The Project Gutenberg EBook of A Selection from the Works of Frederick

Locker, by Frederick Locker

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net

Title: A Selection from the Works of Frederick Locker

Author: Frederick Locker

Illustrator: Richard Doyle

Release Date: January 1, 2012 [EBook #38463]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK WORKS OF FREDERICK LOCKER ***

Produced by Chris Curnow, Matthew Wheaton and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive)

London. Edward Moxon & Co. Dover Street.

MOXON'S MINIATURE POETS.

A

Selection From the Works

OF

FREDERICK LOCKER

WITH ILLUSTRATIONS BY RICHARD DOYLE.

LONDON:

EDWARD MOXON & CO., DOVER STREET.

1865.

PRINTED BY BRADBURY AND EVANS, WHITEFRIARS.

THE ILLUSTRATIONS BY J. E. MILLAIS, R.A., AND RICHARD DOYLE

THE COVER FROM A DESIGN BY JOHN LEIGHTON, F.S.A.

THE SERIES PROJECTED AND SUPERINTENDED BY

Some of these pieces appeared in a volume called "London Lyrics," of

which there have been two editions, the first in 1857, and the second

in 1862; a few of the pieces have been restored to the reading of the

First Edition.

TO C. C. L.

I PAUSE upon the threshold, Charlotte dear,

To write thy name; so may my book acquire

One golden leaf. For Some yet sojourn here

Who come and go in homeliest attire,

Unknown, or only by the few who see

The cross they bear, the good that they have wrought:

Of such art thou, and I have found in thee

The love and truth that He, the Master, taught;

Thou likest thy humble poet, canst thou say

With truth, dear Charlotte?—"And I like his lay."

Rome, May, 1862.

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

[1]

THE JESTERS MORAL

I wish that I could run away

From House, and Court, and Levee:

Where bearded men appear to-day,

Just Eton boys grown heavy.—W. M. Praed.

Is human life a pleasant game

That gives a palm to all?

A fight for fortune, or for fame?

A struggle, and a fall?

Who views the Past, and all he prized,

With tranquil exultation?

And who can say, I've realised

My fondest aspiration?

[2]

Alas, not one! for rest assured

That all are prone to quarrel

With Fate, when worms destroy their gourd,

Or mildew spoils their laurel:

The prize may come to cheer our lot,

But all too late—and granted

'Tis even better—still 'tis not

Exactly what we wanted.

My school-boy time! I wish to praise

That bud of brief existence,

The vision of my youthful days

Now trembles in the distance.

An envious vapour lingers here,

And there I find a chasm;

But much remains, distinct and clear,

To sink enthusiasm.

Such thoughts just now disturb my soul

With reason good—for lately

I took the train to Marley-knoll,

And crossed the fields to Mately.

I found old Wheeler at his gate,

Who used rare sport to show me:

My Mentor once on snares and bait—

But Wheeler did not know me.

[3]

"Goodlord!" at last exclaimed the churl,

"Are you the little chap, sir,

What used to train his hair in curl,

And wore a scarlet cap, sir?"

And then he fell to fill in blanks,

And conjure up old faces;

And talk of well-remembered pranks,

In half forgotten places.

It pleased the man to tell his brief

And somewhat mournful story,

Old Bliss's school had come to grief—

And Bliss had "gone to glory."

His trees were felled, his house was razed—

And what less keenly pained me,

A venerable donkey grazed

Exactly where he caned me.

And where have all my playmates sped,

Whose ranks were once so serried?

Why some are wed, and some are dead,

And some are only buried;

Frank Petre, erst so full of fun,

Is now St. Blaise's prior—

And Travers, the attorney's son,

Is member for the shire.[4]

Dame Fortune, that inconstant jade,

Can smile when least expected,

And those who languish in the shade,

Need never be dejected.

Poor Pat, who once did nothing right,

Has proved a famous writer;

While Mat "shirked prayers" (with all his might!)

And wears, withal, his mitre.

Dull maskers we! Life's festival

Enchants the blithe new-comer;

But seasons change, and where are all

These friendships of our summer?

Wan pilgrims flit athwart our track—

Cold looks attend the meeting—

We only greet them, glancing back,

Or pass without a greeting!

I owe old Bliss some rubs, but pride

Constrains me to postpone 'em,

He taught me something, 'ere he died,

About nil nisi bonum.

I've met with wiser, better men,

But I forgive him wholly;

Perhaps his jokes were sad—but then

He used to storm so drolly.[5]

I still can laugh, is still my boast,

But mirth has sounded gayer;

And which provokes my laughter most—

The preacher, or the player?

Alack, I cannot laugh at what

Once made us laugh so freely,

For Nestroy and Grassot are not—

And where is Mr. Keeley?

O, shall I run away from hence,

And dress and shave like Crusoe?

Or join St. Blaise? No, Common Sense,

Forbid that I should do so.

I'd sooner dress your Little Miss

As Paulet shaves his poodles!

As soon propose for Betsy Bliss—

Or get proposed for Boodle's.

We prate of Life's illusive dyes,

Yet still fond Hope enchants us;

We all believe we near the prize,

Till some fresh dupe supplants us!

A bright reward, forsooth! And though

No mortal has attained it,

I still can hope, for well I know

That Love has so ordained it.

Paris, November, 1864.

[6]

BRAMBLE-RISE.

What changes greet my wistful eyes

In quiet little Bramble-Rise,

Once smallest of its shire?

How altered is each pleasant nook!

The dumpy church used not to look

So dumpy in the spire.

This village is no longer mine;

And though the Inn has changed its sign,

The beer may not be stronger:

The river, dwindled by degrees,

Is now a brook,—the cottages

Are cottages no longer.

The thatch is slate, the plaster bricks,

The trees have cut their ancient sticks,

Or else the sticks are stunted:

I'm sure these thistles once grew figs,

These geese were swans, and once these pigs

More musically grunted.[7]

Where early reapers whistled, shrill

A whistle may be noted still,—

The locomotive's ravings.

New custom newer want begets,—

My bank of early violets

Is now a bank for savings!

That voice I have not heard for long!

So Patty still can sing the song

A merry playmate taught her;

I know the strain, but much suspect

'Tis not the child I recollect,

But Patty,—Patty's daughter;

And has she too outlived the spells

Of breezy hills and silent dells

Where childhood loved to ramble?

Then Life was thornless to our ken,

And, Bramble-Rise, thy hills were then

A rise without a bramble.

Whence comes the change? 'Twere easy told

That some grow wise, and some grow cold,

And all feel time and trouble:

If Life an empty bubble be,

How sad are those who will not see

A rainbow in the bubble!

[8]

And senseless too, for mistress Fate

Is not the gloomy reprobate

That mouldy sages thought her;

My heart leaps up, and I rejoice

As falls upon my ear thy voice,

My frisky little daughter.

Come hither, Pussy, perch on these

Thy most unworthy father's knees,

And tell him all about it:

Are dolls but bran? Can men be base?

When gazing on thy blessed face

I'm quite prepared to doubt it.

O, mayst thou own, my winsome elf,

Some day a pet just like thyself,

Her sanguine thoughts to borrow;

Content to use her brighter eyes,—

Accept her childish ecstacies,—

If need be, share her sorrow!

The wisdom of thy prattle cheers

This heart; and when outworn in years

And homeward I am starting,

My Darling, lead me gently down

To Life's dim strand: the dark waves frown,

But weep not for our parting.

[9]

Though Life is called a doleful jaunt,

In sorrow rife, in sunshine scant,

Though earthly joys, the wisest grant,

Have no enduring basis;

'Tis something in a desert sere,

For her so fresh—for me so drear,

To find in Puss, my daughter dear,

A little cool oasis!

April, 1857.

[10]

THE WIDOW'S MITE.

The Widow had but only one,

A puny and decrepit son;

Yet, day and night,

Though fretful oft, and weak, and small,

A loving child, he was her all—

The Widow's Mite.

The Widow's might,—yes! so sustained,

She battled onward, nor complained

When friends were fewer:

And, cheerful at her daily care,

A little crutch upon the stair

Was music to her.

I saw her then,—and now I see,

Though cheerful and resigned, still she

Has sorrowed much:

She has—He gave it tenderly—

Much faith—and, carefully laid by,

A little crutch.

[11]

ON AN OLD MUFF

Time has a magic wand!

