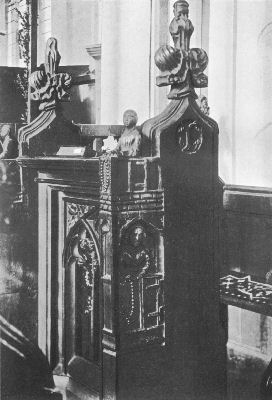

"PEDLAR'S SEAT," SWAFFHAM CHURCH

"PEDLAR'S SEAT," SWAFFHAM CHURCH

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Folklore as an Historical Science, by George Laurence Gomme This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: Folklore as an Historical Science Author: George Laurence Gomme Release Date: June 18, 2007 [EBook #21852] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK FOLKLORE AS AN HISTORICAL SCIENCE *** Produced by Clare Boothby, Sam W. and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

First Published in 1908

| CHAPTER | ||

| I. | History and Folklore | pages 1-122 |

| Introductory | pages 1‑13 | |

| History and Local and Personal Traditions | 13-46 | |

| History and Folk-tales | 46-84 | |

| Traditional Law | 84-100 | |

| Mythology and Tradition | 100-110 | |

| Historians and Tradition | 110-120 | |

| II. | Materials and Methods | 123-179 |

| Traditional Material | 123-129 | |

| Myth, Folk-tale, and Legend | 129-153 | |

| Custom, Belief, and Rite | 154-179 | |

| III. | Psychological Conditions | 180-207 |

| IV. | Anthropological Conditions | 208-302 |

| Primitive Influences | 211-238 | |

| Earliest Types of Social Existence | 238-261 | |

| Australian Totem Society tested by the Evidence | 262-274 | |

| Totem Survivals in Britain | 274-296 | |

| Synopsis of Culture-structure of Semangs of Malay Peninsula | 297-302 | |

| V. | Sociological Conditions | 303-319 |

| VI. | European Conditions | 320-337 |

| VII. | Ethnological Conditions | 338-366 |

| Index | 367-371 |

| PAGE | ||

| 1. | Pedlar's Seat, Swaffham Church, Norfolk | Frontispiece |

| 2. | Carved Wooden Figure of the Pedlar in Swaffham Church | 8 |

| 3. | Carved Wooden Figure of the Pedlar's Dog in Swaffham Church | 8 |

Nos. 1-3 are taken from photographs, and show how the story of the Pedlar of Swaffham has been interpreted in carving. The costume of the Pedlar is noticeable. |

||

| 4. | The Pedlar of Lambeth and his Dog, figured in the window (now destroyed) of Lambeth Church (from Allen's History of Lambeth) | 20 |

| 5. | The Pedlar of Lambeth and his Dog as drawn in 1786 for Ducarel's History of Lambeth | 22 |

Nos. 4 and 5 illustrate the traces of the Pedlar legend in Lambeth, and the costume of the Pedlar, though later than that shown in the Swaffham carving, exhibits analogous features which are of interest to the argument. |

||

| 6. | Plan of the Site of the "Heaven's Walls" at Litlington, near Royston, Cambridgeshire (reprinted from Archæologia) | 43 |

| 7. | Sketch of Litlington Field (reprinted from Archæologia) | 44 |

Nos. 6 and 7 show the site and general appearance of this interesting relic of the Roman occupation of Britain. |

||

| 8. | Stone Monuments Erected as Memorials in a Kasya Village (reprinted from Asiatic Researches) | 55 |

| 9. | Stone Seats at a Kasya Village (reprinted from Asiatic Researches) | 55 |

| [Pg viii]10. | View in the Kasya Hills, showing Stone Memorials (reprinted from Asiatic Researches) | 56 |

No. 8 shows the practice among the primitive hill-tribes of India of erecting memorials in stone to tribal heroes, and No. 9 is a curious illustration of the stones used as seats by tribesmen at their tribal assemblies. No. 10 is a general view of the site occupied by these stone monuments. |

||

| 11. | The Auld Ca-knowe: Calling the Burgess Roll at Hawick (reprinted from Craig and Laing's Hawick Tradition) | 98 |

| 12. | The Hawick Moat at Sunrise (reprinted from Craig and Laing) | 99 |

The tribal gathering is well illustrated by No. 11, and the moat hill is shown in No. 12. |

||

| 13. | One of Five Stone Circles in the Fields Opposite the Glebe of Nymphsfield (reprinted from Sir William Wilde's Lough Corrib) | 101 |

| 14. | Carn-an-Chluithe To Commemorate the Defeat and Death of the Youths of the Dananns (reprinted from Wilde) | 102 |

| 15. | The Cairn of Ballymagibbon, near the road passing from Cong To Cross (reprinted from Wilde) | 102 |

Nos. 13-15 are selected from Sir William Wilde's admirable account of the great conflict on the field of Moytura. They serve to show that the fight was an historical event. |

||

| 16. | Altar dedicated to the Field Deities of Britain, found at Castle Hill on the wall of Antoninus Pius | 105 |

It is important to remember that the Romans recognised the gods of the conquered people, and this is one of the most important archæological proofs of the fact. |

||

| 17. | Roman Sculptured Stone found at Arniebog, Cumbernauld, Dumbartonshire, showing a naked Briton as a captive | 112 |

To the evidence derived from classical writers as to the nakedness of some of the inhabitants of early Britain, it is possible to add the evidence of the memorial stone. This example is reproduced from Sir Arthur Mitchell's Past in the Present, and there is at least one other example. |

||

| [Pg ix]18. | Representation of an Irish Chieftain seated at Dinner (from Derrick's The Image of Ireland, by kind permission of Messrs. A. & E. Black) | 183 |

This is reproduced from the very excellent reprint (1883) of this remarkable book, published originally in 1581. The whole book is historically valuable as showing the undeveloped nature of Irish culture. The flesh was boiled in the hide, the fire is lighted in the open camp, and the entire rudeness of the scene depicts the people "whose usages I behelde after the fashion there sette downe." |

||

| 19. | Long Meg and her Daughters (from a photograph by Messrs. Frith) | 193 |

| 20. | Stone Circles on Stanton Moor (from Archæologia) | 193 |

Nos. 19 and 20 are illustrations of two of the lesser-known circles about which the people hold such curious beliefs. |

||

| 21. | Chinese representation of Pygmies going about arm-in-arm for mutual protection (from Moseley's Notes by a Naturalist on H.M.S. Challenger, by permission of Mr. John Murray) | 242 |

| 22. | Semang of Kuala Kenering, Ulu Perak (from Skeat and Blagden's Pagan Races of the Malay Peninsula, by permission of Messrs. Macmillan) | 242 |

| 23. | Negrito Type: Semang of Perak (from the same) | 243 |

| 24. | Semang of Kedah having a meal (from the same) | 244 |

| 25. | Tree Hut, Ulu Batu, about twelve miles from Kuala Lumpur, Selangor (from the same) | 298 |

The old-world traditions and the scientific observation of pygmy people are illustrated in No. 21 and Nos. 22-25 respectively. Though much has been written about the Pygmies, Messrs. Skeat and Blagden's account of the Semang people is by far the most thorough and important. |

||

| 26. | Rite of Baptism on the Font at Darenth, Kent (from Romilly Allen's Early Christian Symbolism) | 324 |

The crude paganism on the sculptured stone is confirmatory of the pagan elements preserved in custom, and this illustration from Kent, one of the earliest centres of Christianity in Britain, is singularly interesting from this point of view. |

||

| [Pg x] 27 and 28. | Two Scenes from the Anglo-Saxon Life of St. Guthlac by Felix of Crowland, depicting the attack of the Demons | 351, 352 |

These two plates belong to a series of eight which illustrate the life of the saint. They are less primitive in form than the story which they illustrate. By contrast with the remaining six, however, which are purely ecclesiastical in character, they show how this early episode kept its place among the events of the saint's life. |

If I have essayed to do in this book what should have been done by one of the masters of the science of folklore—Mr. Frazer, Mr. Lang, Mr. Hartland, Mr. Clodd, Sir John Rhys, and others—I hope it will not be put down to any feelings of self-sufficiency on my part. I have greatly dared because no one of them has accomplished, and I have so acted because I feel the necessity of some guidance in these matters, and more particularly at the present stage of inquiry into the early history of man.

