Project Gutenberg's Famous Firesides of French Canada, by Mary Wilson Alloway This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net Title: Famous Firesides of French Canada Author: Mary Wilson Alloway Release Date: December 14, 2009 [EBook #30674] Language: English Character set encoding: UTF-8 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK FAMOUS FIRESIDES OF FRENCH CANADA *** Produced by Marcia Brooks, Josephine Paolucci and the Online Distributed Proofreading Canada Team at http://www.pgdpcanada.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/Canadian Libraries)

Hearths beside which were rocked the cradles of those who

made the history of Canada.

Hearths beside which were rocked the cradles of those who

made the history of Canada.

MONTREAL:

PRINTED BY JOHN LOVELL & SON

1899

Entered according to Act of Parliament of Canada, in the year one thousand eight hundred and ninety-nine, by Mary Wilson Alloway, in the office of the Minister of Agriculture and Statistics at Ottawa.

TO

THE RIGHT HONOURABLE

LORD STRATHCONA AND MOUNT ROYAL, G.C.M.G., LL.D., &c.,

CHANCELLOR OF McGILL UNIVERSITY, MONTREAL,

AND

HIGH COMMISSIONER FOR CANADA IN LONDON,

THIS VOLUME

IS

BY SPECIAL PERMISSION

Respectfully Dedicated

BY

THE AUTHOR.

The principal authorities consulted in the preparation of this work were Le Moyne, Kingsford, Rattray, Garneau, Parkman, Hawkins and Bouchette.

Acknowledgments are also due to the kind interest evinced and encouragement given by the Hon. Judge Baby, President of the Numismatic and Antiquarian Society of Montreal.

Château de Ramezay 19

Heroes of the Past 30

Chapel of Notre-Dame-de-la-Victoire 51

Le Séminaire 56

Cathedrals and Cloisters 58

Massacre of Lachine 82

Château de Vaudreuil 95

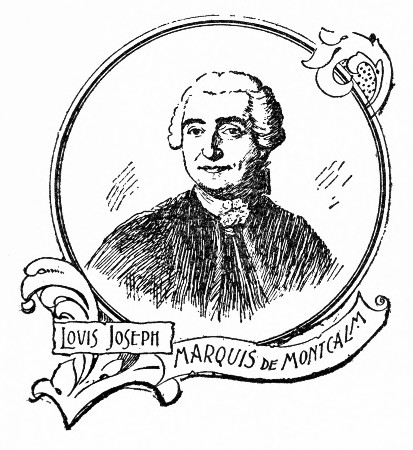

Battle of the Plains 103

Canada under English Rule 125

American Invasion 144

The Continental Army in Canada 155

Fur Kings 192

Interesting Sites 199

Famous Names 203

Echoes from the Past 212

Page.

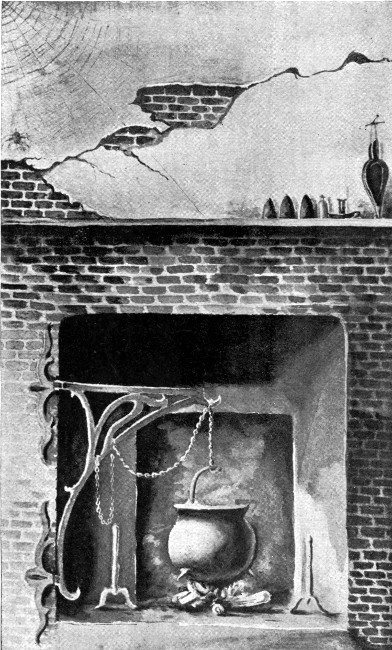

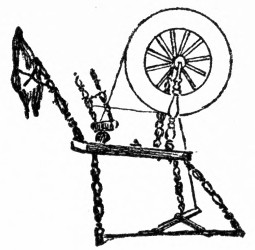

Fireplace Frontispiece.

Château Kitchen 24

Château de Ramezay 26

Montgomery Salon 28

Chapel of Notre Dame de la Victoire 52

Le Séminaire 56

Home of La Salle 84

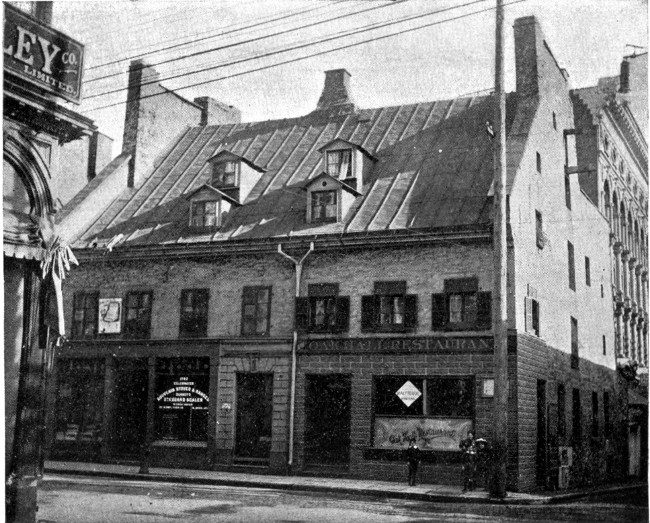

St. Amable St. 98

Fort Chambly 146

Château Fortier 156

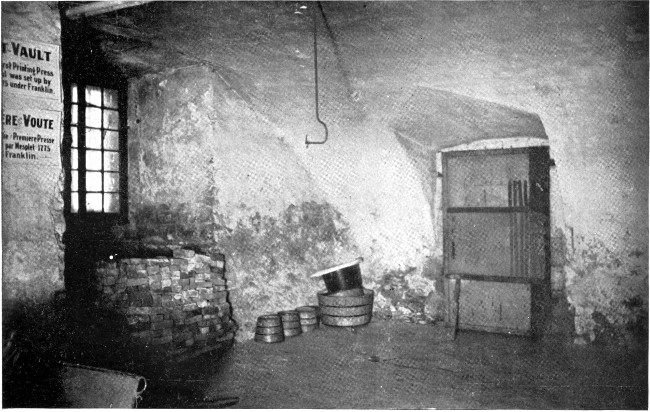

Franklin Vaults 170

In offering this little volume to the kind consideration of Canadian and American readers, it is the earnest wish of the Author that it may commend itself to the interest of both, as the early histories of Canada and the United States are so closely connected that they may be considered identical.

We have tried to recall the days when, by these firesides, we re rocked the cradles of those who helped to make Canadian history, and to render more familiar the names and deeds of the great men, French, English and American, upon whose valour and wisdom such mighty issues depended.

The recital is, we trust, wholly impartial and without prejudice.

It is to be hoped that the union of sentiment which the close of this century sees between the two great Anglo-Saxon peoples may cast[Pg xii] a veil of forgetfulness over the strife of the one preceding it; and be a herald of that reign of peace, when "nation shall no more rise against nation, and wars shall cease."

Montreal, May 24, 1899.

About twelve years after the first Spanish caravel had touched the shores of North America, we find the French putting forth efforts to share in some of the results of the discovery. In the year 1504 some Basque, Breton and Norman fisher-folk had already commenced fishing along the bleak shores of Newfoundland and the contiguous banks for the cod in which this region is still so prolific.

The Spanish claim to the discovery of America is disputed by several aspirants to that honour. Among these are the ancient mariners of Northern Europe, the Norsemen of the Scandinavian Peninsula. They assert that their Vikings touched American shores three centuries before Isabella of Castille drove the Moors from their palaces among the orange groves of Espana. Eric the Red, and other sea-kings, made voyages to Iceland and Greenland[Pg 14] in the eleventh and following centuries; and it is highly probable that these Norsemen, with their hardihood and enterprise, touched on some part of the mainland. One Danish writer claims that this occurred as far back as the year 985, about eighty years after the death of the Danes' mortal enemy, the great Saxon King Alfred.

Even the Welsh, from the isolation of their mountain fastnesses, declare that a Cambrian expedition, in the year 1170, under Prince Modoc, landed in America. In proof of this, there is said to exist in Mexico a colony bearing indisputable traces of the tongue of these ancient Celts.

The term Canada first appears as the officially recognized name of the region in the instructions given by Francis I to its original colonists in the year 1538.

There are various theories as to the etymology of the word, its having by different authorities been attributed to Indian, French and Spanish origins.

In an old copy of a Montreal paper, bearing date of Dec. 24, 1834, it is asserted[Pg 15] that Canada or Kannata is an Indian word, meaning a village, and was mistaken by the early visitors for the name of the whole country.

The Philadelphia Courier, of July, 1836, gives the following not improbable etymology of the name of the province:—Canada is compounded of two aboriginal words, Can, which signifies the mouth, and Ada the country, meaning the mouth of the country. A writer of the same period, when there seems to have been considerable discussion on the subject, says:—The word is undoubtedly of Spanish origin, coming from a common Spanish word, Canada, signifying a space or opening between mountains or high banks—a district in Mexico of similar physical features, bearing the same name.

"That there were Spanish pilots or navigators among the first discoverers of the St. Lawrence may be readily supposed, and what more natural than that those who first visited the gulf should call the interior of the country El Canada from the typographical appearance of the opening to it,[Pg 16] the custom of illiterate navigators naming places from events and natural appearances being well established."

