|

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Cedar Creek, by Elizabeth Hely Walshe

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net

Title: Cedar Creek

From the Shanty to the Settlement

Author: Elizabeth Hely Walshe

Release Date: January 26, 2010 [EBook #31091]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK CEDAR CREEK ***

Produced by Delphine Lettau and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Canada Team at http://www.pgdpcanada.net

|

|

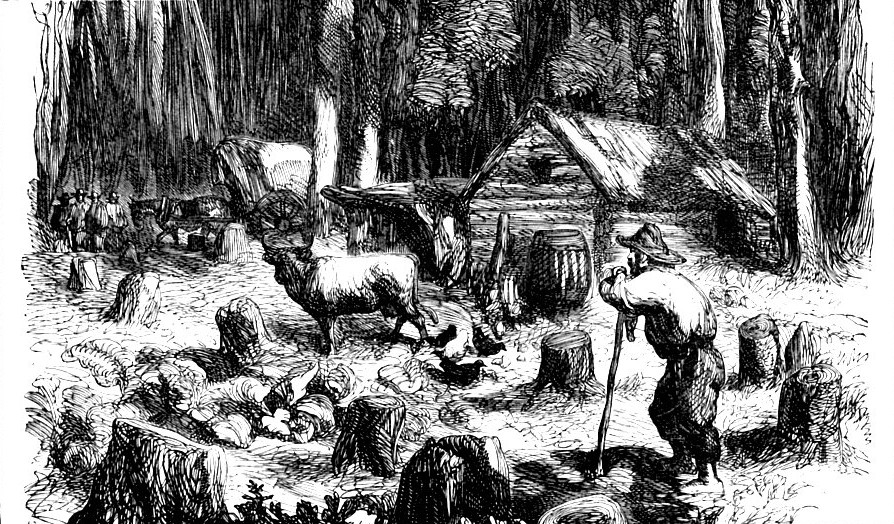

ANDY HELPS THE INDIAN SQUAW TO CONSTRUCT THE WIGWAM.—Page 225. Click to ENLARGE |

| CONTENTS. | |

| CHAPTER | |

| I. | WHY ROBERT WYNN EMIGRATED |

| II. | CROSSING THE 'FERRY' |

| III. | UP THE ST. LAWRENCE |

| IV. | WOODEN-NESS |

| V. | DEBARKATION |

| VI. | CONCERNING AN INCUBUS |

| VII. | THE RIVER HIGHWAY |

| VIII. | 'JEAN BAPTISTE' AT HOME |

| IX. | 'FROM MUD TO MARBLE' |

| X. | CORDUROY |

| XI. | THE BATTLE WITH THE WILDERNESS BEGINS |

| XII. | CAMPING IN THE BUSH |

| XIII. | THE YANKEE STOREKEEPER |

| XIV. | THE 'CORNER' |

| XV. | ANDY TREES A 'BASTE' |

| XVI. | LOST IN THE WOODS |

| XVII. | BACK TO CEDAR CREEK |

| XVIII. | GIANT TWO-SHOES |

| XIX. | A MEDLEY |

| XX. | THE ICE-SLEDGE |

| XXI. | THE FOREST-MAN |

| XXII. | SILVER SLEIGH-BELLS |

| XXIII. | STILL-HUNTING |

| XXIV. | LUMBERERS |

| XXV. | CHILDREN OF THE FOREST |

| XXVI. | ON A SWEET SUBJECT |

| XXVII. | A BUSY BEE |

| XXVIII. | OLD FACES UPON NEW NEIGHBOURS |

| XXIX. | ONE DAY IN JULY |

| XXX. | VISITORS AND VISITED |

| XXXI. | SUNDAY IN THE FOREST |

| XXXII. | HOW THE CAPTAIN CLEARED HIS BUSH |

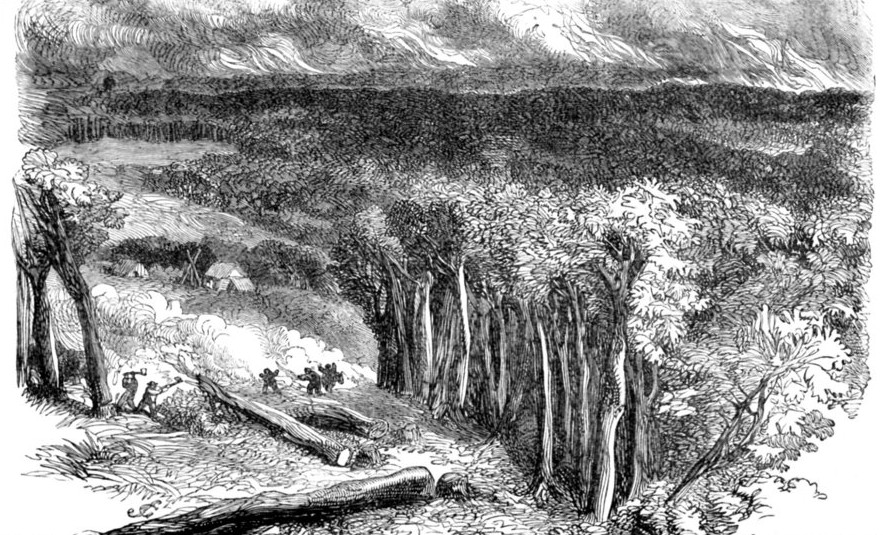

| XXXIII. | THE FOREST ON FIRE |

| XXXIV. | TRITON AMONG MINNOWS |

| XXXV. | THE PINK MIST |

| XXXVI. | BELOW ZERO |

| XXXVII. | A CUT, AND ITS CONSEQUENCES |

| XXXVIII. | JACK-OF-ALL-TRADES |

| XXXIX. | SETTLER THE SECOND |

| XL. | AN UNWELCOME SUITOR |

| XLI. | THE MILL-PRIVILEGE |

| XLII. | UNDER THE NORTHERN LIGHTS |

| XLIII. | A BUSH-FLITTING |

| XLIV. | SHOVING OF THE ICE |

| XLV. | EXEUNT OMNES |

[7]

One of the cabs pursuing each other along the lamplit streets, and finally diverging among the almost infinite ramifications of London thoroughfares, contains a young man, who sits gazing through the window at the rapidly passing range of houses and shops with curiously fixed vision. The face, as momentarily revealed by the beaming of a brilliant gaslight, is chiefly remarkable for clear dark eyes rather deeply set, and a firm closure of the lips. He scarcely alters[8] his posture during the miles of driving through wildernesses of brick and stone: some thoughts are at work beneath that broad short brow, which keep him thus still. He has never been in London before. He has come now on an errand of hope and endeavour, for he wants to push himself into the army of the world's workers, somewhere. Prosaically, he wants to earn his bread, and, if possible, butter wherewith to flavour it. Like Britons in general, from Dick Whittington downwards, he thinks that the capital is the place in which to seek one's fortune, and to find it. He had not expected streets paved with gold, nor yet with the metaphorical plenty of penny loaves; but an indefinite disappointment weighs upon him as he passes through quarters fully as dingy and poverty-stricken as those in his own provincial town.

Still on—on—across 'the province covered with houses;' sometimes in a great thoroughfare, where midnight is as noisy as noon-day, and much more glaring; sometimes through a region of silence and sleep, where gentility keeps proper hours, going to bed betimes in its respectable streets. Robert Wynn began to wonder when the journey would end; for, much as he knew of London by hearsay and from books, it was widely different thus personally to experience the metropolitan amplitude. A slight dizziness of sight, from the perpetual sweeping past of lamps and shadowy buildings, caused him to close his eyes; and from speculations on the possible future and the novel present, his thoughts went straight home again.

Home to the Irish village where his ancestors had long been lords of the soil; and the peasantry had deemed that the greatest power on earth, under[9] majesty itself, was his Honour Mr. Wynn of Dunore, where now, fallen from greatness, the family was considerably larger than the means. The heavily encumbered property had dropped away piece by piece, and the scant residue clung to its owner like shackles. With difficulty the narrow exchequer had raised cash enough to send Robert on this expedition to London, from which much was hoped. The young man had been tolerably well educated; he possessed a certain amount and quality of talent, extolled by partial friends as far above the average; but the mainstay of his anticipations was a promise of a Civil Service appointment, obtained from an influential quarter; and his unsophisticated country relatives believed he had only to present himself in order to realize it at once.

He was recalled to London by the sudden stoppage of the cab. On the dim lamp over a doorway was stained the name of the obscure hotel to which he had been recommended as central in situation, while cheap in charges. Cabby's fare was exorbitant, the passenger thought; but, after a faint resistance, Mr. Wynn was glad to escape from the storm of h-less remonstrances by payment of the full demand, and so entered the coffee-room.

