The Project Gutenberg EBook of Women's Bathing and Swimming Costume in the United States, by Claudia B. Kidwell This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: Women's Bathing and Swimming Costume in the United States Author: Claudia B. Kidwell Release Date: October 1, 2011 [EBook #37586] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK WOMEN'S BATHING AND SWIMMING *** Produced by Chris Curnow, Joseph Cooper, Harry Lamé and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

Please see Transcriber's Notes at the end of this document.

United States National Museum Bulletin 250

Contributions from

The Museum of History and Technology

Paper 64

WOMEN’S BATHING AND SWIMMING COSTUME IN THE UNITED STATES

Claudia B. Kidwell

| INTRODUCTION | 3 |

| CULTURAL ENVIRONMENT | 6 |

| BATHING COSTUME | 14 |

| SWIMMING COSTUME | 24 |

| CONCLUSIONS | 32 |

Smithsonian Institution Press

City of Washington

1968

For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office

Washington, D.C. 20402—Price 50 cents (paper cover)

Claudia B. Kidwell

The evolution of the modern swim suit from an unflattering, restrictive bathing dress into an attractive, functional costume is traced from colonial times to the present. This evolution in style reflects not only the increasing involvement of women in aquatic activities but also the changing motivations for feminine participation. The nature of the style changes in aquatic dress were influenced by the fashions of the period, while functional improvements were limited by prevailing standards of modesty. This mutation of the bathing dress to the swim suit demonstrates the changing attitudes and status of women in the United States, from the traditional image of the subordinate “weaker sex” to an equal and active member of the society.

The Author: Claudia B. Kidwell is assistant curator of American costume, department of civil history, in the Smithsonian Institution’s Museum of History and Technology.

Women’s bathing dress holds a unique place in the history of American costume. This specialized garb predates the age of sports costume which arrived during the last half of the 19th century. Although bathing dress shares this distinction with riding costume, the aquatic garb was merely utilitarian in the late 18th century while riding costume had a fashionable role. From its modest status, bathing gowns and later bathing dresses became more important until their successor, the swimming suit, achieved a permanent place among the outfits worn by 20th century women. The social significance of this accomplishment was best expressed by Foster Rhea Dulles, author of America Learns to Play, in 1940, when he wrote:

The modern bathing-suit ... symbolized the new status of women even more than the short skirts and bobbed hair of the jazz age or the athleticism of the devotees of tennis and golf. It was the final proof of their successful[4] assertion of the right to enjoy whatever recreation they chose, costumed according to the demands of the sport rather than the tabus of an outworn prudery, and to enjoy it in free and natural association with men.[1]

Since the prescribed limitations of women’s role in any given period are determined and affected by many social factors, the evolution of the bathing gown to the swimming suit may not only be dependent upon the changes in the American woman’s way of life, but also may reflect certain technological and sociological factors that are not readily identifiable. The purpose of this paper is to describe the changes in women’s bathing dress and wherever pertinent to present the factors affecting these styles.[2]

Anyone who attempts to research the topic of swimming and related subjects will be confronted with a history of varying reactions. Ralph Thomas, in 1904, described his experiences through the years that he spent compiling a book on swimming:

When asked what I was doing, I have felt the greatest reluctance to say a work on the literature of swimming. People who were writing novels or some other thing of little practical utility always looked at me with a smile of pity on my mentioning swimming. Though I am bound to say that, when I gave them some idea of the work, the pity changed somewhat but then they would say “Why don’t you give us a new edition of your Handbook of Fictitious Names?” As if the knowledge of the real name of an author was of any importance in comparison with the discussion of a subject that more or less concerns every human being.[3]

Such reactions toward research about swimming probably discouraged many serious efforts of writing about the subject. Its scant coverage and even omission in histories of recreation or sports may be explained by the fact that swimming cannot be categorized as simply physical exercise, skill, recreation, or competitive sport. In trying to determine the extent to which women swam in times past it is frustrating to observe the historians’ masculine bias in researching and reporting social history.

A study of women’s bathing dress meets with similar problems, and while a discussion of bathing dress can evoke considerable interest, its nature is usually considered more superficial than serious. Descriptions of, and even brief references to, bathing apparel for women are very scarce before the third quarter of the 19th century. Before this time only decorative costume items were considered worthy of description and bathing costume was not in this category. It is only within comparatively recent times that costume historians have conceded sufficient importance to bathing dress to include meaningful descriptions in their research.

Participation in water activities was widespread in the ancient world although the earliest origins of this activity are unknown. For example, in Greece and, later, in Rome, swimming was valued as a pleasurable exercise and superb physical training for warriors. The more sedentary citizens turned to the baths which became the gathering point for professional men, philosophers, and students. Thus bathing and swimming, combined originally to fulfill the functions of cleansing and exercise purely for physical well being, developed the secondary functions of recreation and social intercourse.

With the rise of the Christian church and its spreading anti-pagan attitudes, many of the sumptuous baths were destroyed. Christian asceticism also may have contributed to the decline of bathing for cleansing. In addition there was a secular belief that outdoor bathing helped to spread the fearful epidemics that periodically swept the continent. Although there is isolated evidence that swimming was valued as a physical skill,[4] swimming and bathing all but disappeared during the Middle Ages.

In 1531, long after the Middle Ages, Sir Thomas Elyot wrote of swimming that

There is an exercise, whyche is right profitable in extreme danger of warres, but ... it hathe not ben of longe tyme muche used, specially amoge noble men, perchaunce some reders whl lyttell esteeme it.[5]

This early English writer gave no instructions, but expounded on the value of swimming as a skill that could be useful in time of war.

It herewith becomes necessary to differentiate between bathing and swimming with their attendant[5] goals, for it was the goals of each activity which influenced the associated customs and costume designs. For this discussion we shall define bathing as the act of immersing all or part of the body in water for cleansing, therapeutic, recreational, or religious purposes, and swimming as the self-propulsion of the body through water. When we refer to swimming it is necessary to distinguish whether it was considered a useful skill, a therapeutic exercise, a recreation, or a competitive sport. Thus it is important to note that while bathing for all purposes and swimming as a physical exercise, recreation, and sport died out during the Middle Ages, the latter continued to be valued as a skill, particularly for warriors. This function of swimming survived to form the link between the ancients and the 17th century.

According to Ralph Thomas, the first book on swimming was written by Nicolas Winmann, a professor of languages at Ingolstadt in Bavaria, and printed in 1528. The first book published in England on swimming was written in Latin by Everard Digby and printed in 1587. As Thomas has stated, Digby’s book

... is entitled to a far more important place than the first of the world, because, whereas Winmann had never (up to 1866) been translated or copied or even quoted by any one, Digby has been three times translated; twice into English and once into French and through this latter became and probably still is the best known treatise on the subject.[6]

This French version was first published in 1696 with its purported author being Monsieur Melchisédesh Thévenot. In his introduction Thévenot indicates that he has made use of Digby’s book in his own treatise and that he knows of Winmann’s publication. The English translation of Thévenot’s version became the standard instruction book for English-speaking peoples. Typically, his reasons in favor of men swimming were based on its being a useful skill (i.e., to keep from being drowned in a shipwreck, to escape capture when being pursued by enemies, and to attack an enemy posted on the opposite side of a river).[7]

In the 18th and 19th centuries numerous other publications on swimming appeared—too numerous to deal with in this paper. Nevertheless, the refinement of the art of swimming was not related to the number of instruction books. Few of these books actually offered new insights in comparison with those that were outright plagiarisms or filled with misinformation. In the meantime, bathing was reintroduced and as this activity became more widespread swimming was regarded as more than a useful skill, but only for men.

There is little evidence of women bathing or swimming prior to the 17th century; these activities seem to have been exclusively for men. Nevertheless, Thomas refers to Winmann as writing, in 1538, that

at Zurich in his day (thus implying that he was an elderly man and that the custom had ceased) the young men and maidens bathed together around the statue of “Saint Nicolai.” Even in those days his pupil asks “were not the girls ashamed of being naked?” “No, as they wore bathing drawers—sometimes a marriage was brought about.” If any young man failed to bring up stones from the bottom, when he dived, he had to suffer the penalty of wearing drawers like the girls.[8]

Thomas goes on to say that the only evidence he had found of women swimming in England in early days was in a ballad entitled “The Swimming Lady” and dating from about 1670. Despite these isolated references it was not until the 19th century that women were encouraged to swim.

