The Project Gutenberg EBook of "Persons Unknown", by Virginia Tracy This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net Title: "Persons Unknown" Author: Virginia Tracy Illustrator: Henry Raleigh Release Date: September 27, 2011 [EBook #37545] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK "PERSONS UNKNOWN" *** Produced by Roland Schlenker, Mary Meehan and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

ILLUSTRATIONS BY

HENRY RALEIGH

NEW YORK

THE CENTURY CO.

1914

Copyright, 1914, by

The Century Co.

Copyright, 1914, by The Ridgway Company

Published, October, 1914

TO

MY FELLOW-CONSPIRATORS

HELEN L. KLOEBER AND JESSIE C. SOULE

"Ask Nancy Cornish!"

The phrase might have exploded into Herrick's mind, it leaped there with such sudden violence, distinct as the command of a voice, out of the smothering blackness of the torrid August night.

He started up instantly, as if to listen, sitting upright on the bed from which he had long since tossed all covering. Then he frowned at the tricks which the heat was playing upon even such strong nerves as his. In the unacknowledged homesickness of his heart his very first doze had brought him a dream of home; then the dream had slid along the trail of desire to a cool sea beach, where he and Marion used to be taken every summer when they were children, and a fog had rolled in along this beach which, at first, he had welcomed because it was so deliciously cold. It was no longer his sister who was there beside him; it was no less unexpected a person than the Heroine of the novel he was writing and whose conduct in the very next chapter he had been trying all day to decide. It was a delightful convenience to have her there, ready to tell him the secret of her heart! He saw that she had brought the novel with her, all finished. She held it out to him, open, and he read one phrase, "When Ann and her lover were down in Cornwall." He asked her what that was doing there—since her name was not Ann and he had never imagined her in Cornwall. And then the fog rolled up between them, blotting out the book, blotting out his Heroine; that fog became a horror, he was lost in it, and yet it vaguely showed him the shadowy forms of shadowy persons—he hoped if they were his other characters they really weren't quite so shadowy as that!—one of whom threateningly cried to him through the fog, "Ask Nancy Cornish!" And here he was, now, actually conscious of a great rush of energy and intention, as if he really had some way of asking Nancy Cornish, or anything to ask her, if he had!

He remembered perfectly well, now, who she was—a little red-headed girl, a friend of his sister; a girl whom he had not seen in eight years and did not care if he never saw again. What had brought her into his dreams?

She certainly had no business there. No girl had any business anywhere inside his head for the present, except that Heroine of his, whose photograph he had had framed to reign over his desk. It was a photograph which he had found forgotten, last winter, in the room of a hotel in Paris, and it had seemed to him the personality he had been looking for. Of the original he knew no more than that. But he knew well enough she was not Nancy Cornish.

The novel was his first novel; and, after a long day of laborious failure at it, Herrick, in pure despair of his own work, had early flung himself abed. He had lain there waking and restless upon scorching linen, reluctantly listening, listening; to the passage of the trolley cars on upper Broadway; to the faint, threatening grumble of the Subway; the pitiful crying of a sick baby; the advancing, dying footfalls; to all the diabolic malevolence of shrieking or chugging automobiles. The mere act of sitting up, however, recalled him from the mussy stuffiness in which he had been tossing. Why, he was not buried somewhere in a black hole! He was occupying his landlady's best bedroom—the back parlor, indeed, of Mrs. Grubey's comfortable flat. Well, and to-morrow, after two months of loneliness, of one-sided conversations with the maddeningly mute countenance of his Heroine and of swapping jokes, baseball scores, weather prophecies, and political gossip with McGarrigle, the policeman on the beat, he was going to take lunch with Jimmy Ingham, the most eminent of publishers. Everything was all right! That peculiar sense of waiting and watching was growing on him merely with the restless brooding of the night, which smelt of thunder. In that burning, motionless air there was expectancy and a crouching sense of climax.

Yet it was not so late but that, in the handsome apartment house opposite, an occasional window was still lighted. The pale blinds of one of these, directly on a level with Herrick's humbler casement, were drawn to the bottom; and Herrick vaguely wondered that any one should care to shut out even the idea of air. Just then, behind those blinds, some one began to play a piano.

The touch was the touch of a master, and Herrick sat listening in surprise. The tide of lovely melody swept boldly out, filling the air with soaring angels. Could people be giving a party?

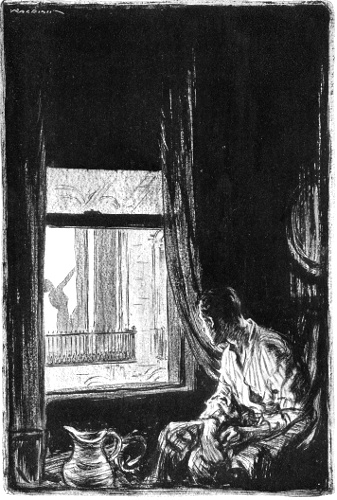

Herrick got to his feet and struck a match. Five minutes past one! If he dressed and went down to the river, he would wake Mrs. Grubey and the Grubey children. He resigned himself; glancing at the precious letter of appointment with Ingham on his desk, and at the photograph of his Heroine, looking out at him with her quiet eyes; shy and candid, tender and bravely boyish, and cool with their first youth. To her he sighed, thinking of his novel, "Well, Evadne, we must have faith!" He turned out the light again, stripped off the coat of his pajamas, sopped the drinking water from his pitcher over his head and his strong shoulders, and drew an easy chair up to the window. Down by the curb one of those quivering automobiles seemed to purr, raspingly, in its sleep. Some one across the street was talking on and on, accompanied by the musician's now soft and improvising touch. Then, in Herrick's thoughts, the voice, or voices, and the fitful, straying music began to blend; and then he had no thoughts at all.

He was wakened by a demonic crash of chords. His eyes sprang open; and there, on the blind opposite, was the shadow of a woman. She stood there with her back to the window, lithe and tense, and suddenly she flung one arm up and out in such a strange and splendid gesture, of such free and desperate passion, as Herrick had never seen before. For a full minute she stood so; and then the gesture broke, as though she might have covered her face. The music, scurrying onward from its crash, had never ceased; it had risen again, ringing triumphantly into the march from Faust, a man's voice rising furiously with it, and it flashed over Herrick that they might be rehearsing some scene in a play. Then the sound of a pistol-shot split through the night. Immediately, behind the blind, the lights went out.

The sleepy boy at the switchboard of the house opposite did not seem to feel in the situation any of the urgency which had brought Herrick into that elegant vestibule, barefoot and with nothing but an unbuttoned ulster over his pajama trousers. The boy said he guessed the shot wasn't a shot; he guessed maybe it was an automobile tire. There couldn't be a lady in 4-B, anyhow; it was just a bachelor apartment. Well, he supposed it was 4-B because there was always complaints of him playing on the piano late at night. The switchboard called him imperatively as he spoke, and he reluctantly consented to ring up the superintendent. Instinctively, he refrained from interfering with Herrick when that young man possessed himself of the elevator and shot to the fourth floor.

There was no further noises, no call for help, no woman's fleeing figure. But Herrick's sense of locality guided him down a little hall, upon which, toward the front, only two apartments opened. One of these was lettered 4-B. If Herrick had not stopped for his boots he had for his revolver and it was with the butt end of this that he began hammering upon the sheet-iron surface of that door. There was no answer. Was he too late?

The other door opened the length of a short chain. A little man, with wisps of woolly gray standing up from his head as if in amazement, brought his face to the opening and quavered, "Be careful! You'll get hurt! Be—"

"Good God!" cried Herrick. "There's a woman in there!"

"A woman! Why—I thought I heard a woman—!"

It was not so long since Herrick's reporting days but that he believed he could still work the trick pressure by which two policemen will burst in the strongest lock. But he now gave up hope of the woolly gentleman as an assistant and turned his attention to the brass knob. "Get me a screw-driver!"

"Theodore!" came a voice from behind the woolly gentleman, "Don't you open our door! It's no business of yours!"

Herrick, glancing desperately about him for any aid, was sufficiently aware that he might be making a fool of himself for nothing. But the young fellow felt that was a risk he had to take. In the long hall crossing the little one he could hear doors opening; the clash of questioning voices mingled with excited cries—And then came a girl's voice shrilling, "Isn't anybody going to do anything?" A husky business voice roared from secure cover, "You don't know what you may be breaking into, young man! You may get yourself in trouble."

