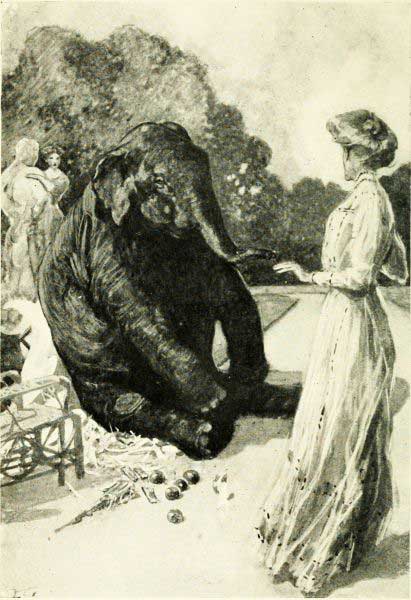

"He sat down hurriedly on the breakfast table"

"He sat down hurriedly on the breakfast table"

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Her Ladyship's Elephant, by David Dwight Wells This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net Title: Her Ladyship's Elephant Author: David Dwight Wells Release Date: February 21, 2009 [EBook #28149] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK HER LADYSHIP'S ELEPHANT *** Produced by Annie McGuire, from scans obtained from Google Print project.

"He sat down hurriedly on the breakfast table"

"He sat down hurriedly on the breakfast table"

By Hall Caine

The Bondman

The Scapegoat

By R. L. Stevenson

The Ebb-Tide

(With LLOYD OSBOURNE)

By Jack London

The Call of the Wild

By H. G. Wells

The War of the Worlds

By Robert S. Hichens

Flames

By R. Harding Davis

Soldiers of Fortune

By E. L. Voynich

The Gadfly

By Maxwell Gray

The Last Sentence

By D. D. Wells

Her Ladyship's Elephant

CHAPTER I

CHAPTER II

CHAPTER III

CHAPTER IV

CHAPTER V

CHAPTER VI

CHAPTER VII

CHAPTER VIII

CHAPTER IX

CHAPTER X

CHAPTER XI

A well-known English novelist once told me that of all his published works—and their name is legion—one only had been founded on fact, and that one his critics united in condemning as impossible and unnatural. In the case of my own little book, I venture to forestall such criticism by stating that while the characters which appear in its pages are at the most only composite photographs, the one "impossible" and "unnatural" figure, the elephant, had his foundation in actual fact; and the history of its acquirement by the Consul, as hereinafter set forth, is the truthful narration of an actual experience, one of many episodes, stranger than fiction, which went to form the warp and woof of my diplomatic experience.

DAVID DWIGHT WELLS.

Harold Stanley Malcolm St. Hubart Scarsdale, Esq., of "The Towers," Sussex, sat uncomfortably on a very comfortable chair. His patent-leather boots were manifestly new, his trousers fresh from the presser, his waistcoat immaculate, while his frock coat with its white gardenia, and his delicate grey suede gloves, completed an admirable toilet. He was, in short, got up for the occasion, a thoroughly healthy, muscular, well-groomed animal; good-natured too, fond in his big-hearted boyish way of most other animals, and enough of a sportsman to find no pleasure in winging tame or driven grouse and pheasants. He was possessed, moreover, of sufficient brains to pass with credit an examination which gave him a post in the War Office, and had recently become, owing to the interposition of Providence and a restive mare, the eldest son.

In spite of all this, he was very much out of his depth as he sat there; for he was face to face with a crisis in his life, and that crisis was embodied in a woman. And such a woman!—quite unlike anything his conservative British brain had ever seen or imagined before the present London season: a mixture of Parisian daintiness and coquetry, nicely tempered by Anglo-Saxon breeding and common sense—in a word, an American.

He had come to propose to her, or rather she had sent for him, to what end he hardly knew. Of this only was he certain, that she had turned his world topsy-turvy; cast down his conventional gods; admired him for what he considered his fallings-off from the established order of things; laughed at his great coups; cared not a whit for his most valued possessions; and become, in short, the most incomprehensible, bewitching, lovable woman on earth.

He had talked to her about the weather, the opera, the Court Ball, and now—now he must speak to her of his love, unless, blessed reprieve! she spoke first—which she did.

"Now, Mr. Scarsdale," she remarked, "I have not sent for you to talk amiable society nonsense: I want an explanation."

"Yes, Miss Vernon," he replied, nerving himself for the ordeal.

"Why did you propose to Aunt Eliza at the Andersons' crush last night?"

"Because——" he faltered. "Well, really, you see she is your only relative in England—your chaperon—and it is customary here to address offers of marriage to the head of the family."

"I really don't see why you want to marry her," continued his tormentor. "She is over sixty. Oh, you needn't be shocked; Aunt Eliza is not sensitive about her age, and it is well to look these things fairly in the face. You can't honestly call her handsome, though she is a dear good old soul, but, I fear, too inured to Chicago to assimilate readily with English society. Of course her private means are enormous——"

"Good heavens! Miss Vernon," he exclaimed, "there has been some dreadful mistake! I entertain the highest respect for your aunt, Miss Cogbill, but I don't wish to marry her; I wish to marry—somebody else——"

"Really! Why don't you propose to Miss Somebody Else in person, then?"

"It is usual——" he began, but she cut him short, exclaiming:

"Oh, bother! Excuse me, I didn't mean to be rude, but really, you know, any girl who was old enough to marry would be quite capable of giving you your—answer." The last word, after a pause for consideration, was accompanied by a bewitching, if ambiguous, smile.

"I—I hope you are not offended," he floundered on, in desperate straits by this time.

"Oh dear, no," she returned serenely, "I'm only grieved for Aunt Eliza. You shouldn't have done it, really; it must have upset her dreadfully; she's too old for that sort of thing. Do tell me what she said to you."

"She said I must propose on my own account," he blurted out, "and that she could not pretend to advise me."

"Clever Aunt Eliza!" murmured Miss Vernon.

"So you see," continued her lover, determined to have it over and know the worst, "I came to you."

"For more advice?" she queried, and, receiving no answer, continued demurely: "Of course I haven't the remotest idea whom you mean to honour, but it does seem to me that the wives of Englishmen allow themselves to be treated shamefully, and I once made out a list of objections which I always said I would present to any Englishman who proposed to me. Of course," she hastened to add, "you will probably marry an English girl, who won't mind."

"I haven't said so!" he interjected.

"No," she said meditatively, "you haven't. I'll tell you what they are if you wish."

"Do," he begged.

"Well, in the first place," she continued, "I should refuse to be a 'chattel.'"

"Oh I say——" he began. But she went on, unheeding his expostulation:

"Then my husband couldn't beat me, not even once, though the law allows it."

"What do you take us for?" he exclaimed.

"Then," she proceeded, "he would have to love me better than his horses and his dogs."

"Oh I say! Mabel," he burst out, teased beyond all limits of endurance, "don't chaff me; I'm awfully in earnest, you know, and if you will accept what little I have to offer—three thousand a year, and 'The Towers,' now poor Bob's gone——" He paused, but she made no answer, only he noticed that all of a sudden she had become very serious.

"Lady Mary, my mother, you know, would of course leave the place to you at once, but there's no title; my father was only a knight. I'm sorry——"

"Oh," she replied, "I wouldn't have married you if you had had one; quite enough of my countrywomen have made fools of themselves on that account."

"Then you will marry me!" he cried, and sprang towards her.

She saw her slip and tried to correct it.

"I haven't said——" she began, but the sentence was never finished; for Harold Stanley Malcolm St. Hubart Scarsdale, of "The Towers," Sussex, closed the argument and the lips of Miss Mabel Vernon, of Chicago, Illinois, U.S.A., at one and the same time.

Robert Allingford, United States Consul at Christchurch, England, and Marion, youngest daughter of Sir Peter and Lady Steele, were seated on the balcony of the Hyde Park Club one hot afternoon. Everybody had gone down to the races at Goodwood, and the season was drawing its last gasp. The "Row," which they overlooked, was almost deserted, save for an occasional depressed brougham, while the stretches of the Park beyond were given over to nursemaids and their attendant "Tommies" and "Bobbies."

Mamma was there, of course. One must be conventional in London, even in July; but she was talking to the other man, Jack Carrington, who had been invited especially for that purpose, and was doing his duty nobly.

