Dorothy Payne Todd.

Courtesy of Miss Lucia B. Cutts.

Dorothy Payne Todd.

Courtesy of Miss Lucia B. Cutts.

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Dorothy Payne, Quakeress, by Ella Kent Barnard

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net

Title: Dorothy Payne, Quakeress

A Side-Light upon the Career of 'Dolly' Madison

Author: Ella Kent Barnard

Release Date: December 19, 2010 [EBook #34690]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK DOROTHY PAYNE, QUAKERESS ***

Produced by Carla Foust, Tor Martin Kristiansen and the

Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

(This book was produced from scanned images of public

domain material from the Google Print project.)

Minor punctuation errors have been changed without notice. Printer errors have been changed, and they are indicated with a mouse-hover and listed at the end of this book. All other inconsistencies are as in the original.

Some page numbers in the list of Illustrations reflect the position of the illustration in the original text, but links link to current position of illustrations.

Some page numbers in the Index reflect the position of footnotes in the original text.

Dorothy Payne Todd.

Courtesy of Miss Lucia B. Cutts.

Dorothy Payne Todd.

Courtesy of Miss Lucia B. Cutts.

By Ella Kent Barnard

Philadelphia:

FERRIS & LEACH

29 SOUTH SEVENTH ST.

1909

Dedicated to

Annie Matthews Kent

There is little time in this busy world of ours for reading,—little, indeed, for thinking;—and there are already many books; but perhaps these few additional pages relating to Dolly Madison, who was loved and honored during so many years by our people, may be not altogether amiss. During eleven administrations she was the intimate friend of our presidents and their families. What a rare privilege was hers—to be at home in the families of Washington, of Jefferson, of Madison, of Monroe; to know intimately Hamilton and Burr and Clay and Webster; to live so close, during her long life, to the heart of our nation; to be swayed by each pulsation of our national life;—to be indeed a part and parcel of it all, loved, honored and revered!

It seems almost incredible that the simple country maiden, reared in [8]strict seclusion, by conscientious Quaker parents, should have been transformed into the queen of social life, at whose shrine the wise men of their day did homage, and at whose feet the warriors laid the flag of victory.

She has left small record of her thoughts; none of her creed, excepting in her life,—and that was pure and good. The outward symbols of her faith were laid aside, but in her daily life we see the leading of the "Inner Light."

We have searched amongst the driftwood of the century for traces of her early life, and found many records, letters and references, published and unpublished, and from them all our story has been woven.

The Friends' records of North Carolina, of Virginia and of Philadelphia have given us very accurate and definite information relating to her family, and the old letters, the cherished treasures of many homes, have [9]given a glimpse of Dolly herself in earlier and later days;—of her Quaker girlhood in Philadelphia and of her marriage in the old Pine street meeting-house. And then of days in Washington,—brilliant days, in the full glare of sunshine; and finally a picture when the days were far spent and the evening shadows falling.

For much of this material I am greatly indebted to many persons, and especially to the following I wish to express my heartfelt gratitude for assistance so kindly given: George J. Scattergood, Philadelphia; Edward Stabler, Jr., Baltimore; Eliza Pleasants, Lincoln, Va.; Maud Wilder Goodwin, New York City; Priscilla B. Hackney, North Carolina; Rosewell Page, Richmond, Va.; Lavinia Taylor, Hanover County, Va.; Lucia B. Cutts, Boston, Mass.; L. D. Winston, Winston, Va.; Christine M. Washington, Charlestown, W. Va.; George S. Washington, Philadelphia; [10]Eugenia W. M. Brown, Washington, D. C.; Julia E. Daggett, Washington, D. C.; Lucy T. Fitzhugh, Westminster, Md.; Margaret Crenshaw, Richmond, Va.; Charles G. Thomas, Baltimore, Md.; Mrs. Moorfield Story, Boston, Mass.; Julia S. White, North Carolina; Thomas Nelson Page, Washington, D. C.; Richard L. Bentley, Baltimore; Thomas F. Taylor, Hanover, Va.; Mary W. Slaughter, Winston, Va.; Liza Madison Sheppard, Virginia; Samuel M. Brosius, Washington, D. C.; Elizabeth McKean, Washington, D. C.; Mrs. William DuPont, Montpelier, Va., and Norman Penney, London, England.

Baltimore, November 15, 1909.

| I. | Early Years and Scenes | 17 |

| II. | Marriage and Widowhood | 59 |

| III. | Washington and the White House | 88 |

| IV. | Later Years | 110 |

| Index | 126 |

| Dorothy Payne Todd, at 21 | Frontispiece |

From a Miniature on ivory, now in possession of Mrs. Richard D. Cutts.

| Heading—Drawn by Ella K. Barnard | 17 |

| Friends' Meeting House, New Garden, North Carolina | 18 |

From an old drawing.

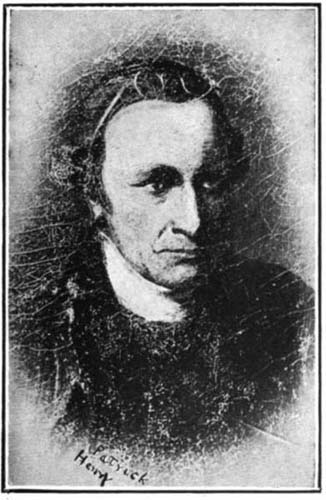

| Patrick Henry | 20 |

From a painting by Sully in the State Library, Richmond, Va.

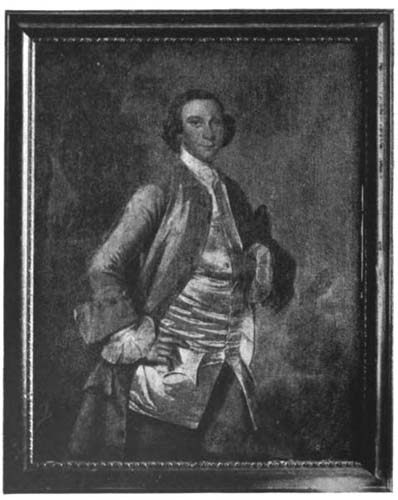

| Colonel William Byrd | 30 |

From a painting at Brandon.

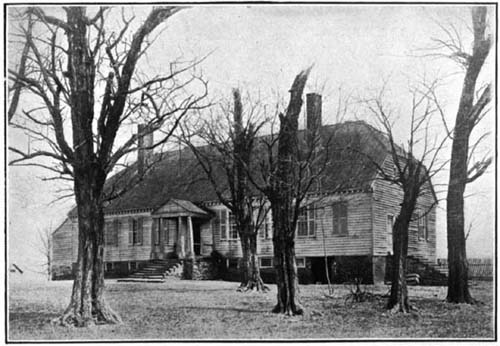

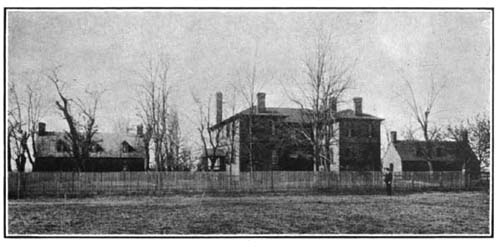

| Scotch Town, Hanover County, Virginia | 34 |

From a photograph.

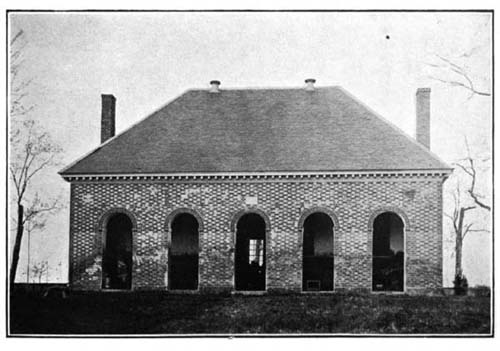

| Negrofoot House | 36 |

From a photograph.

| The Dandridge Home | 50 |

From a photograph.

| Hanover Court House[14] | 52 |

From a photograph.

| Heading—Drawn by Ella K. Barnard | 59 |

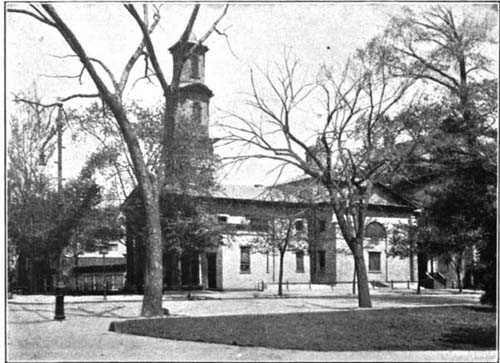

| Pine Street Meeting House | 66 |

Drawn after a photograph.

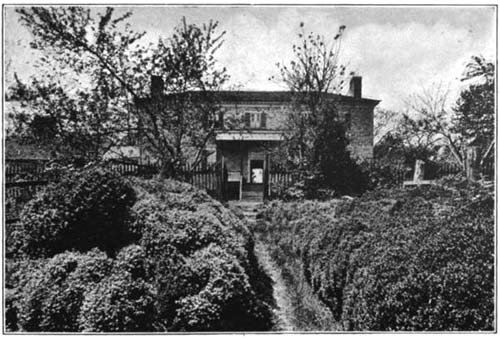

| Harewood, from the Garden | 80 |

From a photograph.

| The Parlor, Harewood | 82 |

Wherein James and Dolly Madison were married.

