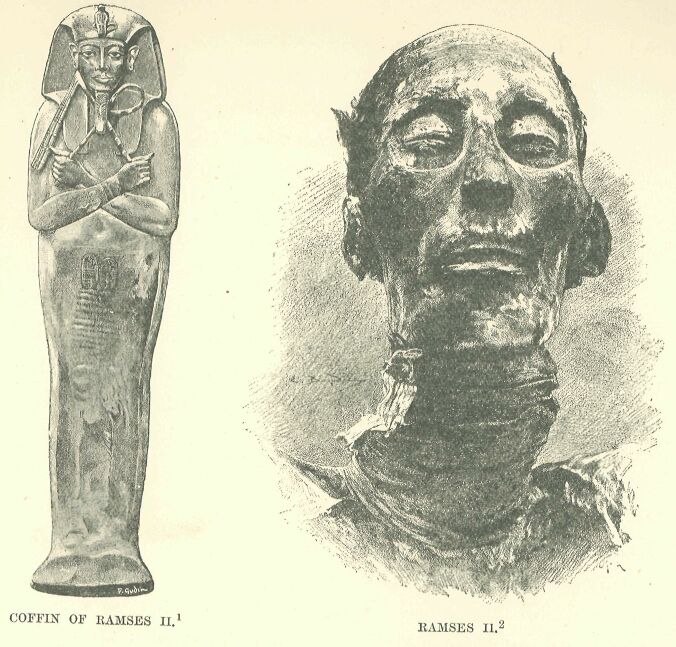

249.jpg the Coffin and Mummy of Ramses II

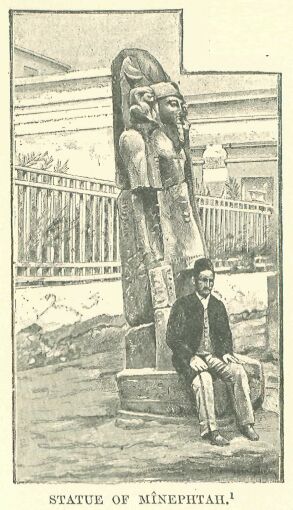

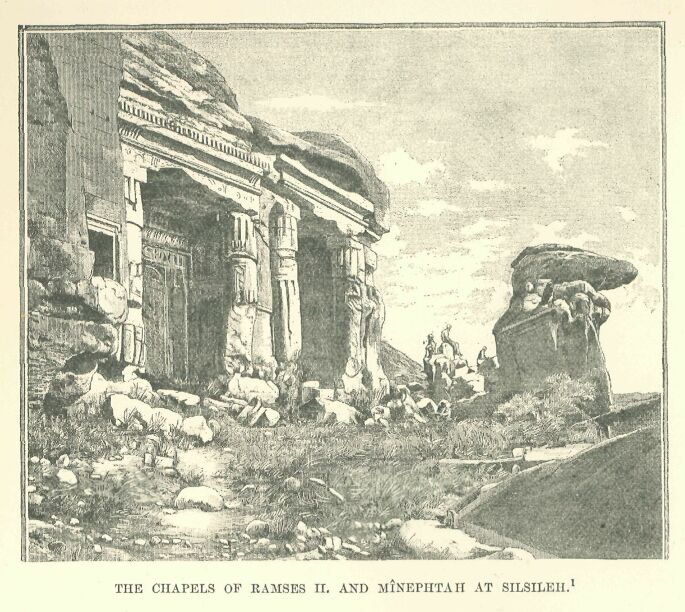

263.jpg the Chapels of Ramses II. And Minephtah At Sisileh

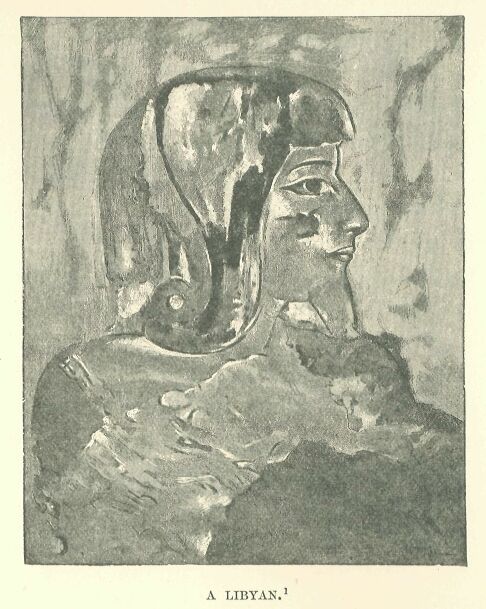

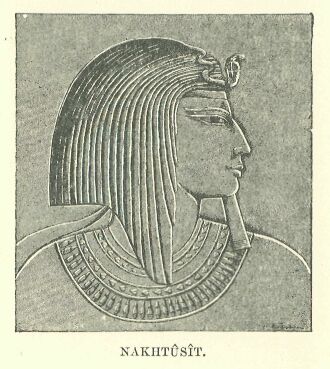

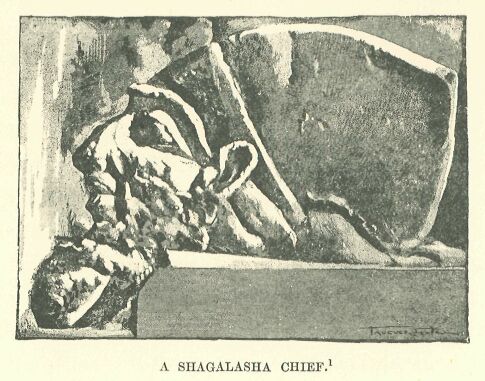

299.jpg One of the Libyan Chiefs Vanquished by Ramses Iii.

