Dr. Campbell is ordered to appear at Durbar — Lamas called to council — Threats — Searcity of food — Arrival of Dewan — Our jailer, Thoba-sing — Temperature, etc., at Tumloong — Services of Goompas — Lepcha girl — Jew’s-harp — Terror of servants — Ilam-sing’s family — Interview with Dewan — Remonstrances — Dewan feigns sickness — Lord Dalhousie’s letter to Rajah — Treatment of Indo-Chinese — Concourse of Lamas — Visit of Tchebu Lama — Close confinement — Dr. Campbell’s illness — Conference with Amlah — Relaxation of confinement — Pemiongchi Lama’s intercession — Escape of Nimbo — Presents from Rajah, Ranee and people — Protestations of friendship — Mr. Lushington sent to Dorjiling — Leave Tumloong — Cordial farewell — Dewan’s merchandise — Gangtok Kajee — Dewan’s pomp — Governor-General’s letter — Dikkeeling — Suspicion of poison — Dinner and pills — Tobacco — Bhotanese colony — Katong-ghat on Teesta — Wild lemons — Sepoys’ insolence — Dewan alarmed — View of Dorjiling — Threats of a rescue — Fears of our escape — Tibet flutes — Negotiate our release — Arrival at Dorjiling — Dr. Thomson joins me — Movement of troops at Dorjiling — Seizure of Rajah’s Terai property.

Since his confinement, Dr. Campbell had been desired to attend the Durbar for the purpose of transacting business, but had refused to go, except by compulsion, considering that in the excited state of the authorities, amongst whom there was not one person of responsibility or judgment, his presence would not only be useless, but he might be exposed to further insult or possibly violence.

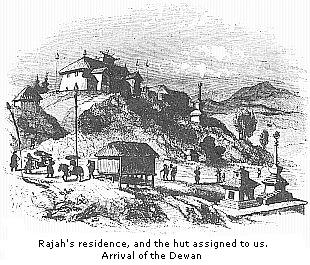

On the 15th of November we were informed that the Dewan was on his way from Tibet: of this we were glad, for knave as he was, we had hitherto considered him to possess sense and understanding. His agents were beginning to find out their mistake, and summoned to

council the principal Lamas and Kajees of the country, who, to a man, repudiated the proceedings, and refused to attend. Our captors were extremely anxious to induce us to write letters to Dorjiling, and sent spies of all kinds to offer us facilities for secret correspondence. The simplicity and clumsiness with which these artifices were attempted would have been ludicrous under other circumstances; while the threat of murdering Campbell only alarmed us, inasmuch as it came from people too stupid to be trusted. We made out that all Sikkim people were excluded from Dorjiling, and the Amlah consequently could not conceal their anxiety to know what had befallen their letters to government.

Meanwhile we were but scantily fed, and our imprisoned coolies got nothing at all. Our guards, were supplied with a handful of rice or meal as the day’s allowance; they were consequently grumbling,* and were daily reduced in number. The supplies of rice from the Terai, beyond Dorjiling, were cut off by the interruption of communication, and the authorities evidently could not hold us long at this rate: we sent up complaints, but of course received no answer.

The Dewan arrived in the afternoon in great state; carried in an English chair given him by Campbell some years before, habited in a blue silk cloak lined with lambskin, and wearing an enormous straw hat with a red tassel,

* The Rajah has no standing army; not even a body-guard, and these men were summoned to Tumloong before our arrival: they had no arms and received no pay, but were fed when called out on duty. There is no store for grain, no bazaar or market, in any part of the country, each family growing little enough for its own wants and no more; consequently Sikkim could not stand on the defensive for a week. The Rajah receives his supply of grain in annual contributions from the peasantry, who thus pay a rent in kind, which varies from little to nothing, according to the year, etc. He had also property of his own in the Terai, but the slender proceeds only enabled him to trade with Tibet for tea, etc.

and black velvet butterflies on the flapping brim. He was accompanied by a household of women, who were laden with ornaments, and wore boots, and sat astride on ponies; many Lamas were also with him, one of whom wore a broad Chinese-like hat covered with polished copper foil. Half a dozen Sepoys with matchlocks preceded him, and on approaching Tumloong, bawled out his titles, dignities, etc., as was formerly the custom in England.

At Dorjiling our seizure was still unknown: our letters were brought to us, but we were not allowed to answer them. Now that the Dewan had arrived, we hoped to come to a speedy explanation with him, but he shammed sickness, and sent no answer to our messages; if indeed he

received them. Our guards were reduced to one Sepoy with a knife, who was friendly; and a dirty, cross-eyed fellow named Thoba-sing, who, with the exception of Tchebu Lama, was the only Bhoteea about the Durbar who could speak Hindostanee, and who did it very imperfectly: he was our attendant and spy, the most barefaced liar I ever met with, even in the east; and as cringing and obsequious when alone with us, as he was to his masters on other occasions, when he never failed to show off his authority over us in an offensive manner. Though he was the most disagreeable fellow we were ever thrown in contact with, I do not think that he was therefore selected, but solely from his possessing a few words of Hindostanee, and his presumed capability of playing the spy.

