O'er the land of the free and the home of the brave!"

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Hero Stories from American History, by

Albert F. Blaisdell and Francis K. Ball

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net

Title: Hero Stories from American History

For Elementary Schools

Author: Albert F. Blaisdell

Francis K. Ball

Release Date: January 26, 2010 [EBook #31092]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK HERO STORIES FROM AMERICAN HISTORY ***

Produced by Ron Swanson

|

|

"'Tis the star-spangled banner: O, long may it wave O'er the land of the free and the home of the brave!" |

This book is intended to be used as a supplementary historical reader for the sixth and seventh grades of our public schools, or for any other pupils from twelve to fifteen years of age. It is also designed for collateral reading in connection with the study of a formal text-book on American history.

The period here included is the first fifty years of our national life. No attempt has been made, however, to present a connected account, or to furnish a bird's-eye view, of this half century.

It is the universal testimony of experienced teachers that such materials as are pervaded with reality serve a useful purpose with young pupils. The reason is plain. Historical matter that is instinct with human life attracts and holds the attention of boys and girls, and whets their desire to know more of the real meaning of their country's history. For this reason the authors have selected rapid historical narratives, treating of notable and dramatic events, and have embellished them with more details than is feasible within the limits of most school-books. Free use has been made of personal incidents and anecdotes, which thrill us because of their human element, and smack of the picturesque life of our forefathers.

It has seemed advisable to arrange the subjects in chronological order. As the various chapters have appeared in proof, they have been put to a practical test in the sixth grade in several grammar schools. In a number of instances the pupils learned that, in the first reading, some of the stories were less difficult than others. From the nature of the subject-matter this is inevitable. For instance, it was found easier, and doubtless more interesting, to read "The Patriot Spy" and "A Daring Exploit" before beginning "The Hero of Vincennes" and "The Crisis." "Old Ironsides" will at first probably appeal to more young people than "The Final Victory."

An historical reader would truly be of little value if it could be read at a glance, like so many insipid storybooks, and then thrown aside.

Hence, it is suggested that teachers, after becoming familiar with the general scope of this book and gauging with some care the capabilities of their pupils, should, if they find it for the best interests of their classes, change the order of the chapters for the first reading. But in the second, or review reading, they should follow the chronological order.

The attention of teachers is called to the questions for review, the pronunciation of proper names, and the reference books and supplementary reading in American history mentioned after the chapters below. The index is made full for purposes of reference and review.

In the preparation of this book, old journals, original records and documents, and sundry other trustworthy sources have been diligently consulted and freely utilized.

We would acknowledge our indebtedness to Mrs. Janet Nettleton Ball, who has aided us materially at several stages of our work; and to Mr. Ralph Hartt Bowles, Instructor in English in The Phillips Exeter Academy, for valuable assistance in reading the manuscript and the proofs.

BOSTON, March, 1903.

CHAPTER I

THE HERO OF VINCENNES

CHAPTER II

A MIDWINTER CAMPAIGN

CHAPTER III

HOW PALMETTO LOGS MAY BE USED

CHAPTER IV

THE PATRIOT SPY

CHAPTER V

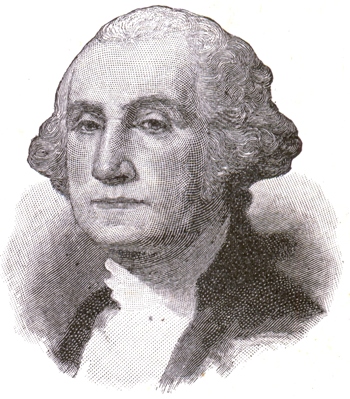

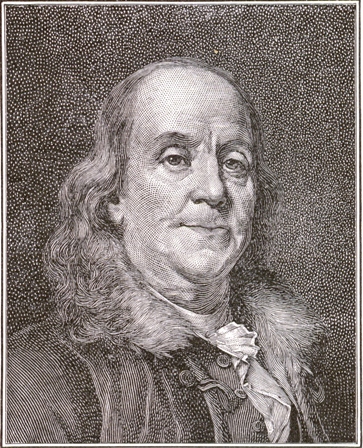

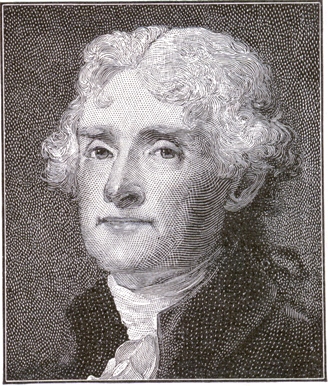

OUR GREATEST PATRIOT

CHAPTER VI

A MIDNIGHT SURPRISE

CHAPTER VII

THE DEFEAT OF THE RED DRAGOONS

CHAPTER VIII

FROM TEAMSTER TO MAJOR GENERAL

CHAPTER IX

THE FINAL VICTORY

CHAPTER X

THE CRISIS

CHAPTER XI

A DARING EXPLOIT

CHAPTER XII

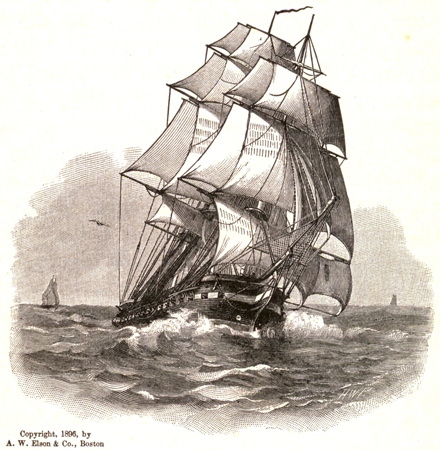

"OLD IRONSIDES"

CHAPTER XIII

"OLD HICKORY'S" CHRISTMAS

CHAPTER XIV

A HERO'S WELCOME

BOOKS FOR REFERENCE AND READING IN THE STUDY OF AMERICAN HISTORY

Early in 1775 Daniel Boone, the famous hunter and Indian fighter, with thirty other backwoodsmen, set out from the Holston settlements to clear the first trail, or bridle path, to what is now Kentucky. In the spring of the same year, George Rogers Clark, although a young fellow of only twenty-three years, tramped through the wilderness alone. When he reached the frontier settlements, he at once became the leader of the little band of pioneers.

|

| A Minuteman of 1776 |

One evening in the autumn of 1775, Clark and his companions were sitting round their camp fire in the wilderness. They had just drawn the lines for a fort, and were busy talking about it, when a messenger came with tidings of the bloodshed at Lexington, in far-away Massachusetts. With wild cheers these hunters listened to the story of the minutemen, and, in honor of the event, named their log fort "Lexington."

At the close of this eventful year, three hundred resolute men had gained a foothold in Kentucky. In the trackless wilderness, hemmed in by savage foes, these pioneers with their wives and their children began their struggle for a home. In one short year, this handful of men along the western border were drawn into the midst of the war of the Revolution. From now on, the East and the West had each its own work to do. While Washington and his "ragged Continentals" fought for our independence, "the rear guard of the Revolution," as the frontiersmen were called, were not less busy.

Under their brave leaders, Boone, Clark, and Harrod, in half a dozen little blockhouses and settlements, they were laying the foundations of a great commonwealth, while between them and the nearest eastern settlements were two hundred miles of wilderness. The struggle became so desperate in the fall of 1776 that Clark tramped back to Virginia, to ask the governor for help and to trade for powder.

Virginia was at this time straining every nerve to do her part in the fight against Great Britain, and could not spare men to defend her distant county of Kentucky; but, won by Clark's earnest appeal, the governor lent him, on his own personal security, five hundred pounds of powder. After many thrilling adventures and sharp fighting with the Indians, Clark got the powder down the Ohio River, and distributed it among the settlers. The war with their savage foes was now carried on with greater vigor than ever.

Now we must remember that the vast region north of the Ohio was at this time a part of Canada. In this wilderness of forests and prairies lived many tribes of warlike Indians. Here and there were clusters of French Creole villages, and forts occupied by British soldiers; for with the conquest of Canada these French settlements had passed to the English crown. When the war of the American Revolution broke out, the British government tried to unite all the tribes of Indians against its rebellious subjects in America. In this way the people were to be kept from going west to settle.

|

| Indians attacking a Stockaded Fort on the Frontier |

Colonel Henry Hamilton was the lieutenant governor of Canada, with headquarters at Detroit. It was his task to let loose the redskins that they might burn the cabins of the settlers on the border, and kill their women and children, or carry them into captivity. The British commander supplied the savages with rum, rifles, and powder; and he paid gold for the scalps which they brought him. The pioneers named Hamilton the "hair buyer."

For the next two years Kentucky well deserved the name of "the dark and bloody ground." It was one long, dismal story of desperate fighting, in which heroic women, with tender hearts but iron muscles, fought side by side with their husbands and their lovers.

Meanwhile, Clark was busy planning deeds never dreamed of by those round him. He saw that the Kentucky settlers were losing ground, and were doing little harm to their enemies. The French villages, guarded by British forts, were the headquarters for stirring up, arming, and guiding the savages. It seemed to Clark that the way to defend Kentucky was to carry the war across the Ohio, and to take these outposts from the British. He made up his mind that the whole region could be won for the United States by a bold and sudden march.