After its decline in the Middle Ages, bathing achieved new popularity as a medicinal treatment for both men and women. In England this revival occurred in the 17th century when certain medical men held that bathing in fresh water had healing properties. The resultant spas, which were developed at freshwater springs to effect such “cures,” expanded rapidly as the number of their devotees increased. By the mid-18th century, rival practitioners claimed even greater health-giving properties for sea water both as a drink and for bathing. An economic benefit resulted when, tiny, poverty-stricken fishing hamlets became famous through the patronage of the wealthy in search of health as well as pleasure.

When the early colonists left England in the first half of the 17th century, the beliefs and practices they had acquired in their original homes were brought to the new world. Thus, it is important to note that during this period in Europe, swimming was a skill practiced by few, primarily soldiers and sailors. It was not until the second half of the century that bathing for therapeutic purposes was becoming popular in the old world.

[6]The earliest reference to women’s bathing costume has been quoted previously in Winmann’s amazing description of mixed bathing at Zurich. He referred to women, wearing only drawers, bathing with men as a custom no longer practiced when he wrote his book in 1538.

One of the earliest illustrations of bathing costume I have located is part of a painted fan leaf, about 1675, that was reproduced in volume 9 of Maurice Leloir’s Histoire du Costume de l’Antiquité in 1914. In one corner of this painting, which depicts a variety of activities going on in the Seine and on the river banks at Paris, women are shown immersing themselves in water within a covered wooden frame. They are wearing loose, light-colored gowns and long headdresses. An English source of the late 17th century described a very similar costume.

The ladye goes into the bath with garments made of yellow canvas, which is stiff and made large with great sleeves like a parson’s gown. The water fills it up so that it’s borne off that your shape is not seen, it does not cling close as other lining.[9]

In the course of my contacts with other costume historians I have encountered the belief that women did not wear any bathing costume before the mid-19th century. Supporting this theory I have seen a reproduction of a print, about 1812, showing women bathing nude in the ocean at Margate, England, but the evidence already presented indicates clearly that costume was worn earlier. Also certain English secondary sources refer to a nondescript chemise-type of bathing dress that was worn during the first quarter of the 19th century. Because little study has been given European bathing costume, it is not possible to conjecture under what circumstances costume was or was not used. We do know, however, that when bathing became popular in the new world bathing gowns were worn by some women in the old.

As many European cultural traits were transmitted to the new world via England, so was the introduction of water activities. Nevertheless it required a number of years for such cultural refinements as bathing to take root in the new environment. The early colonists brought with them a limited knowledge of swimming, but they did not have the leisure to cultivate this skill. In New England the Puritan religious and social beliefs were as restrictive as the lack of leisure time. In this harsh climate, self-indulgence in swimming and bathing did not fulfill the requirements of being righteous and useful. Thus the growing popularity of bathing among the wealthy in Europe during the 17th and early 18th centuries had little initial impact in the new world.

Although swimming as a skill predated the introduction of bathing to the new world, I will first discuss bathing since the customs and facilities established for it reveal the development of swimming in America, first for men and then for women.

One of the earliest sources showing an appreciation of mineral waters for bathing in the new world is a 1748 reference in George Washington’s diary to the “fam’d Warm Springs.”[10] At that time only open ground surrounded the springs which were located within a dense forest.

Another entry for July 31, 1769, records his departure with Mrs. Washington for these springs (now known as Berkeley Springs, West Virginia) where they stayed more than a month. They were accompanied by her daughter, Patsy Custis, who was probably taken in hope of curing a form of epilepsy with which she was afflicted. In the latter part of the 18th century hundreds of visitors annually flocked to these springs. Although the accommodations were primitive, we early note that the avowed therapeutic aims for visiting these waters were very quickly combined with a growing social life on dry land.

Rude log huts, board and canvas tents, and even covered wagons, served as lodging rooms, while every party brought its own substantial provisions of flour, meat and bacon, depending for lighter articles of diet on the “Hill folk,” or the success of their own foragers. A large hollow scooped in the sand, surrounded by a screen of pine brush, was the only bathing-house; and this was used alternately by ladies and gentlemen. The time set apart for the ladies was announced by a blast on a long tin horn, at which signal all of the opposite sex retired to a prescribed distance, ... Here day and night passed in a round of[7] eating and drinking, bathing, fiddling, dancing, and reveling. Gaming was carried to a great excess and horse-racing was a daily amusement.[11]

The more permanent bath houses found at the increasing number of springs in the early 19th century were really only shanties built where the water bubbled up. Nevertheless, as civilization moved in upon these resorts, the current taboos and mores were soon imposed. These gave rise to customs, facilities, and inventions peculiar to the pastime. The more permanent facilities carefully separated men from women. Frequently the women’s bath was located a considerable distance from the men’s and surrounded by a high fence. Female attendants were at hand to wait upon the ladies, and private rooms were prepared for their use both before and after bathing.

In the early 19th century the fame of Berkeley Springs was eclipsed temporarily by the growing popularity of other springs, such as Saratoga in the north and White Sulphur Springs in the south. The newest facilities, however, and the completion of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad, restored Berkeley to its former prosperity in the early 1850s.

The bath houses at Berkeley Springs in the 1850s are an example of the facilities that were considered convenient, extensive, and elegant during this period. The gentlemen’s bath house contained fourteen dressing rooms and ten large bathing rooms. In addition to the plunge baths, which were twelve feet long, five feet wide, and four and a half feet deep, the men had a swimming bath that was sixty feet long, twenty feet wide, and five feet deep. The ladies’ and men’s bath houses were located on opposite sides of the grove. As if this were not reassuring enough, we are told that the building for the weaker sex was surrounded by several acres of trees. Thus protected, feminine bathers could choose either one of the nine private baths or the plunge bath, which was thirty feet long by sixteen feet wide and four and a half feet deep, as well as use a shower or artificial warm baths.[12]

The differences between the two bath houses show that women were not as active in the water as the men. Judging from the kind of facilities that were provided at Berkeley Springs, the ladies did less “plunging” than the men and no swimming.

Although accepted in England, bathing in salt water did not become popular in the new world until some time after bathing at springs was established.

In 1794 a Mr. Bailey announced that he planned to institute “bathing machines and several species of entertainment” at his resort on Long Island.[13] “A machine of peculiar construction for bathing in the open sea” was advertised a few years later by a hotel proprietor at Nahant, Massachusetts.[14] There is some question as to what the term “bathing machine” describes. Existing records show that W. Merritt of New York City received a patent dated February 1, 1814, for a “bathing machine.” Unfortunately neither a description nor a drawing can be found today. European patents from the first half of the 19th century reveal that a bathing machine could be a contraption in which an individual bathed in privacy. This is what the above quotations seem to be describing. In general usage, however, “bathing machine” could also have been a device in which an individual removed his clothing to prepare for bathing; this type will be described later.

By the early 19th century floating baths were established in every city of any importance including Boston, Salem, Hartford, New York, Philadelphia, Washington, Richmond, Charleston, and Savannah. One bath located at the foot of Jay Street in New York City was described as follows:

The building is an octagon of seventy feet in diameter, with a plank floor supported by logs so as to sink the center bath four feet below the surface of the water, but in the private baths the water may be reduced to three or even two feet so as to be perfectly safe for children. It is placed in the current so always to be supplied with ocean and pure water and rises and falls with the tide.[15]

As was true at the springs, men and women were segregated; but in the floating baths they were only separated by being in different compartments rather than in different bath houses.