The afternoon tea had been cleared away, and the balcony was deserted. In another week Marion would go into the country, and he would return to his consulate. He might never have such another chance. Opportunities for a proposal are so rare in London that it does not do to miss them. A ball affords almost the only opening, and when one remembers the offers to which one has been a third party, on the other side of a thin paper screen—well, it makes a man cautious.

Robert Allingford had planned and worked up this tea with patience and success. Jack was to be best man, in consideration of his devotion to mamma—provided, of course, that the services of a best man should be required. On this point Allingford was doubtful. He was sure that Lady Steele understood; he knew that Sir Peter had smiled on him indulgently for the past fortnight; his friends chaffed him about it openly at dinners and at the club; but Marion—he was very far from certain if she comprehended the state of affairs in the slightest degree.

He had given her river-parties, box-parties, dinners, flowers, candy—in short, paid her every possible attention; but then she expected Americans to do so; it was "just their way," and "didn't mean anything."

He greatly feared that his proposal would be a shock to her, and English girls, he had been told, did not like shocks. He wondered if it would have been better to ask Lady Steele for her daughter's hand, but this he felt was beyond him. Proposing was bad enough anyway, but to attempt a declaration in cold blood—he simply couldn't. Moreover he felt that it must be now or never. Jack had been giving him the field for five minutes already, and he had not even made a beginning. He would go in and get it over.

"You are leaving town next week," he said. "I shall miss you."

"You have been very good to me," she replied simply.

"Good to myself, you mean. It is the greatest pleasure I have in life to give you pleasure, Marion."

"Mr. Allingford!" she said, half rising. He had used her Christian name for the first time.

"Forgive me if I call you Marion," he went on, noting with relief that her ladyship was talking charity bazaar to Jack, and so assuring him from interruption.

"I mean, give me the right to do so. You see I'm awfully in love with you; I can't help loving the sweetest girl I know. You must have seen how I cared."

"Lately, yes—I have suspected it," she answered in a low voice.

"Do you mind? I can't help it if you do. I'll love you anyway, but I want you to be my wife, to care for me just a little; I don't ask more."

"I think you must speak to mamma."

"But I don't wish—I mean, can't you give me something to go on—some assurance?"

She blushed and looked down, repeating the phrase, "I think you must speak to mamma."

"Is that equivalent——" he began; then he saw that it was, and added, "My darling!"

Her head sank lower, he had her hand in a moment, and wondered if he might venture to kiss her, screened as they both were by her sunshade, but hesitated to do so because of the ominous silence at the other end of the balcony.

"If you have nothing better to do this evening," said Lady Steele's voice to him, "come to us. Sir Peter and I are dining at home, and if you will partake of a family dinner with us we shall be delighted."

He bowed his acceptance.

"Come, Marion," her ladyship continued. "We have spent a charming afternoon, Mr. Allingford, thanks to your hospitality. We are at home on Thursdays after September; Mr. Carrington, you must come and hear more about my bazaar." And they were gone.

Jack stepped to the bell. "Well, Bob," he said to Allingford, "is it brandy and soda or champagne?"

"Champagne," replied that gentleman.

"Then," remarked Carrington, after ordering a bottle of '80 "Perrier"—"then, Bob, my boy, let me congratulate you."

"I think I deserve it," he replied, as he wrung his friend's hand; "for I believe I have won for my wife the most charming girl in London."

"I am awfully glad for you," said Carrington, "and I consider her a very lucky young woman."

"I don't know about that," returned Allingford, "and I'm sure I don't see what she can find to care for in me. Why, we hardly know each other. I've only met her in public, and not over a couple of dozen times at that."

"Oh, you will find it much more fun becoming acquainted after you are engaged. Our English conventions are beautifully Chinese in some respects."

Allingford laughed, saying: "I don't know that I'm going to be engaged. I can't imagine why her family should approve of the match; I haven't a title and never can have, and I'm only in consular service. Now if I had been a diplomat——"

"My dear fellow," said Carrington, "you seem to forget that you have a few dozen copper-mines at your disposal, and a larger income than you can conveniently spend. Her people haven't forgotten it, however, as I'll venture to prophesy that you'll find out before to-morrow morning. As for your being an American and a Consul, that doesn't count. Just make the settlements sufficiently large, and as long as you don't eat with your knife or drink out of your finger-bowl they will pardon the rest as amiable eccentricities."

"You are a cynic, Carrington, and I don't believe it," said Allingford, rising to go. "Anyway, what do you know about marriage?"

"Nothing, and I am not likely to," rejoined his friend, "but I've lived in London."

The dinner that night at Belgrave Square did not serve to put the Consul at his ease. True, he sat by Marion, but no word was spoken of what had passed that afternoon, and he could not help feeling that he was in an anomalous position. He had on his company manners, and was not at his best in consequence. He felt he was being watched and would be criticised in the drawing-room after dinner, which made him nervous. Sir Peter had several married daughters, one of whom was present, and Allingford wondered how their husbands had behaved under similar circumstances. He gave Lady Steele, at whose right he sat, ample opportunity to question him concerning his family history and future plans and prospects—a chance of which she was not slow to avail herself.

When the ladies had departed and had left the two gentlemen to their coffee and cigars, Sir Peter lost no time in opening the question, and said, somewhat bluntly:

"So I hear that you wish to marry my daughter."

The Consul signified that such was the case.

"I'm sure I don't know why," resumed her father, with true British candour. "I become so used to my children that I sometimes wonder what other people can see in them. Marion is a good little girl, however, I'll say that for her—a good little girl and not extravagant."

Sir Peter's manner was reassuring, and Allingford hastened to say that he was sensible of the great honour Miss Steele had done him in considering his suit, and that he should strive to prove himself worthy of her.

"I don't doubt it, my dear fellow, I don't doubt it." And the baronet paused, smiling so amiably that the Consul was disconcerted, and began to fear an unpleasant surprise.

"I trust," he returned, "that you are not averse to me as a son-in-law?"

"Personally much the reverse; but I always ask the man who comes to me as you have done one question, and on his answer I base my approval or disapproval of his suit."

"And that question is?"

"Can you support a wife, Mr. Allingford?"

"As a gentleman I could not have asked her hand if such were not the case."

"Ah," replied Sir Peter, "that is quite right."

"As for my position——" continued the young man.

"You hold a public office in the service of your country. I consider that sufficient guarantee of your position, both moral and social."

Allingford, who knew something of American practical politics, thought this by no means followed, but forbore to say so, and Sir Peter continued:

"Have you any family?"

"No relations in the world except my younger brother, Dick, who manages the property at home, while I play at politics abroad."

"I see," said his host. "One question more and I have done. I dislike talking business after dinner—it should be left to the lawyers; but, seeing that you are an American and do not understand such things, I thought——"

The Consul stopped him by a gesture. "You are referring to the settlements, Sir Peter," he said. "Set your mind at rest on that score. I'll do the proper thing."

"Of course, my dear fellow, of course; I don't doubt that for a moment. But—er—you won't think me mercenary if I ask you to be—in short—more definite. I speak most disinterestedly, purely out of consideration for my daughter's future."

Allingford frowned slightly as Carrington's prophecy came back to him. His prospective father-in-law was quite within his rights in speaking as he did, but why couldn't he have left it at least till to-morrow?

"Would a copper-mine do?" he said, looking up. "I'd give her a copper-mine."

"Really, I don't know what to say," replied Sir Peter, in some perplexity. "I'm quite ignorant of such matters. Are—er—copper-mines valuable?"

"The one I'm thinking of has been worth a quarter of a million since it started, and we have only begun to work it," replied the Consul.

"Bless my soul!" ejaculated his host. "You don't say so! Do you go in much for that sort of thing?"

"Yes, I've quite a number."

"Dear me!" said Sir Peter dreamily, "a quarter of a million." Then waking up he added: "But I'm forgetting the time. My dear Allingford—er—your Christian name escapes me."

"Robert, Sir Peter."

"Thanks. I was going to say, my dear Robert, that you must go upstairs and see mamma."

When Robert Allingford entered the smoking-room of his club, one afternoon early in October, he was genuinely glad to find that it had but one occupant, and that he was Harold Scarsdale. The two men had met each other for the first time at a house-party some eighteen months before, and their acquaintance had ripened into true friendship.

