Member of The Filson Club

Project Gutenberg's The Quest for a Lost Race, by Thomas E. Pickett This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook. Title: The Quest for a Lost Race Author: Thomas E. Pickett Release Date: December 11, 2014 [EBook #47627] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE QUEST FOR A LOST RACE *** Produced by David Garcia, Les Galloway and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Kentuckiana Digital Library)

FILSON CLUB PUBLICATION No. 22

Presenting the Theory of

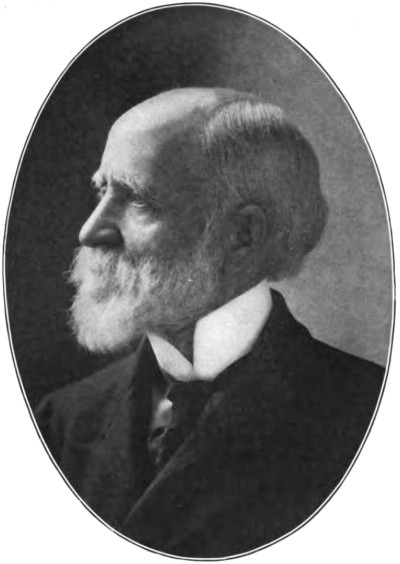

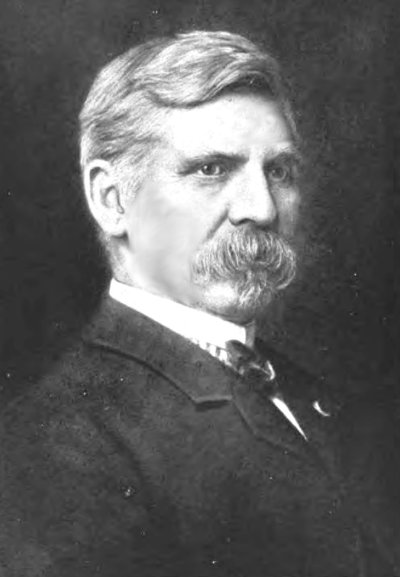

PAUL B. Du CHAILLU

An Eminent Ethnologist and Explorer, that the English-speaking

People of To-day are Descended from the Scandinavians rather

than the Teutons—from the Normans rather than the Germans

BY

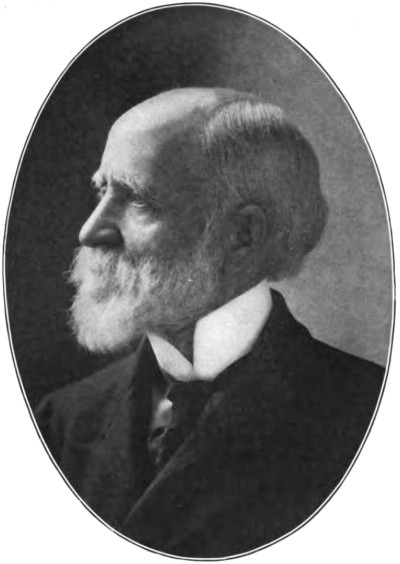

THOMAS E. PICKETT, M.D., LL.D.

Member of The Filson Club

READ BEFORE THE CLUB OCTOBER 1, 1906

Illustrated

LOUISVILLE, KENTUCKY

JOHN P. MORTON & COMPANY

Printers to The Filson Club

1907

COPYRIGHT, 1907

BY

The Filson Club

All Rights Reserved

Filson Club Publications

NUMBER TWENTY-TWO

The Quest for a

Lost Race

Alphabetical Series of Norse, Norman, and

Anglo-Norman, or Non-Saxon,

Surnames

BY

THOMAS E. PICKETT, M. D., LL. D.

Member of The Filson Club

The native Kentuckian has a deep and abiding affection for the "Old Commonwealth" which gave him birth. It is as passionate a sentiment, too—and some might add, as irrational—as the love of a Frenchman for his native France. But it is an innocent idolatry in both, and both are entitled to the indulgent consideration of alien critics whose racial instincts are less susceptible and whose emotional nature is under better control. Here and there, a captious martinet who has been wrestling, mayhap, with a refractory recruit from Kentucky, will tell you that the average Kentuckian is scarcely more "educable" than his own horse; that he is stubborn, irascible, and balky; far from "bridle-wise," and visibly impatient under disciplinary restraint. In their best military form Kentuckians have been said to lack "conduct" and "steadiness"—even the men that touched shoulders in the charge at King's Mountain and those, too, that broke the solid Saxon line at the Battle of the Thames.

Whether this be true or not—in whole or in part—we do not now stop to enquire. Suffice it to say that the Kentuckian has been a participant in many wars, and has given[Pg iv] a good account of himself in all. In ordinary circumstances, too, he is invincibly loyal to his native State; and when it happened that, in the spring of 1906, there came to Kentuckians in exile, an order or command from the hospitable Governor of Kentucky to return at once to the State, they responded with the alacrity of distant retainers to a signal from the hereditary Chieftain of the Clan. "Now," said they, "the lid will be put on and the latch-string left out."

When the reflux current set in it was simply prodigious—quite as formidable to the unaccustomed eye as the fieldward rushing of a host; and it was in the immediate presence of that portentous ethnic phenomenon that the paper upon the "Lost Race" was first published;—appearing in a local journal of ability and repute, and serving in some measure as a contribution to the entertainment of the guests that were now crowding every avenue of approach.

It is not strange that the generous Kentuckians, then only upon hospitable thoughts intent, should imagine for one happy quart d'heure that the "Lost Race" of the morning paper was already knocking at their doors. But they little imagined—these good Kentuckians—that their hospitable suspicion had really a basis of historic truth.

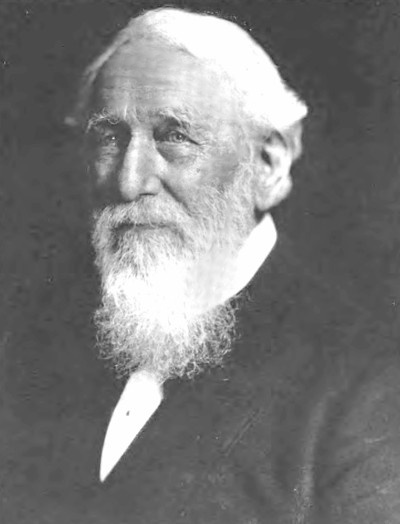

The handsome book now launched from the Louisville press is merely that ephemeral contribution to a morning[Pg v] paper,[1] presented in a revised and expanded form, with such illustrations as could come only from the liberal disposition and cultivated taste of Colonel R. T. Durrett, the President of The Filson Club. The title which the writer has given the book is recommended, in part, by the example of a great writer of romance, who held that the name of the book should give no indication of the nature of the tale. If the indulgent reader should be unconvinced by the "argument" that is implied in almost every paragraph, it is hoped that he will at least derive some entertainment from the copious flow of reminiscential and discursive talk. The book is addressed chiefly to those persons who may have the patience to read it and the intelligence to perceive that nothing it contains is written with a too serious intent.

The writer makes grateful acknowledgments to the many friends who have encouraged him with approval and advice in the preparation of the work. For the correction of his errors and the continuance of his labors he looks with confident expectation to the Scholars of the State.

While the Home-Coming Kentuckians were enjoying their meeting, in Louisville, in the month of June, 1906, Doctor Thomas E. Pickett published a newspaper article which he had written for the Home-Coming Week, the object of which was to present the theory of Paul B. Du Chaillu as to the descent of the English-speaking people from the Scandinavians instead of the Teutons; and to show that the descendants of these Scandinavians were still existing in different countries, and especially in Kentucky. The author sent me a copy of his article, and after reading it I deemed it an ethnological paper worthy of a more certain and enduring preservation than a daily newspaper could promise, and concluded that it would be suitable for one of the publications of The Filson Club. I wrote to the author about it, and suggested that if he could enlarge it enough to make one of the annual publications of the Club, of the usual number of pages, and have it ready in time, it might be issued for the Club publication of 1907. The author did as I suggested, and the book to which this is intended as an introduction is number twenty[Pg viii]two of The Filson Club publications, entitled "The Quest for a Lost Race," by Thomas E. Pickett, M. D., LL. D., member of The Filson Club.

Many persons of the English-speaking race of to-day believe that the English originated in England. The race doubtless was formed there, but it came of different peoples, principally foreign, who only consolidated upon English soil. Half a dozen or more alien races combined with one native to make the English as we now know them, and many years of contention and change were required to weld the discordant elements into a homogeneous whole.

The original inhabitants of England, found there by Julius Cæsar fifty-five years before the Christian era and then first made known to history, were Celts, who were a part of the great Aryan branch of the Caucasian race. Their numbers have been estimated at 760,000, and they were divided into thirty-eight different tribes with a chief or sovereign for each tribe. They were neither barbarians nor savages in the strict sense of these terms. They were civilized enough to make clothes of the skins of the wild animals they killed for food; to work in metals, to make money of copper and weapons of iron, to have a form of government, to build cabins in which to live, to cultivate the soil for food, and to construct war chariots[Pg ix] with long scythes at the sides to mow down the enemy as trained horses whirled the chariots through their ranks. They had military organizations, with large armies commanded by such generals as Cassivelaunus, Cunobelin, Galgacus, Vortigern, and Caractacus, and once one of their queens named Boadicea led 230,000 soldiers against the Romans. The bravery with which Caractacus commanded his troops, and the eloquence with which he defended himself and his country before the Emperor Claudius when taken before him in irons to grace a Roman triumph, compelled that prejudiced sovereign to order the prisoner's chains thrown off and him and his family to be set at liberty. There were enough brave men and true like Caractacus among these Celts, whose country was being invaded and desolated, to have secured to the race a better fate than befell them. After being slaughtered and driven into exile into Brittany and the mountains of Wales by Roman, Saxon, and Dane for eight hundred years, the few of them that were left alive were not well enough remembered even to have their name attached to their own country.

