The Project Gutenberg EBook of Lola Montez, by Edmund B. d'Auvergne

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net

Title: Lola Montez

An Adventuress of the 'Forties

Author: Edmund B. d'Auvergne

Release Date: January 6, 2012 [EBook #38512]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK LOLA MONTEZ ***

Produced by The Online Distributed Proofreading Team at

http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images

generously made available by The Internet Archive.)

UNIFORM LIBRARY EDITION OF THE WORKS OF GUY DE MAUPASSANT, newly translated into English by Marjorie Laurie.

Volume 1. BEL-AMI.

“Bel-Ami” is an extraordinarily fine full-length portrait of an unscrupulous rascal who exploits his success with women for the furtherance of his ambitions. The book simmers with humorous observations, and, as a satire on politics and journalism, is no less biting because it is not bitter.

Volume 2. A LIFE.

This story of a woman’s life, harrowed first by the faithlessness of her husband and later by the worthlessness of her son, has been described as one of the saddest books that has ever been written; it is remorseless in its utter truthfulness.

Volume 3. “BOULE DE SUIF” and other Short Stories.

A story of the part played by a little French prostitute in an incident of the war of 1870. It was published in a collection of tales by distinguished French writers of the day, and was so clearly the gem of the collection that it established the Author at once as a master.

Volume 4. THE HOUSE OF TELLIER.

LOLA MONTEZ.

Countess of Landsfeld

LOLA MONTEZ

AN ADVENTURESS OF THE ’FORTIES

BY

EDMUND B. d’AUVERGNE

ILLUSTRATED

LONDON

T. WERNER LAURIE, LTD.

30 NEW BRIDGE STREET, E.C.4

First Printed April 1909

Second Edition, December 1909

Third Impression, November 1924

Fourth Impression, February 1925

Printed in Great Britain by

Fox, Jones & Co., at the Kemp Hall Press, Oxford, England

The story of a brave and beautiful woman, whose fame filled Europe and America within the memory of our parents, seems to be worth telling. The human note in history is never more thrilling than when it is struck in the key of love. In what were perhaps more virile ages, the great ones of the earth frankly acknowledged the irresistible power of passion and the supreme desirability of beauty. Their followers thought none the less of them for being sons of Adam. Lola Montez was the last of that long and illustrious line of women, reaching back beyond Cleopatra and Aspasia, before whom kings bent in homage, and by whose personality they openly confess themselves to be swayed. Since her time man has thrown off the spell of woman’s beauty, and seems to dread still more the competition of her intellect.

Lola Montez, some think, came a century too late; “in the eighteenth century,” said Claudin, “she would have played a great part.” The part she played was, at all events, stirring and strange enough. The most spiritually and æsthetically minded sovereign in[Pg vi] Europe worshipped her as a goddess; geniuses of coarser fibre, such as Dumas, sought her society. She associated with the most highly gifted men of her time. Equipped only with the education of a pre-Victorian schoolgirl, she overthrew the ablest plotters and intriguers in Europe, foiled the policy of Metternich, and hoisted the standard of freedom in the very stronghold of Ultramontane and reactionary Germany.

Driven forth by a revolution, she wandered over the whole world, astonishing Society by her masculine courage, her adaptability to all circumstances and surroundings. She who had thwarted old Europe’s skilled diplomatists, knew how to horsewhip and to cow the bullies of young Australia’s mining camps. An indifferent actress, her beauty and sheer force of character drew thousands to gaze at her in every land she trod. So she flashed like a meteor from continent to continent, heard of now at St. Petersburg, now at New York, now at San Francisco, now at Sydney. She crammed enough experience into a career of forty-two years to have surfeited a centenarian. She had her moments of supreme exaltation, of exquisite felicity. Her vicissitudes were glorious and sordid. She was presented by a king to his whole court as his best friend; she was dragged to a London police-station on a charge of felony. But in prosperity she never lost her head, and in adversity she never lost her courage.

[Pg vii]A splendid animal, always doing what she wished to do; a natural pagan in her delight in life and love and danger—she cherished all her life an unaccountable fondness for the most conventional puritanical forms of Christianity, dying at last in the bosom of the Protestant Church, with sentiments of self-abasement and contrition that would have done credit to a Magdalen or Pelagia.

In my sympathy with this fascinating woman, it is possible that I have exaggerated the importance of her rôle; probable, also, that I have digressed too freely into reflections on her motives and on the forces with which she had to contend. Those who prefer a bare recital of the facts of her career, I refer at once to the admirable epitome to be found in the “Dictionary of National Biography.” Here I have not hesitated to include all that seemed to me to throw light on the subject of my sketch, on the people around her, and on the influences that shaped her destiny.

Edmund B. d’Auvergne.

