The Project Gutenberg EBook of With Moore at Corunna, by G. A. Henty This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: With Moore at Corunna Author: G. A. Henty Posting Date: June 2, 2012 [EBook #8651] Release Date: August, 2005 First Posted: July 29, 2003 [Last updated: October 6, 2013] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK WITH MOORE AT CORUNNA *** Produced by Ted Garvin, S.R.Ellison, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team

[Illustration: TERENCE FINDS THAT THE SEA-HORSE HAS BEEN BADLY MAULED BETWEEN-DECKS.]

BY

Author of "With Cochrane the Dauntless," "A Knight of the White Cross," "In Freedom's Cause," "St. Bartholomew's Eve," "Wulf the Saxon," etc.

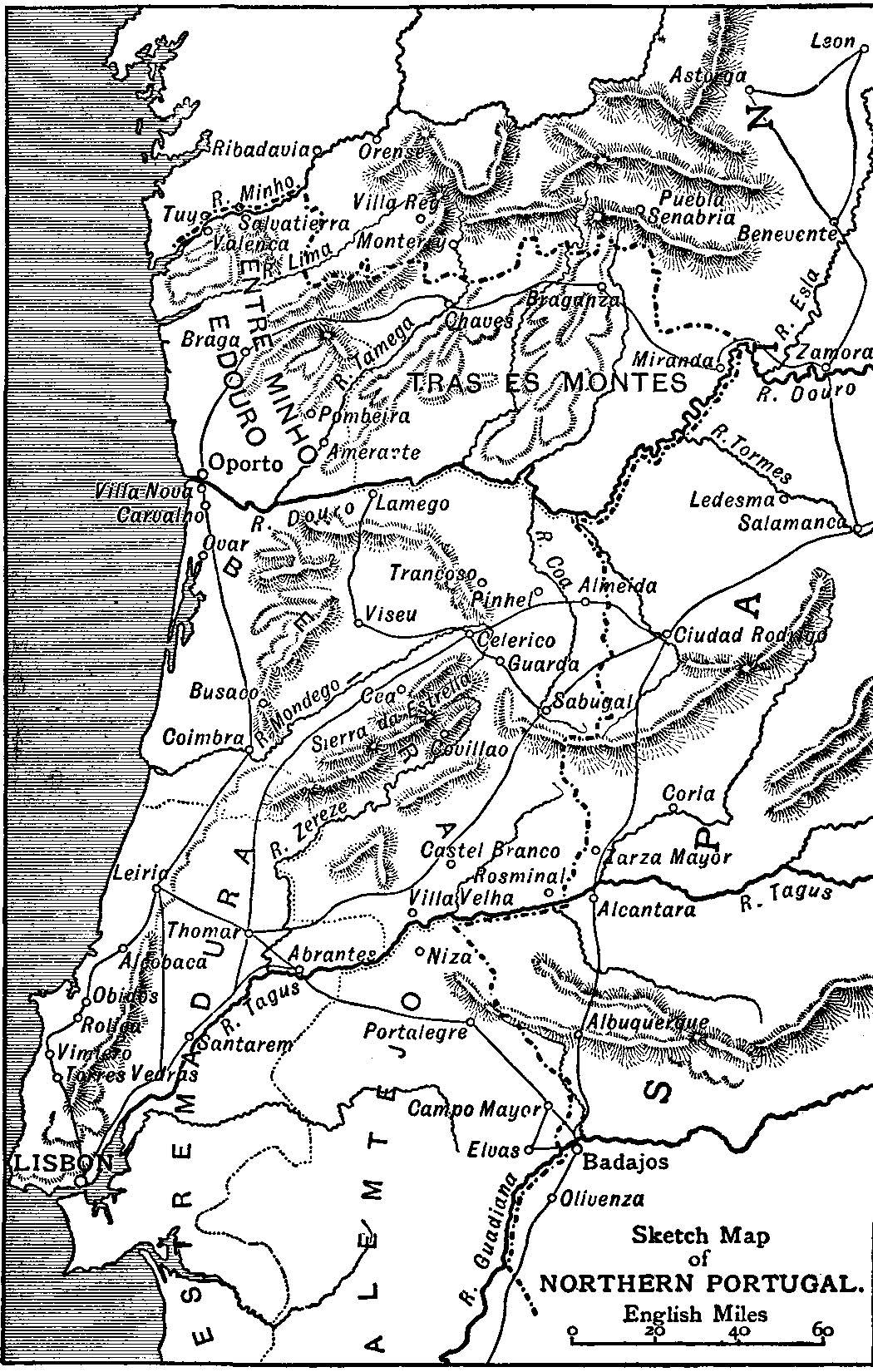

From the termination of the campaigns of Marlborough--at which time the British army won for itself a reputation rivalled by that of no other in Europe--to the year when the despatch of a small army under Sir Arthur Wellesley marked the beginning of another series of British victories as brilliant and as unbroken as those of that great commander, the opinion had gained ground in Europe that the British had lost their military virtues, and that, although undoubtedly powerful at sea, they could have henceforth but little influence in European affairs. It is singular that the revival of Britain's activity began under a Government which was one of the most incapable that ever controlled the affairs of the country. Had their deliberate purpose been to render nugatory the expedition which--after innumerable vacillations and changes of purpose--they despatched to Portugal, they could hardly have acted otherwise than they did.

Their agents in the Peninsula were men singularly unfitted for the position. Then the Government divided the commands among their generals and admirals, sending to each absolutely contradictory orders, and when at last they brought themselves to appoint one to the supreme command, they changed that commander six times in the course of a year. While lavishing enormous sums of money, arms, clothing, and materials of war upon the Spaniards, who wasted or pocketed them, they kept their own army unsupplied with money, transport, or clothes. Unsupported by the home authorities, the British commanders had yet to struggle with the faithlessness, mendacity, and inertness of the Portuguese and Spanish authorities, and were hampered with obstacles such as never beset a British commander before. Still, in spite of this, British genius and valour triumphed over all difficulties, and Wellesley delivered Lisbon and compelled the French army to surrender.

Then again, Moore, by his marvellous march, checked the course of victory of Napoleon and saved Spain for a time. Cradock organized an army, and Wellesley hurled back Soult's invasion of the north, and drove his army, a dispirited and worn-out mass of fugitives, across the frontier, and in less than a year from the commencement of the campaign carried the war into Spain. So far I have endeavoured to sketch the course of these events in the present volume. But the whole course of the Peninsular War was far too long to be condensed in a single book, except in the form of history pure and simple; therefore, I have been obliged to divide it into two volumes; and I propose next year to follow up the adventures of my present hero, who had the good fortune, with Trant, Wilson, and other British officers, to attain the command of a body of native irregulars, acting in connection with the movements of the British army.

Yours sincerely,

G. A. HENTY.

CHAP.

