The Project Gutenberg EBook of Strain, by L. Ron Hubbard This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook. Title: Strain Author: L. Ron Hubbard Release Date: February 21, 2020 [EBook #61474] Language: English Character set encoding: ASCII *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK STRAIN *** Produced by Greg Weeks, Mary Meehan and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

The essence of military success is teamwork—the

essence of that is absolute reliability of every

man, every unit of the team, under any strain that

may be imposed. And the duty of a good general—?

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Astounding Science-Fiction April 1942.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

It was unreasonable, he told himself, to feel no agony of apprehension. He was in the vortex of a time whirlwind and here all stood precariously upon the edge of disaster, but stood quietly, waiting and unbreathing.

No man who had survived a crash, survived bullets, survived the paralyzing rays of the guards, had a right to be calm. And it was not like him to be calm; his slender hands and even, delicate features were those of an aristocrat, those of a sensitive thoroughbred whose nerves coursed on the surface, whose health depended upon the quietness of those nerves.

They threw him into the domed room, and his space boots rang upon the metal floor, and the glare of savage lights bit into his skull scarcely less than the impact from the eyes of the enemy intelligence officer.

The identification papers were pushed across the desk by this guard and the intelligence officer scanned them. "Hm-m-m." The brutish, Saturnian countenance lighted and became interested. The slitted eyes flicked with satisfaction from one to the other of the two captured officers.

"Captain Forrester de Wolf," said the man behind the desk. "Which one of you?"

He looked steadily at the Saturnian and was a little amazed to find himself still calm. "I am he."

"Ah! Then you are Flight Officer Morrison?"

The captain's companion was sweating and his voice had a tremor in it. His youthful, not too bright face twitched. "You got no right to do anything to us. We are prisoners of war captured in uniform in line of combat duty! We treat Saturnians well enough when we grab them!"

This speech or perhaps its undertone of panic was of great satisfaction to the intelligence officer. He stood up with irony in his bearing and shook Captain de Wolf by the hand. Then, less politely but with more interest, bowed slightly to Flight Officer Morrison. The intelligence officer sat down.

"Ah, yes," he said, looking at the papers. "Fortunes of war. You came down into range of the batteries and—well, you came down. You gentlemen don't accuse the Saturnians of a lack in knowing the rules of war, I trust." But there was false candor there. "We will give you every courtesy as captured officers: your pay until the end of the war, suitable quarters, servants, good food, access to entertainment and a right to look after your less fortunate enlisted captives." There was no end to the statement. It hung there, waiting for an additional qualification. And then the intelligence officer looked at them quickly, falsely, and said, "Of course, that is contingent upon your willingness to give us certain information."

Flight Officer Morrison licked overly dry lips. He was young. He had heard many stories about the treatment, even the torture, the Saturnians gave their prisoners. And he knew that as a staff officer the Saturnians would know his inadvertent possession of the battle plan so all-important to this campaign. Morrison flicked a scared glance at his captain and then tried to assume a blustering attitude.

Captain de Wolf spoke calmly—a little surprised at himself that he could be so calm in the knowledge that as aide to General Balantine he knew far more than was good to know.

"I am afraid," said the captain quietly, "that we know nothing of any use to you."

The intelligence officer smiled and read the papers again. "On the contrary, my dear captain, I think you know a great deal. It was not clever of you to wear that staff aiguillette on a reconnaissance patrol. It was not clever of you to suppose that merely because we had never succeeded in forcing down a G-434 such as yours that it could not be done. And it is not at all clever of you to suppose that we have no knowledge of a pending attack, a very broad attack. We have that knowledge. We must know more." His smile was ingratiating. "And you, naturally, will tell us."

"You go to hell!" said Flight Officer Morrison, hysteria lurking behind his eyes.

"Now, now, do not be so hasty, gentlemen," said the intelligence officer. "Sit down and smoke a cigarette with me and settle this thing."

Neither officer made a move toward the indicated chairs. Through Morrison's mind coursed the crude atrocity stories which had been circulated among the troops of Earth, stories which concerned Earth soldiers lashed to ant hills and honey injected into their wounds, stories which dealt with a courier skinned alive, square inch by square inch, stories about a man staked out, eyelids cut away, to be let go mad in the blaze of Mercurian noon.

Captain de Wolf was detached in a dull and disinterested way, standing back some feet from himself and watching the clever young staff captain emotionlessly regard the sly Saturnian.

The intelligence officer looked from one to the other. He was a good intelligence officer. He knew faces, could feel emotions telepathically, and he knew exactly what information he must get. The flight officer could be broken. It might take several hours and several persuasive instruments, but he could be broken. The staff captain could not be broken, but because he was an intelligent, sensitive man he could be driven to the brink of madness, his mind could be warped and the information could thus be extracted. It was too bad to have to resort to these expedients. It was not exactly a gentlemanly way of conducting a war. But there were necessities which knew no rules, and there was a Saturnian general staff which did not now believe in anything resembling humanity.

