Raklang pass — Uses of nettles — Edible plants — Lepcha war — Do- mani stone — Neongong — Teesta valley — Pony, saddle, etc. — Meet Campbell — Vegetation and scenery — Presents — Visit of Dewan — Characters of Rajah and Dewan — Accounts of Tibet — Lhassa — Siling — Tricks of Dewan — Walk up Teesta — Audience of Rajah — Lamas — Kajees — Tchebu Lama, his character and position — Effects of interview — Heir-apparent — Dewan’s house — Guitar — Weather — Fall of river — Tibet officers — Gigantic trees — Neongong lake — Mainom, ascent of — Vegetation — Camp on snow — Silver fire — View from top — Kinchin, etc. — Geology — Vapours — Sunset effect — Elevation — Temperature, etc. — Lamas of Neongong — Temples — Religious festival — Bamboo, flowering — Recross pass of Raklang — Numerous temples, villages, etc. — Domestic animals — Descent to Great Rungeet.

On the following morning, after receiving the usual presents from the Lamas of Dholing, and from a large posse of women belonging to the village of Barphiung, close by, we ascended the Raklang pass, which crosses the range dividing the waters of the Teesta from those of the Great Rungeet. The Kajee still kept beside me, and proved a lively companion: seeing me continually plucking and noting plants, he gave me much local information about them. He told me the uses made of the fibres of the various nettles; some being twisted for bowstrings, others as a thread for sewing and weaving; while many are eaten raw and in soups, especially the numerous little succulent species. The great yellow-flowered Begonia was abundant, and he cut its juicy stalks to make sauce (as we do apple-sauce) for some pork which he expected to get at Bhomsong; the taste

is acid and very pleasant. The large succulent fern, called Botrychium,* grew here plentifully; it is boiled and eaten, both here and in New Zealand. Ferns are more commonly used for food than is supposed. In Calcutta the Hindoos boil young tops of a Polypodium with their shrimp curries; and both in Sikkim and Nepal the watery tubers of an Aspidium are abundantly eaten. So also the pulp of one tree-fern affords food, but only in times of scarcity, as does that of another species in New Zealand (Cyathea medullaris): the pith of all is composed of a coarse sago, that is to say, of cellular tissue with starch granules.

A thick forest of Dorjiling vegetation covers the summit, which is only 6,800 feet above the sea: it is a saddle, connecting the lofty mountain of Mainom (alt. 11,000 feet) to the north, with Tendong (alt. 8,663 feet) to the south. Both these mountains are on a range which is continuous with Kinchinjunga, projecting from it down into the very heart of Sikkim. A considerable stand was made here by the Lepchas during the Nepal war in 1787; they defended the pass with their arrows for some hours, and then retired towards the Teesta, making a second stand lower down, at a place pointed out to me, where rocks on either side gave them the same advantages. The Nepalese, however, advanced to the Teesta, and then retired with little loss.

Unfortunately a thick mist and heavy rain cut off all view of the Teesta valley, and the mountains of Chola to the eastward; which I much regretted.

Descending by a very steep, slippery path, we came to a

* Botrychium Virginicum, Linn. This fern is eaten abundantly by the New Zealanders: its distribution is most remarkable, being found very rarely indeed in Europe, and in Norway only. It abounds in many parts of the Southern United States, the Andes of Mexico, etc., in the Himalaya mountains, Australia, and New Zealand.

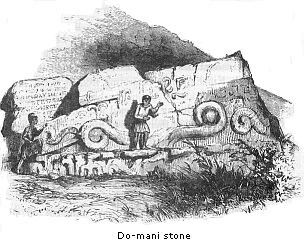

fine mass of slaty gneiss, thirty feet long and thirteen feet high; not in situ, but lying on the mountain side: on its sloping face was carved in enormous characters, “Om Mani Padmi om”; of which letters the top-strokes afford an uncertain footing to the enthusiast who is willing to purchase a good metempsychosis by walking along the slope, with his heels or toes in their cavities. A small inscription in one corner is said to imply that this was the work of a pious monk of Raklang; and the stone is called “Do-mani,” literally, “stone of prayer.”

The rocks and peaks of Mainom are said to overhang the descent here with grandeur; but the continued rain hid everything but a curious shivered peak, apparently of chlorite schist, which was close by, and reflected a green colour it is of course reported to be of turquoise, and inaccessible.