"Hello!" he cried, accosting that gentleman. "You're enjoying to the full your last hours of bachelor bliss, I see."

"Speak for yourself," replied Scarsdale, who looked extremely bored. "You're also on the dizzy brink."

"It's a fact," admitted the Consul; "we are both to be married to-morrow. But that is all the more reason why we should make the most of our remaining freedom. You look as glum as if you'd lost your last friend. Come, cheer up, and have something to drink."

"They say," remarked the Englishman as he acquiesced in the Consul's suggestion, "that a man only needs to be married to find out of how little importance he really is; but I've been anticipating my fate. Miss Vernon's rooms are a wilderness of the vanities of life, and here I am, banished to the club as a stern reality."

"Quite so," replied the American. "I'm in the same box. The dressmakers have driven me clean out of Belgrave Square. But you, you really have my sympathy, for you are to marry one of my countrywomen, and they are apt to prove rather exacting mistresses at times like these."

"Oh, I'm fairly well treated," said Scarsdale; "much better than I deserve, I dare say. How is it with you?"

"Oh," laughed Allingford, "I feel as if I were playing a game of blind man's buff with English conventionalities: at least I seem to run foul of them most of the time. I used to imagine that getting married was a comparatively simple matter; but what with a highly complicated ceremony and an irresponsible best man, my cup of misery is well-nigh overflowing."

"I suppose you have been doing your required fifteen days of residence in the parish? London is slow work, now every one is out of town," remarked Scarsdale.

"My second-best hand-bag has been residing for the past fortnight in an adjacent attic, in fulfilment of the law," returned the American; "but affairs at the consulate have kept me on post more than I could have wished."

"I should not think you would have much business at this season of the year."

"On the contrary, it is just the time when the migratory American, who has spent the summer in doing Europe, returns to England dead broke, and expects, nay, demands, to be helped home."

"Do you have many cases of that sort?"

"Lots. In fact, one especially importunate fellow nearly caused me to lose my train for London yesterday. I gave him what he asked to get rid of him."

"I suppose that sort of thing is a good deal like throwing money into the sea," said Scarsdale. "It never comes back."

"Not often, I regret to say; but in this case my distressed countryman put up collateral."

"Indeed. I trust you can realise on it if need be."

"I don't think I want to," said the Consul, "seeing it's an elephant."

"What!" cried Scarsdale.

"An elephant, or rather, to be exact, an order for one to be delivered by the Nubian and Red Sea Line of freighters in two or three days at Southampton Docks. My friend promises to redeem it before arrival, expects advices from the States, &c., but meanwhile is terribly hard up."

"I hope he will be true to his promises, otherwise I wish you joy of your elephant. You might give it to Lady Steele," suggested Scarsdale.

"Yes. I think I can see it tethered to the railings in Belgrave Square," remarked the Consul; "but I am not losing sleep on that account, for, though I've informed the steamship people that I am, temporarily, the owner of the beast, I more than suspect that the order and the elephant are both myths. But I have been telling you of my affairs long enough; how go yours?"

"Swimmingly," replied the Englishman. "Miss Vernon has only one relative in England, thank Heaven! but my family have settled down on me in swarms."

"Is Lady Diana Melton in town for the occasion?" asked Allingford.

Scarsdale flushed, and for the moment did not reply.

"I beg your pardon," said the American, "if I have asked an unfortunate question."

"Not at all," replied his friend. "My great-aunt, who, as you know, is a somewhat determined old person, has the bad taste to dislike Americans. So she has confined herself to a frigid refusal of our wedding invitation, and sent an impossible spoon to the bride."

"So you are not to have her country place for your honeymoon," said Allingford. "From what I have heard of Melton Court, it would be quite an ideal spot under the circumstances."

"No, we are not going there. The fact is, I don't know where we are going," added Scarsdale.

"Really!"

"Yes. As you were saying just now, your countrywomen are apt to prove exacting, and the future Mrs. Scarsdale has taken it into her head that I am much too prosaic to plan a wedding trip—that I would do the usual round, in fact, and that she would be bored in consequence; so she has taken the arrangements upon herself, and the whole thing is to be a surprise for me. I don't even know the station from which we start."

"I'm afraid I can't commiserate you," returned Allingford, laughing, "for I'm guilty of doing the very same thing myself, and my bride elect has no idea of our destination. She spends most of her spare time in trying to guess it."

At this moment a card was handed to Allingford, who said: "Why, here is my best man, Jack Carrington. You know him, don't you? I wonder what can have started him on my trail," and he requested the page to show him up.

A moment later Carrington entered the room. He was one of the best-dressed, most perfect-mannered young men in London, the friend of every one who knew him, a thoroughly delightful and irresponsible creature. To-day, however, there was a seriousness about his face that proclaimed his mission to be of no very pleasant character.

After greeting his friends, he asked for a few words in private with his principal, and as a result of this colloquy Allingford excused himself to Scardsdale, saying that he must return to his lodgings at once, as Carrington had brought him news that his brother Dick had arrived unexpectedly from America, and was awaiting him there.

"What a delightful surprise for you!" exclaimed Scarsdale.

"Yes, very—of course," returned Allingford drily; and after a mutual interchange of congratulations on the events of the morrow, and regrets that neither could be at the wedding of the other, the Consul and his best man left the club.

"He did not seem over-enthusiastic at Carrington's news," mused Scarsdale, and then his mind turned to his own affairs.

It was not astonishing that Robert Allingford received the news of his brother's arrival without any show of rejoicing. A family skeleton is never an enjoyable possession, but when it is not even decently interred, but very much alive, and in the shape of a brother who has attained notoriety as a black sheep of an unusually intense dye, it may be looked upon as little less than a curse.

Yet there were redeeming qualities about Dick Allingford. In spite of his thoroughly bad name, he was one of the most kind-hearted and engaging of men, while the way in which he had managed his own and his brother's property left nothing to be desired. Moreover, he was quite in his element among his miners. Indeed his qualities, good and bad, were of a kind that endeared him to them. He loved the good things of this life, however, in a wholly uncontrollable manner, and, as his income afforded almost unlimited scope for these desires, his achievements would have put most yellow-covered novels to the blush. Dick's redeeming virtue was a blind devotion to his elder brother, from whom he demanded unlimited advice and assistance in extricating him from a thousand-and-one scrapes, and inexhaustible patience and forgiveness for those peccadilloes. When Robert had taken a public office in England it was on the distinct understanding that Richard should confine his attentions to America, and so far he had not violated the contract. The Consul had taken care that his brother should not be informed of the day of his marriage until it was too late for him to attend in person, for he shuddered to think of the rig that Richard would run in staid and conventional English society. Accordingly he hastened to his lodgings, full of anxious fore-bodings. On arrival his worst fears were fulfilled. Dick received him with open arms, very affectionate, very penitent, and very drunk. From that gentleman's somewhat disconnected description the Consul obtained a lurid inkling of what seemed to have been a triumphal progress of unrestrained dissipation from Southampton to London, of which indignant barmaids and a wrecked four-in-hand formed the most redeeming features.

"Now explain yourself!" cried Robert in wrath, at the conclusion of his brother's recital. "What do you mean by this disgraceful conduct, and why are you in England at all?"

"Saw 'proaching marriage—newspaper," hiccoughed Dick—"took first steamer."

"What did you come for?" demanded Allingford sternly.

"Come? Congratulate you—see the bride."

"Not on your life!" exclaimed the Consul. "You are beastly drunk and not fit for decent society."

"Fault—railroad company—bad whisky," explained the unregenerate one.

"I'll take your word for it," replied his brother. "You ought to be a judge of whisky. But you won't go to my wedding unless you are sober." And he rang for his valet.

"This is my brother, Parsons," he remarked to that individual when he entered. "You may put him to bed at once. Use my room for the purpose, and engage another for me for to-night."

"Yes, sir," replied his valet, who was too well trained to betray any emotion.

"When you have got him settled," continued the Consul, "lock him in, and let him stay till morning." With which he straightway departed, leaving his stupefied brother to the tender mercies of the shocked and sedate Parsons.

