The Project Gutenberg EBook of Tish, The Chronicle of Her Escapades and Excursions, by Mary Roberts Rinehart This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net Title: Tish, The Chronicle of Her Escapades and Excursions Author: Mary Roberts Rinehart Release Date: February 16, 2005 [EBook #3464] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK TISH *** Produced by Lynn Hill

LIKE A WOLF ON THE FOLD II III IV

"The outside edge, by George!" said Charlie Sands. "The old sport!"

Without cutting down her speed, bumped home the winner

The real meaning of what was occurring did not penetrate to any of us

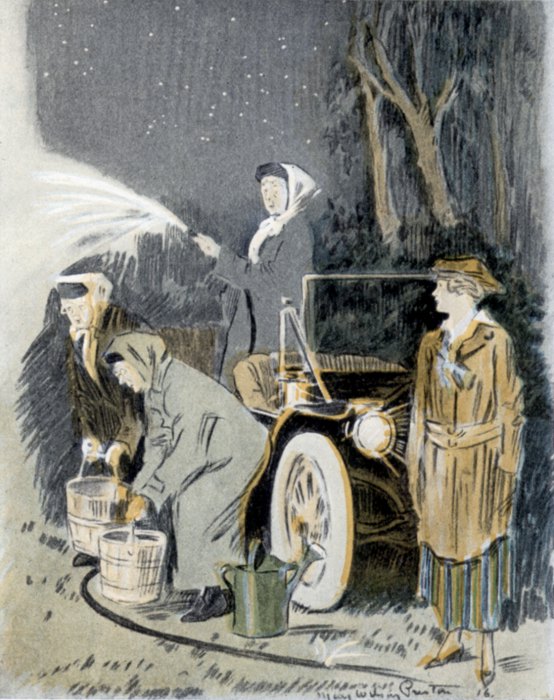

As fast as she wet a bit of lawn, we followed with the pails

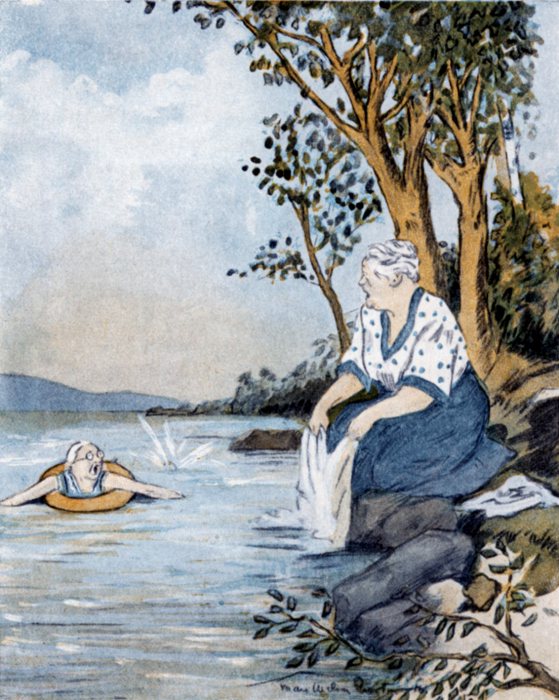

"Get the canoe and follow. I'm heading for Island Eleven"

"It's well enough for you, Tish Carberry, to talk about gripping a horse with your knees"

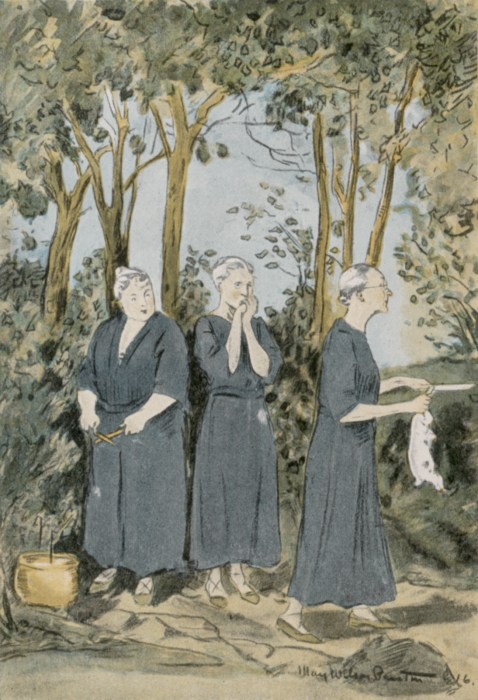

"The older I get, Aggie Pilkington, the more I realize that to take you anywhere means ruin."

"It would be just like the woman, to refuse to come any farther and spoil everything"

So many unkind things have been said of the affair at Morris Valley that I think it best to publish a straightforward account of everything. The ill nature of the cartoon, for instance, which showed Tish in a pair of khaki trousers on her back under a racing-car was quite uncalled for. Tish did not wear the khaki trousers; she merely took them along in case of emergency. Nor was it true that Tish took Aggie along as a mechanician and brutally pushed her off the car because she was not pumping enough oil. The fact was that Aggie sneezed on a curve and fell out of the car, and would no doubt have been killed had she not been thrown into a pile of sand.

It was in early September that Eliza Bailey, my cousin, decided to go to London, ostensibly for a rest, but really to get some cretonne at Liberty's. Eliza wrote me at Lake Penzance asking me to go to Morris Valley and look after Bettina.

I must confess that I was eager to do it. We three were very comfortable at Mat Cottage, "Mat" being the name Charlie Sands, Tish's nephew, had given it, being the initials of "Middle-Aged Trio." Not that I regard the late forties as middle-aged. But Tish, of course, is fifty. Charlie Sands, who is on a newspaper, calls us either the "M.A.T." or the "B.A.'s," for "Beloved Aunts," although Aggie and I are not related to him.

Bettina's mother's note:—

Not that she will allow you to do it, or because she isn't entirely able to take care of herself; but because the people here are a talky lot. Bettina will probably look after you. She has come from college with a feeling that I am old and decrepit and must be cared for. She maddens me with pillows and cups of tea and woolen shawls. She thinks Morris Valley selfish and idle, and is disappointed in the church, preferring her Presbyterianism pure. She is desirous now of learning how to cook. If you decide to come I'll be grateful if you can keep her out of the kitchen.

Devotedly, ELIZA.

P.S. If you can keep Bettina from getting married while I'm away I'll be very glad. She believes a woman should marry and rear a large family!

E.

We were sitting on the porch of the cottage at Lake Penzance when I received the letter, and I read it aloud. "Humph!" said Tish, putting down the stocking she was knitting and looking over her spectacles at me—"Likes her Presbyterianism pure and believes in a large family! How old is she? Forty?"

"Eighteen or twenty," I replied, looking at the letter. "I'm not anxious to go. She'll probably find me frivolous."

Tish put on her spectacles and took the letter. "I think it's your duty, Lizzie," she said when she'd read it through. "But that young woman needs handling. We'd better all go. We can motor over in half a day."

That was how it happened that Bettina Bailey, sitting on Eliza Bailey's front piazza, decked out in chintz cushions,—the piazza, of course,—saw a dusty machine come up the drive and stop with a flourish at the steps. And from it alight, not one chaperon, but three.

After her first gasp Bettina was game. She was a pretty girl in a white dress and bore no traces in her face of any stern religious proclivities.

"I didn't know—" she said, staring from one to the other of us. "Mother said—that is—won't you go right upstairs and have some tea and lie down?" She had hardly taken her eyes from Tish, who had lifted the engine hood and was poking at the carbureter with a hairpin.

"No, thanks," said Tish briskly. "I'll just go around to the garage and oil up while I'm dirty. I've got a short circuit somewhere. Aggie, you and Lizzie get the trunk off."

Bettina stood by while we unbuckled and lifted down our traveling trunk. She did not speak a word, beyond asking if we wouldn't wait until the gardener came. On Tish's saying she had no time to wait, because she wanted to put kerosene in the cylinders before the engine cooled, Bettina lapsed into silence and stood by watching us.

Bettina took us upstairs. She had put Drummond's "Natural Law in the Spiritual World" on my table and a couch was ready with pillows and a knitted slumber robe. Very gently she helped us out of our veils and dusters and closed the windows for fear of drafts.

"Dear mother is so reckless of drafts," she remarked. "Are you sure you won't have tea?"

"We had some blackberry cordial with us," Aggie said, "and we all had a little on the way. We had to change a tire and it made us thirsty."

"Change a tire!"

Aggie had taken off her bonnet and was pinning on the small lace cap she wears, away from home, to hide where her hair is growing thin. In her cap Aggie is a sweet-faced woman of almost fifty, rather ethereal. She pinned on her cap and pulled her crimps down over her forehead.

"Yes," she observed. "A bridge went down with us and one of the nails spoiled a new tire. I told Miss Carberry the bridge was unsafe, but she thought, by taking it very fast—"

Bettina went over to Aggie and clutched her arm. "Do you mean to say," she quavered, "that you three women went through a bridge—"

"It was a small bridge," I put in, to relieve her mind; "and only a foot or two of water below. If only the man had not been so disagreeable—"

"Oh," she said, relieved, "you had a man with you!"

"We never take a man with us," Aggie said with dignity. "This one was fishing under the bridge and he was most ungentlemanly. Quite refused to help, and tried to get the license number so he could sue us."

