The Project Gutenberg EBook of A Terrible Tomboy, by Angela Brazil This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net Title: A Terrible Tomboy Author: Angela Brazil Illustrator: N. Tenison Release Date: January 20, 2012 [EBook #38619] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK A TERRIBLE TOMBOY *** Produced by Suzanne Shell and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

STORIES FOR GIRLS

Illustrated in Colour.

THE STORY-BOOK GIRLS. By Christina G. Whyte. 6/- and 3/6.

NINA'S CAREER. By Christina G. Whyte. 6/-.

BRIDGET OF ALL WORK. By Winifred M. Letts. 5/-.

MISTRESS NANCIEBEL. By Elsie J. Oxenham. 5/-.

A GIRL OF THE NORTHLAND. By Bessie Marchant. 5/-.

THE GIRL CRUSOES. By Mrs. Herbert Strang. 3/6 and 2/6.

THE GIRL SCOUT. By Brenda Girvin. 3/6.

DAUNTLESS PATTY. By E. L. Haverfield. 3/6 and 2/6.

THE CONQUEST OF CLAUDIA. By E. L. Haverfield. 3/6.

HENRY FROWDE and HODDER & STOUGHTON

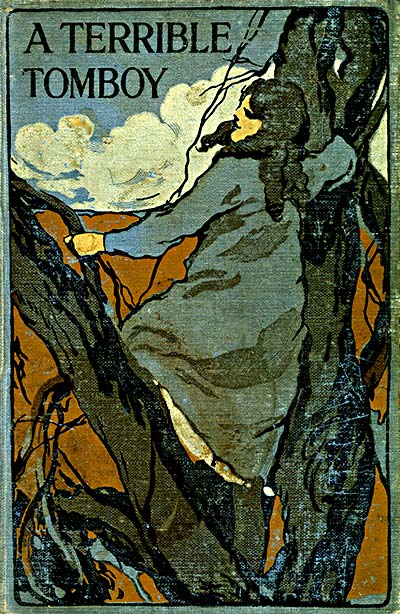

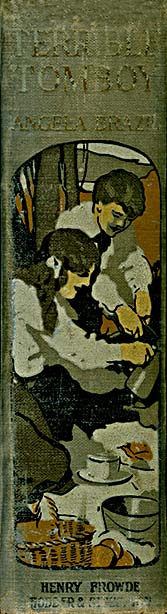

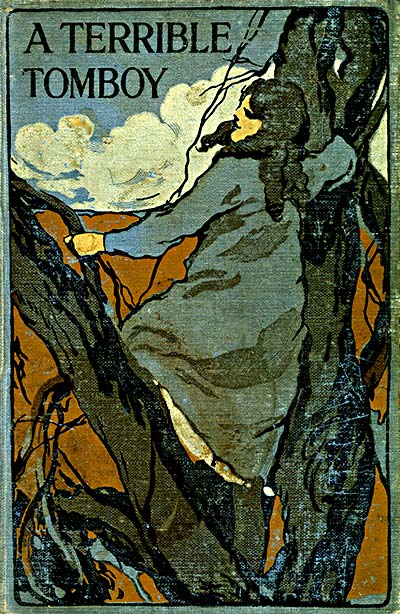

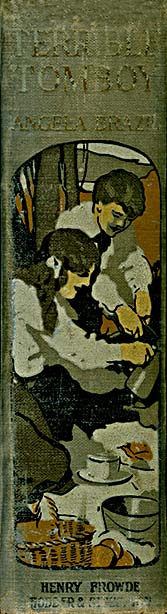

A

TERRIBLE TOMBOY

BY

AUTHOR OF "FAIRY PLAYS FOR CHILDREN"

NEW EDITION

ILLUSTRATED IN COLOUR BY N. TENISON

LONDON

HENRY FROWDE

HODDER AND STOUGHTON

1915

| CHAP. | PAGE | |

|---|---|---|

| I. | PEGGY AT HOME | 1 |

| II. | BIRDS'-NESTING | 12 |

| III. | THE BLACK PUPPY | 25 |

| IV. | A STORMY DAY | 35 |

| V. | CONCERNING LILIAN | 51 |

| VI. | SUNDAY | 62 |

| VII. | MAUD MIDDLETON'S PARTY | 72 |

| VIII. | THE HOLIDAYS | 85 |

| IX. | A MOUNTAIN WALK | 97 |

| X. | ON THE MOORS | 109 |

| XI. | A NEW FRIEND | 121 |

| XII. | IN THE RECTORY GARDEN | 132 |

| XIII. | THE SMUGGLERS' CAVE | 140 |

| XIV. | LILIAN'S HOUSEKEEPING | 157 |

| XV. | THE BEGINNING OF A SHADOW | 170 |

| XVI. | ARCHIE | 180 |

| XVII. | DAME ELEANOR'S GHOST | 193 |

| XVIII. | PLAY-ACTING | 207 |

| [vi]XIX. | PEGGY AT WAR | 219 |

| XX. | GORSWEN FAIR | 231 |

| XXI. | ROLLO'S GRAVE | 245 |

| XXII. | DEEPENING TROUBLE | 256 |

| XXIII. | THE ANTIQUARIAN SOCIETY | 268 |

| XXIV. | CONCLUSION | 280 |

| To face page | |

|---|---|

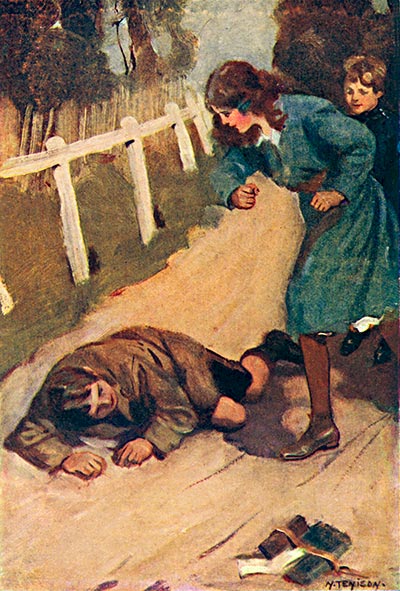

| "SEE, I'LL PUT IT JUST ON THE TOP IN FRONT"

(see page 44) |

|

| "MAKING A LONG ARM, SHE MANAGED TO SEIZE PUSS BY THE SCRUFF OF HER NECK" | 82 |

| "BOBBY ACCOMPLISHED THE CROSSING IN SAFETY" | 154 |

| "HE FIRST SET TO WORK TO MAKE A SPIRAL STAIRCASE UP THE TREE" | 182 |

| "IF YOU BREAK YOUR WORD, I'LL LET ALL WARFORD KNOW THAT YOU'VE BEEN KNOCKED DOWN AND THRASHED BY A GIRL" | 226 |

| "SEDGWICK, THIS IS AN EXTRAORDINARY DAY!" | 276 |

'Peggy! Peggy! where are you? Peggy! Aunt Helen wants you! Oh, Peggy, do be quick! Wherever are you hiding?'

Getting no response to her calls, the speaker, a pretty fair-haired girl of fifteen, flung her brown holland cooking-apron over her head, and ran out across the farmyard into the lightly-falling rain. She peeped into the cart-shed, where the hens were scratching about among the loose straw. Certainly Peggy was not there. She searched in the kitchen garden, but there was nothing to be seen except the daffodils nodding their innocent heads under the gooseberry-bushes. Round through the orchard she sped, bringing down a shower of cherry-blossom as she brushed against the low-growing trees, and greatly disturbing a robin, who was feeding a young family in a hole in the ivy, but without any sign of the truant. Here and there Lilian ran, hunting in all Peggy's favourite haunts—now peeping into a hollow yew-tree, now peering at the top of a ladder, now rummaging in the tool-shed, then[2] back through the sand-quarry into the stack-yard, where there was a very good chance that the young lady might be hidden away in some snug little hole among the hay; but though Lilian got a tolerable amount of hay-seed into her hair, her efforts were fruitless, and she was just turning away, hot and out of breath, to give up the useless search, when the sound of a low, chuckling laugh attracted her to the barn.

The door was slightly ajar, and she peeped in.

On the floor among the straw sat a little boy of between eight and nine years old, gazing with rapturous delight into the rafters of the roof. Following the direction of his eyes, Lilian glanced up, and beheld a sight which made her gasp with horror. The barn was a very large one, and was spanned by a great cross-beam, which ran across the whole length from one end to another. Mounted on this, fully fifteen feet above the ground, a small girl was slowly walking along, her gray eyes bright with excitement, her brown curls flying in wild disorder, and her arms stretched out on either side to balance herself as she went on her perilous journey.

Lilian gazed at her spellbound; she did not dare to speak or move, lest by some mischance the frail little figure should lose its nerve and come crashing down on to the stone floor below.