In 1777, he sent two hunters as spies through the Illinois country. They brought back word that the French took little interest in the war between England and her colonies; that they did not care for the British, and were much afraid of the pioneers. Clark was a keen and far-sighted soldier. He knew that it took all the wisdom and courage of his fellow settlers to defend their own homes. He must bring the main part of his force from Virginia.

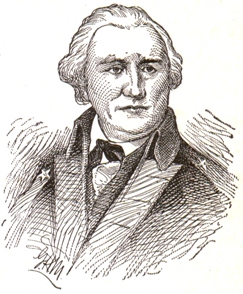

Two weeks before Burgoyne's surrender at Saratoga, he tramped through the woods for the third time, to lay his cause before Patrick Henry, who was then governor of Virginia. Henry was a fiery patriot, and he was deeply moved by the faith and the eloquence of the gallant young soldier.

|

| General George Rogers Clark |

Virginia was at this time nearly worn out by the struggle against King George. A few of the leading patriots, such as Jefferson and Madison, listened favorably to Clark's plan of conquest, and helped him as much as they could. At last the governor made Clark a colonel, and gave him power to raise three hundred and fifty men from the frontier counties west of the Blue Ridge. He also gave orders on the state officers at Fort Pitt for boats, supplies, and powder. All this did not mean much except to show good will and to give the legal right to relieve Kentucky. Everything now depended on Clark's own energy and influence.

During the winter he succeeded in raising one hundred and fifty riflemen. In the spring he took his little army, and, with a few settlers and their families, drifted down the Ohio in flatboats to the place where stands to-day the city of Louisville.

The young leader now weeded out of his army all who seemed to him unable to stand hardship and fatigue. Four companies of less than fifty men each, under four trusty captains, were chosen. All of these were familiar with frontier warfare.

On the 24th of June, the little fleet shot the Falls of the Ohio amid the darkness of a total eclipse of the sun. Clark planned to land at a deserted French fort opposite the mouth of the Tennessee River, and from there to march across the country against Kaskaskia, the nearest Illinois town. He did not dare to go up the Mississippi, the usual way of the fur traders, for fear of discovery.

At the landing place, the army was joined by a band of American hunters who had just come from the French settlements. These hunters said that the fort at Kaskaskia was in good order; and that the Creole militia not only were well drilled, but greatly outnumbered the invading force. They also said that the only chance of success was to surprise the town; and they offered to guide the frontier leader by the shortest route.

With these hunters as guides, Clark began his march of a hundred miles through the wilderness. The first fifty miles led through a tangled and pathless forest. On the prairies the marching was less difficult. Once the chief guide lost his course, and all were in dismay. Clark, fearing treachery, coolly told the man that he should shoot him in two hours if he did not find the trail. The guide was, however, loyal; and, marching by night and hiding by day, the party reached the river Kaskaskia, within three miles of the town that lay on the farther side.

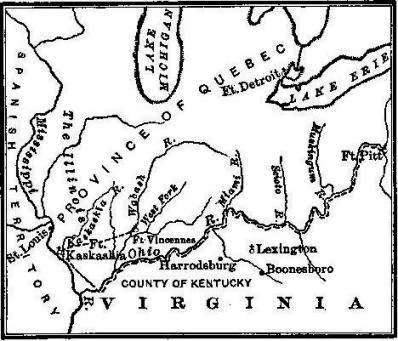

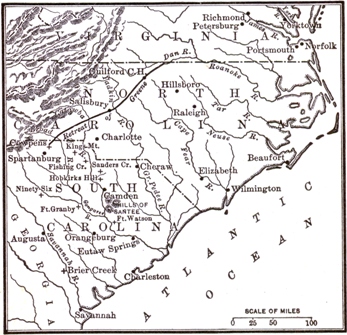

|

| A Map showing the Line of Clark's March |

The chances were greatly against our young leader. Only the speed and the silence of his march gave him hope of success. Under the cover of darkness, and in silence, Clark ferried his men across the river, and spread his little army as if to surround the town.

Fortune favored him at every move. It was a hot July night; and through the open windows of the fort came the sound of music and dancing. The officers were giving a ball to the light-hearted Creoles. All the men of the village were there; even the sentinels had left their posts.

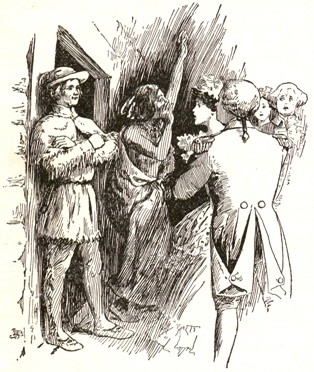

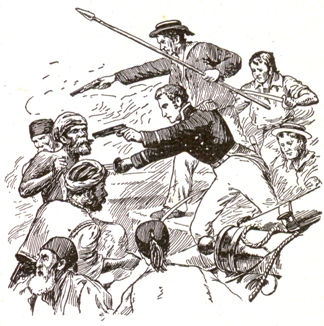

|

| Clark interrupts the Dance |

Leaving a few men at the entrance, Clark walked boldly into the great hall, and, leaning silently against the doorpost, watched the gay dancers as they whirled round in the light of the flaring torches. Suddenly an Indian lying on the floor spied the tall stranger, sprang to his feet, and gave a whoop. The dancing stopped. The young ladies screamed, and their partners rushed toward the doors.

"Go on with your dance," said Clark, "but remember that henceforth you dance under the American flag, and not under that of Great Britain."

The surprise was complete. Nobody had a chance to resist. The town and the fort were in the hands of the riflemen.

Clark now began to make friends with the Creoles. He formed them into companies, and drilled them every day. A priest known as Father Gibault, a man of ability and influence, became a devoted friend to the Americans. He persuaded the people at Cahokia and at other Creole villages, and even at Vincennes, about one hundred and forty miles away on the Wabash, to turn from the British and to raise the American flag. Thus, without the loss of a drop of blood, all the posts in the Wabash valley passed into the hands of the Americans, and the boundary of the rising republic was extended to the Mississippi.

Clark soon had another chance to show what kind of man he was. With less than two hundred riflemen and a few Creoles, he was hemmed in by tribes of faithless savages, with no hope of getting help or advice for months; but he acted as few other men in the country would have dared to act. He had just conquered a territory as large as almost any European kingdom. If he could hold it, it would become a part of the new nation. Could he do it?

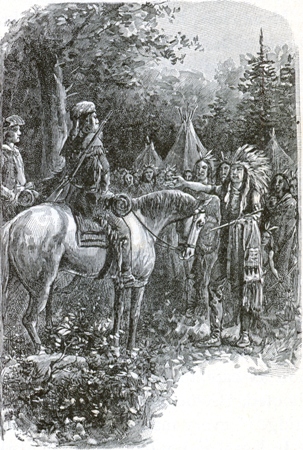

From the Great Lakes to the Mississippi came the chiefs and the warriors to Cahokia to hear what the great chief of the "Long Knives" had to say for himself. The sullen and hideously painted warriors strutted to and fro in the village. At times there were enough of them to scalp every white man at one blow, if they had only dared. Clark knew exactly how to treat them.

One day when it seemed as if there would be trouble at any moment, the fearless commander did not even shift his lodging to the fort. To show his contempt of the peril, he held a grand dance, and "the ladies and gentlemen danced nearly the whole night," while the sullen warriors spent the time in secret council. Clark appeared not to care, but at the same time he had a large room near by filled with trusty riflemen. It was hard work, but the young Virginian did not give up. He won the friendship and the respect of the different tribes, and secured from them pledges of peace. It was little trouble to gain the good will of the Creoles.

Let me tell you of an incident which showed Clark's boldness in dealing with Indians. Years after the Illinois campaign, three hundred Shawnee warriors came in full war paint to Fort Washington, the present site of Cincinnati, to meet the great "Long Knife" chief in council. Clark had only seventy men in the stockade. The savages strode into the council room with a war belt and a peace belt. Full of fight and ugliness, they threw the belts on the table, and told the great pioneer leader to take his choice.

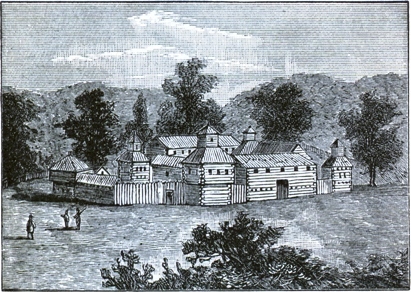

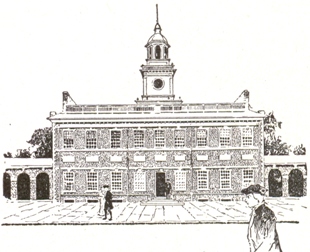

|

|

Fort Washington, a Stockaded Fort on the Ohio, the Present Site of Cincinnati |

Quick as a flash, Clark rose to his feet, swept both the belts to the floor with his cane, stamped upon them, and thrust the savages out of the hall, telling them to make peace at once, or he would drive them off the face of the earth. The Shawnees held a council which lasted all night, but in the morning they humbly agreed to bury the hatchet.

Great was the wrath of Hamilton, the "hair buyer general," when he heard what the young Virginian had done. He at once sent out runners to stir up the savages; and, in the first week of October, he set out in person from Detroit with five hundred British regulars, French, and Indians. He recaptured Vincennes without any trouble. Clark had been able to leave only a few of the men he had sent there, and some of them deserted the moment they caught sight of the redcoats.

If Hamilton had pushed on through the Illinois country, he could easily have crushed the little American force; but it was no easy thing to march one hundred and forty miles over snow-covered prairies, and so the British commander decided to wait until spring.

