Larger Image

The Project Gutenberg EBook of The American Indian as Slaveholder and

Seccessionist, by Annie Heloise Abel

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net

Title: The American Indian as Slaveholder and Seccessionist

An Omitted Chapter in the Diplomatic History of the Southern Confederacy

Author: Annie Heloise Abel

Release Date: November 30, 2011 [EBook #38173]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK AMERICAN INDIAN AS SLAVEHOLDER ***

Produced by Bryan Ness and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive.)

The Slaveholding Indians

| (1) As Slaveholder and Secessionist |

| (2) As Participants in the Civil War |

| (3) Under Reconstruction |

Vol. I

Indian Territory, 1861

[From General Land Office]

The American Indian as

Slaveholder and Secessionist

AN OMITTED CHAPTER IN

THE DIPLOMATIC HISTORY OF THE

SOUTHERN CONFEDERACY

BY

ANNIE HELOISE ABEL, Ph.D.

THE ARTHUR H. CLARK COMPANY

CLEVELAND: 1915

COPYRIGHT, 1915, BY

ANNIE HELOISE ABEL

TO MY FATHER AND MOTHER

| Preface | 13 | |

| I | General Situation in the Indian Country, 1830-1860 | 17 |

| II | Indian Territory in its Relations with Texas and Arkansas | 63 |

| III | The Confederacy in Negotiation with the Indian Tribes | 127 |

| IV | The Indian Nations in Alliance With the Confederacy | 207 |

| Appendix A—Fort Smith Papers | 285 | |

| Appendix B—The Leeper or Wichita Agency Papers | 329 | |

| Selected Bibliography | 359 | |

| Index | 369 |

| Indian Territory, 1861 | Frontispiece |

| Map showing free Negro Settlements in the Creek Country | 25 |

| Portrait of Colonel Downing, Cherokee | 65 |

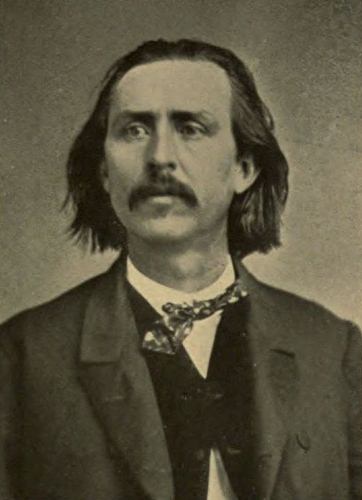

| Portrait of John Ross, Principal Chief of the Cherokees | 112 |

| Portrait of Colonel Adair, Cherokee | 221 |

| Map showing the Retreat of the loyal Indians | 263 |

| Fort McCulloch | 281 |

This volume is the first of a series of three dealing with the slaveholding Indians as secessionists, as participants in the Civil War, and as victims under reconstruction. The series deals with a phase of American Civil War history which has heretofore been almost entirely neglected or, where dealt with, either misunderstood or misinterpreted. Perhaps the third and last volume will to many people be the most interesting because it will show, in great detail, the enormous price that the unfortunate Indian had to pay for having allowed himself to become a secessionist and a soldier. Yet the suggestiveness of this first volume is considerably larger than would appear at first glance. It has been purposely given a sub-title, in order that the peculiar position of the Indian, in 1861, may be brought out in strong relief. He was enough inside the American Union to have something to say about secession and enough outside of it to be approached diplomatically. It is well to note, indeed, that Albert Pike negotiated the several Indian treaties that bound the Indian nations in an alliance with the seceded states, under the authority of the Confederate State Department, which was a decided advance upon United States practice—an innovation, in fact, that marked the tremendous importance that the Confederate government attached to the Indian friendship. It was something that stood out in marked contrast to the indifference manifested at the moment by the authorities at Washington; for, while[Pg 14] they were neglecting the Indian even to an extent that amounted to actual dishonor, the Confederacy was offering him political integrity and political equality and was establishing over his country, not simply an empty wardship, but a bona fide protectorate.

Granting then that the negotiations of 1861 with the Indian nations constitute a phase of southern diplomatic history, it may be well to consider to what Indian participation in the Civil War amounted. It was a circumstance that was interesting rather than significant; and the majority will have to admit that it was a circumstance that could not possibly have materially affected the ultimate situation. It was the Indian country, rather than the Indian owner, that the Confederacy wanted to be sure of possessing; for Indian Territory occupied a position of strategic importance, from both the economic and the military point of view. The possession of it was absolutely necessary for the political and the institutional consolidation of the South. Texas might well think of going her own way and of forming an independent republic once again, when between her and Arkansas lay the immense reservations of the great tribes. They were slaveholding tribes, too, yet were supposed by the United States government to have no interest whatsoever in a sectional conflict that involved the very existence of the “peculiar institution.” Thus the federal government left them to themselves at the critical moment and left them, moreover, at the mercy of the South, and then was indignant that they betrayed a sectional affiliation.

The author deems it of no slight advantage, in undertaking a work of this sort, that she is of British birth and antecedents and that her educational training, so largely American as it is, has been gained without [Pg 15]respect to a particular locality. She belongs to no section of the Union, has lived, for longer or shorter periods in all sections, and has developed no local bias. It is her sincere wish that no charge of prejudice can, in ever so small a degree, be substantiated by the evidence, presented here or elsewhere.

Annie Heloise Abel.

Baltimore, September, 1914

Veterans of the Confederate service who saw action along the Missouri-Arkansas frontier have frequently complained, in recent years, that military operations in and around Virginia during the War between the States receive historically so much attention that, as a consequence, the steady, stubborn fighting west of the Mississippi River is either totally ignored or, at best, cast into dim obscurity. There is much of truth in the criticism but it applies in fullest measure only when the Indians are taken into account; for no accredited history of the American Civil War that has yet appeared has adequately recognized certain rather interesting facts connected with that period of frontier development; viz., that Indians fought on both sides in the great sectional struggle, that they were moved to fight, not by instincts of savagery, but by identically the same motives and impulses as the white men, and that, in the final outcome, they suffered even more terribly than did the whites. Moreover, the Indians fought as solicited allies, some as nations, diplomatically approached. Treaties were made with them as with foreign powers and not in the farcical, fraudulent way that had been customary in times past. They promised alliance and were given in return political position—a fair exchange. The southern white man, embarrassed, conceded much, far more than he really believed in, more than he ever could or would have conceded, had he not himself been[Pg 18] so fearfully hard pressed. His own predicament, the exigencies of the moment, made him give to the Indian a justice, the like of which neither one of them had dared even to dream. It was quite otherwise with the northern white man, however; for he, self-confident and self-reliant, negotiated with the Indian in the traditional way, took base advantage of the straits in which he found him, asked him to help him fight his battles, and, in the selfsame moment, plotted to dispossess him of his lands, the very lands that had, less than five and twenty years before, been pledged as an Indian possession “as long as the grass should grow and the waters run.”

From what has just been said, it can be easily inferred that two distinct groups of Indians will have to be dealt with, a northern and a southern; but, for the present, it will be best to take them all together. Collectively, they occupied a vast extent of country in the so-called great American desert. Their situation was peculiar. Their participation in the war, in some capacity, was absolutely inevitable; but, preparatory to any right understanding of the reasons, geographical, institutional, political, financial, and military, that made it so, a rapid survey of conditions ante-dating the war must be considered.