Herrick growled through his teeth an imprecation that ended in "Hand me a screw-driver, can't you? And a hammer!" The sweat was pouring down his face from the pressure of his strength upon the lock, but the lock held. What was going on in there? Or—what had ceased to go on? He could hear Theodore tremblingly protesting, "I have telephoned for the superintendent—He has the keys. It's the superintendent's business—" Had the one shot done the trick? Then, above the stairhead, across the longer hall, appeared the helmet of a policeman. At his heels came the superintendent, carrying the keys.

The policeman was jolted from his first idea of arresting Herrick by Herrick's welcoming cry, "Get a gait on you, McGarrigle!" which proclaimed to him a valued acquaintance; then, with a hand shaking with excitement, the half-dressed superintendent fitted the key in the lock. The lock turned but nothing happened. The door was bolted on the inside.

The re-captured elevator was heard in the distance, and the superintendent sang out, "Get the engineer! Hurry! Make him hurry!—You heard no cries—no?" he asked of Herrick. And he stood wiping his face and breathing hard, his brow dark with trouble.

The halls had begun to be bravely peopled. Also, a second policeman had arrived. And the information spread that one of these reassuring figures had been left in the hall downstairs and that another had gone to the roof. Curiosity, comparatively comfortable and respectable, now, made itself audible and even visible on every side; some adventurers from the street had sallied in. When McGarrigle asked the superintendent, "Any way we can get a look in?" some one immediately volunteered, "There's Mrs. Willing's apartment right across the entrance-court. You can see in both these rooms from hers."

"Only two rooms?"

"Parlor, bedroom and bath," said somebody in the tone of a prospectus.

"You go see what you can see, Clancy," said McGarrigle to the second policeman. "Now, Mr. Herrick?"

Herrick told what he knew, and McGarrigle, his eyes resting with admiration on the extremely undraped muscles of his informant, plied him with attentive questions. Herrick's own eyes were on the engineer's steel. Would it never spring the bolt? "If only she'd cry out!" he said. "Why doesn't she make some sign?"

"You're sure 'twas him fired?"

"That shadow had no revolver."

"He's done for her, then. Els't he'd never have barricaded himself like, in there. He didn't give himself a dose, after?"

"Only the one shot."

"If there's an inquest you'll be wanted."

"All right.—But why hasn't he tried to gain time with some kind of parley—some kind of bluff?"

"Knows he's cornered. He'll show fight as we go in on him. If there's more than one—" The bolt gave.

McGarrigle turned like a fury. "Clear the hall," he cried.

There was a confused movement. Obedient souls disappeared.

Clancy returned and reported the front room invisible from Mrs. Willing's side window, the shade of its own side window being down. In the bedroom and bath all lights out, but shades up and nothing stirring.

"Any hall?"

The superintendent replied in the negative.

"No fire-escapes, you say?"

"No. Fireproof building."

"They're right ahead of us, then."

Again, with a long shudder, the door gave.

The whole hall seemed to give a gasping breath. McGarrigle growled. "I'll have no mix-up in this hall!" He favored Herrick with a wink that said, "See me clear 'em out!" "Clancy, you stay here by the door; pick out half a dozen of 'em that see it through and hold 'em to be witnesses." The halls were cleared. Locks clicked as if by simultaneous miracles and even the adventurers from the street could be heard in full flight. Herrick and McGarrigle exchanged grim smiles. "Now! You keep back, Mr. Herrick! Clancy, look out!" The engineer jumped to one side. The door swung open.

It gave directly into the dark room which had lately been full of light and music and a woman's passionate grace. Not a breath, not a movement, greeted the invaders. No shadow, now, on the white blind. Whatever was within the dusk simply waited. Herrick, pushing past Clancy, entered the room with McGarrigle. Behind them the superintendent leaned in and pressed an electric button. Light sprang forth, flooding everything. The room was empty.

"Get-away, eh!" said McGarrigle, grimly.

The superintendent, shaken and wide-eyed, responded only "The bolt!"

They glanced round them, non-plused.

The large living-room upon which they had entered was richly furnished, but it had no screens nor hidden corners, and, on that summer night, the windows were undraped. The doorway in which they stood faced the great window which took up nearly all the frontage of the room. The door opened against the left wall. Just beyond the door, along that left wall, stood the piano; beyond that a couch; between the head of the couch and the front window the wall was cut, up to the molding, by one of those high, narrow doors which, in a modern apartment house, indicate the welcome, though inopportune, closet. This door was the single object of suspicion; then, an overturned chair caught their attention. It lay between the great library-table which, standing horizontally, almost halved the room, and the narrow strip of paneling of wall to the right of the main door in which the superintendent had pressed the button for the lights. In the right wall, opening on the entrance-court, directly opposite the piano, but also with its blind drawn, was another window of ordinary size.

"The bedroom," said the superintendent, moistening his lips, "'s on the court, there." Then they observed, to their right, the bedroom's arch hung with heavy portières. And the sight of these portières carried with it a cold thrill. But—"There ain't anybody in there!" Clancy persisted.

McGarrigle walked over to the door in the wall and tried it. It was locked and there was no key in the lock. "What's this?"

"A closet."

"Open it, engineer. Clancy, you stand by him."

He went up to the portières, opened them with some caution and peered in. Faced only by an empty room he jerked at the portières to throw them back; they were very heavy and the humidity made their rings stick to the pole so that Deutch, running to his assistance, held one aside for him, while with his other hand he himself fumbled to spring on the bedroom light. Herrick was hard upon McGarrigle's heels, but, a look round revealing nothing, he was struck by a sudden fancy and, recrossing the living-room, raised the shade. No, the little balcony was wholly empty. The great window had been made in three sections, and the middle section was really a pair of doors that opened outward on this balcony. Clancy commented upon the foolishness of their not opening in as he watched Herrick step through them into the calm night that offered no explanation of that bolted emptiness. Herrick stepped to the end of the balcony and craned round toward the entrance-court. From the now lighted bedroom window there was no access to any other. He glimpsed McGarrigle's head stuck forth from the bathroom for the same observation. And it somehow surprised him that a trolley car should still bang indifferently past the corner; that, just opposite, that automobile should still chug away, as if nothing had happened. Then he heard a cry from the superintendent, followed by the policeman's oath. Herrick ran into the bedroom and stopped short. On the floor at the foot of the bed lay the body of a young man in dinner clothes. He had been shot through the heart.

There was something at once commonplace and incredible about it—about the stupid ghastliness of the face and about the horrid, sticky smear in the muss of the finely tucked shirt. That gross, silly sprawl of the limbs!—was it those hands that had called forth angelic music? The dead man was splendidly handsome and this somehow accentuated Herrick's revulsion. McGarrigle bent over the body. After a moment he said to the superintendent, "No use for a doctor. But if you got one, get him."

"He's dead!" said the superintendent. "It's suicide!" He spoke quietly, but with a dreadfully repressed and labored breath. "Officer, can't you see it's suicide?" He called up the doctor, and then to the silent group he again insisted, "It's him shot himself. The door was bolted on the inside. He had to shoot himself!"

McGarrigle was at the 'phone, calling up the station. Turning his head he responded, "Where's the weapon?"

They had got the closet open now; no one there. No one in the bedroom closet. No one under the big brass bed, in the folds of the portières, behind the piano, under the couch. No one anywhere. Nor any weapon, either.

Herrick and Clancy began to examine the fastening of the door. It was an ordinary little brass catch—a slip-catch, the engineer called it—which shot its bolt by being turned like a Yale lock. "If this door shut behind any one with a bang, could the catch slip of itself?" The engineer shook his head.

The hall was long since full again, though the adventurers were ready to pop back at a moment's notice; pushing through them came the doctor. Herrick did not follow him into the bedroom. The room he stood in had a personality it seemed to challenge him to penetrate.

His most pervasive impression was of cool coloring. The portières were of a tapestry which struck Herrick as probably genuine Gobelin, but with their famous blue faded to a refreshing dullness and he now remembered that in handling them he had found them lined with a soft but very heavy satin of the same shade, as if to give them all possible substance. The stretched silk, figured in tapestry, which covered the walls, had been dyed a dull blue, washed with gray, to match them; and, to Herrick, this tint, sober as it was, somehow seemed a strange one for a man's room. In couch and rugs and lampshades these notes of gray and blue continued to predominate, greatly enhanced by all the woodwork, which, evidently supplied by the tenant, was of black walnut.

