The Project Gutenberg EBook of Stories of Many Lands, by Grace Greenwood This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net Title: Stories of Many Lands Author: Grace Greenwood Release Date: October 1, 2008 [EBook #26736] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK STORIES OF MANY LANDS *** Produced by Al Haines

I dedicate this book to you, my dearest dears, with more love than I have ink to write out, and more good wishes and fond hopes than any printer would care to print.

You will see by these stories that the children of different countries are pretty much alike. I doubt not, if you were in France now, you would get along nicely with the little Monsieurs and Mademoiselles, after some coy hanging back and reconnoitring,—that is, if you only knew their "lingo." So with the little Signors and Signorinas of Italy, and the small Dons and Donnas of Spain. You would find the Dutch boys and girls, who look so sober and quaint, like men and women cut short, to be real children after all. If you should visit Turkey, you would find the little Turks and Turkesses full of young human nature,—love, naughtiness, grace, caprice, mischievous tricks, frolic, and all that. Should you even take a trip to China,—the country that's right under us, you know,—you would get acquainted with the Chinese young folks somehow, though you could only converse by signs. The boys would look very funny to you, with their yellow tunics, and queer hats, and long "pigtails,"—and the girls with their hair turned up into a top-knot, their slanting eyes, and their tottering walk,—for the rich young ladies there have no feet to speak of. They compress their feet instead of their waists, because, you see, they are not Christians. So you could n't dance, jump the rope, play croquet, or take a run on the great Chinese wall with them; but you could play with puzzles, have tea-parties, and pick the tea-leaves right from the bushes.

Children all the world over laugh and weep, quarrel and make up, play hard, and eat heartily, love and try their mammas, pet and tease their little brothers and sisters,—are a sweet care and a dear perplexity, and are God's little folk, all of them. I think they have the best share of His love and of this life's happiness wherever they are. But, darlings, I want you to feel that you need not envy any children on earth,—not the richest and proudest, not the daughters of a German Grand Duke, with a kingdom so large that you could scarcely walk across it in a long summer day, nor any East-Indian Princesses, twinkling with diamonds, and rattling with pearls, and riding on elephants, nor Turkish Princesses wearing baggy satin trousers and velvet jackets, and walking on costly carpets, nor Chinese Princesses that don't walk at all, nor Spanish Princesses who go to bull-fights in splendid state-coaches, and wear long trains, and are every now and then presented to the Queen, their mother, and allowed to kiss her hand, nor even English Princesses who live in castles and palaces and see the Queen every day. I really want you to feel that yours is a proud and happy lot, in being true-born American girls, in having honest and loyal parents, in having lived during our grand sad war for Union, in having heard the ringing of the bells of peace, in having loved and mourned the good, great President, Abraham Lincoln.

If in this volume I have chosen to tell you some stories about titled people of foreign lands, it is that you may not be so set up by your privileges as little citizenesses of the great Republic, as not to feel kindly and humanly toward even little Lords and Ladies, who, being the slaves of pomp, etiquette, and fine clothes, know nothing about freedom and equality, and good, jolly times; who have no Star-Spangled Banner, and no Fourth of July, and who have scarcely ever heard of George Washington and General Grant.

Wishing you merry holidays, I kiss my hand to you.

GRACE GREENWOOD.

HOW WE ACT; NOT HOW WE LOOK

A CHARADE

LITTLE FOOTMARKS IN THE SHOW

BABIE ANNIE TO COUSIN J——

THE DAY AT THE CASTLE

A CHARADE

FAITHFUL LITTLE RUTH

CHRISTMAS,—A MOTHER'S EXCUSE

CASTLE AND COTTAGE

A CHARADE

JAMIE'S FAITH

A CHARADE

THE TRUE LORD

A REBUS

THE CONSCRIPT

A CHARADE

THE DRUMMER-BOY

A REBUS

LITTLE CARL'S CHRISTMAS-EVE

A CHARADE

GIUSEPPE AND LUCIA

A CHARADE

MY PET FROM THE CLOUDS

A CHARADE

THE TWO GEORGES

A CHARADE

THE LITTLE WIDOW'S MITE

A COUPLE OF CHARADES

BESSIE RAEBURN'S CHRISTMAS ADVENTURE

A CHARADE

"O Tommy, what a funny little woman! come and see!" cried Harry Wilde, as he stood at the window of his father's house, in a pleasant English town. Tommy ran to the window and looked out, and laughed louder than his brother. It was indeed a funny sight to see. In the midst of a pelting rain, through mud and running water, there waddled along the queerest, quaintest little roly-poly figure you can imagine. It was a dwarf woman, who, though no taller than a child of seven or eight years, wore an enormous bonnet, and carried an overgrown umbrella. Her clothes were tucked up about her in a queer way, and altogether she was a very laugh-at-able little creature. As she passed, she looked up, and such an odd face as she had! The nose was large and long, as though it had kept on growing after the other features gave out. Indeed, it was so big that the eyes had got into a way of looking at it constantly, which did not improve their beauty. The hair was bushy, and of a lively red, but the mouth was quite sweet and good-humored, and the little crossed eyes had a merry, kindly twinkle in them.

"Well," said Harry, "if I were such an absurd looking body as that, I wouldn't show myself. I 'd hide by day, and only come out by night, like an owl, would n't you, Tommy?"

"Yes," said the little boy, and then asked, "Did God make her, Harry?"

"Why yes, He made what there is of her, and then I suppose He concluded it wasn't worth while to go on with her!"

"Harry! Harry!" cried the mother of the little boys, "you must not talk so; it is wicked. That poor little dwarf may be of much use in the world, and do a great deal of good, if she has a kind heart; and she looks as though she had."

"I should like to know of what use such a poor wee thing can be," said Harry, shrugging his shoulders.

"God knows," said Mrs. Wilde, "and He did not make her in vain."

The next day was Christmas. The rain was over, and it was clear and cold.

"Hurrah!" cried Harry from the window, "here's our wee bit woman again. Her hair is as fiery as ever. I wonder the rain didn't put it out. She might warm her hands in it, if it weren't for carrying that big basket."

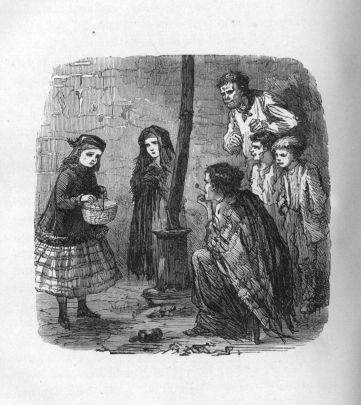

Mrs. Wilde looked out. The dwarf was trudging slowly along, bearing a heavy basket. The good lady was seized with a strong desire to know more about the strange little creature; so she hurried to her room, put on a bonnet and cloak, went out and followed after her, quietly. She had to go a long way before her curiosity was satisfied; but at last she saw the dwarf enter a miserable house, in the suburbs of the town. Mrs. Wilde stole up to a window, and ventured to look in. She saw the dwarf surrounded by a crowd of shouting children, to whom she was giving Christmas-cake, toys, and clothes from her basket. She saw her give food and medicine to a poor woman, who lay on a bed in a corner. She heard her say, "Have the coals come?" and the woman answer, "Yes, and the blankets; God bless you!" She saw her take up the baby, feed it, and play with it,—so big a baby, that Mrs. Wilde thought it ought to take turns in tending, with the good little dwarf. Then the lady turned away in tears, and went home. When she had told Harry what she had seen, he blushed deeply, and Tommy said: "God knew better than brother what the funny little woman was good for, did n't He?"

O be my first, my darling child,

Whatever may betide;

Meet falsehood with its best rebuke,

An open, earnest, honest look,

Clear-browed, and fearless-eyed.

Be like my second, thoughtful, wise,

And in life's summer prime,

Gather and hoard a goodly store

Of truth and love, and priceless lore,

To cheer its winter time.

But never let thy frank young heart

Consent to play my whole;

Let will and honor in it meet,

Let Duty ever guide thy feet,

And keep thy steadfast soul.

Tru-ant

It was at a rectory, in the South of England, that two young children, a boy and a girl, were looking out of a nursery window, on Christmas morning,—the morning of the first snow. The girl, who was about seven years old, was a beautiful, simple-hearted, amiable child, the daughter of English parents, residing in India. Some months previous to this winter morning she had been sent to England, on account of her delicate health, and confided to the care of her mother's sister, Mrs. Graham, the Rector's wife. Her name was Margaret Pelham; but she was called Meggie and Meg, Peggy and Peg, and various other odd nicknames by her English cousins.