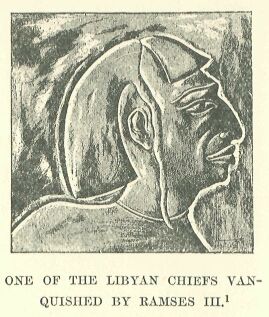

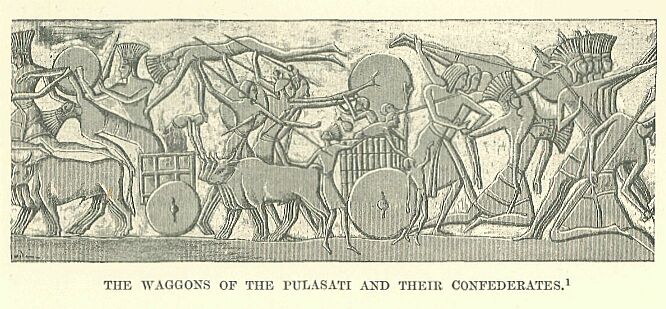

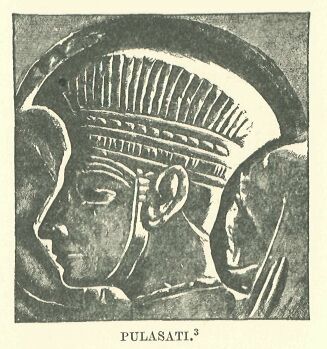

300.jpg the Waggons of The Pulasati and Their Confederates

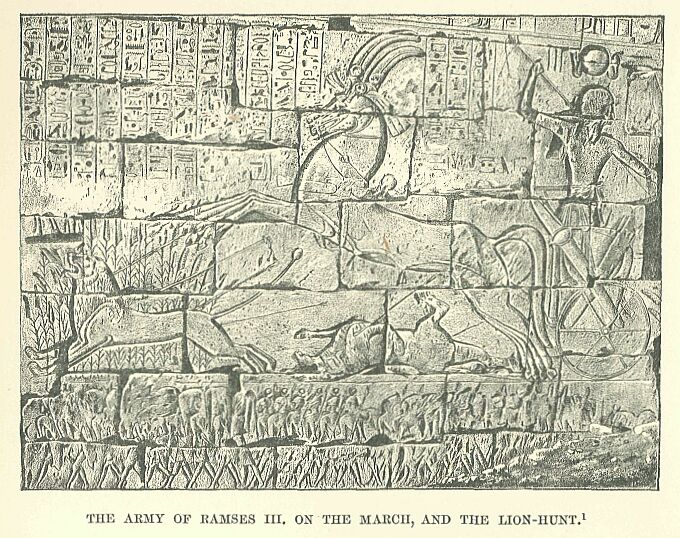

307.jpg the Army Op Ramses III. On The March, and The Lion-hunt

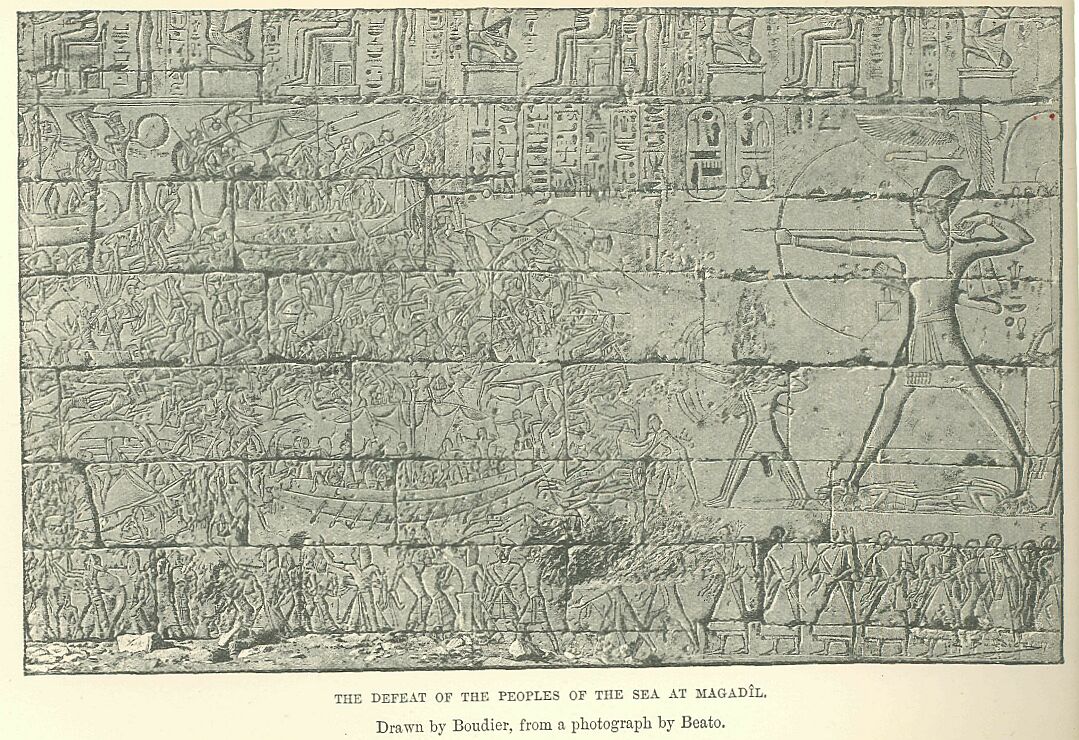

308.jpg the Defeat of The Peoples Of The Sea

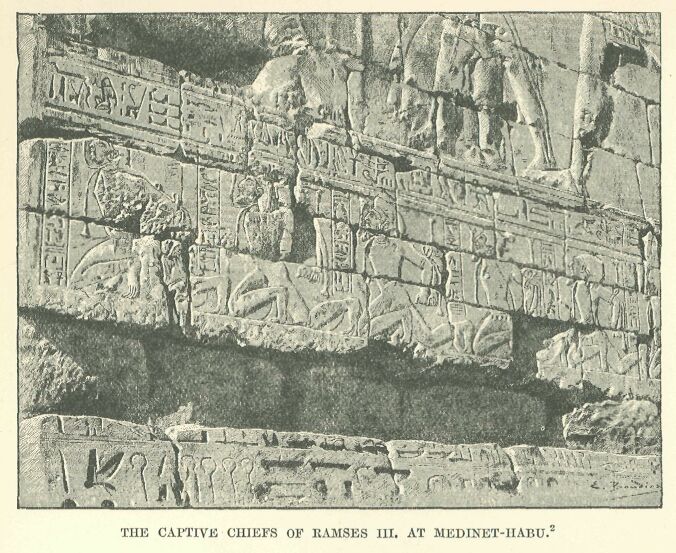

313.jpg the Captive Chiefs of Ramses Iii. At Medinet-ihabu

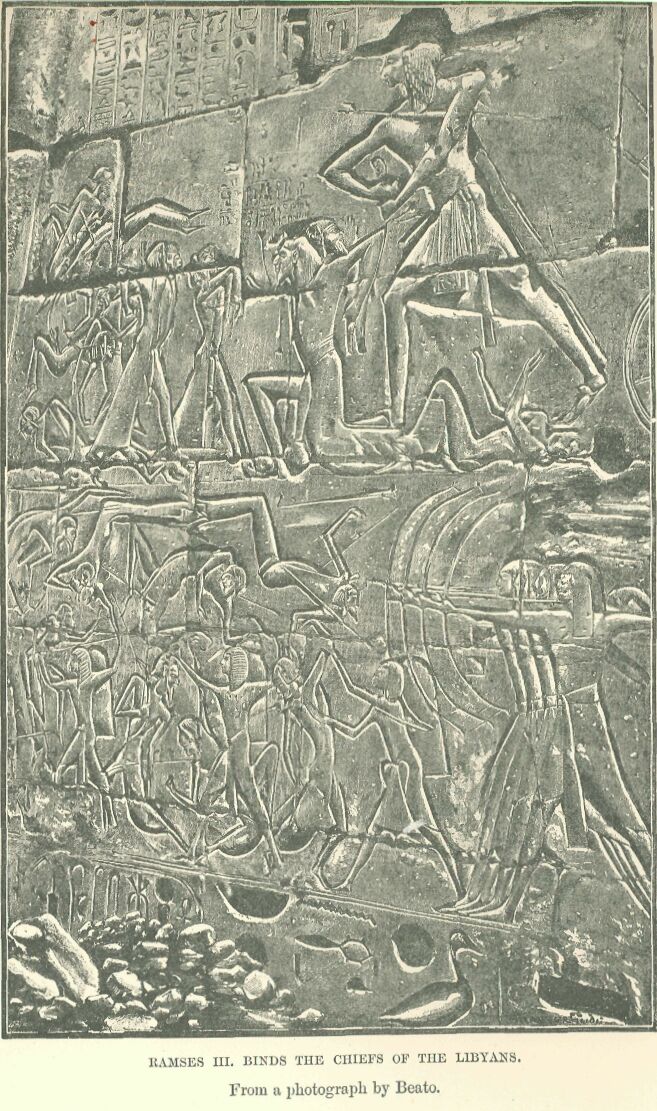

314.jpg Ramses III. Binds the Chiefs of The Libyans

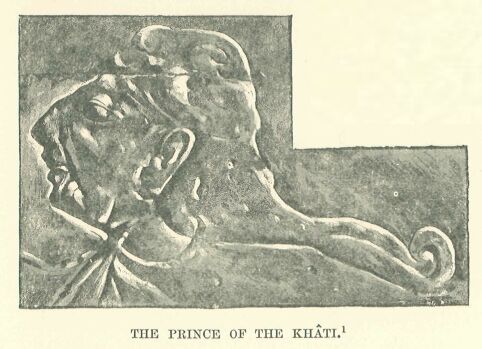

318.jpg the Prince of The Khati

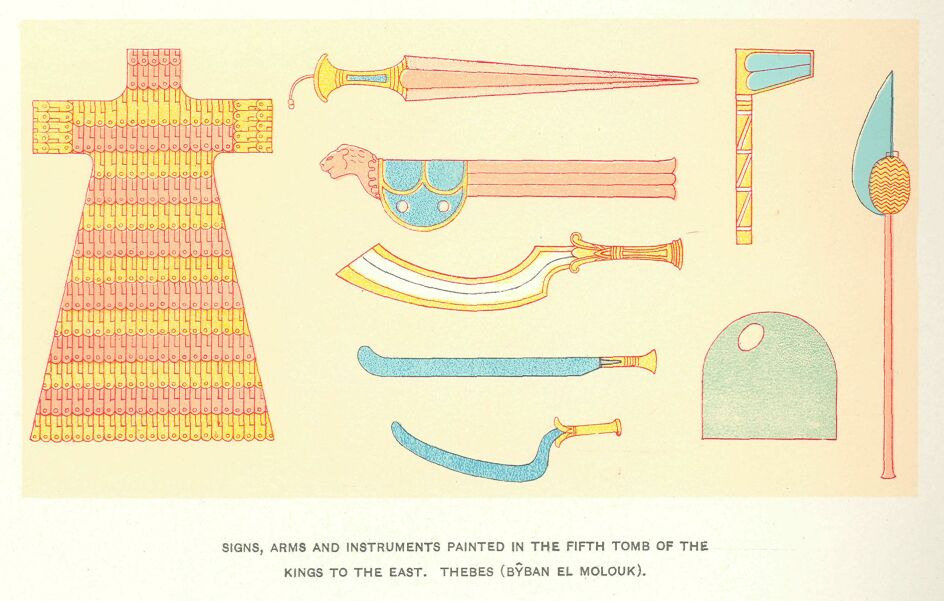

320.jpg Signs, Arms and Instruments

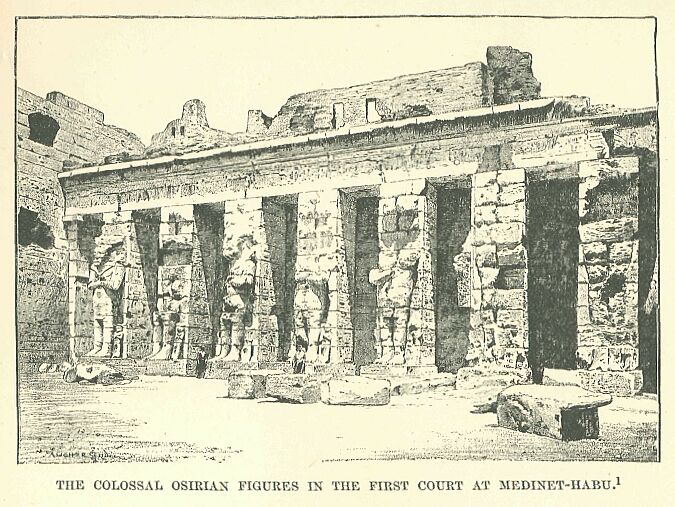

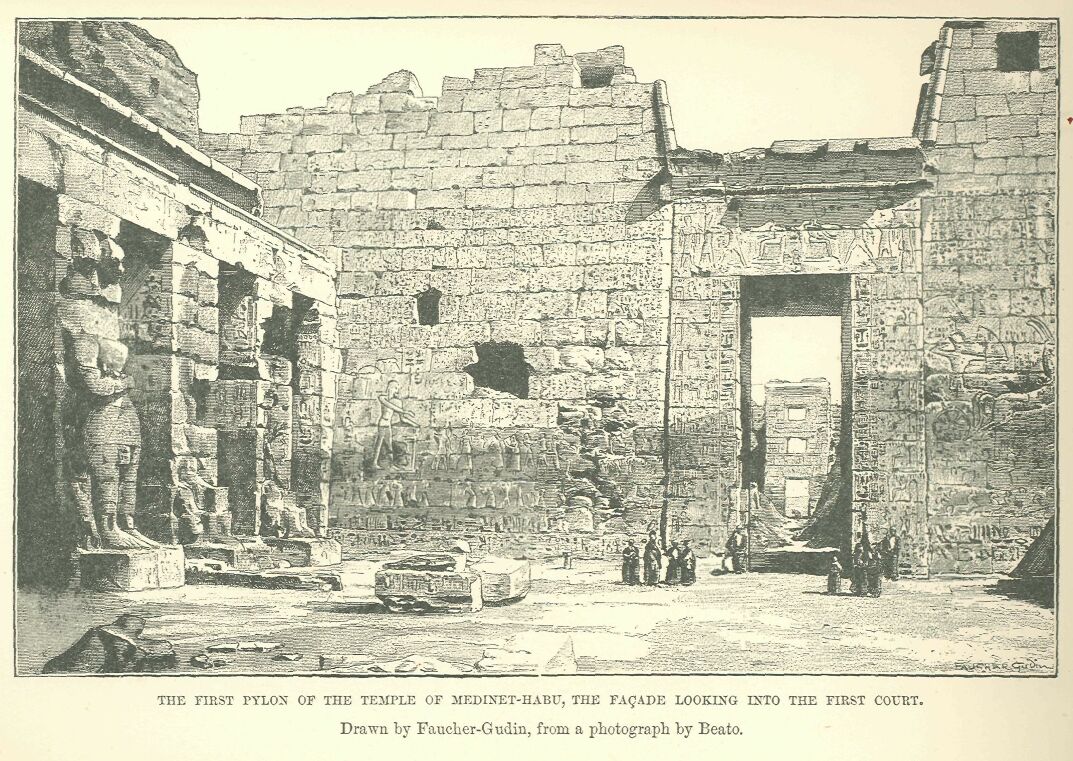

321.jpg the Colossal Osirian Figures in The First Court At Medinet-habu

322.jpg the First Pylon of The Temple

327.jpg the Mummy of Ramses III.

331.jpg a Ramses of the Xxth Dynasty

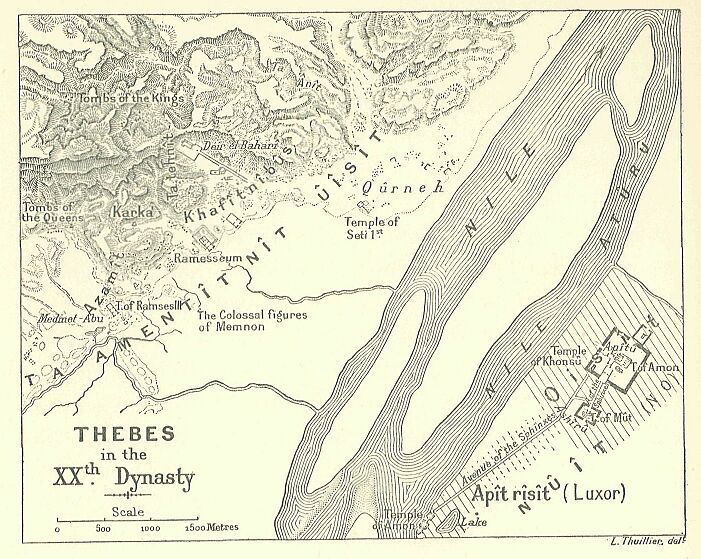

334.jpg Map: Thebes in the Xxth Dynasty

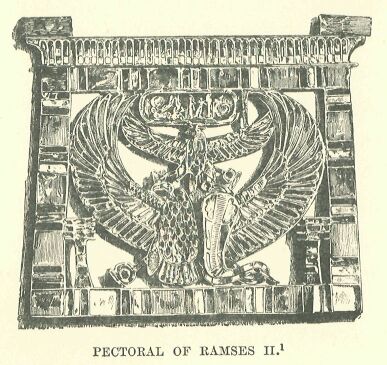

345.jpg Pectoral of Ramses II.