I have thought I could give somewhat of that guidance because of my comprehension of its need, for the comprehension of a need is sometimes half-way towards supplying the need. My profound belief in the value of folklore as perhaps the only means of discovering the earliest stages of the psychological, religious, social, and political history of modern man has also entered into my reason for the attempt.

Many years ago I suggested the necessity for guidance, and I sketched out a few of the points involved (Folklore Journal, ii. 285, 347; iii. 1-16) in what was afterwards called by a friendly critic a sort of grammar of folklore. The science of folklore has advanced far since 1885 however, and not only new problems but new ranges of thought have gathered round it. Still,[Pg xii] the claims of folklore as a definite section of historical material remain not only unrecognised but unstated, and as long as this is so the lesser writers on folklore will go on working in wrong directions and producing much mischief, and the historian will judge of folklore by the criteria presented by these writers—will judge wrongly and will neglect folklore accordingly.

I hope this book may tend to correct this state of things to some extent. It is not easy to write on such a subject in a limited space, and it is difficult to avoid being somewhat severely technical at points. These demerits will, I am sure, be forgiven when considered by the light of the human interest involved.

All studies of this kind must begin from the standpoint of a definite culture area, and I have chosen our own country for the purpose of this inquiry. This will make the illustrations more interesting to the English reader; but it must be borne in mind that the same process could be repeated for other areas if my estimate of the position is even tolerably accurate. For the purpose of this estimate it was necessary, in the first place, to show how pure history was intimately related to folklore at many stages, and yet how this relationship had been ignored by both historian and folklorist. The research for this purpose had necessarily to deal with much detail, and to introduce fresh elements of research. There is thus produced a somewhat unequal treatment; for when illustrations have to be worked out at length, because they appear for the first time, the mind is apt to wander from the main point at issue and to become lost in the subordinate issue arising from the working out of the[Pg xiii] chosen illustration. This, I fear, is inevitable in folklore research, and I can only hope I have overcome some of the difficulties caused thereby in a fairly satisfactory manner.

The next stage takes us to a consideration of materials and methods, in order to show the means and definitions which are necessary if folklore research is to be conducted on scientific lines. Not only is it necessary to ascertain the proper position of each item of folklore in the culture area in which it is found, but it is also necessary to ascertain its scientific relationship to other items found in the same area; and I have protested against the too easy attempt to proceed upon the comparative method. Before we can compare we must be certain that we are comparing like quantities.

These chapters are preliminary. After this stage we proceed to the principal issues, and the first of these deals with the psychological conditions. It was only necessary to treat of this subject shortly, because the illustrations of it do not need analysis. They are self-contained, and supply their own evidence as to the place they occupy.

The anthropological conditions involve very different treatment. The great fact necessary to bear in mind is that the people of a modern culture area have an anthropological as well as a national or political history, and that it is only the anthropological history which can explain the meaning and existence of folklore. This subject found me compelled to go rather more deeply than I had thought would be necessary into first principles, but I hope I have not[Pg xiv] altogether failed to prove that to properly understand the province of folklore it is necessary to know something of anthropological research and its results. In point of fact, without this consideration of folklore, there is not much value to be obtained from it. It is not because it consists of traditions, superstitions, customs, beliefs, observances, and what not, that folklore is of value to science. It is because the various constituents are survivals of something much more essential to mankind than fragments of life which for all practical purposes of progress might well disappear from the world. As survivals, folklore belongs to anthropological data, and if, as I contend, we can go so far back into survivals as totemism, we must understand generally what position totemism occupies among human institutions, and to understand this we must fall back to human origins.

The next divisions are more subordinate. Sociological conditions must be studied apart from their anthropological aspect, because in the higher races the social group is knit together far more strongly and with far greater purpose than among the lower races. The social force takes the foremost place among the influences towards the higher development, and it is necessary not only to study this but to be sure of the terms we use. Tribe, clan, family, and other terms have been loosely used in anthropology, just as state, city, village, and now village-community, are loosely used in history. The great fact to understand is that the social group of the higher races was based on blood kinship at the time when they set out to take their place in modern civilisation, and that we cannot[Pg xv] understand survivals in folklore unless we test them by their position as part of a tribal organisation. The point has never been taken before, and yet I do not see how it can be dismissed.

The consideration of European conditions is chiefly concerned with the all-important fact of an intrusive religion, that of Christianity, from without, destroying the native religions with which it came into contact, conditions which would of course apply only to the folklore of European countries.

Finally, I have discussed ethnological conditions in order to show that certain fundamental differences in folklore can be and ought to be explained as the results of different race origins. We are now getting rid of the notion that all Europe is peopled by the descendants of the so-called Aryans. There is too much evidence to show that the still older races lived on after they were conquered by Celt, Teuton, Scandinavian, or Slav, and there is no reason why folklore should not share with language, archæology, and physical type the inheritance from this earliest race.

In this manner I have surveyed the several conditions attachable to the study of folklore and the various departments of science with which it is inseparably associated. Folklore cannot be studied alone. Alone it is of little worth. As part of the inheritance from bygone ages it cannot separate itself from the conditions of bygone ages. Those who would study it carefully, and with purpose, must consider it in the light which is shed by it and upon it from all that is contributory to the history of man.

During my exposition I have ventured upon many[Pg xvi] criticisms of masters in the various departments of knowledge into which I have penetrated; but in all cases with great respect. Criticism, such as I have indulged in, is nothing more than a respectful difference of opinion on the particular points under discussion, and which need every light which can be thrown upon them, even by the humblest student.

I am particularly obliged to Mr. Lang, Mr. Hartland, Dr. Haddon, and Dr. Rivers, for kindly reading my chapter on Anthropological Conditions, and for much valuable and kind help therein; and especially I owe Mr. Lang most grateful thanks, for he took an immense deal of trouble and gave me the advantage of his searching criticism, always in the direction of an endeavour to perfect my faulty evidence. I shall not readily part with his letters and MS. on this subject, for they show alike his generosity and his brilliance.

To my old friend Mr. Fairman Ordish I am once more indebted for help in reading my sheets, and I am also glad to acknowledge the fact that two of my sons, Allan Gomme and Wycombe Gomme, have read my proofs and helped me much, not only by their criticism, but by their knowledge.

24 Dorset Square, N.W.

It may be stated as a general rule that history and folklore are not considered as complementary studies. Historians deny the validity of folklore as evidence of history, and folklorists ignore the essence of history which exists in folklore. Of late years it is true that Dr. Frazer, Prof. Ridgeway, Mr. Warde Fowler, Miss Harrison, Mr. Lang, and others have broken through this antagonism and shown that the two studies stand together; but this is only in certain special directions, and no movement is apparent that the brilliant results of special inquiries are to bring about a general consideration of the mutual help which the two studies afford, if in their respective spheres the evidence is treated with caution and knowledge, and if the evidence from each is brought to bear upon the necessities of each.