Descending, the rocks became more micaceous, with broad seams of pipe-clay, originating in decomposed beds of felspathic gneiss: the natives used this to whitewash and mortar their temples.

I passed the monastery of Neongong, the monks of which were building a new temple; and came to bring me a large present. Below it is a pretty little lake, about 100 yards across, fringed with brushwood. We camped at the village of Nampok, 4,370 feet above the sea; all thoroughly sodden with rain.

During the night much snow had fallen at and above 9000 feet, but the weather cleared on the following morning, and disclosed the top of Mainom, rising close above my camp, in a series of rugged shivered peaks, crested with pines, which looked like statues of snow: to all other quarters this mountain presents a very gently sloping outline. Up the Teesta valley there was a pretty peep of snowy mountains, bearing north 35° east, of no great height.

I was met by a messenger from Dr. Campbell who told me he was waiting breakfast; so I left my party, and, accompanied by the Kajee and Meepo, hurried down to the valley of the Rungoon (which flows east to the Teesta), through a fine forest of tropical trees; passing the villages of Broom* and Lingo, to the spur of that name; where I was met by a servant of the Sikkim Dewan’s, with a pony for my use. I stared at the animal, and felt inclined to ask what he had to do here, where it was difficult enough

* On the top of the ridge above Broom, a tall stone is erected by the side of the path, covered with private marks, indicating the height of various individuals who are accustomed to measure themselves thus; there was but one mark above 5 feet 7 inches, and that was 6 inches higher. It turned out to be Campbell’s, who had passed a few days before, and was thus proved to top the natives of Sikkim by a long way.

to walk up and down slippery slopes, amongst boulders of rock, heavy forest, and foaming torrents; but I was little aware of what these beasts could accomplish. The Tartar saddle was imported from Tibet, and certainly a curiosity; once—but a long time ago—it must have been very handsome; it was high-peaked, covered with shagreen and silvered ornaments, wretchedly girthed, and with great stirrups attached to short leathers. The bridle and head-gear were much too complicated for description; there were good leather, raw hide, hair-rope, and scarlet worsted all brought into use; the bit was the ordinary Asiatic one, jointed, and with two rings. I mounted on one side, and at once rolled over, saddle and all, to the other; the pony standing quite still. I preferred walking; but Dr. Campbell had begged of me to use the pony, as the Dewan had procured and sent it at great trouble: I, however, had it led till I was close to Bhomsong, when I was hoisted into the saddle and balanced on it, with my toes in the stirrups and my knees up to my breast; twice, on the steep descent to the river, my saddle and I were thrown on the pony’s neck; in these awkward emergencies I was assisted by a man on each side, who supported my weight on my elbows: they seemed well accustomed to easing mounted ponies down hill without giving the rider the trouble of dismounting. Thus I entered Dr. Campbell’s camp at Bhomsong, to the pride and delight of my attendants; and received a hearty welcome from my old friend, who covered me with congratulations on the successful issue of a journey which, at this season, and under such difficulties and discouragements, he had hardly thought feasible.

Dr. Campbell’s tent was pitched in an orange-grove, occupying a flat on the west bank of the Teesta, close to a small enclosure of pine-apples, with a pomegranate tree in

the middle. The valley is very narrow, and the vegetation wholly tropical, consisting of two species of oak, several palms, rattan-cane (screw-pine), Pandanus, tall grasses, and all the natives of dense hot jungles. The river is a grand feature, broad, rocky, deep, swift, and broken by enormous boulders of rock; its waters were of a pale opal green, probably from the materials of the soft micaceous rocks through which it flows.

A cane bridge crosses it,* but had been cut away (in feigned distrust of us), and the long canes were streaming from their attachments on either shore down the stream, and a triangular raft of bamboo was plying instead, drawn to and fro by means of a strong cane.

Soon after arriving I received a present from the Rajah, consisting of a brick of Tibet tea, eighty pounds of rancid yak butter, in large squares, done up in yak-hair cloth, three loads of rice, and one of Murwa for beer; rolls of bread,† fowls, eggs, dried plums, apricots, jujubes, currants, and Sultana raisins, the latter fruits purchased at Lhassa, but imported thither from western Tibet; also some trays of coarse milk-white crystallised salt, as dug in Tibet.

