Project Gutenberg's Larry Dexter and the Stolen Boy, by Howard R. Garis

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most

other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of

the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at

www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have

to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook.

Title: Larry Dexter and the Stolen Boy

or A Young Reporter on the Lakes

Author: Howard R. Garis

Release Date: March 16, 2018 [EBook #56743]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK LARRY DEXTER AND THE STOLEN BOY ***

Produced by David Edwards, Susan Theresa Morin and the

Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

(This book was produced from images made available by the

HathiTrust Digital Library.)

See Transcriber’s Note at end of text.

LARRY DEXTER

AND THE

STOLEN BOY

OR

A YOUNG REPORTER ON

THE LAKES

BY

HOWARD R. GARIS

AUTHOR OF “LARRY DEXTER’S GREAT SEARCH,” “LARRY DEXTER, REPORTER,” “DICK HAMILTON’S FORTUNE,” “DICK HAMILTON’S CADET DAYS,” “DICK HAMILTON’S FOOTBALL TEAM,” ETC.

ILLUSTRATED

NEW YORK

GROSSET & DUNLAP

PUBLISHERS

BOOKS FOR BOYS

By Howard R. Garis

THE DICK HAMILTON SERIES

DICK HAMILTON’S FORTUNE

Or The Stirring Doings of a Millionaire’s Son.

DICK HAMILTON’S CADET DAYS

Or The Handicap of a Millionaire’s Son

DICK HAMILTON’S STEAM YACHT

Or A Young Millionaire and the Kidnappers

DICK HAMILTON’S FOOTBALL TEAM

Or A Young Millionaire on the Gridiron

(Other volumes in preparation)

12mo. Cloth. Illustrated.

Price, Per volume, 60 cents, postpaid.

THE YOUNG REPORTER SERIES

FROM OFFICE BOY TO REPORTER

Or The First Step In Journalism

LARRY DEXTER, THE YOUNG REPORTER

Or Strange Adventures in a Great City

LARRY DEXTER’S GREAT SEARCH

Or The Hunt for a Missing Millionaire

LARRY DEXTER AND THE BANK MYSTERY

Or A Young Reporter in Wall Street

LARRY DEXTER AND THE STOLEN BOY

Or A Young Reporter on the Lakes

GROSSET & DUNLAP

PUBLISHERS NEW YORK

Copyright, 1912, by

GROSSET & DUNLAP

Larry Dexter and the Stolen Boy

My Dear Boys:

Most unexpected things happen to newspaper reporters. That is one reason why, in spite of the hard work attached to the profession, so many bright young lads like it. It was that way with Larry Dexter. It was the unexpected that he was always looking for, and nearly always he found it.

In this, the fifth book of “The Young Reporter Series,” I have related for you something that happened when Larry unexpectedly went to a concert. Before he knew it he was involved in a mystery that had to do with a stolen boy.

How he promised the stricken mother to find her son for her, how he picked up slender clews and followed them, how, seemingly beaten andiv baffled, he still kept to the trail—all this I have set down for you in this book as well as I knew how.

I hope it is not presuming too much to say that I trust you will like this volume as well as you have my other books. Larry is a character to be proud of, and I have tried to do him justice.

Yours sincerely,

Howard R. Garis.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

|---|---|---|

| I. | A Frightened Singer | 1 |

| II. | Larry Scents a Mystery | 12 |

| III. | A Stolen Boy | 19 |

| IV. | Larry’s New Assignment | 27 |

| V. | Scooping the “Scorcher” | 36 |

| VI. | A Visit to Señor Parloti | 43 |

| VII. | Larry Seeks Clews | 52 |

| VIII. | A Threatening Letter | 58 |

| IX. | A Sudden Disappearance | 70 |

| X. | The Torn Note | 79 |

| XI. | Larry Meets a Farmer | 85 |

| XII. | The Lonely House | 92 |

| XIII. | The Raid | 100 |

| XIV. | What Happened | 107 |

| XV. | A New Clew | 116 |

| XVI. | Off for the West | 122 |

| XVII. | On the Lakes | 129 |

| XVIII. | The Deserted Room | 137 |

| XIX. | Cruising About | 146 |

| XX. | Cut Adrift | 156 |

| vi XXI. | In the Grip of the Storm | 162 |

| XXII. | Another Accident | 169 |

| XXIII. | “Motorboat Ahoy!” | 177 |

| XXIV. | The Chase | 182 |

| XXV. | A Happy Mother—Conclusion | 193 |

LARRY DEXTER AND THE

STOLEN BOY

“Hello, Larry, just the chap I want to see!” greeted Paul Rosberg, one of the oldest reporters on the New York Leader, as a tall, good-looking young fellow came into the city room one September afternoon. “I’ve been hoping you’d show up.”

“Why, what’s the matter?” asked Larry Dexter, the “star” man on the Leader, when it came to solving strange cases and mysteries. “Do you want the loan of five dollars, or has your typewriter gone out of commission?”

“Neither,” replied Paul Rosberg, with a smile, though he knew Larry would oblige him were it necessary. For Larry Dexter had a natural talent for machinery, and often adjusted the “balky” typewriters of his fellow reporters. Also, he would lend them cash when they were temporarily embarrassed, not to say broke. For Larry had made considerable money of late, especially in solving the big bank mystery, and2 he was always willing and ready to lend to his less fortunate brethren.

“Then, if it isn’t either one of those things, I can’t imagine what it is,” went on the young reporter, as he sat down at his desk. The city room was nearly vacant, all the other reporters having gone home. For the last edition of the Leader was off the presses, and work for the day was over, the sheet being an afternoon one.

“I want you to do me a favor,” went on Mr. Rosberg, who was considerably older than Larry, and, as he spoke the man began reaching in his various pockets as if searching for something. “You haven’t anything on for to-night, have you?”

“No, I’ve been out on a Sunday special story, and I’ve cleaned it up. It didn’t take me as long as I expected, so I thought I’d come back to the office to see if Mr. Emberg had anything else for me.”

“You’re too conscientious Larry; altogether too fussy,” spoke his companion. “But I’m tickled to pieces that you did come in. I was hoping you, or some of the other obliging lads would, for I’m stuck on a night assignment that I don’t want, and it comes at a bad time. There, cover that for me, will you?”

He handed Larry two slips of pasteboard, theater tickets, as was evident at first glance.

“Hum!” mused Larry as he looked at them. “Farewell appearance of Madame Androletti, eh?3 I wonder how many ‘farewell’ appearances she’s had? This must be about the forty-ninth. She’ll soon finish up at this rate. ‘Grand concert and musicale,’” he went on reading. “Musicale with a final ‘e’ no less. In the new Music Hall, to-night, too. I say, Mr. Rosberg, what does it mean, anyhow? Do you want me to go to this concert with you?”

“No, Larry, I want you to cover it for me. Report it, if you like that better. Say, look here, old man” (Larry was not an old man by any means, but the term was used as a friendly one), “this is my wedding anniversary to-night, and I promised my little lady that I’d come home early to a supper celebration she’s gotten up. Then, at the last minute, the editor wants me to cover this concert. Seems as though Madame Androletti has some pull with the paper, and wants a representative at her concert, though I don’t see why the morning paper reporters wouldn’t do as well.

“But, as you know, I’ve been doing theatricals and musicales for this sheet for some time, and they want me to cover this. Not that I need to do it personally, but they expect me to look after it. Now, I don’t want to go, and that’s why I’m asking you to cover it for me.”

“But look here!” cried Larry, lamely accepting the tickets which the other held out. “I don’t know anything about music. That is, not enough to report a concert. I like it, and all that, but I don’t know how to grind out that stuff about high4 notes, coloratura work, placement, ensemble, vocal range, and all that sort of thing, that I see in your accounts of musical doings every once in a while. I’d make a mess of it.”

“That’s all right, Larry,” spoke the musical critic. “I’ve thought of that. I’ll do all the fancy ‘word-slinging.’ I’ll write the story to-morrow morning. All I want you to do is to go there and bring me back a program. You can ask the leader of the orchestra if it was carried out. He’ll jot down the names of any extra numbers the madame may have sung as encores. Then it will be up to me. I know nearly all the concert pieces anyhow, and I can fix up an account.

“Just you keep your eyes open, size up the crowd, watch how the lady sings, get me a few notes about her bouquets and all that, and I’ll do the rest. It won’t be the first time I’ve written about a concert without being there.”

“But,” objected Larry, “I won’t know whether she’s singing good, bad or indifferent.”

“No trouble about that,” spoke the other. “Madame Androletti always sings well. I’ve heard her.”

“But won’t Mr. Emberg object?” asked Larry, naming the city editor.

“No, I’ve fixed it with him. I asked him if I couldn’t get some one to cover the concert for me, on account of my celebration to-night, and he said it was up to me. So I’ve drawn you. Pshaw, Larry, it’s easy! Anybody who can solve5 a million-dollar bank mystery the way you did, can surely cover a simple concert.”

“But it’s so different,” objected the young reporter.

“Not at all. It just needs common sense. Go ahead now, cover it for me,” and with this Mr. Rosberg hurried out of the room, leaving Larry standing there, holding the two concert tickets.

“Take some one with you—your best girl,” the older reporter called back, and he caught the elevator, and rapidly descended to the street.

“Well, I guess I’m in for it,” mused Larry, as he looked at the tickets in his hand. They were choice seats, he noted, and, had he been obliged to buy them, they would have cost five dollars. That was one advantage of being a reporter.

“Take my girl with me,” went on the young reporter. “Well, why not? I wonder if Molly Mason wouldn’t like to go?” and Larry’s thoughts went to the pretty department-store clerk, who had helped him solve the million-dollar bank mystery. “I’ll call her on the ’phone. She can’t have left the store yet,” he went on. A few minutes later he listened to her rapturous acceptance.

“Oh, Larry!” she exclaimed, “of course I’ll be delighted to go. I’ve just got a new dress, and, oh, it’s awfully nice of you to ask me, I’m sure.”

“I’m being nice to myself,” answered Larry. “All right; I’ll call for you about eight.”

And so that was how, a few hours afterward,6 Larry rolled up to the modest apartment house where Molly Mason lived, the young reporter arriving in a taxicab.

“Oh, what luxurious extravagance!” exclaimed Molly, as she sank down on the cushions. “Why did you do it?”

“Oh, as long as I’m going to report a swell concert I might as well do it in style,” replied Larry. “I hope you’ll like it.”

“Oh, I know I shall!” she exclaimed.

An usher showed them to their seats. The hall was beginning to fill, and Larry and his companion looked around curiously, not that Larry was not used to the members of “swell” society, for his duties had often taken him among them, and he had come to have rather a common regard for that class of persons.

But to Miss Mason it was a dream of delight, as, on her slender wages, she seldom got a chance to attend expensive amusements, for she had to help support her family. The audience was a rich as well as cultivated one, as Larry soon saw.

“There, I forgot to get programs!” he exclaimed, after he and Molly were comfortably seated. “I’ll go back and get a couple. I won’t be a minute.”

She nodded brightly, and resumed her gaze about the rapidly-filling theater. From the depths back of, and under the stage, could be heard the mysterious, and always thrilling, sounds of the orchestra tuning up.

7 As Larry picked up two programs from the table in the lobby he saw a tall, large man, conspicuous in a dress suit, with some sort of ribbon decoration pinned to the lapel of his coat, enter the rear of the auditorium. The man stood gazing down over the heads of the audience with sharp and piercing eyes, that seemed to take in every detail. He looked to be a foreigner, an Italian, most likely.

“Some count or marquis,” thought Larry as he looked at the man’s decoration, noting that it was a foreign one. “It’s queer how they like to tog themselves out in ribbons and such things.”

The young reporter was about to return to his seat with the programs when he noticed two young Italians in one of the rear rows of the hall. They had turned, and were gazing at the large man in the dress suit. Most of the men in the audience were similarly attired, but the two Italians in the rear, though well dressed, did not have on the clothes that fashion has decreed for such affairs.

It was, therefore, somewhat to Larry’s surprise, that he saw the evidently titled and cultured foreigner make an unmistakable signal to the two men. The big man raised his right hand to his right cheek, with the fingers and thumb spread out. He held it there a moment, and, taking it away, brought it back again, as though to indicate the numeral ten.

As Larry watched, he saw the taller of the two8 men hold up one finger. Apparently satisfied, the big man turned aside, and approached an usher.

“At what time does Madame Androletti make her appearance to-night?” he asked, with a foreign accent.

“At nine, first, and then at ten,” was the answer, and Larry was at once struck with the answer. The singer came on at ten, and ten was the numeral the big man had signaled to the others. What could it mean? Larry wondered.

“Very good,” answered the foreigner, as he turned aside, and went out into the lobby, with a hasty glance toward the two in the rear seats. Larry saw them both nod their heads.

“Well, I don’t know that it concerns me,” mused the young reporter, as he returned to his seat. “It looks rather odd, but I guess I’ve got so that I’m looking for mysteries in everything. I’ve got to get out of the habit.”

He looked at the program, after handing Molly one, and noted that the cause for the long wait between the two appearances of the singer was because of a heavy orchestral number coming in between her first and second selections. After that she was to sing several songs in succession.

“I’m going to watch when she comes on at ten,” said Larry to himself.

The concert soon began, with an overture, and Larry found himself enjoying it, even though he knew little about classical harmony. Molly was in raptures, for she had a natural taste for music9 that Larry lacked, and she had taken a number of piano lessons.

“It’s grand!” she whispered to him.

Madame Androletti came on for her first number, being loudly applauded. Larry made some notes, that he might give Mr. Rosberg an intelligent account of the affair, and then gave himself up to the rapture of the music.

The orchestral number followed, and then, as the hour of ten approached, Larry found himself wondering what would happen. The musicians tuned their instruments for what was to be one of the chief vocal numbers, and there was a hush of expectancy.

The curtains and draperies parted and Madame Androletti came on again, bowing with pleasure at the applause. Larry found himself watching her curiously. Then he turned and cast a hasty glance to where the two strange men had been seated. They had left the hall.

“That’s strange,” mused Larry, and then turned back, for the singer was beginning her song, her exquisite voice filling the big auditorium.

She had not sung half a dozen words, throwing into them all the dramatic force of which she was capable, before Larry, who was watching her closely, saw a strange change come over her.

She stepped back, evidently in fear, and then her hands went up over her eyes, as though to shut out some terrifying sight. At first the audience10 thought it was all part of her acting—though the song did not call for that sort of stage “business.”

A moment later, however, showed the mistake. For Madame Androletti ceased singing, and the strains of the orchestra came to an end with a sudden crash.

The singer cried out something in Italian. What it was Larry did not know, but he could tell, by her tones, that she was frightened.

An instant later she swayed, and she would have fallen to the stage had not her maid and her manager sprung from the wings and caught her.

“Curtain!” Larry heard the manager call quickly, and the big sheet of asbestos slid slowly down. The audience was in an uproar, though a subdued one, and there was no sign of panic.

“She’s fainted!” was whispered on all sides.

Before the curtain was fully down Larry looked under it, and he had a glimpse of the eyes of the stricken singer peering out. And there was fright in them—deadly fright.

Like a flash Larry turned and looked back of him, for it was at some distant point in the hall that Madame Androletti was gazing.

The young reporter saw, standing at the head of an aisle that led directly to the center of the stage, the decorated foreigner who had signaled to the two men the hour of ten. And it was but a little past that now.

This man stood there in plain view, his eyes11 fixed on the slowly falling curtain that was hiding the frightened singer from view, and on his face was a mocking smile. Then he turned and walked slowly from the place. No one but Larry seemed to have noted him, as the eyes of all others were turned on the stage.

“Oh, what was it?” gasped Molly Mason, clinging to Larry’s arm. “Something has happened! She must be ill!”

“I think she has fainted,” said a lady sitting next to Larry’s companion. “Singers often do so from stress of emotion, or from the heat and strain. She has only fainted. She will probably be all right in a little while.”

The orchestra, in answer to a signal from the conductor had swung into a gay number. The curtain had fallen, concealing what was going on behind it.

“It was a faint—just a faint,” every one was saying.

But Larry Dexter thought:

“It was more than a faint. If ever there was deadly fear on a woman’s face, it was on hers. There’s something going on here that the audience knows nothing about, and I’m going to have a try at it. That big man, and those two others are in it, too, I’ll wager. Maybe I’ve stumbled on something more than just an assignment to cover a concert.”

After events were soon to prove Larry Dexter was right.

“Madame Androletti craves the indulgence of the audience for but a few moments. She is indisposed, but will resume her singing directly.”

Thus announced her manager, a few minutes after the fall of the curtain, when the orchestra had been quieted by his upraised hand. Applause followed his little address.

“Oh, I’m so glad it didn’t amount to anything,” said Miss Mason to Larry. “She is such a beautiful singer that I shouldn’t want to miss hearing her. And I might never get the opportunity again. Isn’t it nice that it isn’t really anything?”

“Yes,” assented Larry, but he was far from feeling that it amounted to nothing. The young reporter was doing some hard thinking.

“There may be a big thing back of this, and again it may amount to nothing,” he reasoned with himself. “I’m inclined to think, though, that there’s something doing. Now how am I to set about getting it?

“I guess I’ll sit tight for a while and see what develops. If I go to making inquiries now some13 of the other newspapermen will get ‘wise,’ and I’ll lose any chances of a ‘beat,’ if there’s one in it. I’ll saw wood for a while.”

The orchestra resumed the playing of a spirited air, and while the audience is waiting for the singer to recover, I will take this chance to tell you, my new readers, something more about Larry Dexter, the young reporter.

Larry had come to New York some years before, a farm boy, with an ambition to become a newspaper man. In the first book of this series, entitled “From Office Boy to Reporter; or, The First Step in Journalism,” I told how Larry accomplished this, but not without hard work, and he was in no little danger, because of the mean actions of Peter Manton, a rival copy boy on another paper, the Scorcher. But Larry won out.

In the second book, entitled “Larry Dexter, the Young Reporter,” an account is given of Larry’s “assignments,” or the particular pieces of newspaper work set aside for him. Some of them were very strange, and not a few of them dangerous. Larry had a number of startling adventures in getting big “beats,” or exclusive pieces of news.

His mother, with whom Larry lived, was often worried about him, but Larry had to support her, as well as his sisters, Mary and Lucy, and his little brother James, so he did not give up because his work was hard.

14 Deserved success came to Larry, and he made considerable money, for he discovered deeds to some land that his mother had a right to, but which was being kept from her, and he managed to get possession of the real estate.

Larry came into real prominence in the newspaper world when he made his successful search for Mr. Hampton Potter, the millionaire, as related in the book called “Larry Dexter’s Great Search.”

In that volume are given the details of why Mr. Potter disappeared, and how the young reporter found him, after a long hunt, in which he ran many dangers. During the time he worked on this case Larry and Miss Grace Potter, the millionaire’s daughter, became good friends.

When the Consolidated National Bank was robbed of a million dollars one day, all Wall Street was astounded. An endeavor was made to keep the robbery secret for a time, but Larry, with the help of Mr. Potter, got the story and secured a “scoop,” or “beat.”

Then he began to solve the bank mystery, for it was a mystery as to where the million had gone. In the volume entitled “Larry Dexter and the Bank Mystery,” I give the details of how our hero solved the mystery, got back the million, and secured the arrest of the thief. He did not do this easily, however, and for a long time he was on the wrong “trail.”

The solving of this mystery added further to15 Larry’s fame, and he was more than ever the “star,” or chief reporter, on the Leader, where he had first obtained his start in journalism, and where he preferred to remain, though other papers made him handsome offers.

And now Larry was covering an ordinary concert to oblige a fellow scribe.

“But, unless I’m greatly mistaken,” mused Larry, as the orchestra played on, “this is going to be something more than an ordinary concert. Of course all the other papers will have the story about Madame Androletti fainting in the middle of her song, but I don’t believe they’ll find out why she did.

“I believe it was because she saw that man, though why the sight of him should affect her so is a mystery. That’s where I’ve got to begin; at that man with the foreign decoration. I don’t believe many people noticed him staring at her under the curtain. They were all too intent on the singer herself.”

Larry was doing some hard thinking.

“Oh, isn’t that wonderful—that music?” whispered Miss Mason to him.

“What’s that? Oh, yes, it’s fine!” answered Larry dreamily.

“I don’t believe you even heard it,” she went on, as the wonderful melody rose and fell. “You act just as you did lots of times when you came to see me the time you were working on the bank mystery.”

16 “Well, I feel almost that same way,” spoke Larry with a smile.

“Do you mean to say there’s a mystery here, Larry Dexter?” she asked in a tense whisper. “If there is——”

“Hush,” begged Larry, as the orchestral number came to an end. “Let’s see if she comes out now. I’ll tell you about it later. I may need your help.”

“Oh, fine!” she whispered, with sparkling eyes.

As I have said, Molly Mason had aided Larry in solving the bank mystery, for it was of her that the thief had purchased the valise which he used to hold the million dollars, and Molly gave Larry a valuable clew.

The final chords of the music died away, and there was a hush of expectancy. Would the noted singer be able to go on? Or was her indisposition too much to allow her to do so? Every one waited anxiously for some announcement from behind that big curtain. And Larry looked eagerly toward the stage.

He had made up his mind that he would try to see Madame Androletti after the concert, and ask her what had frightened her. True, she might not tell him, but Larry was too good a newspaperman to mind a refusal. And he had his own way of getting news.

The young reporter looked about the hall. He wanted to see if the big man, with the foreign decoration, was again present. But, if he was,17 our hero failed to get a glimpse of him. Nor could he see the two more ordinarily dressed men who had answered the man’s signal.

“Well, this looks as if something was doing,” said Larry to himself, as there was a movement behind the curtain. A murmur ran through the audience as the manager again stepped before the footlights.

“Oh, I do hope she can sing,” whispered Miss Mason. “I wouldn’t miss it for anything! Oh, what a strain public performers must be under, to have to appear when they are not able.”

“It’s part of the game,” murmured Larry, narrowly watching the manager.

The latter began to speak.

“I am glad to be able to inform you,” he said, “that Madame Androletti has somewhat recovered from her indisposition, and will be able to continue. She craves your indulgence, however, if she is not just exactly in voice, but she will do her best.”

Applause interrupted him.

“Madame Androletti will omit the number she was singing when she fainted,” the conductor went on, “as it might have a bad effect on her nerves. She will substitute another,” and he named it, Larry making a note for the benefit of the musical critic whose place he was temporarily filling.

The manager bowed, there was more applause, and then the singer herself appeared. The applause18 burst out into a great volume of sound, for the audience recognized the pluck it took to come back when physically indisposed, and they appreciated what Madame Androletti was doing.

She bowed and smiled, and signaled for the orchestra to begin.

As the first notes of the accompaniment music burst out Larry noticed that the singer cast a glance around the big hall, and even up into the galleries.

“She’s looking for that man,” thought the young reporter. “What strange influence has he over her? What’s the mystery I’m just on the edge of, I wonder?”

Madame Androletti began to sing, and as the first few notes rippled out she cast a quick glance into the wings. Few noticed it, but Larry did, and as his eyes followed hers he saw a boy, of about ten years of age, standing behind a representation of a tree trunk, part of the stage-setting. He was a boy with dark, curling hair, an Italian, evidently, as was the singer. Larry at once jumped to a conclusion.

“That’s Madame Androletti’s boy!” he thought, and the look of love that was on the singer’s face as she glanced toward the youngster seemed to confirm this.

“By Jove! I believe I’m on the track!” thought Larry Dexter, as he saw the boy move out of sight.

“Doesn’t she sing wonderfully?” whispered Miss Mason to Larry.

“Yes,” he answered, but it was plain that his thoughts were on something else besides the music. He was narrowly watching the singer, occasionally casting glances into the wings, or the scenery at either side of the stage. He was watching for another sight of the boy, who looked so much like Madame Androletti.

The concert went on, and it seemed that nothing more out of the ordinary was to happen. The orchestra played its numbers to perfection, as nearly as Larry could tell, and, as for the singing, he made up his mind that he would report to Mr. Rosberg that it was “slick.”

Larry was not very well “up,” on musical terms, but he knew that the Leader was not paying him as a musical critic, and he did not worry.

“Anyhow, there’ll be a good story in how she collapsed in the middle of a song, whether the report of the concert is good or not,” mused Larry.

20 Madame Androletti came on several times, and sang as encores a number of songs not down on the program. She seemed to be in unusually good spirits, and was roundly applauded. Not a trace of her former indisposition was noticeable.

“I’ll have to wait a bit after the concert is over,” Larry whispered to his companion, during a pause in the program.

“Why?” she asked.

“I want to get an interview with Madame Androletti, and I’ve got to ask the orchestra leader what those extra numbers were.”

“I can do that for you,” offered Molly readily. “I know some of them, as it is, and I can easily get the names of the others.”

“Will you?” he asked eagerly. “That’ll be fine! Then we won’t have to wait so long. Are you sure you won’t mind?”

“Not a bit,” she replied, with a smile. “I fancy I would like to be a reporter.”

“You’d make a better one than lots of ’em who imagine they’re journalists,” said Larry.

The concert was nearing an end. Madame Androletti had sung her last number with great success, and had retired, bowing her thanks for the frantic applause. The curtain started down, and Larry watched it.

Suddenly he became aware that something unusual was taking place behind it. He had a glimpse of the lower part of the singer’s dress, which he could easily distinguish under the curtain.21 She was the only lady in view among a number of gentlemen, who had also taken part in the program. And Larry was sure he saw the singer running across the stage as fast as she could go, with gentlemen trailing after her. Of the latter Larry could only see their legs from their knees down. The curtain was almost on the stage.

The playing of the orchestra drowned any noise that might have otherwise been heard. Larry looked around. The audience was leaving. No one seemed to be paying any attention to the stage, not even the musicians, who were down too low to see under the curtain, in any event.

Larry noted, with satisfaction, that a number of reporters for other papers, whom he had seen earlier in the evening, had gone. They had not stayed to the finish.

“And maybe here’s where I beat ’em!” thought Larry grimly.

He looked about for a sight of the big decorated foreigner, or his confederates, as the young reporter called them, but none was in sight.

“I’m going back of the scenes,” Larry whispered to Molly. “You just ask the orchestra leader the names of the extra numbers. Say you’re from the Leader, and it will be all right. I’ll be back as soon as I can. Wait in the lobby for me.”

With that the young reporter left his seat, and, crossing through an empty row of orchestra22 chairs, he made his way to a lower box, whence he could get behind the curtain.

Larry boldly pushed his way in. He was used to doing that. Besides, at this time, there was no one to stop him. He found himself on an almost deserted stage. It was brilliantly lighted, for scene-shifters were at work, putting away the setting just used, and bringing out another that was to come into play for the next performance the following afternoon.

No one seemed to pay any attention to the young reporter. He knew the general location of the dressing-rooms, and started toward them, intending to ask the first door-tender he saw for Madame Androletti. He was dimly aware of some confusion in the left wings, but he could see nothing.

“That’s the place for me!” thought Larry, hurrying on.

He had crossed the stage, and was pressing ahead, when some one hailed him.

“Hey, young feller, where you goin’?”

“Back here,” answered Larry, non-committally.

“Where’s that?”

“To see Madame Androletti.”

“Got a pass? Got any authority?”

Larry took a quick resolve.

“I’m from the Leader!” he exclaimed. “I want to see Madame Androletti. I covered the concert to-night. It was great. There’s my card. See you later—appointment—important—she23 wants to see me!” murmured Larry, quickly, as he hurried on, thrusting a bit of pasteboard into the man’s hand.

“Wants to see you, eh?” murmured the man.

“Yes,” called back Larry, now some distance away. The young reporter little realized how true his hastily-spoken words would prove to be.

The young newspaper reporter pushed on. He was amid a confusion of scenery now. Tree stumps, castle walls, the ceilings of rooms, a pair of stairs, an arbor covered with trailing vines—the various things used to set the stage. He threaded in and out among them.

A man in a dress suit confronted him, a man whom Larry at once recognized as Madame Androletti’s manager.

“Who are you? What do you want?” the manager asked suspiciously.

Larry realized that he could not bluff this man.

“I’m from the Leader,” said the young reporter quickly. “My card,” and he extended one. “What’s the matter? I’m sure something is wrong. I’ve got to have the story. Why did Madame Androletti faint? What’s up now?”

The manager glanced at Larry’s card.

“Ah, from the Leader, eh? Well, your paper has been very kind to us. I will tell you, though I do not usually see the need of sensationalism. However, there is none here. As you may perhaps know, Madame Androletti, whom I have the honor of representing, personally, travels about24 with her young son, Lorenzo. He is her only child, and, since the death of his father, he has been en tour with his mother. He is always somewhere on the stage when she sings.

“She is very nervous about him, and just now, after her final number, she missed him. She feared he might have strayed away, and been hurt, and she called out. That raised a little alarm, and, as we all know how devoted she is to him, we all began a search for the lad.”

The manager, who was Señor Maurice Cotta, paused.

“Did you find him?” asked Larry.

“His mother did,” was the answer of Señor Cotta. “He was in her dressing-room, I believe. She is close at hand. Hark, I think I can hear her talking to him now.”

He held up a fat, pudgy hand. Larry listened. Plainly enough he could hear a woman’s voice murmuring:

“My son! My boy! My little Lorenzo!” Then followed something in Italian.

“So, you see, there is no story for you, Señor Leader—I beg your pardon—Dexter,” spoke the manager, with a smile. “I am sorry, but you will have only to write about our concert.”

“And about Madame Androletti fainting,” added Larry, feeling rather disappointed, as all true newspaper men do at a story not “panning out.” It is not through heartlessness that they25 are thus regretful, but because it is their profession to hunt out news.

“Oh, yes, her indisposition,” murmured Señor Cotta.

“It was plucky of her to keep on,” said Larry. “I’ll have a good story of it.”

“Ah, thank you.”

“Perhaps I could see her, and ask her if she is all right again,” proposed Larry. “A little interview——”

“Ah, exactly!” exclaimed the manager, not at all unwilling to get all the press notices he could for the prima donna he was managing. “This way, I’ll point out her room. She will see you.”

He left Larry at the door of the dressing-room. It was not the first time our hero had interviewed stage people in their rooms. As he paused, before knocking, he heard the murmuring voice again.

“Ah, my Lorenzo! My little Lorenzo!”

Larry was at once impressed by two things. One was that there was no answering tones of a boy’s voice, and the other was that there was, in the notes of Madame Androletti, extreme anguish. It was not as though she was speaking to her son, but, rather, lamenting him. Larry grew suddenly suspicious.

He knocked on the door. There was a moment of silence, and then a strained voice answered:

“Who is there? Go away! I can see no one!”

Larry resolved on a sudden plan. He was26 going to do a daring thing. There was no other person in sight.

“Madame Androletti!” he called, with his lips close to the portal. “I am a reporter from the Leader. I was at your concert to-night. I saw the man with the foreign decoration. I saw his two confederates. I may be able to help you find your son.”

The door was fairly flung open. The singer, with tears in her eyes, confronted the young reporter.

“What is that?” she whispered hoarsely. “You can find my boy? My Lorenzo—my little boy? Oh, don’t play with me! Who are you? How do you know my boy is gone? Oh, but he is! Why should I try to hide it? He is gone—stolen! Oh, can you help me?” and she held out her hands to Larry with a dramatic gesture.

He had guessed better than he dared to hope. The boy was missing, after all. And she had given the impression to every one else in the theater that he was safe with her! What mystery was here?

Larry stepped into the singer’s dressing-room. She was still attired as she had been on the stage. Her hair was disheveled, and there were traces of tears on her beautiful face.

As the young reporter entered, a woman came from an inner room, and said something in Italian to the singer. The latter answered her in the same language, and then, turning to Larry, said:

“This is my maid, my faithful Goegi. She alone, besides myself, knows that Lorenzo has been taken away—that is except yourself, Señor, and—and the scoundrels who have taken him. Oh, if you know where he is, speak quickly! End my suspense!”

She had closed the door, so that her anguished words might not penetrate to the regions outside of her room, and she gazed tearfully at Larry.

“I did not say I knew where he was,” the young reporter replied gently. “But perhaps I can find him for you. I have worked on several mystery cases, including those of missing persons. I realized28 that something was wrong here, almost as soon as you fainted, and so I made up my mind to see you. Why did you let it be known that your son was with you, when he was not?” asked Larry, for a glimpse around the room showed no signs of the boy. There were several pictures of him, however, and Larry easily recognized in them the little lad he had seen standing in the wings.

“Why did I, señor? Because there has been a great crime committed, a crime of cunning and daring, and I must meet cunning and daring with the same weapons. It is no time for force. I realize that. Neither would it have done any good to have started a pursuit at once. The villains are too cute for that.

“So it was that I might have time to think—time to plan—that I dissembled. I pretended that Lorenzo was in my room when he was not. I did not want them all in here. So I pretended. But you—you discovered my secret. Now, can you help me find my boy? Will you? I do not know you, I have never seen you before, and yet from your face I see that I can trust you. And also you reporters—you are so resourceful. Every day I read of the marvelous things you do. In my country it is not so. But, oh, these wonderful United States! Perhaps you can help me. Will you?”

Once more she held out her hands in a mute appeal.

29 “I will if I can!” exclaimed Larry. “I’ll do all in my power. Listen! I’m a newspaper man, first of all, and though I want to help you, it is only through the power of the press that I can. I ask no reward, only that you let my paper—the Leader—have this news first, exclusively. I’m glad now that you did not raise an alarm. It makes it possible for me to get a ‘beat.’ Tell me all you wish to about the case. Then I’ll get busy.”

“Oh, it is such a long story, I cannot tell half of it now. Sufficient to say that there are enemies of my dead husband who seek to injure me through my only son. They have often sought to get possession of him, but I have foiled them by keeping him close to me always. But this time I failed. Oh, Lorenzo! My poor Lorenzo! where are you?”

She was overcome with emotion for a moment, but soon resumed her story.

“I had been warned,” she said, “but I did not heed. To-night, when I saw that man—my enemy—I was filled with fear. I fainted, and when I was myself again I looked for Lorenzo. He was safe, and I asked him to stand in sight, in the wings, during the rest of the concert. Only by such means would I know he was safe. He did so, and all went well, until the end.

“Then, after my last number, I looked for him. I did not see him. I cried out! I ran! The others were alarmed. They asked me what was30 the matter. I did not tell them all I feared. I said I thought Lorenzo might have fallen down some trap-door, or have stumbled over some scenery—anything to keep the truth back for a time.”

“Why?” asked Larry curiously.

“Because I realized that if I gave an alarm at once, and took after the scoundrels, they might—they might injure my son. There was but one thing to do—meet cunning with cunning—and I took that way.

“When many of my friends, and the stage hands, were looking for my boy, I rushed to my dressing-room, and called out that he was here. Then I shut the door, and told Goegi to keep my secret until I could make my plans.

“And then you—you—a reporter came along—and you have it at your fingers’ ends. I do not understand. How did you know so much?”

“I guessed it,” replied Larry. “We newspaper men have to guess at a lot, and sometimes we hit it. But how long has he been missing? Where did he go? Who took him? Which way did he go? Did any one see him taken away?”

“Oh, what a lot of questions!” cried the singer, and she smiled the least bit through her tears. “I can not answer them all, but I will do my best. I saw Lorenzo standing in the wings when my last song was almost finished. When I looked again he was gone.”

“But some one must have seen him,” insisted31 Larry. “There were a lot of people back of the scenes, and they must have noticed him. Did the stage-doorkeeper see him go out?”

“I do not know. I have not asked. Listen. It is necessary to be secret about this at present. I do not want any publicity.”

“But I can’t help you without publicity,” insisted Larry. “That’s my business. I’m a newspaper reporter. I want the story.”

“Yes! Yes!” exclaimed the singer. “I understand. Let me think!”

She paced rapidly up and down the room. Then she exclaimed:

“I have it. Yours is an afternoon paper, is it not?”

“Yes.”

“And you want—oh, such a funny language—you want a carrot?”

“No, a ‘beat,’” explained Larry, with a smile. “An exclusive story—I want to ‘beat’—get ahead of—all the other papers.”

“I see. Well, I will help you. It may be that my son was taken away to but, temporarily, frighten me—to bring me to terms. In that case he will be brought back to me soon—by to-morrow morning, or I will hear from those who have him. Now, then, if I do not hear, then you may print the story, and I will see no one but you until after it comes out. After that—when the world knows—I am afraid many reporters will——”

32 “Of course they will!” cried Larry. “You’ll be overwhelmed with them, but the more publicity you have the better for you. You’ll have every one in these United States on the lookout for your boy. Newspapers help a lot. All I want is the first story, and after that the others can come in.”

“All right. I agree to your plan. It’s a good one. But do you know who that man with the decoration was? He is Señor Delcato Parloti, a plotter, and schemer, and the enemy of my late husband. Oh, how I fear him!”

“And those other two men—to whom he signaled?”

“I do not know them—perhaps his aids. Oh, this is terrible!” and once more she gave way to her grief.

Presently she mastered herself again, and resumed:

“I have friends—powerful friends, and I will set them quietly on the trail of this Parloti. If I do not have word with him by morning, or if I do not hear from him, then I will send for you, and you may have the story.

“In fact, you may have the story anyhow, for in one case it will be about the return of my son to me, and in the other——”

She could not finish, but Larry knew what she meant.

Rapidly he asked a few more questions, until he had more of the story. With what would be33 told him later, he knew he would have a startling article for the Leader.

Bidding the singer good-by, and promising to keep her secret until the time for publicity came, Larry took his leave, agreeing to hold himself in readiness for her summons the next morning.

As the young reporter left the dressing-room he saw no signs of excitement on the now almost deserted stage. Clearly all the others had accepted Madame Androletti’s innocent deception, practiced to bring about the return of her son.

“But I don’t see how she’s going to get out of the theater without letting some one see that the boy isn’t with her,” thought Larry. “That’ll be sure to bring up questions. However, she may be actress enough to carry it off with the aid of her maid. Say, but I’m on the track of a big story, all right!”

A few minutes later he joined Molly Mason in the lobby.

“Did I keep you waiting too long?” he asked.

“Oh, no, I enjoyed it! I don’t mean that!” she exclaimed, with a blush at Larry’s queer look. “I don’t mean that I enjoyed your absence. But I was talking music to the leader of the orchestra. He gave me all the information you wanted. I wrote it on this program for you.”

“Thanks! You’re getting to be quite a reporter!” said Larry with a smile. “And now for home!” he added as he summoned the taxicab.

“Oh, but did you get your story?” she asked.

34 “Part of it,” replied Larry. “I’m hoping for more. It may be a big one.”

Then he turned the subject to the concert proper, and they talked of that until the girl’s home was reached.

“Thank you for a lovely time,” she whispered.

“You’re welcome,” replied Larry, and he thought to himself that, after all, perhaps his substituting for the musical critic might lead to big results.

Late as it was he called up Mr. Emberg, the city editor, at his home, and gave an inkling of what was in the wind.

“Come right over here, Larry,” commanded his chief, and soon the two were in consultation.

“So you’ll get a story out of it, no matter which way it goes,” commented Mr. Emberg, when Larry had told him the facts.

“It looks so. I’ve got to wait until morning, though.”

“All right. Be ready to jump right out on this. As I see it, even if she gets the stolen boy back, we’ll have a two or three days’ yarn out of it. So you drop everything else, Larry, and take this new assignment.”

“And if the boy isn’t returned?”

“Then it’s your assignment to find him. You solved the bank mystery, and that about Mr. Potter, so try your hand at this.”

As Larry went home, after leaving the city35 editor, he had a feeling that all the hard assignments were coming his way.

“But I like it!” he exclaimed, half aloud. “And I’ll do my best to locate that little chap. I wonder why there are such men as kidnappers in the world?”

Larry looked eagerly over the morning papers. Though all of them had a story about the temporary indisposition of the talented singer, none of them had the real account.

“Now for a ‘beat’!” cried Larry to himself.

The telephone rang.

“Mr. Dexter!” sang out the boy whose duty it was to answer it. “You’re wanted.”

Larry sprang to the instrument, and, as he did so he heard a voice saying:

“This is Madame Androletti! Come as quickly as you can!”

The start which Larry gave when he heard the voice of the prima donna over the telephone was noticed by the city editor.

“What is it?” asked Mr. Emberg, slipping to Larry’s side, just as the young reporter was telling Madame Androletti over the wire that he would call on her at once.

“It’s the stolen boy case!” he answered, when he had hung up the receiver. “He can’t have come back, and she can’t have had any trace of him, for she was half crying when she told me to come up. I’m going to get the story. It’s ripe now, and it’s a good one. There’s something big back of it all.”

“That’s the way to talk, Larry. Get right after it! Can you get a ‘scoop’ out of it?”

“I’m going to try hard. None of the other papers are on to it yet.”

“Look out that the Scorcher doesn’t spring some fake sensation on you. This is just their kind of a yarn. Beat ’em if you can.”

“I will,” and with that Larry hurried out to37 catch the elevator. Mr. Emberg stepped out into the corridor with him.

“There are some queer points to this story, Larry,” he said. “I can’t understand why Madame Androletti shouldn’t have raised an alarm at once when she found her son missing.”

“It does seem odd,” agreed the young reporter. “And yet she explains that by saying that the case was so peculiar that if she went out and made a big fuss, and called in the police, the kidnappers might do her, or her son, some harm. It’s just like when some one does something mean to you, and you pretend not to know it for a while, laying low, and holding back, so as to get a better chance to get even with ’em.”

“I see,” agreed the city editor, with a laugh at Larry’s boyish explanation. “And yet the kidnappers must know that Madame Androletti is aware that her son has been spirited away.”

“Of course. And yet if she continues to act quietly, as she has done, it may make them curious to find out what her game is, and they may not carry out their original plan, whatever it is. Then, too, there’s no doubt but what this is done for a ransom, and sooner or later an offer will come from the fellows who have the boy, stating how much they want to return him.”

“I suppose so. There ought to be a heavier punishment for kidnapping than at present. Well, get along, Larry.”

The young reporter lost no time in reaching the38 apartments of the singer. She had several rooms in a large hotel, on Murray Hill, New York, where she and her maid stayed. Up to the time he was taken away from the theater, her son had also been there.

Larry found Madame Androletti in tears, but she soon composed herself, and began to tell her story.

“I have heard something about you, since I met you last night,” she said, by way of preface.

“Nothing unpleasant, I hope,” spoke Larry.

“On the contrary, good. I was talking with my maid about you. She has been in this country some time, and she reads much of your papers. You are the reporter, are you not, who solved the Wall Street bank mystery?”

“Yes, I was lucky enough to do that,” replied Larry.

“And you also searched for and found Mr. Potter, the missing millionaire. Ah, I have sung at his charming house.”

“Yes, I located him,” said Larry. “But——”

“Ah, you are too modest!” she interrupted. “But I was glad to know this, for after two such celebrated cases I feel sure that you can find my son.”

“I’m going to do my best, Madame Androletti, if I have to trace him clear across the continent. But, if you please, I’d like to hear the particulars about him, and who this man is—the man with the39 foreign decoration—who probably took him away.”

“Ah, he is a villain, a bad-hearted man!” the singer exclaimed. “I will tell you.”

She then stated briefly, that Delcato Parloti, at the sight of whom in the theater she had fainted, was a distant relative of her late husband.

“My husband, who lived near Rome, Italy, was a very rich man,” she went on, “and had he not married me, all his estate at his death would have passed to Parloti and others. But after our marriage, of course, I was the one who would inherit the property, and this left Parloti nothing but what he had of his own—he had no expectation of a fortune. This made him very bitter against my husband and myself.

“Lorenzo is my only child, and when my husband died, about three years ago, this Parloti at once began to persecute me. He did all in his power to get my fortune away from me, and at last began to threaten me through my son. That made me very much afraid, and I fled from Italy to this country. I thought I would be safe.

“Parloti sent me a message not long ago. He said if I would not sign over to him all my rights in the property my husband had left, my son would be taken from me. But the cruel part of it is that, under the law, I can not sign away those rights. They fall to my son. It is quite complicated, and I do not understand it. Gladly would I give up all my husband left, retaining only such a40 modest fortune as I have in my own right, to save my son, but I cannot—cannot, under the law sign away those rights, and this bad man will not believe it. He insists that I give him the fortune, or he will take my son until I do.

“So, as I said, I fled from Italy. I hoped I would be safe, and for some years I have been. Then, when I think all is well, that man last night walked into the hall where I was singing. Do you wonder I faint, señor?”

“No, indeed!” exclaimed Larry, who had been making rapid notes of the story, with names, dates and other details that I have omitted here.

“And so they took my boy!” cried the singer. “They have stolen him from me! But with your help, good Señor Dexter, you who solved the million-dollar bank mystery, we will get him back, will we not?”

“We will!” cried Larry enthusiastically, though he knew that there was plenty of hard work ahead of him, and but a slim chance that he would be successful.

“I’ll do all I can,” he said, “and so will every one on the Leader. You’ll have all the help the newspaper can give.”

“Oh, how can I reward you?” she cried. “My fortune——”

“All the reward I ask is to have the story alone—exclusively!” cried Larry. “I want a ‘scoop’.”

“Oh, you reporters! Such funny words! First,41 you want a cabbage is it——?” and she looked at Larry, and smiled.

“No, a ‘beat,’” he corrected.

“Oh, yes. And then you demand what you call a—shovel——”

“No, a ‘scoop.’ I guess it means shoveling all the other fellows out of the way, though,” explained the young reporter. “But if I get either a ‘beat,’ or a ‘scoop,’ it’s all the same. Now I’m off to the office, to write this story, and then I’ll come back and make some plans. I want to know more about this Parloti. If any reporters from other papers come to see you, please——”

He was interrupted by the ringing of the private telephone in the singer’s room. She answered it, repeating some of the message that came to her.

“A Mr. Peter Manton to see me,” she said aloud. “But I know no Señor Manton. Tell him——”

In a flash Larry was at her side.

“That’s another reporter,” he whispered. “My rival. He’s on the Scorcher. Don’t give him the story.”

“What shall I do? If I do not see him, he may print some terribly untrue story, and——”

“That’s just what the Scorcher would be likely to do, anyhow,” agreed Larry, “though Pete isn’t such a bad sort himself. Let me think. I’ll tell you. Can’t you fool him in some way? Sort of string him along until I get away, and have my42 story in the first edition of the Leader. Then I don’t care what he prints.”

“Yes, yes! I see. You mean to ‘scoop’ him!”

“That’s it.”

“And I will help you!” The singer was excited now, and she was more like herself, a great actress. “I will fool him! I and Goegi, my maid. We will change places. She shall be the mistress, and I the maid. Remember, Goegi, you are the singer, and I am your attendant. And you speak no English. Do not forget that. I will have to translate what you say to this reporter. We will see him up here, when Señor Dexter has gone. Is it not so?” she asked, turning to Larry.

“Fine!” he cried. “That ought to fool him all right. I’ll hurry in now. Detain him as long as you can. It will be some little while until we can get out an extra on this.”

“I will see Señor Manton in a few minutes,” spoke Madame Androletti over the wire, which she had held open.

Larry hurried out of the room, going down in the servant’s elevator, to avoid landing in the hotel lobby, and so meeting his old rival, Peter Manton.

“I guess I’ve ‘scooped’ the Scorcher,” thought our hero, as he hastened toward his office with the big story all ready to write.

Larry heard afterward what happened to Peter. The reporter for the Scorcher, after waiting impatiently for some time in the hotel corridor, was shown up to the singer’s room. Then came another wait.

Madame Androletti, attired as her maid, came out and announced that the “singer” would see him soon.

“But I can’t wait!” insisted Peter. “I’m in a big hurry. I have a tip that Madame Androletti’s son is ill, or something, and I want a story about it.”

“The Madame will see you at once!” exclaimed the pretended maid, with a smile. In spite of the fact that her heart was torn with anguish at the loss of her son, the singer was enough of an actress to carry out the rôle she had assumed for Larry’s sake.

There was another wait, while Madame Androletti pretended to go and confer with her mistress in another room.

“Oh, this delay is fierce!” exclaimed Peter,44 who, on looking at his watch, saw that it was nearly first edition time. “I’ll never get the story in time for the paper. And I’ll wager that Larry Dexter is after it, too. I want to beat him!”

Another wait, and then, thinking that this part of the game had been carried far enough, Goegi came in. Attired in the garments of her mistress, and with a veil over her face, the disguise was sufficiently good to deceive Peter.

“Now for the story!” he cried. “Where is your son, madame?” he demanded. “I understand that something has happened to him.”

And now another source of delay developed. It appeared that the pretended singer could not speak English, and the real singer translated to her maid what Peter had asked, and also her replies. This took more time.

“The story! The story!” insisted Peter, walking up and down the room in his excitement. “What about the boy?”

“What has the señor heard, and where?” asked the maid, which question was duly translated, the inquiry of the real singer having been made in Italian.

“Oh, what has that got to do with it?” demanded the representative of the Scorcher, but he condescended to state that he had called casually at the theater to learn if Madame Androletti would give the remainder of her performances for the week. There some stage hand, who had heard the excitement of the night before, had hinted45 that something was wrong with the singer’s son. Like any good newspaper man, Peter had followed this up with a visit to Madame Androletti. He had, however, not the least inkling of what the real story was.

And then began a battle of wits. On his part, by skilful questioning, Peter endeavored to find out what was at the bottom of the affair. On the part of the singer and her maid, to be loyal to Larry, they tangled matters up as much as they could, by reason of two languages being used. They were fighting for delay, and when, finally, Peter did get a glimmer of the truth it was too late for his first edition.

All he knew, when he finally rushed away from the singer’s room, was that her son had mysteriously disappeared, whether kidnapped or not, Madame Androletti would not say positively.

“I’m going to telephone that in,” decided Peter. “It will make a scare head for the Scorcher.”

He got his city editor on the wire.

“I’ve got a great story!” exclaimed Peter. “It’s about that Italian singer and her son. It’s a peach!”

“Too late!” said the city editor briefly.

“Too late?” gasped Peter. “Why?”

“Because the Leader is just on the street with the whole yarn, double-leaded, and with scare heads. You’re ‘scooped,’ Peter! Come on in and46 fix up something to cover us, but we’re beaten to a frazzle.”

“Well, I’ll be jiggered!” exclaimed Larry’s rival, as he hung up the telephone receiver. “They fooled me! This is another one you’ve put over on me, Larry Dexter!”

But Larry had other things to think of, now that he had secured his coveted “scoop.” One of them was to provide for a “follow,” or secondary story, and the other was to get on the trail of the men who had spirited the little lad away.

“For there was more than one in this game,” decided Larry.

He thought of the big, well-dressed man, with the foreign decoration on his coat, and the two rather poorly-dressed individuals in the back of the hall to whom the other had signaled.

“I think those three are in it,” decided the young reporter, “and I’ve got to get some clews that will lead me to them. What had I better do first?”

A moment’s thought told him that the best source of information was Madame Androletti herself.

“She may know where to start to look for this Parloti,” reasoned Larry. “I want to see him first. He is the leader in this business, I’m sure.”

“Did you get your turnip?” asked the singer of the young reporter, when she received him again, a few hours later.

Larry looked puzzled, until the maid, who had47 now assumed her real character, said something in a low voice in Italian to her mistress.

“Oh, I mean your ‘beat’!” exclaimed Madame Androletti. “I never can seem to think of the right name of the vegetable. But did you get it?”

“Yes, thank you,” replied Larry. Then she told him how she had detained Peter until it was too late for him to get in his story.

“And now about Parloti,” suggested the young reporter, after he had been given several more minor facts about the missing boy. He was also provided with a photograph, to use when he made inquiries about him as he worked on the case.

Madame Androletti was not sure of the address of the man she feared, but she told Larry of several hotels where Italians of note were in the habit of stopping.

“I’ll trace him!” exclaimed our hero, as he started out.

It was not as easy as he had hoped, but late that afternoon he did find the place where the suspected man was registered.

“Is he in?” Larry asked the clerk at the desk.

A glance into the letter-box corresponding to the room occupied by Parloti showed that the key was absent.

“He may be in his room,” said the clerk, and a bell boy soon brought word that this was so, and that Larry was to go up.

“Come, this is too easy!” reflected the reporter. “I don’t know that I exactly like this. If he had48 refused to see me it would have been more natural. He must know who I am, and he has probably seen the Leader by this time, with his name in it. Yet, instead of hiding away, he calmly stays here and sends word that he’ll see me. He doesn’t act like a criminal. I wonder if, after all, Madame Androletti is right. I’m glad I qualified the yarn, and didn’t say, positively, that Parloti was the one who had the boy.”

Larry was enough of a newspaper man to know how to do this. He did not want to involve the paper in a libel suit. For it is one thing to suspect a man of a crime, and it is another to convict him. And, until a person is convicted no newspaper dare, legally, state that he is guilty.

“Ah, Señor Dexter, of the Leader,” said Parloti, with a slight raising of his eyebrows as Larry entered the room.

“Yes,” replied the young reporter.

“And what can I do for you?”

“I guess you know why I’m here,” spoke Larry, bluntly.

“I have read your charming paper—yes.” There was a crafty look, not unmixed with anger, in the eyes of the man.

“Is it true, what Madame Androletti says about you?” asked Larry boldly. “Do you know where her son is? Did you have a hand in taking him away?”

“I do not know where he is! I did not take him away!” cried the man excitedly. “I shall also49 demand a retraction from your paper. You have slandered me.”

“We’ll stand the damage,” spoke Larry, coolly. “But I guess there are certain things true in that story; aren’t they?”

“No! Not a one! Not a one! It is all nonsense! Who am I that I should kidnap little boys? Who am I that I should want the fortune of Madame Androletti? Answer me that, Mr. Reporter?”

“I don’t know who you are, and I don’t care!” exclaimed Larry, boldly, for the manner of the man did not impress him. The young reporter believed Parloti to be “bluffing.”

“You shall soon learn who I am!” the Italian went on. “I am not to be insulted with impunity! I shall demand a retraction from your editor, or he will meet me on the field of honor!”

“We don’t have such fields over here,” spoke Larry with a smile. “We use them for baseball diamonds and football gridirons. I’m afraid you’ll have to think of something else.”

“I shall think of my honor!” cried the Italian. “For what else did you come to see me?”

“To learn if you wanted to make any statement—to give your side of the kidnapping,” replied Larry.

“Kidnapping! There has been no kidnapping!” insisted Parloti, shaking his fist at Larry, who remained cool.

“Madame Androletti’s son has been stolen away,” went on the reporter.

50 “What is that to me? I tell you I know nothing of it. I have not seen her. I——”

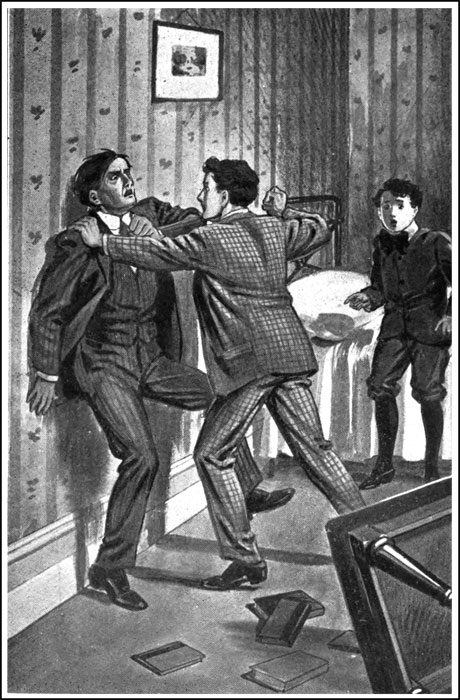

“You were in the music hall last night!” interrupted Larry; “I saw you. I saw you look at her, and it was when she saw you she fainted. I saw you give the ‘ten’ signal to your tools. I was there!” and Larry, with a sudden impulse, laid his hand on his cheek as he had seen Parloti do.

“Ha! What is that? You saw! You! I must——”

The man was very much excited. He fairly rushed at Larry, for the Italian had been taken by surprise.

“I—I—I must—I must be calm,” he whispered, as his arm sank to his side.

“Well?” asked Larry suggestively.

“I will say no more to you! I will answer no more questions. Go! I desire to be alone!”

“Then you won’t tell where the stolen boy is?” asked Larry.

“No! No! A thousand times, no! I will say nothing. Get out of here!” and once more he rushed at Larry, who stood his ground, and looked fearlessly at the infuriated man.

“Leave at once, or I shall summon a porter to remove you!” cried Parloti, reaching for the electric-bell signal.

His voice was high, and his face was red with passion. Larry thought it best to leave, and, as he turned to the door, he became aware of a motion51 in a room adjoining that in which he and the Italian stood.

A connecting portal swung partly open, and Larry looked eagerly toward it, hoping against hope that he might get a glimpse of the stolen boy.

He did not see Lorenzo, however, but he did see some one, at the sight of whose face he started.

For there, peering at him from the half-opened door, was one of the two men who had been in the rear of the hall—one of those to whom Parloti had signaled.

“By Jove!” exclaimed Larry, under his breath.

“Shut that door!” yelled Parloti in Italian, and the portal was slammed, while Larry hurried off, not caring to risk a personal encounter with the excited man who confronted him.

“Well, there’s not much to be gotten out of him, in his present state of mind,” mused Larry as he went down in the hotel elevator, with a vision of the excited Parloti before him. “But I sure did stumble on a mystery. That man in the other room showed his face just at the right time for me, and at the wrong time for Parloti.

“I’ll wager Parloti didn’t want it known that he was in the same apartment with him. Now if I could only locate the other one I’d be pretty close to where the boy is. Maybe he’s in that hotel!”

For a moment Larry had half a notion to go back and demand to be allowed to search the rooms. Then a moment’s reflection told him that his wild and half-formed idea could not be true.

The hotel was a well-known one, and above suspicion. It would be impossible to conceal a kidnapped boy in it, unknown to the management, especially after all the publicity that had been given to the case, for, after Larry’s paper came out with the big “scoop,” all the other New York journals followed, and the whole city was ringing53 with the story. The police were urged by editorials, and by frenzied letters, written to the papers by frantic fathers and mothers, to leave nothing undone to get the kidnappers, and recover the boy.

“Parloti thought he could bluff me,” thought Larry, “but I’m certain he had a hand in this. He’s playing a bold game. I guess I need some real police aid on this case. I’ll go down to headquarters.”

This he did and after a consultation with a certain officer, whom he knew well, Larry and the latter decided on a plan of action.

On the reporter’s promise that the detective should get the proper newspaper credit due him, the latter offered to proceed in the case, and hold for Larry exclusively all the information he got. Larry needed some one with the proper legal authority to make a search of Parloti’s rooms, and also look up the two men whom the young reporter believed were the tools of the chief plotter.

“Sure I’ll do it,” agreed Detective Nyler, who had helped Larry with suggestions in the bank mystery. “It’ll be a feather in my cap if I can arrest the kidnappers.”

But it was decided to act cautiously, and to this end a watch was put on the suspected man, his hotel being under surveillance day and night. It was ascertained that the man who had been with him had gone out soon after Larry’s visit, and no54 one knew who he was. It would have been worse than useless, the young reporter knew, to question Parloti again.

The Italian did not carry out his threat to “call out” the editor of the Leader unless a retraction was made. And the only retraction that was made was a statement to the effect that Parloti denied knowing anything of the whereabouts of the stolen boy, or that he ever planned to take him.

Meanwhile Madame Androletti was plunged in grief, in spite of her brave attitude, and of the aid she had given Larry in trying to solve the mystery. She gave up her concert tour and, to avoid further publicity, went to a small quiet hotel in New York, under an assumed name, Larry alone, of those outside her manager and immediate friends, knowing where she was.

“And now!” exclaimed Larry, late that night, “I’ve got to get after some other clews. Let’s see, where’s the first place to start? At the music hall, of course, from where the boy disappeared. I ought to have gone there at first, but I couldn’t cover everything. I’ll go there now. It will be some time before the evening performance.”

For a theatrical company had replaced the singer as an attraction. The magic of Larry’s card admitted him behind the scenes. He wanted to talk with some of the scene-shifters, the door-keeper, and others, for he had been unable to learn anything of moment from those who made up the personal company of Madame Androletti. They55 had been too busy with the performance to pay much attention to the boy.

All that they knew was that he had been roving about the wings, watching his mother sing. Then he had mysteriously vanished.

And, after much questioning, Larry was forced to admit that the stage hands and the door-keeper knew little more. A number of the scene-shifters and mechanics had noted the lad, for the singer had played a week’s engagement, and the boy had been present each night, and at the matinees.

“But did any of you see him taken away?” asked Larry.

None of them had.

“How many stage doors are there?” asked the young reporter, and, learning that there were several ways of getting behind the scenes, aside from passing back of them from the front of the theater, Larry inquired of the door-keepers.

None of them had seen the boy go out alone, or in company with any one. The door-keepers were positive that this was so, and they were veterans at their business, and thoroughly to be relied upon.

For it is hard to pass the door-keeper of the stage, unless you are known, or have proper credentials, and no strangers had entered or come out that night, each guard was certain.

“But the boy disappeared!” insisted Larry. “Where did he go to? He certainly didn’t vanish into the air. Some one must have taken him out.”

56 “Or else he walked out himself, and was captured later,” suggested a stage hand.

“In that case some of the door-keepers would have seen him,” replied Larry, and that closed this phase of the matter.

The boy’s hat and light coat were found in his mother’s dressing-room, showing that he had been taken away suddenly, and without time for the plotters to properly attire him for going out. Or perhaps they had brought along a cap and a coat for him. This was likely.

“There are almost as many ends to this case as there were to the bank mystery,” mused Larry when his questioning had brought him no new clews. “But I’ll find something sooner or later.”

He even questioned the musicians, for he thought it possible that Lorenzo might have, in some way, slipped down into the under-stage apartment set aside for the use of the orchestra. But none of them had seen the stolen lad.

Baffled, but not discouraged, Larry went home, hoping that the morning would bring some new information. It did not, though he managed to get a story concerning the activities of his friend, Detective Nyler, who had made a search of Parloti’s rooms in the hotel. There had been no trace of the stolen boy there.

“But I found out the name of the fellow you saw in the room,” said the officer. “One of those who were in the back of the theater, and to whom Parloti signaled.”

57 “You did! Good! What is it?”

“Well, it may be a fake one, but Parloti called him Giovanni Ferrot. So you can put that down as part of a clew, though it doesn’t amount to much.”

“And where is Ferrot?”

“Gone. Nobody knows where. But I’m going to look for him. I have a good description of him.”

The next few days brought forth little that was new. Larry kept relentlessly on the trail of Parloti, as did the police.

Though the young reporter did not visit the suspected man openly, he hung about his hotel, trailed and followed him when he went out, and kept so close a watch over the Italian that the quarry became nervously indignant.

“When are you going to let me alone?” he cried to Larry, one afternoon, turning suddenly on the reporter.

“When you tell me what I want to know,” was the calm answer.

“But I know nothing, I tell you! I have not the stolen boy! If I had, would I remain openly here as I do?”

That was rather a poser for Larry. He did not know what to say. But still he kept his watch on Parloti.

Thinking the matter over calmly, Larry was forced to admit that one weak link of the chain that he sought to forge about Parloti was the fact that the man stayed on at his hotel openly, in spite of the suspicion against him.

“If he’s guilty I should think he’d escape at the first opportunity,” said the city editor, while talking over the case with Larry.

“Perhaps he knows that if he tried to do that he’d be arrested,” suggested the young reporter. “Flight would be an evidence of guilt, and Nyler is keeping a close watch on him. So am I.”

“And he doesn’t show the least sign of going away?”

“Not the least. Lots of reporters from other papers have interviewed him, and, though he admits that he is not on friendly terms with Madame Androletti, he says he knows nothing about the taking away of the boy.”

“Why does he admit being unfriendly?”

“Because, he says, that the fortune she has is rightfully his, and he has brought suit to recover59 it. But he was defeated in the Italian courts. He says he will yet have justice, but he denies that he would try to get it through taking away a little boy.”

“What do you think, Larry?”

“Well, I don’t know what to think. I believe Parloti had a hand in the matter, in spite of what he says. But it’s like the case of the bank mystery. I might be mistaken. And there’s another point in this case like that Wall Street robbery.”

“What’s that?” inquired the city editor.

“It’s this: If Parloti is guilty, the fact of his staying here, and facing the music, and his constant denials, prove him a good actor, just as that bank clerk was, in staying in the bank when he had hidden the million away.”

“That’s so. Well, keep right after him, Larry, and see what you can get out of it. You might yet find the boy, and get a big ‘beat’.”

“I’d like to, not only for the ‘scoop,’ but because I would like to help Madame Androletti. She is beginning to lose hope. The suspense is terrible for her.”

“I can imagine it would be. Well, do your best for her, and follow the clews wherever they lead. Don’t mind the expense; the paper will stand it.”

Larry redoubled his watch over Parloti, to that individual’s annoyance. He could scarcely go anywhere but either Larry or Detective Nyler, or some one in their interests, watched him. It would have been a hard matter for him to have60 escaped, but apparently he did not want to do that. In vain, however, did he endeavor to shake off his relentless personal shadowers.

Meanwhile nothing had been heard of the two “tools,” as Larry called them, meaning the men who had been in the back of the hall, to whom Parloti had apparently signaled the night the boy was stolen. The big Italian refused to even talk about them, and, beyond learning the name of one—Ferrot—no information was obtained. Both seemed to have vanished utterly, and Larry suspected that they had the boy in custody, and were holding him until Parloti could join them.

“Then will come a demand for money on poor Madame Androletti,” mused Larry, “and I suppose she’ll give in, for the sake of getting her son back. But I wish I could get him without her paying any ransom. I’d like to catch those kidnappers, too, and see them sent to jail for long terms.”

But the more Larry puzzled over the case the more he became confused. There were few clews of any account and those he seemed to have run to the ground.

“But I am not giving up!” he exclaimed grimly. And he kept on seeking for the clew that would lead him to the hiding place of the stolen boy.

The case was now world-wide, for the singer was a well-known character. Nearly every paper in the country had published a picture of the missing lad, and the reward which his mother had61 offered stimulated many to make a search for him.