The Celt was entirely ignored and a name combined of those of two of the conquerors given to their country. Who will now say that Anglo-Saxon is a more appropriate name for historic England than the original Albion, or[Pg x] Britannia, or Norman-French, or Celt? Anglo-Saxon, compounded of Anglen and Saxon, the names of two tribes of Low Dutch Teutons, can but suggest the piracy, the robbery, the murder and the treachery with which these tribes dealt with the Celts; while Norman-French reminds us of the courage, the endurance, and the refinement which were infused into the English by the Norman Conquest. Celt is a name which ought to have been respected for its antiquity of many centuries since it left its ancient Bactria and found its way to England without a known stain upon its national escutcheon. These Celts were once a mighty people occupying France, Spain, and other countries besides England, but their descendants are now scattered among other nations, without a country or a name of their own.

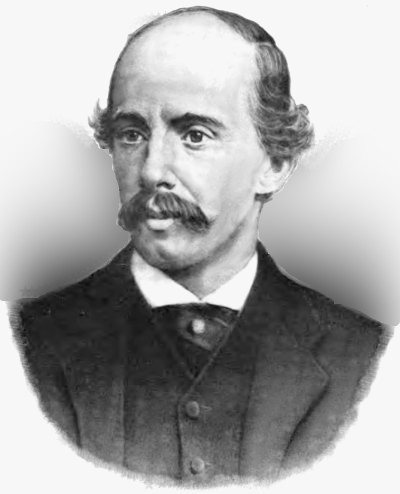

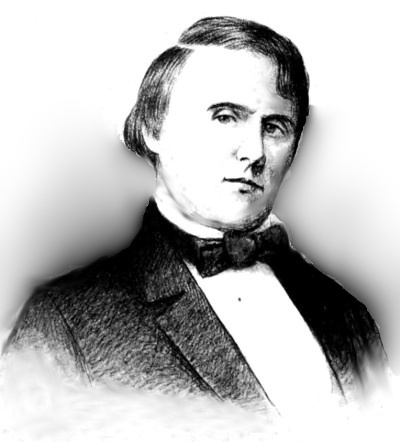

There may be doubts whether the Angles, the Jutes, the Saxons, and the Danes—all of whom shared in partial conquests of England and in the establishment of the English race—were Scandinavians or Teutons, Normans or Germans. They all belonged to the great Aryan branch of the Caucasian race, and whatever differences or similarities originally existed between them must have changed in the thousands of years since they emigrated from their first home. There can be no doubt, however, about the nationality of William the Conqueror. He was Scandi[Pg xi]navian by descent from a long line of noble Scandinavian ancestors. The home of his ancestors was in Norway, far to the north of the home of the Teutons in Germany. In this bleak land of Arctic cold and sterility, on the western coast of Norway, where innumerable islands form a kind of sea-wall along the shore, his ancestor, Rognvald, who was a great earl holding close relations with King Harold of Norway, had his home and his landlocked harbor, in which ships were built for the vikings who sailed from that port to the shores of all countries which they could conquer or plunder. Here, his son Gongu Hrolf, better known as Rollo or Rolf, was born and received his training as a viking. On his return from one of his viking raids to the East he committed some depredations at home, for which King Harold banished him. He then fitted out a ship and manned it with a crew of his own choice and sailed for the British Channel islands. When he reached the river Seine he went up it as far as Paris, and, according to the fashion of the times, laid waste the country as he went. King Charles of France offered to buy him off by conveying to him the country since known as Normandy and giving him his daughter in marriage, on condition that he would become a Christian and commit no more depredations in the King's domain. Rollo accepted the King's offer[Pg xii] and at once ceased to be a viking, and began to build up, enlarge and strengthen the domain which had been given him with the title of Duke. In the course of time his dukedom of Normandy, with the start Rollo had given it and its continuance under his successors, became one of the most powerful and enlightened countries of the period.

At the death of Rollo his dukedom was inherited by his son, William, and after passing through four generations of his descendants who were dukes of Normandy it descended to a second William, known as the Conqueror. Duke William, therefore, could trace his Scandinavian descent through his paternal ancestors back to Rognvald, the great earl of Norway, and even further back through the earls Eystein Glumra, Ivar Uppland, and possibly other noblemen of hard names to write or pronounce or remember. It is possible that some of his ancestors were with Lief the Scandinavian when he made his discovery of America, nearly five hundred years before the discovery of Columbus.

In 1066, Duke William took advantage of a promise, solemnized by an oath, which Harold had made before he was King of England, to assist him to the throne of England, but which he had not kept. Hence William invaded England with a great army, and at the battle[Pg xiii] of Hastings slew King Harold and gained a complete victory over his forces. Duke William was soon after crowned King of England, and at once began that wise policy which in a few years enabled him to lay firmly the foundation of the great English nation. His conquest, though not complete at first, was more so than had been that of the Romans, or the Angles and Jutes, or the Saxons or the Danes. At the time of the Conquest of William there were hostile Celts, Romans, Angles, Jutes, and Danes in every part of his kingdom. It was not his policy to destroy any more of them than he deemed necessary, but to make as many of them citizens loyal to him as possible; hence his numerous army and the still more numerous hosts that were constantly coming from Normandy to England in time became reconciled to the people and the people to them, until all were consolidated into one homogeneous nation. English history may be said to have begun with the Conquest of William, for all previous history in the island was but little more than the record of kings and nobles and pretenders contending against kings, nobles, and pretenders, and sections and factions and individuals seeking their own aggrandizement. The Conquest of William began with the idea of all England under one sovereign, and he and his successors clung to this view until it was accomplished.[Pg xiv] England never went backward from William's Conquest as it did from others, but kept right on in the course of empire until it became one of the greatest countries in the world, and this conquest was made by Scandinavians, who, if they did not make Scandinavians of the conquered, so Scandinavianized them that it would be difficult to distinguish them from Scandinavians.

The evolution of the English race from so many discordant national elements reminds one of the act of the witches of Macbeth, casting into the boiling cauldron so many strange things to draw from the dark future a fact so important as the fate of a king. Who would have thought that from the mingling of the Celts and the Romans and the Angles and the Jutes and the Saxons and the Danes and the Normans and the French in the great national cauldron that such a race as the English would be evolved? But it is not certain that such a race would have been produced if William the Scandinavian and his French had been left out. He came at a time when a revolution was needed in manners and language as well as in politics, and imparted that refinement which the French had gotten from the Romans and other nations. The French language so imparted soon began to infuse its softening influence into the jargon of the conglomeration of tongues in vogue, and the French manners to[Pg xv] refine the clownish habits which had come down from original Celt, Saxon, and Dane. The Saxons and Danes had inhabited England for the four hundred years which followed the same period occupied by the Romans, without materially changing the manners or the language of the English, but it was not as long as either of these periods after the Conquest before the Englishman acted and spoke like a gentleman and belonged to a country which commanded the respect as well as fear of all other nations. The Scandinavian's fondness for war soon infused itself into the English and made them invincible upon both land and sea, and now with a land which so envelopes the earth that they boast the sun always shines on some part of it, they may look back some hundreds of years to the origin of their greatness and find no one thing which contributed more to the glory of England than the Norman-French Conquest.