In the evening we were visited by the Dewan, the head and front of all our Sikkim difficulties, whose influence was paramount with the Rajah, owing to the age and infirmities of the latter, and his devotion to religion, which absorbed all his time and thoughts. The Dewan was a good-looking Tibetan, very robust, fair, muscular and well fleshed; he had a very broad Tartar face, quite free of hair; a small and beautifully formed mouth and chin, very broad cheekbones,

* Whence the name of Bhomsong Samdong, the latter

word meaning bridge.

† These rolls, or rather, sticks of bread, are made in

Tibet, of fine wheaten flour, and keep for a long time: they are

sweet and good, but very dirtily prepared.

and a low, contracted forehead: his manners were courteous and polite, but evidently affected, in assumption of better breeding than he could in reality lay claim to. The Rajah himself was a Tibetan of just respectable extraction, a native of the Sokpo province, north of Lhassa: his Dewan was related to one of his wives, and I believe a Lhassan by birth as well as extraction, having probably also Kashmir blood in him.* Though minister, he was neither financier nor politician, but a mere plunderer of Sikkim, introducing his relations, and those whom he calls so, into the best estates in the country, and trading in great and small wares, from a Tibet pony to a tobacco pipe, wholesale and retail. Neither he nor the Rajah are considered worthy of notice by the best Tibet families or priests, or by the Chinese commissioners settled in Lhassa and Jigatzi. The latter regard Sikkim as virtually English, and are contented with knowing that its ruler has no army, and with believing that its protectors, the English, could not march an army across the Himalaya if they would.

The Dewan, trading in wares which we could supply better and cheaper, naturally regarded us with repugnance, and did everything in his power to thwart Dr. Campbell’s attempts to open a friendly communication between the Sikkim and English governments. The Rajah owed everything to us, and was, I believe, really grateful; but he was a mere cipher in the hands of his minister. The priests again, while rejoicing in our proximity, were apathetic, and dreaded the more active Dewan; and the people had long given evidence of their confidence in the English. Under these circumstances it was in the hope of gaining the Rajah’s own ear, and representing to him the advantages

* The Tibetans court promiscuous intercourse between their families and the Kashmir merchants who traverse their country.

of promoting an intercourse with us, and the danger of continuing to violate the terms of our treaty, that Dr. Campbell had been authorised by government to seek an interview with His Highness. At present our relations were singularly infelicitous. There was no agent on the Sikkim Rajah’s part to conduct business at Dorjiling, and the Dewan insisted on sending a creature of his own, who had before been dismissed for insolence. Malefactors who escaped into Sikkim were protected, and our police interrupted in the discharge of their duties; slavery was practised; and government communications were detained for weeks and months under false pretences.

In his interviews with us the Dewan appeared to advantage: he was fond of horses and shooting, and prided himself on his hospitality. We gained much information from many conversations with him, during which politics were never touched upon. Our queries naturally referred to Tibet and its geography, especially its great feature the Yarou Tsampoo river; this he assured us was the Burrampooter of Assam, and that no one doubted it in that country. Lhassa he described as a city in the bottom of a flat-floored valley, surrounded by lofty snowy mountains: neither grapes, tea, silk, or cotton are produced near it, but in the Tartchi province of Tibet, one month’s journey east of Lhassa, rice, and a coarse kind of tea are both grown. Two months’ journey north-east of Lhassa is Siling, the well-known great commercial entrepôt* in west China; and there coarse silk is produced. All Tibet he described as mountainous, and an inconceivably poor country: there are no plains, save flats in the bottoms of the valleys, and the paths lead over lofty mountains. Sometimes, when the inhabitants are obliged from famine to change their habitations in winter, the old

* The entrepôt is now removed to Tang-Keou-Eul.—See Huc and Gabet.

and feeble are frozen to death, standing and resting their chins on their staves; remaining as pillars of ice, to fall only when the thaw of the ensuing spring commences.

We remained several days at Bhomsong, awaiting an interview with the Rajah, whose movements the Dewan kept shrouded in mystery. On Dr. Campbell’s arrival at this river a week before, he found messengers waiting to inform him that the Rajah would meet him here; this being half way between Dorjiling and Tumloong. Thenceforward every subterfuge was resorted to by the Dewan to frustrate the meeting; and even after the arrival of the Rajah on the east bank, the Dewan communicated with Dr. Campbell by shooting across the river arrows to which were attached letters, containing every possible argument to induce him to return to Dorjiling; such as that the Rajah was sick at Tumloong, that he was gone to Tibet, that he had a religious fast and rites to perform, etc. etc.

