The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Sequel, by George A. Taylor

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net

Title: The Sequel

What the Great War will mean to Australia

Author: George A. Taylor

Release Date: December 2, 2008 [EBook #27382]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE SEQUEL ***

Produced by Nick Wall, Graeme Mackreth and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

First Edition, June. 1915.

2nd Edition. July. 1915.

Printed and Published by Building Limited.

17 Grosvenor Street. Sydney,

Australia.

1910.—"The Air Age and its Military Significance."

1911.—"The Highway of the Air and the Military Engineer."

1913.—"The Balkan Battles." How Bad Roads Lost a War.

1913.—"The Schemers." (A Story.)

1913.—"Songs for Soldiers."

1914.—"Town Planning for Australia."

"Ah! when Death's hand our own warm hand hath ta'en

Down the dark aisles his sceptre rules supreme,

God grant the fighters leave to fight again

And let the dreamers dream!"

—Ogilvie.

These are mighty days.

We stand at the close of a century of dazzling achievement; a century that gave the world railways, steam navigation, electric telegraphs, telephones, gas and electric light, photography, the phonograph, the X-ray, spectrum analysis, anæsthetics, antiseptics, radium, the cinematograph, the automobile, wireless telegraphy, the submarine and the aeroplane!

Yet as that brilliant century closed, the world crashed into a war to preserve that high level of human development from being dragged back to barbarism.

And how the scenes of battle change!

Cities are being smashed and ships are being torpedoed. Thousands of lives go out in a moment. And these tremendous tragedies pass so swiftly that it is risky to write a story round them carrying any touch of prophecy. I, therefore, attempt it, realising that risk. The story is written for the close of the year 1917. Its incidents are built upon the outlook at June, 1915.

It first appeared in an Australian weekly journal, "Construction," in January, 1915, and already some of its early predictions have been realised; as, for instance, the entry of Italy in June, the use of "thermit" shells, and the investigation of "scientific management in Australian work."

To many readers, some of the predictions may not pleasantly appeal. But it must be remembered that, being merely predictions, they are not incapable of being made pleasant in the practical sense. In other words, should any threaten to develop truth, to materialise, all efforts can be concentrated in shaping them to the desired end.

Predictions are oftentimes warnings. Many of these are.

The story is written to impress the people, with their great responsibilities in these wonderful days—when a century of incident is crowded into a month, when an hour contains sixty minutes of tremendous possibilities, when each of us should live the minutes, hours, days and weeks with every fibre strained to give the best that is in us to help in the present stupendous struggle for the defence of civilisation.

GEORGE A. TAYLOR.

Sydney, Australia, June, 1915.

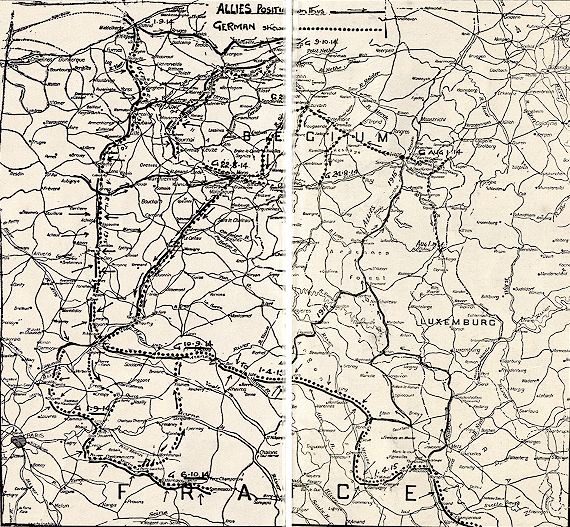

The map, on pages 6 and 7, shows the lines followed by the German armies through Belgium and France during August and September, 1914. The main line of the Allies' attack, through Metz, in August and September, 1915, culminating in the defeat of Germany (predicted for the purpose of this story) is also shown.

You can facilitate the early realisation of this prediction by enlisting NOW.

They often met before and fought.

To gain supremacy in sport.

They meet again now side by side.

For freedom in the whole world wide.

Winged!

It was the second day in February, 1915.

I'll not forget it in a hurry. That day I fell into the hands of the German Army. "Fell," in my case, was the correct word, for my monoplane was greeted with a volley of shots from some tree-hidden German troops as I was passing over the north-eastern edge of the Argonne Forest.

I was returning from Saarbruck when I got winged. Bullets whizzed through the 'plane, and one or two impinged on the engine. I tried to turn and fly out of range, but a shot had put the rudder out of action. An attempt to rise and trust to luck was baulked by my engine losing speed. A bullet had opened the water cooler, and down, down the 'plane glided, till a clear space beyond a clump of trees received it rather easily. I let the petrol run out and fired it to put the machine out of use. Then a rifle cracked and a bullet tore a hole through my left side, putting me into the hospital for six weeks.

That forced idleness gave me plenty of time for retrospection.

I lived the previous energetic five months over and over again. I had little time before to think of anything but my job and its best possibilities, but the quietness of the hospital at Aix la Chapelle made the previous period of activity seem a nightmare of incident.

I remember how surprise held me that I should be lying wounded in a German hospital—I, a lieutenant in the Royal Flying Corps, who for years before the war, had actually been a member of an Australian Peace Society!

Zangwill's couplet had been to me a phrase of force:—

"To safeguard peace—we must prepare for war.

I know that maxim—it was forged in Hell!"

I remembered well how I had hung on the lips of Peace Advocate Doctor Starr Jordan during his Australian visits, and how I had wondered at his stories that Krupp's, Vicker's, and other great gun-building concerns were financially operated by political, war-hatching syndicates; that the curse of militarism was throttling human progression, and that the doctrine of "non-resistance" was noble and Christianlike, for "all they that take the sword shall perish by the sword."

I remembered how in Australia I had grieved that aviation, in which I took a keen interest as a member of the Aerial League, was being fostered for military purposes instead of for that glorious epoch foretold by Tennyson:—

For I dipped into the future far as human eye could see,

Saw the vision of the world and all the wonders that would be,

Saw the heavens filled with commerce, Argosies of magic sails,

Pilots of the purple twilight, dropping down with costly bales.

I remembered I felt that the calm of commerce held far more glories than the storm of war; that there was no nobler philosophy than:—

"Ye have heard it said, an eye for an eye, and a tooth for a tooth; but I say ... resist not evil; but whosoever shall smite thee on thy right cheek, turn to him the other also. If any man take thy coat, let him have thy cloke also."

Then came the thunderclap of war; and in the lightning flash I saw the folly of the advocacy of peace. I felt that I, like others, had held back preparation for this great war, that had been foreseen by trained minds. I felt that extra graves would have to be dug, because dreamers—like myself—had prated peace instead of helping to make our nation more secure.

"Non-resistance" may be holy, but it encourages tyranny and makes easy the way of the wrongdoer. If every man gave his cloak to the thief who stole his coat, there would be no inducement for the robber to lead an honest life. Vice would be more profitable than virtue.

"Non-resistance" may be saintly, but it would make it impossible to help the weak or protect the helpless from cruelty and outrage.

All law, all justice, rests on authority and force. A judge could not inflict a penalty unless there were force to carry it out.

Creeds, after all, are tried in the fires of necessity. "They that take the sword shall perish by the sword." Well, the Kaiser had grasped the sword. By whose sword should he perish except by that of the defender?

Christ's teachings are characterised by sanity and strength. He speaks of His angels as ready to fight for Him; He flogged the moneychangers from the temple: He said that no greater love can be shown than by a man's laying down his life for his friend; and the Allies fighting bravely to protect the oppressed, were manifesting to the full this great love. Germany's attack on a weaker nation, which she had signed to protect, called for punishment from other nations who had also pledged their honor.

Unhappy Belgium called to the civilised world to check the German outrages on its territory and people.

My peace doctrines went out like straw before a flame. I was a "peace-dove" winged by grim circumstance; and that is how I became a man of war.

HOW HISTORY REPEATED ITSELF.

England to Belgium, in 1870: "Let us hope they (Germany) will not

trouble you, but if they do—"

(Tenniel, in "London Punch," at the time of the Franco-Prussian War.)

The First Three Months of War.

I was in England when the war cloud burst, having just completed a course of aviation at the Bristol Flying Grounds; so I volunteered for active service; and, after a month's military training, was appointed a lieutenant in Number 4 Squadron of the R.F.C.

I remember how the first crash of war struck Europe like a smash in the face. How armies were rapidly mobilised! How the British Fleet steamed out into the unknown, and Force became the only guarantee of national safety!

It is hard to write of these things now that many days have passed between, for events followed each other with the swiftness of a mighty avalanche.

How Germany thrilled the universe by throwing at Belgium the greatest army the world had ever seen. An awful wave of 1,250,000 men crashed upon the gate of Liege.

How the great Krupp siege guns slowly crawled up, stood out of range of the Liege forts, and broke them at ease.

How through the battered gate a flood of Uhlans poured to make up for that wasted fortnight, preceded by their Taube aeroplanes spying out the movements of the Belgium army; the German artillery following, and smashing a track through France!