The child herself, however, did not seem to be troubled with the slightest fear, for she walked on as steadily as if the beam had been a plain turnpike road, giving a shout of triumph as she reached the cross-bar, and slid down the ladder on to the ground.

'Hurrah! hurrah!' cried Bobby, clapping his hands in an ecstasy of admiration.

Peggy turned round with a radiant face.

'It's perfectly easy!' she exclaimed; 'I could[3] do it over again. Now, Bobby, you come up and try!'

But here Lilian's pent-up excitement and wrath burst forth.

'For shame, Peggy!' she cried. 'If you want to break your own neck, you shan't break Bobby's, at any rate! Don't you know what a horribly dangerous thing you have been doing? And the idea of your walking along there with your boot-lace dangling down in that way! You are really getting too old for these silly tricks; one can't look after you like a baby. Aunt Helen would be angry if she heard of this!'

Peggy sat down on the bottom rung of the ladder. The triumph had faded from her face, and left something not nearly so pleasant to look at behind.

'All right,' she said defiantly; 'go along and tell Aunt Helen if you like! I don't care!'

'Peggy, how horrid you are! Do I ever tell? Didn't I wash and iron your pinafore yesterday, when you fell into the pig-trough, and nobody even suspected? I call you right-down mean to go saying things like that!' And Lilian's pretty face flushed quite pink with righteous indignation.

Peggy had the grace to look rather ashamed of herself.

'No, Lil, you're a dear; you don't tell tales,' she said; 'and I haven't forgotten about the pinafore.'

'Promise me, then, that you won't go playing such mad pranks again, and leading Bobby into them, too?'

'All right—anything for a quiet life.'

'But promise, properly.'

'There! On my honour, I will never walk along that beam again, or let Bobby do it either. Will that suit you?'

Lilian heaved a sigh of relief, for whatever might be[4] Peggy's sins and misdeeds, her word, once given, was not lightly broken.

'I've been looking for you everywhere,' she said. 'Aunt Helen sent me to fetch you in at once, and I've been such a long time in finding you. I'm afraid she'll be ever so cross.'

'What does she want me for?'

'To darn your stockings. Oh, Peggy, how could you go and hide all those pairs away under the dressing-table? It was really silly, for you might have known Aunt Helen would be sure to hunt them out; and now she's fearfully angry about it, and says you'll have to sit and mend away till they're all finished; and she won't let me help you, either.'

Peggy sighed philosophically.

'I suppose I shall have to come,' she said, getting up and shaking the straw out of her hair. 'Never mind; I'd really rather mend them all in one big heap than in a lot of little horrid pottering times; it spoils one's Saturdays so!'

'Aunt Helen said if I found Bobby he was to come in too, and learn his Latin,' continued Lilian, looking round. But that youth had prudently disappeared at the first hint of Saturday duties, and was nowhere to be seen.

Peggy chuckled.

'I'm afraid you won't find him,' she remarked; 'and it's no use looking. He's got the most lovely hiding-place in the world that he goes to when he doesn't want to be told to come in. I only found it out by accident myself, and I promised wild horses shouldn't wrench the secret from me. Come along; we may as well go and get the scolding over.'

And the young lady tossed back her tangled locks, shook her fist at the anticipated pile of[5] darning; then, putting on an air of chastened and becoming meekness, as being most likely to soothe Aunt Helen's wrath, she marched sturdily into the house.

It was a beautiful old home into which Peggy entered, half castle, half farmhouse, with an air of having seen better days about it. The quaint timbered house, with its carved gables and red-tiled roof, was built in at one end into a kind of square tower or keep, with tiny turret windows and winding staircase, getting just a little ruinous in places, but held firmly together by masses of ivy, which clung round it like a green mantle. Beyond the tower lay the remains of an abbey, more ancient than the keep. Most of it had been carried away to build the large barns and stables, but the foundations could still be plainly traced, with here and there part of a wall thickly covered with ivy, the ruins of a shattered column, a delicate little piece of window tracery, or a few steps of corkscrew staircase. There were rows and heaps of mossy stones covered with nettles and elder-bushes, with patches of green grass in between, where the cows grazed and the pigeons flew about, cooing gently. In the ivy the jackdaws were always busy, and the children had many a perilous climb trying to reach the coveted nests. The earliest primroses grew here, and beds of sweet violets under the ruined walls, and there were so many turns and corners and sheltered nooks that it made the grandest play-place in the world for anyone who loved a game at hide-and-seek.

On the other side of the house stretched the garden—such a sweet, old-fashioned garden, where roses, lilies, and gillyflowers were all mixed up with the currants and gooseberries and cabbages. It was somewhat neglected, it is true, but perhaps it looked none the[6] less picturesque for that, and certainly no one would be disposed to quarrel with the beautiful ripe strawberries and the sweet little yellow gooseberries with the hairy skins, or the big red plums that hung upon the old brick walls.

Inside the house was large and roomy, with rambling passages and odd little windows in unexpected corners. There was a large oak staircase, with wide, shallow steps, leading to a panelled gallery, where hung swords, and rusty armour, and moth-eaten tapestry, and many an ancient relic of the past; while in the best bedroom was a great carved four-post bed, hung with faded yellow curtains, where Queen Elizabeth herself was said to have slept in much state for two nights on her journey from Shrewsbury to Wrexham.

The big drawing-room had been shut up for many years; the Queen-Anne chairs and china-cabinets were swathed in wrappers, and the ornaments put away in boxes; but sometimes the children would steal in and open the shutters to look at the portraits which hung upon the oak-panelled walls—stately gentlemen with wigs and lace frills, whose eyes seemed to follow you about the room; haughty dames with powdered hair and patches; stiff little girls in hoops and mittens, and pretty young ladies attired as shepherdesses or classic goddesses, with cupids and nymphs in the background.

The little blue drawing-room, which was always used instead, was a far more cheery apartment, with its sunny French window and fresh muslin curtains, and the blue chintz covers on the chairs. But of all the rooms I think the quaintest was the kitchen. It was by far the oldest part of the house; the great beams of the roof, roughly hewn out with an axe and black with age, had been a portion of the ancient castle, and so had the mullioned windows, with their deep, old-fashioned[7] seats and diamond panes, filled with green, uneven glass. It looked a cheerful place, with its polished-oak dressers and shining brasses, and on a winter's evening, when the shutters were closed and the settle drawn close to the fire, it seemed the cosiest spot in the world; and Peggy and Bobby would often escape from the sober atmosphere of the dining-room to pull their little stools into the ingle nook, and listen to Nancy's wonderful tales of ghosts and goblins, which seemed twice as thrilling when the wind was howling like a banshee in the chimney, and rattling the doors till they could fancy that spirit fingers were tapping on the panels, and only waiting a chance to catch them in the dark passages, and sent such cold shivers running down their backs that they grew almost too frightened to go to bed.

Below the house the meadow sloped down to a river, where a stone bridge led to the village, with its pretty thatched cottages and Norman church, whose square tower stood up like a beacon for the surrounding country; and away in the distance, tier upon tier, rose the Welsh mountains, fading from green to purple or from purple to misty mauve, till the last were lost in the hazy blue of the sky.

Gorswen Abbey, as Peggy's home was called, had been an important place in its time, and an air of sleepy grandeur seemed still to hang about the old walls, as if sometime it might rouse itself from its lethargy and take its part in the world again.

No one could remember when Vaughans had not lived at the Abbey. There were tombs in memory of them in a side transept of the church—stalwart Crusaders, lying with legs crossed and meek hands folded in prayer; stout Elizabethan squires and their dames, with ruffs round their necks, and rows of prim little kneeling[8] children beneath them; full-faced Jacobean worthies in curled wigs, with sculptured cherubs weeping over extinguished torches; and there was a high old pew with a carved canopy over it, and an escutcheon bearing a coat of arms with a dragon on it, which, when Peggy was very little, she had always associated with the dragon in the Book of Revelation, and had an uneasy feeling that its eye was upon her all service time, and if she did not behave properly it might come down in great wrath and devour her.

There had been Vaughans who fought in the Wars of the Roses, Vaughans who threw in their lot with King Charles and helped to beat Cromwell at Atherton Moor, Vaughans who had joined the Young Pretender's force, and had lost their heads as their reward. There was no end to the stories which the children could sometimes cajole out of old David, the farm-help, who had all the family history at his finger-ends.

But they had been a happy-go-lucky, spendthrift race, loving to ride to hounds and to entertain liberally better than to look after their affairs. Little by little the fine property had been wasted away, till, when Peggy's father succeeded to the estate, he found it to consist of scarcely more than the old house with the surrounding farm and woodlands, together with such a multitude of debts, mortgages, and other encumbrances, that it was truly a barren heritage. Robert Vaughan, however, was a man of strong will and much determination. Some of the grit of the old Crusaders was left in his blood, and instead of taking his solicitor's advice, and selling the place for what it would fetch, he resolved to farm the land himself, and by using every care and economy to free the property, and raise it to its former level in the county. He worked in his own fields, ploughing, harvesting, and reaping, toiling harder[9] than any of his labourers, and living in as plain a manner as possible.