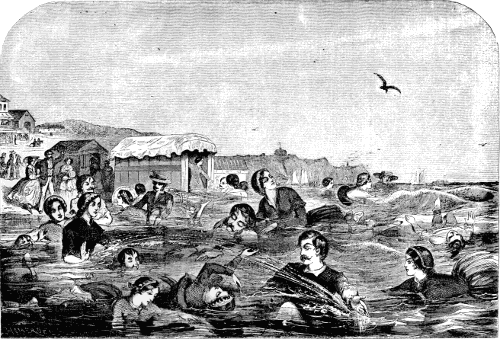

Although there were a number of these baths there were not enough to cover all of the inviting river banks and sea shores. There are many instances of men enjoying[8] the water of undeveloped shores and there is some evidence of women venturing into the bays and rivers (fig. 2).

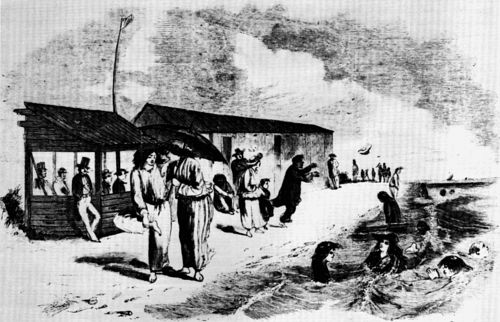

Figure 2.—“Bathing Party, 1810,” painting by William P. Chappel.

(Courtesy of Museum of the City of New York.)

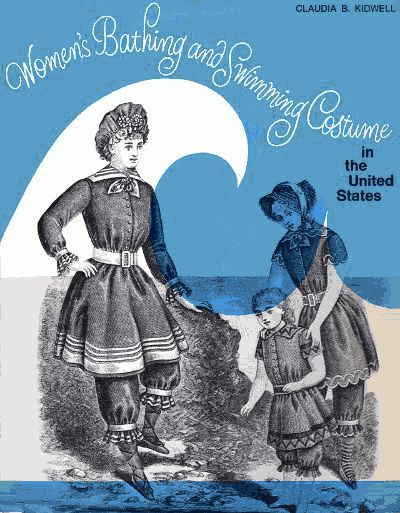

Nevertheless, few women ventured into the open ocean during the early 19th century. They were generally afraid to brave the force of the ocean waves with only a female companion, since prevailing attitudes regarding the proper behavior of a lady prevented them from being accompanied by a man. When a few ignored this dictate, their bold actions gave rise to “ill-founded stories of want of delicacy on the part of the females.”[16] An unbiased traveler, who gave an account of this mixed bathing in 1833, stated that parties always went into the water completely dressed and for that reason he could see no great violation of modesty. Mixed bathing at the seashore (fig. 3) was gaining acceptance, however, when it was reported only thirteen years later that “... ladies and gentlemen bathe in company, as is the fashion all along the Atlantic Coast....”[17]

Figure 3.—“Scene at Cape May,” Godey’s Lady’s Book, August 1849. (Courtesy of The New York Public Library.)

In place of the dressing rooms available in the floating baths, special facilities were frequently provided. The bathing machine—in this case a device in which one changed clothes—was used where there was a gentle slope down to the water. This species of bathing machine was a small wooden cabin set on very high wheels with steps leading down from a door in the front. The bather entered and, while he was changing, the machine was pulled into the sea by a horse. When water was well above the axles the horse was uncoupled and taken ashore. The bather was then free to enter the sea by descending the steps[9] pointed away from the shore (fig. 4). Machines of the 18th and early 19th century were frequently equipped with an awning which shielded the bather from public view as she or he descended the steps to enter the water. These awnings were left off the bathing machines during the last half of the 19th century. Such machines were used to a great extent in Europe during the 18th and 19th centuries. In the United States, however, they were used only to a limited extent during the first half of the 19th century. By 1870 they had practically disappeared—being replaced by the stationary, sentry-box type of individual structure and the large communal bath house.

Figure 4.—“The Bathe at Newport,” by

Winslow Homer, Harper’s Weekly Newspaper, September 1858.

(Smithsonian photo 59665.)

“Sentry-boxes” were used before the 1870s at beaches where the terrain did not encourage the use of the bathing machines. At Long Branch, New Jersey, and at one of the beaches at Newport, Rhode Island, lines of these stationary structures were available to the bather for changing, one half designated for women and the other half for men. Hours varied but it was the practice to run up colored flags to signal bathing times for the ladies and then the gentlemen. A male correspondent wrote from Newport in 1857:

If you are social and wish to bathe promiscuously, you put on a dress and go in with the ladies, if you want to cultivate the “fine and froggy art of swimming,” unencumbered by attire, you wait until the twelve o’clock red-flag is run up—when the ladies retire.[18]

From its early beginnings, in the late 18th and early 19th century, the summer excursion to the resorts and spas grew in popularity. In 1848, a writer of a Philadelphia fashion report explained that

Very few ladies of fashion are now in town, most of them being birds of passage during the last of July and all of August. Most Americans seem to have adopted the fashion of visiting watering-places through the summer.[19]

As the summer excursion became a social event, the recreational possibilities of bathing overshadowed its earlier therapeutic function. Bathing became part of an increasingly elaborate schedule of activities where each event—bathing, dining, concerts, balls, promenades, carriage rides—had its appointed time, place, and proper costume.

In addition to stiff ocean breezes, seaside resorts had an extra appeal that beguiled visitors away from the spas—namely mixed bathing. For during the bathing hour at the seashore all the stiffness and etiquette of select society was abandoned to pleasure.

Again and again I try it. Deliriusm! I forget even Miss ——, and dive headforemost into the billows. I rush to meet them. I jump on their backs. I ride on their combs, or I let them roll over me.... I am in the thickest of the bathers, and amid the roar of waves, am driven wild with excitement by the shouts of laughter; burst of noisy merriment, and little jolly female shrieks of fun. All are wild with excitement, ducking, diving, splashing, floating, rollicking.[20]

Thus bathing was transformed from a medicinal treatment to a pleasurable pursuit.

Excursionists had to be hardy individuals, firm in their resolve to complete their trip. Although[10] many railroad lines had been completed by the 1850s, transportation problems were by no means solved. For example, a New York tourist who planned to enjoy a summer at Lake George had to travel by boat from New York City to Albany and Troy, then by railroad to Morean Corner, and, finally, by stage to the lake. After listing the difficulties endured by excursionists, a particularly embittered correspondent commented in 1856, “... we envy these happy people in nothing but the power to be idle.”[21]

By the 1870s, travel facilities were rapidly being improved and many new summer resorts were established which appealed to a larger segment of the population.

Comparatively few can stay long at one time at the springs or seaside resorts, and hence the peculiar value of arrangements like those for enabling multitudes to take frequent short pleasant excursions down the New York Bay and along the Atlantic coast, as well as up the Hudson, and through Long Island Sound.[22]

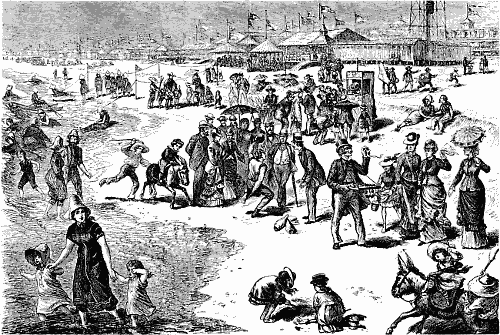

Beaches that catered to a large cross-section of the population provided a wide variety of informal activities that replaced the established functions found at the more select bathing resorts. For example, the illustration of Coney Island in 1878 (fig. 5) shows a puppet show; pony rides for children; a hurdy gurdy; vendors of walking sticks, sunglasses,[11] and food; and guide ropes in the water for timid bathers.

Figure 5.—“Scenes and Incidents on Coney Island,”

Harper’s Weekly Newspaper, August 1878.

(Smithsonian photo 59666.)

In the 1890s foreign visitors were impressed by American concern with finding opportunities to play; early in the century they had remarked on the apparent lack of interest in amusements. The term, “summer resorts,” no longer referred to a relatively small number of fashionable watering places. The New York Tribune was running eight columns of summer hotel advertisements aimed directly at the middle class. The popular Summer Tourist and Excursion Guide listed moderate-priced hotels and railroad excursions; it was a far departure from the fashionable tour of the 1840s.