Allingford stood a good deal in awe of his valet, and dreaded to see the reproachful look of outraged dignity which he knew would greet him on his return. So he again sought the club, intending to find Scarsdale and continue their conversation; but that gentleman had departed, and the Consul was forced to console himself with a brandy and soda, and settle down to a quiet hour of reflection.

He had been engaged upwards of three months, and, it is needless to say, had learned much in that space of time. An engagement is a liberal education to any man, for it presents a series of entirely new problems to be solved. He ceases to think of and for himself alone, and the accuracy with which he can adjust himself to these novel conditions determines the success or failure of his married life. Robert Allingford, however, was engaged to a woman of another nation; of his own race, indeed, and speaking his own tongue, but educated under widely differing standards and ideals, and on a plane of comparative simplicity when viewed in the light of her complex American sister. The little English girl was an endless mystery to him, and it was only in later life that he discovered that he was constantly endowing her with a complicated nature which she did not possess. He could not understand a woman who generally—I do not say invariably, for Marion Steele was human after all, but who generally meant what she said, whose pleasures were healthy and direct, and who was really simple and genuinely ignorant of most things pertaining to the world worldly. He knew that world well enough—ten years of mining had taught him that—and he had been left to its tender mercies when still a boy, with no relatives except his younger brother, who, as may well be imagined, was rather a burden than a help.

But if Robert Allingford had seen the rough side of life, it had taught him to understand human nature, and, as he had been blessed with a large heart and a considerable measure of adaptability, he managed to get on very well on both sides of the Atlantic. True, he seldom appreciated what the British mind held to contain worth; but he was tolerant, and his tolerance begat, unconsciously, sympathy. On the other hand, the Consul was as much of a mystery to his fiancée as she had ever been to him. In her eyes he was always doing the unexpected. For one thing, she never knew when to take him seriously, and was afraid of what he might do or say; but she soon learned to trust him implicitly, and to estimate him at his true sterling worth.

In short, both had partially adjusted themselves to each other, and were likely to live very happily, with enough of the unknown in their characters to keep them from becoming bored. Allingford had never spoken definitely to his fiancée concerning his younger brother, and she knew instinctively that it was a subject to be avoided. To her father she had said something, but Sir Peter had little interest in his children's affairs beyond seeing that they were suitably married; and since he was satisfied with the settlements and the man, was content to leave well enough alone.

The Consul, therefore, thought himself justified in saying nothing about the unexpected arrival of his brother, especially as the chances of that gentleman's being in a fit state to appear at the wedding seemed highly problematical.

Next morning there were no signs of repentance or of Dick; for if a deserted bed, an open window, and the smashed glass of a neighbouring skylight signified anything, it was that Mr. Richard Allingford was still unregenerate and at large.

The bridal day dawned bright and clear, and Carrington lunched with the Consul just before the ceremony, which, thanks to English law, took place at that most impossible hour of the day, 2.30 p.m.

The bridegroom floundered through the intricacies of the service, signed his name in the vestry, and achieved his carriage in a kind of dream; but woke up sufficiently to the realities of life at the reception, to endure with fortitude the indiscriminate kissing of scores of new relations. Then he drank his own health and the healths of other people, and at last escaped upstairs to prepare for the journey and have a quiet fifteen minutes with his best man.

"Now remember," he said to that irresponsible individual, "you are the only one who knows our destination this evening, and if you breathe it to a soul I'll come back and murder you."

"My dear fellow," replied Carrington, "you don't suppose, after I've endured weeks of cross-questioning and inquisitorial advances from the bride and her family, that I am going to strike my colours and give the whole thing away at the eleventh hour."

"You have been a trump, Jack," rejoined the Consul, "and I only wish you may be as happy some time as I am to-day."

"It is your day; don't worry about my affairs," returned Carrington, with a forced laugh which gave colour to the popular report that the only vulnerable point in his armour of good nature lay in his impecunious condition and the consequent impossibility of his marrying on his own account.

It was only a passing cloud, however, and he hastened to change the subject, saying: "Come, you are late already, and a bride must not be kept waiting."

Allingford was thereupon hustled downstairs, and wept upon from all quarters, and his life was threatened with rice and old shoes; but he reached the street somehow with Mrs. Robert in tow, and, barring the circumstance that in his agitation he had embraced the butler instead of Sir Peter, he acquitted himself very well under the trying ordeal.

As they drove to the station his wife was strangely quiet, and he rallied her on the fact.

"Why," he said, "you haven't spoken since we started."

Her face grew troubled. "I was wondering——" she began.

"If you would be happy?" he asked. "I'll do my best."

"No, no, I'm sure of that, only—do tell me where we are going."

The Consul laughed. "You women are just the same all the world over," he replied, but otherwise did not commit himself; but his wife noticed that he looked worried and anxious, and that he breathed a sigh of unmistakable relief as their train drew out of Waterloo Station. She did not know that the one cloud which he had feared might darken his wedding day had now been dispelled: he had seen nothing of his brother.

It might be supposed that the heir to "The Towers" and Lady Scarsdale's very considerable property would meet with some decided opposition from his family to his proposed alliance with Mabel Vernon, an unknown American, who, though fairly provided with this world's goods, could in no sense be termed a great heiress. But the fact of the matter was that the prejudices of his own people were as nothing when compared with those of Aunt Eliza. In the first place she did not wish her niece to marry at all, on the ground that no man was good enough for her; and in the second place she had decided that if Mabel must have a partner in life, he was to be born under the Stars and Stripes. Her wrath, therefore, was great when she heard of the engagement, and she declared that she had a good mind to cut the young couple off with a cent, a threat that meant something from a woman who had bought corner lots in Chicago immediately after the great fire, and still held them. Scarsdale never forgot his first interview with her after she had learned the news.

"I mistrusted you were round for no good," she said, "though I wasn't quite certain which one of us you wanted."

He bit his lip.

"There's nothing to laugh at, young man," she continued severely; "marrying me would have been no joke."

"I'm sure, Miss Cogbill——" began Scarsdale.

"You call me Aunt Eliza in the future," she broke in; "that is who I am, and if I choose to remember your wife when I'm gone she'll be as rich as a duchess, as I dare say you know."

"I had no thought of your leaving her anything, and I am quite able to support her without your assistance," he replied, nettled by her implication.

"I am glad to hear it; it sounds encouraging," returned the aunt. "Tell me, have you ever done anything to support yourself?"

"Rather! As a younger son, I should have had a very poor chance if I'd not."

"How many towers have you got?" was her next question.

"I don't know," said Scarsdale, laughing at her very literal interpretation of the name of his estate.

"Have they fire-escapes?"

"I'm afraid not," he replied, "but you must come and see for yourself. My mother will be happy to welcome you."

"No, I guess not; I'm too old to start climbing."

"Oh, you wouldn't have to live in them," he hastened to assure her; "there are other parts to the house, and my mother——"

"That's her ladyship?"

"Yes."

"You are sure you haven't any title?" asked Aunt Eliza suspiciously.

"No, nor any chance of having one."

"Well, I do feel relieved," she commented. "The Psalms say not to put your trust in princes, but I guess if King David had ever been through a London season he wouldn't have drawn the line there; and what's good enough for him is good enough for me."

"I think you can trust me, Aunt Eliza."

"I hope so, though I never expected to see a niece of mine married to a man of war."

"Not a man of war," he corrected, "only a man in the War Office—a very different thing, I assure you."

"I am rejoiced to hear it," she replied. "Now run along to Mabel, and I'll write your mother and tell her that I guess you'll do." Which she straightway did, and that letter is still preserved as one of the literary curiosities of "The Towers," Sussex.

The first meeting of Aunt Eliza and Lady Scarsdale took place the day before the wedding. It was pleasant, short, and to the point, and at its conclusion each parted from the other with mingled feelings of wonder and respect. Indeed, no one could fail to respect Miss Cogbill. Alone and unaided she had amassed and managed a great fortune. She was shrewd and keen beyond the nature of women, and seldom minced matters in her speech; but nevertheless she was possessed of much native refinement and prim, old-time courtesy that did not always seem in accordance with the business side of her nature.

As time went on she became reconciled to Scarsdale, but his lack of appreciation of business was a thorn in her flesh, and, indeed, her inclinations had led her in quite another direction.

