The Project Gutenberg EBook of Charities and the Commons: The Pittsburgh

Survey, Part II: The Place, by Various

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org/license

Title: Charities and the Commons: The Pittsburgh Survey, Part II: The Place

Author: Various

Release Date: June 18, 2014 [EBook #46025]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK CHARITIES AND THE COMMONS ***

Produced by Richard Tonsing, Barbara Tozier, Bill Tozier

and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at

http://www.pgdp.net

VOL. XXI FEBRUARY 6, 1909 NO. 19

CHARITIES

AND THE COMMONS

THE PITTSBURGH SURVEY

II. THE PLACE AND ITS SOCIAL FORCES

A JOURNAL OF CONSTRUCTIVE PHILANTHROPY

PUBLISHED BY

THE CHARITY ORGANIZATION SOCIETY OF THE CITY OF NEW YORK

Robert W. deForest, President; Otto T. Bannard,

Vice-President; J. P. Morgan, Treasurer; Edward T.

Devine, General Secretary

105 EAST TWENTY-SECOND STREET, NEW YORK 174 ADAMS STREET, CHICAGO

THIS ISSUE TWENTY-FIVE CENTS TWO DOLLARS A YEAR

ENTERED AT THE POST OFFICE, NEW YORK, AS SECOND CLASS MATTER

[Contents Added by Transcriber]

THE COMMON WELFARE

PITTSBURGH SURVEY

PITTSBURGH

A CITY COMING TO ITSELF

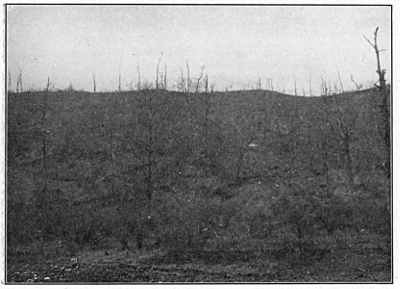

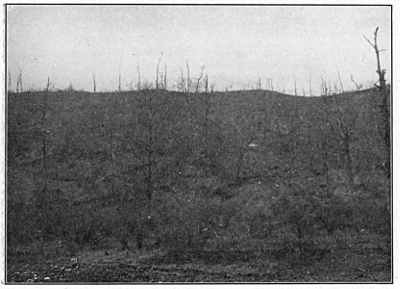

EFFECT OF FORESTS ON ECONOMIC CONDITIONS IN THE PITTSBURGH DISTRICT

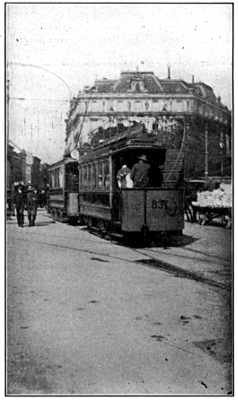

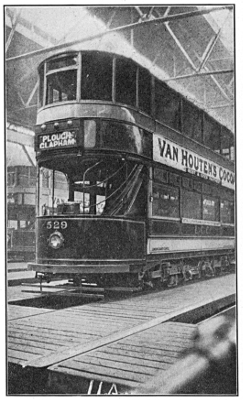

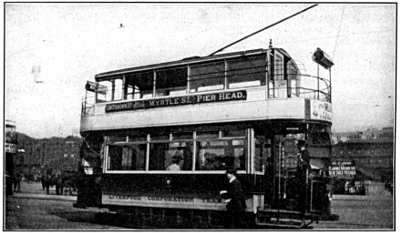

THE TRANSIT SITUATION IN PITTSBURGH

THE ALDERMEN AND THEIR COURTS

THE CHARITIES OF PITTSBURGH

PITTSBURGH'S HOUSING LAWS

PAINTER'S ROW

PAINTER'S ROW

THE MILL TOWN COURTS AND THEIR LODGERS

THIRTY-FIVE YEARS OF TYPHOID

PITTSBURGH'S FOREGONE ASSET, THE PUBLIC HEALTH

|

{ 1646 }

Telephones { } Stuyvesant

{ 1647 }

Millard & Company

Stationers and Printers

12 East 16th Street

(Bet. Fifth Ave. & Union Square)

New York

ENGRAVING

LITHOGRAPHING

BLANK BOOK MAKING

CATALOG AND PAMPHLET WORK

AT REASONABLE PRICES

|

The....

Sheltering Arms

William R. Peters President

92 William Street

Herman C. Von Post Secretary

32 West 57th Street

Charles W. Maury Treasurer

504 West 129th Street

OBJECTS OF THE ASSOCIATION

"The Sheltering Arms" was opened October 6th, 1864, and

receives children between six and ten years of age, for whom no other

institution provides.

Children placed at "The Sheltering Arms" are not surrendered

to the Institution, but are held subject to the order of parents or

guardians.

The children attend the neighboring public school. The older boys and

girls are trained to household and other work.

Application for admission should be addressed to Miss

Richmond, at "The Sheltering Arms," 129th Street, corner

Amsterdam Avenue.

|

|

Wm. F. Fell Co.

PRINTERS

1220 Sansom Street

PHILADELPHIA

Book and Mercantile Printing

Specialists in Medical, Technical

and Educational Work

Illustrated Catalogues, Reports

and Booklets

Machine Composition, Electrotyping

and Binding

|

Trade Marks

have been used from time immemorial by manufacturers, emblems by

societies, seals by kings, artists and printers.

Their works are known to be excellent or poor. Their mark impresses the

quality on the mind.

The Kalkhoff Company

251 William Street, New York

Printers of the Inserts Herein

|

Please mention Charities and The Commons when writing to

advertisers.

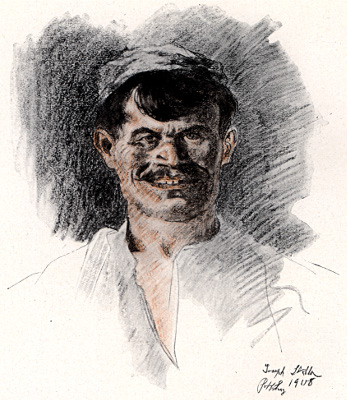

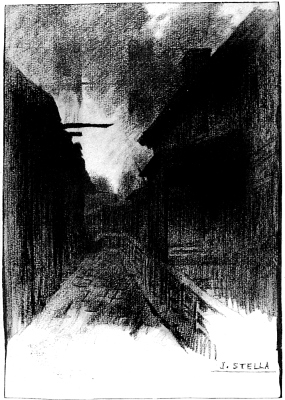

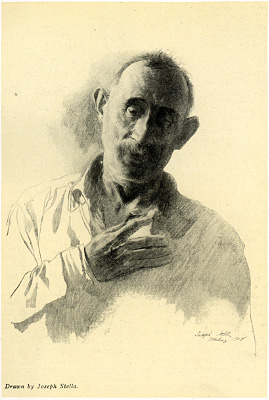

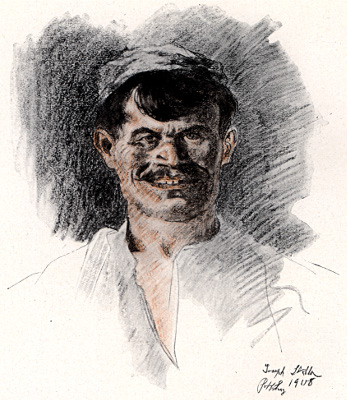

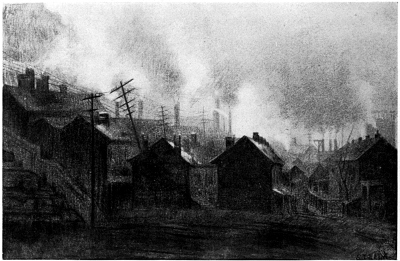

Drawn by Joseph Stella.

AS MEN SEE AMERICA. II.

THE SECOND OF THREE FRONTISPIECES.

Charities

AND The Commons

[Pg 769]

THE BILL FOR A CHILDREN'S BUREAU

An unusually well managed and effective hearing before the House of

Representatives committee on expenditures in the Interior Department

was held in Washington on January 27, following the White House

Conference on Dependent Children. No happier practical expression of

the unanimous conclusions of the conference could have been conceived

than this gathering of nearly all the conference leaders, representing

every section of the country and all shades of opinion in dealing with

childhood's problems.

Many persons listened to the unanimous plea that the federal government

should heed the cry of the child and espouse its cause at least to

the extent of providing a children's bureau manned by experts in such

questions as the causes and treatment of orphanage, illegitimacy,

juvenile delinquency, infant mortality, child labor, physical

degeneracy, accidents, and diseases of children, to whom those engaged

in dealing with these problems could direct inquiries for information

based on adequate and authoritative research. The gathering of such

information and its dissemination in bulletins easily understood by

the common people, the making available for all parts of the country

the results of the experience and suggestions of the most favored

parts and of any foreign experience in dealing with problems similar

to our own,—in short just such service as the government now renders

so cheerfully to the farmer though the scientific work of the bureaus

of its well equipped Department of Agriculture is all that the bill

for the children's bureau asks. Upon the question of the propriety,

constitutionality and expediency of the federal government doing this

work there was not and cannot well be a single objection made. For

the first year an appropriation of $51,820 is asked. As was carefully

pointed out by several speakers, much of the work to be done is

partially undertaken and could be done more adequately by existing

governmental agencies such as the Census Bureau whose work would not

be duplicated if we make it the sole business of some one bureau to

bring together in one place and focus on the problems of childhood

the information desired by child helping agencies and to find out

what is needed to stimulate greater efficiency in work for children.

No administrative powers or duties of inspection with respect to

children's institutions or work are proposed or intended to be given to

the federal children's bureau. Therefore only those whose deeds will[Pg 770]

not stand the light of publicity need fear the operations of the bureau

or expect anything but help and stimulus in the better performance of

their service to the public.

All these points were made with singular unanimity and earnestness by

many speakers who were heard by the committee and were seconded by the

still larger number who recorded their names and the societies they

represented as favoring the bureau. The judges of the leading juvenile

courts were present in person, including Judge Lindsey of Denver,

Judge Mack of Chicago, Judge DeLacy of Washington and Judge Feagin

of Montgomery, Ala. Herbert Parsons, who introduced the bill in the

House, and Secretary Lovejoy of the National Child Labor Committee,

which stands sponsor for the bill, conducted the hearing jointly. Miss

Lillian D. Wald, who originally suggested to the National Child Labor

Committee the advisability of such a bureau, made the opening address,

giving in substance the very clear and able argument for its creation

which she had presented the previous evening at the banquet of the

children's conference. She pointed out the universal demand for it in

the following language:

And not only have the twenty-five thousand clergymen and their

congregations shown their desire to participate in furthering

this bill, but organizations of many diverse kinds have assumed

a degree of sponsorship that indicates indisputably how

universal has been its call to enlightened mind and heart. The

national organizations of women's clubs, the consumers' leagues

throughout the country, college and school alumnæ associations,

societies for the promotion of special interests of children,

the various state child labor committees, representing in their

membership and executive committee education, labor, law,

medicine and business, have officially given endorsement. The

press, in literally every section of the country, has given

the measure serious editorial discussion and approval. Not one

dissenting voice has it been possible to discover.

THE NEED AND THE OPPORTUNITY

In speaking of the work which the bureau would do, we quote again from

Miss Wald:

The children's bureau would not merely collect and classify

information but it would be prepared to furnish to every

community in the land information that was needed, diffuse

knowledge that had come through expert study of facts valuable

to the child and to the community. Many extraordinarily

valuable methods have originated in America and have been

seized by communities other than our own as valuable social

discoveries. Other communities have had more or less haphazard

legislation and there is abundant evidence of the desire to

have judicial construction to harmonize and comprehend them.

As matters now are within the United States, many communities

are retarded or hampered by the lack of just such information

and knowledge, which, if the bureau existed, could be readily

available. Some communities within the United States have

been placed in most advantageous positions as regards their

children, because of the accident of the presence of public

spirited individuals in their midst who have grasped the

meaning of the nation's true relation to the children, and

have been responsible for the creation of a public sentiment

which makes high demands. But nowhere in the country does the

government as such, provide information concerning vitally

necessary measures for the children. Evils that are unknown or

that are underestimated have the best chance for undisturbed

existence and extension, and where light is most needed there

is still darkness. Ours is, for instance, the only great nation

which does not know how many children are born and how many die

in each year within its borders; still less do we know how many

die in infancy of preventable diseases; how many blind children

might have seen the light, for one-fourth of the totally blind

need not have been so had the science that has proved this been

made known in even the remotest sections of the country.

At least fifteen states and the District of Columbia were represented

at the hearing. Among the speakers were Edward T. Devine, editor of

Charities and The Commons, who pointed out the scope and

importance of the inquiries the bureau would undertake; Dr. Samuel

McCune Lindsay, who drew the bill for the national committee and

explained its fiscal features and the plan for the organization of the

work of the bureau; Jane Addams, who showed the real service the bureau

would render the practical worker; Florence Kelley, who pointed out

the extent of our present ignorance on the questions with which the

bureau would deal; Homer Folks, who emphasized the unanimous demand

for the bureau by the widely representative Conference on Dependent

Children; Congressman Bennett of New York, who[Pg 771] showed the service it

would render in dealing with the peculiar problems of the children of

immigrants; Bernard Flexner of Louisville, Hugh F. Fox of the State

Charities Aid Association of New Jersey, Judge Mack, Judge Lindsey,

and Judge Feagin, who all pointed out the service it would render

the courts in dealing with children; Mrs. Ellen Spencer Mussey, who

represented the General Federation of Women's Clubs; Thomas F. Walsh

of Denver, Dr. L. B. Bernstein of New York, William H. Baldwin of

Washington, D. C.; Secretary A. J. McKelway, and General Secretary Owen

R. Lovejoy of the National Child Labor Committee. The House committee

was deeply impressed and it is believed will report the bill favorably.