What is this meets my hand,

Moth-eaten, mouldy, and

Covered with fluff?

Faded, and stiff, and scant;

Can it be? no, it can't—

Yes,—I declare 'tis Aunt

Prudence's Muff!

[12]

Years ago—twenty-three!

Old Uncle Barnaby

Gave it to Aunty P.—

Laughing and teasing—

"Pru., of the breezy curls,

Whisper these solemn churls,

What holds a pretty girl's

Hand without squeezing?"

Uncle was then a lad

Gay, but, I grieve to add,

Sinful: if smoking bad

Baccy's a vice:

Glossy was then this mink

Muff, lined with pretty pink

Satin, which maidens think

"Awfully nice!"

I see, in retrospect,

Aunt, in her best bedecked,

Gliding, with mien erect,

Gravely to Meeting:

Psalm-book, and kerchief new,

Peeped from the muff of Pru.—

Young men—and pious too—

Giving her greeting.

[13]

Pure was the life she led

Then—from this Muff, 'tis said,

Tracts she distributed:—

Scapegraces many,

Seeing the grace they lacked,

Followed her—one, in fact,

Asked for—and got his tract

Oftener than any.

Love has a potent spell!

Soon this bold Ne'er-do-well,

Aunt's sweet susceptible

Heart undermining,

Slipped, so the scandal runs,

Notes in the pretty nun's

Muff—triple-cornered ones—

Pink as its lining!

Worse even, soon the jade

Fled (to oblige her blade!)

Whilst her friends thought that they'd

Locked her up tightly:

After such shocking games

Aunt is of wedded dames

Gayest—and now her name's

Mrs. Golightly.

[14]

In female conduct flaw

Sadder I never saw,

Still I've faith in the law

Of compensation.

Once Uncle went astray—

Smoked, joked, and swore away—

Sworn by, he's now, by a

Large congregation!

Changed is the Child of Sin,

Now he's (he once was thin)

Grave, with a double chin,—

Blest be his fat form!

Changed is the garb he wore,—

Preacher was never more

Prized than is Uncle for

Pulpit or platform.

If all's as best befits

Mortals of slender wits,

Then beg this Muff, and its

Fair Owner pardon:

All's for the best,—indeed

Such is my simple creed—

Still I must go and weed

Hard in my garden.

[15]

A HUMAN SKULL.

A human skull! I bought it passing cheap,—

It might be dearer to its first employer;

I thought mortality did well to keep

Some mute memento of the Old Destroyer.

Time was, some may have prized its blooming skin,

Here lips were wooed perchance in transport tender;—

Some may have chucked what was a dimpled chin,

And never had my doubt about its gender!

Did she live yesterday or ages back?

What colour were the eyes when bright and waking?

And were your ringlets fair, or brown, or black,

Poor little head! that long has done with aching?

It may have held (to shoot some random shots)

Thy brains, Eliza Fry,—or Baron Byron's,

The wits of Nelly Gwynn, or Doctor Watts,—

Two quoted bards! two philanthropic sirens!

[16]

But this I surely knew before I closed

The bargain on the morning that I bought it;

It was not half so bad as some supposed,

Nor quite as good as many may have thought it.

Who love, can need no special type of death;

He bares his awful face too soon, too often;

"Immortelles" bloom in Beauty's bridal wreath,

And does not yon green elm contain a coffin?

O, cara mine, what lines of care are these?

The heart still lingers with the golden hours,

An Autumn tint is on the chestnut trees,

And where is all that boasted wealth of flowers?

If life no more can yield us what it gave,

It still is linked with much that calls for praises;

A very worthless rogue may dig the grave,

But hands unseen will dress the turf with daisies.

[17]

TO MY GRANDMOTHER.

(SUGGESTED BY A PICTURE BY MR. ROMNEY.)

This relative of mine

Was she seventy and nine

When she died?

By the canvas may be seen

How she looked at seventeen,—

As a bride.

Beneath a summer tree

As she sits, her reverie

Has a charm;

Her ringlets are in taste,—

What an arm! and what a waist

For an arm!

In bridal coronet,

Lace, ribbons, and coquette

Falbala;

Were Romney's limning true,

What a lucky dog were you,

Grandpapa!

[18]

Her lips are sweet as love,—

They are parting! Do they move?

Are they dumb?—

Her eyes are blue, and beam

Beseechingly, and seem

To say, "Come."

What funny fancy slips

From atween these cherry lips?

Whisper me,

Sweet deity, in paint,

What canon says I mayn't

Marry thee?

That good-for-nothing Time

Has a confidence sublime!

When I first

Saw this lady, in my youth,

Her winters had, forsooth,

Done their worst.

Her locks (as white as snow)

Once shamed the swarthy crow.

By-and-by,

That fowl's avenging sprite,

Set his cloven foot for spite

In her eye.

[19]

Her rounded form was lean,

And her silk was bombazine:—

Well I wot,

With her needles would she sit,

And for hours would she knit,—

Would she not?

Ah, perishable clay!

Her charms had dropt away

One by one.

But if she heaved a sigh

With a burthen, it was, "Thy

Will be done."

In travail, as in tears,

With the fardel of her years

Overprest,—

In mercy was she borne

Where the weary ones and worn

Are at rest.

I'm fain to meet you there,—

If as witching as you were,

Grandmamma!

This nether world agrees

That the better it must please

Grandpapa.

[20]

O TEMPORA MUTANTUR!

Yes, here, once more, a traveller,

I find the Angel Inn,

Where landlord, maids, and serving-men

Receive me with a grin:

They surely can't remember me,

My hair is grey and scanter;

I'm changed, so changed since I was here—

"O tempora mutantur!"

The Angel's not much altered since

That sunny month of June,

Which brought me here with Pamela

To spend our honeymoon!

I recollect it down to e'en

The shape of this decanter,—

We've since been both much put about—

"O tempora mutantur!"

[21]

Ay, there's the clock, and looking-glass

Reflecting me again;

She vowed her Love was very fair—

I see I'm very plain.

And there's that daub of Prince Leeboo:

'Twas Pamela's fond banter

To fancy it resembled me—

"O tempora mutantur!"

The curtains have been dyed; but there,

Unbroken, is the same,

The very same cracked pane of glass

On which I scratched her name.

Yes, there's her tiny flourish still,

It used to so enchant her

To link two happy names in one—

"O tempora mutantur!"

* * * * *

What brought this wanderer here, and why

Was Pamela away?

It might be she had found her grave,

Or he had found her gay.

The fairest fade; the best of men

May meet with a supplanter;—

I wish the times would change their cry

Of "tempora mutantur."

[22]

REPLY TO A LETTER ENCLOSING A LOCK OF HAIR.

"My darling wants to see you soon,"—

I bless the little maid, and thank her;

To do her bidding, night and noon

I draw on Hope—Love's kindest banker!

Old MSS.

If you were false, and if I'm free,

I still would be the slave of yore,

Then joined our years were thirty-three,

And now,—yes now, I'm thirty-four!

And though you were not learnèd—well,

I was not anxious you should grow so,—

I trembled once beneath her spell

Whose spelling was extremely so-so!

Bright season! why will Memory

Still haunt the path our rambles took;

The sparrow's nest that made you cry,—

The lilies captured in the brook.

I lifted you from side to side,

You seemed as light as that poor sparrow;

I know who wished it twice as wide,

I think you thought it rather narrow.

[23]

Time was,—indeed, a little while!

My pony did your heart compel;

But once, beside the meadow-stile,

I thought you loved me just as well;

I kissed your cheek; in sweet surprise

Your troubled gaze said plainly, "Should he?"

But doubt soon fled those daisy eyes,—

"He could not wish to vex me, could he?"

As year succeeds to year, the more

Imperfect life's fruition seems,

Our dreams, as baseless as of yore,

Are not the same enchanting dreams.

The girls I love now vote me slow—

How dull the boys who once seemed witty!

Perhaps I'm getting old—I know

I'm still romantic—more's the pity!

Ah, vain regret! to few, perchance,

Unknown—and profitless to all:

The wisely-gay, as years advance,

Are gaily-wise. Whate'er befall

We'll laugh—at folly, whether seen

Beneath a chimney or a steeple,

At yours, at mine—our own, I mean,

As well as that of other people.

[24]

They cannot be complete in aught,

Who are not humorously prone,

A man without a merry thought

Can hardly have a funny-bone!