One day we walked up the Teesta to the Rumphiup river, a torrent from Mainom mountain to the west; the path led amongst thick jungle of Wallichia palm, prickly rattan canes, and the Pandanus, or screw-pine, called “Borr,” which has a straight, often forked, palm-like trunk, and an immense crown of grassy saw-edged leaves four feet long: it bears clusters of uneatable fruit as large as a man’s fist, and their similarity to the pine-apple has suggested the name of “Borr” for the latter fruit also, which has for many years been cultivated in Sikkim, and yields indifferent produce. Beautiful pink balsams covered the ground, but at this season few other showy plants were in flower: the rocks were chlorite, very soft and silvery, and so curiously crumpled and contorted as to appear as though formed of scaled of mica crushed together,

and confusedly arranged in layers: the strike was north-west, and dip north-east from 60° to 70°.

Messengers from the Dewan overtook us at the river to announce that the Rajah was prepared and waiting to give us a reception; so we returned, and I borrowed a coat from Dr. Campbell instead of my tattered shooting-jacket; and we crossed the river on the bamboo-raft. As it is the custom on these occasions to exchange presents, I was officially supplied with some red cloth and beads: these, as well as Dr. Campbell’s present, should only have been delivered during or after the audience; but our wily friend the Dewan here played us a very shabby trick; for he managed that our presents should be stealthily brought in before our appearance, thus giving to the by-standers the impression of our being tributaries to his Highness!

The audience chamber was a mere roofed shed of neat bamboo wattle, about twenty feet long: two Bhoteeas in scarlet jackets, and with bows in their hands, stood on each side of the door, and our own chairs were carried before us for our accommodation. Within was a square wicker throne, six feet high, covered with purple silk, brocaded with dragons in white and gold, and overhung by a canopy of tattered blue silk, with which material part of the walls also was covered. An oblong box (containing papers) with gilded dragons on it, was placed on the stage or throne, and behind it was perched cross-legged, an odd, black, insignificant looking old man, with twinkling upturned eyes: he was swathed in yellow silk, and wore on his head a pink silk hat with a flat broad crown, from all sides of which hung floss silk. This was the Rajah, a genuine Tibetan, about seventy years old. On some steps close by, and ranged down the apartment, were his relations, all in brocaded silk robes reaching from the throat to the ground,

and girded about the waist; and wearing caps similar to that of the Rajah. Kajees, counsellors, and shaven mitred Lamas were there, to the number of twenty, all planted with their backs to the wall, mute and motionless as statues. A few spectators were huddled together at the lower end of the room, and a monk waved about an incense pot containing burning juniper and other odoriferous plants. Altogether the scene was solemn and impressive: as Campbell well expressed it, the genius of Lamaism reigned supreme.

We saluted, but received no complimentary return; our chairs were then placed, and we seated ourselves, when the Dewan came in, clad in a superb purple silk robe, worked with circular gold figures, and formally presented us. The Dewan then stood; and as the Rajah did not understand Hindoostanee, our conversation was carried on through the medium of a little bare-headed rosy-cheeked Lama, named “Tchebu,” clad in a scarlet gown, who acted as interpreter. The conversation was short and constrained: Tchebu was known as a devoted servant of the Rajah and of the heir apparent; and in common with all the Lamas he hates the Dewan, and desires a friendly intercourse between Sikkim and Dorjiling. He is, further, the only servant of the Rajah capable of conversing both in Hindoo and Tibetan, and the uneasy distrustful look of the Dewan, who understands the latter language only, was very evident. He was as anxious to hurry over the interview, as Dr. Campbell and Tchebu were to protract it; it was clear, therefore, that nothing satisfactory could be done under such auspices.

As a signal for departure white silk scarfs were thrown over our shoulders, according to the established custom in Tibet, Sikkim, and Bhotan; and presents were made to us of China silks, bricks of tea, woollen cloths,

yaks, ponies, and salt, with worked silk purses and fans for Mrs. Campbell; after which we left. The whole scene was novel and very curious. We had had no previous idea of the extreme poverty of the Rajah, of his utter ignorance of the usages of Oriental life, and of his not having anyone near to instruct him. The neglect of our salutation, and the conversion of our presents into tribute, did not arise from any ill-will: it was owing to the craft of the Dewan in taking advantage of the Rajah’s ignorance of his own position and of good manners. Miserably poor, without any retinue, taking no interest in what passes in his own kingdom, subsisting on the plainest and coarsest food, passing his time in effectually abstracting his mind from the consideration of earthly things, and wrapt in contemplation, the Sikkim Rajah has arrived at great sanctity, and is all but prepared for that absorption into the essence of Boodh, which is the end and aim of all good Boodhists. The mute conduct of his Court, who looked like attendants at an inquisition, and the profound veneration expressed in every word and gesture of those who did move and speak, recalled a Pekin reception. His attendants treated him as a being of a very different nature from themselves; and well might they do so, since they believe that he will never die, but retire from the world only to re-appear under some equally sainted form.