LOCAL PLAN FOR A CHILDREN'S BUREAU

Realizing that its 20,000 children between the ages of four and

fourteen are its chief asset,—that children are, in fact, as important

as its playgrounds or its streets or any of its other community

problems,—the city of Hartford, Conn., has taken steps towards the

appointment of a juvenile commission which shall relate the work of

schools and playgrounds and manual training and homes and give them

a balance and unity which come only from the consideration of such a

question as a whole. Each of these agencies has an influence on the

child for a part of its life, but each falls short of its possibilities

for lack of such a comprehensive oversight and continuity of purpose as

is promised by the commission.

The measure presented to the Legislature for the creation of a juvenile

commission is based upon the following arguments:

1. Industrial cities are producing a class of children whose

parents cannot, from the very nature of things, do much more

than supply them with food, clothing and a home.

2. The environment of these children, is such, both in the home

and in the neighborhood, that one-sixth die before they are a

year old and one-fourth before they are seven.

3. The parents cannot as individuals provide playgrounds or

adequate discipline.

4. Every child has a right to a reasonable opportunity for

life, health and advantages needed for development.

5. To protect the child's right to a reasonable chance for

healthy development is a special work which should be done by

a commission created for the purpose to supplement the work of

parent and school.

The suggestion for the commission came from George A. Parker,

commissioner of parks, Hartford, and grew out of a meeting of the

Consumers' League, followed by a talk by Dr. Hastings H. Hart. Mr.

Parker's idea met with immediate endorsement from many sources and as a

result the bill now before the Connecticut Legislature has influential

and widespread support.

It is proposed that the Court of Common Council shall refer to the

commission all questions relating to minors and await its report before

taking final action. The commission is to have power to investigate all

questions relating to the welfare of children, to collect and compile

statistics and to recommend legislation. None of its actions is to be

taken in a way to lessen the parents' responsibility and no child is to

be taken from its parent except in extreme cases of danger to life or

limb. The commission as proposed will consist in part of city officials

and in part of citizens who do not hold public office, the members to

serve three years each without salary, but the expenses to be borne by

the city.

EDUCATION AND THE PREVENTION OF DISEASE

The past few years have witnessed an advance in the evolution of

medicine which has been radical and comprehensive.

It was only a decade ago that the efforts of centuries devoted to

empirical treatment of the individual found room for research into the

causes of disease; and it has only been within recent years that such

knowledge has been sufficiently comprehensive to justify its extensive

application in the practical field of disease suppression.

The attempt which Columbia University is making to establish a School

of Sanitary Science and Public Health is prompted by the realization of

the fact that most diseases are preventable with[Pg 772] our present knowledge

of their causes; that the knowledge which we now possess in regard to

their causes is not properly and extensively enough applied for their

prevention; and that this knowledge is best transmitted to the people

by means of educational methods.

Probably the most recent advance in the doctrine of preventive medicine

is due to the fact that many diseases are recognized to have not only

medical, but social and moral causes as well; and that their prevention

is best accomplished by the enlistment of judicious co-operation of

effort in these various fields. For example, a large part of the

disease of the human race is directly traceable to the damaging effects

of alcohol and syphilis, yet these diseases cannot be eradicated until

the underlying social and moral factors are recognized and remedied.

It is not difficult to appreciate the wonderful results which are

capable of accomplishment, with our present scientific knowledge, by

the conjoined application of scientific and social with educational

methods, when we realize that smallpox could be wiped out by education

of the masses on the efficacy of vaccination. The fields of preventable

accidents, dangerous trades, child labor and improvement of working

conditions offer opportunities for the reduction of suffering which are

great almost beyond conception. Blindness could be diminished one-half

by the spread of a simple, well known doctrine; typhoid, cholera,

malaria and yellow fever depart as enlightenment on principles of

sanitary administration creep in, and tuberculosis has resolved itself

largely into a "social" disease.

The problem resolves itself distinctly and emphatically into one of

education; and it is to instruct the teachers of the people in methods

of health preservation,—be they officers of health, with the care of

thousands, or mothers with the care of one, in their keeping,—that

Columbia University is striving to put its school into operation.

Pending such a beginning, a series of university lectures on Sanitary

Science and Public Health by the most eminent authorities of the

country is being given to prepare the way for the next much desired

move,—a permanent, fully-endowed institution of instruction in the

principles of public health preservation and the prevention of disease.

Courses of a similar nature have been organized at Cornell, Wisconsin

and Illinois universities.

The subjects, to be discussed by experts, include water supply and

sewage disposal, health and death rates in cities, public health

problems of municipalities, state and nation, milk supply and infant

mortality, school hygiene, street cleaning, tenement house sanitation,

personal and industrial hygiene and diseases of animals transmissible

to man. The course, which was started on February 1 with a lecture by

Professor Sedgwick of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology on The

Rise and Significance of the Public Health Movement, will be continued

until April 28. The lectures will be open to the public up to the

capacity of the hall.

CLEANING UP THE KANSAS PENITENTIARY

The newspapers of January 31 contained a dispatch describing an unusual

special train that left Lansing, Kansas, bound for McAlester, Vinita

and Atoka, Oklahoma. The 344 passengers, sixteen of them women, were

handcuffed together in pairs and groups and as the train pulled out of

the station, the dispatch states that "a great cheer arose from the

convicts as they saw the last of the state penitentiary."

This special train was carrying away the "boarded out" convicts whom

Oklahoma has been shipping to Kansas since the establishment of its

territorial government. Criminals were aplenty in the old frontier

days and the contract with Kansas was highly agreeable to the settlers

who were glad to free Oklahoma of its "bad men." The territory paid

the state forty cents a day for the maintenance of each convict kept

in the Lansing penitentiary and adding to this the amount that the

prisoners earned, Kansas received about forty-eight cents a day for[Pg 773]

each Oklahoma prisoner. The cost of food was about ten cents a day each.

From time to time stories drifted across the border about the treatment

of prisoners, but not until last year when the territory became a state

and when Kate Barnard became its first commissioner of charities, was

anything done toward cleaning things up in Kansas. In August the new

commissioner went to Lansing as a private citizen of Guthrie, Oklahoma,

and inspected the prison with other visitors. Then she presented her

official card and after considerable protest was allowed to inspect the

jail as commissioner of charities of Oklahoma and the newest state in

the Union proceeded to show her forty-eight-year-old sister what was

going on in the Kansas penitentiary.

Miss Barnard found 562 men and thirteen women prisoners from Oklahoma.

She spent a day crawling through the coal mines where the "props

and supports of the roof were bent low under the weight of the dirt

ceiling." She found that every prisoner who is put to work in the mines

must dig three cars of coal a day or be punished for idleness. Three

cars of coal a day is a good day's work for a strong man. Miss Barnard

found seventeen-year-old boys who were unable to do their "stunt," as

they called it, chained to the walls of their dark cells. She found

"one Oklahoma boy shackled up to the iron wall of the dungeon. The lad

was pale-faced, slender, boyish, and frail in appearance. I said: 'What

are you doing here? Why don't you mind the authorities?' He answered:

'I don't know much about digging coal. I work as hard as I can; but

sometimes the coal is so hard, or there is a cave-in, and it takes time

to build up the walls, and then I just can't get the three cars of

coal. I got over two cars the day they threw me in here.'"

The coal that is taken from the prison mines is used to supply the

Kansas institutions, it is said. About 1,500 tons are mined a day. As

there are some dozen institutions to be supplied, this makes over 100

tons a day for each of the state institutions.

In the prison twine factories the contractors are allowed to say just

how much shall constitute a day's work, and as all men are not equally

skillful, the inferior prisoner is pushed to the limit by fear of

punishment, while the more capable ones fare much better.

Miss Barnard found that the "water cure" is in regular use; that the

"water hole," "where they throw us in and pump water on us" is in

operation; that the "crib" where refractory prisoners are kept with

hands and feet shackled and drawn together at the back, was doing

active service. She found unprintable immoralities existing in some

parts of the mines and she found that since August, 1905, sixty boys

from Oklahoma have been imprisoned with the men in the Lansing prison.

Miss Barnard's report seemed incredible to Governor Haskell. He sent

another investigator who came back to Guthrie with new stories of the

Lansing prison to add to Miss Barnard's.

And then the governor appointed a commission to make a thorough

investigation of the institution and ex-Governor Hoch named a Kansas

commission to co-operate. The latter body made its investigation before

the Oklahoma delegation arrived. It made eighteen recommendations

changing the whole prison management, but declared Miss Barnard's

report true "only in minor details." The Oklahoma commission found that

her report was true to fact and that the Lansing prison was not fit for

a murderer, much less for a sixteen-year-old boy.

There is no state penitentiary in Oklahoma and the prisoners must

be kept in the county jails for the present. This is another strong

argument for the passage of the bill now before the Oklahoma

Legislature for the establishment of a reformatory. It may be possible

to arrange with the Department of Justice to transfer the prisoners to

the United States Penitentiary at Leavenworth.

KOWALIGA SCHOOL DESTROYED BY FIRE

On the afternoon of January 30, the Kowaliga School for Negroes,

located in the high pine lands of Elmore county, Alabama, was destroyed

by fire.[Pg 774] Only two buildings remain of that unique industrial

settlement which has been successfully working among the Negroes of

the surrounding community for thirteen years. The school was started

by William E. Benson, a son of a former slave who had returned to

the Alabama plantation after the war and become one of the South's

most successful Negro farmers. Young Benson was graduated from Howard

University and returning to his father's plantation saw the real

need for a good school for the Negro children of the community. From

Patron's Hall, built by the combined efforts of "the neighbors,"

Kowaliga School was started.

When the five buildings were burned there were 280 pupils and twelve

teachers in attendance. The loss will be about $20,000 with practically

no insurance owing to the extreme difficulty that Negroes always

experience in the South in getting their property covered against loss.

The Kowaliga School is distinct in the service it is rendering to the

community. Its aim is not to train skilled workmen or highly educated

leaders, but rather to properly fit the Negro boys and girls of the

community to live better in that community. The "book work" is carried

as far as the eighth grade. The boys are taught agriculture and manual

training and the girls are trained in the home life which they will

probably take up on leaving school. As the school grew, Mr. Benson

felt that it was not enough to train these boys and girls without

giving them some opportunity to put their training to practical use.

Consequently in 1900 the Dixie Industrial Company was founded "to

improve the economic condition and social environment of the farm

tenants of the South by establishing seasonal industries and furnishing

them with steady employment the year round; to build better homes and

help them to avoid the oppressions of the old system of mortgaging

crops." The company now owns about 10,000 acres of farm and timber

lands, operates a saw-mill, a turpentine still, cotton ginnery,

cotton-seed and fertilizer mill, a store and forty farms, affording

homes and employment for 300 people. It has a paid-up capital of

$66,000, a surplus of $12,000, is earning eight per cent annually, and

paying four per cent annual dividends.

The industrial company provides work the year round for the rural

population and thus fills in the time of the seasonal workers who

before were busy only about half the year.

The fire will not directly affect the Dixie Industrial Company. It will

temporarily cripple the school and until funds are forthcoming that

work must be discontinued. "It means beginning all over again after

thirteen years' work," said Mr. Benson, who was in New York at the time

of the fire; "but I am going back this week and make another start."

REVISING CHICAGO'S CIVIL SERVICE SYSTEM

A complete revision of the civil service system for Chicago is promised

by Elton Lower, president of the City Civil Service Commission. After

eight years' connection with the city departments the commissioner

devoted himself for over a year mainly to studying the working of the

civil service in Boston, New York, Washington and Chicago and to the

examination of the promotional methods used by railway, manufacturing

and other corporations. Securing requisite support from the city

administration, he now announces a complete reversal of the form and

revision of the rules under which the merit system has been operated in

the city.

The distinctive features of the new plan are grading by duties,

descriptive titles, defining the duties of the grades, uniformity of

compensation within each grade, advancement from grade to grade only by

competitive examination, and a greater degree of unity and independence

in the departmental administration of efficiency tests and promotional

procedure within its own bounds. Examinations in all departments and

grades are to subordinate scholastic to practical tests, and to give

greater importance to physical conditions and the investigation of

character in order to meet the requirements of service, rather than

require knowledge of facts. It is hoped to raise the standard of

efficiency and promotion by taking[Pg 775] the tests in each department from

its own system of keeping records and accounts. As the departments

will be held individually responsible for the way they keep these, the

inevitable comparison and contrasts between them will tend to level

their standards up to the highest.

Salaries may be raised only for an entire rank and not for individuals

within the rank. Provision for grouping employes within the grades is

made on the basis of efficiency, seniority or time required by service.

The passing mark will be the only test of physical fitness. A similar

flat-grading is proposed for work requiring skill and experience.

Testing the applicant's qualifications in these respects, as is done

for New York and Boston by the trade schools, is preferred for Chicago.

A free transfer permits employes to pass from one department to another

for promotional examinations, the original entrance examination thus

giving a city employe a slight advantage over outsiders in competing

for grades. Identification tests include finger prints.

The civil service commission began to institute these features

among the employes of its own office some time ago. It first

secured proper quarters and modern sanitary facilities, and then

began training employes for its own work for which experienced

applicants were lacking. Mr. Lower maintains that if such a system is

firmly established and built up it will be likely to withstand lax

administration because "it will take as much study and thought to tear

it down as to construct it." Whatever wrong things may be introduced

into it, he thinks, "will make conditions no worse than they have been

under the system that has hitherto prevailed."