"Gentlemen," said the intelligence officer, looking at his cigarette and then at his long, sharp nails, "we have no wish to break your bodies, wreck your minds and discard you. That is useless. You are already beaten. The extraction of information is, with us, a science. I do not threaten. But unless we learn what we wish to learn we must proceed. Now, why don't you tell me all about it here and now and save us this uncomfortable and regrettable necessity?" He knew men. He knew Earthmen. He knew the temper of an officer of the United States of Earth, and he did not expect them to do anything but what they did—stiffen up, become hostile and angry. But this was the first step. This was the implanting of the seed of concern. He knew just how far he could go. He smiled at them.

"You," he continued, "are young. Women doubtless love you. Your lives lay far ahead of you. It is not so bad to be an honored prisoner, truly. Why court the possibility of broken bodies, broken minds, warped and twisted spirits? There is nothing worth that. Your loyalty lies to yourselves, primarily. A state does not own a man. Now, what have you to say?"

Flight Officer Morrison glanced at his captain. He looked back at the intelligence officer. "Go to hell," he said.

There were no blankets or bunks in the cell and there was no light save when the guard came, and then there was a blinding torrent of it. The walls sloped toward the center and there was no flat floor but a rounded continuation of the walls. The entire place was built of especially heat-conductive metal and the two prisoners had been stripped of all their clothes.

Captain de Wolf sat in the freezing ink and tried to keep as much of himself as possible from contacting the metal. For some hours a water drop had been falling somewhere on something tinny, and it did not fall with regularity; sometimes there were three splashes in rapid succession and then none for ten seconds, twenty seconds or even for a minute. The body would build itself up to the next drop, would relax only when it had fallen, would build up for the expected interval and then wait, wait, wait and finally slack down in the thought that it would come no longer. Suddenly the drop would fall—a very small sound to react so shatteringly upon the nerves.

The captain was trying to keep his thoughts in a logical, regulation pattern despite the weariness which assailed him, despite the shock of chill which racked him every time he forgot and relaxed against the metal. How hot was this foul air! How cold was this wall!

The walls were icy; the air was baking-hot and Sahara-dry and foul. They waited—waited for Saturn's inquisitioners—

"Forrester," groped Morrison's voice.

"Hello"—startling himself with the loudness of his tone.

"Do—Is it possible they'll keep us here forever?"

"I don't think so," said the captain. "After all, our information won't be any good in any length of time. If you are hoping for action, I think you'll get it."

"Is ... is this good sense to hold out?"

"Listen to me," said the captain. "You've been in the service long enough to know that if one man fails he is liable to take the regiment along with him. If we fail, we'll take the entire army. Remember that. We can't let General Balantine down. We can't let our brother officers down. We can't let the troops down. And we can't let ourselves down. Make up your mind to keep your mouth shut and you'll feel better."

It sounded, thought the captain, horribly melodramatic. But he continued: "You haven't had the grind of West Point. A company, a regiment or an army has no thought of the individual. It cannot have any thought, and the individual, therefore, cannot fail, being a vital part of the larger body. If either of us break now, it would be like a man's heart stopping. We're unlucky enough to be that heart at the moment."

"I've heard," said Morrison in a gruesome attempt at jocularity, "that getting gutted is comfortable compared to some of the things these Saturnians can think up."

The captain wished he could believe fully the trite remark he must offer here. "Anything they can do to us won't be half of what we'd feel in ourselves if we did talk."

"Sure," agreed Morrison. "Sure, I see that." But he had agreed too swiftly.

The shock of the light was physical and even the captain cowered away from it and threw a hand across his eyes. There was a clatter and a slither and a tray lay in the middle of the cell, having come from an unseen hand at the bottom of the door.

Morrison squinted at it with a glad grin. There were several little dishes sitting around a big metal cover of the type used to keep food warm. Morrison snatched at the cover and whipped it off. And then, cover still raised, he stared.

On the platter a cat was lying, agony and appeal in its eyes, crucified to a wooden slab with forks through its paws, cockroaches crawling and eating at its skinned side.

The cover dropped with a clatter and was then snatched up. The heavy edge of it came down on the skull of the cat, and with a sound between a sigh and a scream it relaxed, dead.

Gray-faced Morrison put the cover back on the dish. The captain looked at the flight officer and tried to keep his attention upon Morrison's reaction and thus avoid the illness which fought upward within him.

The light went out and they could feel each other staring into the dark, could feel each other's thoughts. From the captain came the compulsion to silence; from Morrison, a struggling but unspoken panic.