The weather was generally drizzling or rainy, and we were getting very tired of our captivity; but I beguiled the time by carefully keeping my meteorological register,* and by reducing many of my previous observations. Each morning we were awakened at daybreak by the prolonged echos of the conchs, trumpets, and cymbals, beaten by the priests before the many temples in the valley: wild and pleasing sounds, often followed by

* During the thirty days spent at Tumloong, the temperature was mild and equable, with much cloud and drizzle, but little hard rain; and we experienced violent thunder-storms, followed by transient sunshine. Unlike 1848, the rains did not cease this year before the middle of December; nor had there been one fine month since April. The mean temperature, computed from 150 observations, was 50·2°, and from the maximum and minimum thermometer 49·6°, which is a fair approximation to the theoretical temperature calculated for the elevation and month, and allows a fall of 1° for 320 feet of ascent. The temperature during the spring (from 50 observations) varied during the day from 2·4° to 5·8° higher than that of the air, the greatest differences occurring morning and evening. The barometric tide amounted to 0·091 between 9.50 a.m. and 4 p.m., which is less than at the level of the plains of India, and more than at any greater elevation than Tumloong. The air was always damp, nearly saturated at night, and the mean amount of humidity for ninety-eight observations taken during the day was only 0·850, corresponding to a dew-point of 49·6°, or 5·2° below that of the air.

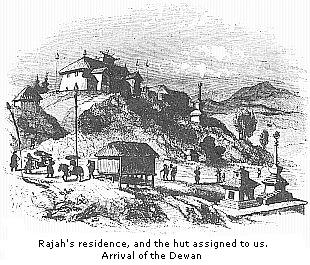

their choral chants. After dark we sat over the fire, generally in company with a little Lepcha girl, who was appointed to keep us in fire-wood, and who sat watching our movements with childish curiosity. Dolly, as we christened her, was a quick child and a kind one, intolerably dirty, but very entertaining from her powers of mimicry. She was fond of hearing me whistle airs, and procured me a Tibetan Jews’-harp,* with which, and coarse tobacco, which I smoked out of a Tibetan brass pipe, I wiled away the dark evenings, whilst my cheerful companion amused himself with an old harmonicon, to the enchantment of Dolly and our guards and neighbours.

The messengers from Dorjiling were kept in utter ignorance of our confinement till their arrival at Tumloong, when they were cross-questioned, and finally sent to us. They gradually became too numerous, there being only one apartment for ourselves, and such of our servants as

* This instrument (which is common in Tibet) is identical with the European, except that the tongue is produced behind the bow, in a strong steel spike, by which the instrument is held firmer to the mouth.

were not imprisoned elsewhere. Some of them were frightened out of their senses, and the state of abject fear and trembling in which one Limboo arrived, and continued for nearly a week, was quite distressing* to every one except Dolly, who mimicked him in a manner that was irresistibly ludicrous. Whether he had been beaten or threatened we could not make out, nor whether he had heard of some dark fate impending over ourselves—a suspicion which would force itself on our minds; especially as Thoba-sing had coolly suggested to the Amlah the dispatching of Campbell, as the shortest way of getting out of the scrape! We were also ignorant whether any steps were being taken at Dorjiling for our release, which we felt satisfied must follow any active measures against these bullying cowards, though they themselves frequently warned us that we should be thrown into the Teesta if any such were pursued.

So long as our money lasted, we bought food, for the Durbar had none to give; and latterly my ever charitable companion fed our guards, including Dolly and Thoba-sing, in pity to their pinched condition. Several families sent us small presents, especially that of the late estimable Dewan, Ilam-sing, whose widow and daughters lived close by, and never failed to express in secret their sympathy and good feeling.

Tchebu Lama’s and Meepo’s families were equally forward in their desire to serve us; but they were marked men, and could only communicate by stealth.

* It amounted to a complete prostration of bodily and mental powers: the man trembled and started when spoken to, or at any noise, a cold sweat constantly bedewed his forehead, and he continued in this state for eight days. No kindness on Campbell’s part could rouse him to give any intelligible account of his fears or their cause. His companions said he had lost his goroo, i.e., his charm, which the priest gives him while yet a child, and which he renews or gets re-sanctified as occasion requires. To us the circumstance was extremely painful.

Our coolies were released on the 18th, more than half starved, but the Sirdars were still kept in chains or the stocks: some were sent back to Dorjiling, and the British subjects billetted off amongst the villagers, and variously employed by the Dewan: my lad, Cheytoong, was set to collect the long leaves of a Tupistra, called “Purphiok,” which yield a sweet juice, and were chopped up and mixed with tobacco for the Dewan’s hookah.

November 20th.—The Dewan, we heard this day, ignored all the late proceedings, professing to be enraged with his brother and the Amlah, and refusing to meddle in the matter. This was no doubt a pretence: we had sent repeatedly for an explanation with himself or the Rajah, from which he excused himself on the plea of ill-health, till this day, when he apprized us that he would meet Campbell, and a cotton tent was pitched for the purpose.