The Chicago Public Library will profit as much by the re-classification

of its force and by this scheme of promotion as any other city

administration, since its work has suffered more for the lack of

finer tests of efficiency within more specialized grades, and also

from being under the same regulations as other departments with whose

requirements its service has little or nothing in common. To have a

civil, self-regulating service system virtually its own, will free its

directors, the librarian and his staff for that initiative which will

give to this fourth largest library in the United States the leadership

which may be rightly demanded for it.

ANOTHER ATTEMPT FOR A NEW CHICAGO CHARTER

The Chicago Charter Convention reassembled last week at its own

initiative to renew its attempt to prepare a city charter that the

Legislature will adopt and the people will accept at the polls. Its

first laborious effort was so ruthlessly made over by the contending

party factions in the Legislature two years ago that the measure suited

no one. Many members of the convention repudiated it and the people

overwhelmingly rejected it at the polls. To conserve their hard and

fundamental work, the convention ventured to reassemble last autumn and

appointed a committee to revise its own bill in the light of its fate

at the capitol and the polls. In so doing the amendments made by the

Legislature have been carefully considered and most of them eliminated.

The measure thus nearly restored to its original form has been changed

to conform to suggestions prompted by the criticisms and discussions

through which the bill and act passed. This revision is now to come

before the convention which faces many interesting and strenuously

contested issues. Among them are the limiting of the city's bonded

indebtedness to four per cent, the assumption by the city of ten per

cent more of the cost of public improvements, municipal suffrage for

women, stringent provisions against corrupt practices, the retention

of the party circle on the ballot, the local regulation of the liquor

traffic and the Sunday closing of saloons, the centralizing of school

management, and the consolidation of four park boards.

Preliminary to all these issues the question is to be decided whether

the convention will supersede itself by proposing to the Legislature

either to authorize the election of a new charter commission by the

people, or to call a constitutional convention. These proposals are

not likely to interfere with[Pg 776] the procedure of the present convention

to complete its own charter bill. Notwithstanding the fierce factional

fight that now absorbs the energies of the Legislature so that it has

not yet attempted to attend to public business, one of the prominent

members of the House of Representatives assured the convention that

if it agreed upon a measure and rallied to its support the public

sentiment of Chicago, it would be enacted and referred to the

referendum vote of the people.

THE SCIENCE OF BETTER BIRTH

The scientific foundations for the slowly rising science of "eugenics"

grow apace in the research laboratories of our universities. Some of

their most authoritative representatives demonstrated this fact at

the recent joint meeting of the Physicians' Club of Chicago and the

Chicago Medical Society. In strictly scientific spirit and phrase, with

interesting stereopticon illustrations of their biological experiments,

four professors brought their facts to bear upon the doctors for their

inferences as to the analogy between the heredity in animal and plant

life, and the development of human kind. Two professors of zoology,

Dr. Castle of Harvard and Dr. Tower of the University of Chicago gave

respectively "an experimental study of heredity," and "experiments

and observations on the modification and the control of inheritance."

A beautiful parallel was presented by Dr. Gates, professor of botany

at the University of Chicago, in studies of inheritance in the

evening primrose. Dean Davenport of the College of Agriculture at the

University of Illinois ventured the most direct application of the

suggestions from scientific experimentations to the propagation of the

human race. Drawing the lessons to be learned from the breeding of

animals, he said that the question preliminary to any consideration

of the subject is "whether the end of our breeding is to be the

production of a few superior individuals, or the general elevation of

the race. If it is the first, we must proceed as in the breeding of

thoroughbred race horses; if it is the second, as in the production of

good fat stock for the farm." Preferential mating, he thinks, produces

in the long run, persons of exceptional talent. "Like mates with

like, and people with exceptional ability in any line are naturally

thrown together by their common tastes and thus uniting bring forth

phenomenal individuals in all lines." The solution of the problem of

the deterioration of the stock lies, he thinks, not so much in stricter

marriage laws, as in the absolute prevention of reproduction among "the

culls, human as well as animal." To colonize other classes of the unfit

as strictly as we do the insane is the only way he sees of doing this.

"Let a man be taken into court and his ancestor record investigated.

If we find his parents were dominantly bad, it means that he is fifty

per cent bad. If his grand parents were also bad, he is twenty-five

per cent more bad. When he gets to ninety per cent bad, it is certain

that he must be colonized. There is a strict mathematical law that runs

through it all."

Whatever may be thought of such definite suggestions, it is too true

as the secretary of the Physicians' Club affirms, that "man is at a

distinct disadvantage when compared with domestic animals in being

denied 'good' breeding. He is the child of chance and so to speak is

born, not bred." Surely, however slowly, the science of improving the

propagation of the human race will receive its recognition as having

place among the hierarchy of the sciences and will be practically

applied by those who respect themselves and have any regard for their

posterity.

CONFERENCE ON DENTAL HYGIENE

The Conference on Oral and Dental Hygiene held in Boston recently

brought out, perhaps more than anything else, the relation between, the

physical condition of the teeth and the general health of the body,

and the great necessity for lay intelligence in the matter. Prof.

Irving Fisher of Yale, the opening speaker, dwelt on these points,

and declared that civilized man tries to avoid mastication by the use

of pulverized,[Pg 777] liquified and pappified foods; that civilization has

brought about a pressure of time with the result that we eat by the

quick lunch counter and the clock, whereas the animal eats his meal in

peace; that we eat too fast, to the injury of our teeth, as shown by

the fact that those who do masticate food thoroughly have better teeth;

and that experience shows thorough mastication results in better health

and greater efficiency. Prof. Timothy Leary of Tufts College said

that proper mastication does away with an important source of supply

of putrefactive bacteria, and eliminates conditions favoring gastric

cancer.

Dr. Samuel A. Hopkins believes that the solution of many of the

difficulties lies in seeking out the educators and in working through

them and through the various settlements and the workers in public and

charitable institutions. Of particular importance are all those who

work with children. William H. Allen of New York lays to the ignorance

and the indifference and the carelessness of the public a great many of

the difficulties. He believes that

if hospitals ever refuse to give bed treatment for twelve

weeks to a man suffering from jaw trouble when the dentist

could give "ambulant" treatment while the man supports himself

and his family; if physicians ever stop spending time, money,

medicine and hospital space on tubercular patients who reinfect

themselves whenever food, medicine or saliva pass over their

diseased teeth and gums; if dentists are ever generally added

to the attending, visiting and consulting staffs of hospitals;

if education of dentists for profit ever gives way to education

for health and training; if the dental profession is ever

given the rank with other specialties and society given the

corresponding protection, it will be because laymen intervene.

Dr. Horace Fletcher declared that it is definitely known that the flow

of gastric juices is started in the stomach by psychic stimuli. If the

food is taken without enjoyment the juices are not secreted and the

food remains undigested. "Any dispute at the table, an angry word, a

discussion over a bill, or a sharp retort, are sufficient to stop this

digestive process," he said.

Dr. David D. Scannell of the Boston School Committee made the startling

statement that fully seventy-five per cent of Boston school children

have dental disease, which means that there are about 75,000 school

children in Boston needing attention. Dr. Scannell bases his statement

upon investigations made in Brookline, New York, and through the

district nursing associations. Dr. Scannell said that the present

dental work in schools is done with good intention but it is sporadic.

Money should be set aside for examination and treatment of all school

children, conducted through an out-patient dental department on the

same basis as the eye and ear departments of free treatment.

Dr. Walter B. Cannon of the Harvard Medical School showed the dangers

lurking in school drinking cups. His statements were supplemented in

the exhibit provided by the Dental Hygiene Council of Massachusetts

by pictures showing a filthy vagrant using a public drinking cup,

immediately followed by a mother who gave her little girl a drink from

the same cup.

The exhibit is the only one in existence in this country. It was taken

in part from the tuberculosis exhibit, but has been greatly increased

and supplemented by an exhibit from Strasbourg.

In the closing session, President Eliot of Harvard pointed out

the relation between defective physical conditions and defective

government. "The bad physical condition of our people is due largely

to the unhealthy conditions under which the men do their ordinary

work and the women pursue their domestic employments. To improve the

public health we must have better regulations and laws. We cannot

create and improve the public playgrounds which are open air parlors

without honest and efficient city and town government," he said. Dr.

Eliot thinks that the medical profession is the most altruistic of all

occupations, with the possible exception of the ministry.

INSURANCE AND BUILDING LOANS

One of the defects of the building and loan societies, long recognized

in some quarters, has been the probable loss of the[Pg 778] home to the family

of the member who dies before payment has been completed. At the time

when the widow most needs the home for her children, the payments

cannot be met and the association is reluctantly obliged to foreclose

the mortgage.

A plan to meet this situation, frequent in the aggregate, has been

devised and practised in New England, by requiring the borrower to take

out an insurance policy on the least expensive straight-life plan,

to an amount equal to the mortgage. The insurance premium is payable

monthly with the payment on the loan, the association turning it over

to the insurance company, and undertaking to adjust the payments if

the latter's premium periods do not coincide. The face of the policy

is made payable to the loan association which, in case of death, takes

from the insurance money the amount remaining unpaid on the mortgage,

and gives the widow the balance with a deed for an unencumbered home.

In the great majority of cases where the borrower lives to complete

his payments, the policy is surrendered to him when his mortgage is

cancelled, to be continued or dropped as he pleases.

The plan was described at the annual banquet of the Metropolitan League

of Co-operative Savings and Loan Associations, New York, by J. Q. A.

Brackett, former governor of Massachusetts, who is urging it on a

national scale as a necessary adjunct to what, in his native state, is

termed the co-operative bank.

More than two hundred men attended the banquet, representing

ninety-five constituent companies with 35,129 depositors, and

controlling assets of sixteen million dollars. One who attended

could not fail to be impressed with the evident feeling of these men

that their paramount duty is not to make money for their particular

organizations, but to help the average member buy a home. Ninety per

cent of them are unsalaried. One association, it was reported, has

reduced its interest rate without request of its borrowers. In the

words of the president, the main desire of building loan associations

should be "the encouragement of the habit of saving without irritating

penalties and restrictions and with equitable provision for the mishaps

possible to those undertaking a contract for specific saving extending

over a long period of years."

THE SIGHTLESS AND THEIR WORK

The wonderful gains made by the blind in overcoming their heavy

handicap was brought strikingly to public attention at the second

annual sale and exhibition of the New York Association for the

Blind. Women were at work on small hand looms, on linen looms, and

on carpet-weaving looms. A blind girl operated a power machine.

Stenographers sat at their work, fingering ordinary typewriters, and

transcribing notes from phonographic dictation. There were all the

usual, simpler displays of chair caning, basket weaving and broom

making and there was music, both vocal and instrumental. The guests

were told interesting stories of many of the workers. One was of a

man who applied to the association for help when first stricken blind

and most despondent, thinking that all avenues of usefulness had been

closed to him. As a result of the instruction given to him, he is now

able to earn a good salary and to support his family.

The work of the association has so increased during the past year,

that besides the building on Fifty-ninth street and the workshop on

Forty-second street, the special committee for the prevention of

blindness has an office in the Kennedy Building at 289 Fourth avenue.

In co-operation with the State Department of Health the committee is

working particularly toward the prevention of ophthalmia neonatorum.

Following are the members of the committee: P. Tecumseh Sherman,

chairman, Dr. Eugene H. Porter, Dr. Thomas Darlington, Dr. F. Park

Lewis, Dr. J. Clifton Edgar, Thomas M. Mulry, Dr. John I. Middleton,

Miss Louisa L. Schuyler, Mrs. William B. Rice, Mrs. Edward R. Hewitt,

Miss Winifred Holt, Miss Lillian D. Wald and George A. Hubbell,

executive secretary.

[Pg 779]

BERLIN'S SCHOOL OF PHILANTHROPY

Europe, and especially Germany, follow very closely every new

experiment along social lines, undertaken by American cities or

individuals. One imitation of American methods was the establishment of

separate courts for children, though neither detention homes nor the

splendidly equipped schools for delinquent boys and girls, which the

most progressive states of the Union have, are found in Germany. The

state governments in most cases do not take the initiative; private

citizens study the question and urge the necessity for a change, until

public opinion, thoroughly aroused comes out so strongly in favor of

a new measure, that the authorities are forced to yield. In October,

1908, a social school for women opened its doors in Berlin with the

help of different societies and in co-operation with private citizens,

of whom Dr. Munsterberg is the best known to the readers of this

magazine. A close study of the methods of the New York and Chicago

Schools of Philanthropy had been made and some of their features

successfully copied. The aim of the school is to give German women new

chances for service whether they wish to devote some of their time as

volunteers or desire to become paid officers of philanthropic agencies.

Field practice will show how the same problems, which confront social

workers, repeat themselves only in a smaller way in the families and

individual. To the training in both theory and practice two years are

devoted. The theoretical work in pedagogy, social questions, economics

and domestic science, is supplemented in the first year by kindergarten

and day nursery work, and in the second year by a special training

gained through working at different social agencies, like the Bureau of

Charity, juvenile court committees, relief and aid societies. All these

agencies hope to get a staff of experienced helpers and workers through

their co-operation with the school. The state's schools, through which

the girls have to pass prior to their admission, have very little of

the modern spirit. In contrast too with the great variety of courses

in the state lyzeums, the courses are restricted in number and

carefully selected. They are however most appropriate for women, since

they present not only a picture of the development of modern society,

but emphasize particularly woman's position.

The director, Dr. Alice Salomon, is one of the most able and

conservative leaders of German women. There is a good attendance at the

new school.