It will be remembered that for some time prior to 1860 the policy[1] of the United States government had been to relieve the eastern states of their Indian inhabitants and that this it had done, since the first years of[Pg 19] Andrew Jackson’s presidency, by a more or less compulsory removal to the country lying immediately west of Arkansas and Missouri. As a result, the situation there created was as follows: In the territory comprehended in the present state of Kansas, alongside of indigenous tribes, like the Kansa and the Osage,[2] had been placed various tribes or portions of tribes from the old Northwest[3]—the Shawnees and Munsees from Ohio,[4] the Delawares, Kickapoos, Potawatomies, and Miamies from Indiana, the Ottawas and Chippewas from Michigan, the Wyandots from Ohio and Michigan, the Weas, Peorias, Kaskaskias, and Piankashaws from Illinois, and a few New York Indians from Wisconsin. To the southward of all of those northern tribal immigrants and chiefly beyond the later Kansas boundary, or in the present state of Oklahoma, had been similarly placed the great[5] tribes from the South[6]—the Creeks from[Pg 20] Georgia and Alabama, the Cherokees from Tennessee and Georgia, the Seminoles from Florida, and the Choctaws and Chickasaws from Alabama and Mississippi.[7] The population of the whole country thus colonized[Pg 21] and, in a sense, reduced to the reservation system, amounted approximately to seventy-four thousand souls, less than seven thousand of whom were north of the Missouri-Compromise line. The others were all south of it and, therefore, within a possible slave belt.

This circumstance is not without significance; for it is the colonized, or reservation, Indians[8] exclusively that are to figure in these pages and, since this story is a chapter in the struggle between the North and the South, the proportion of southerners to northerners among the Indian immigrants must, in the very nature of things, have weight. The relative location of northern and southern tribes seems to have been determined with a very careful regard to the restrictions of the Missouri Compromise and the interdicted line of thirty-six degrees and thirty minutes was pretty nearly the boundary between them.[9] That it was so by accident may or may not be subject for conjecture. Fortunately for the disinterested motives of politicians but most unfortunately for the defenceless Indians, the Cherokee land obtruded itself just a little above the thirty-seventh parallel and formed a “Cherokee Strip” eagerly coveted by Kansans in later days. One objection, be it remembered, that had been offered to the original plan of removal was that, unless the slaveholding southern Indians were moved directly westward along parallel[Pg 22] lines of latitude, northern rights under the Missouri Compromise would be encroached upon. Yet slavery was not conscientiously excluded from Kansas in the days antecedent to its organization as a territory. Within the Indian country, and it was all Indian country then, slavery was allowed, at least on sufferance, both north and south of the interdicted line. It was even encouraged by many white men who made their homes or their living there, by interlopers, licensed traders, and missionaries;[10] but it flourished as a legitimate institution only among the great tribes planted south of the line. With them it had been a familiar institution long before the time of their exile. In their native haunts they had had negro slaves as had had the whites and removal had made no difference to them in that particular. Since the beginning of the century refuge to fugitives and confusion of ownership had been occasions for frequent quarrel between them and the citizens of the Southern States. Later, when questions came up touching the status of slavery on strictly federal soil, the Indian country and the District of Columbia often found themselves listed together.[11] Moreover, after 1850, it became a matter of serious import whether or no the Fugitive Slave Law was operative within the Indian country; and, when influenced apparently by Jefferson Davis, Attorney-general Cushing gave as his opinion that it was, new controversies arose. Slaves belonging[Pg 23] to the Indians were often enticed away by the abolitionists[12] and still more often were seized by southern men under pretense of their being fugitives.[13] In cases of the latter sort, the Indian owners had little or no redress in the federal courts of law.[14]

[Pg 24]In point of fact, during all the years between the various dates of Indian removal and the breaking out of the Civil War, the Indian country was constantly beset by difficulties. Some of the difficulties were incident to removal or to disturbances within the tribes but most of them were incident to changes and to political complications in the white man’s country. Scarcely had the removal project been fairly launched and the first Indian emigrants started upon their journey westward than events were in train for the overthrow of the whole scheme.

Map showing free Negro Settlements in the Creek country

[From Office of Indian Affairs]

[Pg 27]When Calhoun mapped out the Indian country in his elaborate report of 1825, the selection of the trans-Missouri region might well have been regarded as judicious. Had the plan of general removal been adopted then, before sectional interests had wholly vitiated it, the United States government might have gained and, in a measure, would have richly deserved the credit of doing at least one thing for the protection and preservation of the aborigines from motives, not self-interested, but purely humanitarian. The moment was opportune. The territory of the United States was then limited by the confines of the Louisiana Purchase and its settlements by the great American desert. Traders only had penetrated to any considerable extent to the base of the Rockies; but experience already gained might have taught that their presence was portentous and significant of the need of haste; that is, if Calhoun’s selection were to continue judicious; for traders, as has been amply proved in both British and American history, have ever been but the advance agents of settlers.

Unfortunately for the cause of pure philanthropy, the United States government was exceedingly slow in[Pg 28] adopting the plan of Indian removal; but its citizens were by no means equally slow in developing the spirit of territorial expansion. Their successful seizure of West Florida had fired their ambition and their cupidity. With Texas annexed and lower Oregon occupied, the selection of the trans-Missouri region had ceased to be judicious. How could the Indians expect to be secure in a country that was the natural highway to a magnificent country beyond, invitingly open to settlement! But this very pertinent and patent fact the officials at Washington singularly failed to realize and they went on calmly assuring the Indians that they should never be disturbed again, that the federal government would protect them in their rights and against all enemies, that no white man should be allowed to intrude upon them, that they should hold their lands undiminished forever, and that no state or territorial lines should ever again circumscribe them. Such promises were decidedly fatuous, dead letters long before the ink that recorded them had had time to dry. The Mexican War followed the annexation of Texas and its conquests necessitated a further use of the Indian highway. Soldiers that fought in that war saw the Indian land and straightway coveted it. Forty-niners saw it and coveted it also. Prospectors and adventurers of all sorts laid plans for exploiting it. It entered as a determining factor into Benton’s great scheme for building a national road that should connect the Atlantic and Pacific shores and with the inception of that came a very sudden and a very real danger; for the same great scheme precipitated, although in an indirect sort of way, the agitation for the opening up of Kansas and Nebraska to white settlement, which, of course, meant that the recent Indian colonists, in spite of all the solemn[Pg 29] governmental guaranties that had been given to them, would have to be ousted, for would not the “sovereign” people of America demand it? Then, too, the Dred Scott decision, the result of a dishonorable political collusion as it was,[15] militated indirectly against Indian interests. It is true that it was only in its extra-legal aspect that it did this but it did it none the less; for, if the authority of the federal government was not supreme in the territories and not supreme in any part of the country not yet organized into states, then the Indian landed property rights in the West that rested exclusively upon federal grant, under the Removal Act of 1830, were virtually nil. It is rather interesting to observe, in this connection, how inconsistent human nature is when political expediency is the thing at stake; for it happened that the same people and the same party, identically, that, in the second and third decades of the nineteenth century, had tried to convince the Indians, and against their better judgment too, that the red man would be forever unmolested in the western country because the federal government owned it absolutely and could give a title in perpetuity, argued, in the fourth and fifth decades, that the states were the sole proprietors, that they were, in fact, the joint owners of everything heretofore considered as national. Inferentially, therefore, Indians, like negroes, had no rights that white men were bound to respect.

The crucial point has now been reached in this discussion. From the date of the Kansas-Nebraska Bill, the sectional affiliation of the Indian country became a thing of more than passing moment. Whatever may have been John C. Calhoun’s ulterior and real motive[Pg 30] in urging that the trans-Missouri region be closed to white settlement forever, whether he did, as some of his abolitionist enemies have charged, plan thus to block free-state expansion and so frustrate the natural operations of the Missouri Compromise, certain it is, that southern politicians, after his time, became the chief advocates of Indian territorial integrity, the ones that pleaded most often and most noisily that guaranties to Indians be faithfully respected. They had in mind the northern part of the Indian country and that alone; but, no doubt, the circumstance was purely accidental, since at that time, the early fifties, the northern[16] was the only part likely to be encroached upon.[17] Their interest in the southern part took an entirely different direction[Pg 31] and that also may have been accidental or occasioned by conditions quite local and present. For this southern part, by the way, they recommended American citizenship and the creation of American states[18] in the Union,[Pg 32] also a territorial organization immediately that should look towards that end. Such advice came as early as 1853, at least, and was more natural than would at first glance appear; for the southern tribes were huge in population, in land, and in resources. They were civilized, had governments and laws modelled upon the[Pg 33] American, and more than all else, they were southern in origin, in characteristics, and in institutions.