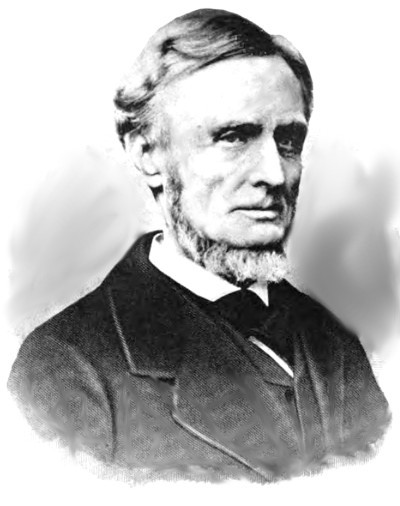

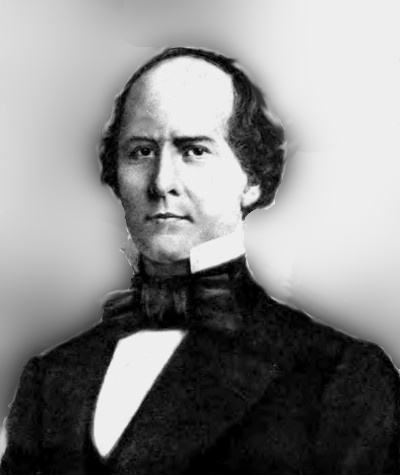

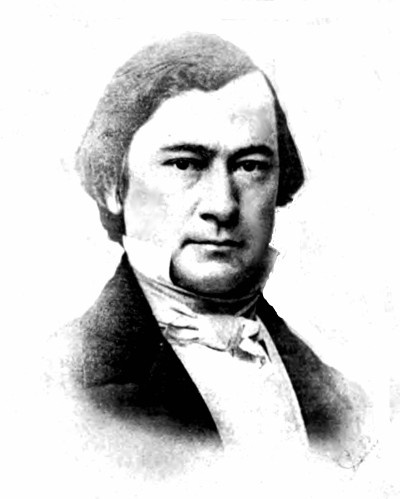

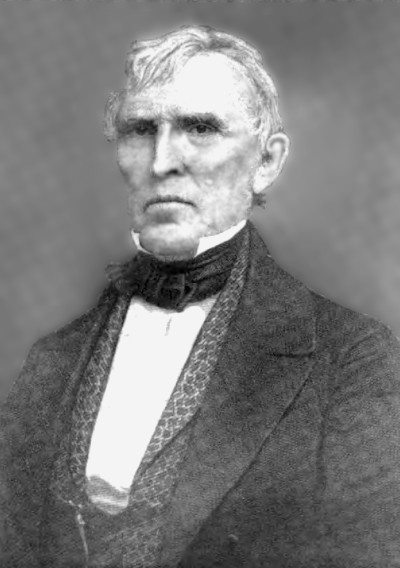

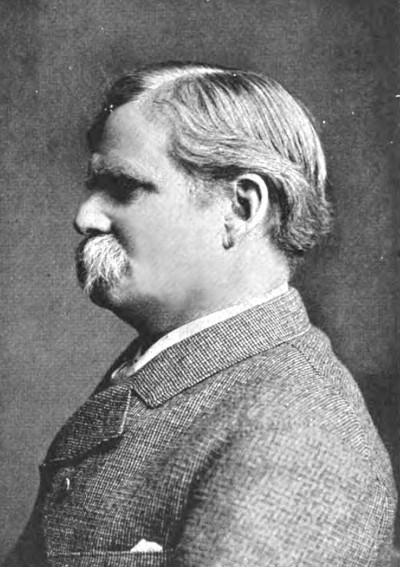

But the reader had better learn the views of Paul B. Du Chaillu, an accomplished ethnologist and explorer, about the descent of the English from the Scandinavians instead of the Teutons as set forth in Doctor Pickett's book than from me in an introduction to it. Doctor Pickett explains the Du Chaillu theory, and gives examples of similar tastes and habits between English and Scandinavians which are striking. He also gives a[Pg xvi] long list of names borne by Scandinavians in England and Normandy eight hundred years ago which are the same as names borne by Kentuckians to-day. In this introduction, I have rather confined myself to such historic matters as are involved, without alluding to the ethnological facts so well presented in the text by the author. The work is beautifully and copiously illustrated with halftone likenesses of the author and Du Chaillu and by a number of distinguished Kentuckians of Scandinavian descent. There was both good taste and skill in placing among the illustrations the likenesses of Theodore O'Hara, John T. Pickett, Thomas T. Hawkins, and William L. Crittenden, who joined the filibustering expeditions of Lopez to Cuba. These distinguished citizens, like the Scandinavian vikings whom they imitated, lost nothing of their character by raiding upon a neighbor's lands, and are among the best examples of the theory of the descent of the English-speaking people from Scandinavians rather than Teutons. To be an admirer of this work it is not necessary to be a believer in the theory of Du Chaillu, that the English are descended from Scandinavians instead of Teutons. The truth is, all the northern nations connected with England were kinsmen descended from the same stock—Celts, Romans, Angles, Jutes, Saxons, and Danes all being of the Aryan[Pg xvii] branch of the great Caucasian race. They are so much alike in some particulars that fixed opinions about differences or likenesses between them are more or less untenable. There is one thing, however, in the book about which there can be no two opinions, and that is the value and importance of the list of names copied from records eight hundred years old, in England and Normandy. As many of them are the same as names now borne by living families in Kentucky, they can hardly fail to be of help to those in search of family genealogy. Doctor Pickett has presented in this work the theory of Du Chaillu in charming words and with excellent taste, as the theory of Du Chaillu and not as his own, and such has been my effort with regard to myself in this introduction. It is simply the resumption of a "Quest."

R. T. Durrett,

President of The Filson Club.

| OPPOSITE PAGE | |

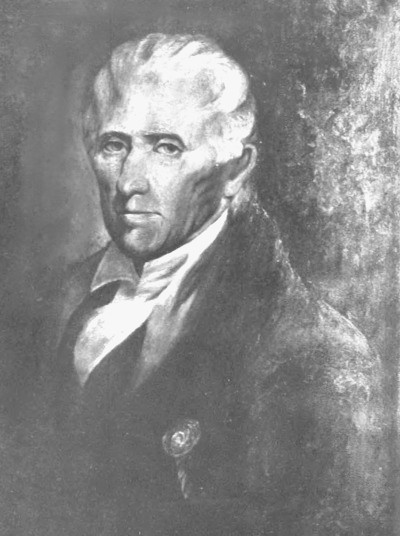

| Thomas E. Pickett, M. D., LL. D. | Frontispiece |

| Paul B. Du Chaillu | 4 |

| King William the Conqueror | 8 |

| "The Map that Tells the Story" | 12 |

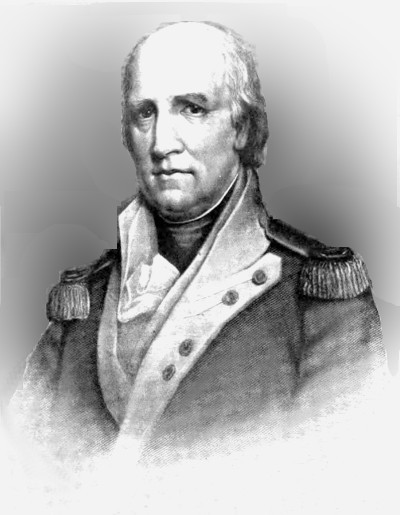

| George Rogers Clark | 16 |

| Daniel Boone | 24 |

| Isaac Shelby | 32 |

| Joseph Hamilton Daveiss | 36 |

| Henry Clay | 40 |

| Joseph Desha | 48 |

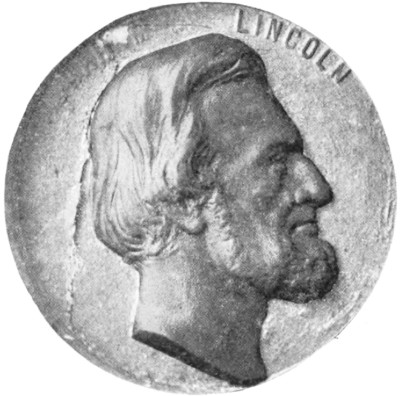

| Abraham Lincoln (bas relief) | 56 |

| "Our Beautiful Scandinavian" | 64 |

| Jefferson Davis | 72 |

| John C. Breckinridge | 80 |

| William Preston | 88 |

| Basil W. Duke | 96 |

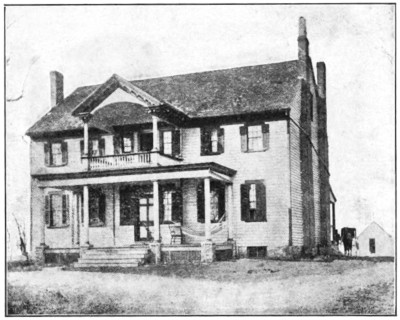

| The Marshall Home at "Buck Pond" | 104 |

| Richard M. Johnson | 112 |

| J. Stoddard Johnston | 120 |

| Northumbria | 128 |

| Theodore O'Hara | 136 |

| John T. Pickett | 144 |

| Thomas T. Hawkins | 152 |

| William L. Crittenden | 160 |

| William Nelson | 168 |

| Humphrey Marshall | 176 |

| John J. Crittenden | 184 |

| Henry Watterson | 192 |

| Bennett H. Young | 200 |

| Reuben T. Durrett | 208 |

| I | |

| PAGE | |

| The "Scandinavian Explorer," Du Chaillu, visits Kentucky—A cordial reception | 1 |

| II | |

| British Association Meeting at Newcastle, 1889—A sensational paper—Industrial activity of Modern Northumbria—A notable group of savants | 10 |

| III | |

| Revelations of ancient records bearing upon the origin of the English race | 20 |

| IV | |

| Characteristic traits of the early Normans—Transmission of racial qualities—Mid-century Kentuckians | 27 |

| V | |

| Doctor Craik's views—English more Scandinavian than German—George P. Marsh—Editorial comment on the "sensational paper" | 34 |

| VI | |

| Scandinavians and Kentuckians—Characteristic traits in common—Their passion for the "Horse"—Doncaster races—"Cabullus" in Normandy—Crusading "Cavaliers"—The "Man-on-Horseback"—His "effigies" on English seals—The production of cavaliers—The grasses | 42[Pg xx] |

| VII | |

| A French savant on English types—Weismann's "theory"—"Snorro Sturleson" quoted by Lord Lytton—The "homicidal humor" not invented by Kentuckians, but possibly inherited—Andrew D. White quoted | 51 |

| VIII | |

| John Fiske—Ethnic differentiation—the Hindoo and the Kentuckian—Aryan brothers—A broad historic "highway" from the Baltic Sea to the Bluegrass—Streams of Scandinavian migration—"The Virginian States"—Anglo-Norman "lawlessness"—Degenerate castes or breeds—"Political assassination" as practiced by Norman and Saxon—"The homicidal humor not an invention of Kentucky" (Shaler); Not invented, but derived—Andrew D. White on the American murder record | 58 |