One sentence ran through Captain de Wolf's mind, over and over. "He is going to break at the first chance he has. He is going to break at the first chance he has. He is going to break at the first chance he has. He is—"

Angrily he broke the chain. How could he tell this man what it would mean. Himself a Point officer, it was hard for him to reach out and understand the reaction of one who had been until recently a civilian pilot. How could he harden in an hour or a day the resolution to loyalty?

It was a step ahead, a tribute to De Wolf's understanding that he realized the difference between them. He knew how carefully belief in service had been built within himself and he knew how vital was that belief. But how could he make Morrison know that fifty thousand Earthmen, his friends, the hope of Earth, might die if the time and plan of the attack were disclosed?

Futilely he wished that they had not been at the council which had decided it, that knowledge of it had been necessary for them to do a complete scout of the situation for General Balantine. If no word of this came to the Saturnians, then this planet might be wholly cleared of the enemy with one lightning blow by space and land.

Suddenly De Wolf discovered that he had been wondering for a long time about his daughter, who had been reported by his wife as having a case of measles. Angrily he yanked his mind from such a fatal course. He could not allow himself to be human, to know that people would sorrow if he went. He was part of an army and as part of that army he had no right to personality or self. He was here, he could not fail, he could not let Morrison fail!

If only that drop would stop falling!

It was both relief and agony when the light went on once more. The captain had no conception of the amount of time which had passed, was only conscious of the misery of his body and the determination not to fail.

The door swung open and a dark-hooded Saturnian infantryman stood there. An officer beyond him beckoned and said, "We want a word with Morrison, the flight officer, if you please."

Not until Morrison had been gone an hour or more did Captain de Wolf begin to crumble within. The irregular, loud drop, the continued shocks of a body sweating in the hot air and then touching the icy metal, the fact that Morrison—

The man was not a regular; he was a civilian less than a year in the service. Unlike Captain de Wolf, he was not a personality molded into a military machine, and a civilian, having earned a personality of his own through the necessity to seek for self, could not be drawn too far down the road of agony without breaking.

Captain de Wolf, sick with physical and nervous discomfort, was ground down further by his fear that Morrison would crack. And as time went by and Morrison was not returned, De Wolf became convinced.

Surging up at last, he battered at the door. No answer came to him; the lock was steadfast. Wildly he turned and beat at the plates of the cell, and not until pain reached his consciousness from his bloodied fists did he realize the danger in which he stood. He himself was cracking. He stilled the will to scream at the dropping water. He carefully took himself in hand and felt the light die in his eyes.

He had no hope of escape. The Saturnians would be too clever for that. But he could no longer trust himself to wait, and he used his time by examining the whole of this cell. The walls were huge, unyielding plates and there was no window; but, passing back and forth, he repeatedly felt the roughness of a grate underfoot. This he finally investigated, a gesture more than a hope. For this served as the room's only plumbing and was foul and odorous and could lead nowhere save into a sewage pipe.

For the space of several loud and shattering drops De Wolf stood crouched, loose grate in hand, filled with disbelief. For there was a faint ray of light reflected from somewhere below, and in that light it could be seen that there was room enough to pass through!

Suddenly crafty, he listened at the door. Then, with quick, sure motions, slid into the foul hole and pulled the grate into place over his head. The light, not yet seen, was beckoning to him at the end of a tunnel in which he could just crouch.

He crawled in the muck for two hundred feet before he came to the light, and here he stopped, staring upward. The hope in him flickered, waned and nearly vanished in a tidal wave of despair. For the light came from an upper grate fourteen feet above the floor of the tunnel, far out of reach upon a slimy, unflawed wall. He tried to leap for it and fell back, slipping and cruelly banging his head as he dropped.

Again he took solid hold of himself. He forced his trained mind to think, forced his trained body to obey. He stood a long way back from himself and critically observed his actions and impulses as though he was something besides a man and the man was on parade.

He looked farther along the tunnel and fumbled his way away from the light. He was sure he would have another outlet presented to him by fate. He could not be led this far without some recompense. And he felt in the top of the tunnel for a grate which might lead out through an empty cell. The tunnel curved and then a new sound made him fumble before he took another step. There was a drop there, an emptiness which might extend ten feet or a hundred. He had to return or chance it.

The water which sluggishly gurgled about his ankles spilled over the soft lip of the hole and dropped soundlessly. Suddenly he was filled with sickness and panic and premonition. This foul trap into which he had ventured hemmed him close, imprisoned him, would embrace him for some awesome purpose and never give him up.

He forced himself into line. He froze his terror. He dropped blindly over the lip of the hole.

He was not shaken, for he had dropped less than six feet and the bottom was soft. He crouched, his emotions clashing, disgust and relief. And then when he looked about him again he felt the mad surge of hope, for there was light ahead!