The necessities of history are obvious. There are considerable gaps in historical knowledge, and the further[Pg 2] back we desire to penetrate the scantier must be the material at the historian's disposal. In any case there can be only two considerable sources of historical knowledge, namely, foreign and native. Looking at the subject from the points presented by the early history of our own country, there are the Greek and Latin writers to whom Britain was a source of interest as the most distant part of the then known world, and the native historians, who, witnessing the terribly changing events which followed the break-up of the Roman dominion over Britain, recorded their views of the changes and their causes, and in course of time recorded also some of the events of Celtic history and of Anglo-Saxon history. Then for later periods, no country of the Western world possesses such magnificent materials for history as our own. In the vast quantity of public and private documents which are gradually being made accessible to the student there exists material for the illustration and elucidation of almost every side and every period of national life, and no branch of historical research is more fruitful of results than the comparison of the records of the professed historian with the documents which have not come from the historian's hands.

All this, however, does not give us the complete story. Necessarily there are great and important gaps. Contemporary writers make themselves the judges of what is important to record; documents preserved in public or private archives relate only to such events as need or command the written record or instrument, or to those which have interested some of the actors and their families. Hence in both departments of history, the historical narrative and the original record, it will[Pg 3] be found on careful examination that much is needed to make the picture of life complete. It is the detail of everyday thought and action that is missing—all that is so well known, the obvious as it passes before every chronicler, the ceremony, the faith, and the action which do not apparently affect the movements of civilisation, but which make up the personal, religious and political life of the people. It is always well to bear in mind that the historical records preserved from the past must necessarily be incomplete. An accident preserves one, and an accident destroys another. An incident strikes one historian, and is of no interest to another. And it may well be that the lost document, the unrecorded incident, is of far more value to later ages than what has been preserved. This condition of historical research is always present to the scientific student, though it is not always brought to bear upon the results of historical scholarship.[1] But the scope of the historian is gradually but surely widening. It is no longer possible to shut the door to geography, ethnography, economics, sociology, archæology, and the attendant studies if the historian desires to work his subject out to the full.[2] It is even getting to be admitted that an appeal must be made to folklore, though the extent and the method are not understood. After all that can be obtained from other realms of knowledge, it is seen that there is a large gap left still—a gap in the heart of things, a gap waiting to be[Pg 4] filled by all that can be learned about the thought, ideas, beliefs, conceptions, and aspirations of the people which have been translated for them, but not by them, in the laws, institutions, and religion which find their way so easily into history.

The necessities of folklore are far greater than and of a different kind from those of history. Edmund Spenser wrote three centuries ago "by these old customs the descent of nations can only be proved where other monuments of writings are not remayning,"[3] and yet the descent of nations is still being proved without the aid of folklore. It is certain that the appeal will not be made to its fullest extent unless the folklorist makes it clear that it will be answered in a fashion which commands attention. It appears to me that the preliminary conditions for such an appeal must be ascertained from the folklore side. History has not only justified its existence, but during the long period of years during which it has been a specific branch of learning it has shown its capacity for proceeding on strictly scientific and ever-widening lines. Folklore has neither had a long period for its study nor a completely satisfactory record of scientific work. It is, therefore, essential that folklore should establish its right to a place among the historical sciences. At present that right is not admitted. It is objected to by scholars who will not admit that history can proceed from anything but a dated and certified document, and by a few who do not admit that history has anything to do with affairs that do not emanate from the[Pg 5] prominent political or military personages of each period. It is silently, if not contemptuously ignored by almost every historical inquirer whose attention has not been specially directed to the evidence contained in traditional material. Thus between the difficulties arising from the interpretation of texts which, originating in oral tradition, have by reason of their early record become literature, and the difficulties arising from the objections of historians to accept any evidence that is not strictly historical in the form they assume to be historical, traditional material has not been extensively used as history. It has also been wrongly defined by historians. Thus, to give a pertinent example, so good a scholar as Mr. W. H. Stevenson, in his admirable edition of Asser's Life of King Alfred, lays to the crimes of tradition an error which is due to other causes. Indeed, he states the cause of the error correctly, but does not see that he is contradicting himself in so doing. It is worth quoting this case. It has to do with the identification of "Cynuit," a place where the Danes obtained a victory over the English forces, and Kenwith Castle in Devonshire has been claimed as the site of the struggle and "a place known as Bloody Corner in Northam is traditionally regarded as the scene of a duel between two of the chieftains in 877, and a monument recording the battle has been erected."[4] Mr. Stevenson's comment upon this is: "We have in this an instructive example of the worthlessness of 'tradition' which is here, as so frequently happens elsewhere, the outcome of the dreams of[Pg 6] local antiquaries, whose identifications become gradually impressed upon the memory of the inhabitants;" and he then proceeds to show that this particular tradition was produced by the suggestion of Mr. R. S. Vidal in 1804. Of course, the answer of the folklorist to this charge against the value of tradition is that the example is not a case of tradition[5] at all. On the contrary, it is a case of false history, started by the local antiquary, adopted by the scholars of the day, perpetuated by the government in its ordnance survey of the district, and kept alive in the minds of the people not by tradition but by a duly certified monument erected for the express purpose of commemorating the invented incident. There is then no tradition in any one of the stages through which the episode has passed. It is all history and false history. Historians cannot shake off their responsibilities by looking upon the local antiquary as the responsible author of tradition. They cannot but admit that the local antiquary belongs to the historical school, even though he is not a fully equipped member of his craft, and because he blunders they must not class him as a folklorist. They must bring better evidence than this to show the worthlessness of tradition. In the meantime it is the constant definition of tradition as worthless, the relegation of worthless history "to the realms of folklore,"[6] which does so[Pg 7] much harm to the study of folklore as a science.[7] Because the historian misnames an historical error as tradition, or fails to discover, at the moment he requires it, the fact which lies hidden in tradition, he must not dismiss the whole realm of tradition as useless for historical purposes.

Let us freely admit that the historian is not altogether to blame for his neglect and for his ignorance of tradition as historical material. He has nothing very definite to work upon. Even the great work of Grimm is open to the criticism that it does not prove the antiquity of popular custom and belief—it merely states the proposition, and then relies for proof upon the accumulation of an enormous number of examples and the almost entire impossibility of suggesting any other origin than that of antiquity for such a mass of non-Christian material. Then the great work of Grimm, ethnographical in its methods, has never been followed up by similar work for other countries. The philosophy of folklore has taken up almost all the time of our scholars and students, and the contribution it makes to the history of the civilised races has not been made out by folklorists themselves. It does not appear to me to be difficult to make out such a claim if only scientific methods are adopted, and the solution of definite problems[Pg 8] is attempted;[8] and if too the difficulties in the way of proof are freely admitted, and where they become insuperable, the attempt at proof is frankly abandoned. I believe that every single item of folklore, every folk-tale, every tradition, every custom and superstition, has its origin in some definite fact in the history of man; but I am ready to concede that the definite fact is not always traceable, that it sometimes goes so far back as to defy recognition, that it sometimes relates to events which have no place in the after-history of peoples who have taken a position on the earth's surface, and which, in the prehistory stage, belong to humanity rather than to peoples. Folklore, too, is governed by its own laws and rules which are not the laws and rules of history. These concessions, however, do not mean the introduction of the term "impossible" to our studies. They mean rather a plea for the steady and systematic study of our material, on the ground that it has much to yield to the historian of man, and to the historians of races, of peoples, of nations, and of countries.

We cannot, however, show that this is so without facing many difficulties created for the most part by folklorists themselves. In the first place it is necessary to overtake some of the earlier conclusions of the great masters of our science. The first rush, after the discovery of the mine, led to [Pg 9]the vortex created by the school of comparative mythologists, who limited their comparison to the myths of Aryan-speaking people, who absolutely ignored the evidence of custom, rite, and belief, and who could see nothing beyond interpretations of the sun, dawn, and sky gods in the parallel stories they were the first to discover and value. We need not ignore all this work, nor need we be ungrateful to the pioneers who executed it. It was necessary that their view should be stated, and it is satisfactory that it was stated at a time early in the existence of our science, because it is possible to clear it all away, or as much of it as is necessary, without undue interference with the material of which it is composed.