It was dingy and shabby-genteel, like the exterior; a quarter of a century might have elapsed since the faded paper had been put up, or a stroke of painting executed, in that dispiriting apartment. Meanwhile, all the agencies of travel-stain had been defacing both. An odour of continual meal-times hung about it; likewise of smoke of every grade, from the perfumed havanna to the plebeian pigtail. The little tables[10] were dark with hard work and antiquity; the chair seats polished with innumerable frictions. A creeping old waiter, who seemed to have known better days in a higher-class establishment, came to receive the new-comer's orders; and Robert sat down to wait for his modest chop and glass of ale.

That morning's Times lay on his table: he glanced over the broad sheet of advertisements—that wondrous daily record of need and of endeavour among the toiling millions of London. The inexplicable solitude in a crowd came about the reader's heart: what a poor chance had a provincial stranger amid the jostling multitude all eager for the prizes of comfort and competence! Robert went back for anchor to one strong fact. The Honourable Mr. Currie Faver, Secretary to the Board of Patronage, had declared to the member for the Irish county of C——, on the eve of an important division, that his young friend should have the earliest appointment at his disposal in a certain department. Robert Wynn felt an inward gratulation on the superiority of his auspices. True, the promise made in January yet remained due in July; but there were numberless excellent good reasons why Mr. Currie Faver had been as yet unable to redeem his pledge.

Robert turned his paper to look for the news: a paragraph in the corner arrested his attention.

'We learn from the best authority that, owing to the diminution of business consequent upon recent Acts of the Legislature, it is the intention of Her Majesty's Commissioners of Public Locomotion to reduce their staffs of officials, so that no fresh appointments can be made for some months.'[11]

He gazed at this piece of intelligence much longer than was necessary for the mere reading of it. The Board of Public Locomotion was the very department in which he had been promised a clerkship. Robert made up his mind that it could not be true; it was a mere newspaper report: at all events, Mr. Currie Faver was bound by a previous pledge; whoever remained unappointed, it could not be a friend of the hon. member for C——.

There were voices in the next compartment, and presently their conversation was forced on Mr. Wynn's attention by the strongly stated sentiment, 'The finest country in the world—whips all creation, it does.'

Some rejoinder ensued in a low tone.

'Cold!' with a rather scornful accent, 'I should think so. Gloriously cold! None of your wet sloppy winters and foggy skies, but ice a yard and a half thick for months. What do you think of forty degrees below zero, stranger?'

Robert could fancy the other invisible person shrugging his shoulders.

'Don't like it, eh? That's just a prejudice here in the old country; natural enough to them that don't know the difference. When a man hears of seventy degrees below the freezing-point, he's apt to get a shiver. But there, we don't mind it; the colder the merrier: winter's our time of fun: sleighing and skating parties, logging and quilting bees, and other sociabilities unknown to you in England. Ay, we're the finest people and the finest country on earth; and since I've been to see yours, I'm the steadier in that opinion.'

'But emigrants in the backwoods have so few of[12] the comforts of civilisation,' began the other person, with a weak, irresolute voice.

'Among which is foremost the tax-gatherer, I suppose?' was the triumphant rejoinder. 'Well, stranger, that's an animal I never saw in full blow till I've been to the old country. I was obliged to clear out of our lodgings yesterday because they came down on the furniture for poor-rate. Says I to the landlady, who was crying and wringing her hands, "Why not come to the country where there's no taxes at all, nor rent either, if you choose?" Then it would frighten one, all she counted up on her fingers—poor-rate, paving-rate, water-rate, lighting, income-tax, and no end of others. I reckon that's what you pay for your high civilisation. Now, with us, there's a water privilege on a'most every farm, and a pile of maple-logs has fire and gaslight in it for the whole winter; and there's next to no poor, for every man and woman that's got hands and health can make a living. Why, your civilisation is your misfortune in the old country; you've got to support a lot of things and people besides yourself and your family.'

'Surely you are not quite without taxes,' said the other.

'Oh, we lay a trifle on ourselves for roads and bridges and schools, and such things. There's custom-houses at the ports; but if a man chooses to live without tea or foreign produce, he won't be touched by the indirect taxes either. I guess we've the advantage of you there. You can't hardly eat or drink, or walk or ride, or do anything else, without a tax somewhere in the background slily sucking your pocket.'[13]

'A United States citizen,' thought Robert Wynn. 'What a peculiar accent he has! and the national swagger too.' And Mr. Wynn, feeling intensely British, left his box, and walked into the midst of the room with his newspaper, wishing to suggest the presence of a third person. He glanced at the American, a middle-aged, stout-built man, with an intelligent and energetic countenance, who returned the glance keenly. There was something indescribably foreign about his dress, though in detail it was as usual; and his manner and air were those of one not accustomed to the conventional life of cities. His companion was a tall, pale, elderly person, who bore his piping voice in his appearance, and seemed an eager listener.

'And you say that I would make an independence if I emigrated?' asked the latter, fidgeting nervously with a piece of paper.

'Any man would who has pluck and perseverance. You would have to work hard, though;' and his eyes fell on the white irresolute hands, dubious as to the requisite qualities being there indicated. 'You'd want a strong constitution if you're for the backwoods.'

'The freedom of a settler's life, surrounded by all the beauties of nature, would have great charms for me,' observed the other.

'Yes,' replied the American, rather drily; 'but I reckon you wouldn't see many beauties till you had a log shanty up, at all events. Now that young man'—he had caught Robert Wynn's eye on him again—'is the very build for emigration. Strong, active, healthy, wide awake: no offence, young gentleman, but such as you are badly wanted in Canada West.'[14]

From this began a conversation which need not be minutely detailed. It was curious to see what a change was produced in Robert's sentiments towards the settler, by learning that he was a Canadian, and not a United States man: 'the national swagger' became little more than a dignified assertion of independence, quite suitable to a British subject; the accent he had disliked became an interesting local characteristic. Mr. Hiram Holt was the son of an English settler, who had fixed himself on the left bank of the Ottawa, amid what was then primeval forest, and was now a flourishing township, covered with prosperous farms and villages. Here had the sturdy Saxon struggled with, and finally conquered, adverse circumstances, leaving his eldest son possessed of a small freehold estate, and his other children portioned comfortably, so that much of the neighbourhood was peopled by his descendants. And this, Hiram's first visit to the mother country—for he was Canadian born—was on colonial business, being deputed from his section of the province, along with others, to give evidence, as a landed proprietor, before the Secretary of State, whose gate-lodge his father would have been proud to keep when he was a poor Suffolk labourer.

'Now there's an injustice,' quoth Mr. Holt, diverging into politics. 'England has forty-three colonies, and but one man to oversee them all—a man that's jerked in and out of office with every successive Ministry, and is almost necessarily more intent on party manœuvres than on the welfare of the young nations he rules. Our colony alone—the two Canadas—is bigger than Great Britain and Ireland three times[15] over. Take in all along Vancouver's Island, and it's as big as Europe. There's a pretty considerable slice of the globe for one man to manage! But forty-two other colonies have to be managed as well; and I guess a nursery of forty-three children of all ages left to one care-taker would run pretty wild, I do.'

'Yet we never hear of mismanagement,' observed Robert, in an unlucky moment; for Mr. Hiram Holt retained all the Briton's prerogative of grumbling, and in five minutes had rehearsed a whole catalogue of colonial grievances very energetically.

'Then I suppose you'll be for joining the stars and stripes?' said the young man.

'Never!' exclaimed the settler. 'Never, while there's a rag of the union jack to run up. But it's getting late;' and as he rose to his feet with a tremendous yawn, Robert perceived his great length, hitherto concealed by the table on which he leaned. 'This life would kill me in six months. In my own place I'm about the farm at sunrise in summer. Never knew what it was to be sick, young man.' And so the party separated; Robert admiring the stalwart muscular frame of the Canadian as he strode before him up the stairs towards their sleeping-rooms. As he passed Mr. Holt's door, he caught a glimpse of bare floor, whence all the carpets had been rolled off into a corner, every vestige of curtain tucked away, and the window sashes open to their widest. Subsequently he learned that to such domestic softnesses as carpets and curtains the sturdy settler had invincible objections, regarding them as symptoms of effeminacy not suitable to his character, though admitting that for women they were well enough.[16]

Robert was all night felling pines, building log-huts, and wandering amid interminable forests; and when his shaving water and boots awoke him at eight, he was a little surprised to find himself a denizen of a London hotel. Mr. Holt had gone out hours before. After a hasty breakfast Mr. Wynn ordered a cab, and proceeded to the residence of the hon. member for C—— county.

It was a mansion hired for the season in one of the fashionable squares; for so had the hon. member's domestic board of control, his lady-wife and daughters, willed. Of course, Robert was immensely too early; he dismissed the cab, and wandered about the neighbourhood, followed by suspicious glances from one or two policemen, until, after calling at the house twice, he was admitted into a library beset with tall dark bookcases. Here sat the M.P. enjoying the otium cum dignitate, in a handsome morning gown, with bundles of parliamentary papers and a little stack of letters on the table. But none of the legislative literature engrossed his attention just then: the Morning Post dropped from his fingers as he arose and shook hands with the son of his constituent.

