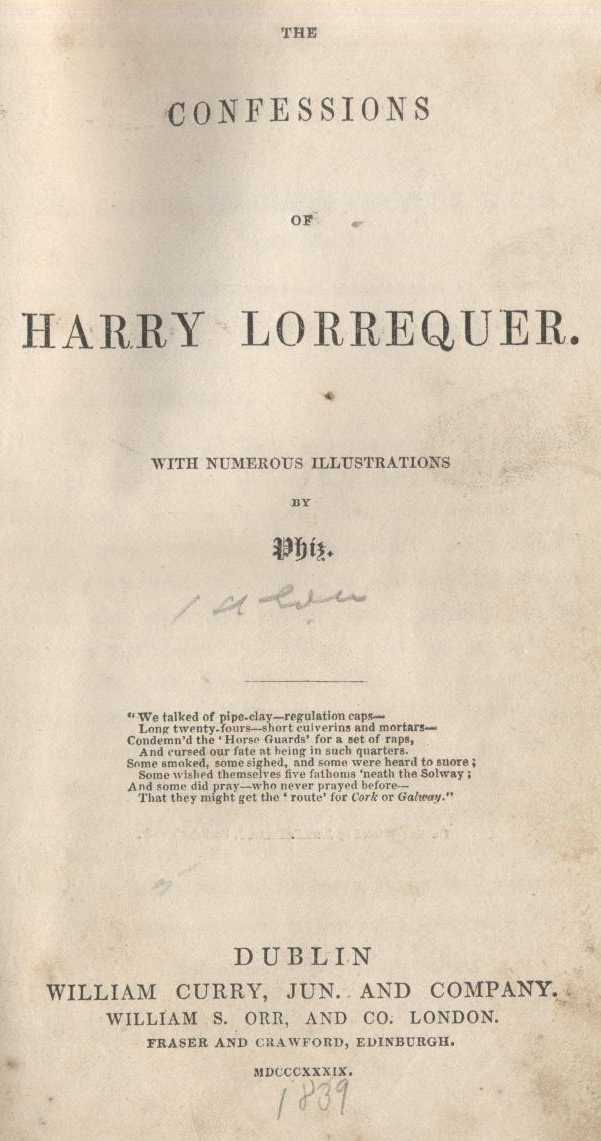

The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Confessions of Harry Lorrequer, Complete by Charles James Lever (1806-1872) This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net Title: The Confessions of Harry Lorrequer, Complete Author: Charles James Lever (1806-1872) Release Date: October 27, 2006 [EBook #5240] Last Updated: August, 2016 Language: English Character set encoding: UTF-8 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK HARRY LORREQUER, COMPLETE *** Produced by Mary Munarin and David Widger

[Note: Though the title page has no author’s name inscribed,

this work is widely attributed to Charles James Lever.]

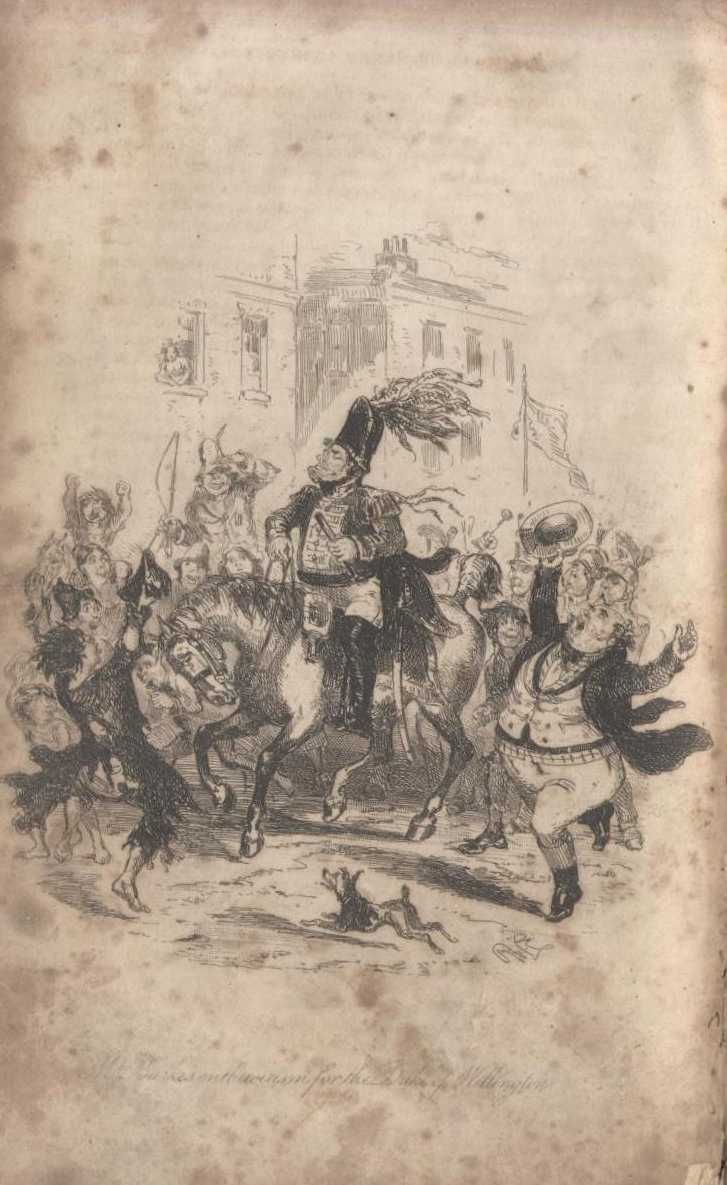

Click on this box here or with any of the following images to view the engraving in sharper black and white detail.

“We talked of pipe-clay regulation caps—

Long twenty-fours—short culverins and mortars—

Condemn’d the ‘Horse Guards’ for a set of raps,

And cursed our fate at being in such quarters.

Some smoked, some sighed, and some were heard to snore;

Some wished themselves five fathoms ‘neat the Solway;

And some did pray—who never prayed before—

That they might get the ‘route’ for Cork or Galway."

CHAPTER I

Arrival in Cork—Civic

Festivities—Private Theatricals

CHAPTER

II

Detachment Duty—The Burton Arms—Callonby

CHAPTER III

Life at Callonby—Love-making—Miss

O’Dowd’s Adventure

CHAPTER IV

Botanical Studies—The Natural System preferable to the Linnaean

CHAPTER V

Puzzled—Explanation—Makes

bad worse—The Duel

CHAPTER VI

The Priest’s Supper—Father Malachi and the Coadjutor—Major

Jones and the Abbe

CHAPTER VII

The

Lady’s Letter—Peter and his Acquaintances—Too late

CHAPTER VIII

Congratulations—Sick Leave—How

to pass the Board

CHAPTER IX

The Road—Travelling

Acquaintances—A Packet Adventure

CHAPTER

X

Upset—Mind and Body

CHAPTER

XI

Cheltenham—Matrimonial Adventure—Showing how to

make love for a friend

CHAPTER XII

Dublin—Tom O’Flaherty—A Reminiscence of the Peninsula

CHAPTER XIII

Dublin—The

Boarding-house—Select Society

CHAPTER

XIV

The Chase

CHAPTER XV

Mems Of the North Cork

CHAPTER XVI

Theatricals

CHAPTER XVI b (The chapter

number is a repeat)

The Wager

CHAPTER

XVII

The Elopement

CHAPTER XVIII

Detachment Duty—An Assize Town

CHAPTER

XIX

The Assize Town

CHAPTER XX A

Day in Dublin

CHAPTER XXI

A Night at

Howth

CHAPTER XXII

The Journey

CHAPTER XXIII

Calais

CHAPTER XXIV

The Gen d'Arme

CHAPTER XXV

The Inn at Chantraine

CHAPTER XXVI

Mr O'Leary

CHAPTER

XXVII

Paris

CHAPTER XXVIII

Paris

CHAPTER XXIX

Captain

Trevanion's Adventure

CHAPTER XXX

Difficulties

CHAPTER XXXI

Explanation

CHAPTER XXXII

Mr

O'Leary’s First Love

CHAPTER XXXIII

Mr O’Leary's Second Love

CHAPTER XXXIV The

Duel

CHAPTER XXXV

Early

Recollections—A First Love

CHAPTER XXXVI

Wise Resolves

CHAPTER XXXVII

The

Proposal

CHAPTER XXXVIII

Thoughts

upon Matrimony in general, and in the Army

in particular—The

Knight of Kerry and Billy M'Cabe

CHAPTER XXXIX

A Reminiscence

CHAPTER XL

The Two

Letters

CHAPTER XLI

Mr O’Leary's

Capture

CHAPTER XLII

The Journey

CHAPTER XLIII

The Journey

CHAPTER XLIV

A Reminscence of the East

CHAPTER XLV

A Day in the Phoenix

CHAPTER XLVI

An Adventure in Canada

CHAPTER XLVII

The Courier's Passport

CHAPTER XLVIII

A Night in Strasbourg

CHAPTER XLIX

A Surprise

CHAPTER L

Jack Waller's Story

CHAPTER LI

Munich

CHAPTER

LII

Inn at Munich

CHAPTER LIII

The Ball

CHAPTER LIV

A Discovery

CHAPTER LV

Conclusion

To Sir George Hamilton Seymour, G.C.H.

My Dear Sir Hamilton,

If a feather will show how the wind blows, perhaps my dedicating to you even as light matter as these Confessions may in some measure prove how grateful I feel for the many kindnesses I have received from you in the course of our intimacy. While thus acknowledging a debt, I must also avow that another motive strongly prompts me upon this occasion. I am not aware of any one, to whom with such propriety a volume of anecdote and adventure should be inscribed, as to one, himself well known as an inimitable narrator. Could I have stolen for my story, any portion of the grace and humour with which I have heard you adorn many of your own, while I should deem this offering more worthy of your acceptance, I should also feel more confident of its reception by the public.