THE RUDOWITZ CASE

GRAHAM TAYLOR

The decision of Secretary Root to deny the demand of the Russian

government for the extradition of Christian Rudowitz is a great relief

to all true Americans, and thousands of their foreign born fellow

citizens all over the land. The right of asylum for political refugees

was at stake in the case of this Lutheran Protestant peasant. The

extradition was demanded on the ground that he had been identified

as one of a band of twelve or fifteen marauders who were guilty of

three homicides, arson and robbery in the village of Beren, Courland,

in January, 1906. The defendant denied the charges of personal

participation in the alleged crimes and submitted proof that Courland

was then in a state of temporarily successful insurrection, and that

the killing was ordered by the revolutionary party then in control, as

an execution of spies who had betrayed many of their own people into

the hands of the military authorities by whom they were summarily shot.

The evidence upon which the whole case hinged was in the form of

depositions taken in Russia and submitted by the government to the

United States commissioner at Chicago. So well grounded were the

suspicions with which it was regarded, that the whole record of the

testimony was submitted to John H. Wigmore, dean of the Northwestern

University Law School, one of the highest legal authorities in America,

and author of one of the principal American text books on evidence.

His careful analysis of the voluminous record[Pg 780] in the case led him

to conclude that while Rudowitz was a member of the revolutionary

committee and voted for the execution of the spies, the evidence

identifying him as one of the party charged with the killing "is too

slight to be of any value"; that "there is no evidence of marauding

or neighborhood feuds or common depredation on the part of this or

any other band in any part of the evidence for the prosecution"; that

there is conclusive evidence of a temporarily successful revolution

"giving the military forces of the national government under their

system certain rights of summary execution, and correspondingly giving

such rights to the revolutionists, so as to fix upon their acts of

summary force, if duly authorized by their officers, as revolutionary

acts of force." These facts justified Dean Wigmore in concluding that

"the killing was a purely political act, the arson was also ordered

politically, being a customary incident similar to the existing

government's own punitive practice in such cases."

The suspicions based upon such facts in this and other cases, aroused

the American spirit against the apparent attempt of the Russian

government to secure the extradition of many political refugees on

poorly substantiated charges of being common criminals. Hundreds of men

and women faced the possibility of being forced to change their names

and hide themselves. Great mass meetings were held in the principal

cities to protest not only against the extradition of Rudowitz, but

against the continuation of the present treaty with Russia under which

it was asked. Conservative citizens, to the American manor born, such

as President Cyrus Northrup of the University of Minnesota, W. H.

Huestis of Minneapolis, Charles Cheney Hyde, professor of International

Law at Northwestern University, Councillor W. J. Calhoun of Chicago,

joined their protests with those of recently arrived refugees and such

friends of theirs as Jane Addams, Jenkin Lloyd Jones and Dr. Emil G.

Hirsch. But beneath the value set upon this popular agitation for the

defense of the right of asylum in America, was the confidence that

there was good law under the case for Rudowitz, which would surely

determine the decision of so good a lawyer as the secretary of state.

Now that this confidence has been confirmed, the question is being

validly raised by the press whether the qualifications exacted of

those appointed to United States commissionerships are as high as

was originally demanded for the delicate and difficult duties of

that office. It is pointed out that when in 1793 Congress first

authorized such appointments by the circuit courts, it defined the

qualifications of those eligible as "discreet persons, learned in the

law." Later acts, however, dropped the requirement that they should

be "learned in the law" and continued the reference to "discreet

persons." In substituting "United States commissioners" appointed by

the district courts for the commissioners of the circuit courts in

1896, Congress provided only that no United States marshal, bailiff

or janitor of a building, or certain other federal employes should

hold the office. Some of the most eminent lawyers, who publicly joined

in protesting against the extradition of Rudowitz, took occasion to

criticise the appointment to this office of men not trained in the

law, and inexperienced in the sifting of evidence, whose decisions,

involving the liberty and life of men, must be based entirely upon the

knowledge of the laws of evidence. Certainly this case should lead

either to stricter definition of the qualifications for United States

commissionerships or to far greater care in the appointments to that

important office. Moreover, the injustice of putting upon a political

refugee the burden of proof that he is such has been made manifest in

this case. For to do so Rudowitz would have been compelled not only to

bring his evidence from Russia, but also to expose to certain death

those whom he would have been compelled to name as his compatriots in

the struggle for liberty.

[Pg 781]

SAVINGS BANK LEGISLATION:

WHAT IS NEEDED?

JAMES H. HAMILTON[1]

Headworker of the University Settlement

"Everything speaks for and nothing against the post office savings

bank," writes Professor J. Conrad of the University of Halle. This is

strong testimony from a German economist who is a careful student in

the field of social economics, and who lives in a country which has a

splendid system of municipal savings banks. But if one looks beyond

Prussia and Saxony into the province of Posen he sees great stretches

of neglected territory. And in this country if one looks beyond

Massachusetts, with its much praised trustee savings system, into New

York and Pennsylvania he sees much to be desired,—and if he looks

still further west he finds a sadder neglect than the neglect of free

popular education in darkest Russia.

If we fully comprehend the fact that the savings bank is an

educational, and not a commercial institution we will see at once that

the law of supply and demand cannot properly regulate its growth. We

will see on the contrary that if left to local initiative by either

municipalities or trustees, the banks will likely appear where they are

least needed and fail to appear where they are most needed, and the

need of a general federal system, or a postal system, which will leave

no neglected spots becomes perfectly clear. "Everything speaks for the

post office savings bank."

Postmaster General Meyer, in his article in the August number of the

North American Review, presents this country's need of a postal

savings system in a very attractive and convincing way. I think,

however, that the educational aspects merit more emphasis and more

extended treatment. The public, I think, needs to recognize this

institution not alone as the often successful rival of the saloon,

the enemy of dissipating and destructive spending, but it needs also

to recognize its relationship to the strong type of citizen, with

resisting power against the petty immediate wants in the interest of

greater economic security, the type that can save against the rainy

day, the week of sickness, and the declining powers of the later years

of life.

In my own judgment the highest function of the savings bank is to

lead the workman back to the ownership of his tools, or since that is

not literally possible, to a share in the ownership of the productive

forces of society. The workman may not recognize in the share of stock,

the bond, the equity in a title to real estate, the successor to the

tools his forefather kept stored in his cottage. When he has been

brought to see it and to make such ownership the goal of his ambition,

his tribute of devotion to his wife and children, he will be a stronger

and a better man in every respect, and the multiplication of this kind

of citizen is as worthy an object of education as the spread of a

rudimentary knowledge of letters. Universal proprietorship is no less

desirable, from the social point of view, than universal education. The

purpose of the savings bank is therefore not so much to instill the

idea of hoarding for future spending, but of investing to increase the

permanent income.

Having this in mind the provision of the English postal savings system

for investing in government stocks for the depositor on his request is

fully warranted, and even more so the French provision for investment

of the excess of deposits over the legal maximum in government stocks

without request. The deposit account itself represents investment,—by

trustees on behalf of the depositors. But the depositor should

eventually become a conscious owner on his own account. It would seem

most proper that he be supplied with information which would enable him

to form an independent judgment as to different securities, and the

savings bank might very well act for him in making his first investment.

The one departure from precedent in Mr. Meyer's bill is in the

investment of funds. It contemplates a system of loans to the local

banks with a view to "keeping the money at home." The departure from

the practice of investing in government securities may be good for

the object[Pg 782] intended, which relates to the incidents rather than the

primary object of savings bank administration. It seems to me most

unfortunate that Mr. Meyer should have selected a form of investment

that would tend to defeat the primary object of savings banks in

the necessarily low rate of interest. I think he must fail to fully

realize that the savings bank is to educate the propertyless to become

proprietors, to appreciate the need of supplementing the earnings

of labor by income from accumulated capital, and not to serve as a

mere place for hoarding. It is the interest rate that tickles this

dormant sense into life. It seems to me a pity that he did not see in

the example of the municipal savings banks in Germany and of our own

trustee banks, which invest chiefly in real estate mortgages, a way

of reaching the one object without injury to the other. This would be

a departure from the general practice of postal savings systems which

would at once "keep the money at home," and insure a higher rate of

interest than the yield of government securities. Money thus invested

would get back into the channels of trade as readily as if it were

loaned to the local banks, and with much less objection, and the rate

of interest would probably be about double. The yield should be four

per cent against the two per cent proposed by the postmaster general's

measure.

It is certainly most refreshing and encouraging to listen to the

promise of legislation that extends its benefits immediately to the

common people, which contains the hope of more social solidarity. A

comparison of our policies with those of old world countries in this

respect is not comforting to our patriotic pride. It seems time that we

were less laggard and that we should have more courage to experiment.

The promise made by all political parties of a postal savings bank

is probably the most encouraging sign we have had. It would be much

more encouraging if the measure that is promised contained more of

the results of bold experiment in other countries and contained

more of an original and experimental nature that promises a more

pronounced application of the true principle of savings banks, and

that fosters a clearer popular understanding of that principle. It is

equally important that the principle be brought out in clear relief

from the point of view of the administration and of the patrons. The

administration needs clearly to understand that it is not conducting

a banking business but giving education in thrift, and the youthful

and other patrons need to understand that they are being led in the

direction of economic independence.

SOCIAL EDUCATION[2]

Reviewed by HELEN F. GREENE

It is a long look forward and a wide one that Dr. Colin A. Scott takes

in Social Education and one that social workers other than the teachers

for whom the book was primarily written, will find themselves enriched

by sharing.

The school as a special organ of a constantly changing social order,

must itself be easily capable of change. Instead of the uniformity on

which the clan and early religions insisted must come the great variety

of characters and capacities which the modern highly differentiated

state demands.

How shall the school, called into existence by society for its own

service and protection, most effectively educate the formers of the

"New Society"?

Turning to real life for an answer we find that "society at its best

organizes itself in groups in which each individual in the various

groups to which he may belong finds himself in contact with others

whose weakness he supplements or whose greater powers he depends upon."

"If the school is to prepare for society as it is, it would be natural

to expect that some such form of social activity, however embryonic,

should be found as a necessary feature of its life." "The group must be

capable of going to pieces, a thing it cannot do if it is to depend on

the authoritative backing or constraint of the teacher. Indeed it is

only when it can go to pieces that there is any reality in the effort

to hold it together." "True responsibility and even obedience [Pg 783]of the

highest type is felt only when the group is free."

The positive view of liberty and independence is urged, not

the negative one which teachers,—and he might have added club

leaders,—are too prone to take. "If children are to be trained

socially, they must feel the full effects of social causes,—not merely

of society at large, but especially those of the embryonic society

of child life to which they belong. They must study these effects

practically, and must see to what extent, as social beings, they are

real causes themselves. It is on a basis of experience of this kind

that they can best interpret the larger and more complex life of adult

society and the state."

Declaring social serviceableness and the highest development of

personality "to be the aims of the school, he urges that there shall be

some test of its success in securing these." "This test can be found

only in the extent to which pupils, when freed from the oversight and

benevolent coercion of the teacher, can use the knowledge and carry out

the habits and ideals which it is the aim of the school to foster and

protect."

In the three succeeding chapters, three types of school in which the

social spirit has been specially manifest are criticized according to

this test. The schools are: (1) Abbotsholme, the "monarchy," under the

principalship of Dr. Cecil Reddie; (2) The George Junior Republic; (3)

The Dewey School.

In each he finds "elements of a high degree of social value, and an

approximate solution of the problem of educative social organization."

But it is in the two following chapters on Organized Group Work,

fragments of which appeared in the Social Education Quarterly of

March, 1907, that Dr. Scott makes his own most valuable contribution

to the problem. It is an attempt to show how it is possible, "even

with crowded classes and without special equipment, to obtain in the

people's schools, those co-operative and self-sustaining motives which

are worthy of democracy and best able to measure the teachers' work."

The experiences which he describes he calls "experiments simply in the

sense that all life is experimental, and they were devised with the

view that the development of intention and resourcefulness on the part

of the pupil is the greatest and most undeniable duty of any form of

education."

The method was as follows: Each teacher said to her class: "If you had

time given to you for something that you enjoy doing, and that you

think worth while, what should you choose to do?

"When you have decided how you would spend the time, come and tell me

about your plan. You may come all together, or in groups, or each by

himself; but whatever you say you want to do, you must tell the length

of time you will need to finish it, and how you expect to do it."

A most varied and interesting set of plans resulted. A printing group;

cooking groups; groups for bookbinding; many for the writing and giving

of plays, suggestive of the festival work of the Ethical Culture

School, which has already been so helpful to club leaders.

The history of these groups, their human and humorous experiences:—of

the child who was "bossy" and the way in which the group handled

her,—are given in delightful detail and carry conviction with them as

to the worth of the method.

To one judging socially and not pedagogically the closing chapter on

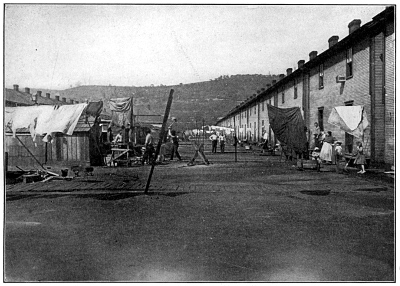

The Education of the Conscience is disappointing. It seems to keep

too much to the idea of personal morality as an end rather than as a

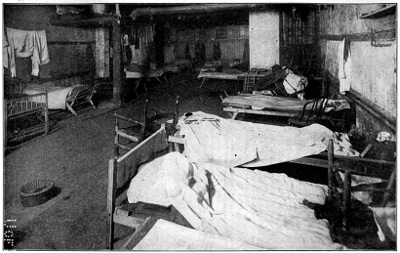

means to the more vital and individually inspiring and healthful social

morality; and to admit of the implication that the moral side of school

life is a thing at least a little apart, rather than finding, when

given a teacher with the right spirit, that, to quote Dr. Dewey, "every

incident of school life is pregnant with ethical life."