| CHAP. | PAGE | |

| I. | CHILDHOOD | 1 |

| II. | A RUNAWAY MATCH | 11 |

| III. | FIRST STEPS IN MATRIMONY | 17 |

| IV. | INDIA SEVENTY YEARS AGO | 21 |

| V. | RIVEN BONDS | 31 |

| VI. | LONDON IN THE ’FORTIES | 39 |

| VII. | WANDERJAHRE | 47 |

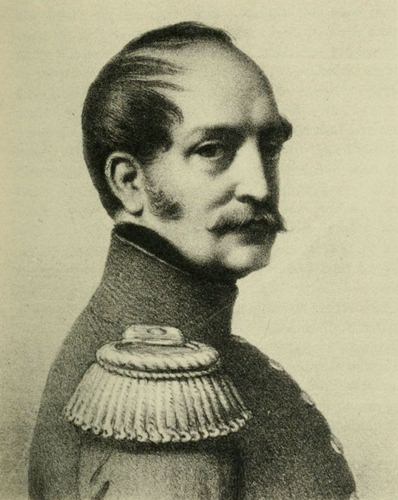

| VIII. | FRANZ LISZT | 59 |

| IX. | AT THE BANQUET OF THE IMMORTALS | 65 |

| X. | MÉRY | 75 |

| XI. | DUJARIER | 79 |

| XII. | THE SUPPER AT THE FRÈRES PROVENÇAUX | 83 |

| XIII. | THE CHALLENGE | 87 |

| XIV. | THE DUEL | 95 |

| XV. | THE RECKONING | 101 |

| XVI. | IN QUEST OF A PRINCE | 107 |

| XVII. | THE KING OF BAVARIA | 111 |

| XVIII. | REACTION IN BAVARIA | 121 |

| XIX. | THE ENTHRALMENT OF THE KING | 125 |

| XX. | THE ABEL MEMORANDUM | 135 |

| [Pg x]XXI. | THE INDISCRETIONS OF A MONARCH | 143 |

| XXII. | THE MINISTRY OF GOOD HOPE | 149 |

| XXIII. | THE UNCROWNED QUEEN OF BAVARIA | 157 |

| XXIV. | THE DOWNFALL | 163 |

| XXV. | THE RISING OF THE PEOPLES | 173 |

| XXVI. | LOLA IN SEARCH OF A HOME | 177 |

| XXVII. | A SECOND EXPERIMENT IN MATRIMONY | 181 |

| XXVIII. | WESTWARD HO! | 193 |

| XXIX. | IN THE TRAIL OF THE ARGONAUTS | 199 |

| XXX. | IN AUSTRALIA | 205 |

| XXXI. | LOLA AS A LECTURER | 213 |

| XXXII. | A LAST VISIT TO ENGLAND | 219 |

| XXXIII. | THE MAGDALEN | 223 |

| XXXIV. | LAST SCENE OF ALL | 227 |

| SOURCES OF INFORMATION | 234 |

| LOLA MONTEZ, COUNTESS OF LANDSFELD | Frontispiece | |

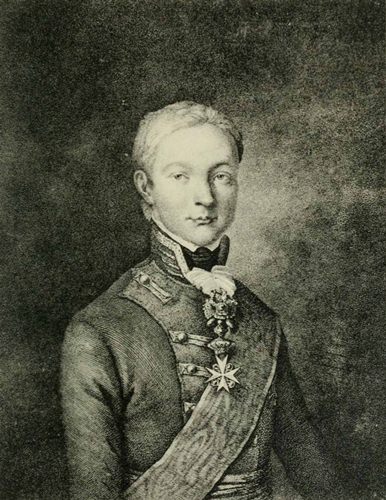

| NICHOLAS I. | To face page | 54 |

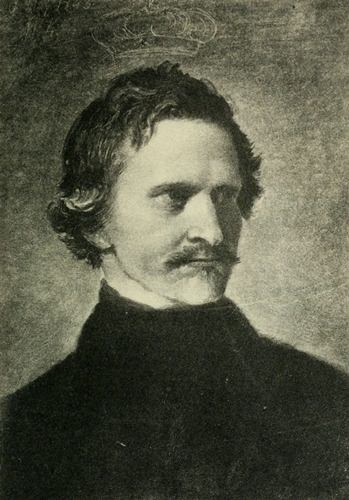

| FRANZ LISZT | " | 60 |

| ALEXANDRE DUMAS, SENIOR | " | 70 |

| LOUIS OF BAVARIA, WHEN ELECTORAL PRINCE | " | 112 |

| LOUIS I, KING OF BAVARIA | " | 144 |

| LOLA MONTEZ (AFTER JULES LAURE) | " | 194 |

LOLA MONTEZ

AN ADVENTURESS OF THE ’FORTIES

CHILDHOOD

The year 1818 was, on the whole, a good starting-point in life for people with a taste and capacity for adventure. This was not suspected by those already born. They looked forward, after the tempest that had so lately ravaged Europe, to a golden age of slippered ease and general stagnation. The volcanoes, they hoped, were all spent. “We have slumbered seven years, let us forget this ugly dream,” complacently observed a German prince on resuming possession of his dominions; and “the old, blind, mad, despised, and dying king’s” worthy regent expressed the same confidence when he gave the motto, “A sign of better times,” to an order founded in this particular year. Yet the child that thus with royal encouragement began life in England at that time learned before he could toddle to tremble at the mysterious name of “Boney,” and later on would thrill with fear, delight, and horror at his nurse’s recital of[Pg 2] the atrocities and final glorious undoing of that terrific ogre. Presently he would meet in his walks abroad, red-coated, bewhiskered veterans who had met the monster face to face (or said they had); who would recount stories of decapitated kings, dreadful uprisings, and threatened invasions; who had lost a leg or an arm or an eye at Waterloo or Salamanca; which victories (they assured him) were mainly due to their individual valour and generalship. As the child grew older he would begin to make a coherent story out of these strange happenings: he would realise through what a period of storm and stress the world had passed immediately before his advent. He would listen eagerly at his father’s table to more trustworthy relations of the great battles by men whose share in them his country was proud to acknowledge. Waterloo, Trafalgar, the Nile, would be fought over again in the school playground. For the best part of his life he might expect to have as contemporaries, men who had seen Napoleon with their own eyes, and shaken Nelson by his one hand—men who had seen thrones that seemed as stable as the everlasting hills come crashing down, to be pieced together with a cement of blood and gunpowder. How often the boy, or, as in this particular case, the girl, must have longed for a recurrence of those brave days, and deprecated the peaceful present. But for him (or her) far more amazing things were in store. His it was to see society emerge from its worn-out feudal chrysalis, and to take the path which may yet lead to civilisation. Those born in 1818 could have the delightful distinction of being carried in the first railway train, of sending the first “wire,” of boarding the first “penny ’bus.” Born in the age of the coach and the hoy, they would die in[Pg 3] the era of the locomotive and mail steamer. Theirs was an age of transition indeed, most curious to watch, most thrilling to traverse. And—most valuable privilege of all to those that loved to play a part in great affairs—they would be in good time to assist at the widest spread and most terrific upheaval Europe had known since the downfall of the Roman Empire. To have been thirty years of age in that year of years, 1848! Those who witnessed the great drama must have felt that to have come into the world more than three decades before would have been a mistake the most grievous.

Among the children fortunate enough, then, to be born when the nineteenth century was in its eighteenth year was the heroine of our history. Limerick, the city of the broken treaty, was her birthplace, Maria Dolores Eliza Rosanna the names bestowed upon her in baptism. Only a year before (on 3rd July 1817) her father, Edward Gilbert, had been gazetted an ensign in the old 25th regiment of the line, now the King’s Own Scottish Borderers. He may have been, as his daughter and only child afterwards claimed, the scion of a knightly house, but he could boast a far more honourable distinction—that he rose from the ranks and earned his commission by valour and good conduct in the long Napoleonic wars.[1] Promotion it was, perhaps, that emboldened him to marry in the same year. His wife was a girl of surpassing beauty, a Miss Oliver, of Castle Oliver, wherever that may be, and a descendant of the Count de Montalvo, a Spanish grandee, who had lost his immense estates in the wars. The ancestors of this[Pg 4] unfortunate noble (we are told) were Moors, and came into Spain in the reign of Ferdinand and Isabella, which was certainly the worst possible moment they could have chosen for so doing. For this account of Mrs. Gilbert’s ancestry we are indebted to her daughter, whose names certainly suggest a Spanish origin. It was by her mournful second name, or rather by its lightsome diminutive, Lola, that she was ever afterwards known. Perhaps she was so called in remembrance of one of the proud Montalvos. At all events, she never ceased to cherish the belief in her half-Spanish blood. When she was a romantic young girl—for young girls were romantic seventy years ago—Spain obsessed the Byronic caste of mind. It was regarded as the home of chivalry, romance, love, poetry, and adventure. To be ever so little Spanish was accounted a most enviable distinction. So it would be ungenerous of us to impugn Lola’s claim to what she and her contemporaries considered an inestimable privilege. True or false, the idea was one she imbibed with her mother’s milk—though I forgot to say that, according to her own statement, she was nourished at this early period by an Irish nurse. I wish I could say in what religion the new daughter of the regiment was educated. Somewhere she says that her mother eloped with her father from a convent. The strong dislike she manifested in after years for the Roman Catholic Church may have been inspired by this circumstance, and suggests, at any rate, in one not keenly sensible of nice theological distinctions, some personal motive arising from a bitter experience.

If the baby Lola gave promise of the woman, Edward Gilbert must have been proud of his child—as proud of her as of his pretty wife and his hard-won commission.[Pg 5] But those years in troubled Ireland must have been anxious ones for him. There is no evidence that he possessed private means, and to support a wife and child on the pay of an ensign in a marching regiment would necessitate economies of the most painful description. In the East, now that Europe was at peace, lay the only hope of immediately increased pay and rapid promotion. The establishment of the King’s Own Scottish Borderers was reduced, in August 1822, from ten to eight companies, and Gilbert was able to obtain, in consequence, a transfer to the 44th of the line, already under orders for India. His appointment to his new regiment—now the first battalion Essex regiment—is dated 10th October 1822. With his young wife and child he embarked, accordingly, for the land of promise. Probably the four-year-old Lola endured best of the three the unspeakable fatigue and tedium of that long, long journey round the Cape—a voyage which in those days it was no uncommon thing to prolong by a call at Rio de Janeiro. It was not till four months had been passed at the mercy of wind and wave that our weary travellers set foot in Calcutta.

The regiment was stationed at Fort William, and there the ensign’s hopes of speedy advancement early received encouragement. At one time seventeen of his brother officers lay sick with the fever, and before six months had fled, the last post was sounded over the graves of Major Guthrie, Captain O’Reilly, and Lieutenants Twinberrow and Sargent. The unspoken question on every one’s lips was, Whose turn next? In this Indian pest-house there must have been moments when the young mother, fearful for her husband and child, longed fiercely for the rain-drenched streets of[Pg 6] Limerick. At last the regiment was ordered to Dinapore. The journey was effected, as was usual in those days, by water, an element to which the Gilberts were now well accustomed. But here, instead of the monotonous expanse of ocean, they had slowly unfolded before them the strange and brightly-coloured panorama of the East—gorgeous, teeming cities, the dreadful, burning ghâts, rank jungle, dense forests, rich rice-fields. As the flotilla travelled only 12 or 14 miles a day, the passengers had ample time to stretch their limbs ashore, and to visit the towns and villages passed en route. The voyage, too, did not lack incident. On one occasion nine boats were swamped, and eight British redcoats went to swell the horrible procession of corpses which floats ever seaward down the Sacred River. Another night the Colonel’s boat took fire, and the flames, spreading to other vessels, consumed the regimental band’s music and instruments, which were so sorely needed to revive the drooping spirits of the fever-stricken troops.