When Clark heard of the capture of Vincennes, he knew that he had not enough men to meet Hamilton in open fight. What was he to do? Fortune again came to his aid.

The last of January, he heard that Hamilton had sent most of his men back to Detroit; that the Indians had scattered among the villages; and that the British commander himself was now wintering at Vincennes with about a hundred men. Clark at once decided to do what Hamilton had failed to do. Having selected the best of his riflemen, together with a few Creoles, one hundred and seventy men in all, he set out on February 7 for Vincennes.

All went well for the first week. They marched rapidly. Their rifles supplied them with food. At night, as an old journal says, they "broiled their meat over the huge camp fires, and feasted like Indian war dancers." After a week the ice had broken up, and the thaw flooded everything. The branches of the Little Wabash now made one great river five miles wide, the water even in the shallow places being three feet deep.

It took three days of the hardest work to ferry the little force across the flooded plain. All day long the men waded in the icy waters, and at night they slept as well as they could on some muddy hillock that rose above the flood. By this time they had come so near Vincennes that they dared not fire a gun for fear of being discovered.

Marching at the head of his chilled and foot-sore army, Clark was the first to test every danger.

"Come on, boys!" he would shout, as he plunged into the flood.

Were the men short of food? "I am not hungry," he would say, "help yourself." Was some poor fellow chilled to the bone? "Take my blanket," said Clark, "I am glad to get rid of it."

In fact, as peril and suffering increased, the courage and the cheerfulness of the young leader seemed to grow stronger.

On February 17, the tired army heard Hamilton's sunrise gun on the fort at Vincennes, nine miles away, boom across the muddy flood.

Their food had now given out. The bravest began to lose heart, and wished to go back. In hastily made dugouts the men were ferried, in a driving rain, to the eastern bank of the Wabash; but they found no dry land for miles round. With Clark leading the way, the men waded for three miles with the water often up to their chins, and camped on a hillock for the night. The records tell us that a little drummer boy, whom some of the tallest men carried on their shoulders, made a deal of fun for the weary men by his pranks and jokes.

Death now stared them in the face. The canoes could find no place to ford. Even the riflemen huddled together in despair. Clark blacked his face with damp gunpowder, as the Indians did when ready to die, gave the war whoop, and leaped into the ice-cold river. With a wild shout the men followed. The whole column took up their line of march, singing a merry song. They halted six miles from Vincennes. The night was bitterly cold, and the half-frozen and half-starved men tried to sleep on a hillock.

The next morning the sun rose bright and beautiful. Clark made a thrilling speech and told his famished men that they would surely reach the fort before dark. One of the captains, however, was sent with twenty-five trusty riflemen to bring up the rear, with orders to shoot any man that tried to turn back.

The worst of all came when they crossed the Horseshoe Plain, which the floods had made a shallow lake four miles wide, with dense woods on the farther side. In the deep water the tall and the strong helped the short and the weak. The little dugouts picked up the poor fellows who were clinging to bushes and old logs, and ferried them to a spot of dry land. When they reached the farther shore, so many of the men were chilled that the strong ones had to seize those half-frozen, and run them up and down the bank until they were able to walk.

One of the dugouts captured an Indian canoe paddled by some squaws. It proved a rich prize, for in it were buffalo meat and some kettles. Broth was soon made and served to the weakest. The strong gave up their share. Then amid much joking and merry songs, the column marched in single file through a bit of timber. Not two miles away was Vincennes, the goal of all their hopes.

A Creole who was out shooting ducks was captured. From him it was learned that nobody suspected the coming of the Americans, and that two hundred Indians had just come into town.

With the hope that the Creoles would not dare to fight, and that the Indians would escape, Clark boldly sent the duck hunter back to town with the news of his arrival. He sent warning to the Creoles to remain in their houses, for he came only to fight the British.

So great was the terror of Clark's name that the French shut themselves up in their houses, while most of the Indians took to the woods. Nobody dared give a word of warning to the British.

Just after dark the riflemen marched into the streets of the village before the redcoats knew what was going on.

Crack! crack! sharply sounded half a dozen rifles outside the fort.

"That is Clark, and your time is short!" cried Captain Helm, who was Hamilton's prisoner at this time; "he will have this fort tumbling on your heads before to-morrow morning."

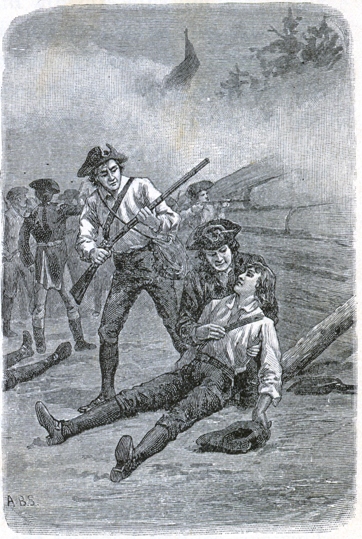

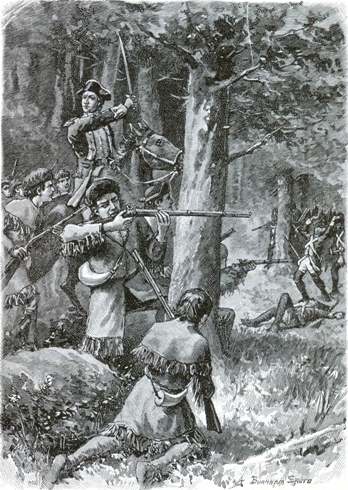

|

| Defending a Frontier Fort against the British and Indians |

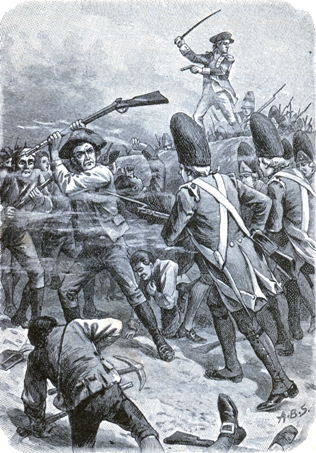

During the night the Americans threw up an intrenchment within rifle shot of the fort, and at daybreak opened a hot fire into the portholes. The men begged their leader to let them storm the fort, but he dared not risk their lives. A party of Indians that had been pillaging the Kentucky settlements came marching into the village, and were caught red-handed with scalps hanging at their belts.

Clark was not slow to show his power.

"Think, men," he said sternly, "of the cries of the widows and the fatherless on our frontier. Do your duty."

Six of the savages were tomahawked before the fort, where the garrison could see them, and their dead bodies were thrown into the river.

The British defended their fort for a few days, but could not stand against the fire of the long rifles. It was sure death for a gunner to try to fire a cannon. Not a man dared show himself at a porthole, through which the rifle bullets were humming like mad hornets.

Hamilton the "hair buyer" gave up the defense as a bad job, and surrendered the fort, defended by cannon and occupied by regular troops, as he says in his journal, "to a set of uncivilized Virginia backwoodsmen armed with rifles."

Tap! tap! sounded the drums, as Clark gave the signal, and down came the British colors.

Thirteen cannon boomed the salute over the flooded plains of the Wabash, and a hundred frontier soldiers shouted themselves hoarse when the stars and stripes went up at Vincennes, never to come down again.

The British authority over this region was forever at an end. It only remained for Clark to defend what he had so gallantly won.

Of all the deeds done west of the Alleghanies during the war of the Revolution, Clark's campaign, in the region which seemed so remote and so strange to our forefathers, is the most remarkable. The vast region north of the Ohio River was wrested from the British crown. When peace came, a few years later, the boundary lines of the United States were the Great Lakes on the north, and on the west the Mississippi River.

A splendid monument overlooks the battlefield of Saratoga. Heroic bronze statues of Schuyler, Gates, and Morgan, three of the four great leaders in this battle, stand each in a niche on three faces of the obelisk. On the south side the space is empty. The man who led the patriots to victory forfeited his place on this monument. What a sermon in stone is the empty niche on that massive granite shaft! We need no chiseled words to tell us of the great name so gallantly won by Arnold the hero, and so wretchedly lost by Arnold the traitor.

Only a few months after Benedict Arnold had turned traitor, and was fighting against his native land, he was sent by Sir Henry Clinton, the British commander, to sack and plunder in Virginia. In one of these raids a captain of the colonial army was taken prisoner.

"What will your people do with me if they catch me?" Arnold is said to have asked his prisoner.

"They will cut off your leg that was shot at Quebec and Saratoga," said the plucky and witty officer, "and bury it with the honors of war, and hang the rest of your body on a gibbet."

This bold reply of the patriot soldier showed the hatred and the contempt in which Arnold was held by all true Americans; it also hints at an earlier fame which this strange and remarkable man had won in fighting the battles of his country.

Now that war with the mother country had begun, an attack upon Canada seemed to be an act of self-defense; for through the valley of the St. Lawrence the colonies to the south could be invaded. The "back door," as Canada was called, which was now open for such invasion, must be tightly shut. In fact it was believed that Sir Guy Carleton, the governor of Canada, was even now trying to get the Indians to sweep down the valley of the Hudson, to harry the New England frontier.

