The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Teaching of Art Related to the Home, by

Federal Board for Vocational Education

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net

Title: The Teaching of Art Related to the Home

Suggestions for content and method in related art

instruction in the vocational program in home economics

Author: Federal Board for Vocational Education

Release Date: June 23, 2011 [EBook #36498]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK TEACHING OF ART RELATED TO HOME ***

Produced by Juliet Sutherland, David Garcia and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

BULLETIN No. 156

Home Economics Series No. 13

THE TEACHING

OF ART RELATED TO THE HOME

SUGGESTIONS FOR CONTENT AND METHOD

IN RELATED ART INSTRUCTION

IN THE VOCATIONAL PROGRAM

IN HOME ECONOMICS

JUNE, 1931

Issued by the Federal Board for Vocational Education—Washington, D. C.

[i]

THE TEACHING

OF ART RELATED TO THE HOME

SUGGESTIONS FOR CONTENT AND METHOD

IN RELATED ART INSTRUCTION

IN THE VOCATIONAL PROGRAM

IN HOME ECONOMICS

JUNE, 1931

UNITED STATES

GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE

WASHINGTON: 1931

For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, Washington, D. C. Price 20 cents

[ii]

[iii]

FEDERAL BOARD FOR VOCATIONAL EDUCATION

MEMBERS

William N. Doak, Chairman

Secretary of Labor

-

Robert P. Lamont,

Secretary of Commerce.

-

Edward T. Franks, Vice Chairman,

Manufacture and Commerce.

-

Arthur M. Hyde,

Secretary of Agriculture.

-

Perry W. Reeves,

Labor.

-

Wm. John Cooper,

Commissioner of Education.

-

Claude M. Henry,

Agriculture.

John S. Shaw, Secretary and Chief Clerk

EXECUTIVE STAFF

J. C. Wright, Director

Charles R. Allen, Educational Consultant

John Cummings, Chief, Statistical and Research Service

VOCATIONAL EDUCATION DIVISION

-

C. H. Lane, Chief,

Agricultural Education Service.

-

Frank Cushman, Chief,

Trade and Industrial Education Service.

-

Adelaide S. Baylor, Chief,

Home Economics Education Service.

-

Earl W. Barnhart, Chief,

Commercial Education Service.

VOCATIONAL REHABILITATION DIVISION

John Aubel Kratz, Chief,

Vocational Rehabilitation Service

[iv]

[v]

CONTENTS

| Page |

| Foreword | vii

|

| Section I. Introduction | 1

|

| Section II. Purpose of the bulletin | 4

|

| Section III. Determining content for a course in art related to the home | 10

|

| | Place of art in the vocational program in home economics | 10

|

| | Objectives for the teaching of art | 12

|

| | Essential art content | 14

|

| | Home situations for which art is needed | 17

|

| Section IV. Suggestive teaching methods in art related to the home | 22

|

| | Creating interest | 22

|

| | Discussion of method in the teaching of art | 29

|

| | Suggested procedure for developing an ability to use a principle of

proportion for attaining beauty | 34

|

| | Suggested plan for the development of an understanding of the

principle of proportion and its use | 34

|

| | Details of lesson procedure | 35

|

| | Series of suggested problems to test pupils' ability to recognize

and use the principle of proportion just developed | 38

|

| | Further suggestions for problems, illustrative materials, and assignments | 40

|

| | Class projects | 42

|

| | Notebooks | 43

|

| | The place of laboratory problems | 46

|

| | Field trips | 53

|

| | Measuring results | 55

|

| | Evidences of the successful functioning of art in the classroom | 55

|

| | Evidences of the successful functioning of art in the home | 58

|

| | Home projects | 66

|

| | Suggestive home projects in which art is an important factor | 68

|

| Section V. Additional units in art related specifically to

house furnishing and clothing selection | 72

|

| Section VI. Illustrative material | 75

|

| | Purpose | 75

|

| | Selection and sources | 75

|

| | Use | 77

|

| | Care and storage | 79

|

| Section VII. Reference material | 81

|

| | Use of reference material | 81

|

| | Sources of reference material | 81

|

| | Bibliography | 82

|

| Index | 85

|

[vi]

FIGURES |

| Page |

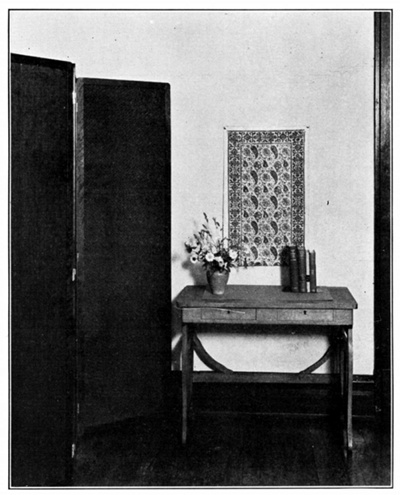

| 1. |

An arrangement of wild flowers and grasses and a few books placed

on a blotter on a typewriter table in front of an inexpensive

india print may furnish a colorful spot in any schoolroom. Note

the effective use of the screen in concealing a filing case |

7

|

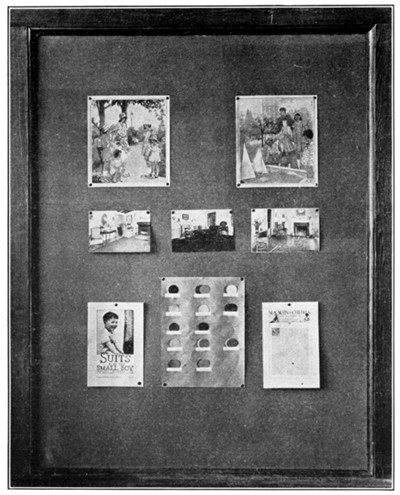

| 2. |

A bulletin board on which it is necessary to use a variety of

materials adds to the appearance of the room when these materials

are well arranged and frequently changed |

8

|

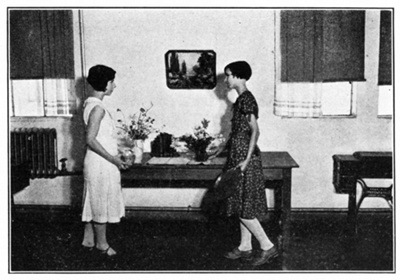

| 3. |

Pupils in a Nebraska high school try out different flowers and arrangements |

9

|

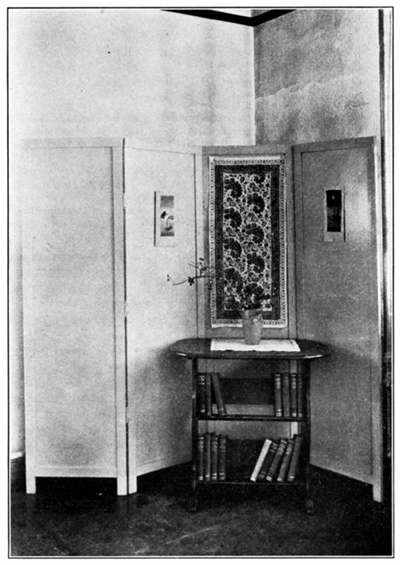

| 4. |

In a Nebraska high school a screen was used in an unattractive

corner as a background for an appreciation center |

24

|

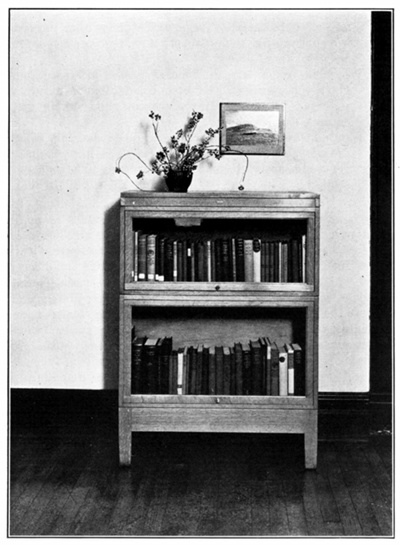

| 5. |

The simplest school furnishings can be combined attractively.