The project for organizing[19] the territories of Kansas and Nebraska caused much excitement, as well it might,[Pg 34] among the Indian immigrants, even though the Wyandots, in 1852, had, in a measure, anticipated it by initiating a somewhat similar movement in their own restricted locality.[20] Most of the tribes comprehended to the full the ominous import of territorial organization; for, obviously, it could not be undertaken except at a sacrifice of Indian guaranties. At the moment some of the tribes, notably the Choctaw and Chickasaw,[21] were having domestic troubles that threatened a neighborhood war and the new fear of the white man’s further aggrandizement threw them into despair. The southern Indians, generally, were much more exercised and much more alarmed than were the northern.[22] Being more highly civilized, they were better able to comprehend the drift of events. Experience had made them unduly sagacious where their territorial and treaty rights were concerned, and well they knew that, although the Douglas measure did not in itself directly affect them or their country, it might easily become the forerunner of one that would.

The border strife, following upon the passage of the[Pg 35] Kansas-Nebraska Bill, disturbed in no slight degree the Indians on the Kansas reservations, which, by-the-by, had been very greatly reduced in area by the Manypenny treaties of 1853-1854. Some of the reserves lay right in the heart of the contested territory, free-state men intrenching themselves among the Delawares and pro-slavery men among the Shawnees,[23] the former north and the latter south of the Kansas River. But even remoteness of situation constituted no safeguard against encroachment. All along the Missouri line the squatters took possession. The distant Cherokee Neutral Lands[24] and the Osage and New York Indian reservations[25] were all invaded.[26] The Territorial Act had expressly excluded Indian land from local governmental control; but the Kansas authorities of both parties utterly ignored, in their administration of affairs, this provision. The first districting of the territory for election purposes comprehended, for instance, the Indian lands, yet little criticism has ever been passed[Pg 36] upon that grossly illegal act. Needless to say, the controversy between slavocracy and freedom obscured and obliterated, in those years, all other considerations.

As the year 1860 approached, appearances assumed an even more serious aspect. Kansas settlers and would-be settlers demanded that the Indians, so recently the only legal occupants of the territory, vacate it altogether. So soon had the policy of granting them peace and undisturbed repose on diminished reserves proved futile. The only place for the Indian to go, were he indeed to be driven out of Kansas, was present Oklahoma; but his going there would, perforce, mean an invasion of the property rights of the southern tribes, a matter of great moment to them but seemingly of no moment whatsoever to the white man. Some of the Kansas Indians saw in removal southward a temporary refuge—they surely could not have supposed it would be other than temporary—and were glad to go, making their arrangements accordingly.[27] Some, however, had to be cajoled into promising to go and some had to be forced. A few held out determinedly against all thought of going. Among the especially obstinate ones were the Osages,[28] natives of the soil. The Buchanan[Pg 37] government failed utterly to convince them of the wisdom of going and was, thereupon, charged by the free-state Kansans with bad faith, with not being sincere and sufficiently persistent in its endeavors to treat, its secret purpose being to keep the free-state line as far north as possible. The breaking out of the Civil War prevented the immediate removal of any of the tribes but did not put a stop to negotiations looking towards that end.

All this time there was another influence within the Indian country, north and south, that boded good or ill as the case might be. This influence emanated from the religious denominations represented on the various reserves. Nowhere in the United States, perhaps, was the rivalry among churches that had divided along sectional lines in the forties and fifties stronger than within the Indian country. There the churches contended with each other at close range. The Indian country was free and open to all faiths, while, in the states, the different churches kept strictly to their own sections, the southern contingent of each denomination staying close to the institution it supported. Of course the United States government, through its civilization fund, was in a position to show very pointedly its sectional predilections. It will probably never be known, because so difficult of determination, just how much the churches aided or retarded the spread of slavery.[29]

Among the tribes of Kansas, denominational strength was distributed as follows: The Kickapoos[30] and[Pg 38] Wyandots[31] were Methodists; but, while the former were a unit in their adherence to the Methodist Episcopal Church South, the latter were divided and among them the older church continued strong. The American Baptist Missionary Union had a school on the Delaware reservation and, previous to 1855, had had one also on the Shawnee, which the political uproar in Kansas had obliged to close its doors. These same Northern Baptists were established also among the Ottawas, as the Moravians were among the Munsees and the Roman Catholics[32] among the Osages and the Potawatomies. The Southern Baptists were likewise to be found among the Potawatomies[33] and the Southern Methodists among the Shawnees. The Shawnee Manual Labor School, under the Southern Methodists, was, however, only very grudgingly patronized by the Indians. Its situation near the Missouri border was partly accountable for this as it was for the selection of the school as the meeting-place of the pro-slavery legislature in 1855. The management of the institution was from time to time severely criticized and the [Pg 39]superintendent, the Reverend Thomas Johnson, an intense pro-slavery agitator,[34] was strongly suspected of malfeasance,[35] of enriching himself, forsooth, at the expense of the Indians. The school found a formidable rival, from this and many another cause, in a Quaker establishment, which likewise existed on the Shawnee Reserve but independently of either tribal or governmental aid.

If church influences and church quarrels were discernible among the northern tribes, they were certainly very much more so among the southern. The American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions (Congregational) that had labored so zealously for the Cherokees, when they were east of the Mississippi, extended its interest to them undiminished in the west; and, in the period just before the Civil War,[36] was the strongest religious force in their country. There it had no less than four mission stations[37] and a flourishing school in connection with each. The same organization was similarly influential among the Choctaws[38] or, in the light of what eventually happened, it might better be said its missionaries were. Both Southern and Northern Baptists and Southern Methodists likewise were to be found among the Cherokees;[39] Presbyterians[40] and[Pg 40] Southern Methodists among the Chickasaws and Choctaws; and Presbyterians only among the Creeks and Seminoles. In every Indian nation south, except the Creek and Seminole,[41] the work of denominational schools was supplemented, or maybe neutralized, by that of public and neighborhood schools.

True to the traditions and to the practices of the old Puritans and of the Plymouth church, the missionaries of the American Board,[42] so strongly installed among the Choctaws and the Cherokees, took an active interest in passing political affairs, particularly in connection with the slavery agitation. On that question, they early divided themselves into two camps; those among the Choctaws, led by the Reverend Cyrus Kingsbury,[43][Pg 41] supporting slavery; and those among the Cherokees, led by the Reverend S. A. Worcester,[44] opposing it. The actions of the former led to a controversy with the American Board and, in 1855, the malcontents, or pro-slavery sympathizers, expressed a desire to separate themselves and their charges from its patronage.[45] When, eventually, this separation did occur, 1859-1860, the Presbyterian Board of Foreign Missions (Old School) stepped into the breach.[46]

The rebellious conduct of the Congregational missionaries met with the undisguised approval of the Choctaw agent, Douglas H. Cooper,[47] formerly of Mississippi. It was he who had already voiced a nervous apprehension, as exhibited in the following document,[48] that the Indian country was in grave danger of being abolitionized:

☞ If things go on as they are now doing, in 5 years slavery will be abolished in the whole of your superintendency.

(Private) I am convinced that something must be done speedily to arrest the systematic efforts of the Missionaries to abolitionize the Indian Country.

Otherwise we shall have a great run-away harbor, a sort of[Pg 42] Canada—with “underground rail-roads” leading to & through it—adjoining Arkansas and Texas.

It is of no use to look to the General Government—its arm is paralized by the abolition strength of the North.