I. THE MAYO FUSILIERS

II. TWO DANGERS

III. DISEMBARKED

IV. UNDER CANVAS

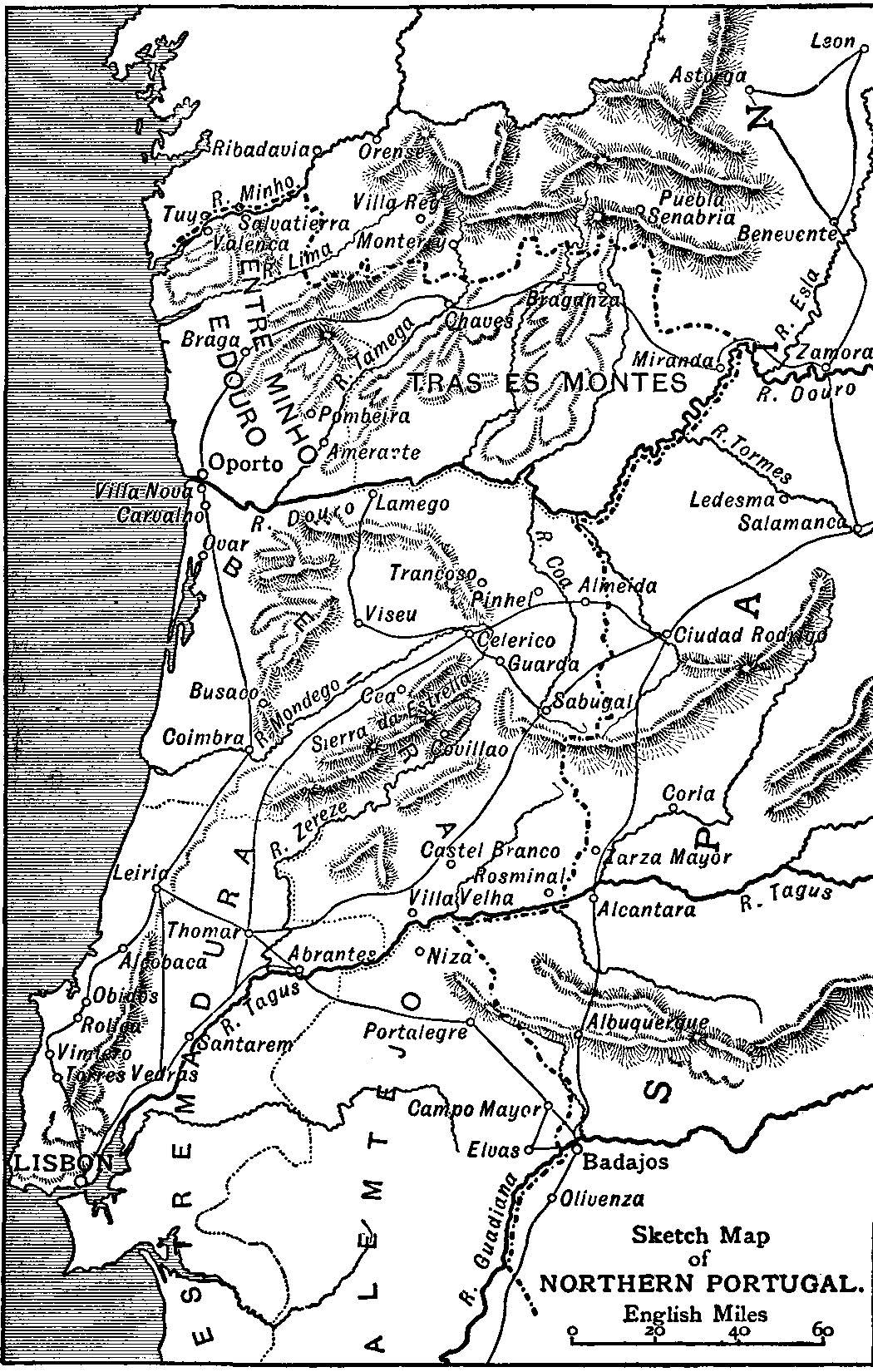

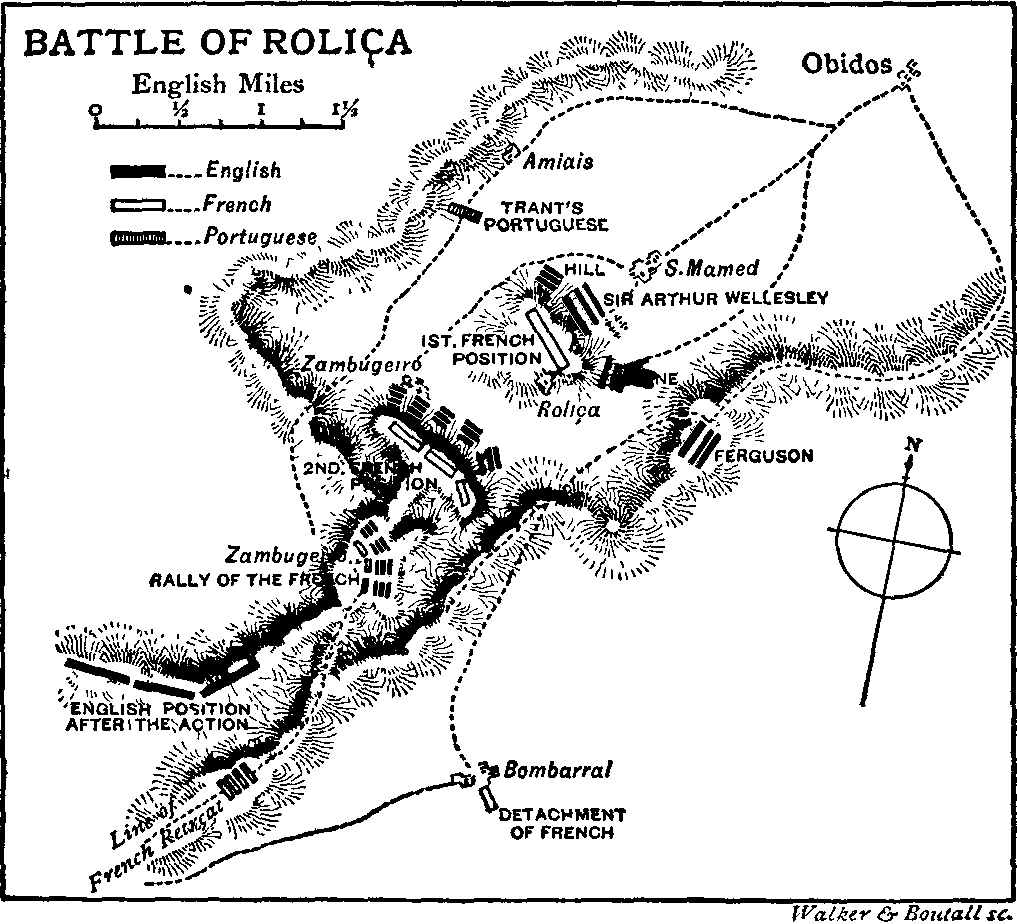

V. ROLICA AND VIMIERA

VI. A PAUSE

VII. THE ADVANCE

VIII. A FALSE ALARM

IX. THE RETREAT

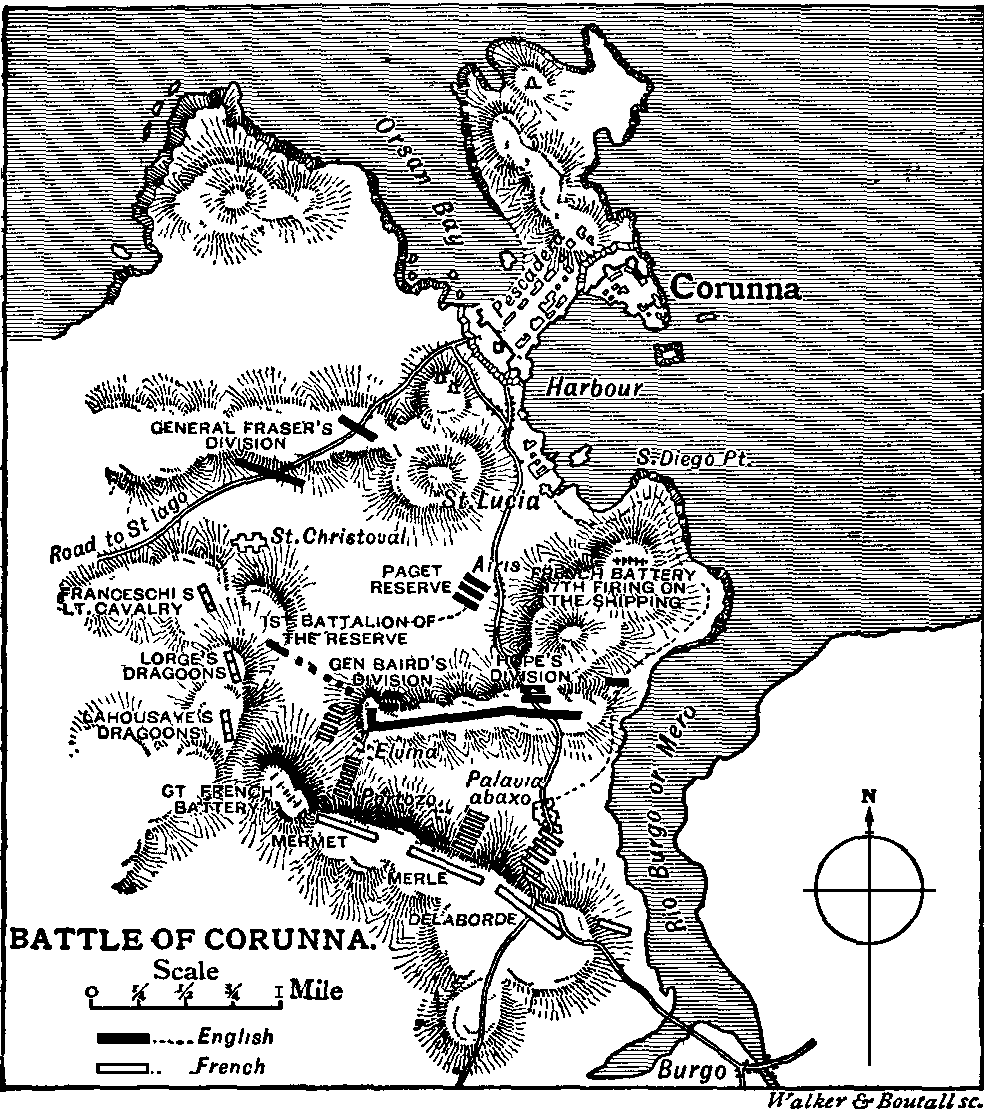

X. CORUNNA

XI. AN ESCAPE

XII. A DANGEROUS MISSION

XIII. AN AWKWARD POSITION

XIV. AN INDEPENDENT COMMAND

XV. THE FIRST SKIRMISH

XVI. IN THE PASSES

XVII. AN ESCAPE

XVIII. MARY O'CONNOR

XIX. CONFIRMED IN COMMAND

XX. WITH THE MAYOS

XXI. PORTUGAL FREED

XXII. NEWS FROM HOME

TERENCE FINDS THAT THE SEA-HORSE HAS BEEN BADLY MAULED BETWEEN-DECKS

TWO FRENCH PRIVATEERS BEAR DOWN UPON THE SEA-HORSE

"I SHOULD NOT HAVE MINDED BEING HIT, FATHER, IF YOU HAD ESCAPED"

"I AM TOLD THAT YOU WISH TO SPEAK TO ME, GENERAL"

"WHAT DO YOU MEAN, TERENCE?... WE WOULD HAVE THRASHED THEM OUT OF THEIR BOOTS IN NO TIME"

"POOR OLD JACK! HE HAS CARRIED ME WELL EVER SINCE I GOT HIM AT TORRES VEDRAS"

TERENCE RECEIVES A PRESENT OF A HORSE FROM SIR JOHN CRADOCK

"IN THE NAME OF THE JUNTA I DEMAND THAT AMMUNITION," SAID CORTINGOS

"THE FRENCH CAVALRY RODE UP TOWARDS THE SQUARES, BUT WERE MET WITH HEAVY VOLLEYS"

"MACWITTY WAS STANDING COVERING THE TWO BOATMEN WITH HIS PISTOLS"

TERENCE BIDS GOOD-BYE TO HIS COUSIN, MARY O'CONNOR

"WHO ARE YOU, SIR, AND WHAT TROOPS ARE THESE?" SIR ARTHUR ASKED, SHARPLY

"What am I to do with you, Terence? It bothers me entirely; there is not a soul who will take you, and if anyone would do so, you would wear out his patience before a week's end; there is not a dog in the regiment that does not put his tail between his legs and run for his bare life if he sees you; and as for the colonel, he told me only the other day that he had so many complaints against you, that he was fairly worn out with them."

"That was only his way, father; the colonel likes a joke as well as any of them."

"Yes, when it is not played on himself; but you haven't even the sense to respect persons, and it is well for you that he could not prove that it was you who fastened the sparrow to the plume of feathers on his shako the other day, and no one noticed it till the little baste began to flutter just as he came on to parade, and nigh choked us all with trying to hold in our laughter, while the colonel was nearly suffocated with passion. It was lucky you were able to prove that you had gone off at daylight fishing, and that no one had seen you anywhere near his quarters. By my faith, if he could have proved it was you he would have had you turned out of the barrack gate, and word given to the sentries that you were not to be allowed to pass in again."