A low bookcase, a bowl of bittersweet, and a passe partout

picture as here used are available in most schools |

26

|

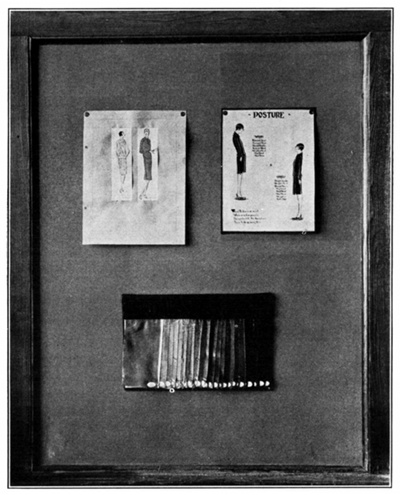

| 6. |

A few pieces of unrelated illustrative material may be grouped

successfully in bulletin-board space |

28

|

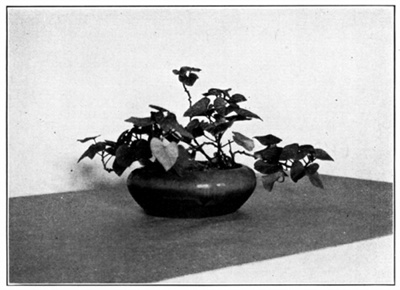

| 7. |

Sprouted sweetpotato produced this attractive centerpiece for the home table |

29

|

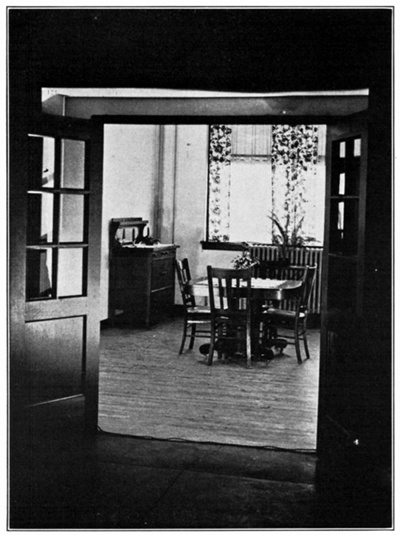

| 8. |

Glass-paneled doors open from the dining room directly into a

main first-floor corridor in the high school at Stromsburg, Nebr. |

30

|

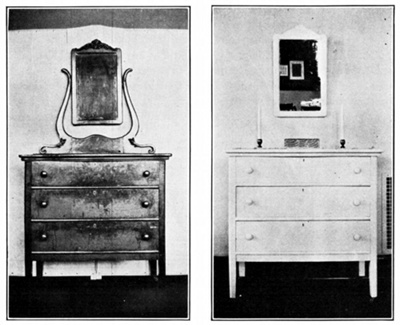

| 9. |

The dresser as found in the dormitory room |

43

|

| 10. |

The same dresser after the class in related art had remodeled and painted it |

43

|

CHARTS |

| 1. |

Suggestions for use of this bulletin by teachers | 5

|

| 2. |

Analysis of the value of notebooks in art courses | 44

|

| 3. |

Types and sources of illustrative materials | 76

|

|

| Publications of the Federal Board for Vocational Education relating

to home-economics education | 89

|

[vii]

FOREWORD

Since the organization of the vocational program in 1917 the teaching

of art in its relation to the home has been recognized as an essential

part of the home-economics program.

Great difficulties have been experienced in securing adequate

instruction in this field. Many schools, especially in the rural

communities, employ no art teachers. In such schools the only art

instruction is that given by the regular home-economics teacher, and

is commonly reduced to a minimum of applicable content.

The teaching of art has dealt too exclusively with the creation of

artistic things, and it is not easy to change the emphasis over into

the field of appreciation and discriminating selection.

Clothing, home planning and furnishing, care of the sick, serving of

foods, care of children, and family relationships, all have an "art"

side. The successful discharge of household responsibilities is

conditioned largely upon a perception of this truth.

There has been a dearth of teachers prepared to teach art in its

application to homemaking. In the last decade, however, several of

the institutions approved for training vocational teachers of home

economics have introduced courses in this field, and the number of

such institutions is increasing.

This bulletin was prepared under the direction of Adelaide S. Baylor,

chief of the home economics education service, by Florence Fallgatter,

Federal agent for home economics in the central region, assisted by

Elsie Wilson, a member of the home economics teacher-training staff of

Iowa State College.

The Federal Board for Vocational Education and Home Economics Education

Service appreciate the cooperation of State supervisors, members of

teacher-training staffs, vocational teachers, and art teachers both in

the schools and colleges, and their contributions of material for this

study.

It has been undertaken to meet a demand expressed very generally during

the last 14 years by teaching staffs for assistance in adapting art

instruction specifically to homemaking, to the end that all instruction

for homemaking may be made more effective.

J. C. Wright, Director.

[viii]

[1]

THE TEACHING OF ART RELATED TO THE HOME

Section I

INTRODUCTION

All art is life made more living, more vital than the average man

lives it—hence its power. Taste, unlike genius can be acquired;

and its acquisition enriches personality perhaps more than any

other quality.—E. Drew.

Professor Whitford 1 bases his book, An Introduction to Art, on two

hypotheses: "(1) That art is an essential factor in twentieth century

civilization and that it plays an important and vital part in the

everyday life of people; (2) that the public school presents the best

opportunity for conveying the beneficial influence of art to the

individuals, the homes, and the environment of the people."

In keeping with this present-day philosophy, the introduction of

art instruction into the public schools is increasing. Through the

influence of home economics, a field of education in which there is

an urgent need and wide opportunity for practical application of the

fundamental principles of art, art instruction is finding its way

into many of the small schools as a definite part of the vocational

programs. Whitford 2 refers to this present-day trend in home

economics as follows:

At first there was very little articulation between the courses

in art and the courses in industrial art or household art. At the

present time we realize that these courses are all related, and

all work together through correlation and interrelation to supply

the child with those worth while educational values which aid in

meeting social, vocational, and leisure-time needs of life.

Not until all girls in the public schools can have their inherent love

for beauty rightly stimulated and directed may we look forward to a

nation of homes tastily furnished and artistically satisfying or of

people who express real genuineness and sincerity in their living.

With the inception of the vocational program in home making through the

passage of the Smith-Hughes Act by Congress in 1917, art was recognized

as one of the essential related subjects. Thus, in the majority of the

schools that have organized vocational homemaking programs, art has

been included as a part of these programs

[2]

and an effort has been made

to apply the principles of art to those problems in everyday life in

which beauty and utility are factors. The aim has been to develop in

girls not only an understanding of these principles but also an ability

to use them intelligently in solving many of their daily problems.

Therefore the teaching of art in home economics courses is primarily

concerned with problems of selection and arrangement. The girl as a

prospective home maker needs to know not so much how to make a pattern

but how to choose one well; not how to make a textile print but how

to select and use it; not how to design furniture but how to select

and arrange it; not how to make pottery but how to select the right

vase or bowl for flowers. At the same time, teachers of related

art in vocational schools have endeavored to show that true art is

founded upon comfort, utility, convenience, and true expression of

personalities as well as upon the most perfect application of art

principles. Considerable emphasis has been given, therefore, to a

consideration and utilization of those material things that afford

opportunity for self-expression. The importance of such self-expression

is stressed in the following words by Clark B. Kelsey: 3

The home expresses the personalities of its occupants and reveals

far more than many realize. It stamps them as possessing taste or

lacking it. Thinking men and women want backgrounds that interpret

them to their friends, and they prefer that the interpretation

be worthy. They also want them correct for their own personal

satisfaction.