However, in the excitement of taking up their new quarters at Dinapore, these evil omens were, no doubt, forgotten. Pretty women were rare in India in those days, and Mrs. Gilbert received (from the men, at all events) a right royal welcome. She was acclaimed queen of the station, and, as her husband, the Ensign, became, of course, a person of consequence. This was better than Ireland, after all. Dinapore was a fairly lively spot, and regimental society was not overshadowed, as at Calcutta, by the magnates of Government House. So Lola’s mother flirted and danced, while Lola herself was petted by grey-haired generals and callow subs., and Lola’s father began to dream of a[Pg 7] captaincy. One day, in the early part of 1824, his place at the mess-table was vacant. The doctor looked in, and said “Cholera,” and a few faces blanched. Craigie, the Ensign’s best friend, hurried to his bedside. The dying man was speechless, but conscious. Beckoning to his friend, he placed his weeping wife’s hand in his, and, having thus conveyed his last wish, died.

Lola was left fatherless before she was seven years old. She and her mother, she tells us, were promptly taken charge of by the wife of General Brown.

“The hearts of a hundred officers, young and old, beat all at once with such violence, that the whole atmosphere for ten miles round fairly throbbed with the emotion. But in this instance the general fever did not last long, for Captain Craigie led the young widow Gilbert to the altar himself. He was a man of high intellectual accomplishments, and soon after this marriage his regiment was ordered back to Calcutta, and he was advanced to the rank of major.”

We are thus able to identify Lola’s stepfather with John Craigie of the Bengal Army, who was gazetted Captain on 11th May 1816, and Major, 18th May 1825. Four years later he attained the rank of Lieutenant-Colonel.[2] He seems to have been a generous, warm-hearted man, who never forgot the trust placed in him by his dying friend at Dinapore. To him Lola was indebted for such education as she received in India. That was not of a very thorough character. With a mother who, we learn, was passionately fond of society and amusement, little Miss Gilbert must have passed most of her time in the company of ayahs and orderlies,[Pg 8] picking up the native tongue with the facility which distinguished her in after life, and domineering tremendously over idolatrous sepoys and dignified khansamahs. I can imagine her on the knees of veterans at her father’s table, delighting them with her beauty, and still more with her boldness and childish ready wit. Of course, His Excellency (Lord William Bentinck) would take notice of the pretty, pert child of handsome Mrs. Craigie, and it is not to be wondered at that all her life she should hanker after the atmosphere of a court, remembering the vice-regal glories at Calcutta.

It seems to have dawned upon Mrs. Craigie, not very long after her second marriage, that her daughter was, to use a common expression, running wild. A little discipline, it was felt, would do her good. It was decided to send her home to her stepfather’s relatives at Montrose. With screams, sobs, and wild protests, the eight-year-old girl accordingly found herself torn from the redcoats and brown faces that she loved, once more to undertake that terrible four months’ journey to a land which she had probably completely forgotten.

The contrast between Calcutta, the gorgeous city of palaces, and Montrose, the dour, wintry burgh among the sandhills by the northern sea, must have chilled the heart of the passionate child. Yet she does not seem in after life to have thought with any bitterness of the place, and speaks with respect, if not affection, of her new guardian, Major Craigie’s father. She writes:—

“This venerable man had been provost of Montrose for nearly a quarter of a century, and the dignity of his profession, as well as the great respectability of[Pg 9] his family, made every event connected with his household a matter of some public note, and the arrival of the queer, wayward, little East Indian girl was immediately known to all Montrose. The peculiarity of her dress, and I dare say not a little eccentricity in her manners, served to make her an object of curiosity and remark; and very likely she perceived that she was somewhat of a public character, and may have begun, even at this early age, to assume airs and customs of her own.”

That is, indeed, very likely. Further information concerning our heroine’s stay at Montrose we have little. She does not seem to have retained any very vivid impressions of her childhood. One of the few events in the meagre history of the little Scots town she was privileged to witness—the erection of the suspension bridge from Inchbrayock over the Esk. Here it was, too, that she formed that friendship with the girl, afterwards Mrs. Buchanan, which was destined to form her greatest consolation in the evening of her days. The Craigies were strict Calvinists, and some of her biographers have assumed, in consequence, that they must have treated the child with rigour and inspired her with a distaste for religion. She never said so, as far as I can ascertain. On the contrary, throughout her life she evinced a marked bias in favour of Protestantism, which is quite as compatible with an erotic temperament as was the zeal for Catholicism displayed by the favourite mistress of Charles II.

Her parents, says Lola, being somehow impressed with the idea that she was being petted and spoiled (by the gloomy Calvinists aforesaid), she was removed to the family of Sir Jasper Nicolls, of London. It is to be[Pg 10] observed that neither now nor after do we hear of her father’s relatives, who one would suppose to have been her proper guardians. This circumstance certainly discountenances the theory of Edward Gilbert’s exalted parentage. Sir Jasper Nicolls, K.C.B., Major-General, was succeeded by Major-General Watson in the command of the Meerut Division in 1831, in which year it may be presumed he returned to England, and took his friend Craigie’s stepdaughter under his wing. Like most Indian officers, he preferred to spend his pension out of England, and gladly hurried his girls off to Paris to complete their education. They missed the July Revolution by a year; but all France was presently ringing with the exploits of the brave Duchesse de Berry, who became the idol of the pensionnats. To Lola, no doubt, she seemed a heroine worthier of imitation than the young Princess Alexandrina Victoria, who was just then touring her uncle’s dominions. The romantic fever was at its height in Paris. To her schoolfellows the beautiful Anglo-Indian girl, with her Spanish name and ancestry, must have appeared a new edition of De Musset’s “Andalouse.” The influences about her at this time tended to stimulate all that was romantic and adventurous in her temperament, and determined, perhaps, her action in the first great crisis of her life.

A RUNAWAY MATCH

It was now fifteen years since Mrs. Craigie had visited England, and rather more than ten since she had seen her daughter. She had been made aware that Lola’s beauty far exceeded the promise of her childish years, and this she took care to make known to all the eligible bachelors of Bengal. The charms of the erstwhile pet of the 44th were eagerly discussed by men who had never seen her. Lonely writers in up-country stations brooded on her perfections, as advertised by Mrs. Craigie, and came to the conclusion that she was precisely the woman wanted to convert their secluded establishments into homes. It was difficult to get a wife of the plainest description in the India of William IV.’s day, and the competition for the hand of the unknown beauty oversea was proportionately keen. If marriage by proxy were recognised by English law Lola’s fate would have been sealed long before she was aware of it. From a worldly point of view the most desirable of these ardent suitors was Sir Abraham Lumley, whom our heroine unkindly describes as a rich and gouty old rascal of sixty years, and Judge of the Supreme Court in India. We see that in that rude age it was not the custom to speak of sexagenarians as in the prime of life. To the venerable[Pg 12] magistrate Mrs. Craigie promised her daughter in marriage. Remembering the hard times she had gone through with her first husband, the penniless ensign, and forgetting, as we do when past thirty, how those hardships were lightened by love, she no doubt felt that she had acted extremely well by her daughter. Women’s ideas on the subject of marriage are usually absolutely conventional, and since unions between men of sixty and girls of eighteen are not condemned by the official exponents of religion, you would never have persuaded Mrs. Craigie that they were immoral. Outside the Decalogue (and the Police Regulations) all things are lawful. Well pleased with herself, the still handsome Anglo-Indian lady sailed for home in the early part of the year 1837, proposing to bring her daughter back with her to the bosom of Abraham.

She found Lola at Bath, whither she had been sent from Paris with Fanny Nicolls “to undergo the operation of what is properly called finishing their education.” I do not suppose the meeting between mother and daughter was especially cordial, considering the temperament of the former and the long period of separation, but Mrs. Craigie was delighted to find that report had nowise exaggerated the young girl’s charms. This was also the private opinion of Mr. Thomas James, a lieutenant in the 21st regiment of Native Infantry (Bengal), a young officer who had attached himself to Mrs. Craigie on the voyage and accompanied her to Bath. The mother thought him quite safe, as he had told her that he was betrothed, and had consulted her about his prospects, or, rather, the want of them. The married ladies of India have always been full of maternal solicitude for poor young subalterns, who frequently[Pg 13] repay their kindness with touching devotion. It was probably the wish to be useful to his benefactress that had drawn Mr. James to Bath. Or it may have been that he wished to drink the waters, for I forgot to say that he had been ill during the voyage, and owed his recovery to Mrs. Craigie’s careful nursing.