Hennepin, an etymological savant, declares that the name arose from the Spaniards, who were the first discoverers of Canada, exclaiming, on their failure to find the precious metals, "El Capa da nada," or Cape Nothing. There seems to be some support of this alleged presence of the Spanish among the early navigators of the St. Lawrence, by the finding in the river, near Three Rivers, in the year 1835, an ancient cannon of peculiar make, which was supposed to be of Spanish construction.

The origins of the names of Montreal and Quebec are equally open to discussion. Many stoutly assert that Montreal is the French for Mount Royal, or Royal Mount; others, that by the introduction of one letter, the name is legitimately Spanish—Monte-real. Monte, designating any wooded elevation, and that real is the only word in that language for royal.

The word Quebec is attributed to Indian and French sources. It is said that it is[Pg 17] an Algonquin word, meaning a strait, the river at this point being not more than a mile wide; but although Champlain coincided in this view, its root has never been discovered in any Indian tongue. Its abrupt enunciation has not to the ear the sound of an Indian word, and it could scarcely have come from the Algonquin language, which is singularly soft and sweet, and may be considered the Italian of North American dialects.

Those who claim for it a French origin, say that the Normans, rowing up the river with Cartier at his first discovery, as they rounded the wooded shores of the Isle of Orleans, and came in sight of the bare rock rising three hundred feet from its base, exclaimed "Quel bec!" or, What a promontory! The word bears intrinsically strong evidence of Norman origin.

Cape Diamond received its name from the fact that in the "dark colored slate of which it is composed are found perfectly limpid quartz crystals in veins, along with crystallized carbonate of lime, which, sparkling like diamonds among the crags, suggested the appellation."

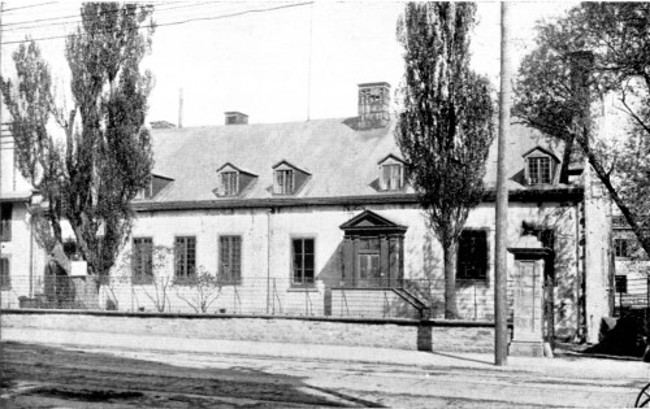

A few yards from the busy municipal centre of the city of Montreal, behind an antique iron railing, is a quaint, old building known as the Château de Ramezay. Its history is contemporary with that of the city for the last two centuries, and so identified with past stirring events that it has been saved from the vandalism of modern improvement, and is to be preserved as a relic of the old Régime in New France. It is a long one-storied structure, originally red-tiled, with graceful, sloping roof, double rows of peaked, dormer windows, huge chimneys and the unpolished architecture of the period.[Pg 20]

Among the many historical buildings of America, none have been the scene of more thrilling events, a long line of interesting associations being connected with the now quiet old Château, looking in its peaceful old age as out of keeping with its modern surroundings as would an ancient vellum missal, mellowed for centuries in a monkish cell, appear among some of the ephemeral literature of to-day.

A brilliant line of viceroys have here held rule, and within its walls things momentous in the country's annals have been enacted. During its checkered experience no less than three distinct Régimes have followed each other, French, British and American. In an old document still to be found among the archives of the Seminary of St. Sulpice, it is recorded that the land on which it stands was ceded to the Governor of Montreal in the year 1660, just eighteen years after Maisonneuve, its founder, planted the silken Fleur-de-Lys of France on the shores of the savage Redman, and one hundred years before the tri-cross of England floated for the first time from the ramparts.[Pg 21]

Somewhere about the year 1700 a portion of this land was acquired by Claude de Ramezay, Sieur de la Gesse, Bois Fleurent and Monnoir, in France, and Governor of Three Rivers, and this house built.

De Ramezay was of an old Franco-Scottish family, being descended by Thimothy, his father, from one Sir John Ramsay, a Scotchman, who, with others of his compatriots, went over to France in the 16th century. He may have joined an army raised for the French wars, or may have formed part of a bridal train similar to the gay retinue of the fair Princess Mary, who went from the dark fells and misty lochs of the land of the Royal Stuarts to be the loveliest queen who ever sat on the throne of la belle France. De Ramezay was the father of thirteen children, by his wife, Mademoiselle Denys de la Ronde, a sister of Mesdames Thomas Tarieu de La Naudière de La Pérade, d'Ailleboust d'Argenteuil, Chartier de Lotbinière and Aubert de la Chenage, the same family out of whom came the celebrated de Jumonville, so well known in connection with the[Pg 22] unfortunate circumstances of Fort Necessity. The original of the marriage contract is still preserved in the records of the Montreal Court House; with its long list of autographs of Governor, Intendant, and high officials, civil and military, scions of the nobility of the country, appended thereto. The annals of the family tell us that some of them died in infancy, several met violent and untimely deaths, two of the sisters took conventual vows in the cloisters of Quebec, two married, having descendants now living in France and Canada, and two remained unmarried.

De Ramezay came over as a captain in the army with the Viceroy de Tracy, and was remarkable for his highly refined education, having been a pupil of the celebrated Fénélon, who was said to have been the pattern of virtue in the midst of a corrupt court, and who was entrusted by Louis the Fourteenth with the education of his grandsons, the Dukes of Burgundy, Anjou and Berri. Had the first named, who was heir-presumptive to the throne, lived to practice the princely virtues, the seeds of[Pg 23] which his preceptor had sown in his heart, some of the most bloody pages in French history might never have been written.

De Ramezay, for many years being Governor of Montreal, held official court in the Council chamber to the right of the entrance hall of the Château, which is now a museum of rare and valuable relics of Canada's past.

The Salon was the scene of many a gay rout, as Madame de Ramezay, imitating the brilliant social and political life as it was in France in the time of Le Grand Monarque, transplanted to the wilds of America some reflection of court ceremonial and display as they culminated in that long and brilliant reign. From the dormer windows above, high-bred French ladies looked at the sun rising over the forest-clothed shores of the river, on which now stands the architectural grandeur of the modern city. How strange to the swarthy-faced dwellers in the wigwam must the old-time gaieties have appeared, as the lights from the silver candelabres shone far out in the night, when the old Château was en fête[Pg 24] and aglow with music, dancing and laughter.

What a contrast to the burden-bearing squaws were the dainty French women in stiff brocade and jewels, high heels, paint, patches and tresses à la Pompadour, tripping through the stately measures of the minuet to the sound of lute or harpsichord!

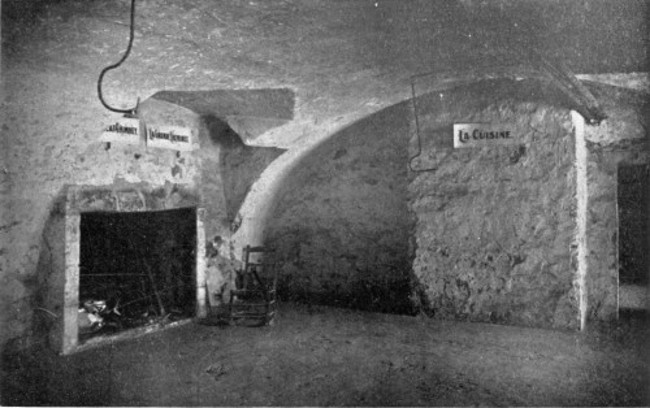

The servants and retainers, imitating their lords, held high revel in the vaulted kitchens; while dishes and confections, savoury and delicious, came from the curious fireplace and ovens recently discovered in the vaults. These ancient kitchen offices, built to resist a siege, are exceedingly interesting in the light of our culinary arrangements of to-day. They were so constructed that if the buildings above, with their massive masonry, were destroyed, they would afford safe and comfortable refuge. The roof is arched, and, like the walls, is several feet thick, of solid stone, lighted by heavily barred windows, with strong iron shutters. In clearing out the walled-up and long-forgotten ovens, there were found bits of broken crockery, pipe-stems and the ashes of fires, gone out many, many long years ago. As indicated by an early map of the city, the position of the original well was located; in which, when it is cleaned out, it is intended to hang an old oaken bucket and drinking cups as nearly as possible as they originally were.

Ancient kitchen and fireplace of the Château de Ramezay.

Ancient kitchen and fireplace of the Château de Ramezay.Some time after the death of de Ramezay, which occurred in the city of Quebec in 1724, these noble halls fell into the possession of the fur-traders of Canada, and many a time these underground cellars were stored with the rich skins of the mink, silver fox, marten, sable and ermine for the markets of Europe and for royalty itself. They were brought in by the hunters and trappers over the boundless domains of the fur companies, and by the Indian tribes friendly to the peltrie trade. As these hardy, bronzed men sat around the hearth, while the juicy haunch of venison roasted on the spit by the blazing logs,[Pg 26] relating blood-curdling tales and hairbreadth escapes, they were a necessary phase of times long passed away, but which will always have a picturesqueness especially their own.