Floundering and splashing and steadying himself against the walls, he gained the bend and saw the blinding force of daylight. For some little while he could not look directly at it nor could his wits embrace the whole of the promise that light offered. But at last, when his pupils were contracted to normal and his realization distilled into reason, he went forward and looked down. Once more his hope died. Here was a sheer drop of nearly a hundred feet, a cliff face which offered no slightest hold, greased by the sewage and worn smooth by the water.

Clinging forlornly to the edge, he scanned the great dome of the military base a mile overhead, scanned the cluster of metal huts on the plain before him, watched far-off dots which were soldiers. There was a roar overhead and he drew back lest he be seen by the small scout plane which cruised beneath the dome. When its sound had faded he again ventured a glance out, looking up to make sure he was not seen from above. And once more hope flared.

For the wall above this opening offered grips in the form of projecting stones, and the climb was less than twenty feet!

It was difficult to swing out of the opening and grab the first rock. It took courage to so expose himself to the sentries who, though two thousand yards away, could pick him easily off the wall if they noticed him.

The rock he grabbed came loose in his hand and he nearly hurtled down the cliff. He crouched, panting, denied, wearied beyond endurance with the sudden shock of it. And then he stood off from himself again and snarled a command to go on and up.

The next rock he trusted held, and in a moment he was glued to the face of the sheer wall, making weary muscles respond to orders. Why he was tired he did not understand, for he had done no great amount of physical exertion. But rock by rock, as he went up, his energy flooded from him and left him in a hazed realm of semiconsciousness which threatened uncaring surrender. He rested for longer and longer intervals between lifts, and what had been twenty feet seemed to stretch to a tortured infinity.

He could not believe that he had come within two feet of the top; but, staring up, he saw that he should believe it. A savage will took hold of him and he reached out for the next handhold. It did not exist.

He fumbled and groped across the smooth face above him. He stretched to reach the lip so near him. And then he realized that, near as he was, he could not go farther. Already his bleeding hands refused to hold beyond the next few seconds. A foot slipped and in sweating terror he wildly clawed for his hold.

His right hand slipped loose. A red haze of strain covered his vision. One foot came free and the tendons of his right arm were stretched to the snapping point. He knew he was going, knew that he would fall, knew that Morrison would sell an army to the gods of slaughter—His right hand numbed and lost its grip and he started to fall.

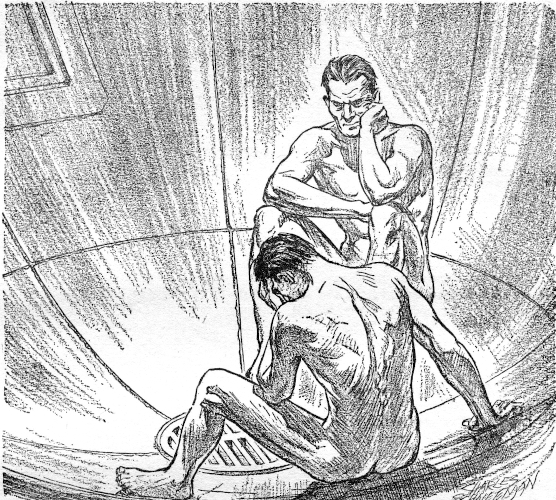

There was a wrench which tore muscles and nerves, and something was around his wrist. He was not falling. He was dangling over emptiness and something had him from above!

They pulled him up over the edge and dropped him in an exhausted, broken huddle upon the gravel of the small plateau. And at last, when he opened his eyes, it was to see the grinning face of the intelligence officer and the stolid guards.

"Usually," said the intelligence officer, in an offhand voice, "they make it up and over by tearing a grip out of the cliff with their fingernails. You, however, are of a much more delicate nervous structure, it seems. I rather thought you'd fail where you did. One gets to know these things after some practice."

Captain de Wolf lay where they had dropped him. A dull haze of beaten anger clouded his sight and then dropped away from him and left him naked, filthy and alone among his country's enemies.

Diffidently the guards picked him up and lugged him toward the small buildings. They took him down a corridor and into a large, strange room. Glad to be quit of this, they put him in a chair and strapped his wrists down. Captain de Wolf made no resistance. He did not look up.

The intelligence officer walked gracefully back and forth, slowly touring the room. He stopped and lighted a cigarette. "It was really quite useless, that escape of yours," he said. "Your friend Morrison talked to the limit of his knowledge. He gave us troops, divisions to be used, state of equipment, general battle plan, in fact everything but two small facts which he did not know." He came nearer to De Wolf. "He was not able to recall the time of the attack or the assembly point after it had succeeded—if it did succeed. You are to give us that data, for, as a staff officer, you, of course, know. Brauls! Make ready with No. 4!"