"I could have got over the wall, father," the boy said, calmly; "but mind, I never said that it was I who fastened the sparrow in his shako."

"Because I never asked you, Terence; but it does not need the asking. What I am to do with you I don't know. Your Uncle Tim would not take you if I were to go down upon my knees to him. You were always in his bad books, and you finished it when you fired off that blunderbuss in his garden as he was passing along in the twilight, and yelled out 'Death to the Protestants!'"

The boy burst into a fit of laughter. "How could I tell that he was going to fall flat upon the ground and shout a million murders, when I fired straight into the air?"

"Well, you did for yourself there, Terence. Not that the old man would ever have taken to you, for he never forgave my marriage with his niece; still, he might have left you some money some day, seeing that there is no one nearer to him, and it would have come in mighty useful, for you are not likely to get much from me. But we are no nearer the point yet. What am I to do with you at all? Here is the regiment ordered on foreign service and likely to have sharp work, and not a place where I can stow you. It beats me altogether!"

"Why not take me with you, father?"

"I have thought of that, but you are too young entirely."

"I am nearly sixteen, father. I am sure I am as tall as many boys of seventeen, and as strong too. Why should I not go? I am certain I could stand roughing it as well as Dick Ryan, who is a good bit over sixteen. Could I not go as a volunteer? Or I might enlist; the doctor would pass me quick enough."

"O'Flaherty would pass you if you were a baby in arms; he is as full of mischief as you are, and has not much more discretion; but you could not carry a musket, full cartridge-box, and kit for a long day's march."

"I can carry a gun through a long day's shooting, dad; but you might make me your soldier servant."

"Bedad, I should fare mighty badly, Terence; still as I don't see anything else for you, I must try and take you somehow, even if you have to go as a drummer. I will talk it over with the colonel, though I doubt whether he has forgotten that sparrow yet."

"He would not bear malice, dad, even if he were sure that it was me--which he cannot be."

The speaker was Captain O'Connor of his Majesty's regiment of Mayo Fusiliers, now under orders to proceed to Portugal to form part of the force that was being despatched under Sir Arthur Wellesley to assist the Portuguese in resisting the advance of the French. He was a widower, and Terence was his only child. The boy had been brought up in the regiment. His mother had died when he was nine years old, and Terence had been allowed by his father to run pretty nearly wild. He picked up a certain amount of education, for he was as sharp at lessons as at most other things. His mother had taught him to read and write, and the officers and their wives were always ready to lend him books; and as, during the hours when drill and exercise were going on, he had plenty of time to himself, he had got through a very large amount of desultory reading, and, having a retentive memory, knew quite as much as most lads of his age, although the knowledge was of a much more irregular kind.

He was a general favourite among the officers and men of the regiment, though his tricks got him into frequent scrapes, and more than one prophesied that his eventual fate was likely to be hanging. He was great at making acquaintances among the country people, and knew the exact spot where the best fishing could be had for miles round; he had also been given leave to shoot on many of the estates in the neighbourhood.

His father had, from the first, absolutely forbidden him to associate with the drummer boys.

"I don't mind your going into the men's quarters," he said, "you will come to no harm there, but among the boys you might get into bad habits; some of them are thorough young scamps. With the men you would always be one of their officers' sons, while with the boys you would soon become a mere playmate."

As he grew older, Terence, being a son of one of the senior officers, became a companion of the ensigns, and one or other of them generally accompanied him on his fishing excursions, and were not unfrequently participators in his escapades, several of which were directed against the tranquillity of the inhabitants of Athlone. One night the bells of the three churches had been rung simultaneously and violently, and the idea that either the town was in flames, or that the French had landed, or that the whole country was up in arms, brought all the inhabitants to their doors in a state of violent excitement and scanty attire. No clew was ever obtained as to the author of this outrage, nor was anyone able to discover the origin of the rumour that circulated through the town, that a large amount of gunpowder had been stored in some house or other in the market-place, and that on a certain night half the town would be blown into the air.

So circumstantial were the details that a deputation waited on Colonel Corcoran, and a strong search-party was sent down to examine the cellars of all the houses in the market-place and for some distance round. These and some similar occurrences had much alarmed the good people of Athlone, and it was certain that more than one person must have been concerned in them.

"I have come, Colonel," Captain O'Connor said, when he called upon his commanding officer, "to speak to you about Terence."

The colonel smiled grimly. "It is a comfort to think that we are going to get rid of him, O'Connor; he is enough to demoralize a whole brigade, to say nothing of a battalion, and the worst of it is he respects no one. I am as convinced as can be that it was he who fastened that baste of a bird in my shako the other day, and made me the laughing stock of the whole regiment on parade. Faith, I could not for the life of me make out what was the matter, there was a tugging and a jumping and a fluttering overhead, and I thought the shako was going to fly away. It fairly gave me a scare, for I thought the shako had gone mad, and that the divil was in it. I have often overlooked his tricks for your sake, but when it comes to his commanding officer, it is too serious altogether."

"Well, you see, Colonel, the lad proved clearly enough that he was out of the way at the time; and besides, you know he has given you many a hearty laugh."

"He has that," the colonel admitted.

"And, moreover," Captain O'Connor went on, "even if he did do this, which I don't know, for I never asked him" ("Trust you for that," the colonel muttered), "you are not his commanding officer, though you are mine, and that is the matter that I came to speak to you about. You see there is no one in whose charge I can leave him, and the lad wants to go with us; he would enlist as a drummer, if he could go no other way, and when he got out there I should get the adjutant to tell him off as my soldier servant."

"It would not do, O'Connor," the colonel laughed.

"Then I thought, Colonel, that possibly he might go as a volunteer--most regiments take out one or two young fellows, who have not interest enough to obtain a commission."

"He is too young, O'Connor; besides, the boy is enough to corrupt a whole regiment; he has made half the lads as wild as he is himself. Sure you can never be after asking me to saddle the regiment with him, now that there is a good chance of getting quit of him altogether."

"I think that he would not be so bad when we are out there, Colonel; it is just because he has nothing to do that he gets into mischief. With plenty of hard work and other things to think of I don't believe that he would be any trouble."

"Do you think that you can answer for him, O'Connor?"

"Indeed and I cannot," the captain laughed; "but I will answer for it that he will not joke with you, Colonel. The lad is really steady enough, and I am sure that if he were in the regiment he would not dream of playing tricks with his commanding officer, whatever else he might do."

"That goes a long way towards removing my objection," the colonel said, with a twinkle in his eye; "but he is too young for a volunteer--a volunteer is the sort of man to be the first to climb a breach, or to risk his life in some desperate enterprise, so as to win a commission. But there is another way. I had a letter yesterday from the Horse Guards, saying that as I am two ensigns short, they had appointed one who will join us at Cork, and that they gave me the right of nominating another. I own that Terence occurred to me, but sixteen is the youngest limit of age, and he must be certified and all that by the doctor. Now Daly is away on leave, and is to join us at Cork; but O'Flaherty would do; still, I don't know how he would get over the difficulty about the age."

"Trust him for that. I am indeed obliged to you, Colonel."

"Don't say anything about it, O'Connor; if we had been going to stay at home I don't think that I could have brought myself to take him into the regiment, but as we are going on service he won't have much opportunity for mischief, and even if he does let out a little--not at my expense, you know--a laugh does the men good when they are wet through and their stomachs are empty." He rang a bell. "Orderly, tell the adjutant and Doctor O'Flaherty that I wish to see them. Mr. Cleary," he went on, as soon as the former entered, "I have been requested by the Horse Guards to nominate an ensign, so as to fill up our ranks before starting, and I have determined to give the appointment to Terence O'Connor."

"Very well, sir, I am glad to hear it; he is a favourite with us all, but I am afraid that he is under age."

"Is there any regular form to be filled up?"

"None that I know of in the case of officers, sir. I fancy they pass some sort of medical examination at the Horse Guards, but, of course, in this case it would be impossible. Still, I should say that, in writing to state that you have nominated him, it would be better to send a medical certificate, and certainly it ought to be mentioned that he is of the right age."

At this moment the assistant-surgeon entered. "Doctor O'Flaherty," the colonel said, "I wish you to write a certificate to the effect that Terence O'Connor is physically fit to take part in a campaign as an officer."

"I can do that, Colonel, without difficulty; he is as fit as a fiddle, and can march half the regiment off their legs."

"Yes, I know that, but there is one difficulty, Doctor, he is under the regulation age."

O'Flaherty thought for a moment and then sat down at the table, and taking a sheet of paper, be began:

I certify that Terence O' Connor is going on for seventeen years of age, he is five feet eight in height, thirty-four inches round the chest, is active, and fully capable of the performance of his duties as an officer either at home or abroad.

Then he added another line and signed his name.

"As a member of a learned profession, Colonel," he said, gravely, "I would scorn to tell a lie even for the son of Captain O'Connor;" and he passed the paper across to him.

The colonel looked grave, and Captain O'Connor disappointed. He was reassured, however, when his commanding officer broke into a laugh.

"That will do well, O'Flaherty," he said; "I thought that you would find some way of getting us out of the difficulty."

"I have told the strict truth, Colonel," the doctor said, gravely. "I have certified that Terence O'Connor is going on for seventeen; I defy any man to say that he is not. He will get there one of these days, if a French bullet does not stop him on the way, a contingency that it is needless for me to mention."

"I suppose that it is not strictly regular to omit the date of his birth," the colonel said; "but just at present I expect they are not very particular. I suppose that that will do, Mr. Cleary?"

"I think that you can countersign that, Colonel," the adjutant said, with a laugh. "The Horse Guards do not move very rapidly, and by the time that letter gets to London we may be on board ship, and they would hardly bother to send a letter for further particulars to us in Spain, but will no doubt gazette him at once. The fact, too--which of course you will mention--that he is the son of the senior captain of your regiment, will in itself render them less likely to bother about the matter."

"Well, just write out the letter of nomination, Cleary; I am a mighty bad hand at doing things neatly."