Instead of the white man's influencing the savage towards civilized customs, it was often found, as one writer has said, that hundreds of white men were barbarized on this continent for each single savage that was civilized. Many of the former identified themselves by marriage and mode of life with the Indians, developed their traits of hardihood and acquired their knowledge of woodcraft and skill in navigating the streams. In pursuit of the fur-bearing animals in their native haunts, they shot the raging rapids, ventured out upon the broad expanse of the treacherous lakes, and endured without complaint the severity of winter and the exposure of forest life in summer.

CHATEAU DE RAMEZAY.

CHATEAU DE RAMEZAY.

Their ranks were continually increased by those who were impatient of the slow method of obtaining a livelihood from the tillage of the soil, when the husbandman was frequently driven from the plough by the sudden attack of Indian foes, or interrupted in his hasty and anxious harvesting by their war-whoop, or perhaps was compelled to leave his farm to take up arms, if the occasion arose, so that in many instances the homesteads were left to the old men, women and children. The excitement of the chase and the wild freedom of the plains had a fascination that many could not resist, so much so that the king had to promulgate an edict, to stop, under heavy penalties, this roving life of his Canadian subjects, as their nomadic tendencies interfered with the successful settlement of the colony.

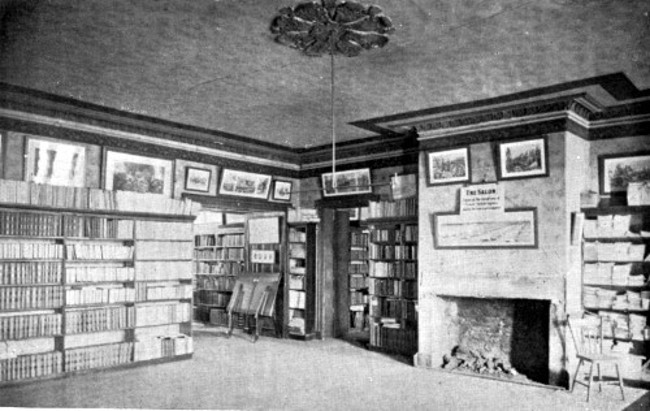

To the lover of the quaint architecture of other centuries, there is an indescribable charm in these time-worn walls, which are still as substantial as if the snows and rains of two centuries had not beaten against them. The interior is equally interesting in this regard, as the walls dividing the chambers and corridors, though covered with modern plaster and stucco, are found to consist of several feet of solid[Pg 28] stone masonry, while the ornamental ceiling covers beams of timber, twenty inches by eighteen, which is strong, well jointed and placed as close as flooring. Above this is heavy stone work over twelve inches thick, so that the sloping roof was the only part pregnable in an assault with the munitions of war then in use. Upon removing a portion of the modern wainscotting in the main reception room, there was discovered an ancient fireplace, made of roughly hewn blocks of granite. A crescent-shaped portion of the hearthstone is capable of removal, for what purpose it is not known. With old andirons and huge logs, it looks to-day exactly as it must have done when Montgomery and his suite, in revolutionary uniform, received delegations in this chamber, and when Brigadier General Wooster, who succeeded him, wrote and sent despatches by courier from the French Château to the Colonial mansion at Mount Vernon.

Salon in which Montgomery held official receptions, 1775.

Salon in which Montgomery held official receptions, 1775.The rooms of state in those days were, it is said, all in what is at present the back of the house, the rear of the building being the front, facing the river, down to which ran the gardens.

It may be that the moonlight cast on these panes the shadow of the noble Sir Jeffrey Amherst, in his red coat, as looking out over the river he may have seen the smoke of the fire lighted by de Lévis, where he burnt his colours rather than let them fall into the hands of the English.

On the river bank below the Château, tradition says, was the spot trodden by Jacques Cartier, who gave the river its name. Born at the time when all Europe was still excited over the tales of Columbus' adventures, he left the white cliffs and grey docks of St. Malo, where he had learned the sailor's craft, to search for the western route to the Indies.

A little higher up, less than a century later, Champlain, to push on actively his operations in the fur-trade, built his fort, the name which he then gave the spot, "Place Royale," being recently restored to it. In his wanderings for the further pursuance of this object, he discovered Lakes Ontario, Huron and Champlain.

Being betrothed to a twelve year old maiden, Hélène Bouillé, the daughter of a Huguenot, he named the island opposite the city, which lies like a green gem among the crystal waters, Hélène, in[Pg 31] affectionate remembrance of her who, at the end of eight years, was to join him in his adventurous life.

The winding length of quiet, old St. Paul street, then an Indian trail, following the course of the river through the oak forest, must often have known the presence of this picturesque warrior in his weather-beaten garments of the doublet and long hose then in vogue. "Over the doublet he buckled on a breastplate, and probably a back piece, while his thighs were protected by cuisses of steel and his head by a plumed casque. Across his shoulders hung the strap of his baudolier or ammunition box, at his side was his sword, and in his hand his arquebuse. Such was the equipment of this ancient Indian fighter, whose exploits date eleven years before the Puritans landed," among the grey granite hills of New England.

He was an armourer of Dieppe, who, though "a great captain, a successful discoverer and a noted geographer, was more than all a God-fearing, Christian[Pg 32] gentleman." He was more concerned to gain victories by the cross than by the sword, saying:—"The salvation of a soul is of more value than the conquest of an empire."

The year 1620 was a red letter day in the history of the Colony, when, from a little vessel moored at the foot of the cliff, he led on shore at Quebec his young bride, who with her three maids had come to the western wilderness, the first gentlewoman to land on Canadian shores. He conducted her to where is now the corner of Notre Dame and Sous-le-Fort streets, to the rude "habitation" he had prepared for her reception, which was poorly furnished and unhomelike in comparison to the one which she had left over the sea. But history tells of no word of complaint nor disappointment coming from the gentle lips; but, as the youthful châteleine sat by her hearth, it shed a light among the huts of the settlers and dusky lodges of the natives, as her example of patience and duty performed by the first refined, civilized fireside in the land does[Pg 33] to the thousands who have succeeded her. After almost three hundred years, the "charms of her person, her elegance and kindliness of manner" are still remembered. The chronicler tells us that the "Governor's lady wore in her daily rambles, amongst the wigwams, an article of feminine attire, not unusual in those days, a small mirror at her girdle." It appealed irresistibly to the simple natures around her, that "a beauteous being should love them so much as to carry their images reflected close to her heart."

"The graceful figure of the first lady of Canada, gliding noiselessly along by the murmuring waters of the St. Lawrence, showering everywhere smiles and kindness, a help-mate to her noble lord, and a pattern of purity and refinement, was indeed a vision of female loveliness" which time cannot obliterate nor forgetfulness dim. The domestic life of the colony dates from about the time of her arrival, the first regular register of marriage being entered in the following year; two months after the first nuptial ceremony[Pg 34] was performed in New England. The first christening took place in the same year, 1621, the ordinance being administered to the infant son of Abraham Martin, dit L'Ecossais, pilot of the river St. Lawrence. This old pilot, named in the journal of the Jesuits as Maître Abraham, has bequeathed his name to the famous Plains, on which was decided the destiny of New France.

It was indeed a sorry day for the settlement when the inhabitants, on the 16th of August, 1624, saw the white sails of Champlain's vessel disappear behind what is now Point Levis, carrying back, alas! forever, to the shores of her beloved France, Madame de Champlain, sighing for the mystic life of the cloister, tired out by the incessant alarms and the Indian ferocities spread around the Fort during the frequent absences of her husband and her favourite brother, Eustache Bouillé. The daintily-nurtured French lady must have found the quiet of the old-world convent a very haven of peace and rest. She died at Mieux, an[Pg 35] Ursuline Nun, in the order which subsequently was to be so closely identified with the religious history of her wilderness home.

But monastic retreat had no attractions for the founder of Fort St. Louis. Parkman says: "Champlain, though in Paris is restless. He is enamoured of the New World, whose rugged charms have seized his fancy and his heart. His restless thoughts revert to the fog-wrapped coasts, the piney odours of the forests, the noise of waters and the sharp and piercing sunlight so dear to his remembrance."

Among these he was destined to lay down his well worn armour at the command of death, the only enemy before whom he ever retreated; for on Christmas Day, 1635, in a chamber in the Fort at Quebec, "breathless and cold lay the hardy frame which war, the wilderness and the sea had buffeted so long in vain. The chevalier, crusader, romance-loving explorer and practical navigator lay still in death," leaving the memory of a courage[Pg 36] that was matchless and a patience that was sublime.

For over two hundred and sixty years, no monument stood to celebrate this true patriot's name, but now his statue stands in his city, near to where he laid the foundations and built the Château St. Louis. Most unfortunately his last resting place is unknown, notwithstanding the laborious and learned efforts of the many distinguished antiquarians of Quebec.

The Fort which Champlain built in 1620, and in which he died, was for over two centuries the seat of government, and the name recalls the thrilling events which clothed it with an atmosphere of great and stirring interest during its several periods. The hall of the Fort during the weakness of the colony was often, it is said, a scene of terror and despair from the inroads of the ferocious savages, who, having passed and overthrown all the French outposts, threatened the Fort itself, and massacred some friendly Indians within sight of its walls.[Pg 37]

"In the palmy days of French sovereignty it was the centre of power over the immense domain extending from the Gulf of St. Lawrence along the shores of the noble river and down the course of the Mississippi to its outlet below New Orleans.