Thus, as economic and technological factors changed, bathing was transformed from a medicinal treatment for the leisure class to a recreation enjoyed by a large portion of the population.

As has been stated earlier, swimming was being practiced by men in Europe when the early colonists were leaving their old homes. Nevertheless, the task of establishing new homes left them little time to practice the “art of swimming” or to teach it to fellow colonists.

Benjamin Franklin is no doubt the most famous early proponent of swimming in the colonies. In his autobiography written in the form of a letter to his son in 1771, Franklin revealed his early interest in swimming.

I had from a child been delighted with this exercise, had studied and practiced Thévenot’s motions and position, and added some of my own, aiming at the graceful and easy, as well as the useful.[23]

[12]Benjamin Franklin used every opportunity to encourage his friends to learn to swim,

as I wish all men were taught to do in their youth; they would, on many occurrences, be the safer for having that skill, and on many more the happier, as freer from painful apprehensions of danger, to say nothing of the enjoyment in so delightful and wholesome an exercise.[24]

Not only was Franklin in favor of being able to swim but when requested he advised friends on methods for how to teach oneself. His instructions, in his letter of September 28, 1776 to Mr. Oliver Neale, were published a number of times even as late as the 1830s.

America’s first swimming school was established at Boston in 1827 by Francis Liefer. Two expert swimmers, John Quincy Adams and John James Audubon, the ornithologist, visited the school and each expressed delight at having found such an establishment.

Numerous books instructing men how to swim were brought into the United States in the early 19th century and some were republished here, but the first original work (i.e., not a plagiarism) by an American was not published until 1846. In this book the author, James Arlington Bennet, M.D., LL.D., based his instructions upon his own personal observations as an experienced swimmer. Dr. Bennet’s publication requires special note not only due to the basic value of the information but because of the extraordinary title (i.e., The Art of Swimming Exemplified by Diagrams from Which Both Sexes May Learn to Swim and Float on the Water; and Rules for All Kinds of Bathing in the Preservation of Health and Cure of Disease, with the Management of Diet from Infancy to Old Age, and a Valuable Remedy Against Sea-sickness). Thanks to this explicit title we learn that Dr. Bennet was in favor of women learning to swim. This energetic aquatic activity had long been considered a masculine skill and, despite such a significant publication, this attitude continued until much later in the century.

We have already noted in a previous discussion that the Berkeley Springs bath houses of the 1850s provided a swimming bath for men but no similar facilities for women. Also at certain seaside resorts of the same period, a special time was set for men to practice the art of swimming without clothing, but women had no similar opportunity. When the ladies entered the water they were clothed from head to toe because men were also present. The description of women’s bathing costume, which will appear in a later section, clearly shows that women could do little more than try to maintain their footing. Undoubtedly some “brazen” women did find the opportunity to swim, but the general attitude was that women should only immerse themselves in water.

By the 1860s there was a widespread health movement which gave additional momentum to the belief that physical exercise was good for one’s well-being. As a result, women were being encouraged to emerge from their state of physical inactivity imposed by social custom. Swimming had already gained recognition as a healthful exercise for men, but with this fresh approach it was even being suggested that women should swim. A column that appeared in 1866, entitled “Physical Exercise for Females,” asserted that

Bathing, as it is practiced at our coast resorts, is, no doubt, a delightful recreation; but if to it swimming could be added, the delight would be increased, and the possible use and advantage much extended.[25]

In answer to the possible objection that the facilities for teaching were not always available, the writer maintained that in addition to the seashore there were rivers, lakes, and ponds as well as the swimming baths found in most large cities. He further asserted that if the demand were great enough, certain days could be appropriated exclusively to women as was done in some of the London baths.

The type of baths referred to in this case were not built simply to supply a health-giving treatment or for recreation as described earlier. As part of the health movement mentioned above, there was a growing concern in regards to personal cleansing; it was realized that merely splashing water on the face in the morning was not sufficient for good personal hygiene. While facilities for washing the whole body were being installed in wealthy homes, there was also a growing concern for the masses of people who could not afford such extravagance. Thus philanthropic individuals encouraged the building of public swimming baths in densely populated, low income areas. It was hoped that, although the patrons would be covered by bathing costume and would be seeking refreshment and recreation, this unaccustomed contact with water would improve their personal hygiene.

[13]In 1870 a reporter for Leslie’s, who was describing two elegant large bathhouses (the type described above) in New York City, stated that Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays were set apart for ladies and Tuesdays, Thursdays, and Saturdays for gentlemen. These baths became quite popular in the large cities, particularly among people who could not afford the time or money to make trips even to the near seaside resorts. By the 1880s they were so popular that bathing time was scheduled to allow many sets of bathers to enjoy the water. Thus a number of women who had probably never been completely covered with water before had the opportunity to learn to swim.

While women were being encouraged to practice swimming as a healthful exercise, this activity was being recognized as a recreation and sport for men. The increasing affluence during the last three decades of the 19th century, which made possible the widespread popularity of summer excursions, encouraged swimming as an individual pastime as well as a growing spectator sport. This was true not only for swimming but for nearly every sport we enjoy today. In 1871 a reporter wrote:

It is not underrating the interest attached to yachting or rowing matches, to say that swimming clubs and swimming matches can be made to create wider and more useful emulation among “the Million” who can never participate in or benefit by those notable trials of skill and muscle.[26]

By the 1890s this growing interest in spectator and individual sports evidenced several interesting results. Separate sporting pages were established in the formats of many newspapers. In addition to being a summer pastime, “the art of swimming” became an intercollegiate and Olympic sport, and was included on the roster of events for the 1896 revival of the Olympic Games held in Athens. Innovations in facilities and techniques helped to alter the character of swimming. The most notable of these were the development of the indoor pool and the introductions of the crawl stroke into the United States.

It was in this time period that swimming for women was becoming socially acceptable. In 1888, Goucher College, a prominent girls’ school, built its own indoor pool and the following year swimming was listed in its catalog for the first time. Writers, in turn, no longer felt it necessary to convince readers that women should be more active in the water, but concentrated instead on what a woman should know when she swims. This changing attitude gained world-wide recognition in 1912 at Stockholm when the 100-meter swimming event for women was included in the schedule.

The period of prosperity following World War I brought a marked increase in the appreciation of recreation, resulting in an increase of swimming pools and available beaches. Indoor pools, which made swimming a year-round activity, were becoming even more numerous than beaches. Swimming was now established as a sport and a recreation for both men and women. According to a 1924 magazine article in the Delineator, seldom was a swimming meet held anywhere in the country without events for women. At Palm Beach, however, one of the few remaining citadels of “high society,” an axiom of fashion dictated that a lady or gentleman not go into the water before 11:45 in the morning; should one do so, one ran the risk of being taken for a maid or valet. The masses, however, swam for pleasure without regard to the inhibitions of high fashion.

This period was also marked by the advent of swimming personalities of both sexes. Johnny Weissmuller became a popular hero for his accomplishments in competitive swimming from 1921 to 1929. Even before the war Annette Kellerman, star of vaudeville and movies, had become famous for her fancy diving as well as her celebrated figure, which she daringly exhibited in a form-fitting, one-piece suit. In addition to writing an autobiography, she authored articles and a swimming instruction book for women. As an example of what exercise, including swimming, could do for women, Annette Kellerman also lent her name to a course of physical culture for less “well-developed” ladies. Another product of this new age of recreation was Gertrude Ederle, who learned to swim at the Woman’s Swimming Association of New York. She rose to sudden fame in 1926 as the first woman to swim the English Channel.

As previously stated, swimming was practiced through the Middle Ages as a useful skill for men. Gradually this activity became regarded as also a healthful exercise and then as a recreation. Finally by the late 19th century swimming also had achieved the status of a competitive sport—but for men only. It was not until the 1920s that social attitudes permitted women the same full use of the water as men.

The restrictive attitudes defining women’s proper behavior in the water prior to the 1920s were one[14] element of the mores defining women’s participation in society. Thus as more liberal attitudes gained acceptance and modified the original concept of the “weaker sex,” women gradually achieved social acceptance of their full participation in aquatic activities.