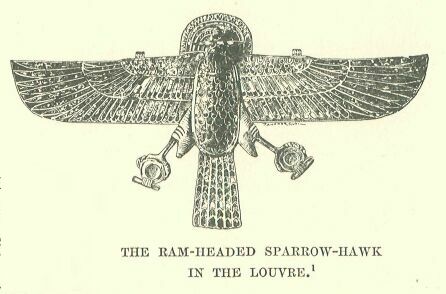

347.jpg the Ram-headed Sparrow-hawk in The Louvre

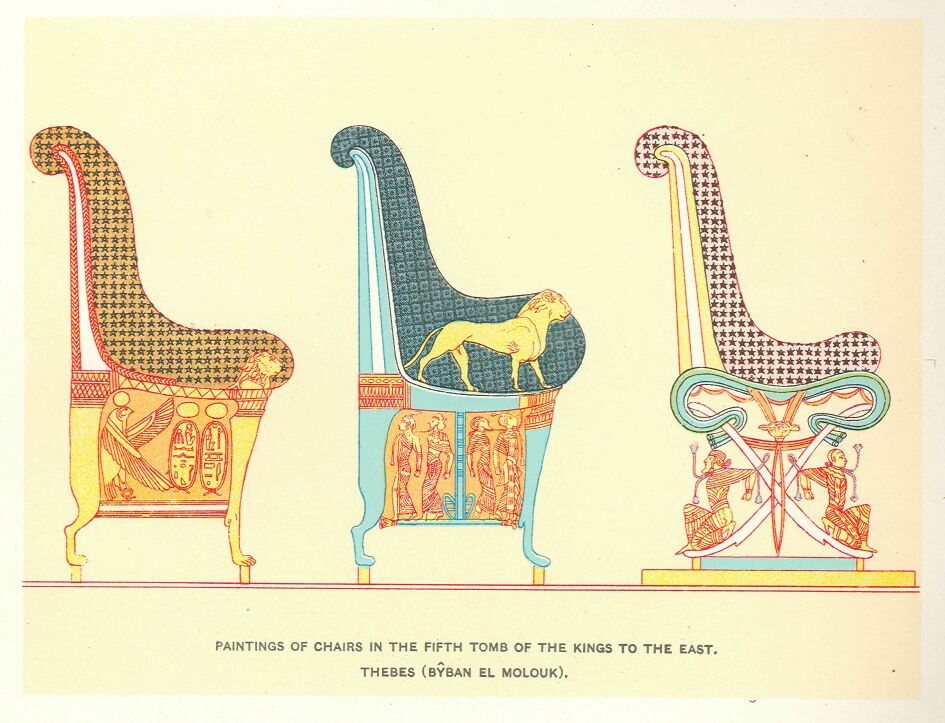

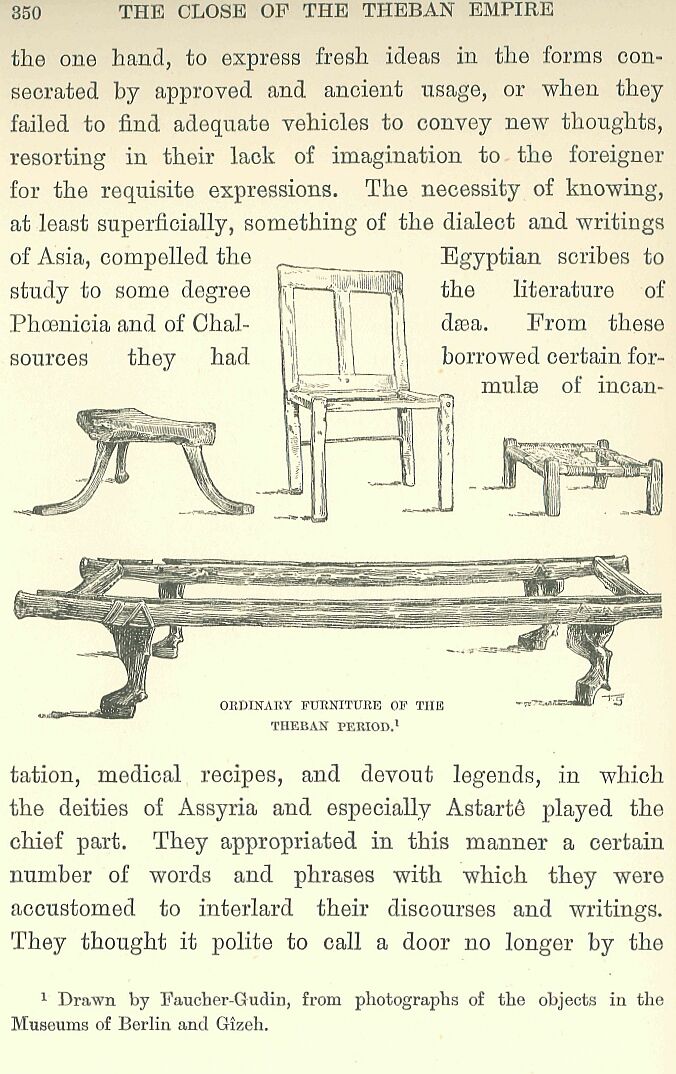

350.jpg Page Image With Furniture

Thutmosis III.: the organisation of the Syrian provinces—Amenothes III.: the royal worshippers of Atonū.

In the year XXXIV. the Egyptians reappeared in Zahi. The people of Anaugasa having revolted, two of their towns were taken, a third surrendered, while the chiefs of the Lotanū hastened to meet their lord with their usual tribute. Advantage was taken of the encampment being at the foot of the Lebanon to procure wood for building purposes, such as beams and planks, masts and yards for vessels, which were all shipped by the Kefātiu at Byblos for exportation to the Delta. This expedition was, indeed, little more than a military march through the country. It would appear that the Syrians soon accustomed themselves to the presence of the Egyptians in their midst, and their obedience henceforward could be fairly relied on. We are unable to ascertain what were the circumstances or the intrigues which, in the year XXXV., led to a sudden outbreak among the tribes settled on the Euphrates and the Orontes. The King of Mitanni rallied round him the princes of Naharaim, and awaited the attack of the Egyptians near Aruna. Thūtmosis displayed great personal courage, and the victory was at once decisive. We find mention of only ten prisoners, one hundred and eighty mares, and sixty chariots in the lists of the spoil. Anaugasa again revolted, and was subdued afresh in the year XXXVIII.; the Shaūsū rebelled in the year XXXIX., and the Lotanū or some of the tribes connected with them two years later. The campaign of the year XLII. proved more serious. Troubles had arisen in the neighbourhood of Arvad. Thūtmosis, instead of following the usual caravan route, marched along the coast-road by way of Phoenicia. He destroyed Arka in the Lebanon and the surrounding strongholds, which were the haunts of robbers who lurked in the mountains; then turning to the northeast, he took Tunipa and extorted the usual tribute from the inhabitants of Naharaim. On the other hand, the Prince of Qodshū, trusting to the strength of his walled city, refused to do homage to the Pharaoh, and a deadly struggle took place under the ramparts, in which each side availed themselves of all the artifices which the strategic warfare of the times allowed. On a day when the assailants and besieged were about to come to close quarters, the Amorites let loose a mare among the chariotry of Thūtmosis. The Egyptian horses threatened to become unmanageable, and had begun to break through the ranks, when Amenemhabī, an officer of the guard, leaped to the ground, and, running up to the creature, disembowelled it with a thrust of his sword; this done, he cut off its tail and presented it to the king. The besieged were eventually obliged to shut themselves within their newly built walls, hoping by this means to tire out the patience of their assailants; but a picked body of men, led by the same brave Amenemhabī who had killed the mare, succeeded in making a breach and forcing an entrance into the town. Even the numerous successful campaigns we have mentioned, form but a part, though indeed an important part, of the wars undertaken by Thūtmosis to “fix his frontiers in the ends of the earth.” Scarcely a year elapsed without the viceroy of Ethiopia having a conflict with one or other of the tribes of the Upper Nile; little merit as he might gain in triumphing over such foes, the spoil taken from them formed a considerable adjunct to the treasure collected in Syria, while the tributes from the people of Kūsh and the Uaūaīū were paid with as great regularity as the taxes levied on the Egyptians themselves. It comprised gold both from the mines and from the rivers, feathers, oxen with curiously trained horns, giraffes, lions, leopards, and slaves of all ages. The distant regions explored by Hātshopsītū continued to pay a tribute at intervals. A fleet went to Pūanīt to fetch large cargoes of incense, and from time to time some Ilīm chief would feel himself honoured by having one of his daughters accepted as an inmate of the harem of the great king. After the year XLII. we have no further records of the reign, but there is no reason to suppose that its closing years were less eventful or less prosperous than the earlier. Thūtmosis III., when conscious of failing powers, may have delegated the direction of his armies to his sons or to his generals, but it is also quite possible that he kept the supreme command in his own hands to the end of his days. Even when old age approached and threatened to abate his vigour, he was upheld by the belief that his father Amon was ever at hand to guide him with his counsel and assist him in battle. “I give to thee, declared the god, the rebels that they may fall beneath thy sandals, that thou mayest crush the rebellious, for I grant to thee by decree the earth in its length and breadth. The tribes of the West and those of the East are under the place of thy countenance, and when thou goest up into all the strange lands with a joyous heart, there is none who will withstand Thy Majesty, for I am thy guide when thou treadest them underfoot. Thou hast crossed the water of the great curve of Naharaim* in thy strength and in thy power, and I have commanded thee to let them hear thy roaring which shall enter their dens, I have deprived their nostrils of the breath of life, I have granted to thee that thy deeds shall sink into their hearts, that my uraeus which is upon thy head may burn them, that it may bring prisoners in long files from the peoples of Qodi, that it may consume with its flame those who are in the marshes,** that it may cut off the heads of the Asiatics without one of them being able to escape from its clutch. I grant to thee that thy conquests may embrace all lands, that the urseus which shines upon my forehead may be thy vassal, so that in all the compass of the heaven there may not be one to rise against thee, but that the people may come bearing their tribute on their backs and bending before Thy Majesty according to my behest; I ordain that all aggressors arising in thy time shall fail before thee, their heart burning within them, their limbs trembling!”

* The Euphrates, in the great curve described by it across

Naharaim, after issuing from the mountains of Cilicia.

** The meaning is doubtful. The word signifies pools,

marshes, the provinces situated beyond Egyptian territory,

and consequently the distant parts of the world—those which

are nearest the ocean which encircles the earth, and which

was considered as fed by the stagnant waters of the

celestial Nile, just as the extremities of Egypt were

watered by those of the terrestrial Nile.