From a photograph.

| James Madison and Dolly Madison | 86 |

From the portraits by Gilbert Stuart, owned by The Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts.

| Heading—Drawn by Ella K. Barnard | 88 |

| Colonel Samuel Washington | 89 |

From a painting at Harewood.

| Montpellier, the Madison estate in Orange County, Va | 101 |

From a photograph.

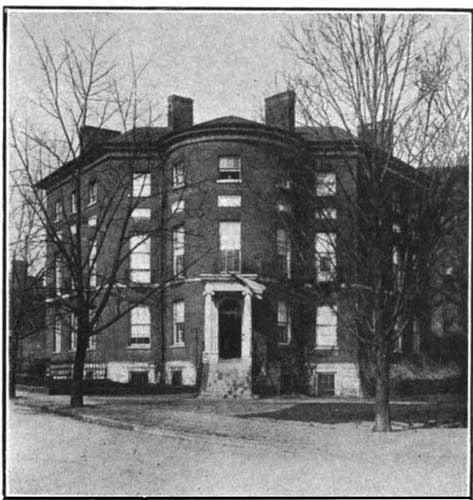

| The Octagon House, Washington, D. C. | 108 |

From a photograph.

| Mantel in the Octagon House[15] | 109 |

From a photograph.

| Detail of Madison China from the White House | 109 |

After drawing by Harry Fenn.

| Heading—Drawn by Ella K. Barnard | 110 |

| Dolly Madison in later years | 113 |

From a Water-Color by Mary Estelle Cutts, now in possession of Miss Lucia B. Cutts.

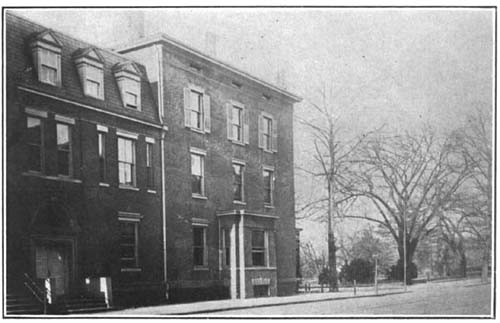

| Madison House, Washington, D. C., North View | 114 |

From a photograph.

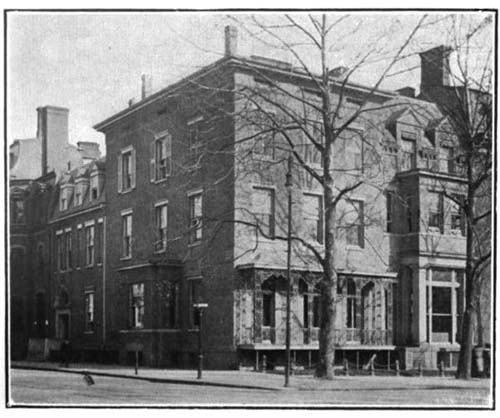

| Madison House, Washington, D. C., West View | 115 |

From a photograph.

| St. John's Church, Washington, D. C. | 123 |

From a photograph.

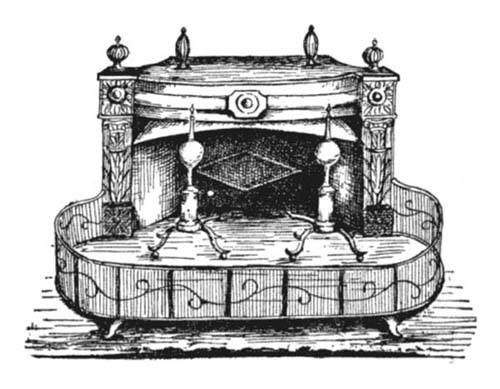

| Tailpiece—Franklin Stove | 125 |

Drawn by Ella K. Barnard

| Tailpiece—James Madison's Cloak-Clasp | 128 |

Drawn by Ella K. Barnard

The girlhood of Dorothy Payne was spent on a plantation in Hanover county, Virginia. Very quiet and uneventful were the years whose "days were full of happiness," the quiet happiness of country life. For fifteen years

where the distant echoes of the busy world, or even the great Revolutionary struggles that encompassed them round about, scarce caused a ripple on the calm surface of their daily life.

She was born, however, in North Carolina, that happy region where "every one does what seems best in his own eyes," or, better still, enjoys, as did Colonel Byrd, "the Carolina felicity of hav[18]ing nothing to do!" A rough people many of them still were, without doubt, when the little Dolly was born in their midst, on a plantation in Guilford county, to take charge of which her father had come a few years before from his Virginia home to where a thrifty, God-fearing colony of Quaker emigrants from New Garden, Pennsylvania, had peopled the wilderness, and in memory of the Pennsylvania home had erected a new "New Garden Meeting House" in a forest clearing. Very commodious it looked in comparison with the log cabins from which its congregation gathered to "mid-week" and "First-day Meeting," coming usually in the covered emigrant wagon that was ofttimes their only means of conveyance, but which well suited the size of the emigrant family.

Friends' Meeting House, New Garden, North Carolina.

From an old Drawing.

Friends' Meeting House, New Garden, North Carolina.

From an old Drawing.

Turning over their earliest book of records, still distinct but yellowed by age, the curious visitor may find a page on which is inscribed the following:

John Payne was born ye 9 of ye 12 mo 1740.

Mary, his wife, was born ye 14 of ye 10 mo 1743.

Walter, their son, was born ye 15 of ye 11 mo 1762.

Wm. Temple, their son, was born ye 17 of ye 6 mo 1766.

Dolley, their daughter, was born ye 20 of ye 5 mo 1768.

"Dolley," their little daughter, was named for her mother's friend, Dorothea Spotswood Dandridge, the granddaughter of Governor Spotswood, the daughter of Nathaniel West Dandridge, a near relative of Lord Delaware. Nathaniel West Dandridge, son-in-law of Governor Spotswood, had been one of his followers on a far-famed journey of exploration, led by the Governor, beyond the Appalachian mountains, and for this exploit had been dubbed a "Knight of the Golden Horseshoe," and presented with the symbol of the order, a golden horseshoe with its glittering jewels, and the inscribed motto, "Sic juvat transcendere montes," made in memory of their trip.

A few years earlier a cousin of Dolly Dandridge, from her own home, the White House on the Pamunky, had been married to Colonel Washington, a gallant young officer lately elected to the House of Burgesses. A few years later Dolly Dandridge herself became the second wife of Patrick Henry, the cousin of Mary[20] Payne, a young lawyer of Hanover county, whose eloquence had electrified the House of Burgesses, and who was now its acknowledged leader in the fight against English taxation.

Patrick Henry.

Patrick Henry.

Very slight seems the connection between these events and people and the little Quaker maiden, but it was through these, her mother's friends, that she was drawn in and became one of that choice circle of Virginia's honored children in the early days of the Republic.

Though born in North Carolina she was but one year old when her parents returned to their former home in Hanover county, Virginia, and in later years Dolly always preferred to call herself a Virginian, for it was around the old Scotch Town homestead that all her loving memories clustered. It was in Virginia, too, that she imbibed the early training that fitted her to become a graceful, tactful leader in the nation's social life. Generations of worthy ancestors had transmitted to her the instincts of a lady, a warm and loving heart, and an appreciation of true worth, traits that were to serve her well in after years.

[21]The grandfather, Josias Payne[1], gentleman, was the son of George Payne, justice and high-sheriff of Goochland, who was descended from one of "Virginia's Adventurers," a younger brother of Sir Robert Payne, M.P. from Huntingdonshire, England. Josias Payne had become the owner of thousands of acres of Virginia's richest land along the James river. He was a man of affairs, a vestryman, and a member of the House of Burgesses.

The English traveler Smythe has given a pleasing picture of the Virginia gentleman. "These in general have had a liberal education, possess enlightened understanding and a thorough knowledge of the world, that furnishes them with an ease and freedom of manners and conversation highly to their advantage in exterior, which no vicissitudes of fortune or place can divest them of, they being actually, according to my ideas, the most agreeable [22]and best companions, friends and neighbors that need be desired. The greater number of them keep their carriages and have handsome services of plate; but they all, without exception, have studs, as well as sets of elegant and beautiful horses."[2]

The picture, too, had ofttimes another side, for not all the gentlemen could afford to send their children to England to be educated, and men of "mean understandings" were sent to the House of Burgesses, and so trying were they to the nerves of Governor Spotswood that he cuttingly observes that "the grand ruling party in your House has not furnished chairmen of two of your standing committees who can spell English or write common-sense, as the grievances under their own handwriting will manifest."

Anne Fleming,[3] the wife of Josias [23]Payne, was the granddaughter of Sir Thomas Fleming of New Kent county, the second son of the Earl of Wigdon. From this worldly grandmother doubtless came the present of the jewelry treasured so long by the little Dolly during her school days, and safely hid in a tiny bag around her neck, until one sad day when it disappeared, on her way to school, never to be found again.

This same Anne Fleming was also said to be the wife of John Payne (a cousin of Josias). Surely his wife's name was also Anne, for an old court record shows that "Hampton and Sambo," negroes belonging to "John Payne, gentleman," were brought to trial in 1756 for "Prepairing[24] and administering Poysonous Medecines to Anne Payne," for which offence the said Hampton was declared guilty and sentenced to "be hanged by the neck till he be dead, and that he be afterwards cut in Quarters and his Quarters hung up at the Cross Roads." And his master was awarded the sum of £45, the "adjudged value of Hampton," according to law. The dark shadow of slavery was already gathering over the land, although scarcely perceived and yet unacknowledged by the great majority of the people.