Lola was staggered by the kindness and liberality of her mother. Visits to the milliner’s and the dressmaker’s succeeded each other with startling rapidity; jewellery, lingerie, all sorts of delightful things were showered upon her in bewildering profusion. Lieutenant James was kept on his legs all day, escorting the ladies to the modistes and running errands to Madame Jupon and Mademoiselle Euphrosine. At last the girl began to suspect that there must be some other motive for this excessive interest in her personal appearance than maternal fondness. She made bold one day (she tells us) to ask her mother what this was all about, and received for an answer that it did not concern her—that children should not be inquisitive, nor ask idle questions. (Lola is the only girl on record who protested that too much money was being spent on her wardrobe.) Her suspicions naturally increased tenfold. In her perplexity she sought information from the Lieutenant, of whose interest in her she had probably become conscious. Then she learnt the horrible truth. The wardrobe so fast accumulating was her trousseau, and she was the promised bride of a man in India old enough to be her grandfather. For a moment Lola was stunned. For a full-blooded, passionate girl of eighteen the prospect was hideous. We may be sure, too, that her informant did not understate the personal disadvantages of Sir Abraham Lumley. Neither did he neglect this[Pg 14] favourable opportunity to declare his own passion for the proposed victim, and to press his suit. An interview with Mrs. Craigie followed.

“The little madcap cried and stormed alternately. The mother was determined—so was her child; the mother was inflexible—so was her child; and in the wildest language of defiance she told her that she never would be thus thrown alive into the jaws of death.

“Here, then, was one of those fatal family quarrels, where the child is forced to disobey parental authority, or to throw herself away into irredeemable wretchedness and ruin. It is certainly a fearful responsibility for a parent to assume of forcing a child to such alternatives. But the young Dolores sought the advice and assistance of her mother’s friend....”

She was probably a little in love with that friend, who was a fine-looking fellow, about a dozen years older than herself, and who had certainly conceived a violent passion for her. The situation was conventionally romantic. The books of that time were full of distressed damsels being forced into hateful unions. Lola, it is safe to say, relished her new rôle of heroine not a little. So when her lover proposed a runaway match, she felt that she was bound to comply with the usual stage directions. After all, what could be more delightful?—an elopement in a post-chaise with a dashing young officer, an angry mamma in pursuit, and, happily, no angry papa, armed with pistols or horse-whip.

Away they went. Lola has left us no particulars of the flight. The runaways reappear, in the first month of Queen Victoria’s reign, in the girl’s native land, where she was placed under the protection of her lover’s[Pg 15] family. “They had a great muss [sic] in trying to get married.” Lola was under age, and her mother’s consent was indispensable. James sent his sister to Bath to intercede with Mrs. Craigie. The lady was furious. Not only had her daughter upset her most cherished project, but had run off with her most devoted friend and admirer. Mrs. Craigie was a prey to the most mortifying reflections. No doubt she asked Miss James what had become of the young lady to whom her brother had declared he was affianced. She probably said some very unkind things about the Lieutenant. At last, however, “good sense so far prevailed as to make her see that nothing but evil and sorrow could come of her refusal, and she consented, but would neither be present at the wedding, nor send her blessing.” We are not told if she sent the voluminous trousseau, which had been the cause of all the mischief. She returned soon after, I gather, to India, to announce to the unfortunate Sir Abraham the collapse of his matrimonial scheme.

Miss James returned to Ireland with the necessary authority, and Thomas James, Lieutenant, and Maria Dolores Eliza Rosanna Gilbert, spinster, were made man and wife in County Meath on the 23rd July 1837. The bride’s reflections on this event are worth quoting:—

“So, in flying from that marriage with ghastly and gouty old age, the child lost her mother, and gained what proved to be only the outside shell of a husband, who had neither a brain which she could respect, nor a heart which it was possible for her to love. Runaway matches, like runaway horses, are almost sure to end in a smash up. My advice to all young girls who contemplate taking such a step is, that they had better hang or drown themselves just one hour before they start.”

[Pg 16]This warning was obviously intended to counteract the dreadful example of the writer’s subsequent life and adventures, and to dissuade ambitious young ladies from following in her footsteps. Lola did not, of course, believe what she said. Even “when wild youth’s past” and the glamour of love has worn thin, no sensible woman could believe that she would have got much happiness out of life if it had been passed in wedlock with a man half a century her senior. Perhaps, however, Lola sadly reflected that if she had become Sir Abraham’s wife, she would probably have become his widow a very few years after.

FIRST STEPS IN MATRIMONY

Thus Lola found herself in Ireland, the wife of a penniless subaltern—exactly the position of her mother twenty years before. “All for love and the world well lost,” she might have exclaimed. There is no reason to suppose that disillusionment came to her any sooner than to other hot-headed and romantic young ladies similarly placed. She was accustomed to view her early married life in the bitter light of subsequent experience, and forgot all the sweets and raptures of first love. Women of her temperament always find it hard to believe that they ever really loved men whom they have since learned to hate. Even by her own account, those months in Ireland were not altogether unrelieved by the glitter for which her soul craved. Her husband took her to Dublin, she informs us, and presented her to the Lord-Lieutenant. His Excellency Lord Normanby was one of the few good rulers England has placed over Ireland, and like most clever men, he was an admirer of pretty women. Lola seems to have been made much of by him. He paid her many compliments, among others this, “Women of your age are the queens of society”—a remark which may be addressed with equally good effect to ladies anywhere between seventeen and seventy.[Pg 18] Mr. James began to grow restive under the fire of admiration directed by great personages upon his young wife. It is not impossible to believe that she flirted. Her husband decided to withdraw her from the seductions of the viceregal court, and retired with her to some spot in the interior, the name of which has not been transmitted to us. Lola, in memoirs she contributed years after to a Parisian newspaper, describes her life in this retreat as unutterably tedious. The day was passed in hunting and eating, these exercises succeeding each other with the utmost regularity. Meanwhile, the system was sustained by innumerable cups of tea, taken at stated intervals, and with much deliberateness.

Ireland had changed since the emancipation of the Catholics. It was not with tea that the heroes of Charles Lever’s time beguiled the tedium of existence.

“This dismal life,” continues our heroine, “weighed on me to such an extent that I should assuredly have done something desperate if my husband had not just then been ordered to return to India.” Lola, it will have been seen, entertained little affection for her native land. She had no recollection of her childhood there, and she never afterwards thought of the country except in connection with the detested husband of her youth.

In the second year of the Queen’s reign she left Ireland, to return years after in very different circumstances. Her fondest memories were of the East, towards which she now gladly turned her face for the second time. “On the old trail, on the out trail,” she sailed aboard the East Indiaman, Blunt, her husband at her side. There is a curious parallelism between her mother’s life and her own up till now, which she could[Pg 19] not have failed to notice. Her memories of the voyage strike me rather as having been specially spiced for the consumption of Parisian readers, than as an authentic relation. James, we are told, neglected his young wife, and exhibited an amazing capacity for absorbing porter. Finding the time heavy on her hands, Lola resorted to the commonest of all distractions on passenger ships—flirting. While her consort lay sleeping “like a boa-constrictor” in his bunk, his wife’s admirers used to slip notes under the door, these serving her as spills for Mr. James’s pipe. The gentlemen who fell under the spell of Lola’s fascinations at this stage of her career were three in number—a Spaniard called Enriquez, an Englishman, simply described as John, and the skipper himself. This “colossal sailor” seems to have been somewhat of a philosopher. One of his profound reflections has been handed down to us, and is worth recording: “Love is a pipe we fill at eighteen, and smoke till forty; and we rake the ashes till our exit.”

Lola thus pictures as a man-enslaving Circe the girl who was described by a contemporary as a good little thing, merry and unaffected. I doubt if the flirtations here magnified into intrigues were very serious affairs, after all. It is rather pathetic, the woman’s shame for the simplicity of the girl, and her evident desire to paint her redder than she was. It is probable that the girl would have been quite as much ashamed if she could have seen herself at thirty.

INDIA SEVENTY YEARS AGO

The land to which little Mrs. James was eager to return seems to us now to have been a poor exchange for the rollicking Ireland of Lever’s day. India in 1838, as for a score of years after, was under the rule of John Company. Collectors and writers of the Jos. Sedley type were still able to shake the pagoda tree, and Englishmen in outlying provinces often became suddenly rich, how or why nobody asked, and only the natives cared. Indigo planters beat their half-caste wives to death, and English magistrates looked the other way. Our people died, like flies in autumn, of cholera, snakebites, and the thousand and one fevers to which India was subject. We were still shut in by powerful native states. Ranjit Singh ruled in the Punjaub, the Baluchis in Scinde; there was yet a king in Oude and a rajah at Nagpûr. Slavery was only abolished in the British dominions that very year, and Hindoo widows had but lately lost the privilege of burning themselves on their husbands’ funeral pyres. The chronic famine had assumed slightly more serious proportions.