He had been no anchorite, that tenant. In the corner between the bedroom and the court window the surface of a seventeenth century sideboard glimmered under bright liquids, under crystal and silver. Beyond that window all sorts of rich lusters shone from the bindings of the books that thronged shelves built into the wall until they reached the great desk standing in the farthest right hand corner to catch the front window's light. A lamp stood on this desk, unlighted. At present all the illumination in the room came from three other lamps; one that squatted atop of the grand piano, between the now flameless old silver candelabra; one, almost veiled by its heavy shade, in the middle of the library table; and one, of the standing sort, that rose up tall from a sea of newspapers at the head of the couch. All these lamps, worked by the same switch, were electric, and the ordinary electric fixtures had been dispensed with; the light was abundant, but very soft and thrown low, with outlying stretches of shadow. It was not remarkable that it had failed to show them the murdered man until the electricity in the bedroom itself had been evoked.

Herrick looked again at the couch. Its cushions had lately been rumpled and lounged upon; at its head, under the tall lamp, stood a teakwood tabouret, set with smoking materials on a Benares tray. At its foot, as if for the convenience of the musician, a little ebony table bore a decanter and a bowl of ice; the ice in a tall glass, half-empty, was still melting into the whiskey; in a shallow Wedgewood saucer a half-smoked cigarette was smoldering still.

"McGarrigle!" said Herrick, in a low voice.

"Hallo!"

"He was shot in here, after all. I was sure of it." And he pointed to the foot of the piano stool. Still well above the surface of the hardwood flooring was a little puddle of blood.

McGarrigle contemplated this with a kind of sour bewilderment. "Well, the coroner's notified. You'll be wanted, y'know, to the inquest."

"What's this?" asked somebody.

It was a long chiffon scarf and it lay on the library table under the lamp. Clancy lifted it and its whiteness creamed down from his fingers in the tender lights and folds which lately it had taken around a woman's throat. Just above the long silk fringe, a sort of cloudy arabesque was embroidered in a dim wave of lucent silk. And Herrick noticed that the color of this border was blue-gray, like the blue-gray room. As they all grimly stared at it, the superintendent exclaimed, "I never saw it before!"

McGarrigle looked from him to the scarf and commanded, in deference to the coming coroner, "You leave that lay, now, Clancy!"

Clancy left it. But something in the thing's frail softness affected Herrick more painfully than the blood of the dead man. In no nightmare, then, had he imagined that shadow of a woman! She had been here; she was gone. And, on the floor in there, was that her work?

Now that the interest of rescue had failed, he wanted to get away from that place. He wanted to dress and go down to the river and think the whole thing over alone. He had now heard the doctor's verdict of instant death; and McGarrigle, again reminding him that he would be wanted at the inquest, made no objection to his withdrawal.

On his own curb stood a line of men, staring at the windows of 4-B as if they expected the tragedy to be reënacted for their benefit. They all turned their attention greedily to Herrick as he came up, and the nearest man said, "Have they got him?"

"Him?"

"Why, the murderer!"

"Oh!" Herrick said. Even in the crude excitement of the question the man's voice was so pleasant and his enunciation so agreeably clear that Herrick, constitutionally sensitive to voices and rather weary for the sound of cultivated speech, replied familiarly, "I'm afraid, strictly speaking, that there isn't any murderer. It's supposed to be a woman."

"Indeed! Well, have they caught her?"

"They've caught no one. And, after all, there seems to be some hope that it's a suicide."

"Oh!" said the other, with a smile. "Then you found him in evening dress! I've noticed that bodies found in evening dress are always supposed to be suicides!"

The note of laughter jarred. "I see nothing remarkable," Herrick rebuked him, with considerable state, "in his having on dinner clothes."

"Nothing whatever! 'Dinner clothes'—I accept the correction. Any poor fellow having them on, a night like this, might well commit suicide!—I'm obliged to you," he nodded. And, humming, went slowly down the street.

Herrick suddenly hated him; and then he saw how sore and savage he was from the whole affair. The same automobile still waited, not far from his own door, and he longed to leap into it and send it rapid as fury through the night, leaving all this doubt and horror behind him in the cramped town. His troubled apprehension did not believe in that suicide.—What sort of a woman was she? And what deviltry or what despair had driven her to a deed like that? Where and how—in God's name, how!—had she fled? He, too, looked up at that window where he had seen the lights go out. It was brightly enough lighted, now. But this time there was no blind drawn and no shadow. The bare front of the house baulked the curiosity on fire in him. "How the devil and all did she get out?" It was more than curiosity; it was interest, a kind of personal excitement. That strange, imperial, and passionate gesture! The woman who made it had killed that man. Of one thing he was sure. "If ever I see it again, I shall know her," he said, "among ten thousand!"

Late the next morning Herrick struggled through successive layers of consciousness to the full remembrance of last night. But now, with to-morrow's changed prospective, those events which had been his own life-and-death business, had, as it were, become historic and passed out of his sphere; they were no longer of the first importance to him.

Inestimably more important was his appointment with Ingham. Herrick had passed such a lonely summer that the prospect of a civilized luncheon with an eminent publisher was a very exciting business. Moreover, this was a critical period in his fortunes.

At twenty-eight years of age Bryce Herrick knew what it was to live a singularly baffled life—a life of artificial stagnation. His first twenty-two years, indeed, had been filled with an extraordinary popularity and success. In the ancient and beloved town of Brainerd, Connecticut, where he was born, it had been enough for him to be known as the son of Professor Herrick. The family had never been rich, but for generations it had been an honored part of the life of the town. It was Bryce's mother who, marrying in her girlhood a spouse of forty already largely wedded to his History of the Ancient Chaldeans and Their Relation to the Babylonians and the Kassites, brought him a little fortune; she brought, as well, the warm rich strain of mingled Irish and Southern blood which still touched the shrewdness of her son's clear glance and his boyish simplicity of manner, with something at once peppery and romantic. It was a popular combination. He grew into a tall youth with a square chin, with square white teeth and rather an aggressive nose, but, in his crinkly blue eyes, humor and kindness; with a kind of happy glow pervading all his thought and all his dealings—just as it pervaded his fresh color, his look of gay hardihood and enduring power, the ruddiness of his brown hair and his tanned skin, and of his sensitive and sanguine blood. At college he had appeared very much more than the son of an eminent man. Of that fortunate physical type which is at once large and slender—broad shouldered and deep chested, but narrow hipped, long of limb and strong and light of flank—it had surprised nobody when he became, as if naturally, spontaneously, a figure in athletics. What surprised people was the craftmanship in those articles of travel and adventure which sprang from his vacations. At twenty-two he was a reporter on the New York Record; soon other reporters were prophesying that rockets come down like sticks, and he was not yet twenty-three when the blow fell. Mrs. Herrick died, and it was presently found that her money had been a long time gone; mismanaged utterly by a hopeful husband. This amiable and innocent creature had been bitten, in his old age, by the madness and the vanity of speculation; he had made a score of ventures, not one of which had come to port. His health being now quite shattered, Switzerland was prescribed; there, for five years, in the country housekeeping of their straitened circumstances, his son and daughter tended him. There, during the first two years of exile, Herrick had written those short stories which had won him a distinguished reputation. No predictions had been thought too high for him; but he had never got anything together in book form, and bye-and-bye he had become altogether silent. It was all too painful, too futile, too muffling! He seemed to be meant for but two uses: to struggle with the knotted strains of Herrick senior's business affairs and to assist with that History of the Ancient Chaldeans and Their Relation to the Babylonians and the Kassites, which was his father's engrossing, and now sole and senile, mania. His father suffered, so that the young man was the more enslaved; and made him suffer, so that he was the more anxious his sister should do no secretary work for the Chaldeans. But it was his mother's suffering he thought of now; the years in which she had put up with all this, uncomforted, and struggled to save something out of the wreck for Marion and for him, struggled to keep the shadow of it from their youth—and he had not known! In so much solitude and so much distasteful occupation, this idea flourished and struck deep. He saw his sister's life sacrificed, too; given up to household work and nursing, to exile and poverty, with lack of tenderness and with continual ailing pick-thanks; and there grew up in him a passionate consideration for women, a romantic faith in their essential nobility, a romantic devotion to their right to happiness. Snatched from all the populous clamor and dazzle of his boyhood and set down by this backwater, alone with a young girl and the Ancient Chaldeans, he grew into a very simple, lonely fellow; sometimes irascible but most profoundly gentle; a little old-fashioned; perhaps something of the pack-horse in his daily round; but living, mentally, in a very rosy, memory-colored vision of the great, strenuous, lost, world.