“I.—I am come that I may grant unto thee to crush the great ones of Zahi, I throw them under thy feet across their mountains,—I grant to thee that they shall see Thy Majesty as a lord of shining splendour when thou shinest before them in my likeness!

“II.—I am come, to grant thee that thou mayest crush those of the country of Asia, to break the heads of the people of Lotanū,—I grant thee that they may see Thy Majesty, clothed in thy panoply, when thou seizest thy arms, in thy war-chariot.

“III.—I am come, to grant thee that thou mayest crush the land of the East, and invade those who dwell in the provinces of Tonūtir,—I grant that they may see Thy Majesty as the comet which rains down the heat of its flame and sheds its dew.

“IV.—I am come, to grant thee that thou mayest crush the land of the West, so that Kafīti and Cyprus shall be in fear of thee,—I grant that they may see Thy Majesty like the young bull, stout of heart, armed with horns which none may resist.

“V.—I am come, to grant thee that thou mayest crush those who are in their marshes, so that the countries of Mitanni may tremble for fear of thee,—I grant that they may see Thy Majesty like the crocodile, lord of terrors, in the midst of the water, which none can approach.

“VI.—I am come, to grant thee that thou mayest crush those who are in the isles, so that the people who live in the midst of the Very-Green may be reached by thy roaring,—I grant that they may see Thy Majesty like an avenger who stands on the back of his victim.

“VII.—I am come, to grant that thou mayest crush the Tihonu, so that the isles of the Utanātiū may be in the power of thy souls,—I grant that they may see Thy Majesty like a spell-weaving lion, and that thou mayest make corpses of them in the midst of their own valleys.*

“VIII.—I am come, to grant thee that thou mayest crush the ends of the earth, so that the circle which surrounds the ocean may be grasped in thy fist,—I grant that they may see Thy Majesty as the sparrow-hawk, lord of the wing, who sees at a glance all that he desires.

“IX.—I am come, to grant thee that thou mayest crush the peoples who are in their “duars,” so that thou mayest bring the Hirū-shāītū into captivity,—I grant that they may see Thy Majesty like the jackal of the south, lord of swiftness, the runner who prowls through the two lands.

“X.—I am come, to grant thee that thou mayest crush the nomads, so that the Nubians as far as the land of Pidīt are in thy grasp,—I grant that they may see Thy Majesty like unto thy two brothers Horus and Sit, whose arms I have joined in order to establish thy power.”

* The name of the people associated with the Tihonu was read

at first Tanau, and identified with the Danai of the Greeks.

Chabas was inclined to read Ūtena, and Brugsch, Ūthent, more

correctly Utanātiū, utanāti, the people of Uatanit. The

juxtaposition of this name with that of the Libyans compels

us to look towards the west for the site of this people: may

we assign to them the Ionian Islands, or even those in the

western Mediterranean.

The poem became celebrated. When Seti I., two centuries later, commanded the Poet Laureates of his court to celebrate his victories in verse, the latter, despairing of producing anything better, borrowed the finest strophes from this hymn to Thūtmosis IIL, merely changing the name of the hero. The composition, unlike so many other triumphal inscriptions, is not a mere piece of official rhetoric, in which the poverty of the subject is concealed by a multitude of common-places whether historical or mythological. Egypt indeed ruled the world, either directly or through her vassals, and from the mountains of Abyssinia to those of Cilicia her armies held the nations in awe with the threat of the Pharaoh.

The conqueror, as a rule, did not retain any part of their territory. He confined himself to the appropriation of the revenue of certain domains for the benefit of his gods.* Amon of Karnak thus became possessor of seven Syrian towns which he owed to the generosity of the victorious Pharaohs.**

* The seven towns which Amon possessed in Syria are

mentioned, in the time of Ramses III., in the list of the

domains and revenues of the god.

** In the year XXIII., on his return from his first

campaign, Thūtmosis III. provided offerings, guaranteed from

the three towns Anaūgasa, Inūāmū, and Hūrnikarū, for his

father Amonrā.

Certain cities, like Tunipa, even begged for statues of Thūtmosis for which they built a temple and instituted a cultus. Amon and his fellow-gods too were adored there, side by side with the sovereign the inhabitants had chosen to represent them here below.* These rites were at once a sign of servitude, and a proof of gratitude for services rendered, or privileges which had been confirmed. The princes of neighbouring regions repaired annually to these temples to renew their oaths of allegiance, and to bring their tributes “before the face of the king.” Taking everything into account, the condition of the Pharaoh’s subjects might have been a pleasant one, had they been able to accept their lot without any mental reservation. They retained their own laws, their dynasties, and their frontiers, and paid a tax only in proportion to their resources, while the hostages given were answerable for their obedience. These hostages were as a rule taken by Thūtmosis from among the sons or the brothers of the enemy’s chief. They were carried to Thebes, where a suitable establishment was assigned to them,** the younger members receiving an education which practically made them Egyptians.

* The statues of Thūtmosis III. and of the gods of Egypt

erected at Tunipa are mentioned in a letter from the

inhabitants of that town to Amenōthes III. Later, Ramses

II., speaking of the two towns in the country of the Khāti

in which were two statues of His Majesty, mentions Tunipa as

one of them.

** The various titles of the lists of Thūtmosis III. at

Thebes show us “the children of the Syrian chiefs conducted

as prisoners” into the town of Sūhanū, which is elsewhere

mentioned as the depot, the prison of the temple of Anion.

W. Max Mullcr was the first to remark the historical value

of this indication, but without sufficiently insisting on

it; the name indicates, perhaps, as he says, a great prison,

but a prison like those where the princes of the family of

the Ottoman sultans were confined by the reigning monarch—

a palace usually provided with all the comforts of Oriental

life.

As soon as a vacancy occurred in the succession either in Syria or in Ethiopia, the Pharaoh would choose from among the members of the family whom he held in reserve, that prince on whose loyalty he could best count, and placed him upon the throne.* The method of procedure was not always successful, since these princes, whom one would have supposed from their training to have been the least likely to have asserted themselves against the man to whom they owed their elevation, often gave more trouble than others. The sense of the supreme power of Egypt, which had been inculcated in them during their exile, seemed to be weakened after their return to their native country, and to give place to a sense of their own importance. Their hearts misgave them as the time approached for them to send their own children as pledges to their suzerain, and also when called upon to transfer a considerable part of their revenue to his treasury. They found, moreover, among their own cities and kinsfolk, those who were adverse to the foreign yoke, and secretly urged their countrymen to revolt, or else competitors for the throne who took advantage of the popular discontent to pose as champions of national independence, and it was difficult for the vassal prince to counteract the intrigues of these adversaries without openly declaring himself hostile to his foreign master.**

* Among the Tel el-Amarna tablets there is a letter of a

petty Syrian king, Adadnirari, whose father was enthroned

after a fashion in Nūkhassi by Thūtmosis III.

** Thus, in the Tel el-Amarna correspondence, Zimrida,

governor of Sidon, gives information to Amenōthes III. on

the intrigues which the notables of the town were concocting

against Egyptian authority. Ribaddū relates in one of these

despatches that the notables of Byblos and the women of his

harem were urging him to revolt; later, a letter of Amūnirā

to the King of Egypt informs us that Ribaddū had been driven

from Byblos by his own brother.

A time quickly came when a vestige of fear alone constrained them to conceal their wish for liberty; the most trivial incident then sufficed to give them the necessary encouragement, and decided them to throw off the mask, a repulse or the report of a repulse suffered by the Egyptians, the news of a popular rising in some neighbouring state, the passing visit of a Chaldęan emissary who left behind him the hope of support and perhaps of subsidies from Babylon, and the unexpected arrival of a troop of mercenaries whose services might be hired for the occasion.* A rising of this sort usually brought about the most disastrous results. The native prince or the town itself could keep back the tribute and own allegiance to no one during the few months required to convince Pharaoh of their defection and to allow him to prepare the necessary means of vengeance; the advent of the Egyptians followed, and the work of repression was systematically set in hand. They destroyed the harvests, whether green or ready for the sickle, they cut down the palms and olive trees, they tore up the vines, seized on the flocks, dismantled the strongholds, and took the inhabitants prisoners.**

* Būrnabūriash, King of Babylon, speaks of Syrian agents who

had come to ask for support from his father, Kūrigalzū, and

adds that the latter had counselled submission. In one of

the letters preserved in the British Museum, Azīrū defends

himself for having received an emissary of the King of the

Khāti.

** Cf. the raiding, for instance, of the regions of Arvad

and of the Zahi by Thūtmosis III., described in the Annals,

11. 4, 5. We are still in possession of the threats which

the messenger Khāni made against the rebellious chief of a

province of the Zahi—possibly Aziru.

The rebellious prince had to deliver up his silver and gold, the contents of his palace, even his children,* and when he had finally obtained peace by means of endless sacrifices, he found himself a vassal as before, but with an empty treasury, a wasted country, and a decimated people.

* See, in the accounts of the campaigns of Thūtmosis, the

record of the spoils, as well as the mention of the children

of the chiefs brought as prisoners into Egypt.

Drawn by Boudier, from a photograph by Gayet.

In spite of all this, some head-strong native princes never relinquished the hope of freedom, and no sooner had they made good the breaches in their walls as far as they were able, than they entered once more on this unequal contest, though at the risk of bringing irreparable disaster on their country. The majority of them, after one such struggle, resigned themselves to the inevitable, and fulfilled their feudal obligations regularly. They paid their fixed contribution, furnished rations and stores to the army when passing through their territory, and informed the ministers at Thebes of any intrigues among their neighbours.* Years elapsed before they could so far forget the failure of their first attempt to regain independence, as to venture to make a second, and expose themselves to fresh reverses.

The administration of so vast an empire entailed but a small expenditure on the Egyptians, and required the offices of merely a few functionaries.** The garrisons which they kept up in foreign provinces lived on the country, and were composed mainly of light troops, archers, a certain proportion of heavy infantry, and a few minor detachments of chariotry dispersed among the principal fortresses.***

* We find in the Annals, in addition to the enumeration of

the tributes, the mention of the foraging arrangements which

the chiefs were compelled to make for the army on its

passage. We find among the tablets letters from Aziru

denouncing the intrigues of the Khāti; letters also of

Ribaddu pointing out the misdeeds of Abdashirti, and other

communications of the same nature, which demonstrate the

supervision exercised by the petty Syrian princes over each

other.

** Under Thūtmosis III. we have among others “Mir,” or “Nasi

sītū mihātītū,” “governors of the northern countries,” the

Thūtīi who became afterwards a hero of romance. The

individuals who bore this title held a middle rank in the

Egyptian hierarchy.

*** The archers—pidātid, pidāti, pidāte—and the

chariotry quartered in Syria are often mentioned in the Tel

el-Amarna correspondence. Steindorff has recognised the term

-ddū aūītū, meaning infantry, in the word ūeū, ūiū, of the

Tel el-Amarna tablets.