Bathing became popular as a medicinal treatment for both men and women of the new world in the last half of the 18th century. It was the only aquatic activity, however, that was considered proper for women until over a hundred years later.

Like so many other customs, changes in bathing costume styles were initially introduced by way of England. They were adapted or rejected according to the special conditions of this continent. To give a clearer picture of the costume worn in the colonies and in the United States, descriptions of the English dress will be included where pertinent. I have not, however, found any evidence showing that bathing nude was a practice for women in this country.

It is disappointing but not surprising to discover the lack of descriptions pertaining to early bathing costume. This simple gown was utilitarian, not decorative. Thus it deserved little attention in the eyes of the contemporary bather.

No doubt it is due to the importance of the original owner that the following example has survived. In the collection of family memorabilia at Mount Vernon, there is a chemise-type bathing gown that is said to have been worn by Martha Washington (fig. 6). According to a note attached to the gown signed by Eliza Parke Custis, and addressed to “Rosebud,” a pet name for her daughter, Martha Washington probably wore this bathing gown at Berkeley Springs as she accompanied her daughter, Patsy, in her bath.

Figure 6.—Linen bathing gown said to have been worn by Martha Washington. (Courtesy of The Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association.)

This blue and white checked linen gown has several construction details similar to the chemise, a woman’s undergarment, of the period. The sleeves were gathered near the shoulder and were set in with a gusset at the armpit. The skirt of the gown was made wider at the bottom by the usual method of adding four long triangular pieces—one to each side of both the front and back. The sleeves, however, are not as full as those one would expect to find on a chemise of the period. Also a chemise would probably have had a much wider neckline gathered by a draw-string threaded through a band at the neck edge. Instead, this bathing gown has a moderately low neckline made wider by a slit down the front which is closed by two linen tapes sewn to either edge of the front. Although less fabric was used for the bathing gown than was normally required to make a chemise, it was probably not because of functional considerations as one might like to think, but because of the scarcity of fabric. Close examination reveals that the triangular sections of fabric used to add fullness to the skirt consist of several pieces. In fact the two sections used in the back are made from a different fabric, although it is still a blue and white checked linen. Frugal use of scraps in linings and hidden sections of decorative costume was common practice in the 18th century. The piecing of the bathing gown is further evidence of the fact that it was a garment that had no ornamental purpose.

Of particular interest are the lead disks which are wrapped in linen and attached near the hem next to the side seams by means of patches. No doubt these weights were used to keep the gown in place when the bather entered the water.

The following account of bathing in Dover, England, in 1782 suggests how the bathing gown might have been used at Berkeley Springs:

[15]The Ladies in a morning when they intend to bathe, put on a long flannel gown under their other clothes, walk down to the beach, undress themselves to the flannel, then they walk in as deep as they please, and lay hold of the guides’ hands, three or four together sometimes.

Then they dip over head twenty times perhaps; then they come onto the shore where there are women that attend with towels, cloaks, chairs, etc. The flannel is stripp’d off, wip’d dry, etc. Women hold cloaks round them. They dress themselves and go home.[27]

The earliest illustration showing costume worn in the United States for fresh water bathing is dated 1810 (see fig. 2). Unfortunately the painting reveals only that the bathing gowns were long and dark colored in comparison with the white dresses of the period.

An 1848 article which described, in detail, the fashionable dress called for by each activity at summer resorts, concludes with the following tantalizing paragraph:

We have no space for an extended description of suitable bathing-dresses. They may be procured at any of our town establishments for the purpose. Much depends upon individual taste in their arrangement, for uncouth as they often of necessity are, they can be improved by a little tact.[28]

This is the only reference to American bathing costume of the second quarter of the 19th century that the author has found at this time. Nevertheless, an English source describes what must have been a transitional style between the chemise-type bathing gown and the more fitted costume of the 1850s.

The Workwoman’s Guide, published in London, 1840, included instructions for making both a bathing gown and a bathing cap. Health and modesty were the main considerations that influenced the choice of color and type of material.

Bathing gowns are made of blue or white flannel, stuff, calimanco, or blue linen. As it is especially desirable that the water should have free access to the person, and yet that the dress should not cling to, or weigh down the bather, stuff or calimanco are preferred to most other materials; the dark coloured gowns are the best for several reasons, but chiefly because they do not show the figure, and make the bather less conspicuous than she would be in a white dress.[29]

The following details reveal that, in general, this 1840 bathing gown starts as an unshaped garment similar to the gown attributed to Martha Washington [brackets are mine].

As the width of the materials, of which a bathing gown is made, varies, it is impossible to say of how many breadths it should consist. The width at the bottom, when the gown is doubled, should be about 15 nails [1 nail = 21⁄4 in.]: fold it like a pinafore, slope 31⁄2 nails for the shoulders, cut or open slits of 31⁄2 nails long for the armholes, set in plain sleeves 41⁄2 nails long, 31⁄2 nails wide, and make a slit in front 5 nails long.[30]

The instructions for finishing this gown, however, show that the sleeves were worn close around the wrists and that the fullness of the skirt was secured at the waist by a belt.

In making up, delicacy is the great object to be attended to. Hem the gown at the bottom, gather it into a band at the top, and run in strings; hem the opening and the bottom of the sleeves and put in strings. A broad band should be sewed in about half a yard from the top, to button round the waist.[31]

By the addition of the above details this type of bathing gown more closely approximates the style of the long-skirted blouse of the 1850s to be described later.

In regard to the bathing cap we are told that,

These are made of oil-silk, and are worn, when bathing, by ladies who have long hair.... It is advisable, however, for those who have not long hair, to bathe in plain linen caps, so as to admit the water without the sand or grit, and thus the bather, unless prohibited on account of health, enjoys all the benefit of the shock without injuring the hair.[32]

The “Scene at Cape May” (fig. 3) shows women wearing long-skirted, long-sleeved, belted gowns as well as head coverings similar to the type described in The Workwoman’s Guide.

Thus during the period when bathing became popular as a medicinal treatment, women wore loose, open gowns perhaps patterned after a common undergarment, the chemise. Although this chemise-type bathing costume must have been very comfortable when dry, its fullness was restrictive when wet. The bather could only immerse herself in water which was all that was necessary for the treatment. As the recreational possibilities of bathing began to overshadow[16] its health-giving properties, women’s bathing dresses also became more fitted, following the general silhouette of women’s fashions.

During the first half of the 19th century in England and the United States, a more tolerant attitude toward feminine exercise led women to abandon the fiction that they were not bipedal while bathing. This acknowledgment, however, was not fostered solely by the need for a more functional bathing dress. It was first evidenced by a few daring European women who wore lace-edged pantaloons trimmed with several rows of tucking under their daytime dresses. The shorter, untrimmed, knee-length drawers which quickly replaced the pantaloons, became an unseen but essential item in the fashionable English lady’s toilette of the 1840s. These drawers, or a plainer version of the longer pantaloons, were adapted not only to the female riding habit but the bathing dress as well. An 1828 English source reported that “Many ladies when riding wear silk drawers similar to what is worn when bathing.”[33] With the increased interest in physical exercise for women, ankle-length, open pantaloons also were being worn in the 1840s with a long overdress as an early form of gymnasium suit. This evidence of the early use of drawers suggests that, like English ladies, women in the United States were probably wearing a type of drawers beneath their nondescript bathing gowns during the second quarter of the 19th century. There is some slight support of[17] this theory in the following stanza of a poem that appeared in 1845:

The rather crude but delightful sketch of seabathing at Coney Island in 1856 (fig. 7) shows the ladies wearing very full, ankle-length, trousers with a sack top extending loosely only a few inches below the waist. This type of bathing costume, which was primarily a bifurcated garment instead of a skirted one, became the prevailing fashion as reported in English women’s magazines of the 1860s.

scene at coney island—sea bathing illustrated.

Figure 7.—Sea bathing at Coney Island, from Frank

Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, September 1856.

(Smithsonian photo 58437.)