With every sentiment of esteem and regard, Believe me very faithfully

yours, THE AUTHOR Bruxelles, December, 1839.

Dear Public,

When first I set about recording the scenes which occupy these pages, I had no intention of continuing them, except in such stray and scattered fragments as the columns of a Magazine (FOOTNOTE: The Dublin University Magazine.) permit of; and when at length I discovered that some interest had attached not only to the adventures, but to their narrator, I would gladly have retired with my “little laurels” from a stage, on which, having only engaged to appear between the acts, I was destined to come forward as a principal character.

Among the “miseries of human life,” a most touching one is spoken of—the being obliged to listen to the repetition of a badly sung song, because some well-wishing, but not over discreet friend of the singer has called loudly for an encore.

I begin very much to fear that something of the kind has taken place here, and that I should have acted a wiser part, had I been contented with even the still small voice of a few partial friends, and retired from the boards in the pleasing delusion of success; but unfortunately, the same easy temperament that has so often involved me before, has been faithful to me here; and when you pretended to be pleased, unluckily, I believed you.

So much of apology for the matter—a little now for the manner of my offending, and I have done. I wrote as I felt—sometimes in good spirits, sometimes in bad—always carelessly—for, God help me, I can do no better.

When the celibacy of the Fellows of Trinity College, Dublin, became an active law in that University, the Board proceeded to enforce it, by summoning to their presence all the individuals who it was well known had transgressed the regulation, and among them figured Dr. S., many of whose sons were at the same time students in the college. “Are you married, Dr. S——-r?” said the bachelor vice-provost, in all the dignity and pride of conscious innocence. “Married!” said the father of ten children, with a start of involuntary horror;—“married?” “Yes sir, married.” “Why sir, I am no more married than the Provost.” This was quite enough—no further questions were asked, and the head of the University preferred a merciful course towards the offender, to repudiating his wife and disowning his children. Now for the application. Certain captious and incredulous people have doubted the veracity of the adventures I have recorded in these pages; I do not think it necessary to appeal to concurrent testimony and credible witnesses for their proof, but I pledge myself to the fact that every tittle I have related is as true as that my name is Lorrequer—need I say more?

Another objection has been made to my narrative, and I cannot pass it by without a word of remark;—“these Confessions are wanting in scenes of touching and pathetic interest” (FOOTNOTE: We have the author’s permission to state, that all the pathetic and moving incidents of his career he has reserved for a second series of “Confessions,” to be entitled “Lorrequer Married?”—Publisher’s Note.)—true, quite true; but I console myself on this head, for I remember hearing of an author whose paraphrase of the book of Job was refused by a publisher, if he could not throw a little more humour into it; and if I have not been more miserable and more unhappy, I am very sorry for it on your account, but you must excuse my regretting it on my own. Another story and I have done;—the Newgate Calendar makes mention of a notorious housebreaker, who closed his career of outrage and violence by the murder of a whole family, whose house he robbed; on the scaffold he entreated permission to speak a few words to the crowd beneath, and thus addressed them:—“My friends, it is quite true I murdered this family; in cold blood I did it—one by one they fell beneath my hand, while I rifled their coffers, and took forth their effects; but one thing is imputed to me, which I cannot die without denying—it is asserted that I stole an extinguisher; the contemptible character of this petty theft is a stain upon my reputation, that I cannot suffer to disgrace my memory.” So would I now address you for all the graver offences of my book; I stand forth guilty—miserably, palpably guilty—they are mine every one of them; and I dare not, I cannot deny them; but if you think that the blunders in French and the hash of spelling so widely spread through these pages, are attributable to me; on the faith of a gentleman I pledge myself you are wrong, and that I had nothing to do with them. If my thanks for the kindness and indulgence with which these hastily written and rashly conceived sketches have been received by the press and the public, are of any avail, let me add, in conclusion, that a more grateful author does not exist than

HARRY LORREQUER

“Story! God bless you; I have none to tell, sir.”

It is now many—do not ask me to say how many—years since I received from the Horse Guards the welcome intelligence that I was gazetted to an ensigncy in his Majesty’s __th Foot, and that my name, which had figured so long in the “Duke’s” list, with the words “a very hard case” appended, should at length appear in the monthly record of promotions and appointments.

Since then my life has been passed in all the vicissitudes of war and peace. The camp and the bivouac—the reckless gaiety of the mess-table—the comfortless solitude of a French prison—the exciting turmoils of active service—the wearisome monotony of garrison duty, I have alike partaken of, and experienced. A career of this kind, with a temperament ever ready to go with the humour of those about him will always be sure of its meed of adventure. Such has mine been; and with no greater pretension than to chronicle a few of the scenes in which I have borne a part, and revive the memory of the other actors in them—some, alas! Now no more—I have ventured upon these “Confessions.”

If I have not here selected that portion of my life which most abounded in striking events and incidents most worthy of recording, my excuse is simply, because being my first appearance upon the boards, I preferred accustoming myself to the look of the house, while performing the “Cock,” to coming before the audience in the more difficult part of Hamlet.

As there are unhappily impracticable people in the world, who, as Curran expressed it, are never content to know “who killed the gauger, if you can’t inform them who wove his corduroys”—to all such I would, in deep humility, say, that with my “Confessions” they have nothing to do—I have neither story nor moral—my only pretension to the one, is the detail of a passion which marked some years of my life; my only attempt at the other, the effort to show how prolific in hair-breadth ‘scapes may a man’s career become, who, with a warm imagination and easy temper, believes too much, and rarely can feign a part without forgetting that he is acting. Having said thus much, I must once more bespeak the indulgence never withheld from a true penitent, and at once begin my “Confessions.”

It was on a splendid morning in the autumn of the year 181_ that the Howard transport, with four hundred of his Majesty’s 4_th Regt., dropped anchor in the beautiful harbour of Cove; the sea shone under the purple light of the rising sun with a rich rosy hue, beautifully in contrast with the different tints of the foliage of the deep woods already tinged with the brown of autumn. Spike Island lay “sleeping upon its broad shadow,” and the large ensign which crowns the battery was wrapped around the flag-staff, there not being even air enough to stir it. It was still so early, that but few persons were abroad; and as we leaned over the bulwarks, and looked now, for the first time for eight long years, upon British ground, many an eye filled, and many a heaving breast told how full of recollections that short moment was, and how different our feelings from the gay buoyancy with which we had sailed from that same harbour for the Peninsula; many of our best and bravest had we left behind us, and more than one native to the land we were approaching had found his last rest in the soil of the stranger. It was, then, with a mingled sense of pain and pleasure, we gazed upon that peaceful little village, whose white cottages lay dotted along the edge of the harbour. The moody silence our thoughts had shed over us was soon broken: the preparations for disembarking had begun, and I recollect well to this hour how, shaking off the load that oppressed my heart, I descended the gangway, humming poor Wolfe’s well-known song—

|

“Why, soldiers, why Should we be melancholy, boys?" |

And to this elasticity of spirits—whether the result of my profession, or the gift of God—as Dogberry has it—I know not—I owe the greater portion of the happiness I have enjoyed in a life, whose changes and vicissitudes have equalled most men’s.

Drawn up in a line along the shore, I could scarce refrain from a smile at our appearance. Four weeks on board a transport will certainly not contribute much to the “personnel” of any unfortunate therein confined; but when, in addition to this, you take into account that we had not received new clothes for three years—if I except caps for our grenadiers, originally intended for a Scotch regiment, but found to be all too small for the long-headed generation. Many a patch of brown and grey, variegated the faded scarlet, “of our uniform,” and scarcely a pair of knees in the entire regiment did not confess their obligations to a blanket. But with all this, we shewed a stout, weather-beaten front, that, disposed as the passer-by might feel to laugh at our expense, very little caution would teach him it was fully as safe to indulge it in his sleeve.

The bells from every steeple and tower rung gaily out a peal of welcome as we marched into “that beautiful city called Cork,” our band playing “Garryowen”—for we had been originally raised in Ireland, and still among our officers maintained a strong majority from that land of punch, priests, and potatoes—the tattered flag of the regiment proudly waving over our heads, and not a man amongst us whose warm heart did not bound behind a Waterloo medal. Well—well! I am now—alas, that I should say it—somewhat in the “sear and yellow;” and I confess, after the experience of some moments of high, triumphant feeling, that I never before felt within me, the same animating, spirit-filling glow of delight, as rose within my heart that day, as I marched at the head of my company down George’s-street.

We were soon settled in barracks; and then began a series of entertainments on the side of the civic dignities of Cork, which soon led most of us to believe that we had only escaped shot and shell to fall less gloriously beneath champagne and claret. I do not believe there is a coroner in the island who would have pronounced but the one verdict over the regiment—“Killed by the mayor and corporation,” had we so fallen.