"Sue you!"

"He claimed his arm was broken, but I distinctly saw him move it." Aggie, having adjusted her cap, was looking at it in the mirror. "But dear Tish thinks of everything. She had taken off the license plates."

Bettina had gone really pale. She seemed at a loss, and impatient at herself for being so. "You—you won't have tea?" she asked.

"No, thank you."

"Would you—perhaps you would prefer whiskey and soda."

Aggie turned on her a reproachful eye. "My dear girl," she said, "with the exception of a little home-made wine used medicinally we drink nothing. I am the secretary of the Woman's Prohibition Party."

Bettina left us shortly after that to arrange for putting up Letitia and Aggie. She gave them her mother's room, and whatever impulse she may have had to put the Presbyterian Psalter by the bed, she restrained it. By midnight Drummond's "Natural Law" had disappeared from my table and a novel had taken its place. But Bettina had not lost her air of bewilderment.

That first evening was very quiet. A young man in white flannels called, and he and Letitia spent a delightful evening on the porch talking spark-plugs and carbureters. Bettina sat in a corner and looked at the moon. Spoken to, she replied in monosyllables in a carefully sweet tone. The young man's name was Jasper McCutcheon.

It developed that Jasper owned an old racing-car which he kept in the Bailey garage, and he and Tish went out to look it over. They very politely asked us all to go along, but Bettina refusing, Aggie and I sat with her and looked at the moon.

Aggie in her capacity as chaperon, or as one of an association of chaperons, used the opportunity to examine Bettina on the subject of Jasper.

"He seems a nice boy," she remarked. Aggie's idea of a nice boy is one who in summer wears fresh flannels outside, in winter less conspicuously. "Does he live near?"

"Next door," sweetly but coolly.

"He is very good-looking."

"Ears spoil him—too large."

"Does he come around—er—often?"

"Only two or three times a day. On Sunday, of course, we see more of him."

Aggie looked at me in the moonlight. Clearly the young man from the next door needed watching. It was well we had come.

"I suppose you like the same things?" she suggested. "Similar tastes and—er—all that?"

Bettina stretched her arms over her head and yawned.

"Not so you could notice it," she said coolly. "I can't thick of anything we agree on. He is an Episcopalian; I'm a Presbyterian. He approves of suffrage for women; I do not. He is a Republican; I'm a Progressive. He disapproves of large families; I approve of them, if people can afford them."

Aggie sat straight up. "I hope you don't discuss that!" she exclaimed.

Bettina smiled. "How nice to find that you are really just nice elderly ladies after all!" she said. "Of course we discuss it. Is it anything to be ashamed of?"

"When I was a girl," I said tartly, "we married first and discussed those things afterward."

"Of course you did, Aunt Lizzie," she said, smiling alluringly. She was the prettiest girl I think I have ever seen, and that night she was beautiful. "And you raised enormous families who religiously walked to church in their bare feet to save their shoes!"

"I did nothing of the sort," I snapped.

"It seems to me," Aggie put in gently, "that you make very little of love." Aggie was once engaged to be married to a young man named Wiggins, a roofer by trade, who was killed in the act of inspecting a tin gutter, on a rainy day. He slipped and fell over, breaking his neck as a result.

Bettina smiled at Aggie. "Not at all," she said. "The day of blind love is gone, that's all—gone like the day of the chaperon."

Neither of us cared to pursue this, and Tish at that moment appearing with Jasper, Aggie and I made a move toward bed. But Jasper not going, and none of us caring to leave him alone with Bettina, we sat down again.

We sat until one o'clock.

At the end of that time Jasper rose, and saying something about its being almost bedtime strolled off next door. Aggie was sound asleep in her chair and Tish was dozing. As for Bettina, she had said hardly a word after eleven o'clock.

Aggie and Tish, as I have said, were occupying the same room. I went to sleep the moment I got into bed, and must have slept three or four hours when I was awakened by a shot. A moment later a dozen or more shots were fired in rapid succession and I sat bolt upright in bed. Across the street some one was raising a window, and a man called "What's the matter?" twice.

There was no response and no further sound. Shaking in every limb, I found the light switch and looked at the time. It was four o'clock in the morning and quite dark.

Some one was moving in the hall outside and whimpering. I opened the door hurriedly and Aggie half fell into the room.

"Tish is murdered, Lizzie!" she said, and collapsed on the floor in a heap.

"Nonsense!"

"She's not in her room or in the house, and I heard shots!"

Well, Aggie was right. Tish was not in her room. There was a sort of horrible stillness everywhere as we stood there clutching at each other and listening.

"She's heard burglars downstairs and has gone down after them, and this is what has happened! Oh, Tish! brave Tish!" Aggie cried hysterically.

And at that Bettina came in with her hair over her shoulders and asked us if we had heard anything. When we told her about Tish, she insisted on going downstairs, and with Aggie carrying her first-aid box and I carrying the blackberry cordial, we went down.

The lower floor was quiet and empty. The man across the street had put down his window and gone back to bed, and everything was still. Bettina in her dressing-gown went out on the porch and turned on the light. Tish was not there, nor was there a body lying on the lawn.

"It was back of the house by the garage," Bettina said. "If only Jasper—"

And at that moment Jasper came into the circle of light. He had a Norfolk coat on over his pajamas and a pair of slippers, and he was running, calling over his shoulder to some one behind as he ran.

"Watch the drive!" he yelled. "I saw him duck round the corner."

We could hear other footsteps now and somebody panting near us. Aggie was sitting huddled in a porch chair, crying, and Bettina, in the hall, was trying to get down from the wall a Moorish knife that Eliza Bailey had picked up somewhere.

"John!" we heard Jasper calling. "John! Quick! I've got him!"

He was just at the corner of the porch. My heart stopped and then rushed on a thousand a minute. Then:—

"Take your hands off me!" said Tish's voice.

The next moment Tish came majestically into the circle of light and mounted the steps. Jasper, with his mouth open, stood below looking up, and a hired man in what looked like a bed quilt was behind in the shadow.

Tish was completely dressed in her motoring clothes, even to her goggles. She looked neither to the right nor left, but stalked across the porch into the house and up the stairway. None of us moved until we heard the door of her room slam above.

"Poor old dear!" said Bettina. "She's been walking in her sleep!"

"But the shots!" gasped Aggie. "Some one was shooting at her!"

Conscious now of his costume, Jasper had edged close to the veranda and stood in its shadow.

"Walking in her sleep, of course!" he said heartily. "The trip to-day was too much for her. But think of her getting into that burglar-proof garage with her eyes shut—or do sleep-walkers have their eyes shut?—and actually cranking up my racer!"

Aggie looked at me and I looked at Aggie.

"Of course," Jasper went on, "there being no muffler on it, the racket wakened her as well as the neighborhood. And then the way we chased her!"

"Poor old dear!" said Bettina again. "I'm going in to make her some tea."

"I think," said Jasper, "that I need a bit of tea too. If you will put out the porch lights I'll come up and have some."

But Aggie and I said nothing. We knew Tish never walked in her sleep. She had meant to try out Jasper's racing-car at dawn, forgetting that racers have no mufflers, and she had been, as one may say, hoist with her own petard—although I do not know what a petard is and have never been able to find out.

We drank our tea, but Tish refused to have any or to reply to our knocks, preserving a sulky silence. Also she had locked Aggie out and I was compelled to let her sleep in my room.

I was almost asleep when Aggie spoke:—

"Did you think there was anything queer about the way that Jasper boy said good-night to Bettina?" she asked drowsily.

"I didn't hear him say good-night."

"That was it. He didn't. I think"—she yawned—"I think he kissed her."

Tish was down early to breakfast that morning and her manner forbade any mention of the night before. Aggie, however, noticed that she ate her cereal with her left hand and used her right arm only when absolutely necessary. Once before Tish had almost broken an arm cranking a car and had been driven to arnica compresses for a week; but this time we dared not suggest anything.

Shortly after breakfast she came down to the porch where Aggie and I were knitting.

"I've hurt my arm, Lizzie," she said. "I wish you'd come out and crank the car."

"You'd better stay at home with an arm like that," I replied stiffly.

"Very well, I'll crank it myself."

"Where are you going?"

"To the drug store for arnica."

Bettina was not there, so I turned on Tish sharply. "I'll go, of course," I said; "but I'll not go without speaking my mind, Letitia Carberry. By and large, I've stood by you for twenty-five years, and now in the weakness of your age I'm not going to leave you. But I warn you, Tish, if you touch that racing-car again, I'll send for Charlie Sands."

"I haven't any intention of touching it again," said Tish, meekly enough. "But I wish I could buy a second-hand racer cheap."

"What for?" Aggie demanded.

Tish looked at her with scorn. "To hold flowers on the dining-table," she snapped.

It being necessary, of course, to leave a chaperon with Bettina, because of the Jasper person's habit of coming over at any hour of the day, we left Aggie with instructions to watch them both.

Tish and I drove to the drug store together, and from there to a garage for gasoline. I have never learned to say "gas" for gasoline. It seems to me as absurd as if I were to say "but" for butter. Considering that Aggie was quite sulky at being left, it is absurd for her to assume an air of virtue over what followed that day. Aggie was only like a lot of people—good because she was not tempted; for it was at the garage that we met Mr. Ellis.