To those friends who thought he lost caste thereby he had always the same argument—that he saw no reason why the cultivation of fields should counteract the habits of refinement and good breeding to which he had been reared; that in the colonies educated gentlemen set to work to labour with their hands, and are thought none the worse of: so why not in England, where land is good and markets are plentiful, especially when it involved the keeping of a fine old property which had been in the family for so many hundreds of years?

Fortune, however, had been against him. Several bad seasons and a spell of disease among the cattle had made all the difference between profit and loss, and at the time this story begins Robert Vaughan realized that any unusual run of ill luck might bring matters to a crisis, and render vain the struggle of so many years. The children, however, knew little of the shadow which haunted their home, for they lived as yet in that happy thoughtless paradise which is the inheritance of true childhood, where a new rabbit in the hutch or an extra treat on a holiday is of far more importance than any grown-up affair.

Their mother had faded so early from their young lives that she was scarcely more than a tender memory, and her place had been taken by dear, pretty Aunt Helen, father's younger sister, who did her best to train them up in the way they should go. Aunt Helen fondly imagined herself to be a great disciplinarian, but her own lively youth was still such a recent remembrance that her eyes were wont to twinkle and the corners of her mouth to twitch in the middle of her severest scoldings, and the children always had a feeling[10] that so long as they did not do anything rude or wrong, or run into any very imminent danger, their escapades were secretly condoned by their aunt, who admired pluck and spirit, however much she might feel it incumbent upon her to lecture them.

Gentle Lilian gave little trouble, and Bobby, Aunt Helen often declared, would be easy enough to manage alone; but where Peggy led he was always sure to follow, and the end was generally mischief of some sort or other.

The worst of it was poor Peggy really did not mean to be naughty; she was so eager, so active, so full of overflowing and impetuous life, with such restless daring and abounding energy, that in the excitement of the moment her wild spirits were apt to carry her away, simply because she never stopped to think of consequences. She had always a hundred projects on hand, each one of which she was ready to pursue with unflagging zeal and that absorbing interest which is the secret of true enjoyment.

'Let her alone,' the Rector, who rejoiced in Peggy, was wont to say. 'Don't prune her too hard, for it is sometimes the side-shoots that bear the best flowers, after all. She is like a young growing plant—a little too much leaf at present, but I see a grand promise of blossom, and she'll turn out a fine woman in the end.'

Happily both her father and Aunt Helen shared his views, and, knowing Peggy's generous, affectionate nature, were able to lead her more by love than severity (for with human hearts it is often like the fable of the sun and the wind: they will respond to a kindly touch, while harshness will only make them sullen and obstinate), and they further held the opinion that it is better for a child to have many interests and much energy, even though these qualities prove a little[11] troublesome, than to grow up clipped to the prim pattern of those who may have outlived their enthusiasms.

Such natures as Peggy's taste life to the full; for them it is never a stale or worthless draught. Each moment is so keenly lived that time flies by on eager wings, and though there may be stormy troubles sometimes, as a rule the spirit dwells, like the swallows, in an upper region of joy, which is scarcely dreamt of by those who cannot soar so high.

Peggy and Bobby sat at the top of a high apple-tree in a cunning little seat just where one bough crossed another, and, bending up, formed a kind of armchair with a back to it. Below them the pink apple-blossom spread like a rosy cloud against the bluest of skies, and a blackbird in a neighbouring bush was trilling his loudest.

Easter had fallen late, so that the children's spring holidays were not yet over when the first early delightful days of May brought a foretaste of the coming summer. Peggy and Bobby were out the whole day long, following their father about the farm, riding on the slow plough-horses, helping to drive the sheep, or bringing home the cows from the pasture, sowing seeds in their little gardens, and generally revelling in the delicious freedom.

Sometimes Lilian would join them, but more often she was busy indoors, helping her aunt and Nancy, the maid, and learning the mysteries of housekeeping and dairy-minding; for she was growing quite a nice little[13] companion to Aunt Helen, and becoming so useful that Nancy declared they should scarcely know what to do without her when the term began again.

'What shall we do this afternoon?' said Bobby, leaning back among the branches in a way that would have brought Aunt Helen's heart to her mouth if she had not long ago come to the conclusion that small boys have nine lives, like a cat.

'I don't know,' replied Peggy, idly picking off bits of twig, and throwing them at the old gander, which had strayed underneath.

'Then let's go birds'-nesting. You can't think how dreadfully I want to find a cuckoo's egg. Arthur Hill has one at school, and he's so proud of it, he wouldn't change it though a boy offered him five sticks of mint-rock and a pea-shooter. I'm sure we ought to get one about here: I've heard such lots of cuckoos lately. We'll look in every nest we find.'

'All right, we'll go down the meadows by the river into the hazel-wood.'

'No, no! Up the hill, over the gorse common, and down the yew-tree lane.'

'You won't find any nests up there!'

'Yes, I shall!'

'I tell you you won't!'

'And I tell you I shall!'

'You were only eight last January, and I shall be twelve in November, so I ought to know best!' said Peggy crushingly.

'I don't care if you're a hundred!' replied Bobby with scorn. 'Joe was up there last night, and he found twelve nests, and, what's more, he told me just where they all are.'

'Then, why couldn't you say so at first? Are you sure you can find them?'

[14]'Certain; and one of them's a long-tailed tit's, with ever so many eggs in it. Do you want to go down by the river now?'

'No,' replied Peggy, giving in graciously. 'A bird in the hand is worth two in the bush, and if Joe really found the nests up there, it's worth while going to see.'

Bobby climbed down in triumph, for Peggy so generally took the lead that it was sweet for once to get his own way. He was rather a gentle little boy, ready as a rule to follow at Peggy's bidding, and to make a lively second to any scheme she might have in hand. Aunt Helen sometimes thought the two must have got changed, and that Peggy should have been the boy and Bobby the girl; for though the latter was not without courage, it was certainly Peggy who had the most of that enterprising spirit which is generally thought a characteristic of the masculine mind.

Though she would not have minded being a genuine boy, Peggy had the greatest objection to be called a tomboy—a term of reproach that had been hurled at her head from her earliest infancy by indiscriminating friends.

'If they meant anything nice by it, I shouldn't care,' she complained. 'But they don't, for a tomboy is a horrid, rough sort of creature who isn't fit to be either a boy or a girl. It's too bad that I can't even do useful things without people howling at me. Mrs. Davenport looked perfectly shocked when I harnessed the pony, though I told her Joe was milking, and there was no one else to come and do it; and when old Mr. Cooper saw me help Father to drive cows down the pasture, he popped out with "Miss Tomboy" at once, though he did say afterwards I was the right sort of girl. People didn't call Joan of Arc and Grace Darling tomboys,[15] though they did other things besides stay at home and darn stockings. Why can't I climb trees and jump fences, and enjoy myself like boys do, and yet be a thorough girl all the same?'

To do Peggy justice, I think she was right, for though she delighted in outdoor life, she was in no sense a rough or ill-mannered child, and loved pretty things and dainty ways as well as quieter Lilian; but it was a case of a dog with a bad name, for however indignantly she might remonstrate, people had got into the habit of dubbing her 'tomboy,' and at that valuation she seemed likely to remain.

The walk which Bobby had proposed this afternoon was somewhat of a scramble, for the country rose behind the Abbey into undulating hills, which were fairly steep, though not so high as the Welsh mountains, and were covered for the most part with gorse and rough grass, where the sheep and young bullocks were turned out to graze. It was rather a stiff pull up to the common, but the Vaughans were as accustomed to climbing as mountain goats, and would have thought it far more wearisome to walk the length of a London street.

Half-way up was a spot very dear to the children's hearts. At a turn of the road a great slab of Welsh slatestone lay at a sloping angle, shelving down for a distance of about twenty feet, and with its surface so flat and even, and so smooth and polished by the weather, that it made a natural sliding-board, down which it was delightful to toboggan at full speed. It seemed expressly formed for the enjoyment of small boys and girls, for as it lay across a corner, you had only to walk up the road to get to the top, then settling yourself firmly with feet straight in front, you let go, and slid like a bolt from an arrow down—down—till[16] you found your feet on the road again, and could climb up once more and repeat the performance.

Of course, it was not very nice for the backs of boots and knickerbockers, and frocks and pinafores were apt to get sadly torn if they caught on a projecting angle; but what child ever thought of clothes when a twenty-foot slide might be enjoyed? Certainly not Peggy or Bobby, whose well-worn garments were generally made of the stoutest and most serviceable materials.

They spent quite half an hour at this enthralling pastime, till a very persistent cuckoo in a little copse over the hedge recalled them to the principal object of their ramble.

