Project Gutenberg's Fifteen Hundred Miles An Hour, by Charles Dixon This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook. Title: Fifteen Hundred Miles An Hour Author: Charles Dixon Illustrator: Arthur Layard Release Date: August 16, 2015 [EBook #49713] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK FIFTEEN HUNDRED MILES AN HOUR *** Produced by Dagny & Marc D'Hooghe at http://www.freeliterature.org

CONTENTS

CHAPTER I.

WE PREPARE FOR OUR JOURNEY

CHAPTER II.

WE LEAVE EARTH IN THE "SIRIUS"

CHAPTER III.

OUR VOYAGE BEYOND THE CLOUDS

CHAPTER IV.

AWFUL MOMENTS

CHAPTER V.

THE GLORIES OF THE HEAVENS

CHAPTER VI.

WE NEAR MARS

CHAPTER VII.

OUR ARRIVAL AND SAFE DESCENT

CHAPTER VIII.

A STRANGE WORLD

CHAPTER IX.

THE MORROW—AND WHAT CAME OF IT

CHAPTER X.

CAPTIVITY

CHAPTER XI.

LOVE AND JEALOUSY

CHAPTER XII.

CONDEMNED TO DIE

CHAPTER XIII.

THE CRAG REMAGALOTH

CHAPTER XIV.

ACROSS THE DESERT CHADOS

CHAPTER XV.

RIVALS MEET AGAIN

CHAPTER XVI.

VOLINČ

CHAPTER XVII.

AT THE TEMPLE ON THE HILL VEROSI

CHAPTER XVIII.

THE FIGHT FOR VOLINČ

CHAPTER XIX.

WEDDED

CHAPTER XX.

THE LAST WORDS FROM YONDER

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

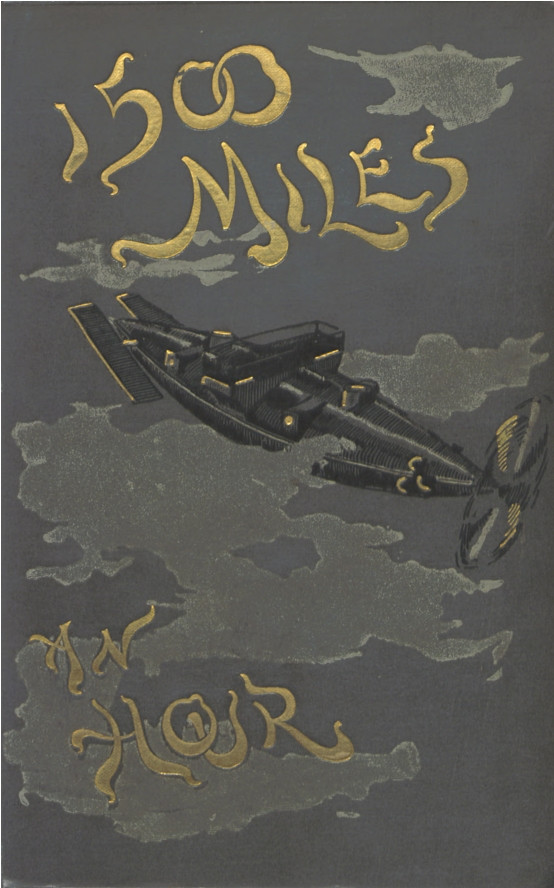

"OUR VOYAGE BEGINS AT LAST" Frontispiece

"ALONE IN SPACE"

"ITS HUGE SCALY CARCASE"

"VOLINČ"

"... THE 'SIRIUS' ... BOLDLY OUTLINED AGAINST THE SKY"

"SCORES OF STRANGE BEASTS HURRIED OUT FROM UNDER THEM"

The narrative contained in the papers which are given to the world in this book, is of so marvellous a character as to have made me long hesitate before venturing on their publication. Even now I do so in the full expectation of scorn and unbelief.

I owe it to the world to state exactly how these papers came into my hands. That done, I must leave it to their own appearance of truth to command belief.

The year before last, I was travelling through Northern Africa on a scientific expedition. It was early in the month of May that I reached the northern confines of the Great Desert, amongst the feathery palm-groves in the delicious oasis of Biskra.

I had started one day, with the first streak of dawn, upon a short expedition into the desert. My two Arab followers were anxious to cover as much distance as possible before the heat of the sun became oppressive.

It was about ten o'clock before we halted for breakfast, and the oasis of Biskra looked but a black spot on the northern horizon. The heavens up to now were an intensely brilliant blue, but a dark cloud far away over the distant desert could be seen rapidly increasing in size.

Gradually the whole vault of sky assumed a coppery aspect, and the sun shone paler and paler each moment. The heat and oppressiveness were almost unbearable; not a breath of air relieved the suffocating atmosphere. The sun finally disappeared behind the curtain of lowering cloud, and a darkness began to creep over the earth. The Arabs prepared for the storm which they knew from experience was brewing. The dreaded sandstorm was approaching. It came on the wings of the southern gale with terrific speed, and suddenly the air became almost as dark as midnight, full of fine blinding sand. We could not see twenty paces ahead; and now the sluggish atmosphere was stirred with the rushing and shrieking of a mighty wind.

As I gazed for one brief moment upwards during a lull in the storm, my eyes were almost blinded by a brilliant light, brighter than the flame from an incandescent lamp, and a thousand times as large, which seemed to shoot from out of space. At the same awful moment the very dome of heaven seemed cracked asunder by a loud report, different from anything I had ever heard before. It was a solid and metallic sound, louder and sharper than the report of tons of exploding nitro-glycerine. The earth shook and trembled to its utmost foundations, and the rocks seemed to recoil at the frightful explosion. The Arabs were struck dumb and motionless with horror, and I, for several moments, was as one stone-blind. With the report a huge body seemed to have struck the rocks a short distance from us, but it was impossible to tell what it was until the fury of the storm was somewhat spent. The worst was now over; and the sand, the thunder, and the darkness vanished almost as suddenly as they came. But we did not venture forth until the welcome, glorious sun shone down again upon the wet rocks; and then the Arabs engaged in fervent prayer to Allah for our miraculous deliverance from a terrible fate.

Almost the first object that my eyes rested upon, as soon as we left our retreat under the rocks, was a large round mass of dark-looking substance, a hundred yards away. In amazement I walked towards the spot where it lay hissing and steaming on the bare, wet rocks, surrounded by a thick coating of hailstones, which the hot sun was rapidly melting. It was a meteorolite of unusual dimensions, measuring exactly three feet nine inches in height, and was shaped like a huge gourd. A large crack extended completely down one side, about an inch across in its widest part.

I cautioned the Arabs to preserve the strictest secrecy, and made them swear by the Prophet's beard that they would reveal to no man what they had seen, and then we returned to Biskra. It was my intention to obtain a few suitable tools and requisites, and then return to the meteorolite at once to investigate. It would evidently take some hours to cool; besides, if we did not get back, search parties would be scouring the desert in quest of us, and they might by chance discover this wonderful "stone." I felt already that this stone belonged to me. My interest in it was all-absorbing.

Early the next morning, with three Arabs, I went off, armed with wedges, a heavy hammer, some drills, a quantity of gunpowder, and fuse. We found the stone just as we left it on the previous day, and evidently still unvisited by man.

I first of all tried to force open the crack with the wedges, but the substance was exceedingly tough, the appliances at my command very crude, and I made no progress. Then I set my followers to work to bore two holes into the "stone," and fill them with gunpowder. This plan worked admirably—the drill cutting its way through the soft spongy mass with great quickness, and I was soon ready to fire my fuse, and retire behind the rocks to wait events.

It was an anxious moment for me. We had not to wait long for the reports, which sounded like a couple of rifle cracks, and then we ran forward to examine our prize. Alas! it was shattered into fragments, some of them blown to a distance of many yards.

The charges were too strong. I was profoundly disappointed, and set the Arabs to work to gather up the largest pieces and load our camels with them.