[Pg 784]

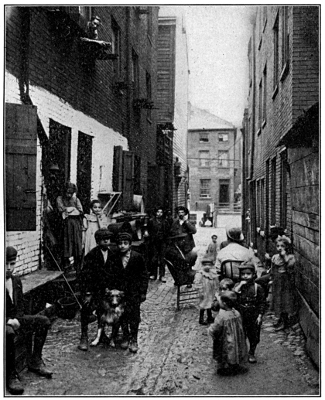

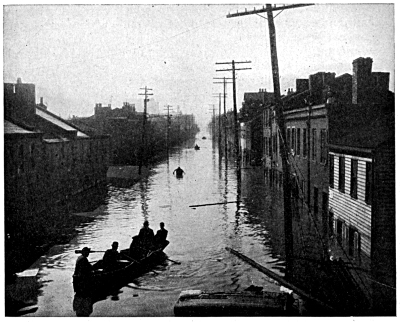

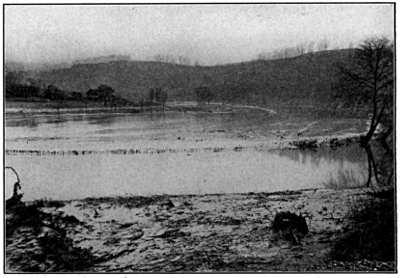

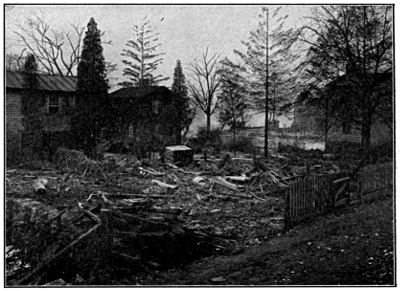

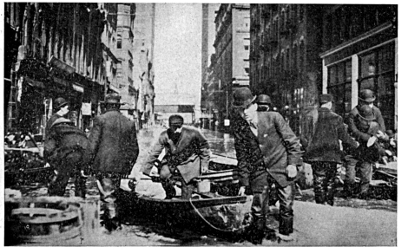

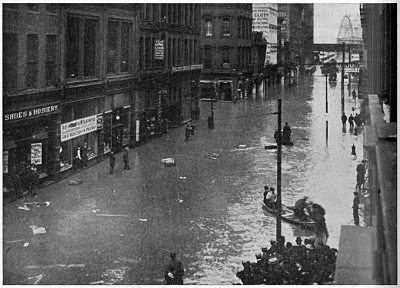

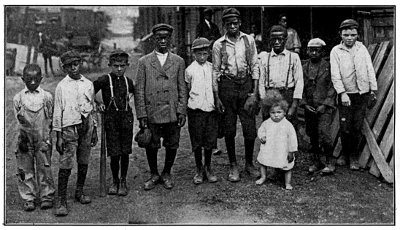

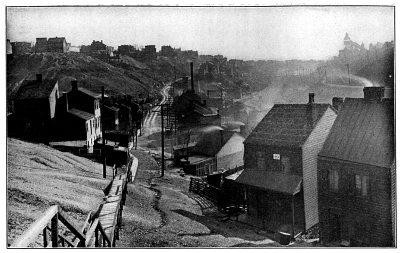

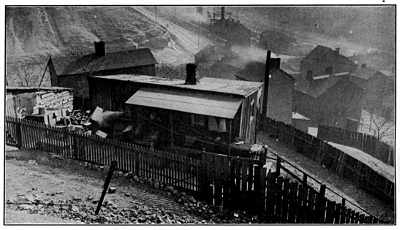

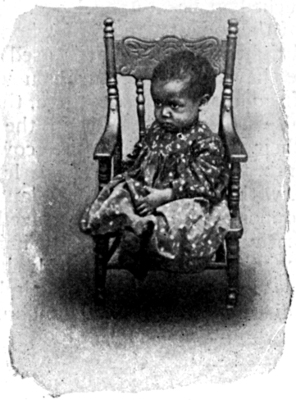

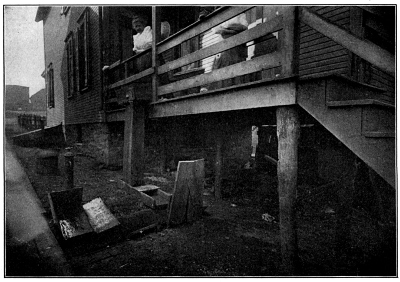

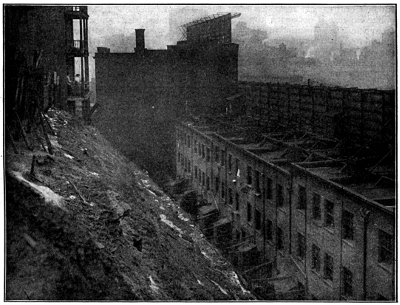

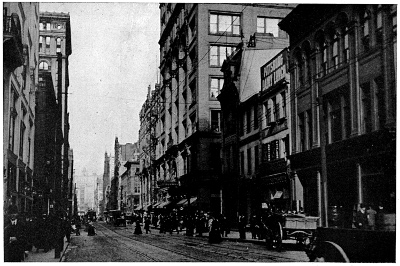

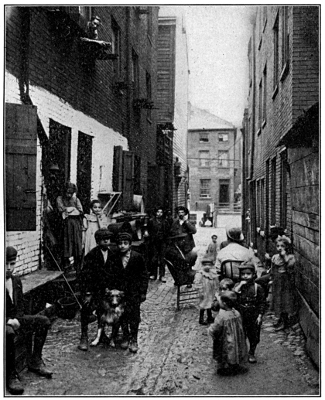

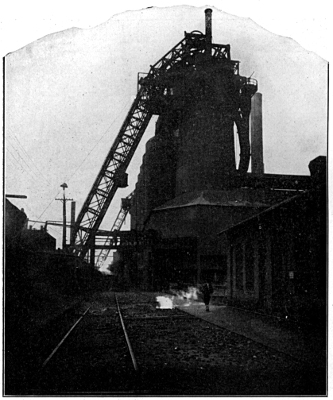

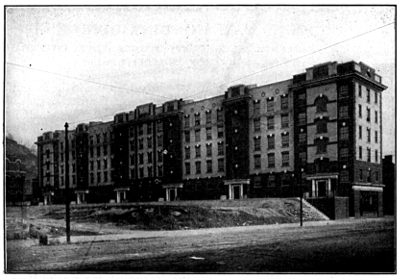

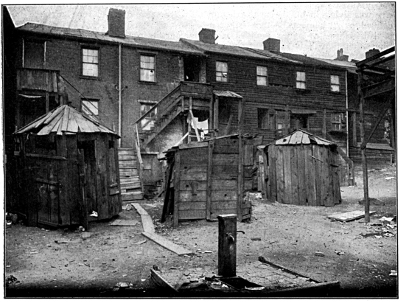

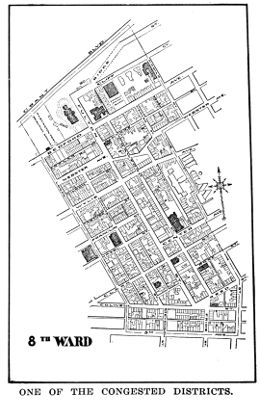

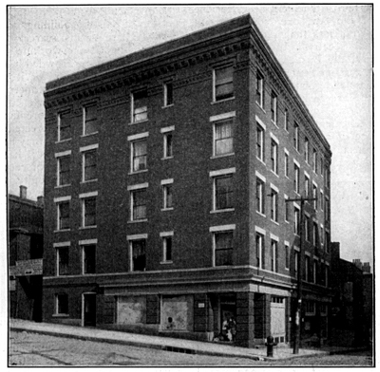

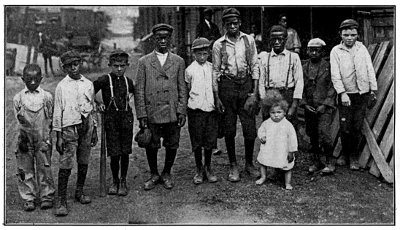

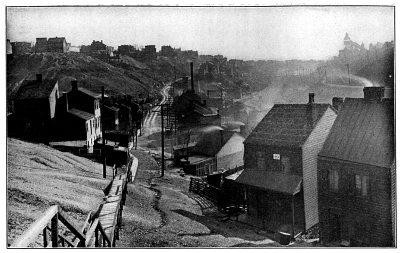

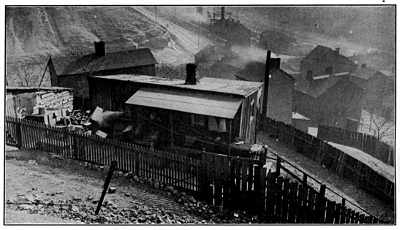

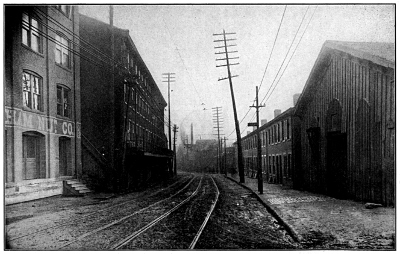

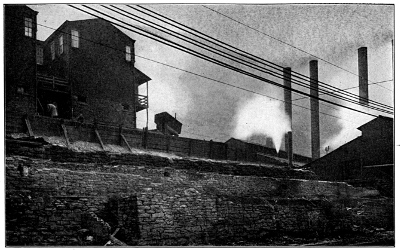

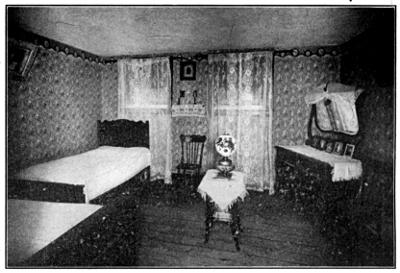

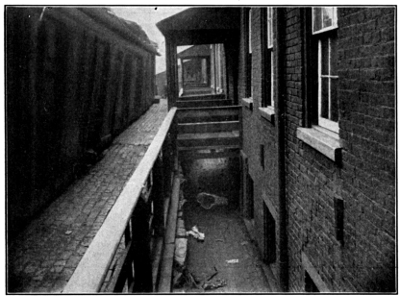

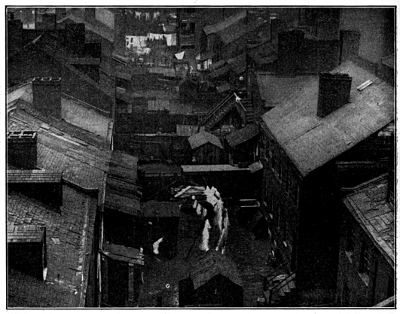

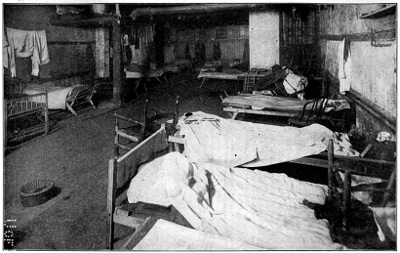

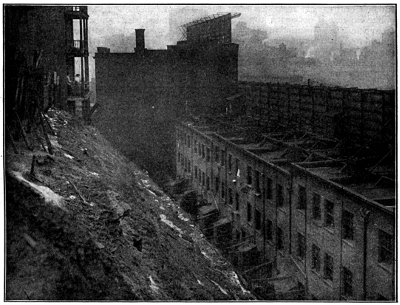

This second Pittsburgh issue deals with certain physical necessities of

a wage earning population. It shows a city struggling for the things

which primitive men have ready to hand,—clear air, clean water, pure

foods, shelter and a foothold of earth. Thus we have in Pittsburgh a

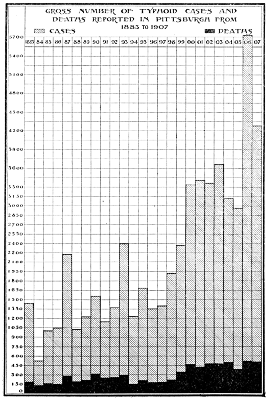

smoke campaign, a typhoid movement and the administrative problems of

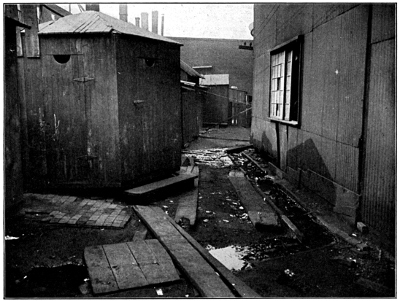

the Bureau of Health in milk and meat inspection; thus we have the

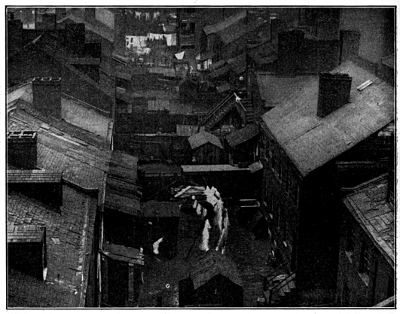

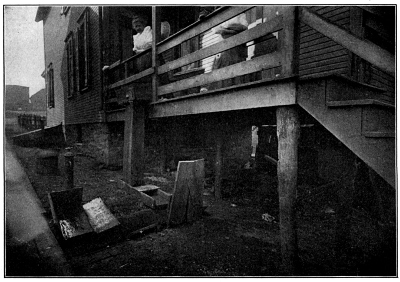

necessity for sanitary regulation of dwellings wherever people live

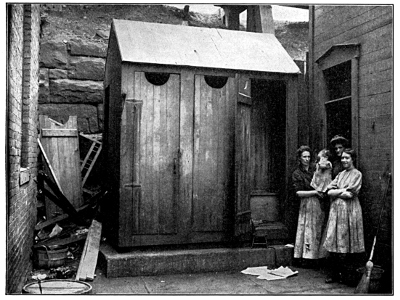

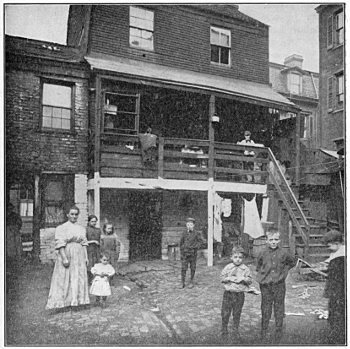

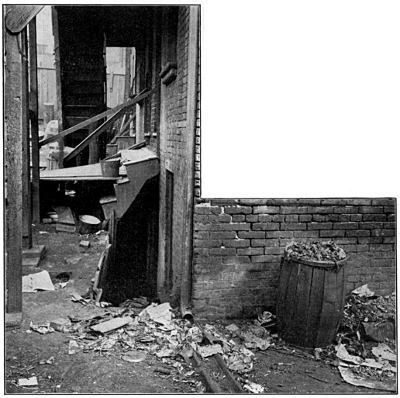

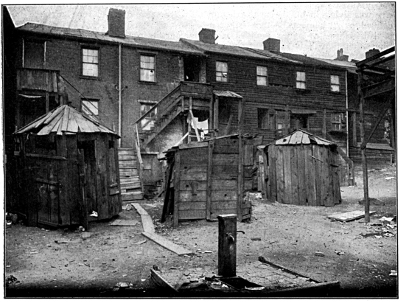

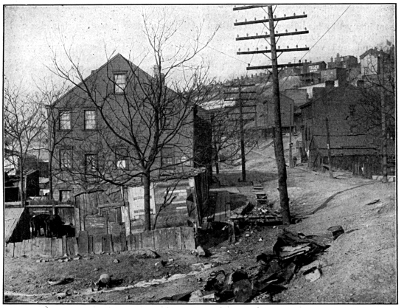

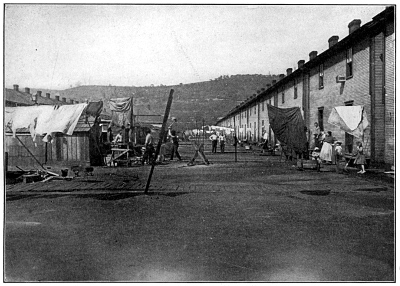

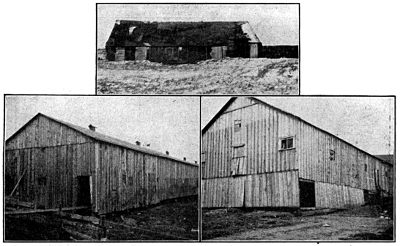

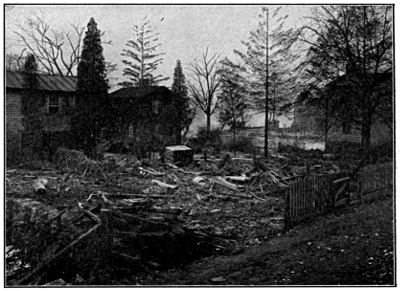

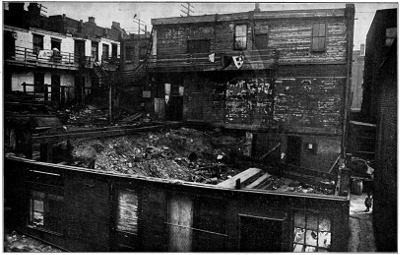

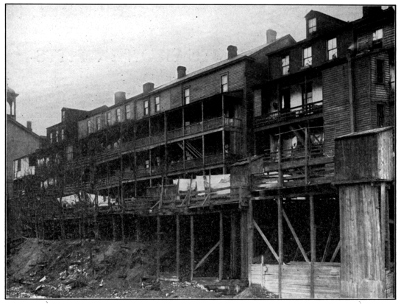

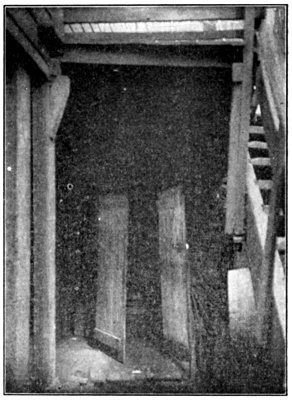

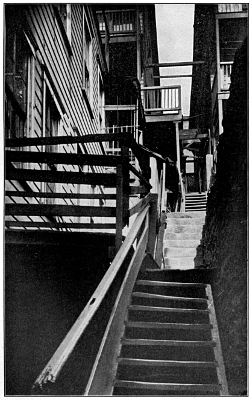

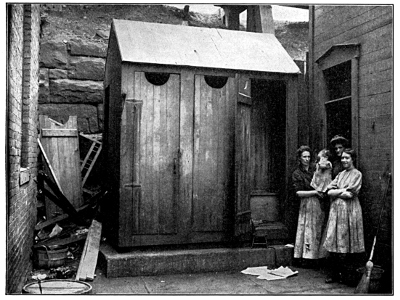

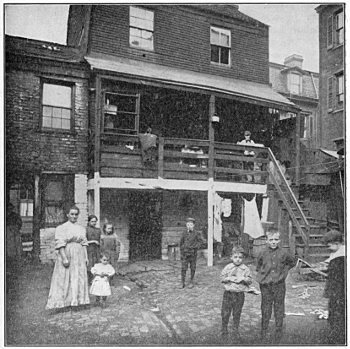

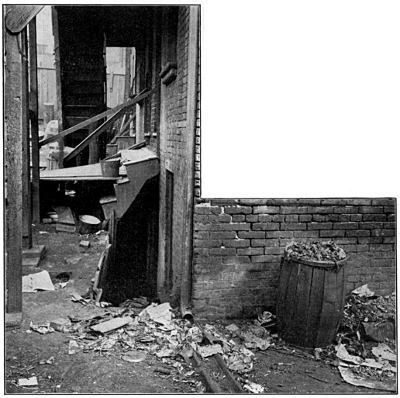

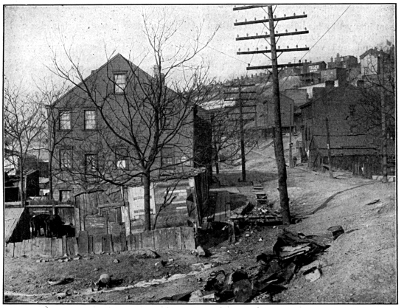

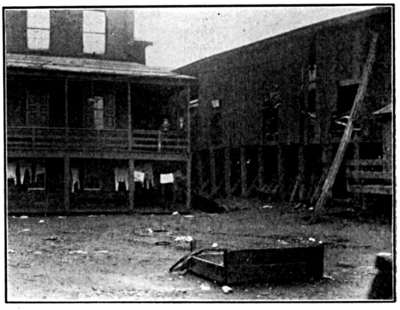

dense or deep, whether squatters' shanties such as those of Skunk