I see no way except secretly to induce the Choctaws & Cherokees & Creeks to allow slave-holders to settle among their people & control the movement now going on to abolish slavery among them.

C—

Cooper sent this note, in 1854, as a private memorandum to the southern superintendent, who at the time was Charles W. Dean. In 1859, it was possible for him to write to Dean’s successor, Elias Rector, in a very different tone. The missionaries had then taken the stand he himself advocated and there was reason for congratulation. Under such circumstances, Cooper wrote,

I cannot close this report without calling your attention to the admirable tone and feeling pervading the reports of superintendents of schools and missionaries among the Choctaws, and particularly to that of the Rev. Ebenezer Hotchkin, one of the oldest missionaries among the Choctaws, who, in referring to past political disturbances, says: “We have looked upon our rulers as the ‘powers that be, are ordained of God,’ and have respected them for this reason. ‘Whomsoever, therefore, resisteth the power resisteth the ordinance of God’ (Romans, xiii, 2). This has been our rule of action during the political excitement. We believe that the Bible is the best guide for us to follow. Our best citizens are those most influenced by Bible truth.”

I rejoice to believe the above sentiments are entertained by most, if not all, the missionaries now among the Choctaws and Chickasaws, and that they entirely repudiate the higher-law doctrine[49] of northern and religious fanatics. It is but lately, as I learn, that the Choctaw mission, for many years under the control of the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions (whose headquarters are at Boston) has been cut off, [Pg 43]because they preferred to follow the teachings of the Bible, as understood by them, rather than obey the dogmas contained in Dr. Treat’s letter and the edicts of the parent board.

It is a matter of congratulation among the friends of the old Choctaw missionaries, who have labored for thirty years among them, and intend to die with armor on, that all connection with the Boston board has been dissolved. If it had been done years ago, when their freedom of conscience and of missionary action was attempted to be controlled by the parent board, much of suspicion, of ill-feeling, and diminished usefulness, which attached to the Choctaw missionaries in consequence of their connection with and sustenance by a board avowedly and openly hostile to southern institutions, would have been prevented.[50]

[Pg 44 & 45]In the next year, 1860, Cooper was still sanguine as to affairs among the Indians of his agency and he could report to Rector, unhesitatingly, as if confident of official endorsement both at Forth Smith and at Washington,[51]

Great excitement has prevailed along the Texas border, in consequence of the incendiary course pursued in that State by horse thieves and religious fanatics; but I am glad to say, as yet, so far as I am informed, no necessity has existed in this agency for the organization of “vigilance committees” ... No doubt we have among us free-soilers; perhaps abolitionists in sentiment; but, so far as I am informed, persons from the North, residing among the Choctaws and Chickasaws, who entertain opinions unfriendly to our system of domestic slavery, keep their opinions to themselves and attend to their legitimate business.[52]

George Butler, the United States agent for the Cherokees, seems to have been, no less than Cooper, an adherent of the State Rights Party and an upholder of the[Pg 46] institution of slavery. In 1859, he ascribed the very great material progress of the Cherokees to the fact that they were slaveholders.[53] Slavery, in Butler’s opinion, had operated as an incentive to all industrial pursuits. To an extent this may have been true, since all Indians, no matter how high their type, have an aversion for work. As Professor Shaler once said, they are the truest aristocrats the world has ever known. But the slaveholders among the great tribes of the South were, for the most part, the half-breeds, the cleverest and often, much as we may regret to have to admit it, the most unscrupulous men of the community.

Butler’s commission as Indian agent expired in March, 1860, and he was not reappointed, Robert J. Cowart of Georgia[54] being preferred. This man, illiterate and unprincipled, immediately set to work to perform a task to which his predecessor had proved unequal. The task was the removal of white intruders from the Cherokee country. For some time past, the southern superintendent and the agents under him, to say nothing of Commissioner Greenwood and Secretary Thompson, the one a citizen of Arkansas and the other of Mississippi, had resented most bitterly the invasion of the Cherokee Neutral Lands by Kansas free-soilers and the division of it into counties by the unlawfully assumed authority of the Kansas legislature. The resentment was thoroughly justifiable; for the whole proceeding of the legislature was contrary to the express enactment of Congress; but no doubt, enthusiasm for the strict enforcement of the federal law came largely from political predilections, precisely as the Kansan’s[Pg 47] outrageous defiance of it came from a deep-rooted distrust of the Buchanan administration.

There were, however, other intruders that Cowart and Rector and Greenwood designed to remove and they wanted to remove them on the ground that they were making mischief within the tribe and interfering with its institutions, or, more specifically, with slavery. The intruders meant were principally the missionaries against whom Greenwood had even the audacity to lay the charge of inciting to murder. Newspapers of bordering slave states were full of criticism,[55] just before the war, of these same men and, notably, of the Reverend Evan[56] and John Jones, the reputed ringleaders.[Pg 48] The official excuse for removing them is rather interesting because it is so similar to that given, some thirty years earlier, in connection with the removal from Georgia. Ulterior motives can so easily be hidden under cold official phrase.

That the cause of slavery within the Cherokee country was in jeopardy in the spring and summer of 1860 can not well be denied. To the men of the time the evidence was easily obtainable. Almost as if by magic, a “search organization” started up among the full-bloods, an organization profoundly secret in its membership and in its purposes, but believed to be for no other object than the overthrow of the “peculiar institution.” Its existence was promptly reported to the United States government and, as was to be expected, the missionaries were held responsible for both its inception and its continuance. It was then that Greenwood made[57] his most serious charge against these men and prepared, under color of law, to have them removed. Later, in this same year of 1860, Quantrill, the Hagerstown, Maryland man of Pennsylvania Dutch origin, who afterwards became such a notorious frontier guerrilla in the interests of the Confederate cause, leagued himself with some abolitionists for the sake of[Pg 49] making an expedition to the Cherokee country and rescuing negroes, there held in bondage.[58] The timely distrust of Quantrill, however, caused the enterprise to be abandoned even before its preliminaries had been thoroughly well arranged; yet, had the rescue been carried to completion, it would not have been entirely without precedent[59] and its very contrivance indicated an uncertainty and a precariousness of situation south of the Kansas line.

Ever since their compulsory removal from Georgia under circumstances truly tragic, the Cherokees had been much given to factional strife. This was largely in consequence of the underhand means taken by the state and federal authorities to accomplish removal. The Cherokees had, under the necessities of the situation, divided themselves into the Ross, or Anti-removal Party, and the Ridge, or Treaty Party.[60] Removal took place in spite of the steady opposition of the Rossites and the Cherokees went west, piloted by the United States army. Once in the west a new division arose in their ranks; for, as newcomers, they came into jealous contact with members of their tribe who had emigrated many years previously and who came to figure, in subsequent Cherokee history, as the Old Settlers’ Party.[61] In 1846, the United States government attempted to assume the role of mediator in a settlement of Cherokee tribal differences but without much success.[62] The old wrongs were unredressed, so the old divisions remained[Pg 50] and formed nuclei for new disintegrating issues. Thus, in 1857, there were no less than three factions created in consequence of a project for selling the Cherokee Neutral Lands[63]. Each faction had its own opinion how best to dispose of the proceeds, should a sale take place. In 1860, there were two factions, the selling and the non-selling[64]. This tendency of the Cherokees perpetually to quarrel among themselves and to bear long-standing grudges against each other is most important; inasmuch as that marked peculiarity of internal politics very largely determined the unique position of the tribe with reference to the Civil War.