In contrast to the originally European skirtless costume, the Philadelphia publication, Peterson’s Magazine, stated that bathing dress should consist of a pair of drawers and a long-skirted dress. The recommended drawers were full and confined at the ankle by a band that was finished with a ruffle. These drawers were attached to a “body” and fastened so that, even if the skirt washed up, the individual could not possibly be exposed. The dress was made by pleating or gathering the desired length of material onto a deep yoke with a separate belt securing the fullness at the waist. The bottom of the hem was about three inches above the ankle and was considered rather short. Loose shirt sleeves were drawn around the wrist by a band which was finished with a deep ruffle as a protection against the sun. According to this article many women wore a small talma or cape which hid the figure to some extent. It was recommended that the drawers, dress, and talma be made of the same woolen material.

Bathing-dresses, although generally very unbecoming can be made to look very prettily with a little taste. If the dress is of a plain color, such as grey, blue or brown, a trimming around the talma, collar, yoke, ruffles etc ..., of crimson, green or scarlet, is a great addition.[35]

To complete a bathing toilette the following items were considered necessary: a pair of large lisle thread gloves, an oil cap to protect the hair from the water, a straw hat to shield the face from the sun, and gum overshoes for tender feet.

Figure 8.—Bathing dress, c. 1855. (Courtesy of Philadelphia Museum of Art. Photograph by A. J. Wyatt, staff photographer.)

The red, tan, and blue-green checked bathing dress shown in figure 8 is jauntily trimmed with crimson braid edging the collar, belt, and wrist and ankle bands. This costume is a variation of the style described previously. The drawers, unlike those described[18] in Peterson’s Magazine, are sewn to a linen band with linen suspenders attached. The unfitted, unshaped skirt (8 ft. 8 in. in circumference) is pulled in at the waist by a belt attached to the center back. A similar technique for forming a waistline is described in The Workwoman’s Guide of 1840.

Women’s magazines in the United States from the third quarter of the 19th century show illustrations of bathing costume, but in many instances these publications used European fashion plates. Harper’s Bazar, (spelled thus until 1929) particularly in its early years, used fashion plates and pattern supplements from its German predecessor Der Bazar. Thus, in one issue one can find a fashion plate showing the predominantly bifurcated European bathing suit and, in a column on New York fashions, a separate description of long-skirted bathing dresses with trousers. During the same period Peterson’s Magazine had illustrations previously used in the London publication, Queen’s Magazine.

American women seem to have accepted the majority of styles shown in European fashion plates, except for the skirtless bathing suits. The writer of an 1868 column on New York fashions sought to convince his readers to try the more daring European style although he grudgingly admitted that the “Bathing suits made with trousers and blouse waist without skirt are objected to by many ladies as masculine and fast....”[36] This style was in fact, very similar to the costume worn by men when they bathed with the ladies. A year later, the writer of the same fashion column had given up the campaign to dress all women in the skirtless suits and admitted that these imports “... are worn by expert swimmers, who do not wish to be encumbered with bulky clothing.”[37] Such practical bathing dress was thus limited to a very small number of progressive women.

The majority, consisting of those who were strictly bathers, wore the ankle-length drawers beneath a long dress as described or illustrated in the majority of sources that originated in the United States. Why was the European bathing suit not fully adopted by American women? Differences between the bathing customs of the two continents undoubtedly encouraged the development of different dress. While men and women in the United States bathed together freely at the seashore during the latter half of the 19th century, this practice was not widely accepted in England until the early 1900s. In the presence of men, American women probably felt compelled to retain their more concealing dress and drawers.

In England swimming seems to have been more popular among women than it was in the United States. While encouraging its readers to swim, during the late 1860s, Queen’s Magazine used forceful language of a kind that was not found in American publications until the late 19th century. If swimming was more acceptable as a feminine exercise in England it is understandable why English women were more receptive to a functional, skirtless bathing suit—especially since it was worn only in the presence of other women.

In 1858, Winslow Homer, who was later to become a well-known American painter, was welcomed into the society at Newport until it became apparent that he wanted to sketch the bathers for a weekly newspaper (see fig. 4). So great were the ensuing objections that he was permitted to complete his sketches “... provided he depicted the bathers only in the water and only above the waistline and without divulging the identity of the bathers.”[38]

As can be seen in figure 4, these sketches serve more as a testament of Homer’s fancy than as an accurate historical statement on style. The two feminine legs exposed in the water from just below the knee to the toe and the feminine head coverings appear to be anachronisms. According to several other illustrations of the period, these women were undoubtedly wearing long drawers. The young artist at 22, however, has been described as having an eye for feminine beauty and a sense of fashion. He seems to have exploited to the full the decorative possibilities of hoop skirts blown by the breeze or agitated by some pretty accident to discreetly reveal a trim ankle. A drama of breeze versus long skirt appears with the small feminine figure in the left background of this print. The force of the waves and the motion of the frolicking bathers gave the artist opportunity to show two more pretty accidents. The only head covering he showed for feminine bathers was a ruffled cap that framed the face. Other sources show Newport bathers wearing the less attractive wide-brimmed straw hat (fig. 9). The straw headgear worn over these caps seems more likely since Newport’s fashionable belles[19] would surely have sacrificed appearances and worn a straw hat to avoid an unfashionable sunburn and tan.

Nevertheless, Homer’s sketch reflects characteristics seen in certain surviving examples from the 1860s—namely that the top was becoming more fitted, being attached completely to a belt with the fuller skirt pleated or gathered to the bottom edge of the belt. In the Design Laboratory Collection of the Brooklyn Museum there is an 1860 black poplin specimen that may be a bathing dress. This example is trimmed at the shoulder seam with epaulets, an example of the extent to which fashion was finally playing a part in bathing costume.[39]

The dresses described above appear peculiar not only to 20th century eyes, but they also seem to have amused mid-19th century correspondents. One writer in 1857 declared that,

We don’t think a man could identify his own wife when she comes out of the bathing-house. A plump figure enters, surrounded with a multitude of rustly flounces and scarcely able to squeeze an enormous hoop through the door. She is absent a few minutes, and presto change! out comes a tall lank apparition, wrapped in the scanty folds of something that looks more like a superannuated night-gown than anything else, and a battered straw-chapeau knocked down over the eyes, and stalks down towards the beach with the air and gait of a Tartar chieftain![40] [fig. 10.]

Another writer felt that he

... must say—even in the columns of Frank Leslie’s Illustrated—that they don’t look very picturesque or pretty when a la Naiade.... Rather limp, sacks tied in the middle, eel-bottles, hydropathic coalheavers and “longshoremen,” and preternaturally dilapidated Bloomers, would appear to be the ideals aimed at.[41] [fig. 11.]

This use of the term “Bloomers,” referring to long full drawers or trousers, is a reminder of how similar the 1855 bathing gown with drawers (see fig. 8) was to the reform dress introduced in 1848 and worn by Amelia Bloomer, the feminist, in 1852.

Despite the evident use of a new waistline treatment, the most popular bathing costume of the 1870s, according to Harper’s Bazar, continued to feature the yoke blouse that reached at least to the knee. This combination of blouse and skirt was held in position at the waist by a belt. The high neck was finished with a sailor collar or a standing pleated frill, while the long sleeves and full Turkish trousers, buttoned on the side of the ankle, concealed the limbs. In 1873 a column on New York fashions reported an effort to popularize short-sleeved, low-throated suits then in favor at European bathing places and which had been illustrated in the Bazar. Nevertheless, the writer hedged this report by adding that

It is thought best, however, to provide an extra pair of long sleeves that may be buttoned on or basted in the short puffs that are sewn in the arm holes. Sometimes a small cape fastening closely about the throat is also added.[42]

Nevertheless, sketches of bathing scenes from the seventies indicate that some American women wore even shorter sleeves and trousers than those prescribed by the fashion magazines.

Linen and wool fabrics were both suggested in the 1840s, but by the 1870s flannel was most frequently used for bathing dresses, with serge also being recommended. Navy blue, and to a lesser extent, white, gray, scarlet, and brown were popular colors in[20] checks as well as solid colors trimmed with white, red, gray, or blue worsted braid.