'Ah, my dear Wynn—how happy—delighted indeed, I assure you. Have you breakfasted? all well at home? your highly honoured father? late sitting at the House last night—close of the session most exhausting even to seasoned members, as the Chancellor of the Exchequer said to me last evening in the lobby;' and here followed an anecdote. But while he thus ran on most affably, the under-current of idea in his mind was somewhat as follows: 'What on earth does this young fellow want of me? His family[17] interest in the county almost gone—not worth taking pains to please any longer—a great bore—yet I must be civil;—oh, I recollect Currie Paver's promise—thinks he has given me enough this session'—

Meanwhile, Robert was quite interested by his agreeable small talk. It is so charming to hear great names mentioned familiarly by one personally acquainted with them; to learn that Palmerston and Lord John can breakfast like ordinary mortals. By and by, with a blush and a falter (for the mere matter of his personal provision for life seemed so paltry among these world-famed characters and their great deeds, that he was almost ashamed to allude to it), Robert Wynn ventured to make his request, that the hon. member for C—— would go to the hon. Secretary of the Board of Patronage, and claim the fulfilment of his promise. Suddenly the M.P. became grave and altogether the senator, with his finger thoughtfully upon his brow—the identical attitude which Grant had commemorated on canvas, beaming from the opposite wall.

'An unfortunate juncture; close of the session, when everybody wants to be off, and Ministers don't need to swell their majorities any longer. I recollect perfectly to what you allude; but, my dear young friend, all these ministerial promises, as you term them, are more or less conditional, and it may be quite out of Mr. Currie Paver's power to fulfil this.'

'Then he should not have made it, sir,' said Robert hotly.

'For instance,' proceeded the hon. gentleman, not noticing the interruption, 'the new arrangements of the Commissioners renders it almost impossible that[18] they should appoint to a clerkship, either supernumerary or otherwise, while they are reducing the ordinary staff. But I'll certainly go to Mr. Faver, and remind him of the circumstance: we can only be refused at worst. You may be assured of my warmest exertions in your behalf: any request from a member of your family ought to be a command with me, Mr. Wynn.'

Robert's feelings of annoyance gave way to gratification at Mr. A——'s blandness, which, however, had a slight acid behind.

'And though times are greatly altered, I don't forget our old electioneering, when your father proposed me on my first hustings. Greatly altered, Mr. Wynn; greatly altered. I must go to the morning sitting now, but I'll send you a note as to the result of my interview. You must have much to see about London. I quite envy you your first visit to such a world of wonders; I am sure you will greatly enjoy it. Good morning, Mr. Wynn. I hope I shall have good news for you.'

And so Robert was bowed out, to perambulate the streets in rather bitter humour. Was he to return to the poor, scantily supplied home, and continue a drag on its resources, lingering out his days in illusive hopes? Oh that his strong hands and strong heart had some scope for their energies! He paused in one mighty torrent of busy faces and eager footsteps, and despised himself for his inaction. All these had business of one kind or other; all were earnestly intent upon their calling; but he was a waif and a straw on the top of the tide, with every muscle stoutly strung, and every faculty of his brain clear[19] and sound. Would he let the golden years of his youth slip by, without laying any foundation for independence? Was this Civil Service appointment worth the weary waiting? Emigration had often before presented itself as a course offering certain advantages. Mr. Holt's conversation had brightened the idea. For his family, as well as for himself, it would be beneficial. The poor proud father, who had frequently been unable to leave his house for weeks together, through fear of arrest for debt, would be happier with an ocean between him and the ancestral estates, thronged with memories of fallen affluence: the young brothers, Arthur and George, who were nearing man's years without ostensible object or employment, would find both abundantly in the labour of a new country and a settler's life. Robert had a whole picture sketched and filled in during half an hour's sit in the dingy coffee-room; from the shanty to the settlement was portrayed by his fertile fancy, till he was awakened from his reverie by the hearty voice of Hiram Holt.

'I thought for a minute you were asleep, with your hat over your eyes. I hope you're thinking of Canada, young man?'

Robert could not forbear smiling.

'Now,' said Mr. Holt, apparently speaking aloud a previous train of thought, 'of all things in this magnificent city of yours, which I'm free to confess beats Quebec and Montreal by a long chalk, nothing seems queerer to me than the thousands of young men in your big shops, who are satisfied to struggle all their lives in a poor unmanly way, while our millions of acres are calling out for hands to fell the[20] forests and own the estates, and create happy homes along our unrivalled rivers and lakes. The young fellow that sold me these gloves'—showing a new pair on his hands—'would make as fine a backwoodsman as I ever saw—six feet high, and strong in proportion. It's the sheerest waste of material to have that fellow selling stockings.'

But Mr. Holt found Robert Wynn rather taciturn; whereupon he observed: 'I'm long enough in the world young man, to see that to-day's experience, whatever it has been, has bated your hopes a bit; the crest ain't so plumy as last night. But I say you'll yet bless the disappointment, whatever it is, that forces you over the water to our land of plenty. Come out of this overcrowded nation, out where there's elbow-room and free breathing. Tell you what, young man, the world doesn't want you in densely packed England and Ireland, but you're wanted in Canada, every thew and sinew that you have. The market for such as you is overstocked here: out with us you'll be at a premium. Don't be offended if I've spoke plain, for Hiram Holt is not one of them that can chop a pine into matches: whatever I am thinking, out with the whole of it. But if you ever want a friend on the Ottawa'—

Robert asserted that he had no immediate idea of emigration; his prospects at home were not bad, etc. He could not let this rough stranger see the full cause he had for depression.

'Not bad! but I tell you they're nothing compared to the prospects you may carve out for yourself with that clever head and those able hands.' Again Mr. Holt seized the opportunity of dilating on the[21] perfections of his beloved colony: had he been a paid agent, he could not have more zealously endeavoured to enlist Robert as an emigrant. But it was all a product of national enthusiasm, and of the pride which Canadians may well feel concerning their magnificent country.

Next morning a few courteous lines from the hon. member for C—— county informed Mr. Wynn, with much regret, that, as he had anticipated, Mr. Currie Faver had for the present no nomination for the department referred to, nor would have for at least twelve months to come.

'Before which time, I trust,' soliloquized Robert a little fiercely, 'I shall be independent of all their favours.' And amidst some severe reflections on the universal contempt accorded to the needy, and the corrupted state of society in England, which estimates a man by the length of his purse chiefly, Robert Wynn formed the resolution that he would go to Canada.

[22]

About a month after his meeting with Hiram Holt in the London coffee-house, he and his brother Arthur found themselves on board a fine emigrant vessel, passing down the river Lee into Cork harbour, under the leadership of a little black steam-tug. Grievous had been the wailing of the passengers at parting with their kinsfolk on the quay; but, somewhat stilled by this time, they leaned in groups on the bulwarks, or were squatted about on deck among their infinitude of red boxes and brilliant tins, watching the villa-whitened shores gliding by rapidly. Only an occasional vernacular ejaculation, such as 'Oh, wirra! wirra!' or, 'Och hone, mavrone!' betokened the smouldering remains[23] of emotion in the frieze coats and gaudy shawls assembled for'ard: the wisest of the party were arranging their goods and chattels 'tween-decks, where they must encamp for a month or more; but the majority, with truly Celtic improvidence, will wait till they are turned down at nightfall, and have a general scramble in the dusk.

Now the noble Cove of Cork stretches before them, a sheet of glassy water, dotted with a hundred sail, from the base of the sultry hill faced with terraces and called Queenstown, to the far Atlantic beyond the Heads. Heavy and dark loom the fortified Government buildings of Haulbowline and the prisons of Spike Island, casting forbidding shadows on the western margin of the tide. Quickly the steam-tug and her follower thread their way among islets and moored barques and guard-ships, southward to the sea. No pause anywhere; the passengers of the brig Ocean Queen are shut up in a world of their own for a while; yet they do not feel the bond with mother country quite severed till they have cleared the last cape, and the sea-line lies wide in view; nor even then, till the little black tug casts off the connecting cables, and rounds away back across the bar, within the jaws of the bay.

Hardly a breath of breeze: but such as blows is favourable; and with infinite creaking all sail is set. The sound wakes up emigrant sorrow afresh; the wildly contagious Irish cry is raised, much to the discomposure of the captain, who stood on the quarterdeck with Robert Wynn.

'The savages! they will be fitting mates for Red Indians, and may add a stave or two to the[24] war-whoop. One would think they were all going to the bottom immediately.' He walked forward to quell the noise, if possible, but he might as well have stamped and roared at Niagara. Not a voice cared for his threats or his rage, but those within reach of his arm. The choleric little man had to come back baffled.

'Masther Robert, would ye like 'em to stop?' whispered a great hulking peasant who had been looking on; 'for if ye would, I'll do it while ye'd be taking a pinch of snuff.'