In the vestry meetings the chief plant[25]ers became the veritable rulers of the adjacent neighborhood. "The care of the poor, the survey of estates, the correction of disorders, the tithe rates, and the maintenance of the church and minister" came within their province. As a justice the planter was one of five to preside at all trials of the negroes, they not being allowed a trial by jury, but on the agreement of the five they were freed or condemned and sentenced. Such tasks as these, with the oversight of his estate and his duties in the House of Burgesses, made the Virginia gentleman a busy man. Still, he never allowed his life to become a strenuous one, but found ample time for his pleasures and for his social duties. Fond of good living, he was unlike the Frenchman, who "feasts on radishes that he may wear a ribbon," for the Virginian "took his ease in homespun that he might dine on turtle and venison."

John Payne received the breeding of the Virginia gentleman of the old school, and grew to manhood possessing the charms of courtly manners and of fluent speech. The early Virginia records speak of him as "John Payne, junior." In 1763[26] he inherited a plantation on Little Bird Creek, of two hundred acres, "on which he was then living," from "John Payne, elder." To this tract his father added a gift of another two hundred acres, likewise on Little Bird Creek, and at his death (1785) willed him four hundred additional acres of rich bottom land in "the forks of the James," with the negroes "Peter, Ned and Bob."

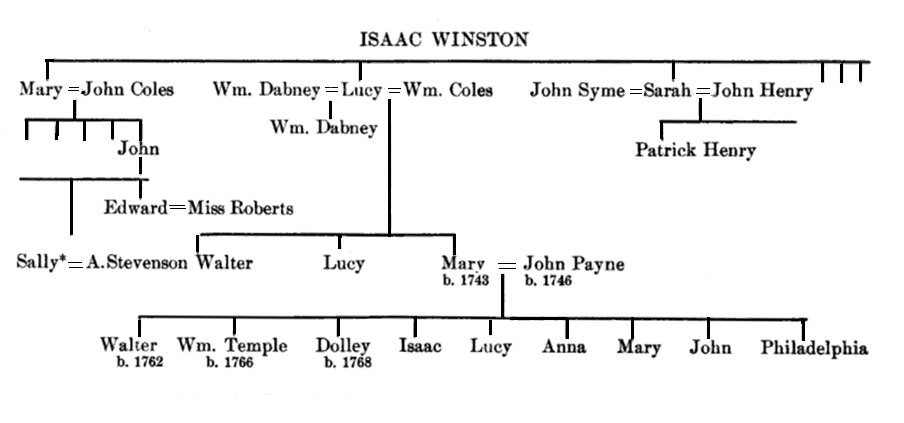

To this early home he brought his girlish wife, beautiful Mary Coles. Mary Coles was the daughter of William Coles of "Coles Hill," Hanover county, a younger brother of John Coles,[4] of Richmond, Virginia, who had there as a merchant [27]amassed a fortune, and married Mary Winston.

William Coles came later to America from Enniscorthy, Ireland, and married Lucy, the sister of his brother's wife, then the widow of William Dabney, by whom she had one son, William. William and Lucy Winston Coles had three children: Walter; Lucy, who married her cousin Isaac Winston, and Mary, the wife of John Payne, and mother of Dolly Madison.

Lucy Winston came of a Quaker family that has, perhaps, furnished more men of note than any other in our country. Her father, Isaac Winston,[5] emigrant, was an able man of an old Yorkshire family that had settled in Wales. He, with several brothers, came to Virginia to escape the Quaker persecution in England, settling first in Henrico and afterwards in Hanover county, where he died in 1760, at an advanced age. He had acquired a large estate, and many negroes. What a gratification it would have been to the old man had he lived a few years longer and heard his wayward grandson, Patrick Henry, argue the "Parson's cause," or make his first great speech in the House of Burgesses. As it was he died thinking the young orator unworthy even of mention in his will, but for his sisters he carefully provided. To his granddaughters Lucy and Mary Coles he willed £45, to be paid to them when they came of age or married.

* Sally Coles Stevenson's letters from England have been recently published in the "Century Magazine." She was the sister of Edward

Coles, Secretary of President Madison and second Governor of Illinois.

* Sally Coles Stevenson's letters from England have been recently published in the "Century Magazine." She was the sister of Edward

Coles, Secretary of President Madison and second Governor of Illinois.

Isaac Winston's son William had wild blood in his veins, and was a great[29] hunter and beloved by the Indians in their western wilds, where he had a hunting lodge. The elder Wirt pronounced him an orator scarcely inferior to his nephew, Patrick Henry, who was said to have inherited his rare gift of eloquence from his Quaker ancestors. An old letter[6] from Albemarle county claims that it was to him more than to Washington that the credit of saving the day at the time of Braddock's defeat was due. The troops had refused to move farther, and Washington's remonstrances availed not, until William Winston sprang to the front and addressed them with such stirring eloquence that each one threw up his hand [30]and demanded to be led forward. Judge Edmund Winston, son of William Winston, read and practiced law with his cousin Patrick Henry, and the firm of Henry and Winston carried all before it. Patrick Henry died in 1799, and Judge Winston married his widow, "Dolly Dandridge," and died in 1813 in the "fifth score year of his age."

"Dolly Dandridge" died in 1831. "Cousin Dolly" she always was to her namesake, Dolly Madison.

Colonel William Byrd.

Colonel William Byrd.

Colonel William Byrd of Westover, a polished gentleman and wit (but, alas! also a "spendthrift and gambler"), in his "Progress to the Mines" called on Sarah Syme,[7] then a widow, formerly "Sarah Winston, of a good old family." "This lady, suspecting I was some lover, put on a gravity which becomes a weed, [31]but as soon as she learned who I was brightened up into an unusual cheerfulness and serenity. She was a portly, handsome dame, of a lively, cheerful conversation, with much less reserve than most of her countrywomen. It became her very well, and set off her other agreeable qualities to advantage." "The courteous widow invited me to rest myself there that good day, and go to church with her, but I excused myself by telling her she would certainly spoil my devotions. Then she civilly entreated me to make her house my home whenever I visited my plantations, which made me bow low and thank her very kindly. She possessed a mild and benevolent disposition, undeviating probity, correct understanding and easy elocution." For his supper Colonel Byrd writes that he was served with a "broiled chicken" and a "bottle of honest port," and no doubt he came again!

Sarah Winston afterward married John Henry,[8] a man of Scotch ancestry and sterling worth, who for some time [32]represented his county of Hanover in the House of Burgesses, where later the three brothers, John Syme, and William and Patrick Henry, sat year after year.

The name of one more member of this family will occur in later pages:—William Campbell Preston, M.C. from South Carolina, the opponent of John C. Calhoun in "nullification days" (1832).

Other branches of the family furnished men of great ability, congressmen, senators, governors, warriors. To-day the United States Senate mourns the vacant seat of that "grand old man" Edmund Winston Pettus,[9] who died recently in his eighty-seventh year, the oldest man in public life in the United States, and Alabama loved him as a father.

The daughters of the family, too, inherited the ready flow of language, the quick wit and pleasing address characteristic of the family, and which, added to good looks, made them much sought in [33]marriage. In after years these same qualities made them worthy helpmates in smoothing out the social tangles of official life.

In an old letter found amongst some Quaker manuscripts from Virginia, bearing date of 1757, was found the statement that "Thomas Cole and William Cole have both made open confessions of truth." This William Cole, or Coles, was probably the husband of Lucy Winston, of whom a sweet picture in Quaker dress is preserved.

Soon after their marriage John and Mary Payne made application for membership with the Quakers of Cedar Creek, in which neighborhood they were then living, as shown by the minutes of Cedar Creek Monthly Meeting, dated 5th month 30th, 1764. In 11th month 30th, 1765, they were already settled in North Carolina. In 4th month, 1769, they with their three children were again living in Hanover county, Virginia. During these and the few following years three children who were probably theirs were buried at South River, "Mary, William and Ruth Paine."[34]

In 1775 Patrick Henry, the newly-appointed Governor of Virginia, sold his farm called "Scotch Town" to John Payne. It was considered a valuable tract of land, and a bargain when it came into the hands of Henry in 1771 for £600. It had been literally "Scotch Town" in earlier colonial days, the center of a Scotch settlement of which it was the "great house." Here John Payne brought his rapidly-increasing little family, but in its nineteen rooms there was room and to spare for them all, and for the guests who so often sought its hospitable shelter.

Scotch Town, Hanover County, Virginia.

Photographed by Samuel M. Brosius.

Scotch Town, Hanover County, Virginia.

Photographed by Samuel M. Brosius.

This house, with its quaint hipped roof, is standing to-day, and it needs only a thatched covering, and the peaked dormer windows that were perhaps there in earlier days, to make it a typical old English cottage. The two great chimneys have been much changed. In olden times each served for the four rooms clustered about it, and from which it took generous corners. Above the great open fire-places were mantels of black marble, one of which was supported by white figures. These mantels and the three granite porticos, with their carved steps, were brought[35] from Scotland by Mr. Forsythe, the builder, as was also the brick for the lower half-story. The house, too, boasts a dungeon that may have been used for protection or for the punishment of offenders two hundred years ago, about which time its building dates. A broad hall ran through the house, and above either wide doorway the portico roof was supported by iron brackets. The back door opens on the old garden, where the box trees still flourish, but the ancient trees around the lawn are veterans hoary and maimed by the storms of many years.