The adjutant drew a sheet of foolscap to him and wrote:--

To the Adjutant-general, Horse Guards,

Sir, I have the honour to inform you that, in accordance with the privilege granted to me in your communication of--

and he looked at the colonel.

"The 14th inst.," the latter said, after consulting the letter.

--I beg to nominate as an ensign in this regiment, Terence O' Connor, the son of Captain Lawrence O' Connor, its senior captain. I inclose certificate of Assistant-surgeon O' Flaherty,--the surgeon being at present absent on leave--certifying to his physical fitness for a commission in his Majesty's service. Mr. O' Connor having been brought up from childhood in the regiment is already perfectly acquainted with the work, and will therefore be able to take up his duties without difficulty. This fact has had some influence in my choice, as a young officer who had to be taught all his duties would have been of no use for service in the field for a considerable time after landing in Portugal. Relying on the nomination being approved by the commander-in-chief, I shall at once put him on the staff of the regiment for foreign service, as there will be no time to wait your reply.

I have the honour to be

Your humble, obedient servant,

Then he left a space, and added:

Colonel Mayo Fusiliers.

"Now, if you will sign it, Colonel, the matter will be complete, and I will send it off with O'Flaherty's certificate today."

"That is a good stroke, Cleary," the colonel said, as he read it aloud. "They will see that it is too late to raise any questions, and the 'going on for seventeen' will be accepted as sufficient."

He touched a bell.

"Orderly, tell Mr. Terence O'Connor that I wish to see him."

Terence was sitting in a state of suppressed excitement at his father's quarters. He had a strong belief that the matter would be managed somehow, for he knew that the colonel had no malice in his disposition, and would not let the episode of the bird--for which he was now heartily sorry--stand in the way. On receiving the message he at once went across to the colonel's quarters. The latter rose and held out his hand to him as he entered.

"Terence O'Connor," he said, "I am pleased to be able to inform you that from the present moment you are to consider yourself an officer in his Majesty's Mayo Fusiliers. The Horse Guards have given me the privilege of nominating a gentleman to the vacant ensigncy, and I have had great pleasure in nominating your father's son. Now, lad," he said, in different tone of voice, "I feel sure that you will do credit my nomination, and that you will keep your love of fun and mischief within reasonable bounds."

"I will try to do so, Colonel," the lad said, in a low voice, "and I am grateful indeed for the kindness that you have shown me. I have always hoped that some day I might obtain a commission in your regiment, but never even hoped that it would be until after I had done something to deserve it. Indeed I did not think that it was even possible that I could obtain a commission until----"

"Tut, tut, lad, don't say a word about age! Doctor O'Flaherty had certified that you are going on for seventeen, which is quite sufficient for me, and at any rate you will see that boyish tricks are out of place in the case of an officer going on for seventeen. Now, your father had best take you down into the town and get you measured for your uniforms at once. You must make them hurry on with his undress clothes, O'Connor. I should not bother about full-dress till we get back again; it is not likely to be wanted, and the lad will soon grow out of them. If there should happen to be full-dress parade in Portugal, Cleary will put him on as officer of the day, or give him some duties that will keep him from parade. We may get the route any day, and the sooner he gets his uniform the better."

Two days later Terence took his place on parade as an officer of the regiment. He had witnessed such numberless drills that he had picked up every word of command, knew his proper place in every formation, and fell into the work as readily as if he had been at it for years. He had been heartily congratulated by the officers of the regiment.

"I am awfully glad that you are one of us, Terence," Dick Ryan said. "I don't know what we should have done without you. I expect we shall have tremendous fun in Portugal."

"I expect we shall, Dick; but we shall have to be careful. We shall be on active service, you see, and from what they say of him I don't think Sir Arthur Wellesley is the sort of man to appreciate jokes."

"No, I should say not. Of course, we shall have to draw in a bit. It would not do to set the bells of Lisbon ringing."

"I should think not, Dick. Still, I dare say we shall have plenty of fun, and at any rate we are likely, from what they say, to have plenty of fighting. I don't expect the Portuguese will be much good, and as there are forty or fifty thousand Frenchmen in Portugal, we shall have all our work to do, unless they send out a much bigger force than is collecting at Cork. It is a pity that the 10,000 men who have been sent out to Sweden on what my father says is a fool's errand are not going with us instead. We might make a good stand-up fight of it then, whereas I don't see that with only 6,000 or 7,000 we can do much good against Junot's 40,000."

"Oh, I dare say we shall get on somehow!" Dick said, carelessly. "Sir Arthur knows what he is about, and it is our turn to do something now. The navy has had it all its own way so far, and it is quite fair that we should do our share. I have a brother in the navy, and the fellows are getting too cheeky altogether. They seem to think that no one can fight but themselves. Except in Egypt we have never had a chance at all of showing we can lick the French just as easily on land as we can at sea."

"I hope we shall, Dick. They have certainly had a great deal more practice at it than we have."

"Now I think we ought to do something here that they will remember us for before we start, Terence."

"Well, if you do, I am not with you this time, Dick. I am not going to begin by getting in the colonel's bad books after he has been kind enough to nominate me for a commission. I promised him that I would try and not get into any scrapes, and I am not going to break my word. When we once get out there I shall be game to join in anything that is not likely to make a great row, but I have done with it for the present."

"I should like to have one more good bit of fun," Ryan said; "but I expect you are right, Terence, in what you say about yourself, and it is no use our thinking to humbug Athlone again if you are not in it with us; besides, they are getting too sharp. They did not half turn out last time, and, indeed, we had a narrow escape of being caught. Well, I shall be very glad when we are off; it is stupid work waiting for the route, with all leave stopped, and we not even allowed to go out for a day's fishing."

Three days later the expected order arrived. As the baggage had all been packed up, that which was to be left behind being handed over to the care of the barrack-master, and a considerable portion of the heavy baggage sent on by cart, there was no delay. Officers and men were alike delighted that the period of waiting had come to an end, and there was loud cheering in the barrack-yard as soon as the news came. At daybreak next morning the rest of the baggage started under a guard, and three hours later the Mayo Fusiliers marched through the town with their band playing at their head, and amid the cheers of the populace.

As yet the martial spirit that was roused by the struggle in the Peninsula had scarcely begun to show itself, but there was a strong animosity to France throughout England, and a desire to aid the people of Spain and Portugal in their efforts for freedom. In Ireland, for the most part, there was no such feeling. Since the battle of the Boyne and the siege of Limerick, France had been regarded by the greater portion of the peasantry, and a section of the population of the towns, as the natural ally of Ireland, and there was a hope that when Napoleon had all Europe prostrate under his feet he would come as the deliverer of Ireland from the English yoke. Consequently, although the townspeople of Athlone cheered the regiment as it marched away, the country people held aloof from it as it passed along the road. Scowling looks from the women greeted it in the villages, while the men ostentatiously continued their work in the fields without turning to cast a glance at them.

Terence was not posted to his father's company, but was in that of Captain O'Driscol, although the lad himself would have preferred to be with Captain O'Grady, with whom he was a great favourite. The latter was one of the captains whose companies were unprovided with an ensign, and he had asked the adjutant to let him have the lad instead of the ensign who was to join at Cork.

"The matter has been settled the other way, O'Grady; in the colonel's opinion he will be much better with O'Driscol, who is more likely to keep him in order than you are."

O'Grady was one of the most original characters in the regiment. He was rather under middle height, and had a smooth face, a guileless and innocent expression, and a habit of opening his light-blue eyes as in wonder. His hair was short, and stuck up aggressively; his brogue was the strongest in the regiment; his blunders were innumerable, and his look of amazement at the laughter they called forth was admirably feigned, save that the twinkle of his eye induced a suspicion that he himself enjoyed the joke as well as anyone. His good-humour was imperturbable, and he was immensely popular both among men and officers.

"O'Driscol!" he repeated, in mild astonishment. "Do you mean to say that O'Driscol will keep him in better order than meself? If there is one man in this regiment more than another who would get on well with the lad it is meself, barring none."

"You would get on well enough with him, O'Grady, I have no doubt, but it would be by letting him have his own way, and in encouraging him in mischief of all kinds."

O'Grady's eyebrows were elevated, and his eyes expressed hopeless bewilderment.

"You are wrong entirely, Cleary; nature intended me for a schoolmaster, and it is just an accident that I have taken to soldiering. I flatter meself that no one looks after his subalterns more sharply than I do. My only fear is that I am too severe with them. I may be mild in my manners, but they know me well enough to tremble if I speak sternly to them."

"The trembling would be with amusement," the adjutant grumbled. "Well, the colonel has settled the matter, and Terence will be in Orders to-morrow as appointed to O'Driscol's company, and the other to yours."

"Thank you for nothing, Cleary," O'Grady said, with dignity. "You would have seen that under my tuition the lad would have turned out one of the smartest officers in the regiment."

"You have heard of the Spartan way of teaching their sons to avoid drunkenness, Captain O'Grady?"

"Divil a word, Cleary; but I reckon that the best way with the haythens was to keep them from touching whisky. It is what I always recommend to the men of my company when I come across one of them the worse for liquor."

The adjutant laughed. "That was not the Spartan way, O'Grady; but the advice, if taken, would doubtless have the same effect."

"And who were the Spartans at all?"

"I have not time to tell you now, O'Grady; I have no end of business on my hands."

"Thin what do you keep me talking here for? haven't I a lot of work on me hands too. I came in to ask a simple question, and instead of giving me a civil answer you kape me wasting my time wid your O'Driscols and your Spartans and all kinds of rigmarole. That is the worst of being in an Irish regiment, nothing can be done widout ever so much blather;" and Captain O'Grady stalked out of the orderly-room.

On the march Terence had no difficulty in obtaining leave from his captain to drop behind and march with his friend Dick Ryan. The marches were long ones, and they halted only at Parsonstown, Templemore, Tipperary, and Fermoy, as the colonel had received orders to use all speed. At each place a portion of the regiment was accommodated in the barracks, while the rest were quartered in the town. Late in the evening of the fifth day's march they arrived at Cork, and the next day went on board the two transports provided for them, and joined the fleet assembled in the Cove. Some of the ships had been lying there for nearly a month waiting orders, and the troops on board were heartily weary of their confinement. The news, however, that Sir Arthur Wellesley had been at last appointed to command them, and that they were to sail for Portugal, had caused great delight, for it had been feared that they might, like other bodies of troops, be shipped off to some distant spot, only to remain there for months and then to be brought home again.