To say I hate your gloomy men

Might be esteemed a strong assertion,

If I've blue devils, now and then,

I make them dance for my diversion.

And here's your letter débonnaire!

"My friend, my dear old friend of yore,"

And is this curl your daughter's hair?

I've seen the Titian tint before.

Are we that pair who used to pass

Long days beneath the chesnuts shady?

You then were such a pretty lass!—

I'm told you're now as fair a lady.

I've laughed to hide the tear I shed,

As when the Jester's bosom swells,

And mournfully he shakes his head,

We hear the jingle of his bells.

A jesting vein your poet vexed,

And this poor rhyme, the Fates determine,

Without a parson, or a text,

Has proved a somewhat prosy sermon.

[25]

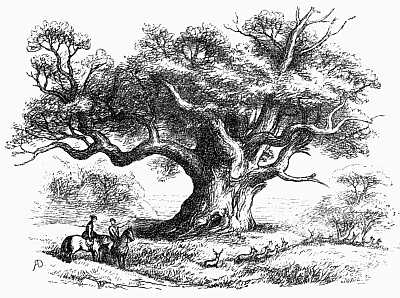

THE OLD OAK-TREE AT HATFIELD BROADOAK.

A mighty growth! The county side

Lamented when the Giant died,

For England loves her trees:

What misty legends round him cling!

How lavishly he once did fling

His acorns to the breeze!

[26]

To strike a thousand roots in fame,

To give the district half its name,

The fiat could not hinder;

Last spring he put forth one green bough,—

The red leaves hang there still,—but now

His very props are tinder.

Elate, the thunderbolt he braved,

Long centuries his branches waved

A welcome to the blast;

An oak of broadest girth he grew,

And woodman never dared to do

What Time has done at last.

The monarch wore a leafy crown,

And wolves, ere wolves were hunted down,

Found shelter at his foot;

Unnumbered squirrels gambolled free,

Glad music filled the gallant tree

From stem to topmost shoot.

And it were hard to fix the tale

Of when he first peered forth a frail

Petitioner for dew;

No Saxon spade disturbed his root,

The rabbit spared the tender shoot,

And valiantly he grew,

[27]

And showed some inches from the ground

When Saint Augustine came and found

Us very proper Vandals:

When nymphs owned bluer eyes than hose,

When England measured men by blows,

And measured time by candles.

Worn pilgrims blessed his grateful shade

Ere Richard led the first crusade,

And maidens led the dance

Where, boy and man, in summer-time,

Sweet Chaucer pondered o'er his rhyme;

And Robin Hood, perchance,

Stole hither to maid Marian,

(And if they did not come, one can

At any rate suppose it);

They met beneath the mistletoe,—

We did the same, and ought to know

The reason why they chose it.

And this was called the traitor's branch,—

Stern Warwick hung six yeomen stanch

Along its mighty fork;

Uncivil wars for them! The fair

Red rose and white still bloom,—but where

Are Lancaster and York?

[28]

Right mournfully his leaves he shed

To shroud the graves of England's dead,

By English falchion slain;

And cheerfully, for England's sake,

He sent his kin to sea with Drake,

When Tudor humbled Spain.

A time-worn tree, he could not bring

His heart to screen the merry king,

Or countenance his scandals;—

Then men were measured by their wit,—

And then the mimic statesmen lit

At either end their candles!

While Blake was busy with the Dutch

They gave his poor old arms a crutch:

And thrice four maids and men ate

A meal within his rugged bark,

When Coventry bewitched the park,

And Chatham swayed the senate.

His few remaining boughs were green,

And dappled sunbeams danced between,

Upon the dappled deer,

When, clad in black, a pair were met

To read the Waterloo Gazette,—

They mourned their darling here.

[29]

They joined their boy. The tree at last

Lies prone—discoursing of the past,

Some fancy-dreams awaking;

Resigned, though headlong changes come,—

Though nations arm to tuck of drum,

And dynasties are quaking.

Romantic spot! By honest pride

Of eld tradition sanctified;

My pensive vigil keeping,

I feel thy beauty like a spell,

And thoughts, and tender thoughts, upwell,

That fill my heart to weeping.

* * * * *

The Squire affirms, with gravest look,

His oak goes up to Domesday Book!—

And some say even higher!

We rode last week to see the ruin,

We love the fair domain it grew in,

And well we love the Squire.

A nature loyally controlled,

And fashioned in that righteous mould

Of English gentleman;—

My child may some day read these rhymes,—

She loved her "godpapa" betimes,—

The little Christian!

[30]

I love the Past, its ripe pleasànce,

Its lusty thought, and dim romance,

And heart-compelling ditties;

But more, these ties, in mercy sent,

With faith and true affection blent,

And, wanting them, I were content

To murmur, "Nunc dimittis."

Hallingbury, April, 1859.

[31]

AN INVITATION TO ROME, AND THE REPLY.

THE INVITATION.

O, come to Rome, it is a pleasant place,

Your London sun is here seen shining brightly:

The Briton too puts on a cheery face,

And Mrs. Bull is suave and even sprightly.

The Romans are a kind and cordial race,

The women charming, if one takes them rightly;

I see them at their doors, as day is closing,

More proud than duchesses—and more imposing.

A "far niente" life promotes the graces;—

They pass from dreamy bliss to wakeful glee,

And in their bearing, and their speech, one traces

A breadth of grace and depth of courtesy

That are not found in more inclement places;

Their clime and tongue seem much in harmony;

The Cockney met in Middlesex, or Surrey,

Is often cold—and always in a hurry.

[32]

Though "far niente" is their passion, they

Seem here most eloquent in things most slight;

No matter what it is they have to say,

The manner always sets the matter right.

And when they've plagued or pleased you all the day

They sweetly wish you "a most happy night."

Then, if they fib, and if their stories tease you,

'Tis always something that they've wished to please you.

O, come to Rome, nor be content to read

Alone of stately palaces and streets

Whose fountains ever run with joyous speed,

And never-ceasing murmur. Here one meets

Great Memnon's monoliths—or, gay with weed,

Rich capitals, as corner stones, or seats—

The sites of vanished temples, where now moulder

Old ruins, hiding ruin even older.

Ay, come, and see the pictures, statues, churches,

Although the last are commonplace, or florid.

Some say 'tis here that superstition perches,—

Myself I'm glad the marbles have been quarried.

The sombre streets are worthy your researches:

The ways are foul, the lava pavement's horrid,

But pleasant sights, which squeamishness disparages,

Are missed by all who roll about in carriages.

[33]

About one fane I deprecate all sneering,

For during Christmas-time I went there daily,

Amused, or edified—or both—by hearing

The little preachers of the Ara Cœli.

Conceive a four-year-old bambina rearing

Her small form on a rostrum, tricked out gaily,

And lisping, what for doctrine may be frightful,

With action quite dramatic and delightful.

O come! We'll charter such a pair of nags!

The country's better seen when one is riding:

We'll roam where yellow Tiber speeds or lags

At will. The aqueducts are yet bestriding

With giant march (now whole, now broken crags

With flowers plumed) the swelling and subsiding

Campagna, girt by purple hills, afar—

That melt in light beneath the evening star.

A drive to Palestrina will be pleasant—

The wild fig grows where erst her turrets stood;

There oft, in goat-skins clad, a sun-burnt peasant

Like Pan comes frisking from his ilex wood,

And seems to wake the past time in the present.

Fair contadina, mark his mirthful mood,

No antique satyr he. The nimble fellow

Can join with jollity your Salterello.

[34]

Old sylvan peace and liberty! The breath

Of life to unsophisticated man.

Here Mirth may pipe, here Love may weave his wreath,

"Per dar' al mio bene." When you can,

Come share their leafy solitudes. Grim Death

And Time are grudging of Life's little span:

Wan Time speeds swiftly o'er the waving corn,

Death grins from yonder cynical old thorn.

I dare not speak of Michael Angelo—

Such theme were all too splendid for my pen.

And if I breathe the name of Sanzio

(The brightest of Italian gentlemen),

It is that love casts out my fear—and so

I claim with him a kindredship. Ah! when

We love, the name is on our hearts engraven,

As is thy name, my own dear Bard of Avon!

Nor is the Colosseum theme of mine,

'Twas built for poet of a larger daring;

The world goes there with torches—I decline

Thus to affront the moonbeams with their flaring.