The banner which first streamed from the battlements of Quebec was displayed from a line of forts which protected the settlements throughout this vast extent of country. The Council Chamber of the Castle was the scene of many a midnight vigil, many a long deliberation and deep-laid project, to free the continent from the intrusion of the ancient rivals of France and assert her supremacy. Here also was rendered, with all its ancient forms, the fealty and homage of the noblesse and military retainers, who held possessions under the Crown, a feudal service suited to those early times, and which is still performed by the peers at the coronation of our kings in Westminster Abbey."[Pg 38]

Among the many dramatic scenes of which it was the theatre, no occurrence was more remarkable than an event which happened in the year 1690, when "Castle St. Louis had assumed an appearance worthy of the Governor-General, who then made it the seat of the Royal Government, the dignified Count de Frontenac, a nobleman of great talents, long service and extreme pride, and who is considered[Pg 39] one of the most illustrious of the early French rulers." The story is, that Sir William Phipps, an English admiral, arriving with his fleet in the harbour, and believing the city to be in a defenceless condition, thought he might capture it by surprise. An officer was sent ashore with a flag of truce. He was met half way by a French major and his men, who, placing a bandage over the intruder's eyes, conducted him by a circuitous route to the Castle, having recourse on the way to various stratagems, such as making small bodies of soldiers cross and re-cross his path, to give him the impression of the presence of a strong force. On arriving at the Castle, his surprise we are told was extreme on finding himself in the presence of the Governor-General, the Intendant and the Bishop, with a large staff of French officers, uniformed in full regimentals, drawn up in the centre of the great hall ready to receive him.

The British officer immediately handed to Frontenac a written demand for an unconditional surrender, in the name[Pg 40] of the new Sovereigns, William and Mary, whom Protestant England had crowned instead of the dethroned and Catholic James. Taking his watch from his pocket and placing it on a table near by, he peremptorily demanded a positive answer in an hour's time at the furthest. This action was like the spark in the tinder, and completely roused the anger and indignation of his hearers, who had scarcely been able to restrain their excitement during the reading of the summons, which the Englishman had delivered in an imperious voice, and which an interpreter had translated word for word to the outraged audience.

A murmur of repressed resentment ran through the assembly, when one of the officers, without waiting for his superior to reply, exclaimed impetuously:—that the messenger ought to be treated as the envoy of a corsair, or common marauder, since Phipps was in arms against his legitimate Sovereign. Frontenac, although keenly hurt in his most vulnerable point,—his pride—by the lack of ceremony displayed[Pg 41] in the conduct of the Englishman, replied in a calm voice, but in impassioned words, saying loftily:—"You will have no occasion to wait so long for my answer,—here it is:—I do not recognize King William, but I know that the Prince of Orange is an usurper, who has violated the most sacred ties of blood and religion in dethroning the King, his father-in-law; and I acknowledge no other legitimate Sovereign than James the Second. Do your best, and I will do mine."

The messenger thereupon demanded that the reply be given him in writing, which the Governor haughtily refused, saying:—

"I am going to answer your master at the cannon's mouth; he shall be taught that this is not the manner in which a person of my rank ought to be summoned."

Charlevoix seems to have very much admired the lordly bearing of Frontenac on this occasion, which was so trying to his self-control, but, with an impartiality creditable to a Frenchman, he justly[Pg 42] chronicles his equal admiration for the coolness and presence of mind with which the Englishman signalized himself in carrying out his mission, under insults and humiliations scarcely to be looked for from those who should have known better the respect due to a flag of truce.

The commander of the fleet, finding the place ready for resistance, concluded that the lateness of the season rendered it unwise to commence a regular siege against a city whose natural and artificial defences made it a formidable fortress, and which, when garrisoned by troops of such temper and mettle, it appeared impossible to reduce. It must also be considered that Phipps had been delayed by contrary winds and pilots ignorant of the river navigation, which combination of untoward circumstances conspired to compel him to relinquish his design, which under more favouring conditions he might have carried out with success, and conquered the place before it could have been known in Montreal that it was even in danger.[Pg 43]

"Without doubt Frontenac was the most conspicuous figure which the annals of the early colonization of Canada affords. He was the descendant of several generations of distinguished men who were famous as courtiers and soldiers." He was of Basque origin and proud of his noble ancestry. He was born in 1620, and was distinguished by becoming the god-child of the King, the royal sponsor bestowing his own name on the unconscious babe, who was in after years to be a sturdy defender of France's dominions over the ocean. He became a soldier at the age of fifteen, and even in early youth and manhood saw active service and gave promise of gallantry and bravery.

In October, 1648, he married the lovely young Anne de la Grange-Trianon, a "maiden of imperious temper, lively wit and marvellous grace." She was a beauty of the court and chosen friend of Mademoiselle de Montpensier, the granddaughter of King Henry the Fourth. A celebrated painting of the Comtesse de Frontenac,[Pg 44] in the character of Minerva, smiles on the walls of one of the galleries at Versailles.

The marriage took place without the consent of the bride's relatives, and soon proved an ill-starred one, the young wife's fickle affection turning into a strong repulsion for her husband, whom she intrigued to have sent out of the country.

Her influence at court, and some jealousy on the part of the King combined to bring about this end, and Frontenac was appointed Governor and Lieutenant-General of La Nouvelle France.

Parkman says:—"A man of courts and camps, born and bred in the focus of a most gorgeous civilization, he was banished to the ends of the earth, among savage hordes and half-reclaimed forests, to exchange the splendour of St. Germain and the dawning glories of Versailles for a stern, grey rock, haunted by sombre priests, rugged merchants, traders, blanketed Indians and wild bushrangers." When he sailed up the river and the stern grandeur of the scene opened up before him, he felt as he afterwards wrote:—[Pg 45]

"I never saw anything more superb than the position of this town. It could not be better situated for the future capital of an empire."

But the dainty and luxurious Comtesse had no taste for pioneer life, and no thought of leaving her silken-draped boudoir for a home in a rude fort on a rock; she therefore accepted the offer of a domicile with her kindred spirit, Mademoiselle d'Outrelaise. The "Divines," as they were called, established a Salon, which, among the many similar coteries of the time, was remarkable for its wit and gaiety. It set the fashion to French society, and was affected by all the leading spirits of the Court and Capital.

Although an occasional billet came from the recreant spouse to her husband in the Castle St. Louis, no home life nor welcoming domestic fireside threw a charm over his exile. The glamour with which affection can glorify even the rudest surroundings was denied him in his long life of seventy-six years.

To avoid the confusion to which the[Pg 46] terms Fort St. Louis and Castle St. Louis might lead, it must be understood that they in a measure were the same, as the one enclosed the other.

In the year 1834, two hundred and fourteen years after the foundation of this Château, a banquet was prepared for the reception of those invited to partake of the official hospitality of the Governor; when suddenly the tocsin sounded,—the dreaded alarm of fire. Soon the streets were thronged with citizens, with anxious enquiries passing from lip to lip, and ere long the cry was uttered: "To the Castle, to the Castle!"

The entire population of merchants and artisans, soldiers from the garrison, priests from the monasteries, and citizens, rich and poor, joined hands with the firemen to save the mediæval fortress from destruction, and its treasured contents from the flames. Old silver was snatched from the banquet table by some who had expected to sit around the board as guests.

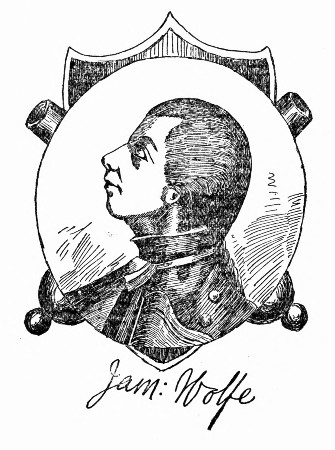

At the head of the principal staircase, where it had stood for fifty years or more,[Pg 47] was a bust of Wolfe, with the inscription upon it:—

Fortunately, in the confusion of the disaster it was not overlooked, but was carried to a place of safety. While every heart present could not but be moved with the deepest feelings of regret at the loss of its hoary walls, yet the beholder was forced to admire the magnificent spectacular effect of the conflagration which crowned the battlements and reflected over crag and river, as the old fort, which had stubbornly resisted all its enemies during five sieges, fell before the devouring element.

Its stones were permeated with the military and religious history of the "old rock city," for, in the fifteen years of its occupancy by Champlain, it was as much a mission as a fort. The historian says:—"A stranger visiting the Fort of Quebec would have been astonished at its air of conventual decorum. Black-robed Jesuits[Pg 48] and scarfed officers mingled at Champlain's table. There was little conversation, but in its place histories and the lives of the saints were read aloud, as in a monastic refectory. Prayers, masses and confessions followed each other, and the bell of the adjacent chapel rang morning, noon and night. Quebec became a shrine. Godless soldiers whipped themselves to penitence, women of the world outdid each other in the fury of their contrition, and Indians gathered thither for the gifts of kind words and the polite blandishments bestowed upon them."

