The Project Gutenberg EBook of A History of the Boundaries of Arlington County, Virginia, by Office of the County Manager, Arlington This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net Title: A History of the Boundaries of Arlington County, Virginia Author: Office of the County Manager, Arlington Release Date: July 30, 2011 [EBook #36902] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK BOUNDARIES OF ARLINGTON COUNTY *** Produced by Mark C. Orton and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

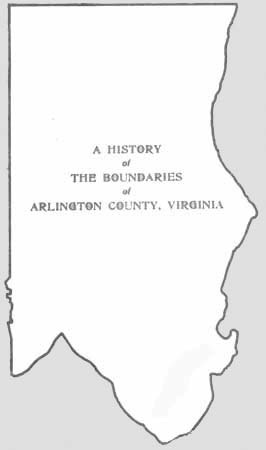

THE BOUNDARIES OF ARLINGTON

1791 1801 184

6

1870 1875 191

5 1929 1936&n

bsp; 1946 1966

FOREWORD TO THE SECOND EDITION

This collection of documentary references to the boundaries of Arlington County was first published in 1957. This new edition contains revisions made in the light of fuller knowledge, and brings the story up-to-date by taking account of the change in the common boundary with the City of Alexandria which went into effect on January 1, 1966.

This pamphlet can serve as a guide for those who need to know what jurisdiction covered this area at any particular time. It provides information for the student as well as the title searcher—in fact, for anyone interested in the history of what is now Arlington County.

Bert W. Johnson

County Manager

A History of

The Boundaries of

Arlington County, Virginia

TABLE OF CONTENTS

| Page | |

| Introduction—Arlington County Today | 1 |

| 1608-1789 | 2 |

| The Charters of James I to the Virginia Company | |

| Charles I Charter to Lord Baltimore | |

| The Counties of the Northern Neck of Virginia | |

| 1789-1847 | 3 |

| Into the District of Columbia: | |

| Cession of 1789 | |

| Location of the Federal District | |

| Out of the District: | |

| Acts of 1846 | |

| In Virginia Once More, 1847 | |

| ARLINGTON'S BOUNDARY WITH THE CITY OF ALEXANDRIA | 14 |

| Establishment of Alexandria as a Town | |

| Territorial Accretions of Alexandria to 1870 | |

| County-City Separation, 1870 | |

| Annexations by Alexandria from Arlington, 1915 and 1929 | |

| Readjustment of Boundaries, 1966 | |

| ARLINGTON'S BOUNDARY WITH THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA | 24 |

| Boundary of Commission of 1935 | |

| Acts of 1945 and 1946 | |

| POSTSCRIPTS—TOWNS IN ARLINGTON COUNTY | 27 |

| The Town of Falls Church | |

| The Town of Potomac | |

| No More Towns | |

| Appendix. | |

| Bibliography. |

A History of

The Boundaries of

Arlington County, Virginia

It is one of those paradoxes so characteristic of Arlington that the area composing the County did not exist as a separate entity until it was ceded by Virginia to form part of the District of Columbia. The Act by which the Congress of the United States took jurisdiction over this area directed that that portion of the District which had been ceded by Virginia was to be known as the county of Alexandria.[1] (It was not until 1920 that it received the name of Arlington.)[2]

The present boundaries of Arlington may be described as: Beginning at the intersection of Four Mile Run with the west shore line of the Potomac River, westwardly, in general along the line of Four Mile Run, without regard to its meanders, intersecting the south right-of-way line of the Washington and Old Dominion Railroad, then 1,858.44 feet to where the center line of Shirlington Road intersects the said south right-of-way line; thence south and slightly east to the center line of Quaker Lane, then following the center line of Quaker Lane to a point short of Osage Street in Alexandria where it moves to the north line of Quaker Lane; thence to the east right-of-way line of Leesburg Pike (King Street); thence with this line to the east side of 30th Street, South, in Arlington, northeast on 30th Street, South, to the circle; around said circle to the north side of South Columbus Street, along this line to 28th Street, South, returning for a short distance to Leesburg Pike, jogging east and north to 25th Street, South, and then back to Leesburg Pike; thence along the Pike to the common boundary of Alexandria and Fairfax; thence northeast along the former Alexandria-Fairfax boundary until it intersects the original boundary between Arlington and Fairfax; thence due northwest to a stone and large oak tree approximately 200 feet west of Meridian Avenue (North Arizona Street); thence due northeast to the shore of the Potomac; thence along the mean high water mark of the shore of the Potomac River, back to the point of beginning. This line encloses roughly 16,520 acres, or approximately 25.7 square miles, thus making Arlington the third smallest county in the United States in respect to area.[3]

The boundaries of this area have been changed many times since it was first sighted by Captain John Smith on his voyage up the Potomac in 1608—the year which can be said to mark the beginning of Arlington's history.

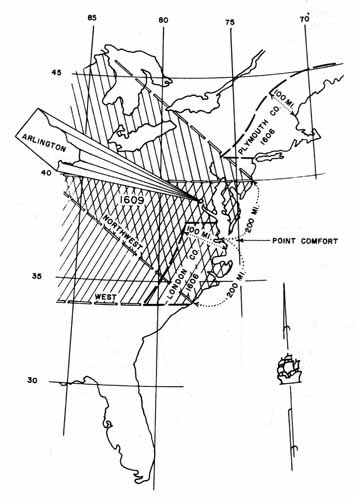

1608-1789

The circumstances which placed Arlington in Virginia began to take shape even earlier than 1608. The two companies organized to colonize Virginia were granted their first charter by James I of England on April 10, 1606.[4] This was styled "Letters Patent to Sir Thomas Gates, Sir George Somers, and others, for two several Colonies and Plantations, to be made in Virginia, and other parts and Territories of America." The patentees were authorized "… to make habitation, plantation, and to deduce a colony of sundry of our people into that part of America, commonly called Virginia …" between 34° north latitude and 45° north and within 100 miles of the coast. Within this area the spheres of operation of the two companies (which came to be known as the London and Plymouth Companies because their principal backers hailed from one or the other of these English towns) were delineated. To the former was given the right to plant a colony within the area from north latitude 34° to 41°, and to the latter within the area from 38° to 45° inclusive. The overlapping area from 38° to 41° was open to settlement by either company, though neither might establish a settlement within 100 miles of territory occupied by the other. The actual jurisdiction of each company was limited to 50 miles in each direction from the first seat of plantation. This last restriction was not carried over into the second charter. (Map I.)

MAP I

Bounds Set by First Two Charters of the Virginia Company

Drafted by W. B. Allison and B. Sims

Although the Plymouth Company sent out ships in the spring of 1607, the settlement attempted by them on the coast of Maine was abandoned the following year. The first settlement which was to prove permanent was made by the London Company whose ships, sailing from London in December 1606, reached the mouth of the James River in Virginia in April 1607. The founding of "James Cittie" provided a point of reference for the second charter of the London Company (which came to be known as the Virginia Company). This charter,[5] granted in 1609, gave it jurisdiction over

"all those lands, countries, and territories, situate, lying, and being, in that part of America called Virginia, from the point of land, called Cape or Point Comfort, all along the sea coast, to the northward 200 miles, and from the said Point or Cape Comfort, all along the sea coast to the southward 200 miles, and all that space and circuit of land, lying from the sea coast of the precinct aforesaid, up into the land, throughout from sea to sea, west and northwest; and also all the islands lying within one hundred miles, along the coast of both seas of the precinct aforesaid;…"

This grant reflects the view of the best geographers of the day that the Pacific Ocean lapped the western side of the as yet unexplored and unnamed Appalachian Mountains.

The third charter of the Virginia Company,[6] granted in 1612, extended the eastern boundaries of the colony to cover "… all and singular those Islands whatsoever, situate and being in any part of the ocean seas bordering upon the coast of our said first colony in Virginia, and being within three hundred leagues of any the parts heretofore granted …" This was done to include Bermuda which had been discovered in the meantime. The charter of the Virginia Company was annulled in 1624 by King James I, and its lands became a Crown Colony. By this time, however, the Virginia settlements were firmly established on and nearby the James River, and the Potomac River to the falls was well known to traders with the Indians.