'Come along!' shouted Peggy. 'We're wasting time!'

'Let's take the short cut,' cried Bobby, hopping nimbly over the fence into the meadow, where the kingcups were lying, such a bright mass of gold in the sunshine that you might have thought the stars had fallen from the sky and were shining in the fields instead. Little rabbits scuttled away before them into the hedgerows, and a cock pheasant, disturbed in his afternoon nap, flew with a great whir into the coppice close by. Two fields brought them out on to the common, where the gorse was a blaze of colour and the bees were busy buzzing among the sweet-smelling blossom.

'Joe said there was a yellowhammer's nest just there, close by the elder-bush,' said Bobby.

'All right,' said Peggy; 'you take one side of the tree, and I'll take the other.'

A few minutes' search resulted in a delighted 'S'sh!' from Bobby, for on a little ledge of rock under an overhanging tussock of grass was the cosiest, cunningest nest in the world, and the yellowhammer herself sat on it, looking at them with her bright little eyes,[17] half undecided whether to stay or to fly away in alarm.

Peggy crept up as quietly as a mouse. Though the children were very anxious to find nests, it was not in any spirit of ruthless robbery. Mr. Vaughan was a keen naturalist, and had taught them to watch the birds in their haunts, but disturb them as little as possible, taking an occasional egg for their collection, but only when there were so many in the nest that it would not be missed.

'Isn't she stunning?' whispered Bobby. 'And how tight she sits!'

But a human voice was too much for the yellowhammer, and she flew like a dart into the gorse-bushes.

'Five eggs,' said Peggy, 'but not one of them a cuckoo's. You don't want one, do you, Bobby?'

'No, I've got three at home. I had five, but I swopped two of them with Frank Wilson for a redstart's.'

'Come along, then; she'll soon fly back when we're gone; I believe she is watching us out of the elder-tree. Where did Joe say the long-tailed tits had built?'

'Right in the middle of a gorse-bush, just on the top of the mound where the goat was tethered last year. He calls them bottle-tits, but it's just the same thing, Father says. Whew! isn't the grass scratchy on your legs!'

'Horrid! My boots are full of prickles. I shall have to take them off soon. It's so deep here, it's scratching my very nose. Oh, look, Bobby! There goes one of the tits! I saw just where she flew from. Oh, here it is! See, isn't it just the prettiest little nest that ever was?'

The tit's nest would certainly have gained the prize if all the birds had been asked to take part in a building[18] competition. It was made of the softest moss and lichens, fashioned together in the shape of a bottle with the neck downwards; for the tit must have some place in which to bestow her long tail, and she builds her home to suit her person.

Peggy thrust a cautious finger through the tiny opening in the side.

'It's full of eggs!' she exclaimed; 'I should think there must be seven or eight. I'll take two, one for you and one for me. They're the smallest you ever saw, and so warm. I hope they'll blow easily.'

Bobby had brought a box full of sheep's wool in his pocket, to hold anything they might find, so Peggy laid the eggs in with great pride, for bottle-tits were rare in that neighbourhood, and they had long wished to find such a treasure. Joe had certainly not misled them, and Bobby's memory, though defective as regarded Latin declensions and historical facts, was unerring where it was a case of locating birds'-nests.

He found three thrushes' nests low down in the elder-bushes, all filled with gaping yellow mouths, the pretty little chaffinch's up in the ivy-tree, with only two speckly eggs as yet, and Jenny Wren's household, hidden away in a bank, full of so many children that she surely resembled the old woman who lived in a shoe, and it was a marvel how she could remember which little chirping atom she had fed last. The robin had built early and her brood had flown and left the empty nest; but two blackbirds were sitting in the hawthorn-hedge, and flew away with cries of indignation and distress.

The cuckoos were still calling loudly in the distance.

'Tiresome things!' said Bobby; 'if they would only build nests like other birds, one might have a chance of finding them.'

quoted Peggy.

'But you haven't said it all,' put in Bobby.

'I wish the rhymes would tell us where she lays her eggs,' said Peggy.

She was poking about in the mossy bank as she spoke, when a hedge-sparrow flew out from the low bushes above almost straight into her face. It did not take Peggy long to find the neat little nest of twisted twigs and grass woven into the fork of a branch. There were four lovely blue eggs inside, and a slightly larger one of a greenish-gray colour. Peggy flushed all over with excitement.

'Bobby, Bobby!' she screamed, 'come here, quick! I do believe I have found a cuckoo's egg!'

There seemed little doubt about it, for the egg really looked quite different to the others; so the treasured find was safely put away in the small box, to be shown to Joe, who was wise in such lore, though he only knew the birds by their country names, and had never heard of such a science as ornithology. Quite elated with their success, the children hunted down the lane, searching in every bush and hedgerow, but they found nothing but a few last year's nests, full of acorns and dead leaves.

They came out by Betsy Owen's cottage—a little low, whitewashed, tumble-down building, standing in the midst of a neglected garden, with a very forlorn and deserted air about it.

[20]'Joe says no doubt there'd be lots of nests in the ivy there,' confided Bobby, peeping through the hedge. 'But he wouldn't go in and see, not if you gave him five pounds for it.'

'Why not?' demanded Peggy.

'Because old Betsy's a witch, and you never know what she might do if you made her angry. John Parker and Evan Williams took some sticks from her hedge last autumn, and she came out in a rage, and crossed her fingers at them, and in six weeks John broke his leg, and Evan had sore eyes all the winter. And once Joe and another boy were coming home very late at night past the cottage, and they saw a bright light, and just as they reached the gate it went out, and they heard a most fearful shriek, and they were so frightened they ran all the way home.'

'What nonsense!' said Peggy. 'I expect the old woman was blowing out her candle to go to bed, and a screech-owl flew over their heads. Joe would have run away from his own shadow. But if you're afraid, stay outside in the lane, for I'm going in to see if there's a nest in that ivy; it looks such a likely place. I don't believe anyone's in the cottage, either, for the door's shut.'

But Bobby much resented such a slur on his manly courage, and insisted upon being the one to climb the ivy-covered chimney. He crept quietly round to the back of the cottage, and swung himself up by the thick stems, feeling in every little hole where he could lay his hand. The large old chimney was so wide at the top that he found he could peep right down it, as if he were looking into a well, and could see a good piece of the hearth underneath, with a small fire of sticks burning under a large, three-legged iron pot, and the old woman sitting close by on a low stool, smoking a short clay pipe.

[21]Betsy Owen was a withered, cross-grained old dame, who by dint of the knowledge of the uses of some simple herbs and a good deal of cunning, had contrived to establish a reputation something between a witch and a quack doctor. People came to her from remote farms to have warts charmed away or the toothache cured; she dressed burns and wounds, and concocted lotions for sore eyes and bad legs. Her one room was hung all round with plants in various stages of drying, and she was always ready to prescribe a remedy for an ailing cow or a sick child, generally at much profit to herself, whatever might be the benefit to the sufferer. She was bending over her iron pot now, stirring the concoction with a long-handled spoon. Bobby could see her quite plainly in the fire light, and could catch the curious aromatic smell which rose up from the smouldering wood. I do not know what prompted him—probably the love of mischief which dwells in all small boys—but he picked up a loose piece of mortar which was lying on the roof, and dropped it suddenly down the chimney. It fell plump into the iron pot with a loud, hissing sound.

Out rushed Betsy from the cottage, scolding furiously. Down dropped Bobby from the chimney, and was through a hole in the hedge and away down the lane as fast as his sturdy legs could carry him. Peggy had been waiting in the garden, and, before she could realize what had happened, she found herself seized and shaken violently by the angry old woman.

'I'll larn yer to come into other folk's places and drop stones down decent body's chimleys!' shrieked Betsy. 'Be off with yer, yer ill-mannered young good-for-naught; and if ever I catch yer here again, yer'll get such a hidin' yer won't forget it for a month!'

Peggy was so amazed by the suddenness of the attack[22] that for the moment she offered no resistance; but, finding a storm of blows descending on her head like hail, she managed to squirm out of Betsy's ungentle grasp, and fled after Bobby down the lane, followed by a shower of epithets from the gate, where the old woman stood shaking her fist until long after the children were out of sight.

When they judged themselves to be at a safe distance the pair sat down on a fence to get their breath, and talk over their adventure.

'We're in for it now,' laughed Peggy. 'She was so fearfully angry I'm sure Joe would say she'd bewitched us!'

'Yes, he'll be in a great state of mind when we tell him. He'll quite expect us to break our arms or legs or necks or something before long!'

'You'll do that without her if you try to swing head downwards on one leg like that,' said Peggy; for Bobby was executing some marvellous gymnastics on the top rail of the fence.

He came down feet foremost, however, and they sauntered off along the road to the old water-mill, where the miller's man was slinging a sack of flour on to a patient donkey who stood, with drooping ears, eyeing the burden which he must carry up far into the mountains, while his mistress, a little black-eyed Welshwoman, poured forth a torrent of gossip in high-pitched tones.