We had stopped the engine and Tish was quarreling with the man about the price of gasoline when I saw him—a nice-looking young man in a black-and-white checked suit and a Panama hat. He came over and stood looking at Tish's machine.

"Nice lines to that car," he said. "Built for speed, isn't she? What do you get out of her?"

Tish heard him and turned. "Get out of her?" she said. "Bills mostly."

"Well, that's the way with most of them," he remarked, looking steadily at Tish. "A machine's a rich man's toy. The only way to own one is to have it endowed like a university. But I meant speed. What can you make?"

"Never had a chance to find out," Tish said grimly. "Between nervous women in the machine and constables outside I have the twelve-miles-an- hour habit. I'm going to exchange the speedometer for a vacuum bottle."

He smiled. "I don't think you're fair to yourself. Mostly—if you'll forgive me—I can tell a woman's driving as far off as I can see the machine; but you are a very fine driver. The way you brought that car in here impressed me considerably."

"She need not pretend she crawls along the road," I said with some sarcasm. "The bills she complains of are mostly fines for speeding."

"No!" said the young man, delighted. "Good! I'm glad to hear it. So are mine!"

After that we got along famously. He had his car there—a low gray thing that looked like an armored cruiser.

"I'd like you ladies to try her," he said. "She can move, but she is as gentle as a lamb. A lady friend of mine once threaded a needle as an experiment while going sixty-five miles an hour."

"In this car?"

"In this car."

Looking back, I do not recall just how the thing started. I believe Tish expressed a desire to see the car go, and Mr. Ellis said he couldn't let her out on the roads, but that the race-track at the fair-ground was open and if we cared to drive down there in Tish's car he would show us her paces, as he called it.

From that to going to the race-track, and from that to Tish's getting in beside him on the mechanician's seat and going round once or twice, was natural. I refused; I didn't like the look of the thing.

Tish came back with a cinder in her eye and full of enthusiasm. "It was magnificent, Lizzie," she said. "The only word for it is sublime. You see nothing. There is just the rush of the wind and the roar of the engine and a wonderful feeling of flying. Here! See if you can find this cinder."

"Won't you try it, Miss—er—Lizzie?"

"No, thanks," I replied. "I can get all the roar and rush of wind I want in front of an electric fan, and no danger."

He stood by, looking out over the oval track while I took three cinders from Tish's eye.

"Great track!" he said. "It's a horse-track, of course, but it's in bully shape—the county fair is held there and these fellows make a big feature of their horse-races. I came up here to persuade them to hold an automobile meet, but they've got cold feet an the proposition."

"What was the proposition?" asked Tish.

"Well," he said, "it was something like this. I've been turning the trick all over the country and it works like a charm. The town's ahead in money and business, for an automobile race always brings a big crowd; the track owners make the gate money and the racing-cars get the prizes. Everybody's ahead. It's a clean sport too."

"I don't approve of racing for money," Tish said decidedly.

But Mr. Ellis shrugged his shoulders. "It's really hardly racing for money," he explained. "The prizes cover the expenses of the racing-cars, which are heavy naturally. The cars alone cost a young fortune."

"I see," said Tish. "I hadn't thought of it in that light. Well, why didn't Morris Valley jump at the chance?"

He hesitated a moment before he answered. "It was my fault really," he said. "They were willing enough to have the races, but it was a matter of money. I made them a proposition to duplicate whatever prize money they offered, and in return I was to have half the gate receipts and the betting privileges."

Tish quite stiffened. "Clean sport!" she said sarcastically. "With betting privileges!"

"You don't quite understand, dear lady," he explained. "Even in the cleanest sport we cannot prevent a man's having an opinion and backing it with his own money. What I intended to do was to regulate it. Regulate it."

Tish was quite mollified. "Well, of course," she said, "I suppose since it must be, it is better—er,—regulated. But why haven't you succeeded?"

"An unfortunate thing happened just as I had the deal about to close," he replied, and drew a long breath. "The town had raised twenty-five hundred. I was to duplicate the amount. But just at that time a—a young brother of mine in the West got into difficulties, and I—but why go into family matters? It would have been easy enough for me to pay my part of the purse out of my share of the gate money; but the committee demands cash on the table. I haven't got it."

Tish stood up in her car and looked out over the track.

"Twenty-five hundred dollars is a lot of money, young man."

"Not so much when you realize that the gate money will probably amount to twelve thousand."

Tish turned and surveyed the grandstand.

"That thing doesn't seat twelve hundred."

"Two thousand people in the grandstand—that's four thousand dollars. Four thousand standing inside the ropes at a dollar each, four thousand more. And say eight hundred machines parked in the oval there at five dollars a car, four thousand more. That's twelve thousand for the gate money alone. Then there are the concessions to sell peanuts, toy balloons, lemonade and palm-leaf fans, the lunch-stands, merry-go-round and moving-picture permits. It's a bonanza! Fourteen thousand anyhow."

"Half of fourteen thousand is seven," said Tish dreamily. "Seven thousand less twenty-five hundred is thirty-five hundred dollars profit."

"Forty-five hundred, dear lady," corrected Mr. Ellis, watching her. "Forty-five hundred dollars profit to be made in two weeks, and nothing to do to get it but sit still and watch it coming!"

I can read Tish like a book and I saw what was in her mind. "Letitia Carberry!" I said sternly. "You take my warning and keep clear of this foolishness. If money comes as easy as that it ain't honest."

"Why not?" demanded Mr. Ellis. "We give them their money's worth, don't we? They'd pay two dollars for a theater seat without half the thrills—no chances of seeing a car turn turtle or break its steering-knuckle and dash into the side-lines. Two dollars' worth? It's twenty!"

But Tish had had a moment to consider, and the turning-turtle business settled it. She shook her head. "I'm not interested, Mr. Ellis," she said coldly. "I couldn't sleep at night if I thought I'd been the cause of anything turning turtle or dashing into the side-lines."

"Dear lady!" he said, shocked; "I had no idea of asking you to help me out of my difficulties. Anyhow, while matters are at a standstill probably some shrewd money-maker here will come forward before long and make a nice profit on a small investment."

As we drove away from the fair grounds Tish was very silent; but just as we reached the Bailey place, with Bettina and young Jasper McCutcheon batting a ball about on the tennis court, Tish turned to me.

"You needn't look like that, Lizzie," she said. "I'm not even thinking of backing an automobile race—although I don't see why I shouldn't, so far as that goes. But it's curious, isn't it, that I've got twenty-five hundred dollars from Cousin Angeline's estate not even earning four per cent?"

I got out grimly and jerked at my bonnet-strings.

"You put it in a mortgage, Tish," I advised her with severity in every tone. "It may not be so fast as an automobile race or so likely to turn turtle or break its steering-knuckle, but it's safe."

"Huh!" said Tish, reaching for the gear lever. "And about as exciting as a cold pork chop."

"And furthermore," I interjected, "if you go into this thing now that your eyes are open, I'll send for Charlie Sands!"

"You and Charlie Sands," said Tish viciously, jamming at her gears, "ought to go and live in an old ladies' home away from this cruel world."

Aggie was sitting under a sunshade in the broiling sun at the tennis court. She said she had not left Bettina and Jasper for a moment, and that they had evidently quarreled, although she did not know when, having listened to every word they said. For the last half-hour, she said, they had not spoken at all.

"Young people in love are very foolish," she said, rising stiffly. "They should be happy in the present. Who knows what the future may hold?"

I knew she was thinking of Mr. Wiggins and the icy roof, so I patted her shoulder and sent her up to put cold cloths on her head for fear of sunstroke. Then I sat down in the broiling sun and chaperoned Bettina until luncheon.

Jasper took dinner with us that night. He came across the lawn, freshly shaved and in clean white flannels, just as dinner was announced, and said he had seen a chocolate cake cooling on the kitchen porch and that it was a sort of unwritten social law that when the Baileys happened to have a chocolate cake at dinner they had him also.

There seemed to be nothing to object to in this. Evidently he was right, for we found his place laid at the table. The meal was quite cheerful, although Jasper ate the way some people play the piano, by touch, with his eyes on Bettina. And he gave no evidence at dessert of a fondness for chocolate cake sufficient to justify a standing invitation.

After dinner we went out on the veranda, and under cover of showing me a sunset Jasper took me round the corner of the house. Once there, he entirely forgot the sunset.

"Miss Lizzie," he began at once, "what have I done to you to have you treat me like this?"

"I?" I asked, amazed.

"All three of you. Did—did Bettina's mother warn you against me?"

"The girl has to be chaperoned."

"But not jailed, Miss Lizzie, not jailed! Do you know that I haven't had a word with Bettina alone since you came?"

"Why should you want to say anything we cannot hear?"

"Miss Lizzie," he said desperately, "do you want to hear me propose to her? For I've reached the point where if I don't propose to Bettina soon, I'll—I'll propose to somebody. You'd better be warned in time. It might be you or Miss Aggie."

I weakened at that. The Lord never saw fit to send me a man I could care enough about to marry, or one who cared enough about me, but I couldn't look at the boy's face and not be sorry for him.