Some time in May our forces we'll combine

(Just you and I) and try a midnight airing,

And then I'll quote this rhyme to you—and then

You'll muse upon the vanity of men.

[35]

O come—I send a leaf of tender fern,

'Twas plucked where Beauty lingers round decay:

The ashes buried in a sculptured urn

Are not more dead than Rome—so dead to-day!

That better time, for which the patriots yearn,

Enchants the gaze, again to fade away.

They wait and pine for what is long denied,

And thus I wait till thou art by my side.

Thou'rt far away! Yet, while I write, I still

Seem gently, Sweet, to press thy hand in mine;

I cannot bring myself to drop the quill,

I cannot yet thy little hand resign!

The plain is fading into darkness chill,

The Sabine peaks are flushed with light divine,

I watch alone, my fond thought wings to thee,

O come to Rome—O come, O come to me!

[36]

THE REPLY.

Dear Exile, I was pleased to get

Your rhymes, I laid them up in cotton;

You know that you are all to "Pet,"

I feared that I was quite forgotten:

Mama, who scolds me when I mope,

Insists—and she is wise as gentle—

That I am still in love—I hope

That you are rather sentimental.

Perhaps you think a child should not

Be gay unless her slave is with her;

Of course you love old Rome, and, what

Is more, would like to coax me thither:

What! quit this dear delightful maze

Of calls and balls, to be intensely

Discomfited in fifty ways—

I like your confidence immensely!

Some girls who love to ride and race,

And live for dancing—like the Bruens,

Confess that Rome's a charming place,

In spite of all the stupid ruins:[37]

I think it might be sweet to pitch

One's tent beside those banks of Tiber,

And all that sort of thing—of which

Dear Hawthorne's "quite" the best describer.

To see stone pines, and marble gods,

In garden alleys—red with roses—

The Perch where Pio Nono nods;

The Church where Raphael reposes.

Make pleasant giros—when we may;

Jump stagionate—where they're easy;

And play croquet—the Bruens say

There's turf behind the Ludovisi.

I'll bring my books, though Mrs. Mee

Says packing books is such a worry;

I'll bring my "Golden Treasury,"

Manzoni—and, of course, a "Murray;"

A Tupper, whom you men despise;

A Dante—Auntie owns a quarto—

I'll try and buy a smaller size,

And read him on the muro torto.

But can I go? La Madre thinks

It would be such an undertaking:—

I wish we could consult a sphynx;—

The thought alone has set her quaking.[38]

Papa—we do not mind Papa—

Has got some "notice" of some "motion,"

And could not stay; but, why not,—Ah,

I've not the very slightest notion.

The Browns have come to stay a week,

They've brought the boys, I haven't thanked 'em,

For Baby Grand, and Baby Pic,

Are playing cricket in my sanctum:

Your Rover too affects my den,

And when I pat the dear old whelp, it ...

It makes me think of you, and then ...

And then I cry—I cannot help it.

Ah, yes—before you left me, ere

Our separation was impending,

These eyes had seldom shed a tear—

For mine was joy that knew no ending;

Yes, soon there came a change, too soon:

The first faint cloud that rose to grieve me

Was knowledge I possessed the boon,

And then a fear such bliss might leave me.

This strain is sad: yet, understand,

Your words have made my spirit better:

And when I first took pen in hand,

I meant to write a cheery letter;[39]

But skies were dull,—Rome sounded hot,

I fancied I could live without it:

I thought I'd go—I thought I'd not,

And then I thought I'd think about it.

The sun now glances o'er the Park,

If tears are on my cheek, they glitter;

I think I've kissed your rhymes, for—hark!

My "bulley" gives a saucy twitter.

Your blessed words extinguish doubt,

A sudden breeze is gaily blowing,

And, hark! The minster bells ring out—

"She ought to go! Of course she's going."

[40]

OLD LETTERS.

Old letters! wipe away the tear

For vows and hopes so vainly worded?

A pilgrim finds his journal here

Since first his youthful loins were girded.

Yes, here are wails from Clapham Grove,

How could philosophy expect us[41]

To live with Dr. Wise, and love

Rice pudding and the Greek Delectus?

Explain why childhood's path is sown

With moral and scholastic tin-tacks;

Ere sin original was known,

Did Adam groan beneath the syntax?

How strange to parley with the dead!

Keep ye your green, wan leaves? How many

From Friendship's tree untimely shed!

And here is one as sad as any;

A ghastly bill! "I disapprove,"

And yet She help'd me to defray it—

What tokens of a Mother's love!

O, bitter thought! I can't repay it.

And here's the offer that I wrote

In '33 to Lucy Diver;

And here John Wylie's begging note,—

He never paid me back a stiver.

And here my feud with Major Spike,

Our bet about the French Invasion;[42]

I must confess I acted like

A donkey upon that occasion.

Here's news from Paternoster Row!

How mad I was when first I learnt it:

They would not take my Book, and now

I'd give a trifle to have burnt it.

And here a pile of notes, at last,

With "love," and "dove," and "sever," "never,"—

Though hope, though passion may be past,

Their perfume is as sweet as ever.

A human heart should beat for two,

Despite the scoffs of single scorners;

And all the hearths I ever knew

Had got a pair of chimney corners.

See here a double violet—

Two locks of hair—a deal of scandal;

I'll burn what only brings regret—

Go, Betty, fetch a lighted candle.

[43]

MY NEIGHBOUR ROSE.

Though slender walls our hearths divide,

No word has passed from either side,

Your days, red-lettered all, must glide

Unvexed by labour:

I've seen you weep, and could have wept;

I've heard you sing, and may have slept;

Sometimes I hear your chimneys swept,

My charming neighbour!

Your pets are mine. Pray what may ail

The pup, once eloquent of tail?

I wonder why your nightingale

Is mute at sunset!

Your puss, demure and pensive, seems

Too fat to mouse. She much esteems

Yon sunny wall—and sleeps and dreams

Of mice she once ate.

[44]

Our tastes agree. I doat upon

Frail jars, turquoise and celadon,

The "Wedding March" of Mendelssohn,

And Penseroso.

When sorely tempted to purloin

Your pietà of Marc Antoine,

Fair Virtue doth fair play enjoin,

Fair Virtuoso!

At times an Ariel, cruel-kind,

Will kiss my lips, and stir your blind,

And whisper low, "She hides behind;

Thou art not lonely."

The tricksy sprite did erst assist

At hushed Verona's moonlight tryst;

Sweet Capulet! thou wert not kissed

By light winds only.

I miss the simple days of yore,

When two long braids of hair you wore,

And chat botté was wondered o'er,

In corner cosy.

But gaze not back for tales like those:

'Tis all in order, I suppose,

The Bud is now a blooming Rose,—

A rosy posy!

[45]

Indeed, farewell to bygone years;

How wonderful the change appears—

For curates now and cavaliers

In turn perplex you:

The last are birds of feather gay,

Who swear the first are birds of prey;

I'd scare them all had I my way,

But that might vex you.

At times I've envied, it is true,

That joyous hero, twenty-two,

Who sent bouquets and billets-doux,

And wore a sabre.

The rogue! how tenderly he wound

His arm round one who never frowned;

He loves you well. Now, is he bound

To love my neighbour?

The bells are ringing. As is meet,

White favours fascinate the street,

Sweet faces greet me, rueful-sweet

'Twixt tears and laughter:

They crowd the door to see her go—

The bliss of one brings many woe—

Oh! kiss the bride, and I will throw

The old shoe after.

[46]

What change in one short afternoon,—

My Charming Neighbour gone,—so soon!

Is yon pale orb her honey-moon

Slow rising hither?

O lady, wan and marvellous,

How often have we communed thus;

Sweet memories shall dwell with us,

And joy go with her!

[47]

PICCADILLY.

Piccadilly!—shops, palaces, bustle, and breeze,

The whirring of wheels, and the murmur of trees,

By daylight, or nightlight,—or noisy, or stilly,—

Whatever my mood is—I love Piccadilly.

Wet nights, when the gas on the pavement is streaming,

And young Love is watching, and old Love is dreaming,

And Beauty is whirled off to conquest, where shrilly

Cremona makes nimble thy toes, Piccadilly!

[48]

Bright days, when we leisurely pace to and fro,

And meet all the people we do or don't know,—

Here is jolly old Brown, and his fair daughter Lillie;

—No wonder, young pilgrim, you like Piccadilly!