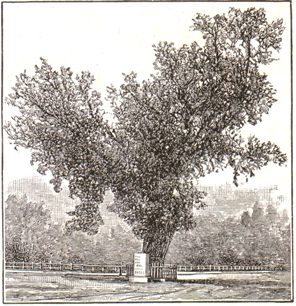

|

|

The Washington Elm in Cambridge, Massachusetts, under which Washington took Command |

Meanwhile, under the old elm in Cambridge, Washington had taken command of the Continental army. Shortly afterwards he met Benedict Arnold for the first time. The great Virginian found the young officer a man after his own heart. Arnold was at this time captain of the best-drilled and best-equipped company that the patriot army could boast. He had already proved himself a man of energy and of rare personal bravery.

Before his meeting with Washington, Arnold had hurried spies into Canada to find out the enemy's strength; and he had also sent Indians with wampum, to make friends with the redskins along the St. Lawrence. Some years before, he had been to Canada to buy horses; and through his friends in Quebec and in Montreal he was now able to get a great deal of information, which he promptly sent to Congress.

Congress voted to send out an expedition. An army was to enter Canada by the way of the Kennebec and Chaudière rivers; there to unite forces with Montgomery, who had started from Ticonderoga; and then, if possible, to surprise Quebec.

The patriot army of some eighteen thousand men was at this time engaged in the siege of Boston. During the first week in September, orders came to draft men for Quebec. For the purpose of carrying the troops up the Kennebec River, a force of carpenters was sent ahead to build two hundred bateaux, or flat-bottomed boats. To Arnold, as colonel, was given the command of the expedition. For the sake of avoiding any ill feeling, the officers were allowed to draw lots. So eager were the troops to share in the possible glories of the campaign that several thousand at once volunteered.

About eleven hundred men were chosen, the very flower of the Continental army. More than one half of these came from New England; three hundred were riflemen from Pennsylvania and from Virginia, among whom were Daniel Morgan and his famous riflemen from the west bank of the Potomac.

On September 13, the little army left Cambridge and marched through Essex to Newburyport. The good people of this old seaport gave the troops an ovation, on their arrival Saturday night. They escorted them to the churches on Sunday, and on Tuesday morning bade them good-by, "with colors flying, drums and fifes playing, the hills all around being covered with pretty girls weeping for their departing swains."

On the following Thursday, with a fair wind, the troops reached the mouth of the Kennebec, one hundred and fifty miles away. Working their way up the river, they came to anchor at what is now the city of Gardiner. Near this place, the two hundred bateaux had been hastily built of green pine. The little army now advanced six miles up the river to Fort Western, opposite the present city of Augusta. Here they rested for three days, and made ready for the ascent of the Kennebec.

An old journal tells us that the people who lived near prepared a grand feast for the soldiers, with three bears roasted whole in frontier fashion, and an abundance of venison, smoked salmon, and huge pumpkin pies, all washed down with plenty of West India rum.

Among the guests at this frontier feast was a half-breed Indian girl named Jacataqua, who had fallen in love with a handsome young officer of the expedition. This officer was Aaron Burr, who afterwards became Vice President of the United States. When the young visitor found that the wives of two riflemen, James Warner and Sergeant Grier, were going to tramp to Canada with the troops, she, too, with some of her Indian friends, made up her mind to go with them. This trifling incident, as we shall see later, saved the lives of many brave men.

The season was now far advanced. There must be no delay, or the early Canadian winter would close in upon them. The little army was divided into four divisions. On September 25, Daniel Morgan and his riflemen led the advance, with orders to go with all speed to what was called the Twelve Mile carrying place. The second division, under the command of Colonel Greene, started the next day. Then came the third division, under Major Meigs, while Colonel Enos brought up the rear. There were fourteen companies, each provided with sixteen bateaux.

These boats were heavy and clumsy. When loaded, four men could hardly haul or push them through the shallow channels, or row them against the strong current of the river. It was hard and rough work. And those dreadful carrying places! Before they reached Lake Megantic, they dragged these boats, or what was left of them, round the rapids twenty-four times. At each carrying place, kegs of powder and of bullets, barrels of flour and of pork, iron kettles, and all manner of camp baggage had to be unpacked from the boats, carried round on the men's backs, and reloaded again. Sometimes the "carry" was only a matter of a few rods, and again it was two miles long.

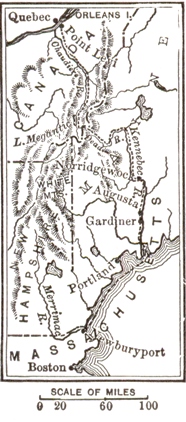

|

|

A Map of Arnold's Route to Quebec |

From the day the army left Norridgewock, the last outpost of civilization, troubles came thick and fast. Water from the leaky boats spoiled the dried codfish and most of the flour. The salt beef was found unfit for use. There was now nothing left to eat but flour and pork. The all-day exposure in water, the chilling river fogs at night, and the sleeping in uniforms which were frozen stiff even in front of the camp fires, all began to thin the ranks of these sturdy backwoodsmen.

On October 12, Colonel Enos and the rear guard reached the Twelve Mile carrying place. The army that had set out from Fort Western with nearly twelve hundred men could now muster only nine hundred and fifty well men. And yet they were only beginning the most perilous stage of their journey. All about them stood the dark and silent wilderness, through which they were to make their way for sixteen miles, to reach the Dead River. In this dreaded route there were four carrying places. The last was three miles long, a third of which was a miry spruce and cedar swamp. It took five days of hardest toil to cut their way through the unbroken wilderness. Fortunately, the hunters shot four moose and caught plenty of salmon trout.

Now began the snail-like advance for eighty-six miles up the crooked course of the Dead River. Sometimes they cut their way through the thickets and the underbrush, but oftener they waded along the banks. Then came a heavy rainstorm, which grew into a hurricane during the night. The river overflowed its banks for a mile or more on either side. Many of the boats sank or were dashed to pieces. Barrels of pork and of flour were swept away. For the next ten days, these heroic men seemed to be pressing forward to a slow death by starvation. Each man's ration was reduced to half a pint of flour a day.

The old adage tells us that misfortunes never come singly. The rear guard under Colonel Enos, with its trail hewn out for it, had carried the bulk of the supplies; but, after losing most of the provisions in the freshet, he refused any more flour for his half-starved comrades at the front.

On October 25, the rear guard having caught up with Greene's division, which was in the worst plight of all, encamped at a place called Ledge Falls. At a council of war held in the midst of a driving snowstorm, Enos himself voted at first to go forward; but afterwards he decided to go back. So the rear guard, grudgingly giving up two barrels of flour, turned their backs, and, in spite of the jeers and the threats of their comrades, started home. Greene and his brave fellows showed no signs of faltering, but, as a diary reads, "took each man his duds to his back, bid them adieu, and marched on."

Just over the boundary between Maine and Canada there was a great swamp. In this bog two companies lost their way, and waded knee-deep in the mire for ten miles in endless circles. Reaching a little hillock after dark, they stood up all night long to keep from freezing. Each man was for himself in the struggle for life. The strong dared not halt to help the weak for fear they too should perish.

"Alas! alas!" writes one soldier, "these horrid spectacles! my heart sickens at the recollection."

That each man might fully realize how little food was left, a final division was made of the remaining provisions. Five pints of flour were given to each man! This must last him for a hundred miles through the pathless wilderness, a tramp of at least six days. In the ashes of the camp fire, each man baked his flour, Indian fashion, into five little cakes. Though the officers coaxed and threatened, some of the poor frantic fellows ate all their cakes at one meal.

On November 2, our little army, scattered for more than forty miles along the banks of the Chaudière River, was still dragging out its weary way. Tents, boats, and camp supplies were all gone, except here and there a tin camp kettle or an ax. A rifleman tells us that one day he roasted and chewed his shot pouch, and adds, "in a short time there was not a shot pouch to be seen among all those in my view." For four days this man had not eaten anything except a squirrel skin, which he had picked up some days before.

Several dogs that had faithfully followed their masters were now killed and roasted; and even their feet, skin, and entrails were eaten. Captain Dearborn tells us how downcast he was when he was forced to kill and eat his fine Newfoundland dog. He writes, "we even pounded up the dog's bones and made broth for another meal."

A dozen men, who had been left behind to die, caught a stray horse that had run away from some settlement. They shot it and ate heartily of the flesh while they rested, and at last reached the main army. For seven days these men had had nothing for food but roots and black birch bark.

The Indian girl Jacataqua, with a pet dog, still followed the troops. She proved herself of the greatest service as a guide. She knew, also, about roots and herbs, and these she prepared in Indian fashion for the sick and the injured. The men did not dare to kill her dog, for she threatened to leave them to their fate if they harmed the faithful animal.

At one place James Warner, whose wife Jemima was marching with the troops, lagged behind, and, before his wife knew it, sank exhausted. The faithful woman ran back alone, and stayed with him until he died. She buried him with leaves; and then, taking his musket and girding on his cartridge belt, she hurried breathless and panting for twenty miles, until she caught up with the troops. And as for Sergeant Grier's good wife, she tramped and starved her way with the men. No wonder that one writer, a boy of seventeen at the time, says, as he saw this plucky woman wading through the rivers, "My mind was humbled, yet astonished at the exertions of this good woman."

|

| Arnold's Men marching through the Flooded Wilderness |

Where was the bold commander all this time, the man who was to lead these sturdy riflemen to easy victory? After paddling thirteen miles across Lake Megantic, Arnold performed one of those brilliant and reckless deeds for which he was noted. Perhaps no other man in the American army would have dared to do what he did. The remnant of his famishing soldiers must be saved, and the time was short.