The officers in command had orders to interfere as little as possible in local affairs, and to leave the natives to dispute or even to fight among themselves unhindered, so long as their quarrels did not threaten the security of the Pharaoh.* It was never part of the policy of Egypt to insist on her foreign subjects keeping an unbroken peace among themselves. If, theoretically, she did not recognise the right of private warfare, she at all events tolerated its practice. It mattered little to her whether some particular province passed out of the possession of a certain Eibaddū into that of a certain Azīru, or vice versa, so long as both Eibaddū and Azīru remained her faithful slaves. She never sought to repress their incessant quarrelling until such time as it threatened to take the form of an insurrection against her own power. Then alone did she throw off her neutrality; taking the side of one or other of the dissentients, she would grant him, as a pledge of help, ten, twenty, thirty, or even more archers.**

* A half at least of the Tel el-Amarna correspondence treats

of provincial wars between the kings of towns and countries

subject to Egypt—wars of Abdashirti and his son Azīru

against the cities of the Phoenician coast, wars of

Abdikhiba, or Abdi-Tabba, King of Jerusalem, against the

chiefs of the neighbouring cities.

** Abimilki (Abisharri) demands on one occasion from the

King of Egypt ten men to defend Tyre, on another occasion

twenty; the town of Gula requisitioned thirty or forty to

guard it. Delattre thinks that these are rhetorical

expressions answering to a general word, just as if we

should say “a handful of men”; the difference of value in

the figures is to me a proof of their reality.

No doubt the discipline and personal courage of these veterans exercised a certain influence on the turn of events, but they were after all a mere handful of men, and their individual action in the combat would scarcely ever have been sufficient to decide the result; the actual importance of their support, in spite of their numerical inferiority, lay in the moral weight they brought to the side on which they fought, since they represented the whole army of the Pharaoh which lay behind them, and their presence in a camp always ensured final success. The vanquished party had the right of appeal to the sovereign, through whom he might obtain a mitigation of the lot which his successful adversary had prepared for him; it was to the interest of Egypt to keep the balance of power as evenly as possible between the various states which looked to her, and when she prevented one or other of the princes from completely crushing his rivals, she was minimising the danger which might soon arise from the vassal whom she had allowed to extend his territory at the expense of others.

These relations gave rise to a perpetual exchange of letters and petitions between the court of Thebes and the northern and southern provinces, in which all the petty kings of Africa and Asia, of whatever colour or race, set forth, either openly or covertly, their ambitions and their fears, imploring a favour or begging for a subsidy, revealing the real or suspected intrigues of their fellow-chiefs, and while loudly proclaiming their own loyalty, denouncing the perfidy and the secret projects of their neighbours. As the Ethiopian peoples did not, apparently, possess an alphabet of their own, half of the correspondence which concerned them was carried on in Egyptian, and written on papyrus. In Syria, however, where Babylonian civilization maintained itself in spite of its conquest by Thūtmosis, cuneiform writing was still employed, and tablets of dried clay.* It had, therefore, been found necessary to establish in the Pharaoh’s palace a department for this service, in which the scribes should be competent to decipher the Chaldęan character. Dictionaries and easy mythological texts had been procured for their instruction, by means of which they had learned the meaning of words and the construction of sentences. Having once mastered the mechanism of the syllabary, they set to work to translate the despatches, marking on the back of each the date and the place from whence it came, and if necessary making a draft of the reply.** In these the Pharaoh does not appear, as a rule, to have insisted on the endless titles which we find so lavishly used in his inscriptions, but the shortened protocol employed shows that the theory of his divinity was as fully acknowledged by strangers as it was by his own subjects. They greet him as their sun, the god before whom they prostrate themselves seven times seven, while they are his slaves, his dogs, and the dust beneath his feet.***

* A discovery made by the fellahīn, in 1887, at Tel el-

Arnarna, in the rums of the palace of Khūniaton, brought to

light a portion of the correspondence between Asiatic

monarchs, whether vassals or independent of Egypt, with the

officers of Amenōthes III. and IV., and with these Pharaohs

themselves.

** Several of these registrations are still to be read on

the backs of the tablets at Berlin, London, and Gīzeh.

***The protocols of the letters of Abdashirti may be taken

as an example, or those of Abimilki to Pharaoh, sometimes

there is a development of the protocol which assumes

panegyrical features similar to those met with in Egypt.

The runners to whom these documents were entrusted, and who delivered them with their own hand, were not, as a rule, persons of any consideration; but for missions of grave importance “the king’s messengers” were employed, whose functions in time became extended to a remarkable degree. Those who were restricted to a limited sphere of activity were called “the king’s messengers for the regions of the south,” or “the king’s messengers for the regions of the north,” according to their proficiency in the idiom and customs of Africa or of Asia. Others were deemed capable of undertaking missions wherever they might be required, and were, therefore, designated by the bold title of “the king’s messengers for all lands.” In this case extended powers were conferred upon them, and they were permitted to cut short the disputes between two cities in some province they had to inspect, to excuse from tribute, to receive presents and hostages, and even princesses destined for the harem of the Pharaoh, and also to grant the support of troops to such as could give adequate reason for seeking it.* Their tasks were always of a delicate and not infrequently of a perilous nature, and constantly exposed them to the danger of being robbed by highwaymen or maltreated by some insubordinate vassal, at times even running the risk of mutilation or assassination by the way.**

* The Tel el-Amarna correspondence shows the messengers in

the time of Amenōthes III. and IV. as receiving tribute, as

bringing an army to the succour of a chief in difficulties,

as threatening with the anger of the Pharaoh the princes o£

doubtful loyalty, as giving to a faithful vassal compliments

and honours from his suzerain, as charged with the

conveyance of a gift of slaves, or of escorting a princess

to the harem of the Pharaoh.

** A letter of Ribaddu, in the time of Amenōthes III.,

represents a royal messenger as blockaded in By bios by the

rebels.

They were obliged to brave the dangers of the forests of Lebanon and of the Taurus, the solitudes of Mesopotamia, the marshes of Chaldoa, the voyages to Pūanīt and Asia Minor. Some took their way towards Assyria and Babylon, while others embarked at Tyre or Sidon for the islands of the Ęgean Archipelago.* The endurance of all these officers, whether governors or messengers, their courage, their tact, the ready wit they were obliged to summon to help them out of the difficulties into which their calling frequently brought them, all tended to enlist the public sympathy in their favour.**

* We hear from the tablets of several messengers to Babylon,

and the Mitanni, Rasi, Mani, Khamassi. The royal messenger

Thūtīi, who governed the countries of the north, speaks of

having satisfied the heart of the king in “the isles which

are in the midst of the sea.” This was not, as some think, a

case of hyperbole, for the messengers could embark on

Phoenician vessels; they had a less distance to cover in

order to reach the Ęgean than the royal messenger of Queen

Hātshopsītū had before arriving at the country of the

Somalis and the “Ladders of Incense.”

** The hero of the Anastasi Papyrus, No. 1, with whom

Chabas made us acquainted in his Voyage d’un Égyptien, is

probably a type of the “messenger” or the time of Ramses

II.; in any case, his itinerary and adventures are natural

to a “royal messenger” compelled to traverse Syria alone.

Many of them achieved a reputation, and were made the heroes of popular romance. More than three centuries after it was still related how one of them, by name Thūtīi, had reduced and humbled Jaffa, whose chief had refused to come to terms. Thūtīi set about his task by feigning to throw off his allegiance to Thūtmosis III., and withdrew from the Egyptian service, having first stolen the great magic wand of his lord; he then invited the rebellious chief into his camp, under pretence of showing him this formidable talisman, and killed him after they had drunk together. The cunning envoy then packed five hundred of his soldiers into jars, and caused them to be carried on the backs of asses before the gates of the town, where he made the herald of the murdered prince proclaim that the Egyptians had been defeated, and that the pack train which accompanied him contained the spoil, among which was Thūtīi himself. The officer in charge of the city gate was deceived by this harangue, the asses were admitted within the walls, where the soldiers quitted their jars, massacred the garrison, and made themselves masters of the town. The tale is, in the main, the story of Ali Baba and the forty thieves.

The frontier was continually shifting, and Thūtmosis III., like Thūtmosis I., vainly endeavoured to give it a fixed character by erecting stelas along the banks of the Euphrates, at those points where he contended it had run formerly. While Kharu and Phoenicia were completely in the hands of the conqueror, his suzerainty became more uncertain as it extended northwards in the direction of the Taurus. Beyond Qodshū, it could only be maintained by means of constant supervision, and in Naharaim its duration was coextensive with the sojourn of the conqueror in the locality during his campaign, for it vanished of itself as soon as he had set out on his return to Africa. It will be thus seen that, on the continent of Asia, Egypt possessed a nucleus of territories, so far securely under her rule that they might be actually reckoned as provinces; beyond this immediate domain there was a zone of waning influence, whose area varied with each reign, and even under one king depended largely on the activity which he personally displayed.

This was always the case when the rulers of Egypt attempted to carry their supremacy beyond the isthmus; whether under the Ptolemies or the native kings, the distance to which her influence extended was always practically the same, and the teaching of history enables us to note its limits on the map with relative accuracy.*

* The development of the Egyptian navy enabled the Ptolemies

to exercise authority over the coasts of Asia Minor and of

Thrace, but this extension of their power beyond the

indicated limits only hastened the exhaustion of their

empire. This instance, like that of Mehemet Ali, thus

confirms the position taken up in the text.

The coast towns, which were in maritime communication with the ports of the Delta, submitted to the Egyptian yoke more readily than those of the interior. But this submission could not be reckoned on beyond Berytus, on the banks of the Lykos, though occasionally it stretched a little further north as far as Byblos and Arvad; even then it did not extend inland, and the curve marking its limits traverses Coele-Syria from north-west to south-east, terminating at Mount Hermon. Damascus, securely entrenched behind Anti-Lebanon, almost always lay outside this limit. The rulers of Egypt generally succeeded without much difficulty in keeping possession of the countries lying to the south of this line; it demanded merely a slight effort, and this could be furnished for several centuries without encroaching seriously on the resources of the country, or endangering its prosperity. When, however, some province ventured to break away from the control of Egypt, the whole mechanism of the government was put into operation to provide soldiers and the necessary means for an expedition. Each stage of the advance beyond the frontier demanded a greater expenditure of energy, which, with prolonged distances, would naturally become exhausted. The expedition would scarcely have reached the Taurus or the Euphrates, before the force of circumstances would bring about its recall homewards, leaving but a slight bond of vassalage between the recently subdued countries and the conqueror, which would speedily be cast off or give place to relations dictated by interest or courtesy. Thūtmosis III. had to submit to this sort of necessary law; a further extension of territory had hardly been gained when his dominion began to shrink within the frontiers that appeared to have been prescribed by nature for an empire like that of Egypt. Kharū and Phoenicia proper paid him their tithes with due regularity; the cities of the Amurru and of Zahi, of Damascus, Qodshū, Hamath, and even of Tunipa, lying on the outskirts of these two subject nations, formed an ill-defined borderland, kept in a state of perpetual disturbance by the secret intrigues or open rebellions of the native princes. The kings of Alasia, Naharaim, and Mitanni preserved their independence in spite of repeated reverses, and they treated with the conqueror on equal terms.*

* The difference of tone between the letters of these kings

and those of the other princes, as well as the consequences

arising from it, has been clearly defined by Delattre.