Death gave him back his life; Professor Herrick followed the Chaldeans, the Babylonians, and the Kassites; within a few months Marion was married; and Herrick, with something like Whittington's sixpence in his pocket, famished for adventure and companionship, with the appetite of a man and the experience of a boy, started for the rainbow metropolis of his five-years' dream. In this mood he had rushed into the hot stone desert of New York in summer—a New York already changed, and which seemed to have dropped him out!

But he brought, like other young desperadoes, his first novel with him; and he had approached the junior partner of the famous old house of Ingham and Son with letters from mutual friends in Brainerd. Now, at last, within twenty-four hours after his own return from abroad, Ingham—himself scarcely a decade older than Herrick, preceding him at the same university, and with a Brainerd man for a brother-in-law,—had responded with the invitation to lunch. Yes, it was exciting enough! Herrick looked at his watch. It was barely ten. And then he took time to remember when he had last looked at his watch in that room.

Certainly, it was rather grim! And yet, said the desperado, it wasn't going to be such a bad thing with which to command Ingham's interest at lunch and get him into a confidential humor that wouldn't be too superior. While he was attempting to inspire Ingham with a craving for his complete works, this thrilling topic would be just the thing to do away with self-consciousness. He mustn't lose faith in himself. And, before all things, he mustn't, as he had done last night, lose faith in his Heroine!

He looked across the room at her picture; got out of bed; walked over to her, and humbly saluted. Lose faith in her? "Evadne," he said, "through my fault, through my fault, through my most grievous—You darling!" Lose faith in her!

The photograph, which looked like an enlargement of a kodak, represented a very young girl, standing on a strip of beach with her back to the sea. Her sailor tie, her white dress, and the ends of her uncovered hair all seemed to flutter in the wind. Slim and tall as Diana she showed, in her whole light poise, like a daughter of the winds, and Herrick was sure that she was of a fresh loveliness, a fair skin and brown hair, with eyes cool as gray water. It was the eyes, after all, which had wholly captured his imagination. They were extraordinarily candid and wide-set; in a shifting world they were entirely brave. This was what touched him as dramatic in her face; she was probably in the new dignity of her first long skirts, so that all that candor and courage, all the alert quiet of those intelligent eyes were only the candor and courage of a kind of royal child. She wanted to find out about life; she longed to try everything and to face everything; but she was only a tall little girl! That was the look his Heroine must have! Thus had she come adventuring to New York with him, to seek their fortunes, and all during those dreary months of heat and dust she had borne him happy company; in the Park or in the Bowery, at Coney Island or along Fifth Avenue's deserted pomp, he had always tried to see, for the novel, how things would look to that young eagerness—no more ardent, had he but realized it, than his own!—"Evadne," said he, now, "if things look promising with Ingham this afternoon we'll take a taxi, to-night, and see the moon rise up the river." He called her Evadne when he was talking about the moon; when he required her pity because the laundress had faded his best shirt, he called her Sal.

A sound as of the Grubey children snuffling round his door recalled him to the illustrious circumstance that he was by way of being a hero of a murder story. But, if he was nursing pride in that direction, it was destined to a fall. Johnnie Grubey thrust under the door something which, as he had brought it up from the mail-box in the vestibule, Johnnie announced as mail. But it was only a large, rough scrap of paper, which astonished Herrick by turning out to be wall-paper—a ragged sample of the pale green "cartridge" variety that so largely symbolizes apartment-house refinement—and which confronted him from its smoother side with the lines, penciled in a long, pointed, graceful hand,

It was many a day since Herrick had received a comic valentine, but all the appropriate sensations returned to him then. The hand of this neighborly jest was plainly a woman's and its slap brought a blush. He was forced to grin; but he longed to evade the solemn questioning of the Grubeys through whose domain he must presently venture to his bath and it occurred to him that the most peaceful method of clearing a road was to send out the younger generation for a plentiful supply of newspapers. Besides, he wished very much to see the papers himself.

He distributed them freely and escaped back to his room still carrying three. When he had closed his door, the first paragraph which met his eyes was on the lower part of the sheet which he held folded in half. It began—"The body of Mr. Ingham was not found in the living-room, but—" He flapped it over, agog for the headlines. They read:

DEATH BAFFLES POLICE.

James R. Ingham, Noted Publisher, Found Shot in Apartment—

Herrick was still standing with the paper in his hand when the second Grubey boy brought him a visiting-card. It bore the name of Hermann E. Deutch; and scribbled beneath this in pencil was the explanatory phrase, "Superintendent, Van Dam Apartment House."

Hermann Deutch was a shortish, middle-aged Jew, belonging to the humbler classes and of a perfectly cheap and cheerful type. But at the present moment he was not cheerful. He showed his harassment in the drawn diffidence of his sympathetic, emotional face, and in every line of what, ten or fifteen years ago, must have been a handsome little person. Since that period his tight black curls, receding further and further from his naturally high forehead, had grown decidedly thin, and exactly the reverse of this had happened to his figure. But he had still a pair of femininely liquid and large black eyes, brimming with the romance which does not characterize the cheap and cheerful of other races, and Herrick remembered him last night as very impressionably, but not basely, nervous.

He now fixed his liquid eyes upon Herrick with an anxiety which took humble but minute notes. Since the young fellow was at least half-dressed in very well-cut and well-cared-for, if not specially new, garments, it was clear to Mr. Deutch's reluctant admiration that he was thoroughly "high-class!" Whatever was Mr. Deutch's apprehension, it shrank weakly back upon itself. Then he simply took his life in his hands and plunged.

"I won't keep you a minute, Mr. Herrick. But I've got a little favor I want to ask you.—You behaved simply splendid last night, Mr. Herrick.—Well, I will, thanks,"—as he dropped into a chair. "I—I won't keep you a minute—"

"I'll be glad to do anything I can," Herrick interrupted.

The news in his paper had made him feel as if he had just been disinherited and, now that the dead man was a personality so much nearer home, his brain rang with a hundred impressions of pity and wonder and excitement. But he sympathized with poor Mr. Deutch; it could be no sinecure to be the superintendent of a murder! Then, recollecting, "What made you so certain it was suicide?" he asked suddenly.

"What else could it be? There wasn't anybody but him there."

"There was a woman there," Herrick said, "when the shot was fired."

The superintendent took out his handkerchief and wiped his face. "Well, now, Mr. Herrick, that's just what I wanted to see you about. Now please, Mr. Herrick, don't get excited and mad! All I want to say is, if there was a lady there last night—but there couldn't have been—well, of course, Mr. Herrick, if you say so! Why, you couldn't have seen her so very plain, now could you?"

"What are you driving at?" Herrick asked.

"Couldn't it have been a gentleman's shadow you saw, Mr. Herrick? Mr. Ingham's shadow? Raising his pistol, maybe, with one hand—"

"While he played the piano with the other?"

"Mr. Herrick, there couldn't have been any lady there!" He bridled. "It's against the rules—that time o' night! I wouldn't ever allow such a thing. There's never been a word against the Van Dam since I been running it. Why, Mr. Herrick, if there was to be that kind of talk, especially if she was to murder the gentleman and all like that, I'd be ruined. And so'd the house. It ain't one o' these cheap flat buildings. We got leases signed by—"

"Oh, I see!" Herrick felt his temper rising. But he tried to be reasonable while he added, "I'm very sorry for you. But there was a woman there. I've reported so already to the police. Even if I had not, I couldn't go in for perjury, Mr. Deutch."

"No, no! Of course not! Of course! I wouldn't ask you! You don't understand me! It's not to take back what you said already to the police. That'd get you into trouble. And it couldn't be done. I couldn't expect it. It's not facts you might go a little easy on, Mr. Herrick; it's your language!"