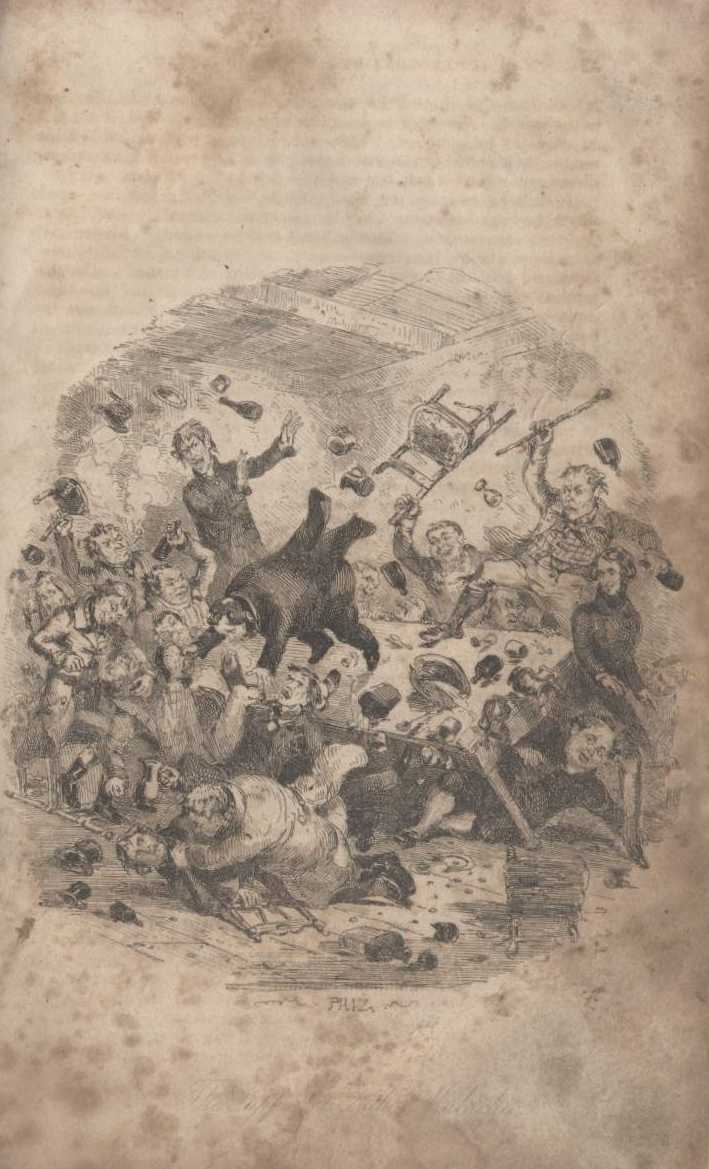

First of all, we were dined by the citizens of Cork—and, to do them justice, a harder drinking set of gentlemen no city need boast; then we were feasted by the corporation; then by the sheriffs; then came the mayor, solus; then an address, with a cold collation, that left eight of us on the sick-list for a fortnight; but the climax of all was a grand entertainment given in the mansion-house, and to which upwards of two thousand were invited. It was a species of fancy ball, beginning by a dejeune at three o’clock in the afternoon, and ending—I never yet met the man who could tell when it ended; as for myself, my finale partook a little of the adventurous, and I may as well relate it.

After waltzing for about an hour with one of the prettiest girls I ever set eyes upon, and getting a tender squeeze of the hand, as I restored her to a most affable-looking old lady in a blue turban and a red velvet gown who smiled most benignly on me, and called me “Meejor,” I retired to recruit for a new attack, to a small table, where three of ours were quaffing “ponche a la Romaine,” with a crowd of Corkagians about them, eagerly inquiring after some heroes of their own city, whose deeds of arms they were surprised did not obtain special mention from “the Duke.” I soon ingratiated myself into this well-occupied clique, and dosed them with glory to their hearts’ content. I resolved at once to enter into their humour; and as the “ponche” mounted up to my brain I gradually found my acquaintanceship extend to every family and connexion in the country.

“Did ye know Phil Beamish of the 3_th, sir?” said a tall, red-faced, red-whiskered, well-looking gentleman, who bore no slight resemblance to Feargus O’Connor.

“Phil Beamish!” said I. “Indeed I did, sir, and do still; and there is not a man in the British army I am prouder of knowing.” Here, by the way, I may mention that I never heard the name till that moment.

“You don’t say so, sir?” said Feargus—for so I must call him, for shortness sake. “Has he any chance of the company yet, sir?”

“Company!” said I, in astonishment. “He obtained his majority three months since. You cannot possibly have heard from lately, or you would have known that?”

“That’s true, sir. I never heard since he quitted the 3_th to go to Versailles, I think they call it, for his health. But how did he get the step, sir?”

“Why, as to the company, that was remarkable enough!” said I, quaffing off a tumbler of champagne, to assist my invention. “You know it was about four o’clock in the afternoon of the 18th that Napoleon ordered Grouchy to advance with the first and second brigade of the Old Guard and two regiments of chasseurs, and attack the position occupied by Picton and the regiments under his command. Well, sir, on they came, masked by the smoke of a terrific discharge of artillery, stationed on a small eminence to our left, and which did tremendous execution among our poor fellows—on they came, Sir; and as the smoke cleared partially away we got a glimpse of them, and a more dangerous looking set I should not desire to see: grizzle-bearded, hard-featured, bronzed fellows, about five-and-thirty or forty years of age; their beauty not a whit improved by the red glare thrown upon their faces and along the whole line by each flash of the long twenty-fours that were playing away to the right. Just at this moment Picton rode down the line with his staff, and stopping within a few paces of me, said, ‘They’re coming up; steady, boys; steady now: we shall have something to do soon.’ And then, turning sharply round, he looked in the direction of the French battery, that was thundering away again in full force, ‘Ah, that must be silenced,’ said he, ‘Where’s Beamish?’—“Says Picton!” interrupted Feargus, his eyes starting from their sockets, and his mouth growing wider every moment, as he listed with the most intense interest. “Yes,” said I, slowly; and then, with all the provoking nonchalance of an Italian improvisatore, who always halts at the most exciting point of his narrative, I begged a listener near me to fill my glass from the iced punch beside him. Not a sound was heard as I lifted the bumper to my lips; all were breathless in their wound-up anxiety to hear of their countryman who had been selected by Picton—for what, too, they knew not yet, and, indeed, at this instant I did not know myself, and nearly laughed outright, for the two of our men who had remained at the table had so well employed their interval of ease as to become very pleasantly drunk, and were listening to my confounded story with all the gravity and seriousness in the world.

“‘Where’s Beamish?’ said Picton. ‘Here, sir,’ said Phil stepping out from the line and touching his cap to the general, who, taking him apart for a few minutes, spoke to him with great animation. We did not know what he said; but before five minutes were over, there was Phil with three companies of light-bobs drawn up at our left; their muskets at the charge, they set off at a round trot down the little steep which closed our flank. We had not much time to follow their movements, for our own amusement began soon; but I well remember, after repelling the French attack, and standing in square against two heavy charges of cuirassiers, the first thing I saw where the French battery had stood, was Phil Beamish and about a handful of brave fellows, all that remained from the skirmish. He captured two of the enemy’s field-pieces, and was ‘Captain Beamish’ on the day after.”

“Long life to him,” said at least a dozen voices behind and about me, while a general clinking of decanters and smacking of lips betokened that Phil’s health with all the honours was being celebrated. For myself, I was really so engrossed by my narrative, and so excited by the “ponche,” that I saw or heard very little of what was passing around, and have only a kind of dim recollection of being seized by the hand by “Feargus,” who was Beamish’s brother, and who, in the fullness of his heart, would have hugged me to his breast, if I had not opportunely been so overpowered as to fall senseless under the table.

When I first returned to consciousness, I found myself lying exactly where I had fallen. Around me lay heaps of slain—the two of “ours” amongst the number. One of them—I remember he was the adjutant—held in his hand a wax candle (three to the pound). Whether he had himself seized it in the enthusiasm of my narrative of flood and field, or it had been put there by another, I know not, but he certainly cut a droll figure. The room we were in was a small one off the great saloon, and through the half open folding-door I could clearly perceive that the festivities were still continued. The crash of fiddles and French horns, and the tramp of feet, which had lost much of their elasticity since the entertainments began, rang through my ears, mingled with the sounds “down the middle,” “hands across,” “here’s your partner, Captain.” What hour of the night or morning it then was, I could not guess; but certainly the vigor of the party seemed little abated, if I might judge from the specimens before me, and the testimony of a short plethoric gentleman, who stood wiping his bald head, after conducting his partner down twenty-eight couple, and who, turning to his friend, said, “Oh, the distance is nothing, but it is the pace that kills.”

The first evidence I shewed of any return to reason, was a strong anxiety to be at my quarters; but how to get there I knew not. The faint glimmering of sense I possessed told me that “to stand was to fall,” and I was ashamed to go on all-fours, which prudence suggested.

At this moment I remembered I had brought with me my cane, which, from a perhaps pardonable vanity, I was fond of parading. It was a present from the officers of my regiment—many of them, alas, since dead—and had a most splendid gold head, with a stag at the top—the arms of the regiment. This I would not have lost for any consideration I can mention; and this now was gone! I looked around me on every side; I groped beneath the table; I turned the sleeping sots who lay about in no very gentle fashion; but, alas, it was gone. I sprang to my feet and only then remembered how unfit I was to follow up the search, as tables, chairs, lights, and people seemed all rocking and waving before me. However, I succeeded in making my way, through one room into another, sometimes guiding my steps along the walls; and once, as I recollect, seeking the diagonal of a room, I bisected a quadrille with such ill-directed speed, as to run foul of a Cork dandy and his partner who were just performing the “en avant:” but though I saw them lie tumbled in the dust by the shock of my encounter—for I had upset them—I still held on the even tenor of my way. In fact, I had feeling for but one loss; and, still in pursuit of my cane, I reached the hall-door. Now, be it known that the architecture of the Cork Mansion House has but one fault, but that fault is a grand one, and a strong evidence of how unsuited English architects are to provide buildings for a people whose tastes and habits they but imperfectly understand—be it known, then, that the descent from the hall-door to the street was by a flight of twelve stone steps. How I should ever get down these was now my difficulty. If Falstaff deplored “eight yards of uneven ground as being three score and ten miles a foot,” with equal truth did I feel that these twelve awful steps were worse to me than would be M’Gillicuddy Reeks in the day-light, and with a head clear from champagne.