On October 28, he started down the swollen Chaudière River with only a few men and without a guide. Sartigan, the nearest French settlement where provisions could be bought, was nearly seventy miles away. The swift current carried the frail canoes down the first twenty miles in two hours. Here through the rapids, there over hidden ledges, now escaping the driftwood and the sharp-edged rocks, Arnold and his men wrestled with the angry river.

At one place they plunged over a fall, and every canoe was capsized. Six of the men found themselves swimming in a large rock-bound basin, while the angry flood thundered thirty feet over the ledges just beyond them. The men swam ashore, thankful to escape death.

The last twenty miles was tramped through the wilderness, but such was the energy of their leader that Sartigan was reached on the evening of the second day. Long before daybreak, cattle and bags of flour were ready, and, with a relief party of French Canadians on horseback, Arnold was on his way back to the starving army.

Four days later, from the famished men in the frozen wilderness was heard far and wide the joyful cry, "Provisions!" "Provisions!"

The cry was echoed from hill to hill, and along the snow-covered banks of the great river. The grim fight for life was over. They had won. How like a pack of famished wolves did they kill, cook, and devour the cattle!

The next day, two companies dashed through the icy waters of the Du Loup River, and, shortly afterwards, greeted with cheers the first house they had seen for thirty days. Six miles beyond, was Sartigan,—a half dozen log cabins and a few Indian wigwams.

A snowstorm now set in, but the joyful men hastily built huts of pine boughs, kindled huge camp fires, and waited for the stragglers. The severe Canadian winter was well begun. It kept on snowing heavily. As Quebec might be reënforced at any moment, every captain was ordered to get his men over the remaining fifty-four miles with all possible speed.

"Quebec!" "Quebec!" was in everybody's mouth.

Five days later, on November 9, the patriots reached Point Levi, a little French village opposite Quebec. The people looked on with astonishment as they straggled out of the woods, a worn-out army of perhaps six hundred men, with faces haggard, clothing in tatters, and many barefooted and bareheaded. Over eighty had died in the wilderness, and a hundred were on the sick list. So pitiful and so ludicrous was their appearance that one man wrote in his diary that they "resembled those animals of New Spain called orang-outangs," and "unlike the children of Israel, whose clothes waxed not old in the wilderness, theirs hardly held together."

With his usual bravado, Arnold planned to capture the "Gibraltar of America" at one stroke. He little knew that, a few days before, some treacherous Indians had warned the British commander of his approach.

On the night of November 13, Arnold ferried five hundred of his men across the St. Lawrence, and climbed to the Heights of Abraham, at the very place where Wolfe had climbed to victory sixteen years before. At daybreak the walls of the city were covered with soldiers and with citizens. Within half a mile of the walls, which fairly bristled with cannon, the ragged soldiers halted and began to cheer lustily. The redcoats shouted back their defiance. Arnold wrote a letter to the governor of Quebec, demanding the surrender of the city. The bearer of the letter, although under a flag of truce, was not even allowed to come near the walls.

After six days the little army slipped away one dark night, and tramped to a village some twenty miles to the west of Quebec. Here they hoped to join forces with Montgomery, who had already captured Montreal, and then come back to renew the siege.

Ten days later, on December 1, Arnold paraded his troops in front of the village church to greet Montgomery with his army. The united forces, still less than a thousand men, now trudged their way back to Quebec. On arriving there, Montgomery boldly demanded the surrender of the town.

Meanwhile, on November 19, Sir Guy Carleton had left Montreal, and, having made his way down the river, in the disguise of a farmer, slipped into Quebec. This was the salvation of Canada.

The British general was an able soldier. He at once took energetic steps for the defense of the city. At every available point he built blockhouses, barricades, and palisades; and mounted one hundred and fifty cannon. He took five hundred sailors from the war vessels to help man the guns, and thus increased the garrison to eighteen hundred fighting men.

For two weeks the patriot army fired their little three-pounders, and threw several hundred "fire pills," as the men called them, against the granite ramparts and into the town. Even the women laughed at them, for they did no more harm than so many popguns. The redcoats kept up the bloodless contest by raking with their cannon the patriots' feeble breastworks of ice and snow.

Montgomery spoke hopefully to his men, but in his heart was despair. How could he ever go home without taking Quebec? Washington and Congress expected it, and the people at home were waiting for it. When he bade his young wife good-by at their home on the Hudson, he said, "You shall never blush for your Montgomery." What was his duty now? Should he not make at least one desperate attempt? Did not Wolfe take equally desperate chances and win deathless renown? At last it was decided to wait for a dark night, in which to attack the Lower Town.

At midnight on the last day of 1775, came the snowstorm so long awaited. The word was given, and about half past three the columns marched to the assault. Every man pinned to his hat a piece of white paper, on which was written the motto of Morgan's far-famed riflemen, "Liberty or Death!"

Arnold and Morgan, with about six hundred men, were to make the attack on one side of the town, and Montgomery, with three hundred men, on the other side.

The storm had become furious. With their heads down and their guns under their coats, the men had enough to do to keep up with Arnold as he led the attack. Presently a musket ball shattered his leg and stretched him bleeding in the snow. Morgan at once took command, and, cheering on his men, carried the batteries; then, forcing his way into the streets of the Lower Town, he waited for the promised signal from Montgomery.

Meantime, the precious moments slipped by, while the young Montgomery was forcing his way through the darkness and the huge snowdrifts, along the shores of the St. Lawrence. When the head of his column crept cautiously round a point of the steep cliff, they came face to face with the redcoats standing beside their cannon with lighted matches.

"On, boys, Quebec is ours!" shouted Montgomery, as he sprang forward.

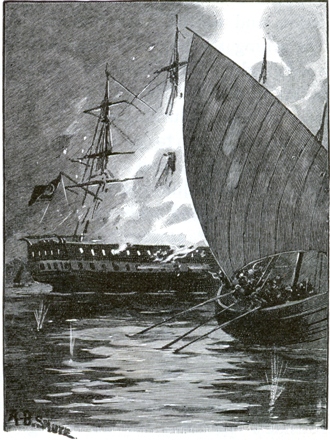

|

| The Midnight Attack on Quebec |

A storm of grape and canister swept the narrow pass, and the young general fell dead. In dismay and confusion, the column gave way. The command to retreat was hastily given and obeyed. Strange to say, so dazed were the British by the fierce attack that they, too, ran away, but soon rallied. The driving snow quickly covered the dead and the wounded in a funeral shroud.

The enemy were now free to close in upon Morgan and his riflemen, on the other side of the town. All night long, fierce hand to hand fighting went on in the narrow streets, amid the howling storm of driving snow; and the morning light broke slowly upon scenes of confusion and horror. Morgan and his men fought like heroes, but they were outnumbered, and were forced to surrender.

The rest of this sad story may be briefly told. Arnold was given the chief command. Although he was weakened from loss of blood, and helpless from his shattered leg, nothing could break his dauntless will. Expecting the enemy at any moment to attack the hospital, he had his pistols and his sword placed on his bed, that he might die fighting. From that bedside, he kept his army of seven hundred men sternly to its duty. In a month he was out of doors, hobbling about on crutches, and hopeful as ever of success.

Washington sent orders for Arnold to stand his ground, and as late as January 27 wrote him that "the glorious work must be accomplished this winter." With bulldog grip, Arnold obeyed orders, and kept up the hopeless siege. During the winter, more troops came to his help from across the lakes, but they only closed the gaps made by hardships and smallpox.

On the 14th of March, a flag of truce was again sent to the city, demanding its surrender.

"No flag will be received," said the officer of the day, "unless it comes to implore the mercy of the king."

A wooden horse was mounted on the walls near the famous old St. John's gate, with a bundle of hay before it. Upon the horse was tacked a placard, on which was written, "When this horse has eaten this bunch of hay, we will surrender."

Although they were short of food, and were forced to tear down the houses for firewood, the garrison was safe and quite comfortable behind the snow-covered ramparts.

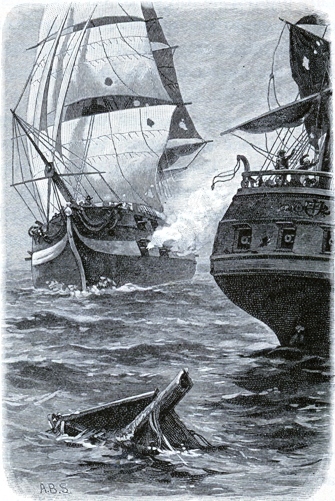

The end of the coldest winter ever known in Canada save one came at last. The river was full of ice during the first week of May. A few days later, three men-of-war forced their way up the St. Lawrence through the floating ice, and relieved the besieged city. The salute of twenty-one guns fired by the fleet was joyful music to the people of Quebec. Amid the thundering of the guns from the citadel, the great bell of the Cathedral clanged the death knell to Arnold's hopes.

The "Gibraltar of America" still remained in the possession of England.

In 1775, in Virginia, the patriots forced the royal governor, Lord Dunmore, to take refuge on board a British man-of-war in Norfolk Harbor. In revenge, the town of Norfolk, the largest and the most important in the Old Dominion, was, on New Year's Day, 1776, shelled and destroyed. This bombardment, and scores of other less wanton acts of the men-of-war, alarmed every coastwise town from Maine to Georgia.