How that fortnight gave France and England the chance to interpose a wall of men and steel, which met the shock of battle at Mons, but was pushed back almost to the gates of Paris.

It was at the battle of Mons that the squadron to which I was attached went into active operation, reconnoitring the battle line on our left flank. It was my first taste of battle, but I do not remember any strange feelings.

I was in that awful shock of forces that stopped the southern progress of the German juggernaut like a chock beneath a wheel, when on September 2 it recoiled back—back to the Marne—back to the Aisne—back almost to the Belgian frontier. Then winter dropped upon it, turning the roads into pools of mud, checking all speed movements necessary to active operations, and the troops dug in like soldier crabs upon a river bank.

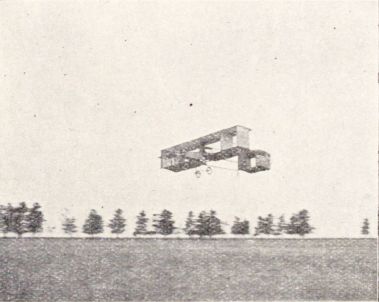

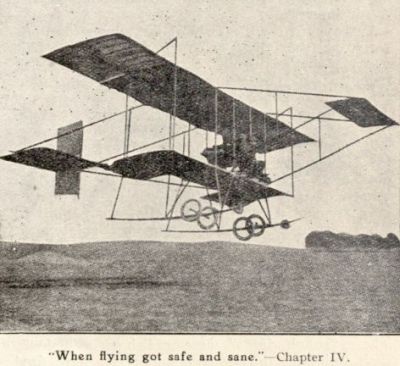

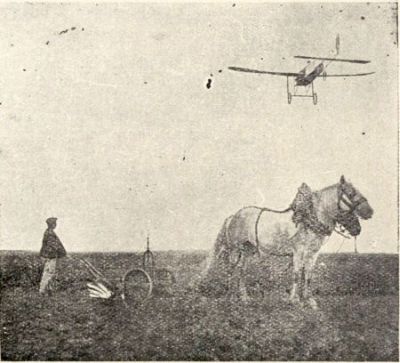

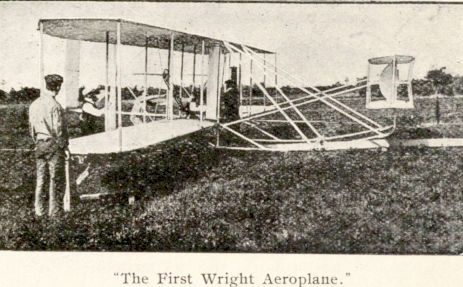

"The Aeroplane had been a ... curiosity."—Chapter III.

(The first Aeroplane to fly in Australia.)

All surprise movements had to be made at night; the dawn finding our aeroplanes out in the frosty air spying out any changes in positions of the day before. A smoke-ball fired as we flew above a new trench gave our artillery the range; then till night fell a rain of shells would batter that new position. In the dark our troops would creep forward, rush that trench, and dawn would find them dozing in their newly won quarters. The war had become a battle of entrenchments.

The Flying Men.

For ages man walked the earth.

To-day he is the only living creature that can travel in the air by other than its own substance.

'Till the Great War the aeroplane was a scientific curiosity. The Battle of the Nations blooded it; and its wonderful utility in speeding the end of the war has proved its right to be recognised as a distinct factor in human movement.

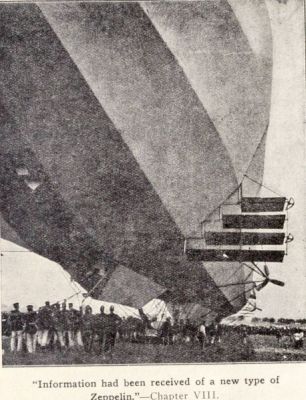

When the war crash came there were two aerial types; the lighter than air type, the dirigible balloon; and the heavier than air machine, the aeroplane. This is how the Powers stood in aerial furnishing when the first shot was fired. Germany and Austria had 25 airships, including 11 Zeppelins, as well as 556 aeroplanes.

England, France, Russia and Belgium had 33 airships and 1019 aeroplanes.

The English dirigibles had not made long flights, and not being very dependable had not received much attention from the military authorities. A non-dependable factor in war is worse than useless. A mistake may be made in tactics, but when ascertained may be retrieved and, perhaps, turned to good account. Non-dependability is fatal, as many a commander would not know how to act, and in war, he who hesitates is lost.

The French had experimented a good deal with the dirigible, but mostly of the non-rigid type, which was a type "without a backbone" and was as uncertain, so that its general non-dependability turned French attention to the aeroplane.

The Germans, however, pinned their faith on the balloon, and for long made it a feature for observation purposes, so that when Zeppelin brought out his rigid framework balloon, Germany fancied she saw in it the command of the air.

The Zeppelin, however, had many disabilities over the aeroplane. It had to have its own kennel. It was almost impossible to get it into its shed if the wind was against it. The kennels had, therefore, to be either on wheels or floating. Furthermore, not being able to replenish its gas, a Zeppelin had always to return to its base for supplies. But the gas balloon suited the smug character of the German. Unlike the aviator who threw himself into the air on a bundle of steel rods and rubber, a propeller and a petrol engine, the phlegmatic German took no risks with a balloon. He found, however, that Zeppelins were expensive freaks. They had a habit of catching fire in the air, because the tail created a vacuum and sucked back some escaping gas into the engine where the contact spark ignited it.

One recently alighted in a field and a country bumpkin came over with the crowd to see the fun. He had a pipe in his mouth. He was told to go away. He wouldn't for a while, but he soon left in a hurry. After the explosion they found bits of him and sixty-seven other people!

The Germans pinned their faith to the Zeppelin because it could carry a heavy load of explosives and would be an easy way of damaging an enemy; and it was only a few months before the war that considerable enthusiasm ruled Germany because a Zeppelin had made a record trip from the southern to the northern fringe of Germany, or, as "Vorwarts" said, "as far as from Germany to England and back again."

Here, then, was an easy way to fight. Just rise up out of danger and drop bombs.

They tried it at Antwerp.

On 25th August, 1915, a Zeppelin flew over the sleeping city, guided by flash lamps from German spies on roofs. It was a night of terror—a bomb dropped to fall upon the royal palace, missed and injured two women; a bomb aimed for the Antwerp Bank missed and killed a servant; but one fell into a hospital and another into a crowd in the city square. Five people were blown to atoms.

It must have been an awful night, for it is recorded that the city watchman of Antwerp announced: "12 o'clock and all's hell."

On September 2nd (the anniversary of Sedan), the Zeppelin came again to give its stab in the dark, but finding it was recognised, retreated. It did not rise higher to get out of danger of the air guns and put up a fight. The German in the air takes few risks. It is his temperament. Not so with the Frenchman. He is by nature dashing and volatile. The easy-going of the dirigible little appealed to him. The risk, the speed, the adventure of the aeroplane touched his soul, which explained why France had 2032 military aviators, whilst Germany had only 300 qualified military pilots.

The German lacks the dash, nerve, vim and initiative essential to a successful flier. He is moulded as a cog. He is part of a system—out of that he must not move. It has wrecked his initiative, and the sneer of the greatest German in history, Frederick the Great, has to-day grim significance.

"See those two mules," he said satirically to one of his officers, who lacked initiative, "they have been in fifteen campaigns and—they're still mules."

The German training system has taken all the humanity out of the men. They move like machines, either destroying or rolling on to destruction, and they often act with the dumb sense of the machine to pain and suffering.

Lloyd George has very truly put it: "God made man to his own image, but the German recreated him in the form of a Diesel engine."

No one questioned the efficiency of the German machine. The Allies were disputing its right to go on destroying.

"The New Arm."—Chapter IV.

The New Arm.

"It strikes me that these fool commanders don't know what to do with us. We aviators seem to be too new to come into all their stunts. Here we've been flying over eight years, and we're still novel enough to be repeatedly fired on by our own side. Why the beggars in our own battery, when they see an aeroplane overhead in their excitement let fly. They don't bother to notice that the plane of our Bleriot hasn't claw ends like the enemy's Taube. Neither do they note we carry our own distinguishing mark. We're the circus show. We're the 'comic relief' sure."

He was about to spit his disgust on an unoffending fly, but quickly changed his mind.

He was a Yank from the U.S.A. Military School at San Diego, and "hiked over the pond as there was nothing doing."

In appearance he was tall and wiry with a thin face and hooked nose that suggested the bird-man. His name on the roll was Walter Edmund Byrne, but his bony appearance won him his nickname—Nap.

We knew nicknames would shock those who stand for the rigid rule of military discipline, but aviators clear the usual wall of demarcation between officers and subordinates. A nod supplants the "heels together and touch your cap."

The Aviation Sections seemed to be communistic concerns, in the air rank being only recognised by achievement. In fact, the new arm was too new to be brought under the iron rule of military etiquette or into most Operation Orders. I told Nap as much.