Hollow or company houses such as those of Painter's Row, whether

city tenements or mill-town lodgings; and the necessity further for

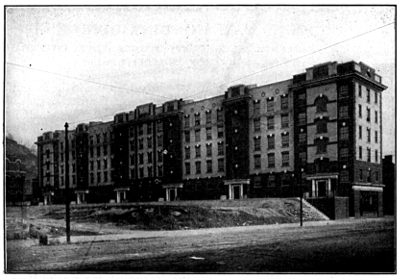

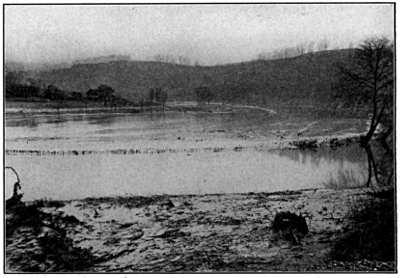

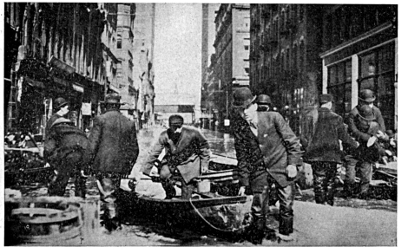

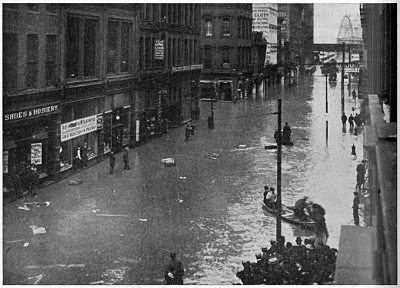

increased numbers of low-cost dwellings. Similarly, flood prevention,

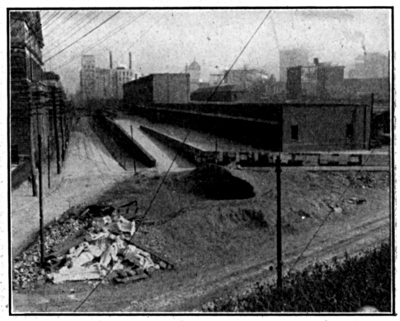

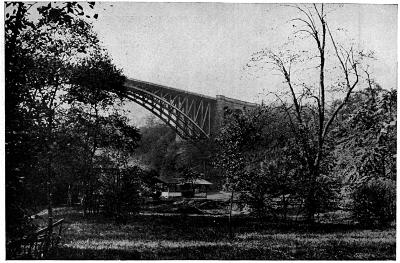

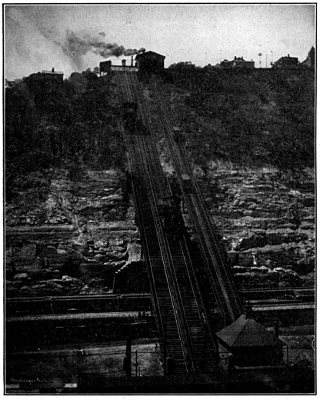

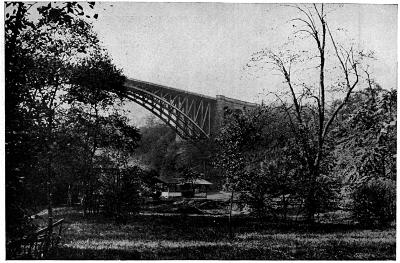

traction development, bridge building and the like are so many efforts

to expand, or conquer the difficulties of, the town's corrugated floor.

The first issue of this series, that of January 2, pointed out

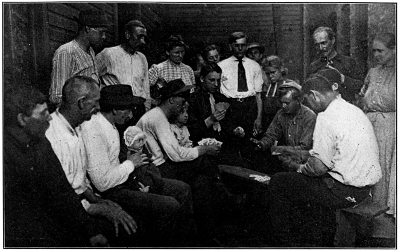

that with the moving into Pittsburgh of new and immigrant peoples,

the spirit of the frontier and of the mining camp possessed the

wage-earning population. This spirit has characterized civic

development. Wherever there has been profit in public service, private

enterprises have staked their claims to perform it. While the biggest

men of the community have made steel, other men have built water

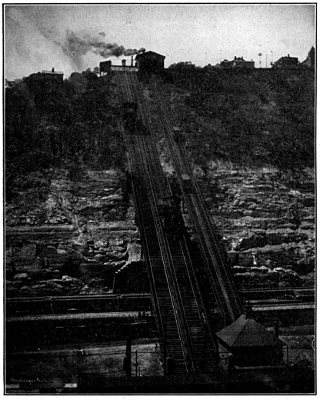

companies, thrown bridges across the rivers, erected inclines and laid

sectional car lines. To bring system and larger public utility out of

these heterogeneous units, has become the present governmental problem

of the city.

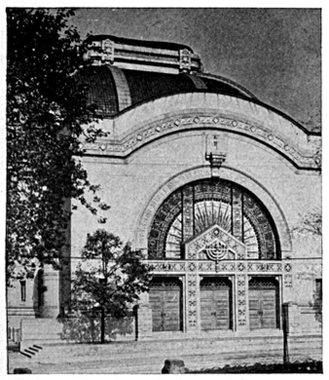

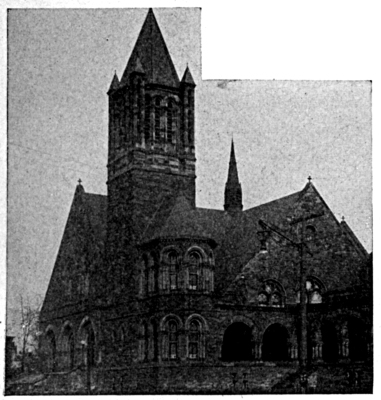

In a sense, this situation is repeated with respect to the institutions

transplanted into Pittsburgh, or initiated there, to meet the cultural

and social needs of the community. Thus we have local alderman's

courts, unco-ordinated charitable enterprises, and a ward system

of schools. The trend of the decade here, too, is obviously toward

system,—toward a municipalization of lower courts, an expansion of the

health service, an association of charities, a city system as against

a vestry system of schools, a civic improvement commission that will

focalize public sentiment in all movements for municipal improvement.

In the third and final issue of the series, that of March 2, the

emphasis will be transferred from the civic to the industrial

well-being of the wage-earning population,—the vital and irrepressible

issues of hours, wages, factory inspection, accidents and the cost of

living.

A supplementary group of studies,—of the libraries, schools,

playgrounds and children's institutions of Pittsburgh,—will also be

published in the issue of March 2.

PITTSBURGH

THE PLACE AND ITS SOCIAL FORCES.