The other great tribes had also occasions for quarrel in these same critical years. The disgraceful circumstances of their removal had widened the gulf, once simply geographical, between the Upper and the Lower Creeks. They were now almost two distinct political entities, in each of which there were a principal and a second chief. In 1833, provision had been made for the accommodation of the Seminoles within a certain definite part of the Creek country[65]—just such an arrangement, forsooth, as worked so ill when applied to the Choctaws and Chickasaws; but it took several years for the Seminoles to be suited. At length, when their numbers had been considerably augmented by the coming of the new immigrants from Florida, they took up[Pg 51] their position, for good and all, in the southwestern corner of the Creek Reserve, a politically distinct community. By that time, the Creeks seem to have repented of their generosity,[66] so, perhaps, it was well that the United States government had not yielded to their importunity and consented to a like settlement of the southern Comanches.[67] It had taken the Chickasaws a long time to reconstruct their government after the political separation from the Choctaws; but now they had a constitution,[68] all their own, a legislature, and a governor. The Choctaws had attempted a constitution, likewise, first the Scullyville, then the Doaksville, set up by a minority party; but they had retained some semblance of the old order of things in the persons of their chiefs.[69]

There were other Indians within the southern division of the Indian country that were to have their part in the Civil War and in events leading up to it or resulting from it. In the extreme northeastern corner, were the Quapaws, the Senecas, and the confederated Senecas and Shawnees, all members, with the Osages and the New York Indians of Kansas, of the Neosho River Agency which was under the care of Andrew J. Dorn. In the far western part, at the base of the Wichita Mountains, were the Indians of the Leased District,[Pg 52] Wichitas, Tonkawas,[70] Euchees, and others, collectively called the “Reserve Indians.” Most of them had been brought from Texas,[71] because of Texan intolerance of their presence, and placed within the Leased District, a tract of land west of the ninety-eighth meridian, which, under the treaty of 1855, the United States had rented from the Choctaws and Chickasaws. It was a part of the old Chickasaw District of the Choctaw Nation. Outside of the Wichita Reserve and still wandering at large over the plains were the hostile Kiowas and Comanches, against whom and the inoffensive Reserve Indians, the Texans nourished a bitter, undying hatred. They charged them with crimes that were never committed and with some crimes that white men, disguised as Indians, had committed. They were also suspected of manufacturing evidence that would incriminate the red men and of plotting, in regularly-organized meetings, their overthrow.[72]

Although the plan for colonizing some of the Texas Indians had been completed in 1855, the Indian Office found it impossible to execute it until the summer of 1859. This was principally because the War Department could not be induced to make the necessary military arrangements.[73] In point of fact, the southern [Pg 53]Indian country was, at the time, practically without a force of United States troops, quite regardless of the promise that had been made to all the tribes upon the occasion of their removal that they should always be protected in their new quarters and, inferentially, by the regular army. Even Fort Gibson had been virtually abandoned as a military post on the plea that its site was unhealthful; and all of Superintendent Rector’s recommendations that Frozen Rock, on the south side of the Arkansas a few miles away, be substituted[74] had been ignored, not so much by the Interior Department, as by the War. Secretary Thompson thought that enough troops should be at his disposal to enable him to carry out the United States Indian policy, but Secretary Floyd demurred. He was rather disposed to dismantle such forts as there were and to withdraw all troops from the Indian frontier,[75] a course of action that would leave it exposed, so the dissenting Thompson prognosticated, to “the most unhappy results.”[76]

It happened thus that, when the United States surveyors started in 1858 to establish the line of the ninety-eighth meridian west longitude and to run other boundary lines under the treaty of 1855,[77] they found the country entirely unpatrolled. Troops had been ordered from Texas to protect the surveyors; but, pending their arrival, Agent Cooper, who had gone out to witness the[Pg 54] determination of the initial point on the line between his agency and the Leased District, himself took post at Fort Arbuckle and called upon the Indians for patrol and garrison duty.[78] It would seem that Secretary Thompson had verbally authorized[79] Cooper to make this use of the Indians; but they proved in the sequel very inefficient as garrison troops. On the thirtieth of June, Lieutenant Powell, commanding Company E, First United States Infantry, arrived at Fort Arbuckle from Texas and relieved Cooper of his self-imposed task. The day following, Cooper set out upon a sixteen day scout of the Washita country, taking with him his Indian volunteers, Chickasaws[80] and a few Cherokees;[81] and for this act of using Indian after the arrival of white troops, he was severely criticized by the department. One thing he accomplished: he selected a site for the prospective Wichita Agency with the recommendation that it be also made the site[82] of the much-needed military post on the Leased District. The site had originally been occupied by a Kechie village and was admirably well adapted for the double purpose Cooper intended. It lay near the center of the Leased[Pg 55] District and near the sources of Cache and Beaver Creeks. It was also, so reported Cooper, “not very distant from the Washita, & Canadian” (and commanded) “the Mountain passes through the Wichita Mountains to the Antelope Hills—to the North branch of Red River and also the road on the South side of the Wichita Mountains up Red River.”

The colonization of the Wichitas and other Indians took place in the summer of 1859 under the excitement of new disputes with Texas, largely growing out of an unwarranted and brutal attack[83] by white men upon Indians of the Brazos Agency. That event following so closely upon the heels of Van Dorn’s[84] equally brutal attack upon a defenceless Comanche camp brought matters to a crisis and the government was forced to be expeditious where it had previously been dilatory. The Comanches had come in, under a flag of truce, to confer in a friendly way with the Wichitas. Van Dorn, ignorant of their purpose but supposing it hostile, made a forced march, surprised them, and mercilessly took summary vengeance for all the Comanches had been charged with, whether justly or unjustly, for some time past. After it was all over, the Comanches, with about sixty of their number slain, accused the Wichitas of having betrayed them. Frightened, yet innocent, the[Pg 56] Wichitas begged that there be no further delay in their removal, so the order was given and arrangements made. Unfortunately, by the time everything was ready, the season was pretty far advanced and the Indians reached their new home to find it too late to put in crops for that year’s harvest. Subsistence rations had, therefore, to be doled out to them, the occasion affording, as always, a rare opportunity for graft. Instead of calling for bids, as was customary, Superintendent Rector entered into a private contract[85] with a friend and relative of his own, the consequence being that the government was charged an exorbitant price for the rations. Soon other troubles[86] came. The Leased District proved to be already occupied by some northern Indian refugees[87] and became, as time went on, a handy [Pg 57]rendezvous for free negroes; but, as soon as Matthew Leeper[88] of Texas became agent, the stay of such was extremely short.[89]

Such were the conditions obtaining among the Indians west of Missouri and Arkansas in the years immediately antedating the American Civil War; and, from such conditions, it may readily be inferred that the Indians were anything but satisfied with the treatment that had been and was being accorded them. They owed no great debt of gratitude to anybody. They were restless and unhappy among themselves. Their old way of living had been completely disorganized. They had nothing to go upon, so far as their relations with the white men were concerned, to make them hopeful of anything better in the future, rather the reverse. Indeed at the very opening of the year 1860, a year so full of distress to them because of the great drouth[90] that ravaged [Pg 58]Nebraska, Kansas, and Oklahoma, the worst that had been known in thirty years, there came occasion for a new distrust. Proposals were made to the Creeks,[91] to the Choctaws,[92] and to the Chickasaws to allot their lands in severalty, notwithstanding the fact that one of the inducements offered by President Jackson to get them originally to remove had been, that they should be permitted to hold their land, as they had always held it, in common, forever. The Creeks now replied to the proposals of the Indian Office that they had had experience with individual reservations in their old eastern homes and had good reason to be prejudiced against them. The Indians, one and all, met the proposals with a downright refusal but they did not forget that they had been made, particularly when there came additional cause for apprehension.