The school of comparative mythologists did not, however, entirely control the early progress of the study of folklore. There was always a school who believed in the foundation of myth being derived from the facts of life. Thus Dr. Tylor, in a remarkable study of historical traditions and myths of observation,[9] long ago noted that many of the traditions current among mankind were historical in origin. Writing nearly forty years ago, he had to submit to the influence, then at its height, of Adalbert Kuhn and Max Müller, and he conceded that there were many traditions which were fictional myths. I think this concession must now be much more narrowly scrutinised, and preparation made for the conclusion that every genuine myth is a myth of observation, the observation by men in a primitive state of culture, of a fact which had struck home to their minds. The question is, to what[Pg 10] part of human history does the central fact appertain? Here is undoubtedly a most difficult problem. What the student has to do is to admit the difficulty, and to state, if necessary, that the fact preserved by tradition is not in all cases possible to discover with our present knowledge. This is a perfectly tenable position. Human imagination cannot invent anything that is outside of fact. It may, and of course too frequently does, misinterpret facts. In attempting to explain and account for such facts with insufficient knowledge, it gets far away from the truth, but this misinterpretation of fact must not be confused with the fact itself. In a word, it must be borne in mind by the student of tradition that every tradition which has assumed the form of saga, myth, or story contains two perfectly independent elements—the fact upon which it is founded, and the interpretation of the fact which its founders have attempted.

There is further than this. The other branch of traditional material, namely that relating to custom, belief, and rite, rests upon a solid basis of historic fact; customs which are strange and irrational to this age are not in consequence to be considered the mere worthless following of practices which owe their origin to accident or freak; beliefs which do not belong to the established religion are not in consequence to be considered as mere superstition; rites which were not established by authority are not in consequence to be classed as mere specimens of popular ignorance. But the difficulties in the way of getting all this accepted by the historian are many, and, again, not a few of them are the creation of the folklorist himself. Not only has he[Pg 11] neglected to classify and arrange the scattered items of custom, belief, and rite, and to ascertain the degree of association which the scattered items have with each other, but he has set about the far more difficult and complex task of comparative study without having previously prepared his material.

The historian and the folklorist are thus brought face to face with what is expected from both, in order that each may work alongside of the other, using each other's materials and conclusions at the right moment and in the right places. The folklorist has the most to do to get his results ready, and to explain and secure his position. He has been wandering about in a somewhat inconsequential fashion, bent upon finding a mythos where he should have sought for a persona or a locus, engaged in an extensive quest after parallels when he should have been preparing his own material for the process of comparative science, seeking for origins amidst human error when he should have turned to human experience. He has to change all this waywardness for systematic study, and this will lead him in the first place to disengage from the results hitherto obtained those which may be accepted and which may form the starting-point for future work. But his greatest task will be the reconsideration of former results and the rewriting of much that has been written on the wrong lines, and when this is done we shall have the historian and folklorist meeting together in the spirit which Edmund Spenser so finely and truly described three centuries ago in his treatment of Irish history: "I do herein rely upon those bards or Irish chronicles ... but unto[Pg 12] them besides I add mine own reading and out of them both together with comparison of times likewise of manners and customs, affinity of words and manner, properties of natures and uses, resemblances of rites and ceremonies, monuments of churches and tombs and many other like circumstances I do gather a likelihood of truth, not certainly affirming anything, but by conferring of times language monuments and such like I do hunt out a probability of things which I leave to your judgment to believe or refuse."[10]

I shall of course not be able to undertake either of these tasks. I shall attempt, however, to indicate their scope and importance; and as a preliminary to the consideration of the definite departments into which the subject falls, it is advisable, I think, to test the relationship of tradition to history by means of one or two illustrations. It may be that the illustrations I shall give are not accepted by all students, that some better illustration is forthcoming by further research. This is one of the drawbacks from which tradition suffers, and must suffer, until our studies are much further advanced than they are at present. But I am glad to accept this possibility of error as part of the case for the study of tradition, because the error of one student cannot be held to disqualify the whole subject. It only amounts to saying that the particular fact which seems to me to be discoverable in the examples dealt with has to be surrendered in favour of another particular fact. My conclusions may be dismissed, but that which is not dismissible is the discoverable fact, and it is only when the true fact is discovered in[Pg 13] each traditional item that previous inferences may be neglected or ignored and inquiry cease.[11]

The evidence of historic events which enter into tradition relates principally to the earliest periods, but much of it relates to periods well within the domain of history and yet reveals facts which history has either hopelessly neglected or misinterpreted. We shall find that these facts, though frequently relating to minor events, often have reference to matters of the highest national importance, and perhaps nowhere more definitely is this the case than in the legends connected with particular localities. Of one such tradition I will state what a somewhat detailed examination tells in this direction. It will, I think, serve as a good example of the kind of research that is required in each case, and it will illustrate in a rather special manner the value of these traditions to history.

The locus of the legend centres round London Bridge. The earliest written version of this legend is quoted from the MSS. of Sir Roger Twysden, who obtained it from "Sir William Dugdale, of Blyth Hall, in Warwickshire, in a letter dated 29th January,[Pg 14] 1652-3." Sir William says of it that "it was the tradition of the inhabitants as it was told me there," and Sir Roger Twysden adds of it that: "I have since learnt from others to be most true." This, therefore, is a very respectable origin for the legend, and I will transcribe it from Sir William Dugdale's letter which begins "the story of the Pedlar of Swaffham-market is in substance this":—

"That dreaming one night if he went to London he should certainly meet with a man on London Bridge which would tell him good news he was so perplext in his mind that till he set upon his journey he could have no rest; to London therefore he hasts and walk'd upon the Bridge for some hours where being espyed by a shopkeeper and asked what he wanted he answered you may well ask me that question for truly (quoth he) I am come hither upon a very vain errand and so told the story of his dream which occasioned the journey. Whereupon the shopkeeper reply'd alas good friend should I have heeded dreams I might have proved myself as very a fool as thou hast, for 'tis not long since that I dreamt that at a place called Swaffham Market in Norfolk dwells one John Chapman a pedlar who hath a tree in his backside under which is buried a pot of money. Now therefore if I should have made a journey thither to day for such hidden treasure judge you whether I should not have been counted a fool. To whom the pedlar cunningly said yes verily I will therefore return home and follow my business not heeding such dreams hence forward. But when he came home being satisfied that his dream was fulfilled he took occasion to dig in that place and accordingly found a large pot of money which he prudently conceal'd putting the pot amongst the rest of his brass. After a time it happen'd that one who came to his house and beholding the pot observed an inscription upon it which being in Latin he interpreted it that under that there was an other twice as good. Of this inscription the[Pg 15] Pedlar was before ignorant or at least minded it not but when he heard the meaning of it he said 'tis very true in the shop where I bought this pot stood another under it which was twice as big; but considering that it might tend to his further profit to dig deeper in the same place where he found that he fell again to work and discover'd such a pot as was intimated by the inscription full of old coins: notwithstanding all which he so conceal'd his wealth that the neighbours took no notice of it."[12]

Blomefield thought it "somewhat surprising to find such considerable persons as Sir William Dugdale and Sir Roger Twysden to patronise or credit such a monkish legend and tradition savouring so much of the cloister, and that the townsmen and neighbourhood should also believe it," but I think we shall have reason to congratulate ourselves that so good a folk-tale was preserved for us of this age.