"Yes," he said, "I guess we're too new. Even when cannon first came into war it was novel enough to fire as often from the wrong end and teach things 'to the man behind the gun'; but I've a bit of dope here that ought to be pasted into every book of your field service regulations, and every officer ought to repeat it before breakfast three times a week. It's the flyers' creed."

Fumbling amongst some newspaper scraps in his note book, he produced this bit of verse.

The snake with poisoned fang defends

(And does it really very well).

The cuttle fish an inkcloud sends;

The tortoise has its fort of shell;

The tiger has its teeth and claws;

The rhino has its horns and hide;

The shark has rows of saw-set jaws;

Man—stands alone, the whole world wide

Unarmed and naked! But 'tis plain

For him to fight—God gave a brain!

Far back in this world's early mists

When man began to use his head;

He stopped from fighting with his fists

And gripped a wooden club instead.

But when the rival tribe was slain,

The first tribe then to stand alone

Had once again to work its brain

And made an axe—an axe of stone!

The stone-axe tribe would hold first place;

And ruled the rest where'er it went.

Because then—as to-day—the race

Was first that had best armament.

But human brain expanding more

(Its limits none can circumscribe);

The stone-axe crowd went down before

The more developed bronze-axe tribe.

Then shields came in to quickly show

Their party victors in the strife:

By warding off the vicious blow

And giving warriors longer life.

The tribe's wise men would urge at length,

No doubt as now, for tax on tax,

To keep the "Two tribe" fighting strength

With "super-dreadnought" shield and axe!

The bow and arrow came and won

For Death came winged from far away.

Then came the cannon and the gun;

And brought us where we are to-day.

And now we see the shield of yore

An arsenal of armour plate;

With crew a thousand men or more;

And guns a hundred tons in weight.

Beneath our seas dart submarines,

Around the world and back again.

But every marvel only means

Some greater triumph of the brain.

For while the thund'ring hammers ring;

And super-dreadnoughts swarm the sea;

There flits above, a birdlike thing,

That claims an aerial sovereignty!

A thing of canvas, stick and wheel

"The two-man fighting aeroplane."

It screams above those hulks of steel:

"Oh! human brain begin again."

Nap was busy with bad language, a size brush and some fabric remnants patching the plane, whilst I read his treasure by my pocket lamp. Then he came over.

"Mind you," he said, "I don't greatly blame folks here. It can't be worse than in America—America, where the first machine got up and made good—where the man the world had waited for for ages, Wilbur Wright (though he's been dead some years), hasn't even got a tablet up to say: 'Good on you old man, God rest your soul.'"

We were standing by our machines, waiting for the dawn light to call us aloft for our daily reconnaissance when Nap let his tongue loose.

"Five years ago, when the Wright Brothers first flew, Europe went dotty and began to offer big prizes for stunts in the air. Wright took his old 'bus across the pond and won everything. Next year our Glen Curtis went over and brought back all the scalps. Then America got tired. We live in a hurry there. We're the spoilt kids of the earth, always wanting a new toy. When we tired of straight flying, we went in for circus stunts; such as spiral turning, volplaning, upside-down flying and looping the loop. We interested the crowd for a while, as there was a chance of some of us smashing up. But when flying got safe and sane and the aeroplane almost foolproof, the public got cold feet, and the only men flying when I left, were young McCormick, the Harvester chap of Chicago, occasionally hiking across Lake Michigan in his 'amphoplane,' and Beechy, dodging death in 'aeroplane versus automobile' races.

"Curtis has a factory that had been shooing the bailiff till Wanamaker came along and financed that Atlantic aeroplane that was too heavy to carry its weight; and Lieutenant Porte, who was to take it across, was in a fix till this war came along and called him over. Orville Wright is trying to make a do of his factory. It is significant that Captain Mitchell, of the U.S. Signal Corps, the other day asked the U.S. Government 'to help those fellows out or they'll have to quit the business.' So you see Jefson, that's why I get the huff when I see the same sort of thing over here, especially in times like these 'that try men's souls.'"

Then the dawn light streaked the eastern sky rim. We pulled the plane from under the tree screen. The propeller hummed, dragged us across a dozen yards and up into the cold air of the early New Year morn.

"When flying got safe and sane."—Chapter IV.

The Tired Feeling.

Our quarters were outside Epernay, about fifteen miles south of Rheims, with the Marne between us and the enemy.

To the north the horizon was fringed with the ridge-backed plateau cut by the Aisne. The enemy had been holding that fringe since October, having pushed back our almost daily attempts to get on to it. We got a particularly bad smack early in 1915, after crossing at Soissons.

To the north east was the ridge covered by the Argonne Forest; a sealed area to the man in the air.

We had been here three months, and our daily flight over the same area robbed the view of any scenic interest.

Perhaps, in the clear air of the winter morning, we would see far off silhouetted against the pale green of the brightening eastern sky, the dove-like aeroplanes of the enemy moving over the distant forest like bees above a bush.

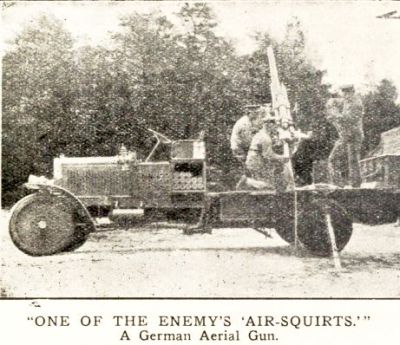

Sometimes an "affair of aerial patrols" would result in the exchange of long shots, but seldom with any effect, for the reason that our enemy took few risks in the air and, furthermore, we could not pursue, as our orders were for speedy reconnaissance and early report. This was no easy matter over a country covered with the snowy quilt of winter, when even trees were unrecognisable, except at an angle that would show the trunks beneath: an angle that would call for low flying, bringing us within the 6000 feet range of the enemy's "air-squirts."

By day we "trimmed our ship," examined every screw and bolt and inspected our bombs and fuses. These "cough drops" were radish-shaped shells, each weighing thirty-one pounds; and were fired from an apparatus which could be worked by the pilot and which carried a regulator showing height and speed of the machine. Fair accuracy could thus be achieved.

One evening, the commander of the battery to which we were attached came over to our quarters, the skillion of a wrecked farm house.

He brought word that another Zeppelin had been rammed by one of our machines. Both machines and their occupants had been smashed.

He spoke in French, and we understood, which explained why we were stationed so far east on the fighting line.

"Magnificent it must have been," he said, "we groundlarks always have a fighting chance, but there is no chance for you bird-men. Ah! who can now say the romance has gone out of war with the improvement in range of weapons. Time was not long since when the general headed his men with a waving sword. As your Shakespeare said it—'Once more into the breach, dear friends.' And my comrades are fighting through this campaign, banging at an enemy they may never see. But the aeroplane has brought back the romance again. Ah! it is fine."

When he strolled out Nap ventured his opinion.

"Romance in war! There's not a scrap of it. The fool-flyer who rams a Zepp. deserves what he gets. It's wasteful for a flyer to so risk his speedy plane, when he has a better fighting chance of rising and dropping 'cough-drops' on the slow old 'bus beneath him; as Pegoud told us the other day: 'The Zeppelins! Ah, they are slow as geese, but our aeroplanes, they are swift as swallows.'

"The trouble is there's not enough opportunity here to do things. This daily 'good-morning fly' and cleaning engines the rest of the day is getting on my nerves, we've been marking time here for months. I want something to happen along 'right soon.'"

And something did happen along next morning.

Civilised Warfare.

Nap was in a bad humor.

The breeze from the north-east had kept us up for three days. It came to us over fields of long-unburied dead. It explained our morbid craving for tobacco—and Nap, during the night, had lost a cherished half-cigar!

We felt the cold that morning, as we wheeled the 'plane into the open space. The engine was also out of sorts, coughing like an asthmatic victim.

The first sun ray shot into the sky and called us aloft. So with engine spluttering the 'plane climbed over the Marne-Vesle Ridge and above the cloud of smoke that hid Rheims 5000 feet below us.

Looking far to the north-west, a great fog cloud lay over the wet country of the Yser. About twenty-five miles off, near Laon, we spotted one of the enemy's observation balloons being inflated.

"Shall we drop a 'cough-drop'?" Nap shouted to me through the speaking tube.

"No chance," I shouted back, "there's something coming at us."

A swift Taube was racing up to challenge. It was rising to get the "drop" on us. We carried an aerial gun, but hesitated to fire, as we wanted all our speed to get above our rival. Our engine lost its bad temper for a change. Round and round we began to circle like game cocks spoiling for a fight; rising, forgetting, in the excitement, the cold of the upper air—higher and higher, till Nap shouted, "We'll get her beneath us in the next round and then for a 'cough-drop' or the gun."

But the Taube had seen our advantage. It banked up on a sharp turn, dropped like a stone fully a thousand feet, making a magnificent volplane, and scurried away like a frightened vulture, dropping and dropping in a series of gigantic swoops.