It was a land of loneliness, remote and isolated. A postal service had been introduced only the year before, and letters took at least three months to come from[Pg 22] England. This was by the overland route, which was liable at any moment to interruption by the caprice of the Pasha of Egypt or the enterprise of Bedouins. There were, of course, no railways and no telegraphs. You travelled wherever possible by river, in boats called budgerows, which had not increased in speed since Ensign Gilbert’s day. Going up the Ganges you might have seen the Danish flag waving over Serampore. If you were in a hurry and could afford it, you travelled dâk—that is, in a palanquin, carried by four bearers, who were changed at each stage like posting-horses. This method of travel—about the most uncomfortable, I conceive, ever devised by man—greatly impressed and interested Lola. She thought it repugnant to one’s sense of humanity, but could not help observing the lightheartedness of the bearers. They jogged briskly along to the accompaniment of improvised songs, which were not always flattering to their human load.

“I will give you a sample,” says our traveller, “as well as it could be made out, of what I heard them sing while carrying an English clergyman who could not have weighed less than two hundred and twenty-five pounds. Each line of the following jargon was sung in a different voice:—

“‘Oh, what a heavy bag!

No, it is an elephant;

He is an awful weight.

Let us throw his palki down,

Let us set him in the mud—

Let us leave him to his fate.

Ay, but he will beat us then

With a thick stick.

Then let’s make haste and get along,

Jump along quickly!’

[Pg 23]“And off they started in a jog-trot, which must have shaken every bone in his reverence’s body, keeping chorus all the time of ‘Jump along quickly,’ until they were obliged to stop for laughing.

“They invariably (continues Lola) suit these extempore chants to the weight and character of their burden. I remember to have been exceedingly amused one day at the merry chant of my human horses as they started off on the run.

“‘She’s not heavy,

Cabbada [take care]!

Little baba [missie],

Cabbada!

Carry her swiftly,

Cabbada!

Pretty baba,

Cabbada!’

“And so they went on, singing and extemporising for the whole hour and a half’s journey. It is quite a common custom to give them four annas (or English sixpence) apiece at the end of every stage, when fresh horses [sic] are put under the burden; but a gentleman of my acquaintance, who had been carried too slowly, as he thought, only gave them two annas apiece. The consequence was that during the next stage the men not only went faster, but they made him laugh with their characteristic song, the whole burden of which was: ‘He has only given them two annas, because they went slowly; let us make haste, and get along quickly, and then we shall get eight annas, and have a good supper.’”

The burden of the European’s life in India at this period is voiced in “Marois’” poem, The Long, Long,[Pg 24] Indian Day. It was the empire of ennui. A strongly puritanical tone, too, was observable in certain influential circles, and the clergy frequently discountenanced and condemned the poor efforts at relaxation made by officers and their wives. Dances and amateur theatricals were often the subject of censure from the pulpit. So the men fell back on brandy pawnee, loo, and tiger-shooting. The women were worse off. To the Honourable Emily Eden we are indebted for some vivid pictures of Anglo-Indian society during the viceroyalty of her brother, Lord Auckland (1836-1842). They enable us to realise Lola’s emotions and manner of life during her second visit to India. Miss Eden’s compassionate interest was excited by

“a number of young ladies just come out by the last ships, looking so fresh and English, and longing to amuse themselves—and it must be such a bore at that age to be shut up for twenty-three hours out of the twenty-four; and the one hour that they are out is only an airing just where the roads are watered. They have no gardens, no villages, no poor people, no schools, no poultry to look after—none of the occupations of young people. Very few of them are at ease with their parents; and, in short, it is a melancholy sight to see a new young arrival.”

Another passage runs:—

“It is a melancholy country for wives at the best, and I strongly advise you never to let young girls marry an East Indian. There was a pretty Mrs. —— dining here yesterday, quite a child in looks, who married just before the Repulse sailed, and landed here about ten days ago. She goes on next week to Neemuch, a place at the farthest extremity of India, where there[Pg 25] is not another European woman, and great part of the road to it is through jungle, which is only passable occasionally from its unwholesomeness. She detests what she has seen of India, and evidently begins to think ‘papa and mamma’ were right in withholding for a year their consent to her marriage. I think she wishes they had held out another month. There is another, Mrs. ——, who is only fifteen, who married when we were at the Cape, ... and went straight on to her husband’s station, where for five months she had never seen a European. He was out surveying all day, and they lived in a tent. She has utterly lost her health and spirits, and though they have come down here for three weeks’ furlough, she has never been able even to call here [at Government House]. He came to make her excuse, and said, with a deep sigh: ‘Poor girl! she must go back to her solitude. She hoped she could have gone out a little in Calcutta, to give her something to think of.’ And then, if these poor women have children, they must send them away just as they become amusing. It is an abominable place.”

This was not realised at once by Mrs. James, whose first season (she tells us) was passed “in the gay and fashionable city of Calcutta.” There she became an acknowledged beauty. Not long after the outbreak of the first Afghan War she was torn away from the comparative brilliance of the capital, and accompanied her husband most reluctantly, to Karnál, a town between Delhi and Simla, on the Jumna Canal. The place is no longer a military station. At this juncture, happily for us, a flood of light is poured upon Lola’s character and history by the letters of Miss Eden, dated from Simla and Karnál in the latter part of the year 1839. I include some extracts not directly relating to Lola, as they describe scenes in which she must have taken[Pg 26] part, and which formed the background against which she moved.

“Sunday, 8th September [1839].

“Simla is much moved just now by the arrival of a Mrs. J[ames], who has been talked of as a great beauty of the year, and that drives every other woman, with any pretensions in that line, quite distracted, with the exception of Mrs. N., who, I must say, makes no fuss about her own beauty, nor objects to it in other people. Mrs. J[ames] is the daughter of a Mrs. C[raigie], who is still very handsome herself, and whose husband is Deputy-Adjutant-General, or some military authority of that kind. She sent this only child to be educated at home, and went home herself two years ago to see her. On the same ship was Mr. J., a poor ensign, going home on sick leave. Mrs. C. nursed him and took care of him, and took him to see her daughter, who was a girl of fifteen [sic] at school. He told her he was engaged to be married, consulted her about his prospects, and in the meantime privately married this girl at school. It was enough to provoke any mother, but as it now cannot be helped, we have all been trying to persuade her for the last year to make it up, as she frets dreadfully about her only child. She has withstood it till now, but at last consented to ask them for a month, and they arrived three days ago. The rush on the road was remarkable, and one or two of the ladies were looking absolutely nervous. But nothing could be more unsatisfactory than the result, for Mrs. James looked lovely, and Mrs. Craigie had set up for her a very grand jonpaun [kind of sedan-chair], with bearers in fine orange and brown liveries, and the same for herself; and James is a sort of smart-looking man, with bright waistcoats and bright teeth, with a showy horse, and he rode along in an attitude of respectful attention to ma belle mère. Altogether it was an imposing sight, and I cannot see any way out of it[Pg 27] but magnanimous admiration. They all called yesterday when I was at the waterfalls, and F[anny] thought her very pretty.”

“Tuesday, 10th September.

“We had a dinner yesterday. Mrs. James is undoubtedly very pretty, and such a merry, unaffected girl. She is only seventeen now [twenty-one, in fact], and does not look so old, and when one thinks that she is married to a junior lieutenant in the Indian army fifteen years older than herself, and that they have 160 rupees a month, and are to pass their whole lives in India, I do not wonder at Mrs. Craigie’s resentment at her having run away from school.

“There are seventeen more officers come up to Simla on leave for a month, partly in the hope of a little gaiety at the end of the rains; and then the fancy fair has had a great reputation since last year, and as they will all spend money, they are particularly welcome....

“Wednesday, 11th September.

“We had a large party last night, the largest we have had in Simla, and it would have been a pretty ball anywhere, there were so many pretty people. The retired wives, now that their husbands are on the march back from Cabul, ventured out, and got through one evening without any prejudice to their characters.”

Are regimental ladies in India nowadays expected to keep in seclusion while their husbands are on active service? I think not.