Captain de Wolf tried to rally. He tried to feel rage against Morrison. He tried to realize that an army would perish because of this day's work. He could not think, could not feel. They were rolling some kind of machine toward him, and the wriggly thing called Brauls was adjusting something on it. "I won't tell you anything," said De Wolf leadenly.

A dog was pulled out of a cage and placed on a table where it was strapped down. It whimpered and tried to lick at the hand of the soldier who did the work. Brauls, face hidden in a hood, worked expertly with a little track. On this was a small car having two high sides and neither back nor front; it ran on a little track which had been widened to accommodate the width of the dog.

Brauls touched a button and from jets on either side of the car small streams shot forth with sudden ferocity. These jets sprayed water under tremendous hydraulic pressure, jets which would cut wood faster than any saw and which hissed hungrily as they began to roll toward the dog.

Captain de Wolf tried to drop his eyes. He could not. The little car crept up on the dog and then the jets began to carve away, a fraction of an inch at a time—De Wolf managed to look away. The shrieks of agony which came from the dog carved through De Wolf.

"I won't tell you anything," he said.

They stretched out his arm and fixed the track on either side of it. They started the car toward his outstretched hand. Fixedly he watched it coming.

To the persuasive drawl of the intelligence officer he said, "I won't tell you anything."

A few hours later the intelligence officer was making out his report. He stopped after he had written the caption and the date and gazed at his long, sharp fingernails stained with nicotine. Then he sighed and resumed his writing.

INTELLIGENCE REPORT

Base 34D Mercury

Adsama 452

Today interrogated two officers captured from Earth reconnaissance plane, Captain Forrester de Wolf and Flight Officer Morrison.

Captain de Wolf, under procedure twenty-three escape tactic, revealed nothing. Later he was given procedures forty-five, ninety-seven, twenty-one and six. He died without talking.

Flight Officer Morrison was taken from the cell to the chamber. He was very combative. Procedures forty-five, ninety-seven and six were employed. Despite state of subject he was able to get at the automatic of a guard in a moment of carelessness and succeeded in retaining it even after he was shot. Rather than risk the divulgence of data, Flight Officer Morrison blew out his brains. The guard is under arrest.

From this attempt and the stubbornness of the enemy I conclude that there may be some attack in the making but, as our own scouts have discovered nothing, I do not expect it in this quarter for some time.

Drau Shadma

Captain, Saturnian Imperials

Intelligence

At headquarters of the Third Space Army, United States of Earth, General Balantine sat massively at his field desk impatiently going through a sheaf of reports.

"Belts!" he brayed at an aide. "Tell Colonel Strawn that whether he thinks regulation hold-down belts are useless or not his troops will wear them and parade with them!"

"Yessir," said the aide timidly. He had a report in his hand and was not very anxious to give it.

"Well?" said General Balantine sharply. "What have you there?"

"It's a report, sir. Captain de Wolf and Flight Officer Morrison are missing on reconnaissance. They are unreported for a day and a half."

"Morrison? De Wolf? Oh, yes, De Wolf." General Balantine was perfectly silent for a moment. Then, in an altered tone: "Morrison ... Morrison. I don't know the man. I ... don't ... know—" He was silent again, so that his abrupt return to activity was the more startling.

"Post an order for a council of officers. And have another aide appointed to me. Dammit, that was a neat plan of attack, too."

"You're changing the plan, sir?"

General Balantine snorted. "They'll wear those hold-down safety belts. I'll change that plan of attack. I don't know—can't know—what the Saturnians found out. I don't think De Wolf ... but it makes no difference. I'd have to know and that's impossible. There's time to change. Post that notice."

End of the Project Gutenberg EBook of Strain, by L. Ron Hubbard

*** END OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK STRAIN ***

***** This file should be named 61474-h.htm or 61474-h.zip *****

This and all associated files of various formats will be found in:

http://www.gutenberg.org/6/1/4/7/61474/

Produced by Greg Weeks, Mary Meehan and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

Updated editions will replace the previous one--the old editions will

be renamed.

Creating the works from print editions not protected by U.S. copyright

law means that no one owns a United States copyright in these works,

so the Foundation (and you!) can copy and distribute it in the United

States without permission and without paying copyright

royalties. Special rules, set forth in the General Terms of Use part

of this license, apply to copying and distributing Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works to protect the PROJECT GUTENBERG-tm

concept and trademark. Project Gutenberg is a registered trademark,

and may not be used if you charge for the eBooks, unless you receive

specific permission. If you do not charge anything for copies of this

eBook, complying with the rules is very easy. You may use this eBook

for nearly any purpose such as creation of derivative works, reports,

performances and research. They may be modified and printed and given

away--you may do practically ANYTHING in the United States with eBooks

not protected by U.S. copyright law. Redistribution is subject to the

trademark license, especially commercial redistribution.