"We won't chase," said Nap, "she wants to bring us into range of their 'air-squirts,' and 'Archibalds' are not pleasant on an empty stomach."

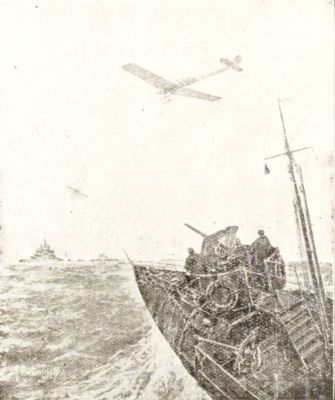

"ONE OF THE ENEMY'S 'AIR-SQUIRTS.'"

A German Aerial Gun.

We turned home and then the engine sulked again. I could see Nap was in trouble. It was was just as well that the roar of the engine and the hum of the propeller compelled the use of speaking-tube communication, for when a man uses bad language he isn't cool enough to pour his sentiments through a pipe. But we were coming down, gliding down on a long angle, with the engine giving a spasmodic kick. Down, down towards a light fog that the breeze had brought down from the north-west; down, down till we could see below us trench lines that were not our own! Then the engine stopped!

Nap looked out, turned to me and pulled a face. Putting his mouth to the tube he shouted "Lean over and wave your hand like...."

Several grey-coated soldiers were now running over to a bare patch to which we seemed to be sliding. I waved frantically—the soldiers hesitated to fire and waved back again! Down, down, with Nap working like a fiend at the engine! Down, down to within a few hundred feet of the ground, when something happened. The engine, after a splutter, set off at its usual rattle, the propeller caught up its momentum and descent was checked.

Nap leaned over and joined in the waving demonstration and, knowing that an attempt to rise abruptly would give away the fact that we were trying to escape, he kept at a low level, flying over waving Germans, past a long line of German troops breakfasting behind the trenches; then back again to try and convince them that we were of their own, then circling around till we reached a safe height above the thickening fog, our aching arms stopped waving. We headed for home, and repaid the kindness of our German friends by having their position shelled for the rest of the day.

"That was a tight fix," Nap ventured, as I gave him a tribute from the Squadron Commander—one of the most coveted of prizes of the campaign—a cigar!

"Yes, that waving stunt was a bit of spice," he said.

"But what beats me," I replied, "is why they didn't fire on us, as we carried our distinguishing mark."

"That's easy," said Nap, sucking his cigar, "they've got some of their own 'planes carrying our mark and guessed we were one of them. But as the song says: 'We're all here, so we're alright.' Some of these days I'm going to invent an apparatus that can change signs—press a button and the Germans' black cross will cover our mark, and so on—and then we'll fly where we like."

"It's unfair to fly an enemy's flag, you know, Nap," I ventured.

"How?" he queried. "That's where the Allies, particularly you hypersensitive British, make the greatest mistake. Everything in war is fair. Get the war over, say I, even if it comes to smashing up the enemy's hospitals. The wounded, nowadays, are getting well too quickly. There's a fellow in that battery yonder who has been in the hospital twice already, and, if this war lasts out Kitchener's tip of three years, practically the whole of the armies will have gone up for alterations and repairs, and be as lively as ever on the firing line. The Geneva Treaty, that prohibits firing on the Red Cross in time of war, is like any other 'scrap of paper.' I'd wipe out the enemy's hospitals and poison his food supplies. It's an uncivilised idea, I guess, but so is war. What's the difference between tearing out a fellow's 'innards' with a bayonet, and killing him by the gentler way of poisoning his liquor? What's the difference between poisoning the enemy's drinking water and poisoning the enemy's air with the new-fangled French explosive—Turpinite? It's all hot air talking of the enemy's barbarism—scratch the veneer off any of us and we're back into the stone age. If I had a free leg or free wing, I'd drop arsenic in every reservoir in Germany. Why, we're even prevented dropping 'coughs' on those long strings of trains we see every day, crawling far beyond the enemy's line carrying supplies from their bases to the firing line, feeding 'em up, feeding 'em up all the time."

We chafed at this restriction of our possibilities.

It gave Nap a fine opportunity for nasty remarks.

"Here we've got the most wonderful arm of the war, and the men over us don't know how to appreciate it. It's the same old prejudices, as my old Colonel, Sam Reber, used to say, 'every new thing has to fight its way.' It's the same with wireless. Here they're only using it for tiddly widdly messages, like school kids practising with pickle bottles, when they could use it to guide a balloon loaded with explosives and fitted up with a wireless receiver and a charged cell, so that it could be exploded by a wave when it got over a position or a city. I'd like to see this fight a war of cute stunts, a battle of brains against brains, but I suppose we'll have to stick here till our fabrics rot whilst those fellows out yonder are burrowing into the earth like moles, coming out at night, like cave-men, and battling with a club."

What Australia was Doing.

That day I had a letter from Australia. Here it is:—

"Dear Jefson,—Your cheery letter from the front was full of the powder and shot of action and riotous optimism. I'm afraid mine will be a contrast.

"Our Australia isn't faring well. Our vigorous assertion of the strength of our young nationhood has been manifested only in a military and naval sense—commercially, we are nearly down and out.

"We are outrageously pessimistic. There was an excuse at the beginning of the war, when we dropped behind a rock, stunned at the very thought of an Armageddon; then we clapped our hands on our pockets, tightened up our purse strings, and, with white faces, waited for the worst and—we're still waiting. There was an excuse for us to be absolutely flabbergasted when the Kaiser's crowd rushed on to Paris. There may have been reason then for more than ordinary caution, but since the 'great check,' there has been no valid reason for people to still sit tight and wait. People with money to invest are holding up most of the former avenues of activity. 'Till the war is over' is the only excuse they can mumble.

"Take building investments in Sydney alone. A friend showed me a list of ninety-one plans held up, totalling over £4,000,000; held up 'till the war is over,' held up till the accumulated business will rush like an avalanche, running prices that are now low to such a high figure that the fools who waited will find they will have lost thousands. Building prices are now fifteen per cent. cheaper than before the war and twenty-five per cent. cheaper than they will be when the war has broken. Twenty-five per cent. means a distinct loss of £1,000,000 in one avenue of investment alone, not counting the tying up of the many hundreds other lines depending upon building construction—and when you consider, Jefson, that such inactivity is almost everywhere, you can guess we're in for a bad time if people don't buck up. To make matters worse, some firms are stopping advertising, forgetting that advertising is the life-blood of their business, and by stopping advertising they're stopping circulation of money. The firm that thinks it can save money by stopping advertising is in the same street as the man who thinks he can save time by stopping the clock.

"These are no ordinary firms, but what the local Labor League is so fond of describing as 'capitalistic institutions.' They hold many thousands in reserve and their annual dividends have been at least 10 per cent. for years and years and years. Moreover their businesses have not materially suffered. In some cases, indeed, there has been improvement. But 'profits' evidently supersede humanity; the interests of gold are greater than the welfare of human flesh and blood and even the call of country. It seems hard, Jefson, that you should be risking your life and other brave fellows shedding their blood, for such men who have neither commercial instinct nor human feeling. I fully expected some of those firms to start their jobs as an incentive to others. We only want someone to start and do something big to galvanise the smaller investors into action. It's not capital they lack, but confidence.

"I often wonder why the men who have had the acumen to amass money have not the common sense to realise that unemployed capital is a rapidly-accruing debt. Sovereigns by themselves are not wealth. It is their purchasing capacity and their equivalent in the requirements of life that represent fortunes. Investment, not idle capital, is wealth.

"Australia is being held back a great deal by the operation of State Enterprise. It has always been extravagant, inefficient and slow; but the effects are being more keenly felt at this time. At Cockatoo Island, the Federal Shipbuilding Yard, a cruiser was built that could not be launched. (I don't want you to mention this because we feel mighty humiliated.) Someone blundered. Who that someone was I do not suppose we shall ever know. That is the worst of being an employer of politicians. They run your business when they like, how they like, and with whom they like. You only come in on the pay day. However, the difficulty is being got over by the construction of a coffer-dam—at a cost of £30,000. We have been confidently assured by the men running our business that everything will be all right in the long run. Perhaps that assurance is intended as a guarantee that we shall get a long run for our money. Anyhow, at time of writing the coffer-dam is being constructed.

"In N.S.W. the position of the Public Works Department must be much the same as the Sultan of Turkey's—no money, no friends. And no wonder! It drained the State of all spare cash for the edification of its day-labor joss, and is about to pawn the State to foreign money lenders for more. Being now on its absolute uppers, the Public Works Department is handing over work to a private syndicate to be carried out on a percentage basis. The longer the work takes and the more it costs, the better for the private company. Here again the public pays.

"State Enterprise has wrecked the people's self-reliance and initiative. As soon as a man gets out of work now his first aim is to demand that the State make him a billet. This, of course, the State cannot do, and the rejected job-seekers, who are growing in numbers daily, are like a lot of hornets round the ears of Ministers.