Nothing, indeed, could exceed the vacillation and confusion that reigned in the English cabinet at that time. The forces of England were frittered away in small and objectless expeditions, the plans of action were changed with every report sent either by the interested leaders of insurrectionary movements in Spain, or by the signally incompetent men who had been sent out to represent England, and who distributed broadcast British money and British arms to the most unworthy applicants. By their lavishness and subservience to the Spaniards our representatives increased the natural arrogance of these people, and caused them to regard England as a power which was honoured by being permitted to share in the Spanish efforts against the French generals. General Spencer with 5,000 men was kept for months sailing up and down the coast of Spain and Portugal, receiving contradictory orders from home, and endeavouring in vain to co-operate with the Spanish generals, each of whom had his own private purposes, and was bent on gratifying personal ambitions and of thwarting the schemes of his rivals, rather than on opposing the common enemy.

Not only were the English ministry incapable of devising any plan of action, but they were constantly changing the naval and military officers of the forces. At one moment one general or admiral seemed to possess their confidence, while soon afterwards, without the slightest reason, two or three others with greater political influence were placed over his head; and when at last Sir Arthur Wellesley, whose services in India marked him as our greatest soldier, was sent out with supreme military power, they gave him no definite plan of action. General Spencer was nominally placed under his orders by one set of instructions, while another authorized him to commence operations in the south, without reference to Sir Arthur Wellesley. Admiral Purvis, who was junior to Admiral Collingwood, was authorized to control the operations of Sir Arthur, while Wellesley himself had scarcely sailed when Sir Hew Dalrymple was appointed to the chief command of the forces, Sir Harry Burrard was appointed second in command, and Sir Arthur Wellesley was reduced to the fourth rank in the army that he had been sent out to command, two of the men placed above him being almost unknown, they never having commanded any military force in the field.

The 9,000 men assembled in the Cove of Cork knew nothing of these things; they were going out under the command of the victor of Assaye to measure their strength against that of the French, and they had no fear of the result.

"I hope," Captain O'Grady said, as the officers of the wing of the regiment to which he belonged sat down to dinner for the first time on board the transport, "that we shall not have to keep together in going out."

"Why so, O'Grady?" another captain asked.

"Because there is no doubt at all that our ship is the fastest in the fleet, and that we shall get there in time to have a little brush with the French all to ourselves before the others arrive."

"What makes you think that she is the fastest ship here, O'Grady?"

"Anyone can see it with half an eye, O'Driscol. Look at her lines; she is a flyer, and if we are not obliged to keep with the others we shall be out of sight of the rest of them before we have sailed six hours."

"I don't pretend to know anything about her lines, O'Grady, but she looks to me a regular old tub."

"She is old," O'Grady admitted, reluctantly, "but give her plenty of wind and you will see how she can walk along."

There was a laugh all round the table; O'Grady's absolute confidence in anything in which he was interested was known to them all. His horse had been notoriously the most worthless animal in the regiment, but although continually last in the hunting field, O'Grady's opinion of her speed was never shaken. There was always an excuse ready; the horse had been badly shod, or it was out of sorts and had not had its feed before starting, or the going was heavy and it did not like heavy ground, or the country was too hilly or too flat for it. It was the same with his company, with his non-commissioned officers, with his soldier servant, a notoriously drunken rascal, and with his quarters.

O'Grady looked round in mild expostulation at the laugh.

"You will see," he said, confidently, "there can be no mistake about it."

Two days later a ship-of-war entered the harbour, the usual salutes were exchanged, then a signal was run up to one of her mast-heads, and again the guns of the forts pealed out a salute, and word ran through the transports that Sir Arthur Wellesley was on board. On the following day the fleet got under way, the transports being escorted by a line-of-battle ship and four frigates, which were to join Lord Collingwood's squadron as soon as they had seen their charge safe into the Tagus.

Before evening the Sea-horse was a mile astern of the rearmost ship of the convoy, and one of the frigates sailing back fired a gun as a signal to her to close up.

"Well, O'Grady, we have left the fleet, you see, though not in the way you predicted."

"Whist, man! don't you see that the captain is out of temper because they have all got to keep together, instead of letting him go ahead?"

Every rag of sail was now piled on to the ship, and as many of the others were showing nothing above their topgallant sails she rejoined the rest just as darkness fell.

"There, you see!" O'Grady said, triumphantly, "look what she can do when she likes."

"We do see, O'Grady. With twice as much sail up as anything else, she has in three hours picked up the mile she had lost."

"Wait until we get some wind."

"I hope we sha'n't get anything of the sort--at least no strong winds; the old tub would open every seam if we did, and we might think ourselves lucky if we got through it at all."

O'Grady smiled pleasantly, and said it was useless to argue with so obstinate a man.

"I am afraid O'Grady is wrong as usual," Dick Ryan said to Terence, who was sitting next to him. "When once he has taken an idea into his head nothing will persuade him that he is wrong; there is no doubt the Sea-horse is as slow as she can be. I suppose her owners have some interest with the government, or they would surely never have taken up such an old tub as a troop-ship."

The next day, in spite of the sail she carried, the Sea-horse lagged behind, and one of the frigates sailed back to her, and the captain shouted angry orders to the master to keep his place in the convoy.

"If we get any wind," O'Grady said, as the frigate bore up on her course again, "it will take all your time to keep up with her, my fine fellow. You see," he explained to Terence, "no vessel is perfect in all points; some like a good deal of wind, some are best in a calm. Now this ship wants wind."

"I think she does, Captain O'Grady," Terence replied, gravely. "At any rate her strong point is not sailing in a light wind."

"No," O'Grady admitted, regretfully; "but it is not the ship's fault. I have no doubt at all that her bottom is foul, and that she has a lot of barnacles and weeds twice as long as your body. That is the reason why she is a little sluggish."

"That may be it," Terence agreed; "but I should have thought that they would have seen to that before they sent her to Cork."

"It is like enough that her owners are well-wishers of Napoleon, Terence, and that it is out of spite that they have done it. There is no doubt that she is a wonderful craft."

"I am quite inclined to agree with you, Captain O'Grady, for as I have never seen a ship except when the regiment came back from India ten years ago, I am no judge of one."

"It is the eye, Terence. I can't say that I have been much at sea myself, except on that voyage out and home; but I have an eye for ships, and can see their good points at a glance. You can take it from me that she is a wonderful vessel."

"She would look all the better if her sails were a bit cleaner, and not so patched," Terence said, looking up.

"She might look better to the eye, lad, but no doubt the owners know what they are doing, and consider that she goes better with sails that fit her than she would with new ones."

Terence burst into a roar of laughter. O'Grady, as usual, looked at him in mild surprise.

"What are you laughing at, you young spalpeen?"

"I am thinking, Captain O'Grady," the lad said, recovering himself, "that it is a great pity you could not have obtained the situation of Devil's Advocate. I have read that years ago someone was appointed to defend Old Nick when the others were pitching into him, and to show that he was not as black as he was painted, but was a respectable gentleman who had been maligned by the world."

"No doubt there is a good deal to be said for him," O'Grady said, seriously. "Give a dog a bad name, you know, and you may hang him; and I have no doubt the Old One has been held responsible for lots of things he never had as much as the tip of his finger in at all, at all."

Seeing that his captain was about to pursue the matter much further, Terence, making the excuse that it was time he went down to see if the men's breakfast was all right, slipped off, and he and Dick Ryan had a hearty laugh over O'Grady's peculiarities.

"I think, O'Grady," Captain O'Driscol said, two days later, "we are going to have our opportunity, for unless I am mistaken there is going to be a change of weather. Those clouds banking up ahead look like a gale from the southwest."

Before night the wind was blowing furiously, and the Sea-horse taking green sea over her bows and wallowing gunwale under in the waves. At daylight, when they went on deck, gray masses of cloud were hurrying overhead and an angry sea alone met the eye. Not a sail was in sight, and the whole convoy had vanished.

"We are out of sight of the fleet, O'Grady," Captain O'Driscol said, grimly.

"I felt sure we should be," O'Grady said, triumphantly. "Sorra one of them could keep foot with us."

"They are ahead of us, man," O'Driscol said, angrily; "miles and miles ahead."

"Ahead, is it? You must know better, O'Driscol; though it is little enough you know of ships. You see we are close-hauled, and there is no doubt that that is the vessel's strong point. Why, we have dropped the rest of them like hot potatoes, and if this little breeze keeps on, maybe we shall be in the Tagus days and days before them."

O'Driscol was too exasperated to argue.

"O'Driscol is a good fellow," O'Grady said, turning to Terence, "but it is a misfortune that he is so prejudiced. Now, what is your own opinion?"

"I have no opinion about it, Captain O'Grady. I have a very strong opinion that I am not going to enjoy my breakfast, and that this motion does not agree with me at all. I have been ill half the night. Dick Ryan is awfully bad, and by the sounds I heard I should say a good many of the others are the same way. On the main deck it is awful; they have got the hatches battened down. I just took a peep in and bolted, for it seemed to me that everyone was ill."

"The best plan, lad, is to make up your mind that you are quite well. If you once do that you will be all right directly."

Terence could not for the moment reply, having made a sudden rush to the side.

"I don't see how I can persuade myself that I am quite well," he said, when he returned, "when I feel terribly ill."

"Yes, it wants resolution, Terence, and I am afraid that you are deficient in that. It must not be half-and-half. You have got to say to yourself, 'This is glorious; I never enjoyed myself so well in my life,' and when you have said that and feel that it is quite true, the whole thing will be over."

"I don't doubt it in the least," Terence said; "but I can't say it without telling a prodigious lie, and worse still, I could not believe the lie when I had told it."

"Then I am afraid that you must submit to be ill, Terence. I know once that I had a drame, and the drame was that I was at sea and horribly sea-sick, and I woke up and said to myself, 'This is all nonsense, I am as well as ever I was;' and, faith, so I was."