"Now look at that young Carrington who comes to see you once in a while; if you had to marry an Englishman, why didn't you take him?" she said once to her niece.

"Why, Aunt Eliza," replied that young lady, "what are you thinking of? According to your own standards, he is much less desirable than Harold, for he has not a cent."

"He'd make money fast enough if his training didn't get in his way," she retorted, "which is more than can be said of your future husband."

The wedding was very quiet, at Miss Vernon's suggestion and with her aunt's approval, for neither of them cared for that lavish display with which a certain class of Americans are, unfortunately, associated. There was to be a reception at the hotel, to which a large number of people had been asked; but at the ceremony scarcely a dozen were present. Scarsdale's mother and immediate family, a brother official, who served as best man, and Aunt Eliza made up the party.

At the bride's request, the service had been as much abbreviated as the Church would allow, and the whole matter was finished in a surprisingly short space of time. The reception followed, and an hour later the happy pair were ready to leave; but their destination was still a mystery to the groom.

"I think you might just give me a hint," he suggested to Aunt Eliza, whom he shrewdly suspected knew all about it.

"Do you?" she replied. "Well, I think that Mabel is quite capable of taking care of herself and you too, and that the sooner you realise it the better. As for your being consulted or informed about your wedding trip, why, my niece has been four times round the world already, and is better able to plan an ordinary honeymoon excursion than a man who spends his time turning out bombs, and nitro-glycerine, and monitors, and things."

Aunt Eliza's notions of the duties of the War Office were still somewhat vague.

After the bridal couple had left, Miss Cogbill and Lady Scarsdale received the remaining guests, and, when the function was over, her ladyship gave her American relative a cordial invitation to stay at "The Towers" till after the honeymoon; but Aunt Eliza refused.

"I'll come some day and be glad to," she said; "but I'm off to-morrow for two weeks in Paris. I always go there when I'm blue; it cheers one up so, and you meet more Americans there nowadays than you do at home."

"Perhaps you will see the happy pair before you return," suggested Lady Scarsdale.

"Now, your ladyship," said Aunt Eliza, "that isn't fair; but to tell you the truth of the matter, I've no more idea where they are going, beyond their first stop, than you have."

"And that is——?"

"They will write you from there to-morrow," replied Miss Cogbill, "and then you will know as much as I do."

Scarsdale was quite too happy to be seriously worried over his ignorance of their destination; in fact, he was rather amused at his wife's little mystery, and, beyond indulging in some banter on the subject, was well content to let the matter drop. He entertained her, however, by making wild guesses as to where they were to pass the night from what he had learned of their point of departure, Waterloo Station; but soon turned to more engrossing topics, and before he realised it an hour had passed away, and the train began to slow up for their first stop out of London.

"Is this the end of our journey?" he queried.

"What, Basingstoke?" she cried. "How could you think I'd be so unromantic? Why, it is only a miserable, dirty railway junction!"

"Perhaps we change carriages here?"

"Wrong again; but the train stops for a few minutes, and if you'll be good you may run out and have a breath of fresh air and something to drink."

"How do you know," he asked, "that I sha'n't go forward and see how the luggage is labelled?"

"That would not be playing fair," she replied, pouting, "and I should be dreadfully cross with you."

"I'll promise to be good," he hastened to assure her, and, as the train drew up, stepped out upon the platform.

His first intention had been to make straight for the refreshment-room; but he had only taken a few steps in that direction, when he saw advancing from the opposite end of the train none other than Robert Allingford, who, like himself, was a bridegroom of that day.

"Why, Benedick!" he cried, "who would have thought of meeting you!"

"Just what I was going to say," replied the Consul, heartily shaking his outstretched hand. "I never imagined that we would select the same train. Come, let's have a drink to celebrate our auspicious meeting. There is time enough."

"Are you sure?" asked the careful Englishman.

"Quite," replied his American friend. "I asked a porter, and he said we had ten minutes."

They accordingly repaired to the luncheon-bar, and were soon discussing whiskies and sodas.

"Tell me," said the Consul, as he put down his glass, "have you discovered your destination yet?"

"Haven't the remotest idea," returned the other. "Mrs. Scarsdale insisted on buying the tickets, and watches over them jealously. If it had not been for the look of the thing, I would have bribed the guard to tell me where I was going. By the way, won't you shake hands with my wife? She is just forward."

"With pleasure," replied Allingford, "if you will return the compliment; my carriage is the first of its class at the rear of the train. We have still six minutes." With which the two husbands separated, each to seek the other's wife.

Scarsdale met with a cordial welcome from Mrs. Allingford, and was soon seated by her side chatting merrily.

"We should sympathise with each other," she said, laughing, "for I understand that we are both in ignorance of our destination."

"Indeed we should," he replied. "I dare say that at this moment your husband and my wife are gloating over their superior knowledge."

"Oh, well," she continued, "our time will come; and now tell me how you have endured the vicissitudes of the day."

"I think you and I have no cause for complaint," rejoined Scarsdale. "You see we understand our conventions; but I fear that our respective partners have not had such an easy time."

"I shouldn't think it would have worried Mrs. Scarsdale," returned the Englishwoman.

"Of course it didn't," said that lady's husband; "nothing ever worries her. But I think signing the register puzzled her a bit; she said it made her feel as if she was at an hotel."

"Robert enjoyed it thoroughly," said Mrs. Allingford.

"Had he no criticisms to offer?"

"None, except that one seemed to get a good deal more for one's money than in the States."

"The almighty dollar!" said Scarsdale, laughing, and added, as he looked at his watch: "I must be off, or your husband will be turning me out; our ten minutes are almost up."

Once on the platform, he paused aghast. The forward half of the train had disappeared, and an engine was backing up in its place to couple on to the second part. Allingford was nowhere in sight.

"Where is the rest of the train?" cried Scarsdale, seizing an astonished guard.

"The forward division, sir?"

"Yes! yes! For Heaven's sake speak, man! Where is it?"

"That was the Exeter division. Went five minutes ago."

"But I thought we had ten minutes!"

"This division, yes, sir," replied the guard, indicating that portion of the train still in the station, "the forward part only five."

In this way, then, had Allingford unconsciously deceived him, and without doubt the American Consul had been carried off with his, Scarsdale's, wife. The awful discovery staggered him, but he controlled himself sufficiently to ask the destination of the section still in the station.

"Bournemouth, sir, Southampton first stop. Are you going? we are just off."

"No," replied Scarsdale. The guard waved his flag, the shrill whistle blew, and the train began to move. Then he thought of Mrs. Allingford; he could scarcely leave her. Besides, what was the use of remaining at Basingstoke, when he did not even know his own destination? He tore open the door of the carriage he had just left, and swung himself in as it swept past him.

From what has been said it may be imagined that Mrs. Scarsdale, née Vernon, was an excellent hand at light and amusing conversation; and so pleasantly did she receive the Consul, and so amusingly rally him on the events of the day, that he scarcely seemed to have been with her a minute, when a slight jolt caused him to look up and out, only to perceive the Basingstoke Station sliding rapidly past the windows. Allingford's first impulse was to dash from the carriage, a dangerous experiment when one remembers the rapidity with which a light English train gets under way. In this, however, he was forestalled by Mrs. Scarsdale, who clung to his coat-tails, declaring that he should not desert her; so that by the time he was able to free himself the train had attained such speed as to preclude any longer the question of escape. The sensations which Mr. Allingford and Mrs. Scarsdale experienced when they realised that they were being borne swiftly away, the one from his wife and the other from her husband, may be better imagined than described. The deserted bride threw herself into the farthest corner of the carriage and began to laugh hysterically, while the Consul plunged his hands into his pockets and gave vent to a monosyllabic expletive, of which he meant every letter.

After the first moments of astonishment and stupefaction both somewhat recovered their senses, and mutual explanations and recriminations began forthwith.

"How has this dreadful thing happened?" demanded Mrs. Scarsdale, in a voice quavering with suppressed emotion.

"I'm afraid it's my fault," said Allingford ruefully. "The guard told me we had ten minutes."

"That was for your division of the train, stupid!" exclaimed the lady wrathfully.

"I didn't know that," explained the Consul, "and so I told your husband we had ten minutes, which probably accounts for his being left."

"Then I'll never, never forgive you," she cried, and burst into tears, murmuring between her sobs: "Poor, dear Harold! what will he do?"