"What!"

"It's your descriptive language, Mr. Herrick. If only you wouldn't be quite so particular—"

"Look here!" said Herrick with his odd, brusk slowness. "I didn't know it myself last night. But Mr. Ingham wasn't altogether a stranger to me." Deutch stared at him. "He had friends in the town I come from and a good many people I know are going to be badly cut up about his death. I was to have met him on business this very day. Now you can see that I don't feel very leniently to the person—not even to the woman—who murdered him. I don't believe he killed himself. He had no reason to do it. If there's anything I can do to prove he didn't, that thing's going to be done. If there's any word of mine that's a clue to tell who killed him, I can't speak it often enough nor loud enough. Understand that, Mr. Deutch. And, good-morning."

"Oh, my God! Oh, dear! But my dear sir—"

"And let me give you a word of warning. If you keep on like this what people will really say is, that you knew there was a woman there and that it was you who connived at her escape!"

"All right!" cried Mr. Deutch, unexpectedly. "Let 'em say it! I got no kick coming if people tell lies about me, any. All I want stopped is the lies you're putting into people's heads about Miss Christina."

"Miss Christina!" Herrick exclaimed. He stared, wondering if the poor worried little soul had gone out of his head. "I never mentioned any woman's name. I didn't know any to mention. I never heard of any Miss Christina!"

"You told the policeman the way she made motions, moving around and all like that, it made you think maybe they were rehearsing something out of a play."

"Did I? Well?"

Mr. Deutch possessed himself of the newspaper which Herrick had dropped upon the bed, and pointed to the last line of the murder story. It ran: "About a year ago Mr. Ingham became engaged to be married to Christina Hope, the actress." And Herrick read the line with a strange thrill, as of prophecy realized. "Oh—ho!" he breathed.

"Oh—ho!" hysterically mocked the superintendent. "You see what it makes you think, all right. Even me!—that was what brought her first to my mind, poor lady. The police officers may have forgot it or not noticed, any. But if you say it again, at the inquest, you'll make everybody think the same thing. And it's not so!" he almost shrieked. "It's not so. It's a damn mean lie! And you got no right to say such a thing!"

"That's true," said Herrick, intently. After his impulsive whistle he had begun to furl his sails. He had heard vaguely of Christina Hope, as a promising young actress who had made her mark somewhere in the West, and was soon to attempt the same feat on Broadway. He knew nothing to her detriment.

"Ain't it hard enough for her, poor young lady, with him gone and all, but what she should have that said about her! And it wouldn't stop there, even! She was there alone with him at night, they'd say, with their nasty slurs. She'd never stand a chance. For there ain't any denying she's on the stage, and that's enough to make everybody think she's guilty—"

"Oh, come! Why—"

"Wasn't it enough for you, yourself?"

Herrick opened his lips for an indignant negative, but he closed them without speaking.

"The minute you seen that paragraph you felt 'She's just the person to be mixed up with things that way.' And then you grabbed hold of yourself and said, 'Why, no. She may be as nice as anybody. Give her the benefit of the doubt.' But there's the doubt, all right. You're an edjucated gennelman," said Mr. Deutch, sympathetically, "but all these prejudiced, old-fashioned farmers and low-brows like they got on juries—people like them, and Miss Christina—Oh! Good Lord! Ach, don't I know 'em! Mr. Herrick, it's my solemn word, if you say that at the inquest to turn them on to Miss Christina, you—"

"I shan't say it at the inquest," Herrick said. He was astonished at the completeness of the charge in his own mind. He was convinced, now, in every nerve, that Ingham had met death at the hands of his betrothed. But the very violence of his conviction warned him not to lay such a handicap upon other minds. His chance phrase, his chance impression, must color neither the popular nor the legal outlook. "I shall take very good care, you may be sure, to say nothing of the kind. Here!" he cried, "you want a drink!"

For Mr. Deutch, at this emphatic assurance, had put his plump elbows on his plump knees and hidden his moon face, his spaniel eyes, with plump and shaky fists. He drank the whiskey Herrick brought him and slowly got himself together; without embarrassment, but with a comfort in his relaxation which made Herrick guess how tight he had been strung. As he returned the glass he said, "If you knew what a lot we thought, Mr. Herrick, me and my wife, of the young lady, I wouldn't seem anywheres near so crazy to you."

Herrick sat down on the edge of the bed in his shirtsleeves and regarded his guest. Strict delicacy required that he ask no questions. But he was human. And he had been a reporter. He said, "You used to see her with Mr. Ingham?"

"Oh, great Scott, Mr. Herrick, we knew her long before that! Long before ever he set eyes on her. When she was a tiny little thing and her papa had money, he used to get his wine from my firm. He was such a pleasant-spoken, agreeable gentleman that when I went into business for myself I sent him my card. It wasn't the wine business, Mr. Herrick, it was oil paintings. I always was what you might call artistic; I got very refined feelings, and business ain't exactly in my line. I had as high-class a little shop as ever you set your eyes on; gold frames; plush draperies, electric lights; fine, beautiful oil paintings—oh, beautiful!—by expensive, high-class artists; everything elegant. But it wasn't a success. The public don't appreciate the artistic, Mr. Herrick, they got no edjucation. I lost my last dollar, and I don't know as I ever recovered exactly. I ain't ever been what you could call anyways successful, since."

"But you saw something of Mr. Hope—"

"Well, Mr. Hope was an edjucated gentleman, Mr. Herrick, like you are yourself. He had very up-to-date ideas; and when he'd buy a picture, once in a while I'd go up to the house to see it hung. Miss Christina was about eight years old, then, and I used to see her coming in from dancing school with her maid, or else she'd be just riding out with her groom behind her, like a little queen. When my shop failed; I went to manage my sister-in-law's restaurant. I was ashamed to let Mr. Hope know that time. But one Sunday night, my wife says to me, 'Ain't that little girl as pretty as the one you been telling me about?' And there in the door, with her long hair straight down from under her big hat and her little long legs in black silk stockings straight down from one o' them pleated skirts and her long, square, coat, was Miss Christina. Behind her was her papa and her mama. And after that they came pretty regular every week or two; we served her twelfth birthday party. My wife made a cake with twelve pink rosebuds, all herself. She was always the little lady, Miss Christina, but she made her own friends, and to people she liked she spoke as pretty as a princess. We got to feel such an affection for her, Mr. Herrick, we couldn't believe there was anybody like her in this world. We never had a child of our own, me and my wife, Mr. Herrick. It does knock out your faith in things to think a thing like that can happen, but it's what's happened to her and me. We was kind of cracked about all children, and Miss Christina was certainly the most stylish child I ever set eyes on!"

"Father living?" Herrick prompted.

"No, Mr. Herrick, no. And before he died, he got into business difficulties himself, and he didn't leave enough to keep a bird alive. I helped Mrs. Hope dispose of all the bric-a-brac, my paintings and all, everything that wasn't mortgaged, and they put it in with an aunt of Mr. Hope's, a catamaran, and went to keeping a high-class boarding-house. We're all apt to fall, Mr. Herrick. I've fallen myself."

"The boarding-house didn't succeed either, then?"

"I ask you, how could it, with that battle-ax? She cheated my poor ladies, and she bullied Miss Christina, and used to take the books she was always reading and burn 'em up, and say nasty common things to her, when she got older, about the young gentlemen that were always on her heels even then, and that she'd like well enough, one day, and the next she couldn't stand the sight of. If there's one thing Miss Christina has, more than another, it's a high spirit; she has what I'd call a plenty of it. They had fierce fights. Often, when she'd come to me with a little breastpin or other to pawn for her, so her and her mama'd have a mite o' cash, she'd put her pretty head down on my wife's shoulder and cry; and my wife'd make her a cup o' tea. She'd say then she was going to run away and be an actress. And, when she was sixteen yet, she ran. Two years afterward, her and her mama turned up in my first little flat-house; a cheap one, down Eighth Avenue, in the twenties. She was on the stage, all right, and what a time she'd had! It'd been cruel, Mr. Herrick; cruel hard work and, just at the first, cruel little of it. But now she's a leading lady. And this fall she's going to open in New York, in a big part. It's the play they call 'The Victors'; I guess you've heard. Mr. Wheeler, he's the star, and Miss Christina's part's better than what his is. But now—"

There was a pause. Mr. Deutch mopped his face, and Herrick, cogitating, bit his lip.