We went about noon, and were received with great politeness and shaking of hands by the Dewan, the young Gangtok Kajee, and the old monk who had been present at my examination at Phadong. Tchebu Lama’s brother was also there, as a member of the Amlah, lately taken into favour; while Tchebu himself acted as interpreter, the Dewan speaking only Tibetan. They all sat cross-legged on a bamboo bench on one side, and we on chairs opposite them: walnuts and sweetmeats were brought us, and a small present in the Rajah’s name, consisting of rice, flour, and butter.

The Dewan opened the conversation both in this and another conference, which took place on the 22nd, by requesting Campbell to state his reasons for having desired these interviews. Neither he nor the Amlah seemed to have the smallest idea of the nature and consequences of the acts they had committed, and they therefore anxiously

sought information as to the view that would be taken of them by the British Government. They could not see why Campbell should not transact business with them in his present condition, and wanted him to be the medium of communication between themselves and Calcutta. The latter confined himself to pointing out his own views of the following subjects:—1. The seizing and imprisoning of the agent of a friendly power, travelling unarmed and without escort, under the formal protection of the Rajah, and with the authority of his own government. 2. The aggravation of this act of the Amlah, by our present detention under the Dewan’s authority. 3. The chance of collision, and the disastrous consequences of a war, for which they had no preparation of any kind. 4. The impossibility of the supreme government paying any attention to their letters so long as we were illegally detained.

All this sank deep into the Dewan’s heart: he answered, “You have spoken truth, and I will submit it all to the Rajah;” but at the same time he urged that there was nothing dishonourable in the imprisonment, and that the original violence being all a mistake, it should be overlooked by both parties. We parted on good terms, and heard shortly after the second conference that our release was promised and arranged: when a communication* from Dorjiling changed their plans, the Dewan conveniently fell sick on the spot, and we were thrown back again.

In the meantime, however, we were allowed to write to our friends, and to receive money and food, of which

* I need scarcely say that every step was taken at Dorjiling for our release, that the most anxious solicitude for our safety could suggest. But the first communication to the Rajah, though it pointed out the heinous nature of his offence, was, through a natural fear of exasperating our captors, couched in very moderate language. The particulars of our seizure, and the reasons for it, and for our further detention, were unknown at Dorjiling, or a very different line of policy would have been pursued.

we stood in great need. I transmitted a private account of the whole affair to the Governor-General, who was unfortunately at Bombay, but to whose prompt and vigorous measures we were finally indebted for our release. His lordship expedited a despatch to the Rajah, such as the latter was accustomed to receive from Nepal, Bhotan, or Lhassa, and such as alone commands attention from these half-civilized Indo-Chinese, who measure power by the firmness of the tone adopted towards them; and who, whether in Sikkim, Birmah, Siam, Bhotan, or China, have too long been accustomed to see every article of our treaties contravened, with no worse consequences than a protest or a threat, which is never carried into execution till some fatal step calls forth the dormant power of the British Government.*

The end of the month arrived without bringing any prospect of our release, whilst we were harassed by false reports of all kinds. The Dewan went on the 25th to a hot bath, a few hundred feet down the hill; he was led past our hut, his burly frame tottering as if in great weakness, but a more transparent fraud could not have been practised: he was, in fact, lying on his oars, pending further negotiations. The Amlah proposed that Campbell should sign a bond, granting immunity for all past offences on their part, whilst they were to withdraw the letter of grievances against him. The Lamas cast horoscopes for the

* We forget that all our concessions to these people are interpreted into weakness; that they who cannot live on an amicable equality with one another, cannot be expected to do so with us; that all our talk of power and resources are mere boasts to habitual bullies, so long as we do not exert ourselves in the correction of premeditated insults. No Government can be more tolerant, more sincerely desirous of peace, and more anxious to confine its sway within its own limits than that of India, but it can only continue at peace by demanding respect, and the punctilious enforcement of even the most trifling terms in the treaties it makes with Indo-Chinese.

future, little presents continually arrived for us, and the Ranee sent me some tobacco, and to Campbell brown sugar and Murwa beer. The blacksmiths, who had been ostentatiously making long knives at the forge hard by, were dismissed; troops were said to be arriving at Dorjiling, and a letter sternly demanding our release bad been received.

The Lamas of Pemiongchi, Changachelling, Tassiding, etc., and the Dewan’s enemies, and Tchebu Lama’s friends, began to flock from all quarters to Tumloong, demanding audience of the Rajah, and our instant liberation. The Dewan’s game was evidently up; but the timidity of his opponents, his own craft, and the habitual dilatoriness of all, contributed to cause endless delays. The young Gangtok Kajee tried to curry favour with us, sending word that he was urging our release, and adding that he had some capital ponies for us to see on our way to Dorjiling! Many similar trifles showed that these people had not a conception of the nature of their position, or of that of an officer of the British Government.

The Tchebu Lama visited us only once, and then under surveillance; he renewed his professions of good faith, and we had every reason to know that he had suffered severely for his adherence to us, and consistent repudiation of the Amlah’s conduct; he was in great favour with his brother Lamas, but was not allowed to see the Rajah, who was said to trust to him alone of all his counsellors. He told us that peremptory orders had arrived from Calcutta for our release, but that the Amlah had replied that they would not acknowledge the despatch, from its not bearing the Governor-General’s great seal! The country-people refusing to be saddled with the keep of our coolies, they were sent to Dorjiling in small parties, charged to say that we were free, and following them.