Ill as Terence was, he burst into a fit of laughter.

"That was just a dream, Captain O'Grady; but mine is a reality, you know. I don't think that you are looking quite well yourself."

"I am perfectly well as far as the sea goes, Terence; never was better in my life; but that pork we had for dinner yesterday was worse than usual, and I think perhaps I ought to have taken another glass or two to correct it."

"It must have been the pork," Terence said, as seriously as O'Grady himself; "and it is unfortunate that you are such an abstemious man, or, as you say, its effects might have been corrected."

"It's me opinion, Terence, my boy, that you are a humbug."

"Then, Captain O'Grady, it is clear that evil communications must have corrupted my good manners."

"It must have been in your infancy then, Terence, for divil a bit of manners good or bad have I ever seen in you; you have not even the good manners to take a glass of the cratur when you are asked."

"That is true enough," Terence laughed. "Having been brought up in the regiment, I have learned, at least, that the best thing to do with whisky is to leave it alone."

"I am afraid you will never be a credit to us, Terence."

"Not in the way of being able to make a heavy night of it and then turn out as fresh as paint in the morning," Terence retorted; "but you see, Captain O'Grady, even my abstinence has its advantages, for at least there will always be one officer in the corps able to go the round of the sentries at night."

At this moment the vessel gave such a heavy lurch that they were both thrown off their feet and rolled into the lee-scuppers, while, at the same moment, a rush of water swept over them. Amidst shouts of laughter from the other officers the two scrambled to their feet.

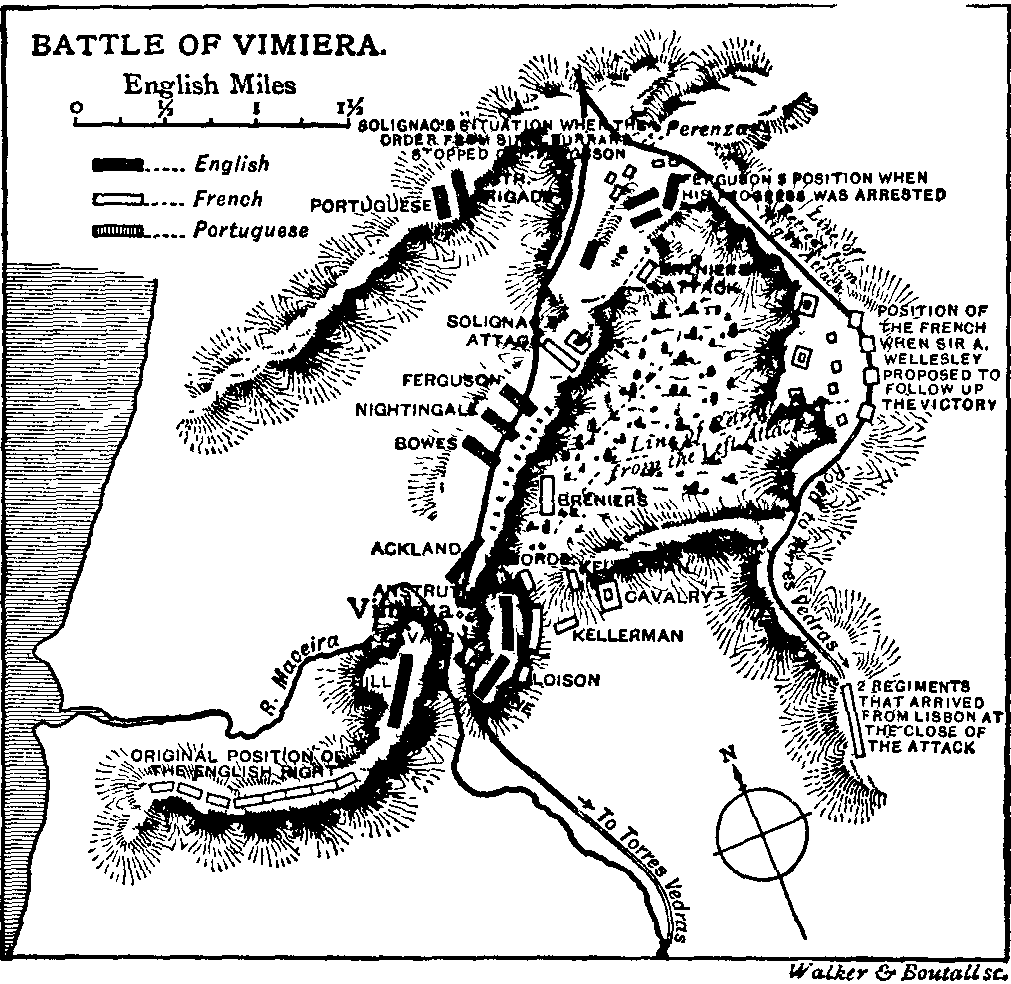

[Illustration: TWO FRENCH PRIVATEERS BEAR DOWN UPON THE SEA-HORSE]

"Holy Moses!" O'Grady exclaimed, "I am drowned entirely, and I sha'n't get the taste of the salt water out of me mouth for a week."

"There is one comfort," Terence said; "it might have been worse."

"How could it have been worse?" O'Grady asked, angrily.

"Why, if we hadn't been in the steadiest ship in the whole fleet we might have been washed overboard."

There was another shout of laughter. O'Grady made a dash at Terence, but the latter easily avoided him and went down below to change his clothes.

The gale increased in strength, and the whole vessel strained so heavily that her seams began to open, and by one o'clock the captain requested Major Harrison, who was in command, to put some of the soldiers at the pumps. For three days and nights relays of men kept the pumps going. Had it not been for the 400 troops on board, the Sea-horse would long before have gone to the bottom; but with such powerful aid the water was kept under, and on the morning of the fourth day the storm began to abate, and by evening more canvas was got on her. The next morning two vessels were seen astern at a distance of four or five miles. After examining them through his glass, the captain sent down a message to Major Harrison asking him to come up. In three or four minutes that officer appeared.

"There are two strange craft over there, Major; from their appearance I have not the least doubt that they are French privateers. I thought I should like your advice as to what had best be done."

"I don't know. You see, your guns might just as well be thrown overboard for any good they would be," the major said. "The things would not be safe to fire a salute with blank cartridge."

"No, they can hardly be called serviceable," the master agreed. "I spoke to the owner about it, but he said that as we were going to sail with a convoy it did not matter, and that we should have some others for the next voyage."

"I should like to see your owner dangling from the yardarm," the major said, wrathfully. "However, just at present the question is what had best be done. Of course they could not take the ship from us, but they would have very little difficulty in sinking her."

"The first thing is to put on every stitch of sail."

"That would avail us nothing; they can sail two feet to our one."

"Quite so, Major; I should not hope to get away, but they would think that I was trying to do so. My idea is that we should press on as fast as we can till they open fire at us; we could hold on for a bit, and then haul up into the wind and lower our top-sails, which they will take for a proof of surrender."

"You won't strike the flag, Captain; we cannot do anything treacherous."

"No, no, I am not thinking of doing that. You see, the flag is not hoisted yet, and we won't hoist it at all till they get close alongside, then we can haul it up, and sweep their decks with musketry. Of course your men will keep below until the last moment."

"That plan will do very well," the major agreed, "that is, if they venture to come boldly alongside."

"One is pretty sure to do so, though the other may lay herself ahead or astern of us, with her guns pointed to rake us in case we make any resistance; but seeing what we are, and that we carry only four small guns each side, they are hardly likely to suspect anything wrong. I am not at all afraid of beating them off; my only fear is that after they have sheared away they will open upon us from a distance."

"Yes, that would be awkward. However, if they do, we must keep the men below, and in the meantime you had better get your carpenter to cut up some spars and make a lot of plugs in readiness to stop up any holes they make near the water-line. I don't think they are likely to make very ragged holes, the wood is so rotten the shot would go through the side as if it were brown paper; still, you might get a lot of squares of canvas ready, with hammers and nails."

The strange craft were already heading towards the Sea-horse. No time was lost in setting every stitch of canvas that she could carry; the wind was light now, but the vessel was rolling heavily in a long swell. The major examined the guns closely and found that they were even worse than he had anticipated, the rust holes eaten in the iron having been filled up with putty, and the whole painted. He was turning away, with an exclamation of disgust, when Terence, who was standing near, said to him:

"I beg your pardon, Major, but don't you think that if we were to wind some thin rope very tightly round them three or four inches thick, they might stand a charge or two of grape to give them at close quarters; we needn't put in a very heavy charge of powder. Even if they did burst, I should think that the rope would prevent the splinters from flying about."

"The idea is not a bad one at all, Terence. I will see if the captain has got a coil or two of thin rope on board."

Fortunately the ship was fairly well supplied in this respect, and a few of the sailors who were accustomed to serving rope, with a dozen soldiers to help them, were told off to the work. The rope was wound round as tightly as the strength of a dozen men could pull it, the process being repeated five or six times, until each gun was surrounded by as many layers of rope. A thin rod had been inserted in the touch-hole. The cannon was then loaded with half the usual charge of powder, and filled to the muzzle with bullets. The rod was then drawn out, and powder poured in until it reached the surface.

While this was being done, all the soldiers not engaged in the work went below, and the officers sat down under shelter of the bulwarks. The two privateers, a large lugger and a brig, had been coming up rapidly, and by the time the guns were ready for action they were but a mile away. Presently a puff of smoke burst out from the bows of the lugger, and a round shot struck the water a short distance ahead of the Sea-horse. She held on her course without taking any notice of it, and for a few minutes the privateer was silent; then, when they were but half a mile away the brig opened fire, and two or three shots hulled the vessel.

"That will do, Captain," the major said. "You may as well lay-to now."

The Sea-horse rapidly flew up into the wind, the sheets were thrown off, and the upper sails were lowered, one after the other, the job being executed slowly, as if by a weak crew. The two privateers, which had been sailing within a short distance of each other, now exchanged signals, and the lugger ran on, straight towards the Sea-horse, while the brig took a course which would lay her across the stern of the barque, and enable them to rake her with her broadside. Word was passed below, and the soldiers poured up on deck, stooping as they reached it, and taking their places under the bulwarks. The major had already asked for volunteers among the officers, to fire the guns. All had at once offered to do so.