| IX | |

| Peculiar Norman traits—Craft—Profanity—A "swearing" race—Historic oaths—Kentuckians full of strange oaths | 63 |

| X | |

| William, the Norman; Napoleon, the Corsican; great administrators—The conditions of English civilization—American statesmen | 76 |

| XI | |

| Early Virginian history—Researches of Doctor Alexander Brown—Kentucky a direct product of Elizabethan civilization—The "Vikings of the West"—Professor Barrett Wendell's views | 83[Pg xxi] |

| XII | |

| The Norman as a colonizer—As a devastator—Revival of Northumbria by modern industrialism—The power of Scandinavian energy in pushing the victories of peace—English Unity established on Salisbury Plain—The Scandinavian in literature—Shakespeare and his Historical Plays—Psychological contrasts of modern Scandinavian races—Shakespeare's favorite author—Evolution of the "Melancholy Dane"—Advice from a thoughtful Frenchman: "Let us not disown the fortune and condition of our ancestors" | 90 |

| XIII | |

| A body of Anglo-Norman names in Kentucky—Concurrent testimony of many coinciding facts—The Race "lost," but not the Names—Ethnical transmutations—The Normans everywhere at home—Disraeli on descent—His theory of transmuted traits—Hæckel—The jungle of Bohun—Berwick and Gaston Phœbus—"Isaac le Bon"—Bismarck—Napoleon—Mid-century "claims of race"—Kentucky a sovereign Commonwealth—Shelby and Perry | 101 |

| XIV | |

| The Gothic migration—Scandinavian pirates—Their foot-prints on English soil—Normans hotly received by their kindred, the Danes—Old Gothic wars—"The Yenghees and the Dixees"—Westward march of the Teuton and the Goth—Genesis of the Scandinavian—Cradle of the race—Rolf Ganger a potential force—Reconstruction of the modern world—William of Normandy | 108[Pg xxii] |

| XV | |

| Stragglers in the Gothic migration—Jutes, Angles, Saxons—The two great races; Teutons and Scandinavians—"Mixed races" planted on the southern shores of the North Sea | 114 |

| XVI | |

| Authentic lists of old Norman names—Descendants of illustrious families—The Norman capacity for leadership not "lost"—Alphabetical series of names (from "The Norman People"); English names originally Norman—Familiar as household words in Kentucky—A legal maxim—Elements of the English race—Preponderance of Scandinavian blood—Stevenson and Disraeli—Lord Lytton—Maltebrun—Scandinavian characteristics—Physique—Social traits—Passion for "strong liquor"—Hospitality | 117 |

| XVII | |

| Captain Shaler quoted—Measurements of American soldiers by the mathematician Gould—Superior physical vigor of the "rebel exiles"—General Humphrey Marshall—His aide Captain Guerrant—General William Nelson—"The Orphan Brigade"—Hereditary surnames as memorials of race—Every step of Norman migration noted by the historic eye—Montalembert—"Monks of the West"—The rude Saxon transfigured by the eloquence of the gifted writer—A field for the philologist | 123[Pg xxiii] |

| XVIII | |

| The alphabetical series of names—Anglo-Norman surnames—Names of obvious Scandinavian derivation—The original discussion of the general question—An excerpt from Sir Walter Scott—The "Elizabethan" a product of a balanced race—The march of the Goth resumed—The Virginian hunter—The Yankee skipper—A man of oak and bronze | 126 |

| XIX | |

| Norman craft—Mr. Freeman quoted—Popular attribution of the quality—Its value in mediæval days—Its prevalence to-day | 131 |

| XX | |

| Names and Notes—Kentuckian and Norman—Characteristics in common—Norman traits and Saxon names—Estimate of the Kentuckian from an English source | 133 |

| XXI | |

| Shadows in "Arcady"—Brief preface to the alphabetical list | 136 |

| APPENDIX | |

| Alphabetical Series of Norse, Norman, and Anglo-Norman, or Non-Saxon, Surnames | 141 |

THE QUEST FOR A LOST RACE

BY

THOMAS E. PICKETT, M. D.

Upon the northern border of Mr. James Lane Allen's "Arcady" there rises with picturesque distinctness against a range of green hills the pleasant old Kentucky town of Maysville, which, unlike the typical town of the South, is neither "sleepy" nor "quaint," but in a notable degree animated, bustling, ambitious, advancing, and up-to-date. It must be confessed, however, that here and there, in certain secluded localities, it is architecturally antique. Constructed almost wholly of brick, and planted solidly upon the lower slopes of the wooded hills, the site is indescribably charming, and, looked at from a distant elevation in front or from the elevated plateau of the environing hills, presents a pleasing completeness and finish in the coup d'œil. At one glance the eye takes in the compact little city, set gem-like in the[Pg 2] crescentic sweep of the river that flows placidly past the willow-fringed shore and the walled and graded front. The scene is likewise suggestive, since it marks the northern limit of the "phosphatic limestone" formation which assures the permanent productiveness of the overlying soil—a natural fertilizer which by gradual disintegration perpetually renews the soil exhausted by prolonged or injudicious cultivation.

The town is of Virginian origin. At one time, indeed, it was a Virginian town. The rich country to the south of it was peopled chiefly by tobacco planters from "Piedmont" Virginia, slaveholding Virginians of a superior class.

In the infancy of this early Virginian settlement it was vigilantly guarded by the famous Occidental hunters, Kenton and Boone; the former a commissioner of roads for the primitive Virginian county, then ill-cultivated and forest clad: the latter, a leading "trustee" of the embryonic Eighteenth Century town. As we pass through the streets near the center of the place to-day we note the handsome proportions of a public edifice which has come down to us from the early mid-century days—an imposing "colonial" structure with a lofty, well-proportioned cupola and a nobly columned front. It is that significant symbol of Southern civilization—the Court[Pg 3]house. To the artistic and antiquarian eye the building is the glory of the old "Virginian" town, since it appeals at once to civic pride and superior critical taste.

It was here—in the capacious auditorium of the Courthouse, and in the closing quarter of the last century—that a large and enthusiastic gathering of really typical Kentuckians, familiar from childhood with tales of wild adventure, greeted with rapturous applause the renowned hunter and explorer, Paul Du Chaillu, a native of Paris, France. A common taste for woodcraft had brought the alien elements in touch. The Frenchman was a swell hunter of big game, and had come hither to repeat his graphic recital of experiences in the equatorial haunts of that formidable anthropoid—the Gorilla. Du Chaillu's discovery of the gorilla and the Obonga dwarfs was so astounding to modern civilization that strenuous efforts were made to discredit it, notably by Gray and Barth. But later explorations amply vindicated the Frenchman's claims.

He had a like experience later. The adventurous explorer had come to Kentucky in prompt response to an invitation from a local club, a social and literary organization which owed its popularity and success chiefly to the circumstance that the genial members, though sometimes intemperately "social," were never obtrusively "liter[Pg 4]ary." The social feature was particularly pleasing to the accomplished Frenchman, who was a man of the world in every sense, and who dropped easily into congenial relations with gentlemen who had an hereditary and highly cultivated taste for le sport in all its phases. Take them when or where you might, the spirit of camaraderie was in them strong. They told a good story in racy English and with excellent taste. They had studied with discrimination the composition of a Bourbon "cocktail." They had a distinctly connoisseurish appreciation of the flavor, fragrance, and tints of an Havana cigar. They had a traditional preference for Bourbon in their domestic and social drinking, but they always kept ample supplies of imported wines for their guests.

The genial Frenchman was very indulgent to the generous tipple of his hosts. He drank their Bourbon without apparent distaste; he praised their imported Mumm and Clicquot. He did better still; he drank the imported champagne with appreciation—a high compliment from such a source.

Clearly enough the harmony between the guest and his environment was complete. These courteous and loquacious Kentuckians were not only brilliant and audacious raconteurs, but with their varied experiences as sportsmen had a variety of marvelous stories to tell. When[Pg 5] their stock of pioneer exploits fell short, they would listen with polite interest to their guest's weird stories of the African jungle, and cleverly cap them with reminiscences of a miraculous outing on Reelfoot Lake or Kinniconick. They were themselves experts with the rifle and the long bow, and were loaded to the muzzle with authentic traditions of the rod and gun.

The jungle stories were all right, but the African hunter was never allowed to forget that he was in the land of the hunter Boone. The very ground upon which they commemoratively wassailed had been consecrated by the footsteps of the great explorer of the West. The beastly "anthropoids" that confronted him were armed with tomahawks and guns. A salient point of difference indeed. The clever and daring Frenchman listened with smiling interest to their characteristic spurts of "brag," and was silently remarking, no doubt, its curious affinity to the gasconade of France. He seemed to feel perfectly at home. And who of us that were present can ever forget the impression of that dark, resolute face, the illumining smile, the gleaming teeth, and the kindly, humorous glance of the piercing eye? His experiences at the clubroom only partially prepared him for the peculiar impressiveness of the audience that greeted him at the stately old Courthouse. There were the same men, to be sure, hand[Pg 6]some, graceful, courteous, smiling, and soft of speech; but the women!—with their lovely faces, their handsome dresses, their enchanting manners, their distinction, ease and charm! The Frenchman was never more of a philosopher than when he gazed upon this scene.

He told his tale of the jungle simply, but with a vividness that was realistic and startling to a degree. The fascination of the audience was complete. He not only described that strange encounter in the African forest, but he re-enacted the part, a representation which gave a curiously thrilling quality to the tale not appreciable when told in print, admirably as it is told in the author's famous book.