“Monday, 16th September.

“We are going to a ball to-night, which the married gentlemen give us; and instead of being at the only public room, which is a broken, tumble-down place, it is to be at the C.’s [the Craigies’?], who very good-naturedly give up their house for it.”

“Wednesday, 18th September.

“The ball went off with the greatest success: transparencies of the taking of Ghaznee, ‘Auckland’ in all directions, arches and verandahs made up of flowers; a whist table for his lordship, which is always a great relief at these balls; and every individual at Simla was there. There was a supper room for us, made up of velvet and gold hangings belonging to the Durbar, and a standing supper all night for the company in general, at which one very fat lady was detected in eating five suppers.... It was kept up till five, and altogether succeeded.”

“Friday, 27th September.

“We had our fancy fair on Wednesday, which went off with great éclat, and was really a very amusing day, and, moreover, produced 6,500 rupees, which, for a very small society, is an immense sum. X. and L. and a Captain C. were disguised as gipsies, and the most villainous-looking set possible; and they came on to the fair, and sang an excellent song about our poor old Colonel and a little hill fort that he has been taking; but after the siege was over, he found no enemy in it, otherwise, it was a gallant action.

“We had provided luncheon at a large booth with the sign of the ‘Marquess of Granby.’ L. E. was old Weller, and so disguised I could not guess him; X. was Sam Weller; K., Jingle; and Captain C., Mrs. Weller; Captain Z., merely a waiter, with one or two other gentlemen; but they all acted very well up to their characters, and the luncheon was very good fun.... The afternoon ended with races—a regular racing-stand, and a very tolerable course for the hills; all the gentlemen in satin jackets and jockey caps, and a weighing stand—in short, everything got up regularly. Everybody likes these out-of-door amusements at this time of year, and it is a marvel to me how well X. and K. and L. E. contrive to make all their plots and[Pg 29] disguises go on. I suppose in a very small society it is easier than it would be in England, and they have all the assistance of servants to any amount, who do all they are told, and merely think the ‘sahib log’ are mad.”

“Tuesday, 15th October.

“The Sikhs are here. Our ball for them last night went off very well. The chiefs were in splendid gold dresses, and certainly very gentleman-like men. They sat bolt upright on their chairs, with their feet dangling, and I dare say suffered agonies from cramp. C. said we saw them amazingly divided between the necessity of listening to George [Lord Auckland], and their native feelings of not seeming surprised, and their curiosity at men and women dancing together. I think that they learned at least two figures of the quadrilles by heart, for I saw Gholâb Singh, the commander of the Goorcherras, who has been with Europeans before, expounding the dancing to the others.”

Lola’s month at Simla had now expired, but she probably postponed her departure to witness the reception of these chiefs. Having been reconciled with her mother—partly, it seems, through the kindly intervention of the Governor-General’s sister, and partly, as she afterwards declared, through her stepfather—she returned with her husband to his cantonment. Here she was fortunate again to attract the attention of the viceregal party.

Miss Eden writes from Karnál, under date 13th November 1839:—

“We had the same display of troops on arriving, except that a bright yellow General N. has taken his[Pg 30] liver complaint home, and a pale primrose General D., who has been renovating some years at Bath, has come out to take his place. We were at home in the evening, and it was an immense party, but except that pretty Mrs. James who was at Simla, and who looked like a star among the others, the women were all plain.

“I don’t wonder if a tolerable-looking girl comes up the country that she is persecuted with proposals.... That Mrs. —— we always called the little corpse is still at Karnál. She came and sat herself down by me, upon which Mr. K., with great presence of mind, offered me his arm, and said to George that he was taking me away from that corpse. ‘You are quite right,’ said George. ‘It would be very dangerous sitting on the same sofa; we don’t know what she died of.’”

“Sunday, 17th November.

“We left Karnál yesterday morning. Little Mrs. James was so unhappy at our going that we asked her to come and pass the day here, and brought her with us. She went from tent to tent, and chattered all day, and visited her friend Mrs. ——, who is with the camp. I gave her a pink silk gown, and it was altogether a very happy day for her evidently. It ended in her going back to Karnál on my elephant, with E. N. by her side and Mr. James sitting behind, and she had never been on an elephant before, and thought it delightful. She is very pretty, and a good little thing, apparently, but they are very poor, and she is very young and lively, and if she falls into bad hands she would soon laugh herself into foolish scrapes. At present the husband and wife are very fond of each other, but a girl who marries at fifteen hardly knows what she likes.”

RIVEN BONDS

Miss Eden’s misgivings were warranted by the events. “Husband and wife are very fond of each other”—that was, doubtless, true, but Lola’s lips would have curled had she read the passage in after years. Abandoned by the departure of the viceregal party once more to the slender social resources of Karnál, the young wife, I conjecture, fretted and moped. The glitter of the Court made the boredom of the cantonment all the more oppressive. The year after the Simla festivities Karnál had another distinguished visitor, the famous Dost Mohammed Khan, Amir of Kabul, but as during his six months’ stay he was kept a close prisoner in the fort, his presence could not have sensibly relieved the monotony. Lieutenant James’s subsequent readiness to divorce his wife proves that he had no very strong attachment to her, and gives some colour to her allegations against him. Of course, it is safe to conclude that both were in the wrong, or, more truthfully, had made a mistake. So long, however, as people regard marriage more as a contract than a relation, each party will be anxious to throw the responsibility for the rupture upon the other. As the husband had the opportunity of stating his case in the law courts, it is only fair that[Pg 32] the wife should be allowed to plead hers here. Her version of the circumstances which brought about the breach is as follows:—

“She was taken to visit a Mrs. Lomer—a pretty woman, who was about thirty-three years of age, and was a great admirer of Captain [sic] James. [His bright waistcoats and bright teeth were not without their effect, we see.] Her husband was a blind fool enough; and though Captain James’s little wife, Lola, was not quite a fool, it is likely enough that she did not care enough about him to keep a look-out upon what was going on between himself and Mrs. Lomer. So she used to be peacefully sleeping every morning when the Captain [read Lieutenant] and Mrs. Lomer were off for a sociable ride on horseback. In this way things went on for a long time, when one morning Captain James and Mrs. Lomer did not get back to breakfast, and so the little Mrs. James and Mr. Lomer breakfasted alone, wondering what had become of the morning riders.

“But all doubts were soon cleared up by the fact fully coming to light that they had really eloped to Neilghery Hills. Poor Lomer stormed, and raved, and tore himself to pieces, not having the courage to attack any one else. And little Lola wondered, cried a little, and laughed a good deal, especially at Lomer’s rage.”

The injured husband, apparently, was never pieced together again, as we do not hear that he ever instituted any proceedings against the seducer of his wife. It is true that by Lola’s account they may be considered to have put themselves beyond his reach, for the Neilghery Hills lie, as the crow flies, about 1,400 miles from Karnál, and a stern chase in a palanquin over that distance is an undertaking from which even Menelaus[Pg 33] would have shrank. Nor did the peccant Lieutenant James think it worth while to resign his commission.

Whatever may have been the immediate cause, it is clear that husband and wife were on bad terms when the cantonment at Karnál was broken up in the year 1841. Lola took refuge under her mother’s roof at Calcutta. She admits that her reception was cold, and that Mrs. Craigie pressed her to return to Europe. On this course she finally decided, probably without great reluctance. It was given out, and not perhaps altogether untruly, that she was leaving India for the benefit of her health. Her husband came down to Calcutta, and himself saw her aboard the good ship, Larkins. Her stepfather, to whose relations in Scotland she was again to be confided, was much affected at her departure.

“Large tears rolled down his cheeks when he took her on board the vessel; and he testified his affection and his care by placing in the hands of the little grass-widow a cheque for a thousand pounds on a house in London.”