The first limitation upon the extent of the "Kingdom of Virginia," as it was referred to by King Charles I, who succeeded his father in 1625, came with the grant to Lord Baltimore of a proprietorship over what became Maryland. This patent was granted in 1632; the first settlers reached what became St. Mary's on the Potomac in 1634. That part of the grant which is pertinent to the boundaries of Arlington reads:

"Going from the said estuary called Delaware Bay in a right line in the degree aforesaid to the true meridian of the first fountain of the river Potomac, then tending downward towards the south to the farther bank of the said river and following it to where it faces the western and southern coasts as far as to a certain place called Cinquack situate near the mouth of the same river where it discharges itself in the aforenamed bay of Chesapeake and thence by the shortest line as far as the aforesaid promontory or place called Watkins Point."[7]

The most significant words of this grant, from the point of view of Arlington, are "the farther banks of the said river." They explain why the boundary between Arlington and the District of Columbia runs along the Virginia shore of the river and not in midstream, and why Roosevelt Island, which lies nearer Arlington than to the District, is not a part of Arlington. The Constitution of Virginia adopted in 1776 acknowledges this grant:

"The territory contained within the charters erecting the colonies of Maryland … are hereby ceded, released, and forever confirmed to the people of those colonies …"[8]

Although at the time Charles I gave this grant to Lord Baltimore Virginia was a Crown Colony and thus it could not be contended that he was giving away lands he had no power to cede since they already had been given to others, the Maryland-Virginia boundary became a subject of controversy as soon as the first Maryland settlers arrived, and has continued so until almost the present time. Indeed, one might say that the ghost has been laid only temporarily since echoes of the dispute appear in today's newspapers: "Maryland and Virginia Start New Round in Oyster War"—"Pentagon Area a No Man's Land." These headlines derive in a direct line from the grant of King Charles I to Calvert, Lord Baltimore, in 1632.[9]

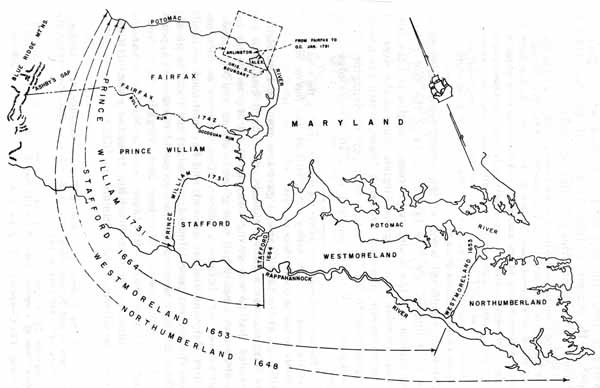

To leave, for a time, the Potomac boundary of Arlington, let us turn to the narrowing of the boundaries of the landward side of the County. In the development of governmental administration, counties began to be created in Virginia in mid-17th Century. The area which became Arlington was successively in Northumberland, Westmoreland, Stafford, Prince William, and finally, Fairfax counties. (Map II.) Consequently, the history of land tenure and legislation for Arlington must be sought in the records of these counties for the relevant period.

MAP II

Development of Northern Neck Counties

Drafted by W. B. Allison and B. Sims

Northumberland County was definitely created in 1648 by an Act of the General Assembly[10] which provided

"that the said tract of land ['Chickcoun and other parts of the Neck of land between Rappahonock River and Potomack River'] be hereafter called and knowne by the name of the county of Northumberland...."

and was given power to elect Burgesses. A later Act[11] declared:

"It is enacted, That the inhabitants which are or shall be seated on the south side of the Petomecke River shall be included and are hereafter to be accompted within the county of Northumberland."

Settlement was pushing north, however, and in July 1653, Westmoreland was carved out of the then existing Northumberland. It was decreed:

"ordered by this present Grand Assembly that the bounds of the county of Westmorland be as followeth (vizt.) from Machoactoke river where Mr. Cole lives: And so upwards to the falls of the great river of Pawtomake above the Necostins Towne."[12]

Conditions on the frontier, however, made it necessary in 1662 to unite Westmoreland and Northumberland counties for administrative purposes "until otherwise ordered by the governor."[13] There is no record of the date of his later decision to separate the two counties but he must have done so.

Similarly, there is no definite record of the establishment of Stafford County. The first legislative reference to Stafford is in an Act[14] exempting the inhabitants of Stafford because of the "newnesse of its ground" from a general requirement laid upon counties to employ a weaver and set up a public loom. In this year of 1666 Stafford sent a delegate to the General Assembly. The County, however, must have been in existence earlier since there is a record of the Stafford County Court Book which on page one relates to a meeting of the Court for the County on May 27, 1664.[15] The boundaries of the County are nowhere set forth at this early date, but that they encompassed the Arlington area is clear from a direction of the Legislature in 1676 that a fort be established "on Potomack river at or near John Mathews in the county of Stafford."[16] John Mathews' land was on the lower side of Great Hunting Creek[17] but there would have been no reason at that time to erect a separate county to the north.

There were no further changes affecting the county within which Arlington lay until 1730 when Prince William County was formed. An Act of the General Assembly declared that after March 25, 1731,

"all the land, on the heads of the said counties [Stafford and King George] above the Chopawansick Creek, on Patomack river, and Deep run, on Rappahannock river and a southward line to be made from the head of the north branch of the said creek to the head of the said Deep run, be divided and exempt from said counties … and be made a distinct county, and shall be called and known by the name of Prince William County."[18]

It was not many years until Fairfax County came into being:

"… from and immediately after the first day of December now next ensuing, the said county of Prince William be divided into two counties: That is to say, all that part thereof, lying on the south side of Occoquan, and Bull Run; and from the head of the main branch of Bull Run, by a straight course to the Thoroughfare of the Blue Ridge of mountains, known by the name of Ashby's Gap or Bent, shall be one distinct county, and retain the name of Prince William County: And be one distinct parish, and retain the name of Hamilton parish. And all that other part thereof, consisting of the parish of Truro, shall be one other distinct county, and called and known by the name of Fairfax county...."[19]

Thus from December 1742 until the District of Columbia was formally organized by Act of Congress (February 27, 1801) what is now Arlington was part of Fairfax County.

1789-1847

Maryland and Virginia had agreed to meet in 1785 to discuss the controversy over the navigation of the Potomac and their joint boundary. The Commissioners who took part in this meeting did more than draw up a compact subsequently ratified by their respective States. From this meeting eventually came the call for the convention which resulted in the Constitution of the United States and the decision to set aside a tract of land ten miles square for the seat of the Federal Government.

The Maryland-Virginia compact on the Potomac was signed on March 28, 1785, and confirmed by the General Assembly of Virginia in 1786.[20] Although it was designed primarily to settle navigation and fishing rights, its seventh section provided: "The citizens of each State, respectively, shall have full property rights in the shores of Patowmack river adjoining their land...." This has been interpreted to mean property rights to low water mark. The dispute over this point became of significance in the 20th Century with the construction of the National Airport and the Pentagon Building.

Article I, Section 8, of the Constitution of the United States gives the Congress power to accept a territory not exceeding ten miles square to be set aside as the seat of the Federal Government. The story of the compromise which led to the selection of a site on the Potomac is told in all the history books.[21] These, however, rarely give the details of how the exact area which became the District of Columbia came to be chosen.

In 1789, the Virginia legislature adopted an Act[22] offering to cede "ten miles square, or any lesser Quantity of Territory within the State" to the United States for the permanent seat of the general government. Section I of this Act recited the motive: "Whereas the equal and common benefits resulting from the administration of the general government will be best diffused, and its operation become more prompt and certain, by establishing such a situation for the seat of the said government, as will be most central and convenient to the citizens of the United States at large, having regard as well to population, extent of territory, and a free navigation to the Atlantic Ocean, through the Chesapeake bay, as to the most direct and ready communication with our fellow citizens in the western frontier; and whereas it appears to this Assembly that a situation combining all considerations and advantages before recited, may be had on the banks of the river Patowmack, above tide water, in a country rich and fertile in soil, healthy and salubrious in climate, and abounding in all the necessaries and conveniences of life, where in a location of ten miles square, if the wisdom of Congress shall so direct, the States of Pennsylvania, Maryland, and Virginia may participate in such location."

It is clear from the inclusion of Pennsylvania as one of the participating States, and the reference to "above tide water" that the Virginia legislators of those days had in mind a tract somewhat higher up the river than that which was eventually chosen. Indeed, the first Act of Congress[23] dealing with this subject set the limits within which the Federal District was to be established "on the river Potomac, at some place between the mouths of the Eastern Branch and Connogochegue" (a tributary of the Potomac some 20 miles south of the Pennsylvania State line) and authorized the President to appoint three commissioners to survey and "by proper metes and bounds" define and limit the district to be accepted by the Congress.

By a proclamation of January 24, 1791,[24] President Washington directed that a survey should be made.

"… after duly examining and weighing the advantages and disadvantages of the several situations within the limits aforesaid, I do hereby declare and make known that the location of one part of the said district of 10 miles square shall be found by running four lines of experiment in the following manner, that is to say: Running from the court-house of Alexandria, in Virginia, due southwest half a mile, and thence a due southeast course till it shall strike Hunting Creek, to fix the beginning of the said four lines of experiment.

"Then beginning the first of the said four lines of experiment at the point on Hunting Creek where the said southeast course shall have struck the same, and running to the said first line due northwest 10 miles; thence the second line into Maryland due northeast 10 miles; thence the third line due southeast 10 miles, and thence the fourth line due southwest 10 miles to the beginning on Hunting Creek."