"Do!" exclaimed the Consul, "I should think he had done enough, in all conscience. Why, confound him, he's gone off with my wife!"

"Don't you call my husband names!" sobbed Mrs. Scarsdale.

"Well, he certainly has enough of his own, that's a fact."

"If you were a man," retorted the disconsolate bride, "you would do something, instead of making stupid jokes about my poor Stanley. I'm a distressed American citizen——"

"No, you're not; you became a British subject when you married Scarsdale," corrected Allingford.

"Well, I won't be, so there! I tell you I'm an American woman in distress, and you are my Consul and you've got to help me."

"I'll help you with the greatest pleasure in the world. I'm quite as anxious to recover my wife as you can be to find your husband."

"Then what do you advise?" she asked.

"We are going somewhere at a rapid rate," he replied. "When we arrive, we will leave the train and return to Basingstoke as soon as possible. Now do you happen to know our next stop?"

"Yes: Salisbury."

"How long before we get there?"

"About three quarters of an hour."

"That will at least give us time," he said, "to consider what is best to be done. Have you a railway guide?"

"I think there is a South Western time-table in the pocket of dear Malcolm's coat," she said, indicating a garment on the seat beside her.

"Why don't you call him St. Hubart and be done with it?" queried Allingford, as he searched for and found the desired paper. "You've given him all his other names."

"I reserve that for important occasions," she replied; "it sounds so impressive."

Mabel Scarsdale, it will be noticed, was fast regaining her composure, now that a definite course of action had been determined upon. But she could not help feeling depressed, for it must be admitted that it is disheartening to lose your husband before you have been married a day. What would he do, she wondered, when he found that the train had gone? Had he discovered its departure soon enough to warn Mrs. Allingford to leave her carriage? and if not, where had she gone, and had he accompanied her? The event certainly afforded ample grounds for speculation; but her reverie was interrupted by the Consul, who had been deeply immersed in the time-table.

"There is no train back to Basingstoke before ten to-night," he said, "so we must spend the evening in Salisbury and telegraph them to await our return."

"Possibly my husband may have chased the train and caught the rear carriage. I have seen people do that," she ventured.

"The guard's van, you mean," he explained. "In that case he is travelling down with us and will put in an appearance directly we reach Salisbury, though I don't think it's likely. However, there's nothing to worry about, and I must beg you not to do so, unless you wish to make me more miserable than I already am for my share in this deplorable blunder."

"You don't think they would follow us to Salisbury?"

"No; that is"—and he plunged into the intricacies of the time-table once more—"they couldn't; besides, they would receive our telegram before they could leave Basingstoke."

"Could they have gone off on the other train?"

"Impossible," he replied. "By Jove, they neither of them know where they are bound for!"

"Quite true," she said, "they do not. We had tickets for Exeter; but as a joke I never let my husband see them."

"We were going to Bournemouth, and here are my tickets," he returned, holding them up, "but my wife doesn't know it."

"You think there is no question that they are waiting for us at Basingstoke?" she asked.

"Not a doubt of it; and so we have nothing to do but kill time till we can rejoin them, which won't be hard in your society," he replied.

"I'm sorry I can't be so polite," she returned, "but I want my husband, and if you talk to me much more I shall probably cry."

The Consul at this made a dive for an adjacent newspaper, in which he remained buried till the train slowed down for Salisbury.

"I suppose," he said apologetically, as they drew up at their destination, "that you won't object to my appropriating Scarsdale's coat and hat? I dare say he is sporting mine."

A tearful sniff was the only reply as he gathered up the various impedimenta with which the carriage was littered, and assisted his fair though doleful companion to alight. Returning a few moments later from the arduous duty of rescuing her luggage, which was, of course, labelled for Exeter, he found her still alone, there being no sign of Scarsdale in or out of the train, and no telegram for them from Basingstoke—a chance on which Allingford had counted considerably, though he had not thought it wise to mention it. Indeed, the fact that no inquiry had been made for them puzzled and worried him greatly, for it seemed almost certain that were their deserted partners still at Basingstoke, their first action would have been to telegraph to the fugitives. However, he put the best face he could on the matter, assured Mrs. Scarsdale that everything must be all right, and despatched his telegram back to their point of separation. Under the most favourable circumstances they could not receive an answer under half an hour, and with this information the Consul was forced to return to the disconsolate bride.

"There is no use in loafing around here," he said. "Suppose we go and see the cathedral? It will be something to do, and may distract our thoughts."

"I don't think mine could well be more distracted than they are now," replied she; "besides, we might miss the telegram."

"Oh, I'll fix that," he returned; "I'll have it sent up after us. Come, you had better go. You can't sit and look at that pea-green engine for thirty minutes; it is enough to give you a fit of the blues."

"Well, just as you please," she said, and they started up into the town, and made their way to the cathedral.

It is not to the point of this narrative to discourse on the beauties of that structure; the finest shaft of Purbec marble it contains would prove cold consolation to either a bride or a bridegroom deserted on the wedding day. But the cool quiet of the great building seemed unconsciously to soothe their troubled spirits, though when they each revisited the spot in after years they discovered that it was entirely new to them, and that they possessed not the faintest recollection of its appearance, within or without.

At last, after having consulted their watches for the hundredth time, they began to stroll down the great central aisle, towards the main entrance. Suddenly Mrs. Scarsdale clutched the Consul's arm, and pointed before her to where a messenger-boy, with a look of expectancy on his face and an envelope in his hand, stood framed in a Gothic doorway. Then they made a wild, scrambling rush down the church, the bride reaching the goal first, and snatching the telegram from its astonished bearer.

"For Mr. Allingford," he began, but she had already torn open the envelope and was devouring its contents.

For a moment the words seemed to swim before her eyes, then, as their meaning became clear to her, she gave a frightened gasp, dropped the message on the floor, sat down hard on the tomb of a crusader, and burst into tears.

Allingford gazed at her silently for a moment, and meditatively scratched his head; then he paid and dismissed the amazed boy, and finally picked up the crumpled bit of paper. It was from the station-master at Basingstoke, and read as follows:

"Parties mentioned left in second division for Southampton and South Coast Resorts. Destination not known."

It was incomprehensible, but he had expected it. If Mr. Scarsdale had remained at Basingstoke he would certainly have telegraphed them from there at their first stop, Salisbury. Evidently he, too, had been carried away on the train; but where? It was some relief to know that his wife was not wholly alone, but he did not at all like the idea of her going off into space with another man, and the fact that he had done the same thing himself was no consolation. Then his mind reverted to Mrs. Scarsdale, who still wept on the tomb of the crusader. What in thunder was he going to do with her? To get her back to her aunt in London at that time of night was out of the question; but where else could he take her?

This point, however, was settled at once, and in an unexpected manner, by the lady herself. Drying her eyes, she remarked suddenly: "I'm a little fool!"

"Not at all," he replied; "your emotion is quite natural under the circumstances."

"But crying won't get us out of this awful predicament."

"Unfortunately no, or we should have arrived at a solution long ago."

"That," remarked the lady, "is merely another way of making a statement which you just now disputed. I am a little fool, and I mean to dry my eyes and attend strictly to business. Tell me exactly what this message implies."

"It means," said the Consul, "that it is impossible for you to rejoin your husband to-night."

Her lip quivered dangerously; but she controlled herself sufficiently to exclaim: "But what are we to do?"

"Well," he replied, "I should advise remaining here. There is a good hotel."

"But we can't. Don't you see I must not remain—with you?" She spoke the last words with an effort.

"Yes," he rejoined. "It is awkward; but you can't spend the night in the streets; you must have somewhere to sleep."

"Let us go back to Basingstoke, then."

"I can't see that that would help matters," he said gloomily; "we would have to spend the night there just the same. Besides, I think it is going to rain." They were standing outside the church by this time. "No," he continued, "our best course, our only course, in fact, is to stay here to-night, return to Basingstoke to-morrow morning, and wait for them there. You may be sure they are having quite as bad a time as we are. If I only knew some one here——"

"Bravo!" she interrupted, clapping her hands, "I believe you have solved the problem. Look: do you see that carriage over there? What coat of arms has it? Quick! your eyes are better than mine."