The site where the old Château St. Louis once stood, with its halo of romance and renown, is now partially covered by the great Quebec hostelry, the Château Frontenac, which in its erection and appointments has not destroyed, but rather perpetuated, the traditions of the "Sentinel City of the St. Lawrence."

"Château Frontenac has been planned with the strong sense of the fitness of things, being a veritable old-time Château, whose curves and cupolas, turrets and[Pg 49] towers, even whose tones of gray stone and dulled brick harmonize with the sober quaint architecture of our dear old Fortress City, and looks like a small bit of Mediæval Europe perched upon a rock."

Under the promenade of Durham Terrace is still the cellar of the old Château; and standing upon it, the patriot, whether English or French, cannot but thrill as he looks on the same scene upon which the heroes of the past so often gazed, and from which they flung defiance to their foes.

On almost the same spot upon which Champlain had landed at Montreal, and about seven years after his death, a small band of consecrated men and women, singing a hymn, drew up their tempest-worn pinnace, and raised their standard in the name of King Louis, while Maisonneuve, the ascetic knight, planted a crucifix, and dedicated the land to God.

The city as it stands on this spot is a fulfilment of his vow then made, when he declared, as he pitched his tent and lighted his camp-fire, that here he would found a city though every tree on the island were[Pg 50] an Iroquois. On an altar of bark, decorated with wild flowers and lighted by fireflies, the first mass was celebrated, and the birthnight of Montreal registered.

From the little seed thus planted in this rude altar, a mighty harvest has arisen in cathedral, monastery, church and convent, representing untold wealth and influence. The early French explorer, with a "sword in his hand and a crucifix on his breast," was more desirous of Christianizing than of conquering the native tribes. So completely has this creed become identified with the country's character and history, that the province of Quebec is emphatically a Catholic community. So faithfully have its tenets been handed down by generations of devout followers of this faith, that even the streets and squares bear the names of saints and martyrs, such as St. Francis Xavier, St. Peter, St. John, St. Joseph, St. Mary, and in fact the entire calendar is represented, especially in the east end of the town. St. Paul, which was probably the first street laid out, is called after the city's founder himself,—Paul Chomedy de Maisonneuve.

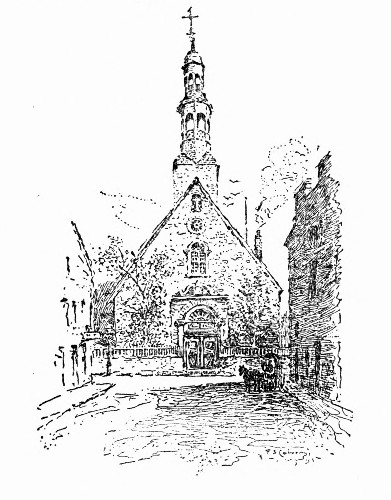

A few rods to the west of the Château, through a vaulted archway leading from the street, in the shadow of the peaceful convent buildings is a little chapel called Notre-Dame-de-la-Victoire. The swallows twittering under its broken eaves are now the only sign of life; and its rotting timbers and threshold, forgotten by the world, give no suggestion of the martial incident to which it owes its existence. While the American Colonies were still English, the British Ensign floated over Boston town, and good Queen Anne was prayed for in Puritan pulpits, an expedition was fitted out under Sir Hovenden Walker to drive the French out of Canada. In the previous year, 1710, the Legislature of New York had taken steps to lay before the Queen the alarming progress of Gallic domination in America, saying:—

"It is well known that the French can[Pg 52] go by water from Quebec to Montreal; from thence they can do the like through the rivers and lakes, at the risk of all your Majesty's plantations on this Continent, as far as Carolina."

In the command of Walker were several companies of regulars draughted from the great Duke of Marlborough's Army. While he was leading it from victory to victory for the glory of his King, his wife, the famous Sarah Jennings, was making a conquest at home of the affections of the simple-minded and susceptible Queen. It is remarkable that the coronet of this ambitious woman should now rest on the brow of an American girl, and that a daughter of New York should reign at Blenheim Castle. At that period France possessed the two great valleys of North America, the Mississippi and the St. Lawrence; to capture the latter was the aim of the expedition.

CHAPEL OF NOTRE-DAME-DE-LA-VICTOIRE.

CHAPEL OF NOTRE-DAME-DE-LA-VICTOIRE.As the hostile fleet sailed up the St. Lawrence, a storm of great severity burst upon the invaders. Eight of the transports were recked on the reefs, and in the dawn of the midsummer morning the bodies of a thousand red-coated soldiers were strewn on the sands of Isle-aux-Œufs. It has been said that an old sea-dog, Jean Paradis, refused to act as pilot, and in a fog allowed them to run straight on to death; and also that among those who perished was one of the court beauties who had eloped with Sir Hovenden.

The disabled vessels retreated before the artillery of the elements, and left Bourbon's Lilied Blue to wave for half a century longer over Fort St. Louis. This bloodless victory for the French was attributed by them to the intervention of the Virgin, in gratitude for which this chapel was vowed and built, as was also another on the market place, Lower Town, Quebec. The miraculous feature of the defeated invasion was considered certain from the fact that a recluse in the convent near the chapel, and who was remarkable for her piety, had embroidered a prayer to the Virgin on the flag which the Baron de Longueuil had borne from Montreal in command of a detachment of troops.[Pg 54]

Some of the original interior fittings of the chapel still exist, but the bell which chimed its first call to vespers, when the great city was a quiet, frontier hamlet, has long been silent. It is to be regretted that from its historical character it has not been preserved from decay, but looks as time-worn and mouldering as does the rusty cannon in the hall of the Château, which was one of the guns of the ill-fated fleet, and over which the river had flowed for almost two hundred years. Seven of England's sovereigns had lived, reigned and died, and in France the Royal house had fallen in the deluge of blood that flowed around the guillotine. Quebec had changed flags—the Tri-color had been unfurled over the Hôtel-de-Ville at Paris, and the Stars and Stripes over the new-born nation.

The thrones of Europe had tottered at the word of the Corsican boy,—he had played with crowns as with golden baubles, and had gone from the imperial purple to the mist-shrouded rocks of St. Helena. Eugenie, the Beautiful, had ruled the world by her grace, and fled from the throne of[Pg 55] the haughty Louis to a loveless exile—while the old gun, with its charge rusting in its mouth, lay in silence under the passing keels of a million craft.

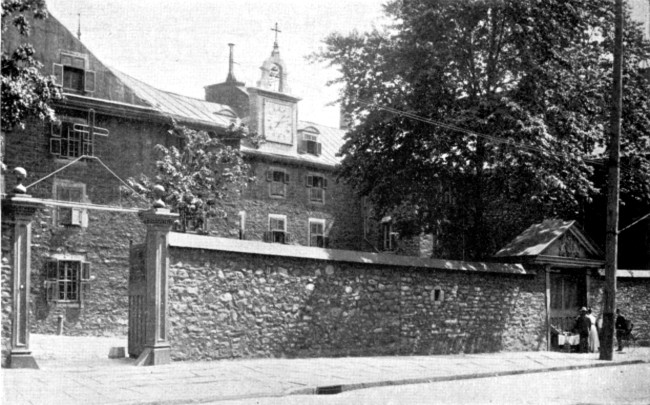

Still more ancient is a venerable postern in the blackened wall of the Seminary of St. Sulpice, near by, which is now the oldest building in the city, being erected some fifty years before the Château. It leads by a narrow lane to the gardens of the Monastery, which bloom quiet and still here in the heart of the throbbing life of a city of to-day. Generations of saintly men, under vows, have trodden in the shade of its walks, trying with the rigours of monastic life to crush out the memories of love and home left behind among the sun-kissed vineyards of France. For two hundred years and more no woman's footstep had fallen here among the flowers, until recently the wife of a Governor-General was admitted on a special occasion. On the cobble-stones of the courtyard, pilgrims, penitents, priests and soldiers have trodden, the echoes of their footsteps passing away in centuries of years. Above the walls, blackened by time and pierced by windows with the small panes of a fashion gone by, the bells of the clock ring out the stroke of midnight over one-third of a million souls, as it did the hours of morning when the great-great-grandfathers of the present generation ran to school over the grass-grown pavements of young Ville-Marie.

SEMINARY OF ST. SULPICE

SEMINARY OF ST. SULPICE

"The inimitable old roof-curves still cover the walls, and the Fleur-de-Lys still cap the pinnacles" as in the days when Richelieu, the prince of prelates, sought to plant the feudalism and Christianity of old France on the shores of the new. They still rise against the blue of Canadian skies unmolested, while in France, in the early years of the century, popular frenzy dragged this symbol of royalty from the spires of the churches and convents of Paris.

The Order of the Gentlemen of St. Sulpice is supposed to be very rich, the amount of the immense revenues never being made public. They were the feudal lords of the Island of Montreal in the earlier chapters of its history. Through their zealous efforts and the generosity of their parishioners was opened in the year eighteen hundred and twenty-nine the grand church adjoining, that of Notre Dame, built on the site of the original parish church. Viewing it from the extensive plaza in front, its imposing proportions fill the beholder with the same awe as when looking at some lofty mountain peak, but its symmetry is so exquisite that its size cannot at first be appreciated.