The wheel was standing idle, and the children went down the slippery steps to the pool below. It was cool and dark there, for the trees grew low over the stream, and the water, escaping from the race above, poured down by the side of the wheel in a foaming cataract. A dipper was hopping about from stone to stone in the centre of the stream, pruning her sleek feathers, and[23] calling her lively 'chit, chit' to her mate. Peggy grasped Bobby by the arm.

'Keep still,' she whispered. 'Let us watch her. Perhaps she may have a nest somewhere close by.'

All unconscious of her audience, the little bird jerked her short tail, dived rapidly into the water, and, emerging at the other side of the pool, flew suddenly into the green, moss-grown wall which overhung the mill-wheel.

'That's her nest,' cried Bobby. 'Oh, don't you see it? It looks just like a great lump of moss; you can hardly tell it from the wall, only I see a little round hole at the bottom. What a shame it's in such a horrid place! We can never get it up there.'

'Yes, we can,' replied Peggy stoutly. 'I'm going up.'

'But how?'

'Up the mill-wheel, of course, stupid! No, you're not coming too. You climbed the chimney, and it's my turn. Just hold my hat, and I'll manage all right, you'll see!'

It was a slippery climb, for the wheel was green with slime, and it needed a long step to get from one blade to the other; but Peggy was utterly fearless, and she had soon pulled herself to the top. Balanced there, she could easily reach to the nest, which was only a few feet away from her. Out flew the dipper in a panic, and in went Peggy's fingers.

'Three eggs, Bobby—lovely white eggs! Look! I think I shall take this one, at any rate.'

She held out her hand to show her prize, but at that instant the mill-wheel began to turn, and she was whirled from the dizzy summit down—down—into the dark pool below.

Bobby's agonized shrieks brought out the miller's man, who, dashing into the stream, caught the child[24] just as she rose to the surface, and before she had drifted into the swifter current further on. It was a very forlorn and draggled Peggy which he laid upon the bank, but she was game to the last.

'I haven't broken the egg,' she gasped out, with the water streaming from her hair.

'Better thank the Lord you're not drowned, miss,' said the miller's man, looking ruefully at his own wet garments. 'Let me take you into the house, and Mrs. Griffiths'll get you some dry clothes to your back; you'll catch your death of cold sitting there.'

Peggy essayed to get up and walk, but she was such a very water-logged vessel that to hasten matters her rescuer picked her up in his arms, and bore her off like a sack of flour.

Stout old Mrs. Griffiths was sitting knitting in the chimney-corner, but she jumped up in a hurry when John carried in his dripping burden.

'Sakes alive!' she screamed, 'what is it? Is she dead? Lay her out on the parlour sofa. Sarah Grace, run for the parish nurse and the Rector—quick!'

But Peggy's voluble tongue assuring her that she was very much alive, and only in need of drying, she soon hustled that young lady upstairs, and out of her wet clothes. Ten minutes later Peggy sat on the settle by the kitchen fire, an odd little figure, attired in Sarah Grace's Sunday jacket over Mrs. Griffiths' best red flannel petticoat, and a steaming glass of hot elder wine in her hand.

'Just to keep you from catching cold, miss; and Master Bobby must have one too, bless his heart! He's as white as my apron, and small wonder, after seeing his sister half drowned!'

After the adventure at the mill-wheel, Aunt Helen, judging wisely that 'Satan finds some mischief still for idle hands to do,' sent the children into the fields with Lilian to gather cowslips to make cowslip beer. It was pleasant work wandering among the green meadows picking the sweet-smelling flowers, while the larks sang their loudest overhead, and the little brook babbled by on its path to the river—more especially pleasant when they remembered that by this time next week school would have begun again, with its attendant woes of Latin grammar and French composition.

'I'm sure we must have enough now,' said Lilian, turning out her sixteenth basket of blossoms into the ever-increasing pile in the bakehouse. 'I'm almost tired of gathering them; I shall see nothing but cowslips when I shut my eyes in bed to-night.'

'It will take a fearfully long time to pick them all,' remarked Peggy, starting bravely to work on her task of pulling the yellow pips away from the green calyces. 'It seems almost a shame to put them into a barrel, they look so pretty.'

'You won't say so when you come to taste it,' said[26] unromantic Bobby, who was fond of cool, fizzy drinks in summer.

'Be that you, miss?' said a voice from the region of the door; and the good-natured, freckled face and sandy hair of Joe, the farm-boy, made its appearance, followed by the rest of his lanky person, as he entered slowly, bearing something mysteriously concealed under his coat.

'Whatever have you got there, Joe?' cried three voices at once.

'Well,' replied Joe, with an important air, 'it do be a present for Miss Peggy, it be. She were that disappointed about the guinea-pig as Mrs. Davenport promised to give her, and forgot all about, that I says to myself, "I must make it up to her some ways, if I gets the chance." So I walks over to my granny's at Marlow last night, and I begs a black pup off her, and here it is.'

Joe drew aside his jacket, and disclosed to the children's delighted eyes the sweetest little round fuzzy ball of black fluff, just like a tiny woolly bear, with tan chest and paws, and a wagging morsel of a tail like a black tassel. It had the brightest of brown eyes, the pinkest of tongues, and the shrillest of barks, and it was altogether such a dear, enchanting, soft, curly morsel of puppyhood that Peggy took it to her arms and her heart at the same moment.

'Oh, thank you, Joe!' she exclaimed, almost too pleased to speak.

'Granny has five of 'em, miss,' said Joe; 'but I picked out the best. It'll make a grand dog, it will, when it's growed, and master was sayin' only the other day as he could do with another collie to train in old Rover's place.'

'Let me have him a moment!' begged Bobby,[27] hugging the wriggling burden, which Peggy unwillingly relinquished.

'What shall you call the darling?' inquired Lilian, kissing the funny black nose that was smelling at her buttons.

'I think Rollo would be a jolly name, and of course we can all have a piece of him all the same, though he's mine,' announced Peggy magnanimously, for the Vaughans always shared their good things with one another.

They had a perfect menagerie of pets at the Abbey. First there were the rabbits, five white ones and two black, which lived in a little hutch behind the stackyard. They did not do very much except nibble at bran and lettuce-leaves, it is true, but they were pretty, soft creatures, with long, silky ears, and it was fun sometimes to let them out for a scamper on the granary floor. Then there was Prickles, a bright little hedgehog, which Peggy had rescued from some village boys who were using the poor little fellow as a football. She had brought him home, and fed him on bread and milk, and he soon got to know her, and would come when she called him, and allow her to scratch the end of his funny pink nose. Prickles generally slept most of the day in a snug box lined with hay, but in the evenings he woke up, and Peggy would carry him into the kitchen, where he devoured black-beetles, much to his own delight and Nancy's satisfaction.

Jack, the magpie, had fallen from his nest in the fir-tree when still an ugly little half-fledged creature with a wide, gaping mouth. The children had made a nest of grass for him inside a basket, and fed him on worms and scraps of raw meat until he was old enough to fly, when he would follow them everywhere about the farmyard and outbuildings, calling 'Jack, Jack!'[28] which, with the mewing of a cat, the gobble of the old turkey-cock, and a close imitation of David's winter cough, made up the extent of his accomplishments.

Nancy kept him sternly out of the kitchen, for he was terribly mischievous, and seemed to take a positive delight in playing practical jokes. He had purloined David's scarf from the saddle-room, and dropped it into the horse-trough, had filled Bobby's hat with pebbles, and devoured the queen-cakes which Lilian had placed on the kitchen window-sill to cool; he had snatched Joe's breast-pin—a glittering imitation diamond—from his Sunday tie, under the very nose of that injured youth, and had stolen so many small articles that if anything were missing the children would have a grand search for Master Jack's hiding-place, and would generally turn out the lost treasure from among an odd collection of trifles—scraps of bright-coloured rags, bits of broken glass, hairpins, pen-nibs, pencil-ends, together with pieces of bread and half-picked bones which the thief had concealed in some cunning corner inside a manger or under the roof of the loft.

Then there was Pixie, the pony, who would come whinnying up from the further side of a field to poke her soft nose into the children's pockets for pieces of bread or lumps of sugar; there were numerous cats who lived in the barns and stables, and Tabbyskins, the stately gray Persian, who usually sat sunning herself on the pigsty wall, keeping a strict eye on naughty Jack, who was wont to harry her if he got the chance.

Bobby had a pretty set of bantams, whose small eggs afforded him much delight and some slight profit, for Aunt Helen bought them from him at threepence a dozen—a transaction which he always recorded in chalk upon the hen-house door, the pennies being carefully put by towards the purchase of a pair of fantail[29] pigeons, which was at present the summit of his ambition.