Little Margaret's chief playmate at the Rectory was her cousin Archie, a boy only two years older than herself, but feeling ever so much bigger and wiser; for he was an only son, a clever and rather conceited young gentleman. He was good-natured, and loved his cousin; but he loved better to tease and hoax her. Having lived all her little life in India, Meggie was exceedingly ignorant of customs and things in her new home, and was continually making laughable mistakes, and asking the most absurd questions. This "greenness," as he called it, gave Archie immense delight, and he was never tired of mystifying and hoaxing the sweet-tempered little girl, who never resented his quizzings and practical jokes. Of course it never occurred to the silly boy that he was just as ignorant about India as Meggie was about England.

This morning, the children being left for a time alone in the nursery, he was having a rare time at his favorite amusement. Meggie had never before seen snow, and was full of innocent wonder and admiration. "O Cousin Archie!" she said, "the pretty white clouds we saw yesterday all fell down in the night! Did you hear the noise?"

"Clouds!" cried Archie, with a snort of contemptuous laughter; "why, you poor little Hindoo, that's snow, and it came down so slow and soft that nobody heard it."

"O, is that snow?" said Meggie, laughing good-humoredly at her own ignorance. "How beautiful it is! so soft and white. It looks just like my little dovey's feathers. I think, Archie, the angels' beds must be made out of snow, aren't they?"

"O yes, of course, it would be so warm and comfortable, you know."

"Yes, it looks nice and warm. I think God must send it down to keep things from dying of cold. He puts the grass and flowers to bed so, don't He?" said simple and wise little Meggie.

Archie could not stand this. He shouted and clapped his hands, and even rolled on the carpet in an ecstasy of boyish fun, crying out, "O, how jolly green! how jolly green!"

"What?" said Meggie, "I don't see anything green. All is white, as far as I can see. The trees and bushes look as though they had night-gowns and night-caps on. How pretty the snow is, how clean and soft! I should like to run about in it, wouldn't you, Archie?"

"O yes, it's prime fun," replied the mischievous boy, "but it's no rarity to me. I 'm used to it, you know. But you would delight in it, especially with bare feet. That way it is jolly, better than wading in a brook. Suppose you try it, Peg?"

It required little urging to persuade the simple child to take off her shoes and stockings and run down with her cousin to the great hall door. She threw on her little cloak, for she said to herself, "The wind may blow cold, for all the warm snow on the ground."

The children met no one on their way. Archie, with some difficulty, opened the door, then said, "Now, Peg, run quick, away out into the pretty snow, and see how nice it feels, just like down."

Meggie did as she was bid, and Archie slammed the door after her, and bolted it, laughing uproariously. You may be sure the poor little girl soon found how cruelly she had been hoaxed, and ran back again. She knocked at the door, crying, "O Cousin Archie, do let me in! The snow isn't nice at all; it's so cold it freezes my feet. Do, do let me in."

But Archie only laughed and danced like a young savage for a minute longer, then seemed to be trying to open the door, and called out in some trouble that he could not move the bolt. Little Meggie sat down on the door-step and waited patiently till she was almost frozen. At last, after getting nearly exhausted in tugging at the heavy bolt, Archie succeeded in shoving it back. He found his little cousin so benumbed that he was obliged to carry her in his arms all the way to the nursery. Then he sat her down by the fire, chafed her hands and feet, and put on her stockings and shoes, saying many times, "I am sorry, Meggie, dear; I am so sorry!"

"O, never mind, it was only a joke," said Meggie, and tried to smile, though she suffered a great deal more than Archie knew of.

But Meggie's troubles were only begun. When they went down to breakfast, Mrs. Graham, who had seen from the parlor window the tracks of little bare feet in the snow, questioned the children about them. Meggie owned up at once that she had run out barefoot in the snow, because it looked so soft and nice, but said not a word about Archie's having prompted her to the foolish act; and I really blush to say that Archie himself was not frank and brave enough to acknowledge his fault. The fact is, he was afraid of his father, who was a stern and godly man, and had small mercy for the sins of little folks. Both the Rector and his wife reproved Meggie for her thoughtlessness, and the gentle little girl shed some silent tears; but, after all, I think Archie, who sat trying to gulp down his breakfast with a bold face, suffered the most. All day long he was unusually kind to his cousin, and she soon got over her sadness, and was as merry and loving as ever.

The next morning, when the nursery-maid came to awake Archie, she told him that his cousin had been taken very ill in the night,—so ill that they had had to send for the doctor, who feared that she might never get well. She had taken a violent cold, some way, he said.

Archie hurried on his clothes, and ran down to the nursery. He found his mother sitting by Meggie's little bed, looking very sad and anxious. He stole up to his cousin, and taking her little hand, hot with fever, bent down and kissed it, with a burst of bitter tears, sobbing out, "O Meggie, forgive me, do, do forgive me!"

"Forgive you for what, Archie?" asked Mrs. Graham.

"For being cruel and cowardly, mamma. It was I who sent Meggie out into the snow, bare-foot, and then was afraid to take my share of the blame. I was so miserable all day. I came near owning it when you kissed me good night, but papa looked so solemn, I could n't. I did n't say my prayers; I felt too mean to pray."

"God forgive you, my son!" said Mrs. Graham, somewhat sternly; but little Meggie murmured, in a sweet, faint voice, "O Cousin Archie, why did you tell? Maybe I would have died, and nobody but us would ever have known anything about it."

Meggie did not die, however. She got well after a long illness,—quite well. But this was the last of Archie's hoaxing.

You should have seen me, when papa

Brought me your gift, an hour ago;

I almost hopped out of my shoes,

And raised a mighty bantam crow!

I shook my hair about my eyes,

I flung my chubby arms about,

I hugged it, and an eager score

Of "pretty pretties" sputtered out.

I grasp it, gloat upon it now,—

My fingers glide from link to link;

I like its shine, I like its feel,

I like its golden chink a-chink.

I thank you—_don't_ I thank you, though!

My darling, dashing, handsome cousin!

I 'll pat your whiskers, when we meet,

And give you kisses by the dozen.

I 'll promise not to pull your hair,

When on your shoulder next I mount,

Nor bore my fingers in your ears,

Too often bored on my account.

Those fingers light shall never leave

On velvet waistcoat one faint crease,

Nor give your profile, clear and fine,

Another needless touch of Greece.

I will not bend the killing bow

Of that nice neck-tie, "rich, but neat,"

Nor put a ruffle in your shirt,

Nor break the white plaits with my feet.

The sacred collar shall not bear

The impress of a touch of mine;

Your sparkling diamond studs, like dews,

Shall on the lawn inviolate shine.

I will not fumble for your seals,

Nor listen where your tick-tick lies,—

Nor dare to call in anger down

The heavy lashes of your eyes.

In short, I 'll be a tender sprig,

A greenwood blossom small and sweet,

To hang upon your button-hole,

Or breathe love's fragrance at your feet.

The Reverend Charles Rivers was the Rector of a small country parish in the North of England. He was a good man, a true minister of Christ to his people. He had a lovely wife, and four beautiful children, and there was no happier or sweeter home in all the country round than the modest little Rectory, embowered in ivy and climbing roses.

Four or five miles from the parish church, on a noble eminence, rise the lofty towers of Glenmore Castle, which for centuries has been the great family seat of the Lords of Glenmore. It is surrounded by beautiful gardens, laid out in the French style, with hedges of box, full ten feet high. Beyond these a noble wooded park stretches away on all sides, for miles, taking in hill and valley, and a fairy little lake. To the southward it is crossed by a lazy, loitering stream, shadowed by willows, fringed with flags, and in the early summer flecked by snowy water-lilies.

The Lord Glenmore of the time of my story was a handsome young nobleman, married to a pretty London lady, very gay and fond of splendor, but kind-hearted and gentle to every one.

Whenever Lord Glenmore came up from London to his northern estate,—usually in the shooting season of the early autumn,—the happy event was made known to his tenants and friends, by the running up of a flag on the loftiest turret of the Castle.

Mr. Rivers had been his tutor, and his Lordship always hastened to renew his intimacy with his old friend and instructor, for whom he had a warm regard, running into the Rectory in his old, boyish, unceremonious way, and frequently inviting the Rector and his wife to dine at the Castle.