In imitation of its prototype, Notre Dame de Paris, twin towers rise in stateliness to a height of two hundred and twenty-seven feet, and are visible for a distance[Pg 59] of thirty miles. The façade is impressive, the style a modification of different schools adapted to carry out the design intended. Three colossal statues of the Virgin, St. Joseph and St. John the Baptist are placed over the arcades. The sublime structure belongs to a branch of the Gothic, in the pointed arch type of architecture which was brought home from the Crusades,—a style which has come down from the time-honoured architecture of the old world, when religious thought that now finds expression in books was written and symbolized in stone.

From a vestibule at the foot of the western tower, an ascent of two hundred and seventy-nine steps offers a most enchanting view of mountain, river, street and harbour, with such a wilderness of dome, steeple and belfry, that the exclamation involuntarily arises—this is truly a city of churches!

On the descent, a pause on a platform gives the opportunity of admiring "Le Gros Bourdon," or great bell, and one of the largest in the world. It weighs twenty-four[Pg 60] thousand, seven hundred and eighty pounds, and is six feet high. Its mouth measures eight feet, seven inches in diameter. The tone is magnificent in depth and fullness. On occasions such as the death of high ecclesiastics or other solemn events, its tolling is indescribable in its slow, sonorous vibrations. In the eastern tower hang ten smaller bells of beautiful quality, and so harmonized that choice and varied compositions can be performed by the eighteen ringers required in their manipulation. On high festivals, when all ring out with brazen tongues, caught up and re-echoed from spire to spire in what Victor Hugo describes as:—"Mingling and blending in the air like a rich embroidery of all sorts of melodious sounds"—America can furnish no greater oratorio.

Its interior, which is profusely embellished and enriched, the spacious, two-storied galleries, in a twilight of mysterious gloom, and an altar upon which so much wealth has been consecrated, combine to make it a temple worthy of any time or race.[Pg 61]

"Whatever may be the external differences, we always find in the Christian Cathedral, no matter how modified, the Roman Basilica. It rises forever from the ground in harmony with the same laws. There are invariably two naves intersecting each other in the form of a cross, the upper end being rounded into a chancel or choir. There are always side aisles for processions or for chapels, and a sort of lateral gallery into which the principal nave opens by means of the spaces between the columns.

"The number of chapels, steeples, doors and spires may be modified indefinitely, according to the century, the people and the art. Statues, stained glass, rose-windows, arabesques, denticulations, capitals and bas-reliefs are employed according as they are desired. Hence the immense variety in the exterior of structures, within which there dwells such unity and order."

The nave here is two hundred and twenty feet long, almost eighty in height, and one hundred and twenty in width, including the side aisles. The walls, which[Pg 62] are five feet thick, have fourteen side windows forty feet high, which light softly the galleries and grand aisle. So admirable is the arrangement, that fifteen thousand people can find accommodation and hear perfectly in all parts of the building. On high festivals, such as Christmas or Easter, when the great organ, said to be the finest in America, under the fingers of a master, with full choir and orchestra, rolls out the music of the masses, the senses are enthralled by the magnificence of the harmony. The various altars and mural decorations are beautiful with painting, gilding and carving. In the subdued light, which filters through the stained windows, are found many things of especial sanctity to the faithful. On a column rests an exquisite little statuette of the Virgin, which was a gift from Pope Pius the Ninth, the finely chased and wrought crucifix and the riband attached to it having been worn around the neck of the High Pontiff himself. Directly opposite to it is a statue of St. Peter, a copy of that at Rome. Fifty days indulgence are granted to those who piously[Pg 63] kiss this image. Under one altar rest the bones of St. Felix, which were taken from the Catacombs at Rome, and on another is a picture of the Madonna, said to be a copy of one painted by St. Luke. On all the shrines are candlesticks, votive offerings and many other articles of great age, value and veneration.

The main altar is exceedingly rich in artistic ornamentation, representing in its design the religious history of the world, and is the only one of the kind in existence. Although the foundation stones of this great pile were laid seventy years ago, this grand anthem in stone has not yet reached its "amen," many additions to it being yet in contemplation.

Like many others of earth masterpieces in architecture, it is at once the monument to and the mausoleum of its builder, whose body, according to his dying request, although a Protestant, lies in the vaults beneath his greatest life-work.

Through some halls and corridors back of the grand altar is the chapel of "Our[Pg 64] Lady of the Sacred Heart," which is one of the most beautiful sanctuaries in the city, and remarkable for the harmony of its lines and proportions. It is in the form of a cross, ninety feet in length, eighty-five feet in the transept with an altitude of fifty-five feet. The splendour of its ornamentation, carving, sculpture, elegant galleries, panels in mosaic, original paintings by Canadian artists, and a beautiful reproduction of Raphael's celebrated frieze of "The Dispute of the Blessed Sacrament," unite to constitute this piece of ecclesiastical architecture a chef d'œuvre.

An iconoclast might marvel at the absorption in prayer of some of the devotees, among accessories bewildering to eyes accustomed to the plainer surroundings of other forms of ritual, but the worship of those in attendance seems sincere and complete.

Following the footsteps of Cartier to where, near the foot of Mount Royal, he found the Indian village of Hochelaga, is now to be seen the St. James' Cathedral,[Pg 65] which is a reduced copy of St. Peter's at Rome, the great centre from which radiates the Catholicism of Christendom. It is somewhat less than half the dimensions of its model, with certain modifications necessary in the differences of climate. The work was entrusted to M. Victor Bourgeau, who, to gain the information necessary to carry out successfully a repetition of the great master, Michael Angelo's conception, spent some time in the Eternal City studying the various details. But the real architect, it may be said, who made the plans and supervised and directed the building of the sacred monument, was Rev. Father Michaud, of the St. Viateur Order. To raise the funds necessary for the initial work, every member of the immense diocese was taxed; and even now, after a lapse of thirty years, it is still unfinished, so great has been the expense involved. The handsome façade is elaborately columned in cut-stone, for which only blocks of the most perfect kind were used.[Pg 66]

Like the colossal dome at Rome, this one towers above every other structure in the city, with the height of the cross included, being forty feet higher than the lofty towers of Notre Dame. It is seventy feet in diameter, and two hundred and ten feet above the pavement. It is after the work of Brunelleschi, whose exquisite art and genius flung the airy grace of his incomparable domes against Florentine and Roman skies.

There is none of the "dim, religious light" in the interior decoration of white and gold, the subtle colouring of the symbolic frescoing and the brilliance of the gold and brazen altar furnishing. At a service celebrated especially for the Papal Zuaves, the picturesque red and grey of their uniform, the priests in gorgeous canonicals of scarlet, stiff with gold, the acolytes in white surplices and the venerable archbishop in cardinal and purple, with a chorus from Handel ringing through the vaulted roof, a full conception of the Papal form of worship can be obtained; while a squaw in blanket and[Pg 67] moccasins kneeling on the floor beside a fluted pillar seems the living symbol of the heathendom the early fathers came to convert.

In Canada the Jesuits have always been prominent in its history, signalizing themselves by extraordinary devotion and self-sacrifice, and were among the earliest explorers of the Continent, the first sound of civilization over many of the lakes and rivers being the chant of the capuchined friar. Fathers Brebœuf and Lalemant, burnt by the Indians; Garreau, butchered; Chabanel, drowned by an apostate Huron, and others hideously tortured, testified with their blood to their devotion. From the Atlantic to the prairies, from the bleak shores of the Hudson Bay to the sunny beaches of Louisiana, they suffered, bled and died.

It is said the Jesuits have a genius for selecting sites, and certainly the situation of their especial church and adjoining colleges bears out the statement. Like the other churches of this most Catholic city, it is not complete, the towers having[Pg 68] yet to be continued into spires. It is much frequented for the fine music and admired for its beautiful interior. It is in the Florentine Renaissance style, which is the one usually favoured by this Order. The frescoes are unusually pleasing, being in soft tones of monochrome, the work of eminent Roman artists, and are reproductions of the modern German School of Biblical scenes and from the history of the Jesuits. There are in addition some fine paintings by the Gagliardi brothers at Rome and others.

In the Eastern part of the city, commonly called the French quarter, so purely French are the people, with temperaments as gay and volatile as in Le Beau Paris itself, is a gem of architecture in the church of "Our Lady of Lourdes." This chapel, reared as a visible expression of the dogma of the Immaculate Conception, is of the Byzantine and Renaissance type, a style frequently to be seen reflected from the lagoons of Venice.

"The choir and transepts terminate in a circular domed apsis, and a large central[Pg 69] dome rises at the intersection of the latter. The statue over the altar, and which immediately strikes the eye, is symbolic of the doctrine illustrated. The Virgin is represented in the attitude usually shown in the Spanish School of Painters, with hands crossed upon the breast, standing on a cloud with the words: 'A woman clothed with the sun and the moon under her feet.'" A singularly beautiful light, thrown down from an unseen source, casts a kind of heavenly radiance around the figure with fine effect.

"Some of the painting is exceedingly good. The decoration of the church, in gold and colours, arabesque and fifteenth century ornament, is very beautiful and harmonious. This building is interesting as being the only one of the kind in America."