Thus for the second and last time Lola saw the swampy shores of Bengal receding from her across the waves. She was never again to see India or those who bid her adieu. The merry, unaffected schoolgirl of Simla had become in one short year a disappointed, disillusioned woman. While husband and wife exchanged cold farewells, probably neither expected nor wished to see the other again. Both had made a mistake, and both knew it. Now they were placing half a world between them. Lola’s heart must have lightened, as the good ship sped before the wind [Pg 34]southwards across the Indian Ocean. Accustomed to shipboard, the désagréments of the voyage were nothing to her, and she immediately began to take an interest in her companions. She speaks of a Mr. and Mrs. Sturges, Boston people, who were nominally in charge of her; and of a Mrs. Stevens, another American lady, a very gay woman, who had some influence in supporting her determination not to go to the Craigies’ on reaching England. There was a Mr. Lennox on board, sometimes described as an aide-de-camp to some governor, who also may have had something to do with this resolution. It all came about as Lord Auckland’s sister had feared. Lola had fallen into evil hands, and laughed herself into a bad scrape. She had been accustomed to admiration; she was young, beautiful, and passionate. Her heart was empty; she was angered against her husband. She was by no means unwilling to face the possibility of a final separation from him. Lennox remains for us the shadowiest of personalities, but his disappearance, implying abandonment of the woman he had compromised, tells against him. In this instance I think we may safely conclude that the man was to blame.

Out of affection for him, then, or a determination to lead her own life, uncontrolled and unshackled, Mrs. James, on arriving in London, flatly refused to accompany Mr. David Craigie, “a blue Scotch Calvinist,” whom she found awaiting her.

“At first he used arguments and persuasion, and finding that these failed, he tried force; and then, of course, there was an explosion, which soon settled the matter, and convinced Mr. David Craigie that he might go back to the little dull town of Perth as soon as he pleased, without the little grass-widow. Now[Pg 35] she was left in London, sole mistress of her own fate. She had, besides the cheque given her by her stepfather, between five and six thousand dollars’ worth of various kinds of jewellery, making her capital, all counted, about ten thousand dollars—a very considerable portion of which disappeared in less than one year by a sort of insensible perspiration, which is a disease very common to the purses of ladies who have never been taught the value of money.”

It was in the early spring of 1842 that Lola set foot in London. Considering the rapidity for those times with which her husband became informed of her next movements, these must have been amazingly open; and it is hard to resist the conclusion that she was deliberately trying to bring about a divorce. She knew that the English law grants no relief to those who come to it both with clean hands. She knew also that so long as her husband neither starved nor beat her, she could not set the law in motion against him. English law, supposed to vindicate the sanctity of marriage, sets a premium on adultery and cruelty: these are the only avenues of escape from unhappy unions into which high-minded men and women may have been betrayed by youthful folly, by over-persuasion, by sentiments they innocently over-estimated. If Lola Gilbert at the age of eighteen had signed a bill for ten pounds, the courts would have annulled the transaction, on the ground that her youth rendered her incapable of appreciating its gravity. As it was, she had signed away her life—a less important thing than property—and our Rhadamanthine law sternly held her to her bargain.

James was not slow to avail himself of the pretext she afforded him. He instituted through his proctors[Pg 36] a suit against her for divorce in the Consistory Court of London, to which jurisdiction in all matrimonial causes at that time belonged. Lola, as he probably expected she would do, ignored the proceedings from first to last. The case was heard before Dr. Lushington on 15th December 1842. Mrs. James was accused of misconduct with Mr. Lennox on board the ship Larkins, and of subsequently cohabiting with him at the Imperial Hotel, Covent Garden, and in lodgings in St. James’s. The court was satisfied with the proofs adduced, and pronounced a divorce a mensâ et toro. In modern legal language this was a judicial separation. These two people, though they were to live apart, were sentenced never to marry again during the lifetime of each other. It is by such dispositions that the law of England proposes to promote morality and the interests of society.

Both lover and husband disappear from the scene. James rose to the rank of captain, retired from the Indian army in 1856, and died in 1871. He never crossed Lola’s path again, and she ever afterwards referred to him with contempt and bitterness. If it was in any vindictive spirit that he divorced her, he would have done well to remember how in former years he had taken advantage of her youth and inexperience. It was a squalid ending to the romantic runaway match. It would be interesting to know with what emotions Captain James heard of his ex-wife’s adventures in high places in the years that followed. It must have seemed odd that monarchs should risk their crowns for the charms that he so lightly prized. Perhaps his wonder was not untinged with regret. More likely it might have been written of him as of Lola:—

[Pg 37]

“Who have loved and ceased to love, forget

That ever they lived in their lives, they say—

Only remember the fever and fret,

And the pain of love that was all his pay.”

Mrs. Craigie put on mourning as though her child was dead, and sent out to her friends the customary notifications. The good old Deputy-Adjutant-General alone thought kindly of Lola.

LONDON IN THE ’FORTIES

To a woman in Lola’s situation, London in the early ’forties offered every inducement to go to the devil. Between a roaring maelstrom of the coarsest libertinism, on the one hand, and an impregnable barrier of heartless puritanism on the other, her destruction was well-nigh inevitable. The hotchpotch of unorganised humanity that we call Society seldom presented an uglier appearance than it did in the first decade of Victoria’s reign. Sir Mulberry Hawk and Pecksniff are types of the two contending forces. Blackguardism was matched against snivelling cant. Luckily, the victory fell to neither. Those were the days of Crockfords, of Vauxhall, of the spunging-house, of public executions turned into popular festivals; when gentlemen of fashion painted policemen pea-green, and beat them till they were senseless; when peers got drunk and the people starved. Opposed to this debauchery was a religion of convention and propriety, narrow, stupid, and un-Christlike—the cult of the correct and the respectable, the fetishes to which Lady Flora Hastings and many another woman were coldly sacrificed.

In spite of Sir Mulberry and Mr. Pecksniff, however, Lola, ex-Mrs. James, had no intention of going under.[Pg 40] Her exclusion from society, after her wearisome experiences in India, she probably regarded as no great hardship. Her youth, her sprightliness, and her beauty made her many friends. Some of these as quickly became enemies, when they discovered that a divorced woman is not necessarily for sale. More than one roué vowed vengeance against the girl who, with bursts of laughter and dangerous gusts of anger, rejected the offer of his protection. It was, perhaps, in this way she offended the elegant Lord Ranelagh, who was then swaggering about in the Spanish cloak he had worn in the Carlist Wars. Lola was strong enough to swim in the maelstrom. Independence and adversity brought out the latent force in the character of the “good little thing” of Simla. Instead of looking out for a refuge, she sought a career.

She turned, of course, towards the stage, the one profession in Early Victorian times that offered any promise to an ambitious woman. She took more pains to acquire a knowledge of her art than are deemed necessary by most beautiful aspirants nowadays. She studied under Miss Fanny Kelly, a gifted actress, who had distinguished herself by her efforts to improve the social status of her profession, and who had opened a dramatic school for women adjacent to what is now the Royalty Theatre. Lola describes Miss Kelly as a lady as worthy in the acts of her private life as she was gifted in genius. This opinion was shared by all the contemporaries of the venerable actress. In after years Mr. Gladstone thought fit to recognise her services to the theatre by a royal grant of one hundred and fifty pounds, but the money arrived in time only to be expended on a memorial over her grave in the dismal[Pg 41] cemetery at Brompton. Since Lola was a friend of Miss Kelly, she must have been very far from being the depraved character she is represented by some.

With all the goodwill in the world, the experienced mistress could not make an actress of her beautiful pupil, who accordingly determined to approach the stage through a back-door. If talent of the intellectual order was denied her, she could fall back on her physical advantages. She determined to become a dancer. She was instructed for four months by a Spanish professor, and then (so she assures us) underwent a further training at Madrid. It was now that she assumed the name of Lola Montez—so soon to be known throughout Europe. She passed herself off as a Spaniard, partly, no doubt, for professional reasons, and partly to conceal her identity with the wife of Captain James. Society can hardly expect its quarry to step out into the open to be shot at. Her beauty and her dancing so impressed Benjamin Lumley, the experienced director of Her Majesty’s Theatre, that it was on his stage that she actually made her first appearance.

The morning papers of Saturday, 3rd June 1843, announced accordingly that between the acts of the opera (Il Barbiere di Seviglia), Donna [sic] Lola Montez, of the Teatro Real, Seville, would make her first appearance in this country, in the original Spanish dance, “El Olano.” Attracted by this advertisement, a critic, who afterwards wrote under the pseudonym of “Q.,” called at the theatre, and was presented to the débutante. In her he recognised a lady living opposite his lodgings in Grafton Street, Mayfair, who had long been the object of his silent adoration. He dwells on her extreme vivacity, on her brilliancy of conversation, and on her[Pg 42] foreign accent, which struck him as assumed. She was persuaded to give a rehearsal for his special benefit.