This spring, too, there was a pet lamb called Daisy. David had found it bleating beside its dead mother one bitter morning early in March, and had carried the poor orphan into the kitchen, where Nancy had reared it on a feeding-bottle like a baby. It returned her care by an affection which was quite embarrassing to the worthy girl, for however attractive a pet lamb may be, it becomes distinctly in the way when it insists upon following you into the dining-room with the dinner, or presses its attentions on you when you are engaged in cleaning the grate or scrubbing the floors.

It was not only outside that the children had treasures. Aunt Helen was very long-suffering with respect to hobbies, for she rightly thought that the more a child's life is filled with interests, the more chance it has of growing up an intelligent and broad-minded individual, and of escaping from that lethargy of boredom which swallows up the lives of many young people who ought to know better how to amuse themselves in God's beautiful world. 'I don't know what to do,' was an unknown expression among the young Vaughans, who had always so many projects on hand that the difficulty lay in finding time to carry them all out.

The Rose Parlour, as it was called, from the tangle of pink roses which framed the windows in summer-time, was especially given up to the children's use. It was a bright, cheerful room, with a view over the river to the sunset and the Welsh mountains, and had a French window which opened into the garden. Here was the old piano on which they practised, here the ink-pots and rulers for their home-lessons, with their paint-boxes, crayons, and drawing-books.

A cupboard in the corner was devoted to a kind of[30] museum, where they kept their collection of birds' eggs, a few butterflies, moths, and beetles, Lilian's pressed wild-flowers, a box full of shells and fossils which they had brought home from their one never-to-be-forgotten visit to the seaside, a curious plaited basket filled with bone rings, shell bracelets, and other curiosities, sent by a sailor cousin from the South Sea Islands, and an odd assortment of stones, old coins, foreign stamps, crests and postmarks, which represented landmarks in the history of past fads.

Lilian's canary hung in the sunniest window, Peggy's silkworms lay in a box on the sideboard, and Bobby's white mice reposed in much comfort in a cage on the chimneypiece.

The walls were adorned with school drawings and prize maps, fastened up with tacks; a bookcase of much-read volumes filled the space between the fireplace and the window; and in the corner might be found a miscellaneous collection of cricket-bats, fishing-rods, tennis-racquets, bows and arrows, croquet-mallets, sticks, balls and ninepins, and other articles very dear to the children's hearts, but which Nancy generally classed impartially under the head of 'lumber.'

The black puppy proved a delightful addition to the already long list of pets. Lilian hunted up a piece of blue ribbon to tie round his fluffy neck; but he objected to decorations, and soon clawed it off, and chewed it into a soft, slimy pulp. He ran after the children with little short, sharp barks, worrying at their heels till Aunt Helen declared there would soon not be a whole stocking left in the establishment; he had a fray at once with Jack, but was much worsted by that worthy, returning to Peggy for protection with his scrap of a tail between his legs; he tore Bobby's cricket-ball to pieces, licked the polish off Father's boots, devoured[31] Aunt Helen's goloshes, and nestled cosily down to sleep on the top of Nancy's best Sunday hat, which that luckless damsel had imprudently left in an open band-box on the kitchen settle.

On the first night of his arrival he howled so piteously on being left alone that Peggy insisted on taking him to bed with her.

'He'll be no trouble, the darling!' she said. 'He'll just cuddle down on the rug at the foot of my bed, and go to sleep like an angel; I know he will!'

She and Lilian made him a very snug little nest with the help of an old pillow, and he settled himself with a sigh of much content.

'He's far better than a baby,' declared Peggy, 'for he doesn't want hushing and rocking, and he won't cry in the night.'

But his fond mistress had given her favourite his good character a little too soon. About midnight the bright moonlight streaming in through the window woke Master Rollo, who, having had a refreshing nap, was now very wide awake, and ready for anything. He heaved himself out of his wrappings, and with a delighted yelp fell upon Peggy's curls, worrying them with little gasps of joy, till she had to dive beneath the bedclothes to escape her too sportive pet.

After that there was no more rest for Peggy or Lilian; Rollo was on the war-path, and determined to make the most of his opportunities. It was in vain that Lilian held him in her arms, and tried to soothe him to sleep; he grunted and whined, and wriggled down on to the floor, where, with a shrill bark, he unearthed a cardboard box full of old gloves, which had been stored away under the bed. The chewing and tearing up of these afforded him much sport, as did also the bare feet of his mistress, when she attempted to interfere.[32] Peggy was at her wits' end, but she finally seized the tempestuous ball of fluff, and dropped him to the bottom of the empty clothes-basket.

'He can't do any harm in there, at any rate,' she said hopefully.

He could make such a noise, however, that he effectually banished slumber; he twisted and turned, he bit at the wickerwork, and scratched with his claws, and after ten minutes of much commotion managed to tip over the basket and crawl out in triumph, to renew his attacks upon the shoes and other property of the despairing girls.

'It's no use,' groaned Lilian at last, getting out of bed and catching the small sinner; 'we shall just have to take it in turns to nurse him till morning; he's as lively as a cricket, and if we leave him raging about on the floor like that we shan't have a thing in the room left unchewed!'

Never had a night seemed so long; the only one who thoroughly enjoyed himself was the puppy, who, delighted to receive so much attention, pursued his diversions until the sun was well in at the window, when at length he snuggled into Peggy's pillow, and composed himself to sleep, leaving his weary guardians only time for a brief rest before Nancy's unwelcome tap was heard at the door.

After this experience Peggy was not so enthusiastic about having Rollo for a bedfellow, and he slept in the stables, with the cats to bear him company.

He was an amusing little fellow, and soon learned to sit up and beg for biscuits, and Peggy promised herself to teach him many more accomplishments in course of time. As he grew older his pranks assumed rather a more serious form.

'Just look what that precious dog of yours has done,[33] Peggy!' cried Mr. Vaughan one day, bursting indignantly into the Rose Parlour with a dead kitten in his hand.

There was a howl of consternation and woe from the children, for the poor gray kit had been rather a favourite, and an instant search was made for the murderer. But Rollo had fled from the stern hand of justice, and though they sought him far and near, it was of no avail, and by bedtime he was still missing.

'No doubt he's hiding somewhere about in the barns,' said Lilian. 'He must be fearfully hungry; but it serves him right, the wretch!'

The children had long ago gone to bed, and Mr. Vaughan was on the point of following their example when he noticed a curious and most unusual lump underneath his counterpane.

'What on earth has that stupid Nancy given me a hot bottle for on such a warm evening?' he exclaimed; and flinging down the clothes he disclosed to view, not the expected earthenware bottle, but the shrinking and apologetic form of Master Rollo, who, if ever a dog could be said to own a conscience, surely showed he knew he had offended, and repented heartily of his sins.

Mr. Vaughan laughed so much that he had not the heart to thrash the little rogue, but next morning he devised a punishment for him which Peggy declared was far worse. The body of the dead kitten was securely tied round his neck with a piece of rope, and, like the albatross in the ballad of the 'Ancient Mariner,' it proved such a weight of shame that the guilty dog did not dare to show his face to his friends, but slunk away to hide his dishonoured head in dark corners of the barn or stackyard.

Mr. Vaughan was inflexible, and would not allow[34] Rollo to be relieved from his burden until the following evening.

'We must teach him a lesson he is not likely to forget,' he said. 'I cannot have him touching any of the animals on the farm, or we shall have him killing the sheep when he is older.'

So Rollo bore his punishment as best he could, and was fed behind the pigsty by the sympathetic Peggy, who, while mourning for the departed Ruffles, forgave her erring pet from the bottom of her heart when she saw the depths of his unutterable woe.

Though Gorswen was the most quiet little country spot you could find, it lay only four miles away from Warford, a rising inland watering-place, which boasted not only a Mayor and Corporation, but a pump-room and concert-hall, and had a large and fleeting population of visitors, and, to judge by its growing suburbs, an ever-increasing number of residents.

Lilian and Peggy attended the Warford High School, and Bobby the Grammar School. It was not quite what Father would have wished for them, for he had been a Rugby boy himself, but it was the best he could afford; and certainly the education was excellent, though the pupils were decidedly mixed. Still, as Aunt Helen said, 'You have no need to copy the manners of the children you meet. You have been taught at home to behave like gentlepeople, so please to remember you are Vaughans, and keep up the credit of the family.'

Every morning at eight o'clock the little governess-car and Pixie, the steady black pony, stood ready at the side gate, and the trio jogged off to school with their lesson-books and their luncheons in their satchels.[36] David could not be spared to go with them, but all the children had been taught to drive, and even Bobby had a firm hand on the reins, and knew the rules of the road as well as many a more experienced coachman; and I think, too, that Pixie had a sense of her responsibilities, and could be trusted not to get the wheel locked with a passing waggon, or to race too furiously down a steep hill, whatever feats her drivers might urge her to perform. The pony and trap were put up for the day at a quiet little inn midway between the two schools, and were always waiting for the children by a quarter past four, when, like the traditional donkey, they joyfully turned their noses towards home again.