In the gathering twilight he saw driving leisurely by, with coachman and footman on the box, a handsome barouche, on the panels of which a coat of arms was emblazoned.

"Well," he said, gazing hard at it, "there is a helmet with a plume, balanced on a stick of peppermint candy——"

"Yes, yes!" she cried, "the crest. Go on!"

"Down on the ground-storey," he continued, "there is a pink shield divided in quarters, with the same helmet in the north-east division, and a lot of silver ticket-punchers in the one below it."

"Spurs," she interjected.

"Well, perhaps they are," he admitted. "Then there are a couple of two-tailed blue lions swimming in a crimson lake——"

"The Melton arms!" she cried. "I looked them up in 'Burke's Peerage' when that old catawampus refused to come to our wedding. We will spend to-night with Lady Diana!"

"But I thought——" began the Consul, when his companion interrupted him, exclaiming:

"Chase that carriage as hard as you know how, and bring it here!"

Allingford felt that this was a time for action and not for speech. The days of his collegiate triumphs, when he had put his best foot foremost on the cinder-track, rose to his mind, and he fled across the green and into the gathering gloom, which had now swallowed up her ladyship's chariot, with a swiftness that caused his companion to murmur: "Well, he can sprint!"

Presently the equipage was seen returning with the heated and triumphant Consul inside. It drew up before her, and the footman alighted and approached questioningly.

"Is this Lady Melton's carriage?" she asked.

"Yes, madam."

"Then you may drive this gentleman and me to Melton Court."

"But, madam——"

"I am Mrs. Scarsdale, Lady Diana's great-niece," she said quietly. The footman touched his hat.

"Was her ladyship expecting you? We were sent to meet this next train, but——"

"No, we are here unexpectedly ourselves; but I dare say there will be room for all, as the carriage holds four."

"There will only be Lord Cowbray, madam, and his lordship may not arrive till the nine-thirty. If you would not mind driving to the station?"

"It is just what we wish," she replied, and calmly stepped into the carriage and seated herself by the Consul's side, who was so amazed at the turn affairs had taken that he remained speechless.

"Shall I see to your luggage, madam?" inquired the footman as they drew up opposite the waiting-room door.

"No," she replied, stepping out on the platform. "We will attend to it ourselves; it will only be necessary to take up our hand-bags for to-night."

Accompanied by the Consul she went in search of their belongings, and at her suggestion he took a Gladstone belonging to the absent Scarsdale, and a dressing-case which she designated as her own property.

"I was anxious to have a word alone with you," she said as they emerged once more on the platform, "and we can't talk on personal matters during the drive to the Court. You see my position is a little peculiar."

"Excuse me for asking the question," he replied, "but are your relations with your husband's great-aunt quite cordial?"

"On the contrary, they are quite the reverse. She detests all Americans, and was very much put out at poor Harold for marrying me. Her refusal to be present at our wedding was almost an insult," she returned.

"That doesn't seem to promise a pleasant reception at Melton Court," he said.

"Far from it; but any port is acceptable in a storm, and she can hardly refuse us shelter. After all I've done nothing to be ashamed of in marrying my husband or being carried off with you."

"Oh, I'll trust you to hold your own with any dowager in the United Kingdom; but where do I come in?"

"You are my Consul, and under the circumstances my national protector; I can't do without you."

"I am not at all sure that her ladyship will see it in that light; but, as you say, it is better than nothing, and our position can't be worse than it is at present."

"Then it is agreed we stand by each other through thick and thin?"

"Exactly," he replied, and shook her extended hand. At this moment the train came in, and they returned to the carriage.

Lord Cowbray did not put in an appearance, and they were soon under way for Melton Court, which was some miles distant from the town. By the time they entered the grounds it was quite dark, and they could only see that the park was extensive, and that the Court seemed large and gloomy and might have dated from the Elizabethan period.

On entering the central hall they at once saw evidences of a large house-party, whose presence did not tend to put them more at their ease, and Mrs. Scarsdale lost no time in sending a message to Lady Melton, to the effect that her great-niece had arrived unexpectedly and would much appreciate a few words with her in private.

They were shown into a little reception-room, and the footman returned shortly to say that her ladyship would be with them soon. After what seemed an endless time, but was in reality barely fifteen minutes, their hostess entered. She was a fine-looking woman of sixty or over, with a stern, hard face, and a set expression about her thin lips, that boded little good to offenders, whatever their age or sex. She looked her guests over through her gold eye-glasses, and, after waiting a moment for them to speak, said coldly:

"I think there is some mistake. I was told that my niece wished to see me."

"I said your great-niece," returned Mrs. Scarsdale.

"Oh, my great-niece. Well? I do not recognise you."

"It would be strange if you did, Lady Melton," returned the bride, "as you've never seen me. I am the wife of your great-nephew, Harold Stanley Malcolm St. Hubart Scarsdale."

"I do not see your husband present," said her ladyship, directing an icy glare at the unfortunate Consul.

"No," replied her niece, "I've lost him."

"Lost him!"

"Yes, at Basingstoke. He went to speak to a lady in another part of the train. I could make it clearer to you, I think, by saying that she was Sir Peter Steele's youngest daughter."

"I never thought of knowing the Steeles when I was in London," commented her hostess, "but St. Hubart was always liberal in his tastes." A remark which caused the Consul to flush with pent-up wrath.

"Oh, he didn't know her," interjected Mabel, hastening to correct the unfortunate turn which the conversation had taken. "She was this gentleman's wife."

Her ladyship bowed very, very slightly in the Consul's direction, to indicate that his affairs, matrimonial or otherwise, could have for her no possible interest.

"And that is the last we have heard of them," continued the bride, "except for a telegram from the station-master at Basingstoke, which says they went to Southampton——"

"Do I understand you to say," broke in their hostess, betraying the first sign of interest she had so far evinced, "that my nephew has eloped with——?"

"No, no!" cried Mrs. Scarsdale, "you do not in the least comprehend the true state of affairs," and she poured forth a voluble if disconnected account of their adventures.

"Pardon me," exclaimed the old lady when she had finished, "but what is all this rigmarole? A most surprising affair, I must say, and quite worthy of your nationality. I was averse to my nephew's marrying you from the first; but I hardly expected to be justified on his wedding day."

"In that case," said Mrs. Scarsdale, "the sooner we leave your house the better."

"You will do nothing of the sort," replied her great-aunt. "Your coming to me is the only wise thing you have done. Of course you will remain here till your husband can be found. As for this person——" indicating Allingford.

"This gentleman," said his partner in misfortune, coming to his rescue, "is Mr. Robert Allingford, United States Consul at Christchurch. As my husband had gone off with his wife, I thought the least I could do was to take him with me."

"I can hardly see the necessity of that course," commented her hostess.

"Now that I have seen Mrs. Scarsdale in safe hands, I could not think of trespassing longer upon your hospitality," put in the Consul; but his companion intervened.

"I am not going to be deserted twice in a day!" she cried. "If you go, I go with you!"

"About that," said her ladyship frigidly, "there can be no question," and she rang the bell.

"You will conduct this lady and this gentleman," she continued to the footman who answered her summons, "to the green room and the tower room respectively." Then, turning to her unwilling guests, she added: "As my dinner-table is fully arranged for this evening, and my guests are now awaiting me, you will pardon it if I have your dinner served in my private sitting-room. We will discuss your affairs at length to-morrow morning; but now I must bid you good-night," and with an inclination of her head she dismissed them from her presence.

Scarcely had the sun risen the next morning when the Consul, after a sleepless night, stole downstairs and found his way out upon the terrace, for a quiet stroll and a breath of fresh, cool air. Moreover, he was in need of an uninterrupted hour in which to arrange his plans in such a manner as would most surely tend to effect the double reunion he so earnestly desired.

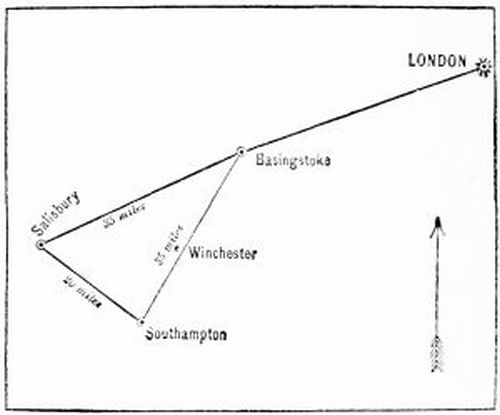

It seemed well-nigh impossible, in the small space of country which had probably been traversed by all parties, that they could lose each other for more than a few hours. To make the situation more clear to those who have never had the misfortune to suffer from the intricacies of English railway travel, the following diagram is appended. The triangle is isosceles, the sides being thirty-five miles long, the base twenty.