"There is one way out of the difficulty, and that is, the abandonment of the whole system of State Socialism and the re-establishment of private enterprise. If that policy were to be endorsed to-morrow, plenty of capital would be found for many schemes that are held up at present, and Ministers would be relieved of all worry and responsibilities. But they're not game, they're just hanging on—hanging on, and, I tell you, something is going to snap somewhere, sometime.

"From a military point of view there is no reason to worry. We have a big army in Egypt on the road to back you up, with more to follow. I must not say much on that matter. The censor will chop it out, but we're coming to the point that every man who doesn't go to the front must learn how to shoot straight. Let's hope he'll also learn that he can do a good deal to help fellows like yourself that are keeping the flag flying abroad, by keeping up confidence and the flag flying at home."

I read the letter to Nap.

"There are two points in that letter," he said. "The funk at home and the readiness to enlist. We've also got that funk-bee, sure. Why, when I left U.S.A. a ten million dollar war tax was launched, unemployed were swarming into the cities, factories were closing down because of the falling-off of exports, and the situation was getting so desperate that the Wilson-Bryan crowd were talking of forcing the British blockade of Germany with ships of contraband stuff. But there's no readiness to enlist, Jefson, not on your life. I'm sorry to say the physically worst are offering themselves for their country's service, and only ten per cent. of those offering are accepted; and though they advertise 'bowling alleys,' 'free trips round the world,' and other stunts as inducements, the response is so flat that when I passed through Chicago last August to come here, the recruiting stations had a notice up 'colored men wanted for infantry!' You know there's a sure prejudice against the nigger, we grudge giving him a vote, but when it comes to fighting for the country, well, he's as welcome as the 'flowers that bloom in the spring, tra-la.' I guess you Australians lick us right there."

"Information had been received of a new type of Zeppelin."—Chapter VIII.

A Prisoner in Cologne.

A military operation order is crystallised commonsense. It is a wonderfully concise bunch of phraseology.

Our squadron commander read the latest by lamplight over a spread map of the theatre of war.

The general situation of the campaign explained that a Zeppelin raid on the east coast of England had been made on the 19th of January, thirteen days before.

Information had been received that a new type of Zeppelin had been constructed, a "mother" type, capable of carrying a number of aeroplanes.

The intention of the operation order was to destroy all known Zeppelin sheds; each air squadron supplying special officers for the purpose.

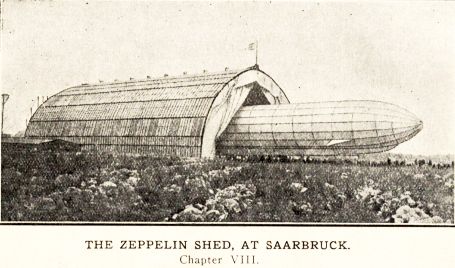

I well remember the particulars of that order. They printed their details upon my memory because I had been selected to destroy the sheds at Saarbruck. I was to leave three hours before the following dawn.

I remember Nap's disappointment that I was to go alone. He helped my machine out without a word. He may have had a premonition that I was not to return as I watched him silently fixing the compass and map-roller, testing the spring catch and guide of the bomb-dropper and packing into it its heavy load of "cough-drops." Then he stood like a dumb figure waiting for my starting signal.

"Buck up, Nap," I ventured, climbing into the seat. "One would think this was a funeral. I must get a hustle on as I've got to do 120 miles before I can get to business, so if everything's right, I'll swoop up."

Nap looked up.

"Fly high, and good luck," was all he said as he gripped my hand. Then I pressed the starter, the propeller hummed and pulled me into the star-specked sky.

I steered easterly, leaving on my left the red fire-glow of Rheims and passing over the sleepy lights of Valny. Within an hour I was over the great black stretch of the Argonne Forest, and crossing the Meuse, a long line of fog with Verdun 7000 feet below. The engine was working well, throwing back the miles at about 60 per hour. A glow of lights to the right showed Metz next to a streak of grey, the Moselle River; and as the dawn-light came into the sky, the Saar River came under me, covered by a fog with a fringe that flapped over its right bank and covered Saarbruck.

According to the sketch-map the Zeppelin sheds were near the railway station. So I flew low into the mist to get their correct position. The noise of my engine brought a shot from an aerial gun, but the fog saved me. A bunch of lights brought the station into view with the unmistakable long hangar of the Zeppelin adjacent to it.

I turned to get the sheds beneath me, and three foot-treads sent as many bombs chasing each other earthwards.

The first hit the ground near the shed, exploding without doing any damage. The second crashed through the roof of the hangar, its explosion being almost coincident with a fearful crash; the resulting air-rush almost overturning my 'plane. The third bomb fell into the back end of the shed, but I guessed it was not required.

My job was done, so I rose high above the fog line to get a straight run for home. Three Taubes were patrolling high, evidently on the look out.

I saw they would have the drop on me, so I sank back into the fog and under its cover swooped across the river for home. I was over the enemy's country where I guessed I was being searched for, so taking advantage of the fog I maintained a 1000 feet level and made a bee-line for Epernay.

THE ZEPPELIN SHED, AT SAARBRUCK.

Chapter VIII.

My job was done, and I remember I was particularly elated.

I got a surprise near the Argonne Forest, striking a breeze that suddenly came up from the south, lifting the fog curtain and showing me dangerously close to the earth.

I swiftly jerked the elevator for a swoop up as a rifle cracked. I was spotted!

A volley of shots followed and—I was winged.

I remember, like a hideous dream, a long, evil-smelling shed in which I lay, a stiffly stretched and bandaged figure on a straw-strewn floor.

I was afterwards told it was Mezieres Railway Station, and that I was one of many hundred wounded being taken from the field hospitals to the base.

I need not detail my experiences for the next six months. I was taken from the hospital at Aix-la-Chapelle to Cologne to be attached to a gang of prisoners for street cleaning.

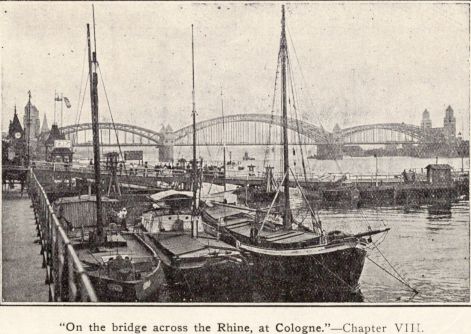

I remember our daily march across the Great Rhine Bridge with its wonderful arches at its entrance, and the great bronze horses on its flanks. I had occasion to remember that bridge, for there, some time later, the sunshine was to come into my life.

For six months I had not heard much of the war. My hospital friends had been wounded about the same time as I. My street-gang mates, a Belgian and a Frenchman, knew little except that up till June the Ostend-Nancy fighting line was still held by both armies. The lack of news did not worry me during my days of pain, but as the strength came back to me it brought a craving for news of the Great Game. Where were the Allies? What of the North Sea Fleet? How was Australia taking it? What was Nap doing? were questions that chased each other through my mind. Five Taubes had flown over us the day before, going south, but—what was doing?

It was on the Cologne Bridge a week later that a rather pretty girl, with an unmistakable English face, stopped to converse with one of my guard. At the same time she pointed to me: at which the guard looked round, frowned and spat with contempt.

"Are you English?" she queried.

"Yes," I replied, "I'm from Australia."

I had touched a sympathetic chord and she "sparked" up.

"Australia! Do you know Sydney?" she asked.

"I'm from Manly," was all I replied.

Then she did what I thought was a foolish thing—she came over and nearly shook my arm off!

The officer of the guard resented it, but she jabbered at him and explained to me that Australian prisoners were to have special treatment, then glancing at my number she stepped out across the bridge.

I found she was correct. When my gang returned to the barracks my number was called and I was questioned by the officer in charge. I was informed that Germany had no quarrel with Australia, hence I was only to be a prisoner on parole, to report myself twice a day and come and go as I pleased.

That is how I came to win great facts regarding Germany and her ideals. That is how I found out how it was that with Austria, Germany for nine months could hold at bay the mighty armies of the world's three greatest Empires, British, French and Russian, as well as the fighting cocks of Belgium; and at the same time endeavor to knock into some sort of fighting shape the crooked army of the Turks; how three nations of 109,000,000 people could defy for nine months the six greatest nations in the world with a joint population of 622,200,000!

The facts are of striking import to-day and should be understood by every man who is fighting for the Allies on and in the land, sea and air.

"On the bridge across the Rhine, at Cologne."—Chapter VIII.

Some Surprises in Cologne.

My unexpected freedom in Cologne was but one of many surprise.

There was the surprise of meeting an Australian friend in such unexpected quarters. I ascertained her name was Miss Goche. Her father was a well-known merchant of Melbourne, but was now living in Sydney. He had sent his daughter to the Leipsic Conservatorium to receive the technical polish every aspiring Australian musician seems to consider the "hall mark of excellence."

But the war closed the Conservatorium as it did most other concerns, by drawing out the younger professors to the firing line and the older men to the Landstrum, a body of spectacled elderly men in uniform, who felt the spirit wake in their feeble blood and prided themselves as "bloodthirsty dogs," as they watched railway lines, reservoirs, power stations, and did other unexciting small jobs.