"This engagement to Ingham—"

"She met him about two years ago, when she had her first leading part, and they went right off their heads about each other. I never expected I should see Miss Christina act so regular loony over any man. But she refused him time and again. She said she'd always been a curse to herself and she wasn't going to bring her curse on him. In the end, of course, she gave in. She said she'd marry him this winter, if he'd go away for the summer and leave her alone. You knew it was only day before yesterday he got back from Europe?"

"Yes. I know."

"My wife and me have seen a lot more of her this summer than since she was a little girl. There's been years at a time, all the while she was on the road, that we wouldn't know if she was alive or dead. And then some day I'd come home, and find her sitting in our apartment—it's a basement apartment, Mr. Herrick!—as easy as if she'd just stepped across the street. But I wouldn't like you should think it's Miss Christina's talked to us very much about her engagement. She's a pretty close-mouthed girl, in her way, and a simply elegant lady. Not but what Mrs. Hope is an elegant lady, too. But still she is—if you know what I mean—gabby! Miss Christina's always been a puzzle to her; and she's a great hand to sit and make guesses at her with my wife. Mr. Ingham left a key with Miss Christina when he went abroad so she could come and play his piano and read his books whenever it suited her, and she'd have a quiet place to study her part. Every once in a while Mrs. Hope would take a notion it wasn't quite the proper thing she should come by herself. But after she'd seen her inside, she'd drop down our way and wait. She wasn't just exactly gone on Mr. Ingham, and my wife wasn't either."

Herrick lifted his head with a flash of interest. "Mrs. Hope opposed the marriage?"

"Well, not opposed. She never opposed the young lady in anything, when you came down to it. But he wanted she should leave the stage. And he wasn't ever faithful to her, Mr. Herrick! For all he was so crazy about her and so wild-animal jealous of the very air she had to breathe, he wasn't ever faithful to her—and if ever you'd seen her, that'd make your blood boil! She'd hear things; and he'd lie. And she'd believe him, and believe him! If it wasn't for his money, she'd be well rid of him, to my mind."

He sat nursing his wrath. And Herrick, still watching him, felt sorry. For, in Herrick's mind it was now all so clear; so pitiably clear! Poor little chap!—he didn't know how scanty was the reassurance in his portrait of his Miss Christina! The indulged, imperious child, choosing "her own" friends; the unhappy, bold, bedeviled girl, already with young men at her heels, whom she encouraged one day and flouted the next; pawning her trinkets at sixteen and plunging alone into the world, the world of the stage; the ambitious, adventurous woman capable of holding such a devotion as that of the good Deutch by so capricious and high-handed a return, snaring such a man of the world as Ingham by an adroit blending of abandon and retreat, putting up with the humiliations of his flagrant inconstancies only, perhaps, to find herself, after her stipulated summer alone, on the verge of losing him through his insensate jealousy—were there no materials here for tragic quarrel? Was not this the very figure that last night he had seen fling out an arm in unexampled passion and grace? In his heart he saw Christina Hope, while her betrothed, whether as accuser or accused, taunted her from the piano, kill James Ingham. And he profoundly knew that he had almost seen this with his eyes. His pulse beat high; but it was with a sobered mind that he beheld Mr. Deutch preparing to depart.

"Well, you see how I had to ask you, Mr. Herrick, not to say that lady's shadow made you think any of an actress?"

"I do, indeed."

"There isn't any language can express how I thank you. But I know if only you was acquainted with her—" He had turned, in rising, to get his hat, and he now stopped short and exclaimed with bewildered reproach, "Oh, well, now, Mr. Herrick! Why wouldn't you tell me?"

"Tell you?" Herrick's eyes followed his. They led to the likeness of his Evadne, of his dear Heroine. "Tell you what?"

"Why, that you was acquainted with—" said Mr. Deutch, extending his hat, as if in a magnificence of introduction, "Christina Hope."

Herrick could not speak. And Deutch added, "You was acquainted with her, all along! It's a real old picture—'bout five years ago. You knew her then? You knew her—And you—saw—" His voice died away. His glance turned from Herrick's and traveled unwillingly to where, upon the blinds drawn down again, across the street, it seemed to both men the shadow must start forth. And, as he slowly withdrew his gaze, Herrick saw, looking out at him from those soft, spaniel eyes, the eyes of fear.

Deutch bowed bruskly and withdrew. Herrick was alone, as he had been these many months, with the young challenge of his Heroine; the familiar face, long learned by heart, asking its innocent questions about life, shone softly out on him, in pride. And, on that August morning, he felt his blood go cold.

There was a time coming when Herrick was to salute as prophetic what he now noted with a grim amusement; that from the moment the shadow sprang upon the blind the current of his life was changed. Peopled, busy, adventurous, it had passed, as one might say, into active circulation. He was suddenly in the center of the stage.

This was brought home to him rather sharply when Deutch had been not five minutes gone. On the exit of that gentleman Herrick's first thought had been for Miss Hope's photograph. Although an actress seems less a woman than a type, yet, since, to any stray gossip, she was recognizable as a real person, she mustn't, at this critical time, be left hanging on his wall to excite comment. He had scarcely laid the photograph on his desk to compare it with a cut in one of the newspapers when information that he was "wanted on the 'phone" made him drop the paper atop of his dethroned Heroine and hurry into the hall. And the place to which the telephone invited him was the Ingham publishing house.

The message was from old Gideon Corey, the prop and counselor of the House of Ingham, father and son. It told Herrick that Ingham senior had just arrived in New York and had not yet gone to an hotel; he had turned instinctively to his office, where he besought Herrick, whose name he had recognized, to come to him and tell him what there was to tell. It was only the piteous human longing to be brought nearer, by some detail, by some vision later than our own, to those to whom we shall never be near again. Herrick flinched from the task, but there could be no question of his obedience; and he came out from that interview humbly, softened by the gentleness of such a grief. It seemed to him that he had never seen so tender a dignity of reserve; that beautiful old gentleman who had wished to question him had also wished to spare him; wished, too,—and taken the loyalest precautions—to spare some one else.

"I don't know if you are aware, Mr. Herrick," Ingham's father had said to him, "that my son was engaged to be married?"

"I had just heard—"

"Then you will understand how especially painful it is that there should be any mention of a—another lady—Miss Hope is a sweet girl," said the old gentleman, "a sweet, good girl—" He paused, as if he were feeling for words delicate enough for what he had to say; and then a little breath that was like a cry broke from him. "My son was a wild boy, Mr. Herrick, but he loved her—he loved her! Will it be necessary to add to her grief by telling her that, at the very last, he was entertaining—? I wanted her for my daughter! May she not keep even the memory of my son?"

Herrick could have groaned aloud. "Only tell me," he said, "what can I do?"

"Mr. Ingham means to ask"—Corey interposed—"whether, at the—the inquest, it will be necessary to lay so much emphasis on that shadow you observed?"

Thus, for the second time that day, from what different mouths and under what different circumstances, came the same request! And there passed over Herrick that little shiver of the skin which takes place, the country people tell you, when some one steps over your grave.

"Could you not assume that you might have been mistaken? That it might have been a man's shadow—?"

"I was not mistaken—Why, look here!" he continued, eagerly. "Can't you see that it would be the worst kind of a mistake for me to change now? They'd think I'd heard who the woman was, and was trying to shield her! And, besides," he added to Corey, "it's your only clue." It occurred to him, as he spoke, that Ingham's family might be concerned for his reputation rather than for vengeance; this continued to seem probable even while they assured him that it was not the police, but Miss Hope alone, from whom they wished to keep the circumstance; they were thinking of what would have been the dead man's dearest wish. What she read in the papers they could perhaps deny; but what she heard at the inquest—

When, however, they reluctantly agreed with him that it was too late for any effectual reticence it was with unabated kindliness that Corey went with him into the hall. "We remain infinitely obliged to you, Mr. Herrick, and—later on—we mustn't lose track of you again—Well, good-morning! Good-morning!"