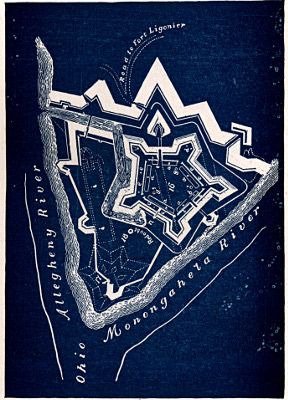

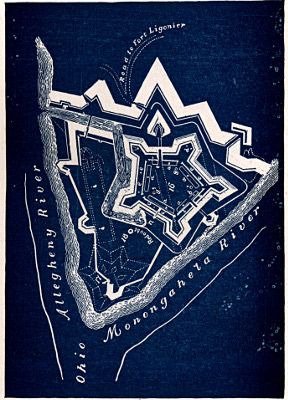

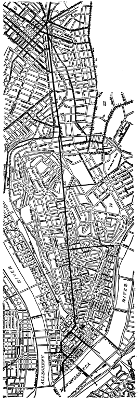

FORT PITT IN 1759.

The first town plan of the Point of Pittsburgh.

The second of three special issues of Charities and The Commons,

presenting the gist of the findings of the Pittsburgh Survey, as to

conditions of life and labor among the wage-earning population of the

Pennsylvania Steel District.

I. JANUARY 2-THE PEOPLE. II. FEBRUARY 6-THE PLACE. III. MARCH 2-THE WORK.

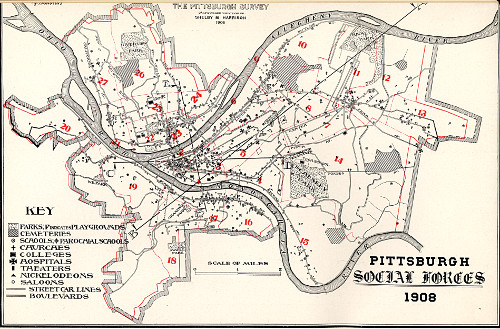

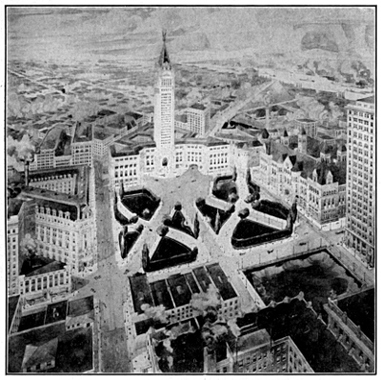

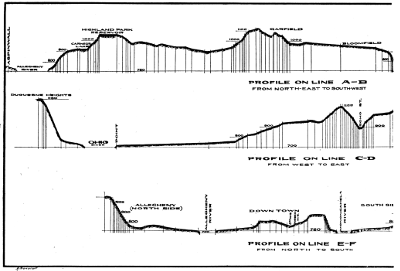

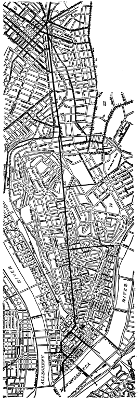

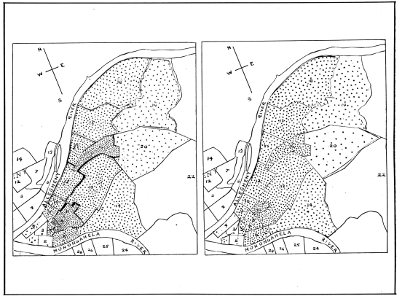

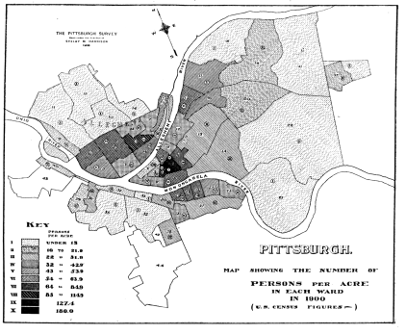

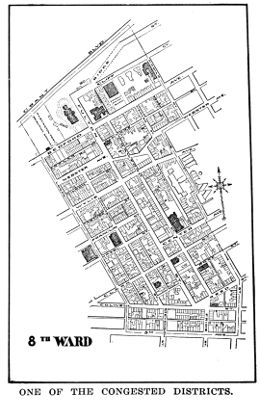

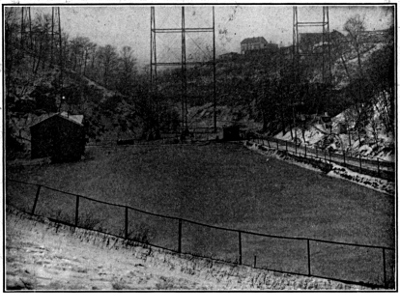

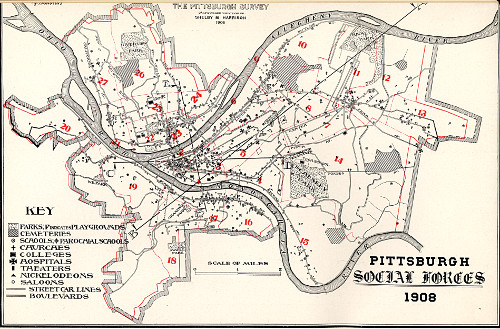

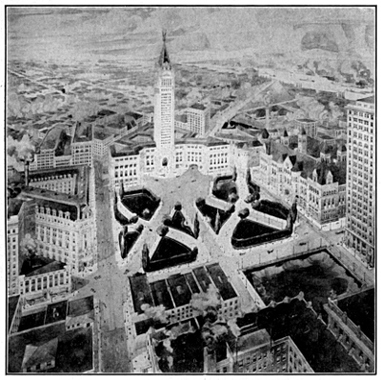

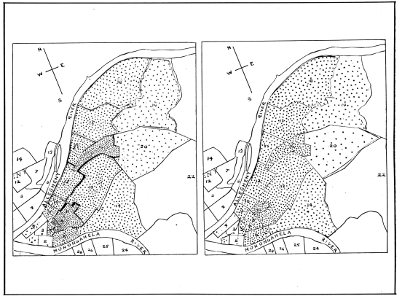

PITTSBURGH SOCIAL FORCES 1908

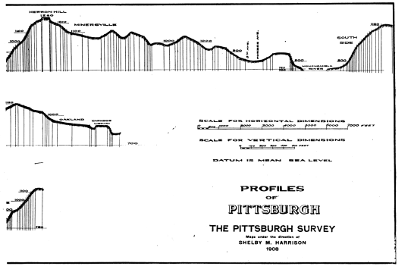

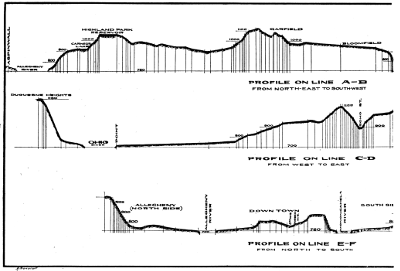

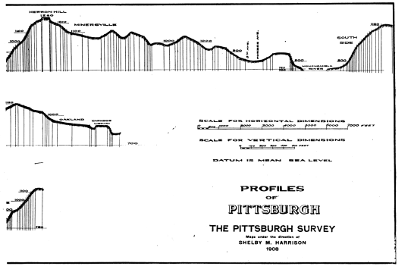

For profiles, lines A.-B.; C.-D.; and E.-F.—see pages 834 and 835.

ROBERT A. WOODS

HEAD OF SOUTH END HOUSE, BOSTON

[Pg 785]

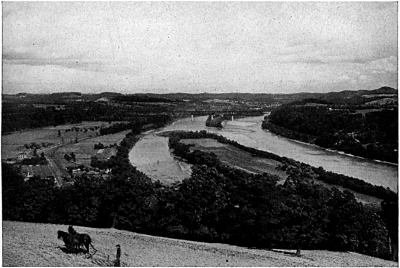

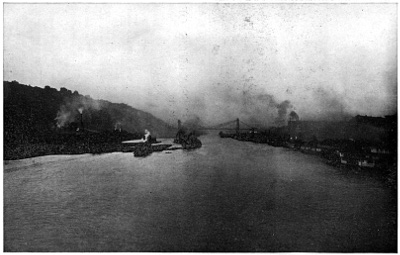

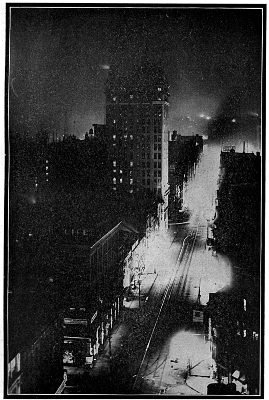

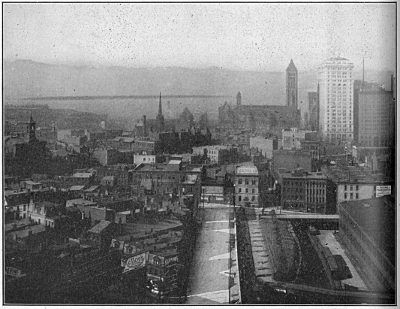

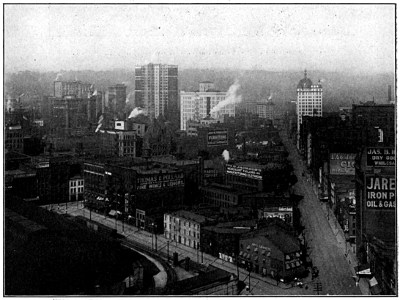

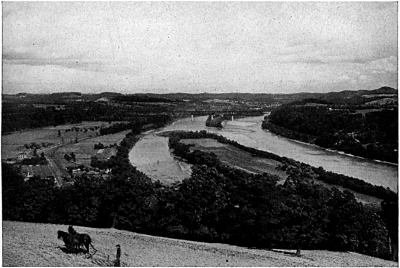

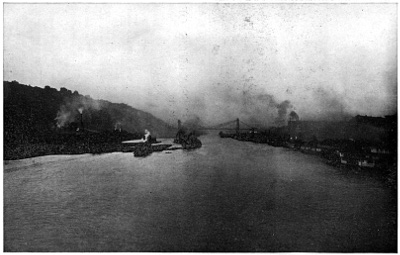

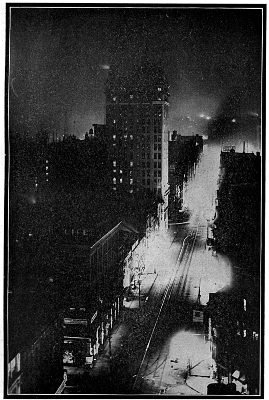

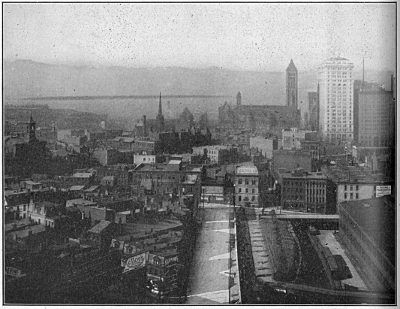

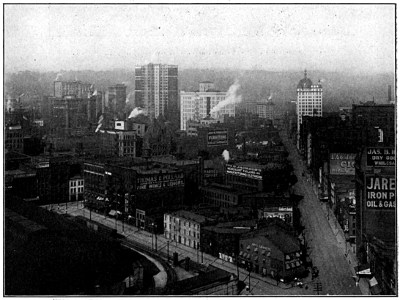

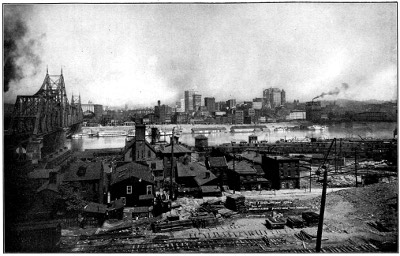

The capacity for being seen with the eye in the large, which New

York in her sky scrapers has purchased at so great a price, is the

birthright of Pittsburgh. Where from so many different points one sees

the involved panorama of the rivers, the various long ascents and steep

bluffs, the visible signs everywhere of movement, of immense forces at

work,—the pillars of smoke by day, and at night the pillars of fire

against the background of hillsides strewn with jets of light,—one

comes to have the convincing sense of a city which in its ensemble is

quite as real a thing as are the separate forces which go to make it up.

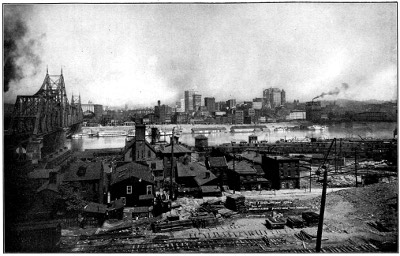

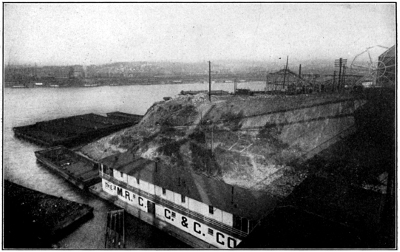

The Allegheny River, providing a broad, open space up and down and

across which much of this drama of modern world industry may be viewed,

has at last come to mean not separation but identity of the population

on either side of it. If the banks of the river were improved, it

might easily be sentimentally as well as economically one of the most

important common possessions of the old and the new sections of Greater

Pittsburgh.

This tendency of cities to reach out and include their present

suburbs, and even the territory where their future suburbs are to

be,—a tendency which a few years ago was mocked at,—is in these

days seen to be normal and wise. The proper planning of the city's

layout, the proper adjustment of civic stress upon the different

types of people in a great urban community, demand the inclusion of

the suburbs. Greater Pittsburgh is less satisfactory than Greater New

York and Greater Chicago, only because it is less inclusive than they.