See yonder pair riding, how fondly they saunter!

She smiles on her poet, whose heart's in a canter:

Some envy her spouse, and some covet her filly,

He envies them both,—he's an ass, Piccadilly!

Now were I that gay bride, with a slave at my feet,

I would choose me a house in my favourite street;

Yes or no—I would carry my point, willy, nilly,

If "no,"—pick a quarrel, if "yes,"—Piccadilly!

From Primrose balcony, long ages ago,

"Old Q" sat at gaze,—who now passes below?

A frolicsome Statesman, the Man of the Day,

A laughing philosopher, gallant and gay;

No hero of story more manfully trod,

Full of years, full of fame, and the world at his nod,

Heu, anni fugaces! The wise and the silly,—

Old P or old Q,—we must quit Piccadilly.

Life is chequered,—a patchwork of smiles and of frowns;

We value its ups, let us muse on its downs;

[49]

There's a side that is bright, it will then turn us t'other,—

One turn, if a good one, deserves such another.

These downs are delightful, these ups are not hilly,—

Let us turn one more turn ere we quit Piccadilly.

[50]

THE PILGRIMS OF PALL MALL.

My little friend, so small and neat,

Whom years ago I used to meet

In Pall Mall daily;

How cheerily you tripped away

To work, it might have been to play,

You tripped so gaily.

And Time trips too. This moral means

You then were midway in the teens

That I was crowning;

We never spoke, but when I smiled

At morn or eve, I know, dear Child,

You were not frowning.

Each morning when we met, I think

Some sentiment did us two link—

Nor joy, nor sorrow;

And then at eve, experience-taught,

Our hearts returned upon the thought,—

We meet to-morrow!

[51]

And you were poor; and how?—and why?

How kind to come! it was for my

Especial grace meant!

Had you a chamber near the stars,

A bird,—some treasured plants in jars,

About your casement?

I often wander up and down,

When morning bathes the silent town

In golden glory:

Perchance, unwittingly, I've heard

Your thrilling-toned canary-bird

From some third story.

I've seen great changes since we met;—

A patient little seamstress yet,

With small means striving,

Have you a Lilliputian spouse?

And do you dwell in some doll's house?

—Is baby thriving?

Can bloom like thine—my heart grows chill—

Have sought that bourne unwelcome still

To bosom smarting?

The most forlorn—what worms we are!—

Would wish to finish this cigar

Before departing.

[52]

Sometimes I to Pall Mall repair,

And see the damsels passing there;

But if I try to

Obtain one glance, they look discreet,

As though they'd some one else to meet;—

As have not I too?

Yet still I often think upon

Our many meetings, come and gone!

July—December!

Now let us make a tryst, and when,

Dear little soul, we meet again,—

The mansion is preparing—then

Thy Friend remember!

[53]

GERALDINE.

This simple child has claims

On your sentiment—her name's

Geraldine.

Be tender—but beware,

For she's frolicsome as fair,

And fifteen.

She has gifts that have not cloyed,

For these gifts she has employed,

And improved:

She has bliss which lives and leans

Upon loving—and that means

She is loved.

She has grace. A grace refined

By sweet harmony of mind:

And the Art,

And the blessed Nature, too,

Of a tender, and a true

Little heart.

[54]

And yet I must not vault

Over any little fault

That she owns:

Or others might rebel,

And might enviously swell

In their zones.

She is tricksy as the fays,

Or her pussy when it plays

With a string:

She's a goose about her cat,

And her ribbons—and all that

Sort of thing.

These foibles are a blot,

Still she never can do what

Is not nice,

Such as quarrel, and give slaps—

As I've known her get, perhaps,

Once or twice.

The spells that move her soul

Are subtle—sad or droll—

She can show

That virtuoso whim

Which consecrates our dim

Long-ago.

[55]

A love that is not sham

For Stothard, Blake, and Lamb;

And I've known

Cordelia's sad eyes

Cause angel-tears to rise

In her own.

Her gentle spirit yearns

When she reads of Robin Burns—

Luckless Bard!

Had she blossomed in thy time,

How rare had been the rhyme

—And reward!

Thrice happy then is he

Who, planting such a Tree,

Sees it bloom

To shelter him—indeed

We have sorrow as we speed

To our doom!

I am happy having grown

Such a Sapling of my own;

And I crave

No garland for my brows,

But peace beneath its boughs

Till the grave.

[56]

O DOMINE DEUS

"O DOMINE DEUS,

SPERAVI IN TE,

O CARE MI JESU,

NUNC LIBERA ME."

Her quiet resting-place is far away,

None dwelling there can tell you her sad story:

The stones are mute. The stones could only say,

"A humble spirit passed away to glory."

She loved the murmur of this mighty town,

The lark rejoiced her from its lattice prison;

A streamlet soothes her now,—the bird has flown,—

Some dust is waiting there—a soul has risen.

No city smoke to stain the heather bells,—

Sigh, gentle winds, around my lone love sleeping,—

She bore her burthen here, but now she dwells

Where scorner never came, and none are weeping.

[57]

O cough! O cruel cough! O gasping breath!

These arms were round my darling at the latest:

All scenes of death are woe—but painful death

In those we dearly love is surely greatest!

I could not die. He willed it otherwise;

My lot is here, and sorrow, wearing older,

Weighs down the heart, but does not fill the eyes,

And even friends may think that I am colder.

I might have been more kind, more tender; now

Repining wrings my bosom. I am grateful

No eye can see this mark upon my brow,

Yet even gay companionship is hateful.

But when at times I steal away from these,

And find her grave, and pray to be forgiven,

And when I watch beside her on my knees,

I think I am a little nearer heaven.

[58]

THE HOUSEMAID.

"Bright volumes of vapour through Lothbury glide."

Alone she sits, with air resigned

She watches by the window-blind:

Poor girl! No doubt

The pilgrims here despise thy lot:

Thou canst not stir—because 'tis not

Thy Sunday out.

To play a game of hide and seek

With dust and cobwebs all the week,

Small pleasure yields:

O dear, how nice it is to drop

One's scrubbing-brush, one's pail and mop—

And scour the fields!

Poor Bodies some such Sundays know;

They seldom come. How soon they go!

But Souls can roam.

And, lapt in visions airy-sweet,

She sees in this too doleful street

Her own loved Home!

[59]

The road is now no road. She pranks

A brawling stream with thymy banks;

In Fancy's realm

This post sustains no lamp—aloof

It spreads above her parents' roof

A gracious elm.

How often has she valued there

A father's aid—a mother's care:—

She now has neither:

And yet—such work in dreams is done,

She still may sit and smile with one

More dear than either.

The poor can love through woe and pain,

Although their homely speech is fain

To halt in fetters:

They feel as much, and do far more

Than those, at times of meaner ore,

Miscalled their Betters.

Sometimes, on summer afternoons

Of sundry sunny Mays and Junes—

Meet Sunday weather,

I pass her window by design,

And wish her Sunday out and mine

Might fall together.

[60]

For sweet it were my lot to dower

With one brief joy, one white-robed flower;

And prude, or preacher,

Could hardly deem it much amiss

To lay one on the path of this

Forlorn young creature.

Yet if her thought on wooing runs—

And if her swain and she are ones

Who fancy strolling,

She'd like my nonsense less than his,

And so it's better as it is—

And that's consoling.

Her dwelling is unknown to fame—

Perchance she's fair—perchance her name

Is Car, or Kitty;

She may be Jane—she might be plain—

For need the object of one's strain

Be always pretty?

[61]

THE OLD GOVERNMENT CLERK.

We knew an old Scribe, it was "once on a time,"—

An era to set sober datists despairing;—

Then let them despair! Darby sat in a chair

Near the Cross that gave name to the village of Charing.

Though silent and lean, Darby was not malign,—

What hair he had left was more silver than sable;—

He had also contracted a curve in his spine

From bending too constantly over a table.

His pay and expenditure, quite in accord,

Were both on the strictest economy founded;

His masters were known as the Sealing-wax Board,

Who ruled where red tape and snug places abounded.

In his heart he looked down on this dignified knot,—

For why, the forefather of one of these senators,

A rascal concerned in the Gunpowder Plot,

Had been barber-surgeon to Darby's progenitors.

[62]

Poor fool! Life is all a vagary of Luck,—

Still, for thirty long years of genteel destitution

He'd been writing State Papers, which means he had stuck

Some heads and some tails to much circumlocution.