The tone of their letters to the Pharaoh, the polite formulas with which they addressed him, the special protocol which the Egyptian ministry had drawn up for their reply, all differ widely from those which we see in the despatches coming from commanders of garrisons or actual vassals. In the former it is no longer a slave or a feudatory addressing his master and awaiting his orders, but equals holding courteous communication with each other, the brother of Alasia or of Mitanni with his brother of Egypt. They inform him of their good health, and then, before entering on business, they express their good wishes for himself, his wives, his sons, the lords of his court, his brave soldiers, and for his horses. They were careful never to forget that with a single word their correspondent could let loose upon them a whirlwind of chariots and archers without number, but the respect they felt for his formidable power never degenerated into a fear which would humiliate them before him with their faces in the dust.

This interchange of diplomatic compliments was called for by a variety of exigencies, such as incidents arising on the frontier, secret intrigues, personal alliances, and questions of general politics. The kings of Mesopotamia and of Northern Syria, even those of Assyria and Chaldęa, who were preserved by distance from the dangers of a direct invasion, were in constant fear of an unexpected war, and heartily desired the downfall of Egypt; they endeavoured meanwhile to occupy the Pharaoh so fully at home that he had no leisure to attack them. Even if they did not venture to give open encouragement to the disposition in his subjects to revolt, they at least experienced no scruple in hiring emissaries who secretly fanned the flame of discontent. The Pharaoh, aroused to indignation by such plotting, reminded them of their former oaths and treaties. The king in question would thereupon deny everything, would speak of his tried friendship, and recall the fact that he had refused to help a rebel against his beloved brother.* These protestations of innocence were usually accompanied by presents, and produced a twofold effect. They soothed the anger of the offended party, and suggested not only a courteous answer, but the sending of still more valuable gifts. Oriental etiquette, even in those early times, demanded that the present of a less rich or powerful friend should place the recipient under the obligation of sending back a gift of still greater worth. Every one, therefore, whether great or little, was obliged to regulate his liberality according to the estimation in which he held himself, or to the opinion which others formed of him, and a personage of such opulence as the King of Egypt was constrained by the laws of common civility to display an almost boundless generosity: was he not free to work the mines of the Divine Land or the diggings of the Upper Nile; and as for gold, “was it not as the dust of his country”?**

* See the letter of Amenōthes III. to Kallimmasin of

Babylon, where the King of Egypt complains of the inimical

designs which the Babylonian messengers had planned against

him, and of the intrigues they had connected on their return

to their own country; see also the letter from Burnaburiash

to Amenōthes IV., in which he defends himself from the

accusation of having plotted against the King of Egypt at

any time, and recalls the circumstance that his father

Kurigalzu had refused to encourage the rebellion of one of

the Syrian tribes, subjects of Amenōthes III.

** See the letter of Dushratta, King of Mitanni, to the

Pharaoh Amenōthes IV.

He would have desired nothing better than to exhibit such liberality, had not the repeated calls on his purse at last constrained him to parsimony; he would have been ruined, and Egypt with him, had he given all that was expected of him. Except in a few extraordinary cases, the gifts sent never realised the expectations of the recipients; for instance, when twenty or thirty pounds of precious metal were looked for, the amount despatched would be merely two or three. The indignation of these disappointed beggars and their recriminations were then most amusing: “From the time when my father and thine entered into friendly relations, they loaded each other with presents, and never waited to be asked to exchange amenities;* and now my brother sends me two minas of gold as a gift! Send me abundance of gold, as much as thy father sent, and even, for so it must be, more than thy father.” ** Pretexts were never wanting to give reasonable weight to such demands: one correspondent had begun to build a temple or a palace in one of his capitals,*** another was reserving his fairest daughter for the Pharaoh, and he gave him to understand that anything he might receive would help to complete the bride’s trousseau.****

* Burnaburiash complains that the king’s messengers had only

brought him on one occasion two minas of gold, on another

occasion twenty minas; moreover, that the quality of the

metal was so bad that hardly five minas of pure gold could

be extracted from it.

** Literally, “and they would never make each other a fair

request.” The meaning I propose is doubtful, but it appears

to be required by the context. The letter from which this

passage was taken is from Burnaburiash, King of Babylon, to

Amenōthes IV.

*** This is the pretext advanced by Burnaburiash in the

letter just cited.

**** This seems to have been the motive in a somewhat

embarrassing letter which Dushratta, King of Mitanni, wrote

to the Pharaoh Amenōthes III. on the occasion of his fixing

the dowry of his daughter.

The princesses thus sent from Babylon or Mitanni to the court of Thebes enjoyed on their arrival a more honourable welcome, and were assigned a more exalted rank than those who came from Kharū and Phoenicia. As a matter of fact, they were not hostages given over to the conqueror to be disposed of at will, but queens who were united in legal marriage to an ally.* Once admitted to the Pharaoh’s court, they retained their full rights as his wife, as well as their own fortune and mode of life. Some would bring to their betrothed chests of jewels, utensils, and stuffs, the enumeration of which would cover both sides of a large tablet; others would arrive escorted by several hundred slaves or matrons as personal attendants.** A few of them preserved their original name,*** many assumed an Egyptian designation,**** and so far adapted themselves to the costumes, manners, and language of their adopted country, that they dropped all intercourse with their native land, and became regular Egyptians.

* The daughter of the King of the Khāti, wife of Ramses IL,

was treated, as we see from the monuments, with as much

honour as would have been accorded to Egyptian princesses of

pure blood.

** Gilukhipa, who was sent to Egypt to become the wife of

Amenōthes III., took with her a company of three hundred and

seventy women for her service. She was a daughter of

Sutarna, King of Mitanni, and is mentioned several times in

the Tel el-Amarna correspondence.

*** For example, Gilukhipa, whose name is transcribed

Kilagīpa in Egyptian, and another princess of Mitanni, niece

of Gilukhipa, called Tadu-khīpa, daughter of Dushratta and

wife of Amenōthes IV.

**** The prince of the Khāti’s daughter who married Ramses

II. is an example; we know her only by her Egyptian name

Māītnofīrūrī. The wife of Ramses III. added to the Egyptian

name of Isis her original name, Humazarati.

When, after several years, an ambassador arrived with greetings from their father or brother, he would be puzzled by the changed appearance of these ladies, and would almost doubt their identity: indeed, those only who had been about them in childhood were in such cases able to recognise them.* These princesses all adopted the gods of their husbands,** though without necessarily renouncing their own. From time to time their parents would send them, with much pomp, a statue of one of their national divinities—Ishtar, for example—which, accompanied by native priests, would remain for some months at the court.***

* This was the case with the daughter of Kallimmasin, King

of Babylon, married to Amenōthes III.; her father’s

ambassador did not recognise her.

** The daughter of the King of the Khāti, wife of Ramses

II., is represented in an attitude of worship before her

deified husband and two Egyptian gods.

*** Dushratta of Mitanni, sending a statue of Ishtar to his

daughter, wife of Amenōthes III., reminds her that the same

statue had already made the voyage to Egypt in the time of

his father Sutarna.

The children of these queens ranked next in order to those whose mothers belonged to the solar race, but nothing prevented them marrying their brothers or sisters of pure descent, and being eventually raised to the throne. The members of their families who remained in Asia were naturally proud of these bonds of close affinity with the Pharaoh, and they rarely missed an opportunity of reminding him in their letters that they stood to him in the relationship of brother-in-law, or one of his fathers-in-law; their vanity stood them in good stead, since it afforded them another claim on the favours which they were perpetually asking of him.*

* Dushratta of Mitanni never loses an opportunity of calling

Aoienōthes III., husband of his sister Gilukhīpa, and of one

of his daughters, “akhiya,” my brother, and “khatani-ya,” my

son-in-law.

These foreign wives had often to interfere in some of the contentions which were bound to arise between two States whose subjects were in constant intercourse with one another. Invasions or provincial wars may have affected or even temporarily suspended the passage to and from of caravans between the countries of the Tigris and those of the Nile; but as soon as peace was re-established, even though it were the insecure peace of those distant ages, the desert traffic was again resumed and carried on with renewed vigour. The Egyptian traders who penetrated into regions beyond the Euphrates, carried with them, and almost unconsciously disseminated along the whole extent of their route, the numberless products of Egyptian industry, hitherto but little known outside their own country, and rendered expensive owing to the difficulty of transmission or the greed of the merchants. The Syrians now saw for the first time in great quantities, objects which had been known to them hitherto merely through the few rare specimens which made their way across the frontier: arms, stuffs, metal implements, household utensils—in fine, all the objects which ministered to daily needs or to luxury. These were now offered to them at reasonable prices, either by the hawkers who accompanied the army or by the soldiers themselves, always ready, as soldiers are, to part with their possessions in order to procure a few extra pleasures in the intervals of fighting.

Drawn by Boudier, from a photograph by Insinger. The scene

here reproduced occurs in most of the Theban tombs of the

XVIIII. dynasty.

On the other hand, whole convoys of spoil were despatched to Egypt after every successful campaign, and their contents were distributed in varying proportions among all classes of society, from the militiaman belonging to some feudal contingent, who received, as a reward of his valour, some half-dozen necklaces or bracelets, to the great lord of ancient family or the Crown Prince, who carried off waggon-loads of booty in their train. These distributions must have stimulated a passion for all Syrian goods, and as the spoil was insufficient to satisfy the increasing demands of the consumer, the waning commerce which had been carried on from early times was once more revived and extended, till every route, whether by land or water, between Thebes, Memphis, and the Asiatic cities, was thronged by those engaged in its pursuit. It would take too long to enumerate the various objects of merchandise brought in almost daily to the marts on the Nile by Phoenician vessels or the owners of caravans. They comprised slaves destined for the workshop or the harem,* Hittite bulls and stallions, horses from Singar, oxen from Alasia, rare and curious animals such as elephants from Nīi, and brown bears from the Lebanon,** smoked and salted fish, live birds of many-coloured plumage, goldsmiths’work*** and precious stones, of which lapis-lazuli was the chief.

* Syrian slaves are mentioned along with Ethiopian in the

Anastasi Papyrus, No. 1, and there is mention in the Tel

el-Amarna correspondence of Hittite slaves whom Dushratta of

Mitanni brought to Amenōthes III., and of other presents of

the same kind made by the King of Alasia as a testimony of

his grateful homage.

** The elephant and the bear are represented on the tomb of

liakhmirī among the articles of tribute brought into Egypt.

*** The Annals of Thutmosis III. make a record in each

campaign of the importation of gold and silver vases,

objects in lapis-lazuli and crystal, or of blocks of the

same materials; the Theban tombs of this period afford

examples of the vases and blocks brought by the Syrians. The

Tel el-Amarna letters also mention vessels of gold or blocks

of precious stone sent as presents or as objects of exchange

to the Pharaoh by the King of Babylon, by the King of

Mitanni, by the King of the Hittites, and by other princes.

The lapis-lazuli of Babylon, which probably came from

Persia, was that which was most prized by the Egyptians on

account of the golden sparks in it, which enhanced the blue

colour; this is, perhaps, the Uknu of the cuneiform

inscriptions, which has been read for a long time as

“crystal.”

Wood for building or for ornamental work—pine,cypress, yew, cedar, and oak,* musical instruments,** helmets, leathern jerkins covered with metal scales, weapons of bronze and iron,*** chariots,**** dyed and embroidered stuffs,^ perfumes,^^ dried cakes, oil, wines of Kharū, liqueurs from Alasia, Khāti, Singar, Naharaim, Amurru, and beer from Qodi.^^^

* Building and ornamental woods are often mentioned in the

inscriptions of Thūtmosis III. A scene at Karnak represents

Seti I. causing building-wood to be cut in the region of the

Lebanon. A letter of the King of Alasia speaks of

contributions of wood which several of his subjects had to

make to the King of Egypt.