The cause for apprehension came with the presidential campaign of 1860 and from a passage in Seward’s Chicago speech,[93] “The National Idea; Its Perils and Triumphs,” expressive of opinions, false to the national trust but favorable to expansion in the direction of the Indian territory, most inopportune, to say the least, and foolish. Seward probably spoke in the enthusiasm of a heated moment; for the obnoxious sentiment, “The Indian territory, also, south of Kansas, must be vacated by the Indians,” was very different in its tenor from equally strong expressions in his great Senate speech[94][Pg 59] on the Kansas-Nebraska Bill, February 17, 1854. It soon proved, however, easy of quotation by the secessionists in their arguments with the Indians, it being offered by them as incontestable proof that the designs of the incoming administration were, in the highest degree, inimical to Indian treaty rights. At the time of its utterance, the Indians were intensely excited. The poor things had had so many and such bitter experiences with the bad faith of the white people that it took very little to arouse their suspicion. They had been told to contract their domain or to move on so often that they had become quite super-sensitive on the subject of land cessions and removals. Seward’s speech was but another instance of idle words proving exceedingly fateful.

Two facts thus far omitted from the general survey and reserved for special emphasis may now be remarked upon. They will show conclusively that there were personal and economic reasons why the Indians, some of them at least, were drawn irresistibly towards the South. The patronage of the Indian Office has always been more or less of a local thing. Communities adjoining Indian reservations usually consider, and with just cause because of long-established practice, that all positions in the field service, as for example, agencies and traderships, are the perquisites, so to speak, of the locality. It was certainly true before the war that Texas and Arkansas had some such understanding as to Indian Territory, for only southerners held office there and, from among the southerners, Texans and Arkansans received the preference always. It happened too that the higher officials in Washington were almost invariably southern men.

The granting of licenses to traders rested with the[Pg 60] superintendent and everything goes to show that, in the fifties and sixties, applications for license were scrutinized very closely by the southern superintendents with a view to letting no objectionable person, from the standpoint of southern rights, get into the territory. The Holy See itself could never have been more vigilant in protecting colonial domains against the introduction of heresy. The same vigilance was exercised in the hiring of agency employees, blacksmiths, wheelwrights, and the like. Having full discretionary power in the premises, the superintendents could easily interpret the law to suit themselves. They could also evade it in their own interests and frequently did so. One notorious case[95] of this sort came up in connection with Superintendent Drew, who gave permits to his friends to “peddle” in the Indian country without requiring of them the necessary preliminary of a bond. Traders once in the country had tremendous influence with the Indians, especially with those of a certain class whom ordinarily the missionaries could not reach. Then, as before and since, Indian traders were not men of the highest moral character by any means. Too often, on the contrary, they were of degraded character, thoroughly unscrupulous, proverbial for their defiance of the law, general illiteracy, and corrupt business practices. It stands to reason that such men, if they had themselves been selected with an eye single to the cause of a particular section and knew that solicitude in its interests would mean great latitude to themselves and favorable reports of themselves to the department at Washington, would spare no efforts and hesitate at no means to make it their first concern, provided, of course, that it did not interfere with their own monetary schemes.

[Pg 61]To cap the climax, the last and greatest circumstance to be noted, if only because of the great weight it carried with the Indians when it was brought into the argument by the secessionists, is that practically all of the Indian money held in trust for the individual tribes by the United States government was invested in southern stocks;[96] in Florida 7’s, in Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maryland, South Carolina, Missouri, Virginia, and Tennessee 6’s, in North Carolina and Tennessee 5’s, and the like. To tell the truth, only the merest minimum of it was secured by northern bonds. The southerners asserted for the Indians’ benefit, that all these securities would be forfeited[97] by the war. Sufficient[Pg 62] is the fact, that the position of the Indians[98] was unquestionably difficult. With so much to draw them southward, our only wonder is, that so many of them stayed with the North.

For the participation of the southern Indians in the American Civil War, the states of Texas and Arkansas were more than measurably responsible. Indian Territory, or that part of the Indian country that was historically known as such, lay between them. Its southern frontage was along the Red River; and that stream, flowing with only slight sinuosity downward to its junction with the Mississippi, gave to Indian Territory a long diagonal, controlled, as far as situation went, entirely by Texas. Texas lay on the other side of the river and she lay also on almost the whole western border of Indian Territory.[99] She was, consequently, in possession of a rare opportunity, geographically, for exercising influence, should need for such ever arise. Running parallel with the Red River and northward about one hundred miles, was the Canadian. Between the two rivers were three huge Indian reservations, the most western was the Leased District of the Wichitas and allied bands, the middle one was the Chickasaw, and the eastern, the Choctaw.[100] The Indian occupants of these three reservations were, therefore, and sometimes to their sorrow, be it said, the very next door neighbors[Pg 64] of the Texans. The Choctaws were, likewise, the next door neighbors of the Arkansans who joined them on the east; but the relations between Arkansans and Choctaws seem not to have been so close or so constant during the period before the war as were the relations between the Choctaws and the Texans on the one hand and the Cherokees and the Arkansans on the other.

The Cherokees dwelt, like the Choctaws, over against Arkansas but north of the Canadian River and in close proximity to Fort Smith, the headquarters of the Southern Superintendency.[101] Their territory was not so compactly placed as was the territory of the other tribes; and, in its various parts, it passes, necessarily, under various designations. There was the “Cherokee Outlet,” a narrow tract south of Kansas that had no definite western limit. It was supposed to be a passage way to the hunting grounds of the great plains beyond. Then there was the “Cherokee Strip,” the Kansas extension of the outlet, and for most of its extent originally and legally a part of it. The territorial organization of Kansas had made the two distinct. Finally, as respects the more insignificant portions of the Cherokee domain, there were the “Cherokee Neutral Lands,” already sufficiently well commented upon. They were insignificant, not in point of acreage but of tribal authority operating within them. They lay in the southeastern corner of Kansas and constituted, against their will and against the law, her southeastern counties. They were separated, to their own discomfiture and disadvantage, from the Cherokee Nation proper by the reservation of the Quapaws, of the Senecas, and of the confederated Senecas and Shawnees. This Cherokee Nation lay, as has already been indicated, over against Arkansas and north of the northeastern section of the Choctaw country. The Arkansas River formed part of the boundary between the two tribal domains. So much then for the location of the really great tribes, but where were the lesser?

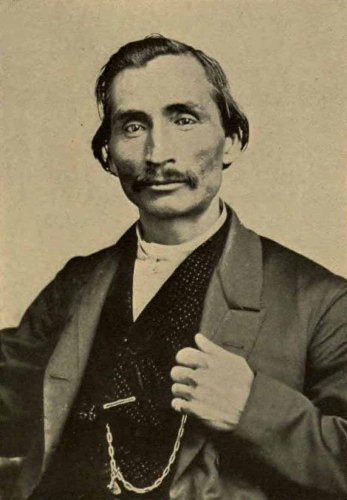

Colonel Downing, Cherokee

[From Smithsonian Institution, Bureau of American Ethnology]

[Pg 67]The Quapaws, the Senecas, and the confederated Senecas and Shawnees, the most insignificant of the lesser, occupied the extreme northeastern corner of Indian Territory and, therefore, bordered upon the southwestern corner of Missouri. The Creeks lived between the Arkansas River, inclusive of its Red Fork, and the Canadian River, having the Cherokees to the east and north of them, the Choctaws and Chickasaws to the south, and the Seminoles to the southwest, between the Canadian and its North Fork. The Indians of the Leased District have already been located.

In the years preceding the Civil War, the interest of Texas and of Arkansas in Indian Territory manifested itself, not in a covetous desire to dispossess the Indians of their lands, as was, unfortunately for national honor, the case in Kansas, but in an effort to keep the actual country true to the South, settled by slaveholders, Indian or white, as occasion required or opportunity offered. When sectional affairs became really tense after the formation of the Republican Party, they redoubled their energies in that direction, working always through the rich, influential, and intelligent half-breeds, some of whom had property interests and family connections in the states operating upon them.[102] The half-breeds were essentially a planter class, institutionally more[Pg 68] truly so than were the inhabitants of the border slave states. It is therefore not surprising that, during the excitement following Abraham Lincoln’s nomination and election, identically the same political agencies worked among them as among their white neighbors and events in Indian Territory kept perfect pace with events in adjoining states.