The weather continued rainy and bad, with occasionally a few hours of sunshine, which, however, always rendered the ditch before our door offensive: we were still prevented leaving the hot, but as a great annual festival was going on, we were less disagreeably watched. Campbell was very unwell, and we had no medicine; and as the Dewan, accustomed to such duplicity himself, naturally took this for a ruse, and refused to allow us to send to Dorjiling for any, we were more than ever convinced that his own sickness was simulated.

On the 2nd and 3rd December we had further conferences with the Dewan, who said that we were to be taken to Dorjiling in six days, with two Vakeels from the Rajah. The Pemiongchi Lama, as the oldest and most venerated in Sikkim, attended, and addressed Campbell in a speech of great feeling and truth. Having heard, he said, of these unfortunate circumstances a few days ago, he had come on feeble limbs, and though upwards of seventy winters old, as the representative of his holy brotherhood, to tender advice to his Rajah, which he hoped would be followed: Since Sikkim had been connected with the British rule, it had experienced continued peace and protection; whereas before they were in constant dread of their lives and properties, which, as well as their most sacred temples, were violated by the Nepalese and Bhotanese. He then dwelt upon Campbell’s invariable kindness and good feeling, and his exertions for the benefit of their country, and for the cementing of friendship, and hoped he would not let these untoward events induce an opposite course in future but that he would continue to exert his influence with the Governor-General in their favour.

The Dewan listened attentively; he was anxious and

perplexed, and evidently losing his presence of mind: he talked to us of Lhassa and its gaieties, dromedaries, Lamas, and everything Tibetan; offered to sell us ponies cheap, and altogether behaved in a most, undignified manner; ever and anon calling attention to his pretended sick leg, which he nursed on his knee. He gave us the acceptable news that the government at Calcutta had sent up an officer to carry on Campbell’s duties, which had alarmed him exceedingly. The Rajah, we were told, was very angry at our seizure and detention; he had no fault to find with the Governor-General’s agent, and hoped he would be continued as such. In fact, all the blame was thrown on the brothers of the Dewan, and of the Gangtok Kajee, and more irresponsible stupid boors could not have been found on whom to lay it, or who would have felt less inclined to commit such folly if it had not been put on them by the Dewan. On leaving, white silk scarfs were thrown over our shoulders, and we went away, still doubtful, after so many disappointments, whether we should really be set at liberty at the stated period.

Although there was so much talk about our leaving, our confinement continued as rigorous as ever. The Dewan curried favour in every other way, sending us Tibetan wares for purchase, with absurd prices attached, he being an arrant pedlar. All the principal families waited on us, desiring peace and friendship. The coolies who had not been dismissed were allowed to run away, except my Bhotan Sirdar, Nimbo, against whom the Dewan was inveterate;* he, however, managed soon afterwards to break a great chain with which his legs were shackled, and

* The Sikkim people are always at issue with the Bhotanese. Nimbo was a runaway slave of the latter country, who had been received into Sikkim, and retained there until he took up his quarters at Dorjiling.

marching at night, eluded a hot pursuit, and proceeded to the Teesta, swam the river, and reached Dorjiling in eight days; arriving with a large iron ring on each leg, and a link of several pounds weight attached to one.

Parting presents arrived from the Rajah on the 7th, consisting of ponies, cloths, silks, woollens, immense squares of butter, tea, and the usual et ceteras, to the utter impoverishment of his stores: these he offered to the two Sahibs, “in token of his amity with the British government, his desire for peace, and deprecation of angry discussions.” The Ranee sent silk purses, fans, and such Tibetan paraphernalia, with an equally amicable message, that “she was most anxious to avert the consequences of whatever complaints had gone forth against Dr. Campbell, who might depend on her strenuous exertions to persuade the Rajah to do whatever he wished!” These friendly messages were probably evoked by the information that an English regiment, with three guns, was on its way to Sikkim, and that 300 of the Bhaugulpore Rangers had already arrived there. The government of Bengal sending another agent* to Dorjiling, was also a contingency they had not anticipated, having fully expected to get rid of any such obstacle to direct communication with the Governor-General.

A present from the whole population followed that of the Ranee, coupled with earnest entreaties that Campbell would resume his position at Dorjiling; and on the following day forty coolies mustered to arrange the baggage. Before we left, the Ranee sent three rupees to buy a

* Mr. Lushington, the gentleman sent to conduct Sikkim affairs during Dr. Campbell’s detention: to whom I shall ever feel grateful for his activity in our cause, and his unremitting attention to every little arrangement that could alleviate the discomforts and anxieties of our position.

yard of chalé and some gloves, accompanying them with a present of white silk, etc., for Mrs. Campbell, to whom the commission was intrusted: a singular instance of the insouciant simplicity of these odd people.

The 9th of December was a splendid and hot day, one of the very few we had had during our captivity. We left at noon, descending the hill through an enormous crowd of people, who brought farewell presents, all wishing us well. We were still under escort as prisoners of the Dewan, who was coolly marching a troop of forty unloaded mules and ponies, and double that number of men’s loads of merchandize, purchased during the summer in Tibet, to trade with at Dorjiling and the Titalya fair! His impudence or stupidity was thus quite inexplicable; treating us as prisoners, ignoring every demand of the authorities at Dorjiling, of the Supreme Council of Calcutta, and of the Governor-General himself; and at the same time acting as if he were to enter the British territories on the most friendly and advantageous footing for himself and his property, and incurring so great an expense in all this as to prove that he was in earnest in thinking so.