It was nearly afternoon and Herrick stepped out from the dark, old-fashioned elevator into its sunny heat, which occasional spattering showers had vainly tried to dissipate, with a very highly charged sense of moving among vivid personalities. Concerning two of these there persisted a certain lack of reassurance, and as that of Ingham brightened or darkened the shadow herself now shone as a tigress devouring, now an avenging angel. Sometimes her figure stood out clearly, by itself; sometimes it wavered and changed, and passed, whether Herrick willed it or not, into the figure of Christina Hope. Then, whether for Deutch's or Ingham's sake, or for Evadne's, there was something oppressive in the sunshine.

But the young fellow was not enough of a hypocrite to pretend, even to himself, that all this excitement, all this acquaintance with swift events, with salient people under the influence of strong emotion, all this quick, warm, and strong feeling which had been aroused in himself, were anything but very welcome. Nor were his adventures over yet. His walk brought him, with a thoughtful forehead but all in a breathing glow of interest, to City Hall Park; a spot where he had loitered that summer a score of times, wearying vaguely for a friendly face. To-day, his brisk step had scarcely carried him within its boundaries before he heard his name called and, turning, was accosted by a Record acquaintance of six years ago whose recognition displayed the utmost eagerness.

The spirit of New York City, which had hitherto considered him merely one of her returned failures, had now made up her mind to show what she could do for such a darling as the near-eye-witness of a murder. He found himself hailed into the office of the Record, whence they had been madly telephoning him this long while, and immediately commissioned, at the price of a high, temporary specialist, to report the Ingham inquest, and to write a Sunday special of the murder!

He thought of Ingham's father, and "It isn't a tasty job!" he said to his old chief. But it swept upon him what material it was; it felt, in his empty hand, like the key of success; and then, there is always in our ears at such a time the whisper that it will certainly be done by somebody. "And never, surely," Herrick wrote his sister that night, "so chastely, so justly, with either such dash or such discretion, as by our elegant selves!"

This, at least, was the view which the Ingham office took of it. Corey reported the family as glad to leave it in Herrick's hands; while a tremor at once of regret, pleasure and superstition pricked over Herrick's nerves as Corey followed up this statement with an invitation through the Record phone to meet him at the Pilgrims' Club and talk some things over during lunch!

"To shake the iron hand of Fate" was becoming so much the rule that Herrick was nearly capable of feeling gripped by it even in the somewhat remote circumstances that the Pilgrims' had been founded as a club of actors and, overrun as it was by men of all professions and particularly literary men, it had remained essentially a club of actors—while he, Bryce Herrick, hastening toward it through a smart shower, had at first conceived of his novel as a play and then, in Switzerland, been baffled by the inaccessibility of that world! His novel, of whom the heroine had been so unwittingly Christina Hope!—However, the low, wide portals of the Pilgrims' received him under their great, wrought iron lanterns without excitement and he passed, self-consciously and with a certain shyness, into the cooling twilight of a hallway still perfectly calm and over the lustrous, glinting sweeps of easy and quite indifferent stairs up to an "apartment brown and booklined" that looked out on a green park.

At one of the windows Corey stood talking to a dark, heavy, vigorous man whose face was familiar to Herrick and whom Corey introduced as Robert Wheeler. It was a name of note but Herrick bewilderedly exclaimed "Miss Hope's manager?" Two or three men turned to Wheeler and grinned and he, himself, said with a gruff chuckle, yes, he supposed it had come to that, already! Herrick's embarrassed tactlessness sought refuge in looking out of doors.

The famous square had kept its ancient privacy secure from all the city's noise and hurry. It was still, secluded; self-sufficient with an old-world grace; and the green park shone fresh after the shower, its flower beds and the window boxes of its grave, dark houses gave out a delicate, glimmering sparkle along with their moist and newly piercing sweetness. Nothing could have been more tranquil except the cool spaces, the dusky, sunny, airy, oak-hued shadows of the wide-windowed club—neither could anything have been less like Mrs. Grubey's or even Professor Herrick's idea of what an actors' club would be. The whole place seemed to rebuke its visitor, more graciously than had Hermann Deutch, for the feverish suggestion which Christina's calling had hinted round her name. The blithe young gentlemen in light clothes, fussing over with cigarette smoke and real and unreal English accents, the older men, less saddled and bridled and fit for the fray but still with something at once lazy and boyish in the quick sensibility of their faces, appeared to have no very lurid intensities up their sleeve and amid so much serene and humorous assurance Ingham senior's "sweet, good girl," Hermann Deutch's "Miss Christina" seemed better founded in kind and credible probabilities. She bloomed, indeed, hedged with all proprieties in the sound of Wheeler's voice saying, "But must Miss Hope appear at the inquest?"

"Yes," said Corey, tartly, "since her name will add to its notoriety! Have you forgotten our coroner?" Wheeler lifted his thick brows in annoyance and with the same sourness of inflection Corey added, "Is it possible any corner of the universe can for a moment forget Cuyler Ten Euyck!"

Herrick started and looked at the two men with quick eagerness. "You don't mean—"

"Precisely! The mighty in high places—Peter Winthrop Brewster Cuyler Ten Euyck! No less!"

Wheeler broke into a curse and then into his deep laugh, and said Miss Hope's manager would do well to clear out before any Sherlock Holmes with wings got to throwing his mouth around here. "I can stand his always bringing down a curtain with 'Seventy times a millionaire—the world is at my feet!' A man has to believe in something! But it's his taking himself for a tin District-Attorney-on-wheels that'll get his poor jaw broken one of these days!"

Herrick's curiosity was roused to certain reminiscences and he went on putting them together even while he followed Corey downstairs and out onto an open gallery whose tables overlooked a little garden. As soon as the waiter left them he asked Corey, "But—I've been so long away—this coroner can't be the same Ten Euyck—"

"Can you think there are two?"

Well, the world is certainly full of entertainment! A man born to one of the proudest names and greatest fortunes of his time serving as coroner—coroner! That was what certain references of McGarrigle's meant, certain newspaper flippancies. "Mr. Ten Euyck!" Herrick's extreme youth had witnessed the historic thrill that shook society when the full significance of the great creature's visiting-cards first burst upon a startled and ingenuous nation! But even then Mr. Ten Euyck must have aspired beyond social thrills and seen himself as a man of parts and public conscience. It was not so much later that Herrick remembered him as a literary dabbler, an amateur statesman, endeavoring by means of elegant Ciceronics to waken his class to its duty as leader of the people! He had then seemed merely a solemn ass who, having learned during a long residence abroad an aristocratic notion of government, took his caste and its duties much too seriously.—"But why coroner?"

Despair, apparently, over that caste's lack of seriousness! There had been talk of abolishing the coronership, Corey said, and Ten Euyck had run for it. If irresponsible idlers dared to slight even the presidency in their choice of careers let them see what could be done with the least considerable of offices! If younger sons dared lessen class-power by neglecting government, let them see to what Mr. Ten Euyck could condescend in the public service! It was an old-fashioned, an old-world ambition; the man, essentially stiff-necked, essentially egotistical, was in no sense a reformer. "He pushes his office, upon my word, to the diversion of the whole town; holding court, if you please, as if he were launching a thunderbolt, making speeches and denunciations, and taking himself for a kind of District Attorney.—I may as well say, Mr. Herrick, that it's a black bitterness to me that that pretentious puppy should have authority in—in dealing with Mr. James. There was never anything cordial between them; in fact, quite the contrary. We refused a book of his once!"

"But, great heavens,—"

"It was a book of plays, Mr. Herrick; blank verse and Roman soldiery—with orations! I don't deny Mr. James's letter was a trifle saucy; he was often not conciliating; no, not conciliating! Well, now, it's Ten Euyck's turn. If he can soil Mr. James's memory in Miss Hope's eyes, why, that will be just to his taste, believe me. Now I come to think of it, I believe Miss Hope herself is rather in his black books! It seems to me she once took part in one of the plays, and it failed. I tell you all this, Mr. Herrick, because James Ingham had the highest admiration for you, and had great pleasure in the hope of bringing out your novel."

Herrick gaped at him in an astonishment which had not so much as become articulate before—such is our mortal frailty—his slight, but hitherto persistent, repulsion from the dead man was shaken to its foundation and moldered in dust away.