Since the tract thus specified did not lie within the limits set by the Act of July 1790, the Congress was asked to authorize the moving of the southern boundary point of the "ten miles square" farther south to include the Eastern Branch and the town of Alexandria. Accordingly, the Act of July 16, 1790, was amended by an Act approved March 3, 1791:

"… it shall be lawful for the President to make any part of the territory below the said limit [the confluence of the Eastern Branch with the Potomac] and above the mouth of Hunting Creek, a part of said district, so as to include a convenient part of the Eastern Branch, and of the lands lying on the lower side thereof and also the town of Alexandria...."

No time was lost in establishing definite boundaries for the new district, and on March 30, 1791, President Washington issued a proclamation declaring

"that the whole of the said territory shall be located and included within the four lines following, that is to say:

"Beginning at Jones's Point, being the upper cape of Hunting Creek, in Virginia, and at an angle in the outset of 45 degrees west of the north, and running in a direct line 10 miles for the first line; then beginning again at the same Jones's Point and running another direct line at a right angle with the first across the Potomac 10 miles for the second line; then from the termination of the said first and second lines running two other direct lines of 10 miles each, the one crossing the Eastern Branch aforesaid and the other the Potomac, and meeting each other in a point.

"… and the territory so to be located, defined, and limited shall be the whole territory accepted by the said acts of Congress as the district for the permanent seat of the Government of the United States."[25]

The cornerstone was set at Jones Point, on the bank of the Potomac below Alexandria, on April 15, 1791. Many of the original stones, set at intervals of one mile along the boundary, are still in place though badly showing the effects of time.[26] The stone referred to earlier—at the northwest corner of present Arlington County—is chipped and almost overgrown by the great oak tree near which it was placed. A small tract surround this stone has been set aside as a public park, jointly owned by the City of Falls Church and the counties of Arlington and Fairfax.

It is interesting that the Acts of Congress setting up the District of Columbia should have specified that no public buildings were to be erected on the Virginia side of the Potomac.[27] The Act of 1790 empowered the commissioners to buy or accept the gift of land for the site of public buildings only on the eastern side of the Potomac. The Act of 1791 made this limitation more explicit:

"… nothing herein contained, shall authorize the erection of public buildings otherwise than on the Maryland side of the river Potomac."

It is curious that this should have been so since the General Assembly of Virginia in 1789 followed its Act ceding territory for the formation of a Federal District by a joint resolution promising to appropriate not less than $120,000 (a considerable sum in those days) for public buildings in this territory if Maryland would put up an amount not less than three-fifths as much. The fact that there were no Federal office buildings on the Virginia side of the Potomac was used as an argument for the retrocession of this area in mid-19th Century.

The compromise which had resulted in the selection of the Potomac as the site of the Federal District included an agreement that the seat of the Government should be in Philadelphia for a period of ten years. Accordingly, it was not until 1800 that the Congress and Government offices were moved to the City of Washington in the District of Columbia.

Almost from the beginning there was dissatisfaction among the inhabitants of Alexandria County at being part of the District of Columbia. This sentiment crystallized in 1846 when the General Assembly adopted an Act[28] expressing the willingness of Virginia to accept the territory should the Congress re-cede it. A petition was presented to the Congress by the residents requesting that this be done. The petition was referred to the Committee on the District which reported:

"The experience of more than forty years seems to have demonstrated that the cession of the county and town of Alexandria was unnecessary for any of the purposes of a seat of government, mischievous to the interests of the State at large, and especially injurious to the people of that portion which was ceded by Virginia."[29]

Accordingly, a bill was introduced to turn back to Virginia the area ceded by it in 1789. After considerable debate as to its constitutionality, the bill was enacted on July 9, 1846. It stipulated that the retrocession should be contingent upon a referendum among the people of the area in question. The referendum was held[30] and the vote was 763 for and 222 against retrocession.

On September 7, 1846, President Polk announced the results of the referendum and called "upon all and singular the persons whom it doth or may concern to take notice that the act aforesaid [of July 9, 1846] 'is in full force and effect.'"[31] It was not until the next year, however, that Virginia got around to extending its jurisdiction over the "county of Alexandria." On March 13, 1847, "An Act to extend the jurisdiction of the Commonwealth of Virginia over the county of Alexandria" was passed. It stated:

"… The territory comprising the county of Alexandria in the District of Columbia heretofore ceded by this Commonwealth to the United States and by an Act of Congress of July 9, 1846, retroceded to Virginia and by it accepted shall be an integral portion of the Commonwealth."

The Act provided that after March 20, 1847, the laws of Virginia were to be in force in this territory, and went on:

"That the territory so retroceded and accepted, comprising the county of Alexandria, shall constitute a new county, retaining the name of the county of Alexandria, the court- house whereof shall be in the Town of Alexandria where the courts now sit...."[32]

Tentative efforts have been made from time to time to re- annex this area to the District of Columbia. It was on one such occasion, in 1865, that a "Remonstrance of the Mayor and Citizens of Alexandria against the Bill to annex the city and county of Alexandria to the District of Columbia" concluded that "Annexation to the District at this time is repugnant to the feelings and wishes and would be ruinous to the interests of the people of Alexandria."

Arlington's Boundary with the City of Alexandria

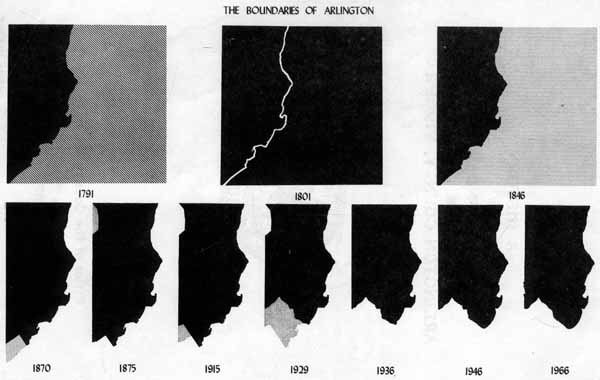

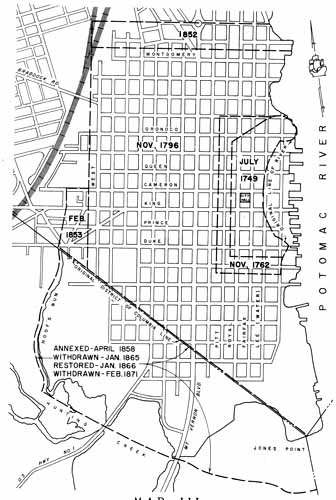

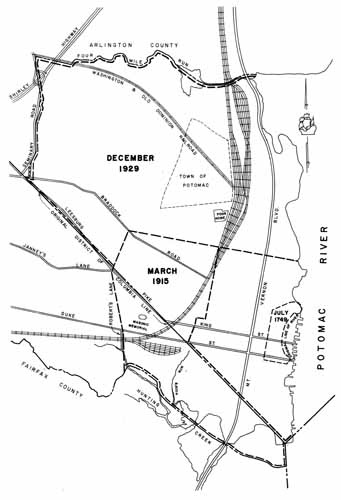

Until 1870, Alexandria, first as a Town and, after 1852 as a City, was geographically part of the County of Alexandria. However, its boundaries must be considered from the beginning because all Acts extending the area of the Town were made in reference to the pre-existing limits. It is impossible to comprehend the effect of any given change without tracing the boundaries back to—or forward from—the beginning. (Map III.)

MAP III

Boundaries of the Town and City of Alexandria 1749 to 1915

Drafted by W.B. Allison and B. Sims

In 1748, a charter was issued to a group of trustees to establish a Town

"covering 60 acres of land, parcel of the lands of Philip Alexander, John Alexander, and Hugh West, situate, lying and being on the south side of Potomac River about the mouth of Great Hunting Creek and in the county of Fairfax … beginning at the mouth of the first branch above the warehouse, and extending down the meanders of the said River Potomac to a point called Middle Point, and thence down the said river ten poles; and from thence by a line parallel to the dividing line between John Alexander's land and Philip Alexander, and back into the woods for the quantity aforesaid."[33]

The land was surveyed and lots sold by auction in July 1749. A map with a notation of the purchasers was made by George Washington,[34] at that time a boy of seventeen. On the north, the lots lay along the north side of Oronoco Street, one block below Water Street (later Lee; at that time it was interrupted between Queen and King Streets by the shore line of the River), and on the south, lots were laid off on the south side of Duke Street. The Potomac with its bend between Oronoco and the south side of Prince Street, formed the eastern boundary, while the western was a line of lots on the west side of Royal Street. There were 84 lots in all, four to a block for the most part except for the northwest portion where a stream, rising on Pitt Street between Cameron and Queen, drained into the Potomac north of Oronoco Street. This is the "first branch above the warehouse" referred to in the charter.