Tchebu Lama accompanied us, but we were not allowed to converse with him. We halted at the bottom of the valley, where the Dewan invited us to partake of tea; from this place he gave us mules* or ponies to ride, and we ascended to Yankoong, a village 3,867 feet above the sea. On the following day we crossed a high ridge from the Ryott valley to that of the Rungmi; where we camped at Tikbotang (alt. 3,763 feet), and, on the 11th at Gangtok Sampoo, a few miles lower down the same valley.

We were now in the Soubahship of the Gangtok Kajee; a

* The Tibet mules are often as fine as the Spanish: I rode one which had performed a journey from Choombi to Lhassa in fifteen days, with a man and load.

member of the oldest and most wealthy family in Sikkim; he had from the first repudiated the late acts of the Amlah, in which his brother had taken part, and had always been hostile to the Dewan. The latter conducted himself with disagreeable familiarity towards us, and hauteur towards the people; he was preceded by immense kettle-drums, carried on men’s backs, and great hand-bells, which were beaten and rung on approaching villages; on which occasions he changed his dress of sky-blue for yellow silk robes worked with Chinese dragons, to the indignation of Tchebu Lama, an amber robe in polite Tibetan society being sacred to royalty and the Lamas. We everywhere perceived unequivocal symptoms of the dislike with which he was regarded. Cattle were driven away, villages deserted, and no one came to pay respects, or bring presents, except the Kajees, who were ordered to attend, and his elder brother, for whom he had usurped an estate near Gangtok.

On the 13th, he marched us a few miles, and then halted for a day at Serriomsa (alt. 2,820 feet), at the bottom of a hot valley full of irrigated rice-crops and plantain and orange-groves. Here the Gangtok Kajee waited on us with a handsome present, and informed us privately of his cordial hatred of the “upstart Dewan,” and hopes for his overthrow; a demonstration of which we took no notice.* The Dewan’s brother (one of the Amlah) also sent a large present, but was ashamed to appear. Another letter reached the Dewan here, directed to the Rajah; it was from the Governor-General at Bombay, and had been sent across the country by special messengers:

* Nothing would have been easier than for the Gangtok Kajee, or any other respectable man in Sikkim, to have overthrown the Dewan and his party; but these people are intolerably apathetic, and prefer being tyrannized over to the trouble of shaking off the yoke.

it demanded our instant release, or his Raj would be forfeited; and declared that if a hair of our heads were touched, his life should be the penalty.

The Rajah was also incessantly urging the Dewan to hasten us onwards as free men to Dorjiling, but the latter took all remonstrances with assumed coolness, exercised his ponies, played at bow and arrow, intruded on us at mealtimes to be invited to partake, and loitered on the road, changing garments and hats, which he pestered us to buy. Nevertheless, be was evidently becoming daily more nervous and agitated.

From the Rungmi valley we crossed on the 14th southward to that of Runniok, and descended to Dikkeeling, a large village of Dhurma Bhoteeas (Bhotanese), which is much the most populous, industrious, and at the same time turbulent, in Sikkim. It is 4,950 feet above the sea, and occupies many broad cultivated spurs facing the south. This district once belonged to Bhotan, and was ceded to the Sikkim Rajah by the Paro Pilo,* in consideration of some military services, rendered by the former in driving off the Tibetans, who had usurped it for the authorities of Lhassa. Since then the Sikkim and Bhotan people have repeatedly fallen out, and Dikkeeling has become a refuge for runaway Bhotanese, and kidnapping is constantly practised on this frontier.

The Dewan halted us here for three days, for no assigned cause. On the 16th, letters arrived, including a most kind and encouraging one from Mr. Lushington, who had taken charge of Campbell’s office at Dorjiling. Immediately after arriving, the messenger was seized with violent vomitings and gripings: we could not help suspecting poison,

* The temporal sovereign, in contra-distinction to the Dhurma Rajah, or spiritual sovereign of Bhotan.

especially as we were now amongst adherents of the Dewan, and the Bhotanese are notorious for this crime. Only one means suggested itself for proving this, and with Campbell’s permission I sent my compliments to the Dewan, with a request for one of his hunting dogs to eat the vomit. It was sent at once, and performed its duty without any ill effects. I must confess to having felt a malicious pleasure in the opportunity thus afforded of showing our jailor how little we trusted him; feeling indignant at the idea that he should suppose he was making any way in our good opinion by his familiarities, which we were not in circumstances to resist.