By descending a narrow stairway, which winds beneath the floor, is found a shrine fitted up in imitation of the grotto near Lourdes, in France, in which it is said the Virgin appeared to a young[Pg 70] girl, Bernadette Souberous, at which time a miracle-working fountain is said to have gushed out of the rock, and still continues its wonderful cures. A goblet of the water stands on the altar, and is said to have powers of healing. This underground shrine, lighted only by dim, coloured lamps, gives a sensation of peculiar weirdness after the light and beauty of the structure above.

Perhaps there is no church of French Canada of deeper interest than[Pg 71] "Notre Dame de Bonsecours." On its site stood the first place of worship built, for which Maisonneuve himself assisted to cut and draw the timbers, some of which are still in existence. The name Bonsecours, signifying succour, was given on account of a narrow escape of the infant colony from the Iroquois. The present building, erected in 1771 on the old foundations, was, until a few years ago, remarkable for its graceful tin roof and finely-pointed spire. The rear having since been altered in a manner entirely out of keeping with the original, which time had "painted that sober hue which makes the antiquity of churches their greatest beauty," much of the charm which made it unique has been destroyed. If it is true that it was an act of piety on the part of a devoted priest, it is another proof that zeal at times outruns correct taste.

The statue of heroic size on the new portion of the edifice, with arms uplifted as if in blessing, was the gift of a noble of Brittany. It was brought over in the[Pg 72] Seventeenth Century, and for two hundred years has been the patron saint of sailors, who ascribe to it miraculous powers. Its ancient pews, the crutches on the walls, and pictures which are among the first works of art brought to the country, suggest the varied scenes which have taken place around the old sanctuary since its doors were first opened for worship.

The ascent of a hundred steps reveals the daintiest and most aerial of chapels above the roof of the church. Tiny coloured windows, designed in lilies and pierced hearts, a microscopic organ, brought from France, no one knows when, and a few rows of seats are the furnishing. The altar, instead of the usual appearance, is a miniature house. Its history is as follows:—"One of the most remarkable events in the history of the Church was the sudden disappearance of the house which had been inhabited by the Holy Family at Nazareth in Galilee. This took place in 1291. As this sacred relic was about to be exposed to the danger of being destroyed by the Saracen infidels,[Pg 73] it was miraculously raised from its foundations and transported by angels to Dalmatia, where, early in the morning, some peasants discovered on a small hill, a house without foundations, half converted into a shrine, and with a steeple like a chapel.

The next day their venerable bishop informed them that Our Lady had appeared to him and said that this house had been carried by angels from Nazareth, and was the same in which she had lived; that the altar had been erected by the apostles, and the statue sculptured in cedar wood had been made by St. Luke. Three years afterwards it again disappeared, its luminous journey being witnessed by some Italian shepherds.

Its present position is about a mile from the Adriatic, at Loretto, just as the angels placed it six hundred years ago. Millions of pilgrims visit it from all parts of the world."

For the aerial chapel of Bonsecours, a fac-simile has been obtained. To render it more sacred it was placed for a period[Pg 74] within the holy house, it touched its walls, and was blessed with holy water in the vessel from which our Lord drank. Such is the alleged history of this shrine, and the peculiar sanctity attached to it.

The extensive convent buildings of the Grey Nuns and other sisterhoods are as numerous as the churches. As the matin bell falls on the ear in the early morning hours, calling to prayers those who have chosen the austerities and serenities of convent life, it recalls to memory the noble band of ladies of the old aristocracy who left châteaux hoary with the traditions of a chivalrous ancestry, and dear with the memories of home, in the company of rough seamen to brave the untried perils of the ocean, a hostile country, homesickness and death, to carry spiritual and bodily healing to the savages. Their followers keep the same vigils now among the sins and sorrows of the bustling city. They glide through the streets with downcast eyes, in sombre robes, wimple and linen coif, bent on missions of church service and errands of mercy, tending the[Pg 75] sick and suffering, and striving to win back human wrecks to a better life.

The various sisterhoods differ in degrees of austerity, the Grey Nuns being one of the least exacting. Their Foundling Hospital, it is said, had its origin in a most touching circumstance. One of the original members of the Order, Madame d'Youville, on leaving the convent gates in the middle of winter, found frozen in the ice of a little stream that then flowed near what is called Foundling street, an infant with a poignard in its heart. Since then tens of thousands of these small outcasts have found sanctuary and tender care within the cloister walls.

The daughter of Ethan Allan, the founder of Vermont, died a member of this Order.

The Carmelites are the most rigid in their requirements of service. They are small numerically and live behind high walls, and renounce forever the sight of the outside world, never leaving their cloister, and being practically dead to home and friends, sleeping, it is said, in their own coffins.[Pg 76]

Instances have been known of a sister's assuming vows of special severity, as in the case of Jean Le Ber, of the Congregation de Notre Dame, a daughter of a merchant in the town, who voluntarily lived in solitary confinement from the year 1695 to 1714—nineteen years of self-immolation, when her couch was a pallet of straw, and her prayers and fastings unceasing. She denied herself everything that to us would make life desirable or even endurable—sacrificed the dearest ties of kindred, and pursued with intense fervour the self-imposed rigours of her vocation. Yet, it was not that in her nature she had no love for beauty nor craving for pleasure, for in the sacristy of the Cathedral, carefully preserved in a receptacle in which are kept the vestments of the clergy, are robes ornamented by her needle that are simply marvels of colour, design and exquisite finish. The modern robes, though gorgeous in richly-piled velvet from the looms of Lyons, heavy with gold work and embroidered with angels and figures so exquisitely wrought as to look as if[Pg 77] painted on ivory, yet do not compare with that done by the fingers that were worn by asceticism within the walls of her cell. In the spare form, clad in thread-bare garments, there must have been crushed down a gorgeously artistic nature which found visible expression in the beautifully adorned chasubles of the priests and altar cloths, which are solid masses of delicate silken work on a ground of fine silver threads, the colours and lustre of which seem unimpaired by time. Six generations of priests have performed the sacrifice of the mass in these marvellously beautiful robes, the incense from the swaying censors of two hundred years have floated around them in waves of perfume. The taste and skill with which high-born ladies of that time wrought tapestries to hang on their castle walls were consecrated by her to religion, in devoting to the Church, work which was fit to adorn the royal drapings of a Zenobia.

Without the magnificence which distinguishes the cathedrals, some of the rural shrines are full of interest. The church[Pg 78] of Ste. Anne's, an old building near the western end of the island, and one of the oldest sacerdotal edifices in America, has around it a halo of romance and piety since the fur-trading days, being the last church visited by the voyageurs and their last glimpse of civilization before facing the dangers of the pathless wilderness of the West. At its altar these rough, half-wild men knelt to pray and put themselves under the protection of their titular Sainte Anne.

The Trappists, though rarely seen outside the walls of their retreat, look precisely as did mediæval monks of centuries ago, with whose appearance we are familiar in pictures of Peter the Hermit and other zealots, who with their fiery eloquence sent the Armies of Christendom to fight for the Holy Sepulchre. They dress in a coarse brown gown and cowl, with a girdle of rope, and are under vows of perpetual silence. They live on frugal meals of vegetables and fruit twice a day, have the head tonsured, and feet bare in sandals. The continued fasts, severe flagellations, labours and meditations[Pg 79] of those anchorites make the regulations governing this order exceedingly strict, and recall the times when kings and emperors, in the same monkish garb, walked barefoot to knock humbly in penance at monastery gates.

Perhaps the most unique shrine in the province is that of Mount Rigaud, on the banks of the Ottawa, not far from the spot where Dollard and his band of Christian knights lay down their lives. The mountain is regarded with much superstition by the ignorant, on account of its peculiar and unaccountable natural phenomena, whose origin has puzzled the most learned scientists to account for. The wooded mountain is crowned by what is called "The Field of Stones," or "The Devil's Garden," from a deposit of almost spherical boulders, of so far unmeasured depth, which cover its surface. Encircled by trees and verdure, this strange formation of several acres in extent is composed mainly of rock different from the mass of the mountain, which belongs to the same family as the igneous mountains of the neighbouring region.[Pg 80] What were the causes and conditions which carried this strange material to the top of this elevation will, when they are explained, be of intense interest. It is said that the only other deposit similar, though smaller in extent, is in Switzerland. Perhaps some ancient glacier, through eons of time, gradually melted here, and slowly deposited the drift it had borne from regions far away.

A bold spur of the hill has been converted into a shrine, adorned with images, while on the bare rough sides of the lichen-covered rocks have been inscribed in large white letters the words "Penitence—Penitence." At regular intervals on the stony road approaching it are what are called the "Stations of the Cross." They are fourteen in number, being little chapels made from the uncut stones of the "Devil's Garden." The floors of these, on which the penitents kneel before pictures of the "Passion," are covered with sand and coarse gravel.

The conquest of Canada in 1759 by the English differed from that of Britain by the[Pg 81] Norman French in 1066, in that here the vanquished were allowed to retain their language, customs and full religious liberties, so that, after a lapse of one hundred and fifty years, the Papal service is solemnized with all the pomp and ceremonial of the Vatican, and in the courts, the Quebec Legislature and in Society is heard the euphonic French speech, and, outside of Rome, Canada is considered the chief bulwark of Papacy.