While I yet hesitated, the problem resolved itself; for, gazing down upon the bright gravel, brilliantly lighted by the surrounding lamps, I lost my balance, and came tumbling and rolling from top to bottom, where I fell upon a large mass of some soft substance, to which, in all probability, I owe my life. In a few seconds I recovered my senses, and what was my surprise to find that the downy cushion beneath, snored most audibly! I moved a little to one side, and then discovered that in reality it was nothing less than an alderman of Cork, who, from his position, I concluded had shared the same fate with myself; there he lay, “like a warrior taking his rest,” but not with his “martial cloak around him,” but a much more comfortable and far more costly robe—a scarlet gown of office—with huge velvet cuffs and a great cape of the same material. True courage consists in presence of mind; and here mine came to my aid at once: recollecting the loss I had just sustained, and perceiving that all was still about me, with that right Peninsular maxim, that reprisals are fair in an enemy’s camp, I proceeded to strip the slain; and with some little difficulty—partly, indeed, owing to my unsteadiness on my legs—I succeeded in denuding the worthy alderman, who gave no other sign of life during the operation than an abortive effort to “hip, hip, hurra,” in which I left him, having put on the spoil, and set out on my way the the barrack with as much dignity of manner as I could assume in honour of my costume. And here I may mention (en parenthese) that a more comfortable morning gown no man ever possessed, and in its wide luxuriant folds I revel, while I write these lines.

When I awoke on the following day I had considerable difficulty in tracing the events of the past evening. The great scarlet cloak, however, unravelled much of the mystery, and gradually the whole of my career became clear before me, with the single exception of the episode of Phil Beamish, about which my memory was subsequently refreshed—but I anticipate. Only five appeared that day at mess; and, Lord! What spectres they were!—yellow as guineas; they called for soda water without ceasing, and scarcely spoke a word to each other. It was plain that the corporation of Cork was committing more havoc among us than Corunna or Waterloo, and that if we did not change our quarters, there would be quick promotion in the corps for such as were “seasoned gentlemen.” After a day or two we met again together, and then what adventures were told—each man had his own story to narrate; and from the occurrences detailed, one would have supposed years had been passing, instead of the short hours of an evening party. Mine were indeed among the least remarkable; but I confess that the air of vraisemblance produced by my production of the aldermanic gown gave me the palm above all competitors.

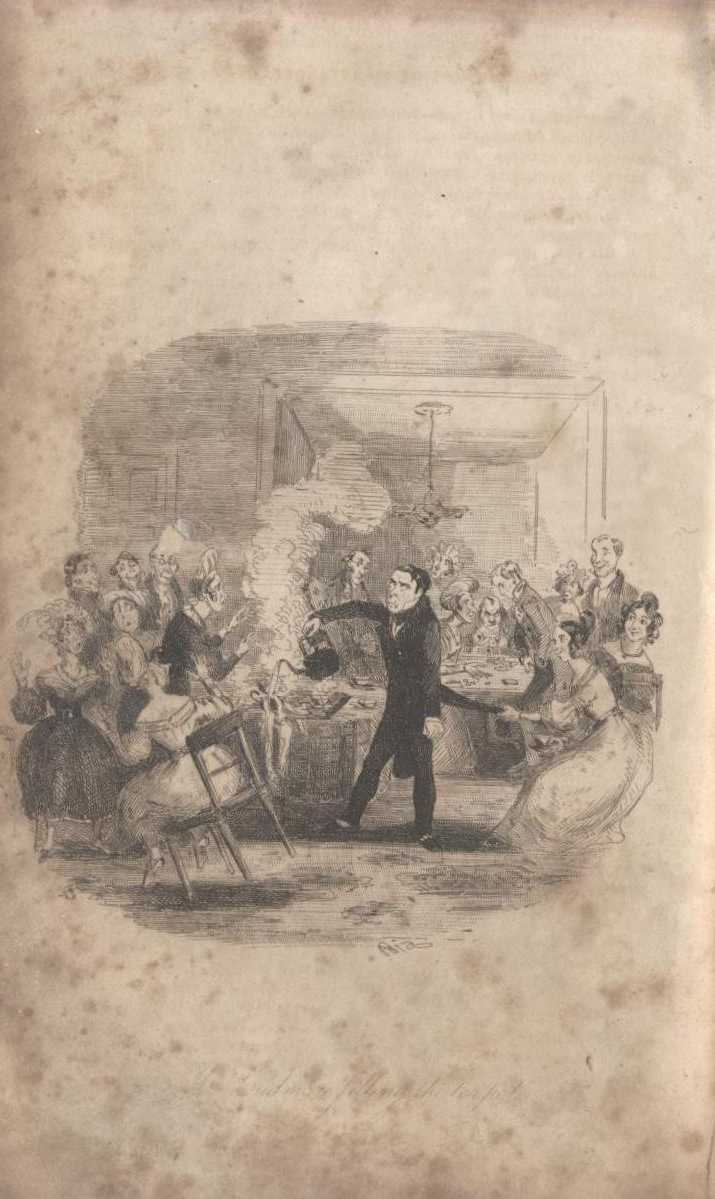

Such was our life in Cork—dining, drinking, dancing, riding steeple chases, pigeon shooting, and tandem driving—filling up any little interval that was found to exist between a late breakfast, and the time to dress for dinner; and here I hope I shall not be accused of a tendency to boasting, while I add, that among all ranks and degrees of men, and women too, there never was a regiment more highly in estimation than the 4_th. We felt the full value of all the attentions we were receiving; and we endeavoured, as best we might, to repay them. We got up Garrison Balls and Garrison Plays, and usually performed one or twice a week during the winter. Here I shone conspicuously; in the morning I was employed painting scenery and arranging the properties; as it grew later, I regulated the lamps, and looked after the foot-lights, mediating occasionally between angry litigants, whose jealousies abound to the full as much, in private theatricals, as in the regular corps dramatique. Then, I was also leader in the orchestra; and had scarcely to speak the prologues. Such are the cares of greatness: to do myself justice, I did not dislike them; though, to be sure, my taste for the drama did cost me a little dear, as will be seen in the sequel.

We were then in the full career of popularity. Our balls pronounced the very pleasantest; our plays far superior to any regular corps that had ever honoured Cork with their talents; when an event occurred which threw a gloom over all our proceedings, and finally put a stop to every project for amusement, we had so completely given ourselves up to. This was no less than the removal of our Lieutenant-Colonel. After thirty years of active service in the regiment he then commanded, his age and infirmities, increased by some severe wounds, demanded ease and repose; he retired from us, bearing along with him the love and regard of every man in the regiment. To the old officers he was endeared by long companionship, and undeviating friendship; to the young, he was in every respect as a father, assisting by his advice, and guiding by his counsel; while to the men, the best estimate of his worth appeared in the fact, that corporeal punishment was unknown in the corps. Such was the man we lost; and it may well be supposed, that his successor, who, or whatever he might be, came under circumstances of no common difficulty amongst us; but, when I tell, that our new Lieutenant-Colonel was in every respect his opposite, it may be believed how little cordiality he met with.

Lieutenant-Colonel Carden—for so I shall call him, although not his real name—had not been a month at quarters, when he proved himself a regular martinet; everlasting drills, continual reports, fatigue parties, and ball practice, and heaven knows what besides, superseded our former morning’s occupation; and, at the end of the time I have metioned, we, who had fought our way from Albuera to Waterloo, under some of the severest generals of division, were pronounced a most disorderly and ill-disciplined regiment, by a Colonel, who had never seen a shot fired but at a review in Hounslow, or a sham-battle in the Fifteen Acres. The winter was now drawing to a close—already some little touch of spring was appearing; as our last play for the season was announced, every effort to close with some little additional effort was made; and each performer in the expected piece was nerving himself for an effort beyond his wont. The Colonel had most unequivocally condemned these plays; but that mattered not; they came not within his jurisdiction; and we took no notice of his displeasure, further than sending him tickets, which were as immediately returned as received. From being the chief offender, I had become particularly obnoxious; and he had upon more than one occasion expressed his desire for an opportunity to visit me with his vengeance; but being aware of his kind intentions towards me, I took particular care to let no such opportunity occur.

On the morning in question, then, I had scarcely left my quarters, when

one of my brother officers informed me that the Colonel had made a great

uproar, that one of the bills of the play had been put up on his door—which,

with his avowed dislike to such representations, he considered as intended

to insult him: he added, too, that the Colonel attributed it to me. In

this, however, he was wrong—and, to this hour, I never knew who did

it. I had little time, and still less inclination, to meditate upon the

Colonel’s wrath—the theatre had all my thoughts; and indeed it was a

day of no common exertion, for our amusements were to conclude with a

grand supper on the stage, to which all the elite of Cork were invited.

Wherever I went through the city—and many were my peregrinations—the

great placard of the play stared me in the fact; and every gate and

shuttered window in Cork, proclaimed,

As evening drew near, my cares and occupations were redoubled. My Iago I had fears for—‘tis true he was an admirable Lord Grizzle in Tom Thumb—but then—then I had to paint the whole company, and bear all their abuse besides, for not making some of the most ill-looking wretches, perfect Apollos; but, last of all, I was sent for, at a quarter to seven, to lace Desdemona’s stays. Start not, gentle reader—my fair Desdemona—she “who might lie by an emperor’s side, and command him tasks”—was no other than the senior lieutenant of the regiment, and who was a great a votary of the jolly god as honest Cassio himself. But I must hasten on—I cannot delay to recount our successes in detail. Let it suffice to say, that, by universal consent, I was preferred to Kean; and the only fault the most critical observer could find to the representative of Desdemona, was a rather unlady-like fondness for snuff. But, whatever little demerits our acting might have displayed, were speedily forgotten in a champagne supper. There I took the head of the table; and, in the costume of the noble Moor, toasted, made speeches, returned thanks, and sung songs, till I might have exclaimed with Othello himself, “Chaos was come again;”—and I believe I owe my ever reaching the barrack that night to the kind offices of Desdemona, who carried me the greater part of the way on her back.