Early in the fall of 1775, the British government planned to strike a hard blow against the Southern colonies. North Carolina was to be the first to receive punishment. It was the first colony, as perhaps you know, to take decided action in declaring its independence from the mother country. To carry out the intent of the British, Sir Henry Clinton, with two thousand troops, sailed from Boston for the Cape Fear River.

The minutemen of the Old North State rallied from far and near, as they had done in Massachusetts after the battle of Lexington. Within ten days, there were ten thousand men ready to fight the redcoats. And so when Sir Henry arrived off the coast, he decided, like a prudent man, not to land; but cruised along the shore, waiting for the coming of war vessels from England.

This long-expected fleet was under the command of Sir Peter Parker. Baffled by head winds, and tossed about by storms, the ships were nearly three months on the voyage, and did not arrive at Cape Fear until the first of May. There they found Clinton.

Sir Peter and Sir Henry could not agree as to what action was best. Clinton, with a wholesome respect for the minutemen of the Old North State, wished to sail to the Chesapeake; while Lord Campbell, the royal governor of South Carolina, who was now an officer of the fleet, begged that the first hard blow should fall upon Charleston. He declared that, as soon as the city was captured, the loyalists would be strong enough to restore the king's power. Campbell, it seems, had his way at last, and it was decided to sail south, to capture Charleston.

Meanwhile, the people of South Carolina had received ample warning. So they were not surprised when, on the last day of May, a British fleet under a cloud of canvas was seen bearing up for Charleston. On the next day, Sir Peter Parker cast anchor off the bar, with upwards of fifty war ships and transports. Affairs looked serious for the people of this fair city; but they were of fighting stock, and, with the war thus brought to their doors, were not slow to show their mettle.

For weeks the patriots had been pushing the works of defense. Stores and warehouses were leveled to the ground, to give room for the fire of cannon and muskets from various lines of earthworks; seven hundred wagons belonging to loyalists were pressed into service, to help build redoubts; owners of houses gave the lead from their windows, to be cast into bullets; fire boats were made ready to burn the enemy's vessels, if they passed the forts. The militia came pouring in from the neighboring colonies until there were sixty-five hundred ready to defend the city.

It was believed that a fort built on the southern end of Sullivan's Island, within point-blank shot of the channel leading into Charleston Harbor, might help prevent the British fleet from sailing up to the city. At all events it would be worth trying. So, in the early spring of 1776, Colonel William Moultrie, a veteran of the Indian wars, was ordered to build a square fort large enough to hold a thousand men.

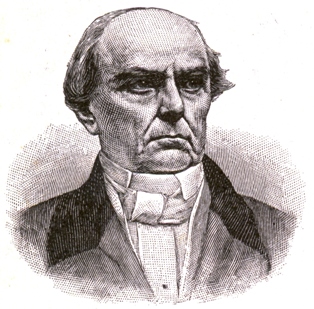

|

| Colonel William Moultrie |

The use of palmetto logs was a happy thought. Hundreds of negroes were set at work cutting down the trees and hauling them to the southern end of the island. The long straight logs were laid one upon another in two parallel rows sixteen feet apart, and were bound together with cross timbers dovetailed and bolted into the logs. The space between the two rows of logs was filled with sand. This made the walls of the fort.

The cannon were mounted upon platforms six feet high, which rested upon brick pillars. Upon these platforms the men could stand and fire through the openings. The rear of the fort and the eastern side were left unfinished, being merely built up seven feet with logs. Thirty-one cannon were mounted, but only twenty-five could at any one time be brought to bear upon the enemy.

On the day of the battle, there were about four hundred and fifty men in the fort, only thirty of whom knew anything about handling cannon. But most of the garrison were expert riflemen, and it was soon found that their skill in small arms helped them in sighting the artillery.

One day early in June, General Charles Lee, who had been sent down to take the chief command, went over to the island to visit the fort. As the old-time soldier, who had seen long service in the British army, looked over the rudely built affair, and saw that it was not even finished, he gravely shook his head.

"The ships will anchor off there," said he to Moultrie, pointing to the channel, "and will make your fort a mere slaughter pen."

The weak-kneed general, who afterwards sold himself to the British, went back and told Governor Rutledge that the only thing to do was to abandon the fort. The governor, however, was made of better stuff, and, besides, had the greatest faith in Colonel Moultrie. But he did ask his old friend if he thought he really could defend the cob-house fort, which Lee had laughed to scorn.

Moultrie was a man of few words, and replied simply, "I think I can."

"General Lee wishes you to give up the fort," added Rutledge, "but you are not to do it without an order from me, and I will sooner cut off my right hand than write one."

The idea of retreating seems never to have occurred to the brave commander.

"I was never uneasy," wrote Moultrie in after years, "because I never thought the enemy could force me to retire."

It was indeed fortunate that Colonel Moultrie was a stout-hearted man, for otherwise he might well have been discouraged. A few days before the battle, the master of a privateer, whose vessel was laid up in Charleston harbor, paid him a visit. As the two friends stood on the palmetto walls, looking at the fleet in the distance, the naval officer said, "Well, Colonel Moultrie, what do you think of it now?"

Moultrie replied, "We shall beat them."

"Sir," exclaimed his visitor, pointing to the distant men-of-war, "when those ships come to lay alongside of your fort, they will knock it down in less than thirty minutes."

"We will then fight behind the ruins," said the stubborn patriot, "and prevent their men from landing."

The British plan of attack, to judge from all military rules, should have been successful. First, the redcoat regulars were to land upon Long Island, lying to the north, and wade across the inlet which separates it from Sullivan's Island. Then, after the war ships had silenced the guns in the fort, the land troops were to storm the position, and thus leave the channel clear for the combined forces to sail up and capture the city.

If a great naval captain like Nelson or Farragut had been in command, probably the ships would not have waited a month, but would at once have made a bold dash past the fort, and straightway captured Charleston. Sir Peter, however, was slow, and felt sure of success. For over three weeks he delayed the attack, thus giving the patriots more time for completing their defenses.

Friday morning, June 28, was hot, but bright and beautiful. Early in the day, Colonel Moultrie rode to the northern end of the island to see Colonel Thompson. The latter had charge of a little fort manned by sharpshooters, and it was his duty to prevent Clinton's troops from getting across the inlet.

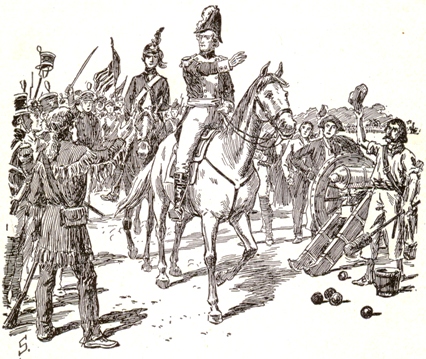

Suddenly the men-of-war begin to spread their topsails and raise their anchors. The tide is coming in. The wind is fair. One after another, the war ships get under way and come proudly up the harbor, under full sail. The all-important moment of Moultrie's life is at hand. He puts spurs to his horse and gallops back to the palmetto fort.

"Beat the long roll!" he shouts to his officers, Colonel Motte and Captain Marion.

The drums beat, and each man hurries to his chosen place beside the cannon. The supreme test for the little cob-house fort has come. The men shout, as a blue flag with a crescent, the colors of South Carolina, is flung to the breeze.

Just as a year before, the people of Boston crowded the roofs and the belfries, to watch the outcome of Bunker Hill; so now, the old men and the women and children of Charleston cluster on the wharves, the church towers, and the roofs, all that hot day, to watch the duel between the palmetto fort and the British fleet.

Sir Peter Parker has a powerful fleet. He is ready to do his work. Two of his ships carry fifty guns each, and four carry twenty-eight guns each. With a strong flood tide and a favorable southwest wind, the stately men-of-war sweep gracefully to their positions. Moultrie's fighting blood is up, and his dark eyes flash with delight. The men of South Carolina, eager to fight for their homes, train their cannon upon the war ships.

"Fire! fire!" shouts Moultrie, as the men-of-war come within point-blank shot. The low palmetto cob house begins to thunder with its heavy guns.

A bomb vessel casts anchor about a mile from the fort. Puff! bang! a thirteen-inch shell rises in the air with a fine curve and falls into the fort. It bursts and hurls up cart loads of sand, but hurts nobody. Four of the largest war ships are now within easy range. Down go the anchors, with spring ropes fastened to the cables, to keep the vessels broadside to the fort. The smaller men-of-war take their positions in a second line, in the rear. Fast and furious, more than one hundred and fifty cannon bang away at the little inclosure.

But, even from the first, things did not turn out as the British expected. After firing some fifty shells, which buried themselves in the loose sand and did not explode, the bomb vessel broke down.

About noon, the flagship signaled to three of the men-of-war, "Move down and take position southwest of the fort."

Once there, the platforms inside the fort could be raked from end to end. As good fortune would have it, two of these vessels, in attempting to carry out their orders, ran afoul of each other, and all three stuck fast on the shoal on which is now the famed Fort Sumter.

How goes the battle inside the fort? The men, stripped to the waist and with handkerchiefs bound round their heads, stand at the guns all that sweltering day, with the coolness and the courage of old soldiers. The supply of powder is scant. They take careful aim, fire slowly, and make almost every shot tell. The twenty-six-pound balls splinter the masts, and make sad havoc on the decks. Crash! crash! strike the enemy's cannon balls against the palmetto logs. The wood is soft and spongy, and the huge shot either bury themselves without making splinters, or else bound off like rubber balls.