The first increment came in 1762 when the General Assembly passed "An Act for enlarging the town of Alexandria in the county of Fairfax."[35] On the ground that all of the lots included within the bounds of the town had been built on except for some lying in low wet marsh, this Act included in Alexandria the

"… lands of Baldwin Dade, Sibel West, John Alexander the elder and John Alexander the younger which lie contiguous to the said town … beginning at the corner of the lot denoted in the plan of said town by the figures 77 [at the south side of Duke St., three lots from its intersection with Water (Lee) Street] on the said river Potowmack, at the lower end of the said town, and to extend thence down the said river the breadth of two half acres, and one street thence back into the fields, by a line parallel to the lower line of the said town, such a distance as to include ten half acre lots and four streets; thence by a line parallel with the present back line of the said town to the extent of seventeen half acre lots and eight streets, and from thence by a line at right angles with the last to the river."

Until 1779 the Town of Alexandria had had no formal government, being managed by a Board of Trustees whose interest was primarily in the sale of land. In that year, however, the Town was incorporated by the General Assembly with provision for a Mayor, Council, and other officials. The charter[36] made no mention of boundaries except to give the town authorities jurisdiction over the territory within a half mile of the town limits. Another Act[37] adopted at the same session stated that lots had been laid off by John Alexander adjacent to the town in 1774 and sold with the stipulation that they be built on within two years. Because of the difficulty of obtaining building materials due to wartime conditions not all the purchasers had been able to meet this requirement. The Act extended the period within which building on these lots was required to two years

"after the end of the present war … and the same are hereby annexed to and made part of the said town of Alexandria."

The width and direction of the streets to be laid off in the area surrounding the Town was regulated by an Act of 1785,[38] but this did not extend the actual town limits. The area affected was described as:

"Beginning at Great Hunting Creek and running parallel with Fairfax street to four mile run or creek so as to intersect King street when extended one mile west of the courthouse, thence eastwardly down the said creek or run to its confluence with the Potomac river, thence southwardly down the said river to the mouth of Great Hunting Creek...."

In the next year, however, the Legislature provided

"That the limits of the town of Alexandria shall extend to and include as well the lots formerly composing the said town, as those adjoining thereto which have been and are improved."[39]

The town was still growing, and ten years later the General Assembly again extended its legal limits.

"Whereas several additions of lots contiguous to the town of Alexandria have been laid off by the proprietors of the land in lots of half an acre each extending to the north that range of lots upon the north side of a street called Montgomery; upon the south, to the line of the District of Columbia [this line had been surveyed but Alexandria had not yet been incorporated in the District] upon the west, to a range of lots upon the west side of West street, and upon the east to the river Patowmac; that many of the lots in those additions have already been built upon, and many more will so be improved; and whereas it has been represented to the General Assembly that the inhabitants residing on said lots are not subject to the regulations made and established for the orderly government of the town and for the preservation of the health of the inhabitants, by the prevention and removal of nuisances, upon which their property and well being does very much depend:

"1. Be it Therefore Enacted: That each and every lot or part of a lot within the aforesaid limits, on which at this time is built a dwelling house of at least 16 feet square, or equal thereto in size, with a brick or stone chimney and that each and every lot within said limits which shall hereafter be so built upon, shall be incorporated with the said town of Alexandria and considered as part thereof."[40]

The following year this Act was amended[41] to include unimproved lots since their development was being hindered by the exclusion. These were the boundaries of the Town when it became part of the District of Columbia. They remained unchanged for nearly half a century thereafter. The charter for the town adopted by the Congress on February 25, 1804,[42] specified that the limits should be those prescribed by the Acts of Virginia. The jurisdiction of the town officials, however, was extended to the

"house lately built in the vicinity of the town for the accommodation of the poor and others"

and over the ten acres of ground surrounding the poor house. This is at what is now Monroe Street and Jefferson Davis Highway. Although the Charter was amended several times while Alexandria was in the District, no changes were made in the Town boundaries.

After the retrocession of "the county and town of Alexandria" (v.s., p. 13) not only were the boundaries changed, but the Town was chartered as a City. Section 22 of the new charter[43] provided:

"The line of the City of Alexandria shall be extended on the north and west as follows: Beginning in the Potomac River at a point distant northerly in the direction of Fairfax Street four hundred nineteen feet and two inches from the north line of the present corporate limits of the town of Alexandria in said river, and running thence westerly, parallel with said north line, to a point at which it would intersect the present western line if extended north four hundred nineteen feet and ten inches; thence southwesterly with the present western line but the said city council shall have authority to make such police and sanitary regulations of the territory reaching ten feet west of the western bank of Hooff's or Mushpot Run; then parallel to and at that distance from said run to the line dividing Alexandria from Fairfax county; then southeasterly with said dividing line to the present southwest corner of the said town of Alexandria."

The next year the Charter was amended,[44] again altering the boundaries:

"Beginning in the Potomac river at a point distant northwardly in the direction of Fairfax street four hundred and nineteen feet and two inches from the present north line of the corporate limits of the town in said river, and running westerly parallel to said north line to intersect the west line of said limits produced northwardly four hundred and nineteen feet and two inches; thence southwardly with said west line produced to the northwest corner of the said limits; thence eastwardly with the said north line into the river; then northwardly to the beginning: Beginning again at the intersection of the northwestern line of said limits with the north line of Cameron street; then southwardly with said western line, to the county line; then northwardly with the county line to the point where it intersects the brick wall on the south side of the Little River Turnpike road; then northwardly by a straight line to the east corner of John Hooff's lot on the south side of King street extended; then crossing King street extended to the west corner of the lot of the late Col. Francis Peyton; then with the west line of said lot and the course thereof to the north line of Cameron street extended; then by a straight line to the beginning."

The next addition came in 1858[45] when the boundaries were described as:

"Beginning in the Potomac River, at a point distant northerly, in the direction of Fairfax Street five hundred and ninety five feet and nine inches from the north line of Montgomery street, as now established in said city, and extended into said river; and running thence westerly and parallel with said north line to a point at which this course will intersect a line one hundred twenty three feet and five inches west of and running parallel to the western line of West street as now established, when extended; thence southerly parallel with West street, to the north line of Cameron street as now established; thence westerly in the direction of the north line of Cameron street extended, to a point in a line with the west line of the lot of the late Francis Peyton, on which he resided; thence southerly, parallel with West street, to the south line of King street, extended; thence in a straight line to a point in the line dividing the county of Fairfax and Alexandria from each other, ten feet west of Hoof's Run; thence southerly, parallel to, and distant 10 feet from Hoof's Run to the middle of Hunting Creek thence with the middle of Hunting Creek into the Potomac River; then up the said river to the beginning."

This line remained in effect until January 27, 1865, when an amendment to the charter[46] withdrew from the jurisdiction of the city all the territory in Fairfax county (bounded by the old District line, Hooff's Run and Hunting Creek) which had been added to the town by the charter of 1858. The next year, on January 25, 1866, the General Assembly rescinded this action and restored the boundaries of 1858.[47] A further change occurred in this area on February 20, 1871, when the last part of the description was changed to read:

"… to a point in the line dividing the county of Fairfax and Alexandria from each other, ten feet west of Hooff's Run; thence southerly with the said line into the Potomac River; thence up said river to the beginning."[48]

A major change occurred on May 1, 1870, when the City of Alexandria was excluded from the County. This came about through the implementation of an Act of the Assembly[49] following the adoption of a new Virginia Constitution in 1869. In delineating the magisterial districts into which counties were to be divided it was provided that "no part of any town or city having a separate organization, or a population of five thousand or more inhabitants, shall be embraced." Alexandria was such a city and thereafter was independent of as well as outside of the County.

MAP IV

Areas Annexed by the City of Alexandria in 1915 and 1929

Drafted by W. B. Allison and B. Sims

There were no further legislative changes in the boundaries of the City of Alexandria after 1871. In 1915, however, the Supreme Court of Appeals of Virginia, reversed a decision of the Circuit Court of Alexandria County given on January 13, 1913. The City Council of Alexandria had sought to annex adjoining territory from both Fairfax and Alexandria counties and had been opposed by the authorities of those counties who had been upheld by the Circuit Court. The Order of the Supreme Court of Appeals[50] transferred 866 acres from Arlington and 450 acres from Fairfax to Alexandria.

This annexation took effect on April 1, 1915. Once more thereafter Arlington County—as it became known after 1920[51]—was to lose territory to the City of Alexandria. This was in 1929 when a decision of the Supreme Court of Appeals[52] rendered May 4, 1929, found in favor of the City of Alexandria which had begun annexation proceedings in December 1927.

The Court held that "it is necessary and expedient that the corporate limits of the City of Alexandria should be extended" and that "the territory to be annexed from Arlington County is a reasonably compact body of land and contains no land which is not adapted to city improvement, and the Court being also of the opinion that no land is included which the City will not need in the reasonably near future for development …"

The Court ordered the annexation[53] to take effect on December 31, 1929. The line thus established remained in effect until January 1, 1966.

This was the last annexation of territory from Arlington County. A special provision of the Act[54] establishing the County Manager plan of government, adopted by Arlington in 1930, effective January 1, 1932, prevents the annexation of any part of the County (but permits annexation of the entire County after referendum). In 1938, as a further precaution, the legislative delegation representing Arlington County succeeded in having the General Assembly enact a law[55] which prohibits the annexation of territory from any county which would result in reducing the area of that county to less than 60 square miles of highland. Since Arlington has less than 26 square miles, this Act effectively checks any further such encroachments upon its territory.