The first waking thoughts of him who has indulged over-night, was not among the most blissful of existence, and certainly the pleasure is not increased by the consciousness that he is called on to the discharge of duties to which a fevered pulse and throbbing temples are but ill-suited. My sleep was suddenly broken in upon the morning after the play, but a “row-dow-dow” beat beneath my window. I jumped hastily from my bed, and looked out, and there, to my horror, perceived the regiment under arms. It was one of our confounded colonel’s morning drills; and there he stood himself with the poor adjutant, who had been up all night, shivering beside him. Some two or three of the officers had descended; and the drum was now summoning the others as it beat round the barrack-square. I saw there was not a moment to lose, and proceeded to dress with all despatch; but, to my misery, I discovered every where nothing but theatrical robes and decorations—there lay a splendid turban, here a pair of buskins—a spangled jacket glittered on one table, and a jewelled scimitar on the other. At last I detected my “regimental small-clothes,” Most ignominiously thrust into a corner, in my ardour for my Moorish robes the preceding evening.

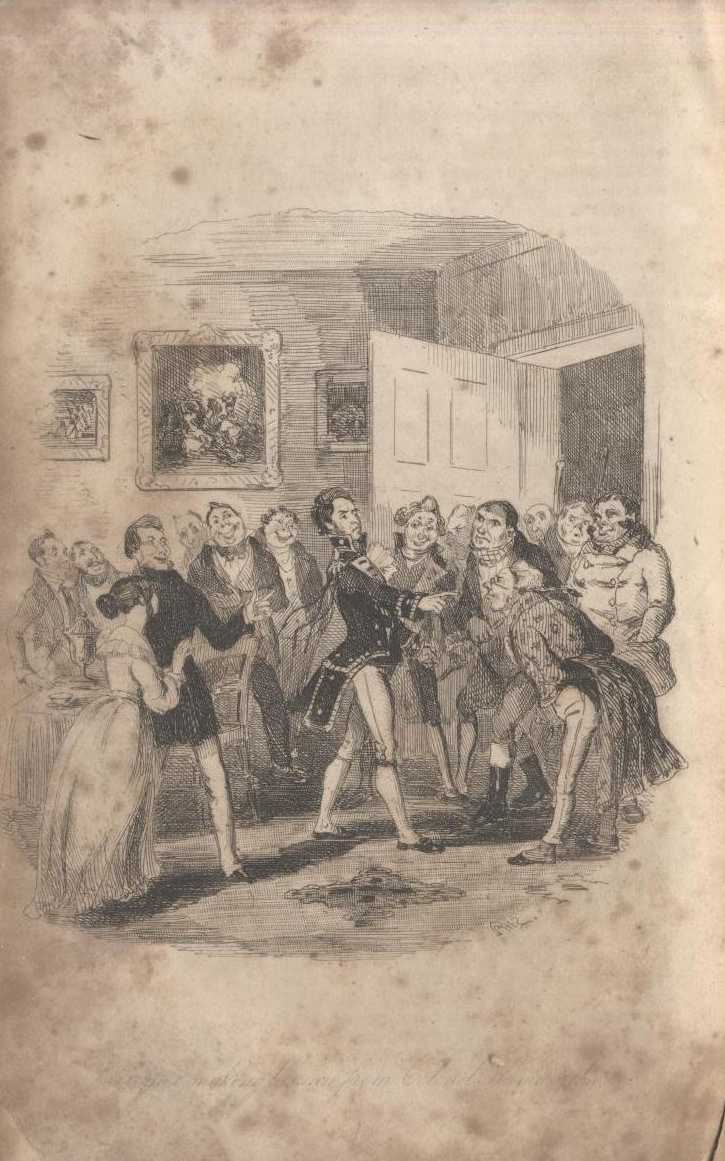

I dressed myself with the speed of lightning; but as I proceeded in my occupation-guess my annoyance to find that the toilet-table and glass, ay, and even the basin-stand, had been removed to the dressing-room of the theatre; and my servant, I suppose, following his master’s example, was too tipsy to remember to bring them back; so that I was unable to procure the luxury of cold water—for now not a moment more remained—the drum had ceased, and the men had all fallen in. Hastily drawing on my coat, I put on my shako, and buckling on my belt as dandy-like as might be, hurried down the stairs to the barrack-yard. By the time I got down, the men were all drawn up in line along the square; while the adjutant was proceeding to examine their accoutrements, as he passed down. The colonel and the officers were standing in a group, but no conversing. The anger of the commanding officer appeared still to continue, and there was a dead silence maintained on both sides. To reach the spot where they stood, I had to pass along part of the line. In doing so, how shall I convey my amazement at the faces that met me—a general titter ran along the entire rank, which not even their fears for consequences seemed able to repress—for an effort, on the part of many, to stifle the laugh, only ended in a still louder burst of merriment. I looked to the far side of the yard for an explanation, but there was nothing there to account for it. I now crossed over to where the officers were standing, determining in my own mind to investigate the occurrence thoroughly, when free from the presence of the colonel, to whom any representation of ill conduct always brought a punishment far exceeding the merits of the case.

Scarcely had I formed this resolve, when I reached the group of officers; but the moment I came near, one general roar of laughter saluted me,—the like of which I never before heard—I looked down at my costume, expecting to discover that, in my hurry to dress, I had put on some of the garments of Othello—No: all was perfectly correct. I waited for a moment, till the first burst of their merriment over, I should obtain a clue to the jest. But their mirth appeared to increase. Indeed poor G——, the senior major, one of the gravest men in Europe, laughed till the tears ran down his cheeks; and such was the effect upon me, that I was induced to laugh too—as men will sometimes, from the infectious nature of that strange emotion; but, no sooner did I do this, than their fun knew no bounds, and some almost screamed aloud, in the excess of their merriment; just at this instant the Colonel, who had been examining some of the men, approached our group, advancing with an air of evident displeasure, as the shouts of loud laughter continued. As he came up, I turned hastily round, and touching my cap, wished him good morning. Never shall I forget the look he gave me. If a glance could have annihilated any man, his would have finished me. For a moment his face became purple with rage, his eye was almost hid beneath his bent brow, and he absolutely shook with passion.

“Go, Sir,” said he at length, as soon as he was able to find utterance for his words; “Go, sir, to your quarters; and before you leave them, a court-martial shall decide, if such continued insult to your commanding officer, warrants your name being in the Army List.”

“What the devil can all this mean?” I said, in a half-whisper, turning to the others. But there they stood, their handkerchiefs to their mouths, and evidently choking with suppressed laughter.

“May I beg, Colonel C_____,” said I——

“To your quarters, sir,” roared the little man, in the voice of a lion. And with a haughty wave of his hand, prevented all further attempt on my part to seek explanation.

“They’re all mad, every man of them,” I muttered, as I betook byself slowly back to my rooms, amid the same evidences of mirth my first appearance had excited—which even the Colonel’s presence, feared as he was, could not entirely subdue.

With the air of a martyr I trod heavily up the stairs, and entered my quarters, meditating within myself, awful schemes for vengeance, on the now open tyranny of my Colonel; upon whom, I too, in my honest rectitude of heart, vowed to have “a court-martial.” I threw myself upon a chair, and endeavoured to recollect what circumstance of the past evening could have possibly suggested all the mirth in which both officers and men seemed to participate equally; but nothing could I remember, capable of solving the mystery,—surely the cruel wrongs of the manly Othello were no laughter-moving subject.

I rang the bell hastily for my servant. The door opened.

“Stubbes,” said I, “are you aware”——

I had only got so far in my question, when my servant, one of the most discreet of men, put on a broad grin, and turned away towards the door to hide his face.

“What the devil does this mean?” said I, stamping with passion; “he is as bad as the rest. Stubbes,” and this I spoke with the most grave and severe tone, “what is the meaning of the insolence?”

“Oh, sir,” said the man; “Oh, sir, surely you did not appear on parade with that face?” and then he burst into a fit of the most uncontrollable laughter.

Like lightning a horrid doubt shot across my mind. I sprung over to the dressing-glass, which had been replaced, and oh: horror of horrors! There I stood as black as the king of Ashantee. The cursed dye which I had put on for Othello, I had never washed off,—and there with a huge bear-skin shako, and a pair of black, bushy whiskers, shone my huge, black, and polished visage, glowering at itself in the looking-glass.

My first impulse, after amazement had a little subsided, was to laugh immoderately; in this I was joined by Stubbes, who, feeling that his mirth was participated in, gave full vent to his risibility. And, indeed, as I stood before the glass, grinning from ear to ear, I felt very little surprise that my joining in the laughter of my brother officers, a short time before, had caused an increase of their merriment. I threw myself upon a sofa, and absolutely laughed till my sides ached, when, the door opening, the adjutant made his appearance. He looked for a moment at me, then at Stubbes, and then burst out himself, as loud as either of us. When he had at length recovered himself, he wiped his face with his handkerchief, and said, with a tone of much gravity:—

“But, my dear Lorrequer, this will be a serious—a devilish serious affair. You know what kind of man Colonel C____ is; and you are aware, too, you are not one of his prime favourites. He is firmly convinced that you intended to insult him, and nothing will convince him to the contrary. We told him how it must have occurred, but he will listen to no explanation.”