"As it was your proposal, Terence," the major said, "you shall have the honour of firing one; Ryan, you take another; Lieutenant Marks and Mr. Haines, you take the other two, and then England and Ireland will be equally represented."

The deck of the lugger was crowded with men, and the course she was steering brought her within a length of the Sea-horse. Some of the men were preparing to lower her boats, when suddenly a thick line of red coats appeared above the bulwarks, two hundred muskets poured in their fire, while the contents of the four guns swept her deck. The effect of the fire was tremendous. The deck was in a moment covered with dead and dying men; half a minute later another volley, fired by the remaining companies, completed the work of destruction. The halliards of one of the lugger's sails had been cut by the grape, and the sail now came down with a run to the deck.

"Down below, all of you," the major shouted, "the fellow behind will rake us in a minute."

The soldiers ran down to the hold again. A minute later the brig, sailing across the stern, poured in the fire of her guns one by one. Standing much lower in the water than her opponent, none of her shot traversed the deck of the Sea-horse, but they carried destruction among the cabins and fittings of the deck below. As this, however, was entirely deserted, no one was injured by the shot or flying fragments. The brig then took up her position three or four hundred yards away, on the quarter of the Sea-horse, and opened a steady fire against her.

To this the barque could make no reply, the fire of the muskets being wholly ineffective at that distance. The lugger lay helpless alongside the Sea-horse; the survivors of her crew had run below, and dared not return on deck to work their guns, as they would have been swept by the musketry of the Sea-horse.

Half an hour later Terence was ordered to go below to see how they were getting on in the hold.

Terence did so. Some lanterns had been lighted there, and he found that four men had been killed and a dozen or so wounded by the enemy's shot, the greater portion of which, however, had gone over their heads. The carpenter, assisted by some of the non-commissioned officers, was busy plugging holes that had been made in her between wind and water, and had fairly succeeded, as but four or five shots had struck so low, the enemy's object being not to sink, but to capture the vessel. As he passed up through the main deck to report, Terence saw that the destruction here was great indeed. The woodwork of the cabins had been knocked into fragments, there was a great gaping hole in the stern, and it seemed to him that before long the vessel would be knocked to pieces. He returned to the deck, and reported the state of things.

"It looks bad," the major said to O'Driscol. "This is but half an hour's work, and when the fellows come to the conclusion that they cannot make us strike, they will aim lower, and there will be nothing to do but to choose between sinking and hauling down our flag."

After delivering his report, Terence went to the side of the ship and looked down on the lugger. The attraction of the ship had drawn her closer to it, and she was but a few feet away. A thought struck him, and he went to O'Grady.

"Look here, O'Grady," he said, "that fellow will smash us up altogether if we don't do something."

"You must be a bright boy to see that, Terence; faith, I have been thinking so for the last ten minutes. But what are we to do? The muskets won't carry so far, at least not to do any good. The cannon are next to useless. Two of that lot you fired burst, though the ropes prevented any damage being done."

"Quite so, but there are plenty of guns alongside. Now, if you go to the major and volunteer to take your company and gain possession of the lugger, with one of the mates and half a dozen sailors to work her, we can get up the main-sail and engage the brig."

"By the powers, Terence, you are a broth of a boy," and he hurried away to the major.

"Major," he said, "if you will give me leave, I will have up my company and take possession of the lugger; we shall want one of the ship's officers and half a dozen men to work the sails, and then we will go out and give that brig pepper."

"It is a splendid idea, O'Grady."

"It is not my idea at all, at all; it is Terence O'Connor who suggested it to me. I suppose I can take the lad with me?"

"By all means, get your company up at once."

O'Grady hurried away, and in a minute the men of his company poured up onto the deck.

"You can come with me, Terence; I have the major's leave," he said to the lad.

At this moment there was a slight shock, as the lugger came in contact with the ship.

"Come on, lads," O'Grady said, as he set the example of clambering down onto the deck of the lugger. He was followed by his men, the first mate and six sailors also springing on board. The hatches were first put on to keep the remnant of the crew below. The sailors knotted the halliards of the main-sail, the soldiers tailed on to the rope, and the sail was rapidly run up. The mate put two of his men at the tiller, and the soldiers ran to the guns, which were already loaded.

"Haul that sheet to windward," the mate shouted, and the four sailors, aided by some of the soldiers, did so. Her head soon payed off, and amid a cheer from the officers on deck the lugger swept round. She mounted twelve guns. O'Grady divided the officers and non-commissioned officers among them, himself taking charge of a long pivot-gun in the bow.

"Take stiddy aim, boys, and fire as your guns bear on her; you ought not to throw away a shot at this distance."

As the lugger came out from behind the Sea-horse, gun after gun was fired, and the white splinters on the side of the brig showed that most, if not all, of the shots had taken effect. O'Grady's gun was the last to speak out, and the shot struck the brig just above the water-line.

"Take her round," he shouted to the mate; "give the boys on the other side a chance." The lugger put about and her starboard guns poured in their contents.

"That is the way," he shouted, as he laboured away with the men with him to load the pivot-gun again; "we will give him two or three more rounds, and then we will get alongside and ask for his health."

The brig, however, showed no inclination to await the attack. Some shots had been hastily fired when the lugger's first gun told them that she was now an enemy, and she at once put down her helm and made off before the wind, which was now very light.

"Load your guns and then out with the oars," Captain O'Grady shouted. "Be jabers, we will have that fellow. Let no man attend to the Sea-horse; it's from me that you are to take your orders. Besides," he said to Terence, "there is no signal-book on board, and they may hoist as many flags as they like."

The twelve sweeps on board the lugger were at once got out, and each manned by three soldiers. O'Grady himself continued to direct the fire of the pivot-gun, and sent shot after shot into the brig's stern. The latter had but some four hundred yards' start, and although she also hurriedly got out some sweeps, the lugger gained upon her. Her crew clustered on their taffrail, and kept up a musketry fire upon the party working the pivot-gun. Two of these had been killed and four wounded, when O'Grady said to the others:

"Lave the gun alone, boys; we shall be alongside of her in a few minutes; it is no use throwing away lives by working it. Run all the guns over to the other side; we will give them a warming, and then go at her."

The Sea-horse had hoisted signals directly those on board perceived that the lugger was starting in pursuit of the brig. Terence had informed his commanding officer of this, but O'Grady replied:

"I know nothing about them, Terence; most likely they mane 'Good-luck to you! Chase the blackguard, and capture him.' Don't let Woods come near me, whatever you do; I don't want to hear his idea of what the signals may mane."

Terence had just time to stop the mate as he was coming forward.

"The ship is signalling," he said.

"I have told Captain O'Grady, sir," Terence replied. "He does not know what the signal means, but has no doubt that it is instructions to capture the brig, and he means to do so."

The officer laughed.

"I think myself that it would be a pity not to," he said; "we shall be alongside in ten minutes. But I think it my duty to tell you what the signal is."

"You can tell me what it is," Terence said, "and it is possible that in the heat of action I may forget to report it to Captain O'Grady."

"That is right enough, sir. I think it is the recall."

"Well, I will attend to it presently," Terence laughed.

When within a hundred yards of the brig the troops opened a heavy musketry fire, many of the men making their way up the ratlines and so commanding the brig's deck. They were answered with a brisk fire, but the French shooting was wild, and by the shouting of orders and the confusion that prevailed on board it was evident that the privateersmen were disorganized by the sight of the troops and the capture of their consort. The brig's guns were hastily fired, as they could be brought to bear on the lugger, as she forged alongside. The sweeps had already been got in, and the lugger's eight guns poured their contents simultaneously into the brig, then a withering volley was fired, and, headed by O'Grady, the soldiers sprang on board the brig.

As they did so, however, the French flag fluttered down from the peak, and the privateersmen threw down their arms. The English broadside and volley fired at close quarters had taken terrible effect. Of the crew of eighty men thirty were killed and a large proportion of the rest wounded. The soldiers gave three hearty cheers as the flag came down.

The privateersmen were at once ordered below.

"Lieutenant Hunter," O'Grady said, "do you go on board the lugger with the left wing of the company. Mr. Woods, I think you had better stay here, there are a good many more sails to manage than there are in the lugger. One man here will be enough to steer her; we will pull at the ropes for you. Put the others on board the lugger."

"By the by, Mr. Woods," he said, "I see that the ship has hoisted a signal; what does it mean?"

"I believe that to be the recall, sir; I told Mr. O'Connor."

"You ought to have reported that same to me," O'Grady said, severely; "however, we will obey it at once."

The Sea-horse was lying head to wind a mile and a half away, and the two prizes ran rapidly up to her. They were received with a tremendous cheer from the men closely packed along her bulwarks. O'Grady at once lowered a boat and was rowed to the Sea-horse, taking Terence with him.

"You have done extremely well, Captain O'Grady," Major Harrison said, as he reached the deck, "and I congratulate you heartily. You should, however, have obeyed the order of recall; the brig might have proved too strong for you, and, bound on service as we are, we have no right to risk valuable lives except in self-defence."

"Sure I knew nothing about the signal," O'Grady said, with an air of innocence; "I thought it just meant 'More power to ye! give it 'em hot!' or something of that kind. It was not until after I had taken the brig that I was told that it was an order of recall. As soon as I learned that, we came along as fast as we could to you."

"But Mr. Woods must surely have known."

"Mr. Woods did tell me, Major," Terence put in, "but somehow I forgot to mention it to Captain O'Grady."

There was a laugh among the officers standing round.

"You ought to have informed him at once, Mr. O'Connor," the major said, with an attempt at gravity. "However," he went on, with a change of voice, "we all owe so much to you that I must overlook it, as there can be very little doubt that had it not been for your happy idea of taking possession of the lugger we should have been obliged to surrender, for I should not have been justified in holding out until the ship sank under us. I shall not fail, in reporting the matter, to do you full credit for your share in it. Now, what is your loss, Captain O'Grady?"

"Three men killed and eleven wounded, sir."

"And what is that of the enemy?"