Andy Callaghan disappeared somewhere for a moment, and presently emerged with an old violin, which he began to scrape vigorously. Even his tuning was irresistibly comical; and he had not been playing a lively jig for ten minutes, before two or three couples were on their feet performing the figure. Soon an admiring circle, four deep, collected about the dancers. The sorrows of the exiles were effectually diverted, for that time.

'A clever fellow,' quoth the captain, regarding Andy's red hair and twinkling eyes with some admiration. 'A diplomatic tendency, Mr. Wynn, which may be valuable. Your servant, I presume?'

'A former tenant of my father's, who wished to follow our fortunes,' replied Robert. 'He's a faithful fellow, though not much more civilised than the rest.'

That grand ocean bluff, the Old Head of Kinsale, was now in the offing, and misty ranges of other promontories beyond, at whose base was perpetual foam. Robert turned away with a sigh, and descended to the cabins. In the small square box allotted to them, he found Arthur lying in his berth, reading Mrs. Traill's Emigrant's Guide.[25]

'I've been wondering what became of you; you've not been on deck since we left Cork.'

'Of course not. I should have been blubbering like a schoolboy; and as I had enough of that last night, I mean to stay here till we're out of sight of land.'

Little trace of the stoicism he professed was to be seen in the tender eyes which had for an hour been fixed on the same page; but Arthur was not yet sufficiently in manhood's years to know that deep feeling is an honour, and not a weakness.

Towards evening, the purple mountain ranges of Kerry were fast fading over the waters; well-known peaks, outlines familiar from childhood to the dwellers at Dunore, were sinking beneath the great circle of the sea. Cape Clear is left behind, and the lonely Fassnet lighthouse; the Ocean Queen is coming to the blue water, and the long solemn swell raises and sinks her with pendulum-like regularity.

'Ah, then, Masther Robert, an' we're done wid the poor ould counthry for good an' all!' Andy Callaghan's big bony hands are clasped in a tremor of emotion that would do honour to a picturesque Italian exile. 'The beautiful ould counthry, as has the greenest grass that ever grew, an' the clearest water that ever ran, an' the purtiest girls in the wide world! An' we're goin' among sthrangers, to pull an' dhrag for our bit to ate; but we'll never be happy till we see them blue hills and green fields once more!'

Mr. Wynn could almost have endorsed the sentiment just then. Perhaps Andy's low spirits were intensified by the uncomfortable motion of the ship, which was beginning to strike landsmen with that[26] rolling headache, the sure precursor of a worse visitation. Suffice it to say, that the mass of groaning misery in the steerage and cabins, on the subsequent night, would melt the heart of any but the most hardened 'old salt.' Did not Robert and Arthur regret their emigration bitterly, when shaken by the fangs of the fell demon, sea-sickness? Did not a chance of going to the bottom seem a trivial calamity? Answer, ye who have ever been in like pitiful case. We draw a curtain over the abject miseries of three days; over the Dutch-built captain's unseasonable joking and huge laughter—he, that could eat junk and biscuit if the ship was in Maelstrom! Robert could have thrown his boots at him with pleasure, while the short, broad figure stood in the doorway during his diurnal visit, chewing tobacco, and talking of all the times he had crossed 'the ferry,' as he familiarly designated the Atlantic Ocean. The sick passengers, to a man, bore him an animosity, owing to his ostentatiously rude health and iron nerves, which is, of all exhibitions, the most oppressive to a prostrate victim of the sea-fiend.

The third evening, an altercation became audible on the companion-ladder, as if some ship's officer were keeping back somebody else who was determined to come below.

'That's Andy Callaghan's voice,' said Arthur.

'Let me down, will ye, to see the young masthers?' came muffled through the doors and partition. 'Look here, now,'—in a coaxing tone,—'I don't like to be cross; but though I'm so bad afther the sickness, I'd set ye back in your little hole there at the fut of the stairs as aisy as I'd put a snail in its shell.'[27]

At this juncture Robert opened their state-room door, and prevented further collision. Andy's lean figure had become gaunter than ever.

'They thought to keep me from seeing ye, the villains! I'd knock every mother's son of 'em into the middle o' next week afore I'd be kep' away. Sure I was comin' often enough before, but the dinth of the sickness prevented me; an' other times I was chucked about like a child's marvel, pitched over an' hether by the big waves banging the side of the vessel. Masther Robert, asthore, it's I that's shaking in the middle of my iligant new frieze shute like a withered pea in a pod—I'm got so thin intirely.'

'We are not much better ourselves,' said Arthur, laughing; 'but I hope the worst of it is over.'

'I'd give the full of my pockets in goold, if I had it this minit,' said Andy, with great emphasis, 'to set me foot on the nakedest sod of bog that's in Ould Ireland this day! an' often I abused it; but throth, the purtiest sight in life to me would be a good pratiefield, an' meself walkin' among the ridges!'

'Well, Andy, we mustn't show the white-feather in that way; we could not expect to get to America without being sick, or suffering some disagreeables.'

'When yer honours are satisfied, 'tisn't for the likes of me to grumble,' Andy said resignedly. 'Only if everybody knew what was before them, they mightn't do many a thing, maybe!'

'Very true, Andy.'

'So we're all sayin' down in the steerage, sir. But oh, Masther Robert, I a'most forgot to tell ye, account of that spalpeen that thought to hindher yer own fosther-brother from comin' to see ye; but there's the[28] most wondherful baste out in the say this minit; an' it's spoutin' up water like the fountain that used to be at Dunore, only a power bigger; an' lyin' a-top of the waves like an island, for all the world! I'm thinkin' he wouldn't make much of cranching up the ship like a hazel nut.'

'A whale! I wonder will they get out the boats,' said Arthur, with sudden animation. 'I think I'm well enough to go on deck, Bob: I'd like to have a shot at the fellow.'

'A very useless expenditure of powder,' rejoined Robert. But Arthur, boy-like, sprang up-stairs with the rifle, which had often done execution among the wild-fowl of his native moorlands. Certainly it was a feat to hit such a prominent mark as that mountain of blubber; and Arthur felt justly ashamed of himself when the animal beat the water furiously and dived headlong in his pain.

Now the only other cabin passengers on board the brig were a retired military officer and his family, consisting of a son and two daughters. They had made acquaintance with the Wynns on the first day of the voyage, but since then there had been a necessary suspension of intercourse. And it was a certain mild but decided disapproval in Miss Armytage's grave glance, when Arthur turned round and saw her sitting on the poop with her father and little sister, which brought the colour to his cheek, for he felt he had been guilty of thoughtless and wanton cruelty. He bowed and moved farther away. But Robert joined them, and passed half an hour very contentedly in gazing at a grand sunset. The closing act of which was as follows: a dense black brow of cloud on the[29] margin of the sea; beneath it burst a flaming bolt of light from the sun's great eye, along the level waters. Far in the zenith were broad beams radiating across other clouds, like golden pathways. Slowly the dark curtain seemed to close down over the burning glory at the horizon. 'How very beautiful!' exclaimed Miss Armytage.

'Yes, my dear Edith, except as a weather barometer,' said her father. 'In that point of view it means—storm.'

'Oh, papa!' ejaculated the little girl, nestling close—not to him, but to her elder sister, whose hand instantly clasped hers with a reassuring pressure, while the quiet face looked down at the perturbed child, smiling sweetly. It was almost the first smile Robert had seen on her face; it made Miss Armytage quite handsome for the moment, he thought.

Miss Armytage, caring very little for his thought, was occupied an instant with saying something in a low tone to Jay, which gradually brightened the small countenance again. Robert caught the words, 'Our dear Saviour.' They reminded him of his mother.

Captain Armytage was correct in his prediction: before midnight a fierce north-easter was raging on the sea. The single beneficial result was, that it fairly cured all maladies but terror; for, after clinging to their berths during some hours with every muscle of their bodies, lest they should be swung off and smashed in the lurches of the vessel, the passengers arose next morning well and hungry.

'I spind the night on me head, mostly,' said Andy Callaghan. 'Troth, I never knew before how the flies[30] managed to walk on the ceilin' back downwards; but a thrifle more o' practice would tache it to meself, for half me time the floor was above at the rafters over me head. I donno rightly how to walk on my feet the day afther it.'

This was the only bad weather they experienced, as viewed nautically: even the captain allowed that it had been 'a stiffish gale;' but subsequent tumults of the winds and waves, which seemed tremendous to unsophisticated landsmen, were to him mere ocean frolics. And so, while each day the air grew colder, they neared the banks of Newfoundland, where everybody who could devise fishing-tackle tried to catch the famous cod of those waters. Arthur was one of the successful captors, having spent a laborious day in the main-chains for the purpose. At eventide he was found teaching little Jay how to hold a line, and how to manage when a bite came. Her mistakes and her delight amused him: both lasted till a small panting fish was pulled up.