Though productive of no immediate good, our interview had a very favourable effect on the Lamas and people, who had long wished it; and the congratulations we received thereon during the remainder of our stay in Sikkim were many and sincere. The Lamas we found universally in high spirits; they having just effected the marriage of the heir apparent, himself a Lama, said to possess much ability and prudence, and hence being very obnoxious to the

Dewan, who vehemently opposed the marriage. As, however, the minister had established his influence over the youngest, and estranged the Rajah from his eldest son, and was moreover in a fair way for ruling Sikkim himself, the Church rose in a body, procured a dispensation from Lhassa for the marriage of a priest, and thus hoped to undermine the influence of the violent and greedy stranger.

In the evening, we paid a farewell visit to the Dewan, whom we found in a bamboo wicker-work hut, neatly hung with bows, arrows, and round Lepcha shields of cane, each with a scarlet tuft of yak-hair in the middle; there were also muskets, Tibetan arms, and much horse gear; and at one end was a little altar, with cups, bells, pastiles, and images. He was robed in a fawn-coloured silk gown, lined with the softest of wool, that taken from unborn lambs: like most Tibetans, he extracts all his beard with tweezers; an operation he civilly recommended to me, accompanying the advice with the present of a neat pair of steel forceps. He aspires to be considered a man of taste, and plays the Tibetan guitar, on which he performed some airs for our amusement: the instrument is round-bodied and long-armed, with six strings placed in pairs, and probably comes from Kashmir: the Tibetan airs were simple and quite pretty, with the time well marked.

During our stay at Bhomsong, the weather was cool, considering the low elevation (1,500 feet), and very steady; the mean temperature was 52·25°, the maximum 71·25°, the minimum 42·75°. The sun set behind the lofty mountains at 3 p.m., and in the morning a thick, wet, white, dripping fog settled in the bottom of the valley, and extended to 800 or 1000 feet above the river-bed; this was probably caused by the descent of cold currents into the humid gorge: it was dissipated soon after sunrise, but formed

again at sunset for a few minutes, giving place to clear starlight nights.

A thermometer sunk two feet seven inches, stood at 64°. The temperature of the water was pretty constant at 51°: from here to the plains of India the river has a nearly uniform fall of 1000 feet in sixty-nine miles, or sixteen feet to a mile: were its course straight for the same distance, the fall would be 1000 feet in forty miles, or twenty-five feet to a mile.

Dr. Campbell’s object being accomplished, he was anxious to make the best use of the few days that remained before his return to Dorjiling, and we therefore arranged to ascend Mainom, and visit the principal convents in Sikkim together, after which he was to return south, whilst I should proceed north to explore the south flank of Kinchinjunga. For the first day our route was that by which I had arrived. We left on Christmas-day, accompanied by two of the Rajah’s, or rather Dewan’s officers, of the ranks of Dingpun and Soupun, answering to those of captain and lieutenant; the titles were, however, nominal, the Rajah having no soldiers, and these men being profoundly ignorant of the mysteries of war or drill. They were splendid specimens of Sikkim Bhoteeas (i.e. Tibetans, born in Sikkim, sometimes called Arrhats), tall, powerful, and well built, but insolent and bullying: the Dingpun wore the Lepcha knife, ornamented with turquoises, together with Chinese chopsticks. Near Bhomsong, Campbell pointed out a hot bath to me, which he had seen employed: it consisted of a hollowed prostrate tree trunk, the water in which was heated by throwing in hot stones with bamboo tongs. The temperature is thus raised to 114°, to which the patient submits at repeated intervals for several days, never leaving till wholly exhausted.

These baths are called “Sa-choo,” literally “hot-water,” in Tibetan.

We stopped to measure some splendid trees in the valley, and found the trunk of one to be forty-five feet round the buttresses, and thirty feet above them, a large size for the Himalaya: they were a species of Terminalia (Pentaptera), and called by the Lepchas “Sillok-Kun,” “Kun” meaning tree.