The crafty fellow, however, outwitted me by inviting us to dine with him the same day, and putting our stomachs and noses to a severe test. Our dinner was served in Chinese fashion, but most of the luxuries, such as béche-de-mer, were very old and bad. We ate, sometimes with chop-sticks, and at others with Tibetan spoons, knives, and two-pronged forks. After the usual amount of messes served in oil and salt water, sweets were brought, and a strong spirit. Thoba-sing, our filthy, cross-eyed spy, was waiter, and brought in every little dish with both hands, and raised it to his greasy forehead, making a sort of half bow previous to depositing it before us. Sometimes he undertook to praise its contents, always adding, that in Tibet none but very great men indeed partook of such sumptuous fare. Thus he tried to please both us and the Dewan, who conducted himself with pompous hospitality, showing off what he considered his elegant manners and graces. Our blood boiled within us at being so patronised by the squinting ruffian, whose insolence and ill-will had sorely aggravated the discomforts of our imprisonment.

Not content with giving us what he considered a magnificent dinner (and it had cost him some trouble), the

Dewan produced a little bag from a double-locked escritoire, and took out three dinner-pills, which he had received as a great favour from the Rimbochay Lama, and which were a sovereign remedy for indigestion and all other ailments; he handed one to each of us, reserving the third for himself. Campbell refused his; but there appeared no help for me, after my groundless suspicion of poison, and so I swallowed the pill with the best grace I could. But in truth, it was not poison I dreaded in its contents, so much as being compounded of some very questionable materials, such as the Rimbochay Lama blesses and dispenses far and wide. To swallow such is a sanctifying work, according to Boodhist superstition, and I believe there was nothing in the world, save his ponies, to which the Dewan attached a greater value.

To wind up the feast, we had pipes of excellent mild yellow Chinese tobacco called “Tseang,” made from Nicotiana rustica, which is cultivated in East Tibet, and in West China according to MM. Huc and Gabet. It resembles in flavour the finest Syrian tobacco, and is most agreeable when the smoke is passed through the nose. The common tobacco of India (Nicotiana Tabacum) is much imported into Tibet, where it is called “Tamma,” (probably a corruption of the Persian “Toombac,”) and is said to fetch the enormous price of 30s. per lb. at Lhassa, which is sixty times its value in India. Rice at Lhassa, when cheap, sells at 2s. for 5 lbs.; it is, as I have elsewhere said, all bought up for rations for the Chinese soldiery.

The Bhotanese are more industrious than the Lepchas, and better husbandmen; besides having superior crops of all ordinary grains, they grow cotton, hemp, and flax. The cotton is cleansed here as elsewhere, with a simple gin. The Lepchas use no spinning wheel, but a spindle and

distaff; their loom, which is Tibetan is a very complicated one framed of bamboo; it is worked by hand, without beam treddle, or shuttle.

On the 18th we were marched, three miles only, to Singdong (alt. 2,116 feet), and on the following day five miles farther, to Katong Ghat (alt. 750 feet), on the Teesta river, which we crossed with rafts, and camped on the opposite bank, a few miles above the junction of this river with the Great Rungeet. The water, which is sea-green in colour, had a temperature of 53·5° at 4 p.m., and 51·7° the following morning; its current was very powerful. The rocks, since leaving Tunlloong, had been generally micaceous, striking north-west, and dipping north-east. The climate was hot, and the vegetation on the banks tropical; on the hills around, lemon-bushes (“Kucheala,” Lepcha) were abundant, growing apparently wild.

The Dewan was now getting into a very nervous and depressed state; he was determined to keep up appearances before his followers, but was himself almost servile to us; he caused his men to make a parade of their arms, as if to intimidate us, and in descending narrow gullies we had several times the disagreeable surprise of finding some of his men at a sudden turn, with drawn bows and arrows pointed towards us. Others gesticulated with their long knives, and made fell swoops at soft plantain-stems; but these artifices were all as shallow as they were contemptible, and a smile at such demonstrations was generally answered with another from the actors.

From Katong we ascended the steep east flank of Tendong or Mount Ararat, through forests of Sal and long-leaved pine, to Namten (alt. 4,483 feet), where we again halted two days. The Dingpun Tinli lived near and

waited on us with a present, which, with all others that had been brought, Campbell received officially, and transferred to the authorities at Dorjiling.

The Dewan was thoroughly alarmed at the news here brought in, that the Rajah’s present of yaks, ponies, etc., which had been sent forward, had been refused at Dorjiling; and equally so at the clamorous messages which reached him from all quarters, demanding our liberation; and at the desertion of some of his followers, on hearing that large bodies of troops were assembling at Dorjiling. Repudiated by his Rajah and countrymen, and paralysed between his dignity and his ponies, which he now perceived would not be welcomed at the station, and which were daily losing flesh, looks, and value in these hot valleys, where there is no grass pasture, he knew not what olive-branch to hold out to our government, except ourselves, whom he therefore clung to as hostages.