Bathing mantles or cloaks were worn to conceal the moist figure when crossing the beach. These garments were made of Turkish toweling with wide sleeves and hoods, and were so long as “to barely escape” the ground.

In 1873 one good bathing cap was described as an oiled silk bag-crown cap large enough to hold the hair loosely. The frill around the edge was bound with colored braid. Many ladies preferred, however, to let their hair hang loose and under a wide-brimmed hat of coarse straw tied down on the sides to protect their skin from the sun (fig. 9).

Bathing shoes or slippers were generally worn when the shore was rough and uneven. In 1871 manila sandals were worn, but the most functional bathing shoes are said to have been high buskins of thick unbleached cotton duck with cork soles. They were secured with checked worsted braid. Two years later there were bathing shoes of white duck or sail canvas with manila soles. Slippers for walking in the sand were “mules” or merely toes and soles made of flannel, braided to match the cloak, and sewn to cork soles.

Throughout this period the social aspect of bathing predominated over the therapeutic goals and women were making a greater effort to transform their bathing garments into attractive and functional outfits. Motivated by the presence of men at the seashore and by the competition with other women for masculine attention, ladies were more concerned with the style of their bathing dresses and appropriate trimmings. Thus bathing costume joined the ranks of other fashions described in women’s magazines.

Now that women were frolicking in the water rather than simply being dunked several times, their costume became somewhat more functional. Long trousers gave them greater freedom in the water although the skirts which continued to be worn,[21] tended to negate this improvement. Even as early as the 1870s there were efforts to shorten sleeves and eliminate high necklines. This trend to make bathing dress more practical increased in momentum toward the end of the century.

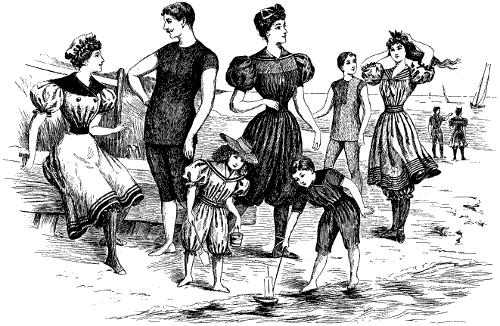

Although attitudes toward sports were more enlightened by the 1880s, many women continued to wear the old bathing dress with its belted blouse extending to a long skirt and a pair of trousers. As an alternate to this garb, the “princess style” was developed with the blouse and trousers cut in one piece or else sewn permanently to the same belt. A separate skirt extending below the knee was buttoned at the waist to conceal the figure. This new style in bathing costume was probably derived from an innovation in women’s underwear. During the late 1870s a new style of undergarment, the “combination” of chemise and drawers, had come into use. Petticoats could be fastened to buttons sewn around the waist of the combination. This streamlining of undergarments helped the lady of fashion to maintain a desirably svelte figure. Apparently the advantages of this streamlining were obvious, because it was not long before women were quietly adapting this style to bathing dresses. By the 1890s the skirt was often omitted for swimming (fig. 12), giving the more active women more freedom in the water. Following popular dress styles, the top of the bathing costume was bloused over the belt. The sailor collar, either large or small, was a great favorite, but a straight standing collar with rows of white braid was also worn.

Figure 12.—Bathing costumes from a supplement to The

Tailor’s Review, July 1895.

(Courtesy of Library of Congress.)

The “princess style” was not the only innovation available in bathing dress. Harper’s Bazar reported in 1881 that imported French bathing suits[43] for ladies[22] were made without sleeves, since any covering on the arm interfered with the freedom desirable for swimming. Nevertheless, according to other contemporary fashion descriptions, American bathing suits retained their long sleeves until the early 1880s when the foreign fashion of short sleeves came to the United States. In 1885 it was reported that

The sleeves may be the merest ‘caps’ four or five inches deep under the arm, curved narrow toward the top, and lapped there or they may be half-long and straight, reaching to the elbows, or else they may be the regular coat sleeves covering the arms to the wrist. With the short sleeves it is customary to add the sleeves cut from a gauze vest to give the arm some protection from the sun.[44]

Sleeves were pushed up in 1890 and puffed high about the shoulders by means of elastic tape in the hem. By 1893 fashion reports acknowledged that sleeve length was a matter of individual choice.

Despite this neat resolution of the diminishing sleeve, contemporary sketches of bathing scenes indicate that some women in the United States were wearing the shorter sleeves even earlier.

Short full trousers, reaching just below the knee, accompanied by knee-length skirts—sometimes worn even shorter—succeeded the long Turkish trousers and ankle-length skirt. As the trousers diminished in length, long stockings or bathing shoes with long stocking tops became a necessary part of the bathing costume to cover the lower limbs, particularly in mixed bathing (see fig. 1). The stockings, which were cotton or wool, plain or fancy, and of any color or combination of colors in keeping with the costume, were worn with a variety of bathing shoes, sandals, or slippers when bathing off a rocky shore. Foot coverings were usually made of white canvas; the slippers were held on by a spiral arrangement of braid or ribbon about the ankles, while the laced shoes were often made with heavy cork soles. A gaiter shoe or combination shoe and stocking was made of waterproof cloth, laced up the sides, and reached to about the knees. Low rubber shoes were also worn.

Bathing caps of waxed linen or oiled silk were used to protect the hair. They had whale bone in the brim and could be adjusted by drawstrings in the back. Blue, white, or ecru rubber hats were also used. These caps had large full crowns—which held in all the hair—and wired brims. A wide-brimmed rough straw hat, tied on with a strip of trimming braid or with ribbon, was sometimes worn as protection against the sun (fig. 9).

Bathing mantles like those of the 1870s were still being worn by the late 19th century and these were frequently trimmed with colored braid. Cotton tapes sewn in parallel rows, mohair braid, or strips of flannel were still being used to make the bathing dress more attractive.

Navy blue and white, as well as ecru, maroon, gray, and olive were popular colors for the bathing dress. In 1890 the writer of a fashion column thought it pertinent to add that “... black bathing suits are worn as a matter of choice, not merely by those dressing in mourning.”[45] Apparently the wearing of black no longer had this exclusive significance when bathing, but prior to 1890 it did.

As women became more active in the water and were learning to swim they began to accept more practical changes in bathing costume. Not only the style, as described previously, but also the fabric was considered for its functional characteristics. Flannel was still widely used but was being replaced by serge which was not as heavy when wet. Another indication of this trend was that stockinet, a knitted material, was gaining in popularity at the end of the century.

The “princess style” of the early 1890s combined the drawers and bodice in one garment: the separate skirt fell just short of the ends of the drawers which covered the knees. By the mid-1890s, however, the drawers which were now called knickerbockers, were shortened so as to be completely covered by the knee-length skirt. These knickerbockers were either attached to the waist in the popular “princess style” or they were fastened to the waist by a series of flat bone buttons.

During this same period, the mid-1890s, knitted, cotton tights were sometimes worn in place of knickerbockers. Bathing tights differed from the knickerbockers in that they were hemmed rather than gathered on an elastic band at the lower edge and that they were not attached to the waist. When tights were used they were completely concealed by a one-piece, knee-length bathing dress. The use of the more streamlined bathing tights was another step toward more functional bathing costume. Despite these improvements, most women continued to wear stockings, usually black, when they[23] bathed or swam in public. The dictates of fashion and standards of modesty continued to conflict with practical considerations.

As with street dress, corsets seem to have been an important though unseen bathing article necessary for maintaining smart posture. In 1896 it was reported that

Unless a woman is very slender, bathing corsets should be worn. If they are not laced tightly they are a help instead of a hindrance to swimming, and some support is needed for a figure that is accustomed to wearing stays.[46]

While describing the bathing dresses available in 1910 an article noted: “Some of these are made up with ... princess forms that are boned so as to do away with the bathing corset.”[47]

The bodice of the bathing costume continued to be bloused, but by 1905 it was modified to be merely loose. An article appearing in 1896 noted that bathing suits should be cut high in the neck, not tight around the throat, but close enough to prevent burning by the sun. The sailor collar continued to be used during the late 1890s but became less fashionable shortly after the turn of the century. Nevertheless there had to be some white around the neck for the bathing dress to be considered smart. The puffed sleeves, which had become popular in the late 1890s were modified in breadth and length to allow free use of the muscles in swimming (fig. 13).