I thought for one second before I replied, my mind, with the practised rapidity of an old campaigner, took in all the pros and cons of the case; I saw at a glance, it were better to brave the anger of the Colonel, come in what shape it might, than be the laughing-stock of the mess for life, and with a face of the greatest gravity and self-possession, said,

“Well, adjutant, the Colonel is right. It was no mistake! You know I sent him tickets yesterday for the theatre. Well, he returned them; this did not annoy me, but on one account, I had made a wager with Alderman Gullable, that the Colonel should see me in Othello—what was to be done? Don’t you see, now, there was only one course, and I took it, old boy, and have won my bet!”

“And lost your commission for a dozen of champagne, I suppose,” said the adjutant.

“Never mind, my dear fellow,” I repled; “I shall get out of this scrape, as I have done many others.”

“But what do you intend doing?”

“Oh, as to that,” said I, “I shall, of course, wait on the Colonel immediately; pretend to him that it was a mere blunder, from the inattention of my servant—hand over Stubbes to the powers that punish, (here the poor fellow winced a little,) and make my peace as well as I can. But, adjutant, mind,” said I, “and give the real version to all our fellows, and tell them to make it public as much as they please.”

“Never fear,” said he, as he left the room still laughing, “they shall all know the true story; but I wish with all my heart you were well out of it.”

I now lost no time in making my toilet, and presented myself at the Colonel’s quarters. It is no pleasure for me to recount these passages in my life, in which I have had to hear the “proud man’s contumely.” I shall therefore merely observe, that after a very long interview, the Colonel accepted my apologies, and we parted.

Before a week elapsed, the story had gone far and near; every dinner-table in Cork had laughed at it. As for me, I attained immortal honour for my tact and courage. Poor Gullable readily agreed to favour the story, and gave us a dinner as the lost wager, and the Colonel was so unmercifully quizzed on the subject, and such broad allusions to his being humbugged were given in the Cork papers, that he was obliged to negociate a change of quarters with another regiment, to get out of the continual jesting, and in less than a month we marched to Limerick, to relieve, as it was reported, the 9th, ordered for foreign service, but, in reality, only to relieve Lieut.-Colonel C____, quizzed beyond endurance.

However, if the Colonel had seemed to forgive, he did not forget, for the very second week after our arrival in Limerick, I received one morning at my breakfast-table, the following brief note from our adjutant:—

“My Dear Lorrequer—The Colonel has received orders to despatch two companies to some remote part of the county Clare; as you have ‘done the state some service,’ you are selected for the beautiful town of Kilrush, where, to use the eulogistic language of the geography books, ‘there is a good harbour, and a market plentifully supplied with fish.’ I have just heard of the kind intention in store for you, and lose no time in letting you know.

“God give you a good deliverance from the ‘garcons lances,’ as the Moniteur calls the Whiteboys, and believe me ever your’s, Charles Curzon.”

I had scarcely twice read over the adjutant’s epistle, when I received an official notification from the Colonel, directing me to proceed to Kilrush, then and there to afford all aid and assistance in suppressing illicit distillation, when called on for that purpose; and other similar duties too agreeable to recapitulate. Alas! Alas! Othello’s occupation: was indeed gone! The next morning at sun-rise saw me on my march, with what appearance of gaiety I could muster, but in reality very much chopfallen at my banishment, and invoking sundry things upon the devoted head of the Colonel, which he would by no means consider as “blessings.”

How short-sighted are we mortals, whether enjoying all the pump and state of royalty, or marching like myself at the head of a company of his Majesty’s 4_th.

Little, indeed, did I anticipate that the Siberia to which I fancied I was condemned should turn out the happiest quarters my fate ever threw me into. But this, including as it does, one of the most important events of my life, I reserve for another chapter.—

“What is that place called, Sergeant?”—“Bunratty Castle, sir,”

“Where do we breakfast?”—“At Clare Island, sir.”

“March away, boys!”

For a week after my arrival at Kilrush, my life was one of the most dreary monotony. The rain, which had begun to fall as I left Limerick, continued to descend in torrents, and I found myself a close prisoner in the sanded parlour of “mine inn.” At no time would such “durance vile” have been agreeable; but now, when I contrasted it with all I had left behind at head quarters, it was absolutely maddening. The pleasant lounge in the morning, the social mess, and the agreeable evening party, were all exchanged for a short promenade of fourteen feet in one direction, and twelve in the other, such being the accurate measurement of my “salle a manger.” A chicken, with legs as blue as a Highlander’s in winter, for my dinner; and the hours that all Christian mankind were devoting to pleasant intercourse, and agreeable chit-chat, spent in beating that dead-march to time, “the Devil’s Tattoo,” upon my ricketty table, and forming, between whiles, sundry valorous resolutions to reform my life, and “eschew sack and loose company.”

My front-window looked out upon a long, straggling, ill-paved street, with its due proportion of mud-heaps, and duck pools; the houses on either side were, for the most part, dingy-looking edifices, with half-doors, and such pretension to being shops as a quart of meal, or salt, displayed in the window, confers; or sometimes two tobacco-pipes, placed “saltier-wise,” would appear the only vendible article in the establishment. A more wretched, gloomy-looking picture of woe-begone poverty, I never beheld.

If I turned for consolation to the back of the house, my eyes fell upon

the dirty yard of a dirty inn; the half-thatched cow-shed, where two

famished animals mourned their hard fate,—“chewing the cud of sweet

and bitter fancy;” the chaise, the yellow post-chaise, once the pride and

glory of the establishment, now stood reduced from its wheels, and

ignominiously degraded to a hen-house; on the grass-grown roof a cock had

taken his stand, with an air of protective patronage to the feathered

inhabitants beneath:

“To what base uses must we come at last.”

That chaise, which once had conveyed the blooming bride, all blushes and tenderness, and the happy groom, on their honeymoon visit to Ballybunion and its romantic caves, or to the gigantic cliffs and sea-girt shores of Moher—or with more steady pace and becoming gravity had borne along the “going judge of assize,”—was now become a lying-in hospital for fowl, and a nursery for chickens. Fallen as I was myself from my high estate, it afforded me a species of malicious satisfaction to contemplate these sad reverses of fortune; and I verily believe—for on such slight foundation our greatest resolves are built—that if the rain had continued a week longer, I should have become a misanthropist for life. I made many inquiries from my landlady as to the society of the place, but the answers I received only led to greater despondence. My predecessor here, it seemed, had been an officer of a veteran battalion, with a wife, and that amount of children which is algebraically expressed by an X (meaning an unknown quantity). He, good man, in his two years’ sojourn here, had been much more solicitous about his own affairs, than making acquaintance with his neighbours; and at last, the few persons who had been in the habit of calling on “the officer,” gave up the practice; and as there were no young ladies to refresh Pa’s memory on the matter, they soon forgot completely that such a person existed—and to this happy oblivion I, Harry Lorrequer, succeeded, and was thus left without benefit of clergy to the tender mercies of Mrs. Healy of the Burton arms.

As during the inundation which deluged the whole country around I was unable to stir from the house, I enjoyed abundant opportunity of cultivating the acquaintance of my hostess, and it is but fair that my reader, who has journeyed so far with me, should have an introduction.

Mrs. Healy, the sole proprietor of the “Burton Arms,” was of some five and

fifty—“or by’r lady,” three score years, of a rubicund and hale

complexion; and though her short neck and corpulent figure might have set

her down as “doubly hazardous,” she looked a good life for many years to

come. In height and breadth she most nearly resembled a sugar-hogshead,

whose rolling, pitching motion, when trundled along on edge, she emulated

in her gait. To the ungainliness of her figure her mode of dressing not a

little contributed. She usually wore a thick linsey-wolsey gown, with

enormous pockets on either side, and, like Nora Creina’s, it certainly

inflicted no undue restrictions upon her charms, but left “Every beauty

free,

To sink or swell as heaven pleases."

Her feet—ye gods! Such feet—were apparelled in listing slippers, over which the upholstery of her ancles descended, and completely relieved the mind of the spectator as to the superincumbent weight being disproportioned to the support; I remember well my first impression on seeing those feet and ancles reposing upon a straw footstool, while she took her afternoon dose, and I wondered within myself if elephants were liable to the gout. There are few countenances in the world, that if wishing to convey an idea of, we cannot refer to some well-known standard; and thus nothing is more common than to hear comparisons with “Vulcan—Venus—Nicodemus,” and the like; but in the present case, I am totally at a loss for any thing resembling the face of the worth Mrs. Healy, except it be, perhaps, that most ancient and sour visage we used to see upon old circular iron rappers formerly—they make none of them now—the only difference being, that Mrs. Healy’s nose had no ring through it; I am almost tempted to add, “more’s the pity.”

Such was she in “the flesh;” would that I could say, she was more fascinating in the “spirit!” but alas, truth, from which I never may depart in these “my confessions,” constrains me to acknowledge the reverse. Most persons in this miserable world of ours, have some prevailing, predominating characteristic, which usually gives the tone and colour to all their thoughts and actions, forming what we denominate temperament; this we see actuating them, now more, now less; but rarely, however, is this great spring of action without its moments of repose. Not so with her of whom I have been speaking. She had but one passion—but, like Aaron’s rod, it had a most consuming tendency—and that was to scold, and abuse, all whom hard fate had brought within the unfortunate limits of her tyranny. The English language, comprehensive as it is, afforded not epithets strong enough for her wrath, and she sought among the more classic beauties of her native Irish, such additional ones as served her need, and with this holy alliance of tongues, she had been for years long, the dread and terror of the entire village.

“The dawning of morn, the day-light sinking,” ay, and even the “night’s dull hours,” it was said, too, found her labouring in her congenial occupation; and while thus she continued to “scold and grow fat,” her inn, once a popular and frequented one, became gradually less and less frequented, and the dragon of the Rhine-fells did not more effectually lay waste the territory about him, than did the evil influence of her tongue spread desolation and ruin around her. Her inn, at the time of my visit, had not been troubled with even a passing traveller for many months; and, indeed, if I had any, even the least foreknowledge of the character of my hostess, its privacy should have still remained uninvaded for some time longer.