In art courses that are related to the home, an attempt is made to

build up in girls ideals of finding and creating beauty in their

surroundings and to bring them to the point where they can recognize

fitness and purpose and see beauty and derive pleasure from inexpensive

and unadorned things that are available to all homes.

Mr. Cyrus W. Knouff 4 has well expressed something of the importance

of such a practical type of art training as follows:

Show the people through their children that one may dress better

on fifty dollars, understanding art principles, than on five

hundred dollars not understanding symmetry, design, color, harmony,

and proportion. With this knowledge you furnish a lovelier home

on five hundred dollars than on five thousand without it. Get your

art away from the studio into life. Teach your children the gospel

of beauty and good taste in their letter writing, their picture

hangings, their clothes, everything they do.

Since the vocational program also provides class instruction for women

who have entered upon the pursuit of home making, as well as for girls

of school age, there has been some opportunity to extend art training

to these women through adult classes. An attempt has been made in

classes in art related to the home, home furnishing, and

[3]

in clothing

classes to give a training which will help them to better appreciate

the influence upon family life of attractive and comfortable homes, of

careful selection and arrangement of home furnishings, and of

intelligent purchasing and selection of clothing.

For the girls who have dropped out of school and have entered upon

employment, part-time classes have been organized under the vocational

program. To these the girls may come for a definite period each week to

secure such instruction as will further extend their general education,

better prepare them for their present work, and also improve their

home life. To the extent that the employed girl improves her personal

appearance, makes her living quarters more attractive, and enjoys the

finer things of life she is more valuable to her employer and is an

asset to society. Much has been accomplished in this direction but

there is a large opportunity in most of the States for more definite

attention to such needs of the employed girl.

[4]

Section II

PURPOSE OF THE BULLETIN

The aim of related art education is to develop appreciation and

character through attempting to surround one's self with things that

are honest and consistent as well as beautiful.—Goldstein.

The vocational programs in homemaking are designed for girls over 14

years of age in the full-time day schools, many of whom do not complete

high school or do not have opportunity for more than a high-school

education; for those young girls, 14 to 18 years of age, who having

dropped out of full-time school can attend the part-time schools;

and for women who are in position to attend adult homemaking classes.

The provision of time in the programs for related subjects as well as

for home-economics subjects covered in these three types of schools

has made it possible to develop the principles of art and science

as more than abstract theories. In this way these principles become

fundamental to the most successful solving of many of the problems in

home economics. The fact that these principles may be applied repeatedly

in many different home-life situations means in turn a very much better

understanding and subsequent use of them.

Through the comparatively few years in which these vocational programs

have been in operation, teachers in all States have attempted with some

success to give an art training that is both practical and vital to

young girls and women. They have, however, been confronted with many

baffling problems. Some of these have been considered by committees

on related subjects and an urgent request was made by one of these

committees that a more detailed discussion of these problems be

published. It is the purpose of the bulletin to point out some of

the most significant problems in connection with art courses that are

related to the work in homemaking and to present the pooled thinking

of various groups upon them to the end that girls and women may know

how to make their homes attractive even with limited incomes and how

to choose and wear clothing effectively and becomingly. Some of the

questions to be answered in an attempt to solve these problems are:

[5]

1. What should be the place of art in the homemaking

program?

2. What are pupils' greatest art needs?

3. What classroom training will help meet these needs?

4. What are the best methods to use in teaching art?

5. To what extent will laboratory problems function

in meeting pupils' needs?

6. What results should be expected from art training

in the homemaking program?

7. How can these results be measured?

In vocational programs the courses or units in art related to the home

are taught by both art teachers and home-economics teachers. In the

larger schools they are frequently assigned to the regular art teacher,

provided she has had sufficient contact and experience in homemaking

to give her the necessary background for making the fundamental

applications. In this case she follows very closely the work in the

homemaking classes and makes use of every opportunity for correlation

of her art work with the home.

In the smaller schools in which the vocational programs are

organized there is usually no special art teacher and therefore the

home-economics teacher must give all of the art work. In most States

training in art is included among the qualifications for vocational

home-economics teachers. The teacher-training institutions are

providing instruction in art and also special methods courses in

the teaching of related art in public schools in order that their

prospective teachers may be as well prepared as possible to handle

the related art as well as the home-economics courses.

This bulletin is intended as a help to teachers of related art courses,

be they regular art teachers or home-economics teachers, to art

instructors and teacher trainers in colleges, and to supervisors of

home economics. The following tabulated suggestions indicate how it may

be of service to these four groups:

Chart 1.—Suggestions for use of this bulletin by teachers

| Groups |

Uses |

|---|

|

I. Art and home economics teachers in vocational schools. |

1. As a guide in determining objectives in related art.

2. As a help in selecting content.

3. As a means of determining method.

4. As suggestive of ways for evaluating results.

5. As suggestive in the selection and use of illustrative materials.

6. As a guide for reference material.

|

|

II. Art instructors in colleges. |

1. As a means of becoming familiar with some of the

typical problems which prospective teachers of

related art will meet.

2. As a guide in selecting those phases of art for

college courses which will enable the prospective

teacher of art to solve many of her teaching problems.

|

|

[6]

III. Teacher trainers. |

1. As an index to the interests and needs of girls in home-economics classes.

2. As a means of determining the phases of art that most nearly meet the needs of girls.

3. As suggestive of methods for student teaching in classes in art related to the home.

4. As a basis for guiding student teachers in collecting and preparing illustrative material.

5. As a guide for reference material.

|

|

IV. Home economics supervisors, State and local. |

1. As a stimulus to promote more courses or units in art.

2. As a stimulus to work for better programs in related art.

3. As a guide in developing art units with teachers through individual,

district, and State conferences.

4. As a basis for giving assistance to teachers on art problems.

|

|

|---|

While the major emphasis in the bulletin is directed toward the

teaching of related art, mention should be made of the importance

of environment as a potent factor in shaping ideals and developing

appreciation of the beautiful. Constant association with things of

artistic quality and frequent opportunity for directed observation

of good design and color should be provided for all home-economics

students. The home-economics laboratory offers an opportunity for

centers in which interesting and artistic groupings may be arranged.

These tend to eliminate much of the formal school atmosphere and

provide a more typical home environment. Such centers in home-economics

laboratories have been appropriately called appreciation centers.

A laboratory with examples of the beautiful in line and color, such

as well-arranged bowls of flowers, bulletin boards, wall hangings,

or book corners, may prove an effective though silent teacher.

It would be futile to attempt to make most school laboratories too much

like homes, however. Such attempts may give the appearance of being

overdone. The light and cheerful room, with the required furnishings

well arranged and one or more appreciation centers, is usually the

more restful and attractive. From daily contact with this type of room

girls unconsciously develop an appreciation of appropriateness and of

orderliness and an ideal for reproducing interesting arrangements in

their own homes. It is desirable to have the appreciation centers

changed frequently, and to give pupils an opportunity to share in

selecting and making the arrangements.

[7]

[8]

[9]

[10]

Section III

DETERMINING CONTENT FOR A COURSE IN ART RELATED TO THE HOME

Taste develops gradually through the making of choices with

reference to some ideal.—Henry Turner Bailey.