The first of these that showed strong sectional tendencies came in January, 1861, when the Chickasaws, quite on their own initiative apparently, met in a called session of their legislature to consider how best the great tribes might conduct themselves with reference to the serious political situation then shaping itself in the United States. There is some evidence that the Knights of the Golden Circle had been active among the Indians as they had been in Arkansas[103] during the course of the late presidential campaign. At all events, the red men knew full well of passing occurrences among their neighbors and they certainly knew how matters were progressing in Texas. There the State Rights Party was asserting itself in no doubtful terms. For the time being, however, the Chickasaws contented themselves with simply passing an act,[104] January 5, suggesting[Pg 69 & 70] an inter-tribal conference and arranging for the executive appointment of a Chickasaw delegation to it. The authorities of the other tribes were duly notified[105] and to the Creek was given the privilege of naming time and place.

The Inter-tribal Council assembled at the Creek[Pg 71] Agency,[106] February 17, but comparatively few delegates were in attendance. William P. Ross, a graduate[107] of Princeton and a nephew of John Ross, the principal chief of the Cherokees, went as the head of the Cherokee delegation. It was he who reported the scanty attendance,[108] saying that there were no Chickasaws present, no Choctaws, but only Creeks, Seminoles, and Cherokees. Why it happened so can not now be exactly determined but to it may undoubtedly be ascribed the outcome; for the council did nothing that was not perfectly compatible with existing friendly relations between the great tribes and the United States government. John Ross, in instructing his delegates, had strictly enjoined caution and discretion[109]. William P. Ross and his associates seem to have managed to secure[Pg 72] the observance of both. Perchance it was Chief Ross’s[110] known aversion to an interference in matters that did not concern the Indians, except very indirectly, and the consciousness that his influence in the council would be immense, probably all-powerful, that caused the Chickasaws to draw back from a thing they had themselves so ill-advisedly planned. It is, however, just possible that, between the time of issuing the call and of assembling the council, they crossed on their own responsibility the boundary of indecision and resolved, as most certainly had the Choctaws, that their sympathies and their interests were with the South. It might well be supposed that in this perilous hour their thoughts would have travelled back some thirty years and they would have remembered what havoc the same state-rights doctrine, now presented so earnestly for their acceptance, although it scarcely fitted their case, had then wrought in their concerns. Strangely enough none of the tribes seems to have charged the gross injustice of the thirties exclusively to the account of the South. On the contrary, they one and all charged it against the federal government, against the states as a whole, and so, rightly or wrongly, the nation had to pay for the inconsistency of Jackson’s procedure, a procedure that could so illogically recognize the supremacy of federal law in one matter and the supremacy of state law in another matter that was precisely its parallel.

The decision of the Choctaws had found expression in a series of resolutions under date of February 7. They are worthy of being quoted entire.

[Pg 73]February 7, 1861.

Resolutions expressing the feelings and sentiments of the General Council of the Choctaw Nation in reference to the political disagreement existing between the Northern and Southern States of the American Union.

Resolved by the General Council of the Choctaw Nation assembled, That we view with deep regret and great solicitude the present unhappy political disagreement between the Northern and Southern States of the American Union, tending to a permanent dissolution of the Union and the disturbance of the various important relations existing with that Government by treaty stipulations and international laws, and portending much injury to the Choctaw government and people.

Resolved further, That we must express the earnest desire and ready hope entertained by the entire Choctaw people, that any and all political disturbances agitating and dividing the people of the various States may be honorably and speedily adjusted; and the example and blessing, and fostering care of their General Government, and the many and friendly social ties existing with their people, continue for the enlightenment in moral and good government and prosperity in the material concerns of life to our whole population.

Resolved further, That in the event a permanent dissolution of the American Union takes place, our many relations with the General Government must cease, and we shall be left to follow the natural affections, education, institutions, and interests of our people, which indissolubly bind us in every way to the destiny of our neighbors and brethren of the Southern States upon whom we are confident we can rely for the preservation of our rights of life, liberty, and property, and the continuance of many acts of friendship, general counsel, and material support.

Resolved further, That we desire to assure our immediate neighbors, the people of Arkansas and Texas, of our determination to observe the amicable relations in every way so long existing between us, and the firm reliance we have, amid any disturbance with other States, the rights and feelings so sacred to us will remain respected by them and be protected from the encroachments of others.

Resolved further, That his excellency the principal chief be[Pg 74] requested to inclose, with an appropriate communication from himself, a copy of these resolutions to the governors of the Southern States, with the request that they be laid before the State convention of each State, as many as have assembled at the date of their reception, and that in such as have not they be published in the newspapers of the State.

Resolved, That these resolutions take effect and be in force from and after their passage.

Approved February 7, 1861.[111]

These resolutions of the Choctaw Council are in the highest degree interesting in the matter both of their substance and of their time of issue. The information is not forthcoming as to how the Choctaws received the invitation of the Chickasaw legislature to attend an inter-tribal council; but, later on, in April, 1861, the Choctaw delegation in Washington, made up of P. P. Pitchlynn, Samuel Garland, Israel Folsom, and Peter Folsom, assured the Commissioner of Indian Affairs that the Choctaw Nation intended to remain neutral,[112][Pg 75] which assurance was interpreted to mean simply that the Choctaws would be inactive spectators of events, expressing no opinion, in word or deed, one way or the other. The Chickasaw delegation gave the same assurance and at about the same time and place. Now what is to be concluded? Is it to be supposed that the Act of January 5, 1861 in no wise reflected the sentiments of a tribe as a whole and similarly the Resolutions of February 7, 1861, or that the tribal delegations were, in April, utterly ignorant of the real attitude of their respective constituents? The answer is to be found in the following most interesting and instructive letter, written by S. Orlando Lee to Commissioner Dole from Huntingdon, Long Island, March 15, 1862:[113]

Thinking you and the government would like to hear something about the state of affairs among the Choctaws last summer and the influences which induced them to take their present position I will write you what I know. I was a missionary teacher at Spencer Academy for two years and refer you to Hon. Walter Lowrie Gen. Sec. of the Pres. Board of Foreign Missions for information as to my character &c. I left Spencer June 13th & the nation June 24th but have heard directly from there twice since, the last time as late as Sept 6th. So that I can speak of occurrences as late as that.