Here Patrick Henry, already famous, lived, and Dolly Payne, a blue-eyed, merry little lassie, sat beside her mother in the family room, "the blue room," with its walnut wainscoting trimmed with pine, and solid walnut doors, and learned to sew and read. Scotch Town stands on high ground, and for miles around you can see an unbroken stretch of country. In colonial days about it were clustered numerous outbuildings, fine stables and the negro quarters, of which there is now no trace.

Happy days were spent here by the[36] little Dolly. Surely they had few cares for the little daughter so carefully guarded by "Mother Amy," her much-loved colored nurse; and there were other slaves to do her bidding. It was through them, doubtless, that she first heard the horrible story of the crime of "Negrofoot," now the name of the post-office on an adjoining plantation. The stranger naturally queries, Why Negrofoot? and is told the old story of an African slave, a cannibal, owned by a Mr. Jarman:—how, when the master and mistress were at church one day, he took the little two-year-old child from its nurse, killed it, and partly devoured it before its parents returned. The retribution was swift and terrible. A wild horse was brought, the slave tied to it, and the horse started on a mad run. Before it had ended, the slave, too, was dead. His body was then dismembered, and portions nailed up in different parts of the country. The foot put up here gave the name to Negrofoot-house, and to the post-office; and doubtless weird stories were told by the superstitious negroes, who shunned the scenes of the double crime.

Negrofoot House.

Photographed by Samuel M. Brosius.

Negrofoot House.

Photographed by Samuel M. Brosius.

Coles Hill was but nine miles off,[37] one of those low story-and-a-half Virginia houses, built of frame, whose timbers were probably cut by the family servants. Two rooms, one on either side the wide hall, sufficed, with the broad porch, for summer living, and the quaint bedrooms peered out through dormer windows from the roof above. There were outbuildings, too, on the north and east sides, and a few cabins for the negroes. (The residence has long ago disappeared, and the land is owned by George Doswell).

It was but a pleasant drive from Scotch Town on a "First-day after meeting" for John and Mary Payne, and the children loved to gather around the dark-eyed young grandmother, whose Quaker cap would not quite conceal the stray curls that refused to be confined by its sheer crispness. To her Irish grandsire Dolly owed much. From him she had inherited a fine clear complexion, whose worth was appreciated by her mother, and guarded by the linen face-mask carefully sewed in place, and the long gloves always to be drawn on ere she dared venture into the sunshine, a preparation that must[38] have been trying indeed to the impatient little girl. Her Irish blood, too, had added warmth to her loving heart, and given her the quick wit and smooth tongue that caused her to be accused, in later days, of a "knowledge of the groves of Blarney."

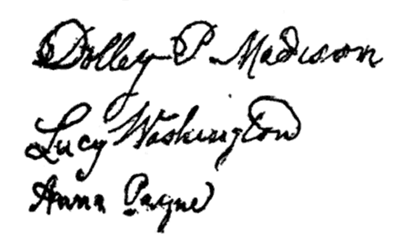

On their return to Virginia John and Mary Payne both became zealous workers in the Society of Friends, or Quakers. John Payne was for many years clerk of Cedar Creek Monthly Meeting, while Mary Payne was from time to time clerk of the women's meeting. They were also "elders," and it is likely that John Payne became a "minister," for as early as 1773 we find he is reported as "desiring to visit friends in Amelia, and also at Pine Creek." In 1777 and 1779 "John Payne requests a certificate to attend North Carolina Yearly Meeting," then held at Old Neck, Perquimans county. For years, too, there is scarcely a committee appointed of which he is not a member, and the carefully-written pages of the record books, as clear and distinct as when first recorded, show that both he and his wife were beautiful penmen. In[39] Dolly's early signatures her last name is almost a facsimile of her mother's writing, but her spelling never equalled that of her parents for correctness. Papers like the following, signed by both John and Mary Payne, were of frequent occurrence.

"Whereas Milley Hutchings, Daughter of Strangeman Hutchings, of Goochland County, was Educated in the profession of us the people Call'd Quakers, but for want of living agreeable to the principles of Truth hath suffered herself to be Joined in marriage to a man of a different persuasion from us in matters of Faith, by an Hireling priest, contrary to the known rules of our discipline, therefore we think it our duty, for the clearing of our profession of such libertine persons, publickly to disown the said Milley from being a Member of our Society, untill she give satisfaction for her outgoing, which we desire she may be enabled to do. Signed in and on behalf of our Monthly Meeting held at Cedar Creek in Hanover County the

13th of 3d m 1779 by

John Payne Clerk

Mary Payne Clerk[10]

Was it well that they could not see far into the future?[40]

The great problem of the Friends during these years, the one in which John Payne was most vitally interested, was the freeing of their negroes or "black people," as (when assembled in Yearly Meeting) they had gravely decided to call them. Years before, the Quakers had crossed the seas in search of civil and religious liberty, and while they believed in each man's "inalienable right" to "life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness," they could not seek them by a resort to arms. In the Revolution they could take no part, but there was sufficient work for them at home. Before slavery, even in their own midst, could be abolished, the members of the legislature must be convinced, and new state laws framed. Of this work in the South, Thomas Nelson Page says: "The movement was largely owing in its inception to the efforts of the Quakers, who have devoted to peace those energies which others had given to war, and who have ever been moved by the Spirit to take the initiative in all action[41] which tends to the amelioration of the human race." In his own state he considered the "problem stupendous, but it was not despaired of. Many masters manumitted their slaves, the example being set by numbers of the same benevolent sect [Quakers] to which reference has been made."

Already in 1769 the members of Cedar Creek Monthly Meeting had been "unanimously agreed that something be done." The laws of Virginia threw many obstacles in their way, and it was not until the law passed in 1782 that the right of emancipation was given to the owners of slaves. For this tardy permission they could not wait, and Robert Pleasants[11] in [42]a letter dated "Curles,[12] 3d month 28th, 1777," wrote to the Governor, Patrick Henry, Jr., " ... It is in respect to slavery, of which thou art not altogether a stranger to mine, as well as some others of our Friends' sentiments; and perhaps, too, thou may have been informed that some of us, from a full conviction of the injustice, and apprehension of duty, have been induced to embrace the present favorable juncture when the Representatives of the people have nobly declared all men free, without any desire to offend, or thereby injure any person, to invest more of them with the same inestimable privilege. This I conceive was necessary to inform the governor...."

The Friends were tolerably sure of Patrick Henry's support, as in a letter to Edward Stabler in 1773 he said: "It would rejoice my very soul that every one of my fellow-beings was emancipated. We ought to lament and deplore the necessity of holding our fellow-men in bondage. Believe [43]me, I shall honor the Quakers for their notable efforts to abolish slavery."

P. Henry

P. Henry

In 1778 "The Meeting directs that the sum of 30/ be raised for the payment of a book purchased for the purpose of Recording manumissions. John Payne is appointed to record them, and when accomplished to deliver the originals into the care of Micajah Crew according to the direction of the Meeting."

The following manumission paper is one of twenty-one issued about this time by Thomas Pleasants, the intimate friend of John and Mary Payne, and is signed by them as witnesses.

MANUMISSION PAPER.[13]

I Thomas Pleasants of Goochland County in Virginia from mature deliberate consideration and the convictions of my own mind being fully persuaded that freedom is the natural birthright of all mankind and that no Law moral or divine has given me a right to or property in the persons of any of my fellow creatures, and being desirous to fulfil the injunction of our Lord and Saviour Jesus Christ by doing to others as I would be done by. Do therefore declare that having under my care one negro woman named Betty aged about forty, I do for myself my Heirs Executors and administrators hereby release unto her the said Betty all my right Interest and claim or pretensions of claim whatsoever as to her person or to any Estate she may hereafter acquire without any interruption from me or any person claiming for by from or under me In WITNESS whereof I have hereunto set my hand and seal this 25th day of the 1st Month, one thousand and seven hundred and Eighty

Sealed and delivered

in presence of

Tho Pleasants (Seal) John Payne Mary Payne

John Payne likewise manumitted all his slaves before his removal to Philadelphia.

After the passage of the law of 1782 the Friends no longer hesitated, and their slaves, as far as permitted by law, were generally freed. At the same time their owners, who had thus made themselves obnoxious to their slave-owning neigh[45]bors, prepared to remove to a free state, the great majority to the west. John Payne had for some years been looking forward to a removal to Philadelphia, where his son Walter was already established in business.

Their movements about this time are definitely ascertained by a reference to the Quaker records:

Cedar Creek, 8 mo. 11, 1779—"By a report from Cedar Creek Preparative Meeting, it appears that Walter Payne has removed to Philadelphia. Micajah Terrel, James Hunnicutt, Moses Harris and Micajah Davis are appointed to prepare a certificate for him, and assign the same in behalf of the Monthly Meeting if nothing obstructs."

"On the 13th of 1st month, 1781, Mary Payne informed this meeting that she proposed in some short time a journey to Philadelphia, and requests a few lines certifying her right of membership with us."

Which certificate is directed to be drawn up and signed.

Elizabeth Drinker, wife of Henry Drinker, of Philadelphia, records in her diary:

1781, March 5—"Molly Payne spent ye day, and lodged with us. She and son Walter breakfasted ye 6th."

And finally the meeting records:

"On the 21st of Second Month, 1783, John Payne requests a certificate for himself and family to join themselves to Friends in Philadelphia. Micajah Crew and Moses Harris are appointed to make the necessary enquiry, and if nothing appears to hinder, produce one accordingly at next meeting."