When the voice of the speaker ceased, as it did all too soon, the silent, fascinated audience, aroused from its strange African dream, broke into round after round of hearty, appreciative applause. For several moments the lecturer stood in a grave, thoughtful attitude, gazing intently upon the moving throng, not as though idly observing the dispersion of a village gathering, but as some philosophic tourist from another sphere, studying the aspect, the attitude, characteristic manner and physiognomical traits of an alien race. He asked but one question. Turning eagerly to the gentleman who accompanied him, he inquired with an expression of intense[Pg 7] interest, as his glance fell upon a graceful Kentuckienne near the center of the throng—a lovely blonde with exquisite complexion, hair and eyes—"Who is our beautiful Scandinavian?"[2] The answer seemed to please him, and he walked thoughtfully toward the door, an object of respectful attention from the slow-moving throng, lingering as if it longed to stay. Though of small stature, he would have attracted attention anywhere. His figure was compact, lithe, elastic, and perfectly erect, his cranial outline (typically French) denoted intellectual strength and physical vigor, his facial contour was bold, regular, and pleasing—a singularly virile countenance softened and dignified by the discipline of thought. The crowd of which he is now the central figure is composed largely of men wholly different from Du Chaillu in air, stature, carriage, countenance, complexion, and racial type. Yet Nature seldom evolves from any source a solider bit of man than this gallant Frenchman from the heart of France.

The distinguished guest took his departure on the following day, not with a cold adieu, but with an airy au revoir—as of one who, charmed with his welcome, was meditating an early return. But was he pleased? Apparently he was, and if not, he had the Frenchman's happy art of seeming to be. If here simply for observation, he certainly found no degeneracy, but rather, we should say, certain pleasing lines of variation in the Occidental evolution of the race. It seems impossible that he should not have had a pleasant impression of his hosts—these genial sons of "Arcady," forever piping their minty elixirs with oaten straws, whose drinks even when "straightest" were not stronger than their steady heads—so hospitable to strangers, so chivalrous to women, so courteous to men, so gracious in manner, so happy in speech, so loyal to kin, so proud of their Commonwealth, their ancestral traditions, and their indomitable race. They drank naught from the skulls of their enemies, but they were adepts in filling their own. Their potations were pottle deep, and the intervals between were not needlessly prolonged. And yet they rose refreshed from their heady cups, ordered their stud a drench, and sighed for work.

The adventurous Frenchman was no glutton in debauch, but in a modest symposium could always hold[Pg 9] his own, and doubtless imagined in this festal reunion of Bourbon and Champagne that he had re-discovered the Nouvelle France of the royal days when Louis le Grand was King.[3]

In the early autumn of 1889, the writer of this paper had the good fortune to be present at the Newcastle meeting of the British Association. Newcastle-upon-Tyne, standing at the very gateway of Scotland and looking out from the Tyne upon the great North Sea, is a famous old city in English history, that lay directly in the path of conquest and migration and was literally cradled in war, alternately rocked by Scandinavian or Dane, Saxon or Norman, Englishman or Scot. To-day it is big, prosperous, and progressive; even in the midst of peace perpetually sounding the note of preparation for war. True to its oldest and best traditions it is staunchly loyal to the Crown, proudly proclaiming its fealty on every coast, from the mouths of mighty guns cast in its own Cyclopean shops. From the days of the Scandinavian sea-rover through centuries of ruthless conflict she has stood out stoutly against the enemies of England, just as to-day her long sea-front of solid wall resists the encroachments of the Northern sea.

Here the shipbuilder is ceaselessly busy, constructing in his immense yards the great modern ship with its heart of fire and frame of steel. In any large yards the[Pg 11] whole scheme of construction in all its branches may be seen at a glance, from the laying of the keel to the launching of the ship. The best work in modern engineering can be seen on the Tyne; and this is not surprising when we remember that upon the banks of this river the Locomotive was born, giving to this aggressive contemporary people a command of the earth as complete as their immemorial mastery of the sea. So enormous is the demand for fuel in the shipyards of the North-east Coast that it will take but a few centuries of work in these busy shops to exhaust the supply. The old proverb has lost its point. The most careless or unobservant tourist may see the steam-drawn trains "carrying their coals" to Newcastle, now, at all hours.

Nor does the Northern farmer sit with idle hands. All industries rest upon him. The farms are small, but the joint product is large. Thousands of farm laborers in Northumberland have each their "three acres and a cow." The Northern cattle-market in Newcastle would have filled the Highland caterans with delight. The weekly supply of cattle exceeds two thousand; the number of sheep is not less than twenty thousand. This was nearly twenty years ago. What must it be now? But even thus, how it speaks for the varied gifts and exhaustless vigor and vitality of this old Northumbrian race![Pg 12] Their rage for "river improvement" carries a lesson for men of their blood elsewhere. Between 1860 and 1889 the material dredged from the bed of the river Tyne amounted to more than eighty millions of tons. "Now,"—it was said at the Newcastle meeting—"there are more vessels entering and leaving this port than any other in the world." Among the outgoing vessels at that time was a gallant Norwegian barque which bore the name of "Longfellow." A few years before—a score, perhaps—the writer had seen upon a famous track in Kentucky a racer of great note who bore the same illustrious name—almost a contemporaneous compliment from widely separate branches of the same race. But what more enduring than the singer's own verse?—

A fit place of meeting—this old gateway of the North—for a select body of England's brilliant, busy, clear-headed and practical savants, and especially for that marvelously fruitful mid-century "section" which here first received supreme scientific recognition, having been organized at the Newcastle meeting by the British Association in 1863.

Though the youngest of the sections, its proceedings are singularly fascinating and the attendance always large. The meeting was held in the reading-room of the[Pg 13] Free Library. Upon a long, low platform to the left of the entrance there sat facing the audience, a group, not of "scientists," but of really scientific men, their names as familiar to the English reading world as household words. The central figure of the group, Sir William Turner of Edinburgh, was the chairman of the section—a man of striking personality, who read a paper on Weismann and his theories which was listened to with closest attention, the novelty of the doctrines eliciting many expressions of doubt or dissent, though presented by the author of the paper with singular lucidity, fairness, and force. Sir William graced his position well, not merely by reason of intellectual gifts, but by virtue of a personal dignity which admirably comported with his commanding presence. He was a large, handsome man, with a robust frame, an erect carriage, and a notably aggressive air. Seated near him, and firmly supporting his somewhat heavy presence, were a number of men with world-renowned names—Francis Galton, famous for his studies in heredity and the publication of an epochal work; Sir Henry Acland, a learned anthropologist and medical scholar—a thinker of deep and varied scientific resource; Boyd Dawkins, the pioneer "Cave Hunter" and writer upon prehistoric archæology; John Evans, an able, learned, and industrious writer upon archæological themes; Doctor Bruce,[Pg 14] the eminent historian of the Roman Wall; General Pitt Rivers, equally famous as soldier and savant, a quiet, dark-faced gentleman of easy, pleasant manners, dressed in the plainest fashion and judiciously expending an income of £30,000 a year. His large benefactions for scientific purposes made him truly a Prince of Science, gracious, munificent, and wise. The most striking and conspicuous figure in this solid English line was George Romanes, then in his prime and in apparently perfect health, tall, erect, dark-haired, with pale, handsome features and scholarly, high-bred air—a most impressive personification of intellectual pride and strength. As he sat in the midst of that animated group, cold, proud, silent but keenly observant, he vividly recalled the figure of the famous Kentuckian who once presided over the United States Senate, calmly noting the portents of impending war. In both, one easily discerned the same high qualities of intellect, resolution, and reserved force. By the side of the stately Romanes there sat the learned and vivacious Canon Isaac Taylor, slender, gray-haired, keen-eyed, alert, humorous, and full of tact—one of those clerical scholars and gentlemen who have done so much for English literature and have been a characteristic charm of English social life—men most admirably depicted by the novelist Bulwer in his better moods. Canon Taylor[Pg 15] was the most animated figure in this noble English group. Near him sat two foreigners, each in curiously striking contrast with the other; one of these, a tall, ruddy, broad-shouldered blonde, with a strong, lithe, well-knit frame, an eager, alert expression, and a somewhat restless air, was the celebrated Scandinavian explorer Fridjof Nansen, then just twenty-six years of age, but already made world-famous by his recent explorations in the polar seas. At the left of the young Scandinavian, and presenting a remarkable contrast to that impressive figure, there sat a somewhat older man of small stature, of compact, vigorous frame, of clear, dark complexion, keen, clear, thoughtful eyes, and features typically French. The reader recognizes the description at once. It is our old friend, Du Chaillu, who has come to the northern coast of England, and standing in the very pathway of old Scandinavian invasions and confronting some of England's best thinkers upon their own ground, has calmly looked out upon the "grim—troubled" sea of England's Saxon King and boldly proclaimed his theory of the direct Scandinavian origin of the English race.