In 1897 fashion magazines were suggesting that skirts of bathing dresses looked best when the front breadth was shaped narrower toward the belt, while by 1902 the skirts were fitted over the hips in order to delineate the figure. In 1905 pleated skirts again became fashionable, although flared skirts were still acceptable.

Dark blue and black were the popular colors, although white, red, gray, and green were also used. Flannel was no longer recommended for bathing dress; serge and “mohair”—a fabric with a cotton warp and a mohair or alpaca weft—were widely used. The impractical bathing dress of silk fabric was worn by those who could afford this extravagance; thus, the conspicuous consumption of the “leisure class” was even found at the beaches.

Bathing hats were still being worn but it was considered more fashionable to wear a rubber or oil silk cap covered with a bright silk turban when there was a surf. For the bather who seldom ventured very far into the water the most fashionable practice was to have no covering at all.

Throughout the 19th century bathing costume followed an impelling course toward becoming more functional. As the popularity of recreational bathing and then swimming for women increased, the number of yards of fabric required to make a bathing dress decreased. Nevertheless, by the 1900s, many women knew how to swim, but the majority were still bathers. Thus bathing suits continued in use through the first quarter of the 20th century.

Bathing costume did not evolve gracefully into the swim suit, nor was there an abrupt replacement of one garment for the other. Instead, a garb designed for swimming emerged in the 19th century as tentatively and as poorly received as had the suggestion that women should be active in the water. The growing popularity of swimming and the changing status of women eventually made it possible for the swimming suit to replace the bathing suit in the 1920s. By the 1930s, however, this trend was accelerated by a growing advertising and ready-to-wear clothing industry. Thus a history of the swimming costume tends to divide itself into two sections: early swimming suits and the influence of the swim suit industry.

The earliest reference to swimming costume I have found was in 1869. At this date swimming in the United States was considered a masculine skill, exercise, and recreation; only men were provided with a real opportunity to swim at popular watering places. As described previously, Harper’s Bazar reported that American women in general rejected the European bathing suit made with long trousers and a skirtless waist. Nevertheless, this costume was “... worn by expert swimmers, who do not wish to be encumbered with bulky clothing.”[48]

In the 1870s the rare descriptions of this more functional garment—called “swimming suit” even at this early date—were limited to a sentence or two buried within long columns of fine print describing popular bathing apparel. One mentions a “... single knitted worsted garment, fitting the figure, with waist and trousers in one.”[49] Another was made without sleeves as “one garment, the blouse and trousers being cut all in one, like the sleeping garments worn by small children.”[50] These more practical bifurcated garments probably derived from the European suit of the 1860s that had been rejected by the majority of American women. For example, an English source reported that in 1866 the following garment was worn: “... Swimming Costume, a body and trousers cut in one, secures perfect liberty of action and does not expose the figure.”[51]

The descriptions of American swimming suits, however brief, offered evidence that the pastime was growing in popularity with women. Generally speaking, 19th century women’s magazines were mere disseminators of fine and decorous ideas and practices for well-mannered ladies; their editors were not innovators. With such an editorial policy it is understandable that these magazines would not, as a rule, publicize trends of popular origin until they were fairly well established. The skirtless swimming suit of the 1870s was no doubt more common in the United States than its meager description in Harper’s Bazar would seem to indicate.

As long as feminine swimming was not generally accepted, however, efforts to develop practical swimming suits remained isolated owing to the lack of communication between manufacturer and consumer and to traditional attitudes. Feminine interest in swimming and physical activities threatened belief in the “weaker-sex” that contributed to maintaining the traditional masculine and feminine roles; efforts to develop functional swimming dress also attacked established standards of feminine modesty. These challenges to the status quo were met with the weapon of the complacent majority—silence. Consequently, from the third quarter of the 19th century, when we find the first reference to a specialized garment for swimming in the United States, writings on swimming costume appeared infrequently until the 1920s.

In 1886 two “ladies’ bathing jerseys” and two bathing suits of the traditional type appeared in the First Illustrated Catalogue of Knitted Bathing Suits of J. J. Pfister Company in San Francisco. The captions over the illustrations leave no question that the briefer bathing jerseys were intended for swimming while the others were for bathing. These jerseys—form-fitting tunics that were mid-thigh in length—were made with high necks and cap sleeves. Underneath this garment women wore trunks that extended to the knee and stockings; there was also the alternate choice of tights, a combination of trunks and stockings. To complete the outfit the feminine reader was encouraged to buy a knitted skull cap.

Apparently these bathing jerseys were successful; three, instead of two, jerseys appeared in the same[25] catalog in 1890. It is obvious from this later catalog, however, that there was a greater demand for bathing dresses since twelve designs of the skirted costume were featured as opposed to the two dresses in the first issue.

Even by the early 20th century it is difficult to find specific references to a swimming suit in women’s magazines; only occasionally does a concern with swimming obtrude into the traditional descriptions of bathing dress. In The Woman’s Book of Sports, however, J. Parmly Paret was specific about the requirements for a suitable swimming costume in 1901.

It is particularly important that nothing tight should be worn while swimming, no matter how fashionable a dress may be for bathing. The exercise requires the greatest freedom, and a swimming costume should never include corsets, tight sleeves, or a skirt below the knees. The freedom of the shoulders is the most important of all, but anything tight around the body interferes with the breathing and the muscles of the back, while a long skirt—even one a few inches below the knees—binds the legs constantly in making their strokes.[52]

Although this costume (fig. 14) more closely resembles the traditional bathing dress than the jersey described previously, this discussion illustrates the growing dichotomy between bathing dress and swimming dress and between fashionable styles and functional styles.

Figure 14.—The recommended costume for swimming from J. Parmly Paret, The Woman’s Book of Sports, 1901. (Smithsonian photo 58436.)

Photographs of East coast beach scenes in 1903 show a few women wearing costumes different from the black or navy blue bathing dress worn by the majority. These independent spirits seem to be wearing close-fitting knitted trunks that cover the knees or, when with stockings, come within an inch or two above the knee. Above these trunks they appear to be wearing knitted one-piece tunics or belted blouses that cover the hips. This costume, sleeveless or short-sleeved, and with a simplified neckline, must have been the functional suit of its day.

An important impetus was given to the development of the swimming suit with the entrance of women into swimming as a competitive sport. On September 5, 1909, Adeline Trapp wore a one-piece knitted swimming suit when she became the first woman to swim across the East River in New York, through the treacherous waters of Hell Gate. Both the swimming suit and the swim were part of a campaign devised by Wilbert Longfellow—of the U.S. Volunteer Life Saving Corps—to encourage women to learn to swim.

Adeline Trapp was a summer employee of the Life Saving Corps in 1909. Mr. Longfellow saw in the 20-year-old Brooklyn school teacher a respectable young woman who could be a source of publicity. He ordered her to get a one-piece swimming suit for the swim. As early as 1899 in England, a woman[26] participating in competitions organized by the Amateur Swimming Association could have worn a one-piece, skirtless, knitted costume with a shaped sleeve at least three inches long, a slightly scooped neck, and legs that extended to within three inches of the knee. Mr. Longfellow may have had this English suit in mind. He might have known of similar suits in the United States or he might have simply wanted to free Adeline of yards of fabric to make her more competitive with male swimmers. Nevertheless, Adeline Trapp did not know that the English suits existed, nor did she know where she could find one. She spent many hours going from one American manufacturer to another trying on men’s knitted suits. She found that they were all cut too low at the neck and armholes and did not cover enough of the legs to preclude criticism. At this point a friend who worked for a stocking manufacturer offered to get her a suitable costume from England. This costume, a knitted, gray cotton suit—whether originally for a man or woman in England is not known—was the one Adeline wore when she swam Hell Gate.