This committee seems to have thought that John Payne could not properly discharge his duties as executor from the distant town of Philadelphia. Accordingly, at the next meeting, held the following month:

"James Crew is appointed to receive the estate of Elizabeth Elmore, deceased, from John Payne, executor, and give us account thereof at next meeting. Micajah Crew, James Jarvis and James Hunnicutt are appointed to assist him in devising the said Elizabeth Elmore's cloths and to give their advice and assistance in settling all other matters that may come before them, respecting the estate."

And as John Payne is about to remove without the verge of this Meeting, James Hunnicutt is therefore appointed clerk thereof in his stead."

It will be seen that this little community looked carefully after the various interests of its members. Their "temporal" as well as "spiritual" affairs were within its province, to advise and admonish as seemed best to them.

[47]The investigation having been entirely satisfactory otherwise, the following month a certificate of removal is granted from "Caeder Creek Monthly Meeting, held in Hanover county, Virginia, bearing date of 12th of 4th mo., 1783, for John and Mary Payn and their children: William Temple, Dolly, Isaac, Lucy, Anne, Mary and John," directed to the "Northern District Mo. Mtg. of Philadelphia."

The form of this certificate was probably like the following one drawn up by John Payne as clerk:

"To the Monthly Meeting held at Southriver.

Dear Friends:

"Our writing to you at this time is on account of David Terrill, who now resides within the verge of your Meeting, and requests our Certificate for himself and children. These may certify, that after the needful enquiry, we have cause to believe his affairs are settled to satisfaction. His life and conversation being in a good degree orderly whilst among us, we therefore recommend him, together with his children [namely: ....] to your Christian care, and with desires for their growth in the truth, we remain your friends and brethren.

"Signed on behalf of our Monthly Meeting held at Cedar Creek, 8 mo. 24th, 1781.

[48]And Elizabeth Drinker records again:

"1783, July 9.—John Payne's family came to reside in Philadelphia."

A year later when the young people had become friends she writes:

"1784, July 10.—Sally Drinker and Walter Payne, Billy Sansom and Polly Wells, Jacob Downing and Dolly Payne went to our place at Frankford," and

"1784, July 18.—Walter Payne went to Virginia."

"1785, Dec 26.—First day. This evening Walter Payne took leave of us, intending to set off early to-morrow morning for Virginia, and in a few weeks to embark there for Great Britain."

Of the family life at Scotch Town, Dolly has left us no record, but only the assurance that "the days were full of happiness."

The Marquis de Chastellux, a major-general under Rochambeau, in the Revolutionary Army, who wrote an account of his travels in Virginia in 1780-2, has, however, given us a picture of a country family of this time, and of one not far distant from Scotch Town. He visited the family of General Nelson at Offley, an "unpretentious country place in Hanover county," and says:[49]

"In the absence of the General, who had gone to Williamsburg, his mother and wife received us with all the politeness, ease and cordiality natural to his family. [It being bad weather] the company assembled either in the parlor or saloon, especially the men, from the hour of breakfast to that of bed-time, but the conversation was always agreeable and well supported. If you were desirous of diversifying the scene, there were some good French and English authors at hand.

An excellent breakfast at nine o'clock, a sumptuous dinner at two, tea and punch in the afternoon, and an elegant little supper, divided the day most happily for those whose stomachs were never unprepared."

The Pleasants and Winstons were their neighbors also, but the large estates, in a measure, isolated each family, which thus became a little community in itself, raising all necessary food, manufacturing all clothing and materials for clothing, and even, on the tidewater estates, exporting from their own wharves the great staple, tobacco, for which in return their few luxuries were brought to their very door.

With all his broad acres the Virginia gentleman had no great wealth at his command. It has been estimated that Colonel Byrd, who was perhaps their largest land-owner, was worth but $150,[50]000. Patrick Henry wrote to General Stevens (Stephens) that his father-in-law "owned one hundred and fifty slaves and four or five thousand acres of land, not counting some three thousand in Kentucky," but that from him his son, Captain Alexander Spotswood Dandridge, "could have no great expectations."

The families were large, and the land often had little real value, two dollars an acre being considered a good price. The best land in the near neighborhood of cities brought only from twenty to forty dollars per acre. There is a quaint record preserved in Goochland showing that William Randolph sold to Peter Jefferson (father of Thomas) two hundred acres for the consideration of "Henry Wetherburn's biggest bowl of arrack punch." Henry Wetherburn was the host of the famed Raleigh Tavern at Williamsburg.

The Dandridge Home.

The Dandridge Home.

Of the Revolution the family at Scotch Town saw but little, but its effects they felt; it could not be otherwise with Cornwall's great army stationed so near them. When General Wayne's troops marched through Hanover in June, 1781,[51] Captain John Davis notes in his diary that they "saw few houses, which were mostly situated far back from the roads, and very few people." On the 17th he wrote: "Marched at 3 o'clock through the best country I had seen in this state, twenty miles to Mr. Dandridge's."

De Chastellux says that Mr. Tilghman, the landlord of the Hanover Inn, lamented having had to board and lodge Cornwallis and his retinue without any return. "We set out the next morning at nine," he continued, "after having breakfasted much better than our horses, which had nothing but oats; the country being so destitute of forage that it was impossible to find a truss of hay, or a few leaves of Indian corn, though we sought it for two miles around. Three miles from Hanover we crossed the South Anna on a wooden bridge. On the left side of the river, the ground rises, and you mount a pretty high hill; the country is barren, and we travelled almost always in the woods," arriving at Offley at 1 o'clock.

His description of the country between Williamsburg and Hanover is more pleasing. "The country through which we[52] pass is one of the finest in lower Virginia. There are many well-cultivated estates and handsome houses." "We arrived before sunset and alighted at a tolerable handsome inn; a very large saloon and a covered portico are destined to receive the company who assemble every three months at the Courthouse[14] either on private or public affairs. This asylum is all the more necessary, as there are no other houses in the neighborhood. Travellers make use of these establishments, which are indispensable in a country so thinly inhabited that houses are often at the distance of two of three miles from each other."

Hanover Court House.

Photographed by Samuel M. Brosius.

Hanover Court House.

Photographed by Samuel M. Brosius.

Susan Nelson, a loved friend of Dolly's, lived on New Found River, seven miles off; and he who would know the later history of this neighborhood has but to turn to the writings of her grandson, Thomas [53]Nelson Page, and at once, by the magic of his pen, he will be in "the old country," and its charm will tempt him to linger there and love its people.

Dolly's earliest school-days were spent in an "old field" log school-house near by, but she cared little for books, either then or later, but was a merry, loving little maiden, who was "pleasure-loving, saucy, bewitching." As she grew older, with her brothers Walter, Temple and Isaac, and perhaps the little Lucy, she attended the Quaker school at Cedar Creek meeting-house, near Brackett Post-office, but three miles distant. The meeting-house stood in a forest of pine and cedar that grew to its very doors, while close by ran the "clear, sweet water" of Cedar Creek. The house was an old colonial building, most of the materials for which were brought from England; and it stood on part of that tract of land granted by good King George. It consisted of eight hundred acres lying on both sides of Cedar Creek in St. Paul's parish, and was granted to Thomas Stanley, James Stanley and Thomas Stanley, Jr., for "divers good causes[54] and considerations, but more especially for and in consideration of the importation of sixteen persons to dwell within this our Colony of Virginia." "Witness our trusty and well-beloved Alexander Spottswood, Governor, at Williamsburg, under his seal of our Colony, this 16th day of December, 1714."

A few years ago the old meeting-house was destroyed in a forest fire.

The earlier records of the school have disappeared, but later ones tell that in 1791 Benjamin Bates, Jr.,[15] was teaching [55]reading, writing and English grammar for 30s per annum. But for mathematics a charge of £3 was made. Holidays were not thought so necessary for the welfare of teachers and pupils then, but they were allowed "two days of relaxation" each month, one of which was a "Seventh day" of the week; the other the "monthly meeting day." The long year had but three holidays. Two weeks were given at "Yearly Meeting time," and a half week was allowed for each "Quarterly meeting."

The school, however, was deservedly famous; its teacher was an able man, and scholars came to it from a distance. At this time there were few schools in Virginia.[16] In the long list of patrons are the [56]names of John and Mary Payne, although they had been many years in Philadelphia, (their share was marked as made over to "C. Moorman to pay"); Thomas Pleasants, of Beaver Dam; Robert Pleasants, of Curles; John Lynch, from Lynchburg; Judge Hugh Nelson, and others, all of whom were men of note in their own neighborhoods.

John Lynch and his brother Charles were the founders of Lynchburg. The name of Charles Lynch,[17] has become [57]famous as the originator of "Lynch law," yet it little represents the character of Lynch, who was a "brave pioneer, a righteous judge, a soldier and a statesman." His memory is "by no means deserving of oblivion, still less obloquy." "He was[58] but a simple Quaker gentleman, yet his name has come to stand for organized savagery."

[1] Colonel John Payne was member of House of Burgesses for Goochland 1752-58, 1760-6, 65-66, 1768. Josias Payne was Burgess for Goochland 1761 and 1765. Josias Payne, Jr., was Burgess for Goochland 1769. John Payne was member of the House of Delegates for Goochland 1780.

Payne Arms—"Gu on a fesse betw two lions pass. ar."

Crest—"A lion's gamb couped ar., grasping a broken tilting lance, the spear end pendant gu."

Motto—"Malo mori quam foedari."