On one special Monday morning in May Peggy got out of bed in that peculiar frame of mind which Father charitably called 'highly strung,' and Nancy broadly defined as 'having black dog on your back.' To begin with, it was wet. Not that Peggy minded rain in the least, but if it were fine Mr. Vaughan had intended to go over to a great cattle fair which was to be held that day at Shrewsbury, and had promised to bring her home a guinea-pig. 'And now he won't go,' she thought dismally, 'and I shan't have the chance of another until Warford Agricultural Show in the autumn.'

Peggy hated Monday mornings. After the delightful freedom of Saturday and Sunday at home it was always doubly hard to return to school, and the time until next Friday afternoon seemed an endless prospect. All the nastiest lessons, Peggy thought, came on Mondays—grammar and arithmetic, dates and French verbs, and all those horrid fussy things which take a great deal of learning without being specially interesting in themselves.

[37]On this particular morning the children were late for school, for Pixie had cast a shoe upon the road, and Lilian had been obliged to drive so slowly that the church clock was chiming a quarter past nine as Peggy opened her classroom door.

It is rather an ordeal to walk late into a schoolroom full of thirty girls, and the slightly nervous feeling had the unfortunate effect of making Peggy march in with a don't-care look on her face, and shut the door with a bang.

Miss Crossland glared at her through her eyeglasses.

'If you are so careless as to be late, Margaret Vaughan,' she remarked, 'the least you can do is to come in quietly without disturbing the class.'

Rather crestfallen, Peggy threaded her way to her place, and took out her arithmetic books.

'Which sum are you doing?' she whispered to her desk-mate, Emily Thompson; but Emily judiciously pretended not to hear, for she did not wish to waste valuable time in giving Peggy information. She was rather a pretty girl. Her light flaxen hair and pale, fair complexion gave her a smooth, shining appearance, and somehow Peggy always thought her manners were smooth and shining too, for she had a way of wriggling out of any little difficulty and unpleasantness, so that the blame rested upon other people, and was always ready to take a mean advantage, or play some of those little underhand tricks which schoolgirls know only too well.

Peggy's frank, downright nature held Emily in much contempt, and, as she made no effort to conceal her opinion, the dislike was mutual, and a kind of undeclared war existed between the two. It was unfortunate for Peggy that the third form classroom was furnished with double desks, for as Miss Crossland[38] would permit no changing of places, she was obliged to sit by her enemy for the rest of the term, to their equal discomfort and annoyance.

The lesson dragged on wearily for awhile, till they were disturbed by a tap at the door, and a small girl from one of the lower classes entered, full of importance at her errand.

'If you please, Miss Crossland,' she piped, 'Miss Martin would like to speak to you for a moment in the library.'

Miss Crossland looked annoyed; she disliked being interrupted in her classes, but the head-mistress's request could not be disobeyed.

'Very well, Gertrude,' she replied coldly; then, turning to her class: 'Girls, I must leave you for a few minutes. I trust you to continue your arithmetic in silence during my absence. Not a word must be spoken while I am out of the room.'

For so long indeed as her footsteps echoed in the passage her pupils obeyed her order, but the moment she might reasonably be believed to be out of earshot a low murmur began among the little heads bent so discreetly over the arithmetic books. No one attempted to do any work; sweets and apples appeared mysteriously from within desks, and surreptitious bites were offered to appreciative neighbours. One daring spirit even mounted the platform, and waved the pointer in supposed imitation of Miss Crossland's majestic style.

'What made you so late, Peggy?' asked Nora Pemberton in the intervals of ecstatic delight over a white mouse, hidden away in a desk-mate's lunchbox.

'Couldn't help it,' replied Peggy, with her mouth full of chocolate. 'Pixie lost a shoe, and we thought[39] she would go lame, so we almost crawled along; and when we got her in, we had to tell them to be sure and have her shod by four o'clock, and of course it all takes time.'

'I wish I drove to school every day,' said Sissie Wilson, a delicate looking girl who lived in the heart of the town.

'You wouldn't like it when it was wet,' said Peggy. 'And if it's frosty one's hands get just numb holding the reins, though it's jolly enough in summer. We have to start ever so early, too, to be here by nine.'

'Well, I only wish I had the chance,' grumbled the envious Sissie; but she was interrupted by a warning 'Hush! Miss Crossland!'

In a moment thirty hair-ribbons were bent over thirty desks, and thirty demure young ladies were adding up figures with the utmost care and attention.

Miss Crossland looked at them suspiciously; perhaps ten years of teaching had caused her to mistrust such amazing diligence.

'Has any girl spoken during my absence?' she inquired sharply.

No one replied. Peggy's face flushed, and her conscience gave her a sharp twinge. A Vaughan must never have anything to do with the least little bit of an untruth, so she stood bravely up in her place.

'I spoke, Miss Crossland,' she admitted.

'And I too,' said Nora Pemberton.

Nobody else followed Peggy's example. Sissie Wilson bit the end of her pencil in abstruse calculation, Emily Thompson was deep in the pages of her arithmetic, while most of the girls were adding up columns as if for dear life.

Miss Crossland looked grave.

'Very well, Margaret and Nora,' she said, 'I must[40] give you each a bad-conduct mark, and shall expect you both to stay after four o'clock this afternoon.'

The tears rose to Peggy's eyes at the injustice.

'What a mean set they are!' she said to herself. 'I'm sure Miss Crossland might have known they had been talking too; but she is always down upon me.'

She opened her desk, and searched for a fresh pencil to hide her tell-tale face, and somehow (she really did not mean it, but perhaps her tears blinded her) the desk-lid slid from her fingers, and fell down with an awful crash, which rang through the whole room.

'Take another bad-conduct mark, Margaret Vaughan,' said the calm voice of Miss Crossland. 'You must learn not to show temper when you are reproved.'

Poor Peggy groaned. Every bad-conduct mark meant six sums to be worked out when school was over. She and Lilian had been very anxious to get home early that afternoon, for they had meant to sow seeds in the garden; and Father was always angry if they kept Bobby waiting, for he did not like him to be loitering about the inn-yard listening to the talk of the stable-boys.

But Miss Crossland was writing a problem upon the blackboard in compound proportion. 'If a hen and a half lay an egg and a half in a day and a half, how many eggs can four hens lay in six days?'

'What a stupid sum!' thought Peggy. 'How could there be a hen and a half? I don't know the least how to state it. Is the answer to come out in hens or eggs or days?'

She put down a few random figures, then her thoughts wandered off to the brown speckled hen at home, and she wondered if the little chicks would hatch out to-day, and whether Nancy would remember to go[41] and see, and put the dear fluffy yellow things in a basket before the kitchen fire.

'Your answer, Margaret?' said Miss Crossland. But Peggy's mind was so far away in the Abbey barn that she did not at once hear her.

Perhaps Emily Thompson really wished to recall Peggy's wandering thoughts, or perhaps there was just a spice of malice in the action—at any rate, she dug the point of her lead-pencil so sharply into poor Peggy's hand that her astonished victim sat up with a yell.

'Margaret!' exclaimed the outraged mistress.

'I couldn't help it!' cried Peggy, grown desperate: 'Emily hurt me so!'

'I'm very sorry, Miss Crossland,' said Emily sweetly. 'I didn't mean to hurt Margaret, only to make her see you were speaking to her.'

'Which would not have been necessary if she had been attending properly,' replied the mistress. 'And I must say I think little of any girl who cannot endure a moment's pain in silence. Read out your answer, Emily, and I will then correct the home-work.'

Peggy heaved a sigh of relief at that. She knew the sums which she had worked at home on Saturday were correct, for Lilian had gone over them carefully afterwards, so she opened her book and took up her pencil ready to put a triumphant 'R' to each of them.

'Miss Martin has borrowed my Blackie's Arithmetic,' said Miss Crossland, 'so I have not the answers here. But read out your results, Bertha Muir, and I shall be able to judge from the general average whether they are correct or not.'

'Three hundred and nineteen pounds six and sevenpence,' read out Bertha.

[42]'Hands up girls who have got that answer,' said Miss Crossland.

At least twenty out of the thirty hands went up like lightning into the air.

'Right!' ventured the teacher.

Peggy gazed at her sum in amazement. She differed from the answer by several figures. Could both she and Lilian have made a mistake? It seemed impossible, for Lilian was so splendid at arithmetic. But Bertha was reading out the next sum, and the next. To each answer she gave a crowd of uplifted hands agreed with her, and poor Peggy found, to her chagrin, that in every case her figures were not the same. It could not be that all the ten sums she had taken so much pains over were wrong. If so, it meant a very bad mark for arithmetic.