'There's a whiting for you, now,' said he, 'all of your own catching.'

Jay looked at it regretfully, as the poor little gills opened and shut in vain efforts to breathe the smothering air, and the pretty silver colouring deadened as its life went. 'I am very sorry,' she said, folding her hands together; 'I think I ought not to have killed it only to amuse myself.' And she walked away to where her sister was sitting.

'What a strange child!' thought Arthur, as he watched the little figure crossing the deck. But he wound up the tackle, and angled no more for that evening.[31]

The calm was next day deepened by a fog; a dense haze settled on the sea, seeming by sheer weight to still its restless motion. Now was the skipper much more perturbed than during the rough weather: wrapt in a mighty pea-coat, he kept a perpetual look-out in person, chewing the tobacco meanwhile as if he bore it an animosity. Frequent gatherings of drift-ice passed, and at times ground together with a disagreeably strong sound. An intense chill pervaded the atmosphere,—a cold unlike what Robert or Arthur had ever felt in the frosts of Ireland, it was so much more keen and penetrating.

'The captain says it is from icebergs,' said the latter, drawing up the collar of his greatcoat about his ears, as they walked the deck. 'I wish we saw one—at a safe distance, of course. But this fog is so blinding'—

Even as he spoke, a vast whitish berg loomed abeam, immensely higher than the topmasts, in towers and spires snow-crested. What great precipices of grey glistening ice, as it passed by, a mighty half-distinguishable mass! what black rifts of destructive depth! The ship surged backward before the great refluent wave of its movement. A sensation of awe struck the bravest beholder, as slowly and majestically the huge berg glided astern, and its grim features were obliterated by the heavy haze.

Both drew a relieved breath when the grand apparition had passed. 'I wish Miss Armytage had seen it,' said Arthur.

'Why?' rejoined Robert, though the same thought was just in his own mind.

'Oh, because it was so magnificent, and I am sure[32] she would admire it. I could almost make a poem about it myself. Don't you know the feeling, as if the sight were too large, too imposing for your mind somehow? And the danger only intensifies that.'

'Still, I wish we were out of their reach. The skipper's temper will be unbearable till then.'

It improved considerably when the fog rose off the sea, a day or two subsequently, and a head-wind sprang up, carrying them towards the Gulf. One morning, a low grey stripe of cloud on the horizon was shown to the passengers as part of Newfoundland. Long did Robert Wynn gaze at that dim outline, possessed by all the strange feelings which belong to the first sight of the new world, especially when it is to be a future home. No shame to his manhood if some few tears for the dear old home dimmed his eyes as he looked. But soon that shadow of land disappeared, and, passing Cape Race at a long distance, they entered the great estuary of the St. Lawrence, which mighty inlet, if it had place in our little Europe, would be fitly termed the Sea of Labrador; but where all the features of nature are colossal, it ranks only as a gulf.

One morning, when little Jay had gone on deck for an ante-breakfast run, she came back in a state of high delight to the cabin. 'Oh, Edith, such beautiful birds! such lovely little birds! and the sailors say they're from the land, though we cannot see it anywhere. How tired they must be after such a long fly, all the way from beyond the edge of the sea! Do come and look at them, dear Edith—do come!'

Sitting on the shrouds were a pair of tiny land birds, no bigger than tomtits, and wearing red top-knots on their heads. How welcome were the confiding[33] little creatures to the passengers, who had been rocked at sea for nearly five weeks, and hailed these as sure harbingers of solid ground! They came down to pick up Jay's crumbs of biscuit, and twittered familiarly. The captain offered to have one caught for her, but, after a minute's eager acquiescence, she declined. 'I would like to feel it in my hand,' said she, 'but it is kinder to let it fly about wherever it pleases.'

'Why, you little Miss Considerate, is that your principle always?' asked Arthur, who had made a great playmate of her. She did not understand his question; and on his explaining in simpler words, 'Oh, you know I always try to think what God would like. That is sure to be right, isn't it?'

'I suppose so,' said Arthur, with sudden gravity.

'Edith taught me—she does just that,' continued the child. 'I don't think she ever does anything that is wrong at all. But oh, Mr. Wynn,' and he felt a sudden tightening of her grasp on his hand, 'what big bird is that? look how frightened the little ones are!'

A hawk, which had been circling in the air, now made a swoop on the rigging, but was anticipated by his quarry: one of the birds flew actually into Arthur's hands, and the other got in among some barrels which stood amidships.

'Ah,' said Arthur, 'they were driven out here by that chap, I suppose. Now I'll give you the pleasure of feeling one of them in your hands.'

'But that wicked hawk!'

'And that wicked Jay, ever to eat chickens or mutton.'

'Ah! but that is different. How his little heart[34] beats and flutters! I wish I had him for a pet. I would love you, little birdie, indeed I would.'

For some days they stayed by the ship, descending on deck for crumbs regularly furnished them by Jay, to whom the office of feeding them was deputed by common consent. But nearing the island of Anticosti, they took wing for shore with a parting twitter, and, like Noah's dove, did not return. Jay would not allow that they were ungrateful.

[35]

In the evening he was able to show her the wide pitiless snow ranges of Labrador, whence blew a keen desert air. Perpetual pine-woods—looking like a black band set against the encroaching snow—edged the land, whence the brig was some miles distant, tacking to gain the benefit of the breeze off shore.

Presently came a strange and dismal sound wafted over the waters from the far pine forests—a high prolonged howl, taken up and echoed by scores of ravenous throats, repeated again and again, augmenting[36] in fierce cadences. Jay caught Mr. Wynn's arm closer. 'Like wolves,' said Arthur; 'but we are a long way off.'

'I must go and tell Edith,' said the child, evidently feeling safer with that sister than in any other earthly care. After he had brought her to the cabin, he returned on deck, listening with a curious sort of pleasure to the wild sounds, and looking at the dim outlines of the shore.

As darkness dropped over the circle of land and water, a light seemed to rise behind those hills, revealing their solid shapes anew, stealing silently aloft into the air, like a pale and pure northern dawn. At first he thought it must be the rising moon, but no orb appeared; and as the brilliance deepened, intensified into colour, and shot towards the zenith, he knew it for the aurora borealis. Soon the stars were blinded out by the vivid sweeping flicker of its rays; hues bright and varied as the rainbow thrilled along the iridescent roadways to the central point above, and tongues of flame leaped from arches in the north-west. Burning scarlet and amber, purple, green, trembled in pulsations across the ebony surface of the heavens, as if some vast fire beneath the horizon was flashing forth coruscations of its splendour to the dark hemisphere beyond. The floating banners of angels is a hackneyed symbol to express the oppressive magnificence of a Canadian aurora.

The brothers were fascinated: their admiration had no words.

'This is as bad as the iceberg for making a fellow's brain feel too big for his head,' said Arthur at last. 'We've seen two sublime things, at all events, Bob.'[37]

Clear frosty weather succeeded—weather without the sharp sting of cold, but elastic and pure as on a mountain peak. Being becalmed for a day or two off a wooded point, the skipper sent a boat ashore for fuel and water. Arthur eagerly volunteered to help; and after half an hour's rowing through the calm blue bay, he had the satisfaction to press his foot on the soil of Lower Canada.

There was a small clearing beside a brook which formed a narrow deep cove, a sort of natural miniature dock where their boat floated. A log hut, mossed with years, was set back some fifty yards towards the forest. What pines were those! what giants of arborescence! Seventy feet of massive shaft without a bough; and then a dense thicket of black inwoven branches, making a dusk beneath the fullest sunshine.

'I tell you we haven't trees in the old country; our oaks and larches are only shrubs,' he said to Robert, when narrating his expedition. 'Wait till you see pines such as I saw to-day. Looking along the forest glades, those great pillars upheld the roof everywhere in endless succession. And the silence! as if a human creature never breathed among them, though the log hut was close by. When I went in, I saw a French habitan, as they call him, who minds the lighthouse on the point, with his Indian wife, and her squaw mother dressed in a blanket, and of course babies—the queerest little brown things you ever saw. One of them was tied into a hollow board, and buried to the chin in "punk," by way of bed-clothes.'

'And what is punk?' asked Robert.

'Rotten wood powdered to dust,' answered Arthur, with an air of superior information. 'It's soft enough;[38] and the poor little animal's head was just visible, so that it looked like a young live mummy. But the grandmother squaw was even uglier than the grandchildren; a thousand and one lines seamed her coppery face, which was the colour of an old penny piece rather burnished from use. And she had eyes, Bob, little and wide apart, and black as sloes, with a snaky look. I don't think she ever took them off me, and 'twas no manner of use to stare at her in return. So, as I could not understand what they were saying,—gabbling a sort of patois of bad French and worse English, with a sprinkling of Indian,—and as the old lady's gaze was getting uncomfortable, I went out again among my friends, the mighty pines. I hope we shall have some about our location, wherever we settle.'