PLACE OF ART IN THE VOCATIONAL PROGRAM IN HOME ECONOMICS

In recent years, many schools carrying the vocational program in home

economics have scheduled courses in related art five to seven periods

each week for one semester and in some cases for an entire year. In

other schools, the entire vocational half day has been devoted to home

economics, art being introduced in short units or as a part of some

unit in home economics where it seemed to meet particular needs.

A unit of several weeks or a full semester of consecutive time devoted

to the teaching of art as related to the home is generally considered

more effective than to teach only certain art facts and principles

as they are needed in the regular home economics units. Since art

is recognized as fundamental to the solving of so many homemaking

problems, it seems desirable to provide for this training as early in

the first year of the home-economics program as possible so that it may

contribute to the instruction in the first unit in clothing and home

furnishing.

Prior to selecting the pattern and material for a dress, the girl

needs to understand certain principles of design and color which will

enable her to choose wisely. If art training has not preceded this

problem in the clothing course, or if there is no provision for art

work to parallel the clothing instruction unit, it becomes necessary to

introduce some art training at this point. A similar situation arises

in connection with the other units involving selection and arrangement

such as home furnishing or table service. If art is taught only to

solve specific problems as they arise the pupil will not have an

opportunity to apply it to other phases of home-economics instruction

and will therefore fail to develop the ability to understand and use

the principles of art effectively in solving her other problems. There

is the further danger that the girl's interest in home economics will

be destroyed by interrupting the home-making instruction to teach the

art needed for each unit. For example, if the girl is planning to

[11]

make a dress, her interest and efforts are centered on its production.

If preliminary to starting the dress, time must be taken to establish

standards for the selection of the pattern and materials, the process

of making is prolonged and the girl's interest in the art lessons and

in the later construction of the dress is only half-hearted.

Training which provides for many applications of the art principles as

they are developed gives the girl an ability to use these principles in

solving the problems which arise at other times in home-making units.

It is preferable therefore to arrange the vocational program so that

the art instruction parallels or precedes those units in homemaking in

which there is particular need for art. However, if the program can

not include the teaching of art as a consecutive unit paralleling or

preceding certain units in homemaking, it will be far better for the

home-economics teacher to include art training as it is needed in

the homemaking work than to omit it or attempt to proceed without the

basic fundamental information necessary for the successful solution of

many problems in home economics. In such a plan, time and opportunity

should be definitely provided later in the homemaking program to

summarize and unify the art training that has been given at various

times in order that it may function in the lives of the pupils to a

larger extent than that of solving only the immediate problems for

which it was introduced. Such a summarization will make possible the

application of the essential principles of art to a wide variety of

situations and will mean not only a more thorough understanding of

these principles but a more permanent ability to use them in achieving

beauty and satisfaction in environment.

There are then three possible plans for including art instruction in

the vocational program in homemaking, namely:

1. By presenting the course in art related to the home as a separate

semester or year course that parallels the homemaking course. When

it is a semester course, it is well to offer art the first half of

the year in order that it may be of greatest value to the first

units in clothing.

2. By giving the course in art related to the home as a separate unit

in the homemaking course. Such an art unit should precede that

homemaking unit in which there is greatest need as well as opportunity

for many applications of the principles of art which are being

developed. This will usually be the unit in clothing or home

furnishing.

3. By giving short series of art lessons as needs arise in the homemaking

course. Certain dangers have been pointed out in this plan. If used,

it should include a definite time for unifying and summarizing the

art work at the end of the course.

[12]

OBJECTIVES FOR THE TEACHING OF ART

In the vocational program in which the teaching is specifically designed

to train for homemaking, it is obvious that the major objective in the

related art units should be to train for the consumption of art objects

rather than for their production. Bobbitt 5 elaborates on this objective

as follows:

* * * the curriculum maker will discern that the men and women

of the community dwell within the midst of innumerable art forms.

Our garments, articles of furniture, lamps, clocks, book covers,

automobiles, the exterior and interior of our houses, even the

billboards by the roadside are shaped and colored to comply in

some degree, small or large, with the principles of aesthetic

design. Even the most utilitarian things are shaped and painted

so as to please the eye. * * *

It would seem then that individuals should be sensitive to and

appreciative of the better forms of art in the things of their

environment. As consumers they should be prepared to choose things

of good design and reject those of poor design: and thus gradually

create through their choices a world in which beauty prevails and

ugliness is reduced to a minimum.

This does not require skill in drawing or in other form of visual

art. It calls rather for sensitiveness of appreciation and powers

of judgment. * * * The major objectives must be the ability to choose

and use those things which embody the higher and better art motives.

Education is to aim at power to judge the relative aesthetic

qualities of different forms, designs, tones, and colors. Skill in

drawing and design does not find a place as one of the objectives.

The type of furnishing and decorating products consumed in the home as

well as the type of clothing purchased for the family depends upon the

understanding and appreciation which the home makers have developed for

good art qualities. This in turn is dependent upon training. As one

writer points out 6—

* * * one's capacity richly to enjoy life is dependent upon one's

capacity fully to understand and participate in the things which

make up life interests. In art this is particularly true, for we

can only enjoy and appreciate that which we are able to understand.

Through training we may be able to appreciate and understand art

even though we can not produce art to any great extent. This we may

think of as mental training.

The content of an art training course may be defined in terms of

objectives to be attained and these in turn should be determined through

a careful consideration of the art needs of girls and women. In order

to know these needs, the teacher must study the appearance, conditions,

and practices in the homes of her pupils. Through observation of the

general appearance and clothing of the pupils and a knowledge of their

interests and activities outside of school, she will obtain much

valuable information, but, in addition, it is highly desirable that she

visit their homes. This first-hand knowledge of the

[13]

homes and community

should be secured early in the school year and prior to the art unit

or course if possible. The teacher should also be constantly alert

to the many opportunities offered through community functions, local

stores, and newspapers for becoming more familiar with particular needs

and interests in her school community.

In making contacts in the homes and community, it is essential that the

teacher use utmost tact. Few homes are ideal as they are, but something

good can be found in all of them. The starting point should be with

the good features and from there guidance should be given in making

the best possible use of what is already possessed. It would be far

better for the girls to have no art work than to have the type of

course that develops in them a hypercritical attitude or that creates

an unhappiness or a sense of shame of their own homes. The aim of all

art work is to develop appreciation, not a critical or destructive

attitude.

Through such a study of girls' needs and interests certain general

objectives will be set up for units of courses in related art. Through

a well-planned program the majority of pupils in any situation may

reasonably be expected to develop—

1. A growing interest in the beauty to be found in nature and the

material things of their environment.

2. Enjoyment of good design and color found in their surroundings.

3. A desire to own and use things which have permanent artistic

qualities.

4. An ability to choose things which are good in design and color

and to use them effectively.

Out of these general objectives for all related art work, more

specific objectives based on pupils' immediate needs and interests are

essential. In terms of pupil accomplishment these objectives may

be as follows: 7

- I. Interest in—

- 1. Finding beauty in everyday surroundings.

- a. In nature.

- b. In man-made materials and objects.

- c. In art masterpieces.

- 2. Making homes attractive as well as comfortable.

- II. Development of a desire for—

- 1. Beautiful though simple and inexpensive possessions.

- 2. Skill in making artistic combinations and arrangements in home and clothing.

-

[14]

III. Ability to—

- 1. Select and make balanced arrangements.

- 2. Select articles and make arrangements in which the various proportions are pleasing.

- 3. Select and use articles and materials which are pleasing because there is interesting repetition of line, shape, or color.

- 4. Select and use articles and materials in which there is desirable rhythmic movement.

- 5. Select and make arrangements in which there is desirable emphasis.

- 6. Arrange articles in a given space so they are in harmony with the space and with each other.

- 7. Select colors suited to definite use and combine them harmoniously.