Meanwhile, where was Sir Henry Clinton? For nearly three weeks he had been encamped with some two thousand men on the sand bar known as Long Island. The men had suffered fearfully from the heat, from lack of water, and from the mosquitoes.

During the bombardment of Fort Sullivan, Sir Henry marched his men down to the end of the sand island, but could not cross; for the water in the inlet proved to be seven feet deep even at low tide. Somebody had blundered about the ford. The redcoats, however, were paraded on the sandy shore while some armed boats made ready to cross the inlet. The grapeshot from two cannon, and the bullets of Colonel Thompson's riflemen, so raked the decks that the men could not stay at their posts. Memories of Bunker Hill, perhaps, made the British officers a trifle timid about crossing the inlet, and marching over the sandy shore, to attack intrenched sharpshooters. Thus it happened that Clinton and his men, through stupidity, were kept prisoners on the sand island, mere spectators of the thrilling scene. They had to content themselves with fighting mosquitoes, under the sweltering rays of a Southern sun.

|

| Defending the Palmetto Fort |

All this time, Sir Peter was doing his best to pound the fort down. The fort trembled and shook, but it stood. Moultrie and his men, with perfect coolness and with steady aim, made havoc of the war ships. Colonel Moultrie prepared grog by the pailful, which, with a negro as helper, he dipped out to the tired men at the guns.

"Take good aim, boys," he said, as he passed from gun to gun, "mind the big ships, and don't waste the powder."

The mainmast of the flagship Bristol was hit nine times, and the mizzenmast was struck by seven thirty-two-pound balls, and had to be cut away. In short, the flagship was pierced so many times that she would have sunk had not the wind been light and the water smooth. While the battle raged in all its fury, the carpenters worked like beavers to keep the vessel afloat.

At one time a cannon ball shot off one of the cables, and the ship swung round with the tide.

"Give it to her, boys!" shouts Moultrie, "now is your time!" and the cannon balls rake the decks from stem to stern.

The captain of the flagship was struck twice, Lord Campbell was hurt, and one hundred men were either killed or wounded. Once Sir Peter was the only man left on the quarter-deck, and he himself was twice wounded.

The other big ship, the Experiment, fared fully as hard as did the flagship. The captain lost his right arm, and nearly a hundred of his men were killed or wounded.

In fact, these two vessels were about to be left to their fate, when suddenly the fire of the fort slackened.

"Fire once in ten minutes," orders Colonel Moultrie, for the supply of powder is becoming dangerously small.

An aid from General Lee came running over to the fort. "When your powder is gone, spike your guns and retreat," wrote the general.

Moultrie was not that kind of man.

Between three and five o'clock in the afternoon, the fire of the fort almost stopped. The British thought the guns were silenced. Not a bit of it! Even then a fresh supply of five hundred pounds of powder had nearly reached the fort. It came from Governor Rutledge with a note, saying, "Honor and victory, my good sir, to you and your worthy men with you. Don't make too free with your cannon. Keep cool and do mischief."

How those men shouted when the powder came! Bang! bang! the cannon in the fort thunder again. The British admiral tries to batter down the fort by firing several broadsides at the same moment. At times it seemed as if it would tumble in a heap. Once the broadsides of four vessels struck the fort at one time; but the palmetto logs stood unharmed. A gunner by the name of McDaniel was mortally wounded by a cannon ball. As the dying soldier was being carried away, he cried out to his comrades in words that will never be forgotten, "Fight on, brave boys, and don't let liberty die with this day!"

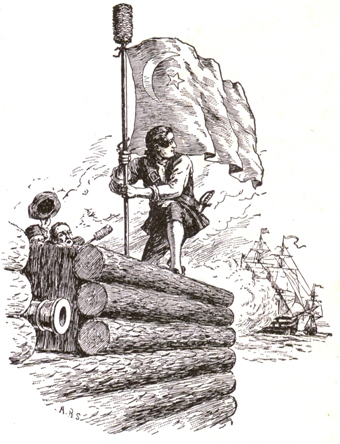

In the hottest of the fight, the flagstaff is shot away. Down falls the blue banner upon the beach, outside the fort.

"The flag is down!" "The fort has surrendered!" cry the people of Charleston, with pale faces and tearful eyes.

|

| Sergeant Jasper saves the Flag |

Out from one of the cannon openings leaps Sergeant William Jasper. Walking the whole length of the fort, he tears away the flag from the staff. Returning with it, he fastens it to the rammer of a cannon, and plants it on the ramparts, amidst the rain of shot and shell.

With the setting of the sun, the roar of battle slackens. The victory is Moultrie's. Twilight and silence fall upon the smoking fort. Here and there lights glimmer in the city, as the joyful people of Charleston return to their homes. The stars look down upon the lapping waters of the bay, where ride at anchor the shadowy vessels of the British fleet. Towards midnight, when the tide begins to ebb, the battered war ships slip their cables and sail out into the darkness with their dead.

The next day, hundreds came from the city to rejoice with Moultrie and his sturdy fighters. Governor Rutledge came down with a party of ladies, and presented a silk banner to the fort. Calling for Sergeant Jasper, he took his own short sword from his side, buckled it on him, and thanked him in the name of his country. He also offered him a lieutenant's commission, but the young hero modestly refused the honor, saying, "I am not fitted for an officer; I am only a sergeant."

For several days, the crippled British fleet lay in the harbor, too much shattered to fight or to go to sea. In fact, it was the first week in August before the patriots of South Carolina saw the last war ship and the last transport put out to sea, and fade away in the distance. The hated redcoats were gone.

In the ten hours of active fighting, the British fleet fired seventeen tons of powder and nearly ten thousand shot and shell, but, in that little inclosure of green logs and sand, only one gun was silenced.

The defense of Fort Sullivan ranks as one of the few complete American victories of the Revolution. The moral effect of the victory was perhaps more far-reaching than the battle of Bunker Hill. Many of the Southern people who had been lukewarm now openly united their fortunes with the patriot cause.

Honors were showered upon the brave Colonel Moultrie. His services to his state and to his country continued through life. He died at a good old age, beloved by his fellow citizens.

It was plain that Washington was troubled. As he paced the piazza of the stately Murray mansion one fine autumn afternoon, he was saying half aloud to himself, "Shall we defend or shall we quit New York?"

At this time Washington's headquarters were on Manhattan Island, at the home of the Quaker merchant, Robert Murray; and here, in the first week of September, 1776, he had asked his officers to meet him in council.

Was it strange that Washington's heart was heavy? During the last week of August, the Continental army had been defeated in the battle of Long Island. A fourth of the army were on the sick list; a third were without tents. Winter was close at hand, and the men, mostly new recruits, were short of clothing, shoes, and blankets. Only fourteen thousand men were fit for duty, and they were scattered all the way from the Battery to Kingsbridge, a distance of a dozen miles or more.

The British army, numbering about twenty-five thousand, lay encamped along the shores of New York Bay and the East River. The soldiers were veterans, and they were led by veterans. A large fleet of war ships, lying at anchor, was ready to assist the land forces at a moment's notice. Scores of guard ships sailed to and fro, watching every movement of the patriot troops.

To give up the city to the British without battle seemed a great pity. The effect upon the patriot cause in all the colonies would be bad. Still, there was no help for it. What was the use of fighting against such odds? Why run the risk of almost certain defeat? Washington always looked beyond the present, and he did not intend now to be shut up on Manhattan Island, perhaps to lose his entire army; so, with the main body, he moved north to Harlem Heights. Here he was soon informed by scouts that the British were getting ready to move at once. Whither, nobody could tell. Such was the state of affairs that led Washington to call his chief officers to the Murray mansion, on that September afternoon.

Of course they talked over the situation long and calmly. After all, the main question was, What shall be done? Among other things, it was thought best to find the right sort of man, and send him in disguise into the British camp on Long Island, to find out just where the enemy were planning to attack.

"Upon this, gentlemen," said Washington, "depends at this time the fate of our army."

The commander in chief sent for Colonel Knowlton, the hero of the rail fence at Bunker Hill.

"I want you to find for me in your regiment or in some other," he said, "some young officer to go at once into the British camp, to discover what is going on. The man must have a quick eye, a cool head, and nerves of steel. I wish him to make notes of the position of the enemy, draw plans of the forts, and listen to the talk of the officers. Can you find such a man for me this very afternoon?"

"I will do my best, General Washington," said the colonel, as he took leave to go to his regiment.

On arriving at his quarters that afternoon, Knowlton called together a number of officers. He briefly told them what Washington wanted, and asked for volunteers. There was a long pause, amid deep surprise. These soldiers were willing to serve their country; but to play the spy, the hated spy, was too much even for Washington to ask.

One after another of the officers, as Knowlton called them by name, declined. His task seemed hopeless. At last, he asked a grizzled Frenchman, who had fought in many battles and was noted for his rash bravery.

"No, no! Colonel Knowlton," he said, "I am ready to fight the redcoats at any place and at any time; but, sir, I am not willing to play the spy, and be hanged like a dog if I am caught."

Just as Knowlton gave up hope of finding a man willing to go on the perilous mission, there came to him the painfully thrilling but cheering words, "I will undertake it." It was the voice of Captain Nathan Hale. He had just entered Knowlton's tent. His face was still pale from a severe sickness. Every man was astonished. The whole company knew the brilliant young officer, and they loved him. Now they all tried to dissuade him. They spoke of his fair prospects, and of the fond hopes of his parents and his friends. It was all in vain. They could not turn him from his purpose.