'And I trust more intimate acquaintance won't make us wish them a trifle fewer and slighter,' remarked Robert.

'Well, I am afraid my enthusiasm would fade before an acre of such clearing,' rejoined Arthur. 'But, Bob, the colours of the foliage are lovelier than I can tell. You see a little of the tinting even from this distance. The woods have taken pattern by the aurora: it seems we are now in the Indian summer, and the maple trees are just burning with scarlet and gold leaves.'

'I suppose you did not see many of our old country trees?'

'Hardly any. Pine is the most plentiful of all: how I like its sturdy independent look! as if it were used to battling with snowstorms, and got strong by the exercise. The mate showed me hickory and hemlock, and a lot of other foreigners, while the men were cutting logs in the bush.'[39]

'You have picked up the Canadian phraseology already,' observed Robert.

'Yes;' and Arthur reddened slightly. 'Impossible to avoid that, when you're thrown among fellows that speak nothing else. But I wanted to tell you, that coming back we hailed a boat from one of those outward-bound ships lying yonder at anchor: the mate says their wood and water is half a pretence. They are smuggling skins, in addition to their regular freight of lumber.'

'Smuggling skins!'

'For the skippers' private benefit, you understand: furs, such as sable, marten, and squirrel; they send old ship's stores ashore to trade with vagrant Indians, and then sew up the skins in their clothes, between the lining and the stuff, so as to pass the Custom-house officers at home. Bob! I'm longing to be ashore for good. You don't know what it is to feel firm ground under one's feet after six weeks' unsteady footing. I'm longing to get out of this floating prison, and begin our life among the pines.'

Robert shook his head a little sorrowfully. Now that they were nearing the end of the voyage, many cares pressed upon him, which to the volatile nature of Arthur seemed only theme for adventure. Whither to bend their steps in the first instance, was a matter for grave deliberation. They had letters of introduction to a gentleman near Carillon on the Ottawa, and others to a family at Toronto. Former friends had settled beside the lonely Lake Simcoe, midway between Huron and Ontario. Many an hour of the becalmed days he spent over the maps and guide-books they had brought, trying to study out a result. Jay came[40] up to him one afternoon, as he leaned his head on his hand perplexedly.

'What ails you? have you a headache?'

'No, I am only puzzled.'

Her own small elbow rested on the taffrail, and her little fingers dented the fair round cheek, in unwitting imitation of his posture.

'Is it about a lesson? But you don't have to get lessons.'

'No; it is about what is best for me to do when I land.'

'Edith asks God always; and He shows her what is best,' said the child, looking at him wistfully. Again he thought of his pious prayerful mother. She might have spoken through the childish lips. He closed his books, remarking that they were stupid. Jay gave him her hand to walk up and down the deck. He had never made it a custom to consult God, or refer to Him in matters of daily life, though theoretically he acknowledged His pervading sovereignty. To procure the guidance of Infinite Wisdom would be well worth a prayer. Something strong as a chain held him back—the pride of his consciously unrenewed heart.

When the weather became favourable, they passed up the river rapidly; and a succession of the noblest views opened around them. No panorama of the choice spots of earth could be lovelier. Lofty granite islets, such as Kamouraska, which attains an altitude of five hundred feet; bold promontories and deep basin bays; magnificent ranges of bald blue mountains inland; and, as they neared Grosse Isle and the quarantine ground, the soft beauties of civilisation were superadded. Many ships of all nations lay at anchor;[41] the shore was dotted with white farmhouses, and neat villages clustered each round the glittering spire of a church.

'How very French that is, eh?' said Captain Armytage, referring to those shining metal roofs. 'Tinsel is charming to the eyes of a habitan. You know, I've been in these parts before with my regiment: so I am well acquainted with the ground. We have the parish of St. Thomas to our left now, thickly spotted with white cottages: St. Joachim is on the opposite bank. The nomenclature all about here smacks of the prevailing faith and of the old masters.'

''Tis a pity they didn't hold by the musical Indian names,' said Robert Wynn.

'Well, yes, when the music don't amount to seventeen syllables a-piece, eh?' Captain Armytage had a habit of saying 'eh' at every available point in his sentences. Likewise had he the most gentleman-like manners that could be, set off by the most gentleman-like personal appearance; yet, an inexplicable something about him prevented a thorough liking. Perhaps it was the intrinsic selfishness, and want of sincerity of nature, which one instinctively felt after a little intercourse had worn off the dazzle of his engaging demeanour. Perhaps Robert had detected the odour of rum, ineffectually concealed by the fragrance of a smoking pill, more frequently than merely after dinner, and seen the sad shadow on his daughter's face, following. But that did not prevent Captain Armytage's being a very agreeable and well-informed companion nevertheless.

'Granted that "Canada" is a pretty name,' said he; 'but it's Spanish more than native. "Aca nada,"[42] nothing here,—said the old Castilian voyagers, when they saw no trace of gold mines or other wealth along the coast. That's the story, at all events. But I hold to it that our British John Cabot was the first who ever visited this continent, unless there's truth in the old Scandinavian tales, which I don't believe.'

But the gallant officer's want of credence does not render it the less a fact, that, about the year 1001, Biorn Heriolson, an Icelander, was driven south from Greenland by tempestuous weather, and discovered Labrador. Subsequently, a colony was established for trading purposes on some part of the coast named Vinland; but after a few Icelanders had made fortunes of the peltries, and many had perished among the Esquimaux, all record of the settlement is blotted out, and Canada fades from the world's map till restored by the exploration of the Cabots and Jacques Cartier. The two former examined the seaboard, and the latter first entered the grand estuary of the St. Lawrence, which he named from the saint's day of its discovery; and he also was the earliest white man to gaze down from the mighty precipice of Quebec, and pronounce the obscure Indian name which was hereafter to suggest a world-famed capital. Then, the dwellings and navies of nations and generations yet unborn were growing all around in hundreds of leagues of forest; a dread magnificence of shade darkened the face of the earth, amid which the red man reigned supreme. Now, as the passengers of the good brig Ocean Queen gazed upon it three centuries subsequently, the slow axe had chopped away those forests of pine, and the land was smiling with homesteads, and mapped out in fields of rich farm produce: the encroachments[43] of the irresistible white man had metamorphosed the country, and almost blotted out its olden masters. Robert Wynn began to realize the force of Hiram Holt's patriotic declaration, 'It's the finest country in the world!'

'And the loveliest!' he could have added, without even a saving clause for his own old Emerald Isle, when they passed the western point of the high wooded island of Orleans, and came in view of the superb Falls of Montmorenci; two hundred and fifty feet of sheer precipice, leaped by a broad full torrent, eager to reach the great river flowing beyond, and which seemed placidly to await the turbulent onset. As Robert gazed, the fascination of a great waterfall came over him like a spell. Who has not felt this beside Lodore, or Foyers, or Torc? Who has not found his eye mesmerized by the falling sheet of dark polished waters, merging into snowy spray and crowned with rainbow crest, most changeable, yet most unchanged?

Thousands of years has this been going on; you may read it in the worn limestone layers that have been eaten through, inches in centuries, by the impetuous stream. Thus, also, has the St. Lawrence carved out its mile-wide bed beneath the Heights of Abraham—the stepping-stone to Wolfe's fame and Canadian freedom

[44]

'There's Point Levi to the south, a mile away, in front of the mountains. Something unpleasant once befell me in crossing there. I and another sub. hired a boat for a spree, just because the hummocks of ice were knocking about on the tide, and all prudent people stayed ashore; but we went out in great dreadnought boots, and bearskin caps over our ears, and[45] amused ourselves with pulling about for a while among the floes. I suppose the grinding of the ice deafened us, and the hummocks hid us from view of the people on board; at all events, down came one of the river steamers slap on us. I saw the red paddles laden with ice at every revolution, and the next instant was sinking, with my boots dragging me down like a cannon-ball at my feet. I don't know how I kicked them off, and rose: Gilpin, the other sub., had got astride on the capsized boat; a rope flung from the steamer struck me, and you may believe I grasped it pretty tightly. D'ye see here?' and he showed Robert a front tooth broken short: 'I caught with my hands first, and they were so numb, and the ice forming so fast on the dripping rope, that it slipped till I held by my teeth; and another noose being thrown around me lasso-wise, I was dragged in. A narrow escape, eh?'

'Very narrow,' echoed Robert. He noticed the slight shiver that ran through the daughter's figure, as she leaned on her father's arm. His handsome face looked down at her carelessly.

'Edith shudders,' said he; 'I suppose thinking that so wonderful an escape ought to be remembered as more than a mere adventure.' To which he received no answer, save an appealing look from her soft eyes. He turned away with a short laugh.

'Well, at all events, it cured me of boating among the ice. Ugh! to be sucked in and smothered under a floe would be frightful.'

Mr. Wynn wishing to say something that would prove he was not thinking of the little aside-scene[46] between father and daughter, asked if the St. Lawrence was generally so full of ice in winter.