During one of these pleasant dinner-parties, Lord Glenmore, turning to Mrs. Rivers, said: "I know from happy experience that you and your good husband are always ready to lend a helping hand when one is in need. Now Laura and I want a little help. We have had a rather embarrassing arrival at the Castle,—the motherless little son and daughter of my brother, Colonel Montford. They were sent over from India, at our suggestion, but we hardly know what to do with them. They are shy and homesick, and thus far have had little to say to any one but their dusky old Ayah, their Indian nurse. Now, children can get on best with children, and so, my dear madam, I beg that you will lend us yours,—those charming little daughters, staid Margaret and roguish Maud, and that fine lad Robert. As for wee Master Alfred, my baby godson, I make no demand on him for the present. We think that if they could spend a day at the Castle now and then, they would help to break the ice between us and our unsocial little relations!"

Mr. and Mrs. Rivers willingly consented to their friends' request, and the next day was fixed upon for the first visit, both Lord and Lady Glenmore promising to do all in their power to entertain their young guests.

Early on a lovely autumn morning the children at the Rectory were made ready for the important visit. As soon as Lord Glenmore's carriage appeared in sight, they ran into the nursery, their faces bright with joyous anticipations, to bid their mamma good by. She was sitting with the baby on her lap, and they all bent down to kiss "the dear little fellow," ere they went.

"Why, mamma," said Margaret, "how hot Ally's lips are! is n't he well?"

"I am afraid not quite well," Mrs. Rivers replied; "he seems feverish. Now, my dears, I hope you will be very good and gentle all day. You, Margaret, must take good care of your sister, and Maud," she added, as she bent forward to tie in a smoother knot the strings of the little girl's hat, "you must not run quite wild with merriment. Robert, don't put yourself on your dignity with young Montford, on account of his shyness. Remember, almost everything is strange to him here, and he is sad. I am sure he does not mean to be haughty."

"O yes," replied Robert, turning from the canine playfellow he was affectionately patting, "I mean to treat him just the same as though he were a true-born Briton. He isn't to blame for being only an unfortunate Cawnpore boy, born among heathens and boa-constrictors and Juggernauts, and not knowing how to skate, or make snowballs. Good by, mamma, don't trouble yourself about me; I 'll carry myself 'this side up with care.' By by, baby. No, no, old Rover, you can't come; you would n't know how to behave with my lord's Italian greyhound, and my lady's dainty King Charles Spaniel."

Mr. Rivers, after seeing the children off, entered the nursery, to find his wife still troubled by the heat and crimson redness of the baby's cheeks and lips, though the old Scotch nurse, who was holding him, said cheerily: "Eh, dinna fash yoursel'. It's only a little teething fever, the bairnie will soon be weel. Gang about your ain affairs, and trust auld Elspeth."

But the mother dared not leave the little one till he was asleep. He slept very soundly until noon, and when he awoke it was evident that he was seriously ill. Mrs. Rivers again took him on her lap, but to her grief perceived that he did not seem to know her. Soon, his sweet blue eyes were rolled upward, his brow contracted, his lips were set, and his tender limbs grew rigid. Medical aid was called at once, but the little sufferer passed from one spasm into another, till almost ere physician and parents were aware that he was going, poor little Alfred was gone!

After the first wild burst of sorrow was over, Mr. Rivers said to his wife, "Shall I send to the Castle for the children?"

"No, Charles," replied the good mother, "though I yearn for them inexpressibly, I will not so sadly cut short their day of pleasure. The night of sorrow will come speedily enough."

Early in the evening, Lord Glenmore's carriage came dashing through the rustic gateway of the Rectory. Mr. Rivers was at the hall door awaiting the children. Margaret noticed that her papa looked serious, and that he kissed her with more than usual tenderness; but the others were too much occupied with the pleasant stories they had to tell of the day at the Castle, to remark on any change in him. They ran into the silent house, laughing and chatting merrily. They found their mamma in the little family parlor, sitting in the twilight, which prevented them seeing that she was very pale, and that her eyes were swollen with weeping.

They displayed before her presents of choice fruit and flowers from Lady Glenmore, and some curious Indian toys which the little Montfords had given them.

"O mamma," said Robert, "we have had such a glo-ri-ous day! Arthur Montford and I got on famously together. I taught him all the English plays I could think of, and he let me gallop about on his Shetland pony,—a splendid wild one, mamma,—till I lost my hat, and was all out of breath, and got thrown three times. Didn't hurt me, though. Altogether, we had such prime sport, that I wished for that old Bible hero, Aaron, no, Joshua, to command the sun to stand still, so that our day would never end."

"And, mamma," broke in little Maud, "dear Lady Glenmore, and her sister, Lady Fanny, played and sung for us, and showed us pictures and jewels, and Alice Montford has got such a world of dolls, and her nurse is such a dark, dark woman, and talks such a queer language, Latin, I suppose. I did n't pretend to understand it, but I told Alice my papa could."

"Well, Margaret, dear," said Mr. Rivers, "what is your experience?"

"O papa, it was indeed a charming day; but the best part was while the ladies were dressing for dinner, when Lord Glenmore took us girls down to the little lake on the other side of the Castle; and he was so kind in leading us along by the water, helping us over the bad places, and plucking flowers for us. He even sat down with us in the grass, and told us stories, while we made daisy-chains. Then he took us in his boat on the lake, and rowed about, and, O mamma, what do you think! as we were passing a thick clump of flags, he parted them with his oar, and showed us a swan's nest! I thought of Mrs. Browning's poem of little Ellie, and her 'Swan's Nest among the Reeds.' O, I had almost forgot! Lord Glenmore intrusted to me the sweetest gift for baby Alfred: see! this lovely coral necklace. He ordered it expressly from London, for his little god-son, he said. That makes me think! how is baby to-night, mamma?"

The time was come. Mrs. Rivers glanced at her husband; but he turned away his head. He could not tell them. Then, calmly, though her voice trembled a little, the mother began: "Listen, my darlings, I have something important to tell you about baby."

The children gathered closer about her, and were very still.

"While you were away, a great Lord sent for little brother, too."

"What for? to adopt him as his heir?" asked Robert.

"Yes, my son; and Ally has gone to a mansion far grander than the Castle, where the gardens are fairer, and the fields greener than any you have ever seen; and, Robert, the sun never sets over that beautiful land."

"Did he go in a carriage with a coronet on it, and two powdered footmen behind?" asked Maud.

"No, love; but gentle beings, more good and beautiful than those kind ladies of the Castle, bore him away, and will tend him, lovingly."

"I think he will miss nurse Elspeth, and cry for her, and they will have to send him home again," said poor, bewildered little Maud.

"Why, mamma," cried Margaret, "we can't spare baby to the greatest lord on earth!"

"But, my daughter, to the 'Lord of lords' we must spare him. He will 'lead' him as you were led to-day, 'beside the still waters, and cause him to lie down in pleasant pastures,' and our darling will never know pain, nor hunger, nor sorrow."

"O mamma, mamma, I know what you mean now!—baby is dead!"

Then went up the children's united voices, like one sad wail, "Baby is dead!"

"Yes, my children," said their father, in a voice broken by grief, "our precious little Alfred is gone. But, try to say, and try to help us say, 'The Lord gave, and the Lord hath taken away; blessed be the name of the Lord.'"

The poor children could not say it then, for their bitter crying; but, before they went to bed, they sobbed forth the sacred words, as they knelt by the crib where little Ally lay, still, and very pale, dressed in a snowy muslin frock, with his waxen hands clasped on his breast, and holding a tiny white rose-bud, an emblem of his sinless little life.

In the wet rice-swamps and canebrakes tall

My _first_ the driver wields;

It sounds among the dusky gang

In the snowy cotton-fields;

But fast comes on the day that ends

Its reign of blood and fear,—

Comes with the sound of breaking chains,

And the freedman's joyous cheer.

Be kind to such as are my second,

In spirit and in truth;

Have pity on their helpless age

And on their joyless youth.

Remember them whene'er you feast,

And on your downy bed,

For the sake of Him who "had not where

On earth to lay his head."

Good may my third be in your hearts

Towards all of human kind,

Strong to reclaim the wandering,

And the lost lamb to find;

To help the suffering, and to bear

Thine own adversity;

To speak brave words for truth and right,

And strike for liberty.

My whole is a mournful little bird,

That in the twilight dim

Complains how hardly he's been used,

Till all must pity him.

But not one word of what he did

Reveals the doleful wight,—

His mother's story could we hear,

We might say, "Served him right!"

Whip-poor-will.

Little Ruth Mason sat one sweet June morning in the church-porch, by the side of her old grandfather, who stood reverently leaning on his staff, with his hat in his hand. They were both watching from that ivied porch a touching and impressive scene,—the burial service in the old churchyard.