After South Carolina passed her secession ordinance in Dec. 1860 there was a public attempt to excite the Choctaws and Chickasaws as a beginning hoping to bring in the other tribes afterwards. Many of the larger slaveholders (who are nearly all half breeds) had been gained before and Capt. R. M. Jones was the leader of the secessionists. The country was full of lies about the intentions of the new administration. The border papers in Arkansas & Texas republished from the New York & St. Louis papers a part of a sentence from Hon. W. H. Seward’s speech at Chicago during the election campaign of 1860 to this effect “And Indian Territory south of Kansas must be vacated by the Indian” (These words do occur in the report of Mr. Seward’s Chicago[Pg 76] speech as published in New York Evening Post Weekly for I read it myself). This produced intense excitement of course and to add to the effect the Secessionist Journals charged that another prominent republican had proposed to drive the indians out of Indian Ter. in a speech in congress. “This” they were told “is the policy of the new administration. The abolitionists want your lands—we will protect you. Your only safety is to join the South.” Again they were told “that the South must succeed in gaining their independence and the money of the indians being invested in the stocks of Southern states the stocks would be cancelled & the indians would lose their money unless they joined the south, if they did that the stocks would be reissued to the Confederate States for them.” Their special commissioners Peter Folsom &c., who came to Washington to get the half million of dollars for claims, reported that they got along very well until they were asked if they had slaves after that they said they could do nothing. Sampson Folsom said however that he thought they would have succeeded had it not been for the attack on Sumpter—He said President Lincoln then told them “He would not give them a dollar until the close of the war.” An interesting fact in relation to these commissioners is that they came to Washington by way of Montgomery & were when they reached Washington probably all, except Judge Garland, secessionists. Thus all influences were in favor of the rebels—Where could the indians go for light—The former indian agent Cooper was a Col. in the rebel service. The oldest missionary who has undoubtedly more influence with the Choctaws than any other white man is an ardent secessionist believing firmly both in the right & in the final success of the rebel cause—He (Dr. Kingsbury) prays as earnestly & fervently for the success of the rebels as any one among us does for the success of the Union cause. The son of another, Mr. Hodgkin, is a captain in the rebel service—another Mr. Stark actively assisted in organizing a company acted as sec. of secessionist meetings &c. Even Mr. Reid superintendant of Spencer was confident the rebels could never be subdued and thought when the treaty should be made they ought in justice to have Ind. Territory. Again when Fort Smith was evacuated the rebel forces were on the way up the Ark. river to attack it & the garrison evacuated it in the night which[Pg 77] looked to the Indians (if not to the white men) as if the northerners were afraid. The same was true of Fort Washitaw where our forces left in the night and were actually pursued for several days by the Texans. Thus matters stood when Col. Pitchlynn the resident Com. of the Choctaws at Washington returned home. He gave all his influence to have the Choctaws take a neutral position. The chief had called the council to meet June 1st. & Col. P. so far succeeded as to induce him to prepare a message recommending neutrality. Col. P. was promptly reported as an abolitionist and visited & threatened by a Texas Vigilance committee.

The Council met at Doaksville seven miles from Red River & of course from Texas. It was largely attended by white men from Texas our Choctaw neighbors who attended said the place was full of white men.

The Council did not organize until June 4th or 5th (I forget which). In the meanwhile the white men & half bloods had a secession meeting when it leaked out through Col. Cooper that the Chief Hudson had prepared a message recommending neutrality at which Robert M. Jones was so indignant that he made a furious speech in which he declared that “any one who opposed secession ought to be hung” “and any suspicious persons ought to be hung.” Hudson was frightened and when the Council was organized sent in a message recommending that commissioners be appointed to negotiate a treaty with the Confederates and that in the meantime a regiment be organized under Col. Cooper for the Confed. army.

This was finally done but not for a week for the Choctaws were reluctant. They feared that their action would result in the destruction of the nation. Said Joseph P. Folsom, a member of the council & a graduate of Dartmouth College New Hampshire, “We are choosing in what way we shall die.” Judge Wade said to me, “We expect that the Choctaws will be buried. That is what we think will be the end of this.” Judge W. is a member of the Senate (for the Choctaw Council is composed of a Senate & lower house chosen by the people in districts & the constitution is modeled very much after those of the states.) & he has been a chief. Others said to me “If the north was here so we could be protected we would stand up for the north but now[Pg 78] if we do not go in for the south the Texans will come over here and kill us.” Mr. Reid told me a day or two before we left that he had become convinced during a trip for two or three days through the country that the full bloods were strongly for the north. I am sure it was so then & it was the opinion of the missionaries that if we had all taken the position, that we would not leave, some of us had been warned to do so by Texan vigilance committees, we could have raised a thousand men who would have armed in our defence—Our older brethren told us that this would hasten the destruction of the indians as they would be crushed before any help could come.—We thought this would probably be the case and the missionaries who were most strongly union in sentiment left.

One of the number Rev. John Edwards had been hiding for his life from Texan & half blood ruffians for two weeks & we at Spencer had had the honor to be visited by a Texas committee searching for arms.

I continue my narrative from a letter from one of our teachers who was detained when we left by the illness of his wife & who left Spencer Sept. 5th & the Nation Sept. 9th. He says Col. Coopers regiment was filled up with Texans “The half breeds after involving the full bloods in the war have rather drawn back themselves and but few of them have enlisted & gone to the war.” This indicates that the full bloods have at last yielded to the pressure and joined the rebels. The missionaries who remained would generally advise them to do this.

The Choctaw commissioners met Albert Pike rebel commissioner & made a treaty with him, with reference to this he says “The Choctaws rec’d quite a bundle of promises from the rebel government. Their treaty gives their representative a seat in the rebel congress, acknowledges the right of the Choctaws to give testimony in all courts in the C. S., exempts them from the expences of the war, their soldiers are to be paid 20$ a month by the C. S. during the war, the C. S. assume the debts due the Choctaws by the U. S., they have the privilege of coming in as a state into the Confederacy with equal rights if they wish it, or remain as they are, the C. S. to sustain their schools after the war, they guarantee them against all intrusion on their lands by white men, allow them to garrison the forts in their territory[Pg 79] with their own troops if they wish it said troops to be paid by the C. S.”—Here is a list of promises and when I think of these, of the belief of their oldest missionaries in the final success of the rebels, of the fact that all the old Officers of the U. S. government were in the service of the rebels, of the occupation of the forts there by rebels, of the activity of a knot of bitter disunionists led by Capt. Jones, who has long been a very influential man, of the Texas mob law which considered it a crime for a young man to refuse to volunteer, of the fact that there was no way for them to hear the truth as to the designs of the U. S. government concerning them, except through Col. Pitchlyn who was soon silenced & of the falsehoods told them as to the designs of the Government, I do not wonder that they have joined the rebels.

I saw strong men completely unmanned even to floods of tears by the leaving of Dr. Hobbs and the thoughts of what was before them. I heard men say they did not want to fight but expected to be forced to do it.

I trust the government will consider the circumstances of the case & deal gently, considerately with the indians. I do not like to write such things of my brother missionaries but they are I believe facts & though I love some of them very much I still must say that, except Rev. Mr. Byington who was doubtful & Rev. Mr. Balantine a missionary to the Chickasaws who was union, all the ordained missionaries belonging to the Choctaw & Chickasaw Mission of the Presbyterian Board who remain there were victims of the madness which swept over the South, were secessionists—One or two of the three Laymen who remained were union men—Cyrus Kingsbury son of Rev. Dr. K. being one....

The failure of the United States government to give the Indians, in season, the necessary assurance that they would be protected, no matter what might happen, can not be too severely criticized. It indicated a very short-sighted policy and was due either to a tendency to ignore the Indians as people of no importance or to a lack of harmony and coöperation among the departments at Washington. Such an assurance of continued protection[Pg 80] was not even framed until the second week in May and then the Indian country was already threatened by the secessionists. Moreover, it was framed and intended to be given by one department, the Interior, and its fulfilment left to another, the War. It went out from the Indian Office in the form of a circular letter,[114] addressed by Commissioner William P. Dole to the chief executive[115] in each of the five great tribes. It assured the Indians that President Lincoln had no intention of interfering with their domestic institutions or of allowing government agents or employees to interfere and that the War Department had been appealed to to furnish all needed defense according to treaty guaranties. The new southern superintendent, William G. Coffin of Indiana, was made the bearer of the missive; but, unfortunately, quite a little time elapsed[116] before the military situation[117] in the West would allow him to [Pg 81]assume his full duties or to reach his official headquarters,[118] and, in the interval, he was detailed for other[Pg 82] work. The Indians, meanwhile, were left to their own devices and were obliged to look out for their own defense as best they could.

To all appearances neither the legislative action of the Chickasaws and of the Choctaws nor the work of the inter-tribal council was, at the time of occurrence, reported officially to the United States government or, if reported officially, then not pointedly so as to reveal its real bearings upon the case in hand. All the agents within Indian Territory were as usual southern men;[119] but may not have been directly responsible or even cognizant of this particular action of their charges. The records show that practically all of them, Cooper, Garrett, Cowart, Leeper, and Dorn, were absent[120] from their posts, with or without leave, the first part of the[Pg 83] new year and that every one of them became or was already an active secessionist.[121]