We slept at Nampok, and the following morning commenced the ascent. On the way we passed the temple and lake of Neongong; the latter is about 400 yards round, and has no outlet. It contained two English plants, the common duckweed (Lemna minor), and Potamogeton natans: some coots were swimming in it, and having flushed a woodcock, I sent for my gun, but the Lamas implored us not to shoot, it being contrary to their creed to take life wantonly.

We left a great part of our baggage at Neongong, as we intended to return there; and took up with us bedding, food, etc., for two days. A path hence up the mountain is frequented once a year by the Lamas, who make a pilgrimage to the top for worship. The ascent was very gradual for 4000 feet. We met with snow at the level of Dorjiling (7000 feet), indicating a colder climate than at that station, where none had fallen; the vegetation was, however, similar, but not so rich, and at 8000 feet trees common also to the top of Sinchul appeared, with R. Hodgsoni, and the beautiful little winter-flowering primrose, P. petiolaris, whose stemless flowers spread like broad purple stars on the deep green foliage. Above, the path runs along the ridge of the precipices facing the south-east, and here we caught a glimpse of the great valley of the Ryott, beyond the Teesta, with Tumloong, the Rajah’s residence,

on its north flank, and the superb snowy peak of Chola at its head.

One of our coolies, loaded with crockery and various indispensables, had here a severe fall, and was much bruised; he however recovered himself, but not our goods.

The rocks were all of chlorite slate, which is not usual at this elevation; the strike was north-west, and dip north-east. At 9000 feet various shrubby rhododendrons prevailed, with mountain-ash, birch, and dwarf-bamboo; also R. Falconeri, which grew from forty to fifty feet high. The snow was deep and troublesome, so we encamped at 9,800 feet, or 800 feet below the top, in a wood of Pyrus, Magnolia, Rhododendron, and bamboo. As the ground was deeply covered with snow, we laid our beds on a thick layer of rhododendron twigs, bamboo, and masses of a pendent moss.

We passed a very cold night, chiefly owing to damp, the temperature falling to 24°. On the following morning we scrambled through the snow, reaching the summit after an hour’s very laborious ascent, and took up our quarters in a large wooden barn-like temple (goompa), built on a stone platform. The summit was very broad, but the depth of the snow prevented our exploring much, and the silver firs (Abies Webbiana) were so tall, that no view could be obtained, except from the temple. The great peak of Kinchinjunga is in part hidden by those of Pundim and Nursing, but the panorama of snowy mountains is very grand indeed. The effect is quite deceptive; the mountains assuming the appearance of a continued chain, the distant snowy peaks being seemingly at little further distance than the nearer ones. The whole range (about twenty-two miles nearer than at Dorjiling) appeared to rise uniformly and steeply out of black pine

forests, which were succeeded by the russet-brown of the rhododendron shrubs, and that again by tremendous precipices and gulleys, into which descended mighty glaciers and perpetual snows. This excessive steepness is however only apparent, being due to foreshortening.

The upper 10,000 feet of Kinchin, and the tops of Pundim, Kubra, and Junnoo, are evidently of granite, and are rounded in outline: the lower peaks again, as those of Nursing, etc., present rugged pinnacles of black and red stratified rocks, in many cases resting on white granite, to which they present a remarkable contrast. The general appearance was as if Kinchin and the whole mass of mountains clustered around it, had been up-heaved by white granite, which still forms the loftiest summits, and has raised the black stratified rocks in some places to 20,000 feet in numerous peaks and ridges. One range presented on every summit a cap of black stratified rocks of uniform inclination and dip, striking north-west, with precipitous faces to the south-west: this was clear to the naked eye, and more evident with the telescope, the range in question being only fifteen miles distant, running between Pundim and Nursing. The fact of the granite forming the greatest elevation must not be hastily attributed to that igneous rock having burst through the stratified, and been protruded beyond the latter: it is much more probable that the upheaval of the granite took place at a vast depth, and beneath an enormous pressure of stratified rocks and perhaps of the ocean; since which period the elevation of the whole mountain chain, and the denudation of the stratified rocks, has been slowly proceeding.

To what extent denudation has thus lowered the peaks we dare scarcely form a conjecture; but considering the number and variety of the beds which in some places

overlie the gneiss and granite, we may reasonably conclude that many thousand feet have been removed.