This sounds rather weary and dreary; but, no!

Though strictly inglorious, his days were quiescent,

His red-tape was tied in a true-lover's bow

Each night when returning to Rosemary Crescent.

There Joan meets him smiling, the young ones are there,

His coming is bliss to the half-dozen wee things;

Of his advent the dog and the cat are aware,

And Phyllis, neat-handed, is laying the tea-things.

East wind! sob eerily! sing, kettle! cheerily!

Baby's abed,—but its father will rock it;

Little ones boast your permission to toast

The cake that good fellow brought home in his pocket.

This greeting the silent old Clerk understands,—

His friends he can love, had he foes, he could mock them;[63]

So met, so surrounded, his bosom expands,—

Some tongues have more need of such scenes to unlock them.

And Darby, at least, is resigned to his lot,

And Joan, rather proud of the sphere he's adorning,

Has well-nigh forgotten that Gunpowder Plot,

And he won't recall it till ten the next morning.

A kindly good man, quite a stranger to fame,

His heart still is green, though his head shows a hoar lock;

Perhaps his particular star is to blame,—

It may be, he never took time by the forelock.

A day must arrive when, in pitiful case,

He will drop from his Branch, like a fruit more than mellow;

Is he yet to be found in his usual place?

Or is he already forgotten, poor fellow?

If still at his duty he soon will arrive,—

He passes this turning because it is shorter,—

If not within sight as the clock's striking five,

We shall see him before it is chiming the quarter.

[64]

A WISH.

To the south of the church, and beneath yonder yew,

A pair of child-lovers I've seen,

More than once were they there, and the years of the two,

When added, might number thirteen.

They sat on the grave that has never a stone

The name of the dead to determine,[65]

It was Life paying Death a brief visit—alone

A notable text for a sermon.

They tenderly prattled; what was it they said?

The turf on that hillock was new;

Dear Little Ones, did ye know aught of the Dead,

Or could he be heedful of you?

I wish to believe, and believe it I must,

Her father beneath them was laid:

I wish to believe,—I will take it on trust,

That father knew all that they said.

My own, you are five, very nearly the age

Of that poor little fatherless child:

And some day a true-love your heart will engage,

When on earth I my last may have smiled.

Then visit my grave, like a good little lass,

Where'er it may happen to be,

And if any daisies should peer through the grass,

Be sure they are kisses from me.

And place not a stone to distinguish my name,

For strangers to see and discuss:

[66]But come with your lover, as these lovers came,

And talk to him sweetly of us.

And while you are smiling, your father will smile

Such a dear little daughter to have,

But mind,—O yes, mind you are happy the while—

I wish you to visit my Grave.

[67]

THE JESTER'S PLEA.

These verses were published in 1862, in a volume of Poems by

several hands, entitled "An Offering to Lancashire."

The World! Was jester ever in

A viler than the present?

Yet if it ugly be—as sin,

It almost is—as pleasant!

It is a merry world (pro tem.)

And some are gay, and therefore

It pleases them—but some condemn

The fun they do not care for.

It is an ugly world. Offend

Good people—how they wrangle!

The manners that they never mend!

The characters they mangle!

They eat, and drink, and scheme, and plod,

And go to church on Sunday—

And many are afraid of God—

And more of Mrs. Grundy.

[68]

The time for Pen and Sword was when

"My ladye fayre," for pity

Could tend her wounded knight, and then

Grow tender at his ditty!

Some ladies now make pretty songs,—

And some make pretty nurses:—

Some men are good for righting wrongs,—

And some for writing verses.

I wish We better understood

The tax that poets levy!—

I know the Muse is very good—

I think she's rather heavy:

She now compounds for winning ways

By morals of the sternest—

Methinks the lays of now-a-days

Are painfully in earnest.

When Wisdom halts, I humbly try

To make the most of Folly:

If Pallas be unwilling, I

Prefer to flirt with Polly,—

To quit the goddess for the maid

Seems low in lofty musers—

But Pallas is a haughty jade—

And beggars can't be choosers.

[69]

I do not wish to see the slaves

Of party, stirring passion,

Or psalms quite superseding staves,

Or piety "the fashion."

I bless the Hearts where pity glows,

Who, here together banded,

Are holding out a hand to those

That wait so empty-handed!

A righteous Work!—My Masters, may

A Jester by confession,

Scarce noticed join, half sad, half gay,

The close of your procession?

The motley here seems out of place

With graver robes to mingle,

But if one tear bedews his face,

Forgive the bells their jingle.

[70]

THE OLD CRADLE.

And this was your Cradle? why, surely, my Jenny,

Such slender dimensions go somewhat to show

You were a delightfully small Pic-a-ninny

Some nineteen or twenty short summers ago.

Your baby-days flowed in a much-troubled channel;

I see you as then in your impotent strife,

A tight little bundle of wailing and flannel,

Perplexed with that newly-found fardel called Life.[71]

To hint at an infantine frailty is scandal;

Let bygones be bygones—and somebody knows

It was bliss such a Baby to dance and to dandle,

Your cheeks were so velvet—so rosy your toes.

Ay, here is your Cradle, and Hope, a bright spirit,

With Love now is watching beside it, I know.

They guard the small nest you yourself did inherit

Some nineteen or twenty short summers ago.

It is Hope gilds the future,—Love welcomes it smiling;

Thus wags this old world, therefore stay not to ask—

"My future bids fair, is my future beguiling?"

If masked, still it pleases—then raise not the mask.

Is Life a poor coil some would gladly be doffing?

He is riding post-haste who their wrongs will adjust;

For at most 'tis a footstep from cradle to coffin—

From a spoonful of pap to a mouthful of dust.

Then smile as your future is smiling, my Jenny!

Though blossoms of promise are lost in the rose,

I still see the face of my small Pic-a-ninny

Unchanged, for these cheeks are as blooming as those.

[72]

Ay, here is your Cradle! much, much to my liking,

Though nineteen or twenty long winters have sped;

But, hark! as I'm talking there's six o'clock striking,

It is time Jenny's baby should be in its bed!

[73]

TO MY MISTRESS.

O Countess, each succeeding year

Reveals that Time is wasting here:

He soon will do his worst by you,

And garner all your roses too!

It pleases Time to fold his wings

Around our best and brightest things;

He'll mar your damask cheek, as now

He stamps his mark upon my brow.

The same mute planets rise and shine

To rule your days and nights as mine,

I once was young as you,—and see...!

You some day will be old as me.

And yet I bear a mighty charm

Which shields me from your worst alarm;

And bids me gaze, with front sublime,

On all these ravages of Time.

[74]

You boast a charm that all would prize,

This gift of mine, which you despise,

May, like enough, still hold its sway

When all your boast has passed away.

My charm may long embalm the lures

Of eyes, as sweet to me as yours:

And ages hence the great and good

Will judge you as I choose they should.

In days to come the count or clown,

With whom I still shall win renown,

Will only know that you were fair

Because I chanced to say you were.

Fair Countess—I wax grey—awhile

Your youthful swains will sigh or smile;

But should you scorn, for smile or sigh,

A grey old Bard—as great as I?

Kenwood, July 21, 1864.

[75]

TO MY MISTRESS'S BOOTS

They nearly strike me dumb,

And I tremble when they come

Pit-a-pat:

This palpitation means

That these boots are Geraldine's—

Think of that!

Oh, where did hunter win

So delicate a skin

For her feet?[76]

You lucky little kid,

You perished, so you did,

For my sweet.

The faery stitching gleams

On the toes, and in the seams,

And reveals

That Pixies were the wags

Who tipped these funny tags,

And these heels.

What soles! so little worn!

Had Crusoe—soul forlorn!—

Chanced to view

One printed near the tide,

How hard he would have tried

For the two!

For Gerry's debonair,

And innocent, and fair

As a rose:

She's an angel in a frock,

With a fascinating cock

To her nose.

Those simpletons who squeeze

Their extremities to please

Mandarins,[77]

Would positively flinch

From venturing to pinch

Geraldine's.

Cinderella's lefts and rights

To Geraldine's were frights:

And, in truth,

The damsel, deftly shod,

Has dutifully trod

From her youth.

The mansion—ay, and more,

The cottage of the poor,

Where there's grief,

Or sickness, are her choice—

And the music of her voice

Brings relief.