The next and, it appears, an independent version, is given in the Diary of Abraham de la Pryme, under the date November 10th, 1699:—

"Constant tradition says that there lived in former times, in Soffham (Swaffham), alias Sopham, in Norfolk, a certain pedlar, who dreamed that if he went to London bridge, and stood there, he should hear very joyfull newse, which he at first sleighted, but afterwards, his dream being dubled and trebled upon him, he resolv'd to try the issue of it, and accordingly went to London, and stood on the bridge there two or three days, looking about him, but heard nothing that might yield him any comfort. At last it happen'd that a shopkeeper there, hard by, haveing noted his fruitless[Pg 16] standing, seeing that he neither sold any wares nor asked any almes, went to him and most earnestly begged to know what he wanted there, or what his business was; to which the pedlar honestly answer'd, that he had dream'd that if he came to London and stood there upon the bridg, he should hear good newse; at which the shopkeeper laught heartily, asking him if he was such a fool as to take a journey on such a silly errand, adding, 'I'll tell thee, country fellow, last night I dream'd that I was at Sopham, in Norfolk, a place utterly unknown to me, where methought behind a pedlar's house in a certain orchard, and under a great oak tree, if I digged I should find a vast treasure! Now think you,' says he, 'that I am such a fool to take such a long jorney upon me upon the instigation of a silly dream? No, no, I'm wiser. Therefore, good fellow, learn witt of me, and get you home, and mind your business.' The pedlar, observeing his words, what he had sayd he had dream'd and knowing they concenterd in him, glad of such joyfull newse went speedily home, and digged and found a prodigious great treasure, with which he grew exceeding rich, and Soffham church being for the most part fal'n down he set on workmen and reedifyd it most sumptuously, at his own charges; and to this day there is his statue therein, cut in stone, with his pack at his back, and his dogg at his heels; and his memory is also preserved by the same form or picture in most of the old glass windows, taverns, and ale-houses of that town unto this day."[13]

Now this version from Abraham de la Pryme was certainly obtained from local sources, and it shows the general popularity of the legend, together with the faithfulness of the traditional version.[14] But other[Pg 17] evidence of the traditional force of the story is to be found. Observing that De la Pryme's Diary was not printed until 1870, though certainly the MS. had been lent to antiquaries, it is curious that the following almost identical account is told in the St. James's Chronicle of November 28th, 1786:—[15]

"A Pedlar who lived many Years ago at Swaffham, in Norfolk, dreamt, that if he came up to London, and stood upon the Bridge, he should hear very joyful News; which he at first slighted, but afterwards his Dream being doubled and trebled unto him, he resolved to try the Issue of it; and accordingly to London he came, and stood on the Bridge for two or three Days, but heard nothing which might give him Comfort that the Profits of his Journey would be equal to his Pains. At last it so happened, that a Shopkeeper there, having noted his fruitless standing, seeing that he neither sold any Wares, or asked any Alms, went to him, and enquired his Business; to which the Pedlar made Answer, that being a Countryman, he had dreamt a Dream, that if he came up to London, he should hear good News: 'And art thou (said the Shopkeeper) such a Fool, to take a Journey on such a foolish Errand? Why I tell thee this—last Night I dreamt, that I was at Swaffham, in Norfolk, a Place utterly unknown to me, where, methought, behind a Pedlar's House, in a certain Orchard, under a great Oak Tree, if I digged there, I should find a mighty Mass of Treasure. Now think you, that I am so unwise, as to take so long a Journey upon me, only by the Instigation of a foolish Dream! No, no, far be such Folly from me; therefore, honest Countryman, I advise thee to make haste Home again, and do not spend thy precious Time in the Expectation of the Event of an idle Dream.' The Pedlar, who noted well his Words, glad of such joyful News, went speedily Home, and[Pg 18] digged under the Oak, where he found a very large Heap of Money; with Part of which, the Church being then lately fallen down, he very sumptuously rebuilt it; having his Statue cut therein, in Stone, with his Pack on his Back and his Dog at his Heels, which is to be seen at this Day. And his Memory is also preserved by the same Form, or Picture, on most of the Glass Windows of the Taverns and Ale-houses in that Town."

The differences in these versions are sufficient to show independent origin. The identities are sufficient to illustrate, in a rather remarkable manner, how closely the words of the tradition were always followed. It appears from the last words of the contributor to the St. James's Chronicle, who signed himself "Z," that he heard it by word of mouth about the time of his writing it down,[16] so that there is more than a hundred years between him and the Dugdale version, which was also recorded from "constant tradition."

In Glyde's Norfolk Garland (p. 69), is an account of this legend, but with a variant of one incident. The box containing the treasure had a Latin inscription on the lid, which John Chapman could not decipher. He put the lid in his window, and very soon he heard some youths turn the Latin sentence into English:—

And he went to work digging deeper than before, and found a much richer treasure than the former. Another version of this rhyme is found in Transactions[Pg 19] of the Cambridge Antiquarian Society (iii. 318) as follows:—

And both these versions are given by Blomefield.

Now if there were no other places besides Swaffham in Norfolk to which this legend is applied the interest in it would, of course, not be very great. But there are many other places, and we will first note those in Britain. The best is from Upsall, in Yorkshire, as follows:—

"Many years ago there resided, in the village of Upsall, a man who dreamed three nights successively that if he went to London Bridge he would hear of something greatly to his advantage. He went, travelling the whole distance from Upsall to London on foot; arrived there, he took his station on the bridge, where he waited until his patience was nearly exhausted, and the idea that he had acted a very foolish part began to rise in his mind. At length he was accosted by a Quaker, who kindly inquired what he was waiting there so long for? After some hesitation, he told his dreams. The Quaker laughed at his simplicity, and told him that he had had last night a very curious dream himself, which was, that if he went and dug under a certain bush in Upsall Castle, in Yorkshire, he would find a pot of gold; but he did not know where Upsall was, and inquired of the countryman if he knew, who, seeing some advantage in secrecy, pleaded ignorance of the locality, and then, thinking his business in London was completed, returned immediately home, dug beneath the bush, and there he found a pot filled with gold, and on the cover an inscription in a language which he did not understand. The pot and cover were, however, preserved at the village inn, where one day a bearded stranger like a Jew, made his appearance, saw the pot, and read the inscription on the cover, the plain English of which was—

[Pg 20] The man of Upsall hearing this resumed his spade, returned to the bush, dug deeper, and found another pot filled with gold, far more valuable than the first. Encouraged by this discovery, he dug deeper still, and found another yet more valuable.

"This is the constant tradition of the neighbourhood, and the identical bush yet exists (or did in 1860) beneath which the treasure was found; a burtree, or elder, Sambucus nigra, near the north-west corner of the ruins of the old castle."[17]

It would be tedious to go through other English versions,[18] but I must point out that it is connected with a London district. This is shown not by the actual presence of the legend, which has died out in London, but by its representation in the parish church of Lambeth. The legend so strongly current at Swaffham, in Norfolk, is represented in the church in the shape of a carving in wood of a figure to represent the pedlar, and below him the figure of what is locally called a dog.[19] A comparison of this carving with the representation of the pedlar's window formerly existing in Lambeth Church, but which was sacrilegiously removed in 1884 by the late vicar of the parish, shows much the same general characteristics, and search among the [Pg 21]parish books shows it to relate to a pedlar known by the name of Dog Smith, who left property still known by the name of the "Pedlar's Acre" to the parish.[20] All this suggests that we have here the last relics of the pedlar legend located in London.