"What do you want me to do?" I asked.

"Come for a walk with us," he begged. "Then sprain your ankle or get tired, I don't care which. Tell us to go on and come back for you later. Do you see? You can sit down by the road somewhere."

"I won't lie," I said firmly. "If I really get tired I'll say so. If I don't—"

"You will." He was gleeful. "We'll walk until you do! You see it's like this, Miss Lizzie. Bettina was all for me, in spite of our differing on religion and politics and—"

"I know all about your differences," I put in hastily.

"Until a new chap came to town—a fellow named Ellis. Runs a sporty car and has every girl in the town lashed to the mast. He's a novelty and I'm not. So far I have kept him away from Bettina, but at any time they may meet, and it will be one-two-three with me."

I am not defending my conduct; I am only explaining. Eliza Bailey herself would have done what I did under the circumstances. I went for a walk with Bettina and Jasper shortly after my talk with Jasper, leaving Tish with the evening paper and Aggie inhaling a cubeb cigarette, her hay fever having threatened a return. And what is more, I tired within three blocks of the house, where I saw a grassy bank beside the road.

Bettina wished to stay with me, but I said, in obedience to Jasper's eyes, that I liked to sit alone and listen to the crickets, and for them to go on. The last I saw of them Jasper had drawn Bettina's arm through his and was walking beside her with his head bent, talking. I sat for perhaps fifteen minutes and was growing uneasy about dew and my rheumatism when I heard footsteps and, looking up, I saw Aggie coming toward me. She was not surprised to see me and addressed me coldly.

"I thought as much!" she said. "I expected better of you, Lizzie. That boy asked me and I refused. I dare say he asked Tish also. For you, who pride yourself on your strength of mind—"

"I was tired," I said. "I was to sprain my ankle," she observed sarcastically. "I just thought as I was sitting there alone—"

"Where's Tish?"

"A young man named Ellis came and took her out for a ride," said Aggie. "He couldn't take us both, as the car holds only two."

I got up and stared at Aggie in the twilight. "You come straight home with me, Aggie Pilkington," I said sternly.

"But what about Bettina and Jasper?"

"Let 'em alone," I said; "they're safe enough. What we need to keep an eye on is Letitia Carberry and her Cousin Angeline's legacy."

But I was too late. Tish and Mr. Ellis whirled up to the door at half-past eight and Tish did not even notice that Bettina was absent. She took off her veil and said something about Mr. Ellis's having heard a grinding in the differential of her car that afternoon and that he suspected a chip of steel in the gears. They went out together to the garage, leaving Aggie and me staring at each other. Mr. Ellis was carrying a box of tools.

Jasper and Bettina returned shortly after, and even in the dusk I knew things had gone badly for him. He sat on the steps, looking out across the dark lawn, and spoke in monosyllables. Bettina, however, was very gay.

It was evident that Bettina had decided not to take her Presbyterianism into the Episcopal fold. And although I am a Presbyterian myself I felt sorry.

Tish and Mr. Ellis came round to the porch about ten o'clock and he was presented to Bettina. From that moment there was no question in my mind as to how affairs were going, or in Jasper's either. He refused to move and sat doggedly on the steps, but he took little part in the conversation.

Mr. Ellis was a good talker, especially about himself.

"You'll be glad to know," he said to me, "that I've got this race matter fixed up finally. In two weeks from now we'll have a little excitement here."

I looked toward Tish, but she said nothing.

"Excitement is where I live," said Mr. Ellis. "If I don't find any waiting I make it."

"If you are looking for excitement, we'll have to find you some," Jasper said pointedly.

Mr. Ellis only laughed. "Don't put yourself out, dear boy," he said. "I have enough for present necessities. If you think an automobile race is an easy thing to manage, try it. Every man who drives a racing-car has a coloratura soprano beaten to death for temperament. Then every racing-car has quirky spells; there's the local committee to propitiate; the track to look after; and if that isn't enough, there's the promotion itself, the advertising. That's my stunt—the advertising."

"It's a wonderful business, isn't it?" asked Bettina. "To take a mile or so of dirt track and turn it into a sort of stage, with drama every minute and sometimes tragedy!"

"Wait a moment," said Mr. Ellis; "I want to put that down. I'll use it somewhere in the advertising." He wrote by the light of a match, while we all sat rather stunned by both his personality and his alertness. "Everything's grist that comes to my mill. I suppose you all remember when I completed the speedway at Indianapolis and had the Governor of Indiana lay a gold brick at the entrance? Great stunt that! But the best part of that story never reached the public."

Bettina was leaning forward, all ears and thrills. "What was that?" she asked.

"I had the gold brick stolen that night—did it myself and carried the brick away in my pocket—only gold-plated, you know. Cost eight or nine dollars, all told, and brought a million dollars in advertising. But the papers were sore about some passes and wouldn't use the story. Too bad we can't use the brick here. Still have it kicking about somewhere."

It was then, I think, that Jasper yawned loudly, apologized, said good-night and lounged away across the lawn. Bettina hardly knew he was going. She was bending forward, her chin in her palms, listening to Mr. Ellis tell about a driver in a motor race breaking his wrist cranking a car, and how he—Ellis—had jumped into the car and driven it to victory. Even Aggie was enthralled. It seemed as if, in the last hour, the great world of stress and keen wits and endeavor and mad speed had sat down on our door-step.

As Tish said when we were going up to bed, why shouldn't Mr. Ellis brag? He had something to brag about.

Although I felt quite sure that Tish had put up the prize money for Mr. Ellis, I could not be certain. And Tish's attitude at that time did not invite inquiry. She took long rides daily with the Ellis man in his gray car, and I have reason to believe that their objective point was always the same—the race-track.

Mr. Ellis was the busiest man in Morris Valley. In the daytime he was superintending putting the track in condition, writing what he called "promotion stuff," securing entries and forming the center of excited groups at the drug store and one or other of the two public garages. In the evenings he was generally to be found at Bettina's feet.

Jasper did not come over any more. He sauntered past, evening after evening, very much white-flanneled and carrying a tennis racket. And once or twice he took out his old racing-car, and later shot by the house with a flutter of veils and a motor coat beside him.

Aggie was exceedingly sorry for him, and even went the length of having the cook bake a chocolate cake and put it on the window sill to cool. It had, however, no perceptible effect, except to draw from Mr. Ellis, who had been round at the garage looking at Jasper's old racer, a remark that he was exceedingly fond of cake, and if he were urged—

That was, I believe, a week before the race. The big city papers had taken it up, according to Mr. Ellis, and entries were pouring in.

"That's the trouble on a small track," he said—"we can't crowd 'em. A dozen cars will be about the limit. Even with using the cattle pens for repair pits we can't look after more than a dozen. Did I tell you Heckert had entered his Bonor?"

"No!" we exclaimed. As far as Aggie and I were concerned, the Bonor might have been a new sort of dog.

"Yes, and Johnson his Sampler. It's going to be some race—eh, what!"

Jasper sauntered over that evening, possibly a late result of the cake, after all. He greeted us affably, as if his defection of the past week had been merely incidental, and sat down on the steps.

"I've been thinking, Ellis," he said, "that I'd like to enter my car."

"What!" said Ellis. "Not that—"

"My racer. I'm not much for speed, but there's a sort of feeling in the town that the locality ought to be represented. As I'm the only owner of a speed car—"

"Speed car!" said Ellis, and chuckled. "My dear boy, we've got Heckert with his ninety-horse-power Bonor!"

"Never heard of him." Jasper lighted a cigarette. "Anyhow, what's that to me? I don't like to race. I've got less speed mania than any owner of a race car you ever met. But the honor of the town seems to demand a sacrifice, and I'm it."

"You can try out for it anyhow," said Ellis. "I don't think you'll make it; but, if you qualify, all right. But don't let any other town people, from a sense of mistaken local pride, enter a street roller or a traction engine."

Jasper colored, but kept his temper.

Aggie, however, spoke up indignantly. "Mr. McCutcheon's car was a very fine racer when it was built."

"De mortuis nil nisi bonum," remarked Mr. Ellis, and getting up said good-night.

Jasper sat on the steps and watched him disappear. Then he turned to Tish.

"Miss Letitia," he said, "do you think you are wise to drive that racer of his the way you have been doing?"

Aggie gave a little gasp and promptly sneezed, as she does when she is excited.

"I?" said Tish.

"You!" he smiled. "Not that I don't admire your courage. I do. But the other day, now, when you lost a tire and went into the ditch—"

"Tish!" from Aggie.

"—you were fortunate. But when a racer turns over the results are not pleasant."

"As a matter of fact," said Tish coldly, "it was a wheat-field, not a ditch."

Jasper got up and threw away his cigarette. "Well, our departing friend is not the only one who can quote Latin," he said. "Verbum sap., Miss Tish. Good-night, everybody. Good-night, Bettina."

Bettina's good-night was very cool. As I went up to bed that night, I thought Jasper's chances poor indeed. As for Tish, I endeavored to speak a few word of remonstrance to her, but she opened her Bible and began to read the lesson for the day and I was obliged to beat a retreat.

It was that night that Aggie and I, having decided the situation was beyond us, wrote a letter to Charlie Sands asking him to come up. Just as I was sealing it Bettina knocked and came in. She closed the door behind her and stood looking at us both.