[2] 1688, average value of horses was £5 sterling.—Clayton.

Ten or twelve pounds was the value of a very good horse in 1782.—De Chastellux.

[3] It is also a matter of tradition that Anne Fleming was the wife of John Payne. Colonel John Payne's first wife died about the time the following trial took place. The punishment inflicted could scarcely be for a less crime than murder.

Bedford Co., Va., May 24th, 1756.—Court assembled "to hear and determine all Treasons, Petit Treasons, Murders, and other Offences, committed or done by Hampton and Sambo belonging to John Payne of Goochland Gent."

"The said Hampton and Sambo were set to the Bar under Custody of Charles Talbot [then sheriff], to whose Custody they were before committed on Suspicion of their being Guilty of the felonious Prepairing and Administering Poysonous Medicines to Ann Payne and being Arraigned of the Premises pleaded Not Guilty and for their Trial put themselves upon the Court. Whereupon divers Witnesses were charged and they heared in their Defence. On Consideration thereof it is the Opinion of the Court that the said Hampton is guilty in the Manner and Form as in the Indictment. Therefore it is considered that the said Hampton be hanged by the neck till he be dead, and that he be afterward cut in Quarters, and his Quarters hung up at the Cross Roads. And it is the Opinion of the Court that the said Sambo is guilty of a Misdemeanor, Therefore it is considered that the said Sambo be burnt in the Hand, and that he also receive thirty-one Lashes on his bare Back at the Whipping-Post.

"Memo: That the said Hampton is adjudged at forty-five Pounds, which is ordered to be Certified to the Assembly [that his owner may be remunerated according to law]."

Slaves were not tried by jury, but before five justices, and cannot be condemned unless all the justices agree.

On examination, instead of an oath being administered, the black is charged in the following words:

"You are brought hither as witnesses, and by the direction of the law I am to tell you, before you give your evidence, that you must tell the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth; and if it be found hereafter that you tell a lie, and give false testimony in this matter, you must for so doing have both your ears nailed to the pillory and cut off, and receive thirty-nine lashes on your bare back, well laid on at the common whipping-post."

This punishment is administered by nailing one ear to the pillory, where the culprit stands for one hour, when that ear is cut off, and the other nailed, which is in like manner cut off at the expiration of another hour, and after this he receives thirty-nine lashes.—"Historical Register," 1814, page 65.

[4] From John Coles and Mary Winston are descended the Coles family of Philadelphia. His grandson Edward, secretary to President Madison, married Sally Logan Roberts, of Philadelphia, and settled there. Major John Coles was engaged in merchandizing in Richmond; his residence, a frame house recently demolished (1871), was situated on Twenty-second Street, between Broad and Marshall. When torn down, many of the timbers, though more than a century old, were found to be in a perfect state of preservation.

When the floor of old St. John's Church was removed, in 1867, to replace the joists, a metallic plate was found marking the place of burial and bearing the name of Major John Coles, but it was so corroded, it soon fell to pieces.—Vestry Book of Henrico Parish.

John Coles, who lived on Church Hill, owned much land in what is to-day the city of Richmond. He once gave a whole square of the infant city for a fine horse. He also owned large estates in several of the counties.—"Virginia Magazine."

[6] "Virginia Magazine," Vol. VIII, p. 299.

[7] Studley, the home of Mrs. Syme, where Patrick Henry was born, is no longer standing. Its site is marked by a hedge of box and an avenue of aged trees. It was three miles from Hanover and sixteen from Richmond. The family removed to "Retreat" (formerly Mt. Briliant), on South Anna River, near Rocky Mills, twenty-two miles from Richmond. Here most of Patrick Henry's childhood was passed. His mother, riding in a double gig, took him to church with her, and coming home had him repeat the text and recapitulate the sermon. These early exercises served him well in after life. A few miles from "Studley," are the "Slashes of Hanover," the birthplace of Henry Clay.

[8] Governor Dinwiddie introduced Colonel John Henry to his friend John Syme. He was soon at home in his family, and married his widow.

[9] He was lieutenant in the Mexican War, rode horseback to California with the "forty-niners," and was brigadier-general in the Confederate army. He was serving his second term in the United States Senate, and had been re-elected for another term of six years beginning in 1909. At the time of his last election the Alabama Legislature unanimously repealed a law as old as the State to save him the exposure of a long journey in the dead of winter.

[10] Probably both these signatures were written by Mary Payne.

[11] Robert Pleasants was the son of John Pleasants, of Henrico, the clerk of the Upper Quarterly Meeting, who had died in 1771 and freed all his slaves by will, providing for the maintenance of those over forty-five years of age. The laws of Virginia, however, did not permit his heirs to carry out his wishes, and the slaves remained in their possession until 1798, when they finally succeeded in having the freedom of not only the several hundred originally freed, but of their issue, confirmed by a decree of the High Court of Chancery of Virginia.—From Friends' records, Monument Street, Baltimore.

"Robert Pleasants possessed a vigorous intellect, and was a man of indomitable energy." He was engaged in mercantile pursuits and planting, and was remarkably successful. He owned and resided on Curles Plantation.—From Vestry Book of St. John's Church, Richmond.

His book of correspondence with Washington, Jefferson, Madison, Benezet, Pemberton, Henry and many noted men is preserved in Friends' safe, Monument St., Baltimore.

In 1790 Abolition Society founded in Virginia, Robert Pleasants, President. At death freed eighty slaves, in addition to several hundred belonging to father freed during his life time.

[12] On the James River, near Richmond.

[13] Original at Monument Street, Baltimore.

[14] Hanover Court House, 20 miles from Richmond, 102 miles from Washington, is situated several miles from the river.

It has two very large and commodious jails (!!), one tavern, one store, one boot and shoe shop, one blacksmith-shop. It has a population of about 50. One attorney lives there.—"Martin's Gazetteer", 1835.

It has a population of 58 to-day.

Hanover Court House where Patrick Henry figured in early life. Here many of his speeches were delivered. Here he won his first case, "The Parson's Cause."

[15] The same Benjamin Bates who in 1816 as clerk of the Virginia Yearly Meeting drew up and presented to the Burgesses of Virginia a protest against the existing militia laws of the State and accompanied it by an able letter, of which the editor of "Niles' Register," November 30th, says that it perhaps "forms a body of the ablest arguments that have ever appeared in defense of certain principles held by this people."—"Friends' Miscellany," Vol. VII, p. 221; "Niles' Register," VII, p. 90, supplement. William Wirt also pronounced its arguments "unanswerable."

[16] "(1634)" There are no schools or printing to make poor people "dissatisfied." But later there was one free school endowed by a large-hearted man. Virginia up to this time had few schools. In some neighborhoods the planters clubbed together and log school houses were built, but there were more often none at all, the boys being sent North or abroad for their education, while that of the girls was often entirely lacking. An old gazetteer of 1835 makes report for Henrico County, including Richmond, which had been incorporated as a city in 1782, "few or no schools worthy of notice," "that a few good schools have existed," but not a single academical institution. "That in 1803 a charter had been obtained for one to be built by lottery and private subscription, but only the basement was built and the project abandoned."

[17] John and Charles Lynch, sons of Charles and Sarah Clark Lynch, were the founders of Lynchburg, Va. The Clark family were Friends, and, after the father's death, the children, with her became members of Cedar Creek Monthly Meeting. Their father left them the owners of large tracts of land. John, the elder brother, kept the home place, where Lynchburg now stands. In 11th January, 1755, Charles Lynch and Anne Terrill are reported "clear" of other engagements by the meeting at Cedar Creek, and the following day are married and start for what was then a far western home—the undeveloped lands in Bedford County, where the buffalo still roamed and Indians were plentiful.

As soon as his new home at Green Level was finished, he helped to build and organize a Quaker meeting. This was the first public place of worship in that part of Virginia; and when the meeting was broken up by the Indians (it was during the French and Indian War), he removed the congregation to his own house, where his armed negroes could ward off their attacks.

It has been said that it is difficult to overestimate the influence of these Quaker pioneers (of whom Charles Lynch was chief) in establishing better relations with the Indians and fostering a spirit of peace and justice amongst the neighbors. Lynch soon became a leading man, and already in 1763 had great wealth in the form of tobacco, cattle and slaves.

He was asked in 1764 to become a member of the Assembly, but refused as inconsistent with his Quaker principles. But in the excitement of Stamp Act days, when it was difficult to get a proper representative from the West, he saw differently, and in 1764, at the age of 35, was elected to the House of Burgesses, and held his seat until the colony became an independent State.

It was then necessary that he take the oath and—

December, 1767, "Charles Lynch is disowned" for taking "Solemn Oaths" from the little meeting he had fostered and cared for and where his words of "admonition" had been heard. In heart he was not greatly changed, and he raised his children Friends.

When the Revolutionary struggle began he helped raise and enlist troops for home protection. His Quaker principles prevented him from going into the army for a time, but finally "the Court of Bedford" in 1778 "doth recommend to his Excellency the Gov., Chas. Lynch, as a suitable person to exercise the office of Col. of Militia," he saw the need and accepted. At this time in his history occurred the event that has made his name famous—a conspiracy in his home neighborhood that he promptly put down with the help of his troops, and caused to be sentenced and imprisoned its leaders, thereby exceeding his legal powers.

In Richmond, Jefferson, then governor, had fled from the capital, where all was in confusion, and there was much excuse for his action.