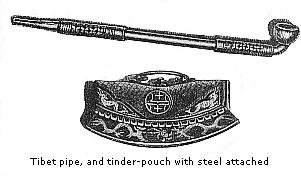

On the 22nd of December he marched us eight miles further, to Cheadam, on a bold spur 4,653 feet high, overlooking the Great Rungeet, and facing Dorjiling, from which it was only twenty miles distant. The white bungalows of our friends gladdened our eyes, while the new barracks erecting for the daily arriving troops struck terror into the Dewan’s heart. The six Sepoys* who had marched valiantly beside us for twenty days, carrying the muskets given to the Rajah the year before by the Governor-General, now lowered their arms, and vowed that if a red coat crossed the Great Rungeet, they would throw down their guns and run away. News arrived

* These Sepoys, besides the loose red jacket and striped Lepcha kirtle, wore a very curious national black hat of felt, with broad flaps turned up all round: this is represented in the right-hand figure. A somewhat similar bat is worn by some classes of Nepal soldiery.

that the Bhotan inhabitants of Dorjiling headed by my bold Sirdar Nimbo, had arranged a night attack for our release; an enterprise to which they were quite equal, and in which they have had plenty of practice in their own misgoverned country. Watch-fires gleamed amongst the bushes, we were thrust into a doubly-guarded house, and bows and arrows were ostentatiously levelled so as to rake the doorway, should we attempt to escape. Some of the ponies were sent back to Dikkeeling, though the Dewan still clung to his merchandise and the feeble hope of traffic. The confusion increased daily, but though Tchebu Lama looked brisk and confident, we were extremely anxious;

scouts were hourly arriving from the road to the Great Rungeet, and if our troops had advanced, the Dewan might have made away with us from pure fear.

In the forenoon he paid us a long visit, and brought some flutes, of which he gave me two very common ones of apricot wood from Lhassa, producing at the same time a beautiful one, which I believe he intended for Campbell, but his avarice got the better, and he commuted his gift into the offer of a tune, and pitching it in a high key, he went through a Tibetan air that almost deafened us by its screech. He tried bravely to maintain his equanimity, but as we preserved a frigid civility and only spoke when addressed, the tears would start from his eyes in the pauses of conversation. In the evening he came again; he was excessively agitated and covered with perspiration, and thrust himself unceremoniously between us on the bench we occupied. As his familiarity increased, he put his arm round my neck, and as he was armed with a small dagger, I felt rather uneasy about his intentions, but he ended by forcing on my acceptance a coin, value threepence, for he was in fact beside himself with terror.

Next morning Campbell received a hint that this was a good opportunity for a vigorous remonstrance. The Dewan came with Tchebu Lama, his own younger brother (who was his pony driver), and the Lassoo Kajee. The latter had for two months placed himself in an attitude of hostility opposite Dorjiling, with a ragged company of followers, but he now sought peace and friendship as much as the Dewan; the latter told us he was waiting for a reply to a letter addressed to Mr. Lushington, after which he would set us free. Campbell said: “As you appear to have made up your mind, why not dismiss us at once?” He

answered that we should go the next day at all events: Here I came in, and on hearing from Campbell what had passed, I added, that he had better for his own sake let us go at once; that the next day was our great and only annual Poojah (religious festival) of Christmas, when we all met; whereas he and his countrymen had dozens in the year. As for me, he knew I had no wife, nor children, nor any relation, within thousands of miles, and it mattered little where I was, he was only bringing ruin on himself by his conduct to me as the Governor-General’s friend; but as regarded Campbell, the case was different; his home was at Dorjiling, which was swarming with English soldiers, all in a state of exasperation, and if he did not let us depart before Christmas, he would find Dorjiling too hot to hold him, let him offer what reparation he might for the injuries he had done us. I added: “We are all ready to go—dismiss us.” The Dewan again turned to Campbell, who said, “I am quite ready; order us ponies at once, and send our luggage after us.” He then ordered the ponies, and three men, including Meepo, to attend us; whereupon we walked out, mounted, and made off with all speed.

We arrived at the cane bridge over the Great Rungeet at 4 p.m., and to our chagrin found it in the possession of a posse of ragged Bhoteeas, though there were thirty armed Sepoys of our own at the guard-house above. At Meepo’s order they cut the network of fine canes by which they had rendered the bridge impassable, and we crossed. The Sepoys at the guard-house turned out with their clashing arms and bright accoutrements, and saluted to the sound of bugles; scaring our three companions, who ran back as fast as they could go. We rode up that night to Dorjiling, and I arrived at 8 p.m. at Hodgson’s house,

where I was taken for a ghost, and received with shouts of welcome by my kind friend and his guest Dr. Thomson, who had been awaiting my arrival for upwards of a month.

Thus terminated our Sikkim captivity, and my last Himalayan exploring journey, which in a geographical point of view had answered my purposes beyond my most sanguine expectations, though my collections had been in a great measure destroyed by so many untoward events. It enabled me to survey the whole country, and to execute a map of it, and Campbell had further gained that knowledge of its resources which the British government should all along have possessed, as the protector of the Rajah and his territories.

It remains to say a few words of the events that succeeded our release, in so far as they relate to my connection with them. The Dewan moved from Cheadam to Namtchi, immediately opposite Dorjiling, where he remained throughout the winter. The supreme government of Bengal demanded of the Rajah that he should deliver up the most notorious offenders, and come himself to Dorjiling, on pain of an army marching to Tumloong to enforce the demand; a step which would have been easy, as there were neither troops, arms, ammunition, nor other means of resistance, even had there been the inclination to stop us, which was not the case. The Rajah would in all probability have delivered himself up at Tumloong, throwing himself on our mercy, and the army would have sought the culprits in vain, both the spirit and the power to capture them being wanting on the part of the people and their ruler.