Development on both sides of the 1929 boundary line, construction of streets and notably of the Henry G. Shirley Memorial Highway—and especially changes in the channel of Four Mile Run—eventually brought dissatisfaction with that line. In 1962, the Arlington and Alexandria legislative delegations secured enactment by the General Assembly of an Act[56] permitting an adjustment in the boundary to be concluded by mutual agreement between the governing bodies of the County and the City, the agreement to be recorded in the Clerk's Office of both jurisdictions.

Negotiations began after the area affected had been surveyed and the private property which might be the subject of exchange had been appraised. Impetus was given by the need of Arlington for land in connection with enlargement of the County sewage treatment facilities; this land, although on the North side of Four Mile Run fell in Alexandria. Finally, the Arlington County Board gave approval in principle to a draft proposal on April 10, 1965,[57] and on April 13, 1965, the Alexandria City Council followed suit. A public hearing was held on May 5, 1965, but final action was deferred pending refinement of the proposal. In December 1965, the final agreement was recorded[58] and the transfer of certain publicly owned property approved by the Circuit Court. The net gain to Arlington's area was 167 acres.

This procedure for rectifying boundaries between a County and a City is highly unusual in the Virginia experience.

Arlington's Boundary with the District of Columbia

No definite effort was made at the time of the recession of Alexandria County to Virginia to draw a boundary line between the County and the remaining portion of the District of Columbia. As noted above, the various acts bringing about the recession referred only to "the territory heretofore ceded by the Commonwealth of Virginia." The actual boundary was of small moment at the time.

Toward the end of the 19th Century, however, the United States Government acquired lands on the Virginia shore of the Potomac largely through the purchase of the Arlington estate. As the 20th Century progressed, roads (notably the Mount Vernon Boulevard and later the George Washington Memorial Parkway) were constructed, bridges and bridge approaches built and, eventually, the Federal Government undertook to construct the National Airport at Gravelly Point below Alexander's Island. A suit[59] over government activity in making a land fill raised questions as to the exact location of the boundary—and indeed as to whether Alexander's Island really was an island or was a peninsula. This case, decided by the U.S. Supreme Court on May 4, 1931, set the boundary line between the District of Columbia and Virginia at the high water mark of the Potomac on the Virginia shore as it existed in 1791.

But where had that high water mark been? There had been no survey at the time; the shore line had never been marked; and even had it been, the passage of time had made many changes in the river front.[60] A Commission was established[61]to deal with this question. The instructions to this Commission were to take into consideration the decisions of the Supreme Court of the United States, the findings and report of the Maryland-Virginia Commission of 1877[62] and the Maryland-Virginia compact of 1785.[63]

The Commission accumulated a large volume of testimony and exhibits and completed its report[64] in 1935. It found that the "fair and proper boundary is the low water mark on the Virginia shore running from headland to headland across creeks and inlets." It pointed out that inasmuch as the mark of 1791 could not be determined the low water mark should be accepted as of this day. It suggested that an exception be made at Roaches Run where the line should run 150 feet west of and parallel to the west line of the Mount Vernon Boulevard.

Several bills[65] were introduced into Congress to give effect to the decision of the Commission but none was enacted at this time. The completion of the Airport and the Pentagon Building gave urgency to the problem: conflicts of jurisdiction hampered law enforcement and complicated the question of tax collection. Moreover, Virginia was anxious to insure that the liquor control laws of the State and not those of the District of Columbia should be in effect at the National Airport. In 1942, the General Assembly had adopted an Act[66] covering the boundary question, on the assumption that the bill then pending in Congress would be passed. Disagreement over the details of the jurisdiction to be ceded and accepted by Virginia and the United States Government prevented passage of a Federal Act until 1945 when Public Law 208 was enacted by the 79th Congress. This was followed by an Act[67] of the Virginia General Assembly repealing the 1942 Act and ratifying the 1945 Federal Act.

This law is in effect today. It provides that the boundary line

"shall begin at a point where the northwest boundary of the District of Columbia intercepts the high-water mark of the Virginia shore of the Potomac River and following the present mean high-water mark; thence in a southeasterly direction along the Virginia shore of the Potomac River to Little River, along the Virginia shore of Little River to Boundary Channel, along the Virginia side of Boundary Channel to the main body of the Potomac River, along the Virginia side of the Potomac River across the mouths of all tributaries affected by the tides of the river to Second Street, Alexandria, Virginia, from Second Street to the present established pierhead line, and following said pierhead line to its connection with the District of Columbia-Maryland boundary line; that whenever said mean high-watermark on the Virginia shore is altered by artificial fill and excavations made by the United States, or by alluvion or erosion, then the boundary shall follow the new mean high-water mark on the Virginia shore as altered, or whenever the location of the pierhead line along the Alexandria water front is altered, then the boundary shall follow the new location of the pierhead line."

The Act also provided that all the land on the Virginia side of the Potomac lying between the boundary line as now adopted and the mean high water mark as it existed on January 24, 1791 (wherever that was!) should be ceded to the State of Virginia. The United States, however, reserved concurrent jurisdiction over this area.

Here the matter rests very uneasily today. The exact line was surveyed, monumented, and mapped by the U.S. Coast and Geodetic Survey over the years 1946-1947.[68] However, the working agreements reached by the law enforcement officials of the various jurisdictions concerned have not always proven satisfactory. The long history of the location of the Potomac River boundary of Arlington County cannot yet be said to have reached its end.

Postscript—Towns in Arlington County

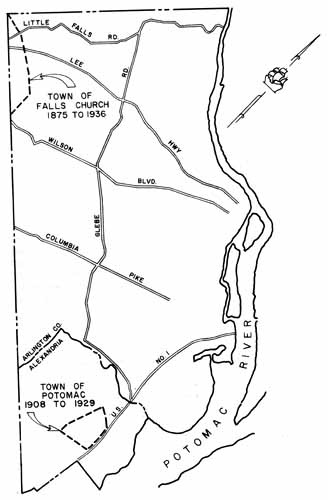

Of the three towns which have lain within Arlington County, the only one whose limits have been of importance to the territorial extent of the County is Alexandria. Nonetheless, to complete the record, some mention should be made of the Town of Potomac and the Town of Falls Church, the first of which lay wholly within Arlington, and the second, partly so.

Falls Church is the older town. It was chartered by the General Assembly on March 30, 1875.[69] The charter set forth the boundaries as:

"Beginning at the corner of Alexandria and Fairfax Counties on J. C. DePutron's farm; thence to the corner of W. H. Ellison and Koon [sic] on D. H. Barrett's line; thence to the corner of Sewell and Hollidge, on the new cut road; thence to the corner of J. E. Birch and H. J. England, on the Falls Church and Fairfax Courthouse road; thence to a stone in the road being a corner of B. F. Shreve, Newton, and others; thence to the crossing of the Alexandria and Georgetown roads at Taylor's corners; thence along the line of said Georgetown road to the corner of Samuel Shreve and John Febrey; thence to a pin oak tree near Dr. L. E. Gott's spring; thence to the northeast corner of John Brown's barn; thence to the crossing of Isaac Crossmun's and Bowen's line on the Chain Bridge Road; thence to the place of beginning."

MAP V

The Towns of Falls Church and Potomac in Arlington County

Drafted by W. B. Allison and B. Sims

After Arlington adopted the County Manager form of government, the residents of so much of the Town of Falls Church as lay within Arlington County (Map V) sought to have the charter amended to reduce the limits of the Town to that portion which lay in Fairfax. An action was brought on July 7, 1932, and the Circuit Court granted the petition on January 17, 1935.[70] This decision was appealed, however, and it was not until the next year (April 30, 1936) that the order went into effect,[71] after the lower court had been upheld by the Virginia Supreme Court of Appeals.

The area affected by the order is described as:

"Beginning at a large planted stone on the estate of the late J. C. DePutron, at the original western corner of the District of Columbia, which is also at the corner of Fairfax and Arlington counties, and at the corner of the Town of Falls Church; thence with the boundary of said Town S. 83° 155′ E. 2,404 feet more or less, to a planted stone in the center of Little Falls Street also called the Chain Bridge Road, at a point at which said street is intersected by the boundary of the land formerly known as the Bowen tract; thence with the boundary of said Town S. 49° 15′ E. 3,482 feet, more or less, to a planted granite stone at a point which formerly marked the northeast corner of John Brown's barn; thence with the boundary of said Town S. 28° 45′ E. 2,410 feet, more or less, to a point at which there formerly stood a large pin oak on the Gott tract; thence with the boundary of the said Town S. 4° 15′ W. to the boundary between Fairfax and Arlington counties; thence with the said boundary in a northwesterly direction to the place of beginning."