Some important suburbs of old Pittsburgh are not included, and the

suburbs of Allegheny are nearly all outside. The latter omission is

particularly unfortunate as it is doubtful whether Allegheny by itself

will raise the average civic and moral standard of the greater city.

It is regrettable too that Allegheny continues to show reluctance in

making common cause with her larger neighbor. The toll bridges and the

many obstacles against making them free, seem to typify the difficulty

of intercommunication. The two towns, however, so clearly belong

together that this feeling of clan cannot long survive. From nearly

every commercial point of view that is worth considering Allegheny is

dependent upon Pittsburgh. In the few exceptional instances, as in the

case of two or three large stores, Pittsburgh recognizes a measure of

dependence upon Allegheny. It is interesting that those of the old

families connected with Pittsburgh industries who still insist on

having town houses, reside on the Allegheny parks or commons.

A strong sense of corporate individuality comes to any community that

is arrested by the challenge of great tasks. One of the influences

leading to the creation of the greater city was the widening of the

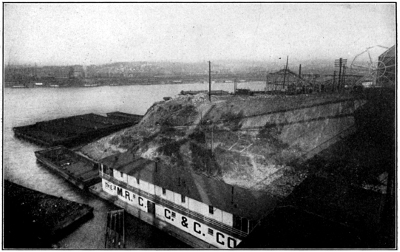

territory administered industrially from Pittsburgh. The best oil wells

are now south rather than north of Pittsburgh, and the center of the

coal regions is fast passing from the southeast to southwest and on

into West Virginia. The necessity of easy transfer of iron ore from

the Superior region is bringing up insistently the proposal of a canal

to Lake Erie, so as to match some of Cleveland's special advantages.

The nine-foot channel for the whole length of the Ohio will enable

Pittsburgh's long arm to reach out and touch that of Cincinnati.

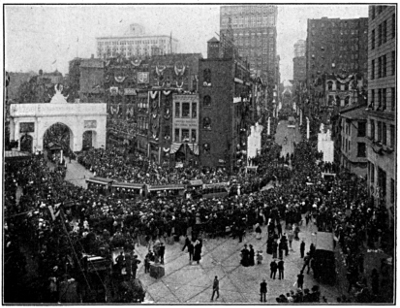

That the expansion of Pittsburgh was preceded and to some extent

directed by a reform administration, has tended greatly to re-enforce

the belief that Pittsburgh is moving organically toward the better

day in her public affairs. This is the first successful movement for

municipal reform in a generation. As I pointed out in my first article,

it got its immediate stimulus out of the impudent interference of the

state machine in[Pg 786] unseating a mayor who had been elected by an opposing

local faction, and setting up a "recorder" in his place. Carried out

under the forms of legislation, this act stung Pittsburgh people into

a new feeling of municipal self-respect and led to their electing on

a Democratic ticket George W. Guthrie, who had been for many years

actively interested in the cause of municipal reform. Mr. Guthrie's

family, like the Quincys of Boston, has been represented for three

generations in the office of mayor.

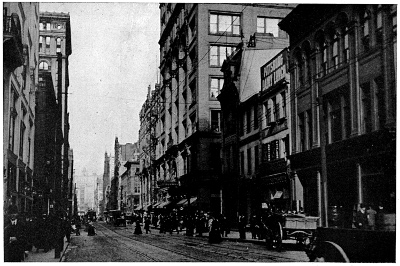

Mayor Guthrie has made thorough application of the principles of civil

service reform. He has introduced business methods in the awarding

of all contracts, including the banking of the city's funds. In a

city where only a few years ago perpetual franchises were given to a

street railway covering every section, Mayor Guthrie has, so far as

the situation allowed, put in force the strictest new conception of

the public interest in relation to public service corporations. He

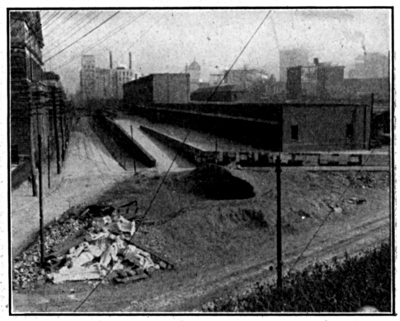

compelled the Pennsylvania Railroad to cease moving its trains through

the middle of what is potentially the best downtown street in the city.

The street railway company was required for the first time to clean and

repair the streets, to meet the cost of changes required by the work of

city departments, and to pay bridge tolls. Loose and costly business

methods in the city departments were radically checked, and accounts

with long arrearages involving heavy interest losses to the city, were

brought up to date. The cost of electric lighting to the city has been

reduced from ninety-six to seventy-two dollars a lamp. Economies have

been effected through having the city do some of its own asphalt paving

and water-pipe laying.

Along with economical departmental service have gone the intelligent

and effective efforts, which will be explained in other survey reports,

for improving the water supply, abating the smoke nuisance, combating

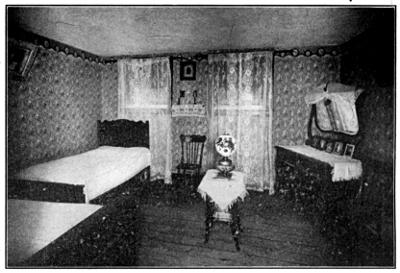

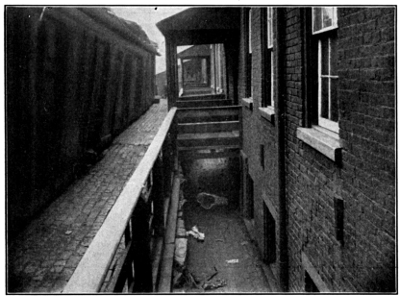

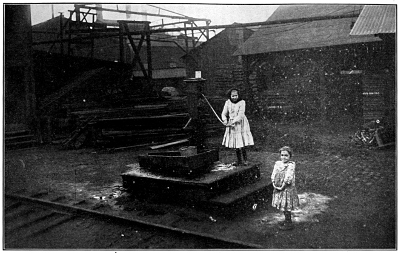

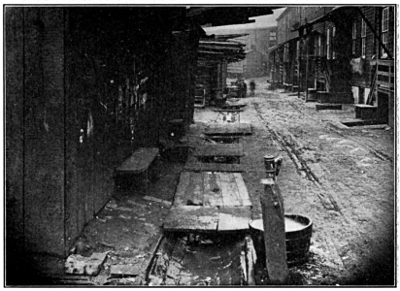

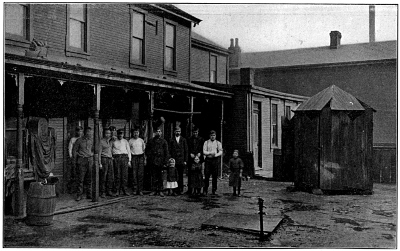

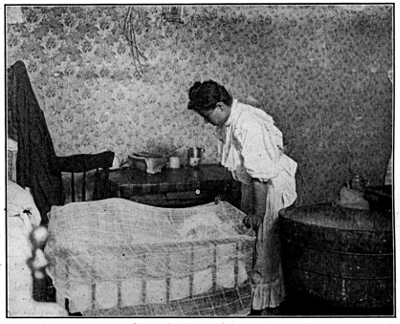

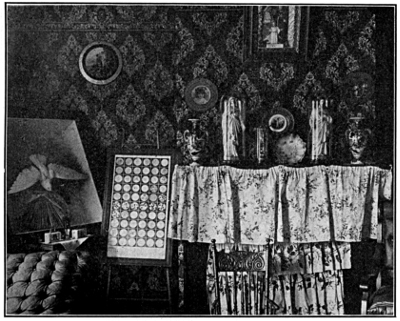

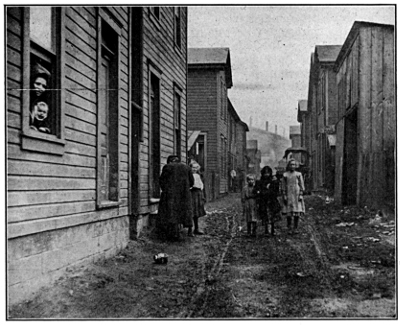

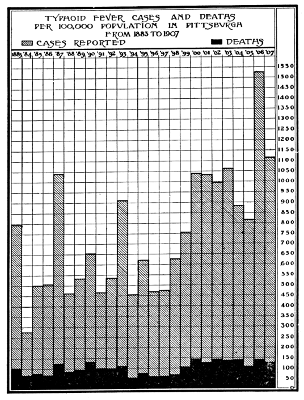

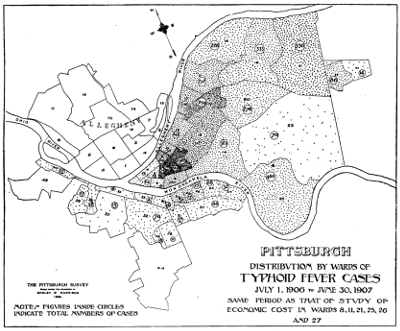

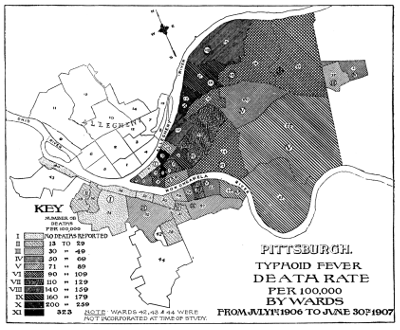

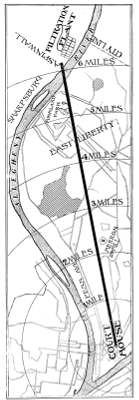

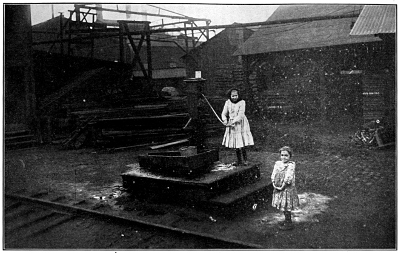

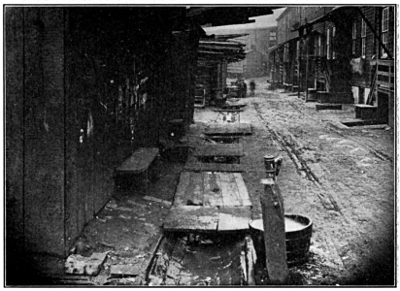

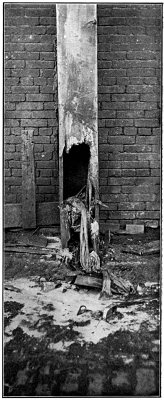

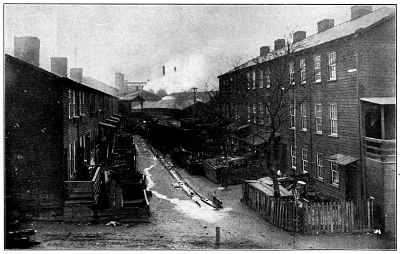

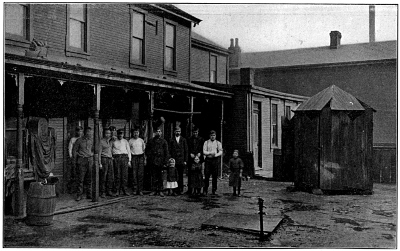

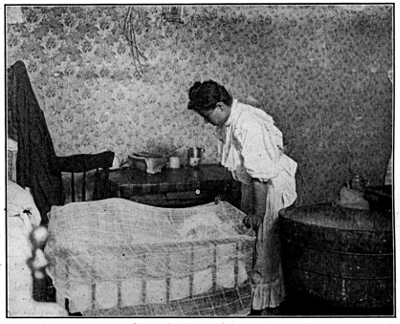

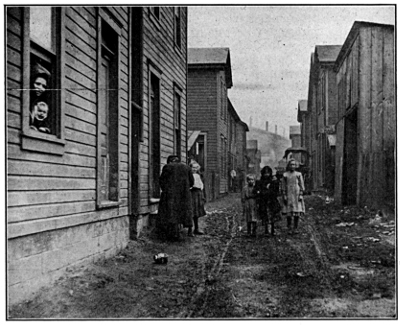

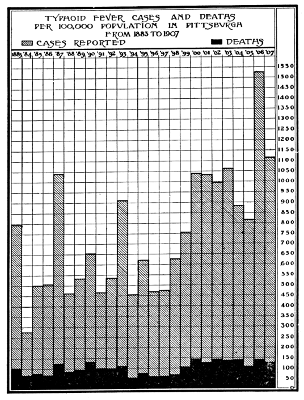

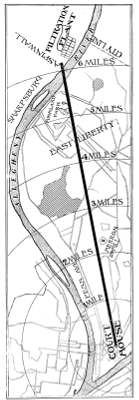

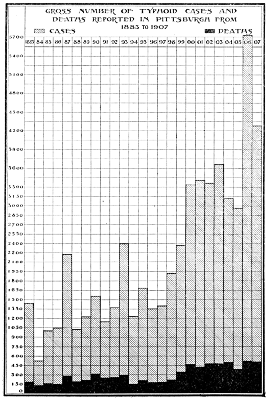

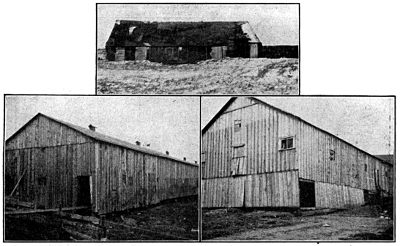

typhoid fever and tuberculosis by wholesale inroads upon almost