It was the sensational paper of the day, and even the most phlegmatic English scholar was stirred by this defiant bugle-blast from a philosophic French explorer who was not only disturbing the settled convictions of Eng[Pg 16]lish thinkers, but still worse was running counter to cherished prejudices of the English race. That historic hyphenation of racial appellatives—"Anglo-Saxon"—was a sacred immemorial conjunction of names representing a fusion of racial elements not to be shaken asunder by a blast upon the ram's horn of a wandering Gaul. The assault was not altogether "Pickwickian"; but the Frenchman was a stout antagonist, and found an incidental confirmation of his theory in the occasional flash of Berserker rage which followed his masterly game of parry and thrust. Nor was he ill-equipped for his controversial work. From certain antiquities which he had found during his recent explorations in the North he inferred the existence of commercial relations between the Northmen of that period and the peoples of the Mediterranean Sea, Rome and Greece being at that time in direct communication with these seafaring peoples of the North. The tribes of Germania, on the contrary, were "a shipless people," and according to the Roman writers were still in an uncivilized state. He said there were settlements in Britain by the Northmen during the Roman occupation; that England was always called by the Northmen one of their Northern lands; that the language of the North and of England were similar in the early times; that the early Northern Kings claimed part of England[Pg 17] as their own; that the Northmen were bold and enterprising navigators, pushing their explorations wherever a ship could survive the perils of the sea. On the contrary, neither the Saxons nor the Franks were a seafaring people, either at the time of Charlemagne or at any earlier period.

It was this Scandinavian element which had infused a spirit of enterprise into the English race that they had never lost, and which had made it in all its branches, wherever they had sailed their fleets or pushed their invading columns, the invincible masters of earth and sea. Its resistless movement across the American continent, he declared, was the most dramatic spectacle in history.

This, in brief, was the Frenchman's startling theory; first broached in England on the borders of that rude North Sea which the Vikings had swept in early days, and upon the banks of the peaceful Tyne, where many a Scandinavian rover had moored his little barque. The discussion of M. Du Chaillu's paper took a wide range, all the distinguished ethnologists present—Dawkins, Taylor, Turner, Evans, Galton, and others—participating in this rattling ethnological debate. Du Chaillu, who had very much the attitude of a French suspect in a German camp, maintained throughout his Gallic aplomb, listening with admirable composure and with apparent interest,[Pg 18] though his dark skin visibly reddened at times under the critical lash, however courteously applied. Canon Taylor, who evidently was in full sympathy with Du Chaillu's startling views, gave a happy turn to the little imbroglio by a cleverly parodied quotation from Tennyson's Welcome to the Sea-King's Daughter from over the Sea—

the closing line being given with a politely sympathetic inclination of the head toward the gentleman from France, and with a gracious smile more expressive than his words—the smile interpreting to his hearers the startling disclaimer: "It is nothing to me." The clever ecclesiast read a very learned paper at the same meeting on a similar theme, and the two gentlemen who sat near him, Du Chaillu and Nansen, were ideal representatives of two of his four ethnological types, the Auvergnat type of Central France and the long-headed Scandinavian of the North. Indeed, as a matter for courteous rational discussion the question of "Saxon or Norse" had the profoundest interest for the amiable savant, who seemed to possess in perfection that fine philosophical quality of intellect which the French have happily termed justesse[Pg 19] d'esprit—a quality of mind in which even the ablest disputant may sometimes be deficient.

But, nothing disconcerted by criticism or compliment, M. Du Chaillu remarked, with cold dignity, as he rose in final response: "Opinions, gentlemen, may differ in England from opinions in France, but the truth on both sides of the Channel is the same"—a sentiment to which all present responded with that fine sympathy and with that perfect courtesy "wherein—to derogate from none—the true heroic English gentleman hath no peer."

"Every schoolboy" (to quote Macaulay) is familiar with the salient facts in the history of the Normans; their origin in Scandinavia; the seizure of a fertile province in France (wrung from a fainéant heir of Charlemagne); their extraordinary evolution as the great ethnic force of the period; their absolute mastery of sea and land on every shore, from the Atlantic Ocean to the Red Sea, and notably their Conquest of England, their perfect fusion with the conquered peoples, and the resulting evolution of the English race. All this is commonplace to every historical reader. But recent investigators, going deeper, have inquired if the laws, institutions, language, and material constructions which mark the pathway of Norman conquest are simply the memorials of an extinct race? Is the Norman still living, still powerful, progressive, and prolific? Or is it an exhausted racial force, pithless, impotent, and effete, with no recognizable evidence of its ancient prepotency in racial struggles for existence in the conflicts of the past? Or, in a word, is it, as Mr. Freeman affirms, a Lost Race? The answer to these questions depends largely upon the answer to other queries, to wit: Was the conquest and sequential settlement of England merely[Pg 21] a military invasion? or was it a vast popular migration such as America has witnessed in later times? or was it not in point of fact both—an invasion and a migration, the one following the other?

England was not conquered in a day. The battle of Hastings was decisive, but not conclusive. There was a long and bloody struggle before the invading force. Nearly four years (the duration of our "Civil War") of close, desperate fighting must be encountered before the work of subjugation could be declared complete. Every gap in the ranks of the invader must be filled by the importation of forces from abroad. There was a perpetual draft upon the Continental populations, and a ceaseless "rushing of troops to the front," precisely as in the protracted "War between the States." All Europe had become the recruiting ground of the Conqueror. He was peopling England even in the midst of war; and when the period of "reconstruction" came the stream of migration continued to flow. England was the bourn from which no immigrant returned; and under the military or reconstructive methods of the Conqueror, every invader was permanently planted upon the soil.

Apparently, these considerations furnish a conclusive answer to certain critical objections which shall be cited as we proceed. The facts upon which our conclusions[Pg 22] rest are found, chiefly, in the official records of England and in the authentic annals of the Anglo-Norman races.

Here, then, we must infer the existence of an immense multitude of Norman immigrants mingling and eventually fusing with the subjugated race. What has been the result of this intimate commingling of ethnic elements upon English soil? Is it possible that so daring and successful a gamester as the Norman was lost in the shuffle when an auspicious destiny was directing the game? The writer of this paper thinks that he found in the great Library of the British Museum evidence that the Norman people are still a power upon this planet; to be as carefully counted with in the struggles of the future as in the conflicts of the past.

Recent investigation has disclosed the fact that contemporary records in England and Normandy—records of two different countries of seven hundred years' standing, relating to different branches of the same race—are so minutely detailed as to enable the philosophic enquirer "to trace the identity of families and even individuals, in two countries." And this has been done by placing the Great Rolls of the Norman Exchequer in juxtaposition with similar English records of the Twelfth Century. This comparative juxtaposition of contemporary official records of kindred races geographically separate has been made the[Pg 23] basis of an alphabetical series of English or Anglo-Norman surnames, which is remarkably full, though necessarily incomplete since the compiler, a very able English scholar, was not in position to enumerate all the families then extant; but it contains five times as many names as the famous Battle Abbey Roll, and conclusively shows that the ancestry of the intellectual aristocracy of England was Norman. The Anglo-Saxon and the Dane were shown to be in a hopeless minority. The enquiry which resulted in the compilation of the alphabetical list was restricted entirely to surnames of a purely Norman origin still existing in England. A third or more of this English population is Norman, directly descended from the Norman migration that preceded, accompanied, or followed the Conquest.

Can evidence be more conclusive that the Norman was neither extinguished nor absorbed by the sluggish Saxon who accepted his yoke?

Mr. Thomas Hardy, in his powerful fiction, "Tess," plainly accepts the conclusiveness of these views. His heroine, though of humble origin, clearly owed her involuntary seductiveness and fatal charm to the transmitted potency of her Norman blood, and it is said that in certain secluded parts of England may be found to-day rural or village populations of the same class gathered[Pg 24] about some old Norman castle, donjon, or keep; their Norman descent distinctly visible in their inherited personal traits; a certain characteristic combination of intellect, courage, beauty, and social charm distinguishing them at a glance from the dull, heavy, long-bodied, short-legged, unshapely Saxon of a neighboring town or shire. The same restless blood or the same spirit of adventure which brought the Scandinavian to Normandy and the Norman to English soil, in time drove him to the great settlements beyond the Atlantic Sea—settlements known by the English of to-day as "The States." Their brethren in Ireland followed in great numbers at a later day, and, wherever in recent wars the American flag has been unfurled, "the fighting race" has stood beneath its folds—always in force and always at the front, each with the line of battle beneath his feet and the fire of battle in his eye.

Thither, too, came the indomitable Scot, precisely as he came in the Colonial and Revolutionary days. "The Lowland race," says Mackintosh, "Briton and Norman and Saxon and Dane, gave the world a new man—the[Pg 25] Sea Rover, the Border Soldier, the Pioneer.... The folk speech, from Northumberland to the Clyde and the Forth, is Northern English or Lowland Scotch; and the future man of Bannockburn and King's Mountain is beginning to appear. He is the man with the blood of the Sea Rover mixed with the blood of the Borderer, and the soldier, the scholar and thinker, the statesman and lawyer, the trader and farmer." He is the man that crossed the Blue Ridge Mountains as a pioneer. He is the man that sat in the conventions that organized the State, and stood in an unbroken line in all the pioneer battles of his race. The earliest migration of the Anglo-Norman folk was to the Colony of Virginia, as many of the old Virginian surnames, Bacon, Baskerville, Boys (Bois), Cabell, Clay, etc., clearly attest; and the State of Kentucky deriving a large population of English descent from Virginia, we should naturally find a strong infusion of Anglo-Norman blood in the people of this State—an inference fully sustained by the transcript of Anglo-Norman surnames which the writer made from the list that he found in the great Library in London.