The next stage in the history of this legend shows it to belong to the world's collection of folk-tales. There is, however, a preliminary fact of great significance to note, namely that two non-British versions refer to London Bridge. Thus a Breton tale refers to London Bridge, and the interest of this story is sufficiently great to quote it here from its recorder straight from the Breton folk:—

"Long ago, when the timbers of the most ancient of the vessels of Brest were not yet acorns, there were two men in a farmhouse in the Côtes du Nord disputing, and they were disputing about London Bridge. One said it was the most beautiful sight in the world, while the other very truly said, 'No! the grace of the good God was more beautiful still.' And as the dispute went on, 'Let us,' said one of them, 'settle it once and for all, and in this way: let us now this moment go out along the high-road and let us ask the first three men we meet as to which is the most beautiful—London Bridge or the grace of the good God? And which ever way they decide, he who holds the beaten opinion shall lose to the other all his possessions, farm and cattle and horses, everything.' So each being confident he was right, they went out: and the first man they met declared that though the grace of the good God was beautiful, London Bridge was more beautiful still; and the second the same, and the third. And the man whose opinion was beaten, a rich farmer, gave up all he had and was a beggar.

"'Now,' said he to himself when the other, taking his[Pg 22] horse by the bridle, had left him—'now let me go and see this London Bridge which is so wonderfully beautiful;' and, being very manful and stout, he set out at once to walk, and walking on and on was there by nightfall. But, good Christian that he was, he could see in it nothing to shake his belief that the grace of the good God was more beautiful still.

"Soon the bridge was silent, and the last to cross it had gone home; and he, notwithstanding his losses, tired out and sleepy, lay down and fell into a doze there; and, while he was dozing, there came by two men, and one of them, standing quite close by him, said to the other, 'The night is fine, the wind gentle, the stars clear! On such a night whoever were to collect the dew would be able to heal the blind.' 'It is true,' answered the other; 'but none know of it.' And they passed on, quietly as they had come. Thereupon up rose the beggared farmer, and with basin and cup set about collecting the dew; and in a very short time performed with it the most wonderful cures; finally curing the daughter of a neighbouring Emperor who had been blind from her birth, and whom her grateful father gave to him at once in marriage, since directly she set eyes on him she loved him."[21]

The second non-British variant, which also attaches to London Bridge, is to be found in the Heimskringla,[22] and I will quote William Morris's translation:—

"West in Valland was a man infirm so that he was a cripple and went on knees and knuckles. On a day he was abroad on the way and was asleep there. That dreamed he that a man came to him glorious of aspect and asked whither he was bound and the man named some town or [Pg 23]other. So the glorious man spoke to him: Fare then to Olaf's church the one that is in London and thou wilt be whole. Thereafter he awoke, and fared to seek Olaf's church and at last he came to London bridge and there asked the folk of the city if they knew to tell him where was Olaf's church. But they answered and said that there were many more churches there than they might wot to what man they were hallowed. But a little thereafter came a man to him who asked whither he was bound and the cripple told him. And sithence said that man: We twain shall fare both to the church of Olaf for I know the way thither. Therewith they fared over the bridge and went along the street which led to Olaf's church. But when they came to the lich gate then strode that one over the threshold of the gate but the cripple rolled in over it and straightway rose up a whole man. But when he looked around him his fellow farer was vanished."

I shall have to refer again to these Breton and Norse versions, because of their retention of London Bridge as the locale of the story, in common with all the versions which have been found in Britain. In the meantime it is to be noted that the remaining non-British variants are told of other bridges and other places. Holland, Denmark, Italy, Cairo, have their representative variants;[23] and it thus presents to the student of[Pg 24] tradition an excellent example for inquiry as to the value to history of legends world-wide in their distribution attaching themselves to historical localities.

There are some obvious features about this group of traditions, which at once lead to interesting questions. There is first the fact that all the British variants of the treasure stories centre round London Bridge; secondly, there is the extension beyond Britain to the Breton variant and the Norse variant, both non-British legends, of which the locus is London Bridge. From these two facts it is clear that London Bridge had some special influence at a period of its history which dates before the separation of the Breton folk from their Celtic brethren in Britain, for the Bretons would not after their separation acquire a London Bridge tradition; and again at a period of its history when Norse legend and saga were fashioning. In the one case the myth-makers must have been Celts of the fourth century, and the only bridge known to these Celts must have been that belonging to Roman Lundinium; in the other case the myth-makers were Norsemen, and the bridge known to them was the later bridge so frequently referred to in the chronicle accounts of the Danish and Norse invasions of England.

It is not difficult, by a joint appeal to history and folklore, to trace out from this very definite starting-point the events which brought about this particular specialisation of the world-spread treasure myths.

Obviously the first point to note is that London Bridge loomed out greatly in the minds and[Pg 25] understanding of people at two distinct periods of its history.[24] That the first period relates to its building is suggested by the date supplied by the evidence of the Breton version. The people who wondered at its building, or the results of its building, were certainly not the builders themselves, and we thus see a distinction in culture between the bridge builders and the wonder builders. This condition is exactly provided for by the building of the earliest London Bridge. It was a work of the Romans of Lundinium,[25] and the people who stood in wonder at this great enterprise were not the Roman engineers and builders, accustomed to such undertakings all over the then known world, and they must therefore have been the surrounding non-Roman people, who were the Celtic tribesmen. Now the culture-antagonism between the Romans of Lundinium and the Celts of Britain is, I believe, a factor of great importance,[26] though almost universally neglected by our historians, because they do not study the facts of early history on anthropological lines. Not only is it discoverable, as I think, from the facts of history, but the facts of tradition confirm the facts of history at all points. Thus I think it is important, if we can, to obtain independent testimony of the attitude of the surrounding people to the builders of London Bridge. We can do this by reference to the peasant beliefs[Pg 26] concerning bridges, as, for instance, in Ireland, where on passing over a bridge they invariably pulled off their hats and prayed for the soul of the builder of the bridge,[27] and to the fact that the Romans themselves looked upon bridge-building as a sacred function, and would no doubt use this part of their work to the fullest extent, in order to impress the barbarism opposed to them.[28] The extent of this impression may probably be contained in the old and widely spread nursery rhyme of "London Bridge is Broken Down," an examination of which has led Mrs. Gomme to conclude that it contains reference to an ancient belief that the building of the bridge was accompanied by human sacrifice.[29] This conclusion is confirmed by the preservation in Wales of a bridge-sacrifice tradition. It relates to the "Devil's Bridge" near Beddgelert. "Many of the ignorant people of the neighbourhood believe that this structure was formed by supernatural agency. The devil proposed to the neighbouring inhabitants that he would build them a bridge across the pass, on condition that he should have the first who went over it for his trouble. The bargain was made, and the bridge appeared in its place, but the people cheated the devil by dragging a dog to the spot and whipping him over the bridge."[30] This is a distinct trace of a substituted animal sacrifice for an original human sacrifice. But this is a practice which sends us back to the most primitive times, and in[Pg 27] particular we are referred to an exact parallel in India, where, on the governing English determining to build a bridge of engineering proportions and strength over the Hoogley River at Calcutta, the native Hindu tribesmen immediately believed that the first requirement would be a human sacrifice for the foundation.[31] The traditions attaching to London Bridge are therefore identical with the current beliefs concerning the Hoogley Bridge, and the culture-relationship of the bridge-builders to the surrounding people in both cases is that of an advanced civilisation to tribesmen. Now if these conditions of modern India are repetitions of the conditions of ancient Britain in the days of Lundinium, and of this there can be but little doubt, there is no difficulty in understanding to what part of history these traditions have led us. We are again in the days when London Bridge was a marvel—a marvel which sent travelling through the Celtic homes of Britain a new application of the treasure myth which they had inherited from remote ancestors. The marvel lived on through the ages when London was in the unique position of being an undestroyed city in Saxon times,[Pg 28] times which witnessed the destruction of all other cities of Roman foundation,[32] and the sending forth of the Celtic refugees to Brittany.[33] The accumulation during a long-continuing period of conceptions of treasure being found by way of the bridge leading to London, would become the direct force for keeping the tradition alive; and while the facts of history show us the important position of London during the period which witnessed the departure of the Celtic Bretons to their continental home,[34] the facts of tradition show us the Celtic tribesmen deeming it a way to wealth through the magic potency of dreamland. The Celtic tribesmen stood outside Roman Lundinium. Its life was not their life, and their conversion of its position into a mythic treasure house or a mythic road to treasure, and their association of it with the bloody rites of the foundation sacrifice, are in strict accord with the historical relationship of the tribal life of Celtic Britain to the city life of Roman Lundinium.