"I wish to be useful," he said, "and every kind of service necessary for the public good becomes honorable by being necessary. If my country needs a peculiar service, its claims upon me are imperious."

These patriotic words of a man willing to give up his life, if necessary, for the good of his country silenced his brother officers.

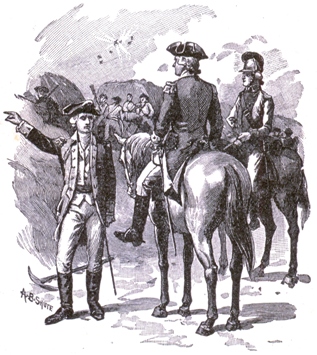

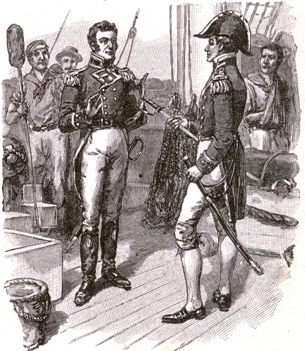

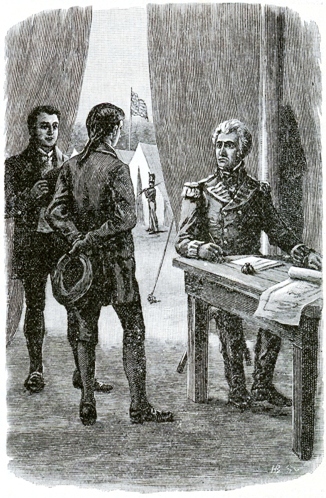

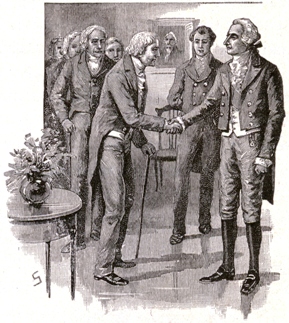

|

| Hale receiving his Orders from Washington |

"Good-by, Nathan!" "Don't you let the redcoats catch you!" "Good luck to you!" "We never expect to see you again!" cried his nearest friends in camp, as, in company with Colonel Knowlton, the young captain rode out that same afternoon to receive his orders from Washington himself.

Nathan Hale was born, as were his eight brothers and his three sisters, in an old-fashioned, two-storied house, in a little country village of Connecticut. His father, a man of integrity, was a stanch patriot. Instead of allowing his family to use the wool raised on his farm, he saved it to make blankets for the Continental army. The mother of this large family was a woman of high moral and domestic worth, devoted to her children, for whom she sought the highest good. It was a quiet, strict household, Puritan in its faith and its manners, where the Bible ruled, where family prayers never failed, nor was grace ever omitted at meals. On a Saturday night, no work was done after sundown.

Young Nathan was a bright, active American boy. He liked his gun and his fishing pole. He was fond of running, leaping, wrestling, and playing ball. One of his pupils said that Hale would put his hand upon a fence as high as his head, and clear it easily at a bound. He liked books, and read much out of school. Like two of his brothers, he was to be educated for the ministry. When only sixteen, he entered Yale College, and was graduated two years before the battle of Bunker Hill. Early in the fall of 1773, the young graduate began to teach school, and was soon afterwards made master of a select school in New London, in his native state.

At this time young Hale was about six feet tall, and well built. He had a broad chest, full face, light blue eyes, fair complexion, and light brown hair. He had a large mole on his neck, just where the knot of his cravat came. At college his friends used to joke him about it, declaring that he was surely born to be hanged.

Such was Nathan Hale when the news of the bloodshed at Lexington reached New London. A rousing meeting was held that evening. The young schoolmaster was one of the speakers.

"Let us march at once," he said, "and never lay down our arms until we obtain our independence."

The next morning, Hale called his pupils together, "gave them earnest counsel, prayed with them, and shaking each by the hand," took his leave, and during the same forenoon marched with his company for Cambridge.

The young officer from Connecticut took an active part in the siege of Boston, and soon became captain of his company. Hale's diary is still preserved, and after all these years it is full of interest. It seems that he took charge of his men's clothing, rations, and money. Much of his time he was on picket duty, and took part in many lively skirmishes with the redcoats. Besides studying military tactics, he found time to make up wrestling matches, to play football and checkers, and, on Sundays, to hold religious meetings in barns.

Within a few hours after bidding good-by to General Washington, Captain Hale, taking with him one of his own trusty soldiers, left the camp at Harlem, intending at the first opportunity to cross Long Island Sound. There were so many British guard ships on the watch that he and his companion found no safe place to cross until they had reached Norwalk, fifty miles up the Sound on the Connecticut shore. Here a small sloop was to land Hale on the other side.

Stripping off his uniform, the young captain put on a plain brown suit of citizen's clothes, and a broad-brimmed hat. Thus attired in the dress of a schoolmaster, he was landed across the Sound, and shortly afterwards reached the nearest British camp.

The redcoats received the pretended schoolmaster cordially. A captain of the dragoons spoke of him long afterwards as a "jolly good fellow." Hale pretended that he was tired of the "rebel cause," and that he was in search of a place to teach school.

It would be interesting to know just what the "schoolmaster" did in the next two weeks. Think of the poor fellow's eagerness to make the most of his time, drawing plans of the forts, and going rapidly from one point to another to watch the marching of troops, patrols, and guards. Think of his sleepless nights, his fearful risk, the ever-present dread of being recognized by some Tory. All this we know nothing about, but his brave and tender heart must sometimes have been sorely tried.

From the midst of all these dangers Hale, unharmed, began his return trip to the American lines. He had threaded his way through the woods, and round all the British camps on Long Island, until he reached in safety the point where he had first landed. Here he had planned for a boat to meet him early the next morning, to take him over to the mainland.

Many a patriotic American boy has thought what he should have done if he could have exchanged places with Nathan Hale on this evening. Near by, at a place then called and still called "The Cedars," a woman by the name of Chichester, and nicknamed "Mother Chick," kept a tavern, which was the favorite resort of all the Tories in that region. Hale was sure that nobody would know him in his strange dress, and so he ventured into the tavern. A number of people were in the barroom. A few minutes afterwards, a man whose face seemed familiar to Hale suddenly left the room, and was not seen again.

The pretended schoolmaster spent the night at the tavern.

Early the next morning, the landlady rushed into the barroom, crying out to her guests, "Look out, boys! there is a strange boat close in shore!"

The Tories scampered as if the house were on fire.

"That surely is the very boat I'm looking for," thought Hale on leaving the tavern, and hastened towards the beach, where the boat had already landed.

A moment more, and the young captain was amazed at the sight of six British marines, standing erect in the boat, with their muskets aimed at him. He turned to run, when a loud voice cried out, "Surrender or die!" He was within close range of their guns. Escape was not possible. The poor fellow gave himself up. He was taken on board the British guard ship Halifax, which lay at anchor close by, hidden from sight by a point of land.

Some have declared that the man who so suddenly left the tavern was a Tory cousin to Hale, and saw at once through the patriot's disguise; that, being quite a rascal, he hurried away to get word to the British camp. There seems to be no good reason, however, to believe that the fellow was a kinsman.

However this may be, the British captured Captain Hale in disguise. They stripped him and searched him, and found his drawings and his notes. These were written in Latin, and had been tucked away between the soles of his shoes.

"I am sorry that so fine a fellow has fallen into my hands," said the captain of the guard ship, "but you are my prisoner, and I think a spy. So to New York you must go!"

|

| The Patriot Spy before the British General |

General Howe's headquarters were at this time in the elegant Beekman mansion, situated near what is now the corner of Fifty-First Street and First Avenue. Calm and fearless, the captured spy stood before the British commander. He bravely owned that he was an American officer, and said that he was sorry he had not been able to serve his country better. No time was to be wasted in calling a court-martial. Without trial of any kind, Captain Hale was condemned to die the death of a spy. The verdict was that he should be hanged by the neck, "to-morrow morning at daybreak."

That night, which was Saturday, September 21, the condemned man was kept under a strong guard, in the greenhouse near the Beekman mansion. He had been given over to the care of the brutal Cunningham, the infamous British provost marshal, with orders to carry out the sentence before sunrise the next morning.

"To-morrow morning at daybreak."

How cruelly brief! Nathan Hale, the patriot spy, was left to himself for the night.

When morning came, Cunningham found his prisoner ready. While preparations were being made, a young officer, moved in spite of himself, allowed Hale to sit in his tent long enough to write brief letters to his parents and his friends. The letters were passed to Cunningham to be sent. He read them, and as he saw the noble spirit which breathed in every line, the wretch began to curse, and tore the letters into bits before the face of his victim. He said that the rebels should never know they had a man who could die with such firmness.

It was just before sunrise on a lovely Sabbath morning that Nathan Hale was led out to death. The gallows was the limb of an apple tree. Early as it was, a number of men and women had come to witness the execution.

|

| Statue of Nathan Hale, standing in City Hall Park in New York City |

"Give us your dying speech, you young rebel!" shouted the brutal Cunningham.

The young patriot, standing upon the fatal ladder, lifted his eyes toward heaven, and said, in a calm, clear voice, "I only regret that I have but one life to lose for my country."