It is further assumable that the stratified rocks originally took the forms of great domes, or arches. The prevailing north-west strike throughout the Himalaya vaguely indicates a general primary arrangement of the curves into waves, whose crests run north-west and south-cast; an arrangement which no minor or posterior forces have wholly disturbed, though they have produced endless dislocations, and especially a want of uniformity in the amount and direction of the dip. Whether the loftiest waves were the result of one great convulsion, or of a long-continued succession of small ones, the effect would be the same, namely, that the strata over those points at which the granite penetrated the highest, would be the most dislocated, and the most exposed to wear during denudation.

We enjoyed the view of this superb scenery till noon, when the clouds which had obscured Dorjiling since morning were borne towards us by the southerly wind, rapidly closing in the landscape on all sides. At sunset they again broke, retreating from the northward, and rising from Sinchul and Dorjiling last of all, whilst a line of vapour, thrown by perspective into one narrow band, seemed to belt the Singalelah range with a white girdle, darkened to black where it crossed the snowy mountains; and it was difficult to believe that this belt did not really hang upon the ranges from twenty to thirty miles off, against which it was projected; or that its true position was comparatively close to the mountain on which we were standing, and was due to condensation around its cool, broad, flat summit.

As usual from such elevations, sunset produced many beautiful effects. The zenith was a deep blue, darkening

opposite the setting sun, and paling over it into a peach colour, and that again near the horizon passing into a glowing orange-red, crossed by coppery streaks of cirrhus. Broad beams of pale light shot from the sun to the meridian, crossing the moon and the planet Venus. Far south, through gaps in the mountains, the position of the plains of India, 10,000 feet below us, was indicated by a deep leaden haze, fading upwards in gradually paler bands (of which I counted fifteen) to the clear yellow of the sunset sky. As darkness came on, the mists collected around the top of Mainom, accumulating on the windward side, and thrown off in ragged masses from the opposite.

The second night we passed here was fine, and not very cold (the mean temperature being 27° and we kept ourselves quite warm by pine-wood fires. On the following morning the sun tinged the sky of a lurid yellow-red: to the south-west, over the plains, the belts of leaden vapour were fewer (twelve being distinguishable) and much lower than on the previous evening, appearing as if depressed on the visible horizon. Heavy masses of clouds nestled into all the valleys, and filled up the larger ones, the mountain tops rising above them like islands.

The height of our position I calculated to be 10,613 feet. Colonel Waugh had determined that of the summit by trigonometry to be 10,702 feet, which probably includes the trees which cover it, or some rocky peaks on the broad and comparatively level surface.

The mean temperature of the twenty-four hours was 32·7° (max. 41·5°/min. 27·2°), mean dew-point 29·7, and saturation 0·82. The mercury suddenly fell below the freezing point at sunset; and from early morning the radiation was so powerful, that a thermometer exposed on snow sank to 21·2°, and stood at 25·5°, at 10 a.m. The black bulb

thermometer rose to 132°, at 9 a.m. on the 27th, or 94·2° above the temperature of the air in the shade. I did not then observe that of radiation from snow; but if, as we may assume, it was not less than on the following morning (21·2°), we shall have a difference of 148·6° Fahr., in contiguous spots; the one exposed to the full effects of the sun, the other to that of radiation through a rarefied medium to a cloudless sky. On the 28th the black bulb thermometer, freely suspended over the snow and exposed to the sun, rose to 108°, or 78° above that of the air in the shade (32°); the radiating surface of the same snow in the shade being 21·2°, or 86·8° colder.

Having taken a complete set of angles and panoramic sketches from the top of Mainom, with seventeen hourly observations, and collected much information from our guides, we returned on the 28th to our tents pitched by the temples at Neongong; descending 7000 feet, a very severe shake along Lepcha paths. In the evening the Lamas visited us, with presents of rice, fowls, eggs, etc., and begged subscriptions for their temple which was then building, reminding Dr. Campbell that he and the Governor-General had an ample share of their prayers, and benefited in proportion. As for me, they said, I was bound to give alms, as I surely needed praying for, seeing how I exposed myself; besides my having been the first Englishman who had visited the snows of Kinchinjunga, the holiest spot in Sikkim.