The conquest and settlement of all new regions are necessarily more or less written in blood, and the natural characteristics of the North American Indian have caused much of the early history of Canada to be traced in deeds of horror and agony lighted by the torture fire, with sufferings the most exquisite of which the human mind can conceive. When these were inflicted on individuals, it was sufficiently heartrending, but when a whole community fell a victim to their ferocity, as was the case in what is called "The Massacre of Lachine," the details are too horrible for even the imagination to dwell upon. Standing on the river bank, or "shooting" the rapids in the steamer, with the green shores as far as the eye can reach dotted with villages and villas, the wonderful bridges spanning the stream, and beyond, the great city with its domes and spires, it can scarcely be realized that for two days[Pg 83] and two nights the spot was a scene of the most revolting carnage. It was an evening in the summer of 1689. In spite of a storm of wind and rain which broke over the young settlement, the fields of grain and meadows looked cheerful and thrifty. In each cabin home the father had returned from the day's toil in the harvest field and was sitting by the fireside, where the kettle sang contentedly. The mother sat spinning or knitting, and perhaps singing a lullaby, as she rocked the cradle, little recking that ere the morning dawned the hamlet would lie in ashes, and the tomahawk of the Indian be buried in her babies' hearts; but such was the case, for after forty-eight hours of fiendish cruelty, death and desolation reigned for miles along the shores. Where the blue smoke had curled up among the trees were only the smoking ruins of hearths and homes, surrounded with sights and suggestions of different forms of death, which even the chronicler, two hundred years after, is fain to pass by in shuddering silence.

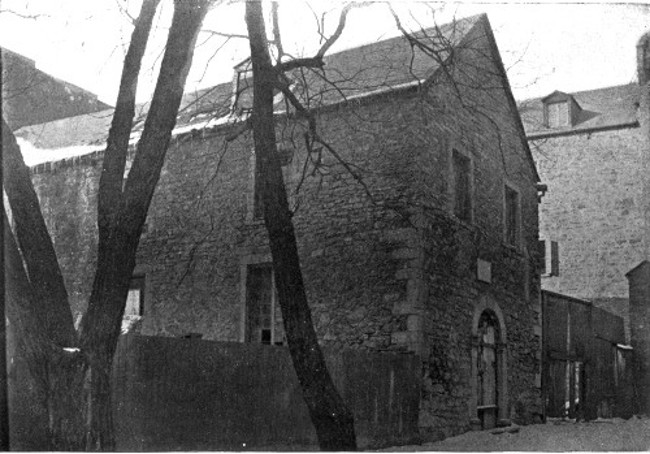

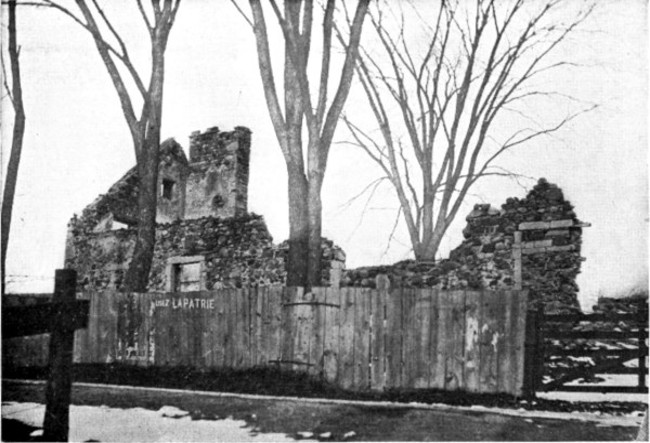

The crumbling remains of a fortified[Pg 84] seigniorial château, within sight of the Rapids of Lachine, a tradition asserts, was in the year 1668 the home of La Salle, who was one of the most excellent men of his day. Leaving his fair demesne, which the Sulpicians had conferred upon him, and the home which to-day is slowly falling to decay among the apple-orchards along the river side, he too followed his thirst for adventure into untrodden fields.

There is a well-founded legend that the old chimney attached thereto was built by Champlain in his trading post of logs. It is of solid masonry, and is sixty years older than the walls which surround it. The wide fireplace has a surface of fifty square feet, and is the most interesting piece of architecture in all Canada. The snowflakes of almost three hundred winters have fallen into its cavernous depths since these stones and mortar were laid. When Champlain stood by its hearth, as its first blaze, lighted by tinder and flint, roared up to the sky—William Shakespeare was still writing his sublime lines, Queen Elizabeth had lain but twelve years in her marble tomb, and the Château de Ramezay was not to be built for a hundred years to come. Often in the two years during which it had for La Salle the sacredness of the home fireside, its light must have fallen on his handsome young face, and flowing curls, as he laid out plans for his palisaded village, and dreamt of the golden lands towards the setting sun. He was a true patriot, and literally gave his life for the advancement of his country, being murdered in the Lower Mississippi by one of his own men while endeavouring to extend its territory.

HOME OF LA SALLE.

HOME OF LA SALLE.Posterity is not true to the memory of these great pioneers, for the elements beat upon the roofless timbers, the north wind sweeps the hearth that is mouldering under the rains and sunshine of the skies they loved. In another generation all that can be said will be—here once stood the historic stones of the ancient fireside of the heroes who won the wilderness for those who have allowed this monument of their fortitude and self-sacrifice to crumble into dust.[Pg 86]

La Salle had heard from some stray bands of Seneca Indians, who had visited his post at Lachine, of a great river that flowed from their hunting grounds to the sea. Imagining it would open his way to find the route to the golden Ind, he sold his grant at Lachine, and in company with two priests from the Seminary at Montreal, and some Senecas as guides, started on July 6th, 1669. With visions of finding for France a clime of warmer suns and more rich in silver and gold than Canada, he pushed on. The priests on their return[Pg 87] brought back nothing of any value except the first map procured of the upper lake region.

One of the most enthusiastic fellow travelers of La Salle was a Franciscan, Father Hennepin. They crossed the ocean from France together, and probably beguiled many an hour of the long voyage in relating their dreams of finding the treasures hidden in the land to which the prow of the vessel pointed.

Hennepin also penetrated to the Mississippi, reaching in his wanderings a beautiful fall foaming between its green bluffs which he named St. Anthony, on which spot now stands the "Flour City," Minneapolis, in the county of Hennepin, Minnesota. He probably heard of the other falls, five miles away, which we know as Minnehaha, and around which the sweetest of American poets has woven the witchery of Indian legend in the wooing of "Hiawatha." It seems almost incredible that where are now the largest flour mills in the world, turning out daily about 40,000 barrels, there was, scarcely fifty years ago, only[Pg 88] the cedar strewn wigwam and smoke of the camp fire, the tread of moccasined feet and the dip of the paddles by the bark canoe.

Near by Place d'Armes Square may be seen a grey stone house on which is written "Here lived Sieur DuLuth." He was a leading spirit among the young men of the town, who gathered around his fireside to listen to his thrilling tales of adventure, and of his early life when he was a gendarme in the King's Guard. Coming to Canada in the year 1668, he explored among the Sioux tribes of the Western plains. He was one of the first Frenchmen to approach the sources of the Mississippi. The city of Duluth in Minnesota received its name from him. A tablet on a modern building in the same locality informs the passer-by that Cadillac, who founded the City of Detroit about the same time as the Château de Ramezay was built, spent the last years of his wandering life on this spot.

The town of Varennes, down the river, is called from the owner of a Seigniory in[Pg 89] the forest, le Chevalier Gauthier de la Vérandrye, a soldier and a trader, who was the first to explore the great Canadian North-West, and to discover the "Rockies." He was an undaunted and fearless traveler, establishing post after post, as far as the wild banks of the Saskatchewan and even further north, which, in giving to France, he ultimately gave to Canada.

The traditions connected with the Château de Ramezay are scarcely more interesting than those surrounding many spots in the vicinity. Incorporated in this prosaic, business part of the city are many an old gable or window, which were once part of some mediæval chapel or home of these early times. On the other side of Notre Dame street, where now stands the classic and beautiful pile called the City Hall, were to be seen in those days the church and "Habitation," as it was called, of the Jesuit Fathers, within whose walls lived many learned sons of Loyola, Charlevoix among others. They were burnt down in 1803,[Pg 90] at the same time as the Château de Vaudreuil was destroyed, by one of the disastrous fires which have so frequently swept the cities of Montreal and Quebec, and in which many quaint historical structures disappeared. About a mile to the west is still standing the family residence of Daniel Hyacinthe, Marie Liénard de Beaujeu, the hero of the Monongahela, at which battle George Washington was an officer.

It was a lamentable event, the indiscriminate slaughter of three thousand men through the stupidity and incredible obstancy[Pg 91] of General Braddock, who, like Dieskau at a subsequent time, despising the counsel of those familiar with Indian methods of warfare, determinedly followed his own plans.

Washington in this engagement held the rank of Adjutant-General of Virginia. "His business was to inform the French that they were building forts on English soil, and that they would do well to depart peaceably."

Beaujeu was sent at the head of a force composed of French soldiers and Indian allies to answer the Briton with the powerful argument of force of arms.