START: FULL LICENSE

THE FULL PROJECT GUTENBERG LICENSE

PLEASE READ THIS BEFORE YOU DISTRIBUTE OR USE THIS WORK

To protect the Project Gutenberg-tm mission of promoting the free

distribution of electronic works, by using or distributing this work

(or any other work associated in any way with the phrase "Project

Gutenberg"), you agree to comply with all the terms of the Full

Project Gutenberg-tm License available with this file or online at

www.gutenberg.org/license.

Section 1. General Terms of Use and Redistributing Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works

1.A. By reading or using any part of this Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic work, you indicate that you have read, understand, agree to

and accept all the terms of this license and intellectual property

(trademark/copyright) agreement. If you do not agree to abide by all

the terms of this agreement, you must cease using and return or

destroy all copies of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works in your

possession. If you paid a fee for obtaining a copy of or access to a

Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work and you do not agree to be bound

by the terms of this agreement, you may obtain a refund from the

person or entity to whom you paid the fee as set forth in paragraph

1.E.8.

1.B. "Project Gutenberg" is a registered trademark. It may only be

used on or associated in any way with an electronic work by people who

agree to be bound by the terms of this agreement. There are a few

things that you can do with most Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works

even without complying with the full terms of this agreement. See

paragraph 1.C below. There are a lot of things you can do with Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works if you follow the terms of this

agreement and help preserve free future access to Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic works. See paragraph 1.E below.

1.C. The Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation ("the

Foundation" or PGLAF), owns a compilation copyright in the collection

of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works. Nearly all the individual

works in the collection are in the public domain in the United

States. If an individual work is unprotected by copyright law in the

United States and you are located in the United States, we do not

claim a right to prevent you from copying, distributing, performing,

displaying or creating derivative works based on the work as long as

all references to Project Gutenberg are removed. Of course, we hope

that you will support the Project Gutenberg-tm mission of promoting

free access to electronic works by freely sharing Project Gutenberg-tm

works in compliance with the terms of this agreement for keeping the

Project Gutenberg-tm name associated with the work. You can easily

comply with the terms of this agreement by keeping this work in the

same format with its attached full Project Gutenberg-tm License when

you share it without charge with others.

1.D. The copyright laws of the place where you are located also govern

what you can do with this work. Copyright laws in most countries are

in a constant state of change. If you are outside the United States,

check the laws of your country in addition to the terms of this

agreement before downloading, copying, displaying, performing,

distributing or creating derivative works based on this work or any

other Project Gutenberg-tm work. The Foundation makes no

representations concerning the copyright status of any work in any

country outside the United States.

1.E. Unless you have removed all references to Project Gutenberg:

1.E.1. The following sentence, with active links to, or other

immediate access to, the full Project Gutenberg-tm License must appear

prominently whenever any copy of a Project Gutenberg-tm work (any work

on which the phrase "Project Gutenberg" appears, or with which the

phrase "Project Gutenberg" is associated) is accessed, displayed,

performed, viewed, copied or distributed:

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and

most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no

restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it

under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this

eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the

United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you

are located before using this ebook.

1.E.2. If an individual Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work is

derived from texts not protected by U.S. copyright law (does not

contain a notice indicating that it is posted with permission of the

copyright holder), the work can be copied and distributed to anyone in

the United States without paying any fees or charges. If you are

redistributing or providing access to a work with the phrase "Project

Gutenberg" associated with or appearing on the work, you must comply

either with the requirements of paragraphs 1.E.1 through 1.E.7 or

obtain permission for the use of the work and the Project Gutenberg-tm

trademark as set forth in paragraphs 1.E.8 or 1.E.9.

1.E.3. If an individual Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work is posted

with the permission of the copyright holder, your use and distribution

must comply with both paragraphs 1.E.1 through 1.E.7 and any

additional terms imposed by the copyright holder. Additional terms

will be linked to the Project Gutenberg-tm License for all works

posted with the permission of the copyright holder found at the

beginning of this work.

1.E.4. Do not unlink or detach or remove the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License terms from this work, or any files containing a part of this

work or any other work associated with Project Gutenberg-tm.

1.E.5. Do not copy, display, perform, distribute or redistribute this

electronic work, or any part of this electronic work, without

prominently displaying the sentence set forth in paragraph 1.E.1 with

active links or immediate access to the full terms of the Project

Gutenberg-tm License.