"Where is Miss Tish?" she asked.

"Reading her Bible," I said tartly. "When Tish is up to some mischief, she generally reads an extra chapter or two as atonement."

"Is she—is she always like this?"

"The trouble is," explained Aggie gently, "Miss Letitia is an enthusiast. Whatever she does, she does with all her heart."

"I feel so responsible," said Bettina. "I try to look after her, but what can I do?"

"There is only one thing to do," I assured her—"let her alone. If she wants to fly, let her fly; if she wants to race, let her race—and trust in Providence."

"I'm afraid Providence has its hands full!" said Bettina, and went to bed.

For the remainder of that week nothing was talked of in Morris Valley but the approaching race. Some of Eliza Bailey's friends gave fancy-work parties for us, which Aggie and I attended. Tish refused, being now openly at the race-track most of the day. Morris Valley was much excited. Should it wear motor clothes, or should it follow the example of the English Derby and the French races and wear its afternoon reception dress with white kid gloves? Or—it being warm—wouldn't lingerie clothes and sunshades be most suitable?

Some of the gossip I retailed to Jasper, oil-streaked and greasy, in the Baileys' garage where he was working over his car.

"Tell 'em to wear mourning," he said pessimistically. "There's always a fatality or two. If there wasn't a fair chance of it nothing would make 'em sit for hours watching dusty streaks going by."

The race was scheduled for Wednesday. On Sunday night the cars began to come in. On Monday Tish took us all, including Bettina, to the track. There were half a dozen tents in the oval, one of them marked with a huge red cross.

"Hospital tent," said Tish calmly. We even, on permission from Mr. Ellis, went round the track. At one spot Tish stopped the car and got out.

"Nail," she said briefly. "It's been a horse-racing track for years, and we've gathered a bushel of horse-shoe nails."

Aggie and I said nothing, but we looked at each other. Tish had said "we." Evidently Cousin Angeline's legacy was not going into a mortgage.

The fair-grounds were almost ready. Peanut and lunch stands had sprung up everywhere. The oval, save by the tents and the repair pits, was marked off into parking-spaces numbered on tall banners. Groups of dirty men in overalls, carrying machine wrenches, small boys with buckets of water, onlookers round the tents and track-rollers made the place look busy and interesting. Some of the excitement, I confess, got into my blood. Tish, on the contrary, was calm and businesslike. We were sorry we had sent for Charlie Sands. She no longer went out in Mr. Ellis's car, and that evening she went back to the kitchen and made a boiled salad dressing.

We were all deceived.

Charlie Sands came the next morning. He was on the veranda reading a paper when we got down to breakfast. Tish's face was a study.

"Who sent for you?" she demanded.

"Sent for me! Why, who would send for me? I'm here to write up the race. I thought, if you haven't been out to the track, we'd go out this morning."

"We've been out," said Tish shortly, and we went in to breakfast. Once or twice during the meal I caught her eye on me and on Aggie and she was short with us both. While she was upstairs I had a word with Charlie Sands.

"Well," he said, "what is it this time? Is she racing?"

"Worse than that," I replied. "I think she's backing the thing!"

"No!"

"With her cousin Angeline's legacy." With that I told him about our meeting Mr. Ellis and the whole story. He listened without a word.

"So that's the situation," I finished. "He has her hypnotized, Charlie. What's more, I shouldn't be surprised to see her enter the race under an assumed name."

Charlie Sands looked at the racing list in the Morris Valley Sun.

"Good cars all of them," he said. "She's not here among the drivers, unless she's—Who are these drivers anyhow? I never heard of any of them."

"It's a small race," I suggested. "I dare say the big men—"

"Perhaps." He put away his paper and got up. "I'll just wander round the town for an hour or two, Aunt Lizzie," he said. "I believe there's a nigger in this woodpile and I'm a right nifty little nigger-chaser."

When he came back about noon, however, he looked puzzled. I drew him aside.

"It seems on the level," he said. "It's so darned open it makes me suspicious. But she's back of it all right. I got her bank on the long-distance 'phone."

We spent that afternoon at the track, with the different cars doing what I think they called "trying out heats." It appeared that a car, to qualify, must do a certain distance in a certain time. It grew monotonous after a while. All but one entry qualified and Jasper just made it. The best showing was made by the Bonor car, according to Charlie Sands.

Jasper came to our machine when it was over, smiling without any particular good cheer.

"I've made it and that's all," he said. "I've got about as much chance as a watermelon at a colored picnic. I'm being slaughtered to make a Roman holiday."

"If you feel that way why do you do it?" demanded Bettina coldly. "If you go in expecting to slaughtered—"

He was leaning on the side of the car and looked up at her with eyes that made my heart ache, they were so wretched.

"What does it matter?" he said. "I'll probably trail in at the last, sound in wind and limb. If I don't, what does it matter?"

He turned and left us at that, and I looked at Bettina. She had her lips shut tight and was blinking hard. I wished that Jasper had looked back.

Charlie Sands announced at dinner that he intended to spend the night at the track.

Tish put down her fork and looked at him. "Why?" she demanded.

"I'm going to help the boy next door watch his car," he said calmly. "Nothing against your friend Mr. Ellis, Aunt Tish, but some enemy of true sport might take a notion in the night to slip a dope pill into the mouth of friend Jasper's car and have her go to sleep on the track to-morrow."

We spent a quiet evening. Mr. Ellis was busy, of course, and so was Jasper. The boy came to the house to get Charlie Sands and, I suppose, for a word with Bettina, for when he saw us all on the porch he looked, as you may say, thwarted.

When Charlie Sands had gone up for his pajamas and dressing-gown, Jasper stood looking up at us.

"Oh, Association of Chaperons!" he said, "is it permitted that my lady walk to the gate with me—alone?"

"I am not your lady," flashed Bettina.

"You've nothing to say about that," he said recklessly. "I've selected you; you can't help it. I haven't claimed that you have selected me."

"Anyhow, I don't wish to go to the gate," said Bettina.

He went rather white at that, and Charlie Sands coming down at that moment with a pair of red-and-white pajamas under his arm and a toothbrush sticking out of his breast pocket, romance, as Jasper said later in referring to it, "was buried in Sands."

Jasper went up to Bettina and held out his hand. "You'll wish me luck, won't you?"

"Of course." She took his hand. "But I think you're a bit of a coward, Jasper!"

He eyed her. "Coward!" he said. "I'm the bravest man you know. I'm doing a thing I'm scared to death to do!"

The race was to begin at two o'clock in the afternoon. There were small races to be run first, but the real event was due at three.

From early in the morning a procession of cars from out of town poured in past Eliza Bailey's front porch, and by noon her cretonne cushions were thick with dust. And not only automobiles came, but hay-wagons, side-bar buggies, delivery carts—anything and everything that could transport the crowd.

At noon Mr. Ellis telephoned Tish that the grand-stand was sold out and that almost all the parking-places that had been reserved were taken. Charlie Sands came home to luncheon with a curious smile on his face.

"How are you betting, Aunt Tish?" he asked.

"Betting!"

"Yes. Has Ellis let you in on the betting?"

"I don't know what you are talking about," Tish said sourly. "Mr. Ellis controls the betting so that it may be done in an orderly manner. I am sure I have nothing to do with it."

"I'd like to bet a little, Charlie," Aggie put in with an eye on Tish. "I'd put all I win on the collection plate on Sunday."

"Very well." Charlie Sands took out his notebook. "On what car and how much?"

"Ten dollars on the Fein. It made the best time at the trial heats."

"I wouldn't if I were you," said Charlie Sands. "Suppose we put it on our young friend next door."

Bettina rather sniffed. "On Jasper!" she exclaimed.

"On Jasper," said Charlie Sands gravely.

Tish, who had hardly heard us, looked up from her plate.

"Bettina is betting," she snapped. "Putting it on the collection plate doesn't help any." But with that she caught Charlie Sands' eye and he winked at her. Tish colored. "Gambling is one thing, clean sport is another," she said hotly.

I believe, however, that whatever Charlie Sands may have suspected, he really knew nothing until the race had started. By that time it was too late to prevent it, and the only way he could think of to avoid getting Tish involved in a scandal was to let it go on.

We went to the track in Tish's car and parked in the oval. Not near the grandstand, however. Tish had picked out for herself a curve at one end of the track which Mr. Ellis had said was the worst bit on the course. "He says," said Tish, as we put the top down and got out the vacuum bottle—oh, yes, Mr. Ellis had sent Tish one as a present—"that if there are any smashups they'll occur here."

Aggie is not a bloodthirsty woman ordinarily, but her face quite lit up.

"Not really!" she said.

"They'll probably turn turtle," said Tish. "There is never a race without a fatality or two. No racer can get any life insurance. Mr. Ellis says four men were killed at the last race he promoted."

"Then I think Mr. Ellis is a murderer," Bettina cried. We all looked at her. She was limp and white and was leaning back among the cushions with her eyes shut. "Why didn't you tell Jasper about this curve?" she demanded of Tish.

But at that moment a pistol shot rang out and the races were on.

The Fein won two of the three small races. Jasper was entered only for the big race. In the interval before the race was on, Jasper went round the track slowly, looking for Bettina. When he saw us he waved, but did not stop. He was number thirteen.