- IV. Appreciation of good design and color wherever found.

These specific objectives probably cover those phases of art for

which the average homemaker has the greatest need. In the limited

amount of time that is available for the related art units in most

vocational programs, the choice of what to teach must be confined to

the most fundamental facts and principles of art only. The problems

through which these are to be developed may be drawn for the most

part from actual situations within the girls' own experiences. It

should be remembered that the ulterior motive in all art training in

the homemaking program is to give to girls that which will make it

possible for them to achieve and to enjoy more beauty in their everyday

lives. In the average class few, if any, girls will have that type of

"creative ability" possessed by great artists, but all of the group may

be expected to attain considerable ability in selecting, grouping, and

arranging the articles and materials of a normal home and for personal

use. This may rightfully be termed creative ability. For example, the

girl who works out a successful color scheme through wise selections

and uses of color in her room or in a costume is indeed a creator of

beauty.

ESSENTIAL ART CONTENT

A very careful selection of content for the course or unit in related

art must be made. The vast amount of material in art from which to

choose makes the problem the more difficult. An attempt to teach with

any degree of success all of the content in art books and to give

pupils an understanding of all of the art terms would be futile and

would result in confusion. In the time available for art in the day

vocational schools, as well as in the part-time and adult classes, the

teacher is limited in her choice of content and must be guided by the

[15]

objectives for the course that represent the girls' needs in their

everyday problems of selection and arrangement.

Teachers are often baffled by the seeming multiplicity of terms. The

Federated Council on Art Education has recently issued the report

of its committee on terminology. The pertinent section dealing with

indefinite nomenclature is here quoted: 8

The subject of terminology in the field of art is extremely broad

and for the most part indefinitely classified. Over 100 technical

terms are in common use in the vocabulary of art. Often words are

used by different authors with entirely different meanings, and in

other cases the degree of difference between words is too slight

to warrant use of a separate term. Also many of the terms are

used interchangeably by different authors and frequently they

are ambiguous and obscure in meaning and difficult to apply in

public-school work.

In general, the literature used as a basis for planning, organizing,

and developing units of art instruction in the schools is very

indefinite in regard to nomenclature. For this reason the committee

on terminology centered the first part of its investigation upon a

program of analysis to determine, if possible, the most significant

words in common use.

In the preparation of this bulletin, several art texts, reference books,

and courses of study were examined for the purpose of determining the

art terms that were most frequently used. On that basis, from these

various sources the following were listed:

- Balance.

- Proportion.

- Repetition.

- Rhythm.

- Emphasis.

- Harmony.

- Color.

- Line.

- Light and dark.

- Unity.

- Radiation.

- Opposition.

- Transition.

- Subordination.

- Center of Interest.

- Dominance.

Since the content for a course in related art should contribute very

definitely to the girl's present and future individual and home needs

it is suggested that only the minimum essential terminology be used,

remembering that in such a course the chief concern is the development

of those principles and facts that contribute to the realization of

such objectives as have been suggested.

There seems to be common agreement that balance, proportion, repetition,

rhythm, emphasis, harmony, and color are of first importance in their

contribution to beauty and that the various principles and facts

concerning each should be developed in an art unit or course. The

selection of these seven phases of art as fundamental is supported

by Goldstein, 9 by Russell and Wilson, 10 and by Trilling and

Williams. 11

[16]

The committee on art terminology has also given emphasis to these in

the classification as set up in Table V of their report. This is here

given in full.

Simplest form of classification 12

| Basic elements | Major principles | Minor principles | Resulting attributes | Supreme attainment |

|---|

| Line. | Repetition. | Alteration. | | |

| Form. | | Sequence. | | |

| | Rhythm. | | Harmony. | |

| | | Radiation. | | |

| Light and Dark. } Tone. | Proportion. | Parallelism. | | Beauty. |

| | | Transition. | | |

| | Balance. | | Fitness. | |

| Color. | | Symmetry. | | |

| Texture. | Emphasis. | Contrast. | | |

|

|---|

It will be noted that repetition, rhythm, proportion, balance, and

emphasis are listed as major principles. It will also be noted that

harmony is classified as a resulting attribute. This will be the

inevitable result if the principles of the first five are well taught.

Arrangements which meet the standards of good proportion, which are

well balanced and which are suited to the space in which they are

arranged will be harmonious.

Although color is designated as a basic element of art structure in

this table and the principles of design function in the effective use

of it, there are some guides of procedure in the use of those qualities

of color, such as hue, value, and intensity, which should be developed

to insure a real ability to select colors and combine them harmoniously.

Line is also considered a basic element of art structure. Since the

problems in a course in art related to the home are largely those of

selection, combination, and arrangement, the consideration of line may

be confined to its effect as it provides pleasing proportions, is

repeated in an interesting manner, or produces desirable rhythm.

The omission of the remainder of the art terms that were found to be

frequently used in art books and courses of study is not as arbitrary

as it seems. Through the consideration of the qualities of color it

will be found that value includes the material often given under "light

and dark" or "notan."

Referring again to the report of the Committee on Art Terminology, 13

"unity" is considered as a synonymous term for "harmony." Since it

is possible for an arrangement to be unified and still be lacking in

harmony, the latter term is used in the bulletin as the more important

and inclusive one. There is less obvious need for the principles of

"radiation," "opposition," and "transition" in

[17]

problems of selection

andarrangement. The Goldsteins refer to them as methods of arranging

the basic elements of lines, forms, and colors in contributing to the

principles of balance, proportion, rhythm, emphasis, and harmony. Thus

some reference to them may be made in the development of the principles

of harmony and rhythm.

Emphasis has been chosen as an inclusive term which represents

"subordination," "center of interest," and "dominance."

It is hoped that these suggested phases of art to be included in a

course or unit in art related to the home will not be considered too

limited. Each teacher of art should feel free to develop as many of

the principles as are needed by her groups, remembering that it is far

better to teach a few principles well than to attempt more than can

be done satisfactorily.

In developing the principles of design certain guides for procedure

or methods in achieving beauty will be formulated. For example, in

considering balance, pupils will soon recognize that the feeling of

rest or repose that is the result of balance is essential in any

artistic or satisfying arrangement. Their problem is how to attain it

in the various arrangements for which they are responsible. Thus guides

for procedure or methods of attaining balance must be determined. Such

guides for obtaining balance may be—

1. Arranging like objects so they are equidistant from a center

produces a feeling of rest or balance.

2. Unlike objects may be balanced by placing the larger or more

noticeable one nearer the center.

It will be seen that these are also measuring sticks for the judging

of results. It is evident that in a short course in art a teacher can

not assist girls in all situations at home in which balance may be

used. Therefore it is essential that the pupils understand and use

these guiding laws or rules for obtaining balance in a sufficient

number of problems at school to gain independence in the application

of them in other situations. Some authorities 14 term these methods

for attaining results, guiding laws for procedure, or principles.

HOME SITUATIONS FOR WHICH ART IS NEEDED

The common practice in art courses relating to the home has been to

draw problems from the fields of clothing and home furnishing. This

has been true for the obvious reason that an endeavor has been made

to interest the girl in art through her personal problems of

[18]

clothing

and her own room. Since in a vocational program the objective is

to train for homemaking, it is essential that art contribute to

the solving of all home problems in which color and good design are

factors. In the selection and utilization of materials that have to

do with child development, meal preparation and table service, home

exterior as well as interior, and social and community relationships,

application of the principles of art plays a large and important part.

One of the teacher's great problems is that of determining pupil needs.