1.E.6. You may convert to and distribute this work in any binary,

compressed, marked up, nonproprietary or proprietary form, including

any word processing or hypertext form. However, if you provide access

to or distribute copies of a Project Gutenberg-tm work in a format

other than "Plain Vanilla ASCII" or other format used in the official

version posted on the official Project Gutenberg-tm web site

(www.gutenberg.org), you must, at no additional cost, fee or expense

to the user, provide a copy, a means of exporting a copy, or a means

of obtaining a copy upon request, of the work in its original "Plain

Vanilla ASCII" or other form. Any alternate format must include the

full Project Gutenberg-tm License as specified in paragraph 1.E.1.

1.E.7. Do not charge a fee for access to, viewing, displaying,

performing, copying or distributing any Project Gutenberg-tm works

unless you comply with paragraph 1.E.8 or 1.E.9.

1.E.8. You may charge a reasonable fee for copies of or providing

access to or distributing Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works

provided that

* You pay a royalty fee of 20% of the gross profits you derive from

the use of Project Gutenberg-tm works calculated using the method

you already use to calculate your applicable taxes. The fee is owed

to the owner of the Project Gutenberg-tm trademark, but he has

agreed to donate royalties under this paragraph to the Project

Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation. Royalty payments must be paid

within 60 days following each date on which you prepare (or are

legally required to prepare) your periodic tax returns. Royalty

payments should be clearly marked as such and sent to the Project

Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation at the address specified in

Section 4, "Information about donations to the Project Gutenberg

Literary Archive Foundation."

* You provide a full refund of any money paid by a user who notifies

you in writing (or by e-mail) within 30 days of receipt that s/he

does not agree to the terms of the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License. You must require such a user to return or destroy all

copies of the works possessed in a physical medium and discontinue

all use of and all access to other copies of Project Gutenberg-tm

works.

* You provide, in accordance with paragraph 1.F.3, a full refund of

any money paid for a work or a replacement copy, if a defect in the

electronic work is discovered and reported to you within 90 days of

receipt of the work.

* You comply with all other terms of this agreement for free

distribution of Project Gutenberg-tm works.

1.E.9. If you wish to charge a fee or distribute a Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic work or group of works on different terms than

are set forth in this agreement, you must obtain permission in writing

from both the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation and The

Project Gutenberg Trademark LLC, the owner of the Project Gutenberg-tm

trademark. Contact the Foundation as set forth in Section 3 below.

1.F.

1.F.1. Project Gutenberg volunteers and employees expend considerable

effort to identify, do copyright research on, transcribe and proofread

works not protected by U.S. copyright law in creating the Project

Gutenberg-tm collection. Despite these efforts, Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic works, and the medium on which they may be stored, may

contain "Defects," such as, but not limited to, incomplete, inaccurate

or corrupt data, transcription errors, a copyright or other

intellectual property infringement, a defective or damaged disk or

other medium, a computer virus, or computer codes that damage or

cannot be read by your equipment.

1.F.2. LIMITED WARRANTY, DISCLAIMER OF DAMAGES - Except for the "Right

of Replacement or Refund" described in paragraph 1.F.3, the Project

Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation, the owner of the Project

Gutenberg-tm trademark, and any other party distributing a Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic work under this agreement, disclaim all

liability to you for damages, costs and expenses, including legal

fees. YOU AGREE THAT YOU HAVE NO REMEDIES FOR NEGLIGENCE, STRICT

LIABILITY, BREACH OF WARRANTY OR BREACH OF CONTRACT EXCEPT THOSE

PROVIDED IN PARAGRAPH 1.F.3. YOU AGREE THAT THE FOUNDATION, THE

TRADEMARK OWNER, AND ANY DISTRIBUTOR UNDER THIS AGREEMENT WILL NOT BE

LIABLE TO YOU FOR ACTUAL, DIRECT, INDIRECT, CONSEQUENTIAL, PUNITIVE OR

INCIDENTAL DAMAGES EVEN IF YOU GIVE NOTICE OF THE POSSIBILITY OF SUCH

DAMAGE.

1.F.3. LIMITED RIGHT OF REPLACEMENT OR REFUND - If you discover a

defect in this electronic work within 90 days of receiving it, you can

receive a refund of the money (if any) you paid for it by sending a

written explanation to the person you received the work from. If you

received the work on a physical medium, you must return the medium

with your written explanation. The person or entity that provided you

with the defective work may elect to provide a replacement copy in

lieu of a refund. If you received the work electronically, the person

or entity providing it to you may choose to give you a second

opportunity to receive the work electronically in lieu of a refund. If

the second copy is also defective, you may demand a refund in writing

without further opportunities to fix the problem.

1.F.4. Except for the limited right of replacement or refund set forth

in paragraph 1.F.3, this work is provided to you 'AS-IS', WITH NO

OTHER WARRANTIES OF ANY KIND, EXPRESS OR IMPLIED, INCLUDING BUT NOT

LIMITED TO WARRANTIES OF MERCHANTABILITY OR FITNESS FOR ANY PURPOSE.