It was difficult to believe now in the balmy atmosphere of the Indian summer, with a dreamy sunshine warming and gladdening all things,—the very apotheosis of autumn,—that wintry blasts would howl along this placid river, surging fierce ice-waves together, before two months should pass.

'There's rarely a bridge quite across,' replied Captain Armytage; 'except in the north channel, above the isle of Orleans, where the tide has less force than in the southern, because it is narrower; but in the widest place the hummocks of ice are frequently crushed into heaps fifteen or twenty feet high, which makes navigation uncomfortably exciting.'

'I should think so,' rejoined Robert drily.

'Ah, you have yet to feel what a Canadian winter is like, my young friend;' and Captain Armytage nodded in that mysterious manner which is intended to impress a 'griffin' with the cheering conviction that unknown horrors are before him.

'I wonder what is that tall church, whose roof glitters so intensely?'

'The cathedral, under its tin dome and spires. The metal is said to hinder the lodging and help the thawing of the snow, which might otherwise lie so heavy as to endanger the roof.'

'Oh, that is the reason!' ejaculated Robert, suddenly enlightened as to the needs-be of all the surface glitter.

'Rather a pretty effect, eh? and absolutely unique, except in Canadian cities. It suggests an infinitude[47] of greenhouses reflecting sunbeams at a variety of angles of incidence.'

'I presume this is the lower town, lying along the quays?' said Robert.

'Yes, like our Scottish Edinburgh, the old city, being built in dangerous times, lies huddled close together under protection of its guardian rock,' said the Captain. 'But within, you could fancy yourself suddenly transported into an old Normandy town, among narrow crooked streets and high-gabled houses: nor will the degree of cleanliness undeceive you. For, unlike most other American cities, Quebec has a Past as well as a Present: there is the French Past, narrow, dark, crowded, hiding under a fortification; and there is the English Present, embodied in the handsome upper town, and the suburb of St. John's, broad, well-built, airy. The line of distinction is very marked between the pushing Anglo-Saxon's premises and the tumble-down concerns of the stand-still habitan.'

Perhaps, also, something is due to the difference between Protestant enterprise and Roman Catholic supineness.

'There's a boat boarding us already,' said Robert.

It proved to be the Custom-house officers; and when their domiciliary visit was over, Robert and Arthur went ashore. Navigating through a desert expanse of lumber rafts and a labyrinth of hundreds of hulls, they stepped at last on the ugly wooden wharves which line the water's edge, and were crowded with the usual traffic of a port; yet singularly noiseless, from the boarded pavement beneath the wheels.[48]

Though the brothers had never been in any part of France, the peculiarly French aspect of the lower town struck them immediately. The old-fashioned dwellings, with steep lofty roofs, accumulated in narrow alleys, seemed to date back to an age long anterior to Montcalm's final struggle with Wolfe on the heights; even back, perchance, to the brave enthusiast Champlain's first settlement under the superb headland, replacing the Indian village of Stadacona. To perpetuate his fame, a street alongside the river is called after him; and though his 'New France' has long since joined the dead names of extinct colonies, the practical effects of his early toil and struggle remain in this American Gibraltar which he originated.

Andy Callaghan had begged leave to accompany his young masters ashore, and marched at a respectful distance behind them, along that very Champlain Street, looking about him with unfeigned astonishment. 'I suppose the quarries is all used up in these parts, for the houses is wood, an' the churches is wood, and the sthreets has wooden stones ondher our feet,' he soliloquized, half audibly. 'It's a mighty quare counthry intirely: between the people making a land on top of the wather for 'emselves by thim big rafts, an' buildin' houses on 'em, and kindlin' fires'——

Here his meditation was rudely broken into by the sudden somerset of a child from a doorstep he was passing; but it had scarcely touched the ground when Andy, with an exclamation in Irish, swung it aloft in his arms.

'Mono mush thig thu! you crathur, is it trying which yer head or the road is the hardest, ye are?[49] Whisht now, don't cry, me fine boy, and maybe I'd sing a song for ye.'

'Wisha then, cead mille failthe a thousand times, Irishman, whoever ye are!' said the mother, seizing Andy's hand. 'And my heart warms to the tongue of the old counthry! Won't you come in, honest man, an' rest awhile, an' it's himself will be glad to see ye?'

'And who's himself?' inquired Andy, dandling the child.

'The carpenter, Pat M'Donagh of Ballinoge'—

'Hurroo!' shouted Andy, as he executed a whirligig on one leg, and then embraced the amazed Mrs. M'Donagh fraternally. 'My uncle's son's wife! an' a darling purty face you have of yer own too.'

'Don't be funnin', now,' said the lady, bridling; 'an' you might have axed a person's lave before ye tossed me cap that way. Here, Pat, come down an' see yer cousin just arrived from the ould counthry!'

Robert and Arthur Wynn, missing their servitor at the next turn, and looking back, beheld something like a popular émeute in the narrow street, which was solely Andy fraternizing with his countrymen and recovered relations.

'Wait a minit,' said Andy, returning to his allegiance, as he saw them looking back; 'let me run afther the gentlemen and get lave to stay.'

'Lave, indeed!' exclaimed the republican-minded Mrs. M'Donagh; 'it's I that wud be afther askin lave in a free counthry! Why, we've no masthers nor missusses here at all.'

'Hut, woman, but they're my fostherers—the young Mr. Wynns of Dunore.'[50]

Great had been that name among the peasantry once; and even yet it had not lost its prestige with the transplanted Pat M'Donagh. He had left Ireland a ragged pauper in the famine year, and was now a thriving artisan, with average wages of seven shillings a day; an independence with which Robert Wynn would have considered himself truly fortunate, and upon less than which many a lieutenant in Her Majesty's infantry has to keep up a gentlemanly appearance. Pat's strength had been a drug in his own country; here it readily worked an opening to prosperity.

And presently forgetting his sturdy Canadian notions of independence, the carpenter was bowing cap in hand before the gentlemen, begging them to accept the hospitality of his house while they stayed in Quebec. 'The M'Donaghs is ould tenants of yer honours' father, an' many a kindness they resaved from the family, and 'twould be the joy of me heart to see one of the ancient stock at me table,' he said; 'an' sure me father's brother's son is along wid ye.'

'The ancient stock' declined, with many thanks, as they wanted to see the city; but Andy, not having the same zeal for exploring, remained in the discovered nest of his kinsfolk, and made himself so acceptable, that they parted subsequently with tears.

Meanwhile the brothers walked from the Lower to the Upper Town, through the quaint steep streets of stone houses—relics of the old French occupation. The language was in keeping with this foreign aspect, and the vivacious gestures of the inhabitants told their pedigree. Robert and Arthur were standing[51] near a group of them in the market-square, assembled round a young bear brought in by an Indian, when the former felt a heavy hand on his shoulder, and the next instant the tenacity of his wrist was pretty well tested in the friendly grasp of Hiram Holt.

[52]

'And so you've followed my advice! Bravo, young blood! You'll never be sorry for adopting Canada as your country. Now, what are your plans?' bestowing an aside left-hand grasp upon Arthur. 'Can Hiram Holt help you? Have the old people come out? So much the better; they would only cripple you in the beginning. Wait till your axe has cut the niche big enough. You rush on for the West, I suppose?'

All these inquiries in little longer than a breath; while he wrung Robert's hand at intervals with a[53] heartiness and power of muscle which almost benumbed the member.

'We have letters to friends on Lake Erie, and to others on Lake Simcoe,' said Robert, rescuing his hand, which tingled, and yet communicated a very pleasurable sensation to his heart. 'We are not quite decided on our line of march.'

'Well, how did you come? Emigrant vessel?'

Adopting the laconic also, Robert nodded, and said it was their first day in Quebec.

'Get quit of her as soon as you can; haul your traps ashore, and come along with me. I'll be going up the Ottawa in a day or two, home; and 'twill be only a step out of your way westward. You can look about you, and see what Canadian life is like for a few weeks; the longer, the more welcome to Hiram Holt's house. Is that fixed?'

Robert was beginning to thank him warmly—

'Now, shut up, young man; I distrust a fellow that has much palaver. You look too manly for it. I calculate your capital ain't much above your four hands between you?'

Arthur was rather discomfited at a query so pointed, and so directly penetrating the proud British reserve about monetary circumstances; but Robert, knowing that the motive was kind-hearted, and the manner just that of a straightforward unconventional settler, replied, 'You are nearly right, Mr. Holt; our capital in cash is very small; but I hope stout bodies and stout hearts are worth something.'

'What would you think of a bush farm? I think I heard you say you had some experience on your father's farm in Ireland?'[54]

'My father's estate, sir,' began Arthur, reddening a little.

Holt measured him by a look, but not one of displeasure. 'Farms in Canada grow into estates,' said he; 'by industry and push, I shouldn't be surprised if you became a landed proprietor yourself before your beard is stiff.' Arthur had as yet no symptom of that manly adornment, though anxiously watching for the down. The backwoodsman turned to Robert.