** Some stringed instruments of music, and two or three

kinds of flutes and flageolets, are designated in Egyptian

by names borrowed from some Semitic tongue—a fact which

proves that they were imported; the wooden framework of the

harp, decorated with sculptured heads of Astartō, figures

among the objects coming from Syria in the temple of the

Theban Anion.

*** Several names of arms borrowed from some Semitic dialect

have been noticed in the texts of this period. The objects

as well as the words must have been imported into Egypt,

e.g. the quiver, the sword and javelins used by the

charioteers. Cuirasses and leathern jerkins are mentioned in

the inscriptions of Thūtmosis III.

**** Chariots plated with gold and silver figure frequently

among the spoils of Thūtmosis III.: the Anastasi Papyrus,

No. 1, contains a detailed description of Syrian chariots—

Markabūti—with a reference to the localities whore certain

parts of them were made;—the country of the Amurru, that of

Aūpa, the town of Pahira. The Tel el-Amarna correspondence

mentions very frequently chariots sent to the Pharaoh by the

King of Babylon, either as presents or to be sold in Egypt;

others sent by the King of Alasia and by the King of

Mitanni.

^ Some linen, cotton, or woollen stuffs are mentioned in the

Anastasi Papyrus, No. 4, and elsewhere as coming from

Syria. The Egyptian love of white linen always prevented

their estimating highly the coloured and brocaded stuffs of

Asia; and one sees nowhere, in the representations, any

examples of stuffs of such origin, except on furniture or in

ships equipped with something of the kind in the form of

sails.

^^ The perfumed oils of Syria are mentioned in a general way

in the Anastasi Papyrus, No. 1; the King of Alasia speaks

of essences which he is sending to Amenōthes III.; the King

of Mitanni refers to bottles of oil which he is forwarding

to Gilukhīpa and to Tii.

^^^ A list of cakes of Syrian origin is found in the

Anastasi Papyrus, No. 1; also a reference to balsamic oils

from Naharaim, and to various oils which had arrived in the

ports of the Delta, to the wines of Syria, to palm wine and

various liqueurs manufactured in Alasia, in Singar, among

the Khāti, Amorites, and the people of. Tikhisa; finally, to

the beer of Qodi.

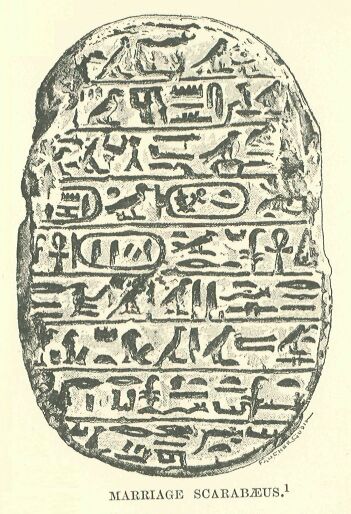

Drawn by Faucher-Gudin, from a photograph of Prisse

d’Avennes’ sketch.

On arriving at the frontier, whether by sea or by land, the majority of these objects had to pay the custom dues which were rigorously collected by the officers of the Pharaoh. This, no doubt, was a reprisal tariff, since independent sovereigns, such as those of Mitanni, Assyria, and Babylon, were accustomed to impose a similar duty on all the products of Egypt. The latter, indeed, supplied more than she received, for many articles which reached her in their raw condition were, by means of native industry, worked up and exported as ornaments, vases, and highly decorated weapons, which, in the course of international traffic, were dispersed to all four corners of the earth. The merchants of Babylon and Assyria had little to fear as long as they kept within the domains of their own sovereign or in those of the Pharaoh; but no sooner did they venture within the borders of those turbulent states which separated the two great powers, than they were exposed to dangers at every turn. Safe-conducts were of little use if they had not taken the additional precaution of providing a strong escort and carefully guarding their caravan, for the Shaūsū concealed in the depths of the Lebanon or the needy sheikhs of Kharū could never resist the temptation to rob the passing traveller.*

* The scribe who in the reign of Ramses II. composed the

Travels of an Egyptian, speaks in several places of

marauding tribes and robbers, who infested the roads

followed by the hero. The Tel el-Amarna correspondence

contains a letter from the King of Alasia, who exculpates

himself from being implicated in the harsh treatment certain

Egyptians had received in passing through his territory; and

another letter in which the King of Babylon complains that

Chaldoan merchants had been robbed at Khinnatun, in Galilee,

by the Prince of Akku (Acre) and his accomplices: one of

them had his feet cut off, and the other was still a

prisoner in Akku, and Burnaburiash demands from Amenōthes

IV. the death of the guilty persons.

The victims complained to their king, who felt no hesitation in passing on their woes to the sovereign under whose rule the pillagers were supposed to live. He demanded their punishment, but his request was not always granted, owing to the difficulties of finding out and seizing the offenders. An indemnity, however, could be obtained which would nearly compensate the merchants for the loss sustained. In many cases justice had but little to do with the negotiations, in which self-interest was the chief motive; but repeated refusals would have discouraged traders, and by lessening the facilities of transit, have diminished the revenue which the state drew from its foreign commerce.

The question became a more delicate one when it concerned the rights of subjects residing out of their native country. Foreigners, as a rule, were well received in Egypt; the whole country was open to them; they could marry, they could acquire houses and lands, they enjoyed permission to follow their own religion unhindered, they were eligible for public honours, and more than one of the officers of the crown whose tombs we see at Thebes were themselves Syrians, or born of Syrian parents on the banks of the Nile.*

* In a letter from the King of Alasia, there is question of

a merchant who had died in Egypt. Among other monuments

proving the presence of Syrians about the Pharaoh, is the

stele of Ben-Azana, of the town of Zairabizana, surnamed

Ramses-Empirī: he was surrounded with Semites like himself.

Hence, those who settled in Egypt without any intention of returning to their own country enjoyed all the advantages possessed by the natives, whereas those who took up a merely temporary abode there were more limited in their privileges. They were granted the permission to hold property in the country, and also the right to buy and sell there, but they were not allowed to transmit their possessions at will, and if by chance they died on Egyptian soil, their goods lapsed as a forfeit to the crown. The heirs remaining in the native country of the dead man, who were ruined by this confiscation, sometimes petitioned the king to interfere in their favour with a view of obtaining restitution. If the Pharaoh consented to waive his right of forfeiture, and made over the confiscated objects or their equivalent to the relatives of the deceased, it was solely by an act of mercy, and as an example to foreign governments to treat Egyptians with a like clemency should they chance to proffer a similar request.*

* All this seems to result from a letter in which the King

of Alasia demands from Amenōthes III. the restitution of the

goods of one of his subjects who had died in Egypt; the tone

of the letter is that of one asking a favour, and on the

supposition that the King of Egypt had a right to keep the

property of a foreigner dying on his territory.

It is also not improbable that the sovereigns themselves had a personal interest in more than one commercial undertaking, and that they were the partners, or, at any rate, interested in the enterprises, of many of their subjects, so that any loss sustained by one of the latter would eventually fall upon themselves. They had, in fact, reserved to themselves the privilege of carrying on several lucrative industries, and of disposing of the products to foreign buyers, either to those who purchased them out and out, or else through the medium of agents, to whom they intrusted certain quantities of the goods for warehousing. The King of Babylon, taking advantage of the fashion which prompted the Egyptians to acquire objects of Chaldęan goldsmiths’ and cabinet-makers’ art, caused ingots of gold to be sent to him by the Pharaoh, which he returned worked up into vases, ornaments, household utensils, and plated chariots. He further fixed the value of all such objects, and took a considerable commission for having acted as intermediary in the transaction.* In Alasia, which was the land of metals, the king appears to have held a monopoly of the bronze. Whether he smelted it in the country, or received it from more distant regions ready prepared, we cannot say, but he claimed and retained for himself the payment for all that the Pharaoh deigned to order of him.**

* Letter of Burnaburiash to Amenōthes IV.

** Letter from the King of Alasia to Amenōthes III., where,

whilst pretending to have nothing else in view than making a

present to his royal brother, he proposes to make an

exchange of some bronze for the products of Egypt,

especially for gold.

Drawn by Faucher-Gudin, from a photograph taken by Emil Brugsch- Bey.

From such instances we can well understand the jealous, watch which these sovereigns exercised, lest any individual connected with corporations of workmen should leave the kingdom and establish himself in another country without special permission. Any emigrant who opened a workshop and initiated his new compatriots in the technique or professional secrets of his craft, was regarded by the authorities as the most dangerous of all evil-doers. By thus introducing his trade into a rival state, he deprived his own people of a good customer, and thus rendered himself liable to the penalties inflicted on those who were guilty of treason. His savings were confiscated, his house razed to the ground, and his whole family—parents, wives, and children—treated as partakers in his crime. As for himself, if justice succeeded in overtaking him, he was punished with death, or at least with mutilation, such as the loss of eyes and ears, or amputation of the feet. This severity did not prevent the frequent occurrence of such cases, and it was found necessary to deal with them by the insertion of a special extradition clause in treaties of peace and other alliances. The two contracting parties decided against conceding the right of habitation to skilled workmen who should take refuge with either party on the territory of the other, and they agreed to seize such workmen forthwith, and mutually restore them, but under the express condition that neither they nor any of their belongings should incur any penalty for the desertion of their country. It would be curious to know if all the arrangements agreed to by the kings of those times were sanctioned, as in the above instance, by properly drawn up agreements. Certain expressions occur in their correspondence which seem to prove that this was the case, and that the relations between them, of which we can catch traces, resulted not merely from a state of things which, according to their ideas, did not necessitate any diplomatic sanction, but from conventions agreed to after some war, or entered on without any previous struggle, when there was no question at issue between the two states.*

* The treaty of Ramses II. with the King of the Khāti, the

only one which has come down to us, was a renewal of other

treaties effected one after the other between the fathers

and grandfathers of the two contracting sovereigns. Some of

the Tel el-Amarna letters probably refer to treaties of this

kind; e.g. that of Burnaburiash of Babylon, who says that

since the time of Karaīndash there had been an exchange of

ambassadors and friendship between the sovereigns of Chaldoa

and of Egypt, and also that of Dushratta of Mitanni, who

reminds Queen Tīi of the secret negotiations which had taken

place between him and Amenōthes III.

When once the Syrian conquest had been effected, Egypt gave permanency to its results by means of a series of international decrees, which officially established the constitution of her empire, and brought about her concerted action with the Asiatic powers.

She already occupied an important position among them, when Thūtmosis III. died, on the last day of Phamenoth, in the IVth year of his reign.* He was buried, probably, at Deīr el-Baharī, in the family tomb wherein the most illustrious members of his house had been laid to rest since the time of Thūtmosis I. His mummy was not securely hidden away, for towards the close of the XXth dynasty it was torn out of the coffin by robbers, who stripped it and rifled it of the jewels with which it was covered, injuring it in their haste to carry away the spoil. It was subsequently re-interred, and has remained undisturbed until the present day; but before re-burial some renovation of the wrappings was necessary, and as portions of the body had become loose, the restorers, in order to give the mummy the necessary firmness, compressed it between four oar-shaped slips of wood, painted white, and placed, three inside the wrappings and one outside, under the bands which confined the winding-sheet.