“At that period,” he goes on to say, “her figure was even more attractive than her face, lovely as the latter was. Lithe and graceful as a young fawn, every movement that she made seemed instinct with melody as she prepared to commence the dance. Her dark eyes were blazing and flashing with excitement, for she felt that I was willing to admire her. In her pose, grace seemed involuntarily to preside over her limbs and dispose their attitude. Her foot and ankle were almost faultless. Nadaud, the violinist, drew the bow across his instrument, and she began to dance. No one who has seen her will quarrel with me for saying that she was not, and is not, a finished danseuse, but all who have will as certainly agree with me that she possesses every element which could be required, with careful study in her youth, to make her eminent in her then vocation. As she swept round the stage, her slender waist swayed to the music, and her graceful neck and head bent with it, like a flower that bends with the impulse given to its stem by the changing and fitful temper of the wind.”[3]

On that eventful June evening, then, manager, critics, not least of all Lola herself, confidently looked forward to a striking success. The house was crowded, and many notabilities were present. There were the King of Hanover, the Queen-Dowager, the Duchess of Kent, and the Duke and Duchess of Cambridge. There was also Lola’s old enemy, my Lord Ranelagh, who with a party of friends occupied one of the two omnibus-boxes—an admirable point from which to examine the ankles and calves of the long-skirted ballet-girls. When the[Pg 43] curtain rose in the entr’acte, a Moorish chamber was revealed. On either side stood a damsel, gazing expectantly towards the draped entrance at the back of the stage. A moment later and there glided through this a figure enveloped in a mantilla. One of the handmaids snatched away this drapery, and the commanding form of Donna Lola Montez was revealed in all its glory.

“And a lovely picture it is to contemplate! There is before you the perfection of Spanish beauty—the tall, handsome person, the full, lustrous eye, the joyous, animated face, and the intensely raven hair. She is dressed, too, in the brightest of colours: the petticoat is dappled with flaunting tints of red, yellow, and violet, and its showy diversities of hue are enforced by the black velvet bodice above, which confines the bust with an unscrupulous pinch. Presently this Andalusian Papagena lifts her arms, and the sharp, merry crack of the castanets is heard. She has commenced one of the merry dances of her nation, and many a piquant grace does she unfold.”[4]

The audience are bewitched, enraptured. The stage is strewn with bouquets. Suddenly from the right omnibus-box comes the surprised exclamation: “Why, it’s Betty James!” Lord Ranelagh has recognised the woman who rebuffed him, and hurriedly whispers to his friends. Above the applause from stalls and gallery, there is heard on the stage, at least, a prolonged and ominous hiss. My lord’s friends in the opposite box act upon the hint, and the hissing grows louder and more insistent. The body of the audience, knowing nothing about the matter, conclude that the dancer cannot know[Pg 44] her business, and presently begin to hiss, too. In ten minutes more the curtain comes down upon her, and Lola’s career as a dancer is terminated in England.

Lord Ranelagh had had his revenge. This species of blackguardism was only too common in those days. The notorious Duke of Brunswick that same year had gone with his attorney, Mr. Vallance, and a party of friends, to Covent Garden Theatre, for the express purpose of hooting down an actor, Gregory, who took the part of Faust. He succeeded in his design, and bragged about it afterwards. In Early Victorian times the theatre was completely under the thumb of certain aristocratic sets. The exasperated Lumley was powerless to resist the fiat of these gilded snobs. Lola Montez, they insisted, must never appear on his stage again. He obeyed. The Press was very far from imitating his subserviency. The Era and Morning Herald praised the new danseuse in what seem to us extravagant terms, and deliberately ignored the inglorious dénouement of her performance. Indeed, but for the pen of “Q.” we might be left to share the surprise expressed at her disappearance by the Illustrated London News, which, ironically perhaps, suggested that the votaries of what might be called the classical dance had set their faces against the national.

Lola herself was under no misapprehension as to the cause and authors of her defeat. She wrote to the Era on 13th June, protesting passionately against a report that was being circulated to the effect that she had long been known in London as a disreputable character. She positively asserted that she was a native of Seville, and had never before been in London. She complains of the cruel calumnies that had got[Pg 45] abroad concerning her, and says that she has instructed her lawyer to prosecute their utterers. Of course, the greater part of this statement was untrue, but she had her back against the wall, and with their reputation, social and professional, and means of livelihood at stake, few women would have acted otherwise. My own view is that after her affair with Lennox, Lola tried hard “to keep straight,” and made powerful enemies in consequence. The alliance of Pecksniff and Sir Mulberry proved too strong for her.

WANDERJAHRE

London, then, was closed to Lola. She was recognised, and for the divorced wife of Lieutenant James there were no prospects of a career. Her defeat determined her to aim higher, not lower, as most women would have done. In the English country towns she would have been quite unknown, and might have earned a modest competence. But her experience of Montrose and Meath did not predispose her towards the provincial atmosphere. Devoting England and its serpent seed to the infernal gods, she took wing to Brussels. So rapidly were her preparations made that when “Q.” called the very morning after the “frost” at Her Majesty’s at her apartments in Grafton Street, he found her gone—none knew whither. We must feel sorry for our anonymous friend, for it is evident from his confessions that Lola’s blue eyes had bored a big hole in his heart. He consoled himself for her loss by writing (I suspect) some of the flattering notices on her performance to which reference has been made.

It is impossible to trace his enchantress’s movements in their proper sequence during the next nine or ten months (June 1843 to March 1844). We find her at Brussels, Berlin, Dresden, Warsaw, and St. Petersburg.[Pg 48] She reached the Belgian capital practically with an empty purse. She afterwards said[5] that she went there partly because she had not enough money wherewith to go to Paris, partly because she hoped to make her way on to The Hague. She proposed to lay siege to the heart of his Dutch Majesty William II., then a man fifty-one years of age. She had, quite probably, met his son, the Prince of Orange, who was visiting Lord Auckland about the time she was at Simla, and had heard tales in Calcutta about the Dutch Court. The House of Orange has not been fortunate in its domestic relations. It is said that during the last king’s first experience of wedlock, the heads of chamberlains often intercepted the books aimed by the Royal spouses at each other, while the whole palace re-echoed with the slamming of doors and the crash of crockery. William II., though not possessed of the reputation of his son and grandson, the celebrated “Citron,” was known to be on bad terms with his Russian wife, Anna Pavlovna. He seemed to Lola a promising subject for the exercise of her powers of fascination. The design, if she ever really entertained it, was not one that moralists could applaud, but in extenuation it must be urged that Lola’s late defeat could not have encouraged her to persevere in the path of virtue. However, the Dutch project came to nothing, and the display of our heroine’s statecraft was reserved for another capital and another day.

In Brussels she found herself friendless and penniless. She was reduced to singing in the streets to save herself from starvation—she who only four years before had been borne from the stately Indian Court enthroned on[Pg 49] the Viceroy’s elephant! Her distress is rather to the credit of her reputation, for it would have been easy enough for so beautiful a woman to have found a wealthy protector in the Belgian capital. She was noticed by a man, whom she believed to be a German, who took her with him to Warsaw. “He spoke many languages,” says Lola, “but he was not very well off himself. However, he was very kind, and when we got to Warsaw, managed to get me an engagement at the Opera.”[6] I cannot help wishing that Lola had given us some account of a journey that must have been performed in a carriage right across Central Europe from Belgium to Poland.

Warsaw in 1844 must have been as cheerless a spot as any in Europe. The great insurrection of 1831 had been suppressed with ruthless severity by the soldiers of the Tsar, and there was not a family of rank in the city that was not mourning for some one of its members who had passed beyond the ken of its living, into dread Siberia. Order reigned at Warsaw, indeed, in its conqueror’s famous phrase, but it was order obtained only with the knout and the bayonet. The Polish language was barely tolerated, the Catholic religion proscribed. Women, half-naked, were publicly flogged for their attachment to their faith, school-boys and school-girls sent to perish beyond the Urals. The secret service ramified through every grade of society. Fathers distrusted their sons, husbands feared to discover in their own wives the tools of the Muscovite Government. To this day Poles are seldom free from the nightmare of the Russian spy. The present writer remembers how, some years ago, at Bern, in the capital of[Pg 50] a free republic, a Polish medical man refused, with every symptom of apprehension, to discuss the condition of his country within the longest ear-shot of a third party.

Yet unhappy Warsaw, under the heel of the terrible Paskievich, could be coaxed into a smile by the flashing eyes of the new Andalusian dancer. Her beauty enraptured the Poles, and drew from one of their dramatic critics the following elaborate panegyric:—