Although homes vary considerably in detail, there are many similar

situations arising in all of them for which an understanding of the

fundamental art principles is essential. It is important that the

problems and situations utilized for developing and then applying again

and again these fundamental principles shall be within the realm of

each student's experience. The following series of topics may suggest

some of the situations that are common to most homes and therefore be

usable as the basis for problems in developing principles of art or

for providing judgment and creative problems. In most of these topics,

other factors such as cost, durability, and ease of handling will need

to be considered in making final decisions, for art that is taught in

relation to the home is not divorced from the practical aspects of it.

- Child development—

- Choosing colored books and toys for children.

- Choosing wall covering for a child's room.

- Choosing pictures for a child's room.

- Placing and hanging pictures in a child's room.

- Selecting furniture for a child's room.

- Determining types of decoration and desirable amounts of it for children's clothing.

- Choosing colors for children's clothing.

- Making harmonious combinations of colors for children's clothing.

- Choosing designs and textures suitable for children's clothing.

- Avoiding elaborate and fussy clothing for children.

- Meal planning and table service—

- Using table appointments that are suitable backgrounds for the meal.

- Choosing appropriate table appointments in—

- Linen.

- China.

- Silver.

- Glassware.

- [19]

Using desirable types of flowers or plants for the dining table.

- Making flower arrangements suitable in size for the dining table.

- Selecting consistent substitutes for flowers on the table.

- Choosing containers for flowers or plants.

- Using candles on the table.

- Deciding upon choice and height of candles and candlesticks in relation to the size and height of the centerpiece.

- Determining when to use nut cups and place cards.

- Choosing place cards and nut cups.

- Arranging individual covers so that the table is balanced and harmonious.

- Folding and placing napkins.

- Considering color and texture of foods in planning menus.

- Determining when and how to use suitable food garnishes.

- Home—Exterior—

- Developing and maintaining attractive surroundings for the house.

- Choosing dormers, porches, and porch columns that are in scale with the house.

- Grouping and placing the windows so they are harmonious with each other and with the house.

- Planning suitable and effective trellises and arbors.

- Recognizing limitations in the use of formal gardens and grounds.

- Determining the use of the informal type of grounds.

- Choosing house paint and considering how it may be influenced by neighboring houses.

- Determining the influence of the color of the house on the choice of color for the porch furniture and accessories and for awnings.

- Selecting and arranging porch furniture and accessories.

- Selecting curtains for the windows of the house which are attractive from the exterior as well as from the interior.

- Determining desirable shapes for trimmed hedges and shrubbery.

- Selecting shrubbery and flowers that will contribute, at small cost, to the appearance of a home.

- Planning the grounds of a home and the possible use of a bird bath, an artificial pool, or a rock garden.

- [20]

Home—Interior—

- Securing beauty rather than display.

- Selecting textures that suggest good taste rather than merely a desire for display.

- Choosing wall coverings that are attractive and suitable backgrounds for the home.

- Selecting rugs for various rooms.

- Selecting furniture that adds attractiveness, comfort, and convenience to the home.

- Determining relation of beauty in furniture to the price of it.

- Choosing window shades, curtains, and draperies from the standpoint of color, texture, design, and fashion.

- Selecting appropriate accessories for the home.

- Determining when to use pictures and wall hangings in the home.

- Choosing pictures and wall hangings for the home.

- Placing rugs, furniture, and accessories in the home.

- Arranging and hanging pictures and wall hangings.

- Determining the relation of type and arrangement of furnishings and accessories to the formality or informality of a room.

- Avoiding formal treatment and shiny textures in the average home.

- Planning how color may be used and distributed effectively in a room.

- Determining how color schemes of rooms are affected by size, purpose, and location.

- Discouraging the use of cloth, paper, and wax flowers and painted weeds in the home.

-

Social and community relations—

- Determining social and community activities with which high school girls are asked to assist and for which art training is needed.

- Making attractive and suitable posters for special occasions.

- Selecting and arranging flowers and potted plants for various occasions.

- Planning, selecting, and using appropriate decorations for special events.

- Wrapping gifts and packages attractively.

- Choosing and using appropriate stationery, calling cards, place cards, and greeting cards.

- [21]

Clothing—

- Determining appropriate clothing for all occasions.

- Planning clothing that adds to rather than detracts from the charm of the wearer.

- Planning to avoid garments and accessories that may be liabilities rather than assets.

- Recognizing the relation of the "style of the moment" to the choice and combination of the clothing for the individual.

- Choosing colors for the individual.

- Utilizing bright colors in clothing.

- Selecting harmonious color combinations in clothing.

- Selecting and using textile designs in clothing.

- Selecting and adapting style designs in patterns for the individual.

- Improving undesirable body lines and proportions through the wise choice of clothing.

- Selecting clothing accessories—

- Hats.

- Shoes.

- Hosiery.

- Gloves.

- Bags.

- Jewelry.

- Selecting and using appropriate jewelry and similar accessories with various ensembles.

- Choosing texture, color and design for undergarments that make appropriate and attractive foundations for the outer garments.

As yet no committee on related art has proceeded so far as to suggest

specific content for art courses that are related to homemaking.

Since this bulletin deals with the teaching of art as it relates

to homemaking, teaching content is presented only in so far as it

exemplifies methods or procedures and relates to objectives. It is

hoped, however, that teachers will find real guidance for selecting

content that will meet the particular needs of their classes through,

the detailed consideration of objectives, the selection of principles,

and the many suggestions that are offered for art applications that can

be made in all phases of homemaking.

[22]

Section IV

SUGGESTIVE TEACHING METHODS IN ART RELATED TO THE HOME

The test of a real product of learning is this: First, its

permanency; and second, its habitual use in the ordinary activities

of life.—Morrison.

CREATING INTEREST

There is a general conception that art is naturally interesting to

everyone. Accepting this as true, a specific interest must be developed

from this natural interest for the most effective courses in art

training. Whitford 15 says:

Little can be accomplished in general education, and practically

nothing can be done in art education, unless interest and enthusiasm

are awakened in the student. The awakening of interest constitutes

one of the first steps in the development of a pupil's natural

talents.

Some teachers, in attempting to awaken or to hold the interest of

girls in related art courses, have started with art laboratory problems

which involve considerable manipulation of materials. A certain type

of interest may be so aroused, for pupils are always interested in the

manipulative processes involved in producing articles and even more

in the possession of the completed products, but it may be only a

temporary appeal rather than an interest in the larger relation of art

to everyday living. While it is true that manipulative problems do

contribute to the development of greater confidence and initiative

and therefore have their place in an art course, yet the successful

completion of most products requires greater creative and judgment

abilities than pupils will have acquired early in the course. It is

then a questionable use of laboratory problems to depend upon them for

awakening the specific interest in art.

Initial interest of students may be stimulated through directed

observation of the many things about them which are good in color and

design or by discussion of problems which are very pertinent to girls'

art needs or desires. 16 However, conscious effort on the part of

[23]

the

teacher is necessary to "open the windows of the world," if pupils are

to develop real interest and experience such enjoyment from the beauty

which surrounds them that an ideal of attaining beauty in dress and

home is established. A definite plan is necessary for stimulating this

interest which is said to be possessed by all. Without an interest that

will continue to grow from day to day it is difficult to develop the

necessary judgment abilities for solving everyday problems in selection

and arrangement.

Professor Lancelot 17 suggests the following procedure as the initial

steps in the building of permanent interests:

1. Early in the course endeavor through general class discussions,

rather than by mere telling, to lead the students to see clearly

just how the subject which they are taking up may be expected to

prove useful to them in later life and how great its actual value

to them will probably be.

2. At the same time attempt to establish clearly in their minds the

relationships that exist between the new subject, taken as a whole,

and any other branches of knowledge, or human activities, in which

they are already interested.