"Yes, when we are ourselves again, you must bring in that manuscript. Yes, yes, he wished it! They were almost the last words I had from him. He was very pleased to get your letter, very pleased. He was talking about it to Stanley, his young brother, and to me; we were all there yesterday—think of it, Mr. Herrick, yesterday!—working out his ideas for our new Weekly. He was always an enthusiast, a keen enthusiast, and the Weekly was his latest enthusiasm. Its politics would have been very different from Mr. Ten Euyck's—"

A friendly visage at another table favored them with a sidelong contortion and a warning wink. Just behind them a shrewd voice ceased abruptly and a metallic tone responded, "Yes, but you—you're a man with a mania!"

The first voice replied, "Well, you're down on criminals and I'm down on crime."

Then Ten Euyck's was again lifted. "You're out after a criminal whom you think corrupting and to wipe him out you'll pass by fifty of the plainest personal guilt! In my view nobody but the corruptible is corrupted. Any person who commits a crime belongs in the criminal class."

"Crime may end in the criminal class," the other voice took up the challenge, "but it begins at home. You can't always pounce upon the decayed core. But if you observe a very little speck on a healthy surface, one of two things—either you can cut it away and save the apple, or your tunneling will lead you farther and farther in, it will open wider and wider and the speck will vanish, automatically, because the whole rotten fruit will fall open in your hand."

"Delightful, when it does! But in this short life I prefer the pounce!"

By this time everybody was harkening and Herrick ventured to turn his chair and look round. He beheld a sallow man, nearer forty than thirty and as tall as himself or taller, but of a straighter and stiffer height; with a long head, a long handsome nose and chin, long hands and long ears. This elongated countenance was not without contradictions. Under the sparse, squarely cut mustache Herrick was surprised to find the lips a little pouting, and the glossily black eyes were prominent and full. Fastidiously as he was dressed there persisted something funereal in the effect; forward of each ear a shadow of clipped whisker leant him the dignity of a daguerreotype. He spoke neatly, distinctly. His excellent, strong voice was dry, cold and inflexible. On the whole Herrick's easy and contemptuous amusement received a slight set-back.

"I prefer the pounce!" To be pounced upon by that bony intensity might not be amusing at all!

Then he discovered what had changed his point of view: it had shifted a trifle toward the criminal's! All very well for Ten Euyck's guest—Herrick had somehow gathered that the other man was a guest—to give up the argument, indifferently refusing to play up to his host! All very well for the free-hearted lunchers to sit, diverted, getting oratorical pointers from the monologue into which Ten Euyck had plunged! It was neither the lunchers nor the guest, but Herrick who must, to-morrow morning, appear as a witness before Ten Euyck! He would have to tell the man something which the Inghams had asked him not to tell because it might prove prejudicial to James Ingham—his admirer—which Hermann Deutch had asked him not to tell because it might prove prejudicial to Christina Hope—she whose face had been his heart's companion through hard and lonely times! The idea of the inquest had become exceedingly disagreeable to Herrick.

And the more he listened to Ten Euyck, the more disagreeable it became; the more he felt that a derisive audience had underestimated its man. Ten Euyck might take himself too seriously; he might show too small a sense of the ridiculous in loudly delivering, at luncheon, a sort of Oration-on-the-Respect-of-Law-in-Great-Cities. But this depended on whether you considered him as a man or a trap. The real quality in a trap is not a sense of the ridiculous nor a delicate repugnance to taking itself seriously. Its real quality is the ability to catch things. And, as a trap, Herrick began to feel that Ten Euyck was made for success.

The new-born criminal actually felt an impulse to warn his unknown accomplice how trivial gossip had been, how blind the public gaze. Platitudes about law, yes. But, when the orator came to dealing with the lawless, the whole man awoke. Those who broke the rules of the world's game and yet struggled not to lose it were to him mere despicable impertinents whose existence at large was an outrage to self-respecting players and for what he despised he found excellent cold thrusts and even a kind of homely and savage humor. Then, indeed, "it was not blood which ran in his veins, but iced wine." Why, he was right to think of himself as a prosecutor—he was born a prosecutor! In unconsciously assuming the robes of justice he had simply found himself. To him justice meant punishment, punishment an ideal vocation for the righteous and life a thing continually coming up before him to be weighed, found wanting and rebuked. To admonish, to blame, and then—with a spring—to crush—it is a passion which grows by what it feeds on, so that even Ten Euyck's jests had become corrections and the whole creature admirably of one piece, untorn by conflicting beliefs and inaccessible to reason, provocation, pity or consequences; because illegal actions—ideas, too, daily spreading—must be suppressed at all costs by proper persons and the patriarchal arrangement of the world rebuilt over the body of a rebel.—Of course, as his cowed analyst admitted, with P. W. B. C. Ten Euyck on top! Thank heaven the monster had one weak spot! As he jibed at a newspaper cartoon of the coroner's office he displayed fully the symptom of his disease; a raging fever of egotism. He was one to die of a laugh and Herrick doubted if he could have survived a losing game.

But when was he likely to lose? Not when, as now, he lifted the bugle of a universal summons, calling expertly on a primitive instinct. Your aristocrat may be a fool and a bore in your own workshop, but he is the hereditary leader of the chase; his mounted figure convinces you he will run down the fugitive and in the minds of men the weight of his millions add themselves, automatically, to his hand. This huntsman had branched off to the importance of motive in murder trials and his audience was not smiling, now. It had warmed itself at his cold fire and the excitement of the hunt was in the air. Ten Euyck always uttered the word "crime" with a gusto that spat it forth, indeed, but richly scrunched; and it was a day on which that word could not but start an electrical contagion. Nothing definite was said, in Corey's presence; still less was a name named—nor was any needed. But a sense of gathering issues, of closing in on some breathless revelation thickened in the heating, thrilling, restive atmosphere till a boy's voice said languidly, "Lead me to the air, Reginald! This is too rich for my blood!" and they all dropped the wet blanket of a shamefaced relief upon the coroner's inconsiderate eloquence. The quiet guest got suddenly to his feet and bore his host away.

In a tone of tremulous scorn Corey said to Herrick, "He's grown a mustache, you see, because Kane wears one!"

"Kane?"

"You've no nose for celebrities! Ten Euyck brought him here to-day to pose before him as a literary man and before us as a political lion. But our coroner's founded himself on Gerrish so long I don't know what'll become of him now we've got a District-Attorney who has no particular appetite for the scalps of women!"

Kane! So the District-Attorney was the quiet guest! To Herrick's roused apprehension Kane might just as well have been brought there to be presented with any chance mention which might indicate some circumstance connected with last night. And he understood too well the allusion to Gerrish, a District-Attorney of the past whose successful prosecutions had made a speciality of women; who had never delegated, who had always prosecuted with especial and eloquent ardor, any case in which the defendant was a woman, whether notorious or desperate. Herrick could scarcely restrain a whistle; this did indeed promise a lively inquest! Heaven help the lady of the shadow if this imitation prosecutor should nose her out! It was, perhaps, an immoral exclamation. Yet all the afternoon, as Herrick worked on his story for the Record, he could not rout his distaste for his own evidence.

Even after his late and imposing lunch he brought himself to a cheap and early dinner, rather than go back to the Grubey flat. He affected, when he found himself downtown, a little Italian table d'hôte in the neighborhood of Washington Square; much frequented by foreign laborers and so humble that a plaintive and stocky dog, a couple of peremptory cats, and two or three staggering infants with seraphic eyes and a chronic lack of handkerchiefs or garters generally lolled about the beaten earth of the back yard, where the tables were spread under a tent-like sail-cloth. It was all quaint and foreign and easy; and, so far as might be, it was cool; on occasions, the swarthy dame de comptoir was replaced by a spare, square, gray-haired woman, small and neat and Yankee, whom it greatly diverted Herrick to see at home in such surroundings; a little gray parrot, looking exactly like her, climbed and see-sawed about her desk; a vine waved along the fence; the late sun flickered on the clean coarseness of the table-cloths and jeweled them, through the bottles of thin wine, with ruby glories; there was a worthless, poverty-stricken charm about the place, and Herrick sat there, early and alone, smiling to himself with, after all, a certain sense of satisfying busyness and of having come home to life again.

He had little enough wish to return to his close room where his perplexities would be waiting for him and he lingered after dinner, practicing his one-syllable Italian on Maria Rosa, the little eldest daughter of the house, who trotted back and forth bearing tall glasses of branching bread-sticks and plates of garnished sausage to where her mother was setting a long table for some fête, and, when the guests began to come, he still waited in his corner, idly watching.