I shall not describe the race. After the first round or two, what with dust in my eyes and my neck aching from turning my head so rapidly, I just sat back and let them spin in front of me.

It was after a dozen laps or so, with number thirteen doing as well as any of them, that Tish was arrested.

Charlie Sands came up beside the car with a gentleman named Atkins, who turned out to be a county detective. Charlie Sands was looking stern and severe, but the detective was rather apologetic.

"This is Miss Carberry," said Charlie Sands. "Aunt Tish, this gentleman wishes to speak to you."

"Come around after the race," Tish observed calmly.

"Miss Carberry," said the detective gently, "I believe you are back of this race, aren't you?"

"What if I am?" demanded Tish.

Charlie Sands put a hand on the detective's arm. "It's like this, Aunt Tish," he said; "you are accused of practicing a short-change game, that's all. This race is sewed up. You employ those racing-cars with drivers at an average of fifty dollars a week. They are hardly worth it, Aunt Tish. I could have got you a better string for twenty-five."

Tish opened her mouth and shut it again without speaking.

"You also control the betting privileges. As you own all the racers you have probably known for a couple of weeks who will win the race. Having made the Fein favorite, you can bet on a Brand or a Bonor, or whatever one you chance to like, and win out. Only I take it rather hard of you, Aunt Tish, not to have let the family in. I'm hard up as the dickens."

"Charlie Sands!" said Tish impressively. "If you are joking—"

"Joking! Did you ever know a county detective to arrest a prominent woman at a race-track as a little jest between friends? There's no joke, Aunt Tish. You've financed a phony race. The permit is taken in your name—L.L. Carberry. Whatever car wins, you and Ellis take the prize money, half the gate receipts, and what you have made out of the betting—"

Tish rose in the machine and held out both her hands to Mr. Atkins.

"Officer, perform your duty," she said solemnly. "Ignorance is no defense and I know it. Where are the handcuffs?"

"We'll not bother about them, Miss Carberry", he said. "If you like I'll get into the car and you can tell me all about it while we watch the race. Which car is to win?"

"I may have been a fool, Mr. County Detective," she said coldly; "but I'm not a knave. I have not bet a dollar on the race."

We were very silent for a time. The detective seemed to enjoy the race very much and ate peanuts out of his pocket. He even bought a red-and-black pennant, with "Morris Valley Races" on it, and fastened it to the car. Charlie Sands, however, sat with his arms folded, stiff and severe.

Once Tish bent forward and touched his arm.

"You—you don't think it will get in the papers, do you?" she quavered.

Charlie Sands looked at her with gloom. "I shall have to send it myself, Aunt Tish," he said; "it is my duty to my paper. Even my family pride, hurt to the quick and quivering as it is, must not interfere with my duty."

It was Bettina who suggested a way out—Bettina, who had sat back as pale as Tish and heard that her Mr. Ellis was, as Charlie Sands said later, as crooked as a pretzel.

"But Jasper was not—not subsidized," she said. "If he wins, it's all right, isn't it?"

The county detective turned to her.

"Jasper?" he said.

"A young man who lives here." Bettina colored.

"He is—not to be suspected?"

"Certainly not," said Bettina haughtily; "he is above suspicion. Besides, he—he and Mr. Ellis are not friends."

Well, the county detective was no fool. He saw the situation that minute, and smiled when he offered Bettina a peanut. "Of course," he said cheerfully, "if the race is won by a Morris Valley man, and not by one of the Ellis cars, I don't suppose the district attorney would care to do anything about it. In fact," he said, smiling at Bettina, "I don't know that I'd put it up to the district attorney at all. A warning to Ellis would get him out of the State."

It was just at that moment that car number thirteen, coming round the curve, skidded into the field, threw out both Jasper McCutcheon and his mechanician, and after standing on two wheels for an appreciable moment of time, righted herself, panting, with her nose against a post.

Jasper sat up almost immediately and caught at his shoulder. The mechanician was stunned. He got up, took a step or two and fell down, weak with fright.

I do not recall very distinctly what happened next. We got out of the machine, I remember, and Bettina was cutting off Jasper's sweater with Charlie Sands' penknife, and crying as she did it. And Charlie Sands was trying to prevent Jasper from getting back into his car, while Jasper was protesting that he could win in two or more laps and that he could drive with one hand—he'd only broken his arm.

The crowd had gathered round us, thick. Suddenly they drew back, and in a sort of haze I saw Tish in Jasper's car, with Aggie, as white as death, holding to Tish's sleeve and begging her not to get in. The next moment Tish let in the clutch of the racer and Aggie took a sort of flying leap and landed beside her in the mechanician's seat.

Charlie Sands saw it when I did, but we were both too late. Tish was crossing the ditch into the track again, and the moment she struck level ground she put up the gasoline.

It was just then that Aggie fell out, landing, as I have said before, in a pile of sand. Tish said afterward that she never missed her. She had just discovered that this was not Jasper's old car, which she knew something about, but a new racer with the old hood and seat put on in order to fool Mr. Ellis. She didn't know a thing about it.

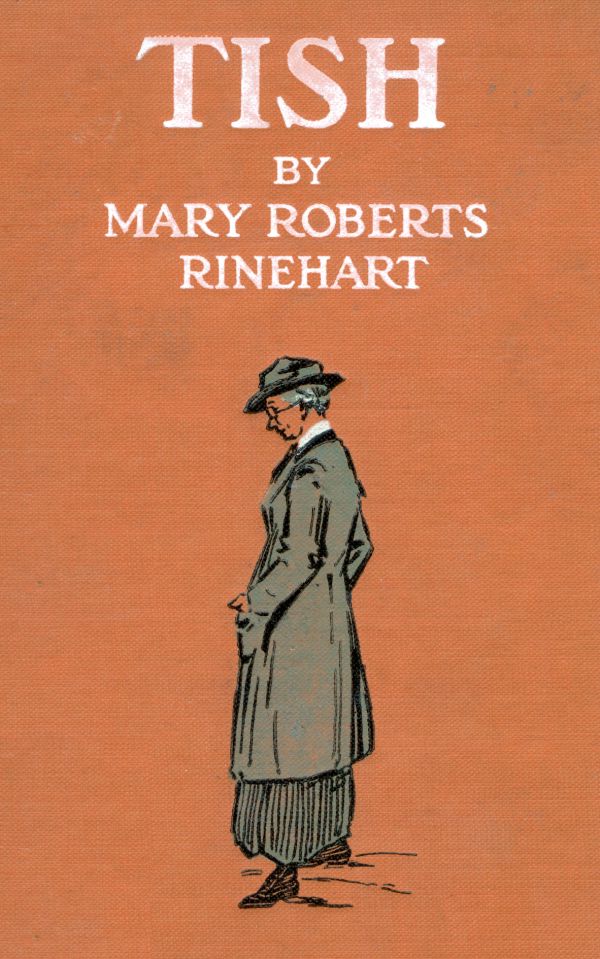

Well, you know the rest—how Tish, trying to find how the gears worked, side-swiped the Bonor car and threw it off the field and out of the race; how, with the grandstand going crazy, she skidded off the track into the field, turned completely round twice, and found herself on the track again facing the way she wanted to go; how, at the last lap, she threw a tire and, without cutting down her speed, bumped home the winner, with the end of her tongue nearly bitten off and her spine fairly driven up into her skull.

All this is well known now, as is also the fact that Mr. Ellis disappeared from the judges' stand after a word or two with Mr. Atkins, and was never seen at Morris Valley again.

Tish came out of the race ahead by half the gate money—six thousand dollars—by a thousand dollars from concessions, and a lame back that she kept all winter. Even deducting the twenty-five hundred she had put up, she was forty-five hundred dollars ahead, not counting the prize money. Charlie Sand brought the money from the track that night, after having paid off Mr. Ellis's racing-string and given Mr. Atkins a small present. He took over the prize money to Jasper and came back with it, Jasper maintaining that it belonged to Tish, and that he had only raced for the honor of Morris Valley. For some time the money went begging, but it settled itself naturally enough, Tish giving it to Jasper in the event of—but that came later.

On the following evening—Bettina, in the pursuit of learning to cook, having baked a chocolate cake—we saw Jasper, with his arm in a sling, crossing the side lawn.

Jasper stopped at the foot of the steps. "I see a chocolate cake cooling on the kitchen porch," he said. "Did you order it, Miss Lizzie?"

I shook my head.

"Miss Tish? Miss Aggie?"

"I ordered it," said Bettina defiantly—"or rather I baked it."

"And you did that, knowing what it entailed? He was coming up the steps slowly and with care.

"What does it entail?" demanded Bettina.

"Me."

"Oh, that!" said Bettina. "I knew that."

Jasper threw his head back and laughed. Then:—

"Will the Associated Chaperons," he said, "turn their backs?"

"Not at all," I began stiffly. "If I—"

"She baked it herself!" said Jasper exultantly. "One—two. When I say three I shall kiss Bettina."

And I have every reason to believe he carried out his threat.