3. Specify and describe the new worthwhile powers and abilities which

are to be acquired from the course, endeavoring to create in the

students the strongest possible desire or "feeling of need" for them.

If this procedure is followed, in the field of art the teacher will

refrain from merely telling pupils that art will be of great value

to them later in life. On the other hand, in creating interest it is

suggested that class discussion of general topics within the range of

pupil experience and of obvious need be used to awaken an interest in

the value of art in their own lives.

The teacher must be sure that the topics are of real interest to the

pupils. For example, which of these questions would probably arouse the

most animated discussion: "What is art?" or "Arnold Bennett says, 'The

art of dressing ranks with that of painting. To dress well is an art

and an extremely complicated and difficult art.' Do you agree with

Arnold Bennett? Why?"

Other discussions may be started by asking questions such as the

following:

1. Have you ever heard some one say, "Mary's new dress is lovely

but the color is not becoming to her"? Why do people ever choose

unbecoming colors? Would you like to be able to select colors

becoming to you? How can you insure success for yourself?

2. Movie corporations are spending great sums of money in an attempt

to produce pictures in color. Why do they feel justified in making

such expenditures to introduce the single new quality of color?

[24]

[25]

3. Do you like this scarf? This cushion? This picture? Why? Why not?

Why is there some disagreement? To what extent can our likes guide

our choices?

4. The class may be asked to choose from a number of vases, lamp

shades, table covers, or candles those which they think are most

beautiful. The question may then be asked, "Would you like to find

out what makes some articles more beautiful than others?"

5. Where in nature are the brightest spots of color found? Have you

ever seen combinations of color in nature that were not pleasing?

How may we make better use of nature's examples?

6. Why do girls and women prefer to go to the store to select dresses

or dress material? Hats? Coats? Can one always be sure of the most

becoming thing to buy even when shopping in person? What would be

helpful in making selections?

The classroom setting for the teaching of art plays a very important

part in arousing interest. Attempting to awaken interest in art

in a bare, unattractive room is even more futile than trying to

create interest in better table service with no table appointments.

In the first situation there is probably such a wide variation in the

background and experience of the pupils and in their present ability

to observe the beautiful things of their surroundings that it becomes

increasingly important that the teacher provide an environment which is

attractive and inviting. In the second situation the pupils have had

experience with the essential equipment in their own homes and so can

visualize to some extent the use of that equipment at the table.

Bobbitt 18 says—

One needs to have his consciousness saturated by living for years

in the presence of art forms of good quality. The appreciations

will grow up unconsciously and inevitably; and they will be normal

and relatively unsophisticated. As a matter of fact, art to be most

enjoyed and to be most serviceable, should not be too conscious.

Schoolrooms in which pupils spend a large part of their waking hours

should provide for the building of appreciation in this way, and it is

especially true in the homemaking room. Some home economics teachers

have cleverly planned for students to share in the responsibility

of creating and maintaining an attractive classroom as a means of

stimulating interest in art. It would be well for all home economics

teachers to follow this practice.

[26]

[27]

In many economics laboratories there are several possible improvements

that would make better environment for art teaching. Suggestions for

such improvements include:

- 1. More color in the room through the use of flowers, colorful pottery, colored candles, and pictures, featuring arrangements that could be duplicated in the home.

- 2. More emphasis upon structural lines—

- a. Pictures that are grouped and hung correctly.

- b. Attractive arrangement of a teacher's desk.

- c. Arrangement of the furniture so that the groupings are well balanced and the wall spaces are nicely proportioned.

- d. Good arrangement of materials on bulletin board.

- 3. More attention to orderliness—

- a. When class is not working, orderliness in window-shade arrangement.

- b. Elimination of unnecessary objects and furnishings to avoid cluttered appearance.

- c. Tops of cases and cupboards or open shelves cleared.

There are few seasons in the year when the teacher can not introduce

interesting shapes and notes of color through products of nature. The

fall brings the colored leaves and bright berries which last through

the winter. Bulbs may be started in late winter for early spring, and

certain plants can be kept successfully throughout the year. With such

interesting possibilities for using natural flowers, berries, and

grasses, why would a teacher resort to the use of artificial flowers

or painted grasses?

Morgan 19 pertinently discusses the artificial versus the real:

Some say "What about painted weeds and grasses?" No; that is mockery.

It doesn't seem fair to paint them with colors that were not theirs

in life. One can almost fancy hearing the dead grasses crying out,

"Don't smear us up and then display us like mummies in a museum."

Remember, a true artist, one who truly loves beauty, despises

imitation or deceit.

There are several interesting possibilities for home table centerpieces

to be used during the winter months when flowers are not available.

Grapefruit seeds or parsley planted in nice-shaped, low bowls grow

to make attractive-shaped foliage for the table. A sweetpotato left

half covered with water in a low bowl sprouted and made the graceful

arrangement of pretty foliage pictured in Figure 7, page 29.

Pupils are more apt to provide such plants in their homes if they see

examples of the real centerpieces at school. It is, therefore, worth

while for a teacher to direct a class in starting and caring for one

or more types of them.

[28]

In one State a definite effort is made in planning home-economics

departments to have the dining room open directly into corridors

through which most of the pupils of the entire school pass at some time

during the day. See figure 8, page 30.

This arrangement permits pupils to observe attractive as well as

suitable arrangements of the dining room furnishings, and especially of

the table. Such a plan should be effective in establishing ideals of

what is good and in raising standards in the homes of boys as well as

of girls in the community.

A further contributing essential to stimulating interest in art is a

teacher who exemplifies in her appearance the art she is teaching.

[29]

It is said that sometimes our most successful teaching is done at a

time when the teacher is least conscious of it. The teacher of an art

class who appears in an ensemble of clothing which is unsuited to the

occasion and in which the various parts are not in harmony with each

other from the standpoint of color, of texture, or of decoration loses

sight of one of her finest opportunities for influencing art practices

of pupils and developing good taste in them.

There is no more applicable situation for the old adage, "Practice what

you preach," than in the teaching of art. One teacher was conducting a

discussion on the choice of bowls and vases for flowers as a part of

flower arrangement while behind her on the desk was a bottle into which

a bunch of flowers had been jammed. Contrast this with the situation in

which the teacher had worked out the arrangement of wild flowers and

grasses as shown in Figure 1.

DISCUSSION OF METHOD IN THE TEACHING OF ART

In discussing the best methods of teaching art, Whitford 20 says:

As a practical subject art education calls for no exceptional

treatment in regard to methods of instruction. The instruction

should conform to those general educational principles that have

been found to hold good in the teaching of other subjects. Without

such conformity the best results can not be hoped for.

[30]

It is anticipated that through the course in related art pupils will

have gained an ability to choose more suitably those materials and

articles of wearing apparel and of home furnishing which involve color

and design. It is through understanding certain fundamental principles

of art and using them that the everyday art problems can be more

adequately solved. The teacher is confronted with the question as to

how to develop most successfully this understanding and ability. Shall

she proceed from the stated principles to their

[31]

application in solving

problems or shall she start with the problems and so direct their

solution that the important principles and generalizations are derived

in the process. The present trend in education is toward the second

procedure and in keeping with this trend, the elaboration of method

in this section is confined to the so-called problem-solving method.

When pupils have an opportunity to formulate their own conclusions in

solving problems and through the solution of many problems having an

identical element find a generalization or principle that serves as a

guide in other procedures, experience seems to indicate that they get

not only a clearer conception of the principle but are able also to

make greater subsequent use of it.