* Dr. Mahler has, with great precision, fixed the date of

the accession of Thūtmosis III, as the 20th of March, 1503,

and that of his death as the 14th of February, 1449 b.c. I

do not think that the data furnished to Dr. Mahler by

Brugsch will admit of such exact conclusions being drawn

from them, and I should fix the fifty-four years of the

reign of Thūtmosis III. in a less decided manner, between

1550 and 1490 b.c., allowing, as I have said before, for an

error of half a century more or less in the dates which go

back to the time of the second Theban empire.

Drawn by Boudier, from a photograph lent by M. Grébaut, taken by Emil Brugsch-Bey.

Happily the face, which had been plastered over with pitch at the time of embalming, did not suffer at all from this rough treatment, and appeared intact when the protecting mask was removed. Its appearance does not answer to our ideal of the conqueror. His statues, though not representing him as a type of manly beauty, yet give him refined, intelligent features, but a comparison with the mummy shows that the artists have idealised their model. The forehead is abnormally low, the eyes deeply sunk, the jaw heavy, the lips thick, and the cheek-bones extremely prominent; the whole recalling the physiognomy of Thūtmosis II., though with a greater show of energy. Thūtmosis III. is a fellah of the old stock, squat, thickset, vulgar in character and expression, but not lacking in firmness and vigour.* Amenōthes II., who succeeded him, must have closely resembled him, if we may trust his official portraits. He was the son of a princess of the blood, Hātshopsītū II., daughter of the great Hātshopsītū,** and consequently he came into his inheritance with stronger claims to it than any other Pharaoh since the time of Amenōthes I. Possibly his father may have associated him with himself on the throne as soon as the young prince attained his majority;*** at any rate, his accession aroused no appreciable opposition in the country, and if any difficulties were made, they must have come from outside.

* The restored remains allow us to estimate the height at about 5 ft. 3 in. ** His parentage is proved by the pictures preserved in the tomb of his foster-father, where he is represented in company with the royal mother, Marītrī Hātshopsītū. *** It is thus that Wiedemann explains his presence by the side of Thūtmosis III. on certain bas-reliefs in the temple of Amada.

It is always a dangerous moment in the existence of a newly formed empire when its founder having passed away, and the conquered people not having yet become accustomed to a subject condition, they are called upon to submit to a successor of whom they know little or nothing. It is always problematical whether the new sovereign will display as great activity and be as successful as the old one; whether he will be capable of turning to good account the armies which his predecessor commanded with such skill, and led so bravely against the enemy; whether, again, he will have sufficient tact to estimate correctly the burden of taxation which each province is capable of bearing, and to lighten it when there is a risk of its becoming too heavy. If he does not show from the first that it is his purpose to maintain his patrimony intact at all costs, or if his officers, no longer controlled by a strong hand, betray any indecision in command, his subjects will become unruly, and the change of monarch will soon furnish a pretext for widespread rebellion. The beginning of the reign of Amenōthes II. was marked by a revolt of the Libyans inhabiting the Theban Oasis, but this rising was soon put down by that Amenemhabī who had so distinguished himself under Thūtmosis.* Soon after, fresh troubles broke out in different parts of Syria, in Galilee, in the country of the Amurru, and among the peoples of Naharaim. The king’s prompt action, however, prevented their resulting in a general war.** He marched in person against the malcontents, reduced the town of Shamshiaduma, fell upon the Lamnaniu, and attacked their chief, slaying him with his own hand, and carrying off numbers of captives.

* Brugsch and Wiedemann place this expedition at the time

when Amenōthes IL was either hereditary prince or associated

with his father the inscription of Amenemhabī places it

explicitly after the death of Thūtmosis III., and this

evidence outweighs every other consideration until further

discoveries are made.

** The campaigns of Amenōthes II. were related on a granite

stele, which was placed against the second of the southern

pylons at Karnak. The date of this monument is almost

certainly the year II.; there is strong evidence in favour

of this, if it is compared with the inscription of Amada,

where Amenōthes II. relates that in the year III. he

sacrificed the prisoners whom he had taken in the country of

Tikhisa.

Drawn by Faucher-Gudin.

He crossed the Orontes on the 26th of Pachons, in the year II., and seeing some mounted troops in the distance, rushed upon them and overthrew them; they proved to be the advanced guard of the enemy’s force, which he encountered shortly afterwards and routed, collecting in the pursuit considerable booty. He finally reached Naharaim, where he experienced in the main but a feeble resistance. Nīi surrendered without resistance on the 10th of Epiphi, and its inhabitants, both men and women, with censers in their hands, assembled on the walls and prostrated themselves before the conqueror. At Akaīti, where the partisans of the Egyptian government had suffered persecution from a considerable section of the natives, order was at once reestablished as soon as the king’s approach was made known. No doubt the rapidity of his marches and the vigour of his attacks, while putting an end to the hostile attitude of the smaller vassal states, were effectual in inducing the sovereigns of Alasia, of Mitanni,* and of the Hittites to renew with Amenōthes the friendly relations which they had established with his father.**

* Amenōthes II. mentions tribute from Mitanni on one of the

columns which he decorated at Karnak, in the Hall of the

Caryatides, close to the pillars finished by his

predecessors.

** The cartouches on the pedestal of the throne of Amenōthes

IL, in the tomb of one of his officers at Sheīkh-Abd-el-

Qūrneh, represent—together with the inhabitants of the

Oasis, Libya, and Kush—the Kefatiū, the people of Naharaim,

and the Upper Lotanū, that is to say, the entire dominion of

Thūtmosis III., besides the people of Manūs, probably

Mallos, in the Cilician plain.

This one campaign, which lasted three or four months, secured a lasting peace in the north, but in the south a disturbance again broke out among the Barbarians of the Upper Nile. Amenōthes suppressed it, and, in order to prevent a repetition of it, was guilty of an act of cruel severity quite in accordance with the manners of the time. He had taken prisoner seven chiefs in the country of Tikhisa, and had brought them, chained, in triumph to Thebes, on the forecastle of his ship. He sacrificed six of them himself before Amon, and exposed their heads and hands on the faēade of the temple of Karnak; the seventh was subjected to a similar fate at Napata at the beginning of his third year, and thenceforth the sheīkhs of Kush thought twice before defying the authority of the Pharaoh.*

* In an inscription in the temple of Amada, it is there said

that the king offered this sacrifice on his return from his

first expedition into Asia, and for this reason I have

connected the facts thus related with those known to us

through the stele of Karnak.

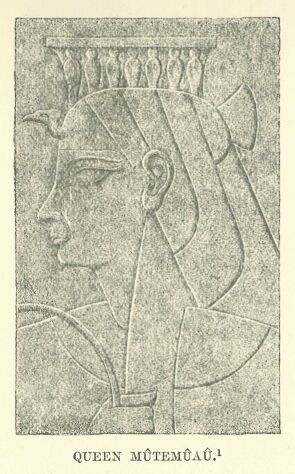

Amenōthes’reign was a short one, lasting ten years at most, and the end of it seems to have been darkened by the open or secret rivalries which the question of the succession usually stirred up among the kings’ sons. The king had daughters only by his marriage with one of his full sisters, who like himself possessed all the rights of sovereignty; those of his sons who did not die young were the children of princesses of inferior rank or of concubines, and it was a subject of anxiety among these princes which of them would be chosen to inherit the crown and be united in marriage with the king’s heiresses, Khūīt and Mūtemūaū.

Drawn by Faucher-Gudin, from the photograph taken in 1887 by

Émil Brugsch-Bey

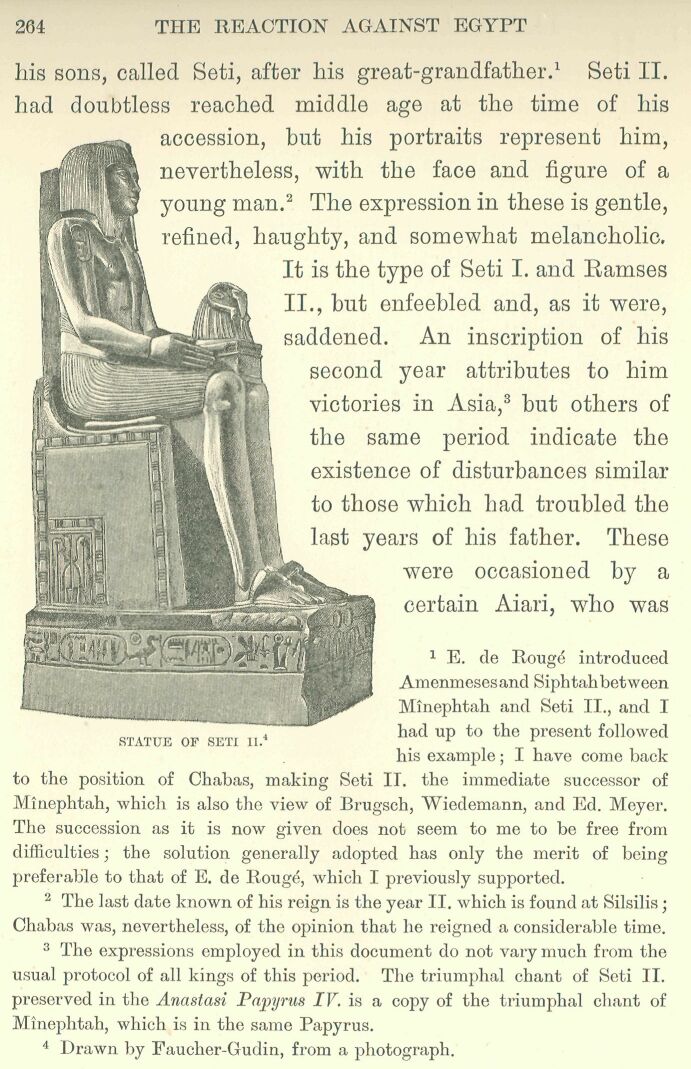

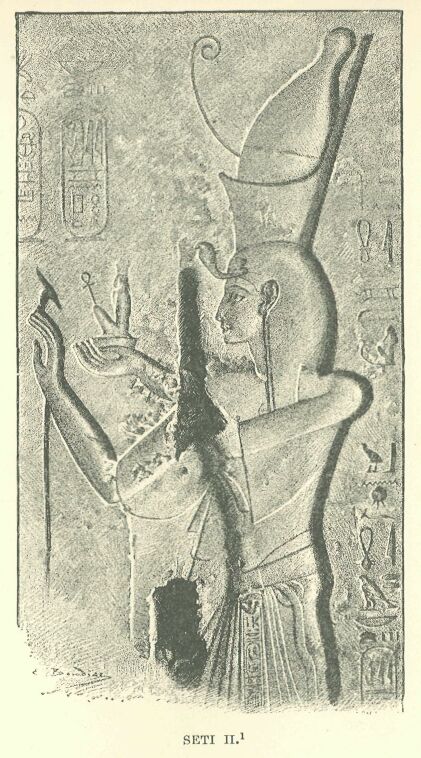

Drawn by Faucher-Gudin, from a photograph by Daniel Héron.