Eliza Bailey forwarded me this letter from London where Bettina had sent it to her:—

Dearest Mother: I hope you are coming home soon. I really think you should. Aunt Lizzie is here and she brought two friends, and, mother, I feel so responsible for them! Aunt Lizzie is sane enough, if somewhat cranky; but Miss Tish is almost more than I can manage—I never know what she is going to do next—and I am worn out with chaperoning her. And Miss Aggie, although she is very sweet, is always smoking cubeb cigarettes for hay fever, and it looks terrible! The neighbors do not know they are cubeb, and, anyhow, that's a habit, mother. And yesterday Miss Tish was arrested, and ran a motor race and won it, and to-day she is knitting a stocking and reciting the Twenty-third Psalm. Please, mother, I think you should come home.

Lovingly, BETTINA.

P.S. I think I shall marry Jasper after all. He says he likes the Presbyterian service.

I looked up from reading Eliza's letter. Tish was knitting quietly and planning to give the money back to the town in the shape of a library, and Aggie was holding a cubeb cigarette to her nose. Down on the tennis court Jasper and Bettina were idly batting a ball round.

"I'm glad the Ellis man did not get her," said Aggie. And then, after a sneeze, "How Jasper reminds me of Mr. Wiggins."

The library did not get the money after all. Tish sent it, as a wedding present, to Bettina.

Aggie has always been in the habit of observing the anniversary of Mr. Wiggins's death. Aggie has the anniversary habit, anyhow, and her life is a succession: of small feast-days, on which she wears mental crape or wedding garments—depending on the occasion. Tish and I always remember these occasions appropriately, sending flowers on the anniversaries of the passing away of Aggie's parents; grandparents; a niece who died in birth; her cousin, Sarah Webb, who married a missionary and was swallowed whole by a large snake,—except her shoes, which the reptile refused and of which Aggie possesses the right, given her by the stricken husband; and, of course, Mr. Wiggins.

For Mr. Wiggins Tish and I generally send the same things each year—Tish a wreath of autumn foliage and I a sheaf of wheat tied with a lavender ribbon. The program seldom varies. We drive to the cemetery in the afternoon and Aggie places the sheaf and the wreath on Mr. Wiggins's last resting-place, after first removing the lavender ribbon, of which she makes cap bows through the year and an occasional pin-cushion or fancy-work bag; then home to chicken and waffles, which had been Mr. Wiggins's favorite meal. In the evening Charlie Sands generally comes in and we play a rubber or two of bridge.

On the thirtieth anniversary of Mr. Wiggins's falling off a roof and breaking his neck, Tish was late in arriving, and I found Aggie sitting alone, dressed in black, with a tissue-paper bundle in her lap. I put my sheaf on the table and untied my bonnet-strings.

"Where's Tish?" I asked.

"Not here yet."

Something in Aggie's tone made me look at her. She was eyeing the bundle in her lap.

"I got a paler shade of ribbon this time," I said, seeing she made no comment on the sheaf. "It's a better color for me if you're going to make my Christmas present out of it this year again. Where's Tish's wreath?"

"Here." Aggie pointed dispiritedly to the bundle in her lap and went on rocking.

"That! That's no wreath."

In reply Aggie lifted the tissue paper and shook out, with hands that trembled with indignation, a lace-and-linen centerpiece. She held it up before me and we eyed each other over it. Both of us understood.

"Tish is changed, Lizzie," Aggie said hollowly. "Ask her for bread these days and she gives you a Cluny-lace fandangle. On mother's anniversary she sent me a set of doilies; and when Charlie Sands was in the hospital with appendicitis she took him a pair of pillow shams. It's that Syrian!"

Both of us knew. We had seen Tish's apartment change from a sedate and spinsterly retreat to a riot of lace covers on the mantel, on the backs of chairs, on the stands, on the pillows—everywhere. We had watched her Marseilles bedspreads give way to hem-stitched covers, with bolsters to match. We had seen Tish go through a cold winter clad in a succession of sleazy silk kimonos instead of her flannel dressing-gown; terrible kimonos—green and yellow and red and pink, that looked like fruit salads and were just as heating.

"It's that dratted Syrian!" cried Aggie—and at that Tish came in. She stood inside the door and eyed us.

"What about him?" she demanded. "If I choose to take a poor starving Christian youth and assist him by buying from him what I need—what I need!—that's my affair, isn't it? Tufik was starving and I took him in."

"He took you in, all right!" Aggie sniffed. "A great, mustached, dirty, palavering foreigner, who's probably got a harem at home and no respect for women!"

Tish glanced at my sheaf and at the centerpiece. She was dressed as she always dressed on Mr. Wiggins's day—in black; but she had a new lace collar with a jabot, and we knew where she had got it. She saw our eyes on it and she had the grace to flush.

"Once for all," she snapped, "I intend to look after this unfortunate Syrian! If my friends object, I shall be deeply sorry; but, so far as I care, they may object until they are purple in the face and their tongues hang out. I've been sending my money to foreign missions long enough; I'm doing my missionary work at home now."

"He'll marry you!" This from Aggie.

Tish ignored her. "His father is an honored citizen of Beirut, of the nobility. The family is impoverished, being Christian, and grossly imposed on by the Turks. Tufik speaks French and English as well as Mohammedan. They offered him a high government position if he would desert the Christian faith; but he refused firmly. He came to this country for religious freedom; at any moment they may come after him and take him back."

A glint of hope came to me. I made a mental note to write to the mayor, or whatever they call him over there, and tell him where he could locate his wandering boy.

"He loves the God of America," said Tish.

"Money!" Aggie jeered.

"And he is so pathetic, so grateful! I told Hannah at noon to-day—that's what delayed me—to give him his lunch. He was starving; I thought we'd never fill him. And when it was over, he stooped in the sweetest way, while she was gathering up the empty dishes, and kissed her hand. It was touching!"

"Very!" I said dryly. "What did Hannah do?"

"She's a fool! She broke a cup on his head."

Mr. Wiggins's anniversary was not a success. Part of this was due to Tish, who talked of Tufik steadily—of his youth; of the wonderful bargains she secured from him; of his belief that this was the land of opportunity—Aggie sniffed; of his familiarity with the Bible and Biblical places; of the search the Turks were making for him. The atmosphere was not cleared by Aggie's taking the Cluny-lace centerpiece to the cemetery and placing it, with my sheaf, on Mr. Wiggins's grave.

As we got into Tish's machine to go back, Aggie was undeniably peevish. She caught cold, too, and was sneezing—as she always does when she is irritated or excited.

"Where to?" asked Tish from the driving-seat, looking straight ahead and pulling on her gloves. From where we sat we could still see the dot of white on the grass that was the centerpiece.

"Back to the house," Aggie snapped, "to have some chicken and waffles and Tufik for dinner!"

Tish drove home in cold silence. As well as we could tell from her back, she was not so much indignant as she was determined. Thus we do not believe that she willfully drove over every rut and thank-you-ma'am on the road, scattering us generously over the tonneau, and finally, when Aggie, who was the lighter, was tossed against the top and sprained her neck, eliciting a protest from us. She replied in an abstracted tone, which showed where her mind was.

"It would be rougher on a camel," she said absently. "Tufik was telling me the other day—"

Aggie had got her head straight by that time and was holding it with both hands to avoid jarring. She looked goaded and desperate; and, as she said afterward, the thing slipped out before she knew she was more than thinking it.

"Oh, damn Tufik!" she said.

Fortunately at that moment we blew out a tire and apparently Tish did not hear her. While I was jacking up the car and Tish was getting the key of the toolbox out of her stocking, Aggie sat sullenly in her place and watched us.

"I suppose," she gibed, "a camel never blows out a tire!"

"It might," Tish said grimly, "if it heard an oath from the lips of a middle-aged Sunday-school teacher!"

We ate Mr. Wiggins's anniversary dinner without any great hilarity. Aggie's neck was very stiff and she had turned in the collar of her dress and wrapped flannels wrung out of lamp oil round it. When she wished to address either Tish or myself she held her head rigid and turned her whole body in her chair; and when she felt a sneeze coming on she clutched wildly at her head with both hands as if she expected it to fly off.

Tufik was not mentioned, though twice Tish got as far as Tu— and then thought better of it; but her mind was on him and we knew it. She worked the conversation round to Bible history and triumphantly demanded whether we knew that Sodom and Gomorrah are towns to-day, and that a street-car line is contemplated to them from some place or other—it developed later that she meant Tyre and Sidon. Once she suggested that Aggie's sideboard needed new linens, but after a look at Aggie's rigid head she let it go at that.

No one was sorry when, with dinner almost over, and Aggie lifting her ice-cream spoon straight up in front of her and opening her mouth with a sort of lockjaw movement, the bell rang. We thought it was Charlie Sands. It was not. Aggie faced the doorway and I saw her eyes widen. Tish and I turned.

A boy stood in the doorway—a shrinking, timid, brown-eyed young Oriental, very dark of skin, very white of teeth, very black of hair—a slim youth of eighteen, possibly twenty, in a shabby blue suit, broken shoes, and a celluloid collar. Twisting between nervous brown fingers, not as clean as they might have been, was a tissue-paper package.

"My friends!" he said, and smiled.

Tish is an extraordinary woman. She did not say a word. She sat still and let the smile get in its work. Its first effect was on Aggie's neck, which she forgot. Tufik's timid eyes rested for a moment on Tish and brightened. Then like a benediction they turned to mine, and came to a stop on Aggie. He took a step farther into the room.