I was sitting dejectedly enough upon the sand, more interested in the action of a pair of vultures than in the doings of my men, when Achmed, one of my Arabs, made his appearance, holding in his arms a very curious-looking fragment of the meteorolite. It looked like a rusty piece of iron ore, oblong in shape, and had evidently undergone great pressure. Examination told me that this substance was iron, and its disproportionate lightness, together with a blow from the hammer, revealed the fact that it was not solid! It looked for all the world like a large conical shot. I set off alone on my camel to the oasis, all impatient to get home and examine my prize.

I could neither eat nor sleep until I had finished my task. Locking myself in my room, I began my investigation with a singular presentiment that I was on the eve of some important discovery. Nor were my feelings unjustified by events. With the aid of a hammer and chisel, after some considerable trouble and labour, I broke open this singular-looking mass of battered rusty iron, and its strange contents rolled out on to the table! Of what were they composed? Nothing but a long and carefully-folded pile of papers—so tightly packed that they might have been under hydraulic pressure; but their appearance filled me with the intensest surprise and most utter amazement! Here and there the edges were burnt and charred, but otherwise they were in a singularly good state of preservation, and the writing upon them was almost as legible as when it was penned. The paper had evidently been made on earth, for it bore the watermark of a well-known London firm.

The most singular part of all this strange occurrence, however, remains now to be told. Most of these manuscripts were written in a good, bold, upright hand, and they were addressed and dated from

"The City of Edos, Planet of Mars, or Gathma. December the 9th, 1878."

Was I awake or dreaming? Many times did I read those three lines, walking about the room meantime to convince myself that all was reality! This strange letter from an unknown world must have been ten years in the air! These manuscripts were evidently of a scientific as well as of a popular character; and as a scientific man myself, I felt already that a bond of sympathy existed between my unknown correspondent far away out yonder beyond the sky, and myself! A voice from another world; a message from the vast unseen—how I longed to read these papers, to examine them, to revel in their secrets, and to enjoy them! What a hidden world of wonder, of adventure, of exploration, lay before me if the documents were genuine!

I sat up the entire night, eagerly reading through these strange papers.

Africa had now, for the present, lost its charm. I set off back again to Europe with all despatch, bent on investigating the whole matter.

Fortunately, my efforts were crowned with a most gratifying triumph.

Doctor Hermann, F.R.S., F.R.A.S., F.R.G.S., the author of a considerable portion of these manuscripts, I discovered had been an eccentric and little-known individual, living a very secluded life on a small estate near the Yorkshire fells, a wild lonely spot, far from cities. That he was a member of the Royal, the Astronomical, and the Geographical Societies, I easily satisfied myself. He had been absolutely devoted to science—for this all the other enjoyments and obligations of life were discarded; he lived but for one object, the study and investigation of Nature's choicest secrets. This was the all-absorbing faith of his life. From information supplied in these manuscripts, I learned the exact place of his strange abode, and was able to visit it, and to make many enquiries in the immediate neighbourhood concerning him. He was described to me as a tall, spare man, with a benevolent-looking face, past the prime of life, with grey beard and moustache, clear grey eyes, and close-cropped hair. In nature, gentle and tender as a woman, but brave as a lion, and with a reputation for firmness and great strength of will. I was also told that he had a very big telescope erected in his barn, and some of the old folks living in the fells always insisted that the Doctor and the Devil were on quite too intimate terms. He had no friends in the neighbourhood. One old serving-woman used to look after the house, but she had been dead some years, and had not been on speaking terms with any of the good people living near. His man-of-all-work, Sandy Campbell, generally accompanied his master in all his wanderings. Sandy was almost as much of a character as his master—a close, reticent Scot, who could never be got to talk, even when under the influence of whisky, a liquor he appeared to have been particularly fond of. The Doctor had few visitors. John Temple, a Bradford cotton lord, had been often seen in his company; and a young engineer from Leeds, called Harry Graham, had been also known in the neighbourhood as a frequent guest of the Doctor's. Singularly enough, these names were the ones given in the manuscripts, and therefore help to confirm their truth.

I also learnt that, some fourteen years ago, Doctor Hermann and his man suddenly disappeared from the neighbourhood, and it was said they had gone abroad on a scientific expedition, the house having been denuded of its furniture and left standing empty. From that day to this, no one had occupied the premises. Pursuing my investigations further, I found that at precisely the same time John Temple, the Bradford millionaire, left this country, presumably on a voyage round the world; and enquiries at the great firm of manufacturing engineers in Leeds also revealed the fact that this Harry Graham, their cleverest manager, left their employment to go abroad at the same date. Not one of these persons has been heard of since.

The mystery of all these persons disappearing at the same time, and never being heard of again by mortal man, is now cleared away! I hold the secret, which was flashed to me on the wings of the storm, from boundless space, upon the sands of the Sahara. The following weird and startling story will satisfactorily explain the cause and purpose of these individuals' departure, minutely describe their wonderful and thrilling experiences, and publish to the world the reason why the lonely house on the Yorkshire fells remains tenantless, and is rapidly falling into ruins; and the rich estates of John Temple, cotton lord and millionaire, are still amongst the unclaimed treasures in the jealous keeping of the High Court of Chancery!

The following is in the Doctor's bold and characteristic handwriting.

Extract from Dr. Hermann's instructions to the finder of the MSS.

"Should these manuscripts chance to fall into the hands of any civilised man, it is my earnest wish, though of German extraction myself, that they should be published—if published at all—in the English tongue. Truth shall prevail, and our return to earth shall scatter, like thistle-down before the autumn winds, the scepticism which I mistake not will encircle them, as soon as man may read them. It is my cherished hope to return to my mother world, and to tell in person of that glorious life and those sublime wonders of a New World. Adieu!"

This brief extract must suffice as introduction. The next chapter will begin at once with the story proper, omitting the uninteresting preliminary portion of the manuscripts.

Fifteen Hundred Miles an Hour

"I tell you, Temple, that the thing can be done! From experiments which I have carefully made, and from information which I have laboriously collected during the best part of a lifetime devoted to scientific research, I am in a position confidently to state that my project is removed for ever from the realm of possibility, and is now within measurable distance of becoming an accomplished fact. My plans may seem complicated to you, but to me they are simple in the extreme. You, my dear fellow, are better able to deal with intricate financial questions, discounts, stocks, and bank rates, rather than the delicate experiments of science. Believe me, I have here in this book every item of my scheme carefully worked out, every design outlined to its simplest detail—all I want is the necessary capital for its accomplishment. My young friend, Harry Graham, here—let me introduce him to you, Temple—whose interest in astronomy I have long been fostering, is willing and ready to superintend the mechanical portion of my undertaking. Our models have turned out satisfactory in every way—all we want now is money. That, friend Temple, you half-promised years ago. May I count upon your assistance still?"

"My dear Doctor, you may. If fifty thousand pounds, aye, or even a hundred thousand, will help you, I am willing to speculate to that amount; and, what is more, the novelty of your undertaking has so captivated me that I am anxious to form one of your party. Who knows, if your efforts are crowned with success, what grand financial harvests may be reaped!"

"Then, Graham, there is nothing now to prevent us beginning to work in real earnest. There is much for us to do; and I am sure we shall deem it an honour to have the financier of our undertaking in our company. Try another cigar, friends, and let Sandy bring us one more bottle of port, and then I will endeavour to give you a brief outline of my plans."

"As you know," continued the Doctor, "I have long been an ardent supporter of the theory of the plurality of worlds. I am a firm believer in the principle of Universal Law; and the theory that these other worlds are the abode of living organisms is to me an almost demonstrable fact. When I first began the study of this interesting question I soon came to the conclusion that the only planet with which I dared hope to obtain any success must be one whose conditions were as nearly like those of our own world as possible. So far as I know, only one orb in the entire planetary system can with any degree of fairness be compared with Earth. That planet is Mars. In short, the beautiful planet Mars is precisely similar in nearly every physical aspect to the Earth—it is, in fact, only a smaller edition of our own world.

"But I am afraid I weary you, Temple, with all this scientific detail. I will not trouble you with more, but come to the practical side of my plans."

"Doctor, your remarks interest me exceedingly. Pray, say all you think desirable."

"Well, then, Temple, the first difficulty I had to contend with was that of bridging the mighty distance between our Earth and this planet. My second task was the enormous journey itself, and the means of obtaining air and sustenance during the progress. Both of these, after many experiments and many failures, have been overcome.

"First, as to my means of conveyance. I have here a design for an air carriage, propelled by electricity, capable of being steered in any direction, and of attaining the stupendous speed of fifteen hundred miles per hour. It can be made large enough to afford all necessary accommodation for at least six persons, and its attendant apparatus is capable of administering to their every requirement. Here is a model of the machine. You will perceive that the material of which it is composed is no metal in common use, nor is its composition, and the method of its manufacture, known to any mortal man but myself. It is remarkable for its extreme lightness, toughness, and power of withstanding heat. Wrought-iron melts at something like 4,500 degrees Fahrenheit; my metal will stand a fiery ordeal three times as great. This is of the utmost importance, for our high rate of speed would soon generate sufficient heat to melt any but the most enduring substance. Here, again, is the exact model of another apparatus for making and storing electricity sufficient for at least two years, working at high pressure. And herein perhaps is the greatest of my discoveries. The one grand problem which electricians have to solve before this force can be of any great advantage to mankind is the method of generating it direct, without the aid of any other motive power. I have solved that problem; and have succeeded by the aid of this curious apparatus in producing electricity direct, not from coal, but from petroleum. By this wonderful invention I am able to carry enough fuel for our journey, compressed into a space that is practicable for all requirements, and the alarming waste of energy that now troubles the electrical engineer is saved. The labour of the world will now be revolutionised when I choose to make my discovery known; for the reign of steam, glorious and wonderful as it has been, will then be over. I can carry in my hand enough fuel to drive the biggest steamer that ploughs the ocean, once round the world.

"But to return. This little attachment tells the exact rate of speed the carriage is travelling. You will also perceive that my motors are on the principle of the paddle-wheel and the screw-propeller combined. The interior of my carriage is formed of a series of chambers one above the other. There is a laboratory, sleeping and living chambers, engine and apparatus room, and ample space for stores in the basement. The door is situated near the top, and just above it I have placed, as you see, a small balcony, for observations. My port-holes will be glazed with glass of exceptional quality, made by myself, and every apartment is lighted with electricity. The carriage is conical in form, that shape being best adapted to a high rate of speed.

"My next consideration was the supply of air. I think we shall find that the whole planetary system is pervaded with an atmosphere so rare, in some parts of remotest space, as to remain undetected by any instrument yet known to science, but still of sufficient density to offer resistance and lend support to our carriage and its propellers. My condensers are so formed that they will readily convert this ether into air suited to man's requirements.

"I had now but one more task to overcome—food and water. As regards food, I have here a little cake of animal and vegetable substances which have undergone a certain chemical process, by means of which I have been able to compress enough food to support a human being for three days into a space not quite two cubic inches in extent. In this other tablet I have dealt with wheaten flour in a similar satisfactory manner. Tea, sugar, and other luxuries I can reduce to the smallest proportions by a process of condensation and hydraulic pressure. So that I can stow away in the store-room of my carriage enough food to last six persons for nearly three years—a more than ample supply, as I intend shortly to demonstrate.

"It has taken me nearly ten years to solve the problem of my water supply. I have here a small electrical apparatus, by means of which I hope to be able to distil water from ether. Should my experiment fail, I have invented a small lozenge of soda and other chemicals, which will allay thirst. I must also say that I have allowed sufficient space for scientific instruments, a stock of methylated spirits, a selection of books, firearms, and ammunition: nor have I omitted clothes, cigars, tobacco, a few bottles of wine to be used on state occasions, and a fair quantity of brandy and whiskey, so that you, Temple, shall not be without your grog. A medicine chest, camera, and india-rubber boat are also included in my list of necessaries. I calculate that my air-carriage will be about forty feet in height, and nine feet in width. What I have disclosed is but a portion of my grand scheme, the one great work of my life, from which I hope to obtain the most brilliant scientific results.

"The planet Mars will reach his perihelion, or nearest distance to our Earth, in October, 1877. He is then in an unusually favourable position, and affords us a chance of visiting him, which will not occur again in a lifetime. Now, I calculate that our rate of speed will be fifteen hundred miles per hour, so that the thirty-four millions of miles we have to traverse will be accomplished in about two and a-half years' time. We must leave Earth, therefore, not later than the first day of May, 1875. Our stay, of course, will depend on circumstances, which no mortal man can foresee. We may, indeed, reach our destination in much less time than I have anticipated.

"I ought here to mention," continued the Doctor, "that my devoted servant, Sandy, has already expressed his desire and willingness to accompany me on this long journey.

"Now, Temple, and you too, Graham, I wish you to weigh carefully the pros and cons of this dangerous enterprize. We are about to embark into the solemn, boundless realms of space—to dash boldly away from the Earth, which fosters us, into mysterious regions of which we have none but the scantiest knowledge. On the other hand," continued the Doctor, "there is grandeur in the thought of being able to leave this world of ours for a season, and to visit those orbs which shine so clearly in the midnight sky. If you, of your own free will, are ready and willing cheerfully to cast in your lot with mine, I shall be happy in your company."

There was dead silence for several moments after the Doctor had finished speaking, during which the little timepiece on the mantel struck the hour of midnight with almost painful clearness, when Graham was the first to speak.

"Doctor, you know that, through all the experiments we have conducted together, my one aim has been, provided they were successful, to accompany you."

Temple spoke next.

"The ties, my dear Doctor, that bind me to Earth and to life are small. Wifeless, childless, relationless, what have I to look forward to? I freely place at your disposal the sum I have already named, and at the same time pledge myself to make your—shall I say OUR—journey a success."

"I thank you, friends, for your kindness, and your proffered assistance, and accept the offer of your company with unqualified pleasure. It is now November. All our preparations must be made during the next six months, that is by the end of April. We must leave Earth no later than that date. I also suggest that all our preparations are made as secretly as possible. Let the carriage be made in sections and parts; let all be brought here, bit by bit. My big barn will suit us for a workshop. Idle curiosity must not be excited. And, as a personal favour, I request that no hint of this journey be given to any mortal man."

Doctor Hermann then filled up his glass, all present following his example, and together we toasted each other, and drank in wild if silent enthusiasm to the success of our awful voyage through space.

"At last, Graham, all is in readiness for our departure. I think it was wise, however, that before finally leaving Earth we tested the capabilities of our carriage." (This trial trip nearly cost the Doctor his secret. A party of farm-labourers stoutly swore that they had seen a big house floating over Whernside, as they came home in the dusk; but they were only laughed at by their neighbours, and accused of being in liquor.) "We now feel a greater amount of satisfaction and confidence in our undertaking, and the several little details we had overlooked will be decided improvements."

"Then you are prepared to start on Saturday, Doctor?"

"Well, if Temple can manage it, yes. It rests with him now, and we must not be too hard or exacting on our generous friend and patron."

"Ah! Sandy, a telegram from Temple, I suppose," says the Doctor, tearing open the orange-coloured envelope, and hastily reading the brief message.

"Yes, Graham, all is well. Temple wires me that he will be here on Saturday to lunch. That means he is ready. We shall start at midnight."

The remaining days of our stay on Earth were spent by Graham in overhauling the various machinery and apparatus he had taken such pains in making and fitting, and by the Doctor in anxious consultation of several leading works on astronomy and mathematics, and in careful revision of every little detail of his gigantic scheme.

At last the eventful morning came, the first day of May, 1875. Glorious indeed was the weather on that memorable day, when, for the first time in the history of mankind, five living creatures were about to leave this planet on a journey to a far-distant orb.

Now behold this dauntless little party, as they stand in the Doctor's garden, watching their last earthly sunset. The white-haired Doctor is the central figure of the group.

As the sun sinks solemnly behind the Pennine peaks, lingering a few moments on the gloomy crowns of Whernside, the Doctor points to the clear southern sky, and says: "Well, friends, our stay on Earth is now very short. In little over four hours' time we must be gone. Yonder is our destination; the star that sheds such brilliant lustre—brightest, to us, of all heavenly orbs to-night—is our bourne. You see it, Temple? From this night, for two years and a-half, it is to be our only guiding light, ever increasing in size and mysterious splendour."

As the evening gloom crept up the valleys, the scene became more and more solemn and impressive, and a strange sense of awe seemed to come over even the bravest heart amongst us. We felt too grave to converse, and the Doctor's remarks were received in silence. At last the oppressive silence was broken by the Doctor exclaiming: "We had better now go in and dine, after which we must see about getting away. Have you finished, Sandy?"

"Yes, Doctor; everything is neat and tidy."

"Well, after dinner, we shall be round to inspect your arrangements for our comfort."

Dinner passed over in comparative silence.

Each one of the diners now fully realised the solemnity of his position, and none seemed to have any desire to make their thoughts known to their companions.

As soon as the meal was over, the ceremony of christening the carriage was performed by Sandy cracking a bottle of wine against the side, and as the ruddy liquid streamed to the ground, the Doctor pronounced the few words that gave to the machine its name of Sirius.

"Now, my friends, the all-eventful moment has come," he continued, leading the way to a rope-ladder which was hanging down the dark side of the Sirius, from the doorway high overhead. "Let us bid adieu to the Earth that bore and fostered us; it may be that our feet touch its surface for the last time."

The night was gloriously fine; not a cloud to hide the spangled sky. Sandy and his dog were already inside the Sirius; and the light-hearted Scot could be heard singing snatches of North-country ballads as he hurried to and fro. Sandy was, evidently, little troubled at the thoughts of Earth. This confidence was inspired by the calm courage of his master.

Graham mounted next, and was soon busy with the machinery, oiling and wiping with greatest care the shining rods and wheels and cranks, which he loved almost as deeply as a father loves his children.

John Temple then ascended, a little paler perhaps than usual, but calm and self-possessed as was his wont.

Doctor Hermann, after carefully walking round the huge machine to see that all was clear, gave one last look towards the old house, and then to the hills he knew and loved so well, before mounting the swaying ladder, which was pulled up after him by Sandy.

All now were waiting for the final signal, which was to fall from the Doctor's lips. He stood calmly and heroically with the little lever grasped in his right hand, his watch held in his left. One minute to midnight! Slowly the minute finger crept round the tiny dial, and the last few seconds of our stay on earth were slipping away.

"Once more, my friends, I ask you if you still adhere to your intention of accompanying me. There is yet time to draw back."

"We are ready and willing, and most anxious to proceed," was the answer from all.

"Then our voyage begins at last," said the Doctor, pressing back the shining lever. "May health and good fortune attend us on our journey, and success crown its termination."

As the Doctor spoke, the huge machine mounted upwards from its staging, lightly and buoyantly as a bird, into the midnight sky. All were exceedingly surprised at the extreme steadiness of the carriage, for it floated upwards and onwards without any disagreeable motion whatever. In fact, it was difficult to believe that the carriage was moving at all.

As soon as we got fairly under way the Doctor suggested that we should go out on the balcony and take a last look at many old familiar landmarks, and bid a long farewell to Yorkshire. We were travelling very slowly, about sixty miles per hour, and nearly four miles above the Earth. We soon crossed the fair vale of York, slumbering peacefully in the gloom, the lights of towns and railways being distinctly visible far below us. We passed over grimy Sheffield, with its gleaming furnaces belching fire and smoke into the night—its glowing coke-ovens looking like small volcanoes.

"I intend to travel comparatively slowly from the immediate neighbourhood of Earth," remarked the Doctor, "so that we may enjoy the wonderful sight of that planet's physical features as viewed from space. Ere morning dawns we shall be sufficiently distant to get a bird's-eye view of the greater part of Europe; by afternoon, if all goes well, our vision will be extended to the entire Eastern hemisphere."

The Sirius was now heading rapidly away from Earth; under Graham's superintendence, the motors were hourly increasing their speed. Like a sheet of molten silver, the German Ocean shimmered in the moonlight.

It was bitterly cold, and the entire party of travellers were soon glad to return to the warm interior of the Sirius, where Sandy had made everything ready for our comfort. It was now agreed that each should take his turn at keeping watch and guard generally for two hours, whilst the others slept.

Graham undertook the first two hours of this duty; and the Doctor, too excited to sleep, remained up with him discussing the novelty of their position. As for Sandy, he appeared able to sleep under any circumstances; and Temple was too methodical in his habits to remain up after the first sensations of departure had worn away.

"It seems like a dream to me, Graham, that we are really off at last," began the Doctor. "I have looked forward to this time for many long and weary years."

"Ah, Doctor, I cannot describe how I feel to-night. I am more than gratified to see one who has done so much for me, reaping the harvest he has sown so patiently."

The heavens were now clouded, and rain began to fall heavily, which necessitated closing the port-holes and door, and setting the air-condensers to work. It was the Doctor's intention to travel as long as possible with these open, so that we could obtain enough air from the atmosphere as long as it continued sufficiently dense for our requirements, and thus save the condensing apparatus as much wear and tear as possible.

We soon passed through the rain clouds, and then the view from above them was entrancingly grand. Far as the eye could reach, below and round us, stretched one vast silvery expanse of cloud, lit up with brilliant moonbeams, and so solid in appearance that we felt a strange yearning desire to descend and wander about the fleecy wastes.

Dawn was now fast spreading over the heavens. All through that night of excitement the Doctor and Graham watched together, but Sandy and Temple were up with the first streak of light. The Earth was still enshrouded in shadow.

But our speed had now to be increased, and by the time the Eastern hemisphere was bathed in sunshine we were travelling a thousand miles per hour, shooting upwards to the zenith, but drifting meantime nearly south, towards the equator. Hour after hour increased the glorious aspect of the Earth below, which had the appearance of a shallow basin, the horizon all round us seeming almost level with the Sirius. The Earth's concave, instead of convex appearance, was a puzzle to all but the Doctor, who lucidly explained the phenomenon to us.

By mid-day our instruments declared our height above the Earth to be close upon eight thousand miles! Stupendous as this altitude may seem, none of our party experienced the slightest degree of discomfort, so long as the condensers were kept at work; but a few moments' pause in their movement produced alarming symptoms, especially in Graham, whose bulky frame (he stood six feet eight, and was well made in proportion, a giant among men) seemed to require a larger amount of air than any of the rest of us. As we rapidly shot upwards, at a speed fifteen times greater than the fastest express train, the Earth was constantly changing in appearance.

All small objects were entirely lost to view; only the continents, largest islands, oceans, and seas being visible. The land and sea changed colour rapidly, until the former merged from dark brown to nearly black, and the water from deepest blue to yellow of such dazzling brightness as to be most trying to the eyes. We could distinctly see the noble range of snow-capped Himalayas, glittering beautifully in a dark setting, but the Cape of Good Hope was lost in a dense bank of cloud. As nearly as we could determine, we were now above the Persian Gulf; the entire coast-line of the Eastern hemisphere could be followed at a glance. Due north and south the polar regions glowed in dazzling whiteness, like two brilliant crescents on the horizon. The season of the year was too early to make satisfactory observations of the northern polar regions; for even had land extended to that pole, we should have been unable to detect it, as it would, of course, have been still lying deep in snow. The south polar region was much more favourable to our examination, and, beyond the border of eternal ice and snow, a dark mass could be detected in the district of the pole itself, which is probably land, but at the immense distance from which we viewed it, it was impossible quite satisfactorily to determine. Although we were such a vast distance from the Earth, she seemed to be quite close, though on a much-reduced scale, and no words can describe the awful grandeur of her appearance. Towards evening we had the novel experience of seeing an appalling thunderstorm many thousands of miles below us, over the wide expanse of the Indian Ocean.

We had now for hours been depending upon the air from our condensers. In fact we did not find breathable atmosphere for more than five hundred miles above the surface of the Earth. As the Doctor had predicted, the ether in these remote regions was quite dense enough to be transformed into air suited to the requirements of man. The Doctor's delight at all these wonderful scenes was unbounded. His enthusiasm was almost painful in its intensity. "Glorious! Glorious!" was his oft-repeated exclamation, as he made rapid notes of the ever-changing phenomena around us. He was too excited to eat; too full of his many experiments to rest; too eager to gather this unparalleled scientific harvest, to sleep! Gradually the sun seemed to sink into the waste of waters behind the western rim of Earth, throwing a lurid glare across the sea, which now looked like liquid gold, and then turned to deepest purple as the last rays shot upwards into immeasurable space.

Faster and faster we sped; the motors at last working to their utmost limits, the dial registering our speed at precisely fifteen hundred miles per hour. None of us yet experienced the slightest inconvenience, either from the immense altitude we had reached, or the terrible velocity with which we were travelling upwards. By midnight, the Doctor calculated our distance from the Earth to be 25,874 miles. Addressing Temple and Graham, he said:

"I think, my friends, that we ought to congratulate ourselves on the exceedingly promising state of our enterprise. In the first place, our carriage is progressing as favourably as we could wish; everything is in the smoothest working order; our air is of the purest; we have food in abundance; water in plenty; light and warmth, as much as we desire. Twenty-four hours ago we were on the Yorkshire fells; we are now well on our way to that New World we are all so eagerly looking forward to reach. When we left Earth, the planet Mars was glimmering low over the southern horizon; it is now in our zenith. We are fast approaching that region where all earthly influence will be past, and where the power of her gravitation will cease. We inaugurate our voyage with every prospect of success."

"I candidly confess, Doctor, that all my unpleasant feelings of danger have passed away. I have every confidence in the good Sirius and her talented inventor," remarked Temple.

"The same here, Mr. Temple," said Graham; "I feel perfectly convinced that—accidents barred, of course—we shall reach our destination in triumph."

As might naturally be expected in the clear rarefied atmosphere through which we were travelling, the various heavenly bodies shone much more brilliantly than ever they appear from Earth; and the vast, unfathomable vault of space was intensified in colour—very different from the blue of an earthly night-sky, and entirely free from cloud. The moon was perceptibly larger than she appears when viewed from Earth; but the other orbs only differed in the intensity and brilliancy of their light.

"Mr. Graham! Doctor! Doctor! the engine is going wrong!" Sandy was heard shouting.

"Be calm, Sandy," said the Doctor, as he and his two friends hurriedly descended into the engine-room. It was manifest that something had gone wrong with the machinery, and the anxiety of all was plainly visible as the Doctor and Graham hastened to make an examination.

"Thank heaven, the motors are safe," said Graham.

"It is only the pin out of the rod of one of the condensing pistons," calmly remarked the Doctor; and Graham soon put all to rights again.

Some time elapsed before the excitable Sandy could be pacified. He fully expected we were going to be dashed to pieces on the distant Earth. The Doctor took this opportunity of pointing out to us how necessary it was to keep a constant watch on our apparatus; for the least mishap might speedily lead to a calamity so appalling as to send a thrill of horror to the stoutest heart amongst us at the mere thought of it.

Long before morning dawned over Earth, on the second day of our voyage through space, we had reached such an enormous altitude, that even the outlines of the continents could not be traced with any degree of clearness. The large masses of land were sharply defined from the oceans, but all trace of peninsulas, isthmuses, and islands was lost. The Polar crescents of gleaming snow stood clearly out in bold relief, but the waters of the Earth were becoming very grey in appearance.

By 9 a.m. on the 3rd of May, we were close upon forty thousand miles above the Earth. Our life in the Sirius was very methodical, and a brief description of one day's routine will be sufficient for the purposes of this narrative.

Every two hours of night the watch was relieved, the person left in charge being responsible for the safe working of the various apparatus. At 7 a.m. Sandy prepared breakfast; at 1 p.m. we had dinner; at 5 p.m., tea; at 9 p.m., supper. The intervals between meals were passed by the Doctor almost exclusively in scientific observations, writing his journals, and carefully inspecting the machinery and instruments. To Graham was allotted the task of keeping all in order, and compiling a record of the distance travelled each day. Temple assisted the Doctor in many of his labours. He was likewise busy upon a work on finance—a great scheme for liquidating the national debts of Europe, which had been a favourite hobby of his for years. He also helped to write much of the present journal. Sandy's time was fully taken up in various domestic arrangements, and in looking after his dog. We usually went to bed at 11 p.m., but if anything exceptional occurred we stayed up later, and sometimes we were too excited to go to rest at all. The Doctor insisted on each one of the party taking a certain amount of exercise daily, and also swallowing a small dose of a drug of his own discovery.

For the first week our voyage was somewhat uneventful. Each day we continued to dash with stupendous speed towards the zenith. The earth, now, was greatly and rapidly changing in appearance. Our nights were remarkably short, and the period of sunlight became longer and longer in duration. We were soon to pass beyond the influence of the Earth's shadow, and to enter a region of perpetual day.

On the tenth day of our departure from Earth, when we were quite 360,000 miles above its surface, the moon completed her sideral revolution, and we saw the outer surface of the satellite for the first time in the history of mankind.

Unfortunately, we were too far away to make a very minute examination, but the scene vividly depicted through the Doctor's largest telescope was one never likely to be forgotten. We were gazing upon a new world; the eyes of mortal man had never rested on that portion of the moon's surface now before us; and, oh, how different did it appear from that pale orb we are all of us so accustomed to see lighting the darkness of Earth! Perhaps it is well that her gleaming yellow surface remains unchanged, in aspect, to all mortal eyes. Her surface, to the dwellers upon Earth, has become a symbol of peace, eloquent of deathly calm.

Our nights now became shorter and shorter—with great rapidity, until, at the end of the third week of our departure from Earth, when we had accomplished a distance of 800,000 miles, we reached those remote regions of space where the mighty shadow, cast by our planet, tapers down to a point, and the sun in all his glory reigns eternally supreme.

Our sensations were almost beyond description when the Sirius was at last fairly launched into the vast, boundless void of silent space. So long as we felt the influence of Earth, and journeyed on our way under the shelter of her mighty shadow, the bonds that held us to our mother world were still unbroken.

Then, things at least seemed earthly. Now, every Earth-tie was severed; surrounded by a solemn, limitless sea of space, unconceivable, unfathomable, filled with brilliant and eternal light, such as no man had beheld before, every one of us was filled with awe; and even the ever-cool and dauntless Doctor himself was well-nigh overwhelmed with the majestic splendour of the scene around us. We felt as if we had now ceased to be human; that we no longer belonged to Earth, but were outcasts, with no home or bond of human fellowship away from our floating carriage; doomed to live for ever, and to spend eternity in crossing this radiant ether sea! The silence was profound. The calmest stillness of Earth is as the tempest-roar in comparison with the awe-inspiring quietness of Here! The very beating of our pulses rang clearly out on space; the ticking of our watches became even painful in its loud intensity. Our hearts and our courage began to fail us. Only the Doctor, with his nerves of steel, refrained from uttering words of regret for thus rashly leaving Earth for the sake of prying into the very laboratory of the Universe! Supernatural influences seemed to surround us. We started as men; we seemed to be fast evolving into new beings, governed by no human impulses—controlled by no human forces. Still the Sirius sped on. Upwards the good air-ship flashed with terrible velocity, bearing us whither—ah, whither? When we became more familiar with the vastness around us, the feelings of dread passed gradually away.

The view from the windows was impressively grand. The sun shone with a brilliancy unknown on Earth, even in the tropics, but the heat was by no means oppressive. Far as the eye could reach, all was brilliant yellow light, endless, profound!

We now derived the greatest benefit from the spectacles, prepared on the same principle as the helioscope, which Doctor Hermann had provided for our use, the brilliancy of the light being most painful and trying to the eyes. Time, now, was one endless day of brightest sunshine, so that our only means of judging the hours of day, and what we still called night for the sake of convenience, was by the aid of our chronometers.

Soon after we reached these remote regions of eternal light, we began to experience considerable difficulty in breathing. At times this became so bad, that all of us lapsed into a state of semi-stupor. This caused us the gravest anxiety and alarm, and as we sped onwards the trouble increased. Clearly something was going wrong. The terrible thought that air was absolutely about to fail us, in spite of all the Doctor's careful experiments and calculations, filled us with thoughts too horrible to express. The condensers worked admirably, but driven at their utmost capacity, they still failed to furnish sufficient breathable atmosphere. Singularly enough, poor Rover felt this diminishing supply of air far more than his human companions, and for hours scarcely moved or breathed. The Doctor was puzzled, Graham was perplexed, Temple and Sandy very much depressed—the latter especially so. After many careful experiments and a thorough examination of the Sirius, we at last found the cause in a loosened window. The remedying of this necessitated one of us going out on to the balcony and climbing the corniced sides.

Graham volunteered the hazardous duty.

The Doctor, with his usual forethought, and showing how well he had planned-out his gigantic scheme to the very smallest detail, and how carefully he had provided for all the contingencies human intelligence could foresee, had brought with him a modified diver's helmet, with the air-tubes attached, and a small cock-tap was fastened in the side of the Sirius, through which air-pipes could be passed. This apparatus we adjusted on Graham's head, and round his body hung a coil of fine manilla rope. Our speed was now considerably reduced. While the Doctor assisted him to mount the ladder which led to the door, and opened and closed it as he went through on to the balcony, Temple and Sandy worked the pumps which supplied him with air. This door had to be closed very quickly, to prevent our own air escaping. We eventually heard him at work on the defective window, and the great improvement in the air of our chambers was sufficient evidence that he had succeeded in his task. Still, he did not return; for quite ten minutes we were in the greatest suspense as to his movements. The air-pipes had been drawn out nearly to their fullest extent, which was a singular circumstance, and one that seemed to bode no good, as half their length was amply sufficient for Graham's needs. Our concern rapidly grew into absolute alarm for the safety of our companion, until at last we had the signal that he was waiting to be admitted. It was a welcome relief to us all, and Sandy could not refrain from uttering cheer after cheer of welcome, forgetting his work of pumping until sternly called to his duty by the Doctor. As soon as the door was opened, poor Graham fell into the Doctor's arms, and for several hours he lay unconscious, in spite of all our remedies and careful treatment. Something had happened, and for an explanation of the mystery we had to wait until our friend regained consciousness, and was able to relate his thrilling story. This he must tell in his own words.

"Notwithstanding the still high rate of speed at which we were travelling, I experienced no inconvenience upon getting to the balcony," began Graham, drinking off a small glass of strong brandy which Temple insisted on his taking, "nor did I have any trouble in climbing up the ring ladder to the defective window. The damage was trifling in itself, and easily repaired; but I noticed, as I went up, what looked to be a long crack in the side of the Sirius, and determined to lower myself down and examine it. I fastened the rope to one of the rings, and lowered a part of it sufficiently long to reach the supposed crack: the end of the rope hung loosely down into space from the ring above. I cautiously began to descend, hand under hand, down the smooth, gleaming side of the Sirius. The distance seemed longer than I had calculated, and I could not see very well out of the glasses, for my breath dimmed them. I went cautiously lower and lower, when to my utter horror the bight of the rope gave way, and I slipped down many yards, to find myself hanging by the hands alone in space, below the Sirius.

"For one brief, awful moment every drop of blood in my body seemed frozen, when I realised the fact that I was swinging by the hands above the unfathomable gulf of space! Thanks to a nerve which has never yet failed me, my presence of mind did not forsake me. I tried to forget what was below, and to concentrate all my thoughts on what was above. Above was safety; below, the most horrible death a human being could suffer. I shudder now to think of it. I knew it was no use to call for assistance, you had it not in your power to relieve me. Not one of you could have lived out there without a proper supply of air. My only chance rested on trying to get back again—a wild and almost hopeless fight for life. The ring which held the rope had broken loose, and was hanging at the end. That saved me. It prevented the rope slipping from my grasp as I fell; and by pulling myself up a little way, I got my feet in the ring, and relieved the terrible strain upon my arms. Big beads of perspiration streamed down my forehead, and the stifling atmosphere in the helmet added to my woes, as I realised all the horrors of my awful position. Then, all the time, I was tormented with the possibility of the air-pipes breaking, and then—ah, then, to meet eternity, and fall downwards—WHERE?"

"Graham, your experiences must have been unutterably terrible," remarked Temple.

"The mental torture of such a terrible situation must have seemed beyond human endurance. Try a little more brandy, and finish your story later on, when you feel stronger," said the Doctor.

"No, thanks, Doctor; I begin to feel myself again, and would like to relate all while the facts are still fresh in my memory."

"With a desperation," continued Graham, "only born of a wild desire for life, I commenced my struggle upwards. Swinging from side to side, and twisting round and round above that gleaming yellow gulf, whose depths no mortal could sound, I slowly climbed, hand over hand, for a little way, and then stopped to rest. I soon, alas! realised the fact that going down was much easier than coming up, and every moment I felt my arms losing strength. Oh! how horribly smooth and remorseless did the shining sides of the Sirius seem! Not a projection of any kind to assist me. Several times I was almost giving up in despair, and ending my frightful misery by dropping quietly into the yawning void below, but the natural love for life implanted in every animate creature held me back, whilst hope whispered encouragement in my ears. I could hear your voices; the sound of my pulse as it throbbed on in its agony was startlingly distinct. I heard Sandy call out the hour—I had only been five minutes in my dreadful position, after all, yet it seemed ages and ages. Suddenly an idea struck me, and that was if I could manage to hold on by one hand, with the other I might pass the end of the rope under my foot and form a loop.

"This I succeeded in doing, and was thus able to rest my arms a little, at intervals, as I slowly struggled upwards. How heavy the helmet seemed to be getting! I felt slowly drifting into unconsciousness, and death. In what seemed to me an eternity, I at last reached the other end of the rope, which I had left hanging loose. By a great effort I got this end through the ring and secured it, thus making a loop in which I was able to stand for a few moments and rest. I cannot tell you how deliciously sweet those few seconds were; they seemed like a respite from the very jaws of death. I actually examined the supposed crack which had been the cause of all my misfortune, and found that it was not a flaw, but a mere scratch in the outer coating of the Sirius. After this all was comparatively easy. I soon got on to the balcony, untied the rope, and gave the signal at the door. Then all was blank; my senses left me. I suppose the mental strain had been too much, and that the overstrung nerves had collapsed at last. I remembered nothing more until I found myself under your care, and was surprised to learn that for three hours I had lain unconscious."

"We all congratulate you on your wonderful escape, Graham," said Temple. "A bottle of our best port shall be uncorked. It will put new life into you, man."

"And, Graham," remarked the Doctor, "you will perceive that your perilous undertaking has brought about good results. The air we are now breathing is all right again. We have lost but little time, for the moment we knew you were safe the motors were started again at full pressure."

"The leakage," rejoined Graham, addressing the Doctor, "was absurdly trivial, yet it makes one shudder to think what would be the case did our air escape in any larger quantity."

"It only shows how scrupulously careful we must be, and neglect no precautions for our safety," said Temple.

"The perils of our position must keep each one of us alert. Unforeseen terrors may surround us; at any moment we may encounter unknown perils; we may be rushing into the midst of forces that will require all our fortitude to contend against them. We are in the midst of danger, and have to grapple with any difficulty that may present itself, without having the benefit of any human experience to guide us. But we shall pull through; we shall pull through, my friends; and think of our glorious reward!" remarked Doctor Hermann, working himself up into an enthusiastic state of excitement as he spoke.

"What are the results of your observations and calculations to-day, Doctor?" said Graham. "I reckon we are now one million two hundred and fifty thousand miles from home!"

"You were asking me, Graham, about the results I arrived at to-day," continued the Doctor. "Briefly, they may be summarised thus. I find that we are now entirely beyond the attractive forces of the planet, Earth. We are now, as it were, in a neutral position; not yet close enough to Mars to come within the influence of his attraction."

Four hours after the Doctor had thus spoken, that is to say at twenty minutes past two in the afternoon, the transit of Earth commenced. He had timed the occurrence to a second. Slowly the sphere of Earth crept into view, and crossed gradually towards the centre of the sun, and finally passed beyond the disc into space again. No words of human tongue can adequately express the sensations we experienced as we watched the planet Earth, now nothing but a small, dark ball in appearance, travel across the fiery background of the sun. To know that that mere speck was a universe peopled with millions of living creatures—to know that that tiny black disc, so far out yonder, was in reality a vast and mighty world, floating in space, yet so small in comparison to other orbs around us, impressed upon our minds the grand sublimity of Nature's works.

For many weeks after the events recorded in this chapter, the Sirius sped on without a single notable occurrence to relieve the monotony of the journey. Our first Christmas Day was observed with all customary honours, Sandy providing us with a royal feast; and the evening was given up to conviviality and amusement. The Doctor and Temple played chess; Sandy, with his short pipe and unlimited whiskey, now and then sang us a North-country ballad; Rover lay quietly at his master's feet; Graham smoked huge Cabanas, told stories, fired off jokes, and sang many a Yorkshire ditty. All of us felt the magic spell of Christmas-tide, and the observance of the festal day filled our hearts with renewed hope, and served to increase and strengthen the bond of brotherly unity in our little party.

We were now 8,820,000 miles from Earth, or, reducing this vast number to more comprehensive language, we had accomplished slightly more than a quarter of our journey. We still continued to find ether sufficiently dense to be converted into a breathable atmosphere, and into water—everything promised well for the ultimate success of our daring enterprise. Alas! for all human hopes and human anticipations; we little dreamed of what the future was about to bring!

Day after day, week after week, and month after month sped the Sirius on its journey, like a meteor across the gulf of space. We had now been eighteen months away from Earth, and our distance from that planet we computed to be quite nineteen millions of miles. The Earth was remarkably small in appearance, and the moon could only be detected through a glass. On the other hand, Mars had risen in elevation, and sensibly increased in brilliancy and apparent size. Other heavenly bodies had also changed considerably in their aspect. Some had got much larger, others smaller, many had disappeared entirely from our vision, whilst several new orbs had been discovered. The Doctor was able to make many observations of the little-known asteroids which travel round the sun between the orbits of Mars and Jupiter. Scores of new ones were seen.

For a long time Doctor Hermann had been worried by the course which the Sirius was taking. In spite of the fact that we were apparently steadily travelling onwards across the vast belt of space between Earth and Mars, certain of his calculations appeared to demonstrate that we were being drawn rapidly towards the sun! The quantity of water we condensed from the atmosphere now became very small, and eventually failed altogether, so that we had to depend upon our scanty store and the lozenges.

After an unusually long and tedious day, the Doctor gloomily threw aside his papers and his instruments, exclaiming to Graham in almost pathetic tones, "It is as I have long expected; the sun is too much for us!"

"But, Doctor, you may have erred in your calculations. Do you really think it wise to take such a pessimistic view of our situation?" answered Graham, with a hopefulness that he was far from actually feeling.

"If Temple can spare us a moment, ask him to join us, and I will endeavour to explain our actual position, and the prospects we have before us."

"A horrible one! A most horrible one!" the Doctor muttered under his breath, as Graham walked thoughtfully away.

Temple and Graham joined the Doctor almost immediately.

"Now, Doctor, what have you got to tell us this time? What new discovery have you made? Nothing unpleasant, I sincerely hope," said Temple, in his usual cheery way.

"My dear friends," began the Doctor, "I am afraid I have bad news to communicate—very bad news. But let us look the situation squarely in the face, and discuss it calmly and philosophically, as becomes intelligent men."

"Many weeks ago," continued the Doctor, "I explained to Graham and yourself that our centre of gravity had changed from the Earth to the sun; instead of earth glimmering at our feet, nineteen millions of miles below us, we have the fiery sun, as both of you cannot have failed to observe. This I must hasten to explain, is cause for no surprise; it is just what I expected would be the case until we came within the attractive forces of Mars. But my instruments have demonstrated that our motors are now absolutely of no use. They are working just as usual, but our speed increases rather than diminishes, and from this I infer we are influenced by some vast attractive force. That centre of attraction to which we seem hurrying can only be the sun! No further words of mine are needed to render more clear the horrible doom which awaits us."

As he finished speaking, the Doctor rested his head on his hand, the usual attitude he assumed when engaged in deep thought.

"But, Doctor, before we take all this for granted, at least let us satisfy ourselves more completely that things are really so bad," said Graham.

"No use, Graham, no use; I have studied these matters too long and too carefully needlessly to alarm you," answered the Doctor.

"Well, Doctor," said Graham, "at least allow me to stop our motors. Then what you say cannot possibly be refuted."

"I think Graham is right, Doctor," remarked Temple. "It seems to me a very practical suggestion."

"You may do so if you like, but it is trouble thrown away," the Doctor answered.

Graham was already hastening from the laboratory down the steps to the engine-room, followed by his two friends, and a moment afterwards the machinery ceased to work; the bright cranks and wheels and rods were still; the motors ceased to revolve. At last this beautiful monument of engineering skill, which had kept incessantly at work for upwards of eighteen months, was stopped, and breathlessly the three men awaited the result.

Doctor Hermann, cool and collected even in such awful moments, walked slowly back to the laboratory to consult his instruments. Graham and Temple followed, too excited to speak.

"Well, Doctor," said Temple at last, after he had patiently waited his investigation, "what are your conclusions?"

With marvellous coolness, as though answering the merest commonplace remark, Doctor Hermann replied: "It is as I said before; the Sirius is falling with ever-increasing speed into the sun! We are lost!

"Our doom, even if our speed goes on increasing, cannot overtake us for several years," continued the Doctor, "but I doubt if our supplies could hold out for such a period."

"Doctor," broke in Temple excitedly, "that is poor comfort; you ask us too much endurance. I, for one, will not, cannot, go on in such misery, only to be overwhelmed at last. Two alternatives are left to us. We can either go on in a lingering agony of suspense, and meet our doom by starvation, or by fire; or, we can end our woes swiftly and effectually with these"—and as he spoke he pointed to the four nickel-plated revolvers hanging loaded against the wall. "We can but die like men!"

"I must confess, if all hope is really gone, that I incline to Mr. Temple's view of the situation, and would prefer a sharp and practically painless death to, it may be, years of horrible suspense, crowned with the ten thousand times more awful fate of being hurled into yonder furnace at last," said Graham.

"Temple, and you, too, Graham," answered the Doctor, "you surprise me by such a shallow mode of reasoning. Listen to me. Both of you are free agents to act as you may think fit; but before you rashly take your lives, at least wait a little longer. We are in the midst of strange surroundings, and still stranger possibilities. There is nothing to warrant you in taking such extreme measures."

"My sentiments, Doctor, must, I suppose, be attributed to my weakness," answered Temple.

"You may taunt me as you will," said Graham, "but I believe there are rare occasions in life when self-murder can be no crime—nay, is even justified."

"Then all I can say is that your ethics are not mine, that your theology is not half the comfort or support to you in your extremity that my philosophy is to me in mine," remarked the Doctor.

"Once more," said the Doctor, "let me bid you wait. Let the motors be started again, Graham, at full pressure. Some unforeseen occurrence may yet work our salvation."

As time went on, Graham and Temple became more resigned to their fate; and, in answer to the Doctor's urgent entreaties, gave him their promise to think no more of suicide, at least until matters became more desperate. The Doctor never abandoned hope. Calmly he bore up under all difficulties, plodding along with his instruments and his calculations; writing up his journals, and making voluminous notes, though every word he penned was probably never destined to be read by any other mortal but himself.

During the twentieth month of our absence from Earth, vast clouds of meteorolites passed within a few miles of us; and at one time the whole range of our vision was filled with these brilliant objects, just like a snowstorm of sparkling fire. Many small ones struck the Sirius, others exploded close by with sharp reports. We were too much alarmed and too disconsolate thoroughly to enjoy the glorious sight, the effects being beautiful in the extreme, and we were thankful when we passed beyond this shower of fire.

Onwards, onwards and onwards we sped, falling with awful velocity through space. So fast did we travel that our indicators failed to record the rate of speed, but still the sun did not appear any closer.

This was our one assuring hope. The Doctor was assiduous in his observations, but could not arrive at any definite conclusion. A week before our second Christmas in the Sirius, after a careful scrutiny through his largest telescope, he joyfully announced that Mars was greatly increasing in apparent size, and that he had actually detected the presence of two satellites revolving round the planet! Here was welcome news, indeed! If this were true, then, after all, we had nothing to fear from the sun. After some further investigation we were thoroughly convinced of our safety. No words can tell our feelings of thankfulness. We felt as though we had been snatched from the very jaws of death.

"I can only explain our apparent fall towards the sun," said the Doctor, "by the extreme rarity of the ether around us. This was not sufficient to float us, nor to afford resistance to our motors: hence we fell into space, instead of being propelled through it. I made the very natural error of supposing that some attractive force was at work, other than that exerted by the planet Mars. Once more our prospect is unclouded. The worst part of the journey is over; we may expect at any time now to find our centre of gravity fixed on Mars, at last—then success may almost be counted upon as a certainty."

Our second Christmas in the Sirius was spent as happily as the first. The past year had been an exciting and eventful one for us; full of dangers, full of trials; and three of our party felt that we had overcome them, thanks in a great measure to Doctor Hermann's skill and indomitable courage.

Almost daily we found the ether around us becoming more dense, and the speed of the Sirius sensibly decreased. Our water supply once more became plentiful, the condensers now working admirably.

We kept New Year's Day as a great holiday—a red-letter day in our experience, each of us feeling that we ought to inaugurate such an eventful year in not only our own history, but that of mankind, in a manner suited to its vast importance. As the clocks on Earth were striking midnight on the 31st of December, 1876, and New Year's greetings were being exchanged in all parts of the world we had left, four human beings, millions of miles away in space, were doing likewise. Earth shone steadily, like a pale beautiful star, below us. During the first few moments of that glad New Year, we drank with mild and boisterous enthusiasm to the planet Mars, to the men on Earth, and to our own success.

Owing to the increased rate of speed at which we had been travelling, our distance from the Earth had increased much more than we had suspected. The Doctor computed our distance from Earth to be now 28,000,000 miles! If all went well, we should arrive at Mars in about six months' time. We all of us had long felt weary of our close confinement. Owing to the strict rules of hygiene that the Doctor enforced, not one of the party had suffered from disease. Still, it was a great joy to know that we should soon be released from the Sirius, and the wonders of a new world were a rich reward in store.

Mars, now, was a most beautiful object in the heavens. Long and often did we peer at it through our telescopes in wondering astonishment, as it shone in brilliant ruddy glory, still millions of miles away. The Doctor was enchanted with his discovery of the satellites of Mars.

By the end of January, 1877, we had crossed those regions of rarefied ether, which were little more than an absolute vacuum; and the Sirius was once again propelled by its motive forces alone.

We now thought it advisable slightly to check our engines, and our speed was reduced to about twelve hundred miles per hour. Another interesting phenomenon was the change in our centre of gravity, which was now the planet of Mars. This last great discovery set all our doubts at rest. Between five and six millions of miles had still to be traversed, many perils had still to be undergone, many difficulties remained to be overcome—but Mars, bright, glorious, ruddy Mars, was conquered at last!

For a month after the last events were chronicled the Sirius pursued its way steadily towards Mars, without a single exceptional incident. On the second of February, however, when we were about four and a quarter millions of miles from our destination, we were dreadfully alarmed by a series of majestic natural phenomena.

On the evening of the day just mentioned, or, rather, what would have been evening could we have distinguished night from day, the sun, for the first time since we left the shadow of Earth, began to shine less brightly. As the hours went by he became more and more indistinct, just as he appears through a fog on earth, and finally his fiery rays were hidden behind vast banks of cloud. The blazing light now became a depressing gloom, just as before a thunderstorm. Our dog evidently felt ill at ease, and whined and trembled as with great fear.

Rapidly the gloom increased. Darker and darker grew the fathomless void which we were crossing, until we were surrounded by one vast blackness, such as no dweller on Earth could ever conceive. The Sirius was lighted with incandescent lamps, but these only served to make the awful darkness more profound. This terror-inspiring gloom seemed to enter our very souls; we could not only see it, we could absolutely feel it. The Sun seemed as though he had finally burnt himself out, and disappeared for ever from the spangled firmament, leaving all within the focus of his once-glorious rays in unutterable chaotic blackness. It was as though we had penetrated into the very womb of the universe, where no light could ever be!

"I think this is absolutely the most dreadful of our many weird experiences," said Temple to the Doctor.

"It is sublimely grand," answered the Doctor, "and only shows how infinitely little man knows of the forces of Nature away from his own planet."

"Doctor, there is something wrong with our compasses. The needles are revolving with great velocity. I trust the presence of all this electricity round us will not injure any"—

Before Graham could finish, the whole firmament seemed lit up with a dazzling purple light, and a moment afterwards we were struck dumb with horror at the awful sound which followed it. For a moment the Sirius seemed about to fall to pieces; every bolt and plate in her vibrated, and we gave ourselves up for lost. The frightful explosion was like nothing heard on Earth: ten thousand thunder-claps in one would be but a feeble imitation of that terrible discharge, which was gone in a moment without a single echo to mark its departure!

Far in the distance we could hear mighty cracking sounds coming nearer and nearer, and then dying away in space. Clap after clap of this awful thunder shook the very vault of heaven in their awful intensity; and flash after flash of brilliant light lit up the vast void across which we were travelling. How the Sirius escaped utter annihilation amidst all this mighty display was a mystery to us all. It oscillated tremendously, as though at the mercy of conflicting currents, and reeled like a ship in a heavy gale. What appeared to be glowing meteors rushed by us with a deafening roar, or exploded with a terrible crash. Vast expanses of space were filled with brilliant light, sometimes like glowing mountains and cave-grottoes of fire. Vast sheets of blue and yellow flame rolled up with a crackling noise like huge scrolls of parchment, or curled and twisted into the most grotesque shapes. Purple, yellow, and blue tongues of flame shot across the darkness, sometimes silently as the sheet-lightning of Earth, but more often followed by loud and sharp reports.

Great quantities of fine magnetic dust accumulated on the balcony of the Sirius, and once a large globe of purple fire dropped on the roof, and bounded away again into space. As the electrical discharges gradually became less violent, the whole vault of space above us was lit up with one vast aurora, whose enchanting glories were utterly beyond description. Every colour of the rainbow, every combination of colour that man could conceive, was there, all blended into one gorgeous flare of tinted light. Temple, Graham, and Sandy, though no cowards, were at last compelled to turn their amazed and wonder-stricken faces from this appalling scene; but Doctor Hermann, with blanched cheeks, watched the wonderful phenomena, cool and intrepid among all the fiery strife, controlling his emotions with what must have been an almost superhuman effort of will.

Throughout this period of unparalleled darkness our air was very bad, and the condensers working at their utmost pressure could scarcely keep up a sufficient supply of breathable atmosphere. Most of our electrical apparatus was thrown out of order. We were able to generate little electricity during this wonderful phenomenon, and had it not been for the store of this force we always had by us, our engines would have been stopped. We failed absolutely to obtain water from the ether, so long as we were surrounded by these meteoric clouds.

The view of the heavens through our telescope was now exceedingly beautiful.

During the first week of March, a stupendous comet made its appearance between the Sirius and Earth, and such was its exceeding brilliancy that for days it was visible to the naked eye.

Another uneventful month passed away, the only occurrence of interest being the apparently rapidly increasing size of Mars. On the 7th of April our distance from Earth was 32,000,000 miles, which consequently left us about 2,000,000 more miles to travel. Even in the brilliant sunlight Mars was visible without the aid of a glass, and presented a singularly beautiful and ruddy aspect. We were, as yet, too far away to distinguish much of its physical features, but we saw enough to excite our curiosity and interest to the very utmost.

Every available moment of our waking hours was spent in discussing the physical conditions of Mars, and in making our plans for the time when we should land upon its surface. Daily we were more and more convinced of the similarity between the physical conditions of the Earth and Mars, the most important fact of all being the undoubted presence of an atmosphere of considerable density. The satellites of Mars were now becoming very bright and conspicuous.

The Sirius continued its rapid flight through space with uninterrupted speed. Our time was mostly spent in astronomical observation, and in discussing the beauties of the firmament as revealed by our telescopes. We never seemed to tire of witnessing the glories of the heavens.

An interesting fact which we could not fail to observe was the apparently much smaller size of the sun's disc, and a sensible decrease both in the amount of his light and the warmth of his rays.

Life in the Sirius went uniformly on. It seemed ages since we were on earth, or had communion with our fellow-men.