He reviewed his own adventures of yesterday afternoon. He had acted on what seemed to be the only sensible and reasonable plan to pursue; namely, to leave the train at its first stop, and return as soon as possible to the point of divergence. It seemed fair to assume that Mr. Scarsdale and Mrs. Allingford had done the same thing, and, such being the case, it was easy to imagine what their course of action had been. A glance at the time-table told him that the first point at which they could leave their division of the train had been Southampton; from which place they could, almost immediately, catch an express back to the junction they had left, arriving there shortly after seven on the past evening.

His own course and that of Mrs. Scarsdale seemed clear; it was simply a return to Basingstoke immediately after breakfast, and rejoin their friends, who had been spending the night at that place.

It was possible that they had lost the returning express and remained in Southampton; but if they acted in a rational manner, they must eventually return to the junction. But supposing Mrs. Allingford and Mr. Scarsdale had not done the obvious thing; supposing that chance had intervened and upset their plans, as in his own case? He suddenly found himself face to face with the startling fact that not only were he and Mrs. Scarsdale not at Salisbury or Basingstoke, but that they were at present at the one place where his wife and Mrs. Scarsdale's husband would never think of looking for them—Melton Court.

Allingford jammed his hat hard on the back of his head, and set off at a brisk pace to Salisbury and the nearest telegraph station; arriving at his destination shortly before seven, to find that he had a good half-hour to wait before the operators arrived. The office was opened at last, however, and he lost no time in telegraphing to Basingstoke for information, and in a little while received an answer from the station-master at that point which cheered him up considerably, though it was not quite as explicit as he could have wished. It read as follows:

"Scarsdale telegraphed last evening from Southampton, saying he had left train there with Mrs. Allingford and was returning at once to Basingstoke."

The Consul was pleased to find that his conjectures had been correct. He felt that a great weight had been lifted from his mind. Their missing partners had undoubtedly spent the night at Basingstoke and would soon consult the station-master at that point, who would doubtless show them the messages he had received. Allingford looked out a good train, telegraphed the hour of their arrival, and then, as his reception of the night before had not inclined him to trespass on Lady Melton's grudging hospitality more than was absolutely necessary, he had a leisurely breakfast at the hotel, and, engaging a fly, drove back to the Court, reaching there about half-past nine.

Mrs. Scarsdale had also passed a disturbed night, but, unlike her companion in misfortune, she did not venture out at unearthly hours in the morning. She was up, however, and saw him depart, which was in some ways a comfort, since it assured her that he was losing no time in continuing their quest.

At eight a maid arrived with warm water and a message from her ladyship that she wished Mrs. Scarsdale to breakfast with her in private at nine o'clock, and that she would be obliged if her great-niece would keep her room till that time. The bride was considerably piqued by this message and the distrust it implied, but felt it would be wise to accede to the request, and sent word accordingly.

As she entered Lady Melton's boudoir an hour later, her hostess rose to receive her, kissing her coldly on the forehead, and saying:

"You will pardon my requesting you to keep your room; but your presence is not as yet known to my guests, and your appearance among them immediately after your marriage, without your husband, might cause unpleasant speculation and comment. Do you agree with me?"

"Quite," replied Mrs. Scarsdale. She had misjudged Lady Melton, she thought; but she disliked her nevertheless, and wished to be very guarded.

"Now," said that personage, "I want to hear the whole affair. No, I do not want you to tell it," as her guest opened her mouth to speak; "not in your own way, I mean. You would probably wander from the point, and my time is of importance. I will ask you questions, and you will be kind enough to answer them, as plainly and shortly as possible."

Mrs. Scarsdale bowed; she was so angry at the cool insolence that this statement implied that she did not feel she could trust herself to speak.

"Now we will begin," said her ladyship, as she proceeded to demolish a boiled egg. "What is your Christian name?"

"Mabel."

"Very well. Then I shall call you Mabel in future; it is ridiculous to address you as Mrs. Scarsdale."

"I really don't see——" began that lady.

"Excuse me," interrupted her questioner, "I will make the comments when necessary. When were you married?"

"Yesterday afternoon at two-thirty o'clock."

"Where did you and your husband intend to pass last night?"

"At Exeter."

"Are you sure?"

"I ought to be. I bought the tickets."

"You bought the tickets! Is that customary in your country?"

"I am not here to discuss the customs of my country, Lady Melton. I bought the tickets because I chose to do so, and considered myself better fitted to arrange the trip than my husband."

"Really! I suppose that is the reason you selected the most roundabout way to reach Exeter. Your husband could have told you that you should have taken another railway, the Great Western."

"My husband," said Mrs. Scarsdale stiffly, "did not know our destination."

"What!"

"I say that my husband did not know our destination."

Her ladyship surveyed her for a moment in shocked and silent disapproval, and then remarked:

"I think I understood you to say that you travelled together as far as Basingstoke?"

"Yes, and there St. Hubart met a friend."

"This consular person?"

"Mr. Allingford? Yes. He was also married yesterday, and came to our carriage to congratulate me."

"And my nephew went to speak to Mrs. Allingford."

"Exactly. And the first thing we knew the train was moving."

"Go on."

"That is just what we did, though Mr. Allingford tried to leave the carriage and return to his wife."

"It would have been better had he never left her."

"But I restrained him."

"How did you restrain him?"

"By his coat-tails."

"Excuse me. Do I understand you to say that you forcibly detained him?"

"I'm sorry if you are shocked; it was all I could catch hold of."

"I shall reserve my criticism of these very astonishing performances, Mabel; but permit me to say that you have much to learn concerning the manners and customs of English society."

"Then," said Mrs. Scarsdale, ignoring this last remark, "we came to Salisbury."

"And telegraphed to Basingstoke for information."

"Exactly. But they could tell us nothing; so when I saw your carriage——"

"How did you know it was mine?"

"I looked out your coat of arms in 'Burke.'"

Her ladyship smiled grimly. Perhaps something might be made of this fair barbarian—in time, a great deal of time; but still this knowledge of the peerage sounded hopeful, and it was with a little less severity in her voice that she demanded:

"And what do you mean to do now?"

"Go back to Basingstoke this morning."

"Alone?"

"No, with Mr. Allingford."

"Do you expect to find your husband there?"

"I should think he would naturally return as soon as possible to where he lost me."

"I don't know," said her ladyship. "Was Mrs. Allingford pretty?"

"If you are going to adopt that tack, Lady Melton, the sooner we part the better," said her visitor angrily.

"We do not 'adopt tacks' in England," returned her ladyship calmly; "and as I consider myself responsible for your actions while you are under my roof, I shall not allow you to go to Basingstoke, or anywhere else, with a person who, whatever his official position, is totally unknown to me."

"You don't mean to keep me here against my will!"

"I mean to send you to your relations, wherever they are, under the charge of my butler—a most respectable married man—provided the journey can be accomplished between now and nightfall."

"Well, it can't," replied her grand-niece triumphantly. "Aunt Eliza left for Paris this morning, and all my other relations are in Chicago."

Lady Melton was, however, a woman of decision, and not to be easily baffled.

"Then I will send you to your mother-in-law, Lady Scarsdale; I suppose she has returned to 'The Towers'?"

"I believe so. But I do not intend to go there without my husband; it would be ignominious."

"Perhaps you can suggest a better plan," said her ladyship coldly.

"Well, if you refuse to let me go to Basingstoke——" began the bride.

"I do. Proceed."

"Then Mr. Allingford might go for me, and tell St. Hubart where I am. I know he is waiting for me there, but he would never think of my being here——Excuse me, I mean——" she stammered, blushing, for she saw she had made a slip.

"We will not discuss your meaning," said her hostess, "but your plan seems feasible and proper. You may receive the consular person in my private sitting-room and arrange matters at once."