Miss Goche was staying with her aunt and grandfather in Cologne. At their home I was made welcome.

Little restriction was placed on my movements, than the twice daily reporting at the Barracks.

I wondered at this freedom.

"It is easily explained," said old Goche, who could speak English. "The Fatherland knows no enmity with Australia. We have sympathy for the Indians, Canadians and other races of your Empire, who have been whipped into this war against their own free will."

"But," I interrupted, "there has been no whipping."

"Tut, tut," he continued. "We of the Fatherland know. Have we not proof? Our "Berliner Tageblatt" tells us so. We have no quarrel with the colonial people. Our hate is for England alone; and when this war is over and we have England at our feet, we shall be welcomed by Australia and the colonies, and we shall let them share with us the freedom and the light and the wisdom of our great Destiny."

There was no convincing the old man to the contrary, and his granddaughter informed me that the same opinion was universal in Germany.

"The best proof that it is so is the freedom you enjoy," she said.

"And yet there are times," she continued, "that I feel there is a subtle reason for this apparent kindliness for the colonies of the British Empire. You know Germany cannot successfully develop her own colonies. She has not that spirit of initiative that the Britisher has in attacking the various vicissitudes that every pioneer meets with in the development of a new land. That is why she let her colonies be snapped up by Australia without a pang; that is why as you say, she let her people hand over Rabaul and New Guinea to your Colonel Holmes without a battle. She fancies that when she wins this war as she has convinced herself she will, it will be a simple matter to step into the occupation of ready made colonies of such wonderful wealth and development."

The chief surprise of my freedom, however, was my changed opinion regarding the way Germany was taking the war.

I, like the average Britisher, had believed that in checking the German rush on Paris and driving it to the Aisne, we had whipped Germany to a standstill.

We had pictured her checked on the east with her Austrian ally on the verge of pleading for peace; her fleet cowering in the Kiel Canal like a frightened hen beneath a barn.

I, like every other Britisher, had fancied that Germany was undergoing an awful process of slow death; that she was faced with economic ruin; that her trade and manufacture had been smashed, causing untold ruination and forcing famine into every home; that the German populace were being crushed under the terrors of defeat, were cursing "the Kaiser and his tyrannical militarism," and waiting for the inevitable uprising with revolution and general social smash up.

And I knew such was the belief of the Allies and the world generally.

Never was a more mistaken notion spread!

Germany, notwithstanding what blunders and miscalculations she was accused of making, believed she would win.

This belief obsessed her.

Every movement, whether it achieves its direct object or not was made to nail that belief more secure.

A great philosopher wrote many years ago the following maxims:—

"To the persevering—everything is possible."

"They will conquer who believe they can."

Germany believed she would conquer, and for forty years she had been building up that belief.

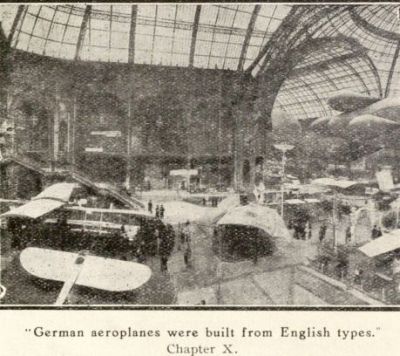

"German aeroplanes were built from English types."

Chapter X.

"Made in Germany."

Grandpa Goche told the story of Germany's development with mingled pride, yet with a tinge of regret.

We sat before his wide fireplace where a great fire crackled.

Puffing at his long pipe Grandpa Goche peered into the fire for a space before answering my query as to Germany's destiny.

"The destiny of the Deutschland?" he finally exclaimed. "Ah! It will be great and wonderful. But where it will end—who knows! Will it be like the Tower of Babel, great in conception, great in execution, but overreaching in its greatness? Will our destiny be like the snowball, accumulating as it rolls till it becomes immovable in its immensity? Then—stagnation! And yet the start of that snowball was but 50 years ago.

"I remember as a boy when Bismarck was Prime Minister of Prussia, and he forced through the Reichstag his great army re-organisation scheme. In '64 he attacked Denmark and took Schleswig-Holstein. That is how we got Kiel. Two years after he crushed the Austrians in six weeks, and took Hanover, Hesse, and Nassau; and four years after that he smashed the French and took Alsace-Lorraine.

"Flushed with victory, proud Deutschland, with Denmark, Austria and France humbled in the dust, wiped her sword and peered at the Dawn. But she did not sheath that sword. No! In the ecstasy of triumph she was trying to formulate a policy of carving a destiny great and glorious. She looked first to peaceful development by legislation; and then, in that passing period of uncertainty, Bismarck threw out his famous declaration that the destiny of Deutschland was to be won, not by votes and speeches, but by Blood and Iron.

"It was what you call a 'happy hit.'

"It appealed to the animal strength of the German race. Bismarck knew that beneath the surface most of the men of Germany were of a wild nature; he knew that in less than a century they rose from the degradation of conquered barbarians to the heights of victors of three nations, and the 'blood and iron' policy ran through Germany as a new inspiration.

"Bismarck floated the great new Ship of State, and stood at the wheel peering keenly into the troublous waters of the future. There was one great rock of which he wished to steer clear, so on the Ship of Destiny he placed a maxim. It was: 'War not with England.'

"There were other simple rules of navigation that irritated a new young officer on the bridge, who felt that the Bismarckian policy, though perhaps sure, was not speedy enough for his vaulting ambition.

"I remember well this young Kaiser, a man of wonderful vitality, who revelled in the strength of developing manhood, and who early began to assert himself. Those who tried to curb his youthful impetuosity went down before him till there was but one great personality left who could talk to him as a father would to his wayward son. It was Bismarck, he who dragged Prussia from the depths and gave her the ideal for a world power. The cool calculating wiseacre said, 'Steady, lad,' so—he had to go.

"Then the Kaiser took the wheel.

"He found Germany a comparatively small country, with a great and prolific population of sixty-six millions. He found the German woman not the mild and simple 'hausfrau' of folk lore, but a virile woman with a creed that the production of children was her first duty, not only to her husband and herself, but to her country. He knew that in Germany illegitimacy was no disgrace, and he saw Germany's population increase ten millions in the course of ten years.

"He looked at his restricted boundaries and saw his people being bottled up. That's why he gave the declaration that 'Germany's destiny is upon the water'.

"We needed colonies, but all the colonies worth having were taken by—whom? Your England!

"We were hungry for trade and influence in distant waters, but your England held the gateways to the world's trade channels.

"The road to Asia and Australia was lined with England's forts, and Gibraltar, Malta, Port Said and Aden watched the way like frowning sentinels.

"It was then that we prepared for 'The Day.'

"Our Kaiser gave the call 'Deutschland Uber Alles' (Germany over all). It was a new creed, and it soon gained the strength of a religion.

"I know you English ridicule the idea of the Kaiser and his Divine Right—but do not forget an English King claimed the same thing."

"DROPPING THE PILOT."

Tenniel's Cartoon in "Punch," showing the reckless irresponsibility of

the Kaiser began early.

"Yes," I interrupted, "and we chopped off his head."

He went on, ignoring my interruption—

"You English speak of God as the God of Hosts and the God of Battles, but you only mouth it. We Germans believe in it, and we work for it. It permeates our life like a divine call. It makes every man feel he is a part of a great whole, a working unit in an immense machine, whether it be in the field of battle or in the field of industry. We feel we are doing a divine duty.

"And this divine spirit is in our work.

"We associate all our tasks with a sense of service to our fellow citizens. We make trade and civic education compulsory to all boys from 14 to 18 years of age and to all girls from 11 to 16 years of age. Your England has only 26 per cent. of children at school between those ages.

"We train our children and people to discharge specialised functions. We associate practice with theory. We amalgamate science with manufacture.

"Your England at one time was the chief glass manufacturing country, but thirty years ago a professor of mathematics at Jena joined a glass maker, and to-day we lead in the world's glass manufacture.

"In 1910, your England exported one and a half million pounds worth of glass, and Germany exported five million pounds worth.

"In 1880, your England led the world in the output of pig iron, producing nearly eight million tons to four million tons produced by the United States.

"In 1910, the United States produced twenty-seven million tons, Germany fifteen million tons, and Great Britain ten million tons.

"In 1856 an Englishman named Perkins first produced a coal tar dye.

"In 1910, Germany exported nine and a half million pounds worth, while Great Britain exported only £336,000 worth.

"So you see Germany has beaten England in peace as you will see we shall beat her in war."

Then he spat into the fire, put his pipe away, and as he was going out to bed flung this final shot:

"And there again we differ from you English. That is why we go into this divine struggle as a grim and serious business. One great united army with a hymn to God, and one great battle cry, 'Deutschland Uber Alles.' You English take it as what you call 'a jolly sport,' with your battle cry, 'Are we down-hearted?' and your battle hymn, 'It's a long long way to Tipperary,' ah-ha-ho"—and he laughed his way up to his bedroom.