On the following morning we visited the unfinished temple. The outer walls were of slabs of stone neatly chiselled, but badly mortared with felspathic clay and pounded slate, instead of lime; the partition walls were of clay, shaped in moulds of wood; parallel planks, four feet asunder, being placed in the intended position of the

walls, and left open above, the composition was placed in these boxes, a little at a time, and rammed down by the feet of many men, who walked round and round the narrow enclosure, singing, and also using rammers of heavy wood. The outer work was of good hard timber, of Magnolia (“Pendre-kun” of the Lepchas) land oak (“Sokka”). The common “Ban,” or Lepcha knife, supplied the place of axe, saw, adze, and plane; and the graving work was executed with small tools, chiefly on Toon (Cedrela), a very soft wood (the “Simal-kun” of the Lepchas).

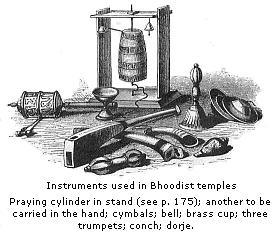

This being a festival day, when the natives were bringing offerings to the altar, we also visited the old temple, a small wooden building. Besides more substantial offerings, there were little cones of rice with a round wafer of butter at the top, ranged on the altar in order.* Six Lamas were at prayer, psalms, and contemplation, sitting cross-legged on two small benches that ran down the building: one was reading, with his hand and fore-finger elevated, whilst the others listened; anon they all sang hymns, repeated sacred or silly precepts to the bystanders, or joined in a chorus with boys, who struck brass cymbals, and blew straight copper trumpets six feet long, and conch-shells mounted with broad silver wings, elegantly carved with dragons. There were besides manis, or praying-cylinders, drums, gongs, books, and trumpets made of human thigh-bones, plain or mounted in silver.

* The worshippers, on entering, walk straight up to the altar, and before, or after, having deposited their gifts, they lift both hands to the forehead, fall on their knees, and touch the ground three times with both head and hands, raising the body a little between each prostration. They then advance to the head Lama, kotow similarly to him, and he blesses them, laying both hands on their heads and repeating a short formula. Sometimes the dorje is used in blessing, as the cross is in Europe, and when a mass of people request a benediction, the Lama pronounces it from the door of the temple with outstretched arms, the people all being prostrate, with their foreheads touching the ground.

Throughout Sikkim, we were roused each morning at daybreak by this wild music, the convents being so numerous that we were always within hearing of it. To me it was always deeply impressive, sounding so foreign, and awakening me so effectually to the strangeness of the wild land in which I was wandering, and of the many new and striking objects it contained. After sleep, too, during which the mind has either been at rest, or carried away to more familiar subjects, the feelings of loneliness and sometimes even of despondency, conjured up, by this solemn music, were often almost oppressive.

Ascending from Neongong, we reached that pass from the Teesta to the Great Rungeet, which I had crossed on the 22nd; and this time we had a splendid view, down both the valleys, of the rivers, and the many spars from the ridge communicating between Tendong and Mainom, with many scattered villages and patches of cultivation. Near the top I found a plant of “Praong,” (a small bamboo), in full seed; this sends up many flowering branches from the root, and but few leaf-bearing ones; and after maturing its seed, and giving off suckers from the root, the parent plant dies. The fruit is a dark, long grain, like rice; it is boiled and made into cakes, or into beer, like Murwa.

Looking west from the summit, no fewer than ten monastic establishments with their temples, villages and cultivation, were at once visible, in the valley of the Great Rungeet, and in those of its tributaries; namely, Changachelling, Raklang, Dholi, Molli, Catsuperri, Dhoobdi, Sunnook, Powhungri, Pemiongchi and Tassiding, all of considerable size, and more or less remarkable in their sites, being perched on spurs or peaks at elevations varying from 3000 to 7000 feet, and commanding splendid prospects.

We encamped at Lingcham, where I had halted on

the 21st, and the weather being fine, I took bearings of all the convents and mountains around. There is much cultivation here, and many comparatively rich villages, all occupying flat-shouldered spurs from Mainom. The houses are large, and the yards are full of animals familiar to the eye but not to the ear. The cows of Sikkim, though generally resembling the English in stature, form, and colour, have humps, and grunt rather than low; and the cocks wake the morning with a prolonged howling screech, instead of the shrill crow of chanticleer.

Hence we descended north-west to the Great Rungeet, opposite Tassiding; which is one of the oldest monastic establishments in Sikkim, and one we were very anxious to visit. The descent lay through a forest of tropical trees, where small palms, vines, peppers, Pandanus, wild plantain, and Pothos, were interlaced in an impenetrable jungle, and air-plants clothed the trees.