I may be permitted perhaps to emphasise this significant accordance of history and tradition when working together. I have already alluded to the fact that I have worked out the history of London independently, and upon lines quite different from the present study.[Pg 29] I have therefore a wider grasp of the two currents of history and folklore in this particular case than could in the ordinary way fall either to the historian or to the folklorist. That I can find in both just the complementary facts which help to realise the whole situation, to fill in the gaps of history which nowhere directly tells of the relationship of Roman Lundinium to the British Celts, to extend the outlook of folklore which nowhere recognises that there was a great Roman city of Lundinium which would dominate the minds of those not trained to city life, is a fortunate circumstance which neither historian nor folklorist is likely to repeat frequently, and I am entitled, I think, to claim the utmost from it. I can at least claim that it answers all the facts in a way that has not yet been accomplished. Thus Sir John Rhys has discussed the treasure legend and he can only account for it as part of the mythical trappings of Arthur into which "London Bridge is introduced," because London Bridge "formerly loomed very large in the popular imagination as one of the chief wonders of London." Sir John Rhys refers for confirmation of this to the "notion cherished as to London and London Bridge by the country people of Wales even within my own memory," and then goes on to say that "the fashion of selecting London Bridge as the opening scene of a treasure legend had been set perhaps by a widely spread English story," that of the Pedlar of Swaffham.[35] All this is very unsatisfactory. Modern notions of this sort would not set the fashion[Pg 30] two centuries ago, nor extend it to Brittany. Nor is the suggestion in accord with other evidence as to the extension of tradition. What has happened is that the Arthur cycle has appropriated two London Bridge traditions and has worked them up into the Arthur form, the traditions themselves belonging to the far older period to which I have here referred them—a period when the burial of treasure was a necessary corollary to the events which were happening.[36] Buried treasure legends are found all over the country. They belong to the period of conquest and fighting. They are the evidence which tradition yields of the unrest of the times which caused them to arise. They are the fragments of history which tradition has preserved, while history has coldly passed them by.[37]

[Pg 31] With this in the background as the corpus of a legend-covered London Bridge, we come to the second period.

[Pg 32] London Bridge to the Norsemen of the tenth and eleventh centuries was a place of fierce fighting and struggle, a place of victory and death. The saga takes pains to describe this wondrous bridge[38] before it describes the great fight there and its capture by King Olaf, a fight which produced a war-rhyme which, in Laing's version, begins with the same words as the English nursery rhyme, "London Bridge is broken down!"[39] and which Morris renders as a tribute to King Olaf, "thou brakest down London Bridge." There is little wonder, then, that the men of King Olaf took back with them to saga-land a great memory of this bridge and this fight, transferred to it their own variant of the world-wide treasure legend, and made a legend not of money treasure, but of regained health to a crippled warrior. The corresponding non-British version of Brittany helps us to understand that the cure of disease was originally associated with the gains of treasure, and in the Norse version the treasure incident is altogether dropped, but in its place is the recovery of health, a treasure more in accord with the sterner needs and recollections of a great fight. The Norse story is helpful to us as showing how London Bridge could enter into the legends of a people, and remain with them even after that people was no longer living in Britain, and it becomes therefore a valuable addition to the evidence for the more ancient transference from Britain to Brittany of the original legend.

Altogether the piecing together of the items of historical value in this legend is most complete. We have[Pg 33] not only recovered for history hitherto lost conceptions of the place held by Roman Lundinium among the Celtic tribesmen, but we have recovered also evidence of the true culture-position of the Celtic tribesmen towards their Roman conquerors. The examination of this legend may have been long and tedious, but the result is, I think, commensurate. It illustrates the power of tradition to set historical data in their proper environment, to restore the proportion which they bear to unrecorded history, and if the student will but follow the evidence carefully, I think he will find these results.

We will take a step forward, and turn from local to personal attachments of tradition. There is a whole class of traditions attached to personages about whose historical existence there can be but little doubt, and just because of the accretion of tradition round them their historical existence has oftentimes been denied. The most famous example in our history is of course King Arthur, and so great an authority as Sir John Rhys is obliged to resort to a special argument to account for the problems he is faced with. He argues, and argues strongly, for an historic Arthur—an Arthur who was the British successor of the Roman emperor after Britain had ceased to be a part of the Roman Empire.[40] But because of the myths which have grown round him, he suggests that there must also have been "a Brythonic divinity named Arthur," and we are thus introduced to a dual study of history and myth which does not appear to me to take us very far, and which,[Pg 34] in fact, just separates history from myth, instead of showing where they join hands. This dual conception of myth is indeed a rather favourite resort of those scholars who cannot appreciate the evidence that proves a character in a mythic tradition to be an actual historical personage. It is the basis of the famous Sigfried-Arminius controversy. It does duty in many less important cases,[41] and most frequently in connection with northern mythology, where the line between mythic and historical events gathering round a hero is generally so finely drawn as to be almost imperceptible. But it is so obviously a piece of special pleading on self-created lines that other explanation is needed. And another explanation is to be obtained if only students will rely upon the evidence of tradition itself instead of appealing to every fancy derived from sources which have nothing to do with tradition.

The history of King Arthur has been the subject of inquiry too frequently for it to be possible in these pages to discuss the dual theory as it has been applied to him, but I will attempt to show that it is quite unnecessary thus to explain the history of King Arthur by turning to the history of another of our great heroic figures, one of the greatest to my mind, who, like Arthur, has secured not only a fair share of special tradition belonging to himself personally, but a larger[Pg 35] share than others of that corpus of tradition which has descended from our earliest unknown ancestors, and become attached to the historical hero of later times—I mean, Hereward, the last of the Saxon defenders of his land against William the Norman.[42] The analysis of the Hereward legend affords a good example of the process by which tradition is preserved by historical fact, and in its turn helps to unravel the real history which lies at the source. Instead, therefore, of attempting to travel over the voluminous literature which is the outcome of the King Arthur story, I will use for the same purpose the shorter story of Hereward the Englishman.

We start with the fact that Hereward is unknown to history until his great stand in the Island of Ely against the might of William, the conqueror of England. And yet to the banners of this "unknown" chieftain there flocked the discontented heroism of England, men ranking from the noble to the peasant, and including such great figures as Morcar, Edwine, and Waltheof. I always think, too, that the little band of Berkshire men, who started across the country to join Hereward in the fens, and were intercepted and cut to pieces by a Norman troop,[43] give us more than a passing glimpse at the estimation in which Hereward was held by his countrymen. Such a man commanding so much, in face of so much, could not have been the unknown person which history makes him.