I sat looking into the dying flames, dwelling upon all his jibes.

I thought how each German felt he was a cog in the immense national machine, and had his work systematised. I could then understand how that killed initiative in the individual, and why Germany had not made any great discoveries in science or manufacture, but had simply stolen ideas of other countries and adapted them to her own ends.

Grandpa Goche had spoken of coal tar dye, then I recalled how Germany had also taken Marconi's wireless invention and Germanised it; how it had taken the French and the English ideas in airship and aeroplane construction and worked upon them; how even the English town planning movement was imitated. In the latter case I remembered reading that the "Unter den linden" had been widened by the process of pushing the dwellings back until they each housed 60 families. Germany, on this occasion, had grabbed the idea but missed the spirit, in the absence of which town planning is merely a name.

Even the manufactures of Germany had been built upon those of other countries. There was a case I recalled, that of the Australian cordial manufacturer, who desired to introduce his stuff into Germany. He was met with a stiff tariff, but informed that if he established a factory there there would be no need to import it. Why, now I came to remember it, even the original "Rush-on-Paris" plan was stolen. Hilaire Belloc, the Anglicised Frenchman, had written of it in the "London" Magazine, of May, 1912. When that plan failed what had Germany done? Why, dug itself in on the Aisne!

The idea of the German submarine raids was not original, as it formed the base of a story by Sir Conan Doyle that appeared in the English "Strand Magazine" and in the American "Colliers' Weekly" many months before!

Germany, in fact, built its fame on assiduous imitation rather than originality. But at what cost? Its people had degenerated in the process from thinking humans to dumb, driven cattle, going, going, for ever going, but non-comprehending the why or the wherefore of it all, beyond the arrogant assumption of "welt-politik." Every refining trait was subordinated to the exigencies of the gospel of force. Not only the plebeian mass, but the exclusive aristocracy, revelled in the brutish impulse that associated all appeals to reason with effeminacy and invested the sword-slash on the student's cheek with the honor ordinarily claimed by the diploma.

This gospel of exalting animal strength developed a living passion for tyranny and grossness. We have seen it evidenced in the orgies that have reddened Belgium and France.

And I had given my parole to a nation without a soul—a nation that expected honor but knew not what it meant.

I crept to bed disturbed in mind, but resolved next day to take certain action.

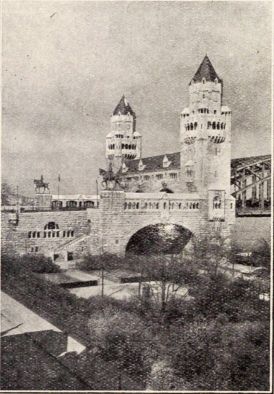

"I remembered our march across the great Rhine Bridge, with its wonderful arches and great bronze horses."—Chapter VIII.

The Escape from Cologne.

Next morn I rose from a sleepless couch.

Thoughts grim and gaunt had purged my brain the whole night long. There was a flood of reasons why I should leave that German home. I chafed at being a guest in the house of old Goche, whose animosity to the Cause was undying. I could see that our discussions on the war were increasing in bitterness and would, ere long, terminate in a storm. I desired to avoid this for the sake of Miss Goche, whose friendship was the only balm in that period of stress. I had little further desire to accept hospitality from a stranger simply because I happened to be from the same country as his granddaughter.

But greatest of all reasons why I should leave was because I had now completely recovered from my wound, and the War of the World was waging within 100 miles of me.

My job was "action on the firing line" and not lolling in security as a guest of an enemy! Now that my wound had healed and my strength had knitted firmly again, I felt I was a traitor in giving my parole not to escape.

That August morning, when I made my first daily call at the barracks, I stated to the officer to whom I generally reported, that I was going to try and escape. He first seemed somewhat surprised, but soon broke into a laugh. Turning, he spoke laughingly to another officer, who joined in the hilarity.

"So you're going to escape, eh?" he said. "Well, we don't think you will. If you intended to escape you would not be so foolish as to tell us about it; and then, if you did attempt it, you could not get out of Cologne with an English face like yours. That's alright," he repeated, "you will report this afternoon as usual."

I stood awhile.

"There is the door," he said. "Good morning, we are busy."

I returned and acquainted Miss Goche of my action.

I explained there were two reasons for my giving notice. I could now attempt to get away without breaking my parole; and now no blame could be placed on the Goche household for my escape.

I need not here mention the scene that followed, but I may state I was aware that my departure had taken on a new aspect. I knew I was leaving one for whom I had now more than friendship, one whom I found had risked much to make me secure. She admitted that, without doubt, my duty lay beyond the Rhine.

"But you will please me greatly if you will report at the barracks this afternoon, as usual," she said.

I did so, and was met by an officer with an "I told you so" smile.

I left the Goche home that afternoon at dusk. I did not intend to cross the river at Cologne. The way west would be too black with grim forebodings. The best opportunity of escaping seemed to be south, down the right bank of the Rhine to Coblenz, then crossing to the Rhine mountains, going south into Luxembourg, and then keeping east, trusting to good fortune to get through the German lines into the Vosges.

Miss Goche accompanied me as far as the park on the river bank, where in a quiet alcove I somewhat Germanised my appearance. I shaved my short beard and trimmed my moustache with the ends erect, the now universal fashion of the German menfolk; and with an old felt cap and unmistakable German clothes, I felt I could probably pass muster until I opened my mouth.

I had, thanks to my good friend, learned off a few German phrases for use at odd times, so, as night fell we parted.

Down the pathway I stepped with a world of mystery ahead of me. I remember now it took no slight effort to leave, but though the call away was unmistakable, I knew the reply was the hardest task in my experience. But I set my teeth and trudged down the track till I reached the bend, then I looked back. At the top of the road a figure stood, a hand waved and—yes—a kiss was thrown, then she turned away.

I felt alone in a new world, so marked my way and went into the night.

During the first hours I stepped along in fear and trembling. I peopled every dark corner with a sentry; I pictured every distant tree as covering watching soldiers. I wondered at the lack of challenge, till it dawned upon me that I was not in the fighting country. There was no war in these parts, so I tramped along at the side of the road till early morning, the only incident being a hail from a man on a bridge which I had passed but did not have to cross. The bridges were evidently guarded. As dawn light came into the sky I saw an aeroplane pass flying low and stared at by an early morning ploughman, then I crept behind a hedge and stole a sleep.

The Waste of War.

I could not have been long in slumber, when a slight noise, perhaps the cracking of a stick, drove sleep from my anxious brain, and I sat up with surprise, staring at a long figure in black that stood peering at me. The black gown, the beads and the broad-brimmed hat told me it was a priest.

He spoke to me in German. It was one of the sentences Miss Goche told me I would be asked—he wished to know where I was going. So I fired at him a second of my readied German phrases: "I'm going south to fight," I said, which was true.

Then he let free a flood of German that floored me. He waited for a reply that hesitated; then with a queried look into my face, he said: "English! you're no German," and his eyes began to twinkle.

"You can confess," he said, "remember there is no war with men of God. I, too, am going south, I am going to France, our journey will seem quicker in company, let us step forth."

He was a Christian Brother. He had been to Australia, where many of his Order were established. I explained I knew of their work in education; in fact, I happened to know many of the fraternity by name. I ran over a gamut of names of those I knew in past years. There were Brothers Paul, Wilbrid, Aloysius and Mark.

"I may know some of those you mention," he said, "but I do not think it possible. We seldom know each other by name unless we are beneath the same roof. There are hundreds called by the names you mentioned, I myself am a 'Brother Wilbrid.'"

It is a wonderful fact that there is nothing that knits strangers together, as the hitting on the name of a mutual friend, so we became close companions.

He had been born in Lorraine, but had lived most of his time in Berlin. His close-cropped grey hair showed he was well on in years. He had been an artisan before he joined his Order, and he lightened our long tramp to Coblenz with his idea of the trend of things.

The road was good and the air was clean and sweet. We passed by some farms where women were behind the plough.

Summer was breaking, and the Autumn sunshine was drying the last dewdrops from the grass.

"Note," Brother Wilbrid said, "how all Nature welcomes the sunshine, hear the birds twitter, see the cattle slowly moving on that rise. All Nature here joins in a hymn of peace, yet far beyond those western ridges three million men lay trenched through the winter and stared in hellish hate at each other across a narrow strip.

"All Nature welcomed the Spring with a pæan of praise, but by fighting men it was welcomed as the opportunity to rise from winter holes and rush across the Spring sun-warmed earth to warm it anew with flowing blood. But it is not the waste of blood that so appals, it's the waste of effort and the waste of heroism. The labor of three million men could, in the wasted months of war build much to ensure unending human happiness. Thirty-two thousand men cut a channel through Panama and shortened the world's journey to your home by a third! Think what the labor of three million men could do!

"And then there is the waste of heroism.