I had not been many hours installed, when I got a specimen of her powers; and before the first week was over, so constant and unremitting were her labours in this way, that I have upon the occasion of a slight lull in the storm, occasioned by her falling asleep, actually left my room to inquire if anything had gone wrong, in the same was as the miller is said to awake, if the mill stops. I trust I have said enough, to move the reader’s pity and compassion for my situation—one more miserable it is difficult to conceive. It may be though that much might be done by management, and that a slight exercise of the favourite Whig plan of concilliation, might avail. Nothing of the kind. She was proof against all such arts; and what was still worse, there was no subject, no possible circumstance, no matter, past, present, or to come, that she could not wind by her diabolical ingenuity, into some cause of offence; and then came the quick transition to instant punishment. Thus, my apparently harmless inquiry as to the society of the neighbourhood, suggested to her—a wish on my part to make acquaintance—therefore to dine out—therefore not to dine at home—consequently to escape paying half-a-crown and devouring a chicken—therefore to defraud her, and behave, as she would herself observe, “like a beggarly scullion, with his four shillings a day, setting up for a gentleman,”

By a quiet and Job-like endurance of all manner of taunting suspicions, and unmerited sarcasms, to which I daily became more reconciled, I absolutely rose into something like favour; and before the first month of my banishment expired, had got the length of an invitation to tea, in her own snuggery—an honour never known to be bestowed on any before, with the exception of Father Malachi Brennan, her ghostly adviser; and even he, it is said, never ventured on such an approximation to intimacy, until he was, in Kilrush phrase, “half screwed,” thereby meaning more than half tipsy. From time to time thus, I learned from my hostess such particulars of the country and its inhabitants as I was desirous of hearing; and among other matters, she gave me an account of the great landed proprietor himself, Lord Callonby, who was daily expected at his seat, within some miles of Kilrush, at the same time assuring me that I need not be looking so “pleased and curling out my whiskers;” “that they’d never take the trouble of asking even the name of me.” This, though neither very courteous, nor altogether flattering to listen to, was no more than I had already learned from some brother officers who knew this quarter, and who informed me that the Earl of Callonby, though only visiting his Irish estates every three or four years, never took the slightest notice of any of the military in his neighbourhood; nor, indeed did he mix with the country gentry, confining himself to his own family, or the guests, who usually accompanied him from England, and remained during his few weeks’ stay. My impression of his lordship was therefore not calculated to cheer my solitude by any prospect of his rendering it lighter.

The Earl’s family consisted of her ladyship, an only son, nearly of age, and two daughters; the eldest, Lady Jane, had the reputation of being extremely beautiful; and I remembered when she came out in London, only the year before, hearing nothing but praises of the grace and elegance of her manner, united to the most classic beauty of her face and figure. The second daughter was some years younger, and said to be also very handsome; but as yet she had not been brought into society. Of the son, Lord Kilkee, I only heard that he had been a very gay fellow at Oxford, where he was much liked, and although not particularly studious, had given evidence of talent.

Such were the few particulars I obtained of my neighbours, and thus little did I know of those who were so soon to exercise a most important influence upon my future life.

After some weeks’ close confinement, which, judging from my feelings alone, I should have counted as many years, I eagerly seized the opportunity of the first glimpse of sunshine to make a short excursion along the coast; I started early in the morning, and after a long stroll along the bold headlands of Kilkee, was returning late in the evening to my lodgings. My path lay across a wild, bleak moor, dotted with low clumps of furze, and not presenting on any side the least trace of habitation. In wading through the tangled bushes, my dog “Mouche” started a hare; and after a run “sharp, short, and decisive,” killed it at the bottom of a little glen some hundred yards off.

I was just patting my dog, and examining the prize, when I heard a crackling among the low bushes near me; and on looking up, perceived, about twenty paces distant, a short, thick-set man, whose fustian jacket and leathern gaiters at once pronounced him the gamekeeper; he stood leaning upon his gun, quietly awaiting, as it seemed, for any movement on my part, before he interfered. With one glance I detected how matters stood, and immediately adopting my usual policy of “taking the bull by the horns,” called out, in a tone of very sufficient authority,

“I say, my man, are you his lordship’s gamekeeper?”

Taking off his hat, the man approached me, and very respectfully informed me that he was.

“Well then,” said I, “present this hare to his lordship with my respects; here is my card, and say I shall be most happy to wait on him in the morning, and explain the circumstance.”

The man took the card, and seemed for some moments undecided how to act; he seemed to think that probably he might be ill-treating a friend of his lordship’s if he refused; and on the other hand might be merely “jockeyed” by some bold-faced poacher. Meanwhile I whistled my dog close up, and humming an air, with great appearance of indifference, stepped out homeward. By this piece of presence of mind I saved poor “Mouche;” for I saw at a glance, that, with true gamekeeper’s law, he had been destined to death the moment he had committed the offence.

The following morning, as I sat at breakfast, meditating upon the events of the preceding day, and not exactly determined how to act, whether to write to his lordship explaining how the matter occurred, or call personally, a loud rattling on the pavement drew me to the window. As the house stood at the end of a street, I could not see in the direction the noise came; but as I listened, a very handsome tandem turned the corner of the narrow street, and came along towards the hotel at a long, sling trot; the horses were dark chestnuts, well matched, and shewing a deal of blood. The carriage was a dark drab, with black wheels; the harness all of the same colour. The whole turn-out—and I was an amateur of that sort of thing—was perfect; the driver, for I come to him last, as he was the last I looked at, was a fashionable looking young fellow, plainly, but knowingly, dressed, and evidently handling the “ribbon,” like an experienced whip.

After bringing his nags up to the inn door in very pretty style, he gave the reins to his servant, and got down. Before I was well aware of it, the door of my room opened, and the gentleman entered with a certain easy air of good breeding, and saying,

“Mr. Lorrequer, I presume—” introduced himself as Lord Kilkee.

I immediately opened the conversation by an apology for my dog’s misconduct on the day before, and assured his lordship that I knew the value of a hare in a hunting country, and was really sorry for the circumstance.

“Then I must say,” replied his lordship, “Mr. Lorrequer is the only person who regrets the matter; for had it not been for this, it is more than probable we should never have known we were so near neighbours; in fact, nothing could equal our amazement at hearing you were playing the ‘Solitaire’ down here. You must have found it dreadfully heavy, ‘and have thought us downright savages.’ But then I must explain to you, that my father has made some ‘rule absolute’ about visiting when down here. And though I know you’ll not consider it a compliment, yet I can assure you there is not another man I know of he would pay attention to, but yourself. He made two efforts to get here this morning, but the gout ‘would not be denied,’ and so he deputed a most inferior ‘diplomate;’ and now will you let me return with some character from my first mission, and inform my friends that you will dine with us to-day at seven—a mere family party; but make your arrangements to stop all night and to-morrow: we shall find some work for my friend there on the hearth; what do you call him, Mr. Lorrequer?”

“‘Mouche’—come here, ‘Mouche.’”

“Ah ‘Mouche,’ come here, my fine fellow—a splendid dog, indeed; very tall for a thorough-bred; and now you’ll not forget, seven, ‘temps militaire,’ and so, sans adieu.”

And with these words his lordship shook me heartily by the hand; and before two minutes had elapsed, had wrapped his box-coat once more across him, and was round the corner.

I looked for a few moments on the again silent street, and was almost tempted to believe I was in a dream, so rapidly had the preceding moments passed over; and so surprised was I to find that the proud Earl of Callonby, who never did the “civil thing” any where, should think proper to pay attention to a poor sub in a marching regiment, whose only claim on his acquaintance was the suspicion of poaching on his manor. I repeated over and over all his lordship’s most polite speeches, trying to solve the mystery of them; but in vain: a thousand explanations occurred, but none of them I felt at all satisfactory; that there was some mystery somewhere, I had no doubt; for I remarked all through that Lord Kilkee laid some stress upon my identity, and even seemed surprised at my being is such banishment. “Oh,” thought I at last, “his lordship is about to get up private theatricals, and has seen my Captain Absolute, or perhaps my Hamlet”—I could not say “Othello” even to myself—“and is anxious to get ‘such unrivalled talent’ even ‘for one night only.’”

After many guesses this seemed the nearest I could think of; and by the time I had finished my dressing for dinner, it was quite clear to me I had solved all the secret of his lordship’s attentions.

The road to “Callonby” was beautiful beyond any thing I had ever seen in Ireland. For upwards of two miles it led along the margin of the lofty cliffs of Moher, now jutting out into bold promontories, and again retreating, and forming small bays and mimic harbours, into which the heavy swell of the broad Atlantic was rolling its deep blue tide. The evening was perfectly calm, and at a little distance from the shore the surface of the sea was without a ripple. The only sound breaking the solemn stillness of the hour, was the heavy plash of the waves, as in minute peals they rolled in upon the pebbly beach, and brought back with them at each retreat, some of the larger and smoother stones, whose noise, as they fell back into old ocean’s bed, mingled with the din of the breaking surf. In one of the many little bays I passed, lay three or four fishing smacks. The sails were drying, and flapped lazily against the mast. I could see the figures of the men as they passed backwards and forwards upon the decks, and although the height was nearly eight hundred feet, could hear their voices quite distinctly. Upon the golden strand, which was still marked with a deeper tint, where the tide had washed, stood a little white cottage of some fisherman—at least, so the net before the door bespoke it. Around it, stood some children, whose merry voices and laughing tones sometimes reached me where I was standing. I could not but think, as I looked down from my lofty eyrie, upon that little group of boats, and that lone hut, how much of the “world” to the humble dweller beneath, lay in that secluded and narrow bay. There, the deep sea, where their days were passed in “storm or sunshine,”—there, the humble home, where at night they rested, and around whose hearth lay all their cares and all their joys. How far, how very far removed from the busy haunts of men, and all the struggles and contentions of the ambitious world; and yet, how short-sighted to suppose that even they had not their griefs and sorrows, and that their humble lot was devoid of the inheritance of those woes, which all are heirs to.