Come, Gerry, since it suits

Such a pretty Puss-in-Boots

These to don,

Set your little hand awhile

On my shoulder, dear, and I'll

Put them on.

Albury, June 29, 1864.

[78]

THE ROSE AND THE RING.

(Christmas 1854, and Christmas 1863.)

She smiles—but her heart is in sable,

And sad as her Christmas is chill:

She reads, and her book is the fable

He penned for her while she was ill.

It is nine years ago since he wrought it

Where reedy old Tiber is king,

And chapter by chapter he brought it—

And read her the Rose and the Ring.

[79]

And when it was printed, and gaining

Renown with all lovers of glee,

He sent her this copy containing

His comical little croquis;

A sketch of a rather droll couple—

She's pretty—he's quite t'other thing!

He begs (with a spine vastly supple)

She will study the Rose and the Ring.

It pleased the kind Wizard to send her

The last and the best of his toys,

His heart had a sentiment tender

For innocent women and boys:

And though he was great as a scorner,

The guileless were safe from his sting,—

How sad is past mirth to the mourner!—

A tear on the Rose and the Ring!

She reads—I may vainly endeavour

Her mirth-chequered grief to pursue;

For she hears she has lost—and for ever—

A Heart that was known by so few;

But I wish on the shrine of his glory

One fair little blossom to fling;

And you see there's a nice little story

Attached to the Rose and the Ring!

[80]

TO MY OLD FRIEND POSTUMUS.

(J. G.)

My Friend, our few remaining years

Are hasting to an end,

They glide away, and lines are here

That time will never mend;

Thy blameless life avails thee not,—

Alas, my dear old Friend!

From mother Earth's green orchard trees

The fairest fruit is blown,

The lad was gay who slumbers near,

The lass he loved is gone;

Death lifts the burthen from the poor,

And will not spare the throne.

And vainly are we fenced about

From peril, day and night,

The awful rapids must be shot,

Our shallop is but slight;

So pray, when parting, we descry

A cheering beacon-light.

[81]

O pleasant Earth! This happy home!

The darling at my knee!

My own dear wife! Thyself, old Friend!

And must it come to me

That any face shall fill my place

Unknown to them and thee?

[82]

RUSSET PITCHER.

"The pot goeth so long to the water til at length it commeth

broken home."

Away, ye simple ones, away!

Bring no vain fancies hither;

The brightest dreams of youth decay,

The fairest roses wither.

[83]

Ay, since this fountain first was planned,

And Dryad learnt to drink,

Have lovers held, knit hand in hand,

Sweet parley at its brink.

From youth to age this waterfall

Most tunefully flows on,

But where, ay, tell me where are all

The constant lovers gone?

The falcon on the turtle preys,

And beardless vows are brittle;

The brightest dream of youth decays,—

Ah, love is good for little.

"Sweet maiden, set thy pitcher down,

And heed a Truth neglected:—

The more this sorry world is known,

The less it is respected.

"Though youth is ardent, gay, and bold,

It flatters and beguiles;

Though Giles is young, and I am old,

Ne'er trust thy heart to Giles.

[84]

"Thy pitcher may some luckless day

Be broken coming hither;

Thy doting slave may prove a knave,—

The fairest roses wither."

She laughed outright, she scorned him quite,

She deftly filled her pitcher;

For that dear sight an anchorite

Might deem himself the richer.

Ill-fated damsel! go thy ways,

Thy lover's vows are lither;

The brightest dream of youth decays,

The fairest roses wither.

* * * * *

These days were soon the days of yore;

Six summers pass, and then

That musing man would see once more

The fountain in the glen.

Again to stray where once he strayed,

Through copse and quiet dell,

Half hoping to espy the maid

Pass tripping to the well.

[85]

No light step comes, but, evil-starred,

He finds a mournful token,—

There lies a russet pitcher marred,—

The damsel's pitcher broken!

Profoundly moved, that muser cried,

"The spoiler has been hither;

O would the maiden first had died,—

The fairest rose must wither!"

He turned from that accursèd ground,

His world-worn bosom throbbing;

A bow-shot thence a child he found,

The little man was sobbing.

He gently stroked that curly head,—

"My child, what brings thee hither?

Weep not, my simple one," he said,

"Or let us weep together.

"Thy world, I ween, is gay and green

As Eden undefiled;

Thy thoughts should run on mirth and fun,—

Where dwellest thou, my child?"

[86]

'Twas then the rueful urchin spoke:—

"My daddy's Giles the ditcher,

I fetch the water,—and I've broke ...

I've broke my mammy's pitcher!"

[87]

THE FAIRY ROSE.

"There are plenty of roses," (the patriarch speaks)

"Alas! not for me, on your lips, and your cheeks;

Sweet maiden, rose-laden—enough and to spare,—

Spare, oh spare me the Rose that you wear in your hair."

"O raise not thy hand," cries the maid, "nor suppose

That I ever can part with this beautiful Rose:

The bloom is a gift of the Fays, who declare, it

Will shield me from sorrow as long as I wear it.

"'Entwine it,' said they, 'with your curls in a braid,

It will blossom in winter—it never will fade;

And, when tempted to rove, recollect, ere you hie,

Where you're dying to go—'twill be going to die.'

"And sigh not, old man, such a doleful 'heighho,'

Dost think I possess not the will to say 'No?'

And shake not thy head, I could pitiless be

Should supplicants come more persuasive than thee."

[88]

The damsel passed on with a confident smile,

The old man extended his walk for awhile;

His musings were trite, and their burden, forsooth,

The wisdom of age, and the folly of youth.

Noon comes, and noon goes, paler twilight is there,

Rosy day dons the garb of a penitent fair;

The patriarch strolls in the path of the maid,

Where cornfields are ripe, and awaiting the blade.

And Echo was mute to his leisurely tread,—

"How tranquil is nature reposing," he said;

He onward advances, where boughs overshade,

"How lonely," quoth he—and his footsteps he stayed!

He gazes around, not a creature is there,

No sound on the ground, and no voice in the air;

But fading there lies a poor Bloom that he knows,

—Bad luck to the Fairies that gave her the Rose.

[89]

1863.

These verses were published in 1863, in "A Welcome," dedicated

to the Princess of Wales.

The town despises modern lays:

The foolish town is frantic

For story-books which tell of days

That time has made romantic:

Those days whose chiefest lore lies chill

And dead in crypt and barrow;

When soldiers were—as Love is still—

Content with bow and arrow.

But why should we the fancy chide?

The world will always hunger

To know how people lived and died

When all the world was younger.

We like to read of knightly parts

In maidenhood's distresses:

Of trysts with sunshine in light hearts,

And moonbeams on dark tresses;

[90]

And how, when errant-knyghte or erl

Proved well the love he gave her,

She sent him scarf or silken curl,

As earnest of her favour;

And how (the Fair at times were rude!)

Her knight, ere homeward riding,

Would take—and, ay, with gratitude—

His lady's silver chiding.

We love the "rare old days and rich"

That poesy has painted;

We mourn the "good old times" with which

We never were acquainted.

Last night a lady tried to prove

(And not a lady youthful):

"Ah, once it was no crime to love,

Nor folly to be truthful!"

Absurd! Then dames in castles dwelt,

Nor dared to show their noses:

Then passion that could not be spelt,

Was hinted at in posies.

Such shifts make modern Cupid laugh:

For sweethearts, in love's tremor,

Now tell their vows by telegraph—

And go off in the steamer!

[91]

The earth is still our Mother Earth—

Young shepherds still fling capers

In flowery groves that ring with mirth—

Where old ones read the papers.

Romance, as tender and as true,

Our Isle has never quitted:

So lads and lasses when they woo

Are hardly to be pitied!

Oh, yes! young love is lovely yet—

With faith and honour plighted:

I love to see a pair so met—

Youth—Beauty—all united.

Such dear ones may they ever wear

The roses Fortune gave them:

Ah, know we such a Blessed Pair?

I think we do! God save them!

Our lot is cast on pleasant days,

In not unpleasant places—

Young ladies now have pretty ways,

As well as pretty faces;

So never sigh for what has been,

And let us cease complaining

That we have loved when Our Dear Queen

Victoria was reigning!

[92]

GERALDINE GREEN.

I.

THE SERENADE.

Light slumber is quitting

The eyelids it pressed,

The fairies are flitting,

Who charmed thee to rest:

Where night-dews were falling

Now feeds the wild bee,

The starling is calling,

My Darling, for thee.