'Government lands are cheap enough, no doubt; four shillings an acre, and plenty of them. If you're able, I'd have you venture on that speculation. Purchase-money is payable in ten years; that's a good breathing time for a beginner. But can you give up all luxuries for a while, and eat bread baked by your own hands, and sleep in a log hut on a mess of juniper boughs, and work hard all day at clearing the eternal forests, foot by foot?'

'We can,' answered Arthur eagerly. His brother's assent was not quite so vivacious.

Hiram Holt thought within himself how soon the ardent young spirit might tire of that monotony of labour; how distasteful the utter loneliness and uneventfulness of forest life might become to the undisciplined lad, accustomed, as he shrewdly guessed, to a petted and idling boyhood.

'Well said, young fellow. For three years I can't say well done; though I hope I may have that to add also.'

By this time they had passed from the Market Square to the Esplanade, overhanging the Lower Town, and which commands a view almost matchless[55] for extent and varied beauty. At this hour the shades of evening were settling down, and tinging with sombre hues the colouring of the landscape: over the western edge the sun had sunk; far below, the noble river lay in black shadow and a single gleaming band of dying daylight, as it crept along under the fleets of ships.

Indistinct as the details were becoming, the outlined masses were grander for the growing obscurity, and Robert could not restrain an exclamation of 'Magnificent!'

'Well, I won't deny but it is handsome,' said Mr. Holt, secretly gratified; 'I never expect to see anything like it for situation, whatever other way it's deficient. Now I'm free to confess it's only a village to your London, for forty thousand wouldn't be missed out of two or three millions; but bigness ain't the only beauty in the world, else I'd be a deal prettier than my girl Bell, who's not much taller than my walking-stick, and the fairest lass in our township.'

The adjective 'pretty' seemed so ridiculously inappropriate to one of Mr. Holt's dimensions and hairy development of face, that Robert could not forbear a smile. But the Canadian had returned to the landscape.

'Quebec is the key of Canada, that's certain; and so Wolfe and Montcalm knew, when they fought their duel here for the prize.'

Arthur pricked up his ears at the celebrated names. 'Oh, Bob, we must try and see the battlefield,' he exclaimed, being fresh from Goldsmith's celebrated manual of English history.

'To-morrow,' said Mr. Holt. 'It lies west on top[56] of the chain of heights flanking the river. A monument to the generals stands near here, in the Castle gardens, with the names on opposite sides of the square block. To be sure, how death levels us all! Lord Dalhousie built that obelisk when he was Governor in 1827. You see, as it is the only bit of history we possess, we never can commemorate it enough; so there's another pillar on the plains.'

Lights began to appear in the vessels below, reflected as long brilliant lines in the glassy deeps. 'Perhaps we ought to be getting back to the ship,' suggested Robert, 'before it is quite dark.'

'Of course you are aware that this is the aristocratic section of the town,' said Mr. Holt, as they turned to retrace their steps. 'Here the citizens give themselves up to pleasure and politics, while the Lower Town is the business place. The money is made there which is spent here; and when our itinerating Legislature comes round, Quebec is very gay, and considerably excited.'

'Itinerating Legislature! what's that?' asked Arthur.

'Why, you see, in 1840 the provinces of Upper and Lower Canada were legally united; their representatives met in the same House of Assembly, and so forth. Kingston was made the capital, as a central point; however, last year ('49) the famous device of itineration was introduced, by which, every four years, his Excellency the Governor and the Right Honourable Parliament move about from place to place, like a set of travelling showmen.'

'And when will Quebec's turn come?'

'In '51, next year. The removal of court patronage is said to have injured the city greatly: like all[57] half-and-half measures, it pleases nobody. Toronto growls, and Kingston growls, and Quebec growls, and Montreal growls; Canada is in a state of chronic dissatisfaction, so far as the towns go. For myself, I never feel at home in Quebec; the lingo of the habitans puzzles me, and I'm not used to the dark narrow streets.'

'Are you a member of the Parliament, Mr. Holt?' asked Arthur.

'No, though I might be,' replied Hiram, raising his hat for a moment from his masses of grizzled hair. 'I've been town reeve many times, and county warden once. The neighbours wanted to nominate me for the House of Assembly, and son Sam would have attended to the farms and mills; but I had that European trip in my eye, and didn't care. Ah, I see you look at the post-office, young fellow,' as they passed that building just outside the gate of the Upper Town wall; 'don't get homesick already on our hands; there are no post-offices in the bush.'

Arthur looked slightly affronted at this speech, and, to assert his manliness, could have resigned all letters for a twelvemonth. Mr. Holt walked on with a preoccupied air until he said,—

'I must go now, I have an appointment; but I'll be on board to-morrow at noon. The brig Ocean Queen, of Cork, you say? Now your path is right down to Champlain Street; you can't lose your way. Good-bye;' and his receding figure was lost in the dusk, with mighty strides.

'He's too bluff,' said Arthur, resenting thus the one or two plain-spoken sentences that had touched himself.[58]

'But sound and steady, like one of his own forest pines,' said Robert.

'We have yet to test that,' rejoined Arthur, with some truth. 'I wonder shall we ever find the house into which Andy was decoyed; those wooden ranges are all the image of one another. I am just as well pleased he wasn't mooning after us through the Upper Town during the daylight; for, though he's such a worthy fellow, he hasn't exactly the cut of a gentleman's servant. We must deprive him of that iligant new frieze topcoat, with its three capes, till it is fashioned into a civilised garment.'

Mr. Pat M'Donagh's mansion was wooden—one of a row of such, situated near the dockyard in which he wrought. Andy was already on the look-out from the doorstep; and, conscious that he had been guilty of some approach to excess, behaved with such meek silence and constrained decorum, that his master guessed the cause, and graciously connived at his slinking to his berth as soon as he was up the ship's side.

But when Mr. Wynn walked forward next morning to summon Andy's assistance for his luggage, he found that gentleman the focus of a knot of passengers, to whom he was imparting information in his own peculiar way. 'Throth an' he talks like a book itself,' was the admiring comment of a woman with a child on one arm, while she crammed her tins into her red box with the other.

'Every single ha'porth is wood, I tell ye, barrin' the grates, an' 'tisn't grates they are at all, but shtoves. Sure I saw 'em at Pat M'Donagh's as black as twelve o'clock at night, an' no more a sign of a blaze out of[59] 'em than there's light from a blind man's eye; an' 'tisn't turf nor coal they burns, but only wood agin. It's I that wud sooner see the plentiful hearths of ould Ireland, where the turf fire cooks the vittles dacently! Oh wirra! why did we ever lave it?'

But Mr. Wynn intercepted the rising chorus by the simple dissyllable, 'Andy!'

'Sir, yer honour!' wheeling round, and suddenly resuming a jocose demeanour; 'I was only jokin' about bein' back. I must be kapin' up their sperits, the crathurs, that dunno what's before them at all at all; only thinks they're to be all gintlemin an' ladies.' This, as he followed his master towards the cabins: 'Whisht here, Misther Robert,' lowering his tone confidentially.' You'd laugh if you heard what they think they're goin' to get. Coinin' would be nothin' to it. That red-headed Biddy Flannigan' (Andy's own chevelure was of carrot tinge, yet he never lost an opportunity of girding at those like-haired), 'who couldn't wash a pair of stockings if you gev her a goold guinea, expects twenty pund a year an' her keep, at the very laste; and Murty Keefe the labourin' boy, that could just trench a ridge of praties, thinks nothing of tin shillins a day. They have it all laid out among them iligant. Mrs. Mulrooney is lookin' out for her carriage by'ne-by; and they were abusin' me for not sayin' I'd cut an' run from yer honours, now that I'm across.'

'Well, Andy, I'd be sorry to stand in the way of your advancement—'

'Me lave ye, Misther Robert!' in accents of unfeigned surprise; 'not unless ye drove me with a whip an' kicked me—is it your poor fostherer Andy[60] Callaghan? Masther Bob, asthore, ye're all the counthry I have now, an' all the frinds; an' I'll hold by ye, if it be plasing, as long as I've strength to strike a spade.'

Tears actually stood in the faithful fellow's eyes. 'I believe you, Andy,' said his master, giving his hand to the servant for a grasp of friendship, which, if it oftener took place between the horny palm of labour and the whiter fingers of the higher born, would be for the cementing of society by such recognition of human brotherhood.

When Andy had all their luggage on deck in order for the boats, he came up mysteriously to Mr. Wynn, where he stood by the taffrail.

'There's that poor young lady strivin' and strugglin' to regulate them big boxes, an' her good-for-nothin' father an' brother smokin' in the steerage, an' lavin' everything on her. Fine gintlemin, indeed! More like the Injins, that I'm tould lies in bed while their wives digs the praties!'