The Town of Potomac was chartered by the General Assembly in 1908.[72] Its boundaries (Map V) were described as:

"Beginning at the north intersection of Bellefont Avenue in the subdivision of 'Del Ray' with the Washington and Alexandria Turnpike, thence northerly along the west line of the Turnpike to the old Georgetown Road, the northern boundary of the subdivision of St. Elmo; thence westerly along the south side of the Georgetown Road to the dividing line of Susan P. A. Calvert and Charles E. Wood; thence with the line of Calvert and Wood to the west line of the Washington, Alexandria and Mt. Vernon R.R. Co., to its intersection with Lloyd's Lane and Bellefont Avenue to the beginning."

All this area was included in the annexation to Alexandria which was effected in 1929 (cf. p. 23).

One proposed town deserves mention. In 1920 a group of citizens petitioned the Circuit Court for a town charter for Clarendon. The Court denied the petition. Upon appeal, the Supreme Court of Appeals of Virginia upheld the lower court, declaring that all of Arlington County was a "continuous, contiguous, and homogeneous community" and as such should not be subjected to subdivision for the purpose of incorporating a town.[73] Since Arlington is even more a "continuous, contiguous, and homogeneous" community than it was in 1922 there is no prospect that ever again will there be a town within the bounds of the County.

APPENDIX

Annexation of 1915

Text of the order of the Supreme Court of Appeals setting the area to be annexed by Alexandria as of April 1, 1915:

"1st. That the following territory in Fairfax County be, and the same is hereby annexed to the City of Alexandria, to wit:—Beginning at a point in mid-channel of Hunting Creek southward of Alexandria Water Company's pumping station with the east side of a lane, called Robert's Lane; running thence northwardly with the east line of said Lane, extended, and with the east line of said Lane to the south side of the Little River Turnpike; thence across the Little River Turnpike in the same direction to the extreme west corner of Shooter's Hill section of George Washington Park sub-division; thence with the west boundary of said Shooter's Hill section to the corner of said Shooter's Hill section and Section No. 2 of said sub- division; thence with the west boundary of said Section No. 2 of said sub-division to a point on the south side of Janney's Road fifty (50) feet west from the intersection of the south side of Janney's Road and the west side of the Leesburg Turnpike; thence continuing to about 25 degrees east to the old District of Columbia line, being the dividing line between said Fairfax County and Alexandria County; and thence southwestwardly with the said old District line to Jones Point on the Potomac River; thence southwardly down the said River to the mid-channel of Hunting Creek: thence with the meanderings of the mid- channel of Hunting Creek up stream, to the point of beginning.... 2nd. That the following described territory in Alexandria County be, and the same is, hereby annexed to the City of Alexandria: Beginning at the northwest corner of the present city boundary, and extended said line westwardly, in the same course until it intersects with the north side of the Braddock Road; thence southwardly, to the Old District line at the northwest corner of the land annexed from Fairfax County; thence with the said old District line southeastwardly to the southwest corner of the present city boundary about twenty feet west of Hooff's Run; thence following the western boundary line of the present city to the northwest corner of the present boundary line of the city and the point of beginning.... And it is further ordered that the boundary lines of the City of Alexandria after annexation shall be as follows: Beginning in the Potomac River at the northeast corner of the present boundary of the City of Alexandria and following the present north boundary line of the City of Alexandria to the northwest corner of the City, thence prolonging said line in the same direction until it intersects with the north side of the Braddock Road; then southwardly to a point on the south side of Janney's Lane fifty (50) feet from the west side of Leesburg Turnpike; thence southwardly along the west boundary line of George Washington Park subdivision to the Alexandria Water Company property and reservoir; thence southwardly with the west line of Alexandria Water Company's property to the north side of the Little River Turnpike; thence across the Little River Turnpike and with the east side of Robert's Lane and continuing with the east side of Robert's Lane extended to the mid-channel of Hunting Creek; thence downstream with the meandering of the mid-channel of Hunting Creek to the Potomac River, thence up the Potomac River to Jones Point and thence with the west side of the Potomac River to the point of beginning, the northeast corner of the present boundary of the City of Alexandria."

Annexation of 1929

Text of the order of the Supreme Court of Appeals setting the area to be annexed by Alexandria as of December 31, 1929:

"Beginning at the intersection of the north corporate limits of Alexandria Virginia with the west shore of the Potomac River, thence extending N. 80° 39′ W. along said north boundary line to the northwest corner of the corporate limits as the same was established prior to the year 1915; thence with the line as established March 22, 1915, and continuing said north corporate line N. 80° 39′ W., 4,353.86 feet to a set stone at the corner on the north side of the Braddock Road within the subdivision of Northwest Alexandria; thence S. 30° 11′ W., 1,892.20 feet to the intersection with the line separating Fairfax and Arlington Counties; thence with the line of said two counties N. 45° 02′ 50″ W., 6,434.88 feet to a point in the center line of the Braddock Road (having passed over an original milestone in said county line at 3,244.70 feet); thence following along the center line of said Braddock Road, S. 84° 22′ 30″ E., 264.20 feet to a point where said Braddock Road is intersected by the southwardly projection of the Seminary Road: thence departing from said Braddock Road and following along the center line of said Seminary Road the following courses: N. 5° 02′ 30″ E. 811.50 feet, N. 22° 46′ 30″ E. 611.05 feet, N. 1° 23′ W., 1,551.40 feet, N. 20° 03′ E. 319.13 feet, N. 19° 48′ E. 385.49 feet, N. 37° 45′ W. 183.32 feet, N. 2° 57′ E. 140.89 feet, N. 28° 00′ E. 165.41 feet, N. 5° 59′ E., 145.83 feet N. 13° 47′ W. 436.37 feet, N. 9° 02′ W. 1,447.08 feet, and N. 2° 10′ 30″ E. 274.90 feet to the point where said center line of said Seminary Road intersects the south right-of-way line of the Washington and Old Dominion Railway; thence with said south right-of-way line S. 77° 39′ 30″ E., 1885.80 more or less, to the center line of the channel of Four Mile Run; thence down the mid-channel line of said Four Mile Run following the meanderings thereof as the same passes under the Washington Virginia Railway (now the Mount Vernon, Alexandria and Washington Railway) the Washington and Alexandria Road, and extending to the intersection of the said Run with the Potomac River; thence following along the west shore line of said Potomac River southwardly to the point of beginning."

Boundary Adjustment 1966

Text of the description of the new Arlington-Alexandria boundary in effect on January 1, 1966, by mutual agreement:

"A line beginning at a point on the common boundary between Fairfax County and the City of Alexandria, Virginia, said point being in the existing right of way of Route #7 and is further defined as point #134 having Virginia State Coordinates of N. 431,495.42 and E. 2,395,581.64 as shown on a map recorded with a deed of annexation in Deed Book 332, page 559, of the land records of the City of Alexandria, Virginia; thence running along said common boundary N. 55° 50′ 10″ E., 69.09 feet to the boundary corner #135 whose coordinates are N. 431,534.22 and E. 2,395,638.81, said point #135 also being shown on the aforementioned boundary map; thence still running with the last mentioned course and across Route #7 1.29 feet (70.38 feet in all) to a point having coordinates N. 431,534.94 and E. 2,395,639.88; thence running N. 09° 13′ 10″ E. 0.69 feet to a point lying on the northerly side of Route #7, 40 feet from same and having coordinates N. 431,535.62 and E. 2,395,639.99; thence running along the northerly side of Route #7 S. 66° 38′ 20″ E., 96.13 feet to a point of curvature whose coordinates are N. 431,497.50 and E. 2,395,728.24 thence continuing with said northerly side of Route #7 and its extension and following the arc of a curve to the right whose radius is 2331.83 feet and whose chord and chord bearing are 810.17 feet and S. 56° 38′ 05″ E. respectively, for an arc distance of 814.30 feet to a point on the extension of the northerly side of 25th Street, and whose coordinates are N. 431,051.93 and E. 2,396,404.88; thence running along said extension and thence with the northerly side of said street N. 50° 54′ 13″ E., 39.53 feet to a point of curvature whose coordinates are N. 431,076.86 and E. 2,396,435.56; thence following the arc of a curve to the right whose radius is 115.60 feet and whose chord and chord bearing are 42.17 feet and N. 61° 24′ 48″ E. respectively, for an arc distance of 42.41 feet to a point of tangency whose coordinates are N. 431,097.04 and E. 2,396,472.59; thence continuing along 25th Street N. 71° 55′ 23″ E. 220.00 feet to a point whose coordinates are N. 431,165.30 and E. 2,396,681.73; thence turning and running across 25th Street and thence along the common boundary between lots #503 and #5 of Section 1 of Claremont Subdivision, and thence across Beauregard Street (its extension into Arlington County being known as S. Walter Reed Drive) S. 18° 04′ 37″ E., 317.80 feet to a point on a curve in the southerly side of Beauregard Street, said point having coordinates N. 430,863.19 and E. 2,396,780.34; thence running along the southerly side of said street and following the arc of a curve to the left whose radius is 410.00 feet and whose chord and chord bearing are 69.89 feet and S. 55° 47′ 34.5″ respectively, for an arc distance of 69.97 feet to a point of tangency having coordinates N. 430,823.90 and E. 2,396,722.54; thence continuing along the southerly side of Beauregard Street and its extension S. 50° 54′ 13″ W. 83.66 feet to a point whose coordinates are N. 430,771.14 and E. 2,396,657.61, said point being 40 feet from the centerline of the previously mentioned Route #7; thence running parallel with but 40 feet from said centerline S. 37° 38′ 20″ E. 572.92 feet to a point whose coordinates are N. 430,317.46 and E. 2,397,007.48, said point being on the extension of the common boundary between Section #1-A of Claremont and Section #2 of Fairlington; thence running along said extension and thence along said common boundary itself N. 44° 19′ 57″ E., 335.55 feet to a point being the northwesterly corner of a parcel of land owned by the City of Alexandria; and having coordinates N. 430,557.48 and E. 2,397,241.97; thence running with the northeasterly boundary of said parcel S. 45° 38′ 10″ E., 242.71 feet to a point on a curve having coordinates N. 430,387.77 and E. 2,397,415.49 and lying in the northerly line of 28th Street; thence running along said northerly line of 28th Street and following the arc of a curve to the right whose radius is 311.48 feet and whose chord and chord bearing are 37.57 feet and S. 64° 02′ 05″ E. respectively, for an arc distance of 37.60 feet to a point of tangency whose coordinates are N. 430,371.32 and E. 2,397,449.27; thence along the northerly side of South Columbus Street S. 60° 34′ 37″ E., 415.05 feet to a point of curvature having coordinates N. 430,167.42 and E. 2,397,810.79; thence running along the arc of a curve to the right whose radius is 215.99 feet and whose chord and chord bearing are 162.40 feet and S. 38° 29′ 37″ E. respectively for an arc distance of 166.50 feet to a point of tangency lying in the intersection of 29th Street and Columbus Street and having coordinates N. 430,040.31 and E. 2,397,911.87; thence running S. 16° 24′ 37″ E. 69.70 feet to a point of curvature on the northeasterly side of Columbus Street and whose coordinates are N. 429,973.45 and E. 2,397,931.56; thence running along the northeasterly side of said street and following the arc of a curve to the left whose radius is 691.20 feet and whose chord and chord bearing are 396.48 feet and S. 33° 04′ 37″ E. respectively, for an arc distance of 402.12 feet to a point of tangency, the coordinates of which are N. 429,641.22 and E. 2,398,147.94; thence running S. 49° 44′ 37″ E. 545.56 feet to a point of curvature whose coordinates are N. 429,288.67 and E. 2,398,564.29; thence following the arc of a curve to the left whose radius is 20.00 feet and whose chord and chord bearing are 21.94 feet and S. 83° 00′ 35.5″ E. respectively, for an arc distance of 23.22 feet to a point of reversed curvature whose coordinates are N. 429,286.00 and E. 2,398,586.07; thence running around the circle of the intersection of Columbus and 30th Streets and following the arc of a curve to the right whose radius is 93.00 feet and whose chord and chord bearing are 177.22 feet and S. 08° 36′ 07″ E. respectively, for an arc distance of 349.54 feet to a point of curvature whose coordinates are N. 429,110.77 and E. 2,398,612.58; thence following the arc of a curve to the left whose radius is 20.00 feet and whose chord and chord bearing are 21.94 feet and S. 65° 48′ 21.5″ W. respectively, for an arc distance of 23.22 feet to a point of tangency on the southeasterly side of 30th Street, said point having coordinates N. 429,101.78 and E. 2,398,592.57; thence running along the southeasterly side of said street S. 32° 32′ 23″ W., 136.28 feet to a point of curvature whose coordinates are N. 428,986.89 and E. 2,398,519.27; thence following the arc of a curve to the left whose radius is 25.00 feet and whose chord and chord bearing are 35.36 feet and S. 12° 27′ 37″ E. respectively, for an arc distance of 39.27 feet to a point on the northeasterly side of Route #7, said point having coordinates N. 428,952.36 and E. 2,398,526.90; thence running S. 57° 27′ 37″ E. 62.54 feet to a point whose coordinates are N. 428,918.72 and E. 2,398,579.62; thence running S. 56° 42′ 37″ E. 713.53 feet to a point of curvature, said point having coordinates N. 428,527.08 and E. 2,399,176.06; thence following the arc of a curve to the right whose radius is 6056.68 feet and whose chord and chord bearing are 1137.63 feet and S. 51° 19′ 17″ E., respectively for an arc distance of 1139.31 feet to a point of tangency on the northeasterly side of Route #7, said point having coordinates N. 427,816.12 and E. 2,400,064.17; thence running along the northeasterly side of Route #7, S. 45° 55′ 57″ E., 2926.68 feet to a point of curvature whose coordinates are N. 425,780.60 and E. 2,402,167.05; thence following the arc of a curve to the left whose radius is 25.00 feet and whose chord and chord bearing are 29.63 feet and S. 82° 16′ 52.5″ E. respectively, for an arc distance of 31.72 feet to a point on the northerly side of Quaker Lane, said point having coordinates of N. 425,776.62 and E. 2,402,196.41; thence following the northerly side of Quaker Lane N. 61° 22′ 12″ E. 25.35 feet to a point of curvature whose coordinates are N. 425,788.77 and E. 2,402,218.66; thence following the arc of a curve to the left whose radius is 880.83 feet and whose chord and chord bearing are 594.59 feet and N. 41° 38′ 39.5″ E. respectively, for an arc distance of 606.50 feet to a point of tangency having coordinates N. 426,233.10 and E. 2,402,613.77; thence turning and running S. 68° 04′ 53″ E. 47.00 feet to a point whose coordinates are N. 426,215.56 and E. 2,402,657.37, said point being on the centerline of Quaker Lane; thence running along the centerline of same N. 21° 55′ 07″ E. 492.76 feet to a point of curvature having coordinates N. 426,672.70 and E. 2,402,841.31; thence following the arc of a curve to the left whose radius is 1200.00 feet and whose chord and chord bearing are 499.27 feet and N. 09° 54′ 42.5″ E. respectively, for an arc distance of 502.94 feet to a point of tangency whose coordinates are N. 427,164.52 and E. 2,402,927.25; thence running N. 02° 05′ 42″ W. 993.05 feet to a point whose coordinates are N. 428,156.91 and E. 2,402,890.95; said point lying in the intersection of Quaker Lane and Crestwood Drive; thence continuing along the centerline of Quaker Lane N. 00° 59′ 42″ W., 201.72 feet to a point of curvature whose coordinates are N. 428,358.60 and E. 2,402,887.45; thence following the arc of a curve to the right whose radius is 595.00 feet and whose chord and chord bearing are 204.00 feet and N. 08° 52′ 33″ E. respectively, for an arc distance of 205.01 feet to a point of tangency having coordinates N. 428,560.16 and E. 2,402,918.93; thence running N. 18° 44′ 48″ E., 122.09 feet to a point of curvature having coordinates N. 428,675.77 and E. 2,402,958.17; thence running along the arc of a curve to the left whose radius is 2181.87 feet and whose chord and chord bearing are 237.27 feet and N. 15° 37′ 47″ E. respectively, for an arc distance of 237.39 feet to a point of tangency having coordinates N. 428,904.27 and E. 2,403,022.10; thence running N. 12° 30′ 46″ E. 88.70 feet to a point of curvature having coordinates N. 428,990.86 and E. 2,403,041.32 and lying in the intersection of Quaker Lane, 32nd Road South, and Preston Road; thence following the arc of a curve to the left whose radius is 243.67 feet and whose chord and chord bearing are 44.38 feet and N. 07° 17′ 14.5″ E. respectively, for an arc distance of 44.44 feet to a point of tangency having coordinates N. 429,034.88 and E. 2,403,046.95; thence running N. 02° 03′ 43″ E. 264.98 feet to a point of curvature whose coordinates are N. 429,299.69 and E. 2,403,056.48 thence still running along the centerline of Quaker Lane and following the arc of a curve to the left whose radius is 2165.91 feet and whose chord and chord bearing are 152.44 feet and N. 00° 02′ 43″ E. respectively for an arc distance of 152.47 feet to a point of tangency having coordinates N. 429,452.13 and E. 2,403,056.60; thence N. 01° 58′ 17″ W., 141.63 feet to a point of curvature having coordinates N. 429,593.68 and E. 2,403,051.73; thence following the arc of a curve to the right whose radius is 4560.67 feet and whose chord and chord bearing are 224.93 feet and N. 00° 33′ 30″ W. respectively for an arc distance of 224.95 feet to a point on the existing Alexandria-Arlington Boundary, said point having coordinates N. 429,818.60 and E. 2,403,049.54; thence running along said existing boundary N. 14° 40′ 33″ W., 307.96 feet to an existing boundary corner with coordinates N. 430,116.51 and E. 2,402,971.52; thence running N. 09° 54′ 36″ W., 1447.14 feet to another existing corner having coordinates N. 431,542.06 and E. 2,402,722.47; thence continuing with said existing Alexandria-Arlington Boundary N. 01° 20′ 15″ E., 271.24 feet to a corner with coordinates N. 431,813.23 and E. 402,728.80, said point being in the vicinity of the Washington and Old Dominion Railroad right of way; thence running S. 78° 26′ 13″ E. 1858.44 feet to an existing boundary corner having coordinates N. 431,440.71 and E. 2,404,549.52; thence continuing with an extension of the last mentioned course 5.73 feet (1864.17 feet in all) to a point whose coordinates are N. 431,439.56 and E. 2,404,555.13; said point lying in Four Mile Run; thence turning and running with the proposed centerline of Four Mile Run N. 20° 30′ 55″ E., 62.07 feet to a point of curvature whose coordinates are N. 431,497.69 and E. 2,404,576.88; thence following the arc of a curve to the right whose radius is 420.44 feet and whose chord and chord bearing are 361.79 feet and N. 45° 59′ 55″ E. respectively, for an arc distance of 374.00 feet to a point of compound curvature having coordinates N. 431,749.02 and E. 2,404,837.12; thence running along the arc of a curve to the right whose radius is 388.90 feet and whose chord and chord bearing are 241.48 feet and N. 89° 34′ 10″ E. respectively for an arc distance of 245.54 feet to a point of tangency whose coordinates are N. 431,750.83 and E. 2,405,078.59 thence continuing along said proposed center and thence with the existing centerline of Four Mile Run S. 72° 20′ 35″ E. 115.13 feet to a point of curvature whose coordinates are N. 431,715.91 and E. 2,405,188.30; thence following the arc of a curve to the left whose radius is 805.00 feet and whose chord and chord bearing are 218.56 feet and S. 80° 08′ 42.5″ E. respectively for an arc distance of 219.24 feet to a point of tangency whose coordinates are N. 431,678.50 and E. 2,405,403.64; thence running S. 87° 56′ 50″ E., 10.38 feet to a point of curvature having coordinates N. 431,678.13 and E. 2,405,414.01; thence following the arc of a curve to the left whose radius is 2864.79 feet and whose chord and chord bearing are 626.25 feet and N. 85° 46′ 40″ E. respectively, for an arc distance of 627.50 feet to a point of tangency whose coordinates are N. 431,724.24 and E. 2,406,038.56; thence continuing along the centerline of said Four Mile Run N. 79° 30′ 10″ E., 571.24 feet to a point of curvature having coordinates N. 431,828.31 and E. 2,406,600.24; thence following the arc of a curve to the right whose radius is 1909.88 feet and whose chord and chord bearing are 500.23 feet and N. 87° 01′ 40″ E., respectively for an arc distance of 501.67 feet to a point of tangency; said point having coordinates N. 431,854.25 and E. 2,407,099.80; thence running S. 85° 26′ 50″ E., 542.38 feet to a point of curvature with coordinates N. 431,811.20 and E. 2,407,640.47; thence following the arc of a curve to the left whose radius is 1432.41 feet and whose chord and chord bearing are 585.03 feet and N. 82° 46′ 10″ E. respectively, for an arc distance of 589.17 feet to a point of tangency having coordinates N. 431,884.83 and E. 2,408,220.85; thence running N. 70° 59′ 10″ E. 28.44 feet to a point of curvature having coordinates of N. 431,894.10 and E. 2,408,247.74; thence following the arc of a curve to the left whose radius is 1318.44 feet and whose chord and chord bearing are 482.64 feet and N. 60° 26′ 22″ E. respectively, for an arc distance of 485.38 feet to a point of tangency having coordinates N. 432,132.21 and E. 2,408,667.56; thence running N. 49° 53′ 34″ E., 4.43 feet to a point whose coordinates are N. 432,135.06 and E. 2,408,670.95; thence running across Mount Vernon Avenue (Arlington Ridge Road in Arlington) and still following the previously mentioned centerline of Four Mile Run N. 71° 20′ 53″ E., 274.92 feet to a point of curvature with coordinates N. 432,222.98 and E. 2,408,931.43; thence running along the arc of a curve to the right whose radius is 315.05 feet and whose chord and chord bearing are 289.48 feet and S. 81° 18′ 07″ E. respectively for an arc distance of 300.28 feet to a point of tangency with coordinates of N. 432,179.20 and E. 2,409,217.58; thence running S. 53° 57′ 07″ E., 314.44 feet to a point whose coordinates are N. 431,994.16 and E. 2,409,471.81; thence still running along said centerline S. 52° 58′ 38″ E., 665.38 feet to a point with coordinates N. 431,593.51 and E. 2,410,003.05; thence S. 61° 35′ 07″ E., 504.49 feet to a point having coordinates N. 431,353.45 and E. 2,410,446.76; thence S. 62° 23′ 28″ E. 1048.27 feet to a point with coordinates N. 430,867.65 and E. 2,411,375.67 and S. 67° 03′ 11″ E., 544.81 feet to a point of curvature, said point having coordinates N. 430,655.24 and E. 2,411,877.37; thence running with the centerline of said Four Mile Run, across Jefferson Davis Highway (Route #1), thru the culvert and Potomac Railroad Yards, and following the arc of a curve to the left whose radius is 446.47 feet and whose chord and chord bearing are 485.07 feet and N. 80° 02′ 34.5″ E. respectively for an arc distance of 512.80 feet to a point of tangency whose coordinates are N. 430,739.11 and E. 2,412,355.13; thence N. 47° 08′ 20″ E. 400.92 feet to a point of curvature having coordinates N. 431,011.83 and E. 2,412,649.01; thence following the arc of a curve to the right whose radius is 247.32 feet and whose chord and chord bearing are 288.28 feet and N. 82° 47′ 15.5″ E. respectively for an arc distance of 307.76 feet to a point of reversed curvature, said point having coordinates N. 431,048.02 and E. 2,412,935.01; thence following the arc of a curve to the left whose radius is 692.78 feet and whose chord and chord bearing are 339.43 feet and S. 75° 44′ 39″ E., respectively for an arc distance of 342.92 feet to a point of tangency with coordinates N. 430,964.43 and E. 2,413,263.99; thence running S. 89° 55′ 29″ E., thru the culvert at George Washington Memorial Parkway and to the Potomac River.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Arlington County, Virginia. Deed Books.