The late Professor Shaler is frequently quoted to the effect that ethnological research discloses the existence in Kentucky of the largest body of nearly pure English folk to be found on the face of the globe—that has been[Pg 26] separated for two hundred years from the parent English stock. But the facts do not warrant the assumption that the Kentuckian is of purely "Anglo-Saxon" derivation. In him, at least, the blood of the Norman is not wholly lost. He is, however, as Professor Shaler says, an "Elizabethan" Englishman.

We print elsewhere a list of names familiar to Kentuckians, which clearly points to the same general conclusion. With more leisure and space this list might be greatly extended.

But what are the characteristic traits of the Norman as we find him in his early habitat in France? We are told by a contemporary observer—Geoffrey Malaterra—that the typical or "composite" Norman of his day was prodigiously astute, a passionate lover of litigation, an eloquent speaker, skilled in diplomacy, sagacious in council, convincing in debate; a son of the Church, but not too deferential to prelates nor too precise in the observance of ecclesiastical forms; a bold and tireless litigant, but not over-scrupulous in his methods of procedure and not always strictly judicial in his construction of the law. "If he was born a soldier," said Edward Freeman, "he was also a born lawyer." In spite of this pronounced legal penchant he was swift (if not restrained) to disregard and override the law; in the phrase of the old chronicler, the gens was effrenatissima—recklessly wild, unbridled and dangerous, nisi jugo justitiæ prematur; daring, resolute, destructive in mutiny or revolt; seditious, piratical or even revolutionary, unless the reins of government were in strong and competent hands.

We had a notable mid-century exemplification of this "unbridled" quality of temper in the introductory razzia of Lopez at Cardenas. When the Kentuckians, whose[Pg 28] unerring rifles had crumpled up the Spanish cavalry and successfully covered the slow retreat of Lopez to the sea, were followed by the pursuing warship Pizarro into the harbor of Key West, nothing daunted they coolly seized the United States fort, took possession of its batteries, and deliberately trained its guns upon the Spanish man-of-war. Gens effrenatissima, indeed. The fighting habits of the Liberators were notoriously loose (especially under tropical suns); but what is to be particularly noted in this instance is, that the reins of power in our highly civilized government were unpardonably lax. It is possible, however, that the reckless and "unbridled" conduct of the Kentuckians was due, in part, to the circumstance that the chaplain of the Expedition had been killed.

The subsequent official investigation showed to the entire satisfaction of our Anglo-Norman lawyers that practically everything had been done under "the forms of law."

The word effrenatus was almost overworked by Cicero. It perfectly described the Catilines of old Rome and the banded ruffians that wrought their will. But in his very lawlessness the Norman of Malaterra never forgot the law. He scrupulously observed its "forms." Even the Conquest of England was "justified" by a pronunciamento of legal assumptions subtly and elaborately drawn. The[Pg 29] Norman was a shrewd and successful trafficker, and this tradition of commercial skill and thrift is current in Normandy to-day. When he settled on English soil or sailed in English ships he did not lose his inherited commercial instincts. He made England the trading nation that she is. An eminent Kentuckian, who bore the distinctive marks of Norman blood, once said to a group of keenly attentive listeners, "The meanest of all aristocracies is a commercial aristocracy." A like disparaging conception of a powerful adversary was implied in the remark attributed to Napoleon, that "the English were a nation of shop-keepers"—un peuple marchand. It was this same race of innocuous Anglo-Norman traffickers that crushed Napoleon's iron columns at Waterloo, and forever closed his conquering career. But the Norman, who was a soldier, a lawyer, a diplomatist, orator, hunter, horseman and trader, was also a successful cultivator of the soil, and the Norman agriculturist of to-day who reminds the tourist in his physical traits, hair, eyes, and complexion, and even in the intonations of his voice, of an English farmer of the Anglo-Norman type, bears a more striking resemblance to his English kinsman indeed than to his dark-visaged compatriot, the vigneron of Southern France. We must add, to complete the portraiture left us by Malaterra, that the Norman was a passionate lover of[Pg 30] horses, of the breed immortalized by the genius of Bonheur; a bold equestrian, skilled in the use of arms; at home upon the sea, and literally reared in the lap of war. And he was also a brilliant orator, passionately fond of eloquent speech. From his early boyhood, says the chronicler, he assiduously cultivated his natural aptitude for that persuasive art, that power of ready and effective utterance which, though often profane, made him dominant in the councils of war and of peace; in the cabinets of diplomacy, and even in the chamber of the King. Gens astutissima beyond all doubt.

To return to our beginning—what think you was in the mind of Paul Du Chaillu as he stood that memorable evening before an audience of mid-century Kentuckians?—this philosophic thinker who had been for years a critical observer of "the most dramatic spectacle in history"—the sweeping, ceaseless, transcontinental march of the Anglo-Norman race—what did he think of the environing conditions as he stood in that old Courthouse which had resounded with the eloquence of Anglo-Norman orators; which had echoed and re-echoed generation after generation to the "Oyez!" "Oyez!" of Anglo-Norman sheriffs? and which was still standing, an impressive memorial of days when the ground upon which it was built was the camping-ground of the dominant figure in[Pg 31] this Westward march—the Anglo-Norman leader Boone or "Bohun"—a name which in its very sound or utterance (mugitus boum) was in "dark and bloody" times a challenge to mortal combat—a deep bellowing defiance of "battle to the death"?

What were his thoughts as he looked with wondering eyes upon that charming Southern matron with her fair, delicate features and high-bred air? Was the vision a vivid reminder of blue-eyed "Scandinavian" maidens with faces as white as their native snows and locks with the softened shimmer of the midnight sun? One must acknowledge that the very exquisiteness of form and tint made this a rare type, even in Kentucky, but there were many interesting variations of it to be seen at our great mid-century "Fairs"—from the rich "auburn" of Marie Stuart to the "carroty" tresses of the Virgin Queen—framing lovely faces and crowning tall, willowy figures of queenly mold. But probably the prevailing tint of hair was that ascribed by the wizard romancer to the Lady Rowena—with her dash of Scandinavian blood—something between flaxen and brown; all in clear and brilliant contrast with a type that glowed with the superb brunette finish of Southern and Central France. Had Du Chaillu been with us in earlier days we could have shown him likewise figures of a striking masculine type—tall, soldierly figures[Pg 32] that might have graced the "Viking age"—men who, after the fashion of early Norman days, would have been equally at home in camp or court. One of these gallant gentlemen, whom many of us remember, was in some respects a striking counterpart of a Scandinavian sailor that figures in a late romance, "Wolf Larsen"; like him even in the soubriquet prefixed to his Scandinavian name; of gigantic stature and strength; big-brained, passionate, strong-willed, energetic, proud, combative and sagacious, with a deep instinctive love of the sea. But his chronic irascibility of temper, often manifest on trifling provocation in unbridled bursts of Berserker rage, sadly marred the brilliancy of his military career, and engendered deep and implacable enmities which brought his career as a soldier to a speedy and tragical close.

In other respects he radically differed from Norsemen of the Wolf Larsen type. In his relations with his family and friends he was delicate, generous, and kind; the tenderest of sons, the kindest brother, the most devoted and loyal of friends: a lover of literature, music, and the finer pleasures of social life. Strangest of all, he was reverent and devout. He respected the forms of the Church, and every night, even in the rude environment of the camp, he knelt beside his soldier's couch and repeated the Lord's Prayer. But the soubriquet fastened upon[Pg 33] him both by resentful enemies and admiring friends recalls his fictitious counterpart—Wolf Larsen. Whenever the name of the Federal commander came up for discussion during our great Civil War—whether in Confederate camp or by Kentucky firesides, or by the campfires of his own loyal division—he was invariably known, by reason of his huge figure, his big bovine head, his flaming black eyes, his fierce, tumultuous energies, his headlong courage and gigantic strength, by the soubriquet "Bull"—BULL NELSON—a sea-trained soldier with a bellowing soubriquet prefixed to an honored racial name—a mid-century Kentuckian, who in mediæval battle might have swung the battle-axe of Front-de-Bœuf.

There were many others—Kentuckians of an ideal Anglo-Norman type—who would have brought to M. Du Chaillu the strongest confirmation of his philosophic views had he visited us during the cyclonic "sixties," or in that halcyon interlude "before the war."

Returning now to the discussion of the masterly paper read by M. Du Chaillu at the British Association,[4] we may consider certain aspects of the question more in detail; conceding at the same time full credit to the ability of the disputants who dissented from the views expressed by the foreign savant. M. Du Chaillu was peculiarly fortunate in his critics. If his theory should survive the searching and trenchant criticisms of such men, his scholarship would command respect even if they should decline to accept his conclusions in full.

A loyal Briton does not lightly abandon what he conceives to be established or traditional views. This trait does not imply defect of philosophic insight or want of wide research. It denotes simply the influence of prepossession, opinionated habit, and conscious power. Nor is this influence unusual. Scholars differ even as "doctors" disagree. Dr. George Craik, whose name is familiar to every scholar of the English race, was liberal enough to concede, a quarter of a century before the advent of Du Chaillu as a Scandinavian protagonist, that the English language might have more of a Scandinavian than of a purely Germanic character; or, in other words, "more nearly resembled the Danish or Swedish than the modern[Pg 35] German." The invading bands, he adds, by whom the dialect was originally brought over into Britain in the Fifth and Sixth centuries, were in all probability drawn in great part from the Scandinavian countries. At a still later date, too, this English population was directly and largely recruited from Denmark and the regions around the Baltic. Eastern and Northern England, from the middle of the Ninth Century, "was as much Danish as English." In the Eleventh Century the sovereign was a Dane.