'Oh, Miss Crossland,' she burst out, 'it's not fair! I know my answers were right. If you would only work them out on the board, you'd soon see.'

'Margaret Vaughan,' said Miss Crossland sternly, 'I am the best judge in this matter, and if I have any more trouble with you this morning I shall send you straight to Miss Martin. I do not allow any girl to speak to me in that tone.'

Though inwardly raging, Peggy was forced to put on an outward appearance of submission and good behaviour, and the lessons droned on somehow until the morning was over. Most of the girls fled, as usual the moment the class was dismissed; but Peggy stayed behind in the schoolroom to tidy her desk and talk to Nora Pemberton, who just at present was her particular friend among her schoolmates.

'I can't think how it was my sums were all wrong,' she lamented, as she put away the ill-fated home-lesson book. 'Did you get yours right, Nora?'

[43]'No, wrong, every one; and I had worked them so carefully.'

'Just let me look at your answers. Why, they are exactly like mine! I know they are right. How is it all the other girls got the same as Bertha?'

'Oh, I can tell you that,' said Nora, 'They all copied her sums, for I saw them doing it just before school began. You know it was the Military Bazaar at the Assembly Rooms on Saturday, and I suppose most of the girls were there, and had no time to do their home-work, so they just scribbled down Bertha's figures before the bell rang.'

'How unfair! How shamefully mean!' cried Peggy, with flaming cheeks. 'Miss Crossland ought to work out those sums.'

'She won't, though. You made her so angry about it this morning, and when once she says a thing she sticks to it.'

'She's always hard on me somehow,' sighed Peggy. 'She's been perfectly horrible to-day. Why, Nora, what's the matter?'

For Nora had also had a tidy fit, and had been turning out her desk, and she now drew forth a book with such a very blank and rueful face that Peggy might well exclaim.

'It's the Literature Notes,' said Nora in an awe-struck voice—'that book Miss Martin lent us to copy from, and that vanished so mysteriously a month ago. Don't you remember what a fearful fuss she made about it, and we were all told to search in our desks? I thought I had looked quite to the bottom of mine, but there it was, under a pile of old exercise-books. Whatever shall I do? She will be so dreadfully angry with me.'

'Why, of course, you'll have to take it back,' said[44] Peggy. 'But,' her love of mischief getting the upper hand, 'I don't see why we shouldn't have a little fun with it first. You won't find Miss Martin in the library now, and it would do quite as well at four o'clock, so suppose you put it inside Mary Hill's desk, just to give her a fright. She's such a goose, she'll give a perfect howl of horror when she finds it, and then we'll pretend to think she must have had it there all the time, and get her into such a state of mind before we tell her.'

Nora laughed, for practical jokes were at a high tide of popularity in the class, and many were the tricks which the girls played on one another.

'I owe Mary something,' she said, 'for she tied my hair-ribbon to the back of the desk on Friday, and when I tried to get up I was held fast by my pigtail.'

'It will be a good way to pay her back, then,' said Peggy. 'See, I'll put it just on the top in front, where she'll find it first thing; but don't tell a soul till this afternoon, or you'll spoil all the fun.'

The two conspirators ran downstairs laughing, and were soon romping in the playground. After dinner one of the elder girls suggested rounders, and the game grew so enthralling that time flew by until the bell, ringing for afternoon school, sent the players, hot and rosy with their exertions, hurrying up the great staircase to their classrooms. As Peggy passed the door of Miss Martin's study she happened to notice Mary Hill come out of it, with a particularly red and uncomfortable look upon her face.

'What has she been doing there?' thought Peggy; but there was neither time to inquire Mary's errand nor to carry out her anticipated joke with the note-book, for the girls were taking their places, and Miss Crossland came in a moment afterwards.

[45]She mounted the platform and rang the bell for order, but, instead of calling their names as usual, she announced:

'Girls, Miss Martin desires that you should all be present in the lecture-hall, where she wishes to address the whole school. File out in order, beginning with the top desk on the right.'

Full of astonishment, the girls marched down to the large lecture-hall, where all the classes were assembling, marshalled by their teachers. It was evidently a matter of some importance, for it was seldom indeed that lessons were interrupted in this manner. The girls kept whispering to each other under their breath:

'Whatever can it all be about? Have you heard anything? Why does she want us all here?'

But their surmises were soon put an end to by the appearance of Miss Martin herself, stately and commanding as usual, and with a grieved look on her face. She mounted the platform, and with a little sigh turned to her expectant audience.

'Girls,' she began, with an air almost of tragedy, 'a very distressing incident has happened to-day—a circumstance which in all the records of this school has never occurred before. You see this book in my hand,' and she held up (oh, luckless Peggy!) the missing note-book. 'This book of manuscript notes, which I had compiled myself from various sources, and valued greatly, I lent to be copied by the third form. It was lost, and though I caused every search to be made, I could find no trace of it. Girls, I regret to say that to-day this book has been brought back to school, and has been placed in another girl's desk—in the desk, I repeat, of an innocent girl, who had nothing to do with its loss.'

Miss Martin paused, and a wave of horror passed[46] over the school. As for Peggy, her blood ran cold. It had never struck her before that the act of placing the book in Mary's desk could be open to such a construction. She had meant it all for a joke, and thought Mary would have been the first to join in the fun, and then Nora would, of course, have taken it back. She saw now that, while they had still been romping at rounders, Mary must have gone up to the schoolroom, and finding the missing notes in her desk, had carried them at once to the library.

'Oh, why did we not come up sooner?' groaned Peggy. 'Who would ever have thought of Miss Martin taking it like this?'

'I feel,' continued the head-mistress sadly, 'that we have one girl among us of so dishonourable a nature that she seeks to hide her fault by throwing the blame on to the shoulders of another. Who that girl may be I cannot tell, but her own conscience must surely convict her.'

She paused again, and her glance passed slowly round the room. Peggy's face grew burning hot.

'I am determined,' Miss Martin went on, 'to probe this matter to the bottom, and I now call upon any girl who may have any knowledge on the subject to rise up and tell what she knows.'

Peggy tried to look at Nora, but Nora was several rows behind her. For one moment she hesitated, and in that moment she was lost. Emily Thompson had risen in her place.

'Well, Emily,' said Miss Martin gravely, 'do you know anything about this unhappy affair?'

'I do, Miss Martin,' replied Emily in a low voice.

'Tell me at once, then,' commanded the head-mistress.

'I would much rather not, please,' said Emily,[47] casting down her eyes. 'I don't like getting another girl into trouble.'

'Emily Thompson, this is not the time to shield a companion, and I order you to say at once what you know.'

'Well,' said Emily, twisting her slim hands nervously, 'if I must tell, I went back to the schoolroom before dinner for my pencil-box, and,' with a sidelong look at Peggy, 'I noticed Margaret Vaughan putting a book inside Mary Hill's desk.'

The bolt had fallen. Miss Martin turned to Peggy, who, with white and quivering lips, sat as still as if she had been frozen on to the form.

'Is this false or true, Margaret Vaughan?' she asked, in a voice that was scarcely more than a whisper.

There were nearly four hundred girls in the room, but you could have heard a pin drop in the silence. Lilian had risen half up in her place, and was looking at Peggy with eager, expectant face. As for Peggy, she felt as if the end of the world had come. She could not in truth deny the fact, though of the intention she was absolutely guiltless. She had never in her life told a lie, and she summoned all the Vaughan spirit to her aid.

'It's true,' she faltered, trying to speak bravely, but wishing all the time that she could sink through the floor.

Miss Martin gazed at her for a moment as if dumbfounded.

'That will do,' she said at last. 'I will inquire into this privately. Miss Pope, will you kindly take Margaret Vaughan into the kindergarten classroom, where she will wait until I come to her? Each form may now leave the room in turn. We have wasted too much time already.'

[48]Peggy's head was in a whirl. She had a confused idea that Lilian was trying to come to her across a row of benches, and was being held back by a teacher; but otherwise she scarcely knew what was happening, except that she seemed to be the centre for all the eight hundred eyes in the room, till Miss Pope took her by the shoulder and marched her away like a warder escorting a very small convict to gaol. The kindergarten babies did not return to school in the afternoon, so their little classroom was empty. Left alone, the poor child flung herself on to one of the low seats and burst into a passion of tears.

That it should come to this—that she, Peggy Vaughan, who, whatever might be her faults, had always held such an unstained reputation for honour and truthfulness, should be deemed capable of such a mean and discreditable action seemed too hard to be borne. She felt as if she could never explain the matter properly, and that the brand of this horrible affair would remain on her for the rest of her life, bringing disgrace upon the whole family for her sake. She worked herself up nearly to the point of heartbreak when she thought of what Father and Aunt Helen would think about it, and it seemed to her as though the very Crusaders and the lady and gentleman in the Elizabethan ruffs would look at her from their tombs in the church next Sunday with grave disapproval in their eyes.