Mr. Mason had been for many years the sexton of the parish, and though now too old to discharge the duties of the office, he felt such a loving interest in the parish church, one of the finest in England, that he could not keep away from it. Every day he visited the scene of his old labors, and kindly gave the new sexton the benefit of his long experience. Sometimes he might be seen kneeling in silent prayer in the noble chancel, the sunlight that streamed through the stained windows falling in tender glory on his venerable head. Sometimes he would linger by the hour in the beautiful churchyard, beside the graves of his wife, his son, and his son's wife, all the dear ones God had given him, except one little granddaughter. This last remaining object of his affection and care was a lovely and loving child, of a peculiarly thoughtful mind, and of a sweet, constant, religious nature. She had been carefully trained by a good grandmother, and was prudent and industrious beyond her years. When not in the little village school, she was almost always with her grandfather, his little companion, pupil, and house-keeper.

This interesting orphan child was most kindly regarded by many of the good village people. She seemed so lonely and helpless in the old sexton's desolate cottage,—but a poor place at best. Yet she was hardly an object of pity. Her father and mother had died in her infancy, and after her first childish grieving for her grandmother was past, she seemed quite happy and content with the care and companionship of her grandfather. It was with difficulty that she had been persuaded now and then to leave him to spend an afternoon at the pleasant Rectory, when the Rector's kind wife sent for her, to amuse a sickly little daughter, who was very fond of her, and in whom Ruth's health, strength, and cheery spirit excited a pathetic wonder and delight.

It was the burial of this child, poor little Lilly Kingsley, which Ruth and her grandfather were beholding from the shadowy church-porch on that lovely June morning. Mr. Mason stood with his head bowed, intently listening to the solemn burial service, and reverently wondering at the providence of God, which had passed by him, so old, feeble, and almost useless, and taken from the good Rector and his wife their one only darling.

Ruth had wept bitterly over the body of her little friend, as she had seen it that morning, in the coffin, almost covered with white flowers, and nearly as white as they; but now she watched the mournful ceremonies with a rapt and eager interest, too profound for tears. Her young spirit was struggling with the mystery of death, and thoughts of immortality. She knew that the wasted little body let down into the dark grave was not all of her poor playmate, and she strove to picture a little angel like Lilly, only blooming, and happy, and free from pain, borne upwards through the still summer night, by tender angels, who looked back very pityingly on the grieving parents, bending over the death-bed of their risen darling.

So lost was the child in these thoughts, that she did not speak nor move till the service was over, and the weeping group that had stood by the grave had passed out of the churchyard.

A few days after this funeral, little Ruth coming home from school, found the Rector in earnest conversation with her grandfather. She courtesied timidly to the clergyman, but he drew her to his knee, looked kindly into her beautiful dark eyes, and said, "How would Ruth like to live always at the Rectory, and fill the place of our little lost daughter?"

Ruth's sweet face flushed with delight, and she answered, "O, sir, I should dearly love such a beautiful home, and you would too, would n't you, grandpapa?"

The Rector looked at Mr. Mason, and the old man, drawing the child to him, said tenderly, "My dear little girl, your old grandfather cannot leave this cottage, in which he was born, and in which he has always lived, until he goes to his long home."

"Then I'll not go," cried Ruth, impulsively flinging her arms about his neck. "I 'll never, never leave you. Who would take care of you if I were gone?"

The Rector smiled; but the old man answered gravely, "I know I shall miss you, dear, very much; but the Lord will care for me, and He it is who has provided this home for my darling. I bless His name for His loving-kindness. You have always been a good, obedient child to me, and I know you will obey me, even when I send you away from me,—for your best good, mind, my darling."

Ruth still wept, and begged to be allowed to stay with him; but her grandfather was firm, and she yielded at last. He led her to the Rectory, kissed and blessed her, and placed her in the arms of Mrs. Kingsley, then hobbled out of the gate, and back to his desolate cottage, as fast as his poor old limbs could carry him.

Ruth was very sad all the afternoon, though everybody was kind to her, and her new mother strove tenderly to comfort her. As evening came on, her heart would go back to the humble old home, and the white-haired, feeble old man, who she knew must be thinking of her, and missing her so sadly. At length, Mrs. Kingsley conducted her to a pleasant little chamber, which was henceforth to be her own. The good lady helped her to undress, put on her a dainty little ruffled nightgown, and knelt with her by her bedside while she said her prayers. After praying in a broken voice for her poor old grandpapa in his loneliness, the child remembered to ask God's blessing on her new parents. After seeing her in her snowy little bed, Mrs. Kingsley removed Ruth's clothes to a closet near by, and brought out a complete suit of garments suited to her new condition. They were very neat and pretty, and Ruth, who loved all beautiful things, smiled on them through her tears, and reaching out her hand, felt of them with simple, childish delight. Then a strange, thoughtful look passing over her face, she said, "Mamma!" Mrs. Kingsley started. It was the first time she had heard that name since her Lilly died, though she had asked Ruth to call her by it when she was first brought to the Rectory. But she answered, with a smile, "What, my daughter?"

"Why, mamma, laying off my faded clothes and putting on those lovely new ones will be like Lilly, leaving the poor, pale body she used to have, for her glorious angel body, won't it?"

"Yes, darling," replied the mother, to whose heart the simple illustration brought a sweet, wonderful realization of the blessed change; and as she stooped and kissed Ruth good night, a tear fell on the little girl's cheek.

The adopted child slept tranquilly till nearly morning, when she awoke suddenly, probably from a dream of the home she had left, but thinking that she heard a voice above her, saying solemnly, "Ruth, little Ruth, why hast thou forsaken My servant, thy grandfather?"

She was not frightened, yet she could not sleep again, but sat up in her little bed, impatiently waiting for the day. In the first gray light of dawn she rose, went to the closet, took out her old clothes, and dressed herself in them, and casting scarcely a look on the new clothes or round the sweet little chamber, she stole softly down stairs. She found a housemaid in the hall, who, not knowing the plans of her master and mistress in regard to the little girl, let her out, and she ran swiftly home. She found the cottage door unfastened, for the poor have little fear of burglars. Entering quietly, and finding her grandpapa still asleep, she lay down by his side, and when he awoke, her dear arms were about his neck, and her loving eyes smiling into his. At first, he forgot she had been away; but after a moment, he remembered, and exclaimed, "You here, little Ruth? Why did you come back, against my wish?"

"Because the Lord sent me back," she answered, gravely.

"Why, child, what do you mean?" he asked.

"Grandpapa, dear, this is how it was: There was a voice, such a sweet and solemn voice, that came and sounded right by me, in the darkness, and it said, 'Ruth, little Ruth, why forsakest thou My servant, thy grandfather?' and I was sure it was the Lord's voice, the very same that spoke to little Samuel, and I could not stay after I heard it. I will never leave you to live and die alone, even if the queen wants to adopt me. Why, grandpapa, if God had meant you to be without me, He would have taken me, instead of little Lilly Kingsley. So don't send me away from you, dear grandpapa; it would be wicked."

The good old man, with tears in his dim eyes, replied, "No, my darling little girl shall not be sent away again; it does seem to be the Lord's will that you should stay with me as long as I stay."

And so she stayed,—the faithful little Ruth. Her good friends at the Rectory were sorry to lose her, but not displeased with her, and were more kind than ever to her and her grandfather. The next Sunday, as she knelt with him among the poor, she was glad in her heart that she was not shut away from him in the Rector's crimson-cushioned pew.

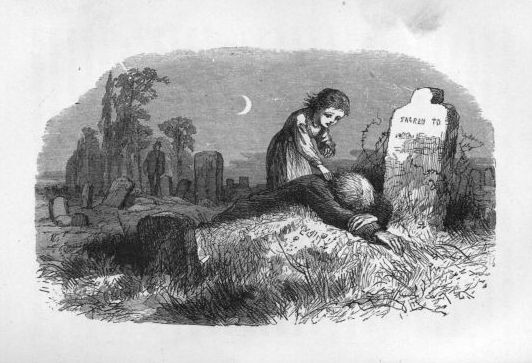

It was on a Sunday a few weeks later, that her grandfather, after their frugal dinner, called her to go with him to the churchyard, saying, "A year ago to-day, Ruth, your dear grandmother died; let us go and spend an hour or two by her grave."