"Men with large hearts will risk their lives to drag a comrade out of danger. It is heroism—yes—but it is wasted on a cause of foolishness——"

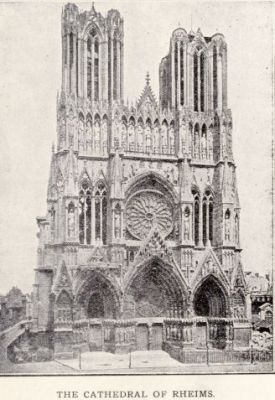

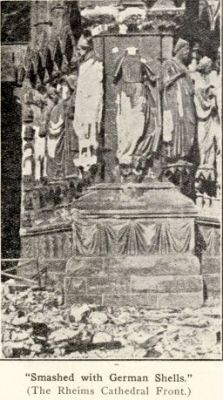

"But," I interrupted, "there is other heroism than that on the fighting line," and I told him the story of Abbe Chinot, of Rheims, the young priest in charge of the cathedral; how, when German shells were crashing into the grand old pile which was being used as a hospital for German soldiers, Chinot, aided by Red Cross nurses, dragged the wounded into the street, where surged a mob, maddened that their beloved church was in flames, and that their homes and five hundred of their folks had been smashed with German shells. The sight of the grey uniforms on the German wounded drove the mob into frenzied screams of revenge, but the fearless Abbe placed himself between the uplifted rifles of the crowd and the German wounded. "If you kill them," he said, "you must first kill us"; and how the mob, struck with his perfect courage, moved away in silence.

THE CATHEDRAL OF RHEIMS.

"Smashed with German Shells."

(The Rheims Cathedral Front.)]

"Yes, that is fine, very fine," he said—"yet it does not prove that the war made the brave Abbe heroic.

"This war is unnecessary. It is the most unnecessary of all wars. It is not a war of the people. It is a merchants' war. It is not a war of the workers. It is a war for commerce—and four million or more lives will go up to God in the interests of Trade.

"I fear the consequences of this war. I feel this war spirit will bring on a sequel that will surprise humanity.

"A great writer[1] likened the war spirit to a carbuncle on the body. The poison flowing through the blood localises itself, and a painful lump forms in the flesh. Relief is sought in salves, ointments, and poultices. But the lump continues to swell, and the pain to increase, until at the very time when the soul is in mortal agony the carbuncle bursts and spews out the poison. The pain ceases, the swelling subsides, and the flesh regains its normal color.

"The poison of injustice flows through the veins of society. Men are denied their natural rights; and when the oppression becomes unendurable, their oppressors make all manner of excuses. The affliction is due, they say, to the wrath of God, to the niggardliness of nature, or to the encroachments of foreign nations. Ah, the encroachments of foreign nations! When all other excuses fail, there is this to fall back upon; and each ruling class of oppressors holds its victims in subjection by charging the trouble to the others.

"But the people are awakening. A few already see their real oppressors. It is for each who sees the truth to tell his fellow, and that fellow his fellow, until presently all will know the truth, and the truth shall make them free; free from industrial tyranny at home, and free from military tyranny from abroad. The work of the peace advocate is not negative. It is not enough for him to cry peace, peace! He must first lay the foundation for peace. To cry peace while the people writhe under injustice is like trying to heal the carbuncle without cleansing the blood."

[1] Stoughton Cooley.

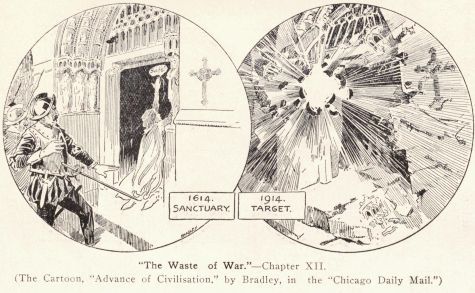

"The Waste of War."—Chapter XII.

(The Cartoon, "Advance of Civilisation," by Bradley, in the "Chicago

Daily Mail.")

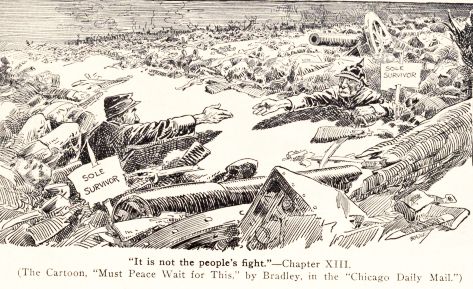

"It is not the people's fight."—Chapter XIII.

(The Cartoon, "Must Peace Wait for This," by Bradley, in the "Chicago

Daily Mail.")

How the War Wrecked Theories.

I shall never forget that wonderful walk on the Coblenz road: the grave, hard-cut featured face of the man of religion, pouring out his socialistic theories, like a long pent-up torrent bursting through years of accumulated debris. At one moment he would be calm and clear, but at times, in his excitement, he would lash at wayside flowers with his stick like a soldier with a sabre.

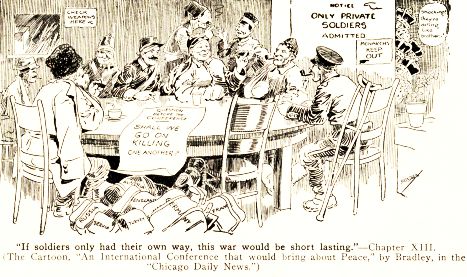

"The people are not sincere at heart in this Great War," he said, "it is not the people's fight. If soldiers only had their own way this war would be short lasting—in fact the war nearly ended on Christmas Day. You have heard how the Germans and the English ceased firing at the dawn of that holy morn. How a bayonet from a German trench held up a placard with those magic words of good cheer that ever move the world—"A Merry Christmas." How each side sang hymns at the other's invitation, crossed the zone of fire, and exchanged cigarettes. Surely the spirits of Jesus and Jaures moved along that line that wonderful morn."

"And yet," I said, "when time was up, back to their trenches the soldiers crept and fought again like devils."

He went on, ignoring my interruption.

"And German officers, high in rank, held up their hands in horror at the idea of an armistice being arranged without their consent. That is the spirit that is going to end war—that human spirit that came to the surface on Christmas morn and that proved that this awful war is but a thing of Business."

Our road passed along the cliff tops of the Rhine. There was little traffic on the river and no sign of war. Everything seemed peaceful. The war, in draining the men and youths from the countryside, had placed a mantle of calm upon life in the villages of the Rhine Valley. Even across the river a long length of railway line lay as a long road of emptiness. Not a train, not a truck, not any sign of life was upon the long stretch of metal.

"And yet," said Brother Wilbrid, "that is the main line from Bonn to Coblenz. All railwaymen, stock, and traffic are confined to the Theatres of War."

We had walked in silence for quite a while. My companion was lost in thought. I ventured an interruption.

"You are a Socialist," I said.

He looked at me a while before replying.

"A Socialist? Well, no, I'm not—that is so far as Socialists have gone. I describe myself as a 'Humanist.' Socialism as we had it before the war was synonymous with revolution. Its creed, 'Revolution before evolution,' spelt destruction and anarchy. It aimed to get what it wanted by force instead of striving to get it by constitutional means. I broke with them just there—and yet—and yet," he mused, as if to himself, "they were hounded down as outlaws of society for promising force—for threatening to do what the armies are to-day doing in the 'interests of civilisation.'

"What a shuffle of theories this mighty conflict has brought about! Strange that your Allies claim they are fighting to save civilisation from being destroyed by the 'German barbarians,' whilst the German convinces himself that he is fighting to impress his 'higher culture' upon an unenlightened world!

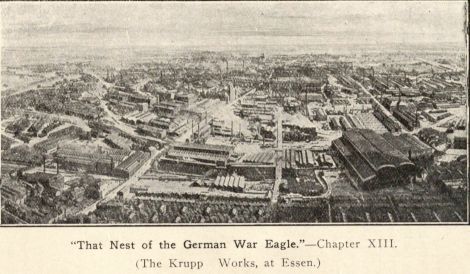

"Listen! I was once an engineer in the Krupp Works, at Essen; that nest of the German War Eagle. I was but a unit in a mighty mass. We were all well treated. Our health was well served. Our masters had learned that, just as they watched the health of horses, it was just as necessary to study the well-being of their human workers; so model homes and villages were built for us, our masters realising that if we were healthy they would get more work from us. They were philanthropists with an eye on the output. And the average German worker was getting contented—getting into a groove."

"That Nest of the German War Eagle."-Chapter XIII.

(The Krupp Works, at Essen.)

"Then," I ventured, "if a man's contented and has nothing to growl about—why worry?"

"Ah," he replied, "that's just the trouble, the German worker, as a worker, has little to complain of, but he is becoming systematised. He cannot rise, he is forced to be content and do his job. His health is insured by groups of employers sharing the responsibility. If workers get hurt too much or sick too much, the insurance syndicate begins to lose money; hence safety devices are considered and sanitoria built to prevent illness; and this German social insurance speeds individual initiative to top speed. It makes the German worker a splendid animal—and there is the danger.

"You know it's human nature to complain—progress is built upon discomfort, contentment means stagnation. I could see the workers fixed in their contented groove under the studied philanthropy of his employers and ending as in the dumb-driven-cattle age of the Feudal Barons."