——. Common Law Order Books.

——. County Board Minute Books.

Arlington Historical Society. The Arlington Historical Magazine. Arlington; annual.

Bain, Chester W. Annexation in Virginia: The Use of the Judicial Process for Readjusting City-County Boundaries. Charlottesville, 1966.

Caton, James R. Legislative Chronicles of the City of Alexandria. Alexandria, 1933.

Conway, Martha Bell. The Compacts of Virginia. Richmond, 1963.

Hall, Clayton C., ed. Narratives of Early Maryland, 1633-1684. New York, 1910.

Hening, William Waller. The Statutes at Large; Being a Collection of All the Laws of Virginia from the First Session of the Legislature in the Year 1619. Second edition. New York, 1823.

Mayor and Citizens of Alexandria, Virginia. "Remonstrance of … Against the Bill to Annex the city and county of Alexandria, to the District of Columbia." Alexandria, 1865.

Moore, Gay Montague. Seaport in Virginia, George Washington's Alexandria. Richmond, 1949.

Richardson, James D., ed. A Compilation of the Messages and Papers of the Presidents, 1789-1897. Washington, 1896.

Robinson, M. P. Virginia Counties, Those Resulting from Virginia Legislation. Bulletin of the Virginia State Library. Richmond, 1916.

Shepherd, Samuel. The Statutes at Large of Virginia from the October Session 1792 to December Session 1806. Richmond, 1835.

Stetson, Charles W. Four Mile Run Land Grants. Washington, 1935.

United States. House of Representatives, Seventy-Fourth Congress, 2nd Session. House Document 374; "Report of the District of Columbia—Virginia Boundary Commission."

——. House of Representatives, Seventy-eighth Congress, 1st Session. Report No. 895; "Establishing a Boundary Line Between the District of Columbia and the Commonwealth of Virginia."

——. Statutes at Large.

Virginia. Code of Virginia, 1950, as Amended.

——. Acts of Assembly.

Footnotes

[1] Acts of Congress, February 27, 1801 and March 3, 1801. U.S. Stat. at Large, Vol. 2, pp. 103, 115.

[2] Acts of Assembly, 1920, Chapter 241.

[3] The smallest is Kalawao County, Hawaii, and the second smallest, Bristol County, Rhode Island.

[4] Hening, Vol. i, p. 57. Cf. also Title 7.1, Sec. 1, Code of Virginia, 1950.

[5] Hening, Vol. i, p. 80. Cf. also Title 7.1, Sec. 1, Code of Virginia, 1950.

[6] Hening, Vol. i, p. 100.