They took the family Bible, and read and talked a long time, sitting on the daisied grass, under the pleasant shade of a willow. At last, the good old man seemed to grow weary, and bowing his white head on the grave, with one arm flung over it, he fell asleep while Ruth was singing a hymn which her grandmother had taught her. Then Ruth stole away, and wandered about the churchyard, reading the inscriptions on the tombstones, till the people began to enter the church for evening service. Then she returned to her grandfather, and touched him on the shoulder, to wake him. But he did not move. She called his name, but he did not seem to hear her. Just then the Rector came up, and seeing Ruth's trouble, bent down to look into the face of the old man. He raised the withered hand that lay on the mound, and held it a moment, looking anxious and sad. When he laid it down, he put his arms about Ruth, and said, tenderly, "My dear child, your grandfather is awake—in Heaven. He will never wake on earth. The Lord has taken him."

With a piteous cry Ruth flung herself by the side of her dead grandfather, and called him by many fond names, weeping bitterly; and strong men wept in pity for her bereavement, and stood with uncovered heads as her grandfather was lifted and borne to his old home.

From that old home he was carried forth to be laid by the side of his dear old wife; but from that lonely cottage little Ruth was led weeping, yet grateful, to her new home by the Rector and his wife, henceforth to be to them a dear and cherished child. Few were the tears she shed in that beautiful home, and tenderly were they wiped away; and if the Lord ever spoke to her again in her peaceful little chamber, through the darkness, it was in "the still, small voice" of blessing, love, and comfort.

It comes again, the blessed day,

Made glorious by the Saviour's birth,

When faintly in a manger dawned

The light of God which fills the earth

On this sweet morn, in years gone by,

Around one happy hearth we came,

And wished each other joy and peace,

Embracing in the dear Lord's name.

Now o'er a weary, wintry waste,

My heart a loving pilgrim wends

Her pious way, this holy time,

To greet you, O belovéd friends!

Fondly I long to take my place

Beside your hearth, its joy to share,—

To sun me in the summer smiles

Of the dear faces gathered there.

But baby eyes upraised to mine,

And baby fingers on my breast,

Steep all my soul in sweet content,—

Charm even such longings into rest.

Yet, dear ones, let my name be breathed

Kindly around the Christmas tree,

And my soul's presence greet, as oft

In Christmas times ye 've greeted me.

No unadorned and humble guest

Comes that fond soul this blessed even

She bears a jewel on her breast

That radiates the light of heaven.

A rose, that breathes of Paradise,

Just budded from the life divine,

A little, tender, smiling babe,

As yet more God's and heaven's than mine.

Born in the Saviour's hallowed month,

A blessed Christ-child may she be,

A little maiden of the Lord,

Room for her by the Christmas tree!

It would seem that little Bertha Blantyre had everything that her heart could wish. She was an only daughter, and a pretty, blooming, petted darling. Her father was a rich lord, and, what was better, a good and kind-hearted man. Her mother was a noble lady, and, what was more, a gentle and loving woman, and even little Bertha had from her cradle the title of "Honorable," which is as much as our great Congressmen can boast. Yet I am sorry to say, this little lady was not always as happy and grateful as she should have been, but was sometimes sadly discontented, believing that other children were far happier than she. All such little girls as had brothers and sisters to play with them, and run about with them in the woods and over the moors, she envied bitterly, even though they were the children of poor peasants,—never thinking it possible that they might be envying her at the same time.

Lord Blantyre resided principally at Blantyre Castle, on a noble estate, among the heathery hills of Scotland. The Castle was very ancient, with towers, and turrets, and a massive gateway, but it had many modern additions which beautified it, and gave it a cheerful, almost home-like look. Through the old moat there slowly ran a bright, clear stream, in which grew hosts of water-lilies, and other aquatic plants. Beyond this were soft, green, close-shaven lawns and shrubberies, and gardens full of fountains and statues and fairy-like bowers; the stables, full of beautiful horses and ponies; the kennels, where a pack of noble stag-hounds was kept; the dairy, the poultry-yard, and the pretty little houses of the gold and silver pheasants. Around all was a great wooded park, filled with fleet spotted deer.

In this park Bertha often walked with her mother, or was whirled along in a small open phaeton, drawn by two lovely white ponies, which Lady Blantyre herself drove.

In the wildest and most remote part of the park lived the gamekeeper, who, with his wife, had been born and bred on the estate, and from childhood had been in the service of the noble family. Lady Blantyre never passed the cottage of Robert MacWillie in her drives without stopping to inquire after the health of his wife, who had once been her maid, and of their fine brood of little ones. During these visits Bertha became acquainted with the young foresters, and as she was of a simple and amiable disposition, and not a bit haughty or conceited, she liked them all heartily. But she especially took to a little girl about her own age, named Lilly, and a boy a year or two older, called Hughie.

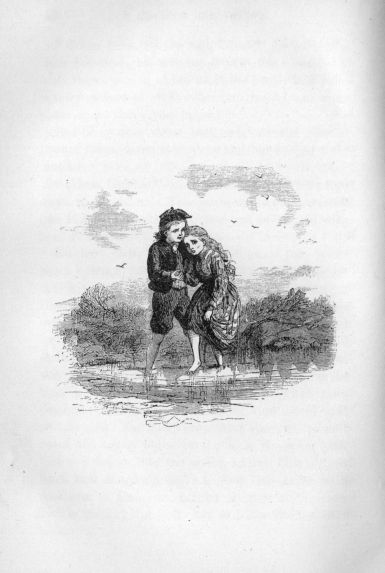

One day as Lady Blantyre and Bertha were driving along the shore of a miniature loch or pond, near Robert MacWillie's cottage, they saw Hughie and Lilly playing in a burn, or brook, which emptied into the little loch. Hughie was constructing a dam, with stones and turf and heather-branches cemented with clay, and Lilly was sailing a tiny boat, loaded with pebbles and flowers. Both were barefoot, and plashing fearlessly in the burn. Lady Blantyre checked her ponies, and after watching the children awhile, called them to the side of her phaeton. Hughie took off his Glengary cap, and held it in his hand, and Lilly was about to pull from her head a wild-looking wreath of daisies and purple heather-blooms, when Bertha exclaimed, "Don't take it off! it is so pretty; who made it?"

"Brother Hughie," answered Lilly, blushing.

"How good he must be! Do you like playing and wading in the water and picking wild-flowers?"

"Yes," said Lilly, looking down, and drawing figures in the sand with her rosy little toes. "Hughie is gude. I like playing wi' the burn, and flowers are bonny wee things"; then, looking up timidly, she offered to her friend a bunch of water-lilies, which Hughie had waded far out into the pond up to his short kilt to obtain.

"Thank you," said Bertha. "O how sweet they are, a thousand times sweeter than those that grow in the moat, are n't they, mamma?"

Lady Blantyre smiled, for there was really no difference, the lilies at the Castle having been brought from this very pond.

"How long have you been at your great work there?" she asked of Hughie.

"For maist a week, my Lady; but for the last twa days Domine MacGregor has been down wi' an ill turn, and I hae (have) lost na time at schule (school), so I hae got on weel wi' it. It will soon be done noo."

"And what do you intend to do with it when it is finished?" asked the lady.

"I canna say, but I think we 'll play flood-time wi' it."

"What is that?"

"Your ladyship sees that wee-bit island; weel, we'll put on it some doggies and a cat."

"Not my wee puss, Winkie?" cried Lilly in alarm.

"No, auld black Tammy will do, and a chicken or twa, and we 'll watch the water rise and rise, till the puir creatures huddle togither and greet and cackle and howl, then I 'll loup (leap) intil the burn, and one after anither rescue them a'."

"O, how grand that would be!" exclaimed little Bertha, her eyes flashing with excitement.

"Rather cruel sport," said Lady Blantyre, shaking her head, yet smiling in spite of herself.

"Is it?" said Hughie, his countenance falling, "then I 'll no do it. I 'll but drive a' the duckies and fulish geese down here, and see them gae quacking and skirling over the dam. I hope they'll no object to the sport."

"Probably not," said her ladyship, pleasantly.

"O mamma," said Bertha, looking up wistfully into her face, "how I should love to play so with water and pebbles, and little boats, and ducks and geese, and dams, all day long! How happy they must be!"

"Perhaps little Lilly thinks it would be a very happy thing to be in your place, my daughter," said Lady Blantyre.

"Do you think so?" asked Bertha, wonderingly.

"Ay," answered Lilly, in a low, almost awestruck tone, "I think that to be Miss Bertha, and bide in a braw (fine) Castle, wad be next to being an angel, or a bonnie fairy princess."

All laughed at this, but on the way home Bertha was very thoughtful and sad. Every time she spoke, it was to bewail her hard lot in being allowed to take the air only in walks with her governess, or drives with her mamma, in being obliged to wear fine clothes, to learn music and dancing, "and other tiresome things," and never being free to run wild on the hills and heaths, wade in the ponds, and plash in the burns, like the little MacWillies.