With "his Rough Riders of the West" and his son, a lad of 16, he marched against Benedict Arnold and then to North Carolina in time to be present at the battle of Guilford Court House, when he won the commendation of that other Quaker General Nathaniel Greene, who kept him with him until after the surrender of Cornwallis. His services are described by Robert E. Lee in his history of his father's regiment.

At the end of the war he again took his seat in the Assembly, before which he brought up the unlawful action he had taken during the war, and—

The following act was passed by the Virginia Legislature after the Revolution:

"Whereas, divers evil-disposed persons in the year 1780 formed a conspiracy and did actually attempt to levy war against the commonwealth, and it is represented to the present General Assembly that Charles Lynch and other faithful citizens, aided by detachments of volunteers from different parts of the State, did in timely and effectual measures suppress such conspiracy, and whereas the measures taken for that purpose may not be strictly warranted by law, although justifiable from the imminence of the danger, Be it therefore enacted that the said Charles Lynch and all other persons whatsoever concerned in suppressing the said conspiracy or in advising, issuing or exacting any orders or measures taken for that purpose, stand indemnified and exonerated of and from all pains, penalties, prosecutions, actions, suits and damages on account thereof.

And that if any indictment, prosecution, action or suit shall be laid or brought against them or any of them for any act or thing done therein, the defendant or defendants may plead in bar and give this act in evidence."—"Atlantic Monthly" (December, 1901), Thomas Walker Page, and "Friends' Records of Cedar Creek Monthly Meeting."

Three years after their removal to Philadelphia a certificate is issued transferring the membership of "John Payne and Mary, his wife, and their children, William Temple, Dorothy, Isaac, Lucy, Anne, Mary, John and Philadelphia to Pine Street Monthly Meeting." The Paynes settled in what was then the northern part of Philadelphia, and at first John Payne believed his means ample to live in the same hospitable way that had been his wont on the old Virginia plantation, but he soon found his expenses were increased much beyond his expectations, and decided, with the assistance of his sons, to start in business in Philadelphia. For this kind of life, however, his early training had not fitted him, and the business[60] venture was a complete failure. It was followed by his disownment from Pine Street meeting "for failure to pay his debts" (1789), and from this crushing blow the proud spirit of John Payne never recovered, and he died soon after.

It is interesting to know that the store of "John Payne, merchant," was on Fifth Street between Market and Arch, and his residence was 52 Arch Street.

Dolly in the meantime had developed into a charming woman, who entered into all the modest gaieties of the little town, where during the day the daughters of the family, simply dressed, did much of the household work, although even then "some" were so remiss as to "read novels and walk without business abroad."

When the daily tasks were finished the families gathered on the front porch, the girls dressed in plain stuff or chintz frocks with white aprons, and here the passing neighbors stopped to chat awhile or tarry longer. Everybody had a speaking acquaintance, at least, in this little Quaker town.[18]

It was probably in the fall of 1787 that two of Dolly's Virginia friends came to pass the winter in Philadelphia,—Deborah Pleasants,[19] the daughter of Thomas and Elizabeth Pleasants of Beaver Dam, who had been a friend and schoolmate at the old Cedar Creek School; and her cousin Elizabeth Brook,[20] then from Leesburg, Virginia, a Quaker settlement where the smaller plantations of from one hundred to three hundred acres were cultivated entirely by free labor.

The journey from Beaver Dam had been made on horseback, in easy stages, as there were many Friendly homes to stop at on the way, and the days spent in riding through the almost unbroken forests of Virginia pines and the fording of the rivers had been a delightful experience to the two girls, who, with their entire [62]outfit on their saddle pommels, finally drew rein in the quiet neighborhood of Brook Court, where the arrival of their little cavalcade caused an unwonted stir.

A happy winter followed, in which the three girls were much together, but when summer came "Deborah" and "Elizabeth" returned to their southern homes.

The following girlish letter[21] from Dolly Payne to Elizabeth Brook is undated, but must have been written about December, 1788, or later:

How much am I indebted to thee dearest Eliza For throwing off that formality so stifling To the growth of friendship! and addressing First her who feels herself attached to thee by Every sentement of her heart and she often In her "hours of visinary indulgence" calls to Recollection the two lov'd girls who rendered Her so happy during their too short stay in Philadelphia.

I should most gladly have offered you the Tribute of my tender remembrances long before This by the performance of my promise of Wrighting, but my ignorance of a single conveyance[22] was the only preventative.

Let this however, my Dr Betsy obliterate the Idea of my neglect occasion'd by my prospects Of happiness[23] for be assur'd that no sublunary Bliss whatever should have a tendency to make Me forgetful of friends I so highly value.

This place is almost void of anything novell, Such however as is in circulation I will endeavor To Recollect in order to communicate.—Susan Ward and thy old Admirer W. S. have pass'd Their last meeting & are on the point of Marriage. Sally Pleasants and Sam Fox[24] according to the Common saying are made one—Their wedding Was small on account of the death of a cousin, M. Roads. The Bride is now seting up in form For company. I have not been to visit her but Was informed by Joshua Gilpin[25] that he met 40 Their paying their respects, etc., etc.

A general exclamation among the old Friends Against such Parade—a number of other matches

Talked off but their unsertainty must apologize For my not nameing the partys——

A charming little girl of my acquaintance & A Quaker too ran off & was married to a Roman Catholic the other evening—thee may have seen Her, Sally Bartram was her name.

Betsy Wister[26] & Kitty Morris too plain girls Have eloped to effect a union with the choice of Their hearts so thee sees Love is no respecter Of persons——

The very respectful Compliments of Frazier Await the 2 Marylanders—Frazier that unfortunate youth whose heart followed thee captive to Thy home—do call to mind this said conquest Betsy—I see him every day & thee is often the Subject of our Tete-a-tetes—he says the darn in Thy apron first struck him & declares that he Would give any mony for that captivating badge Of thy industry.

After bloting my paper all ore with nonsense I must conclude with particular Love to Debby Pleasants when thee should see her & respects

To her brother James—write often & much to Thy affectionate

D Payne

Addressed to—

Eliza Brooke Junr:

Montgomery County

Maryland

Pr Favour of }

Capt Lynn }

A later letter to Elizabeth Brooke[27] (from Sarah Parker) gives further news of Dolly Payne. After referring to rumors current regarding the approaching marriage of her friend she continues:

"It may be an encouragement, probably, should I inform thee of some old acquaintances jogging on in this antiquated Custom. Dolly Payne is likely to unite herself to a young man named J. Todd, who has been so solicitous to gain her favor many years, but disappointment for some time seem'd to assail his most sanguine expectations, however things have terminated agreeable to his desires & she now offers her hand to a person whose heart she had long been near and dear to—he has proved a constant Lover indeed & deserves the highest commendation for his generous behavior, as he plainly shows to the world no mercenary motives bias'd his judgment (on the contrary) a sincere attachment to her person was his first consideration else her Father's misfortunes might have been an excuse for his leaving her—they pass'd meeting[28] fourth day, was the same day George Fox[29] & Molly C. Pemberton were united, rather an uncommon instance, but their marriage was postponed on account of a relation's death.

"Pine Street meeting house was amazingly crowded, a number of gay folks—I heard a young man say he was surprised on viewing the galleries, as they had more the appearance of a play house than of Friends' meeting. There were great affronts given, I am told, when Dolly retired in the other room to pass by Nicholas Waln, rising and saying 'it was not customary for those that do not belong, unless near connections, to go into meetings of business'—but some were so rude as to press in without any kind of ceremony, very indecent behavior was too obvious to be unobserved, even by children."[30]

Pine Street Meeting-House.

Pine Street Meeting-House.The "passing of meeting" was then a formidable proceeding. The intended groom, with a friend from the men's meeting, entered the women's side after the closing of the partitions, and taking the intended bride on his arm announced, first in one meeting and then in the other, that "we propose taking each other in marriage."

Many anecdotes are related of Nicholas Waln, who was a leading member of Pine Street meeting, and had been one of the shrewdest and wittiest lawyers of the Philadelphia bar. His words were very apt to hit the mark.

A month later, on Dolly's wedding day, at the head of the meeting (at Pine street) sat James Pemberton[31], "erect and [68]immovable, with his crossed hands resting on his gold-headed cane"; beside him "Nicholas Waln with his smile of sunshine," "Arthur Howell[32], with hat drawn low over his face," and "William Savery of the solemn silvery voice," and other ministers and elders of the meeting. The body of the meeting was composed of the solid Quaker element of the city, and the "gay folks" again crowded the galleries to their utmost capacity. After a short silence Dolly Payne and John Todd arose, and each repeated the solemn marriage ceremony of the Friends, each [69]signed the marriage certificate, and "John Todd of the city of Philadelphia, attorney-at-law, son of John Todd, of this city, and Mary his wife, and Dolly Payne, daughter of John Payne of the city aforesaid, and Mary his wife," were married, 1st mo. 7th, 1790.

MARRIAGE CERTIFICATE OF JOHN TODD AND DOLLY PAYNE.