The wavelets are crisper

That sway the shy fern,

The leaves fondly whisper,

"We wait thy return."

Arise then, and hazy

Distrust from thee fling,

For sorrows that crazy

To-morrows may bring.

[93]

A vague yearning smote us—

But wake not to weep,

My bark, love, shall float us

Across the still deep,

To isles where the lotos,

Erst lulled thee to sleep.

II.

MY LIFE IS A ——

At Worthing an exile from Geraldine G——,

How aimless, how wretched an exile is he!

Promenades are not even prunella and leather

To lovers, if lovers can't foot them together.

He flies the parade, sad by ocean he stands,

He traces a "Geraldine G." on the sands,

Only "G!" though her loved patronymic is "Green,"—

I will not betray thee, my own Geraldine.

The fortunes of men have a time and a tide,

And Fate, the old Fury, will not be denied;

That name was, of course, soon wiped out by the sea,—

She jilted the exile, did Geraldine G.

[94]

They meet, but they never have spoken since that,—

He hopes she is happy—he knows she is fat;

She woo'd on the shore, now is wed in the Strand,—

And I—it was I wrote her name on the sand!

[95]

MRS. SMITH.

Last year I trod these fields with Di,

And that's the simple reason why

They now seem arid:

Then Di was fair and single—how

Unfair it seems on me—for now

Di's fair, and married.

[96]

In bliss we roved. I scorned the song

Which says that though young Love is strong

The Fates are stronger:

Then breezes blew a boon to men—

Then buttercups were bright—and then

This grass was longer.

That day I saw, and much esteemed

Di's ankles—which the clover seemed

Inclined to smother:

It twitched, and soon untied (for fun)

The ribbons of her shoes—first one,

And then the other.

'Tis said that virgins augur some

Misfortune if their shoestrings come

To grief on Friday:

And so did Di—and so her pride

Decreed that shoestrings so untied,

"Are so untidy!"

Of course I knelt—with fingers deft

I tied the right, and then the left:

Says Di—"This stubble

Is very stupid—as I live

I'm shocked—I'm quite ashamed to give

You so much trouble."

[97]

For answer I was fain to sink

To what most swains would say and think

Were Beauty present:

"Don't mention such a simple act—

A trouble? not the least. In fact

It's rather pleasant."

I trust that love will never tease

Poor little Di, or prove that he's

A graceless rover.

She's happy now as Mrs. Smith—

But less polite when walking with

Her chosen lover.

Heigh-ho! Although no moral clings

To Di's soft eyes, and sandal strings,

We've had our quarrels!—

I think that Smith is thought an ass,

I know that when they walk in grass

She wears balmorals.

[98]

THE SKELETON IN THE CUPBOARD.

The characters of great and small

Come ready made, we can't bespeak one;

Their sides are many, too,—and all

(Except ourselves) have got a weak one.

Some sanguine people love for life—

Some love their hobby till it flings them.—

And many love a pretty wife

For love of the éclat she brings them!

We all have secrets—you have one

Which may not be your charming spouse's,—

We all lock up a skeleton

In some grim chamber of our houses;

Familiars who exhaust their days

And nights in probing where our smart is,

And who, excepting spiteful ways,

Are quiet, confidential "parties."

[99]

We hug the phantom we detest,

We rarely let it cross our portals:

It is a most exacting guest,—

Now are we not afflicted mortals?

Your neighbour Gay, that joyous wight,

As Dives rich, and bold as Hector,

Poor Gay steals twenty times a-night,

On shaking knees, to see his spectre.

Old Dives fears a pauper fate,

And hoarding is his thriving passion;

Some piteous souls anticipate

A waistcoat straiter than the fashion.

She, childless, pines,—that lonely wife,

And hidden tears are bitter shedding;

And he may tremble all his life,

And die,—but not of that he's dreading.

Ah me, the World! how fast it spins!

The beldams shriek, the caldron bubbles;

They dance, and stir it for our sins,

And we must drain it for our troubles.

We toil, we groan,—the cry for love

Mounts upward from this seething city,

And yet I know we have above

A Father, infinite in pity.

[100]

When Beauty smiles, when Sorrow weeps,

When sunbeams play, when shadows darken,

One inmate of our dwelling keeps

A ghastly carnival—but hearken!

How dry the rattle of those bones!—

The sound was not to make you start meant,—

Stand by! Your humble servant owns

The Tenant of this Dark Apartment.

[101]

THE VICTORIA CROSS.

A LEGEND OF TUNBRIDGE WELLS.

She gave him a draught freshly drawn from the springlet,—

O Tunbridge, thy waters are bitter, alas!

But Love finds an ambush in dimple and ringlet,—

"Thy health, pretty maiden!"—he emptied the glass.

He saw, and he loved her, nor cared he to quit her,

The oftener he came, why the longer he stayed;

Indeed, though the spring was exceedingly bitter,

We found him eternally pledging the maid.

A preux chevalier, and but lately a cripple,

He met with his hurt where a regiment fell,

But worse was he wounded when staying to tipple

A bumper to "Phœbe, the Nymph of the Well."

[102]

Some swore he was old, that his laurels were faded,

All vowed she was vastly too nice for a nurse;

But Love never looked on such matters as they did,—

She took the brave soldier for better or worse.

And here is the home of her fondest election,—

The walls may be worn but the ivy is green;

And here has she tenderly twined her affection

Around a true soldier who bled for his Queen.

See, yonder he sits, where the church flings its shadows;

What child is that spelling the epitaphs there?

To that imp its devout and devoted old dad owes

New zest in thanksgiving—fresh fervour in prayer.

Ere long, ay, too soon, a sad concourse will darken

The doors of that church, and that tranquil abode;

His place then no longer will know him—but, hearken,

The widow and orphan appeal to their God.

Much peace will be hers! "If our lot must be lowly,

Resemble thy father, though with us no more;"

And only on days that are high or are holy,

She will show him the cross that her warrior wore.

[103]

So taught, he will rather take after his father,

And wear a long sword to our enemies' loss;

Till some day or other he'll bring to his mother

Victoria's gift—the Victoria Cross!

And still she'll be charming, though ringlet and dimple

Perchance may have lost their peculiar spell;

And at times she will quote, with complacency simple,

The compliments paid to the Nymph of the Well.

And then will her darling, like all good and true ones,

Console and sustain her,—the weak and the strong;—

And some day or other two black eyes or blue ones

Will smile on his path as he journeys along.

Wherever they win him, whoever his Phœbe,

Of course of all beauties she must be the belle,

If at Tunbridge he chance to fall in with a Hebe,

He will not fall out with a draught from the Well.

[104]

ST. GEORGE'S, HANOVER SQUARE.

Dans le bonheur de nos meilleurs amis nous trouvons souvent

quelque chose qui ne nous plaît pris entièrement.

She passed up the aisle on the arm of her sire,

A delicate lady in bridal attire,—

Fair emblem of virgin simplicity;—

Half London was there, and, my word, there were few,

Who stood by the altar, or hid in a pew,

But envied Lord Nigel's felicity.

O beautiful Bride, still so meek in thy splendour,

So frank in thy love, and its trusting surrender,

Departing you leave us the town dim!

May happiness wing to thy bosom, unsought,

And Nigel, esteeming his bliss as he ought,

Prove worthy thy worship,—confound him!

[105]

SORRENTO.

Sorrento, stella d'amore.—Vincenzo da Filicaia.

Sorrento! Love's Star! Land

Of myrtle and vine,

I come from a far land

To kneel at thy shrine;

Thy brows wear a garland,

Oh, weave one for mine!

Thine image, fair city,

Smiles fair in the sea,—

A youth sings a pretty

Song, tempered with glee,—

The mirth and the ditty

Are mournful to me.

Ah, sea boy, how strange is

The carol you sing!

Let Psyche, who ranges

The gardens of Spring,

Remember the changes

December will bring.

March, 1862.

[106]

JANET.

I see her portrait hanging there,

Her face, but only half as fair,

And while I scan it,

Old thoughts come back, by new thoughts met—

She smiles. I never can forget

The smile of Janet.

A matchless grace of head and hand,

Can Art pourtray an air more grand?

It cannot—can it?

And then the brow, the lips, the eyes—

You look as if you could despise

Devotion, Janet.