Her mother tried to show her that, as her station was different from theirs, her education and habits should be different, and that she had a great deal to be thankful for, and might be very happy, if she would.

"Well, I think I ought at least to have a little brother to play with me. I think God might have given me that, and kept back some of the other things."

At this little burst of petulance, Lady Blantyre sighed and was silent for some moments. Then she said: "Would my little daughter like to try living at the cottage of the MacWillies for a day or two, just like one of their own?"

"O yes, mamma, and play with Lilly and Hughie?"

"With Hughie and the other children. I must have Lilly with me at the Castle, to make up for the loss of my little Bertha."

"O!" said Bertha, looking a little disappointed; then she added, eagerly, "But, mamma, may I indeed do just like them?—go without a bonnet, take off my shoes and stockings, and wade in the burn, and patter in the nice soft clay?"

"Yes, if Lilly will consent to take your place, and play the little lady at the Castle."

In the afternoon Lady Blantyre sent for Mrs. MacWillie, and between them they arranged that their little daughters should change places on the morrow; and that night both Bertha and Lilly went to bed with their hearts full of happy anticipations, and each pitying the other.

Early in the morning, Lilly was brought to the Castle, and Bertha conveyed to the cottage. Lilly wanted to take with her her pet kitten, but was told that poor little Winkle would be rather too vulgar a visitor for Lady Blantyre's drawing-room. Bertha proposed to take her pretty King Charles spaniel, but was told that the gamekeeper's rough mastiffs and terriers would make nothing of taking him by the neck and shaking the life out of him. So she concluded to leave Frivole behind.

When she reached the cottage, the little MacWillies came around her, full of wonder and shy admiration. They said nothing to her, but they whispered among themselves, and their eyes looked very big and watched her constantly.

"Come here, Sandy and Effie!" she said to a little boy and girl, who stood with their hands behind them, gazing at her as if she really had been a fairy princess. "Do come to me; I am your sister now, don't you know?"

But they only drew back, and as she started toward them, scampered away and hid behind their mother.

"Come, Hughie," said the little lady, "let us go down to the burn. You must make me a wreath like Lilly's, and play with me just as you do with her, won't you?"

Hughie gladly promised, and away they went hand in hand. But the lad could not quite forget that his playmate was the Honorable Miss Bertha Blantyre, so he took the choicest roses from his mother's garden to make a wreath for her, and for the life of him he could not be as free and merry with her as with his sister. However, he was very kind and amusing, and Bertha was in high glee. The first thing she did when they reached the burnside, was to sit down and pull off her shoes and stockings, then she ran up and down the sandy shore of the loch, throwing pebbles and daisies into the water, sailing Lilly's little boat, and laughing and singing like some wild creature. Then she helped Hughie at his dam awhile, patting the soft clay with her dainty little hands.

"O dear!" she exclaimed at last.

"What's the matter, my bonnie leddie?" said Hughie, rather patronizingly.

"My feet smart so! See how big and red they look."

"Sae they do. You hae burned them. The sun is hot this simmer day, and the sand as weel, and ye ken (know) ye are no used to gang without your shoon (shoes); wade a bit, noo, and cool your small saft feet."

Bertha thrust one foot into the water, but drew it out instantly, exclaiming, "Ugh, how cold!"

"Ay, gin (if) ye only dip the tips o' your toes, like a fearsome cat; but gin ye rin bravely intil the water, like a spaniel dog, ye'll no find it cauld," said Hughie, taking her hand and leading her in. But Bertha still thought it cold; she caught her breath, and shrieked at every step, frightened not only at the rising water, but at the tiny fishes within it, and even at the insects skimming along its surface. As Hughie was leading her out, she trod on a stone and cut one of her delicate feet quite severely. Then, when she reached the shore, she found that she could not get on her stockings and shoes, and with her eyes full of tears she said, "Ah me! what shall I do? I can't walk barefoot among the heather, my feet are so sore already."

"O, dinna fash yoursel' (don't trouble yourself) about that, I 'll carry you in my twa arms," said Hughie; and the sturdy little fellow took her and carried her to the cottage.

After having had her foot bound up, and her face bathed in cream, for that was also burned, her pretty wreath having proved a very poor protection from the sun, Bertha was invited to share the midday meal of the children. Being very hungry, she gladly sat up to the table and took her share of milk and oatmeal cakes, or bannocks. She liked the milk, but the bannocks scratched her throat and almost brought the tears to her eyes. She wondered how the others could eat them so ravenously.

After dinner the children did their best to amuse their visitor, by playing games, running, leaping, and tumbling about, all very kindly meant, but rough, noisy, and almost terrifying to Bertha, who was not sorry when the younger ones ran out of the house to play under the trees. Hughie sat by her side on the settle, and told her stories, till she fell asleep. She was very weary, and slept a long while, against some cushions which Hughie placed behind her. When she awoke, she looked around wonderingly, and, missing the dear faces of her mother and nurse, burst into tears.

"What's the matter wi' my bonnie bairn?" asked Mrs. MacWillie, tenderly.

"I—want—to—go—home!" sobbed Bertha.

"And ye shall gae hame; sae dinna greet (weep), my lammie," said the good woman.

In a very few minutes the gamekeeper, who, by the way, had watched the children all the morning, from behind some thick bushes by the loch, to see that no harm befell them, came to the door with the family carriage,—a two-wheeled vehicle, called a "dog-cart," drawn by a shaggy old pony. Bertha was helped into this, and, having taken a kind but rather hasty leave of her rustic friends, was driven, in a little lazy, shuffling trot, towards the Castle. About half-way, who should they meet but Lady Blantyre, driving Lilly MacWillie home in her pony-phaeton! She did not seem to see the dog-cart at all, but dashed by it at a furious rate.

Little Lilly had scarcely had a better day than Bertha. From the first hour of her visit to the Castle she had felt ill at ease, and almost homesick. Everything there was so strange and magnificent, that all the kindness she met with failed to make her feel happy and comfortable. Lady Blantyre devoted herself to her amusement; she showed her the conservatories and the aviaries, and led her through the long picture-gallery. This last was an awful place to Lilly; she was frightened at the array of old-time Blantyres,—fierce soldiers in armor, grim judges in enormous wigs, and grand ladies in vast hoops and stupendous head-dresses.

At lunch, Lady Blantyre had her little guest sit beside her, and pressed her to eat of delicate wild-fowl and luscious fruit. But Lilly was scared out of the little appetite she had, not by his lordship, who sat opposite, but by the solemn footman who stood behind her chair. After lunch, Lady Blantyre played and sung for her, and showed her Bertha's books and toys.

At length she left her alone for a time, while she went to dress. When she returned to the drawing-room she could not see the child anywhere; but presently she heard a stifled sob behind the curtain of a window, looking towards the gamekeeper's cottage. She went to Lilly, and put her arms about her, saying, "What are you grieving about, my dear?"

"Let me gae hame! I maun gae hame!" (I must go home) said Lilly.

"So you shall, darling," replied the lady.

When Lady Blantyre returned from the cottage, she found Bertha in the nursery, sitting on the lap of her kind nurse Margery.

"Well, has my little daughter learned content from this day's experience?" said the lady, smiling.

"Yes, mamma," replied Bertha. "I find that one must belong to the MacWillies, to do as they do, and like it; but somehow, I wish I had been used to their ways from the first, that is, if you and papa had been so too. It seems to me that God meant that all people should live nearly alike, and only have houses just big enough to hold them comfortably, like the nests of the birds; and that all children should run among the hills, and play with the brooks. Did n't he?"

"Perhaps he did, my child."

As for Lilly, she spoke her mind that night, to her pet kitten, as she hugged it in her arms before dropping to sleep. "Are ye na glad that we are na fine ladies, eh, Winkie?"

My first is fair, as when it graced

The bowers of Paradise;

It glows in Cashmere's vale, and climbs

Where snowy Alp-peaks rise:

It glads the peasant-woman's heart,

And the Queen's imperial eyes.

My second is a sacred name,

A name of high renown,

By poets sung, yet common 'tis,

As daisies on the down,

Though ladies grand and royal dames

Have worn it as a crown.

When William's ship rocked in the bay,

Impatient to be gone,

And William took his seaward way

Across our dewy lawn,

To pluck my whole to give her love,

Rose Mary with the dawn.

Rose-mary.

Margaret Grey was a widow, who, with three young children, lived in a small cottage on the estate of Lord Dundale, in Scotland. When her husband died, Margaret had been compelled to give up the land he had farmed, with the exception of a little garden, and a patch of pasturage on which she supported a cow and a shaggy Highland pony, called Rab.