Whereas John Todd of the city of Philadelphia in Pennsylvania, attorney at law, son of John Todd of said city and Mary his wife, and Dolly Payne daughter of John Payne of the city aforesaid and Mary his wife having declared their intentions of marriage with each other before several Monthly Meetings of the people called Quakers held in Philadelphia aforesaid for the Southern District according to the good order used among them, and having consent of parents, their said proposals were allowed of by the said meeting. Now these are to certify whom it may concern that for the full accomplishing their said intentions this seventh day of the first month in the year of our Lord one thousand seven hundred and ninety, they the said John Todd and Dolly Payne appeared in a public meeting of the said people held at their meeting house in Philadelphia aforesaid and the said John Todd taking the said Dolly Payne by the hand did in a solemn manner openly declare that he took her the said Dolly Payne to be his wife, promising with Divine assistance to be unto her a loving and faithful husband until death should separate them. And[70] then in the same assembly the said Dolly Payne did in like manner declare that she took him the said John Todd to be her husband, promising with Divine assistance to be unto him a loving and faithful wife until death should separate them. And moreover they the said John Todd and Dolly Payne (she according to the custom of marriage assuming the name of her husband) did as a further confirmation thereof then and there to these presents set their hands. And we whose names are hereunto also subscribed being present at the solemnization of the said marriage and subscription have as witnesses thereof, set our hands the day and year above written.

NAMES OF THOSE SIGNING THE MARRIAGE CERTIFICATE OF DOROTHY PAYNE & JOHN TODD

Edward Tilghman,

James Ash,

Owen Jones,

John Pemberton,

Thomas Clifford,

James Pemberton,

Samuel Pleasants,

Caleb Foulke,

William Savery,

James Cresson,

James Logan,

Benedt. Dorsey,

Samuel Clark,

John Parrish,

Thos. Harrison,

John Payne,

Mary Payne,

John Todd,

Mary Todd,

James Todd,

Alice Todd,

Lucy Payne,

Anna Payne,

Mary Payne,

Betsy Blau,

Thos. Poultney,

Stephen Burrows,

Mary Burrowes,

Sarah Waln,

Esther Fisher,

Saml. Coates,[71]

Arthur Howell,

John Elliott, Jr.,

Thos. Follet,

Caleb Atmore,

John Poultney,

Caspar W. Morris,

Zaccheus Collins,

Henry S. Drinker,

Chas. West, Jr.,

John Biddle,

Elijah Conrad,

Ebenezer Breed,

John E. Cresson,

Richard Johnson,

Geo. Roberts,

Benj. Chamberlain,

Abigail Drinker,

Maria Hodgdon,

Kitty Doughten,

Benjamin Morgan, Jr.,

Caleb Carmalt,

James Bringhurst,

Anthony Morris,

Griffith Evans,

Isaac Bartram,

Anna P. Pleasants,

Israel Pleasants,

Samuel Emlen, Jr.,

Nicholas Waln,

Samuel Emlen,

Owen Biddle,

Samuel Shaw,

Eliza Collins,

Anna Drinker,

Mary S. Pemberton,

Sarah Biddle,

Mary Shaw,

Abigail Parrish,

Susanna Jones,

Phebe Pemberton,

Sarah Parrish,

Mary Pleasants,

Elizabeth Dawson,

Mary Eddy,

Ann Marshall,

Sarah Ann Marshall,

Mary Drinker, Jr.,

Eliz. P. Dilworth

The short but happy married life of Dorothy Payne Todd was spent at 51 South Fourth street,[33] now Fourth and [72]Walnut streets, and here her sons, John Payne and William Temple Todd, were born.[34]

In 1793 that dread disease, the yellow fever,[35] raged in Philadelphia, and John Todd hastened to send his wife to a place of safety. She and her infant son, William Temple, three weeks old, were carried in a litter to Gray's Ferry, then well beyond the city's limits. John Todd himself returned to the city. His parents were first taken, and he, feeling himself stricken, hastened to Gray's Ferry for one last glance at his beloved wife. Dolly, in spite of his remonstrances, threw herself into his arms and pressed her lips to his. After days of unconsciousness she slowly recovered to find her husband and her infant son no more.

John Todd, Sr., left a will. To his son John he willed £500 and his watch; and to each of his grandsons, Payne and William Temple, he left £50.

John Todd, Jr.,[36] died October 24, 1793. To his wife he left the settlement of his "very small estate." His will had been made some time before his death, and said:

I give and devise all my estate, real and personal, to the Dear Wife of my Bosom, and first and only Woman upon whom my all and only affections were placed, Dolly Payne Todd, her heirs and assigns forever, trusting that as she proved an amiable and affectionate wife to her John she may prove an affectionate mother to my little Payne, and the sweet Babe with which she is now enceinte. My last prayer is may she educate him in the ways of Honesty, tho' he may be obliged to beg his Bread, remembering that will be better to him than a name and riches.—I appoint my dear wife executrix of this my will.

Inventory and Appraisement of the Goods & Chattels &c. late the property of John Todd, Jr.[37]

| Viz:— | £ | s | d |

| One large Side Board | 9 | 00 | 00 |

| One Settee | 10 | 00 | 00 |

| Eleven Mahogany & Pine tables | 17 | 17 | 06 |

| Three Looking Glasses | 14 | 00 | 00 |

| Thirty-six Mahogany and Windsor chairs | 27 | 12 | 06 |

| One Case of knives & forks | 5 | 00 | 00 |

| And-Irons, Shovel & Tongs | 9 | 02 | 06 |

| Window curtains & Window blinds | 12 | 00 | 00 |

| Carpets & Floor Cloaths | 11 | 15 | 00 |

| Bed, Bedstead & Bed Cloath | 30 | 00 | 00 |

| Sundry Setts of China &c. | 9 | 00 | 00 |

| Articles of Glass Ware & Waiters etc. | 9 | 07 | 06 |

| Glass lamp, pr Scones & six pictures | 3 | 17 | 06 |

| Sundry Articles of Plate & Plated ware—also Sett of Castors | 14 | 07 | 06 |

| Sundry Kitchen furniture | 12 | 10 | 00 |

| Desk & Book case | 5 | 00 | 00 |

| An open stove | 2 | 05 | 00 |

| Two Watches | 9 | 15 | 00 |

| One fowling piece | 3 | 00 | 00 |

| One Horse & Chair | 40 | 00 | 00 |

| Library | 187 | 15 | 00 |

| —— | — | — | |

| 434 | 05 | 00 | |

| Appraised Seventh day of Dec. 1793. |

The estate of John Todd was more ample than his modest statements would[75] indicate. He left his wife that commodious dwelling of English red and black brick still standing at the corner of Fourth and Walnut streets, with stable on the grounds. The inventory of his effects shows that the house was well furnished. His library, too, was a good one, and with her "horse and chair" Dolly found herself more than comfortably provided for.

The moving of the national capital to Philadelphia had crowded the city to its utmost capacity, and homes were hard to find. Mary Payne had opened her doors,[38] and Aaron Burr, then Congressman, was fortunate to find boarding there.

Dolly was soon drawn into society, and her brilliant beauty and charming manners drew many admirers. James Madison requested to be introduced, and Dolly wrote her friend, Elizabeth Lee: "Thou must come to me, for Aaron Burr[39] is [76]going to bring the great little Madison to see me this evening." Dolly wore her mulberry-colored satin, and appeared a vision of beauty to him; and it was not his only visit. But it was the "first lady of the land" who finally brought things to a crisis. She sent for Dolly and asked, "What is this I hear about Madison and Mistress Todd?" and, when Dolly hid her blushing face, took her into her arms, and told her that she and "the President" approved, and wished to see her again happily married; "and Madison will make thee a good husband," she said.

In the summer of 1793 Lucy Payne had become the girlish bride of George Steptoe Washington,[40] the nephew and [77]ward of the President. She was but fi[78] [79] [80]fteen and he seventeen years old at the time, and they were now living at Harewood[41], near Harper's Ferry. "Harewood of pleasant memory and patriotic association," as an old writer has lovingly said. It was built on part of the Washington tract of land in 1756, by Colonel Samuel Washington, under the supervision of his brother George, and an old record states that for the hauling of the gray limestone of which it is built, from a nearby quarry, they paid one Shirley Smith "an acre of ground per team per day". The finer part of the woodwork, the pilasters, wainscoting and cornice, were all brought from "Old England" to Alexandria, and [81]thence carted to Harewood, a long and toilsome journey.

Harewood from the garden.

Harewood from the garden.

Now the fair young mistress of Harewood begged that her sister should be married there, and so it was decided. Thomas Jefferson offered his coach for the journey, and taking her sister Anna, the little Payne and a maid, Dolly journeyed to that historic home, accompanied by Madison and mutual friends, riding and driving.

A week of the early fall time had been whiled away when they reached their journey's end, where great preparations were already being made for the festive occasion, for this was to be a "gay" wedding. Guests came from far and near. Francis Madison was there, and Harriet[42] Washington, and at the last moment "Light-Horse Harry Lee" came dashing up on "the very finest horse in all Virginia."[82]

And then in the handsome wainscoted parlor, James Madison and the winsome "Widow Todd" were married, September 15, 1794, by Dr. Balmaine, of Winchester, Va., a relative of James Madison.

Madison's present to his bride was a wondrous necklace of Byzantine mosaic[43] work, of temples and tombs and bridges, eleven pictures in all joined by delicate chains.

After much feasting and merry-making, in which the groom lost his ruffles of Mechlin lace, which were parted amongst the girlish guests as souvenirs, the bride and groom made their escape and drove away for the honeymoon.

Little record of the wedding is left, and there is no list of the guests present, as at that earlier and more stately, though unpretentious, wedding in the old Pine street meeting-house.

The Parlor, Harewood.

(In which James and Dolly Madison were married.)

The Parlor, Harewood.

(In which James and Dolly Madison were married.)

The following letter from Madison to his father describes the wedding journey:

Dear & Honord Sir: