This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook.

Title: Stanley's Story

Through the Wilds of Africa: a Thrilling Narrative of His Remarkable Adventures, Terrible Experiences, Wonderful Discoveries and Amazing Achievements in the Dark Continent

Author: A. G. Feather

Release Date: February 24, 2020 [eBook #61496]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK STANLEY'S STORY***

| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through Internet Archive. See https://archive.org/details/stanleysstoryort00feat |

The book, and this e-text, use ´ and ` for minutes and seconds of angle, respectively.

Please see the Transcriber’s Notes at the end of this text.

The cover image has been created for this text, and is placed in the public domain.

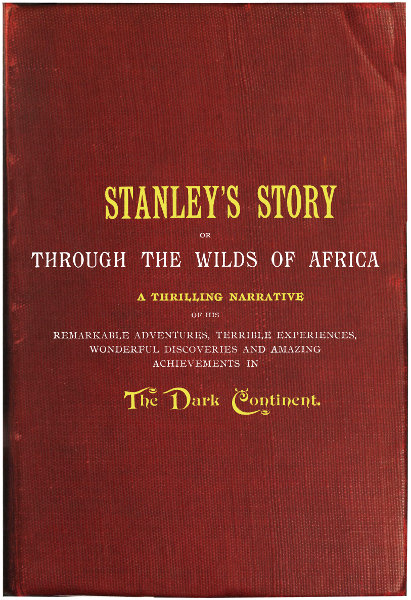

H. M. STANLEYEMIN BEY

OR

THROUGH THE WILDS OF AFRICA

A THRILLING NARRATIVE

OF HIS

REMARKABLE ADVENTURES, TERRIBLE EXPERIENCES,

WONDERFUL DISCOVERIES AND AMAZING

ACHIEVEMENTS IN

The Dark Continent.

Giving Accounts of his Discovery of Dr. Livingstone, the Lost Explorer; his

Great Overland Journey Across the Dark Continent; the Great Mysteries

of the past five thousand years, as solved by him; his Exploration

of the Congo; the Founding of the Congo Free State, and the

Opening of Equatorial Africa to Commerce, Civilization

and Christianity; his Expedition to the Relief of

Emin Bey in the Egyptian Soudan, with its

Terrible Experiences of Starvation,

Misery and Death; and a

Resume of all his Wonderful Discoveries and their Great Value to

Geographical and Scientific Knowledge, to the present time,

and covering his entire career in

SOUTHERN AND CENTRAL AFRICA.

From Information, Data, and the Official Reports

OF

HENRY M. STANLEY.

By our Special Foreign Correspondent,

COL. A. G. FEATHER.

RICHLY AND PROFUSELY EMBELLISHED WITH MANY FULL-PAGE PLAIN AND COLORED ILLUSTRATIONS.

PHILADELPHIA:

JOHN E. POTTER & COMPANY,

1111 and 1113 Market Street.

By JOHN E. POTTER & COMPANY,

1890.

All Rights Reserved.

CAUTION.

The Engravings in this book, as well as the printed matter,

being fully protected by copyright, we desire to

caution all persons against copying or re-

producing in any form. Any one so

offending will be prosecuted.

TO THE

BRAVE AND FAITHFUL FOLLOWERS

THROUGH WHOSE

FIDELITY AND UNSELFISH DEVOTION TO DUTY, UNFALTERING COURAGE

AND PATIENT SUFFERING UNDER SEVERE TRIALS, HE WAS

ENABLED TO SUCCESSFULLY ACCOMPLISH

HIS GREAT MISSION,

AS ALSO

To those Public Spirited Citizens

WHO THROUGH THEIR GENEROUS LIBERALITY SO ABLY AND

CHEERFULLY SUPPORTED

The Emin Bey Relief Expedition,

THIS VOLUME IS MOST CORDIALLY

DEDICATED.

[v]

Fifty

years have hardly elapsed since Dr. Livingstone first

entered the dark and benighted regions of South Africa as a

missionary. Till then the country had been little less than a

sealed book to the outside world, and the student of geography

only knew its face as a blank and unknown void. History also stood

silent, giving little information or evidence of what these hidden

recesses in the Dark Continent might contain. What knowledge

the world did have was limited to the coasts, and that only obtained

through the prominence given it by the atrocious slave trade—at

that time the leading feature of its commerce. But what a mighty

change has been wrought since then! To-day, thanks to the missionary

spirit, labors and exploits of Livingstone, who first planted

the germs of Civilization and Christianity within her borders, as well

as to the patient and persevering spirit of the bold and intrepid

Stanley, upon whose shoulders so fitly fell the mantle of the dead

Livingstone, we are in possession of a more comprehensive map of

Africa. History, too, is no longer silent. Her pages now teem

with marvellous accounts of the wonderful regions developed by

these and other daring explorers—with the still more remarkable

tales of the immeasurable wealth lying dormant and quietly awaiting

the developing arms of Commerce. Geography and Science

have also received a mighty impetus through the discoveries made

by these fearless adventurers into the wilds of the Dark Continent;

and to-day we are enabled to record the fact that a satisfactory

solution to the great problems, which for ages have so much mystified

the world, has been arrived at. The return of Stanley and his

followers, with the fruits of their experiences and the light which

they are able to throw upon the subject, will give to the literature

of the world an addition of almost incalculable value. The expedition

will take historic rank with the famous “retreat of the ten[vi]

thousand” under Xenophon. As the tale unfolds, of the arduous

toils and dangers encountered in the vast African wilderness, wonder

at its success increases.

Fifty

years have hardly elapsed since Dr. Livingstone first

entered the dark and benighted regions of South Africa as a

missionary. Till then the country had been little less than a

sealed book to the outside world, and the student of geography

only knew its face as a blank and unknown void. History also stood

silent, giving little information or evidence of what these hidden

recesses in the Dark Continent might contain. What knowledge

the world did have was limited to the coasts, and that only obtained

through the prominence given it by the atrocious slave trade—at

that time the leading feature of its commerce. But what a mighty

change has been wrought since then! To-day, thanks to the missionary

spirit, labors and exploits of Livingstone, who first planted

the germs of Civilization and Christianity within her borders, as well

as to the patient and persevering spirit of the bold and intrepid

Stanley, upon whose shoulders so fitly fell the mantle of the dead

Livingstone, we are in possession of a more comprehensive map of

Africa. History, too, is no longer silent. Her pages now teem

with marvellous accounts of the wonderful regions developed by

these and other daring explorers—with the still more remarkable

tales of the immeasurable wealth lying dormant and quietly awaiting

the developing arms of Commerce. Geography and Science

have also received a mighty impetus through the discoveries made

by these fearless adventurers into the wilds of the Dark Continent;

and to-day we are enabled to record the fact that a satisfactory

solution to the great problems, which for ages have so much mystified

the world, has been arrived at. The return of Stanley and his

followers, with the fruits of their experiences and the light which

they are able to throw upon the subject, will give to the literature

of the world an addition of almost incalculable value. The expedition

will take historic rank with the famous “retreat of the ten[vi]

thousand” under Xenophon. As the tale unfolds, of the arduous

toils and dangers encountered in the vast African wilderness, wonder

at its success increases.

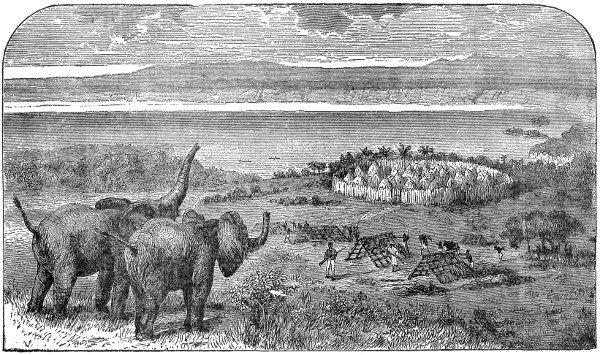

Though much has been done since Livingstone’s time to fill up the blanks of Central Africa’s physical geography, no expedition has ever returned with a richer harvest of discoveries than Stanley’s last. The almost impenetrable forest of the Aruwimi, probably the largest of African forests—extending over four hundred miles of latitude and longitude—with a dense jungle in all stages of decay, resounding with the murmurs of monkeys and chimpanzees, strange noises of birds and animals, and the crashes of troops of elephants rushing through the dark and tangled copse, is an obstacle that, once surmounted, gives us the hydrography of the greatest lake-system of the globe, adds to the giant mountains of geography the stately and snow-clad Ruwenzori, whose rocky peak towers eighteen or nineteen thousand feet above sea-level, and to the lakes the Albert Edward Nyanza, whence issues the mysterious stream which fertilizes Egypt and makes the valley of the Nile the most marvellous seat of human culture, art and science.

In Stanley’s Story the reader has presented a most thrilling narrative of the terrible experiences encountered, as well as a graphic account of these wonderful discoveries and the amazing achievements accomplished by Mr. Stanley during his career in Africa. The subject—one of unparalleled interest—is presented in the characteristic style of the writer, from thoroughly reliable information, data, and the official reports of Mr. Stanley himself. It favorably commends itself to every lover of geographical science, as well as to the admirer of the marvellous in life and nature. It has been prepared in a popular form, and at a price much lower than books of like character and value, and very much lower than others which claim to give the story of Stanley in Africa, but are simply compilations from the writings of the different explorers who have in times past essayed to traverse its vast interior, and failed. Stanley, however, has not failed. Fate has decreed otherwise. His story has been told. It is the only authentic story, as recorded in these pages, and the reader will find it not only interesting but highly entertaining and thoroughly instructive throughout.

The Publishers.

[vii]

| CHAPTER I. | |

| INTRODUCTORY. | |

| A BRIEF ACCOUNT OF AFRICA — ITS ANCIENT CIVILIZATION — LITTLE INFORMATION EXTANT IN RELATION TO LARGE PORTIONS OF THE CONTINENT — THE GREAT FIELD OF SCIENTIFIC EXPLORATION AND MISSIONARY LABOR — ACCOUNT OF A NUMBER OF EXPLORING EXPEDITIONS, INCLUDING THOSE OF MUNGO PARK, DENHAM AND CLAPPERTON, AND OTHERS — THEIR PRACTICAL RESULTS — DESIRE OF FURTHER INFORMATION INCREASED — RECENT EXPLORATIONS, NOTABLY THOSE OF DR. LIVINGSTONE AND MR. STANLEY, REPRESENTING THE NEW YORK “HERALD” NEWSPAPER | 17 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| GEOLOGY OF AFRICA—ANTIQUITY OF MAN. | |

| THE GENERAL GEOLOGICAL FORMATION OF THE CONTINENT — THE WANT OF COMPREHENSIVE INVESTIGATION — SINGULAR FACTS AS TO THE DESERT OF SAHARA — THE QUESTION OF THE ANTIQUITY OF MAN — IS AFRICA THE BIRTHPLACE OF THE HUMAN RACE? — OPINIONS OF SCIENTISTS TENDING TO ANSWER IN THE AFFIRMATIVE — DARWINISM | 28 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| THE RESULTS OF THE EXPLORATIONS IN AFRICA. | |

| THE RESULT IN BEHALF OF SCIENCE, RELIGION AND HUMANITY OF THE EXPLORATIONS AND MISSIONARY LABORS OF DR. LIVINGSTONE AND OTHERS IN AFRICA — REVIEW OF RECENT DISCOVERIES IN RESPECT TO THE PEOPLE AND THE PHYSICAL NATURE OF THE AFRICAN CONTINENT — THE DIAMOND FIELDS OF SOUTH AFRICA — BIRD’S-EYE VIEW OF THE CONTINENT — ITS CAPABILITIES AND ITS WANTS — CHRISTIANITY AND MODERN JOURNALISM DISSIPATING OLD BARBARISMS, AND LEADING THE WAY TO TRIUMPHS OF CIVILIZATION | 47 |

| CHAPTER IV.[viii] | |

| LIVINGSTONE’S SECOND (AND LAST) EXPEDITION TO AFRICA. | |

| AGAIN LEAVES ENGLAND, MARCH, 1858 — RESIGNING HIS POSITION AS MISSIONARY FOR THE LONDON SOCIETY, HE IS APPOINTED BY THE BRITISH GOVERNMENT CONSUL AT KILIMANE — AFTER A BRIEF EXPLORATION ALONG THE ZAMBESI, HE AGAIN VISITS ENGLAND — SAILS ON HIS FINAL EXPEDITION, AUGUST 14, 1865, AND PROCEEDS BY WAY OF BOMBAY TO ZANZIBAR — REPORT OF HIS MURDER ON THE SHORES OF NYASSA | 70 |

| CHAPTER V. | |

| THE “HERALD” EXPEDITION OF SEARCH. | |

| THE GREAT DEVELOPMENT OF MODERN JOURNALISM — THE TELEGRAPH — JAMES GORDON BENNETT, HORACE GREELEY, HENRY J. RAYMOND — THE MAGNITUDE OF AMERICAN JOURNALISTIC ENTERPRISE — THE “HERALD” SPECIAL SEARCH EXPEDITION FOR DR. LIVINGSTONE — STANLEY A CORRESPONDENT — THE EXPEDITION ON ITS WAY TOWARD LIVINGSTONE | 82 |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

| HENRY MORLAND STANLEY. | |

| HIS NATIVITY — EARLY LIFE — COMES TO AMERICA — HIS ADOPTION BY A NEW ORLEANS MERCHANT — HIS CAREER DURING THE CIVIL WAR — BECOMES A CORRESPONDENT OF THE NEW YORK “HERALD” — SAILS FOR THE ISLAND OF CRETE TO ENLIST IN THE CAUSE OF THE CRETANS, THEN AT WAR — BUT CHANGES HIS MIND ON ARRIVING THERE — INSTEAD UNDERTAKES A JOURNEY THROUGH ASIA MINOR, THE PROVINCES OF RUSSIAN ASIA, ETC. — ATTACKED AND PLUNDERED BY TURKISH BRIGANDS — RELIEVED BY HON. E. JOY MORRIS, THE AMERICAN MINISTER — GOES TO EGYPT — TO ABYSSINIA — REMARKABLE SUCCESS THERE — HIS SUDDEN CALL TO PARIS FROM MADRID BY MR. BENNETT, OF THE “HERALD” — ACCOUNT OF THE INTERVIEW — MR. STANLEY GOES TO FIND LIVINGSTONE IN COMMAND OF THE “HERALD” LIVINGSTONE EXPEDITION | 95 |

| CHAPTER VII. | |

| MR. STANLEY IN AFRICA. | |

| THE SEARCH FOR DR. LIVINGSTONE ENERGETICALLY BEGUN — PROGRESS DELAYED BY WARS — THE SUCCESSFUL JOURNEY FROM UNYANYEMBE TO UJIJI IN 1871 — THE “HERALD” CABLE TELEGRAM ANNOUNCING THE SAFETY OF LIVINGSTONE — THE BATTLES AND INCIDENTS OF THIS NEWSPAPER CAMPAIGN — RECEIPT OF THE GREAT NEWS — THE HONOR BESTOWED ON AMERICAN JOURNALISM | 107 |

| CHAPTER VIII.[ix] | |

| THE MEETING OF LIVINGSTONE AND STANLEY. | |

| THE “LAND OF THE MOON” — DESCRIPTION OF THE COUNTRY AND THE PEOPLE — HORRID SAVAGE RITES — JOURNEY FROM UNYANYEMBE TO UJIJI — A WONDERFUL COUNTRY — A MIGHTY RIVER SPANNED BY A BRIDGE OF GRASS — OUTWITTING THE SPOILERS — STANLEY’S ENTRY INTO UJIJI, AND MEETING WITH LIVINGSTONE — THE GREAT TRIUMPH OF AN AMERICAN NEWSPAPER | 123 |

| CHAPTER IX. | |

| LIVINGSTONE AND STANLEY IN AFRICA. | |

| THE GREAT EXPLORER AS A COMPANION — HIS MISSIONARY LABORS — THE STORY OF HIS LATEST EXPLORATIONS — THE PROBABLE SOURCES OF THE NILE — GREAT LAKES AND RIVERS — THE COUNTRY AND PEOPLE OF CENTRAL AFRICA — A RACE OF AFRICAN AMAZONS — THE SLAVE TRADE — A HORRID MASSACRE — THE DISCOVERER PLUNDERED | 159 |

| CHAPTER X. | |

| LIVINGSTONE AND STANLEY IN AFRICA. [CONTINUED.] |

|

| AN EXPLORATION OF TANGANYIKA LAKE — RESULT — CHRISTMAS AT UJIJI — LIVINGSTONE PROCEEDS WITH STANLEY TO UNYANYEMBE — ACCOUNT OF THE JOURNEY — ALLEGED NEGLECT OF LIVINGSTONE BY THE BRITISH CONSULATE AT ZANZIBAR — DEPARTURE OF THE EXPLORER FOR THE INTERIOR, AND OF MR. STANLEY FOR EUROPE | 191 |

| CHAPTER XI. | |

| INTELLIGENCE OF THE SUCCESS OF THE “HERALD” ENTERPRISE. | |

| MR. STANLEY’S DESPATCHES TO THE “HERALD” — THEY CREATE A PROFOUND SENSATION — THE QUESTION OF THE AUTHENTICITY OF HIS REPORTS — CONCLUSIVE PROOF THEREOF — TESTIMONY OF THE ENGLISH PRESS, JOHN LIVINGSTONE, EARL GRANVILLE, AND THE QUEEN OF ENGLAND HERSELF — MR. STANLEY’S RECEPTION IN EUROPE — AT PARIS — IN LONDON — THE BRIGHTON BANQUET — HONORS FROM THE QUEEN | 199 |

| CHAPTER XII.[x] | |

| DR. LIVINGSTONE STILL IN AFRICA. | |

| THE GREAT EXPLORER STILL IN SEARCH OF THE SOURCES OF THE NILE — HIS LETTERS TO THE ENGLISH GOVERNMENT ON HIS EXPLORATIONS — CORRESPONDENCE WITH LORD STANLEY, LORD CLARENDON, EARL GRANVILLE, DR. KIRK AND JAMES GORDON BENNETT, JR. — HIS OWN DESCRIPTION OF CENTRAL AFRICA AND THE SUPPOSED SOURCES OF THE NILE — THE COUNTRY AND PEOPLE — A NATION OF CANNIBALS — BEAUTIFUL WOMEN — GORILLAS — THE EXPLORER’S PLANS FOR THE FUTURE | 211 |

| CHAPTER XIII. | |

| THE SLAVE TRADE OF EAST AFRICA. | |

| DR. LIVINGSTONE’S LETTER UPON THE SUBJECT TO MR. BENNETT — COMPARES THE SLAVE TRADE WITH PIRACY ON THE HIGH SEAS — NATIVES OF INTERIOR AFRICA AVERAGE SPECIMENS OF HUMANITY — SLAVE TRADE CRUELTIES — DEATHS FROM BROKEN HEARTS — THE NEED OF CHRISTIAN CIVILIZATION — BRITISH CULPABILITY | 238 |

| CHAPTER XIV. | |

| THE ANIMAL KINGDOM OF AFRICA. | |

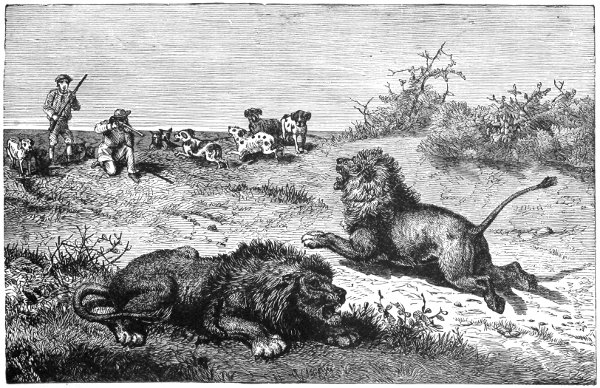

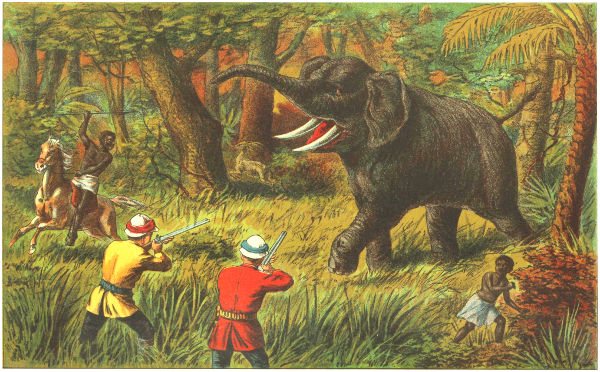

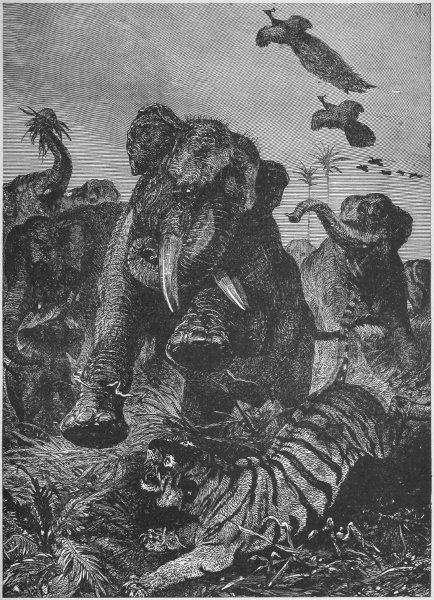

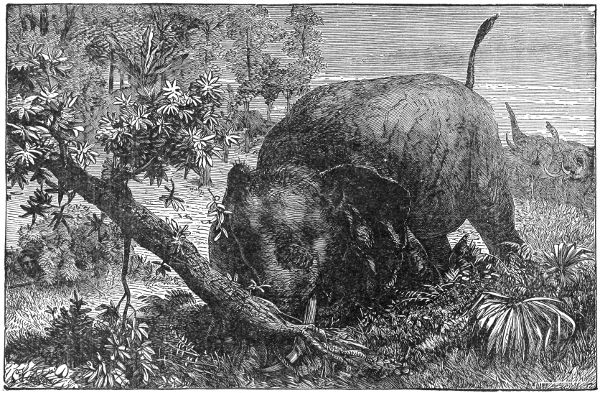

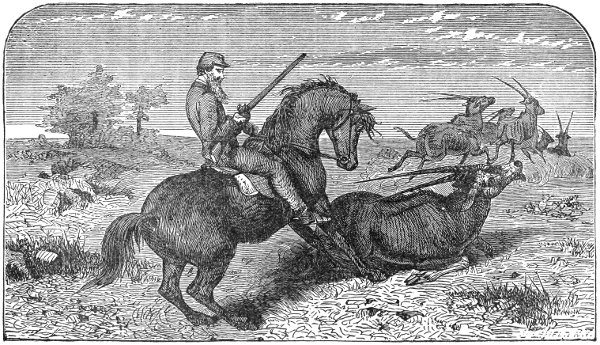

| SOME ACCOUNTS OF THE BEASTS, BIRDS, REPTILES AND INSECTS OF AFRICA — LIVINGSTONE’S OPINION OF THE LION — ELEPHANTS, HIPPOPOTAMI, RHINOCEROSES, Etc. — WILD ANIMALS SUBJECT TO DISEASE — REMARKABLE HUNTING EXPLORATIONS — CUMMING SLAYS MORE THAN ONE HUNDRED ELEPHANTS — DU CHAILLU AND THE GORILLA — THRILLING INCIDENTS — VAST PLAINS COVERED WITH GAME — FORESTS FILLED WITH BIRDS — IMMENSE SERPENTS — THE PYTHON OF SOUTH AFRICA — ANTS AND OTHER INSECTS | 248 |

| CHAPTER XV. | |

| THE LAST JOURNEY AND THE DEATH OF DR. LIVINGSTONE. | |

| DR. LIVINGSTONE ANXIOUSLY AWAITS THE RECRUITS AND SUPPLIES SENT BY MR. STANLEY — ON THEIR ARRIVAL SETS OUT SOUTHWESTWARD ON HIS LAST JOURNEY — REACHES KISERI, WHERE CHRONIC DYSENTERY SEIZES HIM — HE REFUSES TO YIELD; BUT PUSHES ON, TILL INCREASING DEBILITY COMPELS HIM TO STOP AND RETRACE HIS STEPS — HE SINKS RAPIDLY, AND ON MAY 4TH BREATHES HIS LAST — HIS ATTENDANTS TAKE NECESSARY PRECAUTIONS TO INSURE THE RETURN OF THE CORPSE TO ENGLAND — LETTER FROM MR. HOLMWOOD, ATTACHÉ OF THE BRITISH CONSULATE AT ZANZIBAR | 281 |

| CHAPTER XVI.[xi] | |

| THE CORPSE BORNE TO ENGLAND, AND LAID IN WESTMINSTER ABBEY. | |

| THE BODY OF DR. LIVINGSTONE BORNE TO UNYANYEMBE BY HIS ATTENDANTS, AND THENCE TO ZANZIBAR — THE BRITISH CONSUL-GENERAL SENDS IT, WITH THE DOCTOR’S PAPERS, BOOKS, Etc., TO ENGLAND — ARRIVAL AT SOUTHAMPTON AND AT LONDON — THE PEOPLE VIE IN TRIBUTES OF RESPECT — THE FUNERAL — THE GRAVE IN WESTMINSTER ABBEY | 289 |

| CHAPTER XVII. | |

| FURTHER DETAILS OF THE DEATH OF LIVINGSTONE. | |

| THE LAST NIGHT — EXPIRES IN THE ACT OF PRAYING — COUNCIL OF THE MEN — NOBLE CONDUCT OF CHITAMBO — THE PREPARATION OF THE CORPSE — HONOR SHOWN TO DR. LIVINGSTONE — INTERMENT OF THE HEART AT CHITAMBO’S — HOMEWARD MARCH FROM ILALA — ILLNESS OF ALL THE MEN — DEATHS — THE LUAPULU — REACH TANGANYIKA — LEAVE THE LAKE — CROSS THE LAMBALAMFIPA RANGE — IMMENSE HERDS OF GAME — NEWS OF EAST COAST SEARCH EXPEDITION — CONFIRMATION OF NEWS — AVANT-COURIERS SENT FORWARD TO UNYANYEMBE — CHUMA MEETS LIEUT. CAMERON — SAD DEATH OF DR. DILLON — THE BODY EFFECTUALLY CONCEALED — ARRIVAL ON THE COAST | 298 |

| CHAPTER XVIII. | |

| THE ANGLO-AMERICAN EXPEDITION. | |

| HENRY M. STANLEY’S NEW MISSION — THE UNFINISHED TASK OF LIVINGSTONE — THE COMMISSION OF MR. STANLEY BY THE “DAILY TELEGRAPH,” OF LONDON, AND THE NEW YORK “HERALD,” TO COMMAND THE NEW EXPEDITION TO CENTRAL AFRICA — MR. STANLEY’S ARRIVAL AT ZANZIBAR — FITTING OUT HIS EXPEDITION AND ENLISTING MANY OF HIS OLD CAPTAINS AND CHIEFS — SETS SAIL FOR THE WEST COAST OF THE ZANZIBAR SEA AND TOWARDS THE DARK CONTINENT — ARRIVAL AT BAGAMOYO — COMPLETES HIS FORCES AND TAKES UP HIS LINE OF MARCH INLAND — INCIDENTS ATTENDING HIS MARCH TO MPWAPWA | 351 |

| CHAPTER XIX.[xii] | |

| STANLEY’S ROUTE TO VICTORIA NYANZA. | |

| SPENDS CHRISTMAS AT ZINGEH — THE RAINY SEASON SETS IN — FAMINE OR SCARCITY OF FOOD — HALF RATIONS — EXTORTIONATE CHIEFS LEVY BLACKMAIL — ARRIVAL AT JIWENI — THROUGH JUNGLE TO KITALALO — THE PLAIN OF SALINA — “NOT A DROP OF WATER” — BELLICOSE NATIVES — TROUBLE WITH MANY OF HIS FOLLOWERS — VALUABLE SERVICES RENDERED HIM BY FRANK AND EDWARD POCOCK AND FREDERICK BARKER — FREQUENT QUARRELS — THE TRIALS OF STANLEY — CAMP AT MTIWI — TERRIBLE RAIN STORM AND SAD PLIGHT OF STANLEY AND HIS PEOPLE — MISLED BY HIS GUIDE, IS LOST IN A WILD OF LOW SCRUB AND BRUSH — TERRIBLE EXPERIENCES — STARVATION IMPENDING — SENDS FOR RELIEF TO SUNA IN URIMI — THE WELCOME MEAL OF OATMEAL — A SINGULAR COOKING UTENSIL — DEATH OF EDWARD POCOCK — THE WEARY MARCH FROM THE WARIMI TO MGONGO TEMBE — THE BEAUTIFUL USIHA — REACHES VICTORIA NYANZA FEBRUARY 27TH, 1875 — ENTERS KAGEHYI — RECEIVES ITS HOSPITALITIES — THE END OF A JOURNEY OF 720 MILES IN 103 DAYS | 360 |

| CHAPTER XX. | |

| EXPLORATION OF VICTORIA NYANZA. | |

| PREPARING THE LADY ALICE FOR SEA — SELECTS HIS CREW — THE START FOR THE CIRCUMNAVIGATION OF LAKE VICTORIA — AFLOAT ON THE LAKE — A NIGHT AT UVUMA — BARMECIDE FARE — MESSAGE FROM MTESA — CAMP ON SOWEH ISLAND — AN EXTRAORDINARY MONARCH — MTESA, EMPEROR OF UGANDA — ARRIVAL AT THE IMPERIAL CAPITAL — GLOWING DESCRIPTION OF THE COUNTRY — A GRAND MISSION FIELD — THE TREACHERY OF BUMBIREH — SAVED — REFUGE ISLAND — RETURN TO CAMP AT KAGEHYI | 372 |

| CHAPTER XXI. | |

| RETURNS TO UGANDA. | |

| LEAVES KAGEHYI WITH HALF HIS EXPEDITION — ARRIVAL AT REFUGE ISLAND — BRINGS UP THE REST — ENCAMPED ON REFUGE ISLAND — INTERVIEWED BY IROBA CANOES — STANLEY’S FRIENDSHIP SCORNED — THE KING OF BUMBIREH HELD AS A HOSTAGE — THE MASSACRE OF KYTAWA CHIEF AND HIS CREW — THE PUNISHMENT OF THE MURDERERS — ITS SALUTARY EFFECT UPON THEIR NEIGHBORS — ARRIVAL IN UGANDA — LIFE AND MANNERS IN UGANDA — THE EMPEROR — THE LAND — EN ROUTE FOR MUTA NZIGÉ — THE WHITE PEOPLE OF GAMBARAGARA — LAKE WINDERMERE — RUMANIKA, THE KING OF KARAGWÉ — HIS COUNTRY — THE INGEZI — THE HOT SPRINGS OF MTAGATA — UBAGWÉ — MSENÉ — ACROSS THE MALAGARAZI TO UJIJI — SAD REFLECTIONS | 389 |

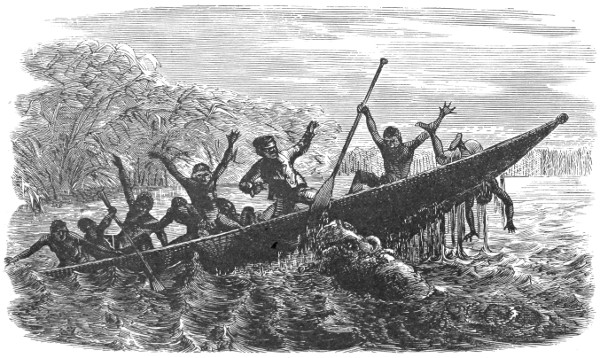

| CHAPTER XXII.[xiii] | |

| WESTWARD ALONG THE CONGO TO THE ATLANTIC. | |

| SURVEYS LAKE TANGANYIKA — SETTLES THE QUESTION OF THE RIVER LUGUKA — AN OUTBREAK OF SMALL-POX AND FEVER IN UJIJI — CAUSES STANLEY TO DEPART — PUSHES HIS WAY ALONG THE RIGHT BANK OF THE LUALALA TO THE NYANGWE — OVERLAND THROUGH UREGGA — BROUGHT TO A STANDSTILL BY AN IMPENETRABLE FOREST — CROSSES OVER TO THE LEFT BANK — NORTHEAST USKUSA — DENSE JUNGLES — OPPOSED AND HARASSED BY HOSTILE SAVAGES — ASSAILED NIGHT AND DAY — THE PROGRESS OF THE EXPEDITION ALMOST HOPELESS — DESERTED BY FORTY OF HIS PORTERS — TAKES TO THE RIVER AS THE ONLY CHANCE TO ESCAPE — PASS THE CATARACTS BY CUTTING A ROAD THROUGH THIRTEEN MILES OF DENSE FOREST FOR THE PASSAGE OF THE LADY ALICE AND THE CANOES — ALMOST INCESSANTLY FIGHTING THE SAVAGES — THREATENED WITH STARVATION — THREE DAYS WITHOUT FOOD — MEET WITH A FRIENDLY TRIBE WITH WHOM THEY BARTER FOR SUPPLIES — MANY FALLS AND FURIOUS RAPIDS — AGAIN ATTACKED BY A MORE WARLIKE TRIBE, ARMED WITH FIREARMS — ALMOST STARVED AND WORN-OUT WITH FATIGUE, REACHES ISANGILA — LEAVES THE RIVER — TERRIBLE SUFFERINGS OF HIS PEOPLE — RELIEF FROM EMBOMMA — REACH EMBOMMA — KABINDA AND LONDA — SAIL FOR CAPE OF GOOD HOPE — THENCE RETURN BY STEAMER TO ZANZIBAR — CLOSE OF THE EXPEDITION | 404 |

| CHAPTER XXIII. | |

| THE WONDERFUL RESOURCES OF THE CONGO. | |

| THE MESSENGERS OF KING LEOPOLD II., OF BELGIUM — MEET STANLEY AT MARSEILLES, FRANCE — OBJECT OF THE INTERVIEW — ANOTHER EXPEDITION TO AFRICA, TO EXPLORE THE CONGO, IN THE INTERESTS OF COMMERCE — THE COMITÉ D’ETUDES DU HAUT CONGO — OBJECT OF THE EXPEDITION DEFINED — STANLEY RETURNS TO AFRICA — ARRIVAL AT THE MOUTH OF THE CONGO — COMMERCIAL POSSIBILITIES OF THE CONGO BASIN — RAILWAYS NECESSARY — THE POPULATION — STATISTICS OF TRADE — PRODUCTS OF THE IMMENSE FORESTS — MARVELLOUS BEAUTY OF THE COUNTRY — VEGETABLE PRODUCTS — PALMS — INDIA-RUBBER PLANTS — THE ORCHILLA — REDWOOD POWDER — VEGETABLE FIBRES — SKINS OF ANIMALS — IVORY — THE CLIMATE — IMPORTANCE OF THE EXPEDITION, BOTH COMMERCIALLY AND POLITICALLY — RETURN OF STANLEY TO ENGLAND | 420 |

| CHAPTER XXIV.[xiv] | |

| FOUNDING OF THE FREE CONGO STATE. | |

| THE INTERNATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF THE CONGO SEEKS RECOGNITION FROM FOREIGN POWERS — TREATY BETWEEN ENGLAND AND PORTUGAL — EARL GRANVILLE — CLAIMS OF PORTUGAL — CONCESSION OF ENGLAND — KING LEOPOLD OBTAINS THE ASSISTANCE OF THE GERMAN CHANCELLOR AND THE SYMPATHIES OF THE FRENCH REPUBLIC — PRINCE BISMARCK PROTESTS — LETTER TO BARON DE COURCEL, FRENCH AMBASSADOR AT BERLIN — THE BARON’S REPLY — FRANCE AND GERMANY IN ACCORD — CALL FOR A CONFERENCE OF THE POWERS AT BERLIN — THE CONFERENCE ASSEMBLES — PRINCE BISMARCK OPENS THE CONFERENCE WITH AN ADDRESS STATING ITS OBJECT — MR. STANLEY A DELEGATE — ASKED TO GIVE HIS VIEWS — MR. STANLEY’S SUGGESTIONS — DELIBERATIONS OF THE CONFERENCE — RESULTS OF THE CONFERENCE — PROTOCOL SIGNED BY ALL THE PLENIPOTENTIARIES — THE UNITED STATES THE FIRST TO PUBLICLY RECOGNIZE THE FLAG OF THE FREE CONGO STATE — HONORS TO MR. STANLEY IN GERMANY | 431 |

| CHAPTER XXV. | |

| EMIN PASHA, GOVERNOR OF THE SOUDANESE PROVINCES. | |

| SKETCH OF HIS EARLY LIFE — HIS REAL NAME — A SILESIAN BY BIRTH — STUDENT AT THE UNIVERSITY OF BRESLAU — BECOMES A PHYSICIAN — GOES TO TURKEY, AND THENCE TO ANTIVARI AND SCUTARI — ATTACHED TO THE COURT OF VALIS ISMAEL PASHA HAGGI — RETURNS HOME 1873 — IN 1875 GOES TO EGYPT — ENTERS THE EGYPTIAN SERVICE AS “DR. EMIN EFFENDI” — MEETS WITH GENERAL GORDON — RECEIVES THE POST OF COMMANDER OF LADO, TOGETHER WITH THE GOVERNMENT OF THE EQUATORIAL PROVINCE — DEATH OF GENERAL GORDON AND RETREAT OF LORD WOLSELEY’S ARMY — BECOMES DEPENDENT UPON HIS OWN RESOURCES AFTER ALL COMMUNICATION WITH THE EGYPTIAN GOVERNMENT IS CUT OFF — ENCOMPASSED BY HOSTILE TRIBES, IS LOST TO THE REST OF THE WORLD — A RESUME OF WHAT HE EFFECTED IN HIS ADMINISTRATION OF PUBLIC AFFAIRS — HIS DIARY — EXTRACTS SENT TO FRIENDS — INSURRECTION, AND INVASION OF THE PROVINCE BY THE MAHDI’S FORCES — HIS POSITION VERY CRITICAL — EXCITES THE SYMPATHY OF THE WHOLE WORLD | 446 |

| CHAPTER XXVI.[xv] | |

| THE EMIN BEY RELIEF EXPEDITION. | |

| PUBLIC OPINION IN ENGLAND — A RELIEF COMMITTEE ORGANIZED — SUBSCRIPTION OF FUNDS TO DEFRAY THE EXPENSES OF AN EXPEDITION — HENRY M. STANLEY CALLED TO ENGLAND BY CABLE — ACCEPTS COMMAND OF THE RELIEF EXPEDITION — STANLEY’S OPINION AS TO THE CHARACTER OF THE EXPEDITION AND THE BEST ROUTE — REACHES ZANZIBAR — MEETS TIPPU-TIB — SUPPLIED WITH 600 CARRIERS — CONSENTS TO ACCOMPANY STANLEY — SAILS FOR THE MOUTH OF THE CONGO FEBRUARY 25TH — REACHES THE ARUWIMI IN JUNE — LEAVES A REARGUARD AT YAMBUYA — ADVANCES TOWARDS ALBERT NYANZA ALONG THE VALLEY OF THE ARUWIMI — STARTLING RUMORS — STANLEY AND EMIN REPORTED TO BE IN THE HANDS OF THE ARABS — A LETTER IN PROOF RECEIVED FROM A MAHDIST OFFICER IN THE SOUDAN — NEWS OF DISASTERS ON THE CONGO — MURDER OF DR. BARTTELOT — DEATH OF MR. JAMIESON — THE GLOOMY NEWS REGARDING STANLEY’S FATE — THE OPINION OF THOMSON, THE AFRICAN TRAVELLER — NEWS OF STANLEY’S ARRIVAL AT EMIN’S CAPITAL RECEIVED DECEMBER, 1888 — FIRST NEWS FROM STANLEY HIMSELF APRIL 3, 1889 — FULL ACCOUNT OF HIS MARCH, AND THE TERRIBLE EXPERIENCES SUFFERED, FROM YAMBUYA TO THE ALBERT NYANZA | 457 |

| CHAPTER XXVII. | |

| MEETING OF STANLEY AND EMIN PASHA. | |

| EMIN PASHA ARRIVES BY STEAMER, ACCOMPANIED BY CASATI AND MR. JEPHSON — MEETING WITH STANLEY — CAMP TOGETHER FOR TWENTY-SIX DAYS — STANLEY RETURNS TO FORT BODO — LEAVES JEPHSON WITH EMIN — RELIEVES CAPT. NELSON AND LIEUT. STAIRS — TERRIBLE LOSS SUFFERED BY LIEUT. STAIR’S PARTY — LEAVES FORT BODO FOR KILONGA-LONGA’S AND UGARROWWA — THE LATTER DESERTED — MEETS THE REAR COLUMN OF THE EXPEDITION A WEEK LATER AT BUNALYA — MEETS BONNY, AND LEARNS OF THE DEATH OF MAJOR BARTTELOT — TERRIBLE WRECK OF THE REAR COLUMN — SEVENTY-ONE OUT OF TWO HUNDRED AND FIFTY-SEVEN LEFT — THE RECORD ONE OF DISASTER, DESERTION AND DEATH — INTERVIEW WITH EMIN — EMIN’S CONDITION — EMIN AND JEPHSON SURROUNDED BY THE REBELS AND TAKEN PRISONERS — STANLEY’S RETURN A SECOND TIME TO ALBERT NYANZA — LETTER OF STANLEY GEOGRAPHICALLY DESCRIBING THE FOREST REGION TRAVERSED BY HIM — SKETCHES THE COURSE OF THE ARUWIMI — A RETROSPECT OF HIS THRILLING EXPERIENCES AS FAR AS THE VICTORIA NYANZA, AUGUST 28TH, 1889 | 481 |

| CHAPTER XXVIII.[xvi] | |

| GEOGRAPHICAL DISCOVERIES EN ROUTE. | |

| FINDS THAT BAKER HAS MADE AN ERROR — ALTITUDES OF LAKE ALBERT AND THE BLUE MOUNTAINS — VACOVIA — DISCOVERS THE LOFTY RUEVENZORI — THE NILE OR THE CONGO? — THE SEMLIKI RIVER — THE PLAINS OF NOONGORA — THE SALT LAKES OF KATIVE — NEW PEOPLES, WAKONYU OF THE GREAT MOUNTAINS — THE AWAMBA — WASONYORA — WANYORA BANDITS — LAKE ALBERT EDWARD — THE TRIBES AND SHEPHERD RACES OF THE EASTERN UPLANDS — WANYANKORI — WANYARUWAMBA — WAZINYA — A HARVEST OF NEW FACTS — THE IMPORTANCE OF STANLEY’S ADDITION TO THE VICTORIA NYANZA | 501 |

| CHAPTER XXIX. | |

| FROM THE ALBERT NYANZA TO THE INDIAN OCEAN. | |

| EMIN PASHA’S INDECISION — MUCH TIME WASTED — STANLEY GROWS IMPATIENT — JEPHSON’S REPORT — STANLEY DEMANDS POSITIVE ACTION, AND THREATENS TO MARCH HOMEWARD ON FEBRUARY 13TH — RECEIVES EMIN’S REPLY, ACCEPTING THE ESCORT, ON THE DAY HE HAD PROPOSED TO BEGIN HIS RETURN MARCH — STANLEY FURNISHES CARRIERS TO HELP HIM UP WITH HIS LUGGAGE — STANLEY GREATLY HINDERED BY THE SUSPICIONS OF THE NATIVES — CONVALESCENT FROM HIS RECENT SEVERE ILLNESS, STANLEY LEAVES KAVALLIS WITH HIS UNITED EXPEDITION, FOR THE INDIAN OCEAN, APRIL 12TH — LETTER OF LIEUT. W. G. STAIRS — REACHES URSULALA — STANLEY’S LETTER TO SIR FRANCIS DE WINSTON — EXPEDITIONS FITTED OUT AND FORWARDED TO THE INTERIOR TO MEET STANLEY — STANLEY REACHES MSUWAH NOVEMBER 29TH — MEETS THE “HERALD” COMMISSIONER — REACHES MBIKI DECEMBER 1ST — KIGIRO, DECEMBER 3D — BAGAMOYO, DECEMBER 4TH — ENTERS ZANZIBAR, DECEMBER 5TH — SAD ACCIDENT BEFALLS EMIN PASHA — SERIOUSLY, IF NOT FATALLY, INJURED — THE END OF A MOST REMARKABLE AND EXTRAORDINARY EXPEDITION — THE CLOSING WORDS OF STANLEY’S STORY | 508 |

[xvii]

| PAGE | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 0. | A Frontispiece—Stanley and Emin Bey | op. | title |

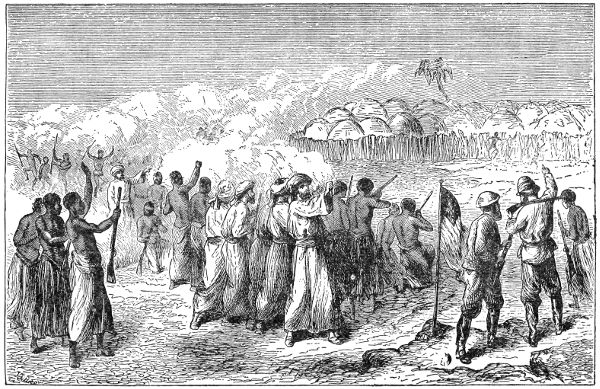

| 27. | A Camp of Arab Traders | „ | 68 |

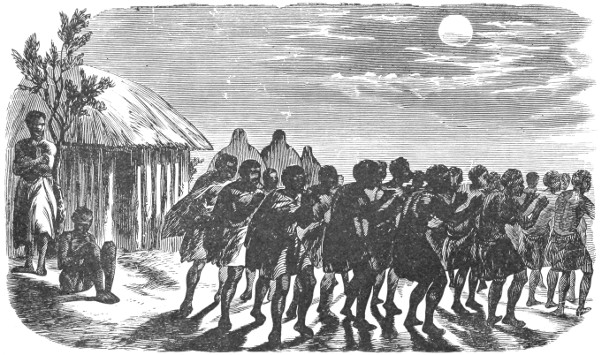

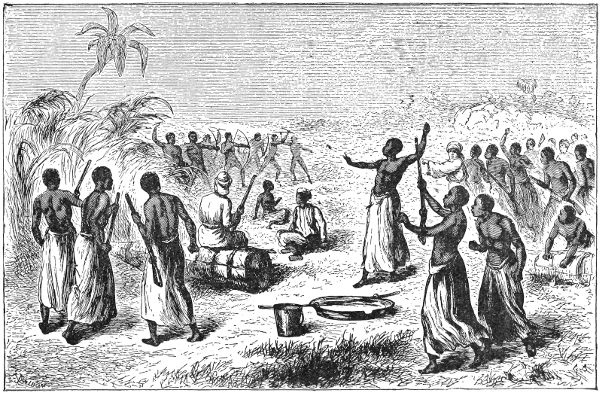

| 26. | A Dance by Torchlight | „ | 66 |

| 70. | Attacked by a Hippopotamus | „ | 252 |

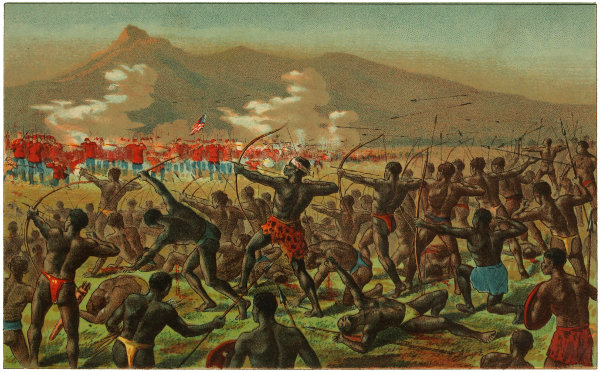

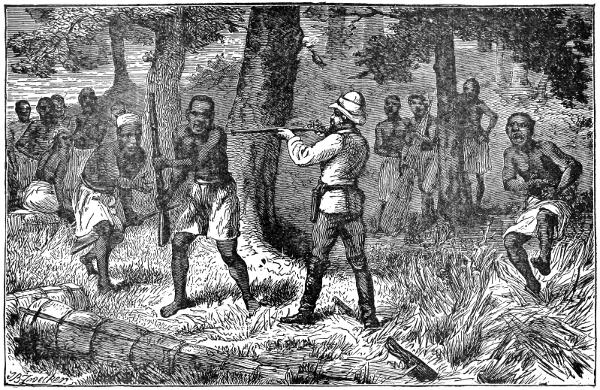

| 47. | A Fierce Battle with the Natives | „ | 132 |

| 53. | A Floating Alligator | „ | 150 |

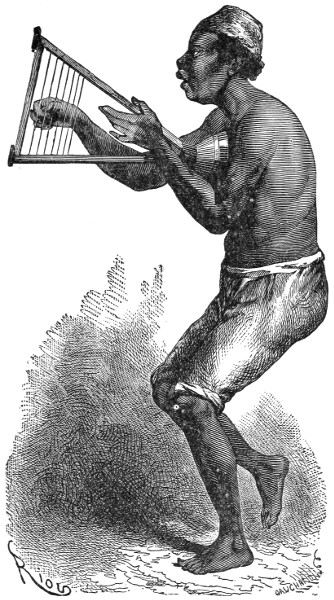

| 37. | African Musician | „ | 94 |

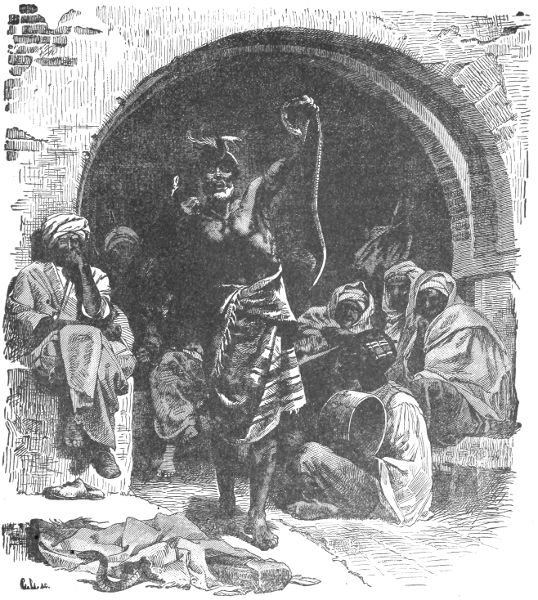

| 31. | An African Sun-Dance | „ | 76 |

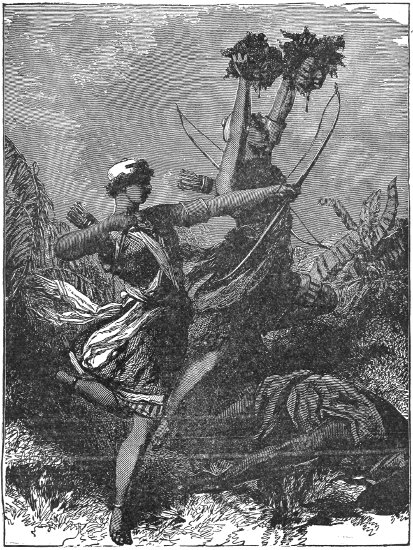

| 57. | Amazon Warriors | „ | 172 |

| 52. | An Unexpected Surprise | „ | 144 |

| 67. | An African Gazelle | „ | 236 |

| 49. | A Fine Covey of the Noble Game | „ | 138 |

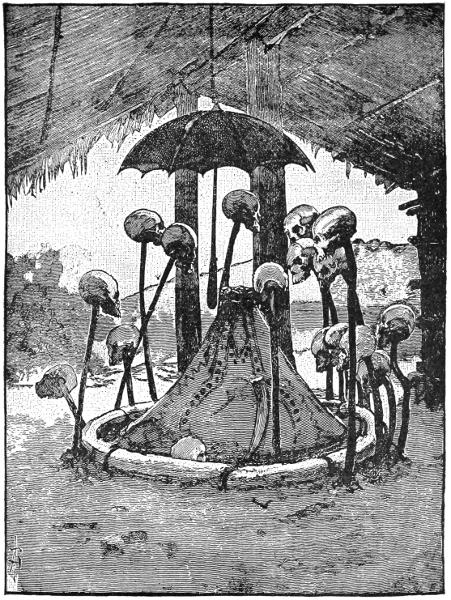

| 93. | A Ghastly Monument | „ | 358 |

| 16. | An Object of Intense Interest | „ | 36 |

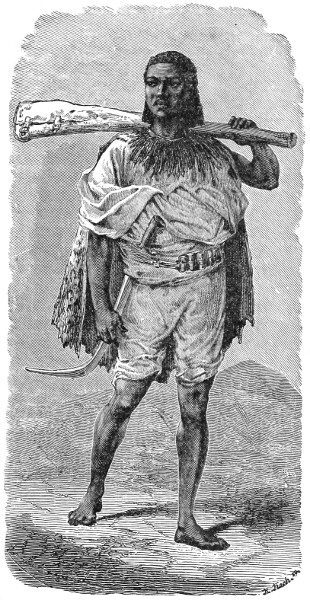

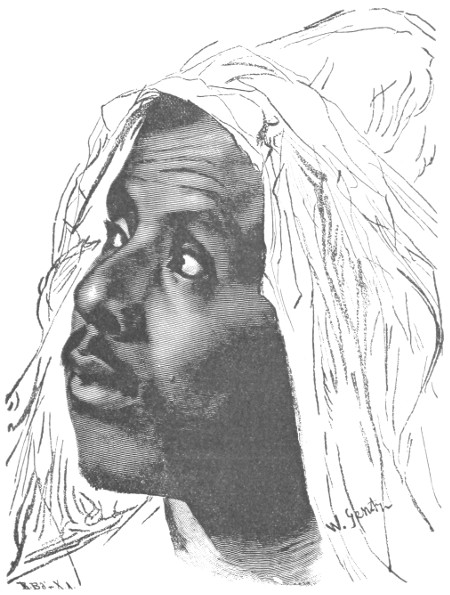

| 117. | A South African | „ | 456 |

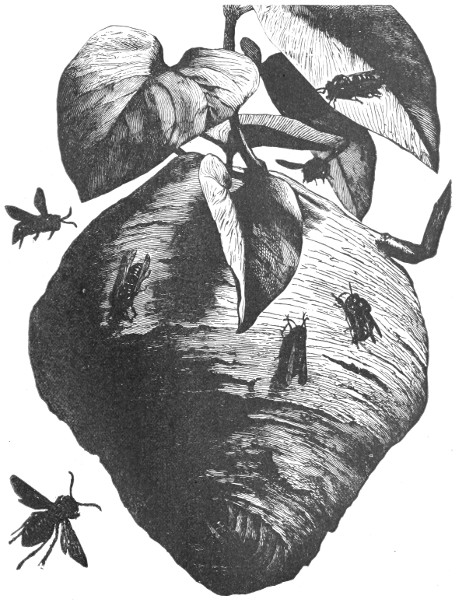

| 78. | A Terror of the Insect Kingdom | „ | 278 |

| 50. | African Warblers | „ | 140 |

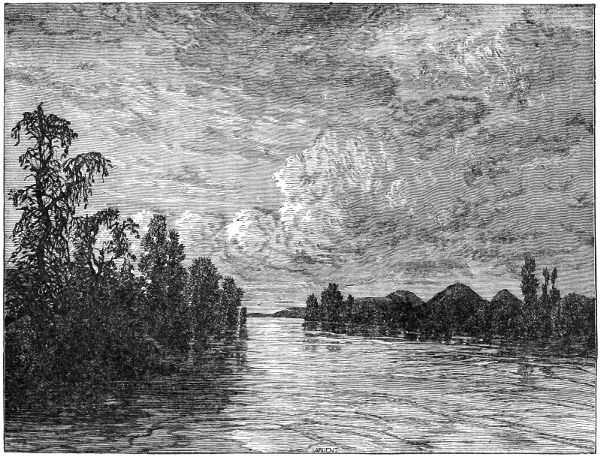

| 100. | A Shore Scene on Lake Windermere | „ | 398 |

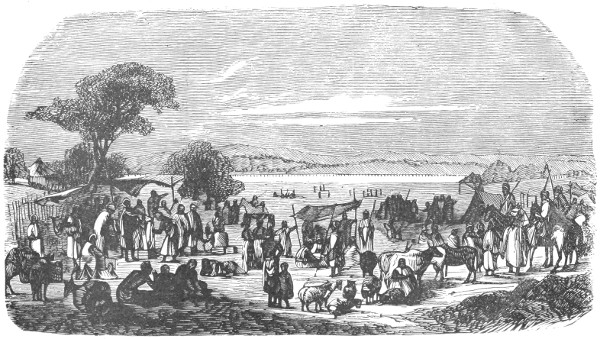

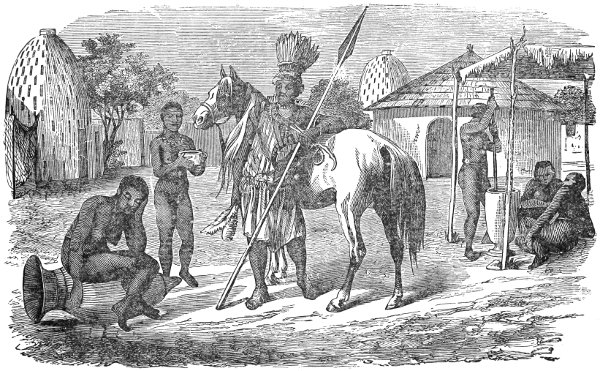

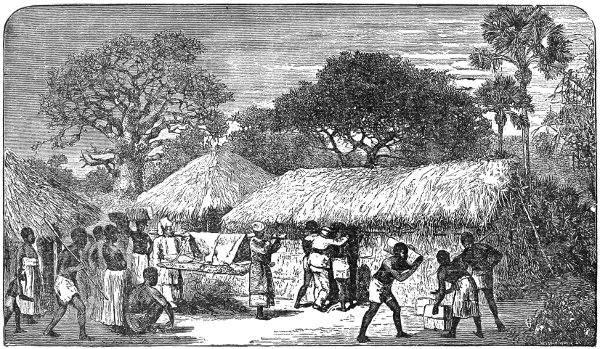

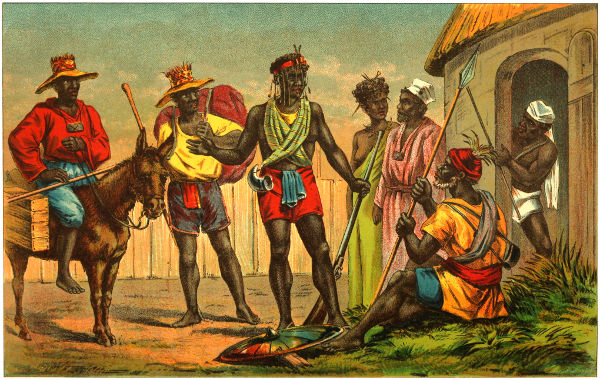

| 20. | A Street Scene in African Village | „ | 50 |

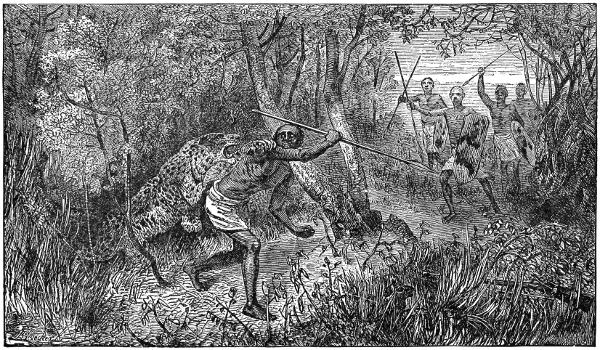

| 69. | A Surprise in the Jungle | „ | 250 |

| 82. | Allegorical | „ | 288 |

| 122. | Arabi Pasha and the Egyptian Soudanese | „ | 482 |

| 23. | A Narrow Escape | „ | 58 |

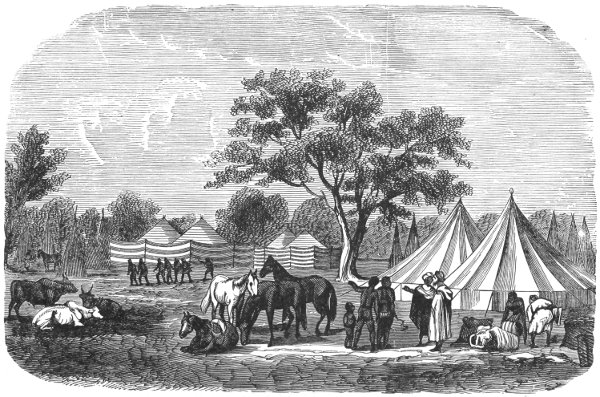

| 15. | Arrival of the Expedition on the Banks of the Zambesi | „ | 32 |

| 17. | Arab Slave Traders | „ | 40 |

| 59. | An African Belle | „ | 184 |

| 14. | Arab Chief of Central Africa | „ | 28 |

| 22. | A Stretch of the Nile | „ | 54 |

| 76. | African Snake Charmer[xviii] | „ | 274 |

| 21. | African Bird-Life | „ | 52 |

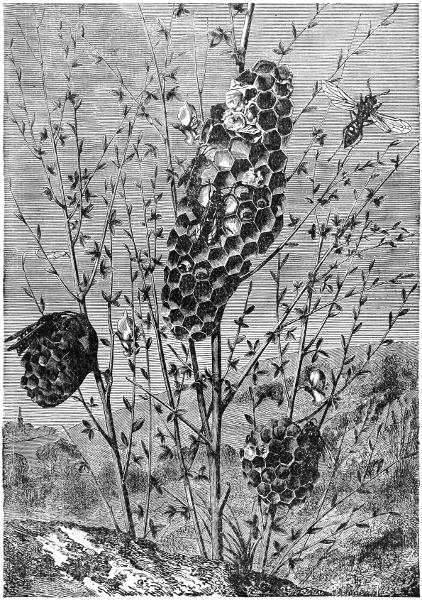

| 35. | A Remarkable Wasp-Nest found in Africa | „ | 84 |

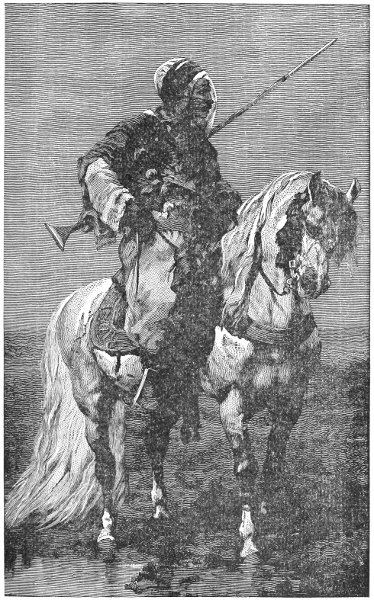

| 38. | An Arab Courier | „ | 96 |

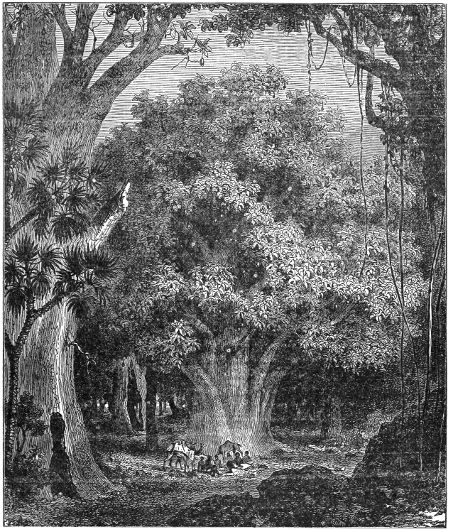

| 34. | A Baobab Tree | „ | 82 |

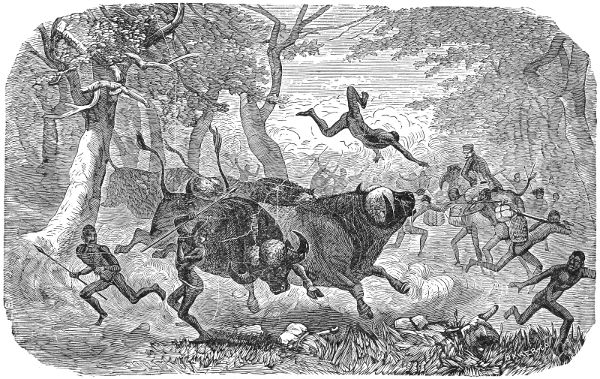

| 29. | Attacked by Buffaloes | „ | 70 |

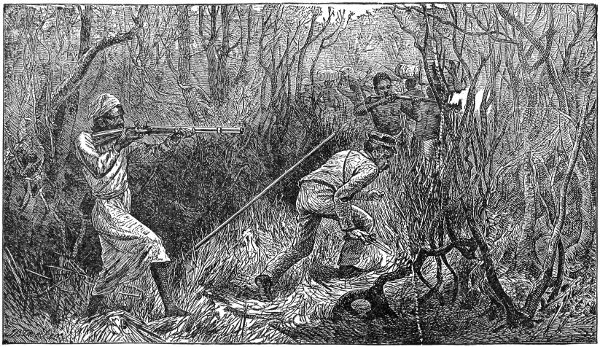

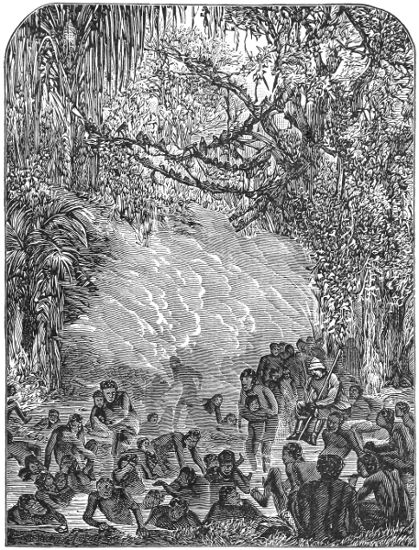

| 61. | Ambuscade by Manyuemas | „ | 188 |

| 95. | Allegorical | „ | 370 |

| 71. | A Jungle Scene in South Africa | „ | 254 |

| 68. | A Mightier Roar than that of the Forest King | „ | 248 |

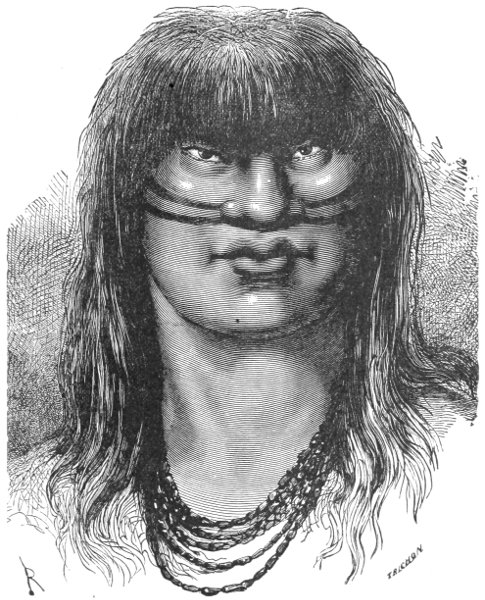

| 114. | A Nyambana | „ | 445 |

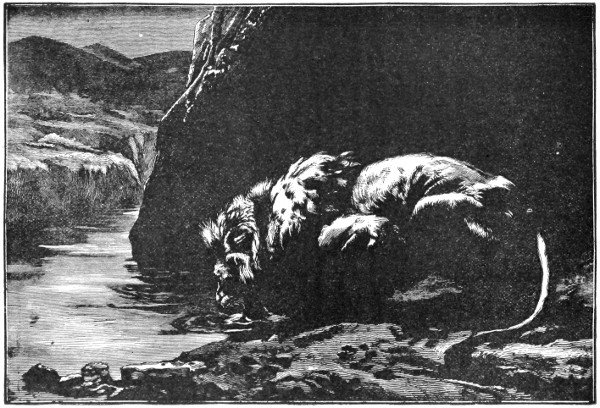

| 28. | African Lioness and her Young | „ | 68 |

| 113. | African Alligator | „ | 430 |

| 91. | An African Tailor | „ | 351 |

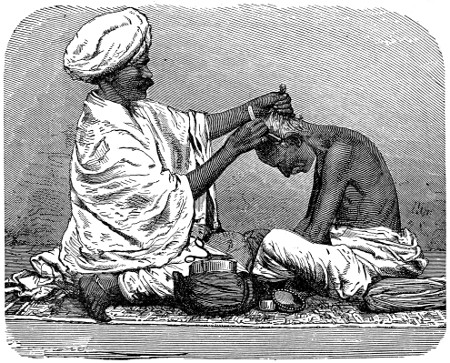

| 121. | An African Barber | „ | 481 |

| 102. | Allegorical | „ | 402 |

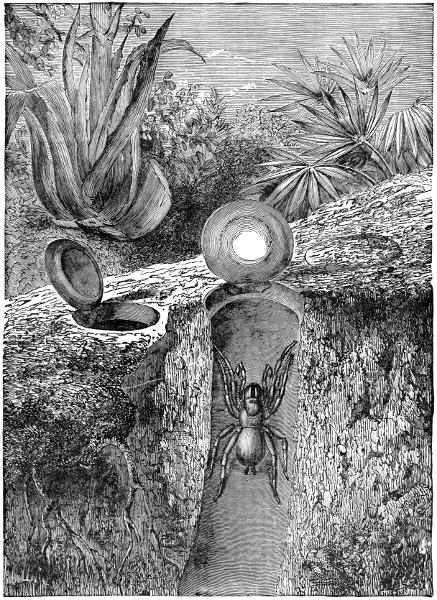

| 62. | Bashouay Ant | „ | 191 |

| 55. | Broad-Billed Duck of the Nile | „ | 159 |

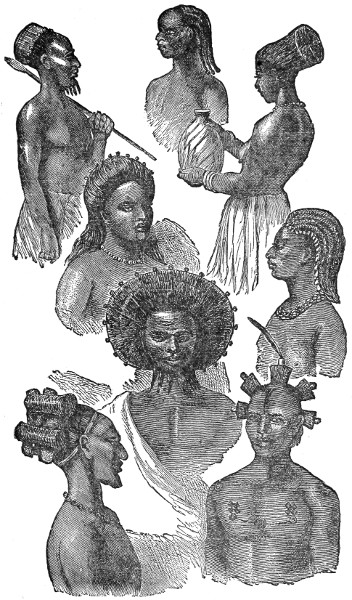

| 58. | Characteristic Head-Dresses | „ | 178 |

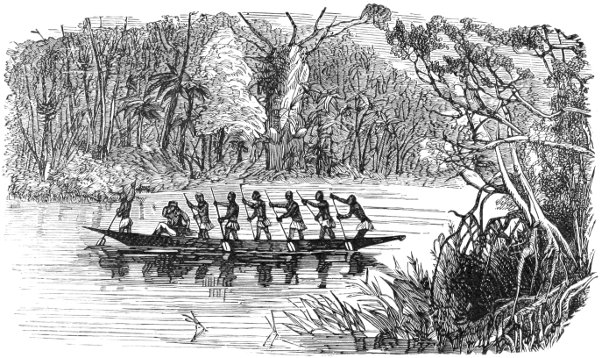

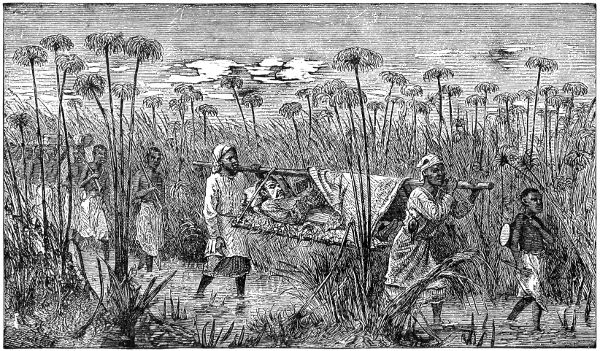

| 51. | Crossing a Lagoon | „ | 142 |

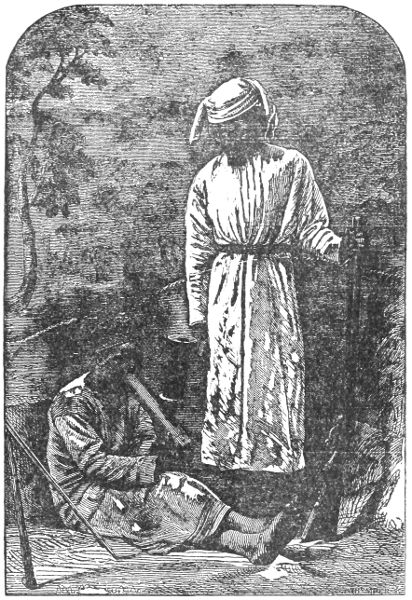

| 87. | Chuma and Susi, the Fast Friends of Livingstone | „ | 308 |

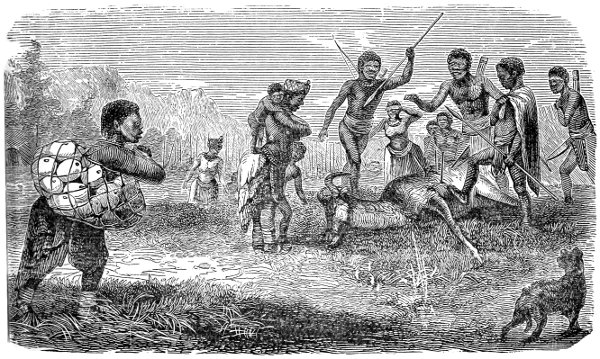

| 19. | Discussing the Feast of Game | „ | 48 |

| 12. | Dr. David Livingstone | „ | 22 |

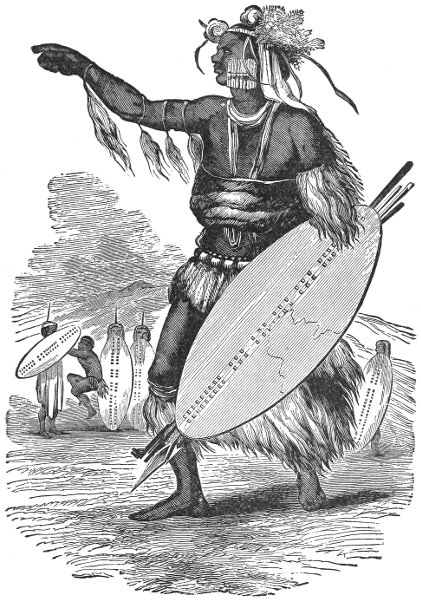

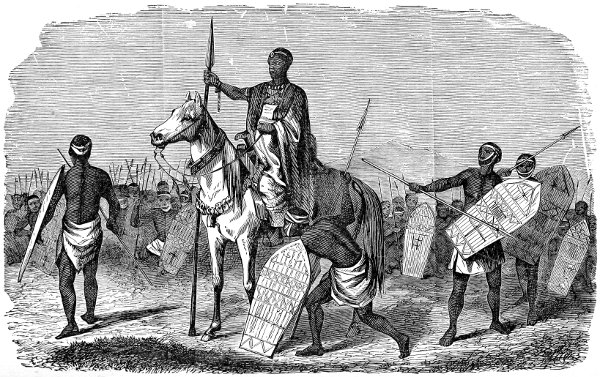

| 39. | Equipped for War | „ | 98 |

| Floating Island | „ | 214 | |

| 18. | Fleet-Footed Elk | „ | 45 |

| 89. | Hippopotamus in his Lair | „ | 338 |

| 65. | “I’ll Shoot You, if You Drop that Box” | „ | 212 |

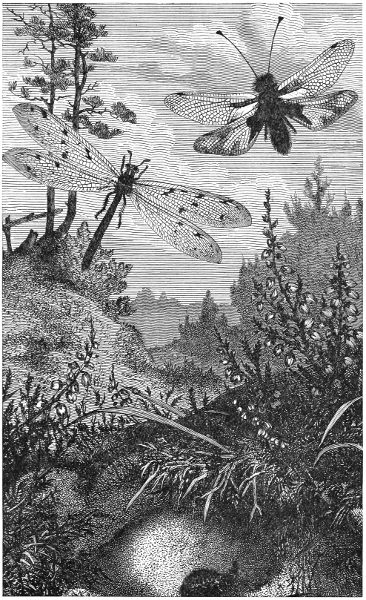

| 77. | Insect Life in Africa | „ | 276 |

| 80. | Insect Nest-Building | „ | 280 |

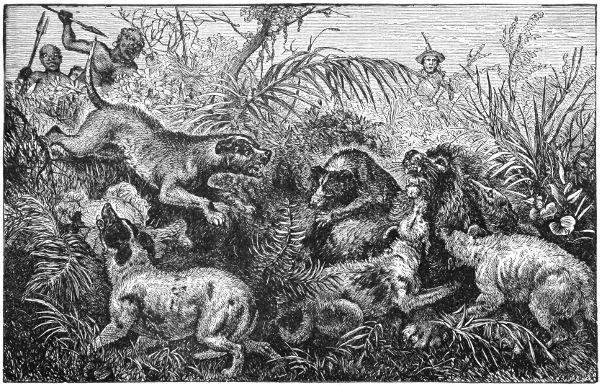

| 111. | In the Clutches of the Game | „ | 422 |

| 83. | Livingstone Ending his Last March at Ilala | „ | 288 |

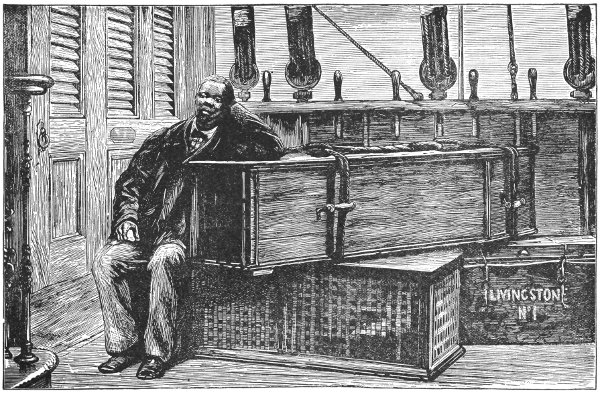

| 84. | Jacob Wainwright with Dr. Livingstone’s Remains at Aden | „ | 290 |

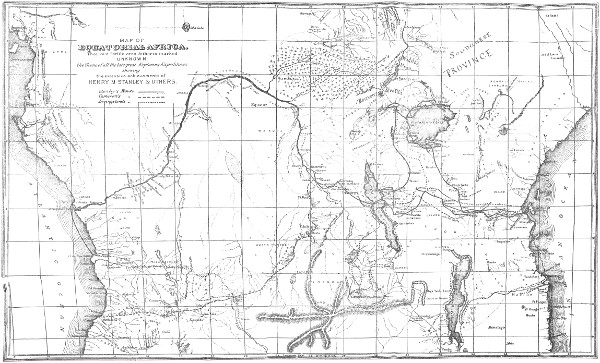

| 9. | Map of Stanley’s Last Route | „ | 17 |

| 110. | Mouth of the Congo | „ | 420 |

| 97. | Natives of Uganda | „ | 380 |

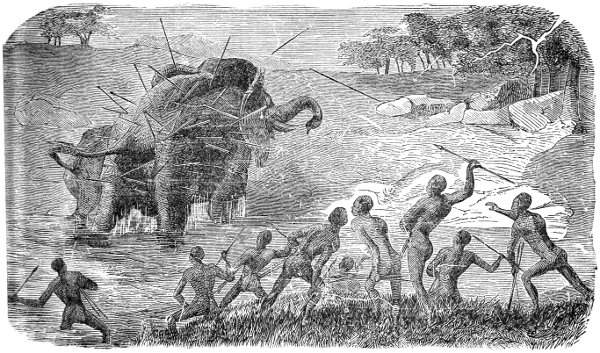

| 99. | Natives Coralling Wild Game | „ | 390 |

| 119. | On the Banks of the Nepoko[xix] | „ | 470 |

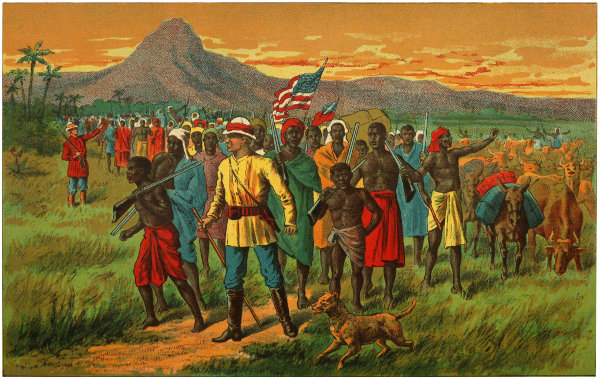

| 92. | Off for the Heart of Africa | „ | 356 |

| 42. | Rapids of the Livingstone River | „ | 120 |

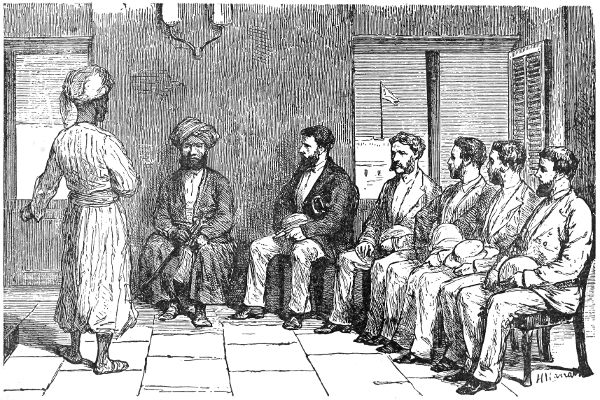

| 40. | Reception of the Officers of the Expedition at the Sultan’s Palace, Zanzibar | „ | 102 |

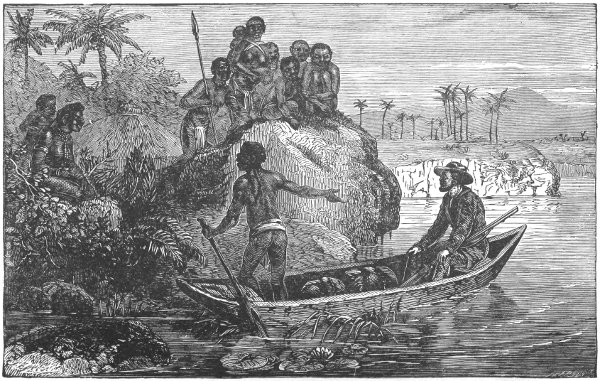

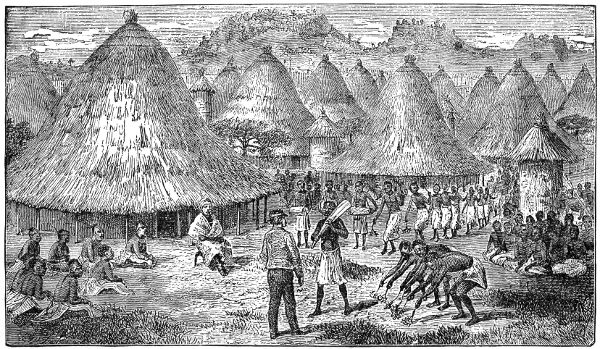

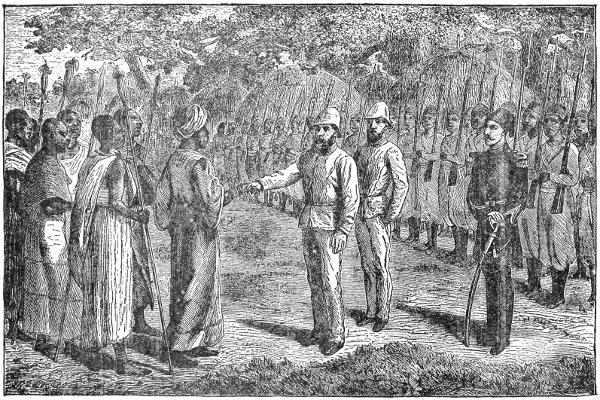

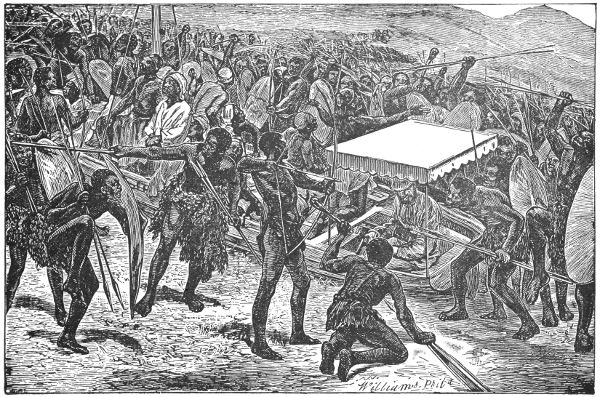

| 63. | Reception of the Chief Ruhingi | „ | 194 |

| 106. | Repelling the Attack of the Piratical Bangala | „ | 412 |

| 73. | Running down Elands | „ | 258 |

| 74. | Sounding the Alarm | „ | 260 |

| 48. | Sketch of an African Forest Scene | „ | 136 |

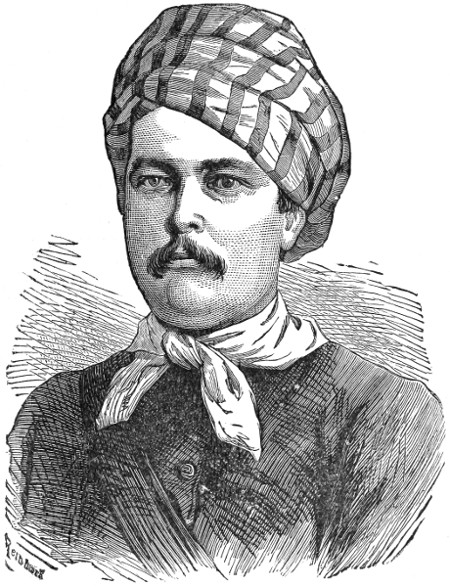

| 36. | Stanley, Henry M., as he Appeared on his First Expedition | „ | 92 |

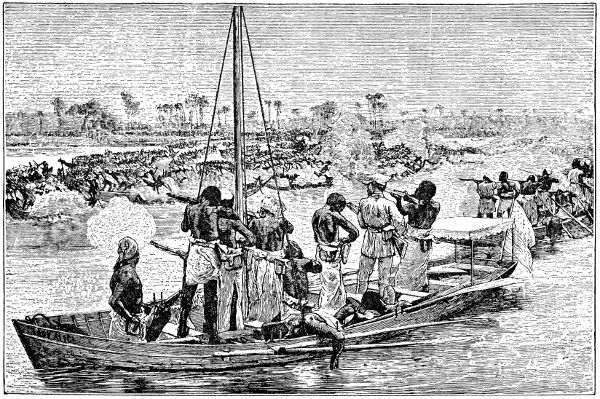

| 103. | Stanley Fighting his Way along the Lualala or Congo | „ | 406 |

| 118. | Stanley Quelling a Mutiny | „ | 460 |

| 107. | Stanley Returning to the Coast | „ | 414 |

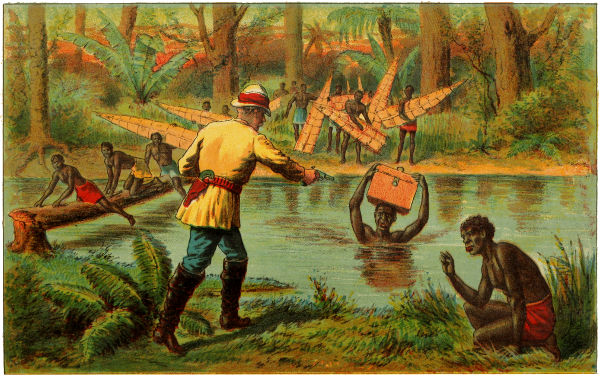

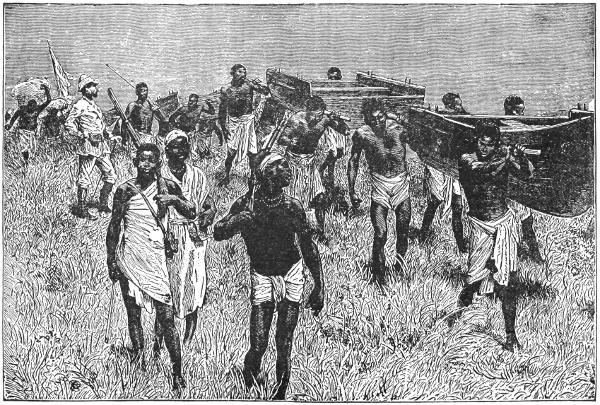

| 104. | Stanley’s Followers Seeking Supplies | „ | 408 |

| 116. | Supplies for the Caravan | „ | 452 |

| 64. | Slave Robbers’ Camp | „ | 200 |

| 123. | Terrific Fight for Life | „ | 490 |

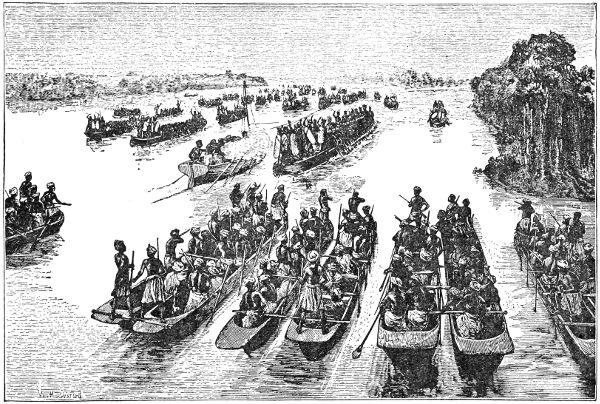

| 105. | The Battle of the Boats near the Confluence of the Aruwimi and the Livingstone Rivers | „ | 410 |

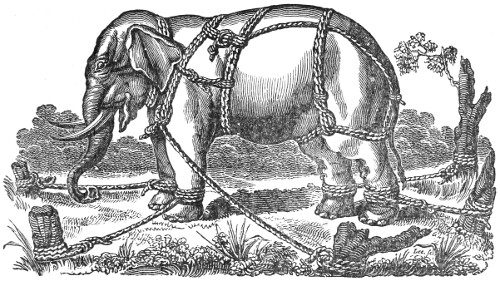

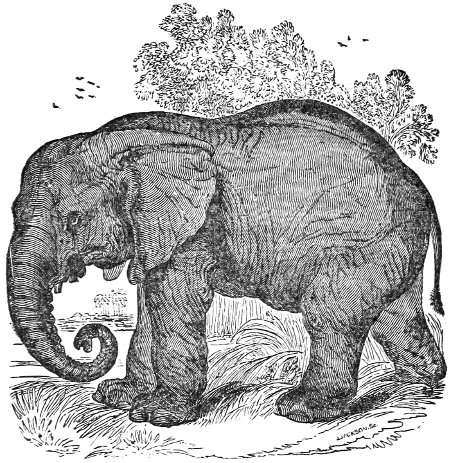

| 90. | The African Elephant | „ | 340 |

| 33. | The African “Tweet-Tweet” | „ | 80 |

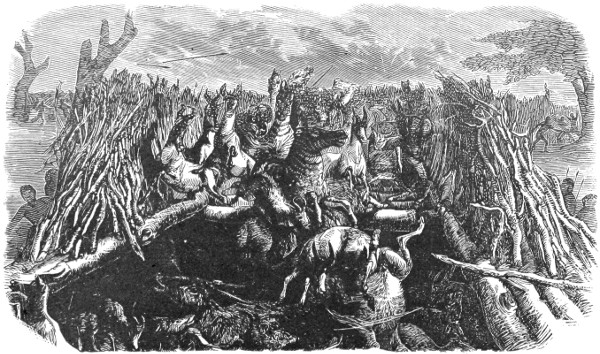

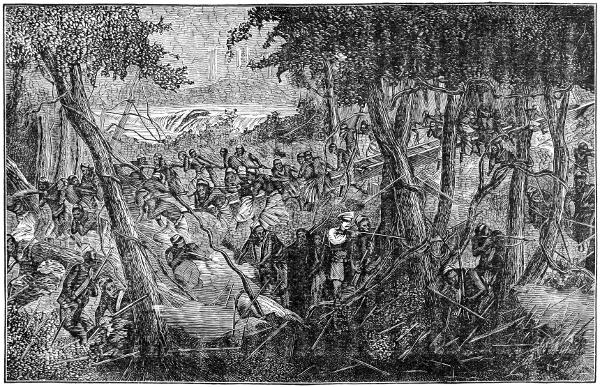

| 46. | The Attack on Mirambo | „ | 128 |

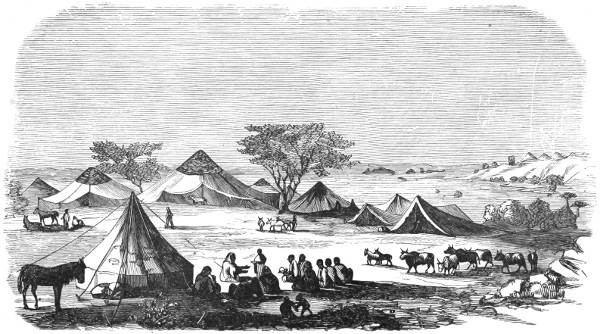

| 66. | The Camp of an Early Explorer | „ | 228 |

| 98. | The Demons of Bumbireh | „ | 384 |

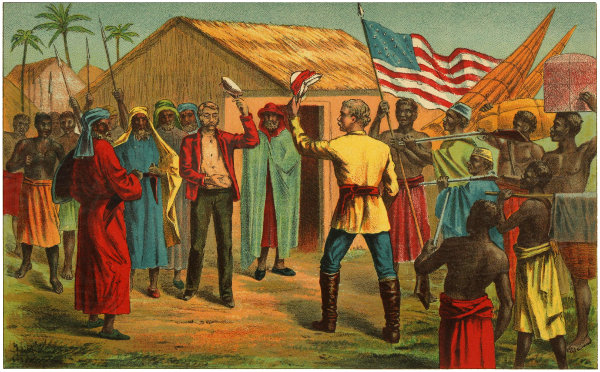

| 56. | The Discovery of Livingstone | „ | 160 |

| 41. | The Egyptian Cerastes | „ | 107 |

| 79. | The Terror of the Bird Kingdom | „ | 280 |

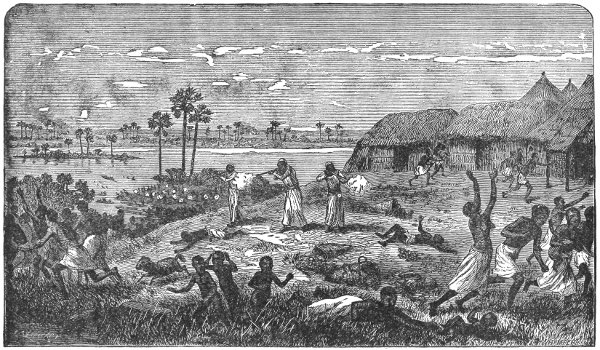

| 60. | The Massacre of the Manyuema Women | „ | 186 |

| 30. | The Reception of Livingstone by an African Chief | „ | 74 |

| 101. | The Hot Springs of Mtagata | „ | 400 |

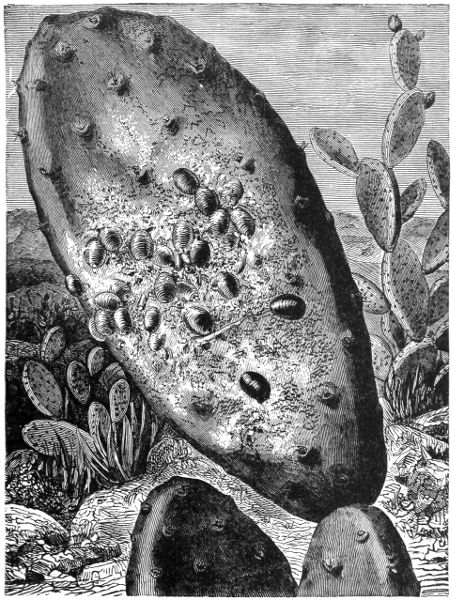

| 112. | The African Cactus | „ | 428 |

| 96. | The Victoria Nyanza | „ | 372 |

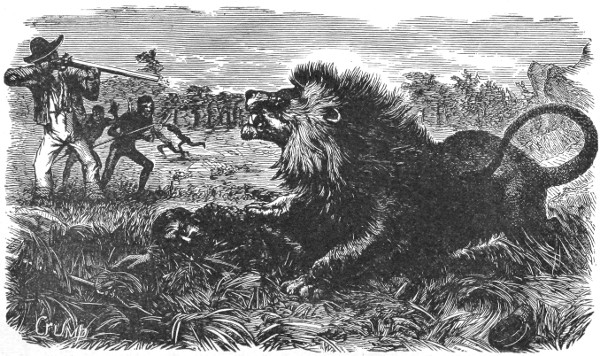

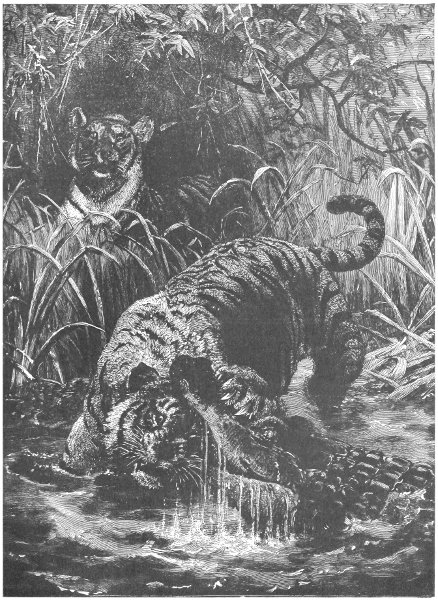

| 75. | The King of the Jungle | „ | 272 |

| 81. | The Last Mile of Dr. Livingstone’s Travels | „ | 282 |

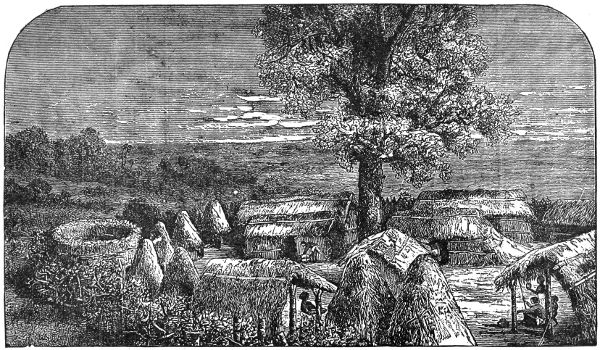

| 88. | The Village in which Livingstone’s Body was Prepared | „ | 314 |

| 109. | The Face of a Wangwana | „ | 418 |

| 43. | The African Tiger | „ | 120 |

| 115. | The Elephant Protecting her Young[xx] | „ | 452 |

| 44. | The Strong Beast Conquered | „ | 120 |

| 13. | The Python | „ | 26 |

| 45. | The Rhinoceros Bird | „ | 123 |

| 85. | The Last Entries in Dr. Livingstone’s Note-Book | „ | 298, 301 |

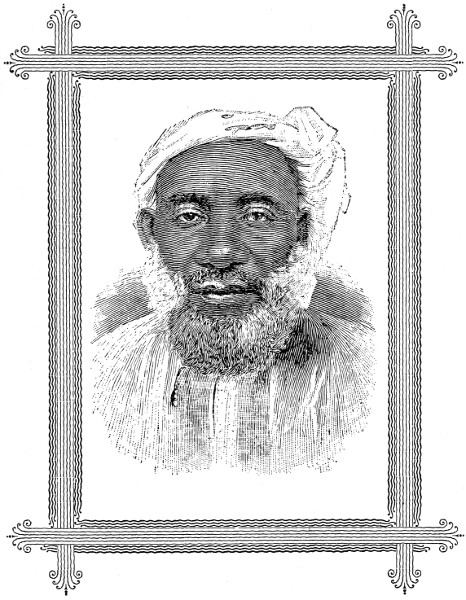

| 125. | Tippu-Tib | „ | 510 |

| 108. | Transporting the Sections of the Boat | „ | 416 |

| 24. | View on the Lualala | „ | 62 |

| 25. | View on the Zambesi | „ | 62 |

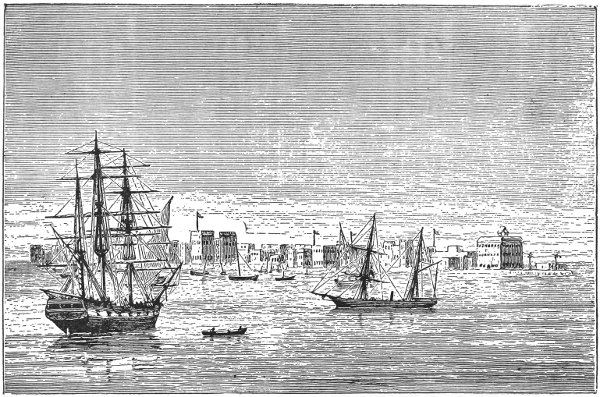

| 11. | View of Zanzibar | „ | 20 |

| 54. | Warlike Demonstrations | „ | 156 |

| 120. | Wild Game on the Aruwimi | „ | 476 |

| 94. | Wild Goat of Ugogo | „ | 359 |

| 126. | Wilderness Sketch | „ | 527 |

| 72. | Wreaking his Vengeance on a Tree | „ | 256 |

| 32. | Zulu Warrior | „ | 78 |

MAP OF

EQUATORIAL AFRICA.

That vast fertile area hitherto marked

UNKNOWN,

the Scene of all the late great Exploring Expeditions,

showing

the extensive achievements of

HENRY M STANLEY & OTHERS.

| Stanley’s | Route | |

| Cameron’s | „ | |

| Livingstone’s | „ | |

[17]

STANLEY’S STORY·

OR,

THROUGH THE WILDS OF AFRICA.

A Brief Account of Africa — Its Ancient Civilization — Little Information Extant in Relation to Large Portions of the Continent — The Great Field of Scientific Explorations and Missionary Labor — Account of a Number of Exploring Expeditions, including those of Mungo Park, Denham and Clapperton, and others — Their Practical Results — Desire of Further Information Increased — Recent Explorations, notably those of Dr. Livingstone and Mr. Stanley, representing the New York “Herald” newspaper.

A work of standard authority among scholars says that “Africa is the division of the world which is the most interesting, and about which we know the least.” Its very name is a mystery; no one can more than approximately calculate its vast extent; even those who have studied the problem the most carefully widely disagree among themselves as to the number of its population, some placing it as low as 60,000,000, others, much in excess of 100,000,000 souls; its superficial[18] configuration in many portions is only guessed at; the sources of its mightiest river are unknown. The heats, deserts, wild beasts, venomous reptiles, and savage tribes of this great continent have raised the only barrier against the spirit of discovery and progress, elsewhere irrepressible, of the age, and no small proportion of Africa is to-day as much a terra incognita as when the father of history wrote. Many of its inhabitants are among the most barbarous and depraved of all the people of the world, but in ancient times some of its races were the leaders of all men in civilization and were unquestionably possessed of mechanical arts and processes which have long been lost in the lapse of ages. They had vast cities, great and elaborate works of art, and were the most successful of agriculturists. Noted for their skill in the management of the practical affairs of life, they also paid profound attention to the most abstruse questions of religion; and it was a people of Africa, the Egyptians, who first announced belief in the resurrection of the body and the immortality of the soul. Large numbers of mummies, still existing, ages older than the Christian era, attest the earnestness of the ancient faith in dogmas which form an essential part of the creed of nearly every Christian sect. The most magnificent of women in the arts of coquetry and voluptuous love belonged to this continent of which so much still sits in darkness. The art of war was here cultivated to the greatest perfection; and it was before the army of an African general that the Roman legions went down at Cannæ, and by whom the Empire came near being completely ruined. Indeed,[19] it may with much show of argument be claimed that the continent over so much of which ignorance and superstition and beasts of prey now hold thorough sway, was originally the cradle of art, and civilization, and human progress.

But if the northern portion of the continent of Africa was in the remote past the abode of learning and of the useful arts, it is certain that during recent periods other portions of the continent, separated from this by a vast expanse of desert waste, have supplied the world with the most lamentable examples of human misery and the most hideous instances of crime. Nor did cupidity and rapacity confine themselves in the long years of African spoliation to ordinary robbers and buccaneers. Christian nations took part in the horrid work; and we have the authority of accredited history for the statement that Elizabeth of England was a smuggler and a slave-trader. Thus Africa presents the interesting anomaly of having been the home of ancient civilization, and the prey of the modern rapacity and plunder of all nations. It is natural, therefore, that in regard to the plundered portions of this devoted continent, the world at large should know but little. It is also natural that with the advancement of the cause of scientific knowledge, humanity, genuine Christianity, and the rage for discovery, this vast territory should receive the attention of good and studious men and moral nationalities. Accordingly we find that during a comparatively recent period Africa has become a great field of scientific explorations and missionary labor, as well as of colonization.

[20]

The first people to give special and continued attention to discoveries in Africa, were the Portuguese. During the fifteenth century, noted for the great advance made in geographical discoveries, the kingdom of Portugal was, perhaps, the greatest maritime power of Christendom. Her sovereigns greatly encouraged and many of their most illustrious subjects practically engaged in voyages of discovery. They were pre-eminently successful both in the eastern and western hemisphere, and one of the results of their daring enterprise is the remarkable fact that Portuguese colonies are much more powerful and wealthy to-day than the parent kingdom.

The Portuguese sent many exploring expeditions along the coast of Africa, and in the course of a century they had circumnavigated the continent and planted colonies all along the shores of the Atlantic and the Indian oceans. Bartholmew Dias having discovered the Cape of Good Hope, the reigning sovereign of Portugal determined to prosecute the explorations still further, with the object of discovering a passage to India. This discovery was made by the intrepid and illustrious mariner, Vasco de Gama, November 20, 1497, a little more than five years after the discovery of America. He pursued his voyage along the eastern coast of Africa, discovering Natal, Mozambique, a number of islands, and finding people in a high stage of commercial advancement, with well-built cities, ports, mosques for the worship of Allah according to the Mohammedan faith, and carrying on a considerable trade with India and the Spice[21] Islands. Of this trade, Portugal long retained supremacy. Other European powers also meantime established colonies at different places on the African coast, so that in the sixteenth century a considerable portion of the outer shell, so to say, had been examined The vast interior, however, long remained unexplored, and much of it remains an utterly unknown primeval wilderness to this day. The settlements and colonies of the Portuguese, French, Dutch, and English were for commercial purposes only, and added very little to the general stock of information.

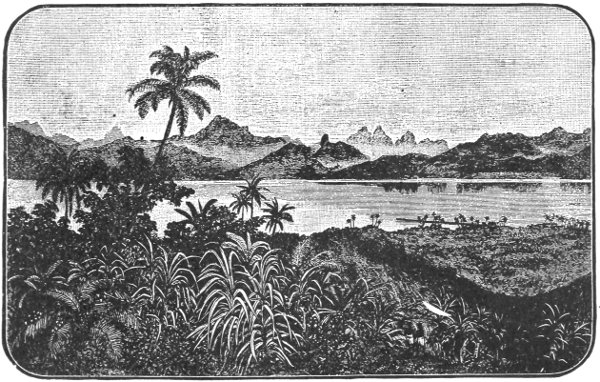

VIEW OF ZANZIBAR.

It was not until a year after the adoption of the Constitution of the United States that any organized effort in behalf of discoveries in Africa was made. In the city of London a Society for the Exploration of Interior Africa was formed in 1788, but it was not until seven years afterwards, that the celebrated Mungo Park undertook his first expedition. Thus it was more than three hundred years from the discovery of the Cape of Good Hope before even a ray of light began to penetrate the darkness of benighted Africa. Meantime, great empires had been overthrown and others established in their place and beneficent governments founded on both continents of the western world.

The life and adventures of Mungo Park form a story of exceeding interest, between which and the life and adventures of Dr. Livingstone there are not a few points of remarkable coincidence. Park was a native of Scotland, and one of many children. He was educated also in the medical profession. Moreover, while he was making his first tour of discovery[22] in Africa, having long been absent from home, reports of his death reached England and were universally credited. His arrival at Falmouth in December 1797, caused a most agreeable surprise throughout the kingdom. An account of his travels abounding with thrilling incidents, including accounts of great suffering from sickness and cruelty at the hands of Mohammedan Africans on the Niger, was extensively circulated. Many portions of this narrative were in about all the American school books during the first half of the nineteenth century, and the name of Mungo Park became as familiar as household words in the United States. In 1805, Park undertook another tour of discovery, which he prosecuted for some time with indomitable courage and against difficulties before which an ordinary mind would have succumbed. He navigated the Niger for a long distance, passing Jennee, Timbuctoo, and Yaoori, but was soon after attacked in a narrow channel, and, undertaking to escape by swimming, was drowned. His few remaining white companions perished with him.

The discoveries of this celebrated man were in that part of Africa which lies between the equator and the 20th degree of north latitude. They added much to the knowledge of that portion of the country, and keenly whetted the desire of further information. Several journeys and voyages up rivers followed, but without notable result till the English expedition under Denham and Clapperton in 1822. This expedition started with a caravan of merchants from Tripoli on the Mediterranean, and after traversing the great desert reached Lake Tsad in interior Africa.[23] Denham explored the lake and its shores, while Lieut. Clapperton pursued his journey westward as far as Sakatu, which is not greatly distant from the Niger. He retraced his steps, and having visited England, began a second African tour, starting from near Cape Coast Castle on the Gulf of Guinea. Traveling in a northeastern direction, he struck the Niger at Boussa, and going by way of Kano, a place of considerable commercial importance, again arrived at Sakatu, where he shortly afterwards died. He was the first man who had traversed Africa from the Mediterranean sea to the Gulf of Guinea. Richard Lander, a servant of Lieut. Clapperton, afterwards discovered the course of the Niger from Boussa to the gulf, finding it identical with the river Nun of the seacoast.

DR. DAVID LIVINGSTONE.

Other tours of discovery into Africa have been made to which it is not necessary here to refer. The practical result of all these expeditions, up to about the middle of the nineteenth century, was a rough outline of information in regard to the coast countries of Africa, the course of the Niger, the manners and customs of the tribes of Southern Africa, and a little more definite knowledge concerning Northern and Central Africa, embracing herein the great desert, Lake Tsad, the river Niger, and the people between the desert and the Gulf of Guinea. Perhaps the most comprehensive statement of the effect of this information upon Christian peoples was that it seemed to conclusively demonstrate an imperative demand for missionary labors. Even the Mohammedans of the Moorish Kingdom of Ludamar, set loose a wild boar upon Mungo Park. They were astonished[24] that the wild beast assailed the Moslems instead of the Christian, and afterwards shut the two together in a hut, while King and council debated whether the white man should lose his right arm, his eyes, or his life. During the debate, the traveler escaped. If the Mohammedan Africans were found to be thus cruel, it may well be inferred that those of poorer faith were no less bloodthirsty. And thus, as one of the results of the expeditions to which we have referred, a renewed zeal in proselytism and discovery was developed.

Thus, the two most distinguished African travellers, and who have published the most varied, extensive, and valuable information in regard to that continent, performed the labors of their first expeditions cotemporaneously, the one starting from the north of Africa, the other from the south. We can but refer to the distinguished Dr. Heinreich Barth, and him who is largely referred to in this volume, Dr. David Livingstone. The expeditions were not connected the one with the other, but had this in common that both were begun under the auspices of the British government and people. A full narrative of Dr. Barth’s travels and discoveries has been published, from which satisfactory information in regard to much of northern and central Africa may be obtained. The narrative is highly interesting and at once of great popular and scientific value. Hence the world has learned the geography of a wide expanse of country round about Lake Tsad in all directions; far toward Abyssinia northeasterly, as far west by north as Timbuctoo, several hundred miles southeasterly, and as[25] far toward the southwest, along the River Benue, as the junction of the Faro. Dr. Barth remained in Africa six years, much of the time without a single white associate, his companions in the expedition having all died. Dr. Overweg, who was the first European to navigate Lake Tsad, died in September, 1852. Mr. Richardson, the official chief of the expedition, had died in March of the previous year.

But unquestionably the most popular of African explorers is Dr. Livingstone, an account of whose first expedition—1849-52—has been read by a great majority of intelligent persons speaking the English language. Large and numerous editions were speedily demanded, and Africa again became an almost universal topic of discourse. Indeed, intelligence of Dr. Livingstone’s return after so many years of toil and danger, was rapidly spread among the nations, accompanied by brief reports of his explorations, and these prepared the way for the reception of the Doctor’s great work by vast numbers of people. Every one was ready and anxious to carry the war of his reading into Africa. And afterwards, when Dr. Livingstone returned to Africa, and having prosecuted his explorations for a considerable period reports came of his death at the hands of cruel and treacherous natives, interest in exact knowledge of his fate became intense and appeared only to increase upon the receipt of reports contradicting the first, and then again of rumors which appeared to substantiate those which had been first received. In consequence of the conflicting statements which, on account of the universal interest in the subject, were published in the[26] public press throughout the world, the whole Christian church, men of letters and science became fairly agitated. The sensation was profound, and, based upon admiration of a man of piety, sublime courage, and the most touching self-denial in a great cause to which he had devoted all his bodily and intellectual powers, it was reasonable and philosophical.

It is not surprising, therefore, that the English government should have fitted out an expedition in search of Livingstone. Accordingly, the Livingstone Search Expedition, as it is called, was organized early in the winter of 1871-72, and under command of Lieut. Dawson, embarked on its destination, on the 9th of February of the last year. The expedition reached Zanzibar April 19, and the members were most kindly received by the Sultan, Sayid Bergash, and greatly assisted by his Grand Vizier, Sayid Suliman. A company of six Nasik youths, originally slaves in a part of Africa through which the Search Expedition would pass, were being drilled for the purpose, and were expected to be of great assistance.

But before intelligence of the Livingstone Search Expedition at Zanzibar awaiting favorable weather, had arrived, the world was startled by the news that a private expedition, provided solely by the New York “Herald” newspaper, and in charge of Mr. Henry M. Stanley, had succeeded, after surmounting incredible difficulties, in reaching Ujiji, where a meeting of the most remarkable nature took place between the great explorer and the representative of the enterprising journal of New York. Unique in its origin, most remarkable in the accomplishment of its beneficent[27] purpose, the Herald-Livingstone expedition had received the considerate approval of mankind, and Mr. Stanley had come to be regarded, and with justice, as a practical hero of a valuable kind. His accounts of his travels, his despatches to the “Herald” from time to time, the more formal narratives furnished by him, composed a story of the deepest interest and, when properly considered, of the greatest value. This interest has also been deepened and greatly strengthened by the later labors of Stanley in the great field made memorable by Livingstone; and in the results of later explorations we have it fairly demonstrated that the life-work of the elder explorer did not end with his death, but has fallen upon the shoulders of one in every respect qualified to carry on the good work.

To fully appreciate the work done and to thoroughly comprehend its bearing upon Christian civilization, the reader will find in these pages a brief resume of the most important incidents in the life history of Livingstone, with accounts of his several explorations into the African continent. Hence, these, in connection with those of Stanley respecting his later researches, will serve to make a volume of extremely interesting reading upon a subject of universal interest to all Christian people.

[28]

The General Geological Formation of the Continent — The Want of Comprehensive Investigation — Singular Facts as to the Desert of Sahara — The Question of the Antiquity of Man — Is Africa the Birth-place of the Human Race? Opinions of Scientists Tending to Answer in the Affirmative — Darwinism.

It is to be greatly regretted that no comprehensive geological surveys of Africa have ever been made; because there are certain questions, eventually to be settled by geology, whose determination, it appears to be agreed, will be finally resolved by investigations in this continent. In a volume of this nature, designed for the general reader, those facts and reasonings only need be referred to which may be supposed to have the most interest. Reference has already been made to Sir Roderick Murchison’s exposition of the trough-shaped form of South Africa in his discourse before the Royal Geographical Society in 1852—an exposition which was so remarkably substantiated by Dr. Livingstone in his journey across the continent from Loanda to Kilimane. Though in its geographical configuration Africa is not greatly unlike South America, in its geological structure it much more resembles the northern continent of the western hemisphere. The Appalachian range of mountains extending through nearly the whole of the eastern portion of North America, parallel with the coast,[29] and the Rocky Mountains and Sierra Nevadas in the west, bear a notable resemblance to those ranges of mountains in Africa, which, rising first in the northern portions of Senegambia, pursue a south-easterly, then a southerly course to near the southern limit of the continent, when they sharply bend toward the northeast, and with many lofty peaks, some of which reach the region of eternal snow, pass through Mozambique, Zanguebar, and end not until after they have passed through Abyssinia and Nubia, and penetrated the limits of Egypt. In Tripoli, Tunis, Algeria, and Morocco, is the Atlas range, between which and the beginning of the other the distance is hardly so great as that between the southern limits of the Appalachian range and the mountains of Mexico. The course of each of the great rivers of these continents is also across the degrees of latitude instead of generally parallel with the equator, as is the case with the great river of South America. There is a similarity also between North America and Africa in an extensive system of inland lakes of fresh water and vast extent.

ARAB CHIEF OF CENTRAL AFRICA.

The geological structure of the mountains of Africa, especially of South Africa, appears to be quite uniform. They have a nucleus of granite which often appears at the surface and forms the predominating rock, but in the greater proportion of the mountains, perhaps, the granite is overlain by vast masses of sandstone, easily distinguished by the numerous pebbles of quartz which are embedded in it. The summit, when composed of granite, is usually round and smooth, but when composed of the quartzose sandstone is often perfectly flat. Of this Table Mount,[30] in South Africa, is a notable illustration. The thickness of this stratum of sandstone is sometimes not less than 2,000 feet. Such is the case in the Karoo mountains of Cape Colony. When thus appearing, it may be seen forming steep, mural faces, resembling masonry, or exhibiting a series of salient angles and indentations as sharp, regular, and well-defined as if they had been chiselled. With the granite are often associated primitive schists, the decomposition of which seems to have furnished the chief ingredients of the thin, barren clay which forms the characteristic covering of so much of the South African mountains. In some places, more recent formations appear, and limestone is seen piercing the surface. The geological constitution of the Atlas Mountains, in northwestern Africa, presents old limestone alternating with a schist, often passing to a well-characterized micaceous schist, or gneiss, the stratification of which is exceedingly irregular. Volcanic rocks have here been found in small quantities. There are veins of copper, iron, and lead.

In Egypt we find the alluvial soil a scarcely less interesting object of study than the rocks upon which it rests. These are limestone, sandstone, and granite, the latter of which, in Upper Egypt, often rises 1,000 feet above the level of the Nile. Not many years ago were discovered about 100 miles east of the Nile, and in 28 deg. 4 min. of north latitude the splendid ruins of the ancient Alabastropolis, which once derived wealth from its quarries of alabaster. Farther south are the ancient quarries of jasper, porphyry, and verd antique. The emerald mines of Zebarah lay near the Red Sea.

[31]

The Atlas range in Algeria is better known than elsewhere. It is as described above, but at Calle there are distinct traces of ancient volcanoes. Iron, copper, gypsum, and lead are found in considerable quantities. Cinnabar is found in small quantities. Salt and thermal springs abound in many parts of Algeria, amethysts in Morocco, slates in Senegambia, and iron in Liberia, Guinea, the Desert of Sahara and many other parts of Africa.

Gold, gold-dust, and iron are among the best known of the mineral riches of Africa, and are the most generally diffused throughout the continent. In the country of Bambouk, in Senegambia, most of the gold which finds its way to the west coast is found. Here the mines are open to all, and are worked by natives who live in villages. The richest gold mine of Bambouk, and the richest, it is believed, yet discovered in Africa, is that of Natakoo—an isolated hill, some 300 feet high and 3,000 feet in circumference, the soil of which contains gold in the shape of lumps, grains, and spangles, every cubic foot being loaded, it is said, with the precious metal. The auriferous earth is first met with about four feet from the surface, becoming more abundant with increase of depth. In searching for gold the natives have perforated the hill in all directions with pits some six feet in diameter and forty or fifty feet deep. At a depth of twenty feet from the surface lumps of pure gold of from two to ten grains weight are found. There are other mines in this portion of Africa, gold having been found distributed over a surface of 1,200 square miles. The precious metal is not only found[32] in hills, the most of which are composed of soft argillaceous earth, but in the beds of rivers and smaller streams, so that the lines of Bishop Heber’s well-known missionary hymn are truthful as well as poetical:—

The gold mines of Semayla, which are some forty or fifty miles northward of those of Natakoo, though nearly as rich as the latter, are in hills of rock and sandstone, which substances are pounded in mortars that the gold may be extracted. Barth judged that gold would be found in the Benue river, the principal eastern tributary of the Niger. Gold, silver, iron, lead and sulphur have been found in large quantities, and were long profitably mined in the mountainous districts of Angola. In Upper Guinea gold and iron are deposited in granitic or schistose rocks. The interior contains vast quantities of iron which might be easily mined, but the natives are not sufficiently enterprising to accomplish much in this respect. Gold is also obtained in the beds of some of the rivers of Guinea. In Mozambique, on the east coast, the Portuguese have for a great length of time had a considerable commerce in gold obtained from mines near the Zambezi, in the region near the western limit of that province. It has already been stated that here Dr. Livingstone discovered deposits of coal. Along the Orange and Vaal rivers, in extreme South Africa, have recently been discovered diamond fields which some noted scientists believe will yet prove to be among the richest in the world.

ARRIVAL OF THE EXPEDITION ON THE BANKS OF THE ZAMBESI.

[33]

Perhaps the portions of Africa which are the most interesting on account of geological investigations which have been made, are the valley of the Nile in Egypt, and the Desert of Sahara. It is well known that the river Nile annually overflows its banks in Egypt, and the inundation remaining a considerable period, a thin layer of soil is each year added to that which existed there before. This Nile mud, as it is called by geologists, has been the subject of considerable scientific examination for many years. In his work upon the “Geological Evidences of the Antiquity of Man,” Sir Charles Lyell gives a full account of certain systematic borings in the Nile mud which were made between the years 1851 and 1854, under the superintendency of Mr. Leonard Horner, but who employed to practically conduct the examinations an intelligent, enterprising, and faithful Armenian officer of engineers, Hekekyan Bey, who had for many years pursued scientific studies in England, was in every way qualified for the task, and, unlike Europeans, was able to endure the climate during the hot months, when the waters of the Nile flow within their banks. Sir Charles Lyell states that the results of chief importance arising out of this inquiry were obtained from two sets of shafts and borings—sunk at intervals in lines crossing the great valley from east to west. One of these consisted of fifty-one pits and artesian perforations made where the valley is sixteen miles wide between the Arabian and the Libyan deserts, in the latitude of Heliopolis, about eight miles above the apex of the delta. The other line of pits and borings, twenty[34] seven in number, was in the parallel of Memphis where the valley is five miles wide. Besides Hekekyan Bey, several engineers and some sixty workmen, inured to the climate, were employed for several years, during the dry season, in the furtherance of these interesting investigations.

It was found that in all the works the sediment passed through was similar in composition to the ordinary Nile mud of the present day, except near the margin of the valley, where thin layers of quartzose sand, such as is sometimes blown from the adjacent desert by violent winds, were observed to alternate with the loam. A remarkable absence of lamination and stratification, the geologist goes on to say, was observed almost universally in the sediment brought up from all points except where the sandy layers above alluded to occurred, the mud closely agreeing in character with the ancient loam of the Rhine. Mr. Horner attributes this want of all indication of successive deposition to the extreme thinness of the film of matter which is thrown down annually on the great alluvial plain during the season of inundation. The tenuity of this layer must indeed be extreme, if the French engineers are tolerably correct in their estimate of the amount of sediment formed in a century, which they suppose not to exceed on the average five inches. It is stated, in other words, that the increase is not more than the twentieth part of an inch each year, or one foot in the period of 240 years. All the remains of organic bodies found during these investigations under Hekekyan Bey belonged to living species. Bones of[35] the ox, hog, dog, dromedary, and ass were not uncommon, but no vestiges of extinct mammalia were found, and no marine shells were anywhere detected. These excavations were on a large scale, in some instances for the first sixteen or twenty-four feet. In these pits, jars, vases, and a small human figure in burnt clay, a copper knife, and other entire articles were dug up; but when water soaking through from the Nile was reached, the boring instrument used was too small to allow of more than fragments of works of art being brought up. Pieces of burnt brick and pottery were constantly being extracted, and from all depths, even where they sank sixty feet below the surface toward the central parts of the valley. In none of these cases did they get to the bottom of the alluvial soil. If it be assumed that the sediment of the valley has increased at the rate of six inches a century, bricks at the depth of sixty feet have been buried 12,000 years. If the increase has been five inches a century, they have lain there during a period of 14,400 years. Lyell states further on that M. Rosiere, in the great French work on Egypt has estimated the rate of deposit of sediment in the delta at two inches and three lines in a century. A fragment of red brick has been excavated a short distance from the apex of the delta at a depth of seventy-two feet. At a rate of deposit of two and a-half inches a century, a work of art seventy-two feet deep must have been buried more than 30,000 years ago. Lyell frankly states, however, that if the boring was made where an arm of the river had been silted up at a time when the apex of the delta was[36] somewhat further south, or more distant from the sea than now, the brick in question might be comparatively very modern. It is agreed by the best geologists that the age of the Nile mud cannot be accurately, but only approximately calculated by the data thus far furnished. The amount of matter thrown down by the waters in different parts of the plain varies so much that to strike an average with any approach to accuracy must be most difficult. The nearest approach, perhaps, as has been observed by Baldwin, to obtaining an accurate chronometric scale for ascertaining the age of the deposits of the Nile at a given point, was made near Memphis, at the statue of King Rameses. It is known that this statue was erected about the year 1260 B. C. In 1854 it had stood there 3,114 years. During that time the alluvium had collected to the depth of nine feet and four inches above its base, which was at the rate of about three and a half inches in each century. Mr. Horner found the alluvium, below the base of the statue, to be thirty feet deep, and pottery was found within four inches of the bottom of the alluvium. If the rate of accumulation previous to the building of the statue had been the same as subsequently, the formation of the alluvium began, at that point, about 11,660 years before the Christian era, and men lived there some 12,360 years ago, cultivating the then thin soil of the valley. But it would appear to be certain that the average deposit is so slight annually that many centuries more than those formerly quite universally received as the age of the world for the stage of mankind’s achievements must[37] have passed since the work of man’s hands have been buried under these vast deposits of alluvium. Thus, geology insists, is the fact of man’s existence, long before the historic era, conclusively established.

AN OBJECT OF INTENSE INTEREST.

The Desert of Sahara presents some interesting facts of the same nature. It has already been stated that this part of Africa was ocean within a comparatively recent geological period. Tristram and several French officers of scientific attainments, who have made geological examinations of large portions of the desert have shown that the northern margin is lined with ancient sea-beaches and lines of terraces—the “rock-bound coasts” of the old ocean. Numerous salt-lakes exist in the desert which are tenanted by the common cockle. A species of Haligenes which inhabits the Gulf of Guinea is found in a salt lake in latitude 30 deg. north and longitude 7 deg. east, separated, therefore, from its present marine habitat by the whole extent of the great desert, and the vast expanse of Soudan and Guinea. Geologists hence conclude that the existing fauna, including man, occupied Africa long before the Sahara became dry land. Reference has been made in the preceding chapter to the supposed remarkably beneficent effect this great expanse of desert, heated sands, and hot air, has upon the climate, and consequently upon the civilization of Europe.

It is probable that from the fact that Sahara was about the last extensive portion of earth to be abandoned by the ocean, that the general opinion became prevalent that the continent of Africa was, geologically, the most recent of the grand divisions of the[38] earth. Though supposed to be the oldest in civilization, it has been supposed to be the youngest in geological constitution. I am informed by scientific men that on account of recent investigations and reasonings, the opinion has for some time been gaining ground that Africa is likely to be shown to be the oldest part of the globe in both respects, and to have been the original birthplace of the race of man.

The negroid race, comprehending the Negroes, Hottentots, and Algutos, are, it is claimed by many scientists, the most ancient of all the types of mankind, and since their appearance on earth vast geographical changes have taken place. Continents have become ocean and sea has become land. “The negroes,” says Lubbock, “are essentially a non-navigating race, they build no ships, and even the canoes of the Feejeeans are evidently copied from those of the Polynesians. Now what is the geographical distribution of the race? They occupy all Africa south of Sahara, which neither they nor the rest of the true African fauna have ever crossed. And though they do not occur in Arabia, Persia, Hindoostan, Siam, or China, we find them in Madagascar, and in the Andaman Islands; not in Java, Sumatra, or Borneo, but in the Malay Peninsula, in the Phillippine Islands, New Guinea, the New Hebrides, New Caledonia, the Feejee Islands, and in Tasmania. This remarkable distribution is perhaps most easily explicable on the hypothesis that since the negroid race came into existence there must have been an immense tract of land or a chain of islands stretching from the eastern coast of Africa right across the Indian ocean; and secondly[39] that the sea then occupied the area of the present great desert. In whatever manner, however, these facts are to be explained, they certainly indicate that the race is one of very great antiquity.” “It is manifest,” says Baldwin in his Pre-Historic Nations, “that Africa at a remote period was the theatre of great movements and mixtures of peoples and races, and that its interior countries had then a closer connection with the great civilizations of the world than at any time during the period called historical.” It is the opinion of this writer that the Cushite race—the Ethiopians of Scripture—appeared first in the work of civilization, and that in remote antiquity that people exerted a mighty and wide-spread influence in human affairs, whose traces are still visible from farther India to Norway. Nor is he by any means alone in the opinion that the Carthagenians, ages ago, sent their ships across the Atlantic to the American continent. The Cushites, or original Ethiopians originated in Arabia, but their descendents are still found in northern Africa from Egypt to Morocco. Of this race are the Tuariks, the robbers of the Great Desert, to this day among the most magnificent specimens of physical man to be found anywhere on the globe.

The final solution of these problems of the geological status of Africa, and the great antiquity of man can but be of the greatest interest to all thoughtful persons. Unquestionably their solution will be greatly hastened, should Dr. Livingstone succeed in the great enterprise upon which he is now engaged, and soon make known to the world the true sources of the Nile. His success therein would stimulate endeavor,[40] study, exploration, and, it is to be hoped, comprehensive and systematic surveys of a continent the evidences of whose civilization in remote ages lie buried among the debris of countless centuries.

We know, from the imperfect investigations which have already been made, that cities have been engulfed in the sands of Sahara. We know that vast changes have taken place in the physical structure of the continent of Africa and of the world since the negro race first appeared. It is not improbable, therefore, that where for so many ages beasts of prey and savage tribes have occupied a land oppressed with heat and burdened with many ills, there may yet be found evidences of former civilization and power in greatest possible contrast to present barbarism and national weakness. And who shall say that when the face of the continent was changed, whether by a great convulsion or by a gradual process, some of the people did not migrate northward, cross the Mediterranean and populate the continent which has since become the abode of the highest civilization and the greatest intellectual culture? Who shall say that these races of remote antiquity were not possessed of culture and arts and literature placing them very high in the scale of civilization? Within the historic period those nations have passed away which were the acknowledged parents of modern culture and art. The power and versatility of the human mind, reason, eloquence, and poetry, were most sublimely illustrated by the Greeks, whose works still remain to benefit and instruct mankind. Yet the freedom and power of this wonderful people have for more than twenty centuries been annihilated.[41] The people, in the eloquent diction of Macaulay, have degenerated into timid slaves; the language into a barbarous jargon; and the beautiful temples of Athens “have been given up to the successive depredations of Romans, Turks, and Scotchmen.” The vast empire of Rome has passed entirely away within a few centuries. She had herself annihilated Carthage leaving nothing, as we have seen, of the arts, literature, or institutions of a people whose ships had sailed on every wave from the Hellespont to the Baltic, and, not improbably, from the Mediterranean to the delta of the Mississippi. Other great nations are also known to have passed away or been destroyed, the nature of their civilization and institutions being left to conjecture based upon a few monuments or a few literary remains preserved by foreign writers. It being once established that man existed ages before what is commonly called the beginning of the historic period it would be simply logical, considering many national destructions which have occurred during the historic period, to conclude by analogy that races of remote antiquity flourished and passed away leaving no sign, which has been yet discovered, of their power and civilization. It is evident the historian Macaulay thinks it not improbable such may be the fate of England, and he expressly states in a well-known passage that the time may come when only a single naked fisherman may be seen in the river of the ten thousand masts. It is difficult, if not impossible, for mankind entirely to overcome the tendency to decay.

ARAB SLAVE TRADERS.

We shall presently see that Africa is a field upon[42] which must soon be decided a great issue of politico-social importance; an issue which involves the abolition of polygamy, domestic slavery, and the suppression of the foreign slave trade. From what has gone before in this volume, it will have been seen that here, too, are likely to be most conclusively demonstrated the vast age of the world, the great antiquity of man, and the nature of his origin. In comparison of the settlement of this issue and the solution of these problems of science, even the discovery of the true sources of the Nile may be regarded as unimportant, except for the reason that Dr. Livingstone’s great achievement will arouse other men of science to similar sacrifices, labors, and fortitude. Thus Africa is found to present another remarkable contrast for our contemplation; for while civilization is there at a lower ebb than in any other grand division of the globe, the highest intellectual efforts of the most astute thinkers of the times are turning their best efforts thitherward, in the confident hope of greatly enlarging the sphere of human knowledge, and of extending the triumphs of science and civilization.

There are many, it is true, who imagine that the scientific inquiries which are being made in regard to the great age of the world, the races which existed long anterior to the historic period, and the origin of the human species are founded in a spirit of skepticism and hostility to Christian civilization, or, rather to Christianity as a religion. Doubtless there are many scientists who put no faith in Holy Writ, as much of it has been commonly understood. Others, and[43] those among the most distinguished of men, are no less devout believers in Christianity than they are firm believers in the great age of the world and antiquity of man. The devotees of Christianity have in not a few instances mistaken an ally for an enemy. This was notably the fact, in an example which is here most appropriate, in the case of the modern origin of the science of astronomy. The Christian church, as then existing, pronounced as religious heresy the plain truth that the world moves, and that the sun neither rises nor sets, but is stationary—the sublime centre of a universe of planets and stars, and, perhaps, inhabited worlds, whose movements must be controlled, as the vast system must have been originated, by One of infinite wisdom and power and goodness. In due course of time it was discovered that astronomy did not militate against Christianity, and the church not only ceased putting astronomers in prison, but learned that the acceptance of all truth, come from whatever source it may, is a Christian duty. And many of the most distinguished astronomers have been no less earnest exemplars of the Christian system of religion than any monk who ever wore the pavements of a monastery and left the world no wiser or better than he found it.