The Rajah expressed his willingness, but pleaded his inability to fulfil the demand, whereupon the threat was

repeated, and additional reinforcements were moved on to Dorjiling. The general officer in command at Dinapore was ordered to Dorjiling to conduct operations: his skill and bravery had been proved during the progress of the Nepal war so long ago as 1815. From the appearance of the country about Dorjiling, he was led to consider Sikkim to be impracticable for a British army. This was partly owing to the forest-clad mountains, and partly to the fear of Tibetan troops coming to the Rajah’s aid, and the Nepalese* taking the opportunity to attack us. With the latter we were in profound peace, and we had a resident at their court; and I have elsewhere shown the impossibility of a Tibet invasion, even if the Chinese or Lhassan authorities were inclined to interfere in the affairs of Sikkim, which they long ago formally declined doing in the case of aggressions of the Nepalese and Bhotanese, the Sikkim Rajah being under British protection.†

* Jung Bahadoor was at this time planning his

visit to England, and to his honour I must say, that on hearing of

our imprisonment he offered to the government at Calcutta to

release us with a handful of men. This he would no doubt have

easily effected, but his offer was wisely declined, for the

Nepalese (as I have elsewhere stated) want Sikkim and Bhotan too,

and we had undertaken the protection of the former country, mainly

to keep the Nepalese out of it.

† The general officer considered that our troops would have

been cut to pieces if they entered the country; and the late

General Sir Charles Napier has since given evidence to the same

effect. Having been officially asked at the time whether I would

guide a party into the country, and having drawn up (at the request

of the general officer) plans for the purpose, and having given it

as my opinion that it would not only have been feasible but easy to

have marched a force in peace and safety to Tumloong, I feel it

incumbent on me here to remark, that I think General Napier, who

never was in Sikkim, and wrote from many hundred miles’

distance, must have misapprehended the state of the case. Whether

an invasion of Sikkim was either advisable or called for, was a

matter in which I had no concern: nor do I offer an opinion as to

the impregnability of the country if it were defended by natives

otherwise a match for a British force, and having the advantage of

position. I was not consulted with reference to any difference of

opinion between the civil and military powers, such as seems to

have called for the expression of Sir Charles Napier’s

opinion on this matter, and which appears to be considerably

overrated in his evidence.

The general officer honoured me with his

friendship at Dorjiling, and to Mr. Lushington, I am, as I have

elsewhere stated, under great obligations for his personal

consideration and kindness, and vigorous measures during my

detention. On my release and return to Dorjiling, any interference

on my part would have been meddling with what was not my concern. I

never saw, nor wished to see, a public document connected with the

affair, and have only given as many of the leading features of the

case as I can vouch for, and as were accessible to any other

bystander.

There were not wanting offers of leading a company of soldiers to Tumloong, rather than that the threat should have twice been made, and then withdrawn; but they were not accepted. A large body of troops was however, marched from Dorjiling, and encamped on the north bank of the Great Rungeet for some weeks: but after that period they were recalled, without any further demonstration; the Dewan remaining encamped the while on the Namtchi hill, not three hours’ march above them. The simple Lepchas daily brought our soldiers milk, fowls, and eggs, and would have continued to do so had they proceeded to Tumloong, for I believe both Rajah and people would have rejoiced at our occupation of the country.

After the withdrawal of the troops, the threat was modified into a seizure of the Terai lands, which the Rajah had originally received as a free gift from the British, and which were the only lucrative or fertile estates he possessed. This was effected by four policemen taking possession of the treasury (which contained exactly twelve shillings, I believe), and announcing to the villagers the confiscation of the territory to the British government, in which they gladly acquiesced. At the same time there was annexed to it the whole southern part of Sikkim, between the Great Rungeet and the plains of India, and from Nepal on the west to the Bhotan frontier and the Teesta river on the east; thus confining the Rajah to his

mountains, and cutting off all access to the plains, except through the British territories. To the inhabitants (about 5000 souls) this was a matter of congratulation, for it only involved the payment of a small fixed tax in money to the treasury at Dorjiling, instead of a fluctuating one in kind, with service to the Rajah, besides exempting them from further annoyance by the Dewan. At the present time the revenues of the tract thus acquired have doubled, and will very soon be quadrupled: every expense of our detention and of the moving of troops, etc., has been already repaid by it, and for the future all will be clear profit; and I am given to understand that this last year it has realized upwards of 30,000 rupees (£3000).

Dr. Campbell resumed his duties immediately afterwards, and the newly-acquired districts were placed under his jurisdiction. The Rajah still begs hard for the renewal of old friendship, and the restoration of his Terai land, or the annual grant of £300 a year which he formerly received. He has forbidden the culprits his court, but can do no more. The Dewan, disgraced and turned out of office, is reduced to poverty, and is deterred from entering Tibet by the threat of being dragged to Lhassa with a rope round his neck. Considering, however, his energy, a rare quality in these countries, I should not be surprised at his yet cutting a figure in Bhotan, if not in Sikkim itself: especially if, at the Rajah’s death, the British government should refuse to take the country under its protection. The Singtam Soubah and the other culprits live disgraced at their homes. Tchebu Lama has received a handsome reward, and a grant of land at Dorjiling, where he resides, and whence he sends me his salaams by every opportunity.