This last was a very important member of the family, as without him the widow could not have conveyed to market the butter and eggs, on the proceeds of which the frugal little household subsisted. For his part, Rab seemed fully conscious of his own important and responsible position in the widow's family, gave up all frisking and frolicking ways, and conducted himself in a staid and sober manner on his way to and from the market-town, and assumed towards the children in their little rides a sort of protecting, patronizing, paternal character, which was really edifying to behold.

Lord Dundale was a young man, very handsome and stately, but gentle and gracious, and much beloved by his family and tenants. The children on his estate looked up to him with loving reverence, as to a superior being, from whom nothing but good and happiness were to be expected by the deserving. For them his youth, beauty, and elegance had especial poetic charms; their sweet, simple affection, their timid, grateful devotion, were laid at his feet,—so that when moving among them he trod on unseen flowers. They loved to hear and to tell of the grand and beautiful things at that fairy palace, the Castle,—a noble old edifice, with massive towers, a moat, a lofty gateway, and an ancient drawbridge and portcullis, which stood high in the midst of great forest-trees.

Lord Dundale, being in delicate health, was able to spend but a few months of each year in Scotland, the climate being too severe for him; but he loved the place of his birth, and was never so happy as when, like Rob Roy, he could say, "My foot is on my native heath."

To his tenants his yearly visit to his Scottish estate was always a season of festivity: they hailed the signal of his return, the running up of a flag on the highest tower of the Castle, with shouts of hearty rejoicing.

The cottage of the Grey was on a shady lane, through which the young lord often rode in the pleasant autumn mornings or evenings, sometimes with a gay party of ladies and gentlemen, guests at the Castle, sometimes, when the hour was early, quite alone, and sometimes with one beautiful dark-eyed lady, fresh as a rose and proud as a lily, who it was said was one day to be the mistress of Dundale Castle. The Grey children, little Effie and Jamie, noticed that when the young lord rode by himself, or with ever so large a party of riders, he never failed to acknowledge their bows and courtesies with a nod and a pleasant word and smile; but that when he and the dark-eyed lady together ambled slowly past, he did not seem to see their wistful little faces at all. So, in their secret hearts, they took something very like a spite against the beautiful Lady Evelyn, and hoped their young lord would change his mind.

One autumn evening, as Margaret Grey rode homeward from the market-town, she noticed that Rab, the pony, was languid and slow, that he hung his head dejectedly, and made no effort to browse along the hedge-rows as usual. She supposed that he was tired with his day's work, but trusted that he would be well in the morning. Alas! when the morning came, poor, faithful old Rab was found dead, stretched out stiff and cold in his paddock!

Effie and Jamie grieved passionately over their lost friend and playfellow. They sat down beside him on the grass, and, looking at his poor, helpless feet, worn in their service, wept bitterly that they would carry them along the lane and up the hillside no more; they patted half fearfully the shaggy neck; which would arch to their caresses never again; they drew back with a shudder, after touching the cold lips which had so often eaten the sweet clover from their hands, and turned with a sense of strange wonder and awfulness from the death-misted eyes, which had always shone upon them with an almost human affection.

Margaret Grey wept also,—fewer tears than her children, but sadder. She had many sweet and mournful memories connected with poor Rab. Her dear old father gave him to her on her eighteenth birthday. She remembered many a joyful gallop on his back, through the lanes and over the moors. She remembered how sometimes she rode him slowly, with his rein on his neck; for young Angus Grey walked by her side and told her pleasant news,—always pleasant and interesting, though always about the same thing. She remembered how once he checked Rab's rein under the shade of a hawthorn-tree, and asked her to be his wife. She remembered, too, how Rab had borne her to the Kirk, to be married to Angus Grey; and she thought of three other Sundays when he had carried her and her baby to the christening; and of yet one other time, when he had drawn slowly away from her door a hearse, whereon lay the beloved husband and father. She thought, too, with tender anxiety, that now the last help of the widow, her humble fellow-laborer, was taken from her; and the grim wolf of want and hunger seemed to stand in poor dead Rab's place. Even the baby seemed to feel something of her anxiety and distress, and put up its pretty lip to cry; so to comfort it and to calm herself by her usual household labor, she returned to the cottage, leaving Effie and Jamie still sitting beside old Rab. Their grief had somewhat moderated; yet they sobbed as they talked of the virtues of the deceased, and wondered what life would be without him.

"Ah, Jamie," said Effie, "inna you wish the Lord was here now? You ken mither told us how He cured sick folk, and how He once made a mon alive again that had been dead four days. He could make our Rab alive wi' a touch of His finger, gin (if) He would try, Jamie."

Wee Jamie was a simple-hearted child, scarcely four summers old: his little brain was easily bewildered. For him there was but one Lord, the good and generous young nobleman at the Castle. Of his power and goodness Jamie could believe anything, and though he opened his eyes wide at his sister's story, his face grew radiant with joy, as just at that moment he caught sight of Lord Dundale trotting slowly down the lane on his beautiful thoroughbred bay mare. In a moment he was over the fence, in the road, in the very path of the rider, crying out in an agony of entreaty, "Stop, stop, my lord! our Rab is dead; ye maun (must) make him alive again!"

Lord Dundale checked his horse, and looked down on his little petitioner in silent astonishment, while Mrs. Grey ran out of the cottage, with baby in her arms, and, catching hold of Jamie, strove to lift him out of the way. But the little fellow resisted sturdily, crying still, "Let him make Rab alive! He maun make him alive!"

"But, my little fellow," said the Earl, smiling, "if Rab is really dead,—and I am very sorry to hear it,—I cannot make him alive: how could you think of such a thing?"

But Jamie stood his ground, answering, "My mither says you once made a big mon alive after he had been dead four days. Rab is only a sma' pony, and he's been dead but a wee bit while; so it's na a hard job for you. Dinna say you will na do it."

"What can the little lad mean, Mrs. Grey?" asked Lord Dundale, utterly bewildered.

"I dinna ken (do not know), my lord," she replied, "unless, Heaven save us! he takes you for the Lord of lords. I didna think the bairn was so heathenish and so daft (foolish). You maun forgie (must forgive) the poor child."

Lord Dundale dismounted, and, taking the little fellow by the hand, by a few simple questions, soon found that this was indeed Jamie's strange delusion.

"My poor little laddie," he said, "you are wofully mistaken. I cannot bring your dear old pony back to life. You can never play with him, or feed him, or ride him among the heather or along the burnside again. Rab's work is done, and it is time he should rest. But, Jamie, I can give you another pony in his place, one that I hope may serve your good mother as well as Rab, and that you and Effie must love for my sake. And now good by. I hope Jamie will yet know well the Lord most great and good and loving, the only true Lord of life and death."

Taking a kindly leave of Mrs. Grey, the young Earl then rode on, but in the course of the day the groom of the Castle galloped down to the widow's cottage, leading the new pony, a handsome, sturdy little animal, and so gentle and docile that not only Jamie but timid little Effie could ride him with safety; and even the baby, when set on his back, played with his mane and answered his whinny with a triumphant crow.

So Jamie's faith, though mistaken, was rewarded; and his innocent, fervent little prayer was answered, not by a Divine miracle, but by a generous human heart, which also found its reward in proving the truth of the Master's words,—"It is more blessed to give than to receive."

If my studious Lillian,

This charade will careful scan,

With knit brow and red lips pursed,

She will then unconscious show

To all such as care to know

An example of my first.

My second is what divine truths are,

And Alpine heights that gleam afar,

And hills of Scottish heather;

And what are not all human blisses,

The little loves of little misses,

Winds, waves, and April weather.

If from my second some sad dawn

You find your favorite palfrey gone,

Don't lock the door, and don't

Sit down and cry. To chase the thief

Despatch my whole: it's my belief

He 'll catch him, or—he won't.

Con-stable.

Philip Alfred Reginald, Lord Alverley, only son and heir of the Earl of Ellenwood, was taking a morning walk in the park of Alverley Castle, in the beautiful county of Wicklow, Ireland. He was a very little lord indeed, only about six years old, and he was accompanied by a very stout nurse, Mrs. Marsham, quite a dignified and important personage. The family had but the day previous arrived from London, after an absence of four years.

Philip was an only child, fondly beloved by his parents, and, as the heir to a great estate, much petted and flattered by all about him. He was a pretty child, always richly and daintily dressed, and had much the air of a little courtier, or the pet page of some gay young queen.