"My friend's friend are my friend," he said. "America is my friend—this so great God's country!"

Aggie put down her ice-cream spoon and closed her mouth, which had been open.

"Come in, Tufik," said Tish; "and I am sure Miss Pilkington would like you to sit down."

Tufik still stood with his eyes fixed on Aggie, twisting his package.

"My friend has said," he observed—he was quite calm and divinely trustful—"My friend has said that this is for Miss Pilk a sad day. My friend is my mother; I have but her and God. Unless—but perhaps I have two new friend also—no?"

"Of course we are your friends," said Aggie, feeling for the table-bell with her foot. "We are—aren't we, Lizzie?"

Tufik turned and looked at me wistfully. It came over me then what an awful thing it must be to be so far from home and knowing nobody, and having to wear trousers and celluloid collars instead of robes and turbans, and eat potatoes and fried things instead of olives and figs and dates, and to be in danger of being taken back and made into a Mohammedan and having to keep a harem.

"Certainly," I assented. "If you are good we will be your friends."

He flashed a boyish smile at me.

"I am good," he said calmly—"as the angels I am good. I have here a letter from a priest. I give it to you. Read!"

He got a very dirty envelope from his pocket and brought it round the table to me. "See!" he said. "The priest says: 'Of all my children Tufik lies next my heart.'"

He held the letter out to me; but it looked as if it had been copied from an Egyptian monument and was about as legible as an outbreak of measles.

"This," he said gently, pointing, "is the priest's blessing. I carry it ever. It brings me friends." He put the paper away and drew a long breath; then surveyed us all with shining eyes. "It has brought me you."

We were rather overwhelmed. Aggie's maid having responded to the bell, Aggie ordered ice cream for Tufik and a chair drawn to the table; but the chair Tufik refused with a little, smiling bow.

"It is not right that I sit," he said. "I stand in the presence of my three mothers. But first—I forget—my gift! For the sadness, Miss Pilk!"

He held out the tissue-paper package and Aggie opened it. Tufik's gift proved to be a small linen doily, with a Cluny-lace border!

We were gone from that moment—I know it now, looking back. Gone! We were lost the moment Tufik stood in the doorway, smiling and bowing. Tish saw us going; and with the calmness of the lost sat there nibbling cake and watching us through her spectacles—and raised not a hand.

Aggie looked at the doily and Tufik looked at her.

"That's—that's really very nice of you," said Aggie. "I thank you."

Tufik came over and stood beside her.

"I give with my heart," he said shyly. "I have had nobody—in all so large this country—nobody! And now—I have you!" Aggie saw—but too late. He bent over and touched his lips to her hands. "The Bible says: 'To him that overcometh I will give the morning star!' I have overcometh—ah, so much!—the sea; the cold, wet England; the Ellis Island; the hunger; the aching of one who has no love, no money! And now—I have the morning star!"

He looked at us all three at once—Charlie Sands said this was impossible, until he met Tufik. Aggie was fairly palpitant and Tish was smug, positively smug. As for me, I roused with a start to find myself sugaring my ice cream.

Charlie Sands was delayed that night. He came in about nine o'clock and found Tufik telling us about his home and his people and the shepherds on the hills about Damascus and the olive trees in sunlight. We half-expected Tufik to adopt Charlie Sands as a father; but he contented himself with a low Oriental salute, and shortly after he bowed himself away.

Charlie Sands stood looking after him and smiling to himself. "Pretty smooth boy, that!" he said.

"Smooth nothing!" Tish snapped, getting the bridge score. "He's a sad-hearted and lonely boy; and we are going to do the kindest thing—we are going to help him to help himself."

"Oh, he'll help himself all right!" observed Charlie Sands. "But, since his people are Christians, I wish you'd tell me how he knows so much about the inside of a harem!"

Seeing that comment annoyed us, he ceased, and we fell to our bridge game; but more than once his eye fell on Aggie's doily, and he muttered something about the Assyrian coming down like a wolf on the fold.

The problem of Tufik's future was a pressing one. Tish called a meeting of the three of us next morning, and we met at her house. We found her reading about Syria in the encyclopędia, while spread round her on chairs and tables were numbers of silk kimonos, rolls of crocheted lace, shirt-waist patterns, and embroidered linens.

Hannah let us in. She looked surly and had a bandage round her head, a sure sign of trouble—Hannah always referring a pain in her temper to her ear or her head or her teeth. She clutched my arm in the hall and held me back.

"I'm going to poison him!" she said. "Miss Lizzie, that little snake goes or I go!"

"I'm ashamed of you, Hannah!" I replied sternly. "If out of the breadth of her charity Miss Tish wishes to assist a fellow man—"

Hannah reeled back and freed my arm.

"My God!" she whispered. "You too!"

I am very fond of Hannah, who has lived with Tish for many years; but I had small patience with her that morning.

"I cannot see how it concerns you, anyhow, Hannah," I observed severely.

Hannah put her apron to her eyes and sniffled into it.

"Oh, you can't, can't you!" she wailed. "Don't I give him half his meals, with him soft-soapin' Miss Tish till she can't see for suds? Ain't I fallin' over him mornin', noon, and night, and the postman telling all over the block he's my steady company—that snip that's not eighteen yet? And don't I do the washin'? And will you look round the place and count the things I've got to do up every week? And don't he talk to me in that lingo of his, so I don't know whether he's askin' for a cup of coffee or insultin' me?"

I patted Hannah on the arm. After all, none of the exaltation of a good deed upheld Hannah as it sustained us.

"We are going to help him help himself, Hannah," I said kindly. "He hasn't found himself. Be gentle with him. Remember he comes from the land of the Bible."

"Humph!" said Hannah, who reads the newspapers. "So does the plague!"

The problem we had set ourselves we worked out that morning. As Tish said, the boy ought to have light work, for the Syrians are not a laboring people.

"Their occupation is—er—mainly pastoral," she said, with the authority of the encyclopędia. "Grazing their herds and gathering figs and olives. If we knew some one who needed a shepherd—"

Aggie opposed the shepherd idea, however. As she said, and with reason, the climate is too rigorous. "It's all well enough in Syria," she said, "where they have no cold weather; but he'd take his death of pneumonia here."

We put the shepherd idea reluctantly aside. My own notion of finding a camel for him to look after was negatived by Tish at once, and properly enough I realized.

"The only camels are in circuses," she said, "and our duty to the boy is moral as well as physical. Circuses are dens of immorality. Of course the Syrians are merchants, and we might get him work in a store. But then again—what chance has he of rising? Once a clerk, always a clerk." She looked round at the chairs and tables, littered with the contents of Tufik's pasteboard suitcase, which lay empty at her feet. "And there is nothing to canvassing from door to door. Look at these exquisite things!—and he cannot sell them. Nobody buys. He says he never gets inside a house door. If you had seen his face when I bought a kimono from him!"

At eleven o'clock, having found nothing in the "Help Wanted" column to fit Tufik's case, Tish called up Charlie Sands and offered Tufik as a reporter, provided he was given no nightwork. But Charlie Sands said it was impossible—that the editors and owners of the paper were always putting on their sons and relatives, and that when there was a vacancy the big advertisers got it. Tish insisted—she suggested that Tufik could run an Arabian column, like the German one, and bring in a lot of new subscribers. But Charlie Sands stood firm.

At noon Tufik came. We heard a skirmish at the door and Hannah talking between her teeth.

"She's out," she said.

"Well, I think she is not out," in Tufik's soft tones.

"You'll not get in."

"Ah, but my toes are in. See, my foot wishes to enter!" Then something soft, coaxing, infinitely wistful, in Arabian followed by a slap. The next moment Hannah, in tears, rushed back to the kitchen. There was no sound from the hallway. No smiling Tufik presented himself in the doorway.

Tish rose in the majesty of wrath. "I could strangle that woman!" she said, and we followed her into the hall.

Tufik was standing inside the door with his arms folded, staring ahead. He took no notice of us.

"Tufik!" Aggie cried, running to him. "Did she—did she dare—Tish, look at his cheek!"

"She is a bad woman!" Tufik said somberly. "I make my little prayer to see Miss Tish, my mother, and she—I kill her!"

We had a hard time apologizing to him for Hanna. Tish got a basin of cold water so he might bathe his face; and Aggie brought a tablespoonful of blackberry cordial, which is soothing. When the poor boy was calmer we met in Tish's bedroom and Tish was quite firm on one point—Hannah must leave!

Now, this I must say in my own defense—I was sorry for Tufik; and it is quite true I bought him a suit and winter flannels and a pair of yellow shoes—he asked for yellow. He said he was homesick for a bit of sunshine, and our so somber garb made him heart-sad. But I would never have dismissed a cook like Hannah for him.

"I shall have to let her go," Tish said. "He is Oriental and passionate. He has said he will kill her—and he'll do it. They hold life very lightly."

"Humph!" I said. "Very well, Tish, that holding life lightly isn't a Christian trait. It's Mohammedan—every Mohammedan wants to die and go to his heaven, which is a sort of sublimated harem. The boy's probably a Christian by training, but he's a Mohammedan by blood."