"Thirty-two killed and about the same number of wounded, more or less. We had not time to count them before we sent them down, and I had not time afterwards, for I was occupied in obeying the order of recall. I am sorry that we have killed so many of the poor beggars, but if they had hauled down their flag when we got up with them there would have been no occasion for it. I should have told their captain that I looked upon him as an obstinate pig, but as he and his first officer were both killed, there was no use in my spaking to him."

"Well, it has been a very satisfactory operation," the major said, "and we are very well out of a very nasty fix. Now, you will go back to the brig, Captain O'Grady, and prepare to send the prisoners on board. We will send our boats for them. Doctor Daly and Doctor O'Flaherty will go on board with you and see to the wounded French and English. Doctor Daly will bring the worst cases on board here, and will leave O'Flaherty on the brig to look after the others. They will be better there than in this crowded ship. The first officer will remain there with you with five men, and you will retain fifty men of your own company. The second officer, with five men, will take charge of the lugger. He will have with him fifty men of Captain O'Driscol's company, under that officer. That will give us a little more room on board here. How many prisoners are there?"

"Counting the wounded, Major, there are about fifty of them; her crew was eighty strong to begin with. There are only some thirty, including the slightly wounded, to look after."

"If the brig's hold is clear, I think that you had better take charge of them. At present you will both lie-to beside us here till we have completed our repairs, and when we make sail you are both to follow us, and keep as close as possible; and on no account, Captain O'Grady, are you to undertake any cruises on your own account."

"I will bear it in mind, Major; and we will do all we can to keep up with you."

A laugh ran round the circle of officers at O'Grady's obstinacy in considering the Sea-horse to be a fast vessel, in spite of the evidence that they had had to the contrary. The major said, gravely:

"You will have to go under the easiest sail possible. The brig can go two feet to this craft's one, and you will only want your lower sails. If you put on more you will be running ahead and losing us at night. We shall show a light over our stern, and on no account are you to allow yourselves to lose sight of it."

A party of men were already at work nailing battens over the shattered stern of the Sea-horse. When this was done, sail-cloth was nailed over them, and a coat of pitch given to it. The operation took four hours, by which time all the other arrangements had been completed. The holds of the two privateers were found to be empty, and they learned from the French crews that the two craft had sailed from Bordeaux in company but four days previously, and that the Sea-horse was the first English ship that they had come across.

"You will remember, Captain O'Grady," the major said, as that officer prepared to go on board, "that Mr. Woods is in command of the vessel, and that he is not to be interfered with in any way with regard to making or taking in sail. He has received precise instructions as to keeping near us, and your duties will be confined to keeping guard over the prisoners, and rendering such assistance to the sailors as they may require."

"I understand, Major; but I suppose that in case you are attacked we may take a share in any divarsion that is going on?"

"I don't think that there is much chance of our being attacked, O'Grady; but if we are, instructions will be signalled to you. French privateers are not likely to interfere with us, seeing that we are together, and if by any ill-luck a French frigate should fall in with us, you will have instructions to sheer off at once, and for each of you to make your way to Lisbon as quickly as you can. You see, we have transferred four guns from each of your craft to take the place of the rotten cannon on board here, but our united forces would be of no avail at all against a frigate, which would send us to the bottom with a single broadside. We can neither run nor fight in this wretched old tub. If we do see a French frigate coming, I shall transfer the rest of the troops to the prizes and send them off at once, and leave the Sea-horse to her fate. Of course we should be very crowded on board the privateers, but that would not matter for a few days. So you see the importance of keeping quite close to us, in readiness to come alongside at once if signalled to. We shall separate as soon as we leave the ship, so as to ensure at least half our force reaching its destination."

Captain O'Driscol took Terence with him on board the lugger, leaving his lieutenant in charge of the wing that remained on board the ship.

"You have done credit to the company, and to my choice of you, Terence," he said, warmly, as they stood together on the deck of the lugger. "I did not see anything for it but a French prison, and it would have broken my heart to be tied up there while the rest of our lads were fighting the French in Portugal. I thought that you would make a good officer some day in spite of your love of devilment, but I did not think that before you had been three weeks in the service you would have saved half the regiment from a French prison."

As soon as the vessels were under way again it was found that the lugger was obliged to lower her main-sail to keep in her position astern of the Sea-horse, while the brig was forced to take in sail after sail until the whole of the upper sails had been furled.

"It is tedious work going along like this," O'Driscol said; "but it does not so much matter, because as yet we do not know where we are going to land. Sir Arthur has gone on in a fast ship to Corunna to see the Spanish Junta there, and find out what assistance we are likely to get from Northern Spain. That will be little enough. I expect they will take our money and arms and give us plenty of fine promises in return, and do nothing; that is the game they have been playing in the south, and if there were a grain of sense among our ministers they would see that it is not of the slightest use to reckon on Spain. As to Portugal, we know very little at present, but I expect there is not a pin to choose between them and the Spaniards."

"Then we are not going to Lisbon?" Terence said, in surprise.

"I expect not. Sir Arthur won't determine anything until he joins us after his visit to Corunna, but I don't think that it will be at Lisbon, anyhow. There are strong forts guarding the mouth of the river, and ten or twelve thousand troops in the city, and a Russian fleet anchored in the port. I don't know where it will be, but I don't think that it will be Lisbon. I expect that we shall slip into some little port, land, and wait for Junot to attack us; we shall be joined, I expect, by Stewart's force, that have been fooling about for two or three months waiting for the Spaniards to make up their minds whether they will admit them into Cadiz or not. You see, at present there are only 9,000 of us, and they say that Junot has at least 50,000 in Portugal; but of course they are scattered about, and it is hardly likely that he would venture to withdraw all his garrisons from the large towns, so that the odds may not be as heavy as they look, when we meet him in the field. And I suppose that at any rate some of the Portuguese will join us. From what I hear, the peasantry are brave enough, only they have never had a chance yet of making a fight for it, owing to their miserable government, which never can make up its mind to do anything. I hope that Sir Arthur has orders, as soon as he takes Lisbon, to assume the entire control of the country and ignore the native government altogether. Even if they are worth anything, which they are sure not to be, it is better to have one head than two, and as we shall have to do all the fighting, it's just as well that we should have the whole control of things too."

For four days they sailed along quietly. On the morning of the fifth the signal was run up from the Sea-horse for the prizes to close up to her. Mr. Woods, the mate on board the brig, at once sent a sailor up to the mast-head.

"There is a large ship away to the south-west, sir," he shouted down.

"What does she look like?"

"I can only see her royals and top-sails yet, but by their square cut I think that she is a ship-of-war."

"Do you think she is French or English?"

"I cannot say for certain yet, sir, but it looks to me as if she is French. I don't think that the sails are English cut anyhow."

Such was evidently the opinion on board the Sea-horse, for as the prizes came up within a hundred yards of her they were hailed by the major through a speaking-trumpet, and ordered to keep at a distance for the present, but to be in readiness to come up alongside directly orders were given to that effect.

In another half-hour the look-out reported that he could now see the lower sails of the stranger, and had very little doubt but that it was a large French frigate. Scarcely had he done so before the two prizes were ordered to close up to the Sea-horse. The sea was very calm and they were able to lie alongside, and as soon as they did so the troops began to be transferred to them. In a quarter of an hour the operation was completed, Major Harrison taking his place on board the lugger; half the men were ordered below, and the prize sheered off from the Sea-horse.

"The Frenchman is bearing down straight for us," he said to O'Driscol; "she is bringing a breeze down with her, and in an hour she will be alongside. I shall wait another half-hour, and then we must leave the Sea-horse to her fate; except for our stores she is worthless. Well, Terence, have you any suggestion to offer? You got us out of the last scrape, and though this is not quite so bad as that, it is unpleasant enough. The frigate when she comes near will see that the Sea-horse is a slow sailer, and will probably leave her to be picked up at her leisure, and will go off in chase either of the brig or us. The brig is to make for the north-west and we shall steer south-east, so that she will have to make a choice between us. When we get the breeze we shall either of us give her a good dance before she catches us--that is, if the breeze is not too strong; if it is, her weight would soon bring her up to us."

"Yes, Major, but perhaps she may not trouble about us at all. She would see at once that the lugger and brig are French, and if they were both to hoist French colours, and the Sea-horse were to fly French colours over English, she would naturally suppose that she had been captured by us, and would go straight on her course without troubling herself further about it."

"So she might, Terence. At any rate the scheme is worth trying. If they have anything like good glasses on board they could make out our colours miles away. If she held on towards us after that, there would be plenty of time for us to run, but if we saw her change her course we should know that we were safe. Your head is good for other things besides mischief, lad."

The lugger sailed up near the ship again, and the major gave the captain instructions to hoist a French ensign over an English one, and then, sailing near the brig, told them to hoist French colours.

"Keep all your men down below the line of the bulwarks, O'Grady. Mr. Woods, you had better get your boat down and row alongside of the ship, and ask the captain to get the slings at work and hoist some of our stores into her; we will do the same on the other side. Tell the captain to lower a couple of his boats; also take twenty soldiers on board with you without their jackets; we will do the same, so that it may be seen that we have a strong party on board getting out the cargo."

In a few minutes the orders were carried out, and forty soldiers were at work on the deck of the Sea-horse, slinging up tents from below, and lowering them into the boats alongside. The approach of the frigate was anxiously watched from the decks of the prizes. The upper sails of the Sea-horse had been furled, and the privateers, under the smallest possible canvas, kept abreast of her at a distance of a couple of lengths. The hull of the French frigate was now visible. "She is very fast," the mate said to the major, "and she is safe to catch one of us if the breeze she has got holds."

As she came nearer the feeling of anxiety heightened.

"They ought to make out our colours now, sir."

Almost immediately afterwards the frigate was seen to change her course. Her head was turned more to the east. A suppressed cheer broke from the troops.

"It is all right now, sir," the mate said; "she is making for Brest. We have fooled her nicely."

The boats passed and repassed between the Sea-horse and the prizes, and the frigate crossed a little more than a mile ahead.

"Five-and-twenty guns a-side," the major said. "By Jove! she would have made short work of us."