This morning, as Mrs. Marsham led him down one of the broad walks of the park, they encountered a little peasant lad, who looked a good deal impressed, but saluted the small nobleman with a bashful bow, and was about hurrying on, when the lordling asked, condescendingly, "What is your name, little boy?"

"Arty O'Neill, may it please your lordship," was the reply.

"What, a son of Norah O'Neill?" asked Mrs. Marsham.

"Yes, ma'am."

"Why, then, my lord, he is your foster-brother. Norah O'Neill, the lodge-keeper's wife, was your first nurse, and a very good creature she is, I believe," said Mrs. Marsham, attempting to move on.

But Philip, who had always, in spite of his grandeur, felt a little lonely, was caught by the term "foster-brother," and held back to examine the boy more attentively, and to ask him several childish questions.

In spite of his uncouth dress, Arthur or Arty was a fine-looking little fellow, and though modest, was by no means awkwardly shy; so the small folk got along very well together. The next day Philip insisted on making a visit to the lodge, where he was greeted by his old nurse Norah with an exhibition of true Irish emotion,—tears, laughter, and passionate caresses, that rather annoyed than gratified him. "What a fine little gentleman he has grown, bless God," she exclaimed, wiping her eyes with her apron.

"Yes," replied Mrs. Marsham, "and your Arty is also a fine, sturdy little lad. Was he not a delicate baby?"

"Ah, yes indeed, ma'am; we did n't think to raise him till he was well past three. Then he grew stout and rosy, and sturdy on his legs, the saints be praised!"

A day or two later, the weather not allowing of walking, Philip felt lonely, and sent for Arty to come and play with him. The child went, and returned to the lodge at night quite loaded with playthings, the gifts of the little lord and his mother. After this he was often sent for from the Castle, and gradually became a decided favorite with Lord and Lady Ellenwood, and consequently with all their retainers. As for Philip, he soon grew devotedly fond of his peasant playmate, and declared he could not live a day without him; and, as his will was already law at the Castle, even this whim for a companionship quite unsuited to his rank was indulged.

Norah O'Neill dressed her son in his best for those grand visits; but even his holiday suit was soon pronounced too rude for his new position, and an entire new wardrobe was provided for him. It was a pretty page-like costume, and singularly becoming, so much so that Lady Ellenwood, after regarding him with a pleased smile for some minutes, remarked to Mrs. Marsham, "Really, that child has something superior about him; I certainly should not take him for a peasant boy."

"Indeed, my lady, you surprise me. The child is well enough for an O'Neill, but he lacks the noble look, after all. I can see the common bird through all the 'fine feathers.' Only mark, my lady, the vast difference between him and my little lord."

"Ah, yes, I can see that Philip is the more dainty and delicate, but Arty is, in some respects, the handsomer child of the two; and, in truth, I think he has quite a high-bred look. There is a certain resemblance to my own family, which struck me when I first saw him. He has decidedly a Cavendish nose, and I have heard my old nurse say that my hair was once of that same golden auburn. I have never seen a child of any rank that my heart has been so drawn towards as towards this same little O'Neill. Surely we must do something for him."

This partiality for the lodge-keeper's child did not prove a mere fine lady's passing freak. Like little Philip, she grew more and more fond of little Arty; and when, after a six months' stay in Ireland, the noble family returned to London, little Arthur, really though not formally adopted, went with them. He received his earliest instruction with Philip from a kind governess, with the best of care and the most affectionate counsel. Lady Ellenwood was very gracious and motherly towards him, and the Earl always kind; yet he never forgot his humble Irish parents, whom he was allowed to visit every year.

Thus years went on, and Arty was regarded as a beloved member of that high family,—as the chosen friend, the brother elect, of his young master. They were taught by one tutor, and finally sent to school together, always keeping along hand in hand, in the utmost brotherly good feeling, with a great, tender love between them,—a love neither tainted by haughty condescension on the one side, nor by flattering subserviency on the other. It was a beautiful and marvellous affection.

At length the lads were spending their last vacation at home, in the old Castle in Wicklow. They were nearly sixteen, and as fine looking, gallant lads as the country could boast. Such loving, inseparable companions were they, that they were playfully named "David and Jonathan."

The pleasure of this visit to the Castle was only marred by the illness of Mrs. O'Neill, who was thought to be in a decline. Arthur, though so far removed from his simple life by the patronage of the great, had always been a good and dutiful son, while Philip had ever evinced a remarkable fondness for the warm-hearted foster-mother, whose sad blue eyes dwelt on his merry face with a singular expression of yearning, sorrowful tenderness.

It was the sixteenth birthday of Philip, Lord Alverley, and his happy parents gave a ball in honor of the occasion. All the "best people" of the country were present, and all was brightness, music, and gayety,—joyous hearts keeping time to light, dancing feet. But, in the midst of the festivities, the young lord of the fête and Arthur were summoned from the ball-room by Terence O'Neill, the lodge-keeper, who came to tell them that his poor wife had taken a turn for the worse, and was sinking rapidly, and that she desired to see her two dear lads before she should pass away.

Without a moment's hesitation the friends set out together for the Lodge. Terence O'Neill left them there and hastened away to summon the parish priest. So it happened that the lads found themselves alone by the bedside of Norah O'Neill. They sank on their knees beside her and burst into tears. The dying woman gazed at them with a look of wild, passionate love, which seemed struggling with a strange fear, or remorse.

"O my poor lads!" she said, "I have loved ye both, yet ye have both much to forgive. When the priest comes I will tell you before him all my sin,—all the wrong I have done ye both."

They looked bewildered, but waited silently and patiently for the coming of Terence and the priest. But the anxious minutes went on, and no one came. At last Norah half raised herself in bed and hoarsely whispered, "He does not come, and I am dying! I must confess to you, boys; but if you can't forgive, don't curse your poor broken-hearted mother when you know all. You, Arthur, are not my son, though you were nursed at my breast, and became like the very pulse of my heart. You are the Earl's own son; and you, Philip, are not Lord Alverley; you are my first-born, my only son. I changed you in your cradles. The Countess was very ill for weeks, the Earl never left her to visit her poor, puny baby. It was sickly; I was sure it would die; I was tempted to put my own healthier child in its place. I meant a kindness to my lord and lady, yet I have never known an hour's peace since that day. Nobody knew my secret, not even my husband, for he was away in England, with some harvesters, at the time. He never suspected. I never dared lisp a word of it to the priest. I shut it all close in my heart, where it stung like a serpent and ate like a poison. It is killing me. O my poor, dear, injured lads, can you forgive me before I die?"

There was an agony of supplication in the straining eyes and in the broken sob.

Philip spoke first, very tenderly: "As for myself, mother, I forgive you, though you have wronged me by making me a party to a great wrong; but it was very wicked of you to keep so noble a boy as Arthur so long out of his rights."

"O no," cried Arthur, "I have really suffered no wrong. God so wonderfully overruled the evil for good. I have had all the happiness I could have had as the heir of Ellenwood Castle, and added to it, your love, my more than brother. So, mother dear, I too forgive you, fully and freely, and do not despair of God's forgiveness, now that all is well between us three."

Norah O'Neill lifted her bowed head and stretched out her arms with a cry, half joy, half sorrow, then fell back on her pillow. A mist gathered over her eyes, and she spoke no more, but her hands groped about till they found a hand of each of her boys. These she raised one after the other to her lips, and, meekly kissing them, she died.

The poor lads had never looked upon death before: they were both awe-struck, silent, and motionless for a while. Then Philip bent down and closed his mother's eyes, and pressed his lips on her forehead. But Arthur spoke first. Laying his hand on Philip's shoulder, he said, in a tone of eager imploring, "Dear brother, we two only know of this sad revelation. Let us bury it in our hearts, and let all be as though this had never been. You are far better suited to your present position than I am. You are one of Nature's noblemen. It would make me wretched beyond expression to have to take from you wealth, title, parents, everything. I would rather die. Let us both keep a life-long silence about this sad affair. I beg, I implore you."

"O Arthur!" cried Philip, reproachfully, "I did not look for this from you. Though a peasant born, it seems, I am not base enough to do anything so dishonorable as that. You are the last one I would wrong. I will strip myself of everything that belongs to you. You shall have your birthright."

"I will not take it, Philip."

"You must take it, and you will yet see it is right for you to take it. But we have never quarrelled yet, and we must not begin by the side of our dead mother. Ah! here comes O'Neill, my father. We will not tell him all now."

The lodge-keeper, coming too late with the priest, was so absorbed by his grief that he noticed nothing unusual in the manner of the lads, scarcely knew when they took leave of him and returned home.