M. Du Chaillu's theory rests upon other and perhaps stronger grounds, but these concessions from a thoughtful scholar at least will carry weight. The continuous existence of Scandinavian influence in England is suggestive of the circumstance that the Danish conquest of England preceded the Norman conquest by "exactly half a century." An Englishman (Odericus Vitalis), writing almost contemporaneously with the Norman conquest, describes his countrymen as having been found by the Normans "a rustic and almost illiterate people" (agrestes et pene illiteratos). And yet, says Dr. Craik, the dawn of the revival of letters in England may properly be dated from a point about fifty years antecedent to the Norman conquest. To what, then, must be ascribed this scholastic renascence? Very clearly to the intimate relations estab[Pg 36]lished between England and Normandy by Edward the Confessor. But there is no trace of the new literature (that of the Arabic school which was prevalent in Europe) having found its way to England "before the Norman conquest swept into the benighted old kingdom, carrying the torch of learning in its train." The name of Lanfranc alone gives splendor to that civilization which his genius created for the English race. He not only lighted the torch of learning, but he strengthened the reins of power. He restrained the lawless impetuosity of William the Conqueror; he imposed iron conditions upon the accession of William Rufus; he checked the atrocities, and finally broke the power, of Odo of Bayeux. His work was well done, and its effects are visible to this day. He was the real power behind the throne. It is not easy, says an eminent English writer, to trace through the length of centuries "the measureless and invisible benefits which the life of one scholar bequeaths to the world." But such was the life, the work, the bequest of this Norman scholar, who died honored and beloved even by the rude, sullen, and implacable race which had been subjugated by the Norman kings. But Dr. Craik, with all his liberality and learning, is not disposed to accept the theory of a great migration or settlement preceding, or accompanying or following, the Norman conquest in the Eleventh Cen[Pg 37]tury. To be sure, this theory was not elaborately or effectively presented until of late years; but Dr. Craik, writing as far back as the opening of our "War between the States," seems to contradict this theory by anticipation—"In point of fact, the Normans never transferred themselves in a body, or generally, to England. It was never thus taken possession of by the Normans. It was never colonized by these foreigners, or occupied by them in any other than a military sense. It received a foreign government, but not at all a new population." Yet even Dr. Craik seems to appreciate the lesson of "names." He thinks it remarkable, for instance, that though we find a good many names of natives of Gaul in connection with the last age of Roman literature, scarcely a British name has been preserved. Even in Juvenal's days the pleaders of Britain were trained by the eloquent scholars of Gaul. The significance of a name in determining family origin is a common assumption of our familiar speech. "That is a Virginian name," we say; and if we find many Virginian names in a given locality we naturally infer that the town, or the county, or the locality, large or small, was originally settled by Virginians. In one of our old Bluegrass counties two of these settlements were made in pioneer times, about two miles apart. One is known as "Jersey Ridge," the other as "Tuckahoe." If in both localities we find[Pg 38] an English stock with Anglo-Norman names we should naturally assume a common derivation from the Anglo-Norman branch of the great British race.

But that accomplished philologist, Dr. Craik, seems to be quite in sympathy with the views of Du Chaillu touching the ancestral relations of the Scandinavian to the English race; and Dr. Craik's eminent American compeer, Mr. George P. Marsh, is not hopelessly wedded to fixed conclusions, and has by no means overlooked the obvious Scandinavian affinities of the English tongue. "Almost every sound," says the latter, "which is characteristic of English orthoëpy, is met with in one or other of the Scandinavian languages, and almost all their peculiarities, except those of intonation, are found in English; while between our articulation and that of the German dialects the most nearly related to the Anglo-Saxon there are many irreconcilable discrepancies." If to determine the relative proportions of linguistic and ethnic elements in dialect and race were "a hopeless and unprofitable task," this would seem to invalidate all general conclusions in the matter.

A few days after the very lively discussion of M. Du Chaillu's epochal paper in the Free Library of Newcastle, there appeared in a great newspaper a contemporary estimate of his views, which was received by its multi[Pg 39]tudinous constituency with profound interest and respect. It was the rolling voice of "the Thunderer"—the famous London Times. In all crises in the national life, the influence of this journal is felt. It is not a mere priestly oracle, silent except at times, but a divinity that never ceases to speak; clothed with strangely beneficent powers, and in the exercise of legitimate influence as resistless as the fabled might of the Scandinavian Thor. It forms opinion;—it fixes opinion;—it reflects opinion;—it gives effect to the popular will. It has been felicitously characterized as the "vast shadow of the public mind."

On the 21st of September, 1889, the Times, after a full report of the ethnological discussion in Section H, had this to say by way of editorial comment: "Perhaps the great sensation of the Section was M. Du Chaillu's paper, intended to prove that we are all Scandinavians.... This paper, combined with that of Canon Taylor, and the discussion that followed both, seemed to show that the time is ripe for a perfectly new investigation of the whole question of the origin and migration of the races which inhabit Europe and Asia; and, that, on lines in which language will play only a subordinate part."

Thus much for the startling theory discussed by the Anthropological Section at Newcastle.

In a subsequent correspondence, which appeared in the London Times, M. Du Chaillu challenged archæologists[Pg 40] to point out remains in any other part of Europe so like those of the early Anglo-Saxons in England as the relics he figures from Scandinavia in England. It is not always easy to indicate with precision the cradle of an ancient race; and even if such remains were found on the coasts of Holland and North Germany, the discovery would not seriously affect the conclusions that seem to have been reached as to ancestral relations of the Scandinavian and the Norman to the English race in England and the United States. One might abandon altogether the main line of M. Du Chaillu's argument, (1) his careful analysis of the Sagas and other ancient documents and (2) his comparison of the antiquities upon which the challenge rests, and yet there would remain something more than a strong presumption that the animating principle of the English race, in its leading branches, is the Scandinavian blood. It would seem to be quite in conformity with the law of nature that the daring, crafty, and indomitable race which still shapes the political destinies of men, which is historically traceable in its schemes of conquest and subjugation for a thousand years, and which is precisely traceable upon geographical lines in its movements of colonization or war, should have derived its enterprising characteristics from the only race which has demonstrably transmitted its conquering and colonizing traits within historic times:[Pg 41] to wit, the Scandinavian pirates that were conceived upon stormy waters, spawned upon an icy coast, and swept, apparently in a career of predestined conquest, from the waters of the Baltic to the ends of the earth. The nations shrank from the Rover in fear. The Frenchman, at least, learned to dread his power, and the Saxon submitted with sullen acquiescence to his rule. He sowed the seed of conquest with his blood, and upon whatever shore he drove his keel he planted himself fiercely upon the soil to stay. Is it to be supposed for an instant that this puissant racial force was dissipated and lost? Not so. The light, the fire, the sweep, the coruscating energies, the resistless currents, the driving forces are still there. The power is not "off"!

Nevertheless, it may be—to use the phrase of the London Times—that "the time for a new investigation of the whole question is now ripe."

Those were stirring days in the old Northumbrian city by the sea. And to the utmost border of that ancient kingdom the busy populations were alive with expectation and hope. Little cared they for the Sea Rover now. He no longer enjoyed, as once, the freedom of the city and the sea. They were really as indifferent to the vexed question as the philosophic Canon Taylor humorously affected to be. The loquacious savants might settle matters to suit themselves; but there was another question, probably of equal importance, for popular consideration; and a question of far greater moment too, to a man with blood in his veins; a question which touched at once the pocket and the heart; to wit, the last of the classic races at Doncaster, the St. Leger and the great Yorkshire Stakes. Will the Duke of Portland's "Donovan"—a Southern horse of great beauty, speed, and "luck"—win in the coming contest with "Chitabob," the pride and hope of the North? There was anxiety in every face. The touts had come from their work at Doncaster, and Chitabob was reported to be lame; his old enemy (rheumatism) had seized his foreleg; he was not equal to a canter: could do only three hours' walk in the paddock near the ring. In spite of the conditions and the resulting con[Pg 43]sternation of Chitabob's friends, his nervy young owner insists that "matters are not so bad as they seem, and the horse will run." Meantime, the betting is against him—two to one on Donovan; in rapid sequence six—seven—ten against Chitabob. The situation was highly sensational; the state of excitement in Doncaster was intense; even Chitabob's friend, "Guyon" (a noted sportsman), had surrendered hope. The owner, young Mr. Perkins, was alone undismayed; and the men of the stalls were as game as the horse. "He can win on three legs," they declared. "I do not think so," said Guyon, "and though common sense prompts me to go for Donovan, I am full of hope and sympathy for Chitabob. The splendid fellow has always carried my money, and I will back him to-day. He is too grand a horse to let him run loose, but it is very clear to my mind that Donovan will win." The loyal sportsman proved to be an infallible prophet—Chitabob lost.

As one looks intently upon such a scene as this, Doncaster disappears and Kentucky rises on the eye. The story of Chitabob recalls the traditions of Grey Eagle, that superb and exquisite idol of the mid-century Kentuckian's heart; his brilliant and exciting contest with Wagner; his gallant start, his matchless stride, the vast crowd, the wild applause;—"the strained tendon," the[Pg 44] slackened speed, the failing strength—the lost race. But the defeated racer was always (like Clay or Breckinridge) the idol of the State;—the Champion of Kentucky—as Chitabob was the Champion of the North.