How then can we ascertain why he was held in such[Pg 36] estimation? History being quite silent, tradition steps into the gap. It is the tradition recorded in post-Herewardian times, be it noted. In this great body of tradition, contained in a Latin MS. of the twelfth century, he journeys to Scotland, where he slew a bear and saved the people whom it had oppressed; from thence to Cornwall, where he fought and slew a great champion, the lover of the princess; from thence to Ireland, where he assisted the King in war, and back again to Cornwall to rescue again the princess from a distasteful wooer, and, finally, to Flanders. Even in the camp of the Norman, which he visits in traditional fashion, he has an adventure with witches which takes us to the worship of wells. Much of his adventure is but the application of well-known traditional events,[44] and it is important to note that the geography of the supposed travels belongs to the very home of tradition, the unknown territories of the Celts, Ireland, Cornwall, and Scotland.

Now all this tradition is certainly not true of Hereward. But what it does is to certify to his greatness in the eyes of his countrymen, to show that his countrymen were anxious to explain why he was so great in A.D. 1070, and why before that date he was unknown to them. This is an important point to have gained. It shows the vacuum which was occupied by tradition because contemporary, or nearly contemporary, thought required it to be filled up. The[Pg 37] popular mind abhors a vacuum as much as the material world of nature does. It will fill it with its own conceptions, if it cannot fill it with recognised facts. Hereward must have been a famous man when he took his stand in the fens of Ely. That his biographers explain his fame by the application of ancient traditions is only saying that his countrymen reckoned his fame as of the very highest; ordinary current events of the day would not suit their ideas of the fitness of things. Hereward was as Alfred had been, as Arthur had been, and so he must have his share of the national tradition, even as these heroes had. To say less of him was to have put him below the others. And history in this case could not help, for it was in the hands of Hereward's enemies, and they were careful to say nothing or very little of English heroes at this period. The great battle of Hastings had been lost, but of all the English men who had fought and died there we only know of three names beyond those of the king and his house. Leofric the abbot of Peterborough, Godric the sheriff of Berkshire, and Asgar the sheriff of London, have become known by accident, as it were. All others are unnamed and unhonoured. Therefore, when the great deeds of Hereward came to be chronicled, it was not enough to say he was at Hastings; the deeds of old must be chronicled of him as they had been chronicled of others.

This accretion of popular tradition to account for the fame of Hereward when he took command at Ely, though it proclaims in the strongest terms that Hereward was famous in the eyes of his countrymen, displaces history therefore. Putting the case in this way,[Pg 38] we may proceed to examine what recorded history exactly has to say of Hereward, and then by noting what it has left unsaid, we may perhaps be able to fill the gap by a reasonable deduction from the facts. In Domesday there are clearly two Herewards, one having lands in Lincolnshire in the time of King Edward and not at the date of the survey, the other having lands in Warwickshire in the time of King Edward and also at the date of the survey. Here we have two widely different counties and two widely different conditions, and it is right with all the evidence to conclude that they relate to different personages. The Lincolnshire Hereward is the hero of the fens. He held of the abbot of Peterborough, and Ulfcytil, who was appointed in 1062, was the abbot in question. This brings us to only four years before the battle of Hastings, and another entry in Domesday, thanks to the scholarship of Mr. Round, proves that Hereward was deprived of his Lincolnshire lands not before but after the great fights at Hastings and in the fens. Therefore the story shapes itself somewhat in this fashion. Hereward was in England in 1062. He was then a man of the abbot of Peterborough; that is to say, a tenant bound to perform military service to his lord. His lord, the abbot, was at Hastings with his tenants, and fought there. That Hereward of all the abbot's tenants should have followed his lord to Hastings is more than likely; the strange thing would be that he should not have done so. That going thither nameless among the many, he should gain experience under Harold, though no fame has come to him through the historians from a field where Saxon[Pg 39] fame was buried; that his own genius should make him use his experience when need arose; that among the English all survivors from that field who were still unwilling to bow the knee to William would be reckoned as heroes by their depressed countrymen; that on this account alone he would be given rank above Morcar, who had kept away from Hastings—are the conclusions to be drawn legitimately from the silence as well as the actual records of history, compared with the story told by tradition. History and tradition are in accord, not in conflict; the gaps of history are filled by tradition—that tradition which was suitable and worthy of so great a hero, namely the ancient tradition told of all heroes. Reopening these gaps and putting in its right place the tradition which had hitherto prevented them from being seen, we are able to appeal to history to yield up the true story of one of the greatest of English heroes, a story which shows him to have been at Hastings by the side of Harold, to have won fame there, to have continued the fight for English liberty as leader of the English patriots, and to have earned a place in the unsung English epic.

But his place in English tradition helps us to understand the value and position of tradition in such cases. The traditions clustering round the name of Hereward do not compel us to interpret them as Hereward facts. The historian, however, need not on this account fear for Hereward. He should rather value the traditions as evidence of the greatness of the English hero among the conquered English. They applied to him the legends of their oldest heroes. All that was delightful[Pg 40] to them in tradition was attached to their present hero. He was worthy of a place among their greatest. And thus the fact of added tradition brings out the estimate of the worth of the hero to those among whom he lived and for whom he fought.

The traditions themselves belong to far other times, and the facts contained in them must be interpreted from the oldest ideas of our race. It is only by thus disengaging the traditions which have grown round the historical person that the correct interpretation of the position can be attempted, and when that is done we are left, not with a mass of uncertain and misleading testimony about a national hero, but with certain definite historical facts belonging to Hereward, and certain traditions attached to Hereward, certifying to his great place in the popular estimation, telling of facts which do not, it is true, belong to Hereward, but which, in a special sense, belong to the people who were reverencing Hereward.

If I have made it clear from these examples that the explanation of historic fact and mythic tradition in combination does not lead either to the discrediting of history or to the creation of new mythic realms, I need not dwell much longer on this class of illustrations of the relationship between history and tradition. Over and over again, in the local records, are examples to be found where history is in close contact with tradition, and I am far more inclined to question the evidence which proves the falseness of any authenticated tradition than I am to trust all the statements which do duty for history. It is not only the traditions looming largely in popular interest, but some of the smallest local[Pg 41] traditions which throw light on great historical events. They may tell us not merely of the great historical event, but of the peculiar relationship of parts of the kingdom to that event, which no purely historical evidence could by any possibility explain. One of the most striking examples is, perhaps, the Sussex tradition of "Duke" William as a conqueror.[45] The title Duke is here faithfully recorded of the great conqueror, who everywhere else in England, both in historical documents and in the popular language, is referred to as king. The explanation is, if the identification of this tradition with the great Norman king is correct, that Sussex being more or less separated from the rest of the country by its great weald, carried its own tradition of the bloody field at Hastings sufficiently long and uninterrupted for it to be stamped upon the minds of the people in its original form, and thus to remain. No better evidence could be found for the relationship of Sussex to this great event. All the chapters in Mr. Freeman's great history do not impress the imagination so strongly as this one fact, that William the Conqueror has always been Duke William to the Sussex folk. He was Duke William to the fen folk, too. They fought for their belief and were compelled to accept his kingship. The Sussex folk fought, too, and they handed down their conception of the great fight to their children.

A good example of a slightly different kind occurs in connection with Kett's rebellion in Norfolk. It was associated with a prophecy that said, "there shulde lande at Walborne hope the proudest prince of Christendome, and so shall come to Moshold heethe,[Pg 42] and there shuld mete with other ij kinges, and shall fyght and shalbe put down: and the whyte lyon shuld optayne" the mastery. And yet this prophecy goes much further back, for the Danes are said to have landed at Weybourne Hope in their invasions, and the old rhyme is still remembered in the county:—

This is an example of the forcible revival of an ancient tradition to suit a later fact, and is evidence of the enormous impression which the event to which it refers had upon the locality. Kett's rebellion was one thing to the nation at large and quite another thing to this district of Norfolk, and the great events of the tenth century preserved in legend were equated with the minor events of the sixteenth century, thus enabling us to understand better the depth of the local feeling which produced these events.