1.F.5. Some states do not allow disclaimers of certain implied

warranties or the exclusion or limitation of certain types of

damages. If any disclaimer or limitation set forth in this agreement

violates the law of the state applicable to this agreement, the

agreement shall be interpreted to make the maximum disclaimer or

limitation permitted by the applicable state law. The invalidity or

unenforceability of any provision of this agreement shall not void the

remaining provisions.

1.F.6. INDEMNITY - You agree to indemnify and hold the Foundation, the

trademark owner, any agent or employee of the Foundation, anyone

providing copies of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works in

accordance with this agreement, and any volunteers associated with the

production, promotion and distribution of Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic works, harmless from all liability, costs and expenses,

including legal fees, that arise directly or indirectly from any of

the following which you do or cause to occur: (a) distribution of this

or any Project Gutenberg-tm work, (b) alteration, modification, or

additions or deletions to any Project Gutenberg-tm work, and (c) any

Defect you cause.

Section 2. Information about the Mission of Project Gutenberg-tm

Project Gutenberg-tm is synonymous with the free distribution of

electronic works in formats readable by the widest variety of

computers including obsolete, old, middle-aged and new computers. It

exists because of the efforts of hundreds of volunteers and donations

from people in all walks of life.

Volunteers and financial support to provide volunteers with the

assistance they need are critical to reaching Project Gutenberg-tm's

goals and ensuring that the Project Gutenberg-tm collection will

remain freely available for generations to come. In 2001, the Project

Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation was created to provide a secure

and permanent future for Project Gutenberg-tm and future

generations. To learn more about the Project Gutenberg Literary

Archive Foundation and how your efforts and donations can help, see

Sections 3 and 4 and the Foundation information page at

www.gutenberg.org

Section 3. Information about the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation

The Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation is a non profit

501(c)(3) educational corporation organized under the laws of the

state of Mississippi and granted tax exempt status by the Internal

Revenue Service. The Foundation's EIN or federal tax identification

number is 64-6221541. Contributions to the Project Gutenberg Literary

Archive Foundation are tax deductible to the full extent permitted by

U.S. federal laws and your state's laws.

The Foundation's principal office is in Fairbanks, Alaska, with the

mailing address: PO Box 750175, Fairbanks, AK 99775, but its

volunteers and employees are scattered throughout numerous

locations. Its business office is located at 809 North 1500 West, Salt

Lake City, UT 84116, (801) 596-1887. Email contact links and up to

date contact information can be found at the Foundation's web site and

official page at www.gutenberg.org/contact

For additional contact information:

Dr. Gregory B. Newby

Chief Executive and Director

gbnewby@pglaf.org

Section 4. Information about Donations to the Project Gutenberg

Literary Archive Foundation

Project Gutenberg-tm depends upon and cannot survive without wide

spread public support and donations to carry out its mission of

increasing the number of public domain and licensed works that can be

freely distributed in machine readable form accessible by the widest

array of equipment including outdated equipment. Many small donations

($1 to $5,000) are particularly important to maintaining tax exempt

status with the IRS.

The Foundation is committed to complying with the laws regulating

charities and charitable donations in all 50 states of the United

States. Compliance requirements are not uniform and it takes a

considerable effort, much paperwork and many fees to meet and keep up

with these requirements. We do not solicit donations in locations

where we have not received written confirmation of compliance. To SEND

DONATIONS or determine the status of compliance for any particular

state visit www.gutenberg.org/donate

While we cannot and do not solicit contributions from states where we

have not met the solicitation requirements, we know of no prohibition

against accepting unsolicited donations from donors in such states who

approach us with offers to donate.

International donations are gratefully accepted, but we cannot make

any statements concerning tax treatment of donations received from

outside the United States. U.S. laws alone swamp our small staff.

Please check the Project Gutenberg Web pages for current donation

methods and addresses. Donations are accepted in a number of other

ways including checks, online payments and credit card donations. To

donate, please visit: www.gutenberg.org/donate

Section 5. General Information About Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works.

Professor Michael S. Hart was the originator of the Project

Gutenberg-tm concept of a library of electronic works that could be

freely shared with anyone. For forty years, he produced and

distributed Project Gutenberg-tm eBooks with only a loose network of

volunteer support.

Project Gutenberg-tm eBooks are often created from several printed

editions, all of which are confirmed as not protected by copyright in

the U.S. unless a copyright notice is included. Thus, we do not

necessarily keep eBooks in compliance with any particular paper

edition.

Most people start at our Web site which has the main PG search

facility: www.gutenberg.org

This Web site includes information about Project Gutenberg-tm,

including how to make donations to the Project Gutenberg Literary

Archive Foundation, how to help produce our new eBooks, and how to

subscribe to our email newsletter to hear about new eBooks.