In their everyday experiences pupils are continually faced with the

necessity for making selections, combinations, and arrangements which

will be satisfying from the standpoint of color and design. Before they

can select wisely they need some standards upon which to base their

judgments and by which they can justify their decisions. Before they

can make satisfying arrangements and combinations of material they need

judgment skill in determining what to do. They also need principles

or standards by which they can determine how to proceed. Finally,

they need opportunity for practice so that they may become adept

in assembling articles and materials into pleasing and harmonious

groupings and arrangements.

The more experience pupils have in confronting and solving true-to-life

problems under the guidance of the teacher, the greater is the probability

that they will have acquired habits of thinking that will enable them

to solve successfully the many problems that they are continually forced

to meet in life.

It might be well to inquire at this point the meaning of the word

problem as used in this bulletin. According to Strebel and Morehart 21—

Probably there is no better definition of a problem than the

condition which is spoken of by Doctor Kilpatrick as a "balked

activity." This idea is general enough to include all sorts and

phases of problems, practical and speculative, simple and difficult,

natural and artificial, final and preliminary, empirical and

scientific, and those of skill and information. It covers the

conditions which exist when one does not know what to do either

in whole or in part, and when one knows what to do but not how to

do it, and when one knows what to do and how to do it but for lack

of skill can not do it.

In teaching by the problem-solving method Professor Lancelot 22 makes

use of three types of problems.

Through the first type, known as the inductive problem, the pupil

is to determine certain causes or effects in the given situation. In

[32]

determining these causes and effects, various details of information

are needed but these do not remain as isolated and unrelated items. Out

of the several facts is evolved a general law, a truth, or a principle.

For example, in developing pupil ability to understand and use the

underlying principle of emphasis, the teacher may make use of such

questions as:

Have you ever tried to watch a three-ring circus? Pupils are

given an opportunity to relate their experiences.

Have you ever seen a store window that reminded you of a circus?

In which of the store windows on Center Street do you think the

merchant has displayed his merchandise to the greatest advantage?

Why?

From a discussion of such questions as these the teacher can lead the

pupil to realize the desirability of avoiding confusion in combining

and arranging articles used together and to understand at least one way

of producing the desired effect.

The next type is the judgment or reasoning problem, which offers

two or more possible solutions. In certain subjects as mathematics

in which there is but one correct answer, the reasoning problem is

used. In other subjects in which, in the light of existing conditions,

there is a best answer, the judgment problem is used. This best answer

or final choice is determined upon the basis of the law or principle

established through the inductive problems. Few subjects are more

concerned with the making of choices than art. For this reason,

judgment problems play an important part in an art training which is

to function in the daily lives of pupils. As soon as a principle has

been tentatively established, it is desirable to give the pupils an

opportunity to recognize the use of the principle in several similar

situations and to use it as a basis for making selections. For example,

following the establishment of the principle of emphasis, the teacher

may ask the pupils:

Will each of you select from these magazines an advertisement

in which your attention was immediately attracted to the article

for sale? Be ready to tell the class why you were attracted to

this piece of merchandise.

The third and final type is the creative problem, which makes use of

the truth or principle discovered in the inductive problems, so that

the pupil is encouraged to do some creative thinking by using the

principle as the basis for determining procedure to follow in a new

situation. Since everyday living is full of opportunities for making

choices and combinations, it is essential that both judgment and

creative problems be included in practical art training. For example,

to teach the use of the creative problem in the study of emphasis the

instructor may say to a pupil:

Choose a partner with whom to work. From the materials I am

providing make an attractive table arrangement for a living room,

and then choose a large piece of wallpaper or a textile that

would make a good background for it.

[33]

Lamps, candles, candlesticks, flowers, pottery, and books will be

provided for this activity, as well as the textiles and the wallpaper.

Professor Lancelot 23 sets up five standards for determining what

are good problems. They must, he says, be—

1. Based on true-to-life situations.

2. Interesting or connected with things of interest.

3. Clearly and definitely stated.

4. Neither too difficult nor too easy.

5. Call for thinking of superior ability.

In addition, there are four other factors to be considered in the

planning of a successful problem series;

1. Each problem should score high according to the above standards.

2. The usual sequence is in the order already given—inductive,

judgment, and creative. Since the creative problems call for the

highest type of thinking and are the most difficult, the natural

place for them is at the end of the problem series. At that point

the pupils should have sufficient information and judgment ability

to enable them to solve the most difficult problem quite readily.

Introducing the difficult problem too soon may discourage the

pupil and lessen interest in the course as a whole. Some creative

problems involve fewer art principles than others. For example,

the spacing of a name on a place card is much simpler than the

hanging of a picture in a given space. In art it is desirable to

use simple creative problems as they fit naturally into the problem

series. (See pp. 38-39.)

3. As the problem series develops, there should be an increase in the

difficulty of the problems. It is obvious that the simpler problems

are to be used at the first of the series. To develop judgment to

a desirable extent, the later choices will be determined from an

increasing number of similar situations and from situations in

which the degree of difference decreases as the problem series

progresses.

4. Each problem series should involve as many types of life situations

as possible. For example, applications of art are needed in the

various phases of homemaking. (See Section III, pp. 18-21.) For that

reason it is very desirable to select problems in each series from

as many of these phases as possible. By this means the pupils are

better able to cope with their own problems in which a fundamental

art truth, or principle is the basis for adequate solution.

[34]

The following detailed procedure is presented as an illustration of

the way in which an art principle may be developed through a problem

series. It may appear to be unnecessarily detailed and to require more

time than the average teacher would have for planning. However, part

of material here given consists of probable pupil replies and a

description of the illustrative materials that are to be used.

SUGGESTED PROCEDURE FOR DEVELOPING AN ABILITY TO USE A PRINCIPLE OF

PROPORTION FOR ATTAINING BEAUTY

An effort is here made to present the details of a teaching plan by

which a principle of proportion may be developed by the pupils. This

plan is spoken of as a lesson, but not in the sense that it is to be

accomplished in a limited amount of time, such as one class period.

The term lesson is used to designate the entire procedure from the

introductory problem to the point where the pupils have developed the

ability to use the principle of proportion. It will be possible to make

more rapid progress with some classes than with others and in some

class periods than in others. It is suggested that the teacher endeavor

to evaluate the class time and plan so that the end of the period

comes not as an interruption but as a challenge to further interest,

observation, and efforts.

The lesson suggested below should take not more than three of the

short class periods of 40 to 45 minutes. If too much time is spent on

one series there may be a lessening of interest because of seeming

repetition. On the other hand, if sufficient applications and problems

are not used after the principle is established, there is danger that

the pupils will not be able to use it in solving other daily problems.

Further suggestions for problems, illustrative materials, and

assignments may be found on page 40.

SUGGESTED PLAN FOR THE DEVELOPMENT OF AN UNDERSTANDING OF THE PRINCIPLE

OF PROPORTION AND ITS USE

-

General objective.—To develop ability to—

- Select articles which are pleasing because of good proportions.

- Adapt and make pleasing proportions as needed.

-

Specific objective.—To develop ability to—

- Divide a space so the resulting parts are pleasing in their

relationship to each other and to the whole.

Assume that the group to be taught is a ninth-grade class in art

related to the home. Very few members of the class have had any

previous art training and such training has consisted of some drawing

and water-color work in the lower grades. Previous to this lesson, it

is assumed that the teacher has developed the pupils' interest

[35]

in the

beauty to be seen and enjoyed in the everyday surroundings of their

community, and has developed pupil ability to understand and to use a

principle of proportion, namely, that a shape is most pleasing when

one side is about one and one-half times as long as the other.

The establishment of the above principle has probably given the class an

opportunity to read of the Golden Oblong or the Greek Law of proportion

in an art reference such as Goldstein's Art in Everyday Life. This

will have served to further establish a feeling for interesting shape

relationships and also will have made the pupils familiar with the term