I turned reluctantly, from the sea-shore to enter the gate of the park, and my path in a few moments was as completely screened from all prospect of the sea, as though it had lain miles inland. An avenue of tall and ancient lime trees, so dense in their shadows as nearly to conceal the road beneath, led for above a mile through a beautiful lawn, whose surface, gently undulating, and studded with young clumps, was dotted over with sheep. At length, descending by a very steep road, I reached a beautiful little stream, over which a rustic bridge was thrown. As I looked down upon the rippling stream beneath, on the surface of which the dusky evening flies were dipping, I made a resolve, if I prospered in his lordship’s good graces, to devote a day to the “angle” there, before I left the country. It was now growing late, and remember Lord Kilkee’s intimation of “sharp seven,” I threw my reins over my cob, “Sir Roger’s” neck, (for I had hitherto been walking,) and cantered up the steep hill before me. When I reached the top, I found myself upon a broad table land, encircled by old and well-grown timber, and at a distance, most tastefully half concealed by ornamental planting, I could catch some glimpse of Callonby. Before, however, I had time to look about me, I heard the tramp of horses’ feet behind, and in another moment two ladies dashed up the steep behind, and came towards me, at a smart gallop, followed by a groom, who, neither himself nor his horse, seemed to relish the pace of his fair mistresses. I moved off the road into the grass to permit them to pass; but no sooner had they got abreast of me, than Sir Roger, anxious for a fair start, flung up both heels at once, pricked up his ears, and with a plunge that very nearly threw me from the saddle, set off at top speed. My first thought was for the ladies beside me, and, to my utter horror, I now saw them coming along in full gallop; their horses had got off the road, and were, to my thinking, become quite unmanageable. I endeavoured to pull up, but all in vain. Sir Roger had got the bit between his teeth, a favourite trick of his, and I was perfectly powerless to hold him by this time, they being mounted on thoroughbreds, got a full neck before me, and the pace was now tremendous, on we all came, each horse at his utmost stretch; they were evidently gaining from the better stride of their cattle, and will it be believed, or shall I venture to acknowledge it in these my confessions, that I, who a moment before, would have given my best chance of promotion, to be able to pull in my horse, would now have “pledged my dukedom” to be able to give Sir Roger one cut of the whip unobserved. I leave it to the wise to decipher the rationale, but such is the fact. It was complete steeple-chasing, and my blood was up.

On we came, and I now perceived that about two hundred yards before me stood an iron gate and piers, without any hedge or wall on either side; before I could conjecture the meaning of so strange a thing in the midst of a large lawn, I saw the foremost horse, now two or three lengths before the other, still in advance of me, take two or three short strides, and fly about eight feet over a sunk fence—the second followed in the same style, the riders sitting as steadily as in the gallop. It was now my turn, and I confess, as I neared the dyke, I heartily wished myself well over it, for the very possibility of a “mistake” was maddening. Sir Roger came on at a slapping pace, and when within two yards of the brink, rose to it, and cleared it like a deer. By the time I had accomplished this feat, not the less to my satisfaction, that both ladies had turned in the saddles to watch me, they were already far in advance; they held on still at the same pace, round a small copse which concealed them an instant from my view, and which, when I passed, I perceived that they had just reached the hall door, and were dismounting.

On the steps stood a tall, elderly-looking, gentleman-like person, who I rightly conjectured was his lordship. I heard him laughing heartily as I came up. I at last succeeded in getting Sir Roger to a canter, and when about twenty yards from where the group were standing, sprung off, and hastened up to make my apologies as I best might, for my unfortunate runaway. I was fortunately spared this awkwardness of an explanation, for his lordship, approaching me with his hand extended, said—

“Mr. Lorrequer is most welcome at Callonby. I cannot be mistaken, I am sure—I have the pleasure of addressing the nephew of my old friend, Sir Guy Lorrequer of Elton. I am indeed most happy to see you, and not the less so, that you are safe and sound, which, five minutes since, I assure you I had my fears for—”

Before I could assure his lordship that my fears were all for my competitors in the race—for such in reality they were—he introduced me to the two ladies, who were still standing beside him—“Lady Jane Callonby; Mr. Lorrequer; Lady Catherine.”

“Which of you, young ladies, may I ask, planned this escapade, for I see by your looks, it was no accident?”

“I think, papa,” said Lady Jane, “you must question Mr. Lorrequer on that head; he certainly started first.”

“I confess, indeed,” said I, “such was the case.”

“Well, you must confess, too, you were distanced,” said Lady Jane, at the same time, most terribly provoked, to be quizzed on such a matter; that I, a steeple-chase horseman of the first water, should be twitted by a couple of young ladies, on the score of a most manly exercise. “But come,” said his lordship, “the first bell has rung long since, and I am longing to ask Mr. Lorrequer all about my old college friend of forty years ago. So, ladies, hasten your toilet, I beseech you.”

With these words, his lordship, taking my arm, led me into the drawing-room, where we had not been many minutes till we were joined by her ladyship, a tall stately handsome woman, of a certain age; resolutely bent upon being both young and beautiful, in spite of time and wrinkles; her reception of me, though not possessing the frankness of his lordship, was still very polite, and intended to be even gracious. I now found by the reiterated inquiries for my old uncle, Sir Guy, that he it was, and not Hamlet, to whom I owed my present notice, and I must include it among my confessions, that it was about the first advantage I ever derived from the relationship. After half an hour’s agreeable chatting, the ladies entered, and then I had time to remark the extreme beauty of their appearance; they were both wonderfully like, and except that Lady Jane was taller and more womanly, it would have been almost impossible to discriminate between them.

Lady Jane Callonby was then about twenty years of age, rather above the middle size, and slightly disposed towards embonpoint; her eye was of the deepest and most liquid blue, and rendered apparently darker, by long lashes of the blackest jet—for such was the colour of her hair; her nose slightly, but slightly, deviated from the straightness of the Greek, and her upper lip was faultless, as were her mouth and chin; the whole lower part of the face, from the perfect “chiselling,” and from the character of her head, had certainly a great air of hauteur, but the extreme melting softness of her eyes took from this, and when she spoke, there was a quiet earnestness in her mild and musical voice, that disarmed you at once of connecting the idea of self with the speaker; the word “fascinating,” more than any other I know of, conveys the effect of her appearance, and to produce it, she had more than any other woman I ever met, that wonderful gift, the “l’art de plaire.”

I was roused from my perhaps too earnest, because unconscious gaze, at the lovely figure before me, by his Lordship saying, “Mr. Lorrequer, her Ladyship is waiting for you.” I accordingly bowed, and, offering my arm, led her into the dinner-room. And here I draw rein for the present, reserving for my next chapter—My Adventure at Callonby.

My first evening at Callonby passed off as nearly all first evenings do every where. His lordship was most agreeable, talked much of my uncle, Sir Guy, whose fag he had been at Eton half a century before, promised me some capital shooting in his preserves, discussed the state of politics; and, as the second decanter of port “waned apace,” grew wondrous confidential, and told me of his intention to start his son for the county at the next general election, such being the object which had now conferred the honour of his presence on his Irish estates.

Her ladyship was most condescendingly civil, vouchsafed much tender commiseration for my “exile,” as she termed my quarters in Kilrush; wondered how I could possibly exist in a marching regiment, (who had never been in the cavalry in my life!) Spoke quite feelingly on my kindness in joining their stupid family party, for they were living, to use her own phrase, “like hermits;” and wound up all by a playful assurance that as she perceived, from all my answers, that I was bent on preserving a strict incognito, she would tell no tales about me on her return to “Town.” Now, it may readily be believed, that all this, and many more of her ladyship’s allusions, were a “Chaldee manuscript” to me; that she knew certain facts of my family and relations, was certain; but that she had interwoven in the humble web of my history, a very pretty embroidery of fiction was equally so; and while she thus ran on, with innumerable allusions to Lady Marys and Lord Johns, who she pretended to suppose were dying to hear from me, I could not help muttering to myself with good Christopher Sly, “And all this be true—then Lord be thanked for my good amends;” for up to that moment I was an ungrateful man for all this high and noble solicitude. One dark doubt shot for an instant across my brain. Maybe her ladyship had “registered a vow” never to syllable a name unchronicled by Debrett, or was actually only mystifying me for mere amusement. A minute’s consideration dispelled this fear; for I found myself treated “en Seigneur” by the whole family. As for the daughters of the house, nothing could possibly be more engaging than their manner. The eldest, Lady Jane, was pleased from my near relationship to her father’s oldest friend to receive me, “from the first,” on the most friendly footing; while, with the younger, Lady Catherine, from her being less ‘maniere’ than her sister, my progress was even greater; and thus, before we separated for the night, I contrived to “take up my position” in such a fashion, as to be already looked upon as one of the family party, to which object, Lord and indeed Lady Callonby seemed most willing to contribute, and made me promise to spend the entire of the following day at Callonby, and as many of the succeeding ones as my military duties would permit.

As his lordship was wishing me “good night” at the door of the drawing-room, he said, in a half whisper,

“We were ignorant yesterday, Mr. Lorrequer, how soon we should have had the pleasure of seeing you here; and you are therefore condemned to a small room off the library, it being the only one we can insure you as being well aired. I must therefore apprize you that you are not to be shocked at finding yourself surrounded by every member of my family, hung up in frames around you. But as the room